Validating Autism Spectrum Disorder Mechanisms: A Cross-Omics Integration Framework for Research and Drug Development

This article synthesizes current methodologies and findings in cross-omics validation for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), addressing the critical need for reproducible and biologically relevant insights for researchers and drug development...

Validating Autism Spectrum Disorder Mechanisms: A Cross-Omics Integration Framework for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article synthesizes current methodologies and findings in cross-omics validation for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), addressing the critical need for reproducible and biologically relevant insights for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational 'Gut Microbiota-Immune-Brain Axis' and mitochondrial dysfunction as key etiological frameworks. The article details advanced statistical and machine learning frameworks like Cross-Platform Omics Prediction (CPOP) and Multi-Omics Mendelian Randomization for robust, platform-independent analysis. It further addresses critical challenges in model transferability, data heterogeneity, and participant diversity, offering optimization strategies. Finally, we present a comparative analysis of validation techniques, from single-cell multi-omics to multi-cohort replication, that prioritize causal genes and pathways, providing a comprehensive roadmap for translating multi-omics discoveries into validated therapeutic targets.

Unraveling Complexity: Foundational Biological Axes in Autism Spectrum Disorder

The gut-microbiota-immune-brain axis represents a sophisticated bidirectional communication network that integrates the gastrointestinal tract, its resident microbial communities, the immune system, and the central nervous system. This cross-system regulatory network facilitates complex interactions between peripheral systems and the brain through neural, endocrine, and immune pathways [1] [2]. Emerging research underscores this axis's pivotal role in maintaining physiological homeostasis while also contributing to various disease states when dysregulated.

The conceptual understanding of this axis has evolved significantly from initial gut-brain observations to now encompass essential immune system mediation. The immune system serves as a critical intermediary in gut-brain communication, forming what is now recognized as the gut–immune–brain axis [1]. This integrated network demonstrates remarkable complexity, with gut microbes and their metabolites exerting profound effects on immune and neurological homeostasis, influencing the development and function of multiple physiological systems [1]. The axis's functionality relies on multiple interconnected pathways, including the autonomic nervous system, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, enteric nervous system, and various immune signaling mechanisms [2].

Understanding this cross-system network has profound implications for neurological, psychiatric, and neurodevelopmental disorders, offering new perspectives for therapeutic interventions that target peripheral systems to influence central nervous system function [1] [2].

Multi-Omics Validation in Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) has emerged as a key model for understanding disruptions in the gut-microbiota-immune-brain axis. Integrative multi-omics approaches have provided unprecedented insights into the complex pathophysiology of ASD, revealing intricate cross-system interactions that contribute to the disorder's manifestation.

Genetic and Microbial Interactions in ASD

Recent large-scale studies have employed multi-omics integration to elucidate how genetic risk factors interact with gut microbiota and immune function in ASD. A comprehensive meta-analysis of Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) data from four independent ASD cohorts identified specific single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with multi-dimensional associations across systems [3] [4]. The analysis revealed that loci such as rs2735307 and rs989134 exert cross-tissue regulatory effects by participating in gut microbiota regulation while simultaneously involving immune pathways such as T cell receptor signal activation and neutrophil extracellular trap formation [3]. These genetic variants further demonstrate the ability to cis-regulate neurodevelopmental genes (including HMGN1 and H3C9P) or synergistically influence epigenetic methylation modifications to regulate the expression of BRWD1 and ABT1 [4].

Complementing these genetic findings, a separate multi-omics study analyzing the gut microbiota of 30 children with severe ASD and 30 healthy controls revealed significant alterations in microbial community structure and function [5]. Children with ASD exhibited reduced microbial diversity and characteristic community shuffling patterns, highlighting potential microbial crosstalk in ASD pathophysiology [5]. The study identified Tyzzerella as uniquely associated with the ASD group, while microbial network analysis revealed rewiring and reduced stability in ASD compared to neurotypical controls.

Table 1: Multi-Omics Findings in Autism Spectrum Disorder

| Analysis Type | Key Findings | Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Meta-Analysis | Identification of cross-tissue regulatory SNPs (rs2735307, rs989134) | Regulation of neurodevelopmental genes (HMGN1, H3C9P); involvement in gut microbiota and immune pathways [3] |

| Metaproteomics | Major metaproteins produced by Bifidobacterium and Klebsiella (xylose isomerase, NADH peroxidase) | Altered microbial metabolic activity potentially influencing host physiology [5] |

| Metabolomics | Altered neurotransmitters (glutamate, DOPAC), lipids, and amino acids capable of crossing BBB | Potential direct modulation of neurodevelopment and immune function [5] |

| Host Proteome | Altered proteins including kallikrein (KLK1) and transthyretin (TTR) | Involvement in neuroinflammation and immune regulation [5] |

Integrated Multi-Omics Workflow

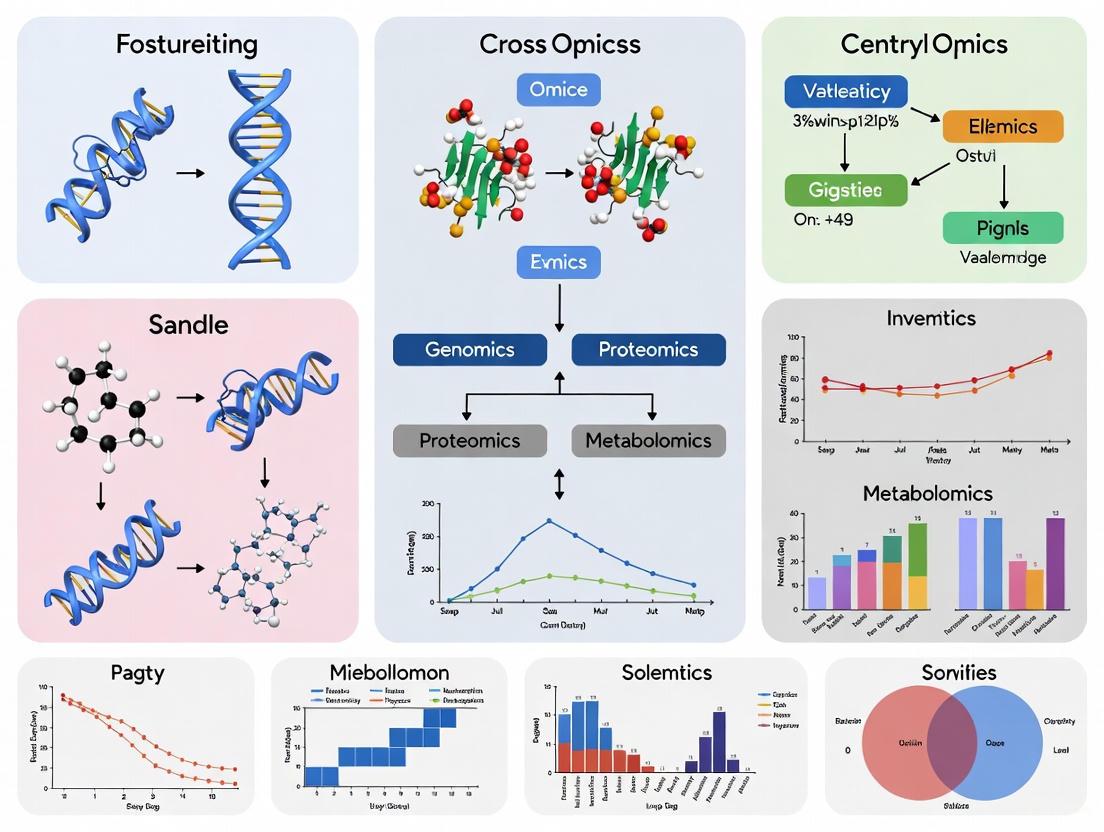

The power of multi-omics approaches lies in their ability to integrate data across molecular levels, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the complex interactions within the gut-microbiota-immune-brain axis. The following diagram illustrates a representative integrative multi-omics workflow for studying this axis in ASD:

Diagram 1: Integrative Multi-Omics Workflow for Gut-Microbiota-Immune-Brain Axis Research. SMR: Summary-data-based Mendelian Randomization; GWAS: Genome-Wide Association Study; eQTL: expression Quantitative Trait Loci; mQTL: methylation Quantitative Trait Loci.

Experimental Methodologies for Axis Characterization

Key Analytical Protocols

Research investigating the gut-microbiota-immune-brain axis employs sophisticated methodological approaches designed to capture the complexity of cross-system interactions. The following experimental protocols represent core methodologies cited in current literature:

Genomic Integration and Meta-Analysis Protocol This protocol involves identifying genetic variants with cross-tissue regulatory effects through a multi-stage analytical process [3] [4]:

- Multi-Cohort GWAS Meta-Analysis: Integration of genome-wide association data from multiple independent cohorts using tools like METAL with fixed-effects models, followed by heterogeneity assessment (Cochran's Q and I² indices) and random-effects model application when appropriate [3]

- Novel Loci Screening: Exclusion of known loci (≥500 kb apart from previously reported loci on same chromosome) with linkage disequilibrium pruning (r² < 0.001 within 10,000 kb window) [3]

- Polygenic Priority Score (PoPS) Analysis: Gene annotation using biomaRt package connected to Ensembl database to identify genes within 500 kb upstream and downstream of novel loci [3]

- Cross-Omics Integration: Summary-data-based Mendelian Randomization (SMR) analyses integrating brain cis-eQTL and mQTL data with bidirectional Mendelian randomization of gut microbiota and SMR analysis of blood eQTL [3] [4]

Multi-Omics Microbial Community Analysis This comprehensive protocol characterizes microbial communities and their functional interactions with the host [5]:

- Microbial Diversity Assessment: 16S rRNA V3 and V4 sequencing for taxonomic classification with analysis of α-diversity (within-sample diversity) and β-diversity (between-sample diversity) metrics

- Metaproteomic Identification: Novel metaproteomics pipeline for bacterial protein identification using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with functional annotation of identified proteins

- Metabolomic Profiling: Untargeted metabolomics exploration using LC-MS and GC-MS to identify altered metabolic pathways, focusing on neurotransmitters, lipids, and amino acids capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier

- Host Proteome Analysis: Quantification of host protein expression changes with particular attention to proteins involved in nervous system development and immune response

- Multi-Omics Data Integration: Statistical integration of genomic, metaproteomic, and metabolomic datasets to identify coordinated macromolecular changes linked to neurodevelopmental deficits

Model Systems and Manipulation Approaches

Preclinical models remain essential for mechanistic studies of the gut-microbiota-immune-brain axis, with several key approaches emerging:

Germ-Free Mouse Models Germ-free (GF) mice, raised in completely sterile conditions without any microorganisms, provide a fundamental model for studying microbiota contributions to neurodevelopment and immune function. Studies demonstrate that GF mice exhibit significant immune system alterations, including reductions in immune cell populations (macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils, T cells, and B cells) and lower cytokine production [1]. These animals also show ENS immaturity and immune dysregulation that can be partially restored through microbial colonization [2]. The timing of colonization appears critical, with early-life presentation representing a particularly sensitive window for microbial-immune-neural programming [1].

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) FMT studies, which transfer microbial communities from human donors to recipient animals, powerfully demonstrate the functional impact of gut microbiota on brain function and behavior. Transplantation of gut microbiota from MDD patients to germ-free rodent models leads to the development of depression-like behaviors and physiological characteristics similar to those observed in human donors [6]. Similar approaches using ASD donors have replicated behavioral and immunological features of the disorder, providing causal evidence for microbial contributions to disease pathophysiology.

Table 2: Experimental Models for Gut-Microbiota-Immune-Brain Axis Research

| Model System | Key Applications | Limitations and Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Germ-Free Mice | Studying neurodevelopment in absence of microbiota; immune system maturation; microbial colonization effects [1] [2] | Artificial conditions not reflecting natural microbial exposure; potential developmental compensation mechanisms |

| Fecal Microbiota Transplantation | Establishing causal relationships between specific microbial profiles and host phenotypes; modeling human diseases in animals [6] | Variable engraftment efficiency; incomplete transmission of complete microbial community; host-genotype effects on colonization |

| Antibiotic-induced Dysbiosis | Investigating consequences of microbiota depletion; timing-specific effects on development [1] | Non-specific microbial reduction; potential direct drug effects beyond microbiome alteration |

| Gnotobiotic Models | Studying defined microbial communities in controlled conditions; mechanism testing with specific bacterial consortia [1] | Simplified communities not reflecting natural complexity; challenging to establish stable defined communities |

Signaling Pathways in the Gut-Immune-Brain Axis

The communication along the gut-microbiota-immune-brain axis involves multiple sophisticated signaling pathways that enable bidirectional information flow between peripheral systems and the central nervous system. The following diagram illustrates the major communication pathways:

Diagram 2: Major Signaling Pathways in the Gut-Microbiota-Immune-Brain Axis. SCFAs: Short-Chain Fatty Acids; MAMPs: Microbe-Associated Molecular Patterns; TLR: Toll-Like Receptor; HDAC: Histone Deacetylase; FFAR: Free Fatty Acid Receptor.

Key Pathway Mechanisms

Immune Signaling Pathways The immune system serves as a crucial intermediary in gut-brain communication through several distinct mechanisms [1] [2]:

- Cytokine-Mediated Signaling: Gut microbiota dysbiosis can trigger increased intestinal permeability, allowing bacterial components like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to translocate into circulation, activating immune cells and promoting pro-inflammatory cytokine release (IL-6, TNF-α, IL-17) that can access the brain and alter neuroinflammation [2] [6]

- Toll-like Receptor (TLR) Activation: Microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) engage pattern recognition receptors including TLRs on immune and epithelial cells. TLR4 recognition of bacterial LPS activates NF-κB and interferon pathways, driving proinflammatory cytokine production, while TLR2 activation by probiotic components can promote anti-inflammatory pathways through Treg induction [1]

- T Cell-Mediated Mechanisms: The gut microbiota shapes T cell differentiation and function, with specific commensals driving distinct T helper cell responses. Segmented filamentous bacteria promote Th17 differentiation, while microbial metabolites like SCFAs enhance regulatory T cell (Treg) differentiation, balancing inflammatory responses [1]

Neural Communication Pathways Neural pathways provide direct, rapid communication between the gut and brain [7] [2]:

- Vagus Nerve Signaling: The vagus nerve serves as a primary information highway, with afferent fibers detecting gut signals (stretch, tension, chemical signals from microbiota) and relaying them to the brainstem. Vagal activity is influenced by gut microbiota and their metabolites, with vagotomy studies demonstrating its essential role in gut-brain communication [2]

- Enteric Nervous System (ENS): The "second brain" comprising over 100 million neurons in the human digestive tract forms a semi-autonomous neural network that interfaces with gut immune cells and responds to microbial signals. ENS neurons can modulate immune cell activity through neurotransmitter interactions and shape immune signaling in the gut [7] [2]

Microbial Metabolite Pathways Gut microbiota produce numerous bioactive metabolites that influence brain function [1] [2] [5]:

- Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs): Produced by microbial fermentation of dietary fiber, SCFAs (acetate, propionate, butyrate) influence immune function through G protein-coupled receptor activation (FFAR2, FFAR3) and histone deacetylase inhibition, regulating T cell differentiation and inflammatory cytokine production

- Neuroactive Metabolites: Gut bacteria produce and respond to neurochemicals including serotonin, GABA, catecholamines, and indole derivatives. Bacterial tryptophan metabolism generates serotonin and kynurenine metabolites that influence gastrointestinal serotonergic systems, immune regulation, and mental health [2]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Investigating the gut-microbiota-immune-brain axis requires specialized reagents and methodological approaches. The following table compiles key research solutions identified in the literature:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Axis Investigation

| Reagent/Solution | Research Application | Specific Function |

|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA Sequencing Reagents | Microbial community profiling | Taxonomic classification and α/β-diversity assessment of gut microbiota [5] |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Metaproteomic and metabolomic analysis | Identification and quantification of bacterial proteins and host metabolites [5] |

| GWAS Meta-Analysis Tools | Genomic integration studies | Cross-study genetic variant analysis (METAL, PLINK) [3] |

| SMR Analysis Pipeline | Cross-omics data integration | Summary-data-based Mendelian Randomization for identifying gene expression associations [3] [4] |

| Germ-Free Housing Systems | Microbiota manipulation studies | Maintaining sterile conditions for colonization experiments [1] [2] |

| Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Protocols | Causality establishment | Transfer of microbial communities between donors and recipients [6] |

| TLR Agonists/Antagonists | Immune pathway characterization | Specific modulation of pattern recognition receptor signaling [1] |

| Vagal Nerve Stimulation Equipment | Neural pathway investigation | Modulating gut-brain neural communication [7] [2] |

| SCFA Receptor Modulators | Metabolite signaling studies | Investigating FFAR2/FFAR3-mediated mechanisms [1] [2] |

| Cytokine Measurement Assays | Immune activation monitoring | Quantifying inflammatory mediators in periphery and CNS [6] |

The gut-microbiota-immune-brain axis represents a fundamental cross-system regulatory network that integrates genetic predisposition, microbial communities, immune function, and neurological outcomes. Multi-omics approaches have been particularly valuable in decoding these complex interactions, especially in neurodevelopmental conditions like ASD where specific genetic variants (e.g., rs2735307, rs989134) demonstrate pleiotropic effects across tissues and systems [3] [4].

The experimental evidence summarized here highlights the axis's complexity, with communication occurring through multiple parallel pathways including neural connections (vagus nerve, ENS), immune signaling (cytokines, TLR activation, T cell responses), and microbial metabolites (SCFAs, neuroactive compounds). This multidimensional communication network offers both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

Future research directions will likely focus on developing precision microbiota interventions tailored to individual genetic and immune profiles, leveraging our growing understanding of this axis to design innovative treatments for neurological, psychiatric, and neurodevelopmental disorders [1]. The continued refinement of multi-omics integration methods and experimental models will further enhance our ability to decode this sophisticated cross-system regulatory network, ultimately advancing both fundamental knowledge and clinical applications.

This guide compares the performance of a multi-omics causal inference framework against conventional genomic analyses for validating mitochondrial involvement in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). The integrated approach identifies a structure-metabolism-redox axis, prioritizing three key mitochondrial genes—TMEM177, CRAT, and PRDX6—with robust cross-omics support. The data presented below, synthesized from large-scale genomic studies and multi-omics investigations, provide objective evidence of this framework's superior capability to pinpoint compartment-specific biomarkers and precision intervention targets compared to traditional single-layer analyses.

Table 1: Performance Comparison: Multi-omics Framework vs. Conventional Genomic Analyses

| Analysis Feature | Multi-omics Causal Inference | Conventional GWAS |

|---|---|---|

| Causal Resolution | High (Mendelian Randomization + Colocalization) [8] [9] | Moderate (Association-based) [3] |

| Tissue Specificity | Identifies divergent risk (e.g., TMEM177 in brain vs. blood) [8] [9] | Limited, often single-tissue focus [3] |

| Mechanistic Insight | Deep, cross-layer (mQTL/eQTL/pQTL) [8] [9] | Shallow, primarily genetic [10] |

| Biomarker Potential | High (CpG variation aligned with expression/risk) [9] | Low to Moderate |

| Therapeutic Target Validation | Strong (Convergent evidence across omics layers) [8] [9] | Preliminary (Requires functional validation) [10] |

Multi-omics Causal Inference: Experimental Protocols and Data

The most robust evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction in ASD originates from studies employing a multi-omics Mendelian Randomization (MR) framework. This protocol tests causal relationships between genetic instruments and outcomes by leveraging natural genetic variation, effectively mimicking a randomized controlled trial.

Core Experimental Protocol

The following workflow outlines the key steps for the multi-omics causal inference analysis:

Step 1: Data Integration and Harmonization GWAS summary statistics for ASD are obtained from large consortia (e.g., IEU and FinnGen) [8] [9]. Quantitative trait locus (QTL) data are integrated from:

- Methylation QTLs (mQTLs): From a meta-analysis of epigenetic studies.

- Expression QTLs (eQTLs): From the eQTLGen Consortium (blood) and 12 brain regions in the GTEx database.

- Protein QTLs (pQTLs): From large-scale proteomic studies (e.g., deCODE Genetics) [9]. Genetic instruments (SNPs) are harmonized across all datasets to ensure effect alleles correspond to the same strand.

Step 2: Summary-data-based Mendelian Randomization (SMR) & HEIDI Test SMR analysis tests for a causal effect of a gene expression/ methylation/ protein level on ASD risk [8] [9]. The null hypothesis is that there is no causal effect. The HEIDI (Heterogeneity in Dependent Instruments) test is subsequently applied to distinguish pleiotropy from linkage. A significant HEIDI test (p < 0.05) suggests the SMR result is likely due to linkage disequilibrium rather than a true causal relationship, and such hits are excluded.

Step 3: Bayesian Colocalization For loci passing SMR, Bayesian colocalization analysis is performed to calculate the posterior probability that the ASD GWAS signal and the QTL (e.g., eQTL) share a single common causal variant (PPH4) [8] [9]. A PPH4 > 0.70 is considered strong evidence for colocalization, ensuring the genetic association is not driven by distinct but correlated variants.

Step 4: Two-Sample MR Robustness Checks Where independent cis-acting genetic instruments are available, two-sample MR is applied. This uses multiple SNPs as instruments to estimate the causal effect and performs sensitivity analyses (e.g., MR-Egger, MR-PRESSO) to assess and correct for horizontal pleiotropy [9].

Key Experimental Findings and Comparative Data

The application of the above protocol yielded convergent evidence for three nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes. Their functions and supporting data are compared below.

Table 2: Experimentally Validated Genes in the Mitochondrial Axis in ASD

| Gene | Primary Mitochondrial Function | Supporting Omics Layers | Causal Association with ASD | Key Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMEM177 | Complex IV (COX2) assembly; Structural integrity [8] [9] | mQTL, eQTL (brain and blood) [8] [9] | Risk-increasing in cerebellar/cortical regions; Protective in blood [8] [9] | Exhibits tissue-specific directional pleiotropy; supported by colocalization (PPH4 > 0.70) [9] |

| CRAT | Acetyl-CoA buffering; Metabolic flexibility [8] [9] | mQTL, eQTL, pQTL in specific datasets [8] [9] | Protective [8] [9] | Locus-specific CpG variation directionally aligned with gene expression and reduced ASD risk [9] |

| PRDX6 | Redox homeostasis; Phospholipid membrane repair [8] [9] | mQTL, eQTL, pQTL in specific datasets [8] [9] | Protective [8] [9] | Convergent evidence from SMR across multiple QTL layers [8] [9] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents and datasets critical for replicating and extending this multi-omics research.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Cross-omics Validation

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example Source / Database |

|---|---|---|

| ASD GWAS Summary Statistics | Base data for genetic association and MR analyses. | IEU OpenGWAS, FinnGen, PGC [8] [3] [9] |

| QTL Datasets (m/e/pQTL) | Provide molecular phenotype links for genetic instruments. | eQTLGen (blood), GTEx (brain), deCODE (pQTL) [9] |

| MitoCarta3.0 | Reference database for curated mitochondrial protein localization. | Broad Institute [9] |

| SMR & HEIDI Software | Performs summary-data-based MR and heterogeneity testing. | SMR Software [8] [9] |

| Coloc R Package | Implements Bayesian colocalization analysis to test for shared causal variants. | CRAN R Repository [8] [9] |

| Two-Sample MR R Package | A comprehensive suite for performing two-sample MR and sensitivity analyses. | MR-Base platform [9] |

Integrated Signaling Pathways: From Genetic Defects to Neurodevelopmental Deficits

The genes prioritized through multi-omics analyses are not isolated players but form an interconnected structure-metabolism-redox axis. The following diagram synthesizes the mechanistic pathway from genetic variation to core ASD pathophysiology, integrating oxidative stress and neuroinflammation as key amplifiers.

Pathway Narrative: The pathway is initiated by genetic risk variants (e.g., in TMEM177, CRAT, PRDX6) identified via multi-omics causal inference [8] [9]. These variants disrupt core mitochondrial functions, creating a triple-hit axis: 1) Structural Defects (TMEM177 impacting ETC complex IV assembly), 2) Metabolic Dysregulation (CRAT impairing acetyl-CoA metabolism), and 3) Redox System Failure (PRDX6 compromising antioxidant defense and membrane repair) [8] [9] [11].

This mitochondrial dysfunction leads to a vicious cycle of oxidative stress, characterized by elevated reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) and depletion of antioxidants like glutathione [11] [12] [13]. The resulting oxidative distress causes widespread biomolecular damage and triggers neuroinflammation, including microglial activation and pro-inflammatory cytokine release [11] [13].

Concurrently, energy depletion (reduced ATP) and the toxic oxidative-inflammatory milieu converge to cause synaptic dysfunction, impairing synaptic transmission, plasticity, and ultimately, proper neural circuit formation [11]. This cascade, during critical neurodevelopmental windows, manifests as the altered brain development and core behavioral symptoms observed in ASD [8] [11].

A Cross-Omics Validation Guide for Autism Spectrum Disorder Research

Abstract This guide provides a comparative analysis of methodologies and findings central to validating the role of dysregulated Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-related signaling in peripheral immune cells, specifically Natural Killer (NK) and T cell subsets, within Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Framed within the imperative for cross-omics validation in complex neurodevelopmental disorders, we synthesize data from transcriptomic, proteomic, and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) studies [14]. We present standardized experimental protocols, quantitative data comparisons, and essential research tools to equip scientists and drug development professionals with a framework for replicating and extending these critical findings.

1. Introduction: The Case for Cross-Omics Validation in ASD Immunology ASD is a heterogenous neurodevelopmental condition with increasing evidence linking its etiology and symptomatology to immune dysregulation [14]. Isolated omics studies, while valuable, often provide fragmented insights. A multi-omics approach that integrates genomic, proteomic, and cellular-resolution data is essential for constructing a causally plausible pathway from genetic risk to peripheral immune phenotype and, potentially, to central nervous system pathophysiology [14] [3]. This guide focuses on the TNF/TNFR superfamily—a pivotal network of ligands and receptors governing inflammation, cell survival, and immune cell communication [15] [16]. Recent evidence implicates specific TNF-related pathways in ASD, offering tangible therapeutic targets [14]. The following sections provide a comparative, data-driven guide to investigating this axis.

2. Cross-Omics Findings: From Gene Signatures to Cellular Actors Key discoveries across analytical layers converge on disrupted TNF signaling in ASD.

2.1 Transcriptomic Layer: Immune Gene Signatures A targeted transcriptomic study of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from young children with ASD identified 50 differentially expressed immune-related genes. Three genes—JAK3, CUL2, and CARD11—showed a negative correlation with ASD symptom severity, suggesting their expression levels may reflect clinical state [14]. Enrichment analysis firmly linked this gene set to immune function, with the TNF signaling pathway being a top hit [14].

Table 1: Key Transcriptomic Findings in ASD PBMCs

| Metric | Finding | Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Differentially Expressed Genes | 50 immune-related genes | Independent blood & brain tissue studies [14] |

| Severity-Linked Genes | JAK3, CUL2, CARD11 (negative correlation) | Identified within cohort [14] |

| Top Enriched Pathway | TNF signaling pathway | BaseSpace Correlation Engine analysis [14] |

2.2 Proteomic Layer: Systemic Signaling Dysregulation Proteomic analysis of plasma from the same cohort provided direct evidence of disrupted TNF superfamily signaling. It revealed significantly upregulated levels of three key ligands:

- TNFSF10 (TRAIL): Induces apoptosis.

- TNFSF11 (RANKL): Regulates immune cell differentiation and bone metabolism.

- TNFSF12 (TWEAK): Promotes inflammation and cell survival [14]. This systemic elevation points to a broad inflammatory milieu.

Table 2: Upregulated TNF Superfamily Ligands in ASD Plasma

| Ligand | Systematic Name | Primary Functions | Finding in ASD |

|---|---|---|---|

| TRAIL | TNFSF10 | Apoptosis induction | Upregulated [14] |

| RANKL | TNFSF11 | Immune cell differentiation, osteoclastogenesis | Upregulated [14] |

| TWEAK | TNFSF12 | Pro-inflammatory signaling, angiogenesis | Upregulated [14] |

2.3 Single-Cell Resolution: Identifying Cellular Contributors scRNA-seq analysis of PBMCs pinpointed the specific immune subsets potentially responsible for the observed dysregulation. B cells, CD4+ T cells, and NK cells were identified as key contributors to the upregulated TNF-related signals [14]. Furthermore, dysregulated TRAIL, RANKL, and TWEAK signaling pathways were specifically observed in CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, and NK cells of individuals with ASD [14]. This cellular resolution is critical for targeting future therapies.

3. Comparative Discussion: TNF Signaling as a Convergent Pathway The multi-omics data stream presents a coherent narrative: ASD is associated with a distinct peripheral immune signature characterized by the dysregulation of a specific subset of TNF superfamily ligands (TRAIL, RANKL, TWEAK), orchestrated by specific lymphocyte subsets. This contrasts with the broader anti-TNF strategies used in classic immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) like rheumatoid arthritis or Crohn's disease [15] [16]. Notably, while anti-TNF biologics (e.g., Adalimumab, Infliximab) are pillars of treatment for many IMIDs [15] [17], their use is associated with risks like paradoxical autoimmune reactions [17]. The ASD findings suggest a more nuanced dysfunction within the TNF superfamily, potentially necessitating ligand- or receptor-specific antagonism (e.g., targeting TL1A or CD40L) rather than broad TNF-α inhibition [15]. This precision approach, guided by omics data, may offer a safer and more effective therapeutic strategy for neurodevelopmental immune dysregulation.

4. Detailed Experimental Protocols for Validation 4.1 Subject Cohort & Sample Processing (Based on [14])

- Cohort Design: Recruit a well-characterized cohort (e.g., children aged 2-4) with ASD confirmed by DSM-5/ADOS-2 and matched typically developing controls. Exclude subjects with autoimmune diseases, asthma, recent infections, or vaccinations.

- PBMC Isolation: Collect blood in EDTA tubes. Layer blood over Histopaque-1077 at a 1:1 ratio. Centrifuge at 400 × g for 30 min (acceleration 3, brake 0). Collect PBMC layer, wash twice with PBS (400 × g, 10 min). Cryopreserve cells.

- Plasma Preparation: Centrifuge plasma layer at 1,800 × g for 15 min to remove debris. Aliquot and store at -80°C.

4.2 Targeted Transcriptomics (NanoString nCounter) [14]

- RNA Extraction: Use a column-based kit (e.g., Invitrogen Purelink RNA kit) from ~1e6 PBMCs. Assess quality (260/280 ~1.8-2.0).

- Hybridization & Detection: Use the nCounter Human Immune Exhaustion Panel (785 genes). Hybridize 100 ng RNA per sample for 16 hours.

- Data Analysis: Use the Rosalind platform. Normalize using positive/negative controls and housekeeping genes (geNORM algorithm). Perform differential expression analysis (cutoff: |FC| > 1.25, adjusted p < 0.05, Benjamini-Hochberg FDR).

4.3 Proteomic Analysis (Plasma) [14]

- Method: Employ a high-throughput, multiplexed immunoassay platform (e.g., Olink, Luminex) or mass spectrometry-based proteomics to quantify inflammatory proteins.

- Targets: Focus on TNF superfamily ligands (TRAIL, RANKL, TWEAK) and related cytokines.

4.4 Single-Cell RNA Sequencing [14]

- Library Preparation: Use the 10x Genomics Chromium platform for single-cell encapsulation, barcoding, and cDNA library construction from fresh or viably frozen PBMCs.

- Sequencing & Bioinformatics: Sequence on an Illumina platform. Process data using Cell Ranger for alignment and counting. Use Seurat for quality control, normalization, clustering, and differential expression. Annotate clusters using canonical markers (e.g., CD3D/E for T cells, NKG7 for NK cells, MS4A1 for B cells).

5. The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Investigating TNF Signaling in ASD Immunology

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example (From Protocols) |

|---|---|---|

| Histopaque-1077 | Density gradient medium for isolating viable PBMCs from whole blood. | PBMC isolation [14]. |

| nCounter Human Immune Exhaustion Panel | Targeted gene expression panel for profiling 785 immune-related genes without amplification. | Transcriptomic profiling of PBMCs [14]. |

| Anti-TNF Superfamily Ligand Antibodies | For quantifying protein levels via ELISA or multiplex arrays, or for functional blocking assays. | Detecting TRAIL, RANKL, TWEAK in plasma [14]. |

| 10x Genomics Chromium Kit | For high-throughput single-cell RNA sequencing library preparation. | Identifying cell-type-specific contributions [14]. |

| FACS Antibodies (CD3, CD4, CD8, CD56/NCAM) | For fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate pure NK and T cell subsets for downstream omics analysis. | Validating scRNA-seq findings at the protein level. |

6. Visualizing Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: Dysregulated TNF ligand signaling in ASD immune cells.

Diagram 2: Multi-omics workflow for validating immune dysregulation.

Integrating Genomic, Metaproteomic, and Metabolomic Portfolios for Holistic Insights

Multi-Omics Profiling in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings from Multi-Omics ASD Studies

| Omics Approach | Cohort / Model | Major Findings | Key Altered Molecules/Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics & Metaproteomics [18] [5] | 30 children with severe ASD vs. 30 healthy controls | Reduced microbial diversity; Unique association of Tyzzerella; Altered host proteome | Metaproteins: Xylose isomerase, NADH peroxidase. Host Proteins: Kallikrein (KLK1), Transthyretin (TTR) |

| Metabolomics [19] | 499 autistic vs. 209 typically developing (TYP) children | 42 biomarkers identified; Altered cellular bioenergetics; Association with autism severity | Metabolites: Lactate; Pathways: Amino acid, organic acid, acylcarnitine, and purine metabolism |

| Integrated Multi-Omics [3] | Meta-analysis of four ASD GWAS datasets | Identified cross-tissue regulatory mechanisms; Links to immune pathways and gut microbiota | SNPs: rs2735307, rs989134; Pathways: T cell receptor signaling, neutrophil extracellular trap formation |

| Oral Microbiome [20] | 2,154 ASD vs. 1,646 neurotypical siblings | Oral microbiome can discriminate ASD (AUC=0.66); 108 differentiating species; Correlation with IQ | Functional enrichment: Serotonin, GABA, and dopamine degradation pathways |

| Animal Model (Metabolome & Microbiome) [21] | Sodium valproate (SV)-induced autism mouse model | Altered gut microbiota and brain metabolite profiles; Exacerbated anxiety-like behaviors | Pathways: Valine, leucine, isoleucine biosynthesis; glycerophospholipid metabolism; glutathione metabolism |

The integration of genomic, metaproteomic, and metabolomic data is transforming our understanding of complex neurodevelopmental disorders, particularly Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). This multi-omics approach provides a powerful framework for uncovering the intricate biological networks that underlie disease pathophysiology. By simultaneously analyzing the host genome, microbial proteins, and metabolic outputs, researchers can move beyond associative findings to identify mechanistic links within the gut-brain axis [18] [3]. Recent studies demonstrate that this integrated portfolio offers unprecedented insights into the cross-system interactions between genetics, the microbiome, and metabolic function, revealing potential novel diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets for ASD [5] [19].

Comparative analysis of omics technologies reveals their complementary strengths in ASD research. Genomic approaches, including genome-wide association studies (GWAS), have identified numerous genetic risk loci, though these often explain only a portion of ASD heritability [3] [22]. Metaproteomic analyses provide a direct readout of functional microbial activity in the gut, identifying bacterial proteins that may influence host neurodevelopment [18] [23]. Metabolomic profiling captures the final downstream products of cellular processes, offering a dynamic snapshot of physiological status that reflects contributions from both host and microbiome [19] [24]. The true power of this approach emerges when these datasets are integrated, creating a comprehensive model of the biological perturbations in ASD.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Cross-Omics Validation

Integrated Multi-Omics Analysis of Gut Microbiota in ASD

Sample Preparation and Metagenomics: The protocol begins with the collection of fecal samples from participants, typically 30 children with severe ASD and 30 healthy controls matched for age and sex [18] [5]. Total fecal DNA is extracted following the International Human Microbiome Standards (IHMS) guidelines. The V3 and V4 regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene are then amplified using specific primers and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeqDx platform. Bioinformatic analysis of the sequencing data provides insights into microbial community structure, diversity, and taxonomic composition [18].

Metaproteomics Shotgun Analysis: Proteins are purified from fecal samples using a modified filtration-based protocol. Briefly, 1g fecal samples are homogenized in cold PBS, centrifuged to remove debris, and proteins are recovered from the supernatant via acetone precipitation. The protein pellets are dissolved in lysis buffer, and disulfide bonds are reduced with Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP). After another acetone precipitation, the lysate is dissolved in urea buffer and quantified using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. Samples undergo SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by in-gel tryptic digestion. Nano liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis is performed using a TripleTOF 5600+ system, with pre-batch mass calibration ensuring MS accuracy [18].

Untargeted Metabolomics: For metabolite extraction, 100mg fecal samples are used with 400μl of pre-chilled extraction solvent (ACN:MeOH, 3:1). Validation and absolute quantification are performed using amino acid standards. Metabolome profiling is conducted using SWATH-based LC-MS/MS, enabling the identification and quantification of a broad range of small molecules, including neurotransmitters, lipids, and amino acids [18].

Multi-Omics Integration: Data integration employs computational approaches to correlate findings across the genomic, metaproteomic, and metabolomic datasets, identifying interconnected pathways and potential mechanistic relationships between gut microbiota alterations and ASD pathophysiology [18] [5].

Large-Scale Metabolomic Biomarker Identification

Participant Assessment and Sample Collection: The Children's Autism Metabolome Project (CAMP) enrolled 1,102 children ages 18-48 months across 8 clinical sites [19]. Participants underwent comprehensive assessments including the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Second Version (ADOS-2) and the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL). Blood was collected from fasting participants by venipuncture into sodium heparin tubes placed on wet ice. Plasma was obtained after centrifugation and stored at -80°C within 60 minutes of the blood draw. Hemolysis was measured using spectrophotometry, with significantly hemolyzed samples excluded from analysis [19].

Quantitative LC-MS/MS Analysis: Three quantitative LC-MS/MS methods measuring 54 small molecule metabolites were performed in a CLIA-certified laboratory. The methods were analytically validated in compliance with FDA and CLSI guidance for bioanalytical method validation. Quantification of analytes was performed using an Agilent Technologies G6490 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. Analyte measurements below the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) or above the upper limit of quantification (ULOQ) were replaced with 90% of the LLOQ or 110% of the ULOQ value, respectively [19].

Data Analysis: The analysis included both the concentrations of 54 metabolites and their ratios. Metabolite ratio analysis can detect changes or reveal biological processes that may not be discerned by individual metabolites, such as minimal but physiologically relevant alterations in metabolic pathway function [19].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Multi-Omics Integration in ASD Pathophysiology. This pathway illustrates how genomic variants and gut microbiome dysbiosis converge to influence host physiology through metaproteomic and metabolomic changes, ultimately contributing to ASD symptoms via immune and neurodevelopmental alterations.

Diagram 2: Multi-Omics Experimental Workflow. This workflow outlines the parallel processing of different sample types through omics-specific pipelines, followed by integrated computational analysis for cross-omics validation and biomarker discovery.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics ASD Research

| Reagent / Material | Application | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| PureLink Microbiome DNA Purification Kit [18] | Metagenomics | Extracts high-quality DNA from complex fecal samples for 16S rRNA sequencing |

| TripleTOF 5600+ Mass Spectrometer [18] [19] | Metaproteomics & Metabolomics | High-resolution LC-MS/MS system for identifying and quantifying proteins and metabolites |

| cOmplete, Mini, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail [18] | Metaproteomics | Prevents proteolytic degradation during protein extraction from fecal samples |

| N, O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) [21] | Metabolomics (GC-MS) | Chemical derivatization agent for analyzing metabolites by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| Sodium Heparin Blood Collection Tubes [19] | Metabolomics | Preserves plasma metabolites by inhibiting coagulation during blood sample processing |

| Sodium Valproate (SV) [21] | Animal Models | Establishes ASD mouse models for studying metabolic and microbiome alterations |

| MetaPhlAn 3 [20] | Bioinformatic Analysis | Profiling tool for metagenomic data that enables species-level microbial community analysis |

The multi-omics toolkit requires specialized reagents and instruments designed to handle the complexity of biological samples and the diverse nature of the molecules being analyzed. For genomic analyses, optimized DNA purification kits are essential for obtaining high-quality genetic material from challenging sample types like stool [18]. For proteomic and metabolomic workflows, high-resolution mass spectrometry systems like the TripleTOF 5600+ provide the sensitivity and accuracy needed to detect and quantify thousands of proteins and metabolites in parallel [18] [19]. Stabilizing agents such as protease inhibitors and proper blood collection systems are critical for preserving sample integrity and ensuring that analytical results reflect the in vivo state rather than artifacts of sample handling [18] [19].

Bioinformatic tools represent another crucial component of the multi-omics toolkit. Software pipelines like MetaPhlAn 3 enable researchers to process complex metagenomic sequencing data and profile microbial communities at high taxonomic resolution [20]. The integration of these wet-lab and computational tools creates a comprehensive platform for generating and analyzing multi-omics data, facilitating the discovery of robust biomarkers and pathological mechanisms in ASD. As these technologies continue to evolve, they are expected to become more accessible and standardized, further advancing our ability to understand and intervene in complex disorders like ASD through integrated molecular profiling.

Advanced Analytical Frameworks for Cross-Omics Data Integration and Causal Inference

Multi-omics Mendelian Randomization (MR) represents a transformative approach in computational biology that integrates genetic instruments with multiple molecular data layers to establish causal directionality from genetic variants to complex phenotypes. This methodology is particularly valuable in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) research, where heterogeneous genetic risk factors interact with complex biological systems across tissues. By employing genetic variants as instrumental variables to infer causal relationships, multi-omics MR minimizes confounding and reverse causation biases that often plague observational studies [25] [26]. The framework systematically integrates data from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) with expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), methylation QTLs (mQTLs), and protein QTLs (pQTLs) to elucidate mechanistic pathways from genetic variation to phenotypic expression [27] [28].

In the context of autism research, this approach enables researchers to dissect the complex "gut microbiota-immune-brain axis" and other system-level interactions that underlie ASD pathophysiology [3]. Recent studies have demonstrated how multi-omics MR can identify cross-tissue regulatory mechanisms where genetic variants exert pleiotropic effects through multiple biological pathways, including gut microbiota composition, immune activation, and neuronal gene regulation [3] [5]. This integration provides a powerful framework for validating autism findings across omics layers and establishing robust causal inference for therapeutic target identification.

Comparative Analysis of Multi-Omics MR Methodologies

Methodological Approaches and Applications

Table 1: Comparison of Multi-Omics Mendelian Randomization Methods

| Method | Key Features | Optimal Use Cases | ASD Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two-Sample MR | Uses independent exposure/outcome datasets; multiple sensitivity analyses [29] | Initial causal screening; protein-disease relationships | Causal effects between gut microbiota and ASD [3] |

| Summary-data-based MR (SMR) | Integrates eQTL/mQTL/pQTL with GWAS; HEIDI test distinguishes pleiotropy from linkage [28] | Gene prioritization; multi-omics integration | Identifying cross-tissue regulatory mechanisms in ASD [3] |

| MR-link-2 | Handles single-region instruments; robust to horizontal pleiotropy [30] | Molecular exposures with limited genetic instruments | Not specifically reported in ASD contexts yet |

| PheWAS-Clustering MR (PWC-MR) | Clusters instruments by phenome-wide profiles; reveals heterogeneous effects [26] | Complex exposures with multiple biological pathways | Potential application for ASD comorbidities |

| Bidirectional MR | Tests reverse causation; establishes directionality [3] | Gut-brain axis communication; temporal relationships | ASD-gut microbiota bidirectional relationships [3] |

Performance Metrics and Technical Considerations

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Multi-Omics MR Methods

| Method | Type 1 Error Control | Statistical Power | Pleiotropy Robustness | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-Sample MR | Moderate (requires careful IV selection) | High with strong instruments | Variable; depends on sensitivity analyses | GWAS summary statistics for exposure/outcome |

| SMR | Good with HEIDI filtering | High for cis-regions | Moderate; HEIDI test identifies linkage | QTL and GWAS summary statistics with LD reference |

| MR-link-2 | Excellent (calibrated T1E) [30] | High for single regions [30] | High (explicitly models pleiotropy) [30] | Summary statistics with LD reference |

| PWC-MR | Good with proper clustering | Moderate (depends on cluster separation) | High by grouping pleiotropic pathways | GWAS and phenome-wide data |

| Bidirectional MR | Good with balanced samples | Moderate for bidirectional effects | Moderate (assumes balanced pleiotropy) | Independent datasets for both directions |

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics MR in Autism Research

Core Analytical Workflow

The standard workflow for multi-omics MR in autism research integrates data from multiple molecular layers through a structured analytical pipeline. A recent study investigating cross-tissue regulatory mechanisms in ASD exemplifies this approach, combining meta-analysis of GWAS data with Polygenic Priority Score analysis, brain region eQTL enrichment, and SMR analyses of brain cis-eQTL and mQTL [3]. This is further extended through bidirectional MR analyses of gut microbiota and SMR analysis of blood eQTL to establish comprehensive biological pathways.

The essential quality control steps include stringent instrumental variable selection (typically p < 5×10⁻⁸), linkage disequilibrium clumping (r² < 0.001 within 10,000 kb windows), and exclusion of palindromic SNPs [3] [27]. For ASD applications, special attention is paid to cross-tissue consistency, with validation using tissue-specific QTLs from relevant brain regions and peripheral tissues. The heterogeneity in dependent instruments (HEIDI) test is routinely applied with a significance threshold of p < 0.01 to distinguish pleiotropy from linkage [28].

Cross-Omics Validation Protocol for Autism Findings

The validation of autism findings through multi-omics MR requires a systematic approach to establish consistency across biological layers. A recent study exemplifies this protocol by first identifying genetic loci through meta-analysis of multiple ASD GWAS datasets, then applying SMR with brain cis-eQTL and mQTL data, followed by bidirectional MR with gut microbiota, and finally integrating blood eQTL data to identify immune pathway regulatory effects [3]. This creates a cross-validated evidence chain connecting genetic variants to molecular intermediates and ultimately to ASD pathophysiology.

The validation protocol includes several critical steps: (1) multi-omics concordance testing where signals must be consistent across methylation, expression, and protein levels; (2) tissue-specific replication using relevant tissues such as brain regions (prefrontal cortex, cerebellum) and gut tissues; (3) sensitivity analyses including MR-Egger, MR-PRESSO, and leave-one-out analyses to verify robustness to pleiotropy; and (4) colocalization testing to ensure shared causal variants across omics layers (PPH4 > 0.7) [27] [28]. For ASD specifically, additional validation includes testing the gut microbiota-immune-brain axis through bidirectional MR and examining enrichment in neuronal development pathways [3].

Biological Pathways in Autism Revealed by Multi-Omics MR

Key Signaling Pathways and Mechanisms

Multi-omics MR studies have identified several crucial biological pathways in autism spectrum disorder, with emerging evidence highlighting the gut microbiota-immune-brain axis as a central mechanism. This pathway involves genetic variants that influence gut microbiota composition, which in turn activates immune pathways such as T cell receptor signaling and neutrophil extracellular trap formation, ultimately affecting neurodevelopmental processes in the brain [3]. Specific genes identified through this approach include HMGN1 and H3C9P, which are cis-regulated in brain tissues and interact with gut microbiota through immune mediation.

Another significant pathway involves DNA methylation regulation of neuronal genes, where mQTLs influence methylation status of genes like QDPR, DBI, and MAX, subsequently altering their expression and contributing to neurodevelopmental abnormalities in ASD [28]. This epigenetic regulation creates a mechanistic bridge between genetic risk factors and functional gene expression changes, with specific CpG sites such as cg0880851 in QDPR and cg11066750 in DBI showing significant causal effects on ASD-related phenotypes.

Quantitative Evidence from Autism Multi-Omics Studies

Table 3: Effect Estimates for Key Causal Relationships in ASD Pathways

| Exposure | Outcome | MR Method | Effect Size (OR/β) | 95% CI | P-value | Omics Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZDHHC20 expression | Schizophrenia risk | Two-sample MR | OR = 1.24 | 1.02-1.51 | < 0.05 | Transcriptome [25] |

| DNA methylation (cg18095732) | ZDHHC20 regulation | Mediation MR | β = 0.31 | 0.15-0.47 | < 0.05 | Epigenome [25] |

| CCR7 on CD8+ T cells | Schizophrenia risk | Mediation MR | OR = 1.18 | 1.05-1.33 | < 0.05 | Immunome [25] |

| DBI protein levels | Ulcerative colitis | SMR | OR = 0.79 | 0.69-0.90 | < 0.001 | Proteome [28] |

| MAX protein levels | Ulcerative colitis | SMR | OR = 0.74 | 0.62-0.90 | < 0.001 | Proteome [28] |

| Gut microbiota diversity | ASD risk | Bidirectional MR | β = -0.42 | -0.67- -0.17 | < 0.001 | Microbiome [3] |

| Tyzzerella abundance | ASD symptoms | Metaproteomics | RR = 2.31 | 1.78-3.01 | < 0.001 | Microbiome [5] |

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for Multi-Omics MR Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Resources | Key Features | Application in ASD Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS Data | iPSYCH-PGC ASD dataset [3], FinnGen [27], UK Biobank [28] | Large sample sizes; diverse phenotypes | ASD genetic risk identification; pleiotropy assessment |

| QTL Databases | eQTLGen [27], GTEx [28], GoDMC mQTL [25], UKB-PPP pQTL [27] | Multiple tissues; large sample sizes | Cross-tissue regulation; molecular mechanism identification |

| Analytical Tools | SMR [28], MR-link-2 [30], PWC-MR [26], COLOC [29] | Pleiotropy robustness; causal inference | Method-specific advantages for different study designs |

| Microbiome Data | MiBioGen [3], curated metaproteomics [5] | Taxonomic profiling; functional potential | Gut-brain axis mechanisms in ASD |

| Validation Resources | Single-cell RNA-seq [29], molecular docking [29], functional assays | Experimental validation; therapeutic targeting | Functional follow-up of MR discoveries |

Practical Implementation Considerations

Successful implementation of multi-omics MR in autism research requires careful attention to several methodological considerations. First, sample size requirements must be met for adequate statistical power, with current standards suggesting minimums of 10,000 cases for ASD GWAS and similar scales for QTL mapping [3] [27]. Second, population stratification must be controlled through ancestry-matched samples and LD reference panels, with most current resources optimized for European ancestry populations. Third, instrument strength must be verified through F-statistics > 10 to avoid weak instrument bias [29] [27].

For autism-specific applications, special consideration should be given to tissue relevance, with priority given to brain region QTLs (particularly from cortical regions and cerebellum) alongside peripheral tissues that may reflect accessible biomarkers [28]. The integration of gut microbiome data presents unique challenges due to the complexity of microbial community measurements, requiring careful attention to taxonomic resolution and potential confounders such as diet and medication use [3] [5]. Finally, functional validation strategies should be planned from the outset, leveraging emerging resources such as single-cell RNA-seq of human brain development and organoid models to test predictions from MR analyses in biologically relevant systems.

Cross-Platform Omics Prediction (CPOP) is an advanced statistical machine learning framework specifically designed to overcome one of the most significant challenges in modern precision medicine: the lack of transferability of molecular signatures across different measurement platforms and institutions [31] [32]. In an era where high-throughput omics technologies can generate vast molecular datasets for individual patients, the clinical deployment of predictive models has been hampered by technical variations introduced by different platforms, protocols, and centers [31]. CPOP addresses this fundamental limitation through an innovative approach that creates platform-independent prognostic models, enabling reliable predictions across diverse datasets without requiring re-normalization or re-training [33] [32].

The framework is particularly valuable for autism research, where the integration of multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) with neuroimaging findings requires robust methods that can transcend platform-specific biases [34]. As researchers strive to develop biological markers for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) that complement behavioral assessments, CPOP provides a methodological foundation for creating models that maintain predictive accuracy across different laboratories and measurement technologies [34] [35]. This capability is crucial for validating autism findings across multiple studies and populations, ultimately accelerating the translation of omics discoveries into clinically useful tools.

CPOP vs. Traditional Methods: A Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Differences in Approach

CPOP differs from traditional omics prediction methods through several foundational innovations. While conventional approaches typically use absolute gene expression values as features, CPOP employs ratio-based features that capture relative expression differences between gene pairs [31] [32]. This strategy eliminates the need for pre-determined control genes and creates features that are inherently more stable across platforms. Additionally, CPOP incorporates feature stability weights during selection and prioritizes features with consistent effect sizes across multiple datasets, further enhancing transferability [32].

Traditional prediction models often demonstrate excellent performance on their training data but suffer significant degradation when applied to external validation datasets due to technical variations [31]. CPOP specifically addresses this limitation by designing the feature selection process to identify biological signals that remain consistent despite technical noise, rather than attempting to remove all unwanted variation [32]. This conceptual shift enables the development of models that maintain predictive accuracy across different measurement platforms and experimental conditions.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance comparison between CPOP and traditional methods in melanoma prognosis

| Method | Training Data | Validation Data | Prediction Accuracy | Transferability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPOP | MIA-Microarray & MIA-NanoString | TCGA Melanoma | High (similar to within-data prediction) | Excellent (no scale adjustment needed) |

| Traditional Lasso | MIA-Microarray & MIA-NanoString | TCGA Melanoma | Significant scale differences | Poor (requires re-normalization) |

| CPOP | MIA-Microarray & MIA-NanoString | Sweden Dataset | Consistent hazard ratios | High correlation with within-data predictions |

| Volume-based Classification | Regional brain volumes | Independent ASD sample | 74% accuracy, AUC = 0.77 | Limited cross-platform performance |

| Thickness-based Classification | Regional cortical thickness | Independent ASD sample | 87% accuracy, AUC = 0.93 | Limited cross-platform performance |

The performance advantages of CPOP become evident when examining its application in melanoma prognosis research. When applied to transcriptomics data from stage III melanoma patients, CPOP demonstrated remarkable transferability across different gene expression platforms including Illumina cDNA microarray and NanoString nCounter [31]. In contrast, traditional Lasso regression exhibited significant scale differences between cross-platform and within-platform predictions, limiting its clinical utility for multi-center validation [31].

In autism research, while not directly implementing CPOP methodology, studies have highlighted the importance of transferable models. For instance, research using surface-based morphometry of cortical thickness achieved 87% classification accuracy for ASD compared to 74% with volume-based classification [34]. However, these models still face platform transferability challenges that CPOP could potentially address through its ratio-based feature construction and stability-weighted selection process.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

CPOP Workflow and Technical Execution

The CPOP procedure follows a structured five-step workflow designed to maximize model transferability [31] [32]. The initial step involves identifying multiple datasets with similar clinical outcomes, which may come from public repositories or newly generated experiments. For autism research, this could include transcriptomic, genomic, or neuroimaging data from different research cohorts [34] [35]. The second step creates ratio-based features by calculating the expression ratio of each gene pair, transforming absolute expression values into relative measures that are less sensitive to platform-specific technical variations.

The third step identifies ratio features associated with clinical outcomes, while the fourth incorporates stability weights that measure feature consistency across datasets. The final step employs regularized regression modeling to select features with consistent effect sizes, constructing the final predictive model [31]. This comprehensive approach ensures that the resulting model captures robust biological signals rather than platform-specific technical artifacts.

Experimental Validation Framework

To validate CPOP's transferability, researchers have developed a rigorous evaluation protocol that compares cross-data predictions with within-data performance [31]. This involves constructing a model using one dataset (Dataset A) and applying it directly to a different dataset (Dataset B) without re-normalization, generating "cross-data predicted outcomes." These results are then compared to the ideal scenario where a model is built and applied to the same dataset (Dataset B), producing "within-data prediction outcomes" [31].

For autism research applications, this validation framework could be implemented using multiple neuroimaging or transcriptomic datasets from different research centers. A transferable model demonstrates high concordance between cross-data and within-data predictions, with data points clustering along the identity line (y=x) on scatter plot comparisons [31]. This validation approach provides compelling evidence of model robustness and directly addresses the reproducibility crisis affecting many omics-based biomarker discoveries.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 2: Essential research reagents and platforms for CPOP implementation

| Category | Specific Tool/Platform | Function in CPOP Workflow | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Omics Measurement Platforms | NanoString nCounter | Generates gene expression data for model building | Clinical-ready molecular assay deployment [31] |

| Omics Measurement Platforms | Illumina cDNA Microarray | Provides transcriptomic data for feature identification | Initial biomarker discovery [31] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | R Programming Language | Implements CPOP algorithm and statistical analysis | Primary computational environment [33] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | FreeSurfer Software Suite | Extracts neuroimaging features (cortical thickness) | Autism neuroimaging studies [34] |

| Data Resources | Public Repository Datasets (e.g., TCGA) | Independent validation cohorts | Model transferability testing [31] |

| Computational Methods | Regularized Regression (Lasso) | Selects predictive features with consistent effects | Final model construction [31] [32] |

| Computational Methods | Logistic Model Trees (LMT) | Alternative classification algorithm | Performance comparison [34] |

The successful implementation of CPOP requires both experimental platforms for data generation and computational tools for analysis. The NanoString nCounter platform has been specifically utilized as a clinical-ready molecular assay for CPOP implementation due to its low per-assay cost and widespread deployment [31]. This technology enables the translation of discovered molecular signatures into practical clinical tools. For computational implementation, CPOP is available as an R package (CPOP) that can be installed directly from GitHub, making the method accessible to researchers without requiring extensive programming expertise [33].

In autism research, additional specialized tools may be required depending on the data modalities being integrated. The FreeSurfer software suite enables the extraction of cortical thickness measurements from structural MRI data, which have shown superior classification performance for ASD compared to volumetric measures [34]. Machine learning algorithms such as random forests and support vector machines can complement the CPOP framework when analyzing high-dimensional phenotypic data, such as language milestone acquisition patterns in children with ASD [36].

Application to Autism Research Validation

Integrating Multiple Data Modalities

The CPOP framework offers significant potential for addressing validation challenges in autism research by enabling the development of models that integrate findings across different omics platforms and research centers [34] [35]. Autism spectrum disorder exhibits substantial heterogeneity in both clinical presentation and underlying biology, necessitating approaches that can identify robust signals across diverse datasets [35] [36]. CPOP's ratio-based feature construction could be applied to various autism biomarker candidates, including cortical thickness measures from neuroimaging, gene expression signatures from transcriptomic studies, or protein biomarkers from proteomic analyses.

Research has demonstrated that cortical thickness-based classification outperforms volume-based approaches for ASD identification, achieving 87% accuracy with AUC of 0.93 [34]. Similarly, pre- and perinatal risk factors have been incorporated into clinical risk score models with AUC of 0.711 for autism prediction [35]. However, these approaches would benefit from CPOP's transferability features when attempting validation across multiple research sites with different measurement protocols and platforms.

Pathway to Clinical Translation

The application of CPOP to autism research aligns with growing recognition that biological validation of ASD findings requires methods that transcend platform-specific effects [35] [36]. By implementing CPOP's ratio-based approach with established autism biomarkers, researchers could develop more reliable models for early detection, severity stratification, and treatment response prediction. For instance, specific language milestones such as "Identifies 1 picture" and "Expresses demands by language" in children under 4 years, and "Identifies 2 colors" and "Calls partner by name" in older children have demonstrated predictive value for ASD severity [36]. Transforming these behavioral markers using CPOP's stability-weighted approach could enhance their utility across diverse clinical settings and populations.

The ultimate goal for CPOP in autism research is the development of clinically implementable tools that combine multiple data modalities into unified predictive models. These tools could potentially lower the age of reliable autism prediction by incorporating pre- and perinatal risk factors with biological measurements [35], while maintaining accuracy across different healthcare settings and measurement platforms. This approach represents a promising pathway for addressing the reproducibility challenges that have hampered the translation of autism biomarkers into clinical practice.

The integration of polygenic risk scores (PRS), Mendelian Randomisation Scores (MRS), and expression risk scores (ERS) represents a paradigm shift in predictive genomics for complex neurodevelopmental conditions. By moving beyond single-omic approaches, multi-omics risk scores enhance our ability to decipher the intricate etiological architecture of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). This guide objectively compares the performance, applications, and methodological considerations of these integrated approaches, highlighting how their synergy provides superior predictive power and biological insight compared to any single methodology alone. Cross-omics validation within ASD research consistently demonstrates that combined models improve stratification of developmental trajectories and identification of actionable biological pathways.

Autism spectrum disorder exemplifies the complexity of neurodevelopmental conditions where genetic, regulatory, and environmental factors interact through cross-tissue regulatory networks [37]. Traditional genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified numerous risk loci, but these often exhibit modest predictive power individually and insufficiently capture the systemic nature of ASD pathophysiology [38]. Multi-omics risk scores address these limitations by integrating signals from multiple biological layers, enabling a more comprehensive quantification of risk that accounts for the interplay between different omics levels.

The fundamental components of multi-omics risk scores include:

- Polygenic Risk Scores (PRS): Aggregate the effects of thousands of common genetic variants across the genome, providing a measure of overall genetic susceptibility [39].

- Mendelian Randomisation Scores (MRS): Leverage genetic variants as instrumental variables to infer causal relationships between modifiable risk factors and ASD, bridging observational and causal inference [39] [37].

- Expression Risk Scores (ERS): Incorporate information from expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) that regulate how genetic variants influence gene expression across tissues, highlighting potentially actionable regulatory pathways [40] [41].

Within autism research, multi-omics frameworks have revealed that genetic risk loci operate through cross-tissue mechanisms involving the gut microbiota-immune-brain axis, providing a systems-level understanding of ASD pathogenesis [4] [37].

Comparative Performance of Omics Approaches

Predictive Accuracy Across Methodologies

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Single and Multi-Omics Approaches in Autism Prediction

| Approach | AUC Range | Key Strengths | Significant Limitations | Sample Applications in ASD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRS Alone | 0.55-0.60 | Captures polygenic background; Applicable to population screening | Limited by GWAS sample size; Poor fine-mapping resolution; Unable to establish causality | Population stratification; Genetic correlation estimates [39] |

| MRS Alone | N/A (causal inference) | Establishes causal direction; Reduces confounding; Informs intervention targets | Requires strong instrumental variables; Vulnerable to pleiotropy; Limited by eQTL discovery sample sizes | Testing causality in gut microbiota-ASD relationships [37] |

| ERS Alone | 0.58-0.63 | Tissue-specific functional insights; Highlights regulatory mechanisms | Tissue specificity limits generalizability; Dynamic nature of gene expression | Identifying regulatory consequences of ASD risk variants in brain tissue [40] [41] |

| Integrated Multi-Omics | 0.65-0.68 | Superior predictive power; Cross-tissue pathway identification; Systems-level insights | Computational complexity; Increased multiple testing burden; Requires large multi-omics datasets | Predicting intellectual disability in ASD; Mapping gut-immune-brain pathways [42] [37] |

Empirical Performance Data in Autism Cohorts

Recent large-scale studies provide quantitative evidence supporting the enhanced predictive performance of multi-omics approaches. A prognostic study integrating five classes of genetic variants with developmental milestones achieved an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.65 for predicting intellectual disability (ID) in autistic children, correctly identifying 10% of ID cases with positive predictive values of 55% [42]. This performance significantly exceeded models based on individual omics layers alone, demonstrating the clinical relevance of combined approaches for anticipating developmental trajectories in ASD.

The integration of multi-omics data has been particularly valuable for elucidating the cross-tissue regulatory mechanisms of autism risk loci. Research incorporating brain cis-eQTL, methylation QTL (mQTL), and blood eQTL data identified specific SNPs (rs2735307 and rs989134) that operate through the gut microbiota-immunity-brain axis, participating in immune pathways such as T cell receptor signaling and neutrophil extracellular trap formation while cis-regulating neurodevelopmental genes like HMGN1 and H3C9P [37]. This cross-scale evidence chain provides a theoretical foundation for precision medicine in ASD.

Table 2: Cross-Omics Validation Findings in Autism Research

| Omics Integration | Key Findings | Biological Pathways Identified | Clinical Translation Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRS + Developmental Milestones | 2-fold higher stratification of ID probabilities in individuals with delayed milestones vs typical development [42] | Neurodevelopmental constraint genes; Polygenic architectures | Early identification of ASD cases at risk for comorbid intellectual disability |

| eQTL + mQTL + Gut Microbiota | SNPs exert cross-tissue regulation through gut microbiota-immune-brain axis [37] | T cell receptor signaling; Neutrophil extracellular trap formation; Epigenetic methylation modifications | Targets for modulating gut-brain axis signaling |

| Rare variants + PRS | Combinations of typically non-relevant variants achieved PPVs of 55% for ID prediction [42] | Constrained genes intolerant to variation (LOEUF < 0.35) | Improved genetic counseling through variant reinterpretation |

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Integration

Protocol 1: Integrated Multi-Omics Risk Score Development

Objective: To develop and validate a multi-omics risk score that combines PRS, MRS, and ERS for predicting intellectual disability in autistic individuals.

Sample Requirements: Large ASD cohorts with genomic data and phenotypic information about cognitive outcomes. The protocol described by [42] analyzed 5,633 autistic participants with genetic data and ID assessment from SPARK, Simons Simplex Collection, and MSSNG cohorts.

Methodology:

- PRS Calculation: Compute polygenic scores for cognitive ability and autism using LD-pruning and P-value thresholding with weights from large GWAS summary statistics [42] [39].

- Rare Variant Annotation: Identify rare copy number variants, de novo loss-of-function, and missense variants impacting constrained genes (LOEUF < 0.35) [42].

- MRS Analysis: Perform bidirectional Mendelian randomization between gut microbiota features and ASD risk using instruments from microbiota GWAS (473 microbial taxa) [37].

- ERS Development: Integrate brain cis-eQTL and mQTL data using summary-data-based Mendelian randomization (SMR) to identify expression risk profiles [40] [37].

- Model Integration: Combine all predictors using multiple logistic regression with cross-validation (10-fold) and assess out-of-sample performance in independent cohorts.

Validation: Evaluate prediction performance using AUROC, positive predictive values, and negative predictive values with bootstrapping (10,000 iterations) for confidence intervals [42].

Protocol 2: Cross-Tissue Regulatory Network Mapping

Objective: To identify how ASD risk loci exert cross-tissue effects through the gut microbiota-immune-brain axis.

Methodology:

- Meta-Analysis: Conduct cross-study GWAS meta-analysis using fixed-effects models in METAL software, with genomic coordination to hg38 and allele alignment [37].

- Novel Locus Screening: Exclude known loci (±500 kb) and perform linkage disequilibrium pruning (r² < 0.001 within 10,000 kb window) to identify novel associations [37].

- Multi-Omic Enrichment:

- Conduct Polygenic Priority Score (PoPS) analysis for gene prioritization

- Perform brain region and brain cell eQTL enrichment analyses

- Integrate brain cis-eQTL and mQTL using SMR

- Combine blood eQTL data to identify immune pathway associations [37]

- Causal Inference: Apply bidirectional MR between gut microbiota composition and ASD using inverse-variance weighted methods with sensitivity analyses (MR-Egger, MR-PRESSO) [37].

Figure 1: Workflow for Multi-Omics Risk Score Development and Validation

Biological Pathways and Systems Identified Through Multi-Omics