Validating Autism Spectrum Disorder Genes through Protein Interaction Networks: Systems Biology Approaches and Clinical Translation

This comprehensive review explores the critical role of protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis in validating Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) risk genes.

Validating Autism Spectrum Disorder Genes through Protein Interaction Networks: Systems Biology Approaches and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the critical role of protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis in validating Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) risk genes. We examine systems biology approaches that integrate multi-omic data to prioritize candidate genes, focusing on network topology metrics like betweenness centrality and machine learning integration. The article details methodological frameworks for constructing neuronal-specific interactomes and validating predictions through experimental models. By comparing computational predictions with experimental evidence and clinical data, we highlight how network validation bridges the gap between genetic discoveries and therapeutic development, offering researchers and drug development professionals actionable insights for translating network biology into clinical applications.

Building the Blueprint: Systems Biology Foundations for ASD Gene Discovery

The Complex Genetic Architecture of Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) represents a complex neurodevelopmental condition with a highly heterogeneous genetic architecture. While hundreds of risk genes have been identified, understanding how these diverse genetic factors converge on common biological pathways remains a central challenge in the field. The traditional single-gene approach has proven insufficient for unraveling this complexity, leading researchers to adopt protein interaction network validation as a crucial methodology. This approach moves beyond gene-level associations to map the physical interactions and functional relationships between proteins encoded by ASD risk genes, revealing convergent molecular pathology despite genetic heterogeneity.

Recent technological advances have enabled the construction of cell-type-specific protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks in human neurons, revealing that approximately 90% of neurally relevant PPIs were previously unknown [1] [2]. This discovery emphasizes the critical importance of experimental PPI mapping in disease-relevant cell types rather than relying solely on literature-curated interactions, which are often incomplete and carry inherent biases [3]. The integration of these network-based approaches with machine learning algorithms is now bridging the gap between basic transcriptomic discoveries and clinical applications, potentially leading to improved biomarkers and therapeutic targets [4].

Methodological Approaches for Protein Interaction Network Validation

Experimental Systems for Network Mapping

The validation of protein interaction networks in ASD research employs multiple complementary experimental approaches, each with distinct methodologies and applications. The table below summarizes the core experimental protocols used in key recent studies.

Table 1: Experimental Methodologies for Protein Interaction Network Validation in ASD Research

| Methodology | Core Technique | Cell/Tissue System | Key Advantages | Primary Validation Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity Purification Mass Spectrometry (AP-MS) [1] | Immunoprecipitation combined with LC-MS/MS quantification | Human stem-cell-derived neurogenin-2 induced excitatory neurons (iNs) | Captures endogenous protein complexes in relevant cell type; high specificity | Replication (80%) in independent experiments; western blot validation |

| Yeast-Two-Hybrid (Y2H) Screening [3] | Binary interaction mapping in yeast system | Cloned brain-expressed splicing isoforms | Tests direct physical interactions; accommodates isoform-specific interactions | Multiple retests (≥3/4 positive); mammalian PPI trap assay orthologous validation |

| Mammalian Protein-Protein Interaction Trap (MAPPIT) [3] | Cytokine receptor reconstitution in mammalian cells | Heterologous system (HEK293) | Orthologous validation in mammalian cellular environment | Benchmarking against positive and random reference sets |

| Neuronal Proteomics in Mouse Models [1] | Immunoprecipitation from brain tissue | Mouse cortical neurons | In vivo relevance; conservation across species | Comparison with human neuronal networks |

Computational and Bioinformatics Integration

Complementing experimental approaches, computational methods have become increasingly sophisticated for analyzing and validating protein interaction networks. Network propagation techniques applied to protein-protein interaction networks have demonstrated high accuracy in predicting ASD-associated genes, achieving an area under the ROC curve of 0.87 and area under the precision-recall curve of 0.89 [5]. This method integrates multiple genomic data types—including GWAS, differential gene expression, alternative splicing changes, and differential methylation—by using known ASD-related genes as seeds to pinpoint other genes with high network proximity.

The random forest model has emerged as a particularly powerful tool for integrating network-based features. When trained on SFARI Gene Scoring categories, this machine learning approach successfully identified high-confidence ASD genes while outperforming previous prediction methods [5]. Functional enrichment analysis of top predicted genes reveals significant association with biological processes including chromatin organization, histone modification, and neuron cell-cell adhesion—pathways repeatedly implicated in ASD pathophysiology [5].

Key Validated Networks and Their Biological Significance

Neuronal Protein Interaction Networks

Groundbreaking work by Pintacuda et al. (2023) established human neuronal protein-protein interaction networks for 13 high-confidence ASD risk genes, identifying over 1,000 interactions in induced human neurons [1] [2]. Remarkably, approximately 90% of these interactions were novel, underscoring the limitation of previous networks built from non-neural cell lines or literature curation. This network revealed several key biological insights:

- Limited direct connectivity: The 13 index proteins showed little overlap in their interacting partners, suggesting diverse molecular functions despite their association with a common disorder [1].

- Central connector complexes: Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins (IGF2BP1-3), which form an m6A-reader complex, emerged as highly interconnected nodes, interacting with at least 5 index proteins each and potentially serving as convergence points in ASD pathology [1].

- Isoform-specific interactions: Investigation of ANK2 isoforms revealed that a neuron-specific transcript containing a giant exon (exon 37) was required for numerous disease-relevant interactions, providing mechanistic insight into how mutations in this exon increase ASD risk [1].

Table 2: Key Validated Protein Complexes in ASD Neuronal Networks

| Complex/Module | Core Components | Biological Function | Network Properties | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGF2BP m6A-reader complex [1] | IGF2BP1, IGF2BP2, IGF2BP3 | mRNA modification and regulation | Highly interconnected hub; interacts with ≥5 index ASD proteins | Co-immunoprecipitation in human iNs |

| Chromatin remodeling module [5] | Multiple histone family genes | Chromatin organization; histone modification | Functional enrichment in predicted ASD genes | Gene set enrichment analysis |

| Synaptic vesicle trafficking hub [6] | Proteins involved in synaptic transmission | Synaptic vesicle trafficking and membrane excitability | Highly connected nodes in co-expression networks | Differential expression in PTHS neural cells |

| Cell adhesion complex [5] | Neuronal cell-cell adhesion proteins | Neuronal connectivity and synaptic formation | Enriched in functional annotation of network-predicted genes | Integration of multiple omic datasets |

Alternative Splicing Networks

The Autism Spliceform Interaction Network (ASIN) represents a pioneering effort to map interactions between naturally occurring brain-expressed alternatively spliced isoforms of ASD risk genes [3]. This approach cloned 373 brain-expressed splicing isoforms corresponding to 124 autism candidate genes, with over 60% representing novel isoforms not previously annotated in major databases. Key findings include:

- Isoform-specific interactions: The ASIN revealed that almost half of the detected interactions and approximately 30% of newly identified interacting partners represented contributions from splicing variants, emphasizing that isoform-specific networks provide critical detail beyond gene-level analyses [3].

- CNV connectivity: The isoform-based network directly connected genes from a large number of ASD-relevant copy number variations (CNVs) into a single connected component, suggesting potential mechanistic links between genetically distinct ASD cases [3].

- Validation rigor: The network employed a rigorous four-stage retesting protocol for all corresponding protein isoforms, controlling for potential biases arising from sampling sensitivity, with orthogonal validation using mammalian protein-protein interaction trap assays [3].

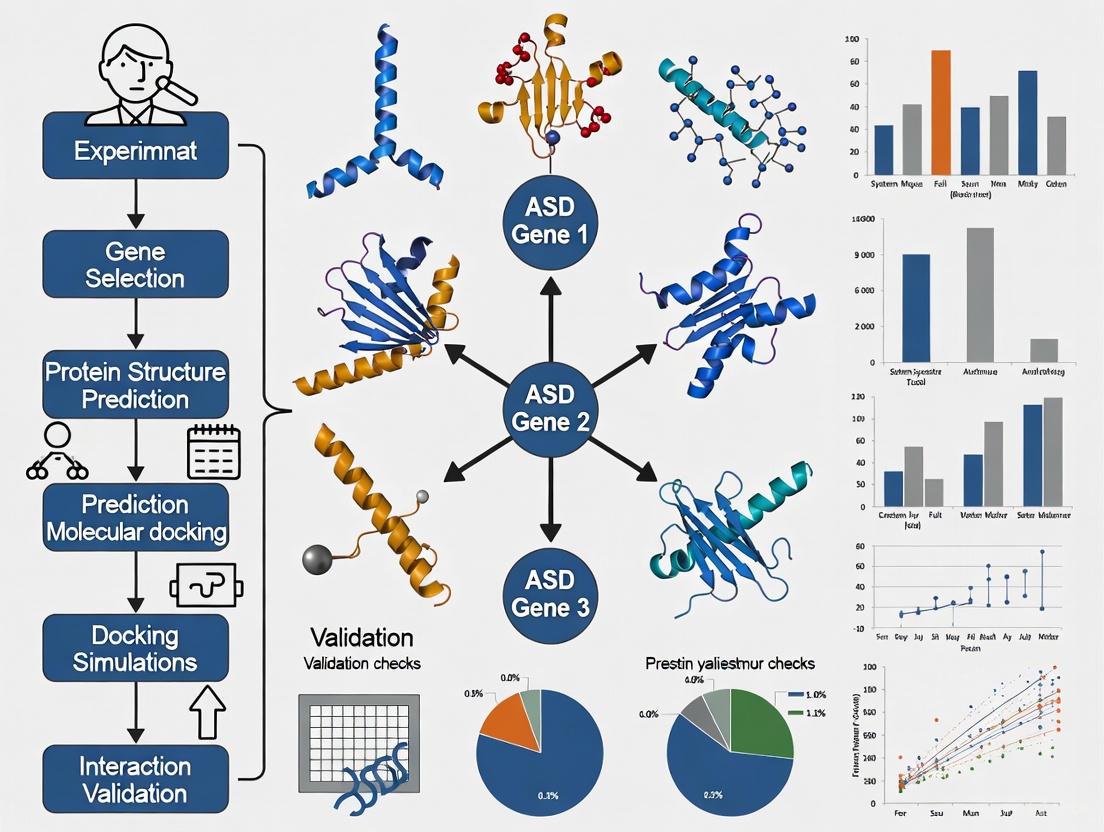

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for constructing and validating the Autism Spliceform Interaction Network:

Integration with Genetic and Phenotypic Heterogeneity

Genetic Architecture Informing Phenotypic Diversity

Recent large-scale studies have demonstrated that the genetic architecture of ASD directly corresponds to its phenotypic heterogeneity. Through generative mixture modeling of 239 phenotypic features across 5,392 individuals, four robust phenotypic classes have been identified [7]:

- Social/behavioral (n=1,976): High scores across core autism categories plus disruptive behavior, attention deficit, and anxiety, without developmental delays.

- Mixed ASD with DD (n=1,002): Nuanced presentation with strong enrichment of developmental delays.

- Moderate challenges (n=1,860): Consistently lower scores across all measured categories compared to other autistic children.

- Broadly affected (n=554): Consistently higher scores across all categories.

Remarkably, these phenotypic classes demonstrate distinct genetic profiles. Analysis of de novo and rare inherited variation reveals diverging genetic patterns across gene sets and pathways corresponding to these classes [7]. Furthermore, class-specific differences in the developmental timing of affected genes align with clinical outcome differences, suggesting that rare variation is associated with class-specific gene expression patterns during development [7].

Polygenic Profiles and Cognitive Correlations

The polygenic architecture of ASD can be decomposed into two modestly genetically correlated (r_g = 0.38) factors associated with different developmental trajectories and cognitive profiles [8]:

- Factor 1: Associated with earlier autism diagnosis and lower social and communication abilities in early childhood, moderately genetically correlated with ADHD and mental-health conditions.

- Factor 2: Associated with later autism diagnosis and increased socioemotional and behavioural difficulties in adolescence, with moderate to high positive genetic correlations with ADHD and mental-health conditions.

Bidirectional genetic overlap analyses reveal a complex relationship between ASD and cognitive traits. While there is a modest positive genetic correlation between ASD and both educational attainment (rg = 0.21) and intelligence (rg = 0.22) at the global level, the MiXeR method demonstrates that these traits share thousands of genetic variants with mixed effect directions [9]. Specifically, 12.7k genetic variants are associated with ASD, of which 12.0k are shared with educational attainment and 11.1k with intelligence, with 59-68% of estimated shared loci having concordant effect directions [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ASD Network Validation Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Research Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human ORFeome 5.1 [3] | ~15,000 open reading frames | Comprehensive interaction screening | Yeast-two-hybrid screening against ASD isoforms |

| STRING Database [6] | Known and predicted protein interactions with confidence scores | Interactome generation and hypothesis generation | Building preliminary networks for PTHS-related genes |

| SFARI Gene Database [5] | Curated ASD risk genes with evidence scores | Training and testing machine learning classifiers | Defining positive cases for random forest models |

| Stem-cell-derived iNs [1] | Neurogenin-2 induced excitatory neurons | Cell-type-specific interaction mapping | AP-MS for 13 high-confidence ASD risk genes |

| BrainSpan Atlas [5] | Spatiotemporal transcriptome data of human brain development | Contextualizing network findings in brain development | Integration with network propagation features |

| MAPPIT System [3] | Mammalian protein-protein interaction trap assay | Orthologous validation of interactions | Confirming Y2H findings in mammalian cellular environment |

| Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) [6] | R package for co-expression network construction | Identifying modules of co-expressed genes | Analyzing RNA-seq data from PTHS neural cells |

The validation of protein interaction networks in ASD research has transformed our understanding of the disorder's genetic architecture, moving from a focus on individual risk genes to interconnected functional modules. The integration of experimental network mapping in disease-relevant cell types with computational approaches has revealed unprecedented biological convergence, with implications for both biomarker development and therapeutic targeting.

Recent studies have successfully bridged basic network discoveries with clinical applications. For instance, network analysis combined with machine learning has identified ten key feature genes (SHANK3, NLRP3, SERAC1, TUBB2A, MGAT4C, TFAP2A, EVC, GABRE, TRAK1, and GPR161) with the highest importance scores for autism prediction [4]. Immune infiltration analysis further showed significant correlations between these genes and multiple immune cell types, demonstrating complex pleiotropic associations within the immune microenvironment [4]. Notably, MGAT4C emerged as a particularly robust biomarker with an AUC of 0.730 in differentiating ASD from controls [4].

The continuing evolution of network validation methodologies—including isoform-resolution interaction mapping, cell-type-specific proteomics, and multidimensional data integration—promises to further unravel the complexity of ASD. These approaches provide a framework for understanding how diverse genetic risk factors converge on disrupted biological pathways, ultimately advancing toward personalized interventions based on an individual's specific genetic and network profile.

Protein-Protein Interaction Networks as Biological Roadmaps

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks provide a crucial framework for understanding cellular machinery, where biological function emerges through the intricate web of physical interactions between a cell's molecular constituents [10] [11]. These networks represent proteins as nodes and their physical interactions as edges, creating a comprehensive map of cellular function that has become fundamental to modern biology [12]. In the context of complex neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), PPI networks offer unparalleled insights for parsing phenotypic heterogeneity and identifying convergent biological pathways [2] [13]. The fundamental premise is that proteins involved in the same biological process or complex often interact physically, and that the distortion of these protein interfaces may lead to the development of many diseases [10]. Despite exceptional experimental efforts to map out human interactomes, continued data incompleteness limits our ability to fully understand the molecular roots of human disease, creating a pressing need for sophisticated computational tools to identify biologically significant, yet unmapped interactions [11]. This guide objectively compares the performance of established and emerging methodologies for PPI network analysis, with particular emphasis on their application to ASD gene validation and research.

Methodological Landscape: Experimental and Computational Approaches

Experimental Foundations for Network Construction

The accuracy of any PPI network analysis fundamentally depends on the quality of the underlying interaction data. Several well-established experimental techniques form the bedrock of PPI network construction:

Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H): This in vivo method screens for binary protein interactions by leveraging the modular nature of transcription factors. A "bait" protein is fused to a DNA-binding domain, while "prey" proteins are fused to an activation domain. Interaction between bait and prey reconstitutes a functional transcription factor, activating reporter genes [10]. While powerful for large-scale screening, Y2H has limitations including false positives from nonspecific interactions and difficulties with membrane proteins or those requiring post-translational modifications not present in yeast [10].

Tandem Affinity Purification with Mass Spectrometry (TAP-MS): This method purifies native protein complexes under near-physiological conditions using a two-step purification tag. The TAP tag consists of two IgG binding domains of Staphylococcus protein A and a calmodulin binding peptide separated by a tobacco etch virus protease cleavage site [10]. After purification, complex components are identified via MS, providing information on higher-order interactions beyond binary pairs [10].

Mass Spectrometry (MS): Advanced MS techniques identify polypeptide sequences based on mass-to-charge ratios, with Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization (MALDI) solving the challenge of converting molecules to ions in the gas phase [10].

Table 1: Core Experimental Methods for PPI Data Generation

| Method | Principle | Scale | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) | Reconstitution of transcription factor via protein interaction | Binary interactions | In vivo detection, suitable for screening | False positives, challenges with membrane proteins |

| TAP-MS | Two-step affinity purification of protein complexes | Complex identification | Identifies native complexes, higher-order interactions | May miss transient interactions |

| Mass Spectrometry | Detection based on mass-to-charge ratios | Protein identification | High accuracy for identification | Requires protein purification |

Computational Prediction and Validation Methods

To address the inherent noise, incompleteness, and high false positive/negative rates in experimental PPI datasets [14] [15], numerous computational methods have been developed:

Traditional Link Prediction (Common Neighbors/TCP): Based on the triadic closure principle from social network analysis, these methods assume that proteins sharing multiple interaction partners are likely to interact themselves. The Common Neighbors algorithm quantifies this as the number of shared partners between two proteins [11]. However, recent evidence challenges this approach, showing that in PPI networks, the higher the Jaccard similarity between two proteins, the lower the chance they interact—a phenomenon termed the "TCP Paradox" [11].

L3 Principle (Paths of Length Three): This method offers a paradigm shift from traditional link prediction by proposing that proteins interact not if they are similar to each other, but if one is similar to the other's partners [11]. Mathematically implemented using degree-normalized paths of length three (L3), this approach significantly outperforms TCP-based methods. The L3 score is calculated as:

pXY = Σ(aXU × aUV × aVY) / √(kU × kV)whereaXUindicates interaction between proteins X and U, andkUis the degree of node U [11].Emerging Patterns (ClusterEPs): A supervised method that discovers contrast patterns distinguishing true complexes from random subgraphs in PPI networks [15]. These patterns combine multiple network properties (e.g., mean clustering coefficient, degree correlation variance) to create an integrative score measuring how likely a subgraph can form a complex [15].

Network Reconstruction and Edge Enrichment: These approaches address data quality issues by using protein similarity metrics (sequence similarity, local similarity indices like Common Neighbors and Jaccard Index, global similarity indices like Katz index and Random Walk with Restart) to either reconstruct the network or enrich it with additional edges [12].

Performance Comparison: Experimental Validation and Benchmarking

Computational Cross-Validation of Prediction Methods

Comprehensive computational cross-validation testing reveals significant performance differences between prediction methodologies. When randomly splitting networks into training and test sets (50% each), the L3 method demonstrates precision 2-3 times higher than Traditional Common Neighbors (TCP/CN) across all datasets [11]. This performance advantage holds for both binary interactomes and co-complex associations, with paths of length three (L3) showing optimal predictive power compared to longer paths [11].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of PPI Prediction Methods

| Method | Principle | Precision Advantage | Experimental Validation Rate | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L3 | Degree-normalized paths of length three | 2-3x higher than TCP/CN [11] | Significantly outperforms CN and PA in HT screens [11] | General-purpose prediction, especially for binary interactions |

| Common Neighbors (TCP) | Triadic closure principle | Baseline | Lower retest rates in experimental validation [11] | Social networks (less suitable for PPIs) |

| ClusterEPs | Emerging patterns contrasting complexes vs. random subgraphs | Higher precision and recall than SCI-BN, RM [15] | Better maximum matching ratio than 7 unsupervised methods [15] | Complex prediction from sparse subgraphs |

| PrePPI | Structural, sequence & biological evidence combination | Lower than L3 in experimental retests [11] | Several-fold lower retest rates than literature-curated interactions [11] | When structural information is available |

Experimental Validation in High-Throughput Screens

Independent high-throughput experimental validation provides the most rigorous assessment of prediction accuracy. When testing predictions against a systematic, binary human PPI map (HI-III) resulting from an independent screen over ~18,000 × 18,000 human protein pairs, L3 significantly outperformed both Common Neighbors and Preferential Attachment principles [11]. ClusterEPs has also been experimentally validated, demonstrating an ability to detect challenging complexes like the RNA polymerase I complex (14 proteins) and the RecQ helicase-Topo III complex (3 proteins), even when these represent not-well-separated subgraphs connecting to many external proteins [15].

Application to ASD Gene Research: Biological Insights and Validation

Network-Based Approaches to ASD Heterogeneity

PPI network analysis has proven particularly valuable in ASD research, where phenotypic heterogeneity represents a significant challenge. Recent studies have demonstrated how rare protein-disrupting risk variants implicated in ASDs converge in specific interaction networks, with proteomics in induced human neurons identifying more than 1,000 interactions, 90% of which were not previously reported [2]. This emphasizes the critical importance of cell-type- and isoform-specific protein interactions in ASD pathophysiology [2].

Multi-step analyses leveraging PPI networks have successfully identified gene sets with different loads of protein-altering variants between ASD subgroups divided by intelligence quotient (IQ) [13]. These gene sets cluster into modules involved in ion cell communication, neurocognition, gastrointestinal function, and immune system—with these modules showing high expression in specific brain structures across development [13]. Through spatio-temporal brain co-expression and physical interaction analysis, these modules can be extended to identify genes with over-represented autism susceptibility genes according to the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative database [13].

ASD PPI Network Analysis Workflow: This diagram illustrates the multi-step approach for identifying functionally relevant protein interaction modules in autism spectrum disorder, integrating genetic, clinical, and network data [13].

Experimental Protocols for ASD-Focused Network Validation

For researchers investigating ASD mechanisms through PPI networks, the following protocols provide robust frameworks for validation:

Protocol 1: Module Identification in ASD Subgroups

- Participant Recruitment: Recruit ASD participants (e.g., 3-12 years) with comprehensive phenotypic characterization, including standardized IQ measures [13].

- Subgroup Classification: Divide cohorts based on relevant phenotypic measures (e.g., higher vs. lower IQ using appropriate cutoff, such as >80 vs. ≤80) [13].

- Genetic Analysis: Perform gene set variant enrichment analysis to identify gene sets with significantly different incidence of protein-altering variants between subgroups (FDR q < 0.05) [13].

- Module Clustering: Hierarchically cluster significant gene sets into modules representing convergent biological processes [13].

- Functional Annotation: Characterize modules with labels representative of their biological processes (e.g., ion cell communication, neurocognition) [13].

Protocol 2: Network Extension and Validation

- Brain Expression Profiling: Assess module expression profiles across brain structures and developmental stages using the BrainSpan Atlas of the Developing Human Brain [13].

- Network Extension: Extend modules by selecting genes that are spatio-temporally co-expressed in the developing brain and physically interacting with module genes according to databases like bioGRID [13].

- ASD Gene Enrichment: Investigate incidence of autism susceptibility genes within original and extended modules using SFARI database [13].

- Experimental Validation: Test key predicted interactions using orthogonal methods (Y2H, TAP-MS) or functional assays relevant to ASD pathophysiology.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PPI Network Studies in ASD

| Resource/Reagent | Type | Function in PPI Research | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| BrainSpan Atlas | Database | Provides spatio-temporal gene expression patterns during human brain development for network validation [13] | BrainSpan Atlas of the Developing Human Brain |

| bioGRID | Database | Repository of physical and genetic interactions for network extension and validation [13] | Biological General Repository for Interaction Datasets |

| SFARI Gene | Database | Curated database of autism-associated genes for enrichment analysis of network modules [13] | Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative |

| TAP Tag System | Experimental reagent | Two-step affinity purification tag for isolating native protein complexes under near-physiological conditions [10] | Commercial vectors (e.g., pBS1479) |

| Y2H Systems | Experimental system | High-throughput screening of binary protein interactions in vivo [10] | Commercial systems (e.g., GAL4/LexA-based) |

| DIP | Database | Database of Interacting Proteins providing curated PPI data for network construction [14] | Database of Interacting Proteins |

| STRING | Database | Protein-protein interaction database with functional enrichment capabilities [16] | Search Tool for Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins |

| Cytoscape | Software platform | Network visualization and analysis for interpreting complex interaction data [16] | Cytoscape Consortium |

Protein-protein interaction networks serve as indispensable biological roadmaps for navigating the complexity of autism spectrum disorder and other neurodevelopmental conditions. The performance comparisons presented in this guide demonstrate that while traditional methods like Common Neighbors have limitations, emerging approaches such as L3-based prediction and ClusterEPs offer significantly improved accuracy for identifying biologically relevant interactions. For ASD researchers, integrating multiple computational approaches with experimental validation through standardized protocols provides the most robust framework for identifying functionally convergent pathways underlying disease heterogeneity. As interactome coverage continues to improve, these network-based roadmaps will play an increasingly central role in translating genetic findings into mechanistic understanding and therapeutic opportunities.

For researchers investigating the complex protein networks underlying autism spectrum disorder (ASD), selecting the right database is crucial. The SFARI Gene database provides an ASD-focused gene repository, the IMEx Consortium offers a deeply curated set of molecular interaction data, and the STRING database delivers a comprehensive predictive protein network. This guide provides an objective comparison to help you choose the right tool for your research stage.

The table below summarizes the core attributes, strengths, and limitations of each resource, providing a snapshot for initial comparison.

| Feature | SFARI Gene | IMEx Consortium | STRING |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | ASD-specific risk genes & evidence [17] | Curated, non-redundant physical molecular interactions [18] | Comprehensive protein-protein associations (physical & functional) [19] [20] |

| Key Data Source | Manually curated peer-reviewed literature [17] | Expert curation from direct submissions & publications [18] [21] | Experimental data, computational predictions, co-expression, & prior knowledge [19] [20] |

| ASD Relevance | Direct; core resource for autism genetics [22] [17] | Indirect; provides underlying physical interaction data [18] | Indirect; allows analysis of ASD gene lists in broader networks [19] |

| Unique Strength | Integrated gene scoring (e.g., EAGLE) for ASD association [17] | High-quality, standardized experimental data with binding details [21] | Massive scale, integration of evidence, & predictive power [23] [20] |

| Main Limitation | Scope is inherently limited to ASD context [17] | Limited to experimentally verified interactions; smaller scale [18] | Includes predicted interactions; requires validation for specific hypotheses [23] |

Experimental Data and Validation Protocols

The credibility of a database hinges on its data curation and validation processes. Here we detail the methodologies behind each resource.

SFARI Gene's Multi-Layered Curation

SFARI Gene employs a rigorous, multi-step manual curation process to ensure the accuracy of its ASD-associated genes and variants [17].

- Curation Workflow: Data is manually extracted from peer-reviewed literature, followed by significant standardization and data cleaning before being exported to the database [17].

- Gene Scoring: It incorporates frameworks like the Evaluation of Autism Gene Link Evidence (EAGLE), which uses a clinical-genetic validity framework to assess the strength of evidence specifically linking a gene to core ASD, distinct from broader neurodevelopmental disorders [17].

IMEx Consortium's Standardized Curation

The IMEx Consortium provides high-quality molecular interaction data through a network of major public databases adhering to consistent, expert-driven standards [18] [21].

- Standardized Formats: Data is curated into standard formats like PSI-MI XML or MITAB, enabling loss-free data transfer and integration across resources [21].

- Contextual Detail: Curation captures fine-grained experimental details, including binding sites, effects of point mutations, cell lines, and treatments with agonists/antagonists [18].

STRING's Evidence-Based Scoring

STRING generates comprehensive networks by integrating multiple evidence channels and assigning a confidence score to each interaction [20].

- Evidence Integration: Associations are drawn from high-throughput experiments, conserved genomic context, automated text-mining, and co-expression [19] [20].

- Confidence Scoring: Each interaction receives a probabilistic confidence score that integrates the evidence from different channels, allowing users to filter networks by reliability [20].

This table lists key reagents and computational tools referenced in studies of protein networks in ASD, which are instrumental for experimental validation.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Shank3Δ4–22 & Cntnap2−/− mice [24] | Animal Model | Genetically engineered mouse models to study shared molecular pathways in ASD. |

| SH-SY5Y cells with SHANK3 deletion [24] | Cell Line | A human-derived cell line used to investigate autophagy and signaling defects in vitro. |

| 7-NI (Neuronal NOS Inhibitor) [24] | Pharmacological Inhibitor | Used to inhibit neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) and study its role in normalizing autophagy. |

| LC3-II / p62 Antibodies [24] | Antibody | Markers for monitoring autophagosome accumulation and autophagic flux via western blot or immunofluorescence. |

| HAT (Hare And Tortoise) Computational Tool [25] | Software Algorithm | Rapidly detects de novo variants from sequencing data, accelerating genomic analysis. |

| CNPI (Copy Number Private Investigator) Tool [26] | Software Algorithm | Quickly detects copy number variants (CNVs), genotypes, and sex chromosomes from whole genome data. |

Research Workflow and Database Synergy

A typical research pipeline for validating ASD protein networks often involves using all three databases in a complementary manner, as illustrated below. A researcher might start with a list of candidate genes from SFARI, retrieve their high-confidence physical interactions from IMEx, and then place these into a broader functional context using STRING to generate new biological hypotheses.

Key Takeaways for Researchers

- For ASD-Focused Projects: Begin your investigation with SFARI Gene to establish a vetted list of candidate genes and their associated evidence scores [17].

- For Detailed Mechanistic Studies: Use the IMEx Consortium when you require high-quality, experimentally verified physical interactions to build a reliable core network, for instance, to plan a yeast-two-hybrid experiment [18] [21].

- For Systems-Level Exploration and Hypothesis Generation: Use STRING to place your ASD gene list into a wider functional context, uncovering potential novel pathways or compensatory mechanisms [19] [20].

- For a Robust Workflow: Combine all three. Use SFARI for discovery, IMEx for high-quality physical interactions, and STRING for functional context and hypothesis generation, creating a powerful, synergistic research pipeline.

In the analysis of Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks for complex disorders like Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), network topology metrics are indispensable for pinpointing biologically significant genes. These metrics transform extensive gene lists into prioritized candidates by quantifying their structural importance within the interactome. Betweenness centrality and hub identification are two pivotal approaches for this task [27] [28]. Betweenness centrality identifies nodes that act as critical bridges, facilitating communication across different parts of the network. In contrast, hub identification, often using metrics like Degree or Maximal Clique Centrality (MCC), spots highly connected nodes that may function as central organizers [28] [29]. This guide objectively compares their performance, experimental protocols, and applications in ASD research, providing a framework for selecting the appropriate metric based on research goals.

Metric Comparison: Betweenness Centrality vs. Hub Identification

The table below summarizes the core definitions, strengths, and applications of these key metrics.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Network Topology Metrics

| Feature | Betweenness Centrality | Hub Identification (e.g., Degree, MCC) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | Measures how often a node lies on the shortest path between all other node pairs [27]. | Measures the number of direct connections a node has (Degree), or the number of maximal cliques it belongs to (MCC) [28] [29]. |

| Primary Application | Identifying bottleneck proteins that connect functional modules [27]. | Identifying highly connected proteins that may form the core of functional complexes [28]. |

| Typical Workflow | Calculate centrality, then rank genes by score [27]. | Calculate multiple algorithms, then find consensus across them [28] [29]. |

| Key Strength | Uncovers critical, non-obvious connectors that are not necessarily highly connected [27]. | Directly targets proteins with many partners, which are often essential [28]. |

| ASD Research Application | Prioritized novel candidate genes (e.g., CDC5L, RYBP) from noisy CNV data [27]. | Identified immune-related hub genes (e.g., ADIPOR1, LGALS3) from blood-derived transcriptomic data [28]. |

Experimental Protocols for Metric Application

Protocol for Gene Prioritization Using Betweenness Centrality

A systems biology study provides a clear workflow for using betweenness centrality to prioritize ASD risk genes from copy number variants (CNVs) of unknown significance [27].

- Network Construction: Generate a comprehensive PPI network using a seed list of known ASD-associated genes from the SFARI database. Query databases like IMEx to gather both the seed genes and their direct interaction partners to build the network [27].

- Topological Analysis: Calculate the betweenness centrality for every node in the network using graph analysis tools. The betweenness centrality for a node is calculated as the fraction of all shortest paths in the network that pass through that node [27].

- Gene Prioritization: Rank all genes based on their betweenness centrality score. Genes with higher scores are considered top candidates for further investigation [27].

- Functional Validation: Perform pathway enrichment analysis (e.g., using over-representation analysis) on the prioritized gene list to identify biologically relevant pathways, such as ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis or cannabinoid signaling, which may be perturbed in ASD [27].

Protocol for Hub Gene Identification via Multi-Algorithm Consensus

Another established method for hub gene identification employs a consensus across multiple topology-based algorithms, as demonstrated in a study searching for ASD biomarkers in peripheral blood [28].

- Differential Gene Analysis: Identify Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) by comparing transcriptomic data (e.g., from RNA sequencing) between ASD and control samples. Combine results with public datasets like GEO's GSE77103 to create a robust gene list [28].

- PPI Network Construction: Input the DEGs into the STRING database to build a PPI network, focusing on experimentally validated interactions [28].

- Hub Gene Screening: Import the PPI network into Cytoscape. Use the CytoHubba plugin to calculate hub scores using several algorithms, such as:

- Consensus Identification: Select genes that consistently rank highly across all applied algorithms as the final set of hub genes for downstream analysis [28].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting and applying these topology metrics in ASD gene research, from data preparation to final validation.

Topology Metric Selection Workflow

Successful application of these metrics relies on specific, publicly available databases and software tools.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Network Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Analysis | Relevance to ASD Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| STRING [19] | Database | Provides known and predicted PPIs for network construction. | Foundation for building the human interactome context. |

| Cytoscape [28] [29] | Software Platform | Visualizes and analyzes molecular interaction networks. | Essential for network visualization and topology calculation via plugins. |

| CytoHubba [28] [29] | Software Plugin | Calculates multiple hub identification algorithms (Degree, MCC, etc.) within Cytoscape. | Directly used to screen for hub genes from PPI networks. |

| SFARI Gene [27] | Database | Curates a comprehensive list of ASD-associated genes. | Provides high-confidence seed genes for initial network building. |

| GeneCards [29] | Database | Integulates genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data for genes. | Used to compile and validate lists of ASD-related genes. |

| IMEx Databases [27] | Database Consortium | Source of experimentally verified physical PPIs. | Used to build high-quality, evidence-based PPI networks. |

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) presents a complex genetic architecture with hundreds of identified risk genes, creating a critical need for experimental systems capable of validating their functional convergence and biological mechanisms. While genomic and transcriptomic studies have identified numerous candidate genes, these approaches alone cannot reveal the protein-level interactions and functional impairments that underlie ASD pathophysiology. The emergence of human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neuronal models has revolutionized this validation process by providing disease-relevant human cells that capture patient-specific genetic backgrounds. These models enable researchers to move beyond association studies to functional validation of molecular pathways in a human neuronal context, addressing a critical gap between genetic discovery and mechanistic understanding.

Protein interaction networks constructed in non-neural cell lines or heterogeneous tissues have proven inadequate for capturing the neuronal-specific interactions essential for understanding neurodevelopmental disorders. Recent studies emphasize that approximately 90% of protein-protein interactions (PPIs) identified in human neuronal contexts were previously unreported, highlighting the profound importance of cell-type-specific proteomic studies for elucidating authentic disease mechanisms [1]. This comparison guide examines the leading iPSC-derived neuronal platforms for experimental validation of ASD gene networks, providing researchers with objective performance comparisons and methodological frameworks to advance their investigative workflows.

Comparative Analysis of iPSC-Derived Neuronal Platforms for ASD Research

The selection of an appropriate neuronal differentiation platform fundamentally shapes experimental outcomes in ASD research. The table below compares the three primary approaches used in recent studies, highlighting their distinctive advantages and limitations for protein interaction validation and functional characterization.

Table 1: Platform Comparison for iPSC-Derived Neuronal Models in ASD Research

| Differentiation Platform | Differentiation Time | Neuronal Purity | Key Functional Assays | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurogenin-2 (NGN2) Induction | 2-4 weeks | High (>90% glutamatergic neurons) | IP-MS, LC-MS/MS, calcium imaging, synaptic physiology | Rapid protein interactome mapping, isogenic studies, high-throughput screening |

| Neural Progenitor Cell (NPC) Differentiation | 8-12 weeks | Mixed cortical populations | miRNA profiling, calcium transients, chemogenetic network manipulation | Developmental studies, network formation, subtype-specific interactions |

| 3D Cortical Organoids | 2-6 months | Complex multicellular diversity | Single-cell RNA-seq, electrophysiology, structural imaging | Cellular microenvironment studies, cell-non-autonomous effects, spatial organization |

Performance Metrics Across Platforms

Each platform demonstrates distinctive strengths for specific research applications. The NGN2-induction system offers exceptional experimental uniformity with reported neuronal purity exceeding 90%, making it particularly valuable for proteomic studies requiring standardized cellular backgrounds [1]. This platform enables rapid generation of excitatory cortical-like neurons, significantly reducing differentiation time compared to traditional methods. However, this accelerated maturation comes at the cost of developmental complexity, as the bypassed neurodevelopmental stages may obscure critical disease-relevant phenotypes.

In contrast, NPC-based differentiation preserves more physiological developmental progression, making it suitable for studying the temporal dynamics of protein network establishment during neurodevelopment [30]. Studies utilizing this approach have successfully identified functional alterations in idiopathic ASD models, including reduced calcium transients (29.8% of control) and differentially expressed miRNAs regulating neurodevelopmental pathways [30]. The extended differentiation timeline (8-12 weeks) enables examination of network maturation processes but introduces greater experimental variability.

Cortical organoid systems provide the most physiologically representative model of the developing human brain, incorporating diverse cell types and emergent tissue architecture. While not extensively covered in the available search results for protein interaction studies, their increasing application in ASD research offers unique insights into how risk genes function within complex multicellular environments.

Methodological Framework for Protein Interaction Validation

Proteomic Mapping in Human Neurons

The validation of ASD protein interaction networks requires specialized methodologies optimized for human neuronal contexts. The following experimental workflow has been successfully implemented in multiple studies for mapping neuron-specific interactomes:

Table 2: Core Methodologies for Protein Interaction Mapping in iPSC-Derived Neurons

| Method | Experimental Principle | Key Outputs | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoprecipitation-Mass Spectrometry (IP-MS) | Antibody-mediated isolation of protein complexes with LC-MS/MS identification | Binary protein interactions, complex composition | Requires high-quality IP-competent antibodies; assesses steady-state interactions |

| Proximity Labeling (BioID2) | Enzyme-mediated biotinylation of proximal proteins with streptavidin capture | Spatial proximities, microenvironment mapping | Identifies transient interactions; may include non-physiological neighbors |

| Co-Expression Analysis | Correlation of mRNA expression across neuronal differentiations | Functional relationships, putative interactions | Indirect evidence; requires proteomic validation |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Editing | Gene knockout or mutation introduction in isogenic backgrounds | Interaction dependency, patient variant impact | Enables causal inference; requires careful control for compensatory mechanisms |

The IP-MS approach applied to NGN2-induced neurons expressing ASD risk genes has identified between 3-604 specific interactors per index protein, with limited overlap between different risk genes, suggesting diverse mechanistic pathways [1]. This method provides direct evidence of physical associations but may miss transient interactions. The orthogonal BioID2 approach, which utilizes a promiscuous biotin ligase to tag proximal proteins, has successfully identified convergent pathways including mitochondrial processes, Wnt signaling, and MAPK signaling despite limited overlap in specific interactors [31].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for protein network validation in iPSC-derived neuronal models of ASD

Functional Validation of Neuronal Impairments

Beyond identifying physical interactions, validating the functional consequences of disrupted networks is essential. Standardized assays for neuronal activity assessment include:

Calcium Imaging: Utilizing genetically-encoded indicators (e.g., GCaMP6s) to monitor spontaneous intracellular calcium transients, which faithfully correlate with neuronal activity. Studies of idiopathic ASD-iPSC neurons have revealed significantly reduced calcium transients (29.8% ± 0.7% of controls), indicating impaired neuronal activity [30].

Synaptic Characterization: Electrophysiological measurements of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSC) and network activity through multielectrode arrays. ASD models consistently show reduced sEPSC frequency and diminished network synchronization.

Chemogenetic Network Manipulation: Implementation of designer receptors exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADDs) in co-culture systems to probe connectivity deficits. This approach has demonstrated impaired synaptic neurotransmission and connectivity in ASD-derived neurons [30].

Metabolic and Mitochondrial Assessment: Functional evaluation of mitochondrial respiration and glycolytic capacity through Seahorse analysis, particularly relevant given the association between non-syndromic ASD risk genes and mitochondrial dysfunction [31].

Signaling Pathway Convergence in ASD Risk Networks

Protein interaction mapping in human neurons has revealed unexpected convergence of ASD risk genes onto specific signaling pathways and biological processes. The diagram below illustrates the key pathways identified through proteomic studies:

Diagram 2: Signaling pathway convergence and functional consequences of ASD risk genes

Notably, these convergent pathways manifest in human neurons but were largely absent from previous interaction studies in non-neural systems, highlighting the importance of cell-type-specific validation. The insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins (IGF2BP1-3), which form an m6A-reader complex, emerge as highly interconnected nodes, interacting with at least 5 index ASD proteins and potentially serving as major mediators of convergent biological pathways [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of iPSC-based validation studies requires specific reagents and tools optimized for neuronal proteomics and functional assessment. The following table details essential solutions with their applications in ASD research:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for iPSC-Derived Neuronal Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reprogramming Factors | OSKM (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, MYC) or OSML (OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28) | iPSC generation from somatic cells | Non-integrating episomal vectors preferred for clinical translation |

| Neuronal Differentiation | NGN2 lentivirus, SMAD inhibitors, retinoids | Directed differentiation to excitatory neurons | NGN2 systems provide rapid, synchronized differentiation |

| Proteomic Tools | IP-competent antibodies, BioID2 constructs, streptavidin beads, mass spectrometry | Protein interaction mapping | ∼40% overlap between interactions in iPSC-neurons and postmortem cortex |

| Cell Type Markers | PAX6 (NPCs), MAP2 (mature neurons), SYP (synapses), vGLUT1 (glutamatergic) | Identity and purity validation | Flow cytometry and immunocytochemistry essential for QC |

| Functional Assays | GCaMP6s (calcium imaging), DREADDs (chemogenetics), multielectrode arrays | Neuronal activity assessment | Calcium transients correlate with neuronal activity frequency |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 systems, homology-directed repair templates | Isogenic control generation, variant validation | Enables study of specific mutations in uniform genetic background |

Quality control throughout the differentiation process is critical, with recommended assessment of genomic integrity, pluripotency markers (OCT4, NANOG), trilineage potential, and neuronal purity (MAP2, Tuj1) exceeding 90% for proteomic studies [32]. Additionally, neuronal preparations should demonstrate appropriate electrophysiological properties and spontaneous activity to ensure functional maturation.

The experimental validation of ASD risk genes in human iPSC-derived neuronal models has fundamentally advanced our understanding of disease mechanisms by revealing authentic, cell-type-specific protein interactions. The comparative data presented in this guide demonstrates that NGN2-induced neurons provide optimal platforms for proteomic mapping studies requiring standardization and scalability, while NPC-differentiated models offer advantages for developmental investigations and functional network characterization.

The consistent identification of previously unrecognized protein interactions (∼90% novel) across multiple studies underscores the critical importance of neuronal context for elucidating authentic ASD biology [1]. These cell-type-specific interaction networks successfully nominate novel candidate genes, reveal convergent biological pathways, and provide functional insights into the molecular consequences of patient-derived variants. Furthermore, the association between specific PPI networks and clinical behavioral score severity suggests potential for stratifying ASD into biologically meaningful subtypes [31].

As the field progresses, integrating neuronal proteomic data with transcriptomic, epigenetic, and clinical information will enable more comprehensive models of ASD pathogenesis. The experimental frameworks and methodological considerations outlined in this guide provide researchers with evidence-based strategies for selecting appropriate validation platforms and implementing robust protocols to advance our understanding of ASD mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities.

From Data to Discovery: Computational Frameworks and Analytical Pipelines

Constructing Cell-Type-Specific Interactomes in Human Neurons

The quest to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying complex neurodevelopmental disorders like autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has revealed a landscape of extensive genetic heterogeneity. This review examines how the construction of cell-type-specific protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks in human neurons is overcoming the limitations of traditional omics approaches and non-neural models. By focusing on the pioneering methodology of Pintacuda et al., we demonstrate how interactomes derived from human induced excitatory neurons (iNs) provide a high-resolution, functionally relevant map of biological convergence. The data reveals that approximately 90% of the over 1,000 identified interactions were novel, underscoring the critical importance of cellular context. These networks successfully nominate new candidate risk genes, uncover critical hub proteins like the IGF2BP complex, and illuminate the functional impact of isoform-specific interactions, offering a powerful framework for translating genetic findings into therapeutic insights for ASD [1] [33].

Neuropsychiatric disease research operates on the premise that understanding genetic risk factors will reveal the mechanistic underpinnings of disorders like Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Large-scale genetic studies have identified hundreds of ASD risk genes, implicating pathways related to synaptic signaling, Wnt signaling, mTOR pathways, and chromatin remodeling [1]. Single-cell transcriptomics has further refined this understanding, showing that risk gene expression is concentrated in excitatory neurons and peaks during fetal brain development [1].

However, a significant gap exists between gene identification and functional understanding. The functional convergence of disparate risk genes—how they interact within specific cellular environments to drive common pathophysiological outcomes—remains poorly characterized. Traditional PPI studies, often conducted in non-neural cell lines, have proven insufficient for capturing the nuanced biology of the human neuron [1]. This review details how the construction of cell-type-specific interactomes in human induced neurons is bridging this gap, providing an unprecedented resource for validating genetic findings and uncovering novel therapeutic targets in ASD research.

Methodological Framework: Building Neuron-Specific Interactomes

The construction of a biologically relevant interactome requires a carefully controlled experimental pipeline from cell differentiation to data validation. The protocol established by Pintacuda et al. serves as a benchmark in the field [1] [33].

Experimental Workflow and Key Reagents

The following diagram outlines the core workflow for constructing a cell-type-specific interactome:

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential materials and reagents used in these experiments, as derived from the featured studies.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Neuronal Interactome Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function in the Protocol | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| Induced Excitatory Neurons (iNs) | Biologically relevant cellular substrate for PPI mapping. | Derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) via neurogenin-2 (NGN2) induction; provides a homogeneous population of excitatory neurons [1]. |

| IP-competent Antibodies | Immunoprecipitation of index ASD risk proteins from neuronal lysates. | High-specificity antibodies are required for each of the index proteins (e.g., against DYRK1A, PTEN, ANK2) to pull down protein complexes [1] [33]. |

| Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | Identification and quantification of co-immunoprecipitated proteins. | Enables high-throughput, sensitive detection of protein interactors; the primary tool for generating the raw interaction data [1] [33]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Validation of interactions via gene editing (e.g., isoform knockout). | Used to generate specific genetic perturbations, such as the knockout of the giant exon 37 in ANK2, to test the functional necessity of specific isoforms for interactions [1]. |

| STRING Database & Cytoscape | Computational construction and visualization of the PPI network. | STRING is used to build initial networks; Cytoscape with its cytoHubba plugin is used for advanced network analysis and hub gene identification [4] [34]. |

Key Findings and Comparative Data

The application of this methodology has yielded several groundbreaking insights, moving beyond what was possible with genetic or transcriptomic data alone.

Novel Interactions and Network Convergence

The neuron-specific interactome revealed a startling degree of novelty. When 13 high-confidence ASD risk genes were used as "index" proteins, the resulting network contained over 1,000 interactions, 90% of which were previously unreported [1]. This highlights the profound limitation of previous interactomes built in non-neural systems. Furthermore, while most interactors were specific to a single index protein, key points of convergence were identified. The IGF2BP1-3 complex (a trio of mRNA-binding proteins) emerged as a major hub, interacting with at least five different index proteins, suggesting a potential role in coordinating a common regulatory circuit for multiple ASD risk genes [1] [33].

Illuminating Isoform-Specific Biology

The interactome proved powerful in deciphering the functional consequences of specific protein isoforms. This was exemplified by the study of ANK2, which encodes a massive neuronal protein. A neuron-specific isoform of ANK2 that retains a "giant" exon (exon 37) was found to be responsible for interactions with numerous synaptic proteins. Crucially, this specific exon is a hotspot for patient mutations. CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of this giant exon abolished these specific interactions, directly linking a genetic lesion to the disruption of a defined protein interaction module in neurons [1].

Cross-Validation with Other Omics Data

The biological relevance of the neuronal PPI network is strengthened by its alignment with other data modalities. The identified interactions show significant overlap with genes differentially expressed in Layer II/III cortical glutamatergic neurons from ASD post-mortem brains [1]. This complements prior transcriptomic studies that found ASD risk genes enriched in these same neuronal populations, which are critical for inter-hemispheric and cortical-cortical connectivity [1]. This convergence across proteomic and transcriptomic data reinforces the central role of these cells in ASD pathophysiology.

Pathway Integration and Therapeutic Discovery

Cell-type-specific interactomes do not exist in isolation; they interface with broader signaling pathways to influence cellular function and offer therapeutic inroads.

Integration with Neurodevelopmental Pathways

The CHD8-Notch pathway interaction study provides a compelling example of how PPI data can be integrated with pathway analysis. By analyzing differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from CHD8-deficient samples, researchers identified 298 genes that intersected with the Notch signaling pathway. Subsequent PPI network construction and hub gene analysis from this intersection revealed a functional module where a chromatin remodeler (CHD8) directly influences a key neurodevelopmental pathway (Notch), providing a mechanistic hypothesis for how CHD8 mutations contribute to ASD [34]. The relationship between such pathways and the neuronal interactome can be visualized as follows:

Translation to Therapeutic Targets

The ultimate validation of a network is its utility in identifying new treatment strategies. The hub genes identified in neuronal interactomes and related pathway analyses serve as prime candidates for therapeutic development. For instance, random forest analysis of transcriptomic data integrated with PPI networks has identified key feature genes like SHANK3, NLRP3, and MGAT4C for ASD prediction, with MGAT4C showing particular promise as a biomarker (AUC = 0.730) [4]. Furthermore, the construction of drug-gene interaction networks using databases like DGIdb can directly map these hub genes onto known or novel pharmacological compounds, creating a shortlist for experimental testing and drug repurposing efforts [4] [34].

Table 2: Key Genes Emerged from Network-Based Studies in ASD

| Gene | Role/Function | Validation Method | Key Finding / Therapeutic Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| IGF2BP1-3 | mRNA-binding complex, m6A-reader | Neuronal PPI Network | Acted as a convergent hub, interacting with ≥5 ASD index proteins; suggests a novel regulatory complex for therapeutic targeting [1]. |

| ANK2 (Giant Isoform) | Neuronal scaffolding protein | Isoform-Specific CRISPR KO | Interactions with synaptic proteins depended on exon 37; links patient mutations in exon to specific network disruption [1]. |

| MGAT4C | Glycosylation enzyme | Random Forest & ROC Analysis | Demonstrated strong discriminatory power as a biomarker (AUC=0.730) [4]. |

| CHD8-Notch Intersection | Chromatin remodeling & signaling | Pathway Enrichment & PPI | 298 shared DEGs linked CHD8 deficiency to Notch signaling; reveals a synergistic pathogenic module [34]. |

The construction of cell-type-specific interactomes in human neurons represents a paradigm shift in the study of neurodevelopmental disorders. By moving beyond generic cellular models and embracing the complexity of the native neuronal proteome, this approach has uncovered a vast and previously hidden landscape of biological convergence among ASD risk genes. The findings—from the discovery of novel interactions and critical hubs like the IGF2BP complex to the functional deconstruction of isoform-specific networks—provide a more coherent, mechanistic framework for understanding ASD pathogenesis. This network-based, cell-type-specific paradigm not only validates and refines genetic discoveries but also creates a rich, targetable map for future diagnostic and therapeutic development, ultimately bridging the long-standing gap between genetics and functional pathology in the human brain.

Integrating Machine Learning with Network Propagation

This guide compares the performance of a network propagation-based classifier against established machine learning methods for prioritizing autism spectrum disorder (ASD) risk genes. The evaluation, framed within the critical need for validating protein interaction networks in complex neurodevelopmental disorders, demonstrates that integrating network-propagation features with a random forest classifier achieves state-of-the-art predictive accuracy, outperforming previous benchmarks.

Performance Comparison

The network propagation approach was systematically evaluated against forecASD, a recognized state-of-the-art predictor, and a negative control. Performance was assessed using the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC), a standard metric for classification models.

Table 1: Classifier Performance Comparison

| Classifier Method | Key Features | AUROC | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Propagation + Random Forest [5] | Ten network-propagated gene scores from multi-omic data | 0.91 | Highest accuracy; integrates network context across diverse data layers |

| forecASD (State-of-the-Art) [5] | BrainSpan expression, STRING network data, literature-derived features | 0.87 | Consolidates prior evidence from multiple established sources |

| Negative Control (Degree-Preserving Random Network) [5] | Network propagation on a randomized network | 0.82 | Highlights quality of underlying biological data and gene sets |

The network propagation model achieved a mean AUROC of 0.87 and a mean Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC) of 0.89 in a 5-fold cross-validation, confirming the robustness of its results [5].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Network Propagation Classifier Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the two-stage computational pipeline for the network propagation classifier.

Detailed Protocol [5]:

- Input & Network: Ten lists of ASD-associated genes derived from genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data served as seed sets. The human protein-protein interaction (PPI) network from Signorini et al. (2021) was used as the scaffold.

- Network Propagation: For each seed gene list, a network propagation process was run. Each seed protein was assigned an initial value of

1/s(wheresis the size of the seed set). A damping parameterαof 0.8 was used to control the propagation distance. - Normalization: The resulting propagation scores for all genes in the network were normalized using eigenvector centrality to mitigate biases from node connectivity (degree).

- Model Training: The ten propagation scores for each gene formed its feature vector. A random forest model was trained using 206 SFARI "Category 1" (high-confidence) genes as positives and 206 randomly selected genes not in SFARI as negatives. The model used 100 trees with no maximum depth.

- Validation: Model performance was evaluated via 5-fold cross-validation. An optimal classification cutoff of 0.86 was established to maximize specificity and sensitivity.

Comparison Method: forecASD

Detailed Protocol [5]:

The forecASD classifier, used as the main benchmark, was implemented as described in its original publication. It integrates:

- Features: BrainSpan spatiotemporal brain expression data and network-based information from the STRING interaction database, combined with literature-derived features from earlier methods (DAWN, DAMAGES, Krishnan).

- Model: A random forest classifier is trained on these features to prioritize ASD-associated genes.

Validation via Independent Analysis

A separate 2025 study provides external validation for network-based approaches. Its methodology for identifying ASD-subgroup gene modules included extending modules by selecting genes that were both spatio-temporally co-expressed in the developing brain (per the BrainSpan Atlas) and physically interacting at the protein level (per the bioGRID database) [13]. This independent workflow confirms the biological relevance of integrating co-expression and physical interaction data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Resources for Network-Based ASD Gene Analysis

| Research Reagent / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research | Key Application in ASD Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| SFARI Gene Database [5] [35] | Data Repository | Provides expert-curated lists of ASD-associated genes with evidence scores. | Serves as a gold standard for training and validating predictive models (e.g., as positive training sets). |

| STRING / BioGRID [36] [13] | Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network | Scaffold of known and predicted physical protein interactions. | Used as the backbone for network propagation and analyzing connectivity among candidate genes. |

| BrainSpan Atlas [5] [13] | Transcriptomic Data | Atlas of spatiotemporal gene expression during human brain development. | Provides features for classifiers and validates the neurodevelopmental context of candidate genes. |

| SIGNOR [35] | Knowledge Base | Database of causal signaling relationships (e.g., A activates/inhibits B). | Enables the construction of directed, causal networks to move beyond correlation to mechanism. |

| Human ORFeome Collection [3] | Experimental Library | A physical collection of full-length human open reading frames (ORFs). | Essential for high-throughput experimental testing of protein interactions, such as in yeast-two-hybrid screens. |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC)-Derived Neurons [1] [37] | Cellular Model | Provides a physiologically relevant, human neuronal context. | Critical for building cell-type-specific protein interactomes, revealing interactions absent in non-neural lines. |

The integration of machine learning with network propagation represents a significant methodological advance for prioritizing ASD risk genes. The featured classifier demonstrates superior performance by directly incorporating the network context of diverse genomic data. For researchers and drug development professionals, this approach offers a more powerful framework for uncovering convergent biology and identifying novel therapeutic targets for complex neurodevelopmental disorders. Future directions will involve incorporating cell-type-specific interaction data [1] [37] and causal network information [35] to further enhance predictive power and biological insight.

The quest to understand the molecular etiology of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) exemplifies the need for sophisticated bioinformatics tools. While hundreds of risk genes have been identified, a critical challenge lies in discerning how these genes functionally converge into coherent biological pathways [1] [37]. Functional enrichment analysis, particularly through Gene Ontology (GO) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), provides the essential framework to translate lists of candidate genes into testable biological hypotheses [38]. This guide objectively compares these pivotal methodologies within the context of validating protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks in ASD research, providing researchers with a clear roadmap for selecting and applying the right tool.

Comparative Analysis of Enrichment Methodologies

GO and KEGG serve distinct but complementary purposes in functional annotation. GO classifies genes based on a structured vocabulary (ontology) across three domains: Biological Process (BP), Molecular Function (MF), and Cellular Component (CC) [39]. It answers questions about what a gene does and where it acts. In contrast, KEGG is pathway-centric, mapping genes onto specific metabolic, signaling, and cellular pathway diagrams to reveal how genes work together within systemic networks [39] [40].

A third critical method, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA), differs fundamentally by using a ranked list of all genes from an experiment (e.g., by expression fold change) rather than a pre-selected subset of differentially expressed genes (DEGs). This makes it powerful for detecting subtle, coordinated expression changes across entire gene sets where individual genes may not pass strict significance thresholds [39].

The table below summarizes the core operational differences:

Table 1: Core Feature Comparison of Enrichment Tools

| Feature | GO Enrichment | KEGG Enrichment | GSEA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Functional ontology & classification [39] | Pathway mapping & systems insights [39] | Coordinated expression shifts in gene sets [39] |

| Typical Input | List of DEGs [39] | List of DEGs [39] | Ranked list of all genes [39] |

| Key Output | Enriched GO terms (BP, MF, CC) [39] | Enriched pathway maps & diagrams [39] | Enrichment score (ES) & enrichment plots [39] |

| Statistical Test | Hypergeometric / Fisher's exact test [39] [41] | Hypergeometric / Fisher's exact test [39] | Kolmogorov-Smirnov-like running sum statistic [39] |

| Ideal Use Case | Detailed functional characterization of a gene set [39] | Exploring metabolic or signaling pathway interactions [39] | Data with subtle, system-wide changes lacking clear DEG cutoff [39] |

The choice between these methods directly impacts the biological insights gleaned from ASD PPI data. For instance, GO analysis of a PPI network might reveal enrichment in terms like "synaptic signaling" or "dendritic spine organization," providing granular functional context [31]. KEGG analysis of the same network could map the interacting proteins onto overarching pathways such as "mTOR signaling" or "Wnt signaling," which are recurrently implicated in ASD pathophysiology [1] [31].

Application in ASD Protein Interaction Network Validation

Recent seminal studies constructing neuron-specific PPI networks for ASD risk genes demonstrate the integral role of enrichment analysis in validation and interpretation. For example, Pintacuda et al. built a PPI network for 13 high-confidence ASD genes in human induced excitatory neurons [37]. A critical validation step involved demonstrating that the identified interacting proteins were functionally coherent. This was achieved by performing enrichment analysis, which showed the network was significantly enriched for genetic signals and transcriptional perturbations found in individuals with ASD, confirming its disease relevance beyond mere physical association [37].

Similarly, Murtaza et al. used proximity-labeling proteomics (BioID2) to map PPI networks for 41 ASD risk genes in primary mouse neurons [31]. Subsequent GO and pathway enrichment analysis of these networks revealed significant convergence on specific biological processes, including mitochondrial function, Wnt signaling, and MAPK signaling [31]. This convergence analysis is paramount, as it moves from a list of interactions to a mechanism-focused understanding, suggesting that disparate risk genes may disrupt common cellular modules.

Table 2: Enrichment Insights from Recent ASD PPI Studies

| Study (Year) | PPI Method | # of ASD Genes | Key Enriched Pathways/Functions (via GO/KEGG) | Biological Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pintacuda et al. (2023) [37] | IP-MS in human iNeurons | 13 | Not explicitly listed; network enriched for ASD genetic/transcriptional signals | Confirmed disease relevance of novel interactions. |

| Murtaza et al. (2022) [31] | BioID2 in primary neurons | 41 | Mitochondrial processes, Wnt signaling, MAPK signaling [31] | Identified convergent pathways linking diverse risk genes. |

| Corominas et al. (2014) [3] | Yeast-two-hybrid (Y2H) | 191 (isoforms) | Axon guidance, cell adhesion, cytoskeleton organization [42] | Isoform-specific networks connect genes from ASD CNVs. |

A crucial consideration is the choice of pathway database itself. Studies have shown that equivalent pathways from different databases (KEGG vs. Reactome vs. WikiPathways) can yield disparate enrichment results due to differences in curation and gene set composition [43]. This underscores the recommendation to use multiple databases or integrative meta-databases like ConsensusPathDB or MPath for more robust and consistent biological conclusions [43].

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Analyses

The following protocols detail how enrichment analysis is integrated into the validation pipeline for ASD PPI studies.

Protocol 1: Functional Enrichment of a Candidate PPI Network Objective: To determine if proteins within an experimentally derived PPI network are functionally related and relevant to ASD biology.

- Input Preparation: Compile a list of gene symbols for all high-confidence protein interactors identified (e.g., from IP-MS or BioID data).

- Background Definition: Define an appropriate background gene list. Best practice is to use all genes expressed in the experimental system (e.g., all genes detected in neuronal RNA-seq) rather than the whole genome, to avoid bias [41].

- Enrichment Analysis:

- GO Analysis: Use tools like clusterProfiler (R/Bioconductor) or ShinyGO (web server) [41] [38]. Perform over-representation analysis (ORA) using the hypergeometric test. Apply multiple-testing correction (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg FDR < 0.05) [41].

- KEGG/Pathway Analysis: Using the same tools, run ORA against the KEGG pathway database. For a more systems-level view, consider using SPIA (Signaling Pathway Impact Analysis) which incorporates pathway topology [43].

- Interpretation: Prioritize terms with high statistical significance (FDR) and high fold-enrichment [41]. Use visualization (bar plots, bubble charts, enrichment maps) to identify clusters of related functions. Validate findings by checking overlap with previously published ASD gene expression signatures or genetic data [37].