Validating Autism Candidate Genes: A Comprehensive Guide to the SFARI Gene Database for Researchers

This article provides a complete framework for validating autism spectrum disorder (ASD) candidate genes using the SFARI Gene database.

Validating Autism Candidate Genes: A Comprehensive Guide to the SFARI Gene Database for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a complete framework for validating autism spectrum disorder (ASD) candidate genes using the SFARI Gene database. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the database's foundational architecture, practical application of its scoring modules and bioinformatics tools, strategies to overcome common challenges like data inconsistencies, and methods for cross-database validation. By synthesizing the latest features and 2025 research findings, this guide empowers scientists to confidently prioritize genes and accelerate ASD research and therapeutic development.

Navigating the SFARI Gene Ecosystem: Understanding the Core Modules and Gene Scoring System

SFARI Gene is a dedicated, evolving database that serves as a comprehensive resource for the autism research community, centered on genes implicated in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) susceptibility [1] [2]. This curated web-based resource integrates various types of genetic data to facilitate hypothesis generation and accelerate autism research. The database is maintained through manual curation of peer-reviewed scientific literature by expert researchers, ensuring high-quality, evidence-based information [3] [2].

The database is organized into several interconnected modules that provide different perspectives on autism genetics:

- Human Gene Module: Serves as a comprehensive, up-to-date reference for all known human genes associated with ASD, featuring detailed annotations, relevant references from scholarly articles, and evidence linking genes to autism [4] [2].

- Gene Scoring System: Employs an innovative assessment system that assigns every gene a score reflecting the strength of evidence linking it to ASD development. The current simplified scoring categories include: S (syndromic), 1 (high confidence), 2 (strong candidate), and 3 (suggestive evidence) [1] [5].

- Copy Number Variant (CNV) Module: Catalogs recurrent single-gene and multi-gene deletions and duplications in the genome and describes their potential links to autism [1] [2].

- Animal Models Module: Contains information about genetically modified animals (primarily mice) that represent potential models of autism, including targeting constructs, background strains, and phenotypic features relevant to ASD [1] [2].

- Protein Interaction (PIN) Module: An interactive visual reference showcasing known protein interactions between gene products associated with ASD, though the scope of this module has been recently scaled back [3] [5].

Experimental Validation of SFARI Gene as a Research Resource

Performance Assessment in Variant Detection Studies

SFARI Gene's utility as a reference database has been empirically validated in independent research. A 2023 study published in Scientific Reports evaluated the effectiveness of three bioinformatics tools for detecting ASD candidate variants from whole-exome sequencing (WES) data and used SFARI Gene as the benchmark for assessing performance [6].

Table 1: Tool Performance Metrics Using SFARI Gene as Gold Standard

| Tool Combination | Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% Confidence Interval | Diagnostic Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| InterVar ∩ Psi-Variant | 0.274 | 7.09 | 3.92–12.22 | Not specified |

| InterVar ∪ Psi-Variant | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 20.5% |

| InterVar & TAPES Overlap | 64.1% concordance | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| TAPES & Psi-Variant Overlap | 23.1% concordance | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

The study analyzed WES data from 220 ASD family trios and demonstrated that SFARI Gene provides a robust framework for evaluating variant detection methodologies [6]. Researchers found that the intersection of InterVar (an ACMG/AMP criteria-based tool) and Psi-Variant (a likely gene-disrupting variant detection tool) was particularly effective at identifying variants in known ASD genes, achieving a positive predictive value of 0.274 and an odds ratio of 7.09 [6]. Furthermore, the union of these tools identified candidate ASD variants in 20.5% of probands, highlighting the substantial diagnostic yield possible when using SFARI Gene as a reference standard [6].

Technical Infrastructure for Data Access and Analysis

The Genotypes and Phenotypes in Families (GPF) platform serves as the computational infrastructure for disseminating SFARI genetic data [7]. This open-source platform manages genotypes and phenotypes derived from family collections and supports interactive exploration of genetic variants, enrichment analysis for de novo mutations, and genotype-phenotype association tools [7].

Table 2: GPF-SFARI Platform Capabilities and Supported Data Types

| Feature | Capability | Supported Data Types |

|---|---|---|

| Family Structures | Nuclear families, multigenerational families, single individuals | Trios, extended pedigrees, case-control formats |

| Variant Types | Single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), indels, copy-number variants (CNVs) | Data from WES, WGS, array hybridization |

| Inheritance Patterns | Mendelian, de novo, omission | Parent-child transmission patterns |

| Analysis Tools | Gene browser, family variants view, phenotype/genotype association | Variant frequency, impact prediction, segregation analysis |

GPF-SFARI, the Simons Foundation instance of this platform, provides both protected access to comprehensive genotypic and phenotypic data for SSC (Simons Simplex Collection) and SPARK collections, as well as public access to summary statistics and analysis tools [7]. The platform's versatility in handling diverse data types and family structures makes it particularly valuable for autism genetics research.

Experimental Protocols for SFARI Gene Validation

Whole-Exome Sequencing Analysis Protocol

The methodology from the comparative bioinformatics study provides a detailed protocol for validating SFARI Gene entries against experimental data [6]:

Sample Preparation

- Collect genomic DNA from ASD probands and parents (trios) using standardized saliva collection kits

- Ensure informed consent and ethical approval from institutional review boards

Sequencing and Quality Control

- Perform whole-exome sequencing with Illumina HiSeq sequencers using Illumina Nextera exome capture kit

- Align sequencing reads to current human genome build (GRCh38)

- Apply quality filters: remove variants with low read coverage (≤20 reads) or low genotype quality (GQ ≤50)

- Exclude common variants (population frequency >1% in gnomAD)

Variant Detection and Annotation

- Implement multiple complementary approaches:

- ACMG/AMP-based tools (InterVar, TAPES) for identifying pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants

- Likely gene-disrupting (LGD) detection (Psi-Variant) for protein-truncating and deleterious missense variants

- Apply Ensembl's Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) for functional annotation

- Use multiple in-silico prediction tools (SIFT, PolyPhen-2, CADD, REVEL, M-CAP, MPC) with standardized cutoffs

Validation Against SFARI Gene

- Compare detected variants with SFARI Gene database (n=1031 genes in 2022 version)

- Calculate performance metrics (PPV, OR, diagnostic yield) using SFARI Gene as reference standard

- Statistically analyze overlap between different detection methods

Data Integration and Visualization Workflow

SFARI Gene provides sophisticated data visualization tools that enable researchers to identify patterns and relationships within autism genetic data [4] [3]:

Human Genome Scrubber Implementation

- Visualize ASD candidate genes by chromosomal location across all 24 human chromosomes

- Filter results by gene score category or specific chromosomes

- Interpret vertical bar height as number of reports linking gene to ASD

- Use color coding to signify gene score categories

- Access detailed gene information by selecting specific genomic regions

Ring Browser Utilization

- Display overview of human genetic information using circular interface

- Visualize location and frequency of ASD candidate genes, CNVs, and protein interactions

- Identify potential functional relationships and genomic hotspots

Interactive Interactome Analysis

- Filter protein interaction types (protein binding, RNA binding, promoter binding, etc.)

- Explore connections between autism candidate genes

- Generate hypotheses about molecular pathways and networks

Research Reagent Solutions for SFARI Gene Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for SFARI Gene Validation

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Function in SFARI Gene Research |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina HiSeq Sequencers | Sequencing Platform | Generate whole-exome sequencing data for variant discovery |

| Nextera Exome Capture Kit | Library Preparation | Enrich exonic regions for comprehensive variant detection |

| Oragene DNA Collection Kits | Sample Collection | Standardized DNA isolation from saliva samples |

| Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) | Bioinformatics Pipeline | Variant calling, quality control, and filtering |

| InterVar | ACMG/AMP Implementation Tool | Classify variants as pathogenic, likely pathogenic, or VUS |

| TAPES | ACMG/AMP Implementation Tool | Alternative tool for variant classification |

| Psi-Variant | LGD Detection Pipeline | Integrates seven in-silico prediction tools for variant impact |

| Ensembl VEP | Variant Annotation | Functional consequence prediction for identified variants |

| gnomAD Database | Population Frequency | Filter common variants (>1% frequency) |

| SFARI Gene Database | Curated Knowledge Base | Gold standard for ASD gene validation (n=1031 genes) |

SFARI Gene represents a comprehensively validated resource that provides critical infrastructure for autism genetics research. Empirical evidence demonstrates its utility as a reference standard for evaluating variant detection methodologies, with studies showing significant statistical power for identifying true ASD-associated genes [6]. The integration of multifaceted data types—from human genetic studies to animal models and protein interactions—within a continuously updated, manually curated framework makes SFARI Gene an indispensable tool for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working to unravel the genetic architecture of autism spectrum disorder.

The platform's ongoing development, including quarterly updates and refinement of scoring criteria [8] [5], ensures that it remains at the forefront of autism research resources. By providing both comprehensive data access through the GPF platform [7] and sophisticated visualization tools [4] [3], SFARI Gene enables the autism research community to generate novel hypotheses and accelerate the translation of genetic discoveries into improved understanding and treatments for ASD.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by deficits in social interaction, impaired communication skills, and a range of stereotyped and repetitive behaviors. With an estimated heritability as high as 52% and hundreds of genes believed to be disrupted, understanding its genetic architecture is fundamental to advancing research and therapeutic development [9]. The Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI) has addressed this complexity by creating SFARI Gene, an expertly curated database that integrates genetic information from multiple research studies to provide a comprehensive resource on genes implicated in autism susceptibility [1] [9]. At the core of this database lies the Human Gene Module, which serves as a dynamic, actively updated repository of ASD candidate genes, offering researchers instant access to the most current information on human genes associated with ASD [4] [1].

The critical importance of such a curated resource becomes evident when considering the extreme genetic heterogeneity of autism. Recent large-scale genomic studies have revealed that the genetic diathesis towards ASD may be different for almost every individual, making this a prime candidate for the coming age of precision medicine [10]. The Human Gene Module provides a structured framework that helps researchers navigate this complexity by collecting, scoring, and organizing genes based on the strength of evidence linking them to ASD. This repository continues to evolve, with the most recent data indicating it contains 1,255 total genes as of October 2025, each meticulously categorized and scored to reflect current scientific understanding [11]. For researchers, clinicians, and drug development professionals, this module represents an indispensable tool for validating candidate genes, designing experiments, and developing targeted therapeutic strategies.

Comparative Analysis: Human Gene Module vs. Alternative Genomic Approaches

The landscape of genomic resources for autism research is diverse, ranging from general-purpose databases to specialized tools with distinct methodologies and applications. The SFARI Human Gene Module occupies a unique position within this ecosystem, differing significantly from both untargeted genomic discovery approaches and other gene databases in its specific focus on curated evidence for ASD association.

Table 1: Comparison of Genomic Approaches for ASD Candidate Gene Identification

| Feature | SFARI Human Gene Module | Untargeted Genomic Discovery (e.g., MSSNG) | General Gene Databases (e.g., GeneCards) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Expert-curated ASD-specific genes | Genome-wide variant discovery without pre-selection | General gene information without ASD-specific prioritization |

| Gene Scoring | Specific scoring system (1-3) reflecting ASD evidence strength | Statistical association from cohort studies | No ASD-specific scoring |

| Update Mechanism | Active curation of new ASD research | Periodic data releases from sequencing initiatives | General updates across all genes |

| Evidence Integration | Synthesizes genetic association, syndromic links, rare variants | Primarily variant-focused without evidence synthesis | Diverse evidence types but not ASD-integrated |

| ASD-Specific Features | Dedicated ASD relevance assessments, associated syndromes | Identification of novel variants in ASD cohorts | Limited ASD-specific contextualization |

| Therapeutic Application | Direct pathway to candidate genes for drug targeting | Potential novel targets but requires validation | Therapeutic targets across all diseases |

The distinct value proposition of the Human Gene Module becomes particularly evident when examining its structured approach to evidence evaluation. Unlike untargeted approaches such as the MSSNG initiative, which performs whole-genome sequencing of families with ASD to build resources for sub-categorization of phenotypes and genetic factors, the Human Gene Module provides synthesized, interpreted knowledge rather than raw data [10]. Whereas MSSNG reported an average of 73.8 de novo single nucleotide variants and 12.6 de novo insertion/deletions or copy number variations per ASD subject—emphasizing the challenge of identifying meaningful signals amidst noise—the Human Gene Module pre-filters this complexity to highlight genes with substantiated evidence [10]. This curated approach enables researchers to rapidly prioritize candidates for functional validation or therapeutic development.

Core Features and Data Structure of the Human Gene Module

Gene Scoring System and Categorization Framework

The Human Gene Module employs a sophisticated scoring system that categorizes genes based on the strength and quality of evidence linking them to ASD susceptibility. This scoring framework is critical for helping researchers prioritize genes for further investigation and resource allocation. The module assigns scores from 1 to 3, with Score 1 representing genes with the strongest evidence and high confidence of being implicated in ASD, Score 2 designating strong candidates, and Score 3 including genes with suggestive but not yet conclusive evidence [9]. Each gene's score is dynamically updated as new evidence emerges, with the database tracking scoring history to provide transparency into how evidence has evolved over time [4].

Beyond the numerical score, genes are categorized according to the nature of their association with autism. The module classifies genes into several Genetic Categories, including "Rare Single Gene Mutation," "Syndromic," "Genetic Association," and "Functional" evidence [11]. This multi-dimensional classification enables researchers to filter genes based on the type of evidence available. For example, the current database includes 1255 genes, with numerous genes falling into multiple categories simultaneously, reflecting the complex nature of ASD genetics [11]. The module also specifically tags Syndromic genes (denoted with "S" in the database)—those associated with genetic syndromes that include autism as a feature, such as ADNP, ADSL, and ANKRD11 [11]. This distinction is clinically valuable, as it helps differentiate between genes associated with broader syndromic presentations versus those more specifically linked to idiopathic autism.

Data Visualization and Navigation Tools

The Human Gene Module incorporates sophisticated data visualization tools to facilitate exploration and discovery. Central to this is the Human Genome Scrubber, an interactive visualization that displays the relative location of all known ASD-candidate genes throughout the human genome [4]. This scrubber represents genes as vertical bars along a horizontal axis displaying the 24 human chromosomes, with bar height indicating the number of individual reports linking a gene to ASD, and color signifying the assigned Gene Score [4]. Researchers can expand or contract the viewable region to examine large portions of the genome or focus on specific chromosomal locations, enabling both macro-level pattern recognition and micro-level investigation of gene clusters.

The module supports multiple search methodologies to accommodate different research needs. A Quick Search function allows for rapid filtering of the gene table based on any query, while an Advanced Search tool enables targeted queries using specific parameters such as gene scores, chromosomal location, genetic categories, associated disorders, and more [4]. Each gene in the module has a dedicated entry summary page that consolidates comprehensive information, including the assigned gene score, number of autism-specific reports compared to total relevant reports, rare and common variants, aliases, associated syndromes, genetic category, chromosome band, molecular function, and relevance to autism [4]. This structured presentation ensures that researchers can quickly access both high-level summaries and granular details as needed for their investigations.

Experimental Applications and Validation Protocols

Integrating Transcriptomic Data with SFARI Genes

One powerful application of the Human Gene Module is in the design and interpretation of transcriptomic studies aimed at validating ASD candidate genes. Research has demonstrated that SFARI genes exhibit statistically significant higher expression levels compared to other neuronal and non-neuronal genes, with a clear gradient relationship where higher SFARI scores (stronger evidence) correlate with higher expression levels [9]. This pattern has been consistently observed across multiple independent ASD gene expression datasets, suggesting that these genes may have crucial roles in maintaining normal brain function, and their dysregulation contributes to ASD pathogenesis [9].

The following experimental workflow illustrates a typical protocol for validating SFARI genes using transcriptomic approaches:

A critical methodological consideration when working with SFARI genes in transcriptomic studies is the need to account for expression level bias. Research has shown that classification models incorporating topological information from whole co-expression networks can successfully predict novel SFARI candidate genes that share features of existing SFARI genes, while individual gene or module analyses often fail to reveal these signatures [9]. This systems-level approach has proven more effective because it captures intricate shared patterns between genes that remain hidden when studying genes at a more local level.

Subtype-Specific Genetic Validation Protocols

Recent advances in autism subtyping have created new opportunities for validating SFARI genes within biologically distinct subgroups. A landmark 2025 study analyzing data from over 5,000 children in the SPARK cohort identified four clinically and biologically distinct subtypes of autism using a person-centered approach that considered over 230 traits [12]. These subtypes—Social and Behavioral Challenges (37% of participants), Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay (19%), Moderate Challenges (34%), and Broadly Affected (10%)—exhibit distinct genetic profiles, enabling more targeted validation of SFARI genes [12].

Table 2: Subtype-Specific Genetic Patterns Informing SFARI Gene Validation

| Autism Subtype | Prevalence | Distinct Genetic Features | SFARI Gene Validation Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social and Behavioral Challenges | 37% | Mutations in genes active later in childhood; highest rates of co-occurring psychiatric conditions | Focus on post-natal gene expression patterns; validate genes affecting synaptic function and neural circuits |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | 19% | Higher burden of rare inherited genetic variants | Prioritize genes with inherited mutation patterns; assess impact on early neurodevelopment |

| Moderate Challenges | 34% | Milder genetic liability with fewer damaging mutations | Validate genes with moderate effect sizes; consider polygenic risk contributions |

| Broadly Affected | 10% | Highest proportion of damaging de novo mutations | Focus on high-penetrance risk genes; assess impact on multiple developmental domains |

This subtyping framework enables more precise experimental designs for SFARI gene validation. For example, researchers can now test specific hypotheses about how various biological pathways link to different ASD presentations, rather than searching for a unified biological explanation encompassing all individuals with autism [12]. The Broadly Affected subgroup shows the highest proportion of damaging de novo mutations, suggesting that SFARI genes with de novo mutation evidence should be prioritized when studying this severe subtype [12]. Conversely, the finding that the Social and Behavioral Challenges subtype involves mutations in genes that become active later in childhood suggests a different validation timeline and functional focus for SFARI genes associated with this subgroup [12].

The validation of SFARI genes from the Human Gene Module relies on access to specialized research resources and biospecimens. Several key resources have been developed specifically to support this research, providing standardized materials that enable reproducible experimental outcomes.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for SFARI Gene Validation

| Resource Name | Provider | Key Features | Application in SFARI Gene Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simons Searchlight | Simons Foundation | Phenotypic and genomic data for 123 single-gene variants and 19 CNV conditions; >5,600 individuals | Validation of genotype-phenotype correlations for SFARI genes [13] |

| SPARK Cohort | Simons Foundation | Large-scale autism cohort with genetic and phenotypic data; >5,000 children | Subtype-specific validation of SFARI genes [12] |

| MSSNG Database | Autism Speaks & Collaborators | Whole-genome sequencing data from 5,205 ASD families; cloud-based access | Identification of novel variants in SFARI genes [10] |

| SFARI Biospecimen Repository | Simons Foundation | Cell lines (fibroblasts, lymphoblastoids, iPSCs) and DNA from participants | Functional characterization of SFARI gene variants [13] |

These resources collectively provide the foundational materials necessary for comprehensive SFARI gene validation. The Simons Searchlight resource, which released new data in July 2025 covering over 5,600 individuals with a genetic diagnosis, offers particularly valuable phenotypic and biospecimen data for validating genes against human clinical presentations [13]. The availability of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from participants enables the development of cellular models for functional characterization of SFARI gene variants, creating pathways from genetic discovery to mechanistic understanding [13].

Emerging Frontiers and Research Applications

From Gene Discovery to Therapeutic Development

The ultimate translational application of the Human Gene Module lies in its potential to accelerate the development of targeted therapies for ASD. Large-scale genomic studies have progressively identified ASD-associated genes, with whole-genome sequencing now facilitating the detection of risk noncoding variants in regulatory elements such as enhancers, promoters, and untranslated regions [14]. This expanding genetic understanding has revealed the complex interplay between rare and common variants in ASD liability, with genetic factors varying by sex and phenotypic profile [14] [12].

The pathway from SFARI gene identification to therapeutic development involves multiple validation stages, each with distinct methodological requirements:

While clinical application of these genomic insights remains in early stages, progress has been made in gene-based therapeutic development, interpretation of noncoding risk variants, and the use of polygenic scores for risk stratification [14]. The identification of biologically distinct autism subtypes further enhances these therapeutic opportunities by enabling more targeted approaches that account for the underlying genetic and biological heterogeneity of ASD [12].

Future Directions and Resource Enhancement

The evolving nature of the Human Gene Module ensures its continuing relevance to the ASD research community. Future developments will likely focus on enhanced integration of multi-omics data, improved functional annotations, and more sophisticated tools for visualizing and analyzing gene networks. The recent identification of autism subtypes provides a framework for gene validation within specific biological contexts, potentially increasing the predictive power of therapeutic development efforts [12].

The Simons Foundation's ongoing commitment to enhancing research resources is evidenced by initiatives such as the 2025 Data Analysis Request for Applications, which specifically encourages use of SFARI-supported resources to ask new questions and extract new knowledge from existing datasets [15]. This approach maximizes the research return on already-collected data while generating insights that can inform future research directions. As these resources continue to expand and integrate with other large-scale biomedical initiatives, the Human Gene Module is poised to remain an indispensable tool for validating ASD candidate genes and translating genetic discoveries into improved understanding and treatment of autism spectrum disorder.

The SFARI Gene database serves as a cornerstone resource for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) research, providing a systematically curated collection of genes implicated in autism susceptibility. As the number of genes associated with ASD continues to grow, researchers face the significant challenge of distinguishing definitive risk genes from those with weaker or less validated evidence. To address this critical need, the SFARI Gene Scoring Module implements a structured classification framework that categorizes genes based on the strength of evidence linking them to ASD risk [16]. This scoring system enables researchers to prioritize genes for further investigation and provides valuable context for interpreting new genetic findings.

The gene scoring process represents a collaborative effort between expert curators at MindSpec and a team of experienced autism geneticists who have established specific criteria for evaluating and ranking genes [16]. This systematic approach acknowledges that the scoring methodology is only one of many possible frameworks for evaluating gene-disease associations, with the explicit goal of encouraging rather than limiting future research. By providing transparent assessment criteria, the module helps researchers design targeted experiments to strengthen the evidence for each gene's association with ASD [17]. As of October 2025, the database contains 1,161 scored genes, with 94 remaining uncategorized, reflecting the dynamic nature of autism genetics research [17].

SFARI Gene Scoring Categories and Criteria

Comprehensive Scoring Framework

The SFARI Gene scoring system organizes genes into distinct categories that reflect the quality and quantity of evidence supporting their association with ASD. This hierarchical structure enables researchers to quickly identify genes with the strongest validation while maintaining awareness of emerging candidates with less conclusive evidence. The system employs four primary categories, with an additional specialized category for syndromic forms of autism [16].

Syndromic Category (S): This category includes genes in which mutations are associated with a substantial degree of increased ASD risk and are consistently linked to additional characteristics not required for an ASD diagnosis. These genes often originate from well-characterized genetic syndromes where autism represents one component of a broader clinical presentation. When a syndromic gene also has independent evidence implicating it in idiopathic ASD, it receives a combined designation (e.g., 1S, 2S, 3S). If no such independent evidence exists, the gene is designated simply as "S" [16]. The database currently contains 218 genes in the S category [17].

Category 1 (High Confidence): Genes in this category have been clearly implicated in ASD, typically through the presence of at least three de novo likely-gene-disrupting mutations reported in the literature. These genes meet rigorous statistical thresholds, with some achieving genome-wide significance and all meeting a false discovery rate threshold of < 0.1. Due to their strong validation, mutations in these genes identified in the SPARK cohort are typically returned to research participants [16].

Category 2 (Strong Candidate): This category includes genes with two reported de novo likely-gene-disrupting mutations. It also encompasses genes uniquely implicated by genome-wide association studies that either reach genome-wide significance or, if not, have been consistently replicated and are accompanied by evidence that the risk variant has a functional effect [16].

Category 3 (Suggestive Evidence): Genes in this tier represent more preliminary associations with ASD and include those with only a single reported de novo likely-gene-disrupting mutation. This category also includes evidence from significant but unreplicated association studies, or a series of rare inherited mutations without rigorous statistical comparison with controls [16].

Table 1: SFARI Gene Scoring Categories and Criteria

| Category | Evidence Requirements | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Syndromic (S) | Mutations associated with ASD plus additional characteristics beyond core diagnostic features | Understanding comorbidity patterns, syndrome-specific interventions |

| Category 1 | ≥3 de novo likely-gene-disrupting mutations; FDR < 0.1 | Highest priority for therapeutic development, recurrence risk counseling |

| Category 2 | 2 de novo likely-gene-disrupting mutations OR significant GWAS findings with functional validation | Target validation studies, pathway analysis |

| Category 3 | Single de novo mutation OR unreplicated association studies OR rare inherited mutations without rigorous controls | Preliminary investigations, gene discovery initiatives |

Comparison with Alternative Gene-Disease Validation Frameworks

While the SFARI Gene scoring system provides a specialized framework for ASD research, other systems exist for evaluating gene-disease relationships across different disorders. The Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen) has developed an evidence-based framework for assessing gene-disease validity that is implemented by Gene Curation Expert Panels (GCEPs) with specific domain expertise [18]. Unlike SFARI Gene, which focuses specifically on ASD, ClinGen's framework encompasses a broader range of disorders and employs a different classification system that includes Definitive, Strong, Moderate, and Limited categories for supported gene-disease relationships, plus Disputed and Refuted categories for contradictory evidence [18].

A key distinction between these frameworks lies in their scope and application. The SFARI system is optimized specifically for the complex genetic architecture of ASD, where multiple genes of varying effect sizes contribute to risk. In contrast, ClinGen's framework is designed for broader application across genetic disorders, with specific expert panels focusing on particular disease domains. The ClinGen Syndromic Disorders GCEP (SD-GCEP), for example, specifically addresses genes associated with rare syndromic disorders involving multiple organ systems [18]. Between April 2020 and March 2024, this panel curated 111 gene-disease relationships across 100 genes, classifying 78 as Definitive, 9 as Strong, 15 as Moderate, and 9 as Limited [18].

Experimental Approaches for Gene Validation

Methodologies for Gene-Disease Association Studies

Research validating genes within the SFARI database employs multiple methodological approaches, each with specific protocols and applications. Gene co-expression network analysis has emerged as a powerful systems biology approach for studying the relationship between ASD-specific transcriptomic data and SFARI genes. This method constructs networks where genes are connected based on similarity in their expression patterns across samples, allowing researchers to identify modules of co-expressed genes that may represent functional pathways relevant to ASD [19].

The standard protocol for this approach involves several key steps. First, RNA sequencing data is collected from postmortem brain tissue of ASD patients and neurotypical controls. The data is then processed through quality control, normalization, and batch effect correction procedures. Next, a gene co-expression network is constructed using algorithms such as Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA), which identifies modules of highly interconnected genes. These modules are then tested for association with ASD diagnosis and enrichment of SFARI genes. Finally, network topology measures are used to identify genes that share characteristics with known SFARI genes within the co-expression network [19].

A 2022 study applying this methodology revealed important insights about SFARI genes. Surprisingly, SFARI genes showed no significant enrichment in gene co-expression network modules that strongly correlated with ASD diagnosis, nor were they significantly associated with differential gene expression patterns when comparing ASD samples to controls [19]. However, classification models that incorporated topological information from the entire ASD-specific gene co-expression network successfully predicted novel SFARI candidate genes that shared features with existing SFARI genes and had literature support for roles in ASD [19].

Transcriptomic Analysis of SFARI Genes

Transcriptomic analyses have revealed distinctive characteristics of SFARI genes that may inform their biological roles in ASD. Research has demonstrated that SFARI genes have statistically significant higher expression levels than other neuronal and non-neuronal genes [19]. This pattern persists when SFARI genes are separated by their score categories, with Category 1 genes showing the highest expression levels, followed by Category 2 and then Category 3 genes. All differences between groups were statistically significant, except between Category 3 genes and other neuronal genes [19].

Table 2: SFARI Gene Expression Characteristics Based on Scoring Categories

| Gene Category | Expression Level | Differential Expression in ASD | Co-expression Network Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Category 1 | Highest expression | Lowest log fold-change | Central positioning in high-expression modules |

| Category 2 | Intermediate expression | Intermediate log fold-change | Variable network topology |

| Category 3 | Lower expression (comparable to neuronal genes) | Higher log fold-change | Peripheral network positioning |

| Non-SFARI Neuronal | Lower than SFARI genes | Highest log fold-change | Distributed across modules |

Interestingly, despite their elevated expression levels, SFARI genes show smaller differences in expression between ASD and control patients compared to other neuronal genes. When examining the magnitude of log fold-change, SFARI genes had statistically significant lower values than genes with neuronal functions, with Category 1 genes showing the lowest values, followed by Category 2 and Category 3 genes [19]. This suggests that the role of high-confidence SFARI genes in ASD may not primarily involve gross changes in their expression levels in postmortem brain tissue, but rather more subtle regulatory disruptions or the effects of rare mutations.

Signaling Pathways and Analytical Workflows

Gene Co-expression Network Analysis Pipeline

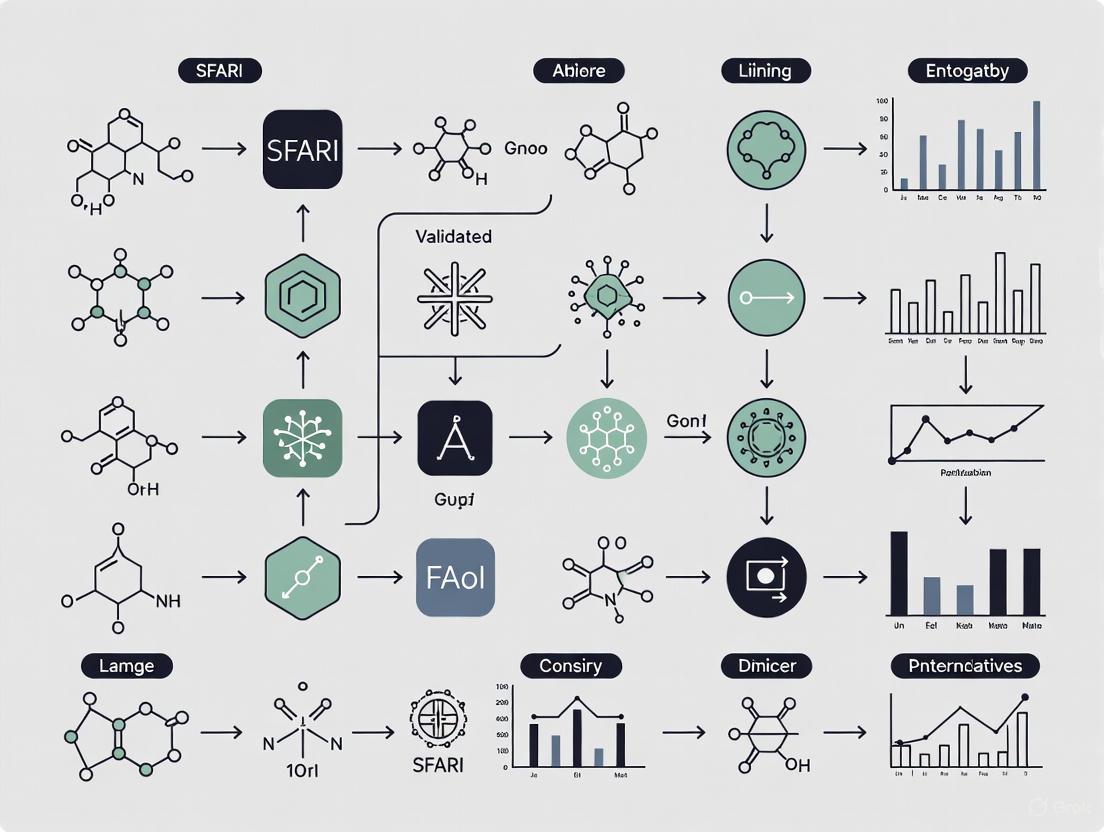

The analytical workflow for integrating SFARI gene scores with transcriptomic data involves multiple stages that progress from data acquisition through network construction to validation. The following diagram illustrates this comprehensive pipeline:

Gene Co-expression Network Analysis Workflow

This workflow begins with RNA-seq data acquisition from ASD and control brain tissues, followed by rigorous quality control and normalization to address technical variability. The construction of the co-expression network typically employs the WGCNA algorithm, which identifies modules of highly interconnected genes. These modules are then analyzed for SFARI gene enrichment and correlated with ASD diagnosis. Simultaneously, network topology analysis examines the position and connectivity patterns of SFARI genes within the global network structure. The final stages involve predicting novel candidate genes based on their network properties and validating these predictions through literature review and functional analyses [19].

SFARI Gene Integration in Research Pathways

The application of SFARI gene scores in ASD research extends beyond transcriptomic analyses to inform multiple experimental pathways. The following diagram illustrates how SFARI gene categories integrate with various research approaches:

SFARI Gene Integration in Research Pathways

This framework demonstrates how different SFARI gene categories guide distinct research trajectories. Category 1 genes, with their strong validation, are frequently prioritized for therapeutic target validation and serve as anchors for pathway and network analyses. Category 2 genes often become subjects for animal model generation to further validate their functional roles in ASD-related phenotypes. Category 3 genes typically feed into gene discovery and prioritization efforts, where additional evidence is collected to potentially reclassify them into higher categories. Syndromic genes provide critical insights for clinical genetics and diagnostics, helping to establish genotype-phenotype correlations in complex ASD cases [17] [16] [19].

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

The Scientist's Toolkit for SFARI Gene Research

Research investigating genes within the SFARI framework relies on specialized tools and resources that enable comprehensive analysis of gene-disease relationships. The following table details key resources available to researchers in this field:

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for SFARI Gene Investigation

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| SFARI Gene Database | Curated database | Centralized repository of ASD-associated genes with evidence scores | Gene prioritization, literature review, dataset integration |

| Human Gene Module | Database component | Detailed information on human genes associated with ASD | Candidate gene evaluation, mutation interpretation |

| Animal Models Module | Database component | Data from animal models of ASD risk genes | Functional validation, mechanistic studies |

| Copy Number Variant Module | Database component | Collection of CNVs associated with ASD | Genomic disorder analysis, structural variant interpretation |

| Gene Curation Interface | Curation tool | Standardized framework for evaluating gene-disease evidence | Gene-disease validity assessment, evidence synthesis |

| WGCNA Algorithm | Bioinformatics tool | Weighted gene co-expression network construction | Transcriptomic network analysis, module detection |

| ClinGen Framework | Evaluation framework | Evidence-based criteria for gene-disease validity | Methodological comparison, clinical interpretation |

The SFARI Gene database itself represents the most fundamental resource, providing not only the scoring matrix but also integrated access to additional modules including the Human Gene Module, which offers comprehensive data on human genes associated with ASD; the Animal Models Module, containing information from animal studies of ASD risk genes; and the Copy Number Variant Module, which catalogs structural variants associated with autism [20] [1]. These interconnected resources provide multiple avenues for investigating ASD genetics.

For experimental validation, the Gene Curation Interface used by ClinGen provides a structured framework for evaluating gene-disease relationships based on genetic and experimental evidence [18]. This tool implements standardized criteria for assessing genetic evidence (such as de novo mutations and inheritance patterns) and experimental evidence (including functional studies and animal models), enabling consistent evaluation across different genes and disorders. Bioinformatics tools like the WGCNA algorithm facilitate transcriptomic analyses that reveal how SFARI genes operate within broader gene regulatory networks [19].

The SFARI Gene Scoring Module provides an indispensable framework for navigating the complex genetic landscape of autism spectrum disorder. By categorizing genes based on the strength of evidence supporting their association with ASD—from syndromic forms to high-confidence candidates and suggestive associations—this system enables researchers to prioritize targets for mechanistic studies, therapeutic development, and clinical translation. The integration of these scores with transcriptomic data through network-based approaches has revealed that SFARI genes possess distinctive characteristics, including elevated expression levels and specific network properties, that may reflect their crucial roles in neurodevelopment.

While the SFARI framework offers ASD-specific evaluation criteria, complementary systems like ClinGen provide additional validation contexts, particularly for syndromic disorders involving multiple organ systems [18]. The ongoing refinement of these scoring systems, coupled with emerging methodologies in network analysis and functional genomics, continues to enhance our understanding of autism's genetic architecture. As these resources evolve, they will undoubtedly continue to shape research strategies and accelerate the translation of genetic discoveries into improved outcomes for individuals with ASD.

Leveraging the Animal Models Module for Functional Validation Insights

The identification of candidate genes associated with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) represents a significant breakthrough, yet it is merely the first step. Databases like SFARI Gene aggregate genetic evidence from human studies, cataloging genes with varying degrees of association confidence [21] [3]. However, the translation of these genetic lists into biological understanding and therapeutic targets necessitates rigorous functional validation. This is where the SFARI Gene Animal Models Module transitions from a repository of information to an indispensable tool for hypothesis-driven research. This guide compares the integrated use of this module against alternative validation strategies, providing a framework for researchers to design robust experimental workflows for confirming the pathogenic role of ASD candidate genes.

Comparative Landscape: SFARI Animal Models vs. Alternative Validation Platforms

The functional validation of a candidate gene can be approached through multiple, often complementary, methodologies. The table below objectively compares the core attributes of leveraging SFARI's curated animal model data against other common strategies.

Table 1: Comparison of Functional Validation Approaches for ASD Candidate Genes

| Validation Approach | Core Description | Key Strengths | Primary Limitations | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFARI Gene Animal Models Module | A manually curated database summarizing published phenotypic data from genetically modified animal lines (primarily mice) for ASD-linked genes [3] [20]. | Provides pre-synthesized, peer-reviewed evidence; highlights relevant behavioral & cellular phenotypes; guides model selection [3]. | Dependent on existing literature; may not include models for novel genes; species limitations. | Prioritization & Hypothesis Generation: Quickly assessing existing in vivo evidence for a gene of interest. |

| De Novo Animal Model Generation | Creating novel transgenic, knockout, or knock-in animal lines (e.g., via CRISPR/Cas9) targeting the candidate gene [22] [23]. | Enables bespoke model design; allows study of specific mutations; gold standard for causal validation [23]. | High cost, long timelines (6+ months); ethical and regulatory complexities [24] [23]. | Definitive Causal Testing: Establishing the necessity and sufficiency of a gene variant in causing ASD-relevant phenotypes. |

| In Silico & AI-Powered Analysis | Using computational tools to predict gene function, pathway involvement, or interactions (e.g., GeneAgent) [25]. | Rapid, low-cost; scalable for analyzing gene sets; can integrate multi-omics data [25]. | Prone to hallucinations without verification; predictive, not demonstrative [25]. | Preliminary Screening & Network Analysis: Identifying potential biological processes and candidate pathways prior to wet-lab experiments. |

| In Vitro Models (Organoids, Cell Lines) | Using human-derived stem cells to create 2D or 3D neuronal culture systems modeling early brain development [24] [23]. | Human genetic background; can study early neurodevelopment; amenable to high-throughput screening [24]. | Lack complex circuit-level behaviors; immature cell states; no integrated systemic physiology. | Mechanistic Dissection: Studying cell-autonomous molecular and cellular phenotypes in a human context. |

A critical insight from recent studies is the substantial inconsistency between major ASD gene databases. An analysis of four specialized databases (AutDB, SFARI Gene, GeisingerDBD, SysNDD) found only 1.5% consistency in their classification of high-confidence ASD genes, driven by differing scoring criteria and evidence interpretation [21]. This starkly underscores why functional validation is non-negotiable—a gene's presence on a list is not a guarantee of its biological role.

Quantitative Benchmarks and Experimental Data Synthesis

The value of a resource is measured by its reliability and coverage. A systematic assessment of ASD genetic databases provides the following quantitative benchmarks for SFARI Gene [21]:

Table 2: Database Quality Metrics for ASD Candidate Gene Sources

| Database | Schema-Level Completeness | Data-Level Completeness | Consistency (High-Confidence Genes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SFARI Gene | 89% | Not Specified | 1.5% (across 4 databases) |

| AutDB | Not Specified | 90% | 1.5% (across 4 databases) |

| GeisingerDBD | Not Specified | Not Specified | 1.5% (across 4 databases) |

| SysNDD | Not Specified | Not Specified | 1.5% (across 4 databases) |

Schema-level completeness refers to the presence of all expected data fields (e.g., gene score, model phenotypes, interactions), while data-level completeness measures the proportion of those fields that are populated with actual data [21]. SFARI Gene's high schema-level completeness (89%) indicates a well-structured resource capable of integrating diverse data types, a prerequisite for effective research planning.

The broader context of preclinical research further validates the centrality of animal models. The global animal model market, valued at USD 2.0 billion in 2025, is projected to grow at a 6.0% CAGR, driven by pharmaceutical R&D and the demand for genetically engineered models [22]. Mice dominate this market with a 65% share, attributable to their genetic tractability and established relevance to human disease [22]. In drug discovery applications, which account for 55% of the market, the use of genetically engineered models has been shown to improve disease modeling accuracy by up to 40% compared to traditional laboratory animals [22]. This industry-wide reliance provides a pragmatic backdrop for utilizing the SFARI Animal Models Module to select the most translationally relevant model systems.

Experimental Protocol: A Roadmap from Database to Validation

The following generalized protocol outlines a systematic approach to leveraging the SFARI Gene Animal Models Module for designing a functional validation study.

Protocol: Functional Validation of an ASD Candidate Gene Using Pre-Clinical Models

Step 1: Candidate Identification & Prioritization via SFARI Gene

- Query the SFARI Gene

Human Genemodule for your gene of interest (e.g.,SHANK3). - Record the Gene Score and Classification (Rare, Syndromic, Association, Functional) to understand the evidence strength [3].

- Navigate to the Animal Models Module tab on the gene's summary page.

- Analyze the curated data: extract details on existing animal models (species, strain, genetic construct), summarized phenotypic findings (behavioral, electrophysiological, morphological), and key supporting references [20].

Step 2: Hypothesis & Experimental Design Formulation

- Based on the module's summary, formulate a specific hypothesis. Example: "Heterozygous deletion of Gene X in mice will replicate social interaction deficits and altered synaptic density in the prefrontal cortex, as suggested by prior models."

- Determine the validation strategy:

- If a suitable model exists: Acquire the existing mouse line from a repository (e.g., The Jackson Laboratory).

- If no model exists / requires a novel allele: Design a CRISPR/Cas9-mediated strategy to create a knockout or knock-in model, contracting a specialist service provider if needed [23].

- Define primary (e.g., social approach in three-chamber test) and secondary (e.g., western blot for protein expression, spine density analysis) outcome measures.

Step 3: Model Generation & Phenotyping (Example: Novel Mouse Model)

- gRNA Design & Microinjection: Design two sgRNAs flanking a critical exon or to introduce a specific point mutation. Perform microinjection into C57BL/6J fertilized zygotes.

- Genotyping & Colony Expansion: Screen founders by PCR and Sanger sequencing. Establish a stable heterozygous breeding line.

- Comprehensive Phenotyping Battery:

- Behavioral: Conduct tests for core ASD-relevant domains: social interaction (three-chamber test), repetitive behavior (marble burying, self-grooming), communication (ultrasonic vocalizations), and anxiety (elevated plus maze) [26].

- Molecular/Biochemical: Validate target gene/protein disruption via qRT-PCR and western blot from brain tissue homogenates.

- Neurohistological: Perform immunohistochemistry on brain sections (e.g., prefrontal cortex, hippocampus) for synaptic markers (PSD-95, VGLUT1) and quantify spine density using Golgi-Cox staining.

Step 4: Data Integration & Cross-Referencing

- Compare your experimental results against the phenotypes documented in the SFARI Animal Models Module for related genes or models.

- Use the Protein Interaction (PIN) Module to explore molecular networks and identify potential downstream effectors or parallel pathways for mechanistic follow-up [3] [20].

- Contribute novel, peer-reviewed findings back to the research community, completing the validation cycle.

Title: Functional Validation Workflow for ASD Candidate Genes

Successful execution of the validation protocol depends on access to specific reagents and platforms. The following table details key solutions.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for ASD Gene Validation

| Item | Function in Validation Pipeline | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| SFARI Gene Database | Primary source for curated genetic evidence and existing animal model data to guide experimental design [3] [20]. | Publicly available at gene.sfari.org. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing System | Enables precise generation of knockout or knock-in animal models to test gene causality [22] [23]. | Commercial kits from suppliers like Cyagen or GenOway, or designed in-house. |

| Validated Animal Model Lines | Ready-to-use murine models for genes with established links, saving time on model generation. | Repositories like The Jackson Laboratory (JAX) or Charles River Laboratories. |

| Behavioral Testing Equipment | Standardized apparatus to quantify core ASD-relevant phenotypes (social, repetitive, cognitive). | Three-chamber social test box, open field, elevated plus maze, rotarod. |

| Synaptic Protein Antibodies | Key reagents for molecular validation of gene disruption and downstream pathway analysis in brain tissue. | Antibodies against PSD-95, SHANK3, Synapsin, GAD67 (from suppliers like Cell Signaling, Synaptic Systems). |

| AI-Powered Gene Set Analysis Tool | Computational tool to contextualize findings within broader biological pathways and check for reasoning errors [25]. | NIH's GeneAgent or similar platforms for cross-verification against curated databases. |

Visualizing the Validation Pathway: From Gene to Phenotype

A candidate gene's role in ASD is often mediated through disruption of specific neurodevelopmental pathways. The diagram below illustrates a generalized signaling pathway that might be investigated following a clue from the SFARI Animal Models Module, such as noted alterations in synaptic protein levels.

Title: Example Pathway from Synaptic Gene Disruption to ASD-like Phenotypes

The SFARI Gene Animal Models Module is not a standalone answer but a powerful launchpad for functional validation. Its true value is realized when its curated data is actively used to design rigorous, hypothesis-driven experiments in vivo. By cross-referencing database insights with de novo model generation and complementary in vitro or in silico approaches, researchers can navigate the complex and often inconsistent landscape of ASD genetics [21]. This integrated strategy moves beyond cataloging associations to definitively establishing biological causality, thereby de-risking the arduous path from gene discovery to therapeutic intervention. In an era where genetically engineered animal models remain crucial—demonstrated by their growing market and continuous technological refinement [22] [23]—leveraging curated knowledge to guide their application is the hallmark of efficient and impactful translational neuroscience.

Utilizing the Copy Number Variant (CNV) Module for Structural Variation Analysis

Copy Number Variants (CNVs) are structural variations in DNA sequence, typically greater than 1 kilobase in length, that include gains and losses of gene copies and are recognized as major genetic factors underlying human diseases [27] [28]. In the context of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) research, the SFARI Gene database serves as a crucial resource, providing a comprehensively annotated list of genes and CNVs associated with autism susceptibility [1] [3]. The CNV module within SFARI Gene specifically catalogs single-gene and multi-gene deletions and duplications and describes their potential link to autism, forming an essential component for validating candidate genes in ASD research [3] [20].

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with SFARI Gene, accurate CNV detection is paramount for understanding human genetic diversity, elucidating disease mechanisms, and advancing personalized medicine approaches [27]. The CNV module operates alongside experimental data generated by various computational tools, and understanding the performance characteristics of these tools is essential for proper interpretation of CNV data within the SFARI framework. This guide provides an objective comparison of CNV detection tools and their application within the SFARI Gene research context, enabling researchers to make informed decisions about their analytical approaches.

CNV Detection Tools: Methodologies and Comparative Performance

Core Detection Methodologies

CNV detection tools employ distinct computational methodologies to identify structural variations from sequencing data. These approaches can be broadly categorized into five strategic classes [27]:

- Read Depth (RD): Analyzes variations in sequencing coverage to identify regions with copy number changes. Tools like CNVkit and CNVnator utilize this approach [27].

- Pair-End Mapping (PEM): Examines the orientation and insert size between paired-end reads to detect structural rearrangements. BreakDancer employs this methodology [27].

- Split Reads (SR): Identifies reads that split across breakpoints, providing precise boundary information. Tools like Delly incorporate this strategy [27].

- Assembly (AS): Reconstructs sequences from reads to compare against the reference genome [27].

- Combined Approaches: Integrate multiple signals (RD, PEM, SR) for improved detection. LUMPY and TARDIS exemplify this comprehensive approach [27].

Most specialized CNV tools primarily use read-depth strategies, while general structural variant tools employ a wider range of approaches, making them capable of detecting CNVs alongside other variant types [27].

Comprehensive Tool Performance Comparison

Recent benchmarking studies have evaluated CNV detection tools across multiple parameters including variant length, sequencing depth, and tumor purity. The following table summarizes the performance characteristics of widely used tools based on a comprehensive 2025 evaluation of 12 representative detection tools on both simulated and real data [27]:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of CNV Detection Tools

| Tool | Signals Used | Best Performance For | Key Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNVkit | RD | General-purpose CNV detection | Active maintenance (updated 2024), widely adopted | Read-depth only approach |

| Delly | PEM, SR | Comprehensive SV detection | Integrates multiple signals, regularly updated | |

| LUMPY | SR, PEM | Complex variant detection | Combined approach improves accuracy | Last update 2022 |

| Control-FREEC | RD | CNV detection with controls | Active development | Read-depth only approach |

| Manta | PEM | Rapid variant calling | Optimized for speed | Last update 2019 |

| TIDDIT | PEM | Population studies | Active maintenance | Pair-end mapping only |

| BreakDancer | PEM | Traditional PEM detection | Established method | Last update 2015 |

| GROM-RD | RD | Basic RD analysis | Simple implementation | No recent updates |

For targeted NGS panel data used in diagnostic settings, specialized tools have demonstrated particular effectiveness. A 2020 benchmark evaluating five tools on 495 samples with 231 validated CNVs found that DECoN and panelcn.MOPS showed the highest performance for CNV screening before orthogonal confirmation, with DECoN detecting all CNVs except one mosaic variant while maintaining specificity greater than 0.90 with optimized parameters [29].

Impact of Experimental Conditions on Tool Performance

Tool performance varies significantly based on experimental conditions and variant characteristics. A comprehensive 2025 analysis revealed that factors including variant length, sequencing depth, and tumor purity substantially impact detection accuracy [27]:

- Variant Length: Shorter variants (1Kb-10Kb) are frequently overlooked or filtered out, while longer variants (100Kb-1Mb) are more readily detected by most tools [27]

- Sequencing Depth: Performance generally improves with higher sequencing depths (5x to 30x), though different tools show varying efficiency gains across depth ranges [27]

- Tumor Purity: In cancer samples, lower tumor purity (0.4 vs 0.8) significantly reduces detection accuracy due to signal confounding, particularly in the absence of normal controls [27]

- CNV Type: Detection capability varies across different CNV types, with tools showing differential performance for tandem duplications, interspersed duplications, inverted tandem duplications, inverted interspersed duplications, heterozygous deletions, and homozygous deletions [27]

Experimental Protocols for CNV Validation in SFARI Gene Research

Benchmarking Framework and Evaluation Metrics

Comprehensive evaluation of CNV detection tools employs standardized benchmarking frameworks that assess performance across multiple metrics. The CNVbenchmarkeR framework provides a structured approach for tool comparison using both simulated and real datasets [29]. The experimental workflow encompasses several critical stages, as visualized below:

Figure 1: CNV Tool Benchmarking Workflow

The evaluation metrics employed in comprehensive benchmarks include [27] [29]:

- Precision: Proportion of correctly identified CNVs among all predicted CNVs

- Recall (Sensitivity): Proportion of true CNVs correctly identified by the tool

- F1 Score: Harmonic mean of precision and recall

- Boundary Bias: Accuracy in determining CNV boundaries

- Overlapping Density Score (ODS): Used for real data evaluation

- False Positive Rate: Proportion of negative regions incorrectly flagged as CNVs

For real data evaluation where ground truth may be incomplete, the Overlapping Density Score (ODS) provides a robust metric for comparing tool performance by measuring the consensus between different callers [27].

Data Processing and Analysis Workflow

The standard workflow for CNV detection from NGS data involves multiple processing stages, each with specific quality control checkpoints. The following protocol outlines the key experimental steps:

Sample Preparation and Sequencing

- Extract high-quality genomic DNA from target samples (blood, tissue, or cell lines)

- Prepare sequencing libraries using validated protocols (PCR-free preferred for CNV detection)

- Sequence using Illumina platforms (or other NGS technologies) with recommended minimum coverage of 30x for whole genome studies [27]

Data Preprocessing and Alignment

- Quality control of raw reads using FastQC or similar tools

- Adapter trimming and quality filtering

- Alignment to reference genome (GRCh38 recommended) using BWA-MEM or similar aligners [29]

- Post-alignment processing including sorting, indexing, and duplicate marking

CNV Calling and Analysis

- Execute selected CNV detection tools with optimized parameters

- For SFARI Gene integration, focus on genes and regions previously implicated in ASD

- Compare calls across multiple tools to establish high-confidence CNV set

- Annotate CNVs with gene information, functional impact, and population frequency

Validation and Interpretation

- Orthogonal validation using MLPA, aCGH, or digital PCR for selected CNVs [29]

- Compare identified CNVs with SFARI Gene CNV module entries

- Interpret findings in context of ASD relevance using SFARI Gene scoring system

Integration with SFARI Gene for Candidate Gene Validation

SFARI Gene CNV Module Features and Capabilities

The SFARI Gene CNV module provides specialized resources for autism researchers investigating copy number variations. Key features include [3]:

- CNV Scrubber: A visualization tool that provides quantitative analysis of CNVs across chromosomal loci, showing the number of CNVs found at particular locations, the number of reports curated, and whether a CNV is primarily caused by deletion or duplication [3]

- Ring Browser: An interactive circular visualization that displays CNV data in genomic context alongside other SFARI Gene information [20]

- Expert Curation: All CNV entries are manually curated from peer-reviewed literature with detailed annotations about their association with ASD [3]

- Integration with Gene Scoring: CNV data is interconnected with SFARI's gene-level evidence scores for ASD association [1]

The module specifically catalogs recurrent CNVs and provides access to CNV calls for the Simons Simplex Collection, offering researchers a valuable reference for interpreting their own findings [1].

Gene Classification System in SFARI Gene

SFARI Gene employs a structured classification system for autism-related genes, which directly informs the interpretation of CNV findings [3]:

Table 2: SFARI Gene Classification Categories

| Category | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Rare | Genes implicated in rare monogenic forms of ASD | SHANK3, rare polymorphisms, single gene disruptions |

| Syndromic | Genes implicated in syndromic forms of autism | Angelman syndrome, fragile X syndrome |

| Association | Small risk-conferring candidate genes from association studies | Common polymorphisms in idiopathic ASD |

| Functional | Functional candidates relevant for ASD biology | CADPS2 (based on animal model evidence) |

This classification framework enables researchers to prioritize CNV findings based on the strength of evidence linking affected genes to autism pathogenesis. A gene can belong to multiple categories depending on the specific mutation type and evidence [3].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful CNV analysis in SFARI Gene research requires both laboratory reagents and computational resources. The following toolkit represents essential components for comprehensive CNV studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for CNV Analysis

| Category | Item | Function | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | High-quality DNA extraction kits | Obtain pure, high-molecular-weight DNA for sequencing | Qiagen Blood & Cell Culture DNA Kit |

| Library preparation kits | Prepare sequencing libraries | Illumina DNA PCR-Free Prep | |

| Target enrichment panels | Focus sequencing on specific gene sets (for panel-based approaches) | TruSight Cancer Panel, I2HCP | |

| MLPA reagents | Orthogonal validation of CNV calls | MRC Holland MLPA kits | |

| Computational Tools | Alignment software | Map sequencing reads to reference genome | BWA-MEM, HISAT2 |

| CNV detection tools | Identify copy number variations from aligned data | See Table 1 for options | |

| Visualization tools | Interpret and validate complex CNVs | SVTopo, IGV, CNV Scrubber | |

| Annotation databases | Interpret functional impact of CNVs | SFARI Gene, DGV, ClinVar | |

| Reference Data | Reference genomes | Standardized genomic coordinate system | GRCh38 (recommended) |

| Control samples | Normalize read depth calculations | Public datasets (ICR96) | |

| Population databases | Filter common polymorphisms | gnomAD, DGV |

For specialized visualization of complex structural variants, particularly those involving inverted sequences or multiple breakend pairs, SVTopo provides enhanced capabilities for interpreting supporting evidence from high-accuracy long reads [30]. This is particularly valuable for complex CNVs that may be difficult to interpret with standard visualization tools.

CNV analysis plays a crucial role in validating candidate genes within autism research, and the integration of robust detection tools with the SFARI Gene CNV module enables comprehensive assessment of structural variations in ASD. The comparative data presented in this guide demonstrates that tool selection must be guided by specific research contexts, including sequencing approach (whole genome vs. targeted), variant characteristics, and available computational resources.

For researchers utilizing the SFARI Gene database, a combined approach leveraging multiple complementary tools with orthogonal validation provides the most reliable framework for CNV detection and interpretation. The experimental protocols outlined here offer a standardized methodology for generating CNV data that can be meaningfully integrated with SFARI Gene's curated knowledge base, ultimately advancing our understanding of the genetic architecture of autism spectrum disorders.

Investigating Protein-Protein Interactions with the PIN Module

In the field of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) research, resources like the SFARI Gene database provide curated evidence on candidate genes associated with the condition [1] [21]. However, establishing biological validity for these genetic findings requires moving beyond simple gene lists to understanding their functional context within cellular systems. Protein-Protein Interaction Networks (PINs) provide this essential biological context, revealing how genes orchestrate cellular functions through complex relationships. The PIN module approach refines these networks to more accurately identify functionally relevant protein communities, offering a powerful framework for validating SFARI candidate genes by examining their positions and relationships within the broader interactome.

This guide compares the PIN module method against alternative network analysis approaches, providing experimental data and protocols to help researchers select the optimal strategy for their gene validation workflows.

Comparative Analysis of PPI Network Refinement Methods

Key Methods for PPI Network Analysis

Table 1: Comparison of Protein-Protein Interaction Network Analysis Methods

| Method | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Limitations | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIN Module Refinement | Discovers critical functional modules by integrating orthology, localization, and topology [31]. | Optimally improves essential protein identification; superior precision-recall metrics [31]. | Requires multiple data types; computationally intensive for very large networks. | Validating SFARI genes within functional contexts; identifying key functional modules. |

| Static PPI (S-PIN) | Uses unchanging, cataloged interactions from databases [31]. | Simple to implement; widely available; high coverage. | High false positive/negative rates; lacks biological context [31]. | Preliminary screening; studies where dynamic data is unavailable. |

| Dynamic PPI (D-PIN) | Filters interactions using gene expression timing to create context-specific networks [32]. | More biologically relevant than S-PIN; reveals condition-active interactions. | Dependent on quality/completeness of expression data. | Studying condition-specific mechanisms (e.g., cell cycle, stress response). |

| Functional Role Decomposition | Groups proteins by interaction patterns rather than dense connectivity [33]. | Identifies functionally related proteins that do not form dense clusters (e.g., transmembrane receptors) [33]. | Results can be less intuitive than module-based approaches. | Discovering non-modular functional associations; understanding network roles. |

| Exact Optimization (MWCS) | Uses integer-linear programming to find maximally scoring connected subnetworks [34]. | Provides provably optimal solutions; integrates multiple data types via node scoring [34]. | Computationally demanding for massive networks; requires specialized expertise. | High-confidence identification of dysregulated pathways in disease. |

Performance Comparison in Essential Protein Identification

Experimental validation demonstrates how these methods improve upon basic network analysis. A 2024 study evaluated 12 node-ranking methods on different network types, measuring the number of essential proteins correctly identified at different top-ranking cutoffs [31].

Table 2: Experimental Performance in Identifying Essential Proteins (Sample Data for Top 100-600 Rankings)

| Network Type | Average Number of Essential Proteins Identified (Top 100-600) | Improvement Over S-PIN | Statistical Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CM-PIN (Module-Based) | 285 | Baseline (Best) | N/A |

| RD-PIN (Localization-Filtered) | 248 | ~15% less than CM-PIN | < 0.05 |

| D-PIN (Expression-Filtered) | 230 | ~19% less than CM-PIN | < 0.05 |

| S-PIN (Static) | 195 | ~32% less than CM-PIN | < 0.01 |

The CM-PIN, constructed using the module-based refinement method, consistently and significantly outperformed all other network types across multiple metrics, including the number of essential proteins identified, Jackknifing analysis, and precision-recall curves [31]. This demonstrates that module-aware refinement creates a higher-quality network for identifying biologically critical elements.

Experimental Protocols for PIN Module Analysis

Protocol 1: Constructing a Critical Module PIN (CM-PIN)

This protocol outlines the specific steps for building a refined network using the module-based approach, which has shown superior performance in identifying essential proteins [31].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Network Preparation: Begin with a Static PPI Network (S-PIN) from a reliable database such as HPRD or STRING. Extract the maximal connected subgraph to ensure network continuity for downstream analysis [31].

Module Discovery: Apply the Fast-unfolding algorithm to partition the maximal connected subgraph into distinct modules or communities. This algorithm maximizes modularity, grouping densely connected nodes together [31].

Critical Module Identification: Score and rank the discovered modules based on their biological and topological relevance. The scoring should integrate:

- Orthologous Information: Conservation across species.

- Subcellular Localization: Co-localization of proteins within the same cellular compartment.

- Topological Features: Internal connectivity and other network properties [31]. Select the top-ranked, or "critical," modules based on this aggregated score.

CM-PIN Construction: Construct the final refined network (CM-PIN) comprising only the proteins and interactions contained within the selected critical modules. This network serves as the high-quality input for subsequent candidate gene validation [31].

Protocol 2: Integrating SFARI Gene Data with PIN Modules

This protocol describes how to overlay SFARI candidate genes onto a refined PIN module to assess their functional context.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Data Extraction: Obtain your list of candidate genes from the SFARI Gene database, noting their confidence scores (e.g., SFARI Gene Score) [1].

Network Mapping: Map these candidate genes onto the nodes of your previously constructed CM-PIN.

Topological Analysis: Calculate key network metrics for the candidate genes:

- Degree Centrality: Number of immediate interaction partners.

- Betweenness Centrality: Frequency of appearing on the shortest path between other nodes, indicating a broker or bridge role.

- Closeness Centrality: Average shortest path distance to all other nodes, indicating potential for rapid functional influence [31] [34].

Module Context Analysis: Determine if candidate genes are enriched within specific critical modules. Perform a statistical enrichment test (e.g., hypergeometric test) to check if SFARI genes are over-represented in any particular module compared to random expectation.

Functional Validation: Interpret the results. A candidate gene's role as a highly connected hub within a critical module, or as a connector (high betweenness) between modules, strongly supports its biological relevance to the network's function and, by extension, to ASD pathophysiology.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for PIN Module Analysis

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| PPI Databases | HPRD, STRING, DIP [34] [32] | Source of raw, static protein-protein interaction data to build the initial network. |

| Gene Expression Data | GEO, ArrayExpress | Provides condition-specific temporal data to construct dynamic PINs (D-PIN) or validate active modules [32]. |

| Annotation Databases | Gene Ontology (GO), Subcellular Localization databases | Provides functional and spatial context for proteins, used for scoring module criticality and interpreting results [31] [32]. |

| Specialized Gene Databases | SFARI Gene [1] [21] | Curated source of autism candidate genes for mapping and validation within the network context. |

| Module Detection Tools | ModuleDiscoverer [35], Fast-unfolding algorithm [31] | Software and algorithms for identifying functional modules or communities within the larger PPI network. |