Systems Biology in Neurology: From Molecular Networks to Personalized Therapies for Brain Disorders

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how systems biology is revolutionizing our understanding and treatment of complex neurological diseases.

Systems Biology in Neurology: From Molecular Networks to Personalized Therapies for Brain Disorders

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how systems biology is revolutionizing our understanding and treatment of complex neurological diseases. It explores the foundational shift from reductionist approaches to holistic network-based analyses of the brain. The content details key methodological applications, including multi-omics integration, computational modeling, and network analysis, with specific case studies in Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and multiple sclerosis. It further addresses challenges in clinical translation, such as data integration and model robustness, and examines validation strategies through cross-species studies and clinical trials. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes how systems biology is paving the way for predictive diagnostics and personalized therapeutic interventions in neurology.

The Systems View of the Brain: Moving Beyond Reductionism in Neurology

Systems biology represents a fundamental shift in biological research, moving from a traditional reductionist approach to a holistic paradigm that seeks to understand complex biological systems as integrated wholes rather than collections of isolated parts. This interdisciplinary field combines biology, mathematics, computer science, and physics to study complex interactions within biological systems, using a holistic approach (holism instead of the more traditional reductionism) to biological research [1]. The core philosophy of systems biology is succinctly captured by Denis Noble, who states that it "is about putting together rather than taking apart, integration rather than reduction. It requires that we develop ways of thinking about integration that are as rigorous as our reductionist programmes, but different" [1].

In the context of neurological diseases, systems biology has emerged as a crucial framework for understanding pathogenesis that cannot be reconciled solely with the currently available tools of molecular biology and genomics [2]. The pluralism of causes and effects in biological networks is better addressed by observing, through quantitative measures, multiple components simultaneously and by rigorous data integration with mathematical models [2]. This approach is particularly valuable for neuroscience, where the complexity of the brain necessitates methods that can handle the dynamic interactions between genes, proteins, and metabolites that influence cellular activities and organism traits [1].

Core Principles of Systems Biology

The Principle of Holism

Holism represents the foundational principle that distinguishes systems biology from traditional reductionist approaches. This principle emphasizes understanding the behavior of the system as a whole, rather than just its individual parts [3]. Where reductionism has successfully identified most biological components and many interactions, it offers no convincing concepts or methods to understand how system properties emerge from these interactions [1]. Systems biology addresses this gap by focusing on emergent properties—characteristics of cells, tissues, and organisms functioning as a system whose theoretical description is only possible using systems biology techniques [1].

In neurological research, holism enables researchers to analyze the brain as a complex system rather than focusing on individual neurons or molecules in isolation [4]. For example, studying Alzheimer's disease through a holistic lens allows researchers to understand how interactions across multiple cellular networks contribute to disease progression, rather than attributing pathology to a single protein or gene [5]. This holistic perspective is essential because the individual components rarely illustrate the function of a complex system, and we now recognize that we need approaches for reconstructing integrated systems from their constituent parts and processes to comprehend biological phenomena [1].

The Principle of Interdisciplinarity

Interdisciplinarity forms the operational backbone of systems biology, combining insights and techniques from multiple fields including biology, mathematics, computer science, and physics [4] [3]. This collaborative approach is necessary because the multifaceted research domain requires the combined expertise of chemists, biologists, mathematicians, physicists, and engineers to decipher the biology of intricate living systems by merging various quantitative molecular measurements with carefully constructed mathematical models [1].

The interdisciplinary nature of systems biology is particularly evident in its application to neurological disease research. For instance, network-based analyses of genes involved in hereditary ataxias have demonstrated a set of pathways related to RNA splicing, revealing a novel pathogenic mechanism for these diseases [2]. This approach requires biologists to characterize molecular components, computer scientists to develop analysis algorithms, and mathematicians to create models that can predict system behavior—a true integration of disciplines that provides insights impossible to obtain from any single field alone.

The Principle of Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative analysis provides the methodological foundation for systems biology, using mathematical and computational models to analyze and simulate complex biological systems [4]. This principle employs tools developed in physics and mathematics such as nonlinear dynamics, control theory, and modeling of dynamic systems to create quantitative frameworks typically used by engineers [2]. The main goal is to solve questions related to the complexity of living systems such as the brain, which cannot be reconciled solely with the currently available tools of molecular biology and genomics [2].

In practice, quantitative analysis enables researchers to develop predictive models of complex biological systems, simulate system behavior under various conditions, and test hypotheses about system behavior [4]. For neurological disorders, this might involve modeling mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease to identify potential therapeutic targets [4]. The quantitative framework allows for precise predictions that can be experimentally validated, creating a cycle of model refinement that progressively enhances our understanding of complex neurological systems.

Table 1: Core Principles of Systems Biology and Their Applications in Neuroscience

| Core Principle | Key Definition | Application in Neurological Research |

|---|---|---|

| Holism | Understanding the system as a whole, rather than just its individual parts [4] | Analyzing the brain as a complex system; studying network interactions in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease [4] |

| Interdisciplinarity | Combining insights and techniques from multiple fields [4] | Integrating neurobiology with computational modeling to identify novel disease mechanisms [2] |

| Quantitative Analysis | Using mathematical and computational models to analyze and simulate complex biological systems [4] | Developing predictive models of disease progression and therapeutic interventions [4] |

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Omics Technologies and Data Acquisition

Omics technologies form the data acquisition backbone of systems biology, enabling comprehensive analysis of biological systems at various molecular levels. These technologies provide the large-scale quantitative data necessary for constructing and validating models of complex biological systems [4] [1]. The primary omics approaches include genomics (study of complete genetic makeup), transcriptomics (analysis of complete sets of RNA molecules), and proteomics (large-scale study of entire sets of proteins) [4]. The emergence of multi-omics technologies has transformed systems biology by providing extensive datasets that cover different biological layers, enabling a more profound comprehension of biological processes and interactions [1].

The experimental workflow for omics data acquisition in neurological research typically begins with sample preparation from relevant biological sources (brain tissue, cerebrospinal fluid, blood). For genomics, researchers employ high-throughput sequencing technologies to characterize genetic variations and epigenetic modifications. Transcriptomics utilizes RNA sequencing to quantify gene expression patterns across different neurological conditions. Proteomics employs mass spectrometry-based techniques to identify and quantify protein expression and post-translational modifications. Metabolomics completes the picture by profiling small molecule metabolites using NMR or mass spectrometry. Critical to this process is maintaining consistent sample processing protocols, implementing rigorous quality control measures, and utilizing appropriate normalization strategies to ensure data quality and comparability across experiments.

Data Analysis and Computational Modeling

Once omics data is acquired, sophisticated computational tools and techniques are employed for analysis and interpretation. Common approaches include dimensionality reduction techniques (e.g., PCA, t-SNE) to simplify complex datasets, clustering and network analysis to identify patterns and relationships, and data visualization tools (e.g., heatmaps, scatter plots) to facilitate interpretation of results [4]. Increasingly, methods such as network analysis, machine learning, and pathway enrichment are utilized to integrate and interpret multi-omics data, thereby improving our understanding of biological functions and disease mechanisms [1].

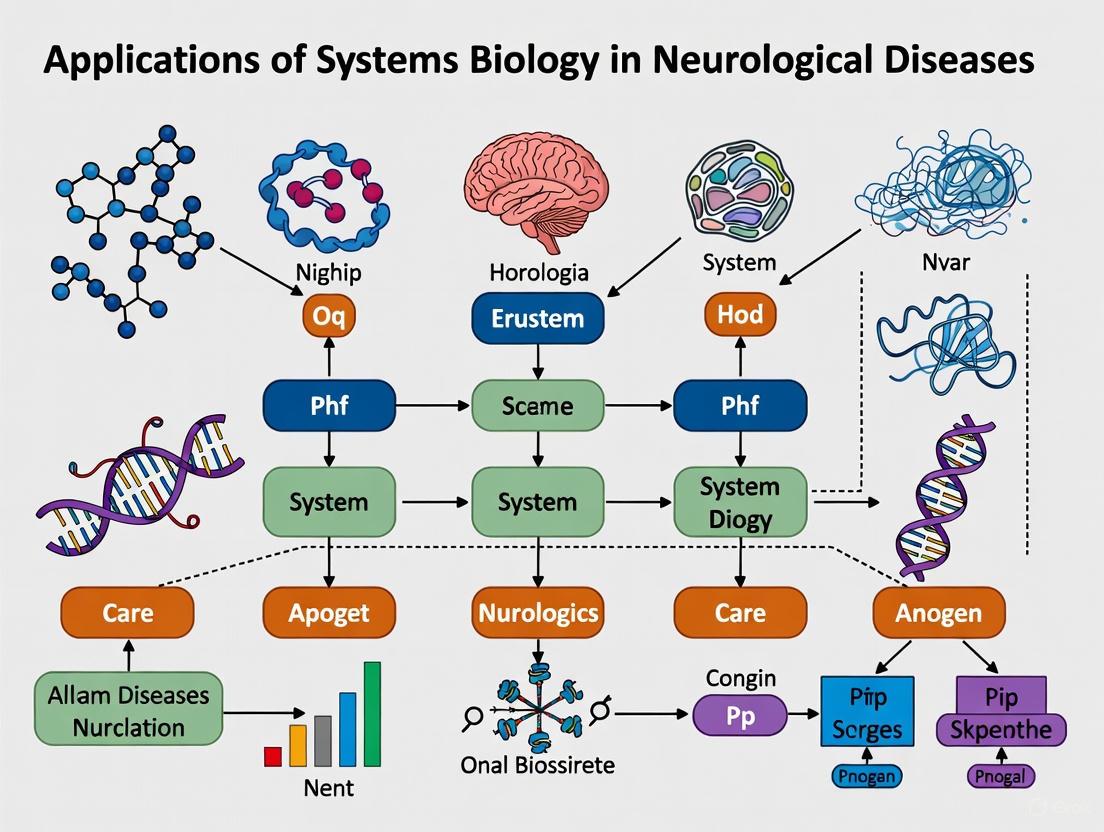

Mathematical modeling and simulation are essential components of systems biology that enable researchers to develop predictive models of complex biological systems, simulate system behavior under various conditions, and test hypotheses [4]. Common mathematical modeling approaches include ordinary differential equations (ODEs) for modeling dynamics of biochemical reactions and other continuous processes, Boolean networks for modeling behavior of gene regulatory networks and other discrete systems, and agent-based modeling for simulating behavior of complex systems composed of interacting agents [4]. The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of systems biology approaches:

Diagram 1: Systems Biology Research Workflow

Network Analysis in Neurological Disorders

Network analysis provides a powerful framework for understanding the complex interactions in neurological systems. Cellular networks are a crucial aspect of systems biology as they provide a framework for understanding how individual components interact to give rise to emergent properties [3]. Several types of cellular networks are analyzed in neurological research, including gene regulatory networks (describing interactions between genes, transcription factors, and other regulatory elements that control gene expression), protein-protein interaction networks (describing physical interactions between proteins crucial for signaling pathways and other cellular functions), and metabolic networks (describing biochemical reactions that occur within cells) [3].

Methods for analyzing network topology and dynamics include network visualization using tools such as Cytoscape, calculation of network metrics (degree distribution, betweenness centrality, clustering coefficient), and dynamic modeling using mathematical models to simulate network behavior under different conditions [3]. The insights gained from network analysis have been profound, including identification of key regulatory nodes that play crucial roles in controlling cellular behavior, understanding disease mechanisms by analyzing topology and dynamics of cellular networks, and predicting cellular response to different perturbations such as genetic mutations or environmental changes [3]. The following diagram illustrates a simple gene regulatory network:

Diagram 2: Gene Regulatory Network

Table 2: Computational Modeling Approaches in Systems Biology

| Modeling Approach | Key Features | Applications in Neurology |

|---|---|---|

| Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) | Models dynamics using differential equations capturing rates of change of different variables [4] [3] | Modeling biochemical reaction kinetics in neurotransmitter systems [4] |

| Boolean Networks | Uses logical rules to govern interactions between network nodes [4] [3] | Modeling gene regulatory networks in neurodevelopment [4] |

| Stochastic Models | Captures inherent noise and variability using probabilistic equations [3] | Modeling synaptic transmission and variability in neural circuits [3] |

| Agent-Based Modeling | Simulates behavior of complex systems composed of interacting agents [4] | Modeling cellular interactions in neuroinflammatory conditions [4] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Implementing systems biology approaches in neurological research requires a specific set of research tools and reagents that enable the acquisition, analysis, and integration of multi-scale data. The following table details essential materials and their applications in systems neuroscience research:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Systems Biology in Neurology

| Research Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Sequencers | Comprehensive genomic and transcriptomic profiling | Enables genomics (study of complete genetic makeup) and transcriptomics (analysis of complete sets of RNA molecules) [4] |

| Mass Spectrometers | Proteomic and metabolomic analysis | Facilitates proteomics (large-scale study of entire protein sets) and metabolic profiling [4] |

| Cytoscape Software | Network visualization and analysis | Used for creating network representations of network topology and analyzing complex biological networks [3] |

| RNA/DNA Extraction Kits | High-quality nucleic acid isolation | Critical for preparing samples for genomic and transcriptomic analyses from neurological tissues |

| Protein Assay Kits | Protein quantification and characterization | Essential for proteomic studies to quantify protein expression and post-translational modifications |

| Mathematical Modeling Software | Computational model development and simulation | Platforms for implementing ODEs, Boolean networks, and other modeling approaches [4] |

Applications in Neurological Disease Research

Understanding Disease Mechanisms

Systems biology approaches have revolutionized our understanding of neurological disease mechanisms by providing comprehensive frameworks for analyzing complex pathological processes. By analyzing the complex interactions within biological systems, researchers can identify novel therapeutic targets for neurological disorders [4]. For example, targeting specific gene regulatory networks can help identify key transcription factors or regulatory elements that drive disease progression, while modulating protein-protein interactions can reveal novel interactions critical for disease mechanisms [4].

Network-based analysis is challenging the current nosology of neurological diseases and contributing to the development of patient-specific therapeutic approaches, bringing the paradigm of personalized medicine one step closer to reality [2]. In Alzheimer's disease, systems biology approaches have identified key pathways and networks involved in disease progression beyond the traditional amyloid and tau hypotheses [4]. In Parkinson's disease, systems biology has elucidated the role of mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in disease pathogenesis, revealing interconnected networks that contribute to neuronal vulnerability [4]. The application of these approaches has been particularly fruitful in mapping topographical patterns localized to specific brain regions, thereby targeting disease-specific areas for intervention [5].

Drug Discovery and Personalized Medicine

Systems biology facilitates the development of personalized medicine approaches by integrating genomic and clinical data to predict patient responses to therapy and identify potential therapeutic targets [4]. This approach enables the development of patient-specific models to simulate disease progression and test therapeutic interventions [4]. The potential of computational neuroscience might pave the way for comprehensive methods for evaluating and optimizing the efficacy of drugs for neurological conditions [5].

The bottom-up approach in systems biology facilitates the integration and translation of drug-specific in vitro findings to the in vivo human context, particularly in early phases of drug development including safety evaluations [1]. When assessing cardiac safety of neurological medications, a purely bottom-up modeling and simulation method entails reconstructing the processes that determine exposure, including plasma (or heart tissue) concentration-time profiles and their electrophysiological implications [1]. The separation of data related to the drug, system, and trial design, characteristic of the bottom-up approach, allows for predictions of exposure-response relationships considering both inter- and intra-individual variability, making it a valuable tool for evaluating drug effects at a population level [1].

Table 4: Applications of Systems Biology in Neurological Disorders

| Neurological Disorder | Systems Biology Approach | Findings/Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease | Analysis of gene regulatory networks and protein-protein interactions [4] | Identified key pathways beyond amyloid hypothesis; potential for targeting specific tau protein kinases [4] |

| Parkinson's Disease | Modeling mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress [4] | Elucidated interconnected networks contributing to neuronal vulnerability; opportunities for modulating mitochondrial function [4] |

| Hereditary Ataxias | Network-based analysis of disease genes [2] | Identified pathways related to RNA splicing as novel pathogenic mechanism [2] |

| Neuropsychiatric Disorders | Multi-omics integration and network analysis [5] | Revealed synaptic mechanisms underlying depression, addiction, and schizophrenia [5] |

Systems biology, with its core principles of holism, interdisciplinarity, and quantitative analysis, represents a transformative approach to understanding and treating neurological diseases. By integrating experimental data, computational models, and theoretical frameworks, this paradigm enables researchers to study the brain as a complex system rather than through isolated components [4]. The application of systems biology in molecular neuroscience has far-reaching implications, allowing researchers to elucidate molecular mechanisms underlying neurological disorders, identify novel therapeutic targets, and develop personalized medicine approaches [4].

As the field continues to evolve, we can expect significant advances in our understanding of the brain and the development of more effective interventions for neurological conditions. The integration of multi-omics technologies, advanced computational modeling, and network analysis provides unprecedented opportunities to decipher the complexity of neurological systems and their dysfunction in disease states [1] [5]. This knowledge will ultimately contribute to the development of patient-specific therapeutic approaches, bringing the paradigm of personalized medicine one step closer to reality for neurological disorders [2].

The human brain represents one of the most complex systems in the known universe, characterized by an extraordinary density of interconnected components operating across multiple scales. Traditional reductionist approaches, which seek to understand biological systems by isolating and studying individual elements, have proven insufficient for unraveling the brain's profound complexity. The systems approach addresses this limitation by recognizing that the brain's functional properties—including cognition, memory, and adaptive behavior—emerge from dynamic, non-linear interactions among its constituent parts rather than from any single component in isolation [6]. This paradigm shift is particularly crucial for understanding neurological diseases, which increasingly appear to arise from disruptions across multiple interacting systems rather than from single causative factors.

The core thesis of this whitepaper is that a systems biology framework is not merely beneficial but essential for meaningful progress in neurological disease research. By integrating multi-omic data, computational modeling, and advanced experimental models, researchers can move beyond descriptive phenomenology toward mechanistic, network-level understandings of disease pathogenesis. This approach reveals that the brain's robustness under normal conditions—its ability to maintain function despite perturbation—arises from architectural principles such as degeneracy (the ability of structurally distinct elements to perform overlapping functions) and distributed redundancy [7] [8]. These same principles, when compromised, contribute to the system-wide failures characteristic of neurodegenerative diseases. The application of systems biology is therefore transforming our approach to disease modeling, therapeutic target identification, and drug development for conditions such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

The Architectural Principles of Brain Complexity

The brain's complexity operates across multiple interconnected scales, from molecular interactions within cells to coordinated activity across entire neural networks. This hierarchical organization exhibits specific architectural principles that confer both robust function and a susceptibility to specific failure modes.

Degeneracy and Robustness in Neural Systems

Degeneracy, a fundamental source of biological robustness, refers to the capacity of structurally distinct elements to perform overlapping functions under certain conditions while maintaining specialized roles under others [7]. Unlike pure redundancy, where identical components perform the same function, degeneracy involves multi-functional components with partial functional overlap. In the brain, this principle manifests at multiple levels:

- Molecular and Genetic Levels: Multiple gene regulatory networks and signaling pathways can produce similar functional outputs, allowing the system to maintain stability despite genetic variations or molecular perturbations [7].

- Circuit Level: Different neural circuit configurations can generate similar patterns of network activity or behavioral outputs, providing fault tolerance against localized damage [8].

- Cognitive Level: Multiple distributed brain regions can contribute to cognitive processes like memory, enabling functional compensation after injury.

This degeneracy creates a paradoxical relationship between robustness and evolvability. While robustness maintains system stability, the accumulation of cryptic genetic variation within degenerate systems provides a reservoir of potential adaptations, enhancing the system's capacity to evolve novel solutions when faced with new environmental challenges [7]. The intimate relationship between degeneracy and complexity suggests that more complex systems typically exhibit higher degrees of degeneracy, which in turn facilitates the evolution of even greater complexity.

Multi-Scalar Integration and Emergent Properties

The brain's functional properties emerge from the integration of processes operating across different temporal and spatial scales. These emergent properties cannot be predicted by studying any single level in isolation and include fundamental processes such as learning, memory, and consciousness. The following table summarizes key architectural principles and their functional implications:

Table 1: Architectural Principles Underlying Brain Complexity and Robustness

| Architectural Principle | Functional Role | Manifestation in Neural Systems | Disease Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degeneracy | Enables robustness and adaptability | Multiple neural pathways can mediate similar cognitive functions | Failure of compensatory mechanisms in neurodegeneration |

| Modularity | Facilitates specialized processing and fault isolation | Columnar organization in neocortex; distinct functional brain networks | Selective vulnerability of specific modules in disease |

| Hierarchical Organization | Enables efficient information processing | Micro-scale (molecular), meso-scale (circuits), macro-scale (networks) | Pathway-specific disruption in neurodegenerative diseases |

| Network Architecture | Supports integration and segregation of information | Small-world topology with highly connected hubs | Hub vulnerability in Alzheimer's and other connectopathies |

| Surface Area Maximization | Enhances computational capacity and interface surfaces | Cortical folding; dendritic arborization; synaptic density | Reduced complexity in aging and neurodegeneration |

Systems Biology Methodologies for Brain Research

The practical application of systems biology to neurological research requires the integration of diverse experimental and computational methodologies. These approaches enable researchers to move from descriptive observations to predictive, network-level models of brain function and dysfunction.

Multi-Omic Integration and Computational Modeling

Systems biology employs a suite of high-throughput technologies to capture molecular complexity at multiple levels, generating data sets that require sophisticated computational approaches for integration and analysis:

- Genomics and Transcriptomics: Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and single-cell RNA sequencing identify genetic risk factors and cell-type-specific expression patterns associated with neurological diseases [9].

- Proteomics and Phosphoproteomics: Mass spectrometry-based approaches quantify protein abundance and post-translational modifications, revealing signaling network alterations in disease states [9] [6].

- Metabolomics: Profiling of small molecules provides insights into metabolic pathway dysregulation in neurodegenerative processes [9].

- Network Modeling: Computational integration of multi-omic data using graph theory and machine learning identifies key regulatory hubs and interconnections within biological networks [9] [6].

The integration of these diverse data types enables the construction of comprehensive network models that reveal how perturbations at one level (e.g., genetic risk factors) propagate through the system to produce functional consequences at other levels (e.g., altered neural circuit activity). A representative workflow for this integrative approach is depicted below:

Diagram 1: Systems biology workflow for neurological disease research. This integrative approach combines multi-omic data acquisition with computational modeling and experimental validation to identify and prioritize therapeutic targets.

Advanced Experimental Models for Systems-Level Investigation

Traditional reductionist models are insufficient for capturing the emergent properties of neural systems. Recent technological advances have produced more sophisticated experimental platforms that better recapitulate the complexity of human brain tissue:

- Brain Organoids: Three-dimensional structures derived from human pluripotent stem cells that replicate key aspects of human brain organization and cellular diversity [10]. These models self-organize to form neural circuits that exhibit functional properties, including spontaneous electrical activity and synaptic plasticity—the cellular basis of learning and memory [11].

- Multicellular Integrated Brains (miBrains): A recently developed 3D human brain tissue platform that integrates all six major brain cell types (neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia, and vascular cells) into a single culture system [12]. This model replicates key brain structures, cellular interactions, and pathological features while allowing precise control over cellular inputs and genetic backgrounds.

- Cross-Species Validation Platforms: Tools such as the NIH BRAIN Initiative's gene delivery systems enable targeted manipulation of specific cell types across different species, facilitating the translation of findings from model systems to human biology [13].

Table 2: Advanced Experimental Models for Systems Neuroscience

| Model System | Key Features | Applications in Disease Research | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Organoids | 3D architecture, multiple neural cell types, synaptic plasticity, developmental modeling [10] [11] | Neurodevelopmental disorders, neurodegenerative disease mechanisms, drug screening | Limited vascularization, variability in generation, fetal-stage maturation |

| miBrains | All six major brain cell types, neurovascular units, blood-brain barrier functionality, modular design [12] | Cell-cell interactions in neurodegeneration, personalized medicine, drug delivery studies | Complex production protocol, not all brain regions represented |

| Transgenic Animal Models | Intact organismal context, behavioral readouts, established genetic manipulations | Validation of human findings, circuit-level mechanisms, behavioral pharmacology | Species-specific differences in biology and pathology |

| Human Brain Gene Delivery Systems | Cell-type-specific targeting across species, AAV-based delivery, computational enhancer identification [13] | Precision gene therapies, pathway validation in multiple biological contexts | Delivery efficiency, immune responses, translational challenges |

Applications in Neurological Disease Research

The systems approach is yielding transformative insights into the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases by revealing how localized molecular disruptions propagate through biological networks to produce system-wide dysfunction.

Case Study: Alzheimer's Disease Mechanisms Through a Systems Lens

Alzheimer's disease provides a compelling example of how systems biology approaches are reshaping our understanding of neurodegenerative processes. Traditional approaches focused predominantly on two pathological proteins: amyloid-β and tau. However, systems-level analyses have revealed that the disease involves coordinated dysfunction across multiple cellular pathways and systems:

- Multi-Omic Integration in Alzheimer's: A recent integrative study combined genomics, proteomics, phosphoproteomics, and metabolomics data from Drosophila models of Alzheimer's disease with human neuronal expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) to define mechanisms underlying neurodegeneration [9]. This approach identified how the Alzheimer's genetic risk factors HNRNPA2B1 and MEPCE enhance tau toxicity, and demonstrated that screen hits CSNK2A1 and NOTCH1 regulate DNA damage responses in both Drosophila and human stem cell-derived neural progenitor cells.

- Cross-Cellular Communication in Pathology: Research using miBrain models has revealed that molecular cross-talk between microglia and astrocytes is required for the development of phosphorylated tau pathology in Alzheimer's disease [12]. When APOE4 miBrains (carrying the Alzheimer's risk gene variant) were cultured without microglia, phosphorylated tau production was significantly reduced, demonstrating the essential role of intercellular interactions in disease pathogenesis.

- Network-Level Transcriptomic Changes: Analysis of human post-mortem brain tissues has shown that the expression of human orthologs of neurodegeneration screen hits declines with age and Alzheimer's disease, with particularly strong changes in vulnerable regions such as the hippocampus and frontal cortex [9].

The diagram below illustrates the systems-level understanding of Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis that emerges from these integrated approaches:

Diagram 2: Systems view of Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. The diagram illustrates how genetic risk factors propagate through molecular and cellular networks, ultimately leading to neural system failure and clinical symptoms.

Experimental Protocols for Systems-Level Investigation

To implement a systems approach in neurological disease research, specific experimental protocols have been developed that enable comprehensive, multi-scale investigation:

Protocol 1: Integrative Multi-Omic Analysis of Neurodegenerative Mechanisms

This protocol, adapted from a recent Nature Communications study, outlines a comprehensive approach for defining mechanisms of neurodegeneration through data integration [9]:

- Genetic Screening: Perform genome-scale forward genetic screening for age-associated neurodegeneration in Drosophila models using neuronal RNAi knockdown of 5,261 genes. Age flies for 30 days and assess brain integrity through blinded scoring of neuronal loss and vacuolation.

- Multi-Omic Profiling: Conduct proteomic, phosphoproteomic, and metabolomic analyses in Drosophila models expressing human Alzheimer's disease proteins (amyloid-β and tau).

- Human Genetic Integration: Generate RNA-sequencing data from pyramidal neuron-enriched populations from human temporal cortex using laser-capture microdissection. Identify expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) in disease-vulnerable neurons.

- Network Modeling Integration: Integrate model organism data with human Alzheimer's disease GWAS hits, proteomics, and metabolomics using advanced network modeling approaches.

- Cross-Species Validation: Test computational predictions experimentally in both Drosophila models and human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural progenitor cells.

Protocol 2: Multicellular Brain Model Development and Application

This protocol, based on the recently developed miBrain platform, enables the creation of complex, human-derived brain models for disease research [12]:

- Cell Generation: Develop six major brain cell types (neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia, vascular endothelial cells, and pericytes) from patient-donated induced pluripotent stem cells using established differentiation protocols.

- Matrix Preparation: Create a hydrogel-based "neuromatrix" using a custom blend of polysaccharides, proteoglycans, and basement membrane components that mimics the brain's extracellular matrix.

- Cell Proportion Optimization: Experimentally iterate cell type ratios to achieve functional neurovascular units. The established balance results in self-assembling structures with blood-brain barrier functionality.

- Genetic Manipulation: Utilize the modular design to introduce specific genetic variants (e.g., APOE4) into individual cell types while maintaining other cell types with reference genotypes (e.g., APOE3).

- Pathway Analysis: Apply single-cell RNA sequencing, immunostaining, and functional assays to identify cell-cell interactions and pathway dysregulation in disease models.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The implementation of systems approaches requires specialized research tools and reagents designed to capture and manipulate biological complexity. The following table details key research solutions referenced in the studies cited in this review:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Systems Neuroscience

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function and Application | Key Features and Benefits | Representative Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAV Gene Delivery Systems (NIH BRAIN Initiative) [13] | Targeted gene delivery to specific neural cell types in brain and spinal cord | Species-independent application, exceptional targeting accuracy, enables manipulation without transgenic animals | Precision gene therapy development, neural circuit manipulation, cell-type-specific pathway analysis |

| miBrain Platform [12] | 3D human brain tissue model integrating all major brain cell types | Contains six major brain cell types, modular design, personalized to individual genomes, blood-brain barrier functionality | Alzheimer's disease mechanism studies, cell-cell interaction analysis, personalized medicine applications |

| Brain Organoid Protocols [10] [11] | 3D stem cell-derived models of brain development and function | Recapitulate brain organization, exhibit synaptic plasticity and network activity, human-specific system | Neurodevelopmental disorder modeling, drug screening, learning and memory mechanism studies |

| Multi-Omic Integration Platforms [9] [6] | Computational frameworks for integrating genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data | Network-based analysis, identification of key regulatory hubs, cross-species data integration | Alzheimer's disease pathway discovery, biomarker identification, therapeutic target prioritization |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing | Precise genetic manipulation in stem cells and model organisms | Enables introduction of disease-associated mutations, creation of isogenic controls, high specificity | Introduction of APOE4 and other risk variants, functional validation of candidate genes, pathway manipulation |

The complexity of the brain demands a systems approach that matches the sophistication of its biological organization. By embracing network-level analyses, multi-scale integration, and complex experimental models, researchers are moving beyond reductionist limitations toward a more comprehensive understanding of neurological health and disease. The principles of degeneracy, modularity, and emergent properties that underlie normal brain function also provide a framework for understanding how system-wide failures occur in neurodegenerative diseases.

The application of systems biology to neurological diseases is already yielding tangible advances, from the identification of novel therapeutic targets to the development of more predictive disease models. As these approaches mature, they promise to transform how we diagnose, classify, and treat neurological disorders—moving from symptom-based descriptions to mechanism-based interventions that address the network-level dysfunctions underlying disease. The integration of systems biology with neurological research represents not merely a methodological shift but a fundamental reimagining of how we study, understand, and ultimately treat diseases of the brain.

Limitations of Traditional Reductionist Methods in Polygenic Neurological Diseases

Traditional reductionist approaches have long dominated biomedical research, operating on the principle that complex systems can be understood by isolating and studying their individual components. While this paradigm has proven successful for Mendelian disorders characterized by single-gene mutations, it demonstrates significant limitations when applied to polygenic neurological diseases. Conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and schizophrenia arise from complex interactions between hundreds or thousands of genetic variants, each contributing modest effects, alongside environmental factors and epigenetic modifications. This whitepaper examines the fundamental constraints of reductionist methodologies in capturing the emergent properties, non-linear dynamics, and complex network interactions that characterize polygenic neurological disorders. Furthermore, it frames these limitations within the broader context of systems biology applications, which offer a more integrative, multidimensional framework for understanding disease pathogenesis and developing effective therapeutic interventions.

The Fundamental Disconnect: Reductionism in a Polygenic Context

Core Principles and Inherent Limitations

Reductionism operates on several core principles that become limiting in the context of polygenic diseases. First, it employs a component-isolation approach, breaking down systems into constituent parts for individual study. While this allows detailed characterization of single elements, it inherently overlooks emergent properties that arise only through component interactions [2]. Second, reductionism typically assumes linear causality, seeking straightforward cause-effect relationships that poorly represent the complex, non-linear dynamics of polygenic diseases [2]. Third, it relies on one-variable-at-a-time experimentation, which cannot capture the simultaneous interactions of multiple genetic and environmental factors that drive polygenic disorders [14].

The fundamental disconnect emerges because polygenic neurological diseases operate through complex network dynamics rather than linear pathways. These networks exhibit properties such as robustness, redundancy, and distributed control that cannot be understood by studying individual elements in isolation [2]. As research has demonstrated, the brain's functional and genetic architecture represents a highly interconnected system where perturbations in one network region can produce distant, non-intuitive effects throughout the system [15].

Quantitative Evidence of Polygenicity in Neurological Disorders

Table 1: Empirical Evidence for Polygenic Architecture in Major Neurological Diseases

| Disease | Number of Associated Risk Loci | Heritability Explained by Common Variants | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease | >40 identified loci | 24-33% | APOE ε4 allele remains strongest genetic risk factor, but numerous other loci contribute modest effects [16] |

| Schizophrenia | >100 common variants | Approximately 23% | Highly polygenic with thousands of variants contributing to risk; PRS can partially predict case status [17] |

| Parkinson's Disease | ~90 identified risk loci | 16-36% | Combination of high-effect rare variants (LRRK2, GBA) with numerous common low-effect variants [18] |

The data presented in Table 1 illustrates the highly polygenic nature of major neurological disorders. For instance, schizophrenia research has revealed that genetic risk arises from "many hundreds or thousands of genetic variants," each typically accounting for only a small proportion of phenotypic variance [17]. This highly distributed genetic architecture fundamentally challenges the reductionist premise that studying individual elements in isolation can yield comprehensive disease understanding.

Specific Methodological Limitations in Experimental Design

Inadequate Genetic Risk Modeling

Traditional reductionist approaches typically focus on identifying single genetic mutations or variants with large effects, mirroring successful strategies for Mendelian disorders. However, this approach fails to adequately model the genetic risk for polygenic neurological diseases, which involves the cumulative burden of many risk alleles, each with small effect sizes [19].

Polygenic Risk Scores (PRS) have emerged as a powerful alternative that better captures this distributed genetic architecture. The PRS is calculated as follows:

Where βi is the effect size of the i-th genetic variant from genome-wide association studies (GWAS), and Gi is the number of risk alleles (0, 1, or 2) carried by an individual [17] [18]. This quantitative model stands in stark contrast to binary reductionist classifications (presence/absence of a mutation) and demonstrates superior predictive power for complex disorders.

Table 2: Comparison of Genetic Risk Assessment Methods

| Feature | Traditional Reductionist Approach | Polygenic Systems Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Single genetic mutations/variants with large effects | Multiple genetic variants with small effects |

| Disease Model | Mendelian disorders | Complex, multifactorial disorders |

| Risk Assessment | Binary (presence/absence of mutation) | Quantitative (cumulative risk score) |

| Analytical Framework | Single-marker association tests | Genome-wide aggregation methods |

Pathway and Network Analysis Deficiencies

Reductionist methods demonstrate significant limitations in identifying and analyzing biological pathways and networks central to polygenic neurological diseases. The single-target focus overlooks the complex network topology and interactome dynamics that characterize these disorders [2]. For example, network-based analyses of genes involved in hereditary ataxias have revealed novel pathogenic mechanisms related to RNA splicing that were not apparent when studying individual genes in isolation [2].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the systems biology approach that addresses these limitations:

Systems Biology Research Workflow

This integrated approach enables researchers to move beyond single-target thinking to understand system-wide perturbations. For instance, research on psychosis-spectrum psychopathology has revealed that "schizophrenia PRS are strongly related to the level of mood-incongruent psychotic symptoms in bipolar disorder" [17], demonstrating transdiagnostic genetic influences that reductionist models would miss.

Inability to Capture Temporal Dynamics and Emergent Properties

Polygenic neurological diseases typically unfold over decades, with complex temporal dynamics that reductionist snapshots cannot capture. The progression from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to Alzheimer's dementia, for instance, involves non-linear transitions and emergent pathological properties that cannot be predicted from isolated biomarker measurements [16].

Reductionist methods struggle to model the threshold effects and compensatory mechanisms that characterize disease progression. In Huntington's disease—a classic Mendelian disorder—age of onset is influenced by a polygenic architecture, with research identifying "21 associated loci, providing evidence of natural compensatory mechanisms" [19]. If even monogenic diseases exhibit polygenic modulation of expression, the limitations of single-target approaches for truly polygenic disorders become increasingly apparent.

Consequences for Therapeutic Development

High Failure Rates of Single-Target Therapies

The limitations of reductionist approaches have direct consequences for therapeutic development, manifesting most visibly in the high failure rates of single-target therapies for polygenic neurological diseases. Drug development campaigns based on isolated targets, such as amyloid-beta in Alzheimer's disease, have repeatedly failed to demonstrate clinical efficacy despite compelling reductionist evidence [16].

The fundamental issue lies in the network robustness of biological systems, where targeting a single node often triggers compensatory mechanisms through alternative pathways. Systems biology reveals that complex networks exhibit distributed functionality and redundancy that allow them to maintain function despite targeted interventions [2] [15]. This explains why "current therapies mainly aim to alleviate symptoms rather than target the underlying causes" of Alzheimer's disease [16].

Inadequate Biomarker Development

Reductionist approaches have similarly struggled to develop comprehensive biomarker panels for early detection, prognosis, and treatment response prediction in polygenic neurological diseases. Single biomarkers typically lack the sensitivity and specificity required for clinically useful applications in complex disorders.

The emerging paradigm of multi-omics integration offers a more promising approach. As research in Alzheimer's disease demonstrates, "integrating multi-omics data can transform our approach to AD research and treatment" by capturing the complex interactions between genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic factors [16]. This systems approach enables the development of biomarker signatures that better reflect disease complexity.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Systems Biology Approaches

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Polygenic Disease Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-wide Profiling | SNP microarrays, Whole-genome sequencing | Identification of risk variants across the entire genome [17] [19] |

| CRISPR-based Editing | CRISPR-Cas9, Base editing, Prime editing | Functional validation of risk loci and pathway analysis [20] |

| Multi-omics Platforms | Bulk and single-cell RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, Mass cytometry | Mapping molecular interactions across biological layers [16] |

| Computational Modeling | Ordinary differential equation models, Boolean networks, Agent-based models | Simulating system dynamics and predicting intervention effects [15] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | PRSice, LD Score Regression, MAGMA | Calculating polygenic risk scores and performing pathway analyses [17] [21] |

Systems Biology: An Integrative Framework Addressing Reductionist Limitations

Conceptual and Methodological Advancements

Systems biology provides a conceptual and methodological framework that directly addresses the limitations of reductionist approaches. Rather than studying components in isolation, it focuses on "integration of available molecular, physiological, and clinical information in the context of a quantitative framework typically used by engineers" [2]. This paradigm shift enables researchers to capture the emergent properties and network dynamics that characterize polygenic neurological diseases.

The methodological toolkit of systems biology includes:

- High-throughput data generation (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics)

- Computational modeling and simulation (ordinary differential equations, Boolean networks, agent-based models)

- Network analysis and visualization

- Data integration across multiple biological scales [15]

These methods enable a more comprehensive understanding of disease mechanisms, moving beyond single targets to study system-wide perturbations.

Applications in Neurological Disease Research

Systems biology approaches are already generating novel insights into polygenic neurological diseases. In Alzheimer's disease, multi-omics approaches are "transforming our understanding of AD pathogenesis" by integrating data from genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics [16]. Similarly, network-based analyses of hereditary ataxias have identified novel disease mechanisms and challenged traditional nosological categories [2].

The following diagram illustrates the multi-omics integration central to systems biology approaches:

Multi-Omics Integration in Systems Biology

This integrated approach enables the identification of "patient-specific therapeutic approaches, bringing the paradigm of personalized medicine one step closer to reality" [2]. For drug development professionals, this represents a crucial advancement beyond the limitations of single-target therapies.

Traditional reductionist methods face fundamental limitations in addressing the complexity of polygenic neurological diseases. Their component-isolation approach, linear causal assumptions, and single-target focus render them inadequate for capturing the emergent properties, network dynamics, and non-linear interactions that characterize these disorders. These methodological limitations have direct consequences for both understanding disease mechanisms and developing effective therapies, as evidenced by the high failure rate of single-target interventions.

Systems biology provides a powerful integrative framework that addresses these limitations through multi-omics integration, computational modeling, and network-based analyses. By studying systems as whole, interacting networks rather than collections of isolated components, this approach offers more comprehensive insights into disease pathogenesis and more promising avenues for therapeutic development. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working on polygenic neurological diseases, embracing these systems-level approaches is essential for advancing both basic understanding and clinical applications.

The study of complex neurological diseases has undergone a paradigm shift, moving from a reductionist focus on individual components to a holistic, systems-level approach. This transition has been powered by the convergence of two foundational fields: network theory, which provides the mathematical framework for understanding interconnected systems, and modern omics technologies, which supply the high-dimensional molecular data these systems describe. The integration of these disciplines within systems biology has created a powerful analytical platform for biomedical research, enabling the deconvolution of complex pathological states involving multi-layer modifications at genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolic levels in a global-unbiased fashion [22] [23].

The application of this integrated approach to neurological disorders is particularly compelling given their inherent complexity. These conditions are characterized by heterogeneous clinical presentation, non-cell autonomous nature, and diversity of cellular, subcellular, and molecular pathways [24]. Systems biology, with its foundation in network theory and omics technologies, offers a valuable platform for addressing these challenges by integrating and correlating different large datasets covering the transcriptome, epigenome, proteome, and metabolome associated with specific neurological conditions [24] [25]. This review traces the key historical milestones in the development of network theory and omics technologies, focusing on their synergistic application in unraveling the complexity of neurological diseases.

The Foundations of Network Theory

Historical Development and Core Principles

Network theory, also known as graph theory in mathematics, defines networks as graphs where vertices or edges possess attributes and analyzes these networks over symmetric or asymmetric relations between their discrete components [26]. The field traces its origins to Leonhard Euler's solution to the Seven Bridges of Königsberg problem in 1736, considered the first true proof in network theory [26]. This mathematical foundation lay dormant for centuries before experiencing explosive development and application across diverse scientific disciplines in recent decades.

Core concepts in network theory provide the analytical framework for studying complex systems [27]:

- Nodes and Edges: Nodes (vertices) represent individual entities, while edges (connections) represent relationships or interactions between them.

- Degree: The number of edges connected to a node, indicating its connectivity level.

- Centrality: Measures identifying the most important nodes based on various criteria like connections (degree centrality), position as bridges (betweenness centrality), or connection to other important nodes (eigenvector centrality).

- Clustering Coefficient: Quantifies the tendency of nodes to form clusters or communities.

- Scale-Free Networks: Characterized by a power-law degree distribution where few hubs have many connections while most nodes have few.

Expansion into Biological Applications

The application of network theory to biological systems represented a watershed moment in biomedical research. Biological networks are constructed from various data types, with nodes representing biological entities (genes, proteins, metabolites) and edges representing functional, physical, or regulatory interactions between them [25]. These networks can be built de novo from experimental interactions, applied to omics datasets using specialized software, or reverse-engineered from high-throughput data [25].

In neurological research, network-based analyses have demonstrated particular utility. For example, studies of hereditary ataxias using network approaches revealed novel pathways related to RNA splicing, uncovering a previously unrecognized pathogenic mechanism for these diseases [2]. Similarly, network analysis is challenging the current nosology of neurological diseases by revealing shared pathways across traditionally separate diagnostic categories [2].

The Evolution of Omics Technologies

Conceptual Foundation and Hierarchies

The term "omics" refers to fields in biology that end in -omics, such as genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, or metabolomics. Omics sciences involve probing and analyzing large datasets representing the structure and function of an entire makeup of a given biological system at a particular level [22] [23]. These approaches have substantially revolutionized methodologies for interrogating biological systems, enabling "top-down" strategies that complement traditional "bottom-up" approaches.

Omics technologies can be classified into distinct hierarchies that often follow the central dogma of molecular biology while extending beyond it [22] [23]:

- The "Four Big Omics": Genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics.

- Epiomics: Including epigenomics, epitranscriptomics, and epiproteomics, representing modifications beyond primary sequences.

- Interactomics: encompassing various interaction types between omics layers (DNA-RNA, RNA-RNA, DNA-protein, RNA-protein, protein-protein, protein-metabolite).

Table 1: Hierarchy of Major Omics Fields

| Category | Specific Omics | Definition | Primary Analytical Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Omics | Genomics | Study of the complete DNA sequence of an organism | Microarray, Sanger sequencing, NGS, TGS |

| Transcriptomics | Comprehensive analysis of RNA transcripts | RNA microarray, RNA-seq | |

| Proteomics | System-wide study of proteins and their functions | Mass spectrometry, protein arrays | |

| Metabolomics | Global study of small molecule metabolites | Mass spectrometry, NMR spectroscopy | |

| Epiomics | Epigenomics | Analysis of reversible DNA and histone modifications | Bisulfite sequencing, ChIP-seq |

| Epitranscriptomics | Study of RNA modifications | Sequencing-based approaches | |

| Epiproteomics | Investigation of post-translational protein modifications | Mass spectrometry | |

| Interactomics | Various | Analysis of interactions between different molecular classes | Sequencing, MS, hybrid methods |

Technological Milestones in Omics

The development of omics technologies has progressed through several revolutionary phases, each dramatically increasing our ability to interrogate biological systems comprehensively.

Genomics Technology Evolution: The first major high-throughput technology was the DNA microarray, established by Schena et al., where thousands of probes were fixed to a surface and samples labeled with fluorescent dyes for detection after hybridization [23]. This was followed by first-generation Sanger sequencing (invented in 1977), which enabled the completion of the Human Genome Project but suffered from low throughput and high cost [23].

The development of next-generation sequencing (NGS) dramatically improved sequencing speed and scalability through various approaches including cyclic-array sequencing, microelectrophoretic methods, sequencing by hybridization, and real-time observation of single molecules [23]. While NGS provided substantial improvements in throughput and cost, it generated short reads that limited the ability to capture structural variants, repetitive elements, and regions with extreme GC content [23].

The third-generation sequencing (TGS) platforms, including Pacific Biosciences (PacBio, 2011) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT, 2014), introduced single-molecule real-time sequencing with long reads, low alignment errors, and the ability to directly detect epigenetic modifications [22] [23].

Transcriptomics Technology Progression: Transcriptomics technologies evolved from RNA microarrays to tag-based methods (DGE seq, 3' end seq), probe alternative splicing and gene fusion approaches (SMRT, SLR-RNA-Seq), targeted RNA sequencing (target capture, amplicon sequencing), and single-cell RNA sequencing (CEL-seq2, Drop-seq) [22]. The advent of RNA sequencing (RNAseq) enabled direct sequencing of RNAs without predefined probes, capturing alternative splice variants, non-coding RNAs, and novel transcripts [28].

Proteomics Technology Advances: Proteomics technologies are primarily mass spectrometry (MS)-based, with key developments including:

- High-resolution MS: Orbitrap, MALDI-TOF-TOF, and FT-ICR platforms

- Low-resolution MS: Quadrupole and ion-trap instruments

- Tandem MS techniques: CID, ECD, ETD, and EID for fragmentation and PTM analysis [22]

Emerging approaches like selected reaction monitoring (SRM) proteomics and antibody-based protein identification have significantly advanced quantitative proteomic applications [28].

Metabolomics Technology Development: Metabolomics employs spectroscopy techniques including FT-IR spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and NMR spectroscopy, as well as mass spectrometry-based approaches [22]. Each platform offers different advantages in sensitivity, coverage, and quantitative accuracy.

Table 2: Historical Timeline of Major Omics Technology Milestones

| Time Period | Genomics | Transcriptomics | Proteomics | Metabolomics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970s-1990s | Sanger sequencing (1977) | Northern blotting | 2D gel electrophoresis | Basic chromatography |

| 1990s-2000s | DNA microarrays (1995) | RNA microarrays | MALDI-TOF, ESI-MS | GC-MS, LC-MS |

| 2000s-2010s | NGS platforms (454, Illumina, SOLiD) | RNA-seq | Orbitrap instruments | NMR-based platforms |

| 2010s-Present | Third-generation sequencing (PacBio, ONT) | Single-cell RNA-seq | SWATH-MS, SRM | Imaging mass spectrometry |

Integration: Network Theory Meets Omics in Neuroscience

Systems Biology Framework

Systems biology represents the formal integration of network theory with omics technologies, creating a powerful analytical framework for biomedical research. This approach employs tools developed in physics and mathematics such as nonlinear dynamics, control theory, and modeling of dynamic systems to integrate available molecular, physiological, and clinical information within a quantitative framework [2]. The fundamental premise is that biological systems function through complex, dynamic networks of interacting molecules rather than through isolated components acting independently [25].

The adoption of systems biology in neuroscience was driven by several enabling developments [25]:

- Vast genetic information from the Human Genome Project

- Interdisciplinary research creating new technologies and computational methodologies

- High-throughput platforms for integrating omics datasets

- Advanced networking infrastructure for data sharing and knowledge dissemination

This approach has proven particularly valuable for neurological disorders, which often involve multiple molecular pathways, cell types, and genetic and environmental factors [24] [29]. For example, in Alzheimer's disease research, cDNA microarray analyses have identified altered expression of genes involved in synaptic vesicle functioning, including synapsin II, providing insights into mechanisms underlying cognitive decline [29].

Analytical Workflow for Neurological Disorders

The standard analytical workflow for applying network theory to omics data in neurological research involves several key stages [25]:

Data Generation: High-throughput omics technologies produce comprehensive molecular profiles from neurological tissues or biofluids.

Network Construction: Biological networks are built with nodes representing molecules and edges representing interactions, using tools such as Cytoscape for visualization and analysis [25].

Topological Analysis: Network properties are quantified to identify hub genes, functional modules, and disrupted pathways.

Integration with Clinical Data: Molecular networks are correlated with phenotypic manifestations to establish clinical relevance.

Experimental Validation: Computational findings are tested in model systems to verify biological significance.

This workflow facilitates the identification of key drivers of disease pathogenesis, biomarker discovery, and potential therapeutic targets that might not be apparent from reductionist approaches.

Diagram 1: Systems Biology Workflow for Neurological Disorders. This diagram illustrates the iterative process of integrating omics data with network analysis in neurological disease research.

Applications in Neurological Disease Research

Alzheimer's Disease

Systems biology approaches have revealed novel insights into Alzheimer's disease (AD) pathogenesis. cDNA microarray analyses of postmortem brain tissues from patients with varying degrees of cognitive impairment identified 32 cDNAs with significantly altered expression in moderate dementia compared to normal controls [29]. Among these, synapsin II—a gene involved in synaptic vesicle metabolism and neurotransmitter release—was significantly downregulated, suggesting a mechanism for synaptic dysfunction in AD [29].

Proteomic approaches have identified candidate biomarkers for tracking disease progression from normal cognition to mild cognitive impairment and AD [29]. These include proteins involved in amyloid beta metabolism, tau pathology, neuroinflammation, and synaptic function. The integration of these multi-omics datasets through network analysis has revealed key hub proteins and functional modules that drive disease progression, offering potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Other Disorders

In amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), systems biology has helped disentangle the heterogeneity of clinical presentations and identify molecular subtypes with potential therapeutic implications [24]. Network-based analysis of genes involved in hereditary ataxias demonstrated pathways related to RNA splicing as a novel pathogenic mechanism [2]. Similar approaches have been applied to Parkinson's disease, peripheral neuropathies, and other neurological conditions, revealing shared and distinct network perturbations across different disorders.

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications

The integration of network theory with omics technologies has enabled several clinically relevant applications:

- Biomarker Discovery: Identification of early diagnostic biomarkers for conditions like AD that have long subclinical phases [24] [29].

- Drug Target Identification: Network-based approaches reveal hub proteins and pathways that represent promising therapeutic targets.

- Exposome Characterization: Defining collections of environmental toxicants that increase risk of certain neurological diseases [24].

- Personalized Medicine: Patient-specific network analyses may guide tailored therapeutic approaches [2].

Experimental Protocols and Research Tools

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Omics Network Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| cDNA Microarrays | Simultaneous quantification of thousands of transcripts | Gene expression profiling in Alzheimer's brain tissues [29] |

| RNA-seq Kits | Library preparation for transcriptome sequencing | Detection of novel transcripts, alternative splicing, non-coding RNAs [28] |

| Mass Spectrometry Reagents | Protein digestion, labeling, fractionation | Proteomic analysis of neurodegenerative tissues [22] [29] |

| Antibody Arrays | Multiplexed protein detection and quantification | Biomarker verification in biofluids [28] |

| SNP Chips | Genotyping of known sequence variants | Genome-wide association studies in neurological disorders [28] |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | Detection of methylated cytosines | Epigenomic studies in neurological disease models [28] |

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Protocol 1: Network-Based Analysis of Transcriptomic Data from Neurological Tissues

This protocol outlines the key steps for applying network theory to transcriptomic data from neurological tissues, based on methodologies successfully used in Alzheimer's disease research [29] [25].

Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction:

- Obtain postmortem brain tissues from well-characterized donors with documented neurological status.

- Homogenize tissue in TRIzol reagent and extract total RNA following manufacturer's protocol.

- Assess RNA quality using Bioanalyzer or similar instrumentation (RIN >7.0 required).

- Convert RNA to cDNA using reverse transcriptase with fluorescent labeling for microarray or prepare sequencing libraries for RNA-seq.

Transcriptomic Profiling: For microarray analysis:

- Hybridize labeled cDNA to high-density oligonucleotide arrays (e.g., Affymetrix GeneChip).

- Scan arrays using appropriate laser scanners and extract raw intensity values. For RNA sequencing:

- Prepare sequencing libraries using TruSeq or similar kits.

- Sequence on Illumina or other NGS platforms to minimum depth of 30 million reads per sample.

- Align reads to reference genome using STAR or HISAT2 aligners.

- Quantify gene-level counts using featureCounts or similar tools.

Data Preprocessing and Normalization:

- Perform quality control assessment (PCA, sample clustering, outlier detection).

- Normalize data using RMA (microarrays) or TMM/DESeq2 (RNA-seq) methods.

- Filter lowly expressed genes (minimum count >10 in at least 10% of samples).

- Batch correct using ComBat or similar algorithms if needed.

Differential Expression Analysis:

- Identify significantly differentially expressed genes using linear models (limma) for microarrays or negative binomial models (DESeq2) for RNA-seq.

- Apply multiple testing correction (Benjamini-Hochberg FDR <0.05).

- Generate lists of significantly upregulated and downregulated genes for network analysis.

Network Construction and Analysis:

- Import gene lists into network analysis tools (Cytoscape, iCTNet).

- Build protein-protein interaction networks using databases (STRING, BioGRID).

- Calculate network topology metrics (degree, betweenness centrality, clustering coefficient).

- Identify functional modules using community detection algorithms (MCODE, GLay).

- Annotate networks with functional information (GO, KEGG pathways).

Integration and Validation:

- Correlate network features with clinical and neuropathological data.

- Validate key findings using orthogonal methods (qPCR, immunohistochemistry).

- Perform functional validation in model systems (cell culture, animal models).

Diagram 2: Network Analysis Workflow for Transcriptomic Data. This diagram outlines the key experimental and computational steps in applying network theory to transcriptomic data from neurological tissues.

Future Perspectives and Emerging Trends

The integration of network theory with omics technologies continues to evolve, with several emerging trends shaping future applications in neurological disease research. Single-cell omics approaches are revealing cellular heterogeneity within neurological tissues at unprecedented resolution, enabling the construction of cell-type-specific networks in healthy and diseased states [22] [23]. Spatial omics technologies preserve architectural context while providing molecular profiling, allowing network analysis within tissue microenvironments. Multi-omics integration methods are becoming increasingly sophisticated, enabling simultaneous analysis of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data within unified network frameworks [24] [25].

Emerging omics fields continue to expand the analytical toolbox. Redoxomics—the systematic study of redox modifications—has been identified as a promising new omics layer that views cell decision-making toward physiological or pathological states as a fine-tuned redox balance [22] [23]. Microbiomics explores how resident microorganisms influence neurological function and disease through the gut-brain axis [28]. Exposomics aims to comprehensively characterize environmental exposures throughout the lifespan and their relationship to neurological disease risk [24].

From a technological perspective, long-read sequencing, advanced mass spectrometry, and multiplexed imaging continue to enhance the depth and precision of omics measurements. Concurrently, artificial intelligence and machine learning are revolutionizing network analysis, enabling more accurate predictions of network behavior under different genetic and environmental perturbations. These advances promise to accelerate the translation of systems-level insights into improved diagnostics and therapeutics for neurological disorders, ultimately realizing the goal of personalized medicine in neurology [2] [24] [25].

Multi-Omic Integration and Computational Modeling for Deciphering Disease Mechanisms

The complexity of the human brain and its diseases has long presented a formidable challenge to biomedical research. Traditional approaches, which often focus on single molecules or linear pathways, have proven insufficient for unraveling the multifaceted nature of neurological disorders. In this context, systems biology has emerged as a transformative framework, enabling researchers to study the nervous system as an integrated network of molecular interactions. By leveraging large-scale datasets, systems biology provides a valuable platform for addressing the challenges of studying heterogeneous neurological diseases, which are characterized by diverse cellular, subcellular, and molecular pathways [24].

The multi-omics toolkit—encompassing genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—represents the methodological cornerstone of this systems-level approach. When applied to neuroscience, these technologies enable a comprehensive analysis of biological data across diverse cell types and processes, offering unprecedented insights into disease mechanisms. This integration is particularly powerful for disentangling the heterogeneity and complexity of neurological conditions, which often share characteristics such as non-cell autonomous nature and diversity of pathological pathways [24] [16]. The application of multi-omics in neuroscience extends beyond basic research, showing tremendous promise for uncovering novel therapeutic targets, identifying early diagnostic biomarkers, and ultimately paving the way for precision medicine approaches to brain disorders [30] [24].

Core Omics Technologies: Methodologies and Applications

Genomics and Epigenomics

Genomics in neuroscience focuses on the identification of DNA sequence variations and epigenetic modifications that influence brain function and disease susceptibility. Methodologically, next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies enable comprehensive genome-wide association studies (GWAS), whole-exome sequencing, and whole-genome sequencing to identify genetic risk factors. For epigenomics, techniques such as bisulfite sequencing (for DNA methylation), chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq for histone modifications), and ATAC-seq (for chromatin accessibility) provide insights into regulatory mechanisms that influence gene expression without altering the DNA sequence itself [16].

In Alzheimer's disease (AD) research, genomic studies have identified key risk genes including APOE, TREM2, and APP, with the APOE ε4 allele representing the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset AD [16]. Epigenomic investigations have revealed age-related and disease-specific DNA methylation patterns that influence the expression of genes involved in amyloid processing and neuroinflammation. The standard protocol for bisulfite sequencing involves: (1) DNA extraction from brain tissue or blood samples; (2) bisulfite conversion of unmethylated cytosines to uracils; (3) PCR amplification and sequencing; (4) alignment to reference genome and methylation calling [16]. These genomic and epigenomic markers provide critical insights into individual susceptibility and potential avenues for early intervention.

Transcriptomics

Transcriptomics technologies profile gene expression patterns at the RNA level, providing insights into the functional elements of the genome in neurological contexts. Bulk RNA sequencing offers an average expression profile across cell populations, while single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) enables resolution at the individual cell level, revealing cellular heterogeneity in the nervous system. Spatial transcriptomics has emerged as a cutting-edge extension that maps gene expression within the context of tissue architecture, preserving crucial spatial information that is particularly valuable for understanding the organized structure of brain regions [31] [16].

The analytical workflow for scRNA-seq typically includes: (1) tissue dissociation and single-cell suspension preparation; (2) cell barcoding and library preparation using platforms such as 10X Chromium or BD Rhapsody; (3) sequencing; (4) quality control, normalization, and clustering analysis using tools such as Seurat or Scanpy; (5) cell type identification and differential expression analysis [32]. In Parkinson's disease research, transcriptomic analyses have revealed dysregulation in pathways related to mitochondrial function, protein degradation, and neuroinflammation. Spatial transcriptomics tools like SOAPy further enable the identification of spatial domains, expression tendencies, and cellular co-localization patterns in brain tissues, providing deeper insights into the microenvironmental changes associated with neurodegeneration [31].

Proteomics