Systems Biology in Biomedical Research: From Molecular Networks to Precision Medicine

This article explores the transformative role of systems biology in modern biomedical research and drug development.

Systems Biology in Biomedical Research: From Molecular Networks to Precision Medicine

Abstract

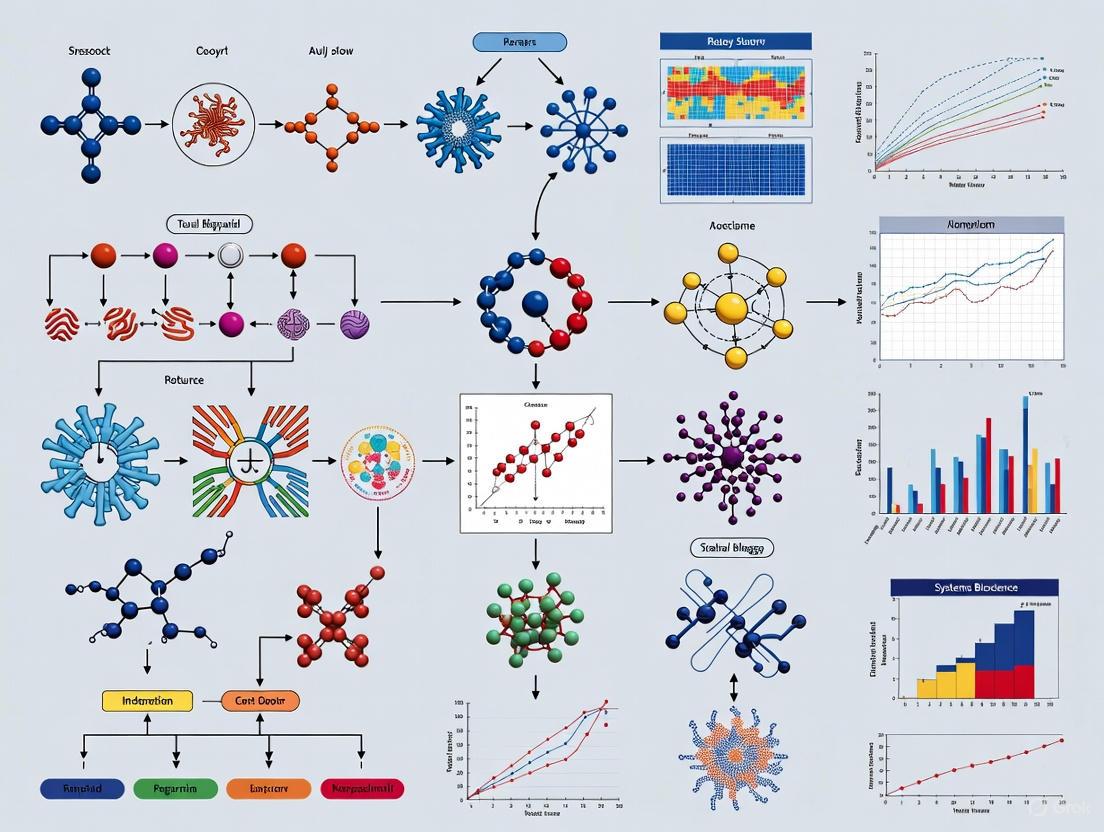

This article explores the transformative role of systems biology in modern biomedical research and drug development. Moving beyond traditional reductionist approaches, systems biology employs computational and mathematical modeling to understand complex biological systems as integrated wholes. We examine its foundational principles, key methodologies like multi-omics integration and network analysis, and its application in addressing research bottlenecks. The content covers how this approach enhances drug target validation, improves clinical trial design, and facilitates the development of personalized therapeutic strategies for complex diseases, ultimately bridging the gap between molecular discoveries and clinical applications.

From Reductionism to Holism: Core Principles of Systems Biology

Systems biology represents a fundamental shift in biological research, moving from the study of individual components to understanding how networks of biological systems work together to achieve complex functions [1]. It is a multi-scale field with no fixed biological scale, focusing instead on the concerted actions of an ensemble of proteins, cofactors, and small molecules to achieve biological responses or cascades [1]. This approach recognizes that biological function emerges from the interactions between system components rather than from isolated elements, providing a holistic framework for deciphering the mechanisms underlying multifactorial diseases and addressing fundamental biological questions [1].

The core premise of systems biology lies in understanding intricate interconnectedness and interactions of biological components within living organisms [2]. This perspective has proven crucial in advancing diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities in biomedical research and precision healthcare by providing profound insights into complex biological processes and networks [2]. Through systems biology principles, researchers can develop targeted, data-driven strategies for personalized medicine, refine current technologies to improve clinical outcomes, and expand access to advanced therapies [2].

Mathematical Frameworks and Computational Approaches

Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) Models

Mathematical modeling using ordinary differential equations has emerged as a powerful tool for elucidating the dynamics of complex biological systems [1]. ODEs can generate predictive models of biological processes involving metabolic pathways, protein-protein interactions, and other network dynamics. In defining a biological network quantitatively, ODE models enable predictions of concentrations, kinetics, and behavior of network components, building testable hypotheses on disease causation, progression, and interference [1].

The general ODE representation for biological systems can be expressed as:

Where variable Cᵢ represents the concentration of an individual biological component, xᵢ denotes the number of biochemical reactions associated with component Cᵢ for the yth reaction, σᵢⱼ represents stoichiometric coefficients, and fⱼ is a function that describes how the concentration Cᵢ changes with the biochemical reactions of the reactants/products and parameters within the given timeframe [1].

Table 1: Key Components of Systems Biology ODE Models

| Component | Symbol | Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| State Variable | Cᵢ | Concentration of biological species | Protein concentration, metabolite levels |

| Stoichiometric Matrix | σᵢⱼ | Quantitative relationships in reactions | Network connectivity and flux balance |

| Kinetic Function | fⱼ | Mathematical description of reaction rates | Michaelis-Menten, Hill equations |

| Parameters | k | Kinetic constants, binding affinities | Estimated from experimental data |

Multi-Scale Modeling Integration

The multi-scale nature of systems biology necessitates integrated approaches that bridge system-scale cellular responses to the molecular-scale dynamics of individual macromolecules [1]. When kinetic parameters are unknown, multi-scale computational techniques can predict association rate constants and other critical parameters. These include:

- Brownian Dynamics (BD): Simulates system dynamics based on an overdamped Langevin equation of motion, enabling the study of diffusion dynamics and obtaining association rates [1]

- Molecular Dynamics (MD): Follows the motions of macromolecules over time by integrating Newton's equations of motion [1]

- Hybrid Schemes (e.g., SEEKR): Combines multiscale approaches of MD, BD, and milestoning to estimate kinetic parameters of association and dissociation rate constants [1]

Parameter Identification Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Data

Unified Optimization Framework

A significant advancement in systems biology parameter identification involves combining both qualitative and quantitative data within a single estimation procedure [3]. This approach formalizes qualitative biological observations as inequality constraints on model outputs, complementing traditional quantitative data points. The method constructs a unified scalar objective function:

Where x represents the vector of unknown model parameters, f𝔮𝔲𝔞𝔫ₜ(x) is the standard sum of squares over all quantitative data points, and f𝔮𝔲𝔞𝔩(x) encodes the qualitative data constraints [3].

The quantitative component follows the traditional least-squares formulation:

The qualitative component transforms each qualitative observation into an inequality constraint of the form gᵢ(x) < 0 and applies penalties for constraint violations:

Where Cᵢ are problem-specific constants that determine the penalty strength for each constraint violation [3].

Experimental Protocol: Parameter Identification Workflow

The following DOT visualization illustrates the integrated parameter identification process combining both data types:

Figure 1: Parameter identification workflow combining qualitative and quantitative data.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Data Collection and Preparation

- Quantitative Data: Gather numerical measurements (time courses, dose-response curves, concentration measurements)

- Qualitative Data: Collect categorical observations (phenotypic characterizations, viability assessments, relative comparisons)

Constraint Formulation

- Convert qualitative observations into mathematical inequality constraints

- Define appropriate penalty constants (Cᵢ) for each constraint type

Objective Function Construction

- Combine quantitative sum-of-squares with qualitative penalty terms

- Weight components appropriately based on data reliability and importance

Parameter Estimation

- Apply optimization algorithms (differential evolution, scatter search)

- Implement constrained optimization techniques to handle parameter boundaries

Model Validation and Refinement

- Assess parameter identifiability using profile likelihood approaches

- Validate model predictions against held-out experimental data

- Refine constraints and objective function as needed [3]

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Systems Biology Modeling

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| BioModels Database | Repository of computational models | Model sharing and validation |

| Compstatin | C3 complement inhibitor | Therapeutic intervention studies |

| Eculizumab | C5 complement inhibitor | Late-stage complement regulation |

| MODELLER/SWISS-MODEL | Homology modeling tools | Structural data supplementation |

| JUNG Framework | Network visualization and analysis | Interactive pathway mapping |

Case Study: The Complement System in Immunity and Disease

Systems Biology of Immune Response

The complement system represents an ideal case study for systems biology approaches, comprising an intricate network of more than 60 proteins that circulate in plasma and bind to cellular membranes [1]. This system functions as an effector arm of immunity, eliminating pathogens, maintaining host homeostasis, and bridging innate and adaptive immunity [1]. The complexity arises from mechanistic functions of numerous proteins and biochemical reactions within complement pathways, creating multi-phasic interactions between fluid and solid phases of immunity [1].

Complement dysfunction manifests in severe diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders (Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases), multiple sclerosis, renal diseases, and susceptibility to severe infections [1]. Understanding the network interactions mediating these systems is crucial for deciphering disease mechanisms and developing therapeutic strategies [1].

Pathway Modeling and Visualization

The complement system operates through three major pathways - alternative, classical, and lectin - that work in concert to achieve immune function [1]. The following DOT visualization represents the core complement pathway and its regulatory mechanisms:

Figure 2: Complement system pathway integration and regulation.

Therapeutic Applications and Personalized Medicine

Systems biology models of the complement system enable patient-specific modeling by incorporating individual clinical data. For instance, disorders like C3 glomerulonephritis and dense-deposit disease associated with factor H (FH) mutations can be modeled by reparameterizing starting FH concentrations in ODE models [1]. This approach predicts how specific mutations affect activation and regulation of the alternative pathway, demonstrating the power of systems biology in personalized medicine.

These models also facilitate therapeutic target identification through global and local sensitivity analyses [1]. Global sensitivity identifies critical kinetic parameters in the network, while local sensitivity pinpoints complement components that mediate activation or regulation outputs [1]. For known inhibitors like compstatin (C3 inhibitor) and eculizumab (C5 inhibitor), ODE models can compare therapeutic performance under disease-based perturbations, enabling patient-tailored therapies depending on how disease-associated mutations manifest in the complement cascade [1].

Advanced Applications in Biomedical Innovation

Current Research Frontiers

Systems biology approaches are expanding into multiple biomedical innovation areas, leveraging tools such as biological standard parts, synthetic gene networks, and bio circuitry to model, test, design, and synthesize within biological systems [2]. Current research themes include:

- Diagnostic innovations informed by systems-level understanding and gene network analysis

- Therapeutic strategies including gene therapy, RNA-based interventions, and microbiome engineering

- Foundational research in DNA assembly, biosafety, and synthetic modeling of cellular systems

- Biomanufacturing of pharmaceuticals and biomedical tools with focus on scalability and efficiency

- Chronic disease understanding through systems biology approaches to rare disorders and individualized medicine [2]

Multi-Scale Integration Challenges and Solutions

A significant challenge in comprehensive systems biology modeling involves parameter uncertainty, exemplified by current efforts to build complete complement models encompassing all three pathways, immunoglobulins, and pentraxins [1]. Such a system may comprise 670 differential equations with 328 kinetic parameters, of which approximately 140 are typically unknown due to limited experimental data [1]. This parameter gap necessitates the multi-scale approaches discussed in Section 2.2 to predict unknown parameters through computational simulations.

Table 3: Multi-Scale Modeling Techniques in Systems Biology

| Technique | Scale | Application | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Atomic | Molecular motions | Conformational dynamics |

| Brownian Dynamics (BD) | Molecular | Diffusion-limited reactions | Association rate constants |

| Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) | Cellular | Pathway dynamics | Concentration time courses |

| Hybrid Schemes (e.g., SEEKR) | Multi-scale | Binding processes | Association/dissociation rates |

Systems biology provides an essential holistic framework for understanding complex biological systems by integrating mathematical modeling, computational analysis, and experimental data across multiple scales. Through approaches that combine qualitative and quantitative data, multi-scale modeling, and pathway analysis, systems biology enables unprecedented insights into biological network behavior, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic development. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they promise to advance biomedical innovation through improved diagnostic capabilities, personalized therapeutic strategies, and foundational insights into biological complexity.

The trajectory of modern biomedical research has been fundamentally shaped by the dynamic tension between two competing philosophical paradigms: reductionism and holism. Reductionism, which breaks complex systems down to their constituent parts to understand function, has long been the dominant approach in molecular biology [4]. In contrast, holism contends that "the whole is more than the sum of its parts," emphasizing emergent properties that arise from system interactions [4]. The emergence of systems biology represents a transformative synthesis of these approaches, leveraging computational integration and modeling to study biological complexity at multiple scales simultaneously [5]. This paradigm synthesis is particularly relevant for biomedical researchers and drug development professionals seeking to translate basic biological knowledge into therapeutic innovations.

Within contemporary research, these philosophical approaches are no longer mutually exclusive but rather complementary. As one analysis notes, "Molecular biology and systems biology are actually interdependent and complementary ways in which to study and make sense of complex phenomena" [4]. This integration has catalyzed the development of systems medicine, defined as "an approach seeking to improve medical research and health care through stratification by means of Systems Biology" [6], which applies these integrated approaches to address complex challenges in biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Philosophical Foundations and Historical Development

Reductionist Dominance in Molecular Biology

Reductionism as a methodological approach can be traced back to Bacon and Descartes, the latter of whom suggested that one should "divide each difficulty into as many parts as is feasible and necessary to resolve it" [4]. This philosophical framework achieved remarkable success throughout the latter half of the 20th century, becoming the epistemological foundation of molecular biology. The reductionist approach enabled monumental scientific achievements, including the demonstration that DNA alone was responsible for bacterial transformation [4] and the self-assembly experiments with tobacco mosaic virus [4].

Methodological reductionism operates on the principle that complex systems are best understood by analyzing their simpler components, isolating variables, and establishing clear cause-effect relationships [4]. This approach remains indispensable for mechanistic understanding and continues to underpin most pharmaceutical research and development. The profound success of reductionism established it as the default approach for investigating biological systems, though as noted in contemporary analysis, "Few scientists will voluntarily characterize their work as reductionistic" despite its pervasive influence [4].

Holistic Resurgence and Systems Thinking

Holistic perspectives in biology have equally deep historical roots, extending back to Aristotle's observation that "the whole is more than the sum of its parts" [4]. The term "holism" was formally coined by Smuts as "a tendency in nature to form wholes that are greater than the sum of the parts through creative evolution" [4]. In the early 20th century, Gestalt psychology provided the first major scientific challenge to reductionism, demonstrating that perception could not be understood by analyzing individual components alone [7].

The last decade has witnessed a significant backlash against the limitations of pure reductionism, with systems biology emerging as "a revolutionary alternative to molecular biology and a means to transcend its inherent reductionism" [4]. This shift recognizes that biological function often emerges from complex interactions within networks rather than from the properties of isolated components. The limitations of studying isolated components became increasingly apparent when in vitro observations failed to translate to whole-organism physiology [4], highlighting the critical importance of context in biological systems.

Table 1: Key Historical Developments in Biological Paradigms

| Time Period | Reductionist Milestones | Holist Milestones |

|---|---|---|

| 17th Century | Descartes' analytical method | - |

| 19th Century | - | Smuts coins "holism" |

| Early 20th Century | Rise of behaviorism | Gestalt psychology movement |

| Mid 20th Century | Molecular biology revolution | Systems theory development |

| Late 20th Century | Genetic engineering advances | Complex systems theory |

| Early 21st Century | Human Genome Project completion | Systems biology emergence |

The Paradigm Synthesis

The recognition that reductionism and holism represent complementary rather than opposing approaches has catalyzed their integration in contemporary biomedical research. This synthesis acknowledges that while reductionism provides essential mechanistic insights, holism offers crucial contextual understanding of system behavior [4]. The interdependence of these approaches is now evident across multiple research domains, from basic cellular biology to clinical translation.

This philosophical integration enables researchers to navigate what Steven Rose termed the "hierarchy of explanations," where the same biological phenomenon can be examined at multiple levels from molecular to social [7]. The synthetic paradigm recognizes that explanations at different levels provide distinct but equally valuable insights, and that comprehensive understanding requires integration across these explanatory levels rather than reduction to any single level.

Methodological Approaches and Techniques

Reductionist Methodologies in Practice

Reductionist approaches employ highly controlled experimentation to isolate causal relationships. The fundamental principle involves breaking down complex systems into constituent elements and studying these components in isolation. In biomedical research, this typically manifests as:

Targeted Molecular Investigations that examine specific genes, proteins, or metabolic pathways using techniques like PCR, Western blotting, and enzyme assays. These approaches enable precise mechanistic understanding but may overlook systemic interactions [4]. For example, studying cholera toxin gene expression using reporter fusions in isolated systems allows identification of regulatory mechanisms without the confounding variables present in whole organisms [4].

Controlled Laboratory Experiments that maintain strict environmental conditions to isolate variable effects. This experimental reductionism prioritizes internal validity, exemplified by studies examining sleep deprivation effects on memory through controlled laboratory testing [7]. While this approach establishes clear causality, it may sacrifice ecological validity.

Genetic Manipulation Techniques including knockout models and RNA interference that probe gene function by observing phenotypic consequences of specific genetic alterations. These methods have successfully identified functions of numerous genes but may be complicated by compensatory mechanisms and pleiotropic effects in intact organisms.

Table 2: Characteristic Methodologies of Each Paradigm

| Methodological Aspect | Reductionist Approach | Holistic/Systems Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Individual components | System interactions and networks |

| Experimental Design | Controlled, isolated variables | Natural, contextual studies |

| Data Type | Quantitative, precise measurements | High-dimensional, integrated data |

| Analysis Method | Statistical hypothesis testing | Multivariate, computational modeling |

| Key Strengths | Mechanistic clarity, causal inference | Contextual understanding, emergent properties |

| Inherent Limitations | May miss system-level interactions | Complexity can obscure mechanistic insights |

Systems Biology Methodologies

Systems biology employs both bottom-up and top-down approaches to study biological complexity. The bottom-up approach initiates from large-scale omics datasets (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) and uses mathematical modeling to reconstruct relationships between molecular components [5]. This data-driven approach typically employs network modeling where nodes represent molecular entities and edges represent their interactions [5].

Conversely, the top-down approach begins with hypotheses about system behavior and uses mathematical modeling to study small-scale molecular interactions [5]. This hypothesis-driven approach often employs dynamical modeling through ordinary differential equations (ODEs) and partial differential equations (PDEs) that mimic biological kinetics [5]. The "middle-out" or rational approach integrates both methodologies, balancing data-driven discovery with hypothesis testing [5].

The development of accurate dynamical models involves four key phases: (1) model design to identify core molecular interactions, (2) model construction translating interactions into representative equations, (3) model calibration fine-tuning mathematical parameters, and (4) model validation through experimental testing of predictions [5].

Integrated Experimental Workflows

Contemporary biomedical research increasingly employs integrated workflows that combine reductionist and systems approaches. These workflows typically begin with systems-level observations that generate hypotheses, proceed to reductionist experimentation for mechanistic validation, and culminate in systems-level integration to contextualize findings.

Applications in Biomedical Research and Therapeutics

Systems Medicine and Personalized Therapeutics

The integration of holistic and reductionist paradigms has catalyzed the emergence of systems medicine, which applies systems biology approaches to medical research and health care [6]. Systems medicine focuses on "the perturbations of overall pathway kinetics for the consequent onset and/or deterioration of the investigated condition/s" [5], enabling identification of novel diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets through integrative analysis.

This approach has demonstrated significant promise in oncology, particularly in neuroblastoma research. Logan et al. constructed a regulatory network model for the MYCN oncogene and evaluated its perturbation through retinoid drugs, providing enhanced insight into tumor responses to therapy and identifying novel molecular interaction hypotheses [5]. Similarly, research on chronic myeloid leukemia has employed systems-based protein regulatory networks to understand microRNA effects on BCR-ABL oncoprotein expression and phosphorylation [5].

The application of systems approaches extends to infectious disease research, where Sarmady et al. applied motif discovery algorithms to HIV viral protein sequences and their human host binding partners, identifying the Nef protein as a central hub interacting with multiple host proteins including MAPK1, VAV1, and LCK [5]. These network-based insights reveal potential therapeutic targets for disrupting viral pathogenesis.

Drug Discovery and Development

The drug development process exemplifies the complementary relationship between holistic and reductionist approaches. Reductionist methods enable high-throughput screening of compound libraries against specific molecular targets, establishing clear structure-activity relationships and mechanism of action. However, the frequent failure of compounds identified through purely reductionist methods in clinical trials underscores the limitations of this approach.

Systems pharmacology has emerged as an integrative framework that incorporates network analysis and multi-scale modeling to understand drug effects at the system level. This approach recognizes that therapeutic efficacy and toxicity emerge from interactions between drug compounds and complex biological networks rather than single targets in isolation.

The iGEM project from team McGill 2023 exemplifies this integrated approach, developing "a programmable and modular oncogene targeting and pyroptosis inducing system, utilizing Craspase, a CRISPR RNA-guided, RNA activated protease" [8]. Such synthetic biology approaches combine precise molecular targeting (reductionist) with system-level therapeutic design (holistic).

Table 3: Therapeutic Applications of Each Paradigm

| Therapeutic Area | Reductionist Contributions | Holistic/Systems Contributions |

|---|---|---|

| Neuropsychiatry | Psychopharmacology targeting specific neurotransmitter systems | Network analysis of brain region interactions |

| Oncology | Targeted therapies against specific oncoproteins | Pathway modeling of tumor microenvironment |

| Infectious Disease | Antimicrobials targeting specific pathogen components | Host-pathogen interaction networks |

| Metabolic Disease | Hormone replacement therapies | Whole-body metabolic network models |

| Autoimmune Conditions | Monoclonal antibodies against specific cytokines | Immune system network dysregulation models |

Diagnostic Innovation

Systems approaches are revolutionizing diagnostic medicine through the development of integrative biomarkers that capture system-level perturbations rather than isolated abnormalities. The iGEM UGM-Indonesia team exemplified this approach by developing "a novel Colorectal Cancer (CRC) screening biodevice, utilizing the Loop-Initiated RNA Activator (LIRA)" [8], representing a diagnostic innovation enabled by systems thinking.

Similarly, advanced computational tools enable the identification of disease signatures from multi-omics data, moving beyond single biomarker approaches to develop multivariate diagnostic classifiers with enhanced sensitivity and specificity. These classifiers capture the emergent properties of disease states that cannot be detected through reductionist analysis of individual biomarkers.

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

The integration of holistic and reductionist approaches requires specialized research tools that enable both precise molecular manipulations and system-level analyses. The following research reagents and platforms form the foundation of contemporary biomedical research spanning both paradigms.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Paradigm Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Omics Technologies | Next-generation sequencing, mass spectrometry, microarrays | Comprehensive molecular profiling | Holistic/Systems |

| Pathway Modulation Tools | CRISPR/Cas9, RNAi/siRNA, small molecule inhibitors | Precise manipulation of specific pathways | Reductionist |

| Computational Platforms | Network analysis software, dynamical modeling environments | System-level data integration and simulation | Holistic/Systems |

| Biosensors & Reporters | Fluorescent proteins, luciferase reporters, FRET biosensors | Real-time monitoring of molecular activities | Both |

| Model Systems | Cell lines, organoids, animal models, synthetic biological systems | Contextual investigation of biological mechanisms | Both |

The historical evolution of biological paradigms reveals a progressive integration of reductionist and holistic perspectives, culminating in the emergence of systems biology and systems medicine as synthetic frameworks. This integration represents not merely a compromise between opposing philosophies but a fundamental advancement in scientific approach that leverages the strengths of both perspectives while mitigating their respective limitations.

Future directions in biomedical research will likely focus on several key areas: First, the continued development of multi-scale modeling approaches that seamlessly integrate molecular, cellular, tissue, and organism-level data. Second, the refinement of personalized therapeutic strategies through systems medicine approaches that account for individual variations in biological networks. Third, the application of these integrated paradigms to previously intractable biomedical challenges, including complex chronic diseases and treatment-resistant conditions.

The synthesis of reductionist and holistic paradigms through systems biology represents a powerful framework for addressing the complex challenges facing biomedical researchers and drug development professionals. By embracing the complementary strengths of both approaches, the biomedical research community can accelerate the translation of scientific discoveries into clinical applications that improve human health. As the field continues to evolve, this integrated perspective will undoubtedly yield novel insights into biological complexity and innovative therapeutic strategies that leverage our growing understanding of system-level properties in health and disease.

Systems biology represents a fundamental shift in biomedical research, moving from a reductionist study of individual components to a holistic exploration of complex biological systems. This approach is characterized by three foundational concepts: emergent properties, which are novel behaviors and functions that arise from the interactions of simpler components; networks, which provide the architectural blueprint for these interactions; and multi-scale integration, which connects phenomena across different levels of biological organization, from molecules to organisms. The integration of these concepts is revolutionizing drug discovery and biomedical research by providing a more comprehensive framework for understanding disease mechanisms, predicting drug effects, and developing novel therapeutic strategies. By framing biological complexity as an integrative system rather than a collection of isolated parts, researchers can now tackle previously intractable challenges in human health and disease [9] [10] [11].

Foundational Concept 1: Emergent Properties

Theoretical Framework and Definitions

Emergent properties represent a core phenomenon in complex systems where the collective behavior of interacting components produces novel characteristics not present in, predictable from, or reducible to the individual parts alone. In biological systems, emergence manifests through spontaneous development of complex and organized patterns at macroscopic levels, driven by local interactions or individual rules within a system. The principle of "the whole is greater than the sum of its parts" finds its literal truth in emergent biological phenomena, where interactions between components generate unexpected complexity and functionality [12] [13].

This concept challenges traditional reductionist approaches in biology by demonstrating that complete understanding of individual components cannot fully explain system-level behaviors. As Professor Michael Levin's research on biological intelligence and morphogenesis illustrates, even non-neural cells can use bioelectric cues to coordinate decision-making and pattern formation, enabling tissues to know where to grow, what to become, and when to regenerate—functions that emerge only at the tissue level of organization [12].

Experimental Evidence and Biological Examples

Table 1: Representative Examples of Emergent Properties in Biological Systems

| Biological Scale | System Components | Emergent Property | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellular | Individual neurons | Consciousness, cognition, memory | Neural networks in the brain [12] |

| Organismal | Muscle, nerve, connective tissues | Rhythmic blood pumping | Heart organ function [12] |

| Synthetic Biological | Frog skin cells (Xenopus) | Locomotion, problem-solving, self-repair | Xenobots (engineered living organisms) [12] |

| Social Insects | Individual ants with simple behavioral rules | Complex nest construction, optimized foraging | Ant colony intelligence [12] |

| Multi-Agent Systems | Autonomous agents in grid world | Cooperative capture strategies | Pursuit-evasion games [13] |

The experimental evidence for emergent properties spans both natural biological systems and engineered models. In neural systems, individual neurons merely transmit electrical impulses, but when connected through synapses into vast networks, they produce consciousness, cognition, and memory. Similarly, research on xenobots—tiny, programmable living organisms constructed from frog cells—demonstrates emergence in action through their exhibition of movement, self-repair, and environmental responsiveness despite having no nervous system. These behaviors emerge solely from how the cells are assembled and interact, without central control structures [12].

In computational models, multi-agent pursuit-evasion games reveal how complex cooperative strategies like "lazy pursuit" (where one pursuer minimizes effort while complementing another's actions) and "serpentine movement" emerge from simple interaction rules. Through multi-agent reinforcement learning, these systems develop sophisticated behaviors such as pincer flank attacks and corner encirclement that weren't explicitly programmed but arise naturally from the system dynamics [13].

Experimental Protocols for Studying Emergence

Protocol 1: Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning for Emergent Behavior Analysis

- System Setup: Configure a bounded 2D grid world environment with defined coordinates and obstacle placements. Initialize multiple autonomous agents with basic movement capabilities.

- Behavioral Primitive Definition: Define fundamental action sets for agents (e.g., flank, engage, ambush, drive, chase, intercept for pursuit games). Establish composite actions for multi-agent coordination.

- Training Phase: Implement multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) algorithms with reward structures that incentivize goal achievement without prescribing specific cooperative strategies. Allow sufficient training cycles for strategy development.

- Trajectory Data Collection: Record complete movement trajectories and action sequences for all agents across multiple experimental trials with varying initial conditions.

- Behavioral Clustering Analysis: Apply K-means clustering or similar unsupervised learning methods to trajectory data to identify recurring patterns. Use dimensionality reduction techniques to visualize strategy clusters.

- Emergence Validation: Statistically analyze clustered behaviors for evidence of novel, unprogrammed cooperative strategies. Compare performance metrics between emergent strategies and predefined approaches [13].

Protocol 2: Bioelectrical Emergence Mapping in Cellular Assemblies

- Cell Source Preparation: Harvest pluripotent stem cells (e.g., frog embryonic cells for xenobot construction) and maintain in appropriate culture conditions.

- Bioelectrical Monitoring: Implement voltage-sensitive fluorescent dyes or ion-specific electrodes to map spatial distributions of bioelectrical signals across cell assemblies.

- Perturbation Experiments: Systematically modulate bioelectrical gradients through pharmacological agents (e.g., ion channel blockers/activators) or optogenetic stimulation.

- Morphological Tracking: Document resulting morphological changes and pattern formations using time-lapse microscopy with appropriate segmentation algorithms.

- Correlation Analysis: Establish statistical relationships between bioelectrical pattern disruptions and consequent changes in emergent structures and behaviors [12].

Foundational Concept 2: Network Biology

Theoretical Principles of Biological Networks

Biological networks provide the architectural framework that enables emergent properties in complex biological systems. The fundamental principle of network biology is that biomolecules do not perform their functions in isolation but rather interact with one another to form interconnected systems. These networks constitute the organizational backbone of biological systems, derived from different data sources and covering multiple biological scales. Prominent examples include co-expression networks, protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks, metabolic pathways, gene regulatory networks (GRNs), and drug-target interaction (DTI) networks [11].

In these network representations, nodes typically represent individual biological entities (genes, proteins, metabolites), while edges (connections) reflect functional, physical, or regulatory relationships between them. The topological properties of these networks—such as modularity, hub nodes, and shortest-path distributions—provide critical insights into biological function and organizational principles. Network analysis has revealed that biological systems often exhibit scale-free properties, where a few highly connected nodes (hubs) play disproportionately important roles in maintaining system integrity and function [11].

Analytical Approaches and Methodologies

Table 2: Network-Based Methods for Multi-Omics Data Integration in Biomedical Research

| Method Category | Key Algorithms/Approaches | Primary Applications | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Propagation/Diffusion | Random walk, heat diffusion | Gene prioritization, disease module identification | Robust to noise, captures local network neighborhoods |

| Similarity-Based Approaches | Network similarity fusion, matrix factorization | Drug repurposing, patient stratification | Integrates heterogeneous data types effectively |

| Graph Neural Networks | GCN, GAT, GraphSAGE | Drug response prediction, target identification | Learns complex non-linear network patterns |

| Network Inference Models | Bayesian networks, ARACNE | Regulatory network reconstruction, causal inference | Captures directional relationships and dependencies |

| Multi-Layer Networks | Integrated PPI, metabolic, regulatory networks | Comprehensive disease mechanism elucidation | Preserves context-specificity of different network types [11] |

Network-based analysis of biological systems employs diverse computational methodologies to extract meaningful insights from complex interaction data. Network propagation and diffusion methods leverage algorithms like random walks with restarts to prioritize genes or proteins associated with specific functions or diseases by simulating flow of information through the network. Similarity-based integration approaches fuse multiple omics data types by constructing similarity networks for each data type then combining them into a unified network representation. Graph neural networks represent the cutting edge of network analysis, using deep learning architectures specifically designed for graph-structured data to capture complex non-linear patterns in multi-omics datasets [11].

The application of these network-based methods has demonstrated significant utility in drug discovery, particularly for identifying novel drug targets, predicting drug responses, and facilitating drug repurposing. By contextualizing molecular entities within their network environments, these approaches can capture the complex interactions between drugs and their multiple targets, leading to more accurate predictions of therapeutic efficacy and potential side effects [11].

Experimental Protocol: Network-Based Multi-Omics Integration

Protocol 3: Multi-Layer Network Construction and Analysis for Drug Target Identification

Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Gather multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) from relevant samples (e.g., tumor vs. normal tissues).

- Perform quality control, normalization, and batch effect correction for each data type separately.

- Annotate molecular features with standardized identifiers for cross-referencing.

Network Resource Compilation:

- Collect established biological networks from public databases (STRING for PPIs, KEGG and Reactome for pathways, TRRUST for regulatory networks).

- Construct condition-specific networks (e.g., co-expression networks) from experimental data using correlation measures or information-theoretic approaches.

Data Integration via Network Propagation:

- Map molecular profiling data onto appropriate network layers.

- Implement network propagation algorithm to diffuse molecular signals across network neighborhoods.

- Integrate signals across multiple network layers using methods like similarity network fusion.

Candidate Prioritization:

- Apply machine learning classifiers to identify network regions enriched for disease association.

- Prioritize candidate targets based on network topology metrics (centrality, betweenness) and functional annotations.

- Validate predictions using independent datasets or experimental follow-up [11].

Foundational Concept 3: Multi-Scale Integration

Theoretical Framework for Cross-Scale Analysis

Multi-scale integration addresses one of the most fundamental challenges in biology: understanding the relationships between phenomena observed at different spatial and temporal scales in biological systems. From molecules to cellular functions, from collections of cells to organisms, or from individuals to populations, complex interactions between singular elements give rise to emergent properties at ensemble levels. The central question in multi-scale integration is to what extent the spatial and temporal order seen at the system level can be explained by subscale properties and interactions [14].

This conceptual framework recognizes that biological systems are organized hierarchically, with distinct behaviors and principles operating at each organizational level. Multi-scale integration seeks to bridge these levels by developing mathematical and computational tools that can translate understanding across scales. This approach is particularly valuable for understanding how molecular perturbations (e.g., genetic mutations, drug treatments) manifest as cellular, tissue, or organismal phenotypes—a critical challenge in drug development and disease modeling [14] [10].

Methodological Approaches and Applications

Multi-scale integration employs diverse methodologies to connect biological phenomena across scales. Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) represents a powerful application of multi-scale integration in drug development, leveraging comprehensive models that incorporate data from molecular, cellular, organ, and organism levels to simulate drug behaviors, predict patient responses, and optimize development strategies [9] [15].

At the research level, specialized training programs like the international course on "Multiscale Integration in Biological Systems" at Institut Curie provide frameworks for understanding modern physical tools that address scale integration and their application to specific biological systems. These approaches combine theoretical foundations with practical implementation across biological scales [14].

Educational initiatives have emerged to train scientists in these multi-scale approaches. Programs such as the University of Manchester's MSc in Model-based Drug Development and the University of Delaware's MSc in Quantitative Systems Pharmacology integrate real-world case studies with strong industry input to equip researchers with the skills needed for multi-scale modeling in biomedical contexts [9] [15].

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Scale Model Development

Protocol 4: Multi-Scale Model Development for Drug Response Prediction

System Decomposition and Scale Identification:

- Define distinct biological scales relevant to the research question (molecular, cellular, tissue, organ, organism).

- Identify key variables and processes at each scale and potential cross-scale interactions.

- Establish data requirements for parameterizing each scale.

Single-Scale Model Development:

- Develop mathematical representations for processes within each scale using appropriate formalisms (ODE/PDE for molecular/cellular, agent-based for cellular populations, PK/PD for organism level).

- Parameterize models using scale-specific experimental data.

- Validate individual scale models against independent data.

Cross-Scale Coupling:

- Establish coupling mechanisms between scales (e.g., how molecular signaling affects cellular behavior, how cellular responses integrate into tissue function).

- Implement numerical methods for efficient information passing between scales.

- Verify conservation principles and check for consistency across scale boundaries.

Model Integration and Validation:

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Systems Biology Investigations

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Analysis Software | Cytoscape, Gephi, NetworkX | Biological network visualization and analysis | Topological analysis of interaction networks [11] |

| Multi-Omics Databases | STRING, KEGG, Reactome, TRRUST | Reference network resources | Biological context for data interpretation [11] |

| Modeling Platforms | Virtual Cell, COPASI, PhysiCell | Multi-scale simulation environment | Mathematical modeling of cellular processes [16] |

| Educational Programs | MSc Systems Biology programs (multiple universities) | Specialized training in systems approaches | Workforce development in QSP and systems biology [9] [15] |

| Experimental Technologies | Single-cell mass cytometry, multiplexed imaging | High-dimensional data generation | Systems-level experimental data collection [10] |

| Bioelectrical Tools | Voltage-sensitive dyes, ion-specific electrodes | Monitoring bioelectrical signals | Emergent pattern formation studies [12] |

| MARL Frameworks | Multi-agent reinforcement learning platforms | Emergent behavior simulation | Complex system dynamics analysis [13] |

Implementation Framework for Systems Biology Research

Successful implementation of systems biology approaches requires careful consideration of several key aspects:

Computational Infrastructure Requirements:

- High-performance computing resources for large-scale network analysis and multi-scale simulations

- Data management systems for heterogeneous multi-omics datasets

- Version control and reproducible research practices for complex computational workflows

Experimental Design Considerations:

- Longitudinal sampling strategies to capture system dynamics

- Appropriate replication at the correct biological level for statistical power

- Perturbation-based experiments to probe system responses and identify causal relationships

Integration Challenges and Solutions:

- Computational scalability addressed through dimensionality reduction and efficient algorithms

- Biological interpretability maintained through iterative modeling-experimentation cycles

- Multi-disciplinary collaboration between experimental and computational researchers [10] [11]

Integrated Applications in Biomedical Research

Drug Discovery and Development Applications

The integration of emergent properties, network biology, and multi-scale modeling has transformative applications throughout the drug discovery and development pipeline. In drug target identification, network-based multi-omics integration methods can contextualize potential targets within their functional networks, identifying hub proteins critical to disease processes while minimizing unintended side effects. For drug response prediction, multi-scale models that incorporate molecular networks, cellular physiology, and tissue-level constraints can generate more accurate forecasts of therapeutic efficacy and potential resistance mechanisms. In drug repurposing, network methods can identify novel disease indications for existing compounds by detecting shared pathway perturbations across different conditions [11].

Leading pharmaceutical companies like AstraZeneca have established dedicated systems biology and QSP groups that employ these integrated approaches to inform decision-making in drug development. These groups develop computational models that span from molecular target engagement through physiological effects at the organism level, enabling more informed go/no-go decisions and clinical trial design [9] [15].

Case Study: Network-Based Multi-Omics Integration in Oncology

A representative application of these integrated approaches can be found in cancer systems biology. Researchers at UVA's Systems Biology and Biomedical Data Science program employ multi-omics integration to tackle challenges in cancer therapy. By combining genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data within network frameworks, they identify key regulatory nodes in cancer signaling networks that represent promising therapeutic targets. Multi-scale models then simulate how inhibition of these targets affects cellular behavior, tumor dynamics, and ultimately patient outcomes, enabling prioritization of the most promising candidates for experimental validation [10].

Similar approaches have been applied to COVID-19 research, where Liao et al. integrated multi-omics data spanning genomics, transcriptomics, DNA methylation, and copy number variations of SARS-CoV-2 virus target genes across 33 cancer types. This comprehensive analysis elucidated the genetic alteration patterns, expression differences, and clinical prognostic associations of these genes, demonstrating the power of network-based multi-omics integration for understanding complex disease mechanisms [11].

The integration of emergent properties, network biology, and multi-scale modeling represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research, moving the field from a reductionist focus on individual components to a systems-level understanding of biological complexity. These conceptual frameworks, supported by increasingly sophisticated computational and experimental methods, are enhancing our ability to understand disease mechanisms, predict drug effects, and develop novel therapeutic strategies.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas: incorporating temporal and spatial dynamics more explicitly into network models; improving the interpretability of complex AI-driven approaches; establishing standardized evaluation frameworks for comparing different integration methods; and enhancing computational scalability to handle increasingly large and diverse datasets. Furthermore, educational initiatives that train the next generation of researchers in both computational and experimental approaches will be crucial for realizing the full potential of systems biology in biomedical research and drug development [9] [11].

As these methodologies continue to mature and integrate, they promise to transform our fundamental understanding of biological systems and accelerate the development of novel therapeutics for complex diseases. The conceptual framework of emergent properties, networks, and multi-scale integration provides a powerful lens through which to decipher biological complexity and harness this understanding for improving human health.

Systems biology is a computational discipline that aims to understand the biological world at a system level by studying the relationships between the components that make up an organism [17]. Unlike traditional reductionist approaches that focus on individual components in isolation, systems biology investigates how molecular components (genes, proteins, metabolites) interact dynamically to confer emergent behaviors at cellular, tissue, and organismal levels. In biomedical research, this approach has revolutionized drug discovery and therapeutic development, enabling researchers to accelerate the identification of drug targets, optimize therapeutic strategies, and understand complex disease mechanisms [18] [17]. The field represents both a scientific and engineering discipline, applying modeling, simulation, and computational analysis to solve biological problems that were previously intractable through experimental methods alone.

The foundation of systems biology rests on the recognition of biological systems' extraordinary complexity. The human immune system alone comprises an estimated 1.8 trillion cells and utilizes around 4,000 distinct signaling molecules to coordinate its responses [18]. This complexity necessitates a systems-level approach that integrates quantitative molecular measurements with computational modeling to gain a comprehensive understanding of the broader biological context [18]. In biomedical applications, this approach enables researchers to move beyond descriptive biology to predictive science, generating testable hypotheses about therapeutic interventions and their mechanisms of action.

Theoretical Foundations

Core Principles of Systems Biology

Systems biology conceptualizes biological entities as dynamic, multiscale, and adaptive networks composed of heterogeneous cellular and molecular entities interacting through complex signaling pathways, feedback loops, and regulatory circuits [18]. These systems exhibit emergent properties such as robustness, plasticity, memory, and self-organization, which arise from local interactions and global system-level behaviors [18]. A fundamental theoretical principle is that biological systems are open, interacting with internal factors (e.g., microbiota, neoplastic cells) and external cues (e.g., pathogens, environmental signals) in ways that can be quantified and simulated through computational modeling [18].

From an engineering perspective, systems biology applies techniques such as parameter estimation, simulation, and sensitivity analysis to biological systems [17]. Parameter estimation enables researchers to calculate approximate values for model parameters based on experimental data, which is particularly valuable when wet-bench experiments to determine these values directly are too difficult or costly [17]. Simulation allows researchers to observe system behavior computationally, while sensitivity analysis identifies which components most significantly affect system outputs under specific conditions [17].

Key Biological Systems and Signaling Pathways

The Extracellular-Regulated Kinase (ERK) Pathway

The ERK signaling pathway serves as a canonical model system in systems biology, with over 125 ordinary differential equation models available in the BioModels database alone [19]. This pathway regulates critical cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, and survival, making it a prime target for therapeutic interventions in cancer and other diseases. The core ERK pathway integrates signals from multiple receptors and involves complex feedback mechanisms that create diverse dynamic behaviors, from sustained activation to oscillations [19].

Recent advances have revealed the importance of spatial regulation in intracellular signaling, with ERK activity demonstrating distinct dynamics in different subcellular locations [19]. Modern molecular tools and high-resolution microscopy have enabled researchers to observe these location-specific activities, necessitating more sophisticated models that can account for spatial organization and its functional consequences [19].

Diagram 1: ERK Signaling Pathway with Key Components

The Systems Biology Workflow

Data Acquisition and Multi-Omics Integration

The systems biology workflow begins with comprehensive data acquisition through multiple technological platforms. Single-cell technologies, including scRNA-seq, CyTOF, and single-cell ATAC-seq, are transforming systems immunology by revealing rare cell states and resolving heterogeneity that bulk omics overlook [18]. These datasets provide high-dimensional inputs for data analysis, enabling cell-state classification, trajectory inference, and the parameterization of mechanistic models with unprecedented biological resolution [18]. The integration of multi-omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) forms the foundation for constructing predictive models that can capture the complexity of biological systems.

In biomedical applications, these datasets enable researchers to develop machine learning models that improve diagnostics in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases and predict vaccine responses [18]. The quality and comprehensiveness of these datasets critically determine the robustness and predictive power of subsequent modeling efforts. Clinically, single-cell analyses are beginning to inform patient stratification and biomarker discovery, strengthening the translational bridge from data to therapy [18].

Mathematical Modeling Approaches

Mechanistic Modeling

Mechanistic models are quantitative representations of biological systems that describe how their components interact [18]. These models are built based on existing knowledge of the system and are validated by their ability to predict both known behaviors and previously unobserved system dynamics [18]. Analogous to experimental studies on biological systems, in silico experiments on mechanistic models enable the generation of novel hypotheses that may not emerge from empirical data alone [18].

The construction of mechanistic models is limited by current knowledge of the system under consideration, though unknown parameters are typically addressed through assumptions or by fitting experimental data [18]. While building these models is often slow and laborious, once implemented, they can conduct hundreds of virtual tests in a short time, dramatically accelerating the hypothesis generation and testing cycle [18].

Bayesian Multimodel Inference (MMI)

A significant challenge in systems biology is formulating models when many unknowns exist, and available data cannot observe every system component. Consequently, different mathematical models with varying simplifying assumptions and formulations often describe the same biological pathway [19]. Bayesian multimodel inference addresses this model uncertainty by systematically constructing a consensus estimator that leverages all specified models [19].

The MMI workflow involves calibrating available models to training data through Bayesian parameter estimation, then combining the resulting predictive probability densities using weighting approaches such as Bayesian model averaging (BMA), pseudo-Bayesian model averaging (pseudo-BMA), and stacking of predictive densities [19]. This approach increases predictive certainty and robustness when multiple models of the same signaling pathway are available [19].

Diagram 2: Bayesian Multimodel Inference Workflow

Model Simulation and Analysis

Simulation enables researchers to observe system behavior in action, change inputs, parameters, and components, and analyze results computationally [17]. Unlike most engineering simulations, which are deterministic, biological simulations must incorporate the innate randomness of nature through Monte Carlo techniques and stochastic simulations [17]. These approaches account for the probabilistic nature of biological interactions, where reactions occur with certain probabilities, and molecular binding events vary between simulations.

Sensitivity analysis provides a computational mechanism to determine which parameters most significantly affect model outputs under specific conditions [17]. In a model with hundreds of species and parameters, sensitivity analysis can identify which elements most strongly influence desired outputs, helping researchers eliminate fruitless research avenues and focus wet-bench experiments on the most promising candidates [17]. This approach is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical applications, where it can prioritize drug targets based on their potential impact on disease-relevant pathways.

Experimental Validation and Model Refinement

The systems biology workflow culminates in experimental validation of model predictions, creating an iterative cycle of refinement. Models generate testable hypotheses about system behavior under perturbation, which are then evaluated through targeted experiments. Discrepancies between predictions and experimental results inform model refinement, leading to increasingly accurate representations of biological reality.

In drug discovery, this approach enables researchers to develop computational models of drug candidates and run simulations to reject those with little chance of success before proceeding to animal or human trials [17]. This strategy addresses the cost, inefficiency, and potential risks of traditional trial-and-error approaches, transforming the drug development pipeline [17]. Major pharmaceutical companies have consequently transformed small proof-of-concept initiatives into fully funded Systems Biology departments [17].

Quantitative Methods and Data Presentation

Key Mathematical Frameworks in Systems Biology

Table 1: Core Mathematical Modeling Approaches in Systems Biology

| Model Type | Key Features | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanistic ODE Models | Describe system dynamics using ordinary differential equations; parameters have biological meaning | ERK signaling pathway modeling; metabolic flux analysis | Require substantial prior knowledge; parameter estimation challenging with sparse data |

| Bayesian Multimodel Inference (MMI) | Combines predictions from multiple models using weighted averaging; accounts for model uncertainty | Increasing prediction certainty for intracellular signaling; robust prediction with multiple candidate models | Computational intensive; requires careful weight estimation methods (BMA, pseudo-BMA, stacking) |

| Stochastic Models | Incorporate randomness in biological reactions; use Monte Carlo techniques | Cellular decision-making; genetic circuit behavior; rare event analysis | Computationally demanding; results vary between simulations |

| Machine Learning Approaches | Learn patterns from high-dimensional data; deep learning with multiple layers for feature extraction | Biomarker discovery; predicting immune responses to vaccination; patient stratification | Require large, high-quality datasets; model interpretability challenges |

Parameter Estimation and Sensitivity Analysis

Parameter estimation automatically computes model parameter values using data gathered through experiments, rather than relying on educated guesses [17]. This capability is vital in systems biology because researchers often know what molecular components must be present in a model or how species react with one another, but lack reliable estimates for parameters such as reaction rates and concentrations [17]. Parameter estimation enables calculation of these values when direct experimental determination is too difficult or costly.

Sensitivity analysis computational determines which parameters most significantly affect model outputs under specific conditions [17]. In a model with 200 species and 100 different parameters, sensitivity analysis can identify which species and parameters most strongly influence desired outputs, enabling researchers to focus experimental efforts on the most promising candidates [17].

Table 2: Systems Biology Software and Computational Tools

| Tool/Platform | Primary Function | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| SimBiology | Graphical model construction and simulation | Molecular pathway modeling; stochastic solvers; sensitivity analysis; conservation laws | Pharmaceutical drug discovery; metabolic engineering |

| BioModels Database | Repository of curated models | Over 125 ERK signaling models; standardized model exchange | Model sharing and reuse; comparative analysis of pathway models |

| Single-cell Omics Platforms | High-dimensional data generation | scRNA-seq; CyTOF; single-cell ATAC-seq; cell-state classification | Resolving cellular heterogeneity; biomarker discovery; patient stratification |

| Bayesian MMI Workflow | Multimodel inference and prediction | BMA, pseudo-BMA, and stacking methods; uncertainty quantification | Robust prediction when multiple candidate models exist |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol Generation with Structured Reasoning

The planning and execution of scientific experiments in systems biology hinges on protocols that serve as operational blueprints detailing procedures, materials, and logical dependencies [20]. Well-structured protocols ensure experiments are reproducible, safe, and scientifically valid, which is essential for cumulative progress [20]. The "Sketch-and-Fill" paradigm formulates protocol generation as a structured reasoning process where each step is decomposed into essential components and expressed in natural language with explicit correspondence, ensuring logical coherence and experimental verifiability [20].

This approach separates protocol generation into analysis, structuring, and expression phases to ensure each step is explicit and verifiable [20]. Complementing this, structured component-based reward mechanisms evaluate step granularity, action order, and semantic fidelity, aligning model optimization with experimental reliability [20]. For systems biology applications, this structured approach to protocol generation enhances reproducibility and facilitates the translation of computational predictions into experimental validation.

Core Experimental Methodologies in Systems Biology

Bayesian Parameter Estimation Protocol

Objective: Calibrate model parameters to experimental data using Bayesian inference.

Materials:

- Experimental data (time-course or dose-response measurements)

- Computational model of the biological system

- Bayesian inference software (e.g., Stan, PyMC3, SimBiology)

- High-performance computing resources

Procedure:

- Model Specification: Define the mathematical structure of the model, including state variables, parameters, and equations describing system dynamics.

- Prior Selection: Specify prior distributions for all unknown parameters based on literature values or experimental knowledge.

- Likelihood Definition: Formulate the likelihood function describing how experimental observations relate to model predictions.

- Posterior Sampling: Use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods to sample from the posterior distribution of parameters given the data.

- Convergence Diagnostics: Assess MCMC convergence using metrics such as Gelman-Rubin statistics and trace plot inspection.

- Posterior Analysis: Extract parameter estimates and credible intervals from the posterior samples.

- Model Validation: Compare model predictions with validation data not used during parameter estimation.

Validation Metrics: Posterior predictive checks, residual analysis, cross-validation performance.

Multimodel Inference Implementation

Objective: Combine predictions from multiple models to increase prediction certainty.

Materials:

- Set of candidate models for the biological system

- Training and validation datasets

- MMI computational framework

Procedure:

- Model Set Definition: Select a set of candidate models representing different hypotheses about system mechanism.

- Individual Model Calibration: Estimate parameters for each model separately using Bayesian inference.

- Weight Calculation: Compute model weights using one of three methods:

- BMA: Calculate marginal likelihood for each model

- Pseudo-BMA: Estimate expected log pointwise predictive density (ELPD)

- Stacking: Optimize weights to maximize predictive performance

- Consensus Prediction: Form multimodel prediction as weighted average of individual model predictions.

- Uncertainty Quantification: Calculate credible intervals for multimodel predictions.

- Robustness Assessment: Evaluate prediction stability under changes to model set composition.

Validation Metrics: Prediction accuracy on holdout data, robustness to model set perturbations, uncertainty calibration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Systems Biology Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| High-Resolution Microscopy Tools | Enable spatial monitoring of signaling activity at subcellular resolution | Measurement of location-specific ERK dynamics; single-molecule tracking |

| Single-cell Omics Reagents | Facilitate cell-state classification and heterogeneity analysis | scRNA-seq for immune cell profiling; CyTOF for protein expression analysis |

| Molecular Tools for Spatial Regulation | Enable precise manipulation of signaling activity in specific locations | Optogenetic controls; targeted inhibitors for subcellular compartments |

| Bayesian Inference Software | Implement parameter estimation and uncertainty quantification | Stan, PyMC3, SimBiology for model calibration; MMI implementation |

| Sensitivity Analysis Tools | Identify parameters with greatest influence on model outputs | Local and global sensitivity analysis; parameter ranking for experimental prioritization |

Applications in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Systems biology approaches have demonstrated significant impact across multiple biomedical domains. In immunology, systems immunology integrates multi-omics data, mechanistic models, and artificial intelligence to reveal emergent behaviors of immune networks [18]. Applications span autoimmune, inflammatory, and infectious diseases, with these methods used to identify biomarkers, optimize therapies, and guide drug discovery [18]. The field has particular relevance for understanding the extraordinary complexity of the mammalian immune system, which utilizes intricate networks of cells, proteins, and signaling pathways that coordinate protective responses and, when dysregulated, drive immune-related diseases [18].

In pharmaceutical development, systems biology enables more efficient comparison of therapies targeting different immune pathways or exhibiting diverse pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles [18]. By incorporating PK/PD considerations, mathematical models can facilitate optimization of new treatment strategies and accelerate drug discovery [18]. Major pharmaceutical companies have consequently established dedicated systems biology departments, transforming small proof-of-concept initiatives into fully funded research programs [17].

The future of systems biology in biomedical research will be shaped by advancing technologies and methodologies. Single-cell technologies continue to enhance resolution of cellular heterogeneity, while artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches are increasingly deployed for pattern recognition in high-dimensional data [18]. Bayesian multimodel inference represents a promising approach for increasing prediction certainty when multiple models of the same biological pathway are available [19].

Challenges remain in data quality, model validation, and regulatory considerations that must be addressed to fully translate systems biology into clinical impact [18]. Collaboration between computational modelers and biological experimentalists remains essential, requiring environments that enable scientists with different expertise to work effectively together [17]. As these challenges are addressed, systems biology will play an increasingly central role in biomedical research, accelerating therapeutic development and improving understanding of complex biological systems.

Methodologies and Translational Applications in Disease Research

Computational and Mathematical Modeling of Biological Networks

Within the broader thesis on the role of systems biology in biomedical research, computational and mathematical modeling of biological networks represents a foundational pillar. Systems biology is an interdisciplinary approach that seeks to understand how biological components—genes, proteins, and cells—interact and function together as a system [21]. It stands in stark contrast to reductionist biology by putting the pieces together to see the larger picture, be it at the level of the organism, tissue, or cell [22]. This paradigm shift is crucial for biomedical research, as it enables a more comprehensive understanding of human disease, the development of targeted therapies, and the advancement of personalized medicine [8] [21].

Biological networks are the physical and functional connections between molecular entities within a cell or organism. Modeling these networks allows researchers to move from descriptive lists of components to predictive, quantitative frameworks [22]. By integrating diverse data types through multiomics approaches and employing sophisticated computational tools, these models can simulate complex biological behaviors under various conditions, offering unprecedented insights into health and disease [21].

Core Concepts and Quantitative Foundations

The modeling of biological networks is built upon a foundation of well-established concepts and quantitative measures that allow for the comparison and interpretation of complex systems data.

Types of Biological Networks

Biological networks can be categorized based on the nature of the interactions they represent. The table below summarizes the primary types of networks encountered in systems biology research.

Table 1: Key Types of Biological Networks and Their Characteristics

| Network Type | Nodal Elements | Edge Interactions | Primary Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Regulatory Networks | Genes, Transcription Factors | Regulation of expression | Controls transcriptional dynamics and cellular state [23] |

| Protein-Protein Interaction Networks | Proteins | Physical binding, complex formation | Mediates signaling, structure, and enzymatic activities [23] |

| Metabolic Networks | Metabolites, Enzymes | Biochemical reactions | Converts nutrients into energy and cellular building blocks [23] |

| Signaling Networks | Proteins, Lipids, Ions | Phosphorylation, activation | Processes extracellular signals to dictate cellular responses [22] |

Quantitative Data for Network Comparison

When comparing quantitative data derived from different biological groups or conditions, appropriate numerical and graphical summaries are essential. The following example, derived from a study on gorilla chest-beating rates, illustrates how to structure such comparative data [24].

Table 2: Numerical Summary for Comparing Chest-Beating Rates Between Younger and Older Gorillas

| Group | Mean (beats/10h) | Standard Deviation | Sample Size (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Younger | 2.22 | 1.270 | 14 |

| Older | 0.91 | 1.131 | 11 |

| Difference | 1.31 | — | — |

For visualizing such comparisons, parallel boxplots are highly effective, especially for highlighting differences in medians, quartiles, and identifying potential outliers across groups [24]. This approach allows researchers to quickly assess distributional differences in network-related metrics, such as node connectivity or expression levels, between experimental conditions or patient cohorts.

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Constructing accurate biological network models requires a rigorous, multi-stage process that integrates experimental data generation with computational analysis. The workflow below outlines the primary stages, from initial data acquisition to final model validation.

Diagram 1: Network Modeling Workflow

Data Acquisition and Multi-omics Integration

The first critical phase involves generating comprehensive, high-quality data. Systems biology relies on the integration of diverse data types to construct a holistic view of the biological system [21].

- Multi-omics Data Generation: Modern network modeling utilizes data from various "omics" technologies, including genomics (genetic blueprint), transcriptomics (gene expression), proteomics (protein abundance and modifications), metabolomics (metabolite profiles), and epigenomics (regulatory marks) [21]. For instance, the NIAID Laboratory of Systems Biology employs genome-wide RNAi screens to characterize signaling network relationships and mass spectrometry to investigate protein phosphorylation, a key regulatory mechanism [22].

- Perturbation Strategies: A core principle of systems biology is measuring system-wide responses to controlled perturbations. These can include genetic variations (e.g., knockouts, knockdowns), chemical treatments (e.g., drug inhibitors), environmental changes, or physiological stimuli (e.g., vaccinations) [22]. As highlighted by the NIH researchers, "all are valuable perturbations to help us figure out the wiring and function of the underlying system" [22].

Network Inference and Model Construction

Once data is acquired, computational methods are applied to infer the network structures and their dynamics.

Bottom-Up vs. Top-Down Approaches:

- Bottom-Up approaches involve building detailed, fine-grained models of specific subsystems, such as the signaling pathways within a particular cell type. This often requires extensive prior knowledge of kinetic parameters and interaction mechanisms [22].