Systems Biology in Biomarker Validation: From Discovery to Clinical Application

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the integration of systems biology into the biomarker validation pipeline for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Systems Biology in Biomarker Validation: From Discovery to Clinical Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the integration of systems biology into the biomarker validation pipeline for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of moving beyond single-target approaches to understand complex disease networks. The scope covers methodological frameworks that combine high-throughput omics technologies, in silico modeling, and preclinical studies to develop robust, multi-marker panels. It further addresses critical challenges in optimization and troubleshooting, including specificity, reproducibility, and analytical variability. Finally, the article details rigorous statistical and clinical validation protocols, featuring comparative analyses of real-world algorithms to establish clinical utility and translate biomarker panels into tools for precision medicine.

The Systems Biology Framework: A New Paradigm for Biomarker Discovery

The landscape of disease diagnosis and monitoring is undergoing a fundamental transformation, shifting from reliance on single biomarkers to the implementation of multi-marker panels. This evolution is particularly critical for complex diseases such as pancreatic cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and autoimmune conditions, where single-target biomarkers often lack sufficient sensitivity and specificity for early detection and accurate prognosis. By integrating diverse molecular information through systems biology approaches, multi-marker panels capture the multifaceted nature of disease pathophysiology, offering significantly improved diagnostic performance. This review synthesizes current evidence supporting the superiority of biomarker panels, details experimental methodologies for their development and validation, and frames these advances within the context of systems biology, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive resource for advancing diagnostic innovation.

Traditional diagnostic approaches have predominantly relied on pauci-parameter measurements—often just a single parameter—to decipher specific disease conditions [1]. While simple and historically valuable, this approach presents significant limitations for complex multifactorial diseases. Single-marker tests (SMTs) fundamentally lack the robustness to capture the intricate biological networks perturbed in conditions like cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and autoimmune diseases [2] [1].

The well-documented flaws of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) exemplify these limitations. As the only FDA-approved serological biomarker for PDAC, CA19-9 demonstrates increasing concentration and sensitivity with advancing disease stage. However, in early stages (e.g., stage I), its levels are often similar to those found in various benign conditions and other malignancies, resulting in unacceptably low specificity for early detection [3]. Furthermore, approximately 6% of Caucasians and 22% of non-Caucasians lack Lewis antigen A necessary to produce CA19-9, leading to false-negative results [3]. Consequently, international guidelines do not recommend CA19-9 as a standalone diagnostic method but rather as a longitudinal marker in patients with detectable levels at baseline [3].

Theoretical and empirical studies confirm that single-marker approaches face inherent constraints. In genetic association studies of rare variants, SMTs struggle with low statistical power and potential violations of established estimator properties [4]. While multi-marker tests (MMTs) were proposed to address these challenges, their performance relative to SMTs depends on specific conditions. For quantitative traits, SMTs can outperform MMTs when causal variants have large effect sizes, while MMTs show advantage with small effect sizes—a common scenario in complex diseases [4]. For binary traits, the power dynamics differ further, highlighting that no uniformly superior test exists for all scenarios [5].

Theoretical Foundation: Advantages of Multi-Marker Strategies

Multi-marker panels address fundamental gaps in single-target approaches by capturing disease heterogeneity, improving statistical power, and representing the interconnected nature of biological systems.

Capturing Disease Heterogeneity and Biological Complexity

Complex diseases like pancreatic cancer, multiple sclerosis, and psychiatric disorders involve dysregulation across multiple biological pathways rather than isolated molecular defects [2] [6]. Multi-protein biomarker tests are particularly suited for measuring disease progression because they can capture the breadth of disease heterogeneity across patient populations and within individual patients as their biology changes in response to disease manifestations, aging, and therapies [6].

The systems biology perspective recognizes that biological information in living systems is captured, transmitted, modulated, and integrated by networks of molecular components and cells [1]. Disease-associated molecular fingerprints result from perturbations to these biological networks, which are better captured by measuring multiple network nodes simultaneously than by assessing individual components in isolation [1]. This approach has revealed that initial molecular network changes often occur well before any detectable clinical signs of disease, creating opportunities for earlier intervention if these multi-component signatures can be detected [1].

Statistical and Diagnostic Performance Advantages

From a statistical perspective, multi-marker panels incorporate various sources of biomolecular and clinical data to guarantee higher robustness and power of separation for clinical tests [2]. The performance advantage depends on the correlation structure among markers and their relationship to causal disease variants [5]. When adjacent markers show high correlation, multi-marker tests tend to demonstrate better performance than single-marker tests [5].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Single-Marker vs. Multi-Marker Approaches

| Feature | Single-Marker Tests | Multi-Marker Panels |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Coverage | Limited to one pathway or process | Captures multiple disease-relevant pathways simultaneously |

| Statistical Power | Varies by effect size; better for large effects | Generally superior for small effect sizes common in complex diseases |

| Handling Heterogeneity | Poor; misses disease subtypes | Good; can identify and stratify patient subgroups |

| Diagnostic Specificity | Often compromised by non-disease influences | Enhanced through multi-parameter assessment |

| Early Detection Capability | Limited for complex diseases | Improved through network perturbation detection |

Evidence and Case Studies: Performance Across Disease Areas

Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC)

Pancreatic cancer exemplifies the critical need for better diagnostic approaches, with a dismal 5-year survival rate of approximately 10% largely attributable to late diagnosis [3]. At diagnosis, less than 20% of PDAC tumors are eligible for curative resection, highlighting the urgent need for early detection methods [3]. Liquid biopsy—the minimally invasive sampling and analysis of body fluids like blood—offers promising avenues for PDAC detection through analysis of circulating tumor cells (CTCs), circulating cell-free DNA and RNA (cfDNA, cfRNA), extracellular vesicles (EVs), and proteins [3].

While individual liquid biopsy biomarkers may lack sufficient sensitivity or specificity for reliable PDAC detection, combinations in multimarker panels significantly improve diagnostic performance. CTCs specifically demonstrate high specificity for PDAC (>90% in several studies) but present detection challenges in early stages due to low abundance—approximately one CTC among more than a million blood cells—and a short half-life of only 1–2.4 hours [3]. This limitation may be overcome with novel, more sensitive analysis techniques and processing of larger blood volumes [3].

Beyond traditional tumor-derived markers, the prominent desmoplastic stroma characteristic of PDAC provides additional biomarker sources. Circulating host cells, including cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), represent key components of the tumor microenvironment that can detach and enter circulation as possible liquid biopsy biomarkers [3]. The three major CAF types—myofibroblast CAFs (myCAFs), inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs), and antigen-presenting CAFs (apCAFs)—perform distinct functions and may provide complementary information when incorporated into multi-analyte panels [3].

Ovarian Cancer

A retrospective study investigating multimarker combinations for early ovarian cancer detection identified an optimal 4-marker panel comprising CA125, HE4, MMP-7, and CA72-4 [7]. This panel demonstrated significantly improved performance compared to any single marker alone, achieving 83.2% sensitivity for stage I disease at a high specificity of 98% [7].

Critical to their utility in longitudinal screening algorithms, the selected markers exhibited favorable variance characteristics, with within-person coefficient of variation (CV) values lower than between-person CV values: CA125 (15% vs. 49%), HE4 (25% vs. 20%), MMP-7 (25% vs. 35%), and CA72-4 (21% vs. 84%) [7]. This variance profile indicates stable individual baselines in healthy volunteers, enabling the establishment of person-specific reference ranges that enhance early detection capability when deviations occur.

Multiple Sclerosis

In multiple sclerosis, measuring disease progression—the driver of long-term disability—has remained particularly challenging with conventional clinical assessments alone [6]. The future of progression management lies in multi-protein biomarker tests, which can provide quantitative, objective insights into disease biology that imaging and symptom assessment cannot capture [6].

Multi-protein tests are ideal for measuring MS progression because they can capture disease heterogeneity across populations and within individual patients, while offering prognostic power that enables personalized medicine approaches [6]. Development of such panels involves evaluating thousands of proteins as potential biomarkers, examining both statistical associations with progression endpoints and biological relevance to MS pathways and mechanisms [6].

Methodological Framework: Developing and Validating Marker Panels

Experimental Design and Statistical Considerations

Robust development of multi-marker panels requires specialized methodological approaches to address unique statistical challenges. A primary concern is obtaining unbiased estimates of both the biomarker combination rule and the panel's performance, typically evaluated via ROC(t)—the sensitivity corresponding to specificity of 1-t on the receiver operating characteristic curve [8].

Two-stage group sequential designs offer efficiency for biomarker development by allowing early termination for futility, thereby conserving valuable specimens when initial performance is inadequate [8]. In such designs, biomarker data is collected from first-stage samples, the panel is built and evaluated, and if pre-specified performance criteria are met, the study continues to the second stage with remaining samples assayed [8]. Nonparametric conditional resampling algorithms can then use all study data to provide unbiased estimates of the biomarker combination rule and ROC(t) [8].

An additional source of bias arises from using the same data to derive the combination rule and estimate performance, particularly problematic in studies with small sample sizes [8]. The Copas & Corbett (2002) shrinkage correction addresses this bias and can be incorporated into resampling algorithms [8].

Table 2: Key Methodological Considerations in Panel Development

| Development Phase | Key Considerations | Recommended Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Study Design | Resource optimization; Early futility assessment | Two-stage group sequential design; Conditional unbiased estimation |

| Biomarker Selection | Balancing statistical association with biological plausibility | Integration of correlation data with pathway analysis |

| Statistical Modeling | Over-optimism bias with small sample sizes | Shrinkage corrections; Resampling methods |

| Performance Evaluation | Comprehensive assessment of discriminative ability | ROC(t) estimation; Sensitivity at fixed specificity |

| Validation | Generalizability across populations | Testing in multiple independent cohorts |

Systems Biology Framework

Systems biology approaches view biology as an information science, studying biological systems as a whole and their interactions with the environment [1]. This perspective has particular power in biomarker discovery because it focuses on fundamental disease causes and identifies disease-perturbed molecular networks [1] [9].

The transformation in biology through systems biology enables systems medicine, which uses clinically detectable molecular fingerprints resulting from disease-perturbed biological networks to detect and stratify pathological conditions [1]. These molecular fingerprints can be composed of diverse biomolecules—proteins, DNA, RNA, miRNA, metabolites—and their post-translational modifications, all providing complementary information about network states [1].

In practice, applying systems biology to complex diseases involves several key steps: measuring global biological information, integrating information across different levels, studying dynamic changes in biological systems as they respond to environmental influences, modeling the system through integration of global dynamic data, and iteratively testing and improving models through prediction and comparison [1]. This approach was successfully applied to prion disease, revealing dynamically changing perturbed networks that occur well before clinical signs appear [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing multi-marker panel research requires specialized reagents and technologies across multiple analytical domains. The following table details essential research tools and their applications in panel development and validation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies for Multi-Marker Studies

| Reagent/Technology | Function | Application in Panel Development |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Biopsy Collection Systems | Standardized sample acquisition from blood, saliva, urine | Minimizes pre-analytical variability across multi-center studies |

| Immunoassay Reagents | Quantification of protein biomarkers (e.g., CA125, HE4) | Enables precise measurement of panel components in validation phases |

| Proteomic Analysis Platforms | Simultaneous measurement of thousands of proteins | Facilitates discovery phase biomarker identification |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Kits | Genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic analysis | Provides complementary molecular dimensions for comprehensive panels |

| Extracellular Vesicle Isolation Kits | Enrichment of exosomes and microvesicles | Expands analyte repertoire beyond conventional biomarkers |

| Multiplex PCR Reagents | Amplification of multiple nucleic acid targets | Supports genetic and transcriptomic panel components |

| Reference Standard Materials | Calibration and quality control | Ensures reproducibility and comparability across batches and sites |

| Data Integration Software | Systems biology analysis of multi-omic data | Enables network-based biomarker selection and validation |

| Tioxaprofen | Tioxaprofen, CAS:40198-53-6, MF:C18H13Cl2NO3S, MW:394.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Talatisamine | Talatisamine, MF:C24H39NO5, MW:421.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The transition from single-target biomarkers to multi-marker panels represents a paradigm shift in diagnostic development, particularly for complex diseases where multiple biological pathways are perturbed. By capturing disease heterogeneity, leveraging complementary information from diverse analytes, and reflecting the network nature of disease pathophysiology, multi-marker approaches offer substantially improved sensitivity and specificity compared to traditional single-marker tests. The integration of systems biology principles provides a robust framework for discovering and validating these panels, while advanced statistical methods address the unique challenges of development and performance estimation. As measurement technologies continue to advance and computational methods become more sophisticated, multi-marker panels are poised to transform disease detection, monitoring, and ultimately patient outcomes across a spectrum of complex conditions.

In the disciplined approach of modern drug discovery and development, the Mechanism of Disease (MOD) and Mechanism of Action (MOA) provide the essential conceptual framework for understanding disease pathology and therapeutic intervention. The MOD defines the precise biological pathways, molecular networks, and pathophysiological processes that contribute to a disease state [10]. In parallel, the MOA describes the specific biochemical interaction through which a therapeutic entity produces its pharmacological effect, ideally counteracting the MOD [10]. Within biomarker science, these concepts transition from theoretical models to practical tools; biomarkers serve as the measurable indicators that provide an objective window into these mechanisms, bridging the gap between biological theory and clinical application [11] [12]. The integration of MOD and MOA knowledge is therefore critical for the rational development of biomarker panels, moving beyond simple correlation to establish causative links that can reliably predict disease progression or therapeutic response.

Defining the Framework: MOD, MOA, and Biomarker Interrelationships

Formal Definitions and Classifications

- Mechanism of Disease (MOD): A comprehensive description of the network of biological pathways, molecular interactions, and cellular processes that are dysregulated and contribute to the initiation and progression of a pathological condition [10]. The MOD represents the fundamental target for any therapeutic intervention.

- Mechanism of Action (MOA): The specific biochemical interaction through which a drug substance produces its pharmacological effect, typically designed to modulate a key element within the MOD network to restore a state of health [10].

- Biomarker: "A defined characteristic that is measured as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or responses to an exposure or intervention" [11]. Biomarkers are the empirical observables that are perturbed by the MOD and subsequently modulated by the MOA.

Biomarker Classifications Within the MOD/MOA Context

Biomarkers are categorized based on their specific application in the drug development continuum, each type providing distinct insights into MOD or MOA [11] [12]:

Table: Biomarker Classifications and Their Roles in MOD and MOA

| Biomarker Type | Definition | Role in MOD/MOA Context | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic | Detects or confirms presence of a disease or condition [11]. | Identifies the manifestation of the MOD in a specific patient. | AMACR for prostate cancer [13]. |

| Monitoring | Measured serially to assess status of a disease or medical condition [11]. | Tracks the activity of the MOD over time or in response to a therapy. | CD4 counts in HIV [11]. |

| Pharmacodynamic/ Response | Indicates a biological response to a therapeutic intervention [11]. | Provides direct evidence of the MOA in action. | HIV viral load under antiretroviral treatment [12]. |

| Predictive | Identifies individuals more likely to experience a favorable or unfavorable effect from a specific therapeutic [11]. | Stratifies patients based on the relevance of a specific MOA to their individual MOD. | Galactomannan for enrolling patients in antifungal trials [12]. |

| Safety | Indicates the potential for or occurrence of toxicity due to an intervention [11]. | Monitors for unintended consequences of the MOA, often related to off-target effects. | Hepatic aminotransferases for liver toxicity [12]. |

A Systems Biology Platform for Integrating MOD and MOA in Biomarker Development

The complexity of human biology and the multifactorial nature of most diseases mean that a "single-target" drug development approach is often insufficient [10]. Systems biology provides an interdisciplinary framework that uses computational and mathematical methods to study complex interactions within biological systems, making it ideally suited for elucidating MOD and MOA [10]. This approach is fundamental for developing robust biomarker panels.

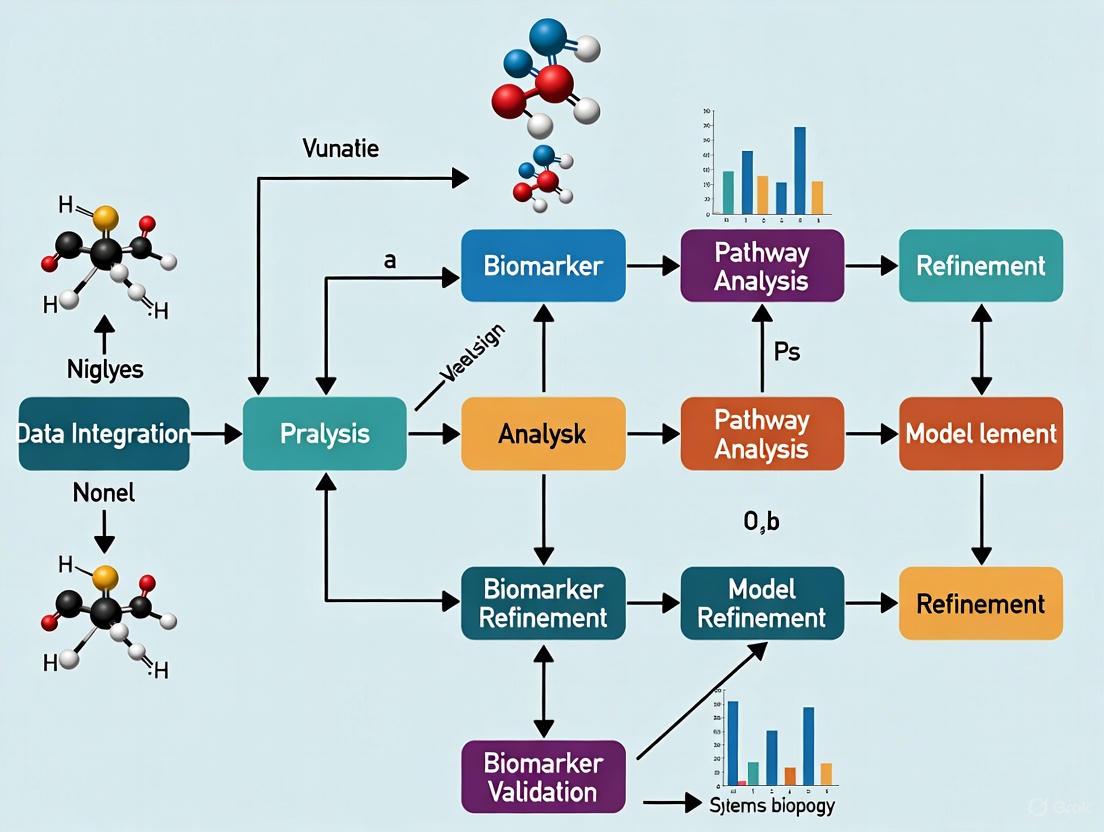

A Stepwise Systems Biology Workflow

The following workflow visualizes the systematic, multi-stage process for developing biomarker panels through the integration of MOD and MOA.

This platform begins with the integration of multi-scale data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to map the complex network of the MOD [10] [14]. The subsequent identification and design of therapies with a specific MOA are then informed by this network model. Finally, candidate biomarker panels are distilled from the key nodes and pathways that connect the MOD and MOA, enabling the translation of these mechanistic insights into clinical tools for patient stratification and treatment monitoring [10].

Comparative Analysis: Mechanism-Based vs. Traditional Biomarker Discovery

The shift from a traditional, data-centric biomarker discovery pipeline to a mechanism-based approach that is grounded in MOD/MOA understanding represents a significant evolution in the field. The mechanism-based paradigm leverages the growing wealth of functional knowledge and multi-omics data to yield biomarkers with greater biological relevance and clinical utility [15].

Table: Comparison of Traditional and Mechanism-Based Biomarker Discovery

| Aspect | Traditional Approach | Mechanism-Based (MOD/MOA-Driven) Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Data-driven; seeks statistically significant differences between sample groups without prior mechanistic hypothesis [15]. | Knowledge-driven; starts with or builds a model of the MOD to inform biomarker selection [10] [15]. |

| Typical Methods | Untargeted mass spectrometry, broad microarrays, followed by targeted ELISA validation [15]. | Pathway analysis, network modeling, multi-omics integration, and systems biology platforms [10] [15]. |

| Primary Output | Lists of differentially expressed biomolecules (genes, proteins, metabolites) [15]. | Contextualized biomarker panels that map onto specific pathways within the MOD/MOA network [16]. |

| Key Strength | Unbiased; can discover novel associations without preconceptions. | Results are more interpretable and biologically plausible, facilitating clinical adoption [15]. |

| Major Challenge | High false-positive rate; poor validation performance due to lack of biological context [15]. | Requires high-quality, multi-scale data and sophisticated computational models [10]. |

| Clinical Translation | Often fails because the biomarker's link to disease pathology is not well understood [15]. | Higher potential for success as biomarkers are inherently linked to core disease mechanisms and drug actions [10]. |

Case Study: Uncovering MOD and Biomarkers in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder

A 2021 study published in Scientific Reports provides a compelling example of a mechanism-based, systems biology approach to biomarker discovery for complex mental disorders [16]. The research aimed to identify the pathways underlying schizophrenia (SCZ) and bipolar disorder (BD) by starting with a curated set of metabolite biomarkers.

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The methodology followed a structured, multi-stage computational and analytical process, as detailed below.

- Data Collection: The researchers first compiled 46 metabolite biomarkers previously reported in the literature for SCZ and BD (e.g., glutamate, GABA, citrate, myo-inositol) from human blood and serum samples [16].

- Protein Collection: These metabolite biomarkers were then mapped to their related enzymes and proteins using the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway maps, resulting in a set of 610 proteins for SCZ and 495 for BD [16].

- Network Construction: A protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed using the HIPPIE database, creating a large network of 5,595 interactions among 3,184 proteins relevant to the diseases [16].

- Cluster and Pathway Analysis: A graph-clustering algorithm (DPClusO) was applied to this PPI network to identify statistically significant functional modules. These clusters were then analyzed to elucidate the significant pathways underlying the diseases [16].

Key Findings and Outcomes

This mechanism-based analysis revealed that the 28 significant pathways identified for SCZ and BD primarily coalesced into three major biological systems, providing a novel, integrated view of their MOD [16]:

- Energy Metabolism: Dysregulation in pathways such as citrate cycle, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and oxidative phosphorylation.

- Neuron System: Alterations in glutamatergic, GABAergic, and cholinergic synapse pathways.

- Stress Response: Involvement of hypoxia response and reactive oxygen species pathways.

This case demonstrates how starting with empirical biomarker data and applying a systems biology workflow can yield a coherent and biologically plausible model of the MOD, moving beyond a simple list of biomarkers to an interconnected network of pathological processes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing a mechanism-based biomarker discovery pipeline requires a suite of specific reagents, databases, and technological platforms.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for MOD/MOA Biomarker Research

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Omics Profiling | Sequencing platforms (e.g., AVITI24), proteomic mass spectrometers, metabolomic NMR/MS [14]. | Generate the high-throughput molecular data required to model the MOD. |

| Knowledge Bases | HIPPIE (PPIs), KEGG (pathways), HMDB (metabolites) [16] [15]. | Provide curated biological knowledge to connect biomarkers into functional pathways and networks. |

| Analysis Software | Cytoscape (network visualization), DPClusO (graph clustering), R/Bioconductor packages [16] [15]. | Enable the construction, analysis, and visualization of complex biological networks. |

| Affinity Reagents | Antibodies, aptamers, somamers for multiplex assays [15]. | Critical for the targeted verification and validation of candidate biomarker panels in biological samples. |

| Clinical Assays | Digital pathology platforms, regulated LIMS (Laboratory Information Management Systems), eQMS (electronic Quality Management Systems) [14]. | Facilitate the translation of discovered biomarkers into clinical-grade, regulated diagnostic tests. |

| 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate | 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate, CAS:206440-72-4, MF:C5H13O7P, MW:216.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Carteolol | Carteolol Hydrochloride | Carteolol is a non-selective beta-adrenergic antagonist for research applications. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

The field of biomarker discovery has undergone a profound transformation, shifting from a traditional focus on single molecules to a comprehensive multi-omics approach that integrates genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. This paradigm shift is driven by the recognition that complex diseases cannot be adequately understood or diagnosed through single-dimensional biological measurements [2]. The convergence of these omics technologies, framed within systems biology research, enables the development of robust biomarker panels that capture the full complexity of disease mechanisms and heterogeneity [17]. Modern biomarker discovery now leverages high-throughput technologies including next-generation sequencing (NGS), advanced mass spectrometry, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to generate massive molecular datasets that provide unprecedented insights into disease pathophysiology [18] [19].

The integration of multi-omics data represents more than just technological advancement; it embodies a fundamental change in how researchers approach biological complexity. Where single-omics approaches provided limited, often isolated insights, integrated multi-omics reveals the emergent properties that arise from interactions across molecular layers [17]. This systems-level perspective is particularly valuable for addressing diseases with complex etiology, such as cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and metabolic conditions, where perturbations at one molecular level create ripple effects across the entire biological network [20]. The resulting biomarker signatures therefore offer superior clinical utility for early diagnosis, prognosis, patient stratification, and therapeutic monitoring compared to traditional single-marker approaches [2] [17].

Comparative Analysis of Omics Technologies

Each omics technology provides unique insights into specific layers of biological organization, with distinct strengths, limitations, and applications in biomarker discovery. The following comparison outlines the fundamental characteristics, analytical outputs, and biomarker applications of the three primary omics technologies.

Table 1: Technology Comparison for Omics Approaches in Biomarker Discovery

| Feature | Genomics | Proteomics | Metabolomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Target | DNA sequences and variations [21] | Proteins, polypeptides, and post-translational modifications [2] [22] | Small-molecule metabolites (<1,500 Da) [19] |

| Primary Technologies | Next-generation sequencing (NGS), microarrays [18] [21] | Mass spectrometry (LC-MS, GC-MS), SOMAmer, Olink assays [19] [23] | GC-MS, LC-MS, NMR spectroscopy [19] |

| Key Biomarker Applications | Risk prediction, hereditary markers, companion diagnostics [2] [21] | Diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic biomarkers [2] [23] | Diagnostic, prognostic biomarkers, treatment response [2] [19] |

| Temporal Resolution | Static (with exceptions for epigenetic changes) | Medium (minutes to hours) | High (seconds to minutes) [19] |

| Throughput Capability | Very high (whole genomes in days) [18] | Medium to high (thousands of proteins) [23] | High (hundreds of metabolites) [19] |

| Proximity to Functional Phenotype | Low (potential) | Medium (effectors) | High (functional endpoints) [19] |

Table 2: Performance Metrics in Disease-Specific Biomarker Discovery

| Disease Area | Genomics Contribution | Proteomics Contribution | Metabolomics Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | Somatic mutations, copy number variations, gene fusions [18] [21] | Protein abundance, signaling pathways, tumor microenvironment [17] [21] | Altered energy metabolism (Warburg effect), oncometabolites [19] |

| Neurodegenerative Disorders | APOE ε4 carrier status, risk loci [23] | CSF and plasma tau, neurofilament light, neuroinflammation markers [23] | Energetic metabolism shifts, oxidative stress markers [19] |

| Cardiovascular Diseases | Polygenic risk scores [17] | Inflammatory cytokines, cardiac troponins, NT-proBNP [17] | Lipid species, fatty acids, acylcarnitines [19] [17] |

| Metabolic Disorders | Monogenic diabetes genes, T2D risk variants | Adipokines, inflammatory mediators [22] | Glucose, amino acids, organic acids, ketone bodies [19] |

The complementary nature of these technologies becomes evident when examining their respective positions in the central dogma of biology and their relationship to functional phenotypes. Genomics provides the blueprint of potential risk, identifying hereditary factors and predispositions that may contribute to disease development. Proteomics captures the functional effectors of biological processes, reflecting the actual machinery that executes cellular functions and responds to therapeutic interventions. Metabolomics offers the closest readout of functional phenotype, revealing the dynamic biochemical outputs that result from genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic activity [19]. This hierarchical relationship means that integrated multi-omics approaches can connect genetic predisposition through protein function to ultimate phenotypic manifestation, providing a comprehensive view of disease mechanisms that is inaccessible to any single omics approach.

Systems Biology Approaches for Multi-Omics Integration

The true power of modern biomarker discovery emerges not from individual omics technologies but from their integration through systems biology approaches. Multi-omics integration methodologies can be categorized into three primary strategies: early, intermediate, and late integration, each with distinct advantages for specific research applications [17].

Early integration, also known as data-level fusion, combines raw data from different omics platforms before statistical analysis. This approach maximizes information preservation but requires sophisticated normalization and scaling to handle different data types and measurement scales. Methods such as principal component analysis (PCA) and canonical correlation analysis (CCA) are commonly employed to manage the computational complexity of early integration strategies [17]. Intermediate integration (feature-level fusion) first identifies important features within each omics layer, then combines these refined signatures for joint analysis. This strategy balances information retention with computational feasibility and is particularly valuable for large-scale studies where early integration might be prohibitive. Network-based methods and pathway analysis often guide feature selection in intermediate integration [17]. Late integration (decision-level fusion) performs separate analyses within each omics layer and combines the resulting predictions using ensemble methods. While potentially missing subtle cross-omics interactions, this approach provides robustness against noise in individual omics layers and allows for modular analysis workflows [17].

Table 3: Multi-Omics Integration Methodologies and Applications

| Integration Method | Key Characteristics | Optimal Use Cases | Common Algorithms/Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration | Combines raw data; maximal information; computationally intensive [17] | Discovery-phase analysis with sufficient sample size and computational resources [17] | PCA, CCA, MOFA [17] [21] |

| Intermediate Integration | Identifies features within layers before integration; balances complexity and information [17] | Large-scale studies; pathway-focused analysis; network biology [17] | mixOmics, network propagation, WGCNA [17] [20] |

| Late Integration | Combines results from separate analyses; robust to noise; modular workflow [17] | Clinical applications; validation studies; heterogeneous data sources [17] | Ensemble methods, weighted voting, meta-learning [17] |

| Network-Based Integration | Incorporates biological interaction knowledge; high interpretability [17] [20] | Mechanism-focused studies; therapeutic target identification [20] | Cytoscape, STRING, graph neural networks [17] [21] |

The integration of multi-omics data faces several significant technical challenges that require specialized computational approaches. Data heterogeneity arises from different data types, scales, distributions, and noise characteristics across omics platforms, necessitating sophisticated normalization strategies such as quantile normalization and z-score standardization [17]. The "curse of dimensionality" – where studies involve thousands of molecular features measured across relatively few samples – requires specialized machine learning approaches including regularization techniques like elastic net regression and sparse partial least squares [17]. Additionally, missing data and batch effects from different measurement platforms must be addressed through advanced imputation methods and batch correction approaches such as ComBat and surrogate variable analysis [17].

Multi-Omics Data Integration Workflow

Machine learning and artificial intelligence have become indispensable for multi-omics integration, with random forests and gradient boosting methods excelling at handling mixed data types and non-linear relationships common in these datasets [18] [17]. Deep learning architectures, particularly autoencoders and multi-modal neural networks, can automatically learn complex patterns across omics layers without requiring explicit integration strategies [17]. For biologically meaningful integration, network approaches model molecular interactions within and between omics layers, with graph neural networks and network propagation algorithms leveraging known biological relationships to guide multi-omics analysis [17] [20]. Tensor factorization techniques naturally handle multi-dimensional omics data by decomposing complex datasets into interpretable components, using methods such as non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) and independent component analysis (ICA) to discover novel biomarker patterns [17].

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Validation

The validation of biomarker panels discovered through multi-omics approaches requires rigorous experimental methodologies and analytical frameworks. The following section outlines detailed protocols for biomarker verification and validation across different omics technologies, with emphasis on systems biology approaches.

Proteomic Biomarker Validation Protocol

The Global Neurodegeneration Proteomics Consortium (GNPC) has established one of the most comprehensive proteomic biomarker validation frameworks, analyzing approximately 250 million unique protein measurements from over 35,000 biofluid samples [23]. Their large-scale validation protocol involves:

Sample Preparation: Plasma, serum, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples are collected using standardized protocols across multiple clinical sites. Samples undergo protein extraction and quantification with quality control measures including protein concentration assessment and integrity verification [23].

Multi-Platform Proteomic Profiling: Each sample is analyzed using complementary technologies:

- SOMAmer-based Capture Array (SomaScan versions 3, 4, and 4.1): Measures between 1,300 and 7,000 unique protein aptamers per biosample to ensure broad proteome coverage [23].

- Olink Proximity Extension Assay: Provides complementary protein quantification with high specificity and sensitivity [23].

- Tandem Mass Tag Mass Spectrometry: Applied to a subset of samples (1,975 samples in GNPC V1) for cross-platform validation and identification of protein isoforms and post-translational modifications [23].

Data Harmonization and Quality Control: Data from multiple platforms and cohorts are aggregated and harmonized using the Alzheimer's Disease Data Initiative's AD Workbench, a secure cloud-based environment that satisfies GDPR and HIPAA requirements [23].

Differential Abundance Analysis: Statistical analysis identifies disease-specific differential protein abundance using linear mixed-effects models that account for covariates including age, sex, and technical variables [23].

Transdiagnostic Signature Identification: Machine learning algorithms (including regularized regression and ensemble methods) identify proteomic signatures that transcend traditional diagnostic boundaries, revealing shared pathways across neurodegenerative conditions [23].

Metabolomic Biomarker Workflow

Metabolomic biomarker validation employs both targeted and untargeted approaches, with specific protocols tailored to the analytical technology:

Sample Preparation for Mass Spectrometry:

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS): Proteins are precipitated from biofluids using cold organic solvents (typically methanol or acetonitrile). The supernatant is dried under nitrogen and reconstituted in mobile phase compatible solvents [19].

- Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS): Metabolites undergo derivatization using methoxyamine hydrochloride and N-Methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (MSTFA) to increase volatility and thermal stability [19].

Instrumental Analysis:

- LC-MS Analysis: Utilizes reversed-phase chromatography with gradient elution coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometers (Q-TOF or Orbitrap instruments). Electrospray ionization (ESI) is applied in both positive and negative ionization modes to maximize metabolite coverage [19].

- GC-MS Analysis: Employes capillary GC columns with temperature ramping, coupled to electron impact (EI) or chemical ionization (CI) sources. Mass detection typically uses quadrupole or time-of-flight (TOF) analyzers [19].

- NMR Spectroscopy: Requires minimal sample preparation, with biofluids typically diluted in deuterated solvents. 1D ^1H NMR spectra are acquired with water suppression, and 2D experiments (J-resolved, COSY, HSQC) are used for metabolite identification [19].

Data Processing and Metabolite Identification:

- Raw data from MS platforms undergo peak detection, alignment, and normalization using software such as XCMS, MZmine, or Progenesis QI [19].

- Multivariate statistical analysis including principal component analysis (PCA) and partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) identifies differentially abundant metabolites [19].

- Metabolite identification is performed by matching accurate mass, retention time, and fragmentation spectra to authentic standards in databases such as HMDB, MetLin, or NIST [19].

Cross-Omics Validation Framework

Systems biology approaches for validating integrated biomarker panels require specialized computational and statistical frameworks:

Network-Based Integration: Biomarker candidates from individual omics layers are mapped onto biological networks including protein-protein interaction networks, metabolic pathways, and gene regulatory networks using platforms such as Cytoscape, STRING, or custom pipelines like ADOPHIN [20] [21]. This approach identifies topologically important nodes with regulatory significance across multiple molecular layers [20].

Machine Learning Validation: Multi-omics biomarker signatures are validated using nested cross-validation approaches to prevent overfitting. The process includes:

- Feature selection using regularization methods (LASSO, elastic net) to identify the most predictive biomarkers from the high-dimensional multi-omics data [17] [21].

- Model training with algorithms including random forests, support vector machines, or gradient boosting machines optimized for mixed data types [17] [21].

- Performance assessment using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, calibration curves, and decision curve analysis to evaluate clinical utility [17].

Independent Cohort Validation: Biomarker panels are validated in external cohorts to assess generalizability. The GNPC framework, for example, validates proteomic signatures across 23 independent cohorts comprising over 18,000 participants [23].

Systems Biology Validation Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of omics technologies for biomarker discovery requires specialized reagents, platforms, and computational tools. The following table summarizes essential resources for multi-omics biomarker research.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Omics Biomarker Discovery

| Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq X [18], Oxford Nanopore [18] | Whole genome sequencing, targeted gene panels, epigenomics | High-throughput, long-read capabilities, methylation detection [18] |

| Proteomic Technologies | SomaScan [23], Olink [23], LC-MS/MS [19] [23] | High-throughput protein quantification, post-translational modifications | High plex capacity (7,000 proteins), high sensitivity, isoform resolution [23] |

| Metabolomic Platforms | GC-MS [19], LC-MS [19], NMR [19] | Untargeted and targeted metabolite profiling, metabolic pathway analysis | Broad metabolite coverage, structural elucidation, quantitative accuracy [19] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | GATK [21], DESeq2 [21], MaxQuant [21], mixOmics [17] | Variant calling, differential expression, multi-omics integration | Industry-standard pipelines, specialized for omics data types [17] [21] |

| Multi-Omics Integration | MOFA [17], Cytoscape [21], cBioPortal [21] | Data integration, network visualization, interactive exploration | Factor analysis, biological network integration, user-friendly interface [17] [21] |

| Preclinical Models | Patient-derived organoids [24], PDX models [24] | Biomarker validation, therapeutic response assessment | Clinically relevant biology, patient-specific responses [24] |

| Diclobutrazol | Diclobutrazol, CAS:66345-62-8, MF:C15H19Cl2N3O, MW:328.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Apricitabine | Apricitabine, CAS:143338-12-9, MF:C8H11N3O3S, MW:229.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Cloud computing platforms have become essential infrastructure for multi-omics biomarker discovery, with services including Amazon Web Services (AWS), Google Cloud Genomics, and Microsoft Azure providing scalable resources for data storage and analysis [18]. These platforms offer specialized solutions for genomic data analysis while ensuring compliance with regulatory requirements such as HIPAA and GDPR [18]. The implementation of FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles is particularly important for multi-omics research, facilitating data sharing and method comparison through standardized approaches to data generation, processing, and analysis [17].

Specialized computational tools have been developed specifically for multi-omics integration, with packages such as mixOmics providing statistical frameworks for integration, MOFA (Multi-Omics Factor Analysis) enabling dimensionality reduction across omics layers, and MultiAssayExperiment facilitating data management for complex multi-omics datasets [17]. For network-based integration, platforms including Cytoscape, STRING, and ADOPHIN enable mapping of multi-omics data onto biological networks to identify topologically important nodes with regulatory significance [20] [21].

The integration of genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics through systems biology approaches represents the future of biomarker discovery and validation. While each omics technology provides valuable insights individually, their integration creates synergistic value that far exceeds the sum of their parts. Multi-omics biomarker signatures have demonstrated superior performance across multiple disease areas, with integrated approaches significantly outperforming single-biomarker methods and achieving diagnostic accuracies exceeding 95% in some neurodegenerative disease studies [17] [23]. The transition from single-omics to multi-omics approaches reflects an evolving understanding of disease as a systems-level phenomenon that manifests through coordinated changes across molecular scales.

Despite these advances, significant challenges remain in translating multi-omics biomarker panels into clinically actionable tools. Regulatory agencies are developing specific frameworks for evaluating multi-omics biomarkers, with emphasis on analytical validation, clinical utility, and cost-effectiveness demonstration [17]. The successful clinical implementation of these complex signatures requires careful consideration of workflow integration, staff training, and technology infrastructure [17]. Future directions in the field include the development of single-cell multi-omics technologies that resolve cellular heterogeneity, advanced AI and machine learning algorithms for pattern recognition in high-dimensional data, and streamlined regulatory pathways for biomarker panel qualification [17] [21]. As these technologies mature and integration methodologies become more sophisticated, multi-omics biomarker panels will increasingly guide personalized therapeutic strategies, enhance clinical trial design, and ultimately improve patient outcomes across a broad spectrum of diseases.

Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a devastating malignancy, projected to become the third leading cause of global cancer deaths, with a five-year survival rate below 7% for most patients [25] [26]. The poor prognosis stems primarily from late-stage diagnosis, with only 10-20% of patients presenting with surgically resectable disease at detection [27] [25]. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) remains the most widely used serum biomarker but suffers from limited specificity (68-91%) and sensitivity (70-90%), with elevated levels also occurring in various benign conditions such as chronic pancreatitis [27] [25]. Furthermore, CA19-9 is ineffective in Lewis antigen-negative populations, potentially leading to misdiagnosis in up to 30% of PDAC patients [25]. These critical limitations have driven the search for more reliable diagnostic biomarkers, particularly those capable of detecting PDAC at earlier, more treatable stages.

Autoantibodies (AAbs) have emerged as promising biomarker candidates due to their early appearance in disease pathogenesis, stability in serum, and ability to report on underlying cellular perturbations within the tumor microenvironment [25] [28]. The immune system produces AAbs against tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) that arise from aberrant protein expression, mutations, or abnormal post-translational modifications in cancer cells [29]. Cancer-testis (CT) antigens are particularly attractive targets, as they exhibit highly restricted expression in normal adult tissues but are aberrantly expressed in various cancers, potentially triggering detectable humoral immune responses [25]. This case study examines the discovery and validation of a novel autoantibody panel for PDAC detection, contextualized within a systems biology framework for biomarker validation.

Experimental Design and Workflow

Study Populations and Cohort Design

The discovery and validation of the AAb panel followed a multi-phase approach involving independent patient cohorts [25]. The training cohort comprised 94 individuals, including 19 PDAC patients (Stage II-III), 20 chronic pancreatitis (CP) patients, 1 other pancreatic cancer (PC) patient, 13 dyspeptic ulcer (DYS) patients, 7 healthy controls (HCs), plus 18 additional PC and 16 prostate cancer (PRC) samples from collaborating institutions. This diverse training set enabled initial biomarker identification while assessing specificity against confounding conditions.

The validation cohort included 223 samples to rigorously evaluate clinical utility: 98 PDAC (Stage II-III), 65 other pancreatic cancers (Stage II-III), 20 prostate cancers (PRC), 16 colorectal cancers (CRC), and 24 healthy controls. This expansive validation design allowed assessment of diagnostic performance across multiple comparison scenarios: PDAC versus healthy controls, PDAC versus benign pancreatic conditions, and PDAC versus other cancer types [25].

Table 1: Study Cohort Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| Cohort | PDAC | Chronic Pancreatitis | Other Pancreatic Cancers | Other Cancers | Healthy Controls | Dyspepsia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | 19 | 20 | 19 | 16 (prostate) | 7 | 13 |

| Validation | 98 | - | 65 | 36 (20 prostate, 16 colorectal) | 24 | - |

High-Throughput Autoantibody Profiling Technology

CT100+ Protein Microarray Fabrication

The core discovery platform utilized a custom CT100+ protein microarray containing 113 cancer-testis or tumor-associated antigens [25]. These antigen lysates were diluted two-fold with 40% sucrose and printed in a 4-plex format (four replica arrays per slide) on streptavidin-coated hydrogel microarray substrates. Within each array, antigens were printed in technical triplicate to ensure measurement reliability. Following printing, slides were incubated in blocking buffer for one hour at room temperature before serological application.

Serum Processing and Hybridization

Blood samples were collected from all participants and processed under standardized conditions [25]. Serum was isolated by centrifugation at 1500 × g for 15 minutes at 22°C, followed by a second centrifugation at 3500 × g for 15 minutes to remove platelets. The supernatant was aliquoted into polypropylene tubes and stored at -80°C until analysis. For hybridization, serum samples were applied to the microarrays to detect autoantibodies bound to specific antigens, with subsequent detection using fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies.

Biomarker Identification and Validation Workflow

The overall research strategy followed a comprehensive workflow from discovery through validation:

Results: Diagnostic Performance of the Autoantibody Panel

Optimal Autoantibody Panel Identification

Combinatorial ROC curve analysis of the training cohort data identified an optimal seven-autoantibody panel comprising CEACAM1, DPPA2, DPPA3, MAGEA4, SRC, TPBG, and XAGE3 [25] [26]. This combination demonstrated robust diagnostic performance with an area under the curve (AUC) of 85.0%, sensitivity of 82.8%, and specificity of 68.4% for distinguishing PDAC from controls in the training cohort.

Differential expression analysis further identified four additional biomarkers (ALX1, GPA33, LIP1, and SUB1) that were upregulated in PDAC against both diseased and healthy controls [25]. These were incorporated into an expanded 11-AAb panel for subsequent validation studies. The identified AAbs were further validated using public immunohistochemistry datasets and experimentally confirmed using a custom PDAC protein microarray containing the 11 optimal AAb biomarkers.

Validation Performance Across Multiple Comparison Scenarios

The clinical utility of the biomarker panel was rigorously assessed in the independent validation cohort of 223 samples [25]. The results demonstrated consistently strong performance across multiple clinically relevant scenarios:

Table 2: Diagnostic Performance of AAb Panel in Validation Cohort

| Comparison Scenario | AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity | Key Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDAC vs Healthy Controls | 80.9% | - | - | Distinguishing cancer from healthy individuals |

| PDAC vs Other Pancreatic Cancers | 70.3% | - | - | Subtype differentiation within pancreatic malignancies |

| PDAC vs Colorectal Cancer | 84.3% | - | - | Specificity against gastrointestinal cancers |

| PDAC vs Prostate Cancer | 80.2% | - | - | Specificity against non-GI malignancies |

The specific seven-autoantibody combination (CEACAM1-DPPA2-DPPA3-MAGEA4-SRC-TPBG-XAGE3) maintained its performance in the validation cohort with an AUC of 85.0%, confirming the robustness of the initial findings [25] [26].

Comparative Performance Against Existing Biomarkers

When compared to the current clinical standard, CA19-9, the autoantibody panel demonstrated complementary strengths. A separate study developing a serum protein biomarker panel using machine learning approaches reported that while CA19-9 alone achieved an AUROC of 0.952 for detecting PDAC across all stages, this performance dropped to 0.868 for early-stage PDAC [27]. Their machine learning-integrated protein panel (including CA19-9, GDF15, and suPAR as key biomarkers) significantly outperformed CA19-9 alone, achieving AUROCs of 0.992 for all-stage PDAC and 0.976 for early-stage PDAC [27].

Another independent study identified a different three-AAb panel (anti-HEXB, anti-TXLNA, anti-SLAMF6) that achieved AUCs of 0.81 for distinguishing PDAC from normal controls and 0.80 for distinguishing PDAC from benign pancreatic diseases [28]. Notably, when this immunodiagnostic model was combined with CA19-9, the positive rate of PDAC detection increased to 92.91%, suggesting synergistic value in combining autoantibody panels with existing protein biomarkers [28].

Systems Biology Framework for Biomarker Validation

Biological Plausibility and Pathway Analysis

The validation of biomarker panels within a systems biology framework requires establishing biological plausibility beyond statistical associations [2]. The identified autoantibodies in the PDAC panel target antigens with established roles in oncogenic processes. For instance, MAGEA4 belongs to the cancer-testis antigen family with highly restricted expression in normal tissues but aberrant expression in various cancers [25]. SRC is a proto-oncogene involved in multiple signaling pathways regulating cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival. CEACAM1 (carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1) participates in cell adhesion and signaling processes frequently dysregulated in malignancies.

A biological function-based optimization process, as demonstrated in sepsis biomarker development, can strengthen panel validation by ensuring selected biomarkers represent core dysregulated biological processes in the disease [30]. This approach operates on the premise that highly correlated genes involved in the same biological processes share similar discriminatory power, allowing for substitution of poorly performing biomarkers with functionally equivalent alternatives without compromising diagnostic performance.

Integration with Multi-Omics Approaches

Systems biology integrates multiple data types across genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, and proteomics to identify optimal biomarker combinations [27] [2]. The rising importance of this approach is reflected in the shift from single-marker to multi-marker panels, which offer higher robustness and separation power for clinical tests [2]. Autoantibody panels represent one component within this multi-omics landscape, with each biomarker class offering distinct advantages:

Table 3: Multi-Omics Biomarker Classes in PDAC Detection

| Biomarker Class | Common Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic (DNA) | Risk prediction, therapy selection | Stable molecules, well-established protocols | Limited dynamic range, may not reflect current disease state |

| Transcriptomic (RNA) | Diagnosis, prognosis, physiological states | Dynamic response, pathway information | Technical variability, sample stability issues |

| Proteomic (Proteins) | Diagnosis, prognosis, treatment monitoring | Direct functional molecules, post-translational modifications | Measurement complexity, dynamic range challenges |

| Autoantibodies (AAbs) | Early detection, diagnosis | Early emergence, persistence, stability, specificity | Variable frequency in patient populations |

Analytical Validation Considerations

The transition from discovery to clinically applicable assays presents technical challenges, particularly when moving between measurement platforms [30]. The biological function-based optimization approach has demonstrated that substituting poorly performing features with biologically equivalent alternatives can maintain diagnostic performance while facilitating platform transition [30]. This principle supports the robustness of the identified AAb panel across different experimental conditions and measurement technologies.

Research Reagent Solutions for AAb Biomarker Studies

The experimental workflow for autoantibody biomarker discovery and validation requires specialized reagents and platforms. The following table outlines key research solutions employed in these studies:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Autoantibody Biomarker Studies

| Research Reagent | Specific Example | Function in Experiment | Application in PDAC AAb Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Microarray | CT100+ custom microarray [25] | High-throughput AAb profiling | Screening of 113 CT antigens against serum samples |

| Protein Microarray | HuProt Human Proteome Microarray [28] | Comprehensive proteome-wide AAb detection | Identification of 167 candidate TAAbs in discovery phase |

| Antigen Substrates | Recombinant CT antigens [25] | Target for AAb binding | CEACAM1, DPPA2, DPPA3, MAGEA4, SRC, TPBG, XAGE3 |

| Detection Antibodies | HRP-labeled anti-human IgG [28] | Secondary detection of bound AAbs | ELISA validation of identified TAAbs |

| Assay Platform | Luminex xMAP immunoassays [27] | Multiplex protein quantification | Validation of protein biomarkers in parallel studies |

| Sample Processing | Streptavidin-coated hydrogel substrates [25] | Microarray surface chemistry | Fabrication of protein microarrays for AAb screening |

This case study demonstrates that autoantibody panels represent promising diagnostic biomarkers for PDAC, with the identified 7-AAb panel (CEACAM1-DPPA2-DPPA3-MAGEA4-SRC-TPBG-XAGE3) achieving 85.0% AUC in independent validation [25] [26]. The performance across multiple comparison scenarios (PDAC vs. healthy controls: 80.9% AUC; PDAC vs. other cancers: 70.3-84.3% AUC) indicates robust discriminatory capability [25].

The systems biology framework for biomarker validation emphasizes the importance of biological plausibility, multi-omics integration, and analytical robustness [2] [30]. The biological relevance of the target antigens strengthens the case for the clinical potential of this AAb panel. Furthermore, evidence from multiple studies suggests that combining autoantibody signatures with existing biomarkers like CA19-9 can significantly enhance detection rates [28] [31], with one meta-analysis reporting that certain AAb combinations with CA19-9 achieved 100% sensitivity and 92% specificity [31].

Future development of this AAb panel should focus on validation in broader screening populations, including high-risk individuals, and further refinement through integration with other biomarker classes within a comprehensive multi-omics strategy. The transition to clinically applicable assays will benefit from continued optimization based on biological principles to maintain performance while improving feasibility for routine clinical implementation.

Building the Validation Pipeline: Integrating Experimental and Computational Workflows

The validation of biomarker panels is a cornerstone of systems biology research, providing critical insights into disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Within this framework, high-throughput proteomic technologies are indispensable for the simultaneous identification and quantification of numerous candidate biomarkers. Protein microarrays and mass spectrometry have emerged as two leading platforms, each with distinct operational principles, strengths, and limitations. Protein microarrays, featured as miniaturized, parallel assay systems, enable the high-throughput analysis of thousands of proteins from minute sample volumes [32]. Their design is ideally suited for profiling complex biological systems. Mass spectrometry (MS), conversely, offers antibody-independent quantification of proteins, often with high specificity and the ability to detect post-translational modifications [33] [34]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these platforms, focusing on their performance in biomarker quantification and their role in validating biomarker panels within systems biology.

Protein Microarray Platforms

Protein microarrays are characterized by their high-density format, where hundreds to thousands of proteins or capture agents are immobilized on a solid surface in a miniaturized layout [32] [35]. According to their application and design, they are primarily categorized into three types.

Analytical Microarrays: These arrays use defined capture agents, such as antibodies, immobilized on the surface to detect proteins from a complex sample. They are primarily used for protein expression profiling and biomarker detection [35]. A key advantage is their high sensitivity and suitability for clinical applications, though they can be limited by the availability and quality of specific antibodies [35].

Reverse Phase Protein Arrays (RPPA): In RPPA formats, the samples themselves (such as cell or tissue lysates) are printed onto the array surface. These are then probed with specific antibodies against the target proteins [32] [35]. This method is particularly powerful for signaling pathway analysis and monitoring post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation) from minimal sample material, making it valuable for personalized medicine approaches [32] [35]. Its main limitation is the number of analytes that can be measured, restricted by the availability of specific and validated antibodies [35].

Functional Protein Microarrays: These are constructed with full-length proteins or protein domains and are used to study a wide range of biochemical activities, including protein-protein, protein-lipid, and protein-drug interactions [32] [35]. A prominent subtype is the proteome microarray, which contains most or all of an organism's proteins, enabling unbiased discovery research [32]. For instance, yeast proteome microarrays have been successfully used for a large-scale "Phosphorylome Project," identifying thousands of kinase-substrate relationships [32].

Mass Spectrometry Platforms

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics does not rely on pre-defined capture molecules and can provide absolute quantification of proteins. It is typically divided into discovery and targeted workflows.

Discovery Proteomics (DIA/DDA): These untargeted or data-independent acquisition methods aim to measure as many proteins as possible in a single run. Advanced platforms, such as those using nanoparticle-based enrichment (e.g., Seer Proteograph) or high-abundance protein (HAP) depletion (e.g., Biognosys TrueDiscovery), have significantly increased coverage of the plasma proteome, identifying thousands of proteins [34]. These methods are ideal for initial biomarker discovery but can be challenged by the wide dynamic range of protein concentrations in biofluids like plasma [34].

Targeted Proteomics (e.g., PRM, SRM): Targeted methods, such as Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) or Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM), focus on precise quantification of a pre-selected set of proteins [33] [36]. These are considered a "gold standard" for verification and validation due to high reliability, reproducibility, and absolute quantification via internal standards [34] [36]. A key application is the multiplexed quantification of specific biomarker panels, such as phosphorylated tau proteins in Alzheimer's disease [33].

Direct Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes a direct comparison of key performance metrics for protein microarray and mass spectrometry platforms, based on data from recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Proteomic Platforms

| Performance Metric | Analytical Protein Microarray | Reverse Phase Protein Array (RPA) | Discovery Mass Spectrometry | Targeted Mass Spectrometry |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput | High | High | Moderate | High for targeted panels |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Hundreds to thousands of targets | Limited by antibody availability | >5,000 proteins per run [34] | Dozens to hundreds of targets |

| Sample Consumption | Low (1-2 µL) [37] | Very low | Moderate | Low to moderate |

| Sensitivity | High (depends on antibody) | High (depends on antibody) | Moderate to High (platform-dependent) | Very High (fmol/mL range) [33] |

| Quantification Type | Relative (fluorescence) | Relative (fluorescence) | Relative or Absolute | Absolute with internal standards [34] |

| Key Advantage | High-throughput, established workflows | Ideal for phospho-signaling analysis | Unbiased, broad proteome coverage | High specificity and accuracy |

| Key Limitation | Dependent on antibody quality/availability | Limited analyte number | Complex data analysis, dynamic range challenges | Requires pre-selection of targets |

A 2024 study directly compared immunoassay-based (a form of analytical microarray) and mass spectrometry-based quantification of phosphorylated tau (p-tau) biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease [33]. The results showed that for p-tau217, mass spectrometry and immunoassays were highly comparable in diagnostic performance, effect sizes, and associations with PET biomarkers [33]. However, for p-tau181 and p-tau231, antibody-free mass spectrometry exhibited slightly lower performance compared to established immunoassays [33]. This underscores that performance can be analyte-specific.

A broader 2025 comparison of eight plasma proteomics platforms further highlights trade-offs. Affinity-based platforms like SomaScan (11K assays) and Olink (5K assays) offer exceptional throughput and sensitivity, measuring thousands of proteins from small samples [34]. Mass spectrometry platforms, while sometimes offering lower coverage, provide unique advantages in specificity (by measuring multiple peptides per protein) and independence from binding reagent availability [34].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protein Microarray Workflow: Serological Biomarker Discovery

A standard protocol for identifying serological biomarkers using a functional proteome microarray is exemplified by work with the vaccinia virus [37].

- Step 1: Microarray Fabrication. The process begins with the PCR amplification of all open reading frames (ORFs) from the pathogen's genome. These ORFs are cloned into an expression system, such as baculovirus, to produce full-length, GST-tagged recombinant proteins. Proteins are then affinity-purified and printed in a high-density format onto nitrocellulose-coated glass slides [37].

- Step 2: Probing and Assay. The microarray is incubated with a diluted serum sample (e.g., from infected or vaccinated individuals). After washing to remove unbound components, target antibodies bound to arrayed antigens are detected using a fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody (e.g., anti-human IgG) [37].

- Step 3: Data Acquisition and Analysis. The array is scanned with a confocal laser scanner (e.g., GenePix) to generate a quantitative fluorescence image. Signal intensities are extracted, and antigens with significant reactivity are identified by comparing to control sera [37]. This workflow successfully identified a small subset of the vaccinia proteome that was consistently recognized by antibodies from immune individuals [37].

Mass Spectrometry Workflow: Quantification of CSF Biomarkers

A detailed protocol for mass spectrometry-based quantification of biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was used in a 2024 study comparing p-tau biomarkers [33].

- Step 1: Sample Preparation. A CSF sample (250 µL) is spiked with a known amount of heavy isotope-labeled peptide standards (AQUA peptides) for absolute quantification. Proteins are precipitated using perchloric acid, which leaves tau protein in the supernatant. The supernatant is then processed using solid-phase extraction (SPE) to purify the peptides [33].

- Step 2: Digestion and LC-MS/MS Analysis. The extracted proteins are reconstituted and digested with trypsin overnight at 37°C to generate peptides. The resulting peptides are separated by liquid chromatography (LC) and analyzed by a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Hybrid Orbitrap) operated in Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) mode for targeted quantification [33].

- Step 3: Data Processing. The LC-MS data is processed using software like Skyline. The quantification is achieved by comparing the peak areas of the native target peptides to the peak areas of their corresponding heavy labeled internal standards. This allows for the precise calculation of the concentration of specific p-tau variants (e.g., p-tau181, p-tau217) [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of experiments using these high-throughput platforms requires specific, high-quality reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions used in the featured protocols.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Biomarker Quantification

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Proteins | Serve as immobilized antigens or quantitative standards. | Fabrication of functional proteome microarrays for pathogen immunoprofilng [37]. |

| Heavy Isotope-Labeled Peptide Standards (AQUA) | Enable absolute quantification by mass spectrometry; act as internal controls. | Precise measurement of p-tau181, p-tau217, and p-tau231 concentrations in CSF [33]. |

| Specific Antibodies | Act as capture (analytical microarray) or detection (RPA) agents. | Probing reverse-phase protein arrays to analyze cell signaling pathways [32] [35]. |

| Fluorophore-Conjugated Secondary Antibodies | Detect target binding interactions on microarrays via fluorescence. | Visualizing human IgG binding to viral antigens on a proteome microarray [37]. |

| Cell-Free Expression System | Enables on-site protein synthesis for functional microarrays. | Used in NAPPA (Nucleic Acid Programmable Protein Array) to produce proteins directly on the slide [35]. |

| Nitrocellulose-Coated Slides | Provide a high-binding-capacity surface for protein immobilization. | Standard substrate for printing protein microarrays to ensure optimal protein retention [37]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Plates | Purify and concentrate peptides from complex biological samples prior to MS. | Sample clean-up in the mass spectrometry workflow for CSF biomarkers [33]. |

| Oleandrigenin | Oleandrigenin, CAS:465-15-6, MF:C25H36O6, MW:432.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hydroxynybomycin | Hydroxynybomycin, CAS:63582-81-0, MF:C16H14N2O5, MW:314.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Both protein microarrays and mass spectrometry are powerful platforms for biomarker quantification, each occupying a complementary niche in the systems biology workflow. The choice between them depends on the specific research question, the required throughput, the need for antibody-independent validation, and the available sample type and volume. Protein microarrays excel in high-throughput, targeted screening of known antigens or antibodies, making them ideal for comprehensive immunoprofiling and signaling network analysis. Mass spectrometry offers unparalleled specificity and the ability to perform unbiased discovery and absolute quantification without antibodies, which is crucial for validating novel biomarker panels.

Within the broader thesis of validating biomarker panels using systems biology, these technologies are not mutually exclusive but are increasingly used in concert. A discovery phase using broad proteome microarrays or discovery MS can identify a candidate biomarker panel, which is then transitioned to a robust, targeted MS or analytical microarray platform for high-throughput validation in larger clinical cohorts [32] [36]. This integrated, multi-platform approach leverages the respective strengths of each technology to build a systems-level understanding of disease pathophysiology and to translate proteomic discoveries into clinically actionable diagnostic tools.

The Role of Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM) for Targeted Biomarker Validation

In the framework of systems biology, the validation of biomarker panels is a critical step in translating complex molecular discoveries into clinically actionable tools. Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM), also referred to as Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM), is a targeted mass spectrometry technique that has established itself as a cornerstone for precise, sensitive, and reproducible protein quantification in complex biological mixtures [38] [39]. This technique provides the rigorous analytical validation required to confirm the presence and concentration of candidate biomarkers, moving beyond discovery-phase findings to generate highly reliable data suitable for downstream clinical application and drug development.

SRM operates on triple quadrupole mass spectrometers, where it isolates a specific precursor ion from a target peptide in the first quadrupole (Q1), fragments it in the second quadrupole (q2), and monitors one or more predefined fragment ions (transitions) in the third quadrupole (Q3) [39]. This targeted detection method minimizes background interference, resulting in exceptional sensitivity and quantitative accuracy. For systems biology research, which seeks to understand biological systems as integrated networks, SRM offers a powerful method for validating multiplexed biomarker panels across diverse sample types, from plasma and tissue to microsamples [40]. Its ability to absolutely quantify dozens of proteins simultaneously in a single run makes it ideally suited for verifying systems-level hypotheses and validating molecular signatures identified through untargeted omics approaches.

SRM vs. Alternative Targeted MS Techniques

Technical Comparison of SRM and PRM

While SRM is a well-established workhorse for targeted quantification, Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) has emerged as a powerful alternative leveraging high-resolution mass spectrometry. Understanding their distinct technical profiles enables researchers to select the optimal approach for specific biomarker validation projects.

Table 1: Core Technical Comparison of SRM and PRM

| Feature | SRM/MRM | PRM |

|---|---|---|

| Instrumentation | Triple Quadrupole (QQQ) | Orbitrap, Q-TOF |

| Resolution | Unit Resolution | High (HRAM) |

| Fragment Ion Monitoring | Predefined transitions (e.g., 3-5) | Full MS/MS spectrum (all fragments) |

| Selectivity | Moderate | High (less interference) |

| Sensitivity | Very High | High, depending on resolution |