Systems Biology: From Core Concepts to Clinical Applications in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of systems biology, an interdisciplinary field that uses a holistic approach to understand complex biological systems.

Systems Biology: From Core Concepts to Clinical Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of systems biology, an interdisciplinary field that uses a holistic approach to understand complex biological systems. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles like holism and emergent properties, explores key methodological approaches including multi-omics integration and mathematical modeling, and discusses applications in personalized medicine and drug discovery. It also addresses critical challenges in data integration and model validation, and concludes by examining the field's transformative potential in biomedical research through its integration with pharmacology and regenerative medicine.

Understanding Systems Biology: A Holistic Framework for Complex Biological Systems

Systems biology represents a fundamental shift in biological research, moving from a traditional reductionist paradigm to a holistic one. Where reductionism focuses on isolating and studying individual components, such as a single gene or protein, systems biology seeks to understand how these components work together as an integrated system to produce complex behaviors [1] [2]. This approach acknowledges that "the system is more than the sum of its parts" and that biological functions emerge from the dynamic interactions among molecular constituents [1] [3].

The difference between these paradigms is profound. The reductionist approach has successfully identified most biological components but offers limited methods to understand how system properties emerge. In contrast, systems biology addresses the "pluralism of causes and effects in biological networks" by observing multiple components simultaneously through quantitative measures and rigorous data integration with mathematical models [3]. This methodology requires changing our scientific philosophy "in the full sense of the term," focusing on integration rather than separation [3].

Core Principles and Conceptual Framework

The Holistic Paradigm in Practice

Systems biology operates on several interconnected principles. First, it utilizes computational and mathematical modeling to analyze complex biological systems, recognizing that mathematics is essential for capturing the concepts and potential of biological systems [3] [4]. Second, it depends on high-throughput technologies ('omics') that provide system-wide datasets, including genomics, proteomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics [3] [4]. Third, it emphasizes data integration across these different biological layers to construct comprehensive models [2] [3].

The field follows a cyclical research process of theory, computational modeling to propose testable hypotheses, experimental validation, and then using newly acquired quantitative data to refine models [3]. This iterative process helps researchers uncover emergent properties—system behaviors that cannot be predicted from studying individual components alone [3].

Computational and Mathematical Foundations

Mathematical modeling provides the language for describing system dynamics in systems biology. Quantitative models range from bottom-up mechanistic models built from detailed molecular knowledge to top-down models inferred from large-scale 'omics' data [3]. These models enable researchers to simulate system behavior under various conditions, predict responses to perturbations, and identify key control points in biological networks.

The computational framework often involves graph-based representations where biological entities (genes, proteins, metabolites) form nodes and their interactions form edges [5]. This natural representation of biological networks facilitates efficient data traversal and exploration, making graph databases particularly suitable for systems biology applications [5].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Reductionist vs. Systems Biology Approaches

| Characteristic | Reductionist Biology | Systems Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Individual components | Interactions and networks |

| Methodology | Isolate and separate | Integrate and connect |

| Data Type | Targeted measurements | High-throughput, system-wide |

| Modeling Approach | Qualitative description | Quantitative, mathematical |

| Understanding | Parts in isolation | Emergent system properties |

Fundamental Methodologies in Systems Biology

Analytical Approaches: Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up

Systems biology employs two complementary methodological approaches:

The top-down approach begins with a global perspective by analyzing genome-wide experimental data to identify molecular interaction networks through correlated behaviors [3]. This method starts with an overarching view of system behavior and works downward to reveal underlying mechanisms, prioritizing overall system states and computational principles that govern global system dynamics [3]. It is particularly valuable for discovering novel molecular mechanisms through correlation analysis.

The bottom-up approach begins with detailed mechanistic knowledge of individual components and their interactions, then builds upward to understand system-level functionality [3]. This method infers functional characteristics that emerge from well-characterized subsystems by developing interactive behaviors for each component process and integrating these formulations to understand overall system behavior [3]. It is especially powerful for translating in vitro findings to in vivo contexts, such as in drug development.

Data Integration and Modeling Techniques

A crucial innovation in systems biology is the formalized integration of different data types, particularly combining qualitative and quantitative data for parameter identification [6]. This approach converts qualitative biological observations into inequality constraints on model outputs, which are then used alongside quantitative measurements to estimate model parameters [6]. For example, qualitative data on viability/inviability of mutant strains can be formalized as constraints (e.g., protein A concentration < protein B concentration), enabling simultaneous fitting to both qualitative phenotypes and quantitative time-course measurements [6].

The modeling process typically involves minimizing an objective function that accounts for both data types:

f_tot(x) = f_quant(x) + f_qual(x)

where f_quant(x) is the sum of squared differences between model predictions and quantitative data, and f_qual(x) imposes penalties for violations of qualitative constraints [6].

Table 2: Multi-Omics Technologies in Systems Biology

| Technology | Measured Components | Application in Systems Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Complete sets of genes | Identify genetic components and variations |

| Transcriptomics | Gene expression levels | Understand regulatory dynamics |

| Proteomics | Proteins and modifications | Characterize functional molecules |

| Metabolomics | Metabolic products | Profile metabolic state and fluxes |

| Metagenomics | Microbial communities | Study microbiome interactions |

The Systems Biology Workflow: From Data to Models

Experimental Design and Data Generation

Systems biology relies on technologies that generate comprehensive, quantitative datasets. High-throughput measurement techniques enable simultaneous monitoring of thousands of molecular components, providing the raw material for system-level analysis [1] [4]. For example, mass spectrometry-based proteomics can investigate protein phosphorylation states over time, revealing dynamic signaling networks [1]. Genome-wide RNAi screens help characterize signaling network relationships by systematically perturbing components and observing system responses [1].

Critical to this process is the structured organization of data. Formats like SBtab (Systems Biology tabular format) establish conventions for structured data tables with defined table types for different kinds of data, syntax rules for names and identifiers, and standardized formulae [7]. This standardization enables sharing and integration of datasets from diverse sources, facilitating collaborative model building.

Computational Implementation and Model Building

The computational workflow involves several stages: data preprocessing and normalization, network inference, model construction, and simulation. Graph databases have become essential tools for representing biological knowledge, as they naturally capture complex relationships between heterogeneous entities [5]. Compared to traditional relational databases, graph databases can improve query performance for biological pathway exploration by up to 93% [5].

Model building often employs differential equation systems to describe biochemical reaction networks or constraint-based models to simulate metabolic networks. Parameter estimation techniques determine values that optimize fit to experimental data, while sensitivity analysis identifies which parameters most strongly influence system behavior.

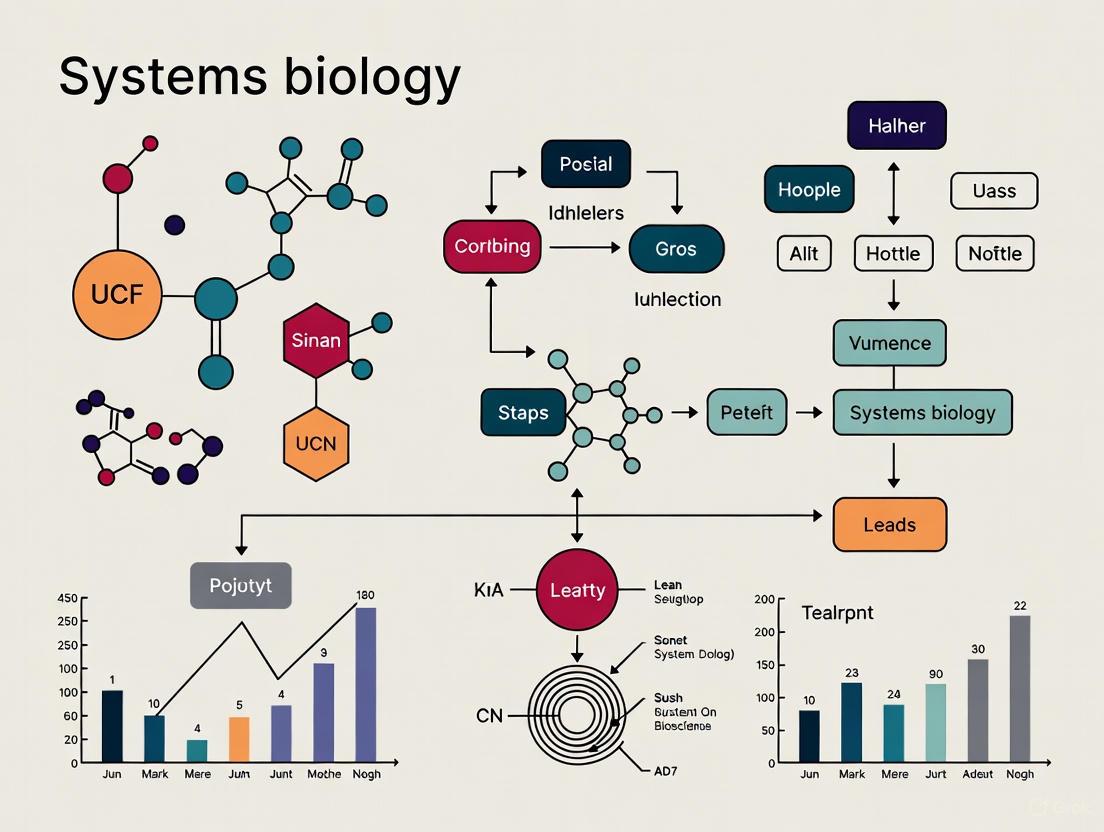

Diagram 1: Systems Biology Modeling Workflow (77 characters)

Practical Implementation: A Case Study in Parameter Identification

Experimental Protocol: Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Data

This protocol adapts methodologies from Nature Communications for estimating parameters in systems biology models using both qualitative and quantitative data [6].

Objective: To estimate kinetic parameters for a biochemical network model when complete quantitative time-course data are unavailable.

Materials and Reagents:

- Wild-type and mutant organisms (e.g., yeast strains)

- Reagents for quantitative measurements (e.g., antibodies for protein quantification, qPCR reagents for gene expression)

- Environment for applying perturbations (e.g., ligands, temperature shifts, nutrient changes)

Procedure:

Quantitative Data Collection:

- Design experiments to measure dynamic responses of key system components

- Collect time-course measurements of molecular species (proteins, metabolites, mRNAs)

- Perform technical and biological replicates to estimate measurement error

- Normalize data to account for experimental variations

Qualitative Data Encoding:

- Compile categorical observations from literature or experimental phenotypes (e.g., "mutant strain is inviable," "oscillations occur," "protein A localizes to nucleus")

- Convert each qualitative observation into a mathematical inequality constraint

- Example: For qualitative observation "strain with mutated protein X cannot grow," formulate as

growth_rate_X_mutant < threshold - Assign appropriate constraint weights (Ci) based on confidence in qualitative observation

Parameter Estimation:

- Define objective function combining quantitative and qualitative terms:

f_tot(x) = Σ(y_model,j - y_data,j)² + Σ Ci · max(0, gi(x)) - Initialize parameters using literature values or reasonable estimates

- Apply optimization algorithm (e.g., differential evolution, scatter search) to minimize

f_tot(x) - Validate parameter estimates using cross-validation or profile likelihood analysis

- Define objective function combining quantitative and qualitative terms:

Model Validation:

- Test model predictions against additional experimental data not used in fitting

- Perform sensitivity analysis to identify most influential parameters

- Assess model robustness to parameter variations

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Systems Biology Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Systems Biology | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| RNAi libraries | Genome-wide perturbation | Functional screening of signaling networks [1] |

| Mass spectrometry reagents | Proteome quantification | Phosphoproteomics for signaling dynamics [1] |

| Antibodies for phospho-proteins | Signaling activity measurement | Monitoring pathway activation states |

| Metabolite standards | Metabolome quantification | Absolute concentration measurements |

| Stable isotope labels | Metabolic flux analysis | Tracking nutrient incorporation |

Application to Biological Networks

This methodology was successfully applied to model Raf inhibition dynamics and yeast cell cycle regulation [6]. For the cell cycle model, researchers incorporated 561 quantitative time-course data points and 1,647 qualitative inequalities from 119 mutant yeast strains to identify 153 model parameters [6]. The combined approach yielded higher confidence in parameter estimates than either dataset could provide individually [6].

Diagram 2: Raf Signaling and Inhibition Network (76 characters)

Applications and Impact in Biomedical Research

Advancing Therapeutic Development

Systems biology has transformed drug discovery and development through several key applications. In drug target identification, network models help identify critical nodes whose perturbation would achieve desired therapeutic effects with minimal side effects [3]. The bottom-up approach specifically facilitates "integration and translation of drug-specific in vitro findings to the in vivo human context," including safety evaluations [3].

In vaccine development, systems biology approaches study the intersection of innate and adaptive immune receptor pathways and their control of gene networks [1]. Researchers focus on pathogen sensing in innate immune cells and how antigen receptors, cytokines, and TLRs determine whether B cells become memory cells or long-lived plasma cells—a process critical for vaccine efficacy [1].

Personalized Medicine and Digital Twins

A promising application is the development of digital twins—virtual replicas of biological entities that use real-world data to simulate responses under various conditions [2]. This approach allows prediction of how individual patients will respond to different treatments before administering them clinically.

The integration of multi-omics data enables stratification of patient populations based on their molecular network states rather than single biomarkers [2]. This systems-level profiling provides a more comprehensive understanding of disease mechanisms and treatment responses, moving toward personalized therapeutic strategies.

Future Directions and Challenges

As systems biology continues to evolve, several challenges and opportunities emerge. Data integration remains a significant hurdle, as harmonizing diverse datasets requires sophisticated computational methods and standards [7] [5]. The development of knowledge graphs that semantically integrate biological information across multiple scales is addressing this challenge [5].

Another frontier is the multi-scale modeling of biological systems, from molecular interactions to organism-level physiology. This requires developing new mathematical frameworks that can efficiently bridge scales and capture emergent behaviors across these scales.

The field is also moving toward more predictive models that can accurately forecast system behavior under novel conditions, with applications ranging from bioenergy crop optimization to clinical treatment personalization [2] [4]. As these models improve, they will increasingly inform decision-making in biotechnology and medicine.

Ultimately, systems biology represents not just a set of technologies but a fundamental shift in how we study biological complexity. By embracing holistic approaches and computational integration, it offers a path to understanding the profound interconnectedness of living systems.

Systems biology represents a fundamental paradigm shift in biological research, moving from a traditional reductionist approach to a holistic perspective that emphasizes the study of complex biological systems as unified wholes. This field is defined as the computational and mathematical analysis and modeling of complex biological systems, focusing on complex interactions within biological systems using a holistic approach (holism) rather than traditional reductionism [3]. The reductionist approach, which has dominated biology since the 17th century, successfully identifies individual components but offers limited capacity to understand how system properties emerge from their interactions [3] [8]. In contrast, systems biology recognizes that biological systems exhibit emergent behavior—unique properties possessed only by the whole system and not by individual components in isolation [8]. This paradigm transformation began in the early 20th century as a reaction against strictly mechanistic and reductionist attitudes, with pioneers such as Jan Smuts coining the term "holism" to describe how whole systems like cells, tissues, organisms, and populations possess unique emergent properties that cannot be understood by simply summing their individual parts [8].

The core challenge that systems biology addresses is the fundamental limitation of reductionism: while we have extensive knowledge of molecular components, we understand relatively little about how these components interact to produce complex biological functions [3]. As Denis Noble succinctly stated, systems biology "is about putting together rather than taking apart, integration rather than reduction. It requires that we develop ways of thinking about integration that are as rigorous as our reductionist programmes, but different" [3]. This philosophical shift necessitates new computational and mathematical approaches to manage the complexity of biological networks and uncover the principles governing their organization and behavior.

Philosophical Foundations: From Reductionism to Holism

The Historical Paradigm Shift

The transition from reductionism to systems thinking in biology represents one of the most significant conceptual revolutions in modern science. Reductionism, with roots in the 17th century philosophy of René Descartes, operates on the principle that complex situations can be understood by reducing them to manageable pieces, examining each in turn, and reassembling the whole from the behavior of these pieces [8]. This approach achieved remarkable successes throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, particularly in molecular biology, where complex organisms were broken down into their constituent molecules and pathways. The mechanistic viewpoint, exemplified by Jacques Loeb's 1912 work, interpreted organisms as deterministic machines whose behavior was predetermined and identical between all individuals of a species [8].

The limitations of reductionism became increasingly apparent through several key experimental findings. In 1925, Paul Weiss demonstrated in his PhD dissertation that insects exposed to identical environmental stimuli achieved similar behavioral outcomes through unique individual trajectories, contradicting Loeb's mechanistic predictions [8]. Later, Roger Williams' groundbreaking 1956 work compiled extensive evidence of molecular, physiological, and anatomical individuality in animals, showing 20- to 50-fold variations in biochemical, hormonal, and physiological parameters between normal, healthy individuals [8]. Similar variation has been observed in plants, with mineral and vitamin content varying 10- to 20-fold between individuals of the same species [8]. These findings fundamentally undermined the mechanistic view that organisms operate like precise machines with exacting specifications for their constituents.

The Conceptual Framework of Holism and Emergence

The philosophical foundation of systems biology rests on two complementary concepts: holism and emergence. Holism emphasizes that systems must be studied as complete entities, recognizing that the organization and interactions between components contribute significantly to system behavior. Emergence describes the phenomenon where novel properties and behaviors arise at each level of biological organization that are not present at lower levels and cannot be easily predicted from studying components in isolation [8]. As Aristotle originally stated, "the whole is something over and above its parts and not just the sum of them all" [8].

This framework reconciles the apparent contradiction between reductionism and holism by recognizing that both approaches answer different biological questions. Reductionism helps understand how organisms are built, while holism explains why they are arranged in specific ways [8]. The synthesis of these perspectives enables researchers to appreciate both the components and their interactions, leading to a more comprehensive understanding of biological complexity. This integrated approach requires new conceptual tools, including principles of control systems, structural stability, resilience, robustness, and computer modeling techniques that can handle biological complexity more effectively than traditional mechanistic approaches [8].

Table 1: Key Philosophical Concepts in Systems Biology

| Concept | Definition | Biological Example |

|---|---|---|

| Reductionism | Analyzing complex systems by breaking them down into smaller, more manageable components | Studying individual enzymes in a metabolic pathway in isolation |

| Holism | Understanding systems as unified wholes whose behavior cannot be fully explained by their components alone | Analyzing how metabolic networks produce emergent oscillations |

| Emergence | Properties and behaviors that arise at system level through interactions between components | Consciousness emerging from neural networks; life emerging from biochemical interactions |

| Mechanism | Interpretation of biological systems as deterministic machines with predictable behaviors | Loeb's view of tropisms as forced, invariant physico-chemical mechanisms |

Technical Approaches in Systems Biology

Top-Down and Bottom-Up Methodologies

Systems biology employs two complementary methodological approaches for investigating biological systems: top-down and bottom-up strategies. The top-down approach begins with a global perspective of system behavior by collecting genome-wide experimental data through various 'omics' technologies (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) [3]. This method identifies molecular interaction networks by analyzing correlated behaviors observed in large-scale studies, with the primary goal of uncovering novel molecular mechanisms through a cyclical process that starts with experimental data, transitions to data analysis and integration to identify correlations among molecule concentrations, and concludes with hypothesis development regarding the co- and inter-regulation of molecular groups [3]. The significant advantage of top-down systems biology lies in its potential to provide comprehensive genome-wide insights while focusing on the metabolome, fluxome, transcriptome, and/or proteome.

In contrast, the bottom-up approach begins with foundational elements by developing interactive behaviors (rate equations) of each component process within a manageable portion of the system [3]. This methodology examines the mechanisms through which functional properties arise from interactions of known components, with the primary goal of integrating pathway models into a comprehensive model representing the entire system. The bottom-up approach is particularly valuable in drug development, as it facilitates the integration and translation of drug-specific in vitro findings to the in vivo human context, including safety evaluations such as cardiac safety assessment [3]. This approach employs various models ranging from single-cell to advanced three-dimensional multiphase models to predict drug exposure and physiological effects.

Multi-Omics Integration and Biological Networks

The emergence of multi-omics technologies has fundamentally transformed systems biology by providing extensive datasets that cover different biological layers, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics [3]. These technologies enable large-scale measurement of biomolecules, leading to more profound comprehension of biological processes and interactions. The integration of these diverse data types requires sophisticated computational methods, including network analysis, machine learning, and pathway enrichment approaches, to interpret multi-omics data and enhance understanding of biological functions and disease mechanisms [3].

Biological networks represent a core organizational principle in systems biology, manifesting at multiple scales from molecular interactions to ecosystem relationships. These networks exhibit specific structural properties including hierarchical organization, modularity, and specific topological features that influence their dynamic behavior. The analysis of network properties provides insights into system robustness, adaptability, and vulnerability to perturbation, which has significant implications for understanding disease mechanisms and developing therapeutic interventions.

Table 2: Comparison of Top-Down and Bottom-Up Approaches in Systems Biology

| Aspect | Top-Down Approach | Bottom-Up Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Global system behavior using 'omics' data | Individual component mechanisms and interactions |

| Primary Goal | Discover novel molecular mechanisms from correlation patterns | Integrate known mechanisms into comprehensive system models |

| Data Requirements | Large-scale, high-throughput omics measurements | Detailed kinetic parameters and mechanistic knowledge |

| Strengths | Hypothesis-free discovery; comprehensive coverage | Mechanistic understanding; predictive capability |

| Applications | Biomarker discovery; network inference | Drug development; metabolic engineering; safety assessment |

| Technical Challenges | Data integration; distinguishing correlation from causation | Parameter estimation; computational complexity of integration |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Standards and Visualization Frameworks

The complexity of systems biology necessitates standardized frameworks for representing and communicating biological knowledge. The Systems Biology Graphical Notation (SBGN) provides a formal standard for visually representing systems biology information, consisting of three complementary graphical languages [9]:

- Process Description (PD): Represents sequences of interactions between biochemical entities in a mechanistic, step-by-step manner

- Entity Relationship (ER): Depicts interactions that occur when relevant entities are present, focusing on relationships rather than temporal sequences

- Activity Flow (AF): Shows influences between entities, emphasizing information flow rather than biochemical transformations

SBGN employs carefully designed glyphs (graphical symbols) that follow specific design principles: they must be simple, scalable, color-independent, easily distinguishable, and minimal in number [9]. This standardization enables researchers to interpret complex biological maps without additional legends or explanations, facilitating unambiguous communication similar to engineering circuit diagrams.

For computational modeling, the Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) provides a standardized format for representing mathematical models of biological systems [10]. When combined with the SBML Layout and Render packages, SBML enables storage of visualization data directly within model files, ensuring interoperability and reproducibility across different software platforms [10]. Tools like SBMLNetwork build on these standards to automate the generation of standards-compliant visualization data, employing force-directed auto-layout algorithms enhanced with biochemistry-specific heuristics where reactions are represented as hyper-edges anchored to centroid nodes and connections are drawn as role-aware Bézier curves that preserve reaction semantics while minimizing edge crossings [10].

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Systems biology research relies on specialized reagents and computational tools designed for large-scale data generation and analysis. The following table summarizes essential resources used in modern systems biology investigations:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools in Systems Biology

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-omics Platforms | Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Metabolomics platforms | Large-scale measurement of biomolecules across different biological layers |

| Visualization Tools | CellDesigner, Newt, PathVisio, SBGN-ED, yEd | Construction, analysis, and visualization of biological pathway maps |

| Modeling Standards | SBML (Systems Biology Markup Language), SBGN (Systems Biology Graphical Notation) | Standardized representation and exchange of models and visualizations |

| Computational Libraries | SBMLNetwork, libSBML, SBMLDiagrams | Software libraries for standards-based model visualization and manipulation |

| Data Integration Frameworks | Network analysis tools, Machine learning algorithms, Pathway enrichment methods | Integration and interpretation of multi-omics data to understand biological function |

Applications in Research and Drug Development

Current Research Frontiers

Systems biology approaches are driving innovation across multiple research domains, as evidenced by current topics in leading scientific journals. Frontier research areas include innovative computational strategies for modeling complex biological systems, integrative bioinformatics methods, multi-omics integration for aquatic microbial systems, evolutionary systems biology, and decoding antibiotic resistance mechanisms through computational analysis and dynamic tracking in microbial genomics and phenomics [11]. These research directions highlight the expanding applications of systems principles across different biological scales and systems.

Recent advances in differentiable simulation, such as the JAXLEY platform, demonstrate how systems biology incorporates cutting-edge computational techniques from machine learning [12]. These tools leverage automatic differentiation and GPU acceleration to make large-scale biophysical neuron model optimization feasible, combining biological accuracy with advanced machine-learning optimization techniques to enable efficient hyperparameter tuning and exploration of neural computation mechanisms at scale [12]. Similarly, novel experimental methods like TIRTL-seq provide deep, quantitative, and affordable paired T cell receptor sequencing at cohort scale, generating the rich datasets necessary for systems-level immune analysis [12].

Drug Development and Therapeutic Innovation

In pharmaceutical research, systems biology has transformed drug discovery and development through more predictive modeling of drug effects and safety. The bottom-up modeling approach enables researchers to reconstruct processes determining drug exposure, including plasma concentration-time profiles and their electrophysiological implications on cardiac function [3]. By integrating data from multiple in vitro systems that serve as stand-ins for in vivo absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion processes, researchers can predict drug exposure and translate in vitro data on drug-ion channel interactions to physiological effects [3]. This approach allows predictions of exposure-response relationships considering both inter- and intra-individual variability, making it particularly valuable for evaluating drug effects at population level.

The separation of drug-specific, system-specific, and trial design data characteristic of bottom-up approaches enables more rational drug development strategies and has been successfully applied in numerous documented cases of physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling in drug discovery and development [3]. These applications demonstrate how systems biology principles directly impact therapeutic innovation by providing more accurate predictions of drug efficacy and safety before extensive clinical testing.

Visualizing Biological Networks: Principles and Practices

Network Visualization Methodologies

Effective visualization is essential for interpreting the complex networks that underlie biological systems. The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for network construction and analysis in systems biology, incorporating both top-down and bottom-up approaches:

Network Analysis Workflow

The visualization of biological networks follows specific design principles to ensure clarity and accurate communication. For SBGN maps, key layout requirements include avoiding overlaps between objects, emphasizing map structures, preserving the user's mental map, minimizing edge crossings, maximizing angles between edges, minimizing edge bends, and reducing edge length [9]. For Process Description maps specifically, additional constraints include preventing vertex overlaps (except for containment), drawing vertices horizontally or vertically, avoiding border line overlaps, attaching consumption and production edges to opposite sides of process vertices, and ensuring proper label placement without overlapping other elements [9].

Emerging Standards and Tools

The development of standardized visualization tools continues to evolve, with recent advances focusing on improving interoperability and reproducibility. SBMLNetwork represents one such advancement, building directly on SBML Layout and Render specifications to automate generation of standards-compliant visualization data [10]. This open-source library offers a modular implementation with broad integration support and provides a robust API tailored to systems biology researchers' needs, enabling high-level visualization features that translate user intent into reproducible outputs supporting both structural representation and dynamic data visualization within SBML models [10].

These tools address the significant challenge in biological visualization where different software tools often manage model visualization data in custom-designed, tool-specific formats stored separately from the model itself, hindering interoperability and reproducibility [10]. By building on established standards and providing accessible interfaces, newer frameworks aim to make standards-based model diagrams easier to create and share, thereby enhancing reproducibility and accelerating communication within the systems biology community.

The core principles of holism, emergence, and biological networks have fundamentally transformed biological science, providing new conceptual frameworks and methodological approaches for tackling complexity. Systems biology has demonstrated that biological systems cannot be fully understood through reductionist approaches alone, but require integrative perspectives that recognize the hierarchical organization of living systems and the emergent properties that arise at each level of this hierarchy [8]. The philosophical shift from pure reductionism to a balanced perspective that incorporates both mechanistic detail and systems-level understanding represents one of the most significant developments in contemporary biology.

The continuing evolution of systems biology is marked by increasingly sophisticated computational methods, more comprehensive multi-omics integration, and enhanced visualization standards that together enable deeper understanding of biological complexity. As these approaches mature, they offer promising avenues for addressing fundamental biological questions and applied challenges in drug development, biotechnology, and medicine. The integration of systems principles across biological research ensures that investigators remain focused on both the components of biological systems and the remarkable properties that emerge from their interactions.

The question "What is life?" remains one of the most fundamental challenges in science. Traditionally, biology has sought to answer this question by cataloging and characterizing the molecular components of living systems—DNA, proteins, lipids, and metabolites. However, this reductionist approach, while enormously successful in identifying the parts list of life, provides an incomplete picture. The information perspective offers a paradigm shift: life emerges not from molecules themselves, but from the complex, dynamic relationships and information flows between these molecules within a system [13]. This framework moves beyond seeing biological entities as mere mechanisms and instead conceptualizes them as complex, self-organizing information processing systems.

This whitepaper elaborates on this informational viewpoint, framing it within the context of systems biology, an interdisciplinary field that focuses on complex interactions within biological systems, using a holistic approach to biological research [14] [15]. For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting this perspective is more than a philosophical exercise; it provides a powerful lens through which to understand disease mechanisms, identify robust therapeutic targets, and advance the promise of personalized medicine [14] [15]. We will explore the theoretical underpinnings of this perspective, detail the experimental and computational methodologies required to study it, and demonstrate its practical applications in biomedical research.

Theoretical Foundations: Information and Dissipation in Living Systems

The informational view of life posits that the essence of biological systems lies in their organizational logic. A living system is a dynamic, self-sustaining network of interactions where information is not merely stored but continuously processed, transmitted, and utilized to maintain organization against the universal tendency toward disorder.

Beyond the Reductionist Paradigm

A purely mechanistic (reductionist) perspective of biology, which has dominated experimental science, views organisms as complex, highly ordered machines [13]. This view, however, struggles to explain core properties of life such as self-organization, self-replication, and adaptive evolution without invoking a sense of "teleonomy" or end-purpose [13]. The informational perspective suggests that we must reappraise our concepts of what life really is, moving from a static, parts-based view to a dynamic one focused on relationships and state changes [13].

Life as a Dissipative System and the Role of Information

A more fruitful approach is to view living systems as dissipative structures, a concept borrowed from thermodynamics. These are open systems that maintain their high level of organization by dissipating energy and matter from their environment, exporting entropy to stay ordered [13]. This process is fundamentally tied to information dynamics. The concept of "Shannon dissipation" may be crucial, where information itself is generated, transmitted, and degraded as part of the system's effort to maintain its functional order [13]. In this model, the texture of life is woven from molecules, energy, and information flows.

Table 1: Key Theoretical Concepts in the Information Perspective of Life

| Concept | Definition | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Dissipative Structure [13] | An open system that maintains order by dissipating energy and exporting entropy. | Explains how living systems defy the second law of thermodynamics locally by creating order through energy consumption. |

| Shannon Dissipation [13] | The generation, transmission, and degradation of information within a system. | Positions information flow as a fundamental thermodynamic process in maintaining life. |

| Autopoiesis [13] | The property of a system that is capable of self-creation and self-maintenance. | Describes the self-bounding, circular organization that characterizes a living entity. |

| Equisotropic vs. Disquisotropic Space [13] | An ideal space of identical particles (E-space) vs. a space of unique particles (D-space). | Highlights the tension between statistical averages and the unique molecular interactions that underpin biological specificity. |

| Robustness [16] | A system's ability to maintain function despite internal and external perturbations. | A key emergent property of complex biological networks, essential for reliability and a target for therapeutic intervention. |

The distinction between an "equisotropic Boltzmann space" (E-space), where particles are statistically identical, and a "disquisotropic Boltzmann space" (D-space), where each particle is unique, is particularly insightful [13]. Biology operates predominantly in a D-space, where the specific, unique interactions between individual molecules and their spatial-temporal context give rise to the rich, complex behaviors that define life. This uniqueness is a physical substrate for biological information.

Methodologies: Mapping the Informational Network

Translating the theoretical information perspective into tangible research requires a suite of advanced technologies that generate quantitative, dynamic, and spatially-resolved data. The goal is to move from static snapshots of molecular parts to dynamic models of their interactions.

Experimental Protocols for Quantitative Data Generation

Generating high-quality, reproducible quantitative data is the cornerstone of building reliable models in systems biology [17]. Standardizing experimental protocols is paramount.

- Defined Biological Systems: The use of genetically defined inbred strains of animals or well-characterized cell lines is preferred. Tumor-derived cell lines (e.g., HeLa, Cos-7) can be genetically unstable, leading to significant inter-laboratory variability. Where possible, primary cells with standardized preparation and culture protocols provide a more robust foundation [17].

- Quantitative Techniques: Advanced methods are required to move from qualitative to quantitative data.

- Quantitative Western Blotting: Standard immunoblotting can be advanced for quantitative data by systematically establishing procedures for data acquisition and processing, including normalization to correct for cell number and experimental error [17].

- Quantitative Fluorescence Time-Lapse Microscopy: This method is crucial for visualizing protein localization and concentration dynamics in single, living cells over time. It can reveal properties like oscillation and nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling that are invisible to traditional, static biochemical methods [16].

- Rigorous Documentation and Annotation: All experimental details must be meticulously recorded, including lot numbers of reagents (e.g., antibodies, which can vary between batches), temperature, pH, and cell passage number. This is essential for data reproducibility and integration [17].

Computational Integration and Modeling

The sheer volume and complexity of quantitative biological data supersede human intuition, making computational modeling not just helpful, but necessary [16].

- Data Integration Workflows: Automated workflows, such as those built with Taverna, can systematically assemble qualitative metabolic networks from databases like KEGG and Reactome, and then parameterize them with quantitative kinetic data from repositories like SABIO-RK [18]. The final model is encoded in the Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML), a standard format for representing computational models in systems biology [17] [18].

- Network Analysis and Visualization: Software platforms like Cytoscape provide an open-source environment for visualizing complex molecular interaction networks and integrating them with various types of attribute data (e.g., gene expression, protein abundance) [19]. Its App-based ecosystem allows for advanced network analysis, including cluster detection and statistical calculation.

- Spatiotemporal Modeling: Modern modeling must account for protein localization and dynamics. This involves tracking not just absolute protein concentrations but also their distribution between cellular compartments (e.g., nucleus vs. cytoplasm), which can re-wire functional interactions and impact system dynamics like cell cycle timing [16].

Diagram 1: Systems biology iterative research cycle.

Practical Application: The Mammalian Cell Cycle as an Informational Network

The mammalian cell cycle serves as an exemplary model to illustrate the information perspective. It is a complex, dynamic process that maintains precise temporal order and robustness while remaining flexible to respond to internal and external signals [16].

Information Processing in Cell Cycle Transitions

The unidirectional progression of the cell cycle is governed by the dynamic relationships between key molecules. The core information processing involves:

- Protein Dosage and Stoichiometry: The timing of molecular switches is controlled by the abundance and stoichiometry of multiple proteins within complexes. For example, the activity of Cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks) is regulated not only by their binding to cyclins but also by the concentration of inhibitor proteins like p27Kip1 [16].

- Spatiotemporal Dynamics (Localization): The function of a protein is dictated by its presence in the correct cellular compartment at the right time. The tumor suppressor p53 and the Cdk inhibitor p27 exert their canonical functions in the nucleus. However, their mislocalization to the cytoplasm can disrupt the cell cycle, not necessarily by changing total abundance, but by altering the local network of interactions available to them [16]. Cyclins E and A, while nuclear, also localize to centrosomes, where they interact with a different set of partners to control centrosome duplication [16].

The MAmTOW Approach for Quantifying Network Robustness

To systematically understand how the cell cycle network processes information to ensure robustness, we propose a multidisciplinary strategy centered on the "Maximum Allowable mammalian Trade-Off–Weight" (MAmTOW) method [16]. This innovative approach aims to determine the upper limit of gene copy numbers (protein dosage) that mammalian cells can tolerate before the cell cycle network loses its robustness and fails. This method moves beyond models that rely on arbitrary concentration thresholds by exploring the permissible ranges of protein abundance and their impact on the timing of phase transitions.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Quantitative Systems Biology

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 [16] | Precise genome editing for gene tagging and modulation. | Tagging endogenous proteins with fluorescent reporters (e.g., GFP) without altering their genetic context or native regulation. |

| Quantitative Time-Lapse Microscopy [16] | Tracking protein localization and concentration in live cells over time. | Measuring spatiotemporal dynamics of cell cycle regulators (e.g., p27, p53) in single cells. |

| Fluorescent Protein Tags (e.g., GFP) [16] | Visualizing proteins and their dynamics in living cells. | Real-time observation of protein synthesis, degradation, and compartmental translocation. |

| Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) [17] [18] | Software-independent format for representing computational models. | Exchanging and reproducing mathematical models of biological networks between different research groups and software tools. |

| Cytoscape [19] | Open-source platform for visualizing and analyzing complex networks. | Integrating molecular interaction data with omics data to map and analyze system-wide pathways. |

Diagram 2: p27- Cdk2 informational network regulating G1/S transition.

Implications for Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Intervention

Adopting the information perspective and the tools of systems biology has profound implications for pharmaceutical R&D, particularly in addressing complex, multifactorial diseases.

Moving Beyond Single-Target Approaches

The traditional drug discovery model of "one drug, one target" has seen diminishing returns, especially for complex diseases like cancer, diabetes, and neurodegenerative disorders [14]. These conditions are driven by multiple interacting factors and perturbations in network dynamics, not by a single defective component. A reductionist approach focusing on individual entities in isolation can be misleading and ineffective [14]. Systems biology allows for the identification of optimal drug targets based on their importance as key 'nodes' within an overall network, rather than on their isolated properties [14].

Polypharmacology and Combination Therapies

The informational view naturally leads to polypharmacology—designing drugs to act upon multiple targets simultaneously or using combinations of drugs to exert moderate effects at several points in a diseased control network [14]. This approach can enhance efficacy and reduce the likelihood of resistance. Systems biology models are essential here, as experimentally testing all possible drug combinations in humans is prohibitively complex. In silico models can simulate the effects of multi-target interventions and help identify the most promising combinations for clinical testing [14].

Advancing Personalized Medicine

The concept of "one-size-fits-all" medicine is inadequate for a biologically diverse population. Systems biology facilitates personalized medicine by enabling the integration of individual genomic, proteomic, and clinical data to create patient-specific models [14] [15]. These models can identify unique biological signatures that predict which patients are most likely to benefit from, or be harmed by, a particular therapy, thus guiding optimal treatment stratification [14].

The question "What is life?" finds a powerful answer in the information perspective: life is a specific, dynamic set of relationships among molecules, a continuous process of information flow and dissipation that maintains organization in the face of entropy. This framework, operationalized through the methods of systems biology, represents a fundamental shift from a purely mechanistic to a relational and informational view of biological systems.

For researchers and drug developers, this is more than a theoretical refinement; it is a practical necessity. The complexity of human disease and the failure of simplistic, single-target therapeutic strategies demand a new approach. By conceptualizing life as a relationship among molecules and learning to map, model, and manipulate the informational networks that constitute a living system, we can decipher the design principles of biological robustness. This knowledge will ultimately empower us to develop more effective, nuanced, and personalized therapeutic interventions that restore healthy information processing in diseased cells, tissues, and organisms. The future of biomedical innovation lies in understanding not just the parts, but the conversation.

The Human Genome Project (HGP) stands as a landmark global scientific endeavor that fundamentally transformed biological research, catalyzing a shift from reductionist approaches to integrative, systems-level science [20] [21]. This ambitious project, officially conducted from 1990 to 2003, exemplified "big science" in biology, bringing together interdisciplinary teams to generate the first sequence of the human genome [20] [21]. The HGP not only provided a reference human genome sequence but also established new paradigms for collaborative, data-intensive biological research that would ultimately give rise to modern systems biology [20]. The project's completion ahead of schedule in 2003, with a final cost approximately equal to its original $3 billion budget, represented one of the most important biomedical research undertakings of the 20th century [21] [22].

The HGP's significance extends far beyond its primary goal of sequencing the human genome. It established foundational principles and methodologies that would enable the emergence of systems biology as a dominant framework for understanding biological complexity [14]. By providing a comprehensive "parts list" of human genes and other functional elements, the HGP created an essential resource that allowed researchers to begin studying how these components interact within complex networks [20]. This transition from studying individual genes to analyzing entire systems represents one of the most significant evolutionary trajectories in modern biology, enabling new approaches to understanding health, disease, and therapeutic development [20] [14].

The Human Genome Project: Technical Execution and Methodological Innovations

Project Goals and International Collaboration Structure

The Human Genome Project was conceived as a large, well-organized, and highly collaborative international effort that would sequence not only the human genome but also the genomes of several key model organisms [21]. The original goals, outlined by a special committee of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences in 1988, included sequencing the entire human genome along with genomes of carefully selected non-human organisms including the bacterium E. coli, baker's yeast, fruit fly, nematode, and mouse [21]. The project's architects anticipated that the resulting information would inaugurate a new era for biomedical research, though the actual outcomes would far exceed these initial expectations.

The organizational structure of the HGP represented a novel approach to biological research. The project involved researchers from 20 separate universities and research centers across the United States, United Kingdom, France, Germany, Japan, and China, collectively known as the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium [21]. In the United States, researchers were funded by both the Department of Energy and the National Institutes of Health, which created the Office for Human Genome Research in 1988 (later becoming the National Human Genome Research Institute in 1997) [21]. This collaborative model proved essential for managing the enormous technical challenges of sequencing the human genome.

Sequencing Technologies and Methodological Approaches

The HGP utilized one principal method for DNA sequencing—Sanger DNA sequencing—but made substantial advancements to this fundamental approach through a series of major technical innovations [21]. The project employed a hierarchical clone-by-clone sequencing strategy using bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) as cloning vectors [20]. This method involved breaking the genome into overlapping fragments, cloning these fragments into BACs, arranging them in their correct chromosomal positions to create a physical map, and then sequencing each BAC fragment before assembling the complete genome sequence.

Table 1: Evolution of DNA Sequencing Capabilities During and After the Human Genome Project

| Time Period | Technology Generation | Key Methodology | Time per Genome | Cost per Genome | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990-2003 (HGP) | First-generation | Sanger sequencing, capillary arrays | 13 years | ~$2.7 billion | Reference genome generation |

| 2003-2008 | Transitional | Emerging second-generation platforms | Several months | ~$1-10 million | Individual genome sequencing |

| 2008-2015 | Second-generation | Cyclic array sequencing (Illumina) | Weeks | ~$1,000-10,000 | Large-scale genomic studies |

| 2015-Present | Third-generation & beyond | Long-read sequencing, AI-powered analysis | Hours to days | ~$100-1,000 | Clinical diagnostics, personalized medicine |

A critical methodological innovation was the development of high-throughput automated DNA sequencing machines that utilized capillary electrophoresis, which dramatically increased sequencing capacity compared to earlier manual methods [20]. The project also pioneered sophisticated computational approaches for sequence assembly and analysis, requiring the development of novel algorithms and software tools to handle the massive amounts of data being generated [20] [23].

Key Experimental Protocols and Reagent Systems

The experimental workflow of the HGP involved multiple stages, each requiring specific methodological approaches and reagent systems. The process began with DNA collection from volunteer donors, primarily coordinated through researchers at the Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, New York [21]. After obtaining informed consent and collecting blood samples, DNA was extracted and prepared for sequencing.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Materials in Genome Sequencing

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Process | Specific Application in HGP |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BACs) | Cloning vector for large DNA fragments (100-200 kb) | Used in hierarchical clone-by-clone sequencing strategy |

| Cosmids & Fosmids | Cloning vectors for smaller DNA fragments | Subcloning and mapping of genomic regions |

| Restriction Enzymes | Molecular scissors for cutting DNA at specific sequences | Fragmenting genomic DNA for cloning |

| Fluorescent Dideoxy Nucleotides | Chain-terminating inhibitors for DNA sequencing | Sanger sequencing with fluorescent detection |

| Capillary Array Electrophoresis Systems | Separation of DNA fragments by size | High-throughput sequencing replacement for gel electrophoresis |

| Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) Reagents | Amplification of specific DNA sequences | Target amplification for various analytical applications |

The sequencing protocol itself relied on the Sanger method, which uses fluorescently labeled dideoxynucleotides to terminate DNA synthesis at specific bases, generating fragments of different lengths that can be separated by size to determine the sequence [21]. During the HGP, this method was scaled up through the development of 96-capillary sequencing machines that allowed parallel processing of multiple samples, significantly increasing throughput [20]. The data generated from these sequencing runs were then assembled using sophisticated computational algorithms that identified overlapping regions between fragments to reconstruct the complete genome sequence [23].

From Linear Sequence to Biological Systems: The Rise of Systems Biology

Conceptual Foundations of Systems Biology

Systems biology represents a fundamental shift from traditional reductionist approaches in biological research, instead focusing on complex interactions within biological systems using a holistic perspective [14]. This approach recognizes that biological functioning at the level of cells, tissues, and organs emerges from networks of interactions among molecular components, and cannot be fully understood by studying individual elements in isolation [14]. The HGP provided the essential foundation for this new perspective by delivering a comprehensive parts list of human genes and other genomic elements, enabling researchers to begin investigating how these components work together in functional systems [20].

The conceptual framework of systems biology views biological organisms as complex adaptive systems with properties that distinguish them from engineered systems, including exceptional capacity for self-organization, continual self-maintenance through component turnover, and auto-adaptation to changing circumstances through modified gene expression and protein function [14]. These properties create both challenges and opportunities for researchers seeking to understand biological systems. Systems biology employs iterative cycles of biomedical experimentation and mathematical modeling to build and test complex models of biological function, allowing investigation of a much broader range of conditions and interventions than would be possible through traditional experimental approaches alone [14].

Technological and Analytical Enablers of Systems Biology

The emergence of systems biology as a practical discipline has been enabled by several key technological and analytical developments, many of which originated from or were accelerated by the Human Genome Project. These include:

High-throughput Omics Technologies: The success of the HGP spurred development of numerous technologies for comprehensive measurement of biological molecules, including transcriptomics (gene expression), proteomics (protein expression and modification), metabolomics (metabolite profiling), and interactomics (molecular interactions) [20]. These technologies provide the multi-dimensional data necessary for systems-level analysis.

Computational and Mathematical Modeling Tools: Systems biology requires sophisticated computational infrastructure and mathematical approaches to handle large datasets and build predictive models [20] [14]. The HGP drove the development of these tools and brought together computer scientists, mathematicians, engineers, and biologists to create new analytical capabilities [20].

Bioinformatics and Data Integration Platforms: The need to manage, analyze, and interpret genomic data led to the development of bioinformatics as a discipline and the creation of data integration platforms such as the UCSC Genome Browser [23]. These resources continue to evolve, providing essential infrastructure for systems biology research.

The convergence of these enabling technologies has created a foundation for studying biological systems across multiple levels of organization, from molecular networks to entire organisms [14]. This multi-scale perspective is essential for understanding how function emerges from interactions between system components and how perturbations at one level can affect the entire system.

Methodological Framework: Integrating Systems Biology Approaches in Research

Core Workflows in Systems Biology Research

Systems biology research typically follows an iterative cycle of computational modeling, experimental perturbation, and model refinement. This methodological framework enables researchers to move from descriptive observations to predictive understanding of biological systems. A generalized workflow for systems biology research includes the following key stages:

System Definition and Component Enumeration: Delineating the boundaries of the biological system under investigation and cataloging its molecular components based on genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and other omics data [14].

Interaction Mapping and Network Reconstruction: Identifying physical and functional interactions between system components to reconstruct molecular networks, including metabolic pathways, signal transduction cascades, and gene regulatory circuits [14].

Quantitative Data Collection and Integration: Measuring dynamic changes in system components under different conditions and integrating these data to create comprehensive profiles of system behavior [14].

Mathematical Modeling and Simulation: Developing computational models that simulate system behavior, often using differential equations, Boolean networks, or other mathematical formalisms to represent the dynamics of the system [14].

Model Validation and Experimental Testing: Designing experiments to test predictions generated by the model and using the results to refine model parameters or structure [14].

This iterative process continues until the model can accurately predict system behavior under novel conditions, at which point it becomes a powerful tool for exploring biological hypotheses in silico before conducting wet-lab experiments.

Analytical Techniques and Computational Tools

The analytical framework of systems biology incorporates diverse computational techniques adapted from engineering, physics, computer science, and mathematics. These include:

Network Analysis: Using graph theory to identify key nodes, modules, and organizational principles within biological networks [14]. This approach helps identify critical control points in cellular systems.

Dynamic Modeling: Applying systems of differential equations to model the time-dependent behavior of biological systems, particularly for metabolic and signaling pathways [14].

Constraint-Based Modeling: Using stoichiometric and capacity constraints to predict possible metabolic states, with flux balance analysis being a widely used example [14].

Multi-Scale Modeling: Integrating models across different biological scales, from molecular interactions to cellular, tissue, and organism-level phenomena [14].

The development and application of these analytical techniques requires close collaboration between biologists and quantitative scientists, exemplifying the cross-disciplinary nature of modern systems biology research [14].

Applications in Drug Development and Precision Medicine

Transforming Pharmaceutical Research and Development

The integration of genomics and systems biology has fundamentally transformed pharmaceutical research and development, addressing critical challenges in the industry [14]. For decades, pharmaceutical R&D focused predominantly on creating potent drugs directed at single targets, an approach that was highly successful for many simple diseases but has proven inadequate for addressing complex multifactorial conditions [14]. The decline in productivity of pharmaceutical R&D despite increasing investment highlights the limitations of this reductionist approach for complex diseases [14].

Systems biology offers powerful alternatives by enabling network-based drug discovery and development [14]. This approach considers drugs in the context of the functional networks that underlie disease processes, rather than viewing drug targets as isolated entities [14]. Key applications include:

Network Pharmacology: Designing drugs or drug combinations that exert moderate effects at multiple points in biological control systems, potentially offering greater efficacy and reduced resistance compared to single-target approaches [14].

Target Identification and Validation: Using network analysis to identify optimal drug targets based on their importance as key nodes within overall disease networks, rather than solely on their isolated properties [14].

Clinical Trial Optimization: Using large-scale integrated disease models to simulate clinical effects of manipulating drug targets, facilitating selection of optimal targets and improving clinical trial design [14].

These applications are particularly valuable for addressing complex diseases such as diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and cancer, which involve multiple genetic and environmental factors that interact through complex networks [14].

Enabling Precision Medicine and Personalized Therapeutics

The convergence of genomic technologies and systems biology approaches has created new opportunities for precision medicine—the tailoring of medical treatment to individual characteristics of each patient [14]. By coupling systems biology models with genomic information, researchers can identify patients most likely to benefit from particular therapies and stratify patients in clinical trials more effectively [14].

The evolution of genomic technologies has been crucial for advancing these applications. While the original Human Genome Project required 13 years and cost approximately $2.7 billion, technological advances have dramatically reduced the time and cost of genome sequencing [24]. By 2025, the equivalent of a gold-standard human genome could be sequenced in roughly 11.8 minutes at a cost of a few hundred pounds [24]. This extraordinary improvement in efficiency has made genomic sequencing practical for clinical applications, enabling rapid diagnosis of rare diseases and guiding targeted cancer therapies [24] [23].

Table 3: Evolution of Genomic Medicine Applications from HGP to Current Practice

| Application Area | HGP Era (1990-2003) | Post-HGP (2003-2015) | Current Era (2015-Present) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rare Disease Diagnosis | Gene discovery through linkage analysis | Targeted gene panels | Whole exome/genome sequencing, rapid diagnostics (hours) |

| Cancer Genomics | Identification of major oncogenes/tumor suppressors | Array-based profiling, early targeted therapies | Comprehensive tumor sequencing, liquid biopsies, immunotherapy guidance |

| Infectious Disease | Pathogen genome sequences | Genomic epidemiology | Real-time pathogen tracing, outbreak surveillance, resistance prediction |

| Pharmacogenomics | Limited polymorphisms for drug metabolism | CYP450 and other key pathway genes | Comprehensive pre-treatment genotyping, polygenic risk scores |

| Preventive Medicine | Family history assessment | Single-gene risk testing (e.g., BRCA) | Polygenic risk scores, integrated risk assessment |

Modern systems medicine integrates genomic data with other molecular profiling data, clinical information, and environmental exposures to create comprehensive models of health and disease [14]. These integrated models have the potential to transform healthcare from a reactive system focused on treating established disease to a proactive system aimed at maintaining health and preventing disease [14].

Future Directions and Emerging Applications

Technological Innovations and Converging Fields

The continued evolution of genomic technologies and systems approaches is creating new possibilities for biological research and medical application. Several emerging trends are particularly noteworthy:

Single-Cell Multi-Omics: Technologies for profiling genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, and proteomics at single-cell resolution are revealing previously unappreciated cellular heterogeneity and enabling reconstruction of developmental trajectories [24].

Spatial Omics and Tissue Imaging: Methods that preserve spatial context while performing molecular profiling are providing new insights into tissue organization and cell-cell communication [24].

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: AI approaches are accelerating the analysis of complex genomic datasets, identifying patterns that cannot be detected by human analysis alone, and generating hypotheses for experimental testing [24] [23].

CRISPR and Genome Editing: The development of precise genome editing technologies, built on the foundation of genomic sequence information, enables functional testing of genomic elements and therapeutic modification of disease-causing variants [24].

Synthetic Biology: Using engineering principles to design and construct biological systems with novel functions, supported by the foundational knowledge provided by the HGP and enabled by systems biology approaches [24].

These technological innovations are converging to create unprecedented capabilities for understanding, manipulating, and designing biological systems, with profound implications for basic research, therapeutic development, and broader biotechnology applications.

Expanding Applications Beyond Human Biomedicine

The impact of genomics and systems biology extends far beyond human medicine, influencing diverse fields including conservation biology, agricultural science, and industrial biotechnology [24]. Notable applications include:

Conservation Genomics: Using genomic sequencing to protect endangered species, track biodiversity through environmental DNA sampling, and guide conservation efforts by identifying populations with critical genetic diversity [24] [23].

Agricultural Improvements: Applying genomic technologies to enhance crop yields, improve nutritional content, and develop disease-resistant varieties through understanding plant genomic systems [24].

Microbiome Engineering: Manipulating microbial communities for human health, agricultural productivity, and environmental remediation based on systems-level understanding of microbial ecosystems [24].

Climate Change Resilience: Using genomic surveillance to track how climate change impacts disease patterns and species distribution, and identifying genetic variants that may help key species adapt to changing environments [24] [23].

These expanding applications demonstrate how the genomic revolution initiated by the HGP continues to transform diverse fields, creating new solutions to challenging problems in human health and environmental sustainability.

The Human Genome Project represents a pivotal achievement in the history of science, not only for its specific goal of sequencing the human genome but for its role in catalyzing a fundamental transformation in biological research [20] [21]. The project demonstrated the power of "big science" approaches in biology, established new norms for data sharing and collaboration, and provided the essential foundation for the emergence of systems biology as a dominant paradigm [20] [22].

The evolution from the HGP to modern integrative science represents a journey from studying biological components in isolation to understanding their functions within complex systems [14]. This transition has required the development of new technologies, analytical frameworks, and collaborative models that bring together diverse expertise across traditional disciplinary boundaries [20] [14]. The continued convergence of genomics, systems biology, and computational approaches promises to further accelerate progress in understanding biological complexity and addressing challenging problems in human health and disease.

The legacy of the Human Genome Project extends far beyond the sequence data it generated, encompassing a cultural transformation in how biological research is conducted and how scientific knowledge is shared and applied [21] [22]. As genomic technologies continue to advance and systems biology approaches mature, the foundational contributions of the HGP will continue to enable new discoveries and applications across the life sciences for decades to come.

Systems biology represents a fundamental shift in biological research, moving from a reductionist focus on individual components to a holistic approach that seeks to understand how biological elements interact to form functional systems [1] [2]. This paradigm recognizes that complex behaviors in living organisms emerge from dynamic interactions within biological networks, much like understanding an elephant requires more than just examining its individual parts [2]. The core principle of systems biology is integration—combining diverse data types through computational modeling to understand the entire system's behavior [3].

Biological networks serve as the fundamental framework for representing these complex interactions. By mapping the connections between cellular components, researchers can identify emergent properties that would be invisible when studying elements in isolation [3]. This network-centric perspective has become essential for unraveling the complexity of biological systems, from single cells to entire organisms. The advancement of multi-omics technologies has further accelerated this approach by enabling comprehensive measurement of biomolecules across different biological layers, providing the data necessary to construct and validate detailed network models [3].

This technical guide examines three primary classes of biological networks that form the backbone of cellular regulation: metabolic networks, cell signaling networks, and gene regulatory networks. Each network type possesses distinct characteristics and functions, yet they operate in a highly coordinated manner to maintain cellular homeostasis and execute complex biological programs. Understanding their architecture, dynamics, and methodologies for analysis is crucial for researchers aiming to manipulate biological systems for therapeutic applications.

Fundamental Concepts of Biological Networks

Graph Theory Foundations for Biological Networks

Biological networks are computationally represented using graph theory, where biological entities become nodes (vertices) and their interactions become edges (connections) [25]. This mathematical framework provides powerful tools for analyzing network properties and behaviors. The most common representations include:

- Undirected graphs: Used when relationships are bidirectional, such as in protein-protein interaction networks where interactions are mutual [25].

- Directed graphs: Employed when interactions have directionality, such as in regulatory networks where a transcription factor regulates a target gene [25].

- Weighted graphs: Incorporate relationship strengths through numerical weights, such as interaction confidence scores or reaction rates [25].

- Bipartite graphs: Model relationships between different node types, such as enzymes and the metabolic reactions they catalyze [25].

Key Network Properties and Metrics

The topological analysis of biological networks reveals organizational principles that often correlate with biological function. Several key metrics are essential for characterizing these networks:

- Node degree: The number of connections a node has. In directed networks, this separates into in-degree (incoming connections) and out-degree (outgoing connections) [25].

- Network connectivity: The overall connection density of a network, calculated as where E represents edges and N represents nodes [25].

- Centrality measures: Identify strategically important nodes, including betweenness centrality (nodes that bridge network regions) and closeness centrality (nodes that can quickly reach other nodes) [25].

- Modularity: The extent to which a network decomposes into structurally or functionally distinct modules or communities [25].

Table 1: Fundamental Graph Types for Representing Biological Networks

| Graph Type | Structural Features | Biological Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Undirected | Edges have no direction | Protein-protein interaction networks, protein complex associations |

| Directed | Edges have direction (source→target) | Gene regulatory networks, signal transduction cascades |

| Weighted | Edges have associated numerical values | Interaction confidence networks, metabolic flux networks |

| Bipartite | Two node types with edges only between types | Enzyme-reaction networks, transcription factor-gene networks |

Metabolic Networks

Architectural Principles and Functional Roles