Stochastic Modeling in Biochemical Systems: From Noise to Knowledge in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of stochastic modeling techniques for biochemical systems, essential for researchers and drug development professionals.

Stochastic Modeling in Biochemical Systems: From Noise to Knowledge in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of stochastic modeling techniques for biochemical systems, essential for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles that differentiate stochastic from deterministic approaches, especially critical for systems with low molecular copy numbers. The review covers key methodological advances, including algorithms for delayed reactions and model reduction strategies, illustrated with applications from gene regulation to pharmacogenomics. It further addresses common challenges in model robustness and accuracy, and offers a comparative analysis of model validation techniques. By synthesizing current research and tools, this article serves as a guide for leveraging stochastic models to understand cellular noise, improve therapeutic intervention strategies, and advance personalized medicine.

Why Noise Matters: The Foundations of Stochasticity in Biochemical Systems

In the mathematical modeling of biochemical systems, researchers traditionally rely on two fundamentally different approaches: deterministic models based on Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) and stochastic models governed by the Chemical Master Equation (CME). While ODEs follow the law of mass action and provide a continuous description of concentration changes, the CME captures the discrete, probabilistic nature of biochemical reactions where random fluctuations play a significant role [1] [2]. The choice between these frameworks carries profound implications for predicting system behavior, particularly in cellular signaling and regulatory circuits where molecular copy numbers can be small [1].

This Application Note provides a structured comparison of these modeling paradigms, highlighting scenarios where their predictions converge or diverge. We present practical protocols for implementing both approaches, visual tools for understanding their relationships, and guidance for selecting the appropriate methodology based on specific research contexts in drug development and systems biology.

Theoretical Foundations: ODEs vs. the CME

Model Formulations

Deterministic ODE Framework Ordinary Differential Equations model biochemical systems by describing the time evolution of molecular concentrations as continuous variables. Based on the law of mass action, ODEs define reaction rates as deterministic functions of reactant concentrations [1] [2]. For a system with M chemical species and R reactions, the concentration change of the i-th component is given by:

[ \dot{c}i = \sum{j=1}^{R} a{ij} \cdot kj \cdot \prod{l=1}^{M} cl^{\beta_{lj}} ]

where (ci) is the concentration of species i, (kj) is the deterministic rate constant for reaction j, (a{ij}) are stoichiometric coefficients, and (\beta{lj}) represents the number of molecules of species l required for reaction j [1].

Stochastic CME Framework The Chemical Master Equation models biochemical systems as discrete-state Markov processes, capturing the inherent randomness of molecular interactions. The CME describes the evolution of the probability distribution over all possible molecular states [1] [2]. For a system state vector n = (nâ‚, ..., nₘ) representing molecular counts, the CME is formulated as:

[ \dot{p}n(t) = \sum{j=1}^{R} [wj(n - aj) \cdot p{n-aj}(t) - wj(n) \cdot pn(t)] ]

where (pn(t)) is the probability of state n at time t, (wj(n)) is the reaction propensity function, and (aj) is the stoichiometric change vector for reaction j [1]. The propensity function follows (wj(n) = \kappaj \cdot \prod{i=1}^{M} \binom{ni}{\beta{ij}}), where (\kappa_j) is the stochastic reaction constant [1].

Quantitative Comparison of Modeling Approaches

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Deterministic ODE and Stochastic CME Approaches

| Feature | Deterministic ODEs | Stochastic CME |

|---|---|---|

| State Representation | Continuous concentrations | Discrete molecule counts |

| Reaction Kinetics | Deterministic rates based on mass action | Stochastic propensities based on combinatorial probabilities |

| System Description | Single trajectory for given initial conditions | Probability distribution over all possible states |

| Mathematical Form | System of differential equations | Markov process master equation |

| Rate Constant Relation | (k_j) (deterministic) | (\kappaj = kj \cdot V \cdot \prod{i=1}^{M} \frac{\beta{ij}!}{V^{\beta_{ij}}}) [1] |

| Computational Complexity | Generally lower (solving ODEs) | Generally higher (simulating/solving CME) |

| Preferred System Size | Large volumes, high copy numbers | Small volumes, low copy numbers |

Practical Protocols for Model Implementation

Protocol 1: ODE Modeling of Biochemical Systems

Principle: This protocol outlines the steps for constructing and analyzing deterministic ODE models of biochemical reaction networks using the law of mass action, suitable for systems with large molecular populations where stochastic effects are negligible.

Materials:

- Software Tools: MATLAB, Python with SciPy, COPASI, or similar ODE simulation environments

- Reagent Solutions: See Table 3 for computational research reagents

Procedure:

- Reaction Specification: Define all biochemical reactions in the system with appropriate stoichiometries

- Parameter Identification: Obtain kinetic parameters (rate constants) from literature or experimental data

- ODE Formulation: Convert reactions to ODEs using mass action kinetics

- For each species, write a differential equation

- For each reaction, add terms for production and consumption

- Initial Conditions: Set initial concentrations of all molecular species

- Numerical Integration: Solve the ODE system using appropriate numerical methods (e.g., Runge-Kutta)

- Validation: Compare model predictions with experimental data

- Sensitivity Analysis: Identify parameters with strongest influence on system behavior

Applications: Metabolic pathways, large-scale signaling networks, population dynamics [1]

Protocol 2: Stochastic Simulation of the CME

Principle: This protocol describes the implementation of stochastic models using the Gillespie algorithm or its variants, capturing inherent noise in biochemical systems with low molecular counts.

Materials:

- Software Tools: DelaySSA (R, Python, or MATLAB versions), StochPy, BioSimulator.jl [3]

- Reagent Solutions: See Table 3 for specialized stochastic simulation reagents

Procedure:

- System Definition: Specify molecular species, reactions, and corresponding propensities

- Stochastic Constants: Calculate stochastic rate constants from deterministic counterparts using the relation: (\kappaj = kj \cdot V \cdot \prod{i=1}^{M} \frac{\beta{ij}!}{V^{\beta_{ij}}}) [1]

- Initialization: Set initial molecular counts and simulation parameters

- Algorithm Selection: Choose appropriate stochastic simulation method:

- Direct Method: Exact Gillespie algorithm for small systems

- Tau-Leaping: Approximate method for larger systems

- Delay-SSA: For systems with delayed reactions [3]

- Trajectory Generation: Run multiple simulations to generate statistical ensemble

- Distribution Analysis: Compute probability distributions and moments from simulated trajectories

- Comparison with Deterministic: Contrast mean behavior with ODE predictions

Applications: Gene expression noise, cellular decision-making, bistable systems [1] [3]

Protocol 3: Hybrid Modeling for Multi-Scale Systems

Principle: Many biological systems contain both high-abundance and low-abundance components, requiring integrated approaches that combine deterministic and stochastic modeling.

Materials:

- Software Tools: Hybrid model solvers (e.g., COPASI, NFsim)

- Reagent Solutions: Combination of tools from Tables 3 and 4

Procedure:

- System Partitioning: Identify which system components require stochastic treatment (low copy numbers) and which can be modeled deterministically (high copy numbers)

- Interface Definition: Establish coupling mechanisms between stochastic and deterministic subsystems

- Integration Scheme: Implement appropriate numerical methods for hybrid simulation

- Validation: Compare hybrid model behavior with full stochastic and full deterministic implementations

- Performance Optimization: Balance computational efficiency with model accuracy

Applications: Metabolic networks with regulatory genes, signaling pathways with scarce transcription factors [1]

Visualizing the Modeling Approaches

Diagram 1: Decision workflow for selecting between ODE and stochastic modeling approaches based on system characteristics, particularly molecular copy numbers.

Critical Comparisons and Biological Implications

When ODE and Stochastic Predictions Diverge

Bistability and Bimodality A crucial distinction emerges in systems exhibiting multiple stable states. Deterministic ODE models can show bistability with two stable fixed points separated by an unstable steady state. In contrast, stochastic CME models describe bimodality in stationary probability distributions [1]. Importantly, these concepts do not always align:

- Bistable but Unimodal Systems: Deterministic models predict two stable states, but stochastic fluctuations can eliminate one mode

- Monostable but Bimodal Systems: Deterministic models predict one stable state, but noise-induced transitions create bimodal distributions [1]

Small System Effects In mesoscopic systems (intermediate sizes), stochastic fluctuations become significant and disrupt the correspondence between deterministic fixed points and stochastic distribution modes [1]. Key factors promoting these discrepancies include:

- Large stoichiometric coefficients

- Presence of nonlinear reactions

- Asymmetric fluctuation patterns [1]

Practical Implications for Biological Systems

Table 2: Application Domains for ODE vs. Stochastic Modeling Approaches

| Biological Process | Recommended Approach | Rationale | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Pathways | ODE models | High metabolite concentrations; noise averaging | [1] |

| Gene Expression | Stochastic CME | Low copy numbers of DNA/RNA; significant noise | [1] [2] |

| Signaling Cascades | Context-dependent | Varies with cascade stage and abundance | [1] |

| Cellular Decision-Making | Stochastic CME | Noise-driven transitions between states | [1] |

| Population Dynamics | ODE models | Large cell numbers; population averaging | [1] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Biochemical Modeling

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| COPASI | Software platform | ODE and stochastic modeling | User-friendly interface; parameter estimation |

| DelaySSA | Software package | Stochastic simulation with delays | R, Python, MATLAB implementations [3] |

| GillespieSSA | Algorithm | Exact stochastic simulation | Direct method implementation |

| BioSimulator.jl | Julia package | Stochastic simulation | High performance for large systems |

| SBML | Data format | Model exchange | Community standard for model sharing |

Advanced Considerations

Multi-Step Reactions and Time Delays

Many biochemical processes involve multi-step reactions that can be approximated using time delays in simplified models [4] [5]. However, constant time delays often provide inadequate approximations. State-dependent time delays that account for system dynamics offer more accurate representations of multi-step processes [4].

For mRNA degradation modeled as a multi-step process, the total molecule number follows complex kinetics that can be approximated by:

[ X(t) \approx x{10} \cdot e^{-kt} + \frac{y0 \cdot (kt)^{n-1} \cdot e^{-kt}}{(n-1)!} + \xi ]

where (\xi) represents remainder terms [4]. This demonstrates how simplified delay models capture essential features of complex multi-step processes.

Parameter Estimation Challenges

Parameter estimation for stochastic models presents distinct challenges compared to deterministic approaches. Dedicated methods like Multiple Shooting for Stochastic Systems (MSS) often outperform generic least squares approaches designed for deterministic models [6]. Key considerations include:

- Single stochastic trajectories contain limited information about underlying distributions

- Qualitative differences between stochastic and deterministic behaviors affect parameter identifiability

- Specialized algorithms account for intrinsic noise characteristics [6]

Deterministic ODE and stochastic CME approaches offer complementary perspectives on biochemical system dynamics. The choice between them should be guided by biological context, particularly molecular copy numbers and the importance of fluctuation-driven phenomena. For regulatory circuits requiring precise coordination, ODE modeling still provides relevant insights, but stochastic approaches are essential for capturing behavior at cellular and molecular scales where noise significantly influences system behavior [1]. As modeling frameworks continue to evolve, hybrid approaches that strategically combine both paradigms will likely provide the most powerful tools for understanding complex biological systems in drug development and basic research.

In biochemical systems research, the mesoscopic realm occupies a critical scale where biological processes are influenced by both deterministic laws and random molecular fluctuations. This occurs when the number of molecules involved is sufficiently low that random events can dramatically alter system behavior, making stochasticity essential rather than incidental. The model-informed drug discovery and development (MID3) paradigm has traditionally relied on deterministic models, often described by ordinary differential equations (ODEs), where the system's trajectory is fully determined by parameter values and initial conditions [7]. However, these models fail to capture intrinsic noise that becomes significant at low copy numbers, such as in gene expression, cellular decision-making, and signal transduction [8].

Stochastic effects become particularly important when modeling small populations or molecular counts because random events can produce qualitative changes in system behavior not predicted by deterministic approaches [7]. At the mesoscopic scale, biochemical reactions are fundamentally probabilistic events where the evolution of the system depends on consecutive random occurrences, best described by probability distributions rather than continuous concentrations [7]. This review establishes the critical importance of stochastic modeling approaches for researchers and drug development professionals working with systems where low copy numbers prevail, providing both theoretical foundations and practical methodologies for implementing these approaches in experimental and computational workflows.

Theoretical Foundations: From Deterministic to Stochastic Frameworks

Fundamental Differences Between Modeling Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Deterministic and Stochastic Modeling Approaches

| Feature | Deterministic Models | Stochastic Models |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Foundation | Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) [7] | Chemical Master Equation, Stochastic Simulation Algorithm [7] [8] |

| System Representation | Continuous concentrations [7] | Discrete molecule counts [7] |

| Outcome Prediction | Unique trajectory for given parameters [7] | Probability distribution of possible trajectories [7] |

| Computational Demand | Generally lower [7] | Higher (requires multiple simulations) [7] [8] |

| Treatment of Noise | Ignored or treated as external disturbance [7] | Incorporated as intrinsic system property [7] [8] |

| Steady States | Constant values [7] | Probability distributions [7] |

The transition from deterministic to stochastic modeling represents a fundamental shift in how biochemical systems are conceptualized and analyzed. Deterministic models, described by ODEs, assume that molecular concentrations change continuously and predictably over time. However, these models have two key limitations for mesoscopic systems: (1) they do not account for uncertainty in model dynamics, and (2) they are trapped in constant steady states that may not remain steady when stochasticity is considered [7].

In contrast, stochastic models incorporate intrinsic fluctuations as essential system properties. The master equation provides a mathematical description of this approach, defining a probability distribution for all possible system states over time [7]. For a simple birth-death process where each cell divides with rate β and dies with rate δ, the master equation allows computation of both the average population size and its variance, with the variance increasing over time when β > δ [7]. This variance, which reflects population heterogeneity, cannot be captured by deterministic approaches.

The Mesoscopic Flux Decomposition

In stochastic chemical kinetics, the mean concentration dynamics are governed by differential equations similar to classical chemical kinetics, expressed in terms of stoichiometry and time-dependent fluxes. However, each flux decomposes into two distinct components:

- Macroscopic term: Accounts for the effect of mean reactant concentrations on product synthesis rate, identical to classical deterministic fluxes [8]

- Mesoscopic term: Accounts for statistical correlations among interacting reactions, unique to stochastic formulations [8]

When all mesoscopic fluxes are zero (as in linear reaction systems), classical and stochastic kinetics yield identical mean concentration dynamics. However, for nonlinear systems with bimolecular reactions, nonzero mesoscopic fluxes induce qualitative and quantitative differences in both transient and steady-state behaviors [8]. These differences explain why stochastic models can predict behaviors impossible in deterministic frameworks, such as noise-induced transitions between phenotypic states in cellular populations.

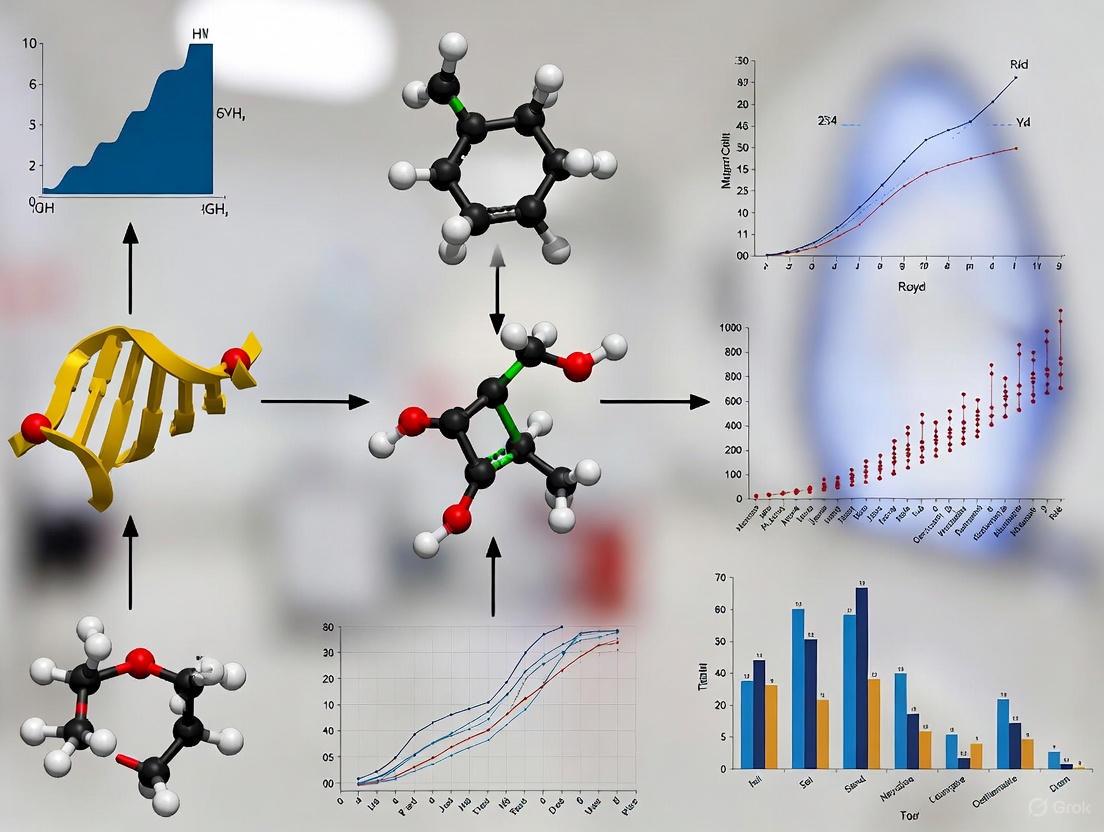

Diagram 1: Relationship between deterministic and stochastic modeling frameworks, highlighting the critical role of mesoscopic flux in capturing system stochasticity.

Quantitative Manifestations of Low Copy Number Effects

Experimental Evidence Across Disciplines

Table 2: Documented Stochastic Effects in Low Copy Number Systems

| System Type | Copy Number Range | Observed Stochastic Effect | Experimental Readout |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forensic DNA (LCN Typing) | <100 pg DNA (<~15 diploid genomes) [9] | Allelic dropout, peak height imbalance, increased stutter [9] [10] | STR profile inconsistencies between replicates [9] |

| Crayfish Mechanoreceptors | Not quantified | Stochastic resonance improving signal detection [11] | Signal-to-noise ratio in neural response [11] |

| Paddlefish Electroreceptors | Not quantified | Noise-enhanced plankton detection [11] | Successful strike distance range [11] |

| Biochemical Reactions (in silico) | <1000 molecules [8] | Divergence from deterministic predictions, novel steady states [8] | Mean concentration trajectories and stationary distributions [8] |

Low copy number (LCN) effects manifest quantitatively across diverse experimental systems. In forensic science, LCN DNA typing analyzes samples containing less than 100-200 pg of template DNA, which corresponds to approximately 15-30 diploid human genomes [9]. At these low levels, stochastic sampling effects during PCR amplification produce several characteristic phenomena: substantial imbalance between two alleles at heterozygous loci, complete allelic dropout, and increased stutter peaks [9]. These effects fundamentally limit reproducibility, as identical samples yield different profiles upon repeated analysis [9].

In neuroscience, stochastic resonance demonstrates how added noise can enhance detection of subthreshold signals in sensory systems. Crayfish mechanoreceptors show maximal signal-to-noise ratio in neural responses at intermediate noise levels [11]. Similarly, paddlefish hunting performance improves with optimal background electrical noise, expanding their successful strike range for detecting plankton [11]. These biological examples illustrate functional advantages of stochasticity in sensory processing.

Computational studies of biochemical reactions reveal that intrinsic fluctuations cause pronounced deviations from deterministic predictions at molecular counts below approximately 1000 [8]. The dimerization reaction 2A → B shows measurable differences between classical and stochastic kinetics even at moderate copy numbers, with divergences becoming dramatic near thermodynamic limits [8].

Practical Implications for Experimental Design

The quantitative evidence summarized in Table 2 necessitates specific experimental design considerations for mesoscopic systems:

- Replication requirements: LCN systems typically require 3-8 replicate measurements to establish consensus profiles, as used in forensic LCN typing [10]

- Threshold determination: Each laboratory must establish stochastic thresholds through validation studies specific to their assays and conditions [9]

- Noise optimization: Rather than minimizing all noise, systems exploiting stochastic resonance require identification of optimal noise levels for maximal signal detection [11] [12]

- Sample size considerations: Studies of heterogeneous cell populations must account for single-cell stochastic effects through appropriate sample sizes and single-cell analysis techniques

Experimental Protocols for Mesoscopic System Analysis

Gillespie Stochastic Simulation Algorithm

The Gillespie Stochastic Simulation Algorithm (SSA) provides exact simulations of possible trajectories from the chemical master equation by using Monte Carlo techniques to simulate individual reaction events [7]. Below is a detailed protocol for implementing SSA:

Principle: The algorithm generates statistically correct trajectories of a stochastic biochemical system by explicitly simulating each reaction event, accounting for the inherent randomness of molecular interactions at low copy numbers.

Materials:

- Computer with sufficient computational resources (SSA is computationally demanding for large systems) [7]

- Programming environment (Python, MATLAB, R, or C++)

- Well-defined biochemical reaction network with stoichiometry and propensity functions

Procedure:

- System Initialization:

- Define the initial state vector X(tâ‚€), containing molecular counts of all N species at initial time tâ‚€

- Specify reaction stoichiometry matrix S (N × M for N species and M reactions)

- Define propensity functions aáµ¢(X) for each reaction i

Parameter Setting:

- Set final simulation time T

- Initialize time t = tâ‚€

- Initialize state vector X = X(tâ‚€)

Iteration Loop (repeat until t > T): a. Calculate all propensity functions aáµ¢(X) for i = 1 to M b. Compute total propensity aâ‚€ = Σᵢ aáµ¢(X) c. If aâ‚€ = 0, exit loop (no further reactions possible) d. Generate two independent uniform random numbers râ‚, râ‚‚ ~ U(0,1) e. Calculate time to next reaction: Ï„ = (1/aâ‚€) ln(1/râ‚) f. Determine reaction index j such that Σᵢ₌â‚ʲâ»Â¹ aáµ¢(X) < râ‚‚aâ‚€ ≤ Σᵢ₌â‚ʲ aáµ¢(X) g. Update state vector: X = X + Sʲ (where Sʲ is the j-th column of S) h. Update time: t = t + Ï„ i. Record (t, X) if needed for output

Output Generation:

- Generate trajectory data: molecular counts over time

- Repeat simulation multiple times (typically 10,000+ runs) to obtain statistical distributions

- Calculate summary statistics: means, variances, covariances across ensemble

Validation and Quality Control:

- Verify algorithm implementation using simple systems with analytical solutions (e.g., birth-death process)

- Confirm that ensemble averages approach deterministic solutions for large molecular counts

- Check for conservation laws in closed systems

- Validate against known experimental data when available

Troubleshooting:

- For stiff systems (widely varying time scales), consider modified algorithms (Ï„-leaping, implicit SSA)

- If computational cost is prohibitive, reduce model complexity or apply moment closure techniques [8]

- For multimodal distributions, ensure sufficient simulation runs to capture all modes

Diagram 2: Workflow of the Gillespie Stochastic Simulation Algorithm for exact simulation of biochemical systems at the mesoscopic scale.

Low Copy Number DNA Profiling Protocol

The analysis of Low Copy Number (LCN) DNA represents a practical application of mesoscopic principles in forensic science, where stochastic effects dominate at template levels below 100-200 pg [9] [10].

Principle: LCN DNA profiling enhances detection sensitivity through increased PCR cycles (typically 34 vs standard 28) to analyze minute biological samples, acknowledging that stochastic effects make complete reproducibility unattainable [9] [10].

Materials:

- DNA extraction kit (silica-based or organic)

- Quantitative PCR system for DNA quantification

- AmpFlSTR SGM Plus or similar STR multiplex kit

- Thermal cycler

- Capillary electrophoresis system (e.g., Applied Biosystems 3100)

- Sterile consumables and dedicated pre-PCR workspace to minimize contamination

Procedure:

- Sample Collection and Preservation:

- Use gloves and face masks during collection

- Employ disposable instruments where possible

- Store samples in sterile containers at -20°C until processing

DNA Extraction:

- Process samples in dedicated pre-PCR clean room

- Include extraction negative controls to monitor contamination

- Elute DNA in low TE buffer or water

DNA Quantification:

- Use quantitative PCR for accurate measurement

- Note that samples <100 pg total DNA qualify as LCN

- Do not pre-amplify samples based on quantification alone

PCR Amplification:

- Set up reactions in clean PCR workspace

- Use 34 amplification cycles instead of standard 28

- Include positive and negative controls with each batch

- Perform at least two independent amplifications per sample

Electrophoresis and Detection:

- Inject samples using enhanced parameters (e.g., 3 kV for 20s vs standard 10s) [10]

- Analyze raw data with appropriate sizing and quantification software

Profile Interpretation:

- Generate consensus profile from replicate amplifications

- Apply stochastic threshold based on validation data

- Record all alleles, noting any drop-in or drop-out events

- Calculate random match probability with appropriate statistical models

Quality Control and Validation:

- Monitor laboratory background DNA levels through negative controls

- Establish laboratory-specific stochastic thresholds through validation studies [9]

- Limit drop-in rate to <30% per locus for reliable interpretation [10]

- Document all interpretation steps for transparency

Limitations and Considerations:

- LCN results are not reproducible in the conventional sense [9]

- Profiles should be used primarily for investigative leads rather than conclusive evidence [9]

- Mixture interpretation is particularly challenging and requires specialized expertise [9]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Mesoscopic System Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Mesoscopic Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Stochastic Simulation Software (e.g., StochPy, COPASI) | Exact simulation of biochemical systems using SSA and related algorithms [7] [8] | Modeling gene regulatory networks with low transcription factor copies [8] |

| Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Kits | Profiling gene expression heterogeneity in individual cells | Characterizing stochastic gene expression in cellular differentiation |

| Digital PCR Systems | Absolute quantification of low copy number nucleic acids without standard curves | Validating stochastic model predictions of DNA/mRNA copy numbers |

| AmpFlSTR SGM Plus Kit | Multiplex STR analysis for forensic LCN DNA typing [10] | Generating consensus profiles from low template DNA samples [9] [10] |

| High-Sensitivity Capillary Electrometers | Detection of weak electrophysiological signals in sensory systems | Studying stochastic resonance in neural coding [11] |

| Moment Closure Approximation Tools | Efficient computation of mean and variance dynamics without full stochastic simulation [8] | Analyzing large biochemical networks where SSA is computationally prohibitive [8] |

| Epocholeone | Epocholeone | Epocholeone is a semi-synthetic plant growth regulator for research use only (RUO). Study its effects on cereal crop growth and development. |

| C.I. Disperse Red 43 | C.I. Disperse Red 43, CAS:12217-85-5, MF:ClO4 | Chemical Reagent |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

Stochastic modeling approaches provide critical insights throughout the pharmaceutical development pipeline, particularly for systems where low copy numbers or small populations create significant variability [7] [13].

Cellular Heterogeneity in Drug Response

In drug discovery, stochastic models help explain heterogeneous responses in genetically identical cell populations. This heterogeneity arises from stochastic fluctuations in key signaling molecules, drug targets, or metabolic enzymes present at low copy numbers per cell [7]. For example, cancer cell populations may exhibit fractional killing in response to chemotherapy, where only a subset of cells die despite genetic identity, due to pre-existing fluctuations in apoptotic pathway components [7]. Implementing stochastic models in this context involves:

- Quantifying expression distributions of drug targets in single cells

- Modeling signal transduction networks with explicit molecular noise

- Predicting population-level responses from single-cell stochasticity

- Optimizing combination therapies to overcome resistance arising from stochastic phenotypic switching

Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) Variability

Stochastic PK/PD models capture variability in drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion that cannot be explained by demographic factors alone [7] [13]. When applied to small populations or rare diseases, these models account for random events that significantly impact therapeutic outcomes [7]. Implementation protocols include:

- Incorporating stochastic elements into classical compartment models

- Quantifying intrinsic versus extrinsic noise contributions

- Establishing confidence intervals for parameter estimates in small populations

- Designing optimized clinical trials that account for expected variability

Manufacturing Process Optimization

Stochastic simulation aids pharmaceutical manufacturing by modeling random events in bioprocessing, including:

- Cell-to-cell variability in bioreactor populations [13]

- Stochastic enzyme kinetics in biocatalysis [13]

- Random equipment failures and maintenance schedules [13]

- Variability in raw material quality and composition [13]

These applications enable more robust process design, better quality control strategies, and improved reliability in drug production [13].

Diagram 3: Applications of stochastic modeling throughout the drug development pipeline, highlighting specific mesoscopic considerations at each stage.

The mesoscopic realm represents a critical domain where low copy numbers make stochasticity essential for accurate system characterization. Traditional deterministic models fail to capture the intrinsic fluctuations that dominate system behavior at these scales, potentially leading to incorrect predictions and suboptimal decisions in research and drug development. The experimental protocols, computational tools, and theoretical frameworks presented here provide researchers with practical approaches for addressing these challenges. As pharmaceutical science increasingly focuses on personalized medicine and rare diseases—contexts where small population effects prevail—the strategic implementation of stochastic modeling will become essential for robust therapeutic development. By embracing rather than ignoring system randomness, researchers can unlock more accurate predictions and more effective interventions across the drug development pipeline.

In biochemical systems, even genetically identical cells exposed to homogeneous environments can exhibit remarkable phenotypic variation [14]. This heterogeneity arises from two fundamental sources of stochasticity: intrinsic noise, generated by the inherent randomness of biochemical reactions within a cell, and extrinsic noise, stemming from variations in the cellular state or environment [15]. Intrinsic noise emerges from the stochastic nature of molecular interactions, such as transcription factor binding to promoters or the random timing of transcription and translation events, and becomes particularly significant when molecular copy numbers are low [16] [17]. Extrinsic noise, in contrast, originates from cell-to-cell differences in global cellular factors such as cell cycle stage, varying concentrations of ribosomes or polymerases, and other upstream regulators that affect gene expression dynamics broadly [18] [15]. Distinguishing between these noise sources is crucial for understanding how biological systems control cell fate decisions, respond to stimuli, and maintain robustness despite molecular stochasticity.

The experimental demonstration and quantification of these noise sources became possible through pioneering work utilizing dual-reporter systems, where two distinguishable fluorescent proteins (e.g., CFP and YFP) are expressed under identical promoters in the same cell [16] [15]. In such systems, intrinsic noise produces differential expression between the two reporters within a single cell, while extrinsic noise causes coordinated fluctuations of both reporters that differ between cells [15]. This framework has enabled researchers to dissect the contributions of each noise type to overall phenotypic heterogeneity across diverse biological contexts, from bacterial persistence to mammalian cell signaling and developmental patterning [19] [15].

Quantitative Definitions and Measurement Approaches

Mathematical Framework for Noise Quantification

The total noise in gene expression is quantitatively defined as the squared coefficient of variation of the copy numbers of a gene product. For a protein with copy number (n), the total noise (\eta_\mathrm{tot}^2) is given by:

\begin{align} \eta_\mathrm{tot}^2 = \frac{\left\langle n^2\right\rangle - \left\langle n\right\rangle ^2}{\left\langle n\right\rangle ^2} \end{align}

where (\langle n \rangle) denotes the expectation value of (n) [16]. According to the law of total variance, this total noise can be decomposed into intrinsic and extrinsic components:

\begin{align} \eta\mathrm{tot}^2 = \eta\mathrm{int}^2 + \eta_\mathrm{ext}^2 \end{align}

where (\eta\mathrm{int}^2) represents the intrinsic component and (\eta\mathrm{ext}^2) represents the extrinsic component [20].

In the hierarchical model for two-reporter experiments, where (Ci) and (Yi) represent the expression measurements for two identical reporters in cell (i), the intrinsic noise arises from the variance within a fixed cellular environment, while the extrinsic noise comes from the variance between different cellular environments [20]. Formally:

\begin{align} E[Var[Ci|Zi]] &= \sigma^2 \quad \text{(intrinsic noise)} \ Var[E[Ci|Zi]] &= \sigma_\mu^2 \quad \text{(extrinsic noise)} \end{align}

where (Z_i) represents the environment of cell (i) [20].

Experimental Protocol: Dual-Reporter Noise Measurement

Purpose: To quantify intrinsic and extrinsic noise contributions in gene expression using a dual-reporter system.

Materials:

- Plasmid constructs with identical promoters driving expression of two distinguishable fluorescent proteins (e.g., CFP and YFP)

- Appropriate host cells (bacterial, yeast, or mammalian)

- Fluorescence microscopy system with capabilities for time-lapse imaging and multiple fluorescence channels

- Image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, CellProfiler)

- Data analysis environment (e.g., R, Python with necessary packages)

Procedure:

Strain Construction: Integrate two reporter genes (CFP and YFP) under control of identical promoters at defined genomic loci, ensuring similar mean gene copy numbers by placing them at equidistant positions from the origin of replication [16].

Cell Culture and Imaging:

- Grow cells under appropriate conditions to mid-log phase.

- For time-lapse experiments, transfer cells to microscopy-appropriate chambers maintaining constant environmental conditions.

- Acquire time-lapse images of both fluorescence channels at regular intervals (e.g., every 10-30 minutes) for several cell generations.

Image Analysis:

- Segment individual cells in each frame using bright-field or phase-contrast images.

- Quantify fluorescence intensity in both channels for each cell, subtracting background fluorescence.

- Track cells through divisions to establish lineages.

Noise Calculation:

- For each cell (i) at a given time point, obtain paired fluorescence measurements ((ci, yi)).

Calculate the following statistics across a population of (n) cells:

\begin{align} \eta\mathrm{int}^2 &= \frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^n \frac{(ci - yi)^2}{2\bar{c}\bar{y}} \ \eta\mathrm{ext}^2 &= \frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^n \frac{ci \cdot yi - \bar{c}\bar{y}}{\bar{c}\bar{y}} \ \eta\mathrm{tot}^2 &= \eta\mathrm{int}^2 + \eta_\mathrm{ext}^2 \end{align}

where (\bar{c} = \frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^n ci) and (\bar{y} = \frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^n yi) [20].

Validation: Verify that the overall fluorescence distributions for both reporters are statistically indistinguishable after appropriate scaling [16].

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Ensure promoters are truly identical and reporter genes are integrated at positions with similar chromatin environments.

- Account for differences in maturation times and photostability between fluorescent proteins.

- For mammalian cells, consider using allelic reporters with two different alleles of the same gene [15].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework and experimental workflow for distinguishing intrinsic and extrinsic noise using the dual-reporter system:

Figure 1: Experimental framework for distinguishing intrinsic and extrinsic noise using dual-reporter systems. Intrinsic noise produces differential expression between two identical reporters within the same cell, while extrinsic noise causes coordinated fluctuations that vary between cells.

Advanced Measurement Techniques

Beyond the standard dual-reporter approach, several advanced methods have been developed for more precise noise characterization:

Single-Molecule RNA FISH: This fixed-cell approach provides absolute transcript counts with single-molecule resolution, enabling precise quantification of mRNA fluctuations and transcriptional bursting parameters [15]. The protocol involves designing fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes complementary to target mRNAs, fixing cells, hybridizing probes, and imaging with high-resolution microscopy. This method has revealed that transcription occurs in stochastic bursts with geometrically distributed sizes and exponentially distributed intervals [15].

Live-Cell mRNA Tracking: Using MS2-GFP or related systems, researchers can monitor transcription in real time in individual living cells [15]. This involves engineering genes with multiple MS2 stem-loops in their 3' UTR and expressing a fusion of GFP to the MS2 coat protein. The method enables direct observation of transcriptional bursting kinetics and has demonstrated that gene activation/inactivation dynamics follow a random telegraph process.

Flow Cytometry with Dual Reporters: For high-throughput population analyses, flow cytometry can be used with dual fluorescent reporters, though this sacrifices temporal information and single-cell tracking capabilities [17].

Origins of Intrinsic Noise

Intrinsic noise stems from the fundamental stochasticity of discrete biochemical reactions involving small numbers of molecules. Key sources include:

Transcriptional Bursting: Genes switch randomly between active and inactive states, leading to bursts of mRNA synthesis separated by refractory periods [15]. In E. coli, this bursting behavior has been directly observed using MS2-GFP tags, with transcription occurring in quantal bursts with geometrically distributed sizes and exponentially distributed intervals [15]. The physical basis for bursting may include DNA supercoiling accumulation and release, as demonstrated by smRNA FISH studies showing that supercoiling buildup during transcription can temporarily halt the process until released by topoisomerases [15].

Promoter State Fluctuations: The binding and unbinding of transcription factors to regulatory sites occurs stochastically, creating variability in transcriptional probability. In phage λ, for example, the complex binding landscape involving six operator sites and DNA looping creates 113 possible binding configurations, each with different transcriptional activities, contributing significantly to expression noise [14].

Translation Stochasticity: The random timing of translation initiation and elongation, particularly for low-abundance mRNAs, creates additional protein-level noise. Each mRNA molecule can be translated multiple times in a burst, but the number of proteins produced per mRNA follows a geometric distribution [14].

Origins of Extrinsic Noise

Extrinsic noise arises from cell-to-cell differences in global cellular factors that affect gene expression broadly:

Cellular State Heterogeneity: Differences in cell cycle stage, cellular volume, growth rate, and metabolic status create substantial variability in gene expression capacity across a population [18] [17]. In the p53 system, for instance, cellular heterogeneity greatly determines the fraction of cells that exhibit oscillatory behavior following DNA damage [18].

Global Resource Fluctuations: Variations in the concentrations of essential gene expression components such as RNA polymerases, ribosomes, and ATP pools affect all transcriptional and translational processes simultaneously [15] [14]. These global factors create correlated fluctuations across multiple genes.

Upstream Signaling Variability: Heterogeneity in signaling pathway activation states, even in unstimulated cells, creates pre-existing biases in cellular responses [17]. For example, in the p53 network, extrinsic noise with proper strength and correlation time contributes significantly to oscillatory variability in individual cells [18].

Environmental Gradients: Despite efforts to maintain homogeneous conditions, microscopic gradients of nutrients, gases, or signaling molecules in cell cultures can create positional effects that manifest as extrinsic noise.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and sources of intrinsic and extrinsic noise:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Noise Sources

| Characteristic | Intrinsic Noise | Extrinsic Noise |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Stochasticity in biochemical reactions within a single cell | Variation due to differences in cellular state or environment |

| Primary Sources | - Transcriptional bursting- Promoter state fluctuations- Translation stochasticity- Low copy number effects | - Cell cycle stage differences- Growth rate variation- Global resource fluctuations- Upstream signaling heterogeneity |

| Dual-Reporter Signature | Different expression between identical reporters in the same cell | Similar expression between reporters in the same cell, but different between cells |

| Mathematical Representation | Variance within a fixed cellular environment: (E[Var[Ci|Zi]]) | Variance between cellular environments: (Var[E[Ci|Zi]]) |

| Typical Timescales | Short (seconds to minutes) | Longer (minutes to hours) |

| Dependence on Copy Number | High at low copy numbers, decreases with increasing copy number | Less dependent on specific copy numbers |

| Example Systems | - Phage λ cI expression [14]- Transcriptional bursting in E. coli [15] | - p53 oscillations [18]- Cell-to-cell signaling heterogeneity [17] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Noise Characterization Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Reporters | CFP, YFP, GFP variants, RFP, mCherry | Dual-reporter noise quantification; live-cell imaging | Choose spectrally distinct, photostable variants with similar maturation times |

| Single-Molecule FISH Probes | Quasar 670, Cy5, TAMRA labeled oligos | Absolute mRNA counting; transcriptional burst analysis | Design 30-50 oligos per mRNA target; optimize hybridization conditions |

| Live-Cell RNA Tagging Systems | MS2, PP7, CasFISH | Real-time transcription imaging | Engineer multiple stem-loops (typically 24x) in 3' UTR; express matching coat protein fusions |

| Stochastic Model Systems | Phage λ lysogens [14], p53 dynamics [18], synthetic genetic circuits | Well-characterized systems for noise mechanism studies | Select systems with appropriate timescales and measurable phenotypes |

| Analysis Tools | noise R package [20], torchsde [21], CellProfiler, TrackMate | Quantification, simulation, and image analysis | Validate algorithms with synthetic data; account for measurement noise |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, recombinase-mediated cassette exchange | Precise reporter integration at defined genomic loci | Target neutral "safe harbor" loci; verify single-copy integration |

Case Studies in Noise Research

Noise in the p53 Oscillation System

The p53 tumor suppressor protein exhibits oscillatory behavior in response to DNA damage, with significant variability in both amplitude and period between individual cells [18]. Research has dissected the contributions of cellular heterogeneity, intrinsic noise, and extrinsic noise to this variability using a minimal network model comprising the ATM-p53-Wip1 and p53-Mdm2 negative feedback loops.

Experimental Approach:

- Live-cell imaging of p53 dynamics in individual cells using fluorescent reporters

- Computational modeling with stochastic differential equations

- Separation of noise sources using binomial Ï„-leap algorithm for intrinsic noise and Ornstein-Uhlenbeck processes for extrinsic noise

Key Findings:

- Cellular heterogeneity primarily determines the fraction of oscillating cells in a population

- Intrinsic noise has minimal impact on p53 variability given the large numbers of molecules involved

- Extrinsic colored noise with proper strength and correlation time significantly contributes to oscillatory variability in individual cells

- The combination of all three noise sources reproduces experimental observations, suggesting that long correlation times of colored noise are essential for p53 variability [18]

Protocol Implications: When studying oscillatory systems, account for both the strength and correlation time of extrinsic noise, as these parameters significantly impact system behavior.

DNA Looping Effects in Phage λ Lysogeny

The cI protein in phage λ lysogens maintains the lysogenic state, and its expression shows remarkable variation despite genetic identity [14]. The complex regulatory system with six operator sites and DNA looping provides a sophisticated model for studying how regulatory architecture affects noise.

Experimental Approach:

- Stochastic differential equation modeling of the cI expression network

- Analysis of 113 possible binding configurations between CI and operators

- Quantification of noise contributions from gene regulation, transcription, translation, and cell growth

Key Findings:

- DNA looping has context-dependent effects on noise: it reduces noise when providing autorepression (as in wild type) but increases noise when autorepression is defective (as in certain mutants)

- The system shows extraordinarily large noise when binding affinity places it in a transition region between monostable and bistable regimes

- Cell growth contributes non-negligible extrinsic noise that increases with gene expression level

- The two-step expression model (considering both mRNA and protein fluctuations) explains significantly more noise than one-step models [14]

Protocol Implications: When modeling gene expression noise, include both mRNA and protein dynamics, and account for DNA binding configurations when studying regulated promoters.

Noise in Developmental Patterning

Morphogen-controlled toggle switches convert continuous morphogen gradients into discrete cell fate boundaries during development. These systems exhibit surprising sensitivity to intrinsic noise, which fundamentally alters both patterning dynamics and steady-state boundaries [19].

Experimental and Modeling Approach:

- Exact numerical simulations of kinetic reactions

- Chemical Langevin Equation approaches

- Minimum Action Path theory to analyze stochastic switching

Key Findings:

- Intrinsic noise produces a patterning wave that propagates away from the morphogen source

- The final boundary position differs from deterministic predictions

- The dramatic increase in patterning time near the boundary predicted by deterministic models is substantially reduced by stochastic switching

- Gene expression noise can create a traveling wave that may never reach steady state in biologically relevant timeframes [19]

Protocol Implications: For developmental systems, analyze both transient dynamics and steady states, as noise can qualitatively alter the temporal progression of pattern formation.

Computational Methods and Data Analysis

Stochastic Modeling Approaches

Computational methods are essential for interpreting noisy single-cell data and building predictive models. Several approaches have been developed:

Chemical Master Equation: This approach provides the most complete description of stochastic biochemical systems by tracking the probability distribution of all molecular species over time. However, it becomes computationally intractable for large systems [14].

Stochastic Differential Equations (SDEs): SDEs extend deterministic ODE models by adding noise terms, providing a continuous approximation of discrete stochastic processes. The chemical Langevin equation is a common SDE formulation that approximates the master equation when copy numbers are sufficiently high [21] [14].

Hierarchical Markov Models: These models separate intrinsic and extrinsic noise contributions by explicitly modeling cellular state variables that evolve on slower timescales than molecular reactions [21].

END-nSDE Framework: The recently developed Extrinsic-Noise-Driven neural Stochastic Differential Equation framework uses Wasserstein distance to reconstruct SDEs from heterogeneous cell population data, specifically accounting for how extrinsic noise modulates system dynamics [21].

The following diagram illustrates the computational framework for analyzing and modeling heterogeneous single-cell data:

Figure 2: Computational framework for analyzing heterogeneous single-cell data. Multiple data types inform both mechanistic and data-driven modeling approaches, leading to specific biological applications and insights.

Protocol: SDE Modeling for Noise Analysis

Purpose: To implement stochastic differential equations for simulating and analyzing noise in biochemical systems.

Materials:

- Programming environment (Python, R, or MATLAB)

- SDE solution algorithms (Euler-Maruyama, Milstein, or higher-order methods)

- Parameter estimation tools (maximum likelihood, Bayesian inference)

- Data visualization libraries

Procedure:

System Definition:

- Identify molecular species and reactions in the system

- Write deterministic rate equations (ODEs) for the system

- Determine the noise structure based on the reaction stoichiometry

SDE Formulation:

Convert ODEs to SDEs using the chemical Langevin equation framework:

\begin{align} dXi = \sumj S{ij} aj(\mathbf{X}) dt + \sumj S{ij} \sqrt{aj(\mathbf{X})} dWj \end{align}

where (Xi) are molecular concentrations, (S{ij}) is the stoichiometry matrix, (aj) are reaction propensities, and (dWj) are Wiener processes [14]

Numerical Simulation:

Implement the Euler-Maruyama method for basic SDE integration:

\begin{align} Xi(t + \Delta t) = Xi(t) + \sumj S{ij} aj(\mathbf{X}(t)) \Delta t + \sumj S{ij} \sqrt{aj(\mathbf{X}(t))} \sqrt{\Delta t} N_j(0,1) \end{align}

where (N_j(0,1)) are independent standard normal random variables

Parameter Estimation:

- For known data, use maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods to estimate parameters

For the END-nSDE framework, minimize the temporally decoupled squared W2-distance loss function:

\begin{align} \tilde{W}2^2(\mu, \hat{\mu}) = \int0^T \inf{\pi \in \Pi(\mu(t), \hat{\mu}(t))} \mathbb{E}\pi[||X(t) - \hat{X}(t)||^2] dt \end{align}

where (\mu(t)) and (\hat{\mu}(t)) are distributions of observed and simulated trajectories [21]

Noise Decomposition:

- Run simulations with and without extrinsic noise sources

- Calculate intrinsic and extrinsic noise contributions using variance decomposition methods

- Compare with experimental dual-reporter data when available

Validation:

- Verify that simulated means and variances match experimental data

- Check that noise scaling with expression level follows expected relationships

- Ensure numerical stability by testing different time steps and simulation algorithms

Implications for Drug Development and Disease

Cellular heterogeneity has profound implications for understanding disease mechanisms and developing therapeutic strategies. In cancer, nongenetic heterogeneity contributes to some of the most challenging clinical problems, including metastasis, invasion, and the emergence of drug-resistant cells [17]. Non-genetic heterogeneity can drive fractional killing in response to therapeutics, where only a subset of cells in a population is killed by treatment, potentially leading to tumor recurrence [17].

Therapeutic Implications:

- Bet-hedging strategies: Some cancer cell populations exploit noise to maintain subpopulations in transient drug-tolerant states, complicating treatment [15] [17]

- Signaling heterogeneity: Pre-existing variability in signaling pathway activation creates differential therapeutic responses in genetically identical cells [17]

- Combination therapies: Targeting multiple pathway components simultaneously may help overcome heterogeneity-driven treatment resistance

- Timing strategies: Leveraging knowledge of noise-driven dynamics to optimize drug administration schedules

Research Directions:

- Develop methods to distinguish between intrinsic and extrinsic sources of therapeutic resistance

- Identify "master regulator" molecules that control cell state transitions despite noise

- Design drugs that alter noise characteristics rather than just mean expression levels

- Explore therapeutic strategies that force heterogeneous populations into more uniform, treatable states

Understanding and controlling cellular heterogeneity represents a frontier in precision medicine, with potential to address some of the most persistent challenges in cancer therapy and other diseases involving nongenetic variability.

In biochemical systems, particularly at the cellular level, the small numbers of molecules involved in key reactions lead to inherent random fluctuations that cannot be captured by traditional deterministic models. These discrete stochastic behaviors are crucial for understanding critical biological phenomena including gene expression variability, cellular differentiation, and drug response heterogeneity. Two fundamental theoretical frameworks—the Chemical Master Equation (CME) and the Gillespie Algorithm (GA)—provide the mathematical foundation for accurately modeling these stochastic biochemical systems. The CME represents a complete probabilistic description of a chemical reaction system, while the GA provides an efficient computational method for generating exact stochastic trajectories of the system state over time [22]. These approaches are particularly valuable for mesoscopic systems where molecular populations are small enough to exhibit significant stochasticity yet large enough to require statistical characterization.

The importance of these frameworks extends across multiple domains of biochemical research and drug development. In therapeutic development, understanding the stochastic nature of biochemical reactions helps explain variability in drug response and enables the design of more robust therapeutic interventions. For systems biology, these tools provide insight into emergent behaviors in complex regulatory networks that cannot be predicted from deterministic models alone. The CME and GA have become indispensable for researchers investigating noise-driven biological phenomena such as metabolic switching, genetic oscillators, and epigenetic memory [23] [22].

Theoretical Foundations

The Chemical Master Equation (CME)

The Chemical Master Equation is a differential-difference equation that describes the time evolution of the probability distribution for all possible molecular states in a biochemical system. For a system comprising N chemical species and J chemical reactions, the CME governs the probability P(n,t) of finding the system in state n = {nâ‚, nâ‚‚, ..., nâ‚™} at time t. The general form of the CME is given by:

$$ \frac{dP(\mathbf{n},t)}{dt} = \sum{\mu=1}^{J} [a\mu(\mathbf{n} - \mathbf{\nu}\mu)P(\mathbf{n} - \mathbf{\nu}\mu,t) - a_\mu(\mathbf{n})P(\mathbf{n},t)] $$

Here, a$μ$(n) represents the propensity function of reaction μ, which describes the probability that reaction μ occurs in the next infinitesimal time interval given the current state n. The vector ν$μ$ specifies the stoichiometric change in molecular counts resulting from reaction μ [23] [22]. The propensity functions are determined by the nature of each reaction: for a unimolecular reaction of the form S₠→ products, a(x) = cxâ‚, where c is the stochastic rate constant; for a bimolecular reaction Sâ‚ + Sâ‚‚ → products, a(x) = cxâ‚xâ‚‚ [24].

The CME can be represented more formally using state vectors and creation/annihilation operators from quantum mechanics [23] [25]. Defining the state vector |ψ(t)⟩ = ΣP(n,t)|n⟩, the CME can be written as d|ψ(t)⟩/dt = Ĥ|ψ(t)⟩, where Ĥ is the evolution operator constructed from propensity functions and state change vectors [25]. This formulation enables the application of various mathematical techniques for analysis and approximation.

A key characteristic of biochemical systems in their native environments is that they are often maintained in Nonequilibrium Steady States (NESS) sustained by continuous chemical energy input [22]. Unlike equilibrium systems that obey detailed balance and time-reversal symmetry, NESS systems exhibit net probability fluxes through chemical states, enabling functions such as biological sensing, information processing, and energy transduction that would be impossible at thermodynamic equilibrium.

The Gillespie Algorithm (GA)

The Gillespie Algorithm, also known as the Stochastic Simulation Algorithm (SSA), is an exact procedure for numerically simulating the time evolution of a chemically reacting system [26]. Rather than directly solving the CME—which is often analytically intractable for all but the simplest systems—the GA generates statistically correct trajectories of the system state by simulating individual reaction events. The algorithm is mathematically equivalent to the CME but avoids the memory storage limitations associated with directly solving the high-dimensional CME [23].

The theoretical foundation of the GA rests on the function p(τ,j|x,t), which represents the probability density that, given the current state X(t) = x, the next reaction will occur in the infinitesimal time interval [t+τ, t+τ+dτ) and will be reaction Rⱼ. This joint probability density function factors as:

$$ p(\tau,j|\mathbf{x},t) = aj(\mathbf{x})e^{-a0(\mathbf{x})\tau} = \underbrace{a0(\mathbf{x})e^{-a0(\mathbf{x})\tau}}{\text{Time to next reaction}} \times \underbrace{\frac{aj(\mathbf{x})}{a0(\mathbf{x})}}{\text{Reaction identity probability}} $$

where a₀(x) = Σₖaₖ(x) represents the total propensity of all reactions [24]. This factorization reveals that the time τ to the next reaction follows an exponential distribution with mean 1/a₀(x), while the reaction index j is independently selected with probability proportional to its propensity aⱼ(x) [26] [24].

Table 1: Key Components of the Gillespie Algorithm Framework

| Component | Mathematical Expression | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Propensity Function | a(x)dt = probability of reaction occurring in next dt | Determined by molecularity and reaction mechanism |

| State-Change Vector | νⱼ = (νâ‚â±¼, ..., νₙⱼ) | Net change in molecular counts for each species after reaction j |

| Waiting Time Distribution | Ï„ ~ Exponential(1/aâ‚€(x)) | Time between reaction events in a well-mixed system |

| Reaction Selection Probability | P(j) = aâ±¼(x)/aâ‚€(x) | Competition among possible reaction channels |

Practical Implementation: Protocols and Methodologies

Direct Method Implementation of the Gillespie Algorithm

The most straightforward implementation of the GA is the Direct Method, which follows these computational steps [26] [24]:

- Initialization: Set initial molecular counts x = xâ‚€ and simulation time t = tâ‚€.

- Propensity Calculation: Compute all propensity functions aⱼ(x) for j = 1,...,M and their sum a₀(x) = Σⱼaⱼ(x).

- Waiting Time Generation: Generate a random number râ‚ from U(0,1) and compute the waiting time Ï„ = (1/aâ‚€(x))·ln(1/râ‚).

- Reaction Selection: Generate a second random number râ‚‚ from U(0,1) and select the smallest integer j satisfying Σₖ₌â‚ʲ aâ‚–(x) > râ‚‚aâ‚€(x).

- State Update: Update the system state x ↠x + νⱼ and time t ↠t + τ.

- Iteration: Return to step 2 until a termination condition is satisfied (e.g., t ≥ t_max).

Diagram 1: Workflow of the Gillespie Algorithm Direct Method

Several optimized formulations of the SSA have been developed to improve computational efficiency. The Next Reaction Method uses a more sophisticated data structure to manage putative reaction times, while the Optimized Direct Method and Sorting Direct Method optimize the reaction selection step by pre-ordering or dynamically reordering reactions according to their propensities [24]. For large systems, the Logarithmic Direct Method reduces the computational complexity of both the reaction selection and state update steps using tree-based data structures [24].

CME-GA Hybrid Method for Sub-Network Simulation

For complex biochemical networks, a hybrid approach that combines the CME and GA can provide significant computational advantages when only partial information about the system is required [23] [25]. This method partitions the reaction network into two parts: one subset of species and reactions is simulated stochastically using the GA, while the remaining sub-network is modeled by solving its CME. The solution to the CME portion is fed into the GA to update propensities, avoiding the need to solve the CME or stochastically simulate the entire network [23].

The protocol for implementing the CME-GA hybrid method involves:

- Network Partitioning: Divide the reaction network into two parts: Gâ‚ (to be simulated via GA) and Gâ‚‚ (to be modeled via CME).

- CME Solution: For sub-network Gâ‚‚, solve the CME either analytically or numerically to obtain the time-dependent probability distribution of its molecular species.

- Propensity Coupling: Use the CME solution for Gâ‚‚ to compute the effective propensities for reactions that connect the two sub-networks.

- Hybrid Simulation: Implement the GA for Gâ‚ while continuously updating propensities based on the CME solution for Gâ‚‚.

- Data Collection: Record the trajectory of species in Gâ‚, acknowledging that most information about Gâ‚‚ is lost in the process [23].

This approach has been demonstrated to be at least an order of magnitude faster than traditional stochastic simulation algorithms while maintaining high accuracy, making it particularly valuable for studying specific components of large biochemical networks [23] [25].

Differentiable Gillespie Algorithm for Parameter Estimation

Recent advances have incorporated deep learning methodologies into stochastic simulation through the Differentiable Gillespie Algorithm (DGA) [27]. The DGA approximates the discontinuous operations in the traditional GA (specifically the reaction selection step) using continuous, differentiable functions, enabling gradient calculation via automatic differentiation. This allows researchers to efficiently estimate kinetic parameters from experimental data and design biochemical networks with desired properties.

The key modification in the DGA replaces the discontinuous reaction selection step, which uses Heaviside step functions, with a smooth approximation using sigmoid functions:

$$ \sigma(y) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-y/a}} $$

where the hyperparameter a controls the steepness of the sigmoid [27]. This approximation enables the calculation of gradients with respect to kinetic parameters, facilitating the use of gradient-based optimization for parameter estimation and network design.

Table 2: Comparison of Stochastic Simulation Approaches

| Method | Computational Complexity | Accuracy | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Gillespie Algorithm | O(M) per reaction event | Statistically exact | Small to medium networks, validation studies |

| CME-GA Hybrid | Reduced by partitioning | High for sub-network | Large networks with focused interest areas |

| Tau-Leaping | O(1) per time leap | Approximate for large Ï„ | Systems with large molecular populations |

| Differentiable GA | Similar to GA plus gradient computation | Approximate but differentiable | Parameter estimation, network design |

| Delayed SSA | Similar to GA with delay tracking | Exact for fixed delays | Multi-step processes with significant time delays |

Advanced Methodologies and Extensions

Handling Multi-Step Reactions with State-Dependent Delays

Many biochemical processes, such as mRNA degradation, protein synthesis, and signal transduction, involve multi-step reactions that pose challenges for stochastic modeling [4] [5]. A common approximation uses delayed reactions to represent multi-step processes, but recent research indicates that constant time delays may not accurately capture the dynamics of these systems [4]. Instead, state-dependent time delays that account for the current system state provide more accurate approximations.

For a multi-step reaction process:

$$ B1 \xrightarrow{k1} B2 \xrightarrow{k2} B3 \xrightarrow{k3} \cdots \xrightarrow{kn} Bn \xrightarrow{k_n} P $$

the time delay for the complete process depends on the molecular populations at each step [4]. The Delay Stochastic Simulation Algorithm (DSSA) extends the basic SSA by incorporating time delays, either as fixed values or as state-dependent variables [5]. This approach has been applied to model various biological processes including gene expression, metabolic synthesis, and signaling pathways [4].

Stochastic Modeling of Biochemical Systems with Two-Variable Reduction

For multi-step reaction systems, a two-variable reduction method can significantly simplify model complexity while preserving accuracy [5]. This approach introduces two key variables: the total molecule number (X) and the total "length" (L) of molecules in the multi-step process, where length represents the number of reactions needed for a molecule to reach the final product.

The dynamics are then described by two reactions:

- (X, L) → (X, L-1) for intermediate steps (probability 1-f(X,L,n))

- (X, L) → (X-1, L-1) for the final step (probability f(X,L,n))

where f(X,L,n) is a probability function that depends on the current state and the total number of steps n [5]. This reduction method has been successfully applied to model mRNA degradation processes and provides a promising approach for reducing complexity in biological systems with multi-step reactions.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Stochastic Modeling Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| StochKit Software Toolkit | Discrete stochastic and multiscale simulation of chemically reacting systems | Implementation of various SSA formulations, tau-leaping methods [24] |

| Dizzy Package | Library containing multiple stochastic simulators | Comparing different algorithms for speed/accuracy tradeoffs [23] |

| BioNetGen | Rule-based modeling of biochemical systems | Well-mixed simulations of signaling networks [28] |

| Partial-Propensity Formulations | Efficient SSA implementations with O(N) computational cost | Large reaction networks with many species [26] |

| VAE-CME Framework | Variational autoencoder for solving CME | High-dimensional CME problems [29] |

Applications in Biochemical Systems Research

Gene Expression and Regulation

Stochastic modeling using the CME and GA has provided fundamental insights into the nature of gene expression variability in single cells. The classic two-state gene model, which alternates between active and inactive states, generates mRNA and protein distributions that can be directly derived from the CME or simulated via the GA [22]. These models have demonstrated how promoter architecture influences expression noise and how stochastic effects can lead to bistable population distributions even in genetically identical cells [27].

Applications in drug development include understanding how therapeutic interventions might alter gene expression distributions in cell populations, which is particularly relevant for treatments targeting heterogeneous cancer cell populations. The DGA has been successfully used to infer kinetic parameters of gene promoters from experimental measurements of mRNA expression levels in E. coli, demonstrating the utility of stochastic approaches for parameter estimation from single-cell data [27].

Enzymatic Kinetics and Metabolic Pathways

The CME approach to enzyme kinetics reveals limitations of traditional deterministic models, particularly for enzymes present in low copy numbers or operating at low substrate concentrations. For the Michaelis-Menten enzyme reaction system:

$$ E + S \underset{k{-1}}{\stackrel{k1}{\rightleftharpoons}} ES \xrightarrow{k_2} E + P $$

the CME describes the probability p(m,n,t) of having m substrate molecules and n enzyme-substrate complexes at time t [22]. Quasi-steady-state approximations of the CME recover the classical Michaelis-Menten equation under appropriate conditions, but also reveal significant deviations when molecular populations are small [22].

For metabolic synthesis pathways involving multi-step reactions, state-dependent delay models provide accurate simplifications that reduce computational complexity while preserving essential dynamics [4]. These approaches are valuable for drug development applications where metabolic pathway modulation is therapeutic strategy, such as in cancer metabolism or antimicrobial treatments.

Biological Oscillators and Switches

The Griffith model of genetic oscillators and genetic switch systems have served as important testbeds for stochastic simulation methods [23]. These systems exhibit noise-driven behaviors that cannot be captured by deterministic models, including stochastic switching between alternative stable states and phase diffusion in biological oscillators. The CME-GA hybrid method has been shown to accurately simulate these systems while significantly reducing computational costs compared to full stochastic simulations [23].

Diagram 2: Relationship Between Theoretical Frameworks and Applications

The Chemical Master Equation and Gillespie Algorithm represent complementary frameworks for understanding and simulating stochastic biochemical systems. The CME provides a complete probabilistic description, while the GA enables practical simulation of these systems. Advanced methodologies including CME-GA hybrid methods, differentiable implementations, and state-dependent delay models continue to expand the applicability of these frameworks to increasingly complex biological problems.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these theoretical frameworks offer powerful tools for investigating variability in cellular responses, designing robust synthetic biological circuits, and predicting population-level heterogeneities in drug responses. As single-cell measurement technologies continue to advance, the importance of stochastic modeling approaches is likely to grow, further solidifying the role of the CME and GA as fundamental components of the quantitative biologist's toolkit.

Advanced Algorithms and Practical Applications in Stochastic Simulation

Stochastic modeling is indispensable for understanding the inherent randomness in biochemical systems, from gene expression to cell signaling. Traditional Stochastic Simulation Algorithms (SSA) operate under a Markovian assumption, where the future state depends only on the present. However, this simplification fails to capture a critical biological reality: many cellular processes, such as transcription, translation, and post-translational modifications, involve significant time delays [3]. These delays are not merely incidental; they can profoundly influence system dynamics, leading to oscillations, bistability, and other emergent phenomena that Markovian models cannot accurately reproduce.

The DelaySSA software suite addresses this gap by implementing extended Gillespie algorithms capable of handling delayed reactions. Available in R, Python, and MATLAB, it provides researchers and drug development professionals with an accessible tool to incorporate non-Markovian dynamics into their models, enabling more realistic simulations of complex biological networks [30] [3]. This application note details the use of DelaySSA through foundational examples and a protocol for investigating a therapeutic intervention in cancer.

DelaySSA Fundamentals: From Theory to Implementation

Core Algorithm and Design

DelaySSA implements the delayed Gillespie algorithm, which extends the standard SSA by managing a future event queue for delayed reactions [30] [3]. The core innovation lies in its handling of two fundamental types of delayed reactions:

- Type 1 (ICD - Initiating Completing Delay): Reactant quantities are consumed immediately when a reaction is initiated. The products are generated only after a specified delay time Ï„.

- Type 2 (ND - Non-Consuming Delay): Both reactant consumption and product generation occur simultaneously after the delay time Ï„ [3].

The system state is defined by species counts and two stoichiometric matrices: S_matrix for immediate changes and S_matrix_delay for changes scheduled after delays [30].

Essential Material and Software Setup

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools for DelaySSA

| Item Name | Type/Function | Implementation Note |

|---|---|---|

Stoichiometric Matrix (S_matrix) |

Mathematical Matrix | Defines net changes in species counts for non-delayed reactions. Rows: species, Columns: reactions [30]. |

Delayed Stoichiometric Matrix (S_matrix_delay) |

Mathematical Matrix | Defines net changes in species counts for delayed reactions, applied after delay Ï„ [30]. |

Reactant Matrix (reactant_matrix) |

Mathematical Matrix | Specifies the number of each reactant species required for each reaction to occur [30]. |

| Propensity Function | Mathematical Function | Calculates the probability of each reaction occurring per unit time, typically using mass-action kinetics [3]. |

| Delay Time (Ï„) | Parameter | Time delay for a reaction; can be a fixed value or drawn from a distribution for realistic modeling [3]. |

| DelaySSA R Package | Software | Primary software environment. Install using: devtools::install_github("Zoey-JIN/DelaySSA") [30]. |

Diagram 1: Core stochastic simulation loop with delay handling in DelaySSA (7 words)

Protocol 1: Simulating a Bursty Gene Expression Model

Background and Biological Significance

Gene expression is inherently bursty, with short periods of intense mRNA production followed by prolonged silence. This transcriptional bursting is a major source of cellular noise and heterogeneity, influencing diverse processes from development to drug resistance. The Bursty model illustrates how delays in degradation can shape the distribution of mRNA molecules, providing insights into the stochastic nature of single-cell data [3].

Computational Methodology

System Definition and Initialization

This protocol models a system where gene G produces mRNA (M) in bursts, with delayed mRNA degradation.