Regularization Techniques to Prevent Overfitting in Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to regularization techniques tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development.

Regularization Techniques to Prevent Overfitting in Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to regularization techniques tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development. It covers the foundational theory of overfitting and the bias-variance tradeoff, explores the application of methods like L1/L2 regularization and dropout in predictive modeling, offers strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing model performance, and presents a comparative analysis of techniques using validation frameworks and case studies from recent literature. The content is designed to equip readers with the practical knowledge needed to build robust, generalizable machine learning models for critical tasks in biomedicine.

Understanding Overfitting: The Critical Challenge in Predictive Modeling for Drug Discovery

Application Notes and Protocols

1. Definition and Core Challenge

Overfitting is a fundamental challenge in machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) where a model learns the training data too well, including its noise and random fluctuations, leading to poor performance on new, unseen data [1] [2]. This occurs when a model becomes overly specialized to its training dataset and fails to generalize, which is the ability to apply learned knowledge to broader, real-world applications [1] [3]. In the context of a thesis on regularization techniques, understanding overfitting is the critical first step, as the primary goal of regularization is to constrain model learning to prevent this memorization of noise and promote the discovery of robust, generalizable patterns [4] [3].

2. Quantitative Evidence and Comparative Data

The impact of overfitting and the efficacy of regularization techniques can be quantitatively measured. The following tables summarize key findings from comparative research.

Table 1: Performance Gap Indicative of Overfitting

| Metric | Training Performance | Validation/Test Performance | Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Exceptionally High (e.g., >95%) | Significantly Lower (e.g., <70%) | Strong evidence of overfitting [1] [2]. |

| Error (Loss) | Consistently Decreases | Plateaus or Increases after a point | The model is memorizing, not generalizing [2]. |

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Regularization Efficacy in Image Classification

| Model Architecture | Key Regularization Technique | Validation Accuracy | Generalization Improvement Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline CNN | Dropout, Data Augmentation, Early Stopping | 68.74% | Serves as a baseline for comparison [5] [4]. |

| ResNet-18 | Dropout, Data Augmentation, Early Stopping | 82.37% | Superior architecture benefits from regularization [5] [4]. |

| Generic Model (Theoretical) | L1/L2 Regularization | -- | Can reduce test error by up to 35% and increase model stability by 20% [2]. |

Table 3: Comparison of Advanced Regularization Methods for High-Dimensional Data

| Method | Penalty Type | Key Property | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| LASSO (L1) [3] [6] | L1 (∣β∣) | Performs variable selection; produces sparse models. | High-dimensional data (p > n); feature selection is a priority. |

| Ridge (L2) [3] | L2 (β²) | Shrinks coefficients but does not set them to zero. | Handling multicollinearity; when all predictors are potentially relevant. |

| SCAD [6] | Non-convex | Reduces bias for large coefficients; possesses oracle property. | When unbiased coefficient estimation is critical for large effects. |

| MCP [6] | Non-convex | Similar to SCAD; provides smooth penalty transition. | Alternative non-convex method for variable selection and unbiased estimation. |

3. Experimental Protocols for Detecting and Mitigating Overfitting

The following protocols outline methodologies for identifying overfitting and implementing key regularization techniques within a research framework.

Protocol 1: Baseline Diagnostics for Overfitting Objective: To establish the presence and degree of overfitting in a preliminary model. Materials: Training dataset, validation dataset (hold-out or via cross-validation), computing environment with ML libraries (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch, scikit-learn). Procedure:

- Data Splitting: Split the full dataset into training, validation, and test sets (e.g., 70%/15%/15%). The test set must be locked and used only for final evaluation [2].

- Model Training: Train a model with sufficient complexity on the training set. Record loss and accuracy metrics epoch-by-epoch.

- Validation Monitoring: Simultaneously, evaluate the model on the validation set after each training epoch (or at regular intervals) to record its performance.

- Learning Curve Analysis: Plot the training and validation loss/accuracy curves against training epochs. A defining characteristic of overfitting is a persistent and widening gap between the two curves, where training loss continues to decrease while validation loss stagnates or increases [1] [2].

- Performance Gap Calculation: Quantify the generalization gap (e.g.,

Training Accuracy - Validation Accuracy). A large gap confirms overfitting.

Protocol 2: Implementing Cross-Validation for Robust Evaluation Objective: To obtain a reliable estimate of model generalization error and mitigate overfitting induced by a single, fortunate data split. Methodology: K-Fold Cross-Validation [1] [6]. Procedure:

- Partitioning: Randomly shuffle the dataset and partition it into k (typically 5 or 10) mutually exclusive subsets (folds) of approximately equal size.

- Iterative Training/Validation: For each iteration i (from 1 to k): a. Use fold i as the validation set. b. Use the remaining k-1 folds as the training set. c. Train the model and evaluate on the validation fold.

- Aggregation: The final performance estimate is the average of the performance scores from the k iterations. This protocol ensures the model is evaluated on diverse data slices, providing a more robust measure of its ability to generalize [1].

Protocol 3: Applying L1 (LASSO) and L2 (Ridge) Regularization

Objective: To prevent overfitting by adding a penalty term to the model's loss function, discouraging overly complex parameter values [3].

Theoretical Basis: The regularized loss function is: Loss = Base_Loss (e.g., MSE) + λ * Penalty(β), where λ is the regularization strength hyperparameter.

Procedure for L1 (LASSO):

- Modify Loss Function: Use the L1 penalty:

Penalty(β) = Σ |β_j|. This encourages sparsity, driving some parameters to exactly zero, effectively performing feature selection [3] [6]. - Hyperparameter Tuning: Use cross-validation (Protocol 2) to select the optimal value for

λ. A higherλincreases regularization strength. - Model Training: Train the model by minimizing the regularized loss function.

- Analysis: Examine the final model coefficients. Many will be zero, indicating the corresponding features were deemed non-essential by the model.

Procedure for L2 (Ridge):

- Modify Loss Function: Use the L2 penalty:

Penalty(β) = Σ β_j². This shrinks all coefficients proportionally but does not set them to zero, helping manage multicollinearity [3]. - Hyperparameter Tuning: Similarly, tune

λvia cross-validation. - Model Training: Train the model to minimize the regularized loss.

Protocol 4: Implementing Dropout in Neural Networks Objective: To reduce co-adaptation of neurons and create an implicit ensemble of subnetworks, thereby improving generalization [5] [4]. Materials: A neural network architecture (e.g., CNN, ResNet). Procedure:

- Layer Modification: During training, for a specified dropout rate p (e.g., 0.5), randomly "drop" (set to zero) the outputs of each neuron in the designated layer(s) for each training sample.

- Training: Only the non-dropped neurons are updated via backpropagation for that iteration. This process is repeated stochastically every iteration.

- Inference/Testing: During evaluation, dropout is turned off, and all neuron outputs are used, typically scaled by (1-p) to maintain expected output magnitudes.

4. The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools and "Reagents" for Overfitting Research

| Item/Module | Function in Experiment | Example (from Protocols) |

|---|---|---|

| Training/Validation/Test Sets | The foundational substrate. Training set teaches the model, validation set tunes hyperparameters and diagnoses overfitting, test set provides final, unbiased evaluation [2]. | Created via train_test_split in scikit-learn [3]. |

| K-Fold Cross-Validator | A tool for robust performance estimation and hyperparameter tuning, mitigating variance from data splitting [6]. | KFold or GridSearchCV in scikit-learn. |

| Regularization Hyperparameter (λ/α) | The "dose" of regularization. Controls the trade-off between fitting the data and model simplicity [3] [6]. | Tuned via cross-validation in Lasso (alpha) [3]. |

| Dropout Layer | A structural "inhibitor" for neural networks that stochastically deactivates neurons during training to prevent co-adaptation [5] [4]. | torch.nn.Dropout in PyTorch; tf.keras.layers.Dropout in TensorFlow. |

| Early Stopping Callback | A monitoring agent that halts training when validation performance degrades, preventing the model from learning noise in later epochs [1] [4]. | EarlyStopping callback in Keras/TensorFlow. |

| Data Augmentation Pipeline | A method to synthetically expand and diversify the training data, exposing the model to more variations and reducing memorization of specific samples [2] [4]. | Includes operations like rotation, flipping, cropping (e.g., torchvision.transforms). |

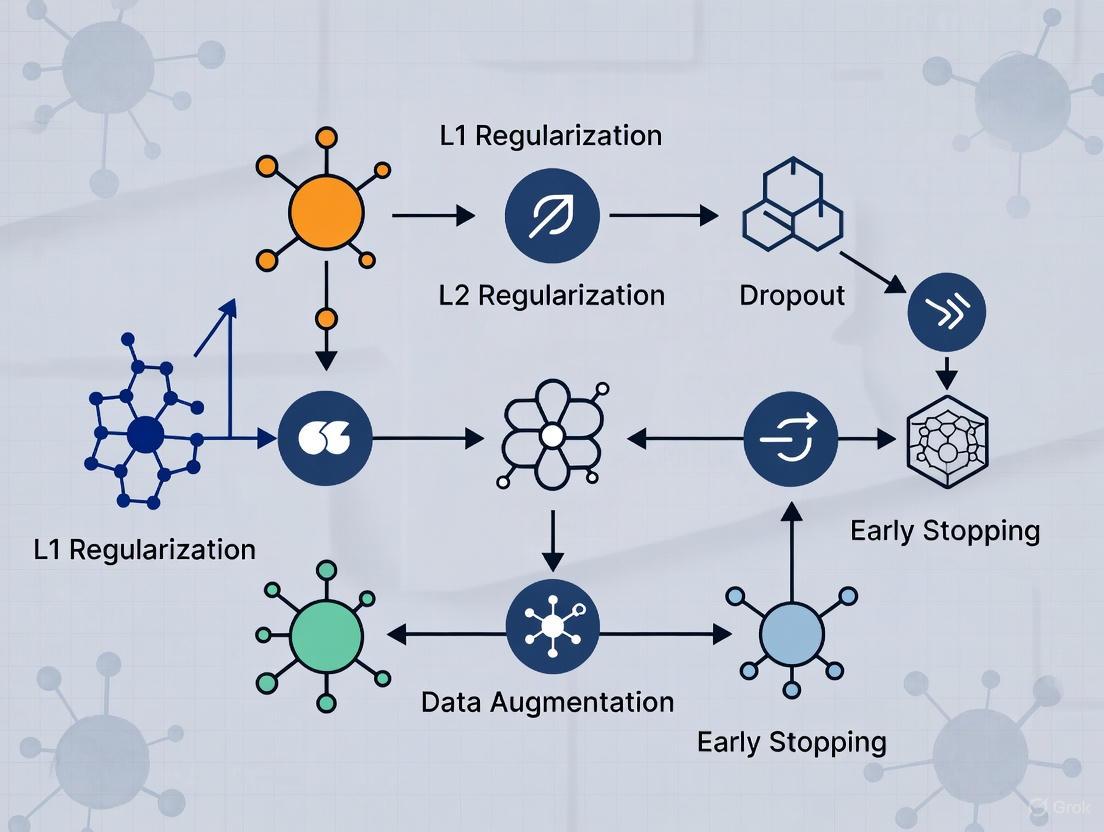

5. Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: The Generalization vs. Overfitting Paradigm (88 chars)

Diagram 2: Iterative Research Workflow with Regularization (99 chars)

Diagram 3: K-Fold Cross-Validation Procedure (k=5) (73 chars)

Overfitting represents a fundamental challenge in the application of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) to clinical research and drug development. An overfit model performs well on its training data but fails to generalize to new, unseen datasets, a critical flaw when patient safety and billion-dollar development decisions are at stake. In high-stakes clinical environments, this statistical error translates directly to financial losses, patient risks, and failed clinical trials [7]. Regularization techniques, which prevent overfitting by penalizing model complexity, have therefore become essential for developing robust, generalizable, and trustworthy AI applications in healthcare [7]. This Application Note examines the tangible consequences of overfitting and provides structured protocols for implementing regularization to safeguard drug safety and clinical trial integrity.

Quantifying the Impact: Overfitting in Clinical and Safety Contexts

The table below summarizes empirical findings on AI/ML performance and failure rates in clinical and safety applications, highlighting domains where overfitting poses significant risks.

Table 1: Performance and Risk Indicators in Clinical AI Applications

| Application Domain | Reported Performance (AUC/F-score) | Key Risks & Failure Contexts | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Event (ADE) Prediction | AUC up to 0.96 [8] | High false positive rates with early algorithms (e.g., BCPNN); challenges with rare events and drug interactions [9] | FAERS, EHRs, Spontaneous Reports [9] [8] |

| Toxicity Prediction (e.g., DILI) | High-performance models in research (specific metrics not consolidated) [8] | Failure to generalize across diverse patient populations and drug classes; high cost of late-stage attrition [10] [8] | Preclinical data, Molecular structures [8] |

| Trial Operational Risk | AI models used for prediction (specific metrics not consolidated) [8] | Inaccurate prediction of patient recruitment or phase transition success, leading to costly protocol amendments and delays [11] [8] | Trial protocols, Historical trial data [8] |

| Drug-Gene Interaction | AUC 0.947, F1-score 0.969 [12] | Poor generalizability to new drug candidates or diverse patient omics-profiles invalidates discovery efforts [12] | Transcriptomic data (e.g., NCBI GEO) [12] |

The financial implications of these failures are substantial. Late-stage clinical trial failures are a primary driver of development costs, with 40-50% of Phase III trials failing despite representing the most expensive stage, costing between $31 million and over $214 million per trial [10]. These costs are ultimately passed on, contributing to higher drug prices. Furthermore, in pharmacovigilance, models prone to overfitting may generate excessive false positive signals, overwhelming safety review teams and potentially causing either harmful delays in signal detection or costly misdirection of resources [9].

Regularization Techniques: Core Protocols for Robust Models

Regularization techniques are essential for developing models that generalize well to real-world clinical data. The following protocols detail key methodologies.

Protocol: Standard Regularization Techniques for Predictive Model Development

This protocol outlines the application of L1 (Lasso), L2 (Ridge), and Elastic Net regularization to prevent overfitting in clinical predictive models [7].

- 3.1.1 Application Scope: Suitable for supervised learning tasks, including classification (e.g., serious adverse event prediction) and regression (e.g., predicting continuous biomarker levels).

- 3.1.2 Materials and Reagents:

- Software: Python with scikit-learn, TensorFlow, or PyTorch.

- Computing Environment: Standard workstation or high-performance computing cluster for large datasets.

- 3.1.3 Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Split data into training, validation, and test sets. Perform feature scaling (e.g., standardization) to ensure regularization penalties are applied uniformly.

- Model Definition: Integrate the regularization term into the model's loss function.

- For L1 Regularization, add the sum of the absolute values of the model coefficients:

Loss = Original_Loss + λ * Σ|coefficient|. - For L2 Regularization, add the sum of the squared values of the model coefficients:

Loss = Original_Loss + λ * Σ(coefficient^2). - For Elastic Net, combine L1 and L2:

Loss = Original_Loss + λ1 * Σ|coefficient| + λ2 * Σ(coefficient^2).

- For L1 Regularization, add the sum of the absolute values of the model coefficients:

- Hyperparameter Tuning (λ): Use cross-validation on the training set to find the optimal regularization strength (λ). This parameter controls the trade-off between fitting the training data and model simplicity.

- Model Training: Train the model on the training set using the tuned hyperparameters.

- Model Validation: Evaluate the final model's performance on the held-out test set to estimate real-world performance.

- 3.1.4 Interpretation Guidelines:

- L1 (Lasso) is highly effective for feature selection, as it can drive coefficients of non-informative features to zero [7].

- L2 (Ridge) tends to shrink coefficients uniformly but does not zero them out, making it suitable when most features are relevant.

- Elastic Net is advantageous when dealing with highly correlated features, a common scenario in genomics and transcriptomics data [12].

Protocol: Advanced Regularization in Deep Learning for Drug Discovery

This protocol addresses overfitting in complex deep learning models used in discovery, such as those predicting drug-gene interactions [12].

- 3.2.1 Application Scope: Deep neural networks (DNNs) for high-dimensional data analysis (e.g., multi-omics data, chemical structures).

- 3.2.2 Materials and Reagents:

- Software: TensorFlow/Keras or PyTorch.

- Data: Large-scale biological datasets (e.g., transcriptomics from NCBI GEO, chemical libraries).

- 3.2.3 Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Model Architecture Design: Implement a feedforward neural network. For a study predicting drug-gene interactions on tight junction integrity, a network with three hidden layers of 64 nodes each was effective [12].

- Integrate Dropout Regularization: During training, randomly "drop out" (i.e., temporarily remove) a proportion (e.g., 30%) of the nodes in each layer in each training batch. This prevents complex co-adaptations of neurons on training data [12].

- Early Stopping: Monitor the model's performance on a validation set during training. Halt training when validation performance stops improving, preventing the model from over-optimizing to the training data.

- Explainability Analysis: Apply Explainable AI (XAI) methods like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) post-training to validate that the model's predictions are based on biologically plausible features [12].

Diagram: Workflow for Developing a Regularized Deep Learning Model in Drug Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues key computational and data resources essential for implementing robust, regularized models in clinical and discovery research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Regularized Model Development

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn Library | Provides implementations of L1, L2, and Elastic Net regularization for traditional ML models. | sklearn.linear_model.LogisticRegression(penalty='l1', C=1.0) |

| TensorFlow / PyTorch | Deep learning frameworks that support Dropout, L2 weight decay, and other advanced regularization. | tf.keras.layers.Dropout(0.3) for 30% dropout [12]. |

| SHAP / LIME Libraries | Explainable AI (XAI) tools for interpreting complex models and validating feature importance. | Post-hoc analysis of a DNN to ensure predicted drug-gene interactions are biologically plausible [12]. |

| Stratified Train/Val/Test Splits | Ensures representative distribution of classes across data splits, critical for unbiased evaluation. | Splitting clinical trial data to maintain similar proportions of responders/non-responders in all sets. |

| Cross-Validation Pipelines | Robust method for hyperparameter tuning (e.g., finding optimal λ) without leaking test data information. | Using 5-fold cross-validation to tune the regularization strength of a Ridge regression model. |

A Framework for Safe Implementation: From Validation to Deployment

To ensure AI/ML tools are safely integrated into clinical and development workflows, a phased, "clinical trials-informed" framework is recommended [13]. This approach systematically assesses safety and efficacy before full deployment.

Diagram: Phased Framework for AI Implementation in Healthcare

- Phase 1: Safety (Silent Mode & Bias Testing): The model is executed retrospectively or in "silent mode" where its predictions are logged but do not influence clinical decisions. This phase includes rigorous bias and fairness analyses across patient demographics to ensure the model does not perpetuate or amplify health disparities [13].

- Phase 2: Efficacy (Background Execution): The model processes real-time data in a live clinical environment, but its outputs remain hidden from end-users. This allows researchers to evaluate performance under real-world conditions and refine data pipelines and workflows without patient risk [13].

- Phase 3: Effectiveness (Pragmatic Comparison): The tool is deployed to a limited set of users to evaluate its effectiveness compared to the current standard of care. The focus shifts from pure accuracy to impact on real-world health outcomes and clinician workflows [13].

- Phase 4: Monitoring (Post-Deployment Surveillance): Following scaled deployment, the model undergoes continuous surveillance to detect model drift (deterioration in performance due to changes in underlying data) and to gather user feedback for iterative improvement [13].

Overfitting is not merely a statistical nuance but a critical vulnerability that can compromise patient safety, derail clinical trials, and inflate drug development costs. The disciplined application of regularization techniques—from foundational L1/L2 methods to advanced strategies like dropout in deep learning—is paramount for building reliable AI models. By integrating these techniques within a structured implementation framework that emphasizes phased testing and continuous monitoring, researchers and drug developers can mitigate these risks. This rigorous approach ensures that AI and ML tools fulfill their promise of accelerating drug discovery and improving patient outcomes without introducing new perils.

In the pursuit of developing robust predictive models, the bias-variance tradeoff represents a fundamental concept that governs a model's ability to generalize to unseen data. This framework is particularly crucial in scientific domains such as drug development, where model performance directly impacts research validity and decision-making processes. The tradeoff emerges from the tension between two error sources: bias, resulting from overly simplistic model assumptions, and variance, arising from excessive sensitivity to training data fluctuations [14] [15].

When models exhibit high bias, they underfit the data, failing to capture underlying patterns and demonstrating poor performance on both training and validation sets. Conversely, models with high variance overfit the data, learning noise as if it were signal and consequently performing well on training data but poorly on unseen data [16]. Understanding this balance is essential for researchers implementing regularization techniques to prevent overfitting while maintaining model capacity to detect genuine biological signals.

This article establishes the theoretical foundation of the bias-variance decomposition, provides experimental protocols for its evaluation, and presents visualization frameworks to guide researchers in optimizing model performance for scientific applications.

Theoretical Foundation

Mathematical Decomposition

The bias-variance tradeoff can be mathematically formalized through the decomposition of the expected prediction error. For a given test point ( x0 ) with observed value ( y0 = f(x0) + \epsilon ) (where ( \epsilon ) represents irreducible error with mean zero and variance ( \sigma^2 )), the expected prediction error of a model ( \hat{f}(x0) ) can be expressed as:

[ \text{Error}(x0) = \text{Bias}^2[\hat{f}(x0)] + \text{Var}[\hat{f}(x_0)] + \sigma^2 ]

Where:

- Bias = ( \mathbb{E}[\hat{f}(x0)] - f(x0) ) → Error from simplistic assumptions

- Variance = ( \mathbb{E}[(\hat{f}(x0) - \mathbb{E}[\hat{f}(x0)])^2] ) → Error from sensitivity to data fluctuations

- ( \sigma^2 ) → Irreducible error inherent in the data generation process [15]

This decomposition reveals that to minimize total prediction error, researchers must balance the reduction of both bias and variance, as decreasing one typically increases the other.

Conceptual Framework in Model Selection

The behavior of bias and variance across model complexity follows a predictable pattern that guides model selection strategies:

As model complexity increases, bias decreases as the model becomes more flexible in capturing underlying patterns. However, variance simultaneously increases as the model becomes more sensitive to specific training data instances. The optimal model complexity occurs at the point where total error is minimized, balancing these competing objectives [15] [16].

Quantitative Analysis

Error Comparison Across Model Types

The following table summarizes the characteristic performance patterns across the bias-variance spectrum, providing researchers with diagnostic indicators for model assessment:

Table 1: Model Performance Characteristics Across the Bias-Variance Spectrum

| Model Characteristic | High Bias (Underfitting) | High Variance (Overfitting) | Balanced (Ideal) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Error | High | Very Low | Low |

| Testing Error | High | High | Low |

| Model Complexity | Too Simple | Too Complex | Appropriate |

| Primary Symptom | Fails to capture data patterns | Memorizes training data noise | Captures patterns without noise |

| Typical Accuracy Pattern | Training: ~65%, Test: ~60% [17] | Training: ~97%, Test: ~75% [17] | Training & Test: Similarly High |

| Data Utilization | Insufficient pattern learning | Excessive noise learning | Optimal pattern extraction |

Polynomial Regression Case Study

Polynomial regression provides a clear experimental demonstration of the bias-variance tradeoff, where model complexity is controlled through the polynomial degree. The following quantitative results illustrate this relationship:

Table 2: Error Analysis Across Polynomial Degrees in Regression Modeling

| Polynomial Degree | Training MSE | Testing MSE | Primary Error Source | Model Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree 1 | 0.2929 [15] | High | Bias | Underfitting |

| Degree 4 | 0.0714 [15] | Lower | Balanced | Optimal Range |

| Degree 18 | ~0.01 [18] | ~0.014 [18] | Balanced | Near Optimal |

| Degree 25 | ~0.059 [15] | Higher | Variance | Overfitting |

| Degree 40 | ~0.01 [18] | 315 [18] | Variance | Severe Overfitting |

The extreme performance degradation at degree 40 (testing MSE of 315 compared to training MSE of 0.01) exemplifies the critical risk of overfitting in complex models and underscores the importance of rigorous validation [18].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Bias-Variance Decomposition Analysis

Objective: Quantitatively decompose model error into bias and variance components to diagnose performance limitations.

Materials:

- Dataset with ground truth labels

- Computational environment (Python/R)

- Model family with tunable complexity (e.g., polynomial regression, decision trees)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Generate or select a dataset with known underlying function (e.g., sinusoidal pattern)

- Add controlled Gaussian noise (μ=0, σ=0.1) to simulate real-world variability [18]

- Split data into training, validation, and testing sets (typical ratio: 60/20/20)

Model Training:

- Train multiple models across complexity spectrum (e.g., polynomial degrees 1-40)

- For each complexity level, train multiple instances on different data samples using bootstrapping

Error Calculation:

- Calculate predictions for each model on fixed test points

- Compute bias² as squared difference between average prediction and true value

- Compute variance as average squared difference between individual predictions and average prediction

- Sum components to obtain total error

Analysis:

- Identify complexity level where total error is minimized

- Determine whether bias or variance dominates at current model configuration

- Select optimal model complexity for deployment

Expected Outcomes: A U-shaped error curve demonstrating the tradeoff, with clear identification of the optimal operating point for the given dataset.

Protocol 2: Regularization Optimization Framework

Objective: Identify optimal regularization parameters to control overfitting while maintaining model capacity.

Materials:

- High-dimensional dataset (common in omics studies)

- Regularized model algorithm (Lasso, Ridge, Elastic Net)

- Cross-validation framework

Procedure:

- Experimental Setup:

- Standardize features to zero mean and unit variance to ensure penalty uniformity

- Define regularization parameter grid (λ range from 10^-5 to 10^5 in logarithmic steps)

Model Selection:

- Implement k-fold cross-validation (k=5 or 10) for each λ value

- For L1/L2 regularization, monitor coefficient paths as λ increases

- For Elastic Net, optimize both λ and α mixing parameters

Convergence Detection:

- Monitor learning curves (training/validation error vs. sample size)

- Identify convergence point where additional data provides diminishing returns [19]

- Establish minimum sufficient dataset size for future experiments

Validation:

- Evaluate selected model on held-out test set

- Compare performance metrics with unregularized baseline

- Assess feature selection stability (for L1 regularization)

Expected Outcomes: A regularized model with improved generalization performance, optimal feature subset, and quantitative assessment of bias-variance balance.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for Bias-Variance Optimization

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| k-Fold Cross-Validation | Robust error estimation | Model selection & hyperparameter tuning across all research domains |

| L2 (Ridge) Regularization | Prevents coefficient inflation | Continuous outcomes, multicollinear predictors (transcriptomic data) |

| L1 (Lasso) Regularization | Automatic feature selection | High-dimensional data with sparse signal (genomic marker identification) |

| Elastic Net | Hybrid feature selection & regularization | When predictors are highly correlated and sparse solutions desired |

| Learning Curves | Diagnostic for data adequacy | Determining whether more data will improve performance |

| Bootstrap Aggregation (Bagging) | Variance reduction through averaging | Unstable estimators (decision trees) in compound activity prediction |

| Boosting Methods | Sequential bias reduction | Improving weak predictors for accurate ensemble models |

Visualization Framework

Model Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines a systematic approach for model optimization within the bias-variance framework, particularly relevant for drug development applications:

Implementation Considerations for Scientific Research

When applying these principles in drug development and scientific research, several domain-specific considerations enhance practical utility:

- Data Heterogeneity: Biological datasets often exhibit substantial heterogeneity; stratified sampling during cross-validation ensures representative error estimation

- Feature Interpretation: In addition to predictive performance, prioritize model interpretability for biological insight generation

- Multi-scale Validation: Implement validation at molecular, cellular, and organismal levels where applicable to ensure robust generalizability

- Regulatory Compliance: Document all model selection decisions and parameter choices for regulatory submission requirements

The bias-variance tradeoff provides a principled framework for developing models that generalize effectively beyond their training data—a critical consideration in scientific research and drug development. Through systematic application of the experimental protocols and visualization tools presented, researchers can quantitatively diagnose model deficiencies, implement appropriate regularization strategies, and optimize the balance between underfitting and overfitting. This approach ensures that predictive models capture genuine biological signals rather than experimental noise, ultimately enhancing the reliability and translational impact of computational approaches in pharmaceutical research.

Within the framework of a thesis investigating regularization techniques to prevent overfitting in biomedical research, it is critical to first understand the fundamental data-driven challenges that necessitate such interventions. Overfitting is a pervasive modeling error where a machine learning algorithm captures noise or random fluctuations in the training data rather than the underlying pattern, leading to excellent performance on training data but poor generalization to unseen data [20]. In biomedical applications—spanning clinical proteomics, immunology, medical imaging, and precision oncology—the consequences of overfitting are particularly severe, as they can lead to erroneous biomarker discovery, inaccurate diagnostic tools, and unreliable clinical decision support systems [21] [22] [23].

This application note details the three most common and interconnected catalysts for overfitting in biomedical data analysis: small sample sizes, high-dimensional omics data, and redundant features. We will dissect each cause, present quantitative evidence of their impact, provide detailed experimental protocols for mitigation grounded in regularization principles, and outline essential tools for the research practitioner.

Core Causes of Overfitting: Analysis and Quantitative Evidence

Small Sample Sizes

The high cost, ethical constraints, and technical difficulty of collecting and labeling biomedical data often result in limited training samples [24]. This data scarcity is a primary driver of overfitting, as models with sufficient complexity can easily memorize the small dataset, including its noise, rather than learning generalizable patterns [25]. In clinical proteomics and intensive care unit (ICU) studies, datasets frequently comprise fewer than 1,000 patients, which tends to overestimate performance without rigorous external validation [21] [23].

Quantitative Impact: A study on physiological time series classification demonstrated that deep learning models trained on limited samples suffer from severe overfitting and reduced generalization ability. The proposed WEFormer model, which incorporates regularization via a frozen pre-trained time-series foundation model and wavelet decomposition, achieved significant performance gains precisely because it was designed for small sample size scenarios [24].

Table 1: Impact of Small Sample Sizes on Model Performance

| Dataset/Context | Typical Sample Size | Reported Consequence | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICU Risk Prediction [23] | Often < 1,000 patients | Overestimation of performance, poor external generalization | External validation, data augmentation |

| Physiological Time Series [24] | Limited, costly to obtain | Severe overfitting in deep learning models | Use of frozen foundation models (transfer learning), wavelet decomposition |

| Clinical Proteomics [21] | Small cohorts relative to feature number | Limited real-world impact, poor generalization | Emphasis on rigorous study design, simplicity, and validation |

High-Dimensional Omics Data

The advent of high-throughput technologies generates datasets where the number of features (e.g., genes, proteins, metabolites) p vastly exceeds the number of samples n. This "curse of dimensionality" creates a vast model space where finding a truly predictive signal is extremely difficult, and the risk of fitting to spurious correlations is high [26]. In precision oncology, integrating multi-omics data (genome, transcriptome, proteome) is essential but compounds this dimensionality problem [27].

Quantitative Impact: Research on feature selection in healthcare datasets shows that high dimensionality presents major challenges for analysis and interpretation. An ensemble feature selection strategy achieved over a 50% reduction in feature subset size while maintaining or improving classification metrics like the F1 score by up to 10% [28]. This direct link between dimensionality reduction and performance maintenance underscores the overfitting risk inherent in high-dimensional data.

Redundant and Noisy Features

Biomedical datasets frequently contain irrelevant, redundant, or highly correlated features (e.g., technical noise from different scanner types, batch effects, or biologically correlated analytes) [25]. These features add no informative value for the prediction task but increase model complexity, allowing the algorithm to fit to irrelevant noise. For instance, a tumor detection model trained on MRI scans from one manufacturer may overfit to scanner-specific artifacts and fail on data from another manufacturer [25].

Quantitative Impact: The double-edged nature of model complexity is clear: adding more features reduces training error but can increase model variance, leading to higher test error [22]. Regularization techniques like Lasso (l1), which penalize the absolute values of coefficients, can drive coefficients of irrelevant features to zero, effectively performing feature selection and combating this cause of overfitting [22].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Causes and Regularization-Based Solutions

| Cause of Overfitting | Primary Effect | Exemplary Regularization/Prevention Technique | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Sample Size | High variance, model memorization | Early Stopping [22] [25]; Use of Pre-trained/Frozen Foundation Models [24] | Halts training before noise fitting; leverages external knowledge to reduce trainable parameters. |

| High Dimensionality | Vast model space, spurious correlations | Dimensionality Reduction (PCA, Feature Selection) [22]; l1/Lasso Regularization [22] |

Reduces feature space; enforces sparsity in model coefficients. |

| Redundant/Noisy Features | Increased complexity, fitting to artifacts | Ensemble Feature Selection [28]; l2/Ridge Regularization [22] |

Identifies clinically relevant features; shrinks coefficients of correlated features. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Ensemble Feature Selection for High-Dimensional Healthcare Data

Based on the method from [28]

Objective: To reduce dimensionality and mitigate overfitting by identifying a robust, clinically relevant feature subset from multi-modal biomedical data.

Materials:

- High-dimensional dataset (e.g., BioVRSea, SinPain [28]).

- Python/R environment with scikit-learn.

- Tree-based models (Random Forest, XGBoost) for initial ranking.

- Greedy backward elimination algorithm.

Procedure:

- Feature Ranking: Train a tree-based model (e.g., Random Forest) on the entire training set. Rank all features based on their calculated importance scores (e.g., Gini importance).

- Greedy Backward Elimination: Starting with the full feature set, iteratively remove the least important feature (from the current model) and re-evaluate model performance on a held-out validation set. Use a performance metric (e.g., F1 score) as the criterion.

- Subset Generation: Record the performance curve throughout the elimination process. Generate several candidate feature subsets (e.g., the set at the performance peak, sets within one standard error of the peak).

- Ensemble Merging: Combine the candidate subsets using a union or intersection strategy. The study [28] used a specific merging strategy to produce a single, robust set of features.

- Validation: Train and evaluate a final model (e.g., Support Vector Machine, Random Forest) using only the selected feature subset on an independent test set. Compare accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score to the model trained on all features.

Diagram: Workflow for Ensemble Feature Selection

Protocol 2: Training a Regularized Model for Small-Sample Physiological Time Series

Based on the WEFormer model from [24]

Objective: To classify physiological time series (e.g., EEG, ECG) using a deep learning model regularized to prevent overfitting on small datasets.

Materials:

- Small-sample physiological dataset (e.g., WESAD, MOCAS [24]).

- Pre-trained Time Series Foundation Model (TSFM), e.g., MOMENT [24], with weights frozen.

- PyTorch/TensorFlow environment.

- Differentiable Wavelet Transform (MODWT) layer.

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Load raw, multimodal physiological time series signals. Minimal preprocessing is recommended to avoid data leakage.

- Dual-Path Input Processing:

- Path A (Raw Signal): Pass the raw input signal through a learnable wavelet decomposition layer (MODWT). This decomposes the signal into frequency sub-bands.

- Path B (Foundation Features): Pass the same raw input signal through the frozen pre-trained TSFM to extract generalized, high-level features.

- Learnable Attention: Apply a cross-modal attention mechanism (e.g., as in Husformer [24]) to the wavelet sub-bands. This mechanism adaptively learns to highlight frequency bands critical for the task and suppress noisy bands.

- Feature Fusion and Classification: Fuse the attended wavelet features (Path A) with the frozen TSFM embeddings (Path B). Pass the fused representation through a final classifier head (e.g., a fully connected layer).

- Training with Caution: Train only the parameters of the wavelet layer, attention mechanism, and classifier head. Do not fine-tune the frozen TSFM. Use early stopping by monitoring validation loss to halt training before overfitting occurs.

Diagram: WEFormer Architecture for Small Samples

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Materials for Combating Overfitting

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in Preventing Overfitting | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Foundation Models | Software/Model | Provides strong, generalizable feature priors; reduces trainable parameters for small-sample tasks, acting as a form of implicit regularization. | MOMENT (Time Series) [24], Frozen encoders in Flexynesis [27]. |

| Ensemble Feature Selection Algorithms | Algorithm | Reduces model complexity and variance by systematically identifying and removing redundant/irrelevant features. | Waterfall Selection (Tree Rank + Greedy Elim.) [28], TMGWO, ISSA [26]. |

| Regularization-Enabled Software Frameworks | Software Framework | Simplifies the implementation of l1/l2 penalties, dropout, and early stopping within standard model training workflows. |

Scikit-learn, PyTorch, TensorFlow, Flexynesis [27]. |

| Curated Benchmark Datasets | Data | Enables robust external validation, which is critical for detecting overfitting and assessing true generalizability. | WESAD [24], BioVRSea & SinPain [28], TCGA/CCLE [27]. |

| Hybrid Feature Selectors (TMGWO, BBPSO) | Optimization Algorithm | Intelligently searches high-dimensional feature spaces for optimal, small subsets that maximize model accuracy and generalization. | Two-phase Mutation Grey Wolf Optimizer (TMGWO) [26]. |

| Data Augmentation Pipelines | Data Processing Technique | Artificially increases effective sample size and diversity, diluting the influence of noise and reducing memorization. | Synthetic data generation, signal warping/adding noise for time series [24]. |

| Cross-Validation Schedulers | Evaluation Protocol | Provides a more reliable estimate of model performance on unseen data than a single train-test split, guiding hyperparameter tuning without causing data leakage. | k-Fold, Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) [26] [25]. |

Application Notes & Protocols

Context within a Thesis on Regularization Techniques: This document serves as a methodological companion to a broader research thesis investigating advanced regularization techniques for mitigating overfitting in predictive models, with a particular focus on applications in computational drug discovery. The reliable detection of overfitting is the critical first step that informs the selection and tuning of subsequent regularization strategies [25] [29].

The primary quantitative evidence for overfitting manifests in the disparity between performance metrics calculated on training versus held-out validation data. The following table synthesizes key metrics and their interpreted meaning from experimental model training [25] [30] [31].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Indicators for Overfitting Detection

| Metric | Typical Calculation | Indicator of Overfitting | Interpretation & Threshold Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training-Validation Accuracy Gap | Training_Accuracy - Validation_Accuracy |

A large, persistent gap (e.g., >10-15%) is a strong signal [25] [32]. | Suggests the model memorizes training-specific patterns. The acceptable threshold is domain-dependent but should be minimal. |

| Training-Validation Loss Gap | Validation_Loss - Training_Loss |

Validation loss significantly exceeds training loss. A rising validation loss concurrent with falling training loss is a definitive signature [25] [31]. | The model's errors on new data increase as it fits training noise. The divergence point pinpoints the onset of overfitting. |

| Cross-Validation Performance Variance | Standard deviation of accuracy/loss across k folds. | High variance across folds indicates model performance is unstable and highly dependent on the specific training subset [30] [33]. | Models that generalize poorly will show inconsistent results when validated on different data slices. |

| Learning Curve Divergence | Tracking loss/accuracy vs. epochs or data size. | The validation metric curve plateaus or worsens while the training metric continues to improve [30] [31]. | Visual confirmation that additional training (or complexity) only improves performance on the training set. |

Core Experimental Protocols for Detection

The following protocols detail standardized methodologies for detecting overfitting using the key indicators listed above. These protocols are foundational for empirical validation within regularization research.

Protocol 1: Monitoring Loss Curves for Early Stopping Criterion

Objective: To identify the optimal training epoch where further iteration leads to overfitting, characterized by a rising validation loss. Materials: Model, training dataset (Dtrain), validation dataset (Dval), loss function (L), optimizer. Procedure:

- Initialization: Split the full dataset into Dtrain (e.g., 80%) and Dval (20%). Ensure no data leakage [30].

- Epoch Loop: For each training epoch (e): a. Train the model on Dtrain for one full pass. b. Compute the training loss (Ltrain(e)) as the average loss over all batches in Dtrain [31]. c. Evaluate the model on the untouched Dval to compute validation loss (Lval(e)). d. Record Ltrain(e) and L_val(e).

- Analysis & Stopping Point: a. Plot Ltrain and Lval against epoch count. b. Identify epoch (e) where L_val is at its minimum and begins to increase subsequently, while L_train continues to decrease. c. The point (e) is the early stopping trigger. Training beyond e* constitutes overfitting [29] [32]. Expected Outcome: A plot demonstrating the characteristic divergence, providing empirical justification for applying early stopping as a regularization technique.

Protocol 2: K-Fold Cross-Validation for Robust Generalization Assessment

Objective: To obtain a robust estimate of model generalization error and detect overfitting by testing on multiple, distinct validation folds. Materials: Full dataset (D), model architecture, k parameter (typically 5 or 10). Procedure:

- Partitioning: Randomly shuffle D and partition it into k mutually exclusive subsets (folds) of approximately equal size.

- Iterative Training & Validation: For i = 1 to k: a. Designate fold i as the validation set (Dvali). b. Use the remaining k-1 folds as the training set (Dtraini). c. Train a new model instance from scratch on Dtraini. d. Evaluate the model on Dvali, recording primary metrics (e.g., accuracy, loss).

- Aggregate Analysis: a. Calculate the mean and standard deviation of the validation metric across all k folds. b. Compare to Training Performance: For each fold i, also note the final performance on Dtraini. A consistent pattern where mean(Dtrainmetrics) >> mean(Dvalmetrics) confirms overfitting [25] [34]. c. High standard deviation in D_val metrics further indicates model instability and sensitivity to data sampling—a hallmark of high variance/overfitting [33]. Expected Outcome: A k-fold CV report table showing performance per fold. Overfitting is indicated by high average training performance coupled with lower average validation performance and/or high validation metric variance.

Visualization of Detection Logic & Workflows

Diagram 1: Early Stopping Workflow Logic (93 chars)

Diagram 2: Bias-Variance Tradeoff & Overfitting (99 chars)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential computational tools and conceptual "reagents" for conducting overfitting detection experiments, analogous to a wet-lab protocol.

Table 2: Essential Toolkit for Overfitting Detection Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Detection Protocol | Example/Implementation Note |

|---|---|---|

| Validation Set | Provides unbiased evaluation data to compute validation loss/accuracy, the primary indicator for overfitting [25] [32]. | Typically 15-20% of labeled data, held out from training. Must be representative and free from leakage. |

| K-Fold Cross-Validation Scheduler | Automates the partitioning and iterative training-validation process for robust generalization error estimation [30] [34]. | sklearn.model_selection.KFold or custom training loops. |

| Loss Function & Metric Trackers | Quantifies the error (loss) and performance (accuracy, etc.) on training and validation sets across epochs [31]. | Cross-entropy (classification), MSE (regression). Track with TensorBoard, MLflow, or custom loggers. |

| Learning Curve Plotter | Visualizes the divergence between training and validation metrics, offering intuitive detection of overfitting onset [30] [31]. | Matplotlib, Seaborn scripts to plot loss/accuracy vs. epochs. |

| Regularization Probes (L1/L2, Dropout) | Used in controlled experiments to test if performance gap shrinks. Applying regularization and observing a reduced gap confirms initial overfitting [29] [35]. | L1/L2 penalty in optimizers, Dropout layers in neural networks. Compare validation performance with/without. |

| Data Augmentation Module | Generates modified training samples. If performance improves on validation set, it suggests the model was previously overfitting to limited data variations [25] [34]. | Image transforms (flips, rotations), noise injection, SMILES enumeration for molecular data. |

A Practical Guide to Regularization Methods for Robust Drug Discovery Models

L1 (Lasso) Regularization for Feature Selection in High-Dimensional Biomarker Data

In the field of biomedical research, the advent of high-throughput technologies has enabled the collection of vast amounts of molecular data, creating landscapes of high-dimensional biomarker information. In such contexts, where the number of features (p) often far exceeds the number of observations (n), traditional statistical models face significant challenges, including severe overfitting. Overfitting occurs when a model learns not only the underlying patterns in the training data but also the noise and random fluctuations, resulting in poor generalization to new, unseen data [36]. This problem is particularly pronounced in high-dimensional spaces where data points become sparse and models can easily identify false relationships between variables [36]. Regularization techniques represent a powerful solution to this problem by introducing constraints or penalties to the model to prevent overfitting and improve generalization [37].

Among regularization methods, L1 regularization, commonly known as LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator), has emerged as a particularly valuable tool for high-dimensional biomarker data. Unlike its counterpart L2 regularization (Ridge), which only shrinks coefficients toward zero, L1 regularization has the unique property of performing feature selection by driving some coefficients to exactly zero [37]. This characteristic is exceptionally beneficial in biomarker discovery, where the primary goal is often to identify a minimal set of molecular features—such as genes, proteins, or metabolites—that are most predictive of clinical outcomes. By automatically selecting a sparse subset of relevant features, LASSO helps create more interpretable models that are less prone to overfitting, which is crucial for developing clinically applicable diagnostic and prognostic tools [38] [39] [40].

Theoretical Foundation of L1 Regularization

Mathematical Formulation

The L1 regularization technique operates by adding a penalty term to the standard loss function of a model. This penalty term is proportional to the sum of the absolute values of the model coefficients (L1 norm). For a general linear model, the objective function for LASSO optimization can be represented as:

min (Loss Function + λ × ||β||₁)

Where:

- Loss Function represents the error between predicted and actual values (e.g., residual sum of squares for linear regression, negative log-likelihood for logistic regression)

- λ (lambda) is the regularization parameter that controls the strength of the penalty

- β represents the vector of model coefficients

- ||β||₁ is the L1 norm of the coefficient vector, calculated as the sum of absolute values of all coefficients

The regularization parameter λ plays a critical role in determining the balance between model fit and complexity. When λ = 0, the model equivalent to an unregularized model, which may overfit the training data. As λ increases, the penalty term exerts more influence, forcing more coefficients toward zero and resulting in a sparser model [37]. The optimal value of λ is typically determined through cross-validation techniques, which provide a robust assessment of model performance on unseen data [38] [37].

Comparative Analysis of Regularization Techniques

The following table compares L1 regularization with other common regularization approaches:

Table 1: Comparison of Regularization Techniques for High-Dimensional Data

| Technique | Penalty Term | Effect on Coefficients | Feature Selection | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 (LASSO) | λ × ‖β‖₁ | Shrinks coefficients to exactly zero | Yes | Sparse models, biomarker identification, when only few features are relevant |

| L2 (Ridge) | λ × ‖β‖₂² | Shrinks coefficients uniformly but not to zero | No | All features contribute, correlated features, when no feature elimination is desired |

| Elastic Net | λ₁ × ‖β‖₁ + λ₂ × ‖β‖₂² | Balances between L1 and L2 effects | Yes, but less aggressive than L1 | Highly correlated features, grouped feature selection |

The feature selection capability of L1 regularization makes it particularly suitable for biomarker discovery, where researchers often work under the assumption that only a small subset of measured molecular features has true biological relevance to the disease or condition under investigation [38] [39] [40]. By zeroing out irrelevant features, LASSO automatically performs feature selection during the model fitting process, yielding more interpretable models that are less likely to overfit to noise in the data.

Advanced L1 Regularization Strategies for Biomarker Data

SMAGS-LASSO for Sensitivity-Specificity Optimization

In clinical diagnostics, particularly for diseases with low prevalence such as cancer, standard machine learning approaches that prioritize overall accuracy may fail to align with clinical priorities. To address this challenge, researchers have developed SMAGS-LASSO (Sensitivity Maximization at a Given Specificity), which combines a custom sensitivity-maximizing loss function with L1 regularization [38]. This approach specifically addresses the need for high sensitivity in early cancer detection while maintaining high specificity to avoid unnecessary clinical procedures in healthy individuals.

The SMAGS-LASSO objective function is formulated as:

maxβ,β₀ ∑i=1n ŷi · yi / ∑i=1n yi - λ‖β‖₁

Subject to: (1 - y)ᵀ(1 - ŷ) / (1 - y)ᵀ(1 - y) ≥ SP

Where SP is the user-defined specificity threshold, and ŷi is the predicted class for observation i, determined by ŷi = I(σ(xiᵀβ + β₀) > θ), with θ being a threshold parameter adaptively determined to control specificity [38].

In synthetic datasets designed with strong sensitivity and specificity signals, SMAGS-LASSO demonstrated remarkable performance, achieving sensitivity of 1.00 compared to just 0.19 for standard LASSO at 99.9% specificity [38]. When applied to colorectal cancer biomarker data, SMAGS-LASSO showed a 21.8% improvement over standard LASSO and a 38.5% improvement over Random Forest at 98.5% specificity while selecting the same number of biomarkers [38].

Tissue-Guided LASSO for Contextual Biomarker Selection

The tissue of origin plays a critical role in cancer biology and treatment response, yet standard machine learning approaches often overlook this important contextual information. Tissue-Guided LASSO (TG-LASSO) was developed to explicitly integrate information on samples' tissue of origin with gene expression profiles to improve prediction of clinical drug response [40].

TG-LASSO addresses the fundamental challenge of predicting clinical drug response using preclinical cancer cell line data by incorporating tissue-specific constraints into the regularization process. This approach recognizes that biomarkers for drug sensitivity may vary across different tissue types, even when examining the same therapeutic compound [40].

In comprehensive evaluations using data from the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) database and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), TG-LASSO outperformed various linear and non-linear algorithms, successfully distinguishing resistant and sensitive patients for 7 out of 13 drugs tested [40]. Furthermore, genes identified by TG-LASSO as biomarkers for drug response were significantly associated with patient survival, underscoring their clinical relevance [40].

Bayesian Two-Step LASSO for Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers

In targeted therapy development, accurately identifying biomarkers that are either prognostic (associated with disease outcome regardless of treatment) or predictive (associated with differential treatment effects) represents a critical challenge. The Bayesian Two-Step Lasso strategy addresses this challenge through a sequential approach to biomarker selection [39].

The methodology employs:

- Step 1: Bayesian group Lasso to identify biomarker groups containing main effects and treatment interactions, applying loose selection criteria to screen out unimportant biomarkers

- Step 2: Bayesian adaptive Lasso for refined variable selection among biomarkers identified in the first step to distinguish prognostic and predictive markers [39]

This approach is particularly valuable in clinical trial settings for targeted therapy development, where accurately identifying biomarkers that can guide treatment assignment is essential for personalized medicine approaches. The Bayesian framework provides natural uncertainty quantification for the selected biomarkers, which is valuable for clinical decision-making [39].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

SMAGS-LASSO Implementation Protocol

Objective: Implement SMAGS-LASSO for sensitivity-maximizing biomarker selection with controlled specificity.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- High-dimensional biomarker dataset with binary clinical outcomes

- Python programming environment with NumPy, SciPy, and scikit-learn libraries

- Computational resources capable of parallel processing

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Standardize features to have zero mean and unit variance

- Perform 80/20 stratified train-test split to maintain class balance

Parameter Initialization:

- Initialize coefficients using standard logistic regression

- Define λ sequence from λmax (all coefficients zero) to λmin (minimal regularization)

- Set target specificity threshold SP based on clinical requirements

Multi-Algorithm Optimization:

- Execute parallel optimization using Nelder-Mead, BFGS, CG, and L-BFGS-B algorithms

- Apply tolerance levels from 1e-5 to 1e-8 for each algorithm

- Select model with highest sensitivity among converged solutions

Cross-Validation:

- Implement 5-fold cross-validation

- For each λ, calculate sensitivity MSE: MSE_sensitivity = [1 - (∑ŷᵢ·yᵢ / ∑yᵢ)]²

- Compute norm ratio ‖β_λ‖₁ / ‖β‖₁ to quantify sparsity

- Select λ that minimizes sensitivity MSE while maintaining specificity constraint

Feature Selection:

- Retain features with absolute coefficient values exceeding 5% of the largest coefficient's absolute value

- Validate selected features on held-out test set

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For non-convergence, increase number of parallel optimizations or adjust tolerance levels

- If specificity constraint is violated, increase SP parameter or adjust threshold θ

- For unstable feature selection, implement bootstrap aggregation of SMAGS-LASSO models

Tissue-Guided LASSO Experimental Protocol

Objective: Predict clinical drug response using preclinical cancer cell line data with tissue-specific regularization.

Data Requirements:

- Gene expression profiles and drug response data from GDSC database

- Gene expression profiles and clinical drug response from TCGA

- Tissue type annotations for all samples

Methodology:

- Data Harmonization:

- Match gene expression features between GDSC and TCGA datasets

- Align drug response measures (e.g., IC50 for GDSC, clinical response for TCGA)

- Annotate samples by tissue of origin

TG-LASSO Implementation:

- Implement tissue-specific penalty parameters λ_t for each tissue type t

- Optimize objective function: min‖Y - Xβ‖₂² + ∑t λt ‖β_t‖₁

- Where β_t represents coefficients for tissue type t

Model Validation:

- Train on entire GDSC dataset with tissue-specific constraints

- Validate on TCGA data using tissue-stratified performance metrics

- Assess ability to distinguish resistant vs. sensitive patients via ROC analysis

Biomarker Identification:

- Extract non-zero coefficients for each tissue-drug combination

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis on selected genes

- Validate biological relevance through literature mining and survival analysis

Validation Metrics:

- Area under ROC curve (AUC) for patient stratification

- Statistical significance of survival differences between predicted sensitive and resistant groups

- Enrichment of known drug targets in selected biomarkers

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Biomarker Discovery Using L1 Regularization

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GDSC Database | Provides gene expression and drug sensitivity data for cancer cell lines | Training dataset for preclinical-to-clinical prediction models [40] |

| TCGA Data Portal | Offers molecular profiles and clinical data for patient tumors | Validation dataset for clinical relevance of identified biomarkers [40] |

| Bayesian Lasso Software | Implements Bayesian versions of Lasso with uncertainty quantification | Probabilistic biomarker selection for targeted therapy development [39] |

| mindLAMP Platform | Collects and visualizes digital biomarker data from smartphone sensors | Visualization and interpretation of digital biomarkers for clinical communication [41] |

| Cross-Validation Framework | Assesses model performance and selects regularization parameters | Preventing overfitting and ensuring robust biomarker selection [38] [36] |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

SMAGS-LASSO Optimization Workflow

Tissue-Guided LASSO Conceptual Framework

High-Dimensional Data Challenge and Regularization Solution

L1 regularization represents a powerful approach for feature selection in high-dimensional biomarker data, directly addressing the challenge of overfitting that plagues traditional statistical methods in high-dimensional settings [36] [37]. The fundamental capability of LASSO to perform automatic feature selection while maintaining model performance makes it particularly valuable for biomarker discovery, where identifying minimal feature sets with maximal predictive power is often a primary objective.

Advanced variants of LASSO, including SMAGS-LASSO, Tissue-Guided LASSO, and Bayesian Two-Step Lasso, demonstrate how domain-specific adaptations can enhance the basic methodology to address specific challenges in clinical translation [38] [39] [40]. These specialized approaches acknowledge that clinical utility requires not just statistical performance but also alignment with clinical priorities, biological context, and implementation practicalities.

As biomarker data continues to grow in dimensionality and complexity, with emerging data types from digital health technologies and multi-omics platforms, the importance of robust feature selection methodologies will only increase [41]. L1 regularization and its evolving variants provide a foundational framework for extracting clinically meaningful signals from high-dimensional data, ultimately supporting the development of more precise diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive tools in personalized medicine.

Within the broader thesis on regularization techniques for preventing overfitting in predictive research, L2 regularization, or Ridge Regression, occupies a critical position as a stabilizer for models plagued by multicollinearity. Unlike methods that perform feature selection, Ridge regression addresses the instability of coefficient estimates when independent variables are highly correlated, a common scenario in high-dimensional biological and chemical data [42] [43] [44]. This document serves as an Application Note and Protocol, detailing the implementation, rationale, and practical application of Ridge regression, specifically tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development where model reliability is paramount.

Mathematical Foundation and Core Mechanism

Ridge regression modifies the ordinary least squares (OLS) objective function by adding a penalty term proportional to the sum of the squared coefficients. This L2 penalty shrinks coefficients towards zero but rarely sets them to exactly zero [43] [44].

Core Objective Function:

The Ridge estimator minimizes the following cost function:

argmin(||y - Xβ||² + λ||β||²)

Where:

yis the vector of observed target values.Xis the matrix of predictor variables.βis the vector of regression coefficients to be estimated.λ(lambda,alphain scikit-learn) is the regularization hyperparameter controlling penalty strength [42] [45].

Closed-Form Solution:

The solution is given by:

β̂_ridge = (XᵀX + λI)⁻¹ Xᵀy

The addition of λI (where I is the identity matrix) ensures the matrix (XᵀX + λI) is always invertible, even when XᵀX is singular due to perfect multicollinearity, thus providing stable coefficient estimates [44] [46].

Bias-Variance Tradeoff:

The introduction of the penalty term intentionally increases model bias (a slight systematic error) to achieve a greater reduction in variance (sensitivity to fluctuations in training data). This tradeoff is central to Ridge's ability to improve generalization to unseen test data [43] [46]. When λ=0, the model reverts to OLS with high variance risk. As λ → ∞, coefficients shrink excessively toward zero, leading to high bias and underfitting [42].

Comparative Analysis of Regularization Techniques

Ridge regression is one of several regularization methods. Its properties are best understood in contrast to alternatives like Lasso (L1) and Elastic Net.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Regularization Techniques for Linear Regression

| Technique | Penalty Term | Effect on Coefficients | Key Strength | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ridge (L2) | λ∑βᵢ² | Shrinks all coefficients proportionally; rarely sets any to zero. | Stabilizes estimates, handles multicollinearity well. | All predictors are relevant; primary issue is correlated features. |

| Lasso (L1) | λ∑|βᵢ| | Can shrink coefficients to exactly zero, performing automatic feature selection. | Creates sparse, interpretable models. | Suspected many irrelevant features; goal is variable selection. |

| Elastic Net | λ₁∑|βᵢ| + λ₂∑βᵢ² | Hybrid: can both select variables and shrink coefficients. | Balances Ridge and Lasso; good for high-dimensional data with correlated features. | Situations with many correlated predictors where some selection is also desired. [42] [43] [46] |

Application Protocols and Implementation

General Protocol for Ridge Regression Modeling

Objective: To construct a stable linear regression model in the presence of correlated predictors. Workflow: The following diagram outlines the standardized protocol.

Detailed Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Scale or standardize features so that the L2 penalty is applied uniformly [46]. Remove outliers that could disproportionately influence the model; for example, the Isolation Forest algorithm was used to remove 973 outlier points in a pharmaceutical study [47].

- Hyperparameter Tuning (λ/α Selection): Use k-fold cross-validation on the training set to evaluate a range of

αvalues. The optimalαis typically the one that minimizes the cross-validated Mean Squared Error (MSE) or maximizes R², balancing bias and variance [43] [46]. - Model Training: Fit the Ridge regression model using the optimal

α. In Python's scikit-learn, theRidgeorRidgeCVclasses are used [42] [45]. - Evaluation: Assess the final model on a completely held-out test set using metrics like R², Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [47].

Protocol: Application in Pharmaceutical Drying Process Modeling

This protocol is adapted from a study predicting chemical concentration distribution during lyophilization [47].

Objective: To predict concentration (C in mol/m³) at spatial coordinates (X, Y, Z) using Ridge Regression as one of several benchmark models.

Dataset: Over 46,000 data points generated from numerical simulation of mass transfer equations.

Preprocessing Protocol:

- Outlier Removal: Apply the Isolation Forest (IF) algorithm, an unsupervised ensemble method, with a contamination parameter of 0.02 to identify and remove anomalous data points [47].

- Normalization: Use Min-Max scaling to normalize all feature values to a common range (e.g., [0,1]).

- Data Splitting: Randomly split the processed data into training (~80%) and testing (~20%) sets. Modeling Protocol:

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Utilize an advanced optimization algorithm (e.g., Dragonfly Algorithm) to tune the Ridge regression hyperparameter (

α), with the objective of maximizing the mean 5-fold cross-validated R² score to enhance generalizability [47]. - Training & Benchmarking: Train the optimized Ridge model and compare its performance against other models like Support Vector Regression (SVR) and Decision Trees on the test set.

The Scientist's Computational Toolkit

| Research Reagent (Tool/Algorithm) | Function in Protocol | Key Property / Purpose |

|---|---|---|

Scikit-learn Ridge / RidgeCV |

Core model implementation and hyperparameter tuning. | Provides efficient, numerically stable solvers (e.g., 'svd', 'cholesky', 'sag') for fitting the Ridge model [45]. |

| Isolation Forest Algorithm | Data preprocessing for outlier detection. | Unsupervised method efficient for identifying anomalies in high-dimensional data without needing labeled outliers [47]. |

| Dragonfly Algorithm (DA) | Hyperparameter optimization metaheuristic. | Used to find the optimal regularization parameter (α) by maximizing cross-validated model generalizability [47]. |

| Min-Max Scaler | Feature normalization preprocessing step. | Ensures all input features contribute equally to the L2 penalty term by scaling them to a fixed range [47]. |

| Cross-Validation (k-Fold) | Model validation and hyperparameter selection. | Robust method for estimating model performance and tuning α without leaking test set information [46]. |

Experimental Data & Results in Pharmaceutical Research Context

The utility of Ridge regression is demonstrated in computational biology and drug discovery, where datasets often have many correlated predictors (e.g., molecular descriptors) and a relatively small sample size [43] [48].

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Pharmaceutical Drying Study [47]

| Machine Learning Model | Optimization Method | Test R² Score | Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | Key Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) | Dragonfly Algorithm (DA) | 0.999234 | 1.2619E-03 | Best performance; excellent generalization from train (R²=0.999187). |

| Decision Tree (DT) | Dragonfly Algorithm (DA) | (Reported lower than SVR/RR) | (Reported higher than SVR) | Likely prone to overfitting despite optimization. |

| Ridge Regression (RR) | Dragonfly Algorithm (DA) | (Reported, outperformed DT) | (Reported) | Served as a stable, regularized linear benchmark; outperformed DT but was surpassed by the non-linear SVR model. |

Interpretation: While the study found SVR to be superior for the specific non-linear problem, Ridge Regression provided a crucial, stable baseline. Its performance, enhanced by DA optimization, underscores its value as a reliable method when model interpretability and stability are prioritized over maximum predictive power in complex, correlated data environments common in pharmaceutical research [47] [49].

In the field of omics research, including genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics, the fundamental challenge is the "large p, small n" problem, where the number of predictors (p, e.g., genes, proteins) vastly exceeds the number of observations (n, e.g., patient samples) [50] [51]. This high-dimensional data landscape creates significant risks of overfitting, where models memorize noise and technical artifacts rather than capturing biologically meaningful signals [52]. Regularization techniques have emerged as essential statistical tools to address this challenge by constraining model complexity and promoting generalizability [53] [54].

Elastic Net regularization represents an advanced hybrid approach that synergistically combines the L1 (Lasso) and L2 (Ridge) penalty terms [55]. This combination addresses critical limitations of using either regularizer alone when analyzing omics data, where correlated biomarkers frequently occur in biological pathways [51] [52]. For instance, in transcriptomic analyses, genes operating in coordinated pathways often exhibit high correlation, presenting challenges for variable selection methods that might arbitrarily choose one representative from a functionally related group [50] [51].

The mathematical formulation of Elastic Net incorporates both L1 and L2 regularization through a weighted sum of their penalty terms, controlled by the mixing parameter α (alpha) and overall regularization strength λ (lambda) [56] [55]. This combined approach enables the model to maintain the sparsity-inducing properties of Lasso (effective for feature selection) while retaining the group-handling capabilities of Ridge (effective for correlated variables) [55] [52]. The resulting models demonstrate enhanced stability and predictive performance across diverse omics applications, from immune cell classification using RNA-seq data to disease outcome prediction from multi-omics platforms [50] [51].

Theoretical Foundation and Algorithmic Specifications

Mathematical Formulation

The Elastic Net penalty is defined through a linear combination of the L1 and L2 regularization terms, added to the conventional loss function. For a generalized linear model, the objective function to minimize becomes:

Loss = Losscomponent + λ × [ α × ‖β‖1 + (1 - α) × ‖β‖2 ]

Where:

- Losscomponent represents the conventional loss (e.g., squared error for regression, logistic loss for classification)

- ‖β‖1 = Σ|βj| is the L1 norm (sum of absolute coefficients)

- ‖β‖2 = Σβj2 is the L2 norm (sum of squared coefficients)

- λ ≥ 0 controls the overall regularization strength

- α ∈ [0,1] determines the mixing ratio between L1 and L2 penalties [56] [55] [52]

Table 1: Comparison of Regularization Techniques in High-Dimensional Omics Data

| Feature | L1 (Lasso) | L2 (Ridge) | Elastic Net |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sparsity | Produces sparse models (some coefficients exactly zero) | Shrinks coefficients but rarely sets them to zero | Balanced sparsity through mixed penalties |

| Handling Correlated Features | Selects one from correlated group, ignores others | Distributes weight among correlated features | Maintains groups of correlated features |

| Feature Selection | Built-in feature selection | No inherent feature selection | Grouping effect with selective capability |

| Computational Efficiency | Efficient for high-dimensional data | Highly efficient | Moderately efficient |

| Stability | Unstable with correlated variables | High stability | Improved stability over Lasso |

Optimization and Parameter Interpretation

The Elastic Net optimization problem maintains strong convexity, ensuring a unique minimum—a critical property that distinguishes it from non-convex regularization approaches [57]. The hybrid penalty function enables Elastic Net to overcome the limitation of Lasso, which can select at most n variables when p > n, making it particularly suitable for omics studies where the number of biomarkers frequently exceeds sample size by orders of magnitude [55].