Reconstructing Gene Regulatory Networks: From Single-Cell Data to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern methods for reconstructing Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs), which are crucial for understanding cellular mechanisms, disease progression, and drug discovery.

Reconstructing Gene Regulatory Networks: From Single-Cell Data to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern methods for reconstructing Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs), which are crucial for understanding cellular mechanisms, disease progression, and drug discovery. It explores the foundational principles of GRNs, categorizes the latest computational and machine learning inference techniques, and addresses key challenges like data sparsity and network dynamics. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, the content highlights the integration of single-cell multi-omic data, offers strategies for model optimization and validation, and discusses the transformative potential of these methods in personalized medicine and therapeutic development.

The Blueprint of Life: Understanding Gene Regulatory Networks and Their Biological Significance

A Gene Regulatory Network (GRN) is a complex system of molecular interactions where transcription factors (TFs), regulatory elements, and target genes interact to control cellular processes [1]. These networks determine development, differentiation, and cellular response to environmental stimuli by orchestrating precise gene expression patterns [1]. In its simplest representation, a GRN consists of genes as nodes with directed edges representing regulatory interactions between them [1]. The reconstruction of these networks—identifying the causal relationships and regulatory hierarchies between genes—has become fundamental to understanding how cellular phenotypes emerge from genetic information.

GRN inference has evolved significantly from early molecular biology techniques to modern computational approaches. While early methods relied on techniques like DNA foot printing and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) to identify TF binding sites [1], the advent of high-throughput sequencing technologies has transformed the field. Contemporary GRN inference leverages multi-omics data—including transcriptomics (RNA-seq), epigenomics (ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq), and chromatin conformation (Hi-C)—to reconstruct comprehensive regulatory networks [2] [1]. The emergence of single-cell technologies has further revolutionized GRN analysis by enabling the resolution of cellular heterogeneity and the identification of cell-type specific regulatory programs [3] [2].

Computational Methodologies for GRN Inference

Methodological Foundations

Computational GRN inference methods employ diverse mathematical and statistical approaches to identify regulatory relationships from omics data. These methodologies can be broadly categorized into several foundational frameworks:

Correlation-based approaches operate on the "guilt by association" principle, where co-expressed genes are assumed to be functionally related or co-regulated [2]. These methods use measures like Pearson's correlation, Spearman's correlation, or mutual information to detect associations between TFs and potential target genes. While computationally efficient, correlation alone cannot distinguish direct from indirect relationships or establish regulatory directionality [2].

Regression models frame GRN inference as a problem of predicting gene expression based on potential regulators. The expression of each target gene is regressed against the expression or accessibility of multiple TFs and cis-regulatory elements [2]. Penalized regression methods like LASSO introduce regularization to handle high-dimensional data and prevent overfitting by shrinking coefficients of irrelevant predictors toward zero [2] [1].

Probabilistic models represent GRNs as graphical models that capture dependence structures between variables [2]. These approaches estimate the probability of regulatory relationships existing between TFs and their putative target genes, allowing for filtering and prioritization of interactions before downstream analyses [2].

Dynamical systems approaches model gene expression as systems that evolve over time, using differential equations to capture factors like regulatory effects, basal transcription, and stochasticity [2]. These models are particularly valuable for time-course data and can provide interpretable parameters corresponding to specific biological properties [2].

Deep learning models have emerged as powerful frameworks for capturing complex, nonlinear regulatory relationships [2] [1]. Architectures including convolutional neural networks (CNNs), variational autoencoders (VAEs), graph neural networks (GNNs), and transformers can learn hierarchical representations from large-scale omics data [1]. While often requiring substantial computational resources and training data, these approaches can model intricate regulatory patterns that simpler methods may miss [2].

Machine Learning Paradigms for GRN Inference

Machine learning approaches for GRN inference can be categorized based on their learning paradigms, each with distinct advantages and applications:

Table 1: Machine Learning Paradigms for GRN Inference

| Learning Paradigm | Key Characteristics | Representative Algorithms | Typical Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Uses labeled training data of known regulatory interactions to predict novel TF-target relationships | GENIE3, DeepSEM, GRNFormer, SIRENE | Experimentally validated regulatory pairs, curated databases |

| Unsupervised Learning | Identifies regulatory patterns without prior knowledge of interactions | ARACNE, CLR, LASSO, GRN-VAE | Large-scale gene expression data without labeled examples |

| Semi-Supervised Learning | Combines limited labeled data with larger unlabeled datasets | GRGNN | Mixed labeled and unlabeled datasets |

| Contrastive Learning | Learns representations by contrasting positive and negative examples | GCLink, DeepMCL | Paired similar and dissimilar regulatory examples |

Supervised learning methods leverage known regulatory interactions to train models that can then predict novel TF-target relationships [1]. For example, GENIE3 (Random Forest-based) and DeepSEM (deep learning-based) have demonstrated strong performance in supervised GRN inference [1]. These approaches require high-quality labeled datasets, which can be limited for non-model organisms or specific cellular contexts.

Unsupervised methods like ARACNE (using mutual information) and LASSO (regression-based) identify regulatory relationships without labeled training examples, making them applicable to exploratory analyses where comprehensive ground truth data is unavailable [1].

Hybrid approaches that combine deep learning with traditional machine learning have shown particularly promising results. Recent research demonstrates that hybrid models integrating convolutional neural networks with machine learning classifiers can achieve over 95% accuracy in predicting regulatory relationships in plant systems [4]. These frameworks leverage the feature learning capabilities of deep learning with the classification strength and interpretability of traditional machine learning.

Advanced Deep Learning Architectures

Recent advances in deep learning have introduced sophisticated architectures specifically designed for GRN inference:

GRAPH NEURAL NETWORKS (GNNS) model regulatory networks as graph structures, allowing them to capture topological properties and propagation of regulatory signals [1]. Methods like GRGNN use semi-supervised learning on graph-structured data to predict regulatory relationships [1].

VARIATIONAL AUTOENCODERS (VAES) learn compressed representations of gene expression data that can capture latent regulatory factors [1]. GRN-VAE uses this approach to infer GRNs from single-cell RNA-seq data by modeling the joint distribution of gene expression [1].

TRANSFORMER ARCHITECTURES with attention mechanisms can model long-range dependencies and context-aware regulatory relationships [1]. GRNFormer employs graph transformers to capture complex regulatory patterns in single-cell data [1].

MULTI-MODAL INTEGRATION FRAMEWORKS like scMODAL leverage known feature links to align single-cell omics data, enabling more accurate integration and regulatory inference [5]. These approaches are particularly valuable for integrating matched scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data to reconstruct comprehensive regulatory networks.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Basic GRN Inference from Single-Cell RNA-seq Data

This protocol outlines a standard workflow for inferring gene regulatory networks from single-cell RNA sequencing data using the SCENIC pipeline, which integrates network inference with TF regulatory activity assessment [3].

Materials and Reagents

- Single-cell RNA sequencing data (count matrix)

- Reference genome and gene annotation files

- TF binding motif databases (e.g., JASPAR, CIS-BP)

- Computing resources with minimum 16GB RAM for typical datasets

Procedure

- DATA PREPROCESSING

- Quality control: Filter cells based on mitochondrial gene percentage, unique gene counts, and total counts

- Normalize expression values using standard scRNA-seq methods (e.g., SCTransform, log-normalization)

- Identify highly variable genes to focus computational resources on biologically meaningful signals

GENE REGULATORY NETWORK INFERENCE

- Apply correlation-based method (e.g., GENIE3 or GRNBoost2) to identify potential TF-target relationships

- Calculate regulatory potential between all TFs and potential target genes

- Retain only relationships with significant association scores (p-value < 0.001 after multiple testing correction)

REGULON PRUNING WITH CIS-REGULATORY INFORMATION

- Scan promoter regions of target genes (typically -500bp to +100bp from TSS) for TF binding motifs

- Retain only TF-target pairs where significant expression correlation is supported by presence of corresponding TF binding motif

- Define final regulons—sets of genes regulated by each TF—based on supported relationships

CELLULAR REGULON ACTIVITY QUANTIFICATION

- Calculate regulon activity scores for each cell using AUCell algorithm

- Cluster cells based on regulon activity rather than gene expression

- Identify cell-type specific regulatory programs from activity patterns

VALIDATION AND INTERPRETATION

- Compare inferred regulons with previously validated regulatory interactions from literature

- Perform functional enrichment analysis on target genes within regulons

- Integrate with additional omics data where available for confirmation

Troubleshooting Tips

- Low correlation values may indicate need for batch effect correction

- Poor motif enrichment suggests potential issues with reference genome or motif database compatibility

- Sparse regulons may result from overly stringent pruning thresholds

Protocol 2: Multi-omic GRN Inference Using Paired scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq

This advanced protocol leverages paired single-cell multi-omics data to reconstruct more accurate and context-specific gene regulatory networks by integrating transcriptomic and epigenomic information.

Materials and Reagents

- Paired scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data from the same cells

- Reference genome with chromosome sizes file

- Pre-computed TF binding motif position weight matrices

- Peak calling software (e.g., MACS2)

Procedure

- DATA PREPROCESSING AND INTEGRATION

- Process scRNA-seq data following standard normalization and QC pipelines

- Process scATAC-seq data: peak calling, quality metrics, and elimination of low-quality cells

- Harmonize cell identities between modalities using shared unique molecular identifiers or cell hashing information

- Create a weighted nearest neighbors graph to integrate the two modalities

REGULATORY POTENTIAL CALCULATION

- Identify accessible TF binding sites from scATAC-seq peaks

- Link distal regulatory elements to potential target genes using correlation between accessibility and expression

- Calculate correlation between TF expression and target gene expression across the single-cell population

- Integrate TF expression, chromatin accessibility, and binding motif information to score potential regulatory interactions

NETWORK INFERENCE USING DEEP LEARNING

- Implement a multi-modal neural network architecture (e.g., scTFBridge) that disentangles shared and specific components across omics layers

- Train the model to predict gene expression from both TF expression and chromatin accessibility patterns

- Extract significant regulatory interactions from the trained model weights and attention mechanisms

NETWORK VALIDATION AND REFINEMENT

- Validate network edges using orthogonal data (e.g., ChIP-seq, Perturb-seq) where available

- Compare network topology with known hierarchical regulatory structures

- Perform stability analysis through bootstrap resampling or cross-validation

CONTEXT-SPECIFIC SUBNETWORK IDENTIFICATION

- Identify regulatory programs specific to cell states or conditions

- Perform differential network analysis between experimental conditions

- Extract master regulator TFs driving cellular phenotypes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for GRN Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| JASPAR Database | Database | Curated collection of TF binding profiles | Motif scanning for regulon pruning [3] |

| SCENIC | Computational Pipeline | Integrated GRN inference from scRNA-seq | Identification of regulons and cellular activity [3] |

| GENIE3 | Algorithm | Random Forest-based GRN inference | Initial network inference from expression data [1] |

| GRN-VAE | Deep Learning Model | Variational autoencoder for GRN inference | Network modeling from single-cell data [1] |

| CellRank | Computational Tool | Cell fate mapping and trajectory inference | Dynamic GRN analysis along differentiation trajectories |

| 10x Multiome | Experimental Platform | Simultaneous scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq | Multi-omic GRN inference [2] |

| SHARE-Seq | Experimental Protocol | High-throughput multi-omics profiling | Multi-modal GRN reconstruction [2] |

| Perturb-Seq | Screening Method | CRISPR screening with single-cell readout | Causal validation of regulatory interactions [5] |

| Fly Cell Atlas | Reference Data | Single-nucleus transcriptomic atlas | Reference data for cross-species comparisons [3] |

| DeepIMAGER | Deep Learning Tool | CNN-based GRN inference | Supervised network prediction [1] |

| Antiangiogenic agent 3 | Antiangiogenic agent 3|RUO|VEGF Inhibitor | Antiangiogenic agent 3 is a potent VEGF signaling pathway inhibitor for cancer research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| c-Met-IN-9 | c-Met-IN-9|Potent c-Met Kinase Inhibitor|RUO | Bench Chemicals |

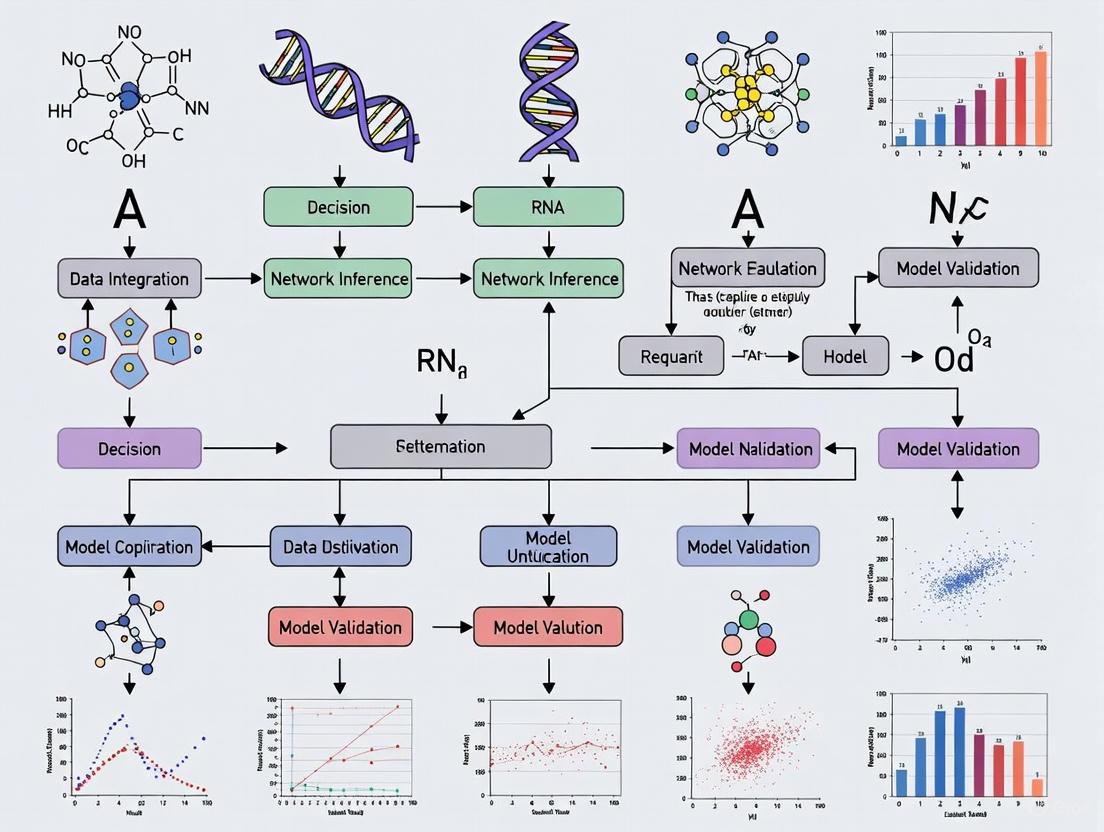

Visualization of GRN Inference Workflows

Conceptual Framework of Gene Regulatory Networks

Multi-omic GRN Inference Workflow

Applications in Disease Research and Drug Development

GRN analysis has proven particularly valuable in understanding disease mechanisms and identifying therapeutic targets. In cancer research, differential GRN analysis between drug-sensitive and resistant cells has revealed key regulatory programs driving treatment resistance. In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), azacitidine resistance-specific networks have been identified, highlighting metallothionein gene family interactions and regulatory relationships between RBM47, ELF3, and GRB7 as crucial factors [6]. These resistance-specific networks display distinct topology compared to sensitive cells, with denser interconnections in resistant cell lines [6].

The application of GRN inference in pharmaceutical development includes:

- IDENTIFICATION OF MASTER REGULATORS driving disease states, which represent potential therapeutic targets

- NETWORK-BASED DRUG REPOSITIONING by mapping drug effects onto regulatory networks

- STRATIFICATION OF PATIENT POPULATIONS based on regulatory subtypes rather than just genetic mutations

- PREDICTION OF RESISTANCE MECHANISMS before they emerge in clinical settings

For example, network-based analysis of mepolizumab (anti-IL-5 therapy) treatment in asthma patients revealed how the drug alters type-2 and epithelial inflammation networks in nasal airways, providing insights into its mechanism of action and potential biomarkers for treatment response [5].

Future Perspectives and Challenges

Despite significant advances, GRN inference still faces several challenges that represent opportunities for future methodological development:

- DATA INTEGRATION across multiple omics layers, time points, and experimental conditions remains computationally complex

- CELLULAR HETEROGENEITY even within supposedly homogeneous cell populations complicates network inference

- CONTEXT SPECIFICITY of regulatory interactions requires condition-specific network modeling

- CAUSAL INFERENCE from observational data remains challenging without perturbation experiments

Emerging approaches are addressing these challenges through multi-modal deep learning frameworks, transfer learning across species [4], and integration of perturbation data to establish causal relationships. Methods like HALO (Hierarchical causal modeling) examine epigenetic plasticity and gene regulation dynamics in single-cell multi-omic data, enabling more accurate causal inference [5]. Transfer learning approaches are particularly promising for extending GRN analysis to non-model organisms or rare cell types with limited data [4].

As single-cell multi-omics technologies continue to advance and computational methods become more sophisticated, the reconstruction of comprehensive, dynamic, and context-specific gene regulatory networks will increasingly illuminate the fundamental principles governing cellular phenotype and provide novel insights for therapeutic development.

The Critical Role of GRNs in Development, Disease, and Drug Response

Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) are complex, directed networks of molecular interactions where transcription factors (TFs) regulate their target genes by controlling their activation and silencing in specific cellular contexts [7]. These networks form the fundamental control system that dictates cellular identity, function, and response to external signals. The directed edges in GRNs represent causal regulatory relationships from TFs to genes, establishing a hierarchical organization that governs core developmental and biological processes underlying complex traits [8]. Understanding GRN architecture is crucial for explaining how cells perform diverse functions, alter gene expression in different environments, and how noncoding genetic variants cause disease [7].

GRNs exhibit several key structural properties that are highly relevant for their functional analysis. Biological GRNs are notably sparse, meaning the typical gene is directly affected by a much smaller number of regulators than the total number available in the network [8]. They also demonstrate modular organization and feature a degree distribution that follows an approximate power-law, leading to emergent properties including group-like structure and enrichment for specific structural motifs [8]. The directed nature of edges with potential feedback loops adds another layer of complexity, enabling sophisticated control mechanisms that fine-tune cellular processes [8].

Table 1: Key Properties of Biological Gene Regulatory Networks

| Property | Description | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Sparsity | Most genes are regulated by a small subset of potential regulators | Enables specific control and reduces crosstalk between unrelated processes |

| Directed Edges | Regulatory relationships have direction (TF → gene) | Establishes causal hierarchy and information flow |

| Feedback Loops | Presence of reciprocal regulation | Enables fine-tuning and homeostatic control |

| Modular Organization | Grouping of genes into functional units | Supports coordinated expression of functionally related genes |

| Hierarchical Structure | Layered organization of regulators | Establishes developmental trajectories and cellular decision-making |

Computational Reconstruction of GRNs: Methodological Advances

The reconstruction of high-resolution GRNs from experimental data represents a significant challenge in systems biology. Traditional experiment-based approaches tend to focus on specific functional pathways rather than reconstructing entire networks, making them time-consuming and labor-intensive for comprehensive GRN mapping [9]. Computational methods have emerged as powerful alternatives, particularly with the advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technology, which reveals biological signals in gene expression profiles of individual cells without requiring purification of each cell type [9].

Machine Learning Frameworks for GRN Inference

Current computational methods for GRN inference can be broadly categorized into unsupervised and supervised approaches. Unsupervised methods discover latent patterns from scRNA-seq data and infer regulatory relationships using statistical or computational techniques, while supervised methods construct training sets with known GRNs as labels and scRNA-seq data as features, then use deep learning to learn regulatory knowledge from the training set [9]. Supervised models generally achieve higher accuracy because they can learn prior knowledge from labels and identify subtle differences between training samples through deep learning technologies [9].

Recent advances in graph neural networks (GNNs) have particularly transformed GRN reconstruction. Several innovative frameworks have demonstrated exceptional performance:

GAEDGRN: This framework employs a gravity-inspired graph autoencoder (GIGAE) to capture complex directed network topology in GRNs, which traditional methods often ignore. It incorporates an improved PageRank* algorithm to calculate gene importance scores based on out-degree (genes regulating many others are considered important) and uses random walk regularization to standardize the learning of gene latent vectors. Experimental results across seven cell types of three GRN types show that GAEDGRN achieves high accuracy and strong robustness while reducing training time [9].

LINGER: This method represents a breakthrough through lifelong learning that incorporates atlas-scale external bulk data across diverse cellular contexts. LINGER uses a neural network model pre-trained on external bulk data from sources like the ENCODE project, then refines on single-cell data using elastic weight consolidation (EWC) loss. This approach achieves a fourfold to sevenfold relative increase in accuracy over existing methods and enables estimation of transcription factor activity solely from gene expression data [7].

HyperG-VAE: This Bayesian deep generative model leverages hypergraph representation to model scRNA-seq data, addressing both cellular heterogeneity and gene modules simultaneously. The model features a cell encoder with a structural equation model to account for cellular heterogeneity and a gene encoder using hypergraph self-attention to identify gene modules. This approach enhances the imputation of contact maps and effectively uncovers gene regulation patterns [10].

GRANet: This framework utilizes residual attention mechanisms to adaptively learn complex gene regulatory relationships while integrating multi-dimensional biological features. Evaluation across multiple datasets demonstrates that GRANet consistently outperforms existing methods in GRN inference tasks [11].

Table 2: Advanced Computational Methods for GRN Reconstruction

| Method | Core Approach | Key Innovation | Reported Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAEDGRN | Gravity-inspired graph autoencoder | Directed network topology capture | High accuracy & reduced training time |

| LINGER | Lifelong learning with external data | Bulk data integration via EWC regularization | 4-7x accuracy improvement |

| HyperG-VAE | Hypergraph variational autoencoder | Simultaneous modeling of cells and genes | Enhanced imputation and pattern discovery |

| GRANet | Graph residual attention network | Multi-dimensional feature integration | Consistent outperformance vs. benchmarks |

| PRISM-GRN | Bayesian multiomics integration | Biologically interpretable architecture | Higher precision in sparse regulatory scenarios |

Addressing Key Challenges in GRN Inference

Despite these advancements, GRN inference faces several persistent challenges. Limited independent data points remain a significant hurdle, as single-cell data, while containing many cells, offers limited true independence between measurements [7]. The incorporation of prior knowledge such as motif matching into non-linear models also presents technical difficulties [7]. Furthermore, the inherent imbalance in GRN inference, where true regulatory interactions are sparse compared to all possible interactions, demands specialized approaches to maintain precision [12].

The PRISM-GRN framework addresses some of these challenges by seamlessly incorporating known GRNs along with scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data into a probabilistic framework. Its biologically interpretable architecture is firmly rooted in the established gene regulatory mechanism that asserts gene expression is influenced by TF expression levels and gene chromatin accessibility through GRNs [12]. This approach demonstrates higher precision under inherently imbalanced scenarios and captures causality in gene regulation derived from its interpretable architecture [12].

Diagram 1: GRN Reconstruction Framework Integrating Multi-modal Data

Application Note 1: GRNs in Development and Cellular Differentiation

GRNs play a fundamental role in guiding developmental processes and cellular differentiation. During development, hierarchical GRN structures enable the progressive restriction of cell fates, establishing distinct cellular identities from pluripotent precursors. The directed nature of regulatory interactions allows for precise temporal control of gene expression, while feedback loops provide stability to differentiated states once established [8].

Single-cell RNA sequencing technologies have been particularly instrumental in enabling functional studies of GRNs during development. Observational studies of single cells have revealed substantial diversity and heterogeneity in the cell types that comprise healthy tissues, and molecular models of transcriptional systems have been used to understand the developmental processes involved in maintaining cell state and cell cycle [8]. The emergence of CRISPR-based molecular perturbation approaches like Perturb-seq has further enhanced our ability to learn the local structure of GRNs around focal genes or pathways during developmental transitions [8].

Protocol: Inferring Developmental GRNs from Single-Cell Multiome Data

Objective: Reconstruct cell type-specific GRNs during cellular differentiation using single-cell multiome data (paired scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq).

Materials and Reagents:

- Single-cell multiome data from developing tissue

- Reference GRN database (e.g., RegNetwork 2025)

- High-performance computing environment

- LINGER software package

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Perform quality control on single-cell multiome data

- Filter cells based on RNA count, gene detection, and mitochondrial percentage

- Normalize gene expression counts using SCTransform

- Process scATAC-seq data using Signac or similar package

- Cell Type Annotation:

- Integrate scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data using Harmony

- Cluster cells based on combined modalities

- Annotate cell types using reference datasets and marker genes

- LINGER Model Configuration:

- Download and preprocess external bulk data from ENCODE

- Initialize BulkNN model with architecture matching target cell types

- Set parameters for elastic weight consolidation regularization

- Model Training and Refinement:

- Pre-train neural network on external bulk data (BulkNN)

- Refine model on single-cell data using EWC loss

- Iterate until validation loss stabilizes (typically 50-100 epochs)

- GRN Extraction and Validation:

- Calculate Shapley values to estimate regulatory strengths

- Extract TF-TG, RE-TG, and TF-RE interactions

- Validate against ChIP-seq ground truth data where available

- Perform functional enrichment on identified regulons

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If model fails to converge, reduce learning rate or increase EWC regularization strength

- For poor integration between modalities, adjust Harmony integration parameters

- If computational resources are limited, subset to top variable genes and TFs

Application Note 2: GRNs in Disease Pathogenesis

Dysregulated GRNs underlie the pathogenesis of numerous complex diseases, particularly cancers. In gliomas, the most common and aggressive primary tumors of the central nervous system, dysregulated transcription factors and genes have been implicated in tumor progression, with the overall structure of GRNs playing a defining role in disease severity and treatment response [13]. Analysis of transcriptional data from 989 primary gliomas in TCGA and CGGA databases has revealed that regulon activity patterns distinctly cluster according to WHO grade 04 samples and other samples associated with poor overall survival [13].

Case Study: Prognostic GRN Signatures in Gliomas

Comprehensive GRN analysis in gliomas has identified specific regulons—sets of genes regulated by a common transcription factor—with significant prognostic value. Through elastic net regularization and Cox regression applied to GRNs reconstructed using the RTN package, researchers identified 31 and 32 prognostic genes in TCGA and CGGA datasets, respectively, with 11 genes overlapping [13]. Among these, GAS2L3, HOXD13, and OTP demonstrated the strongest correlations with survival outcomes [13].

Single-cell RNA-seq analysis of 201,986 cells revealed distinct expression patterns for these prognostic genes in glioma subpopulations, particularly in oligoprogenitor cells, suggesting their potential role in glioma stem cell biology [13]. The enrichment analysis revealed that these prognostic genes were significantly associated with pathways related to synaptic signaling, embryonic development, and cell division, strengthening the hypothesis that synaptic integration plays a pivotal role in glioma development [13].

Diagram 2: GRN Dysregulation Leading to Disease Pathogenesis

Protocol: Identifying Disease-Associated Regulons Using RTN

Objective: Identify dysregulated regulons associated with disease progression and patient survival.

Materials and Reagents:

- Bulk RNA-seq data from patient cohorts (e.g., TCGA)

- Clinical annotation data (survival, grade, stage)

- R statistical environment with RTN package

- High-performance computing cluster

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Download and preprocess RNA-seq count data

- Annotate samples with clinical metadata

- Filter genes based on expression variance

- GRN Reconstruction with RTN:

- Run ARACNe algorithm to infer TF-target interactions

- Perform bootstrapping (recommended: 1000 iterations) for robustness

- Reconstruct regulons using mutual information threshold

- Regulon Activity Analysis:

- Calculate regulon activity scores using two-tailed GSEA

- Assign sample-specific regulon activity profiles

- Cluster samples based on regulon activity

- Survival Analysis:

- Perform univariate Cox regression for each regulon

- Apply LASSO regularization for multivariate analysis

- Identify regulons with significant survival association

- Validation and Functional Annotation:

- Validate findings in independent cohort

- Perform pathway enrichment on target genes

- Integrate with single-cell data for cellular resolution

Analysis Notes:

- Regularize for covariates such as age and tumor grade

- Use Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for multiple testing correction

- Consider network clusterization similarities in interpretation

Application Note 3: GRNs in Drug Response and Therapeutic Targeting

GRN analysis provides a powerful framework for understanding drug response mechanisms and identifying novel therapeutic targets. By mapping regulator activity rather than just gene expression, GRN models can reveal the master transcription factors driving pathological processes that may not be apparent from differential expression analysis alone. The directed nature of GRNs enables prediction of downstream effects from targeted interventions, supporting rational drug design and combination therapy strategies.

Protocol: Using GRNs to Predict Drug Response and Identify Targets

Objective: Leverage GRN analysis to predict drug response and identify master regulator TFs as potential therapeutic targets.

Materials and Reagents:

- Drug perturbation transcriptomic data (e.g., LINCS L1000)

- GRN model specific to disease context

- Compound annotation databases

- High-performance computing resources

Procedure:

- Baseline GRN Establishment:

- Reconstruct GRN from disease-relevant cell line or tissue

- Calculate baseline regulon activity using VIPER or similar algorithm

- Identify hyperactive and hypoactive regulons in disease state

- Drug Perturbation Analysis:

- Obtain transcriptomic profiles following drug treatment

- Map differential expression onto GRN structure

- Calculate drug-induced regulon activity changes

- Master Regulator Identification:

- Rank TFs by their regulatory influence on dysregulated pathways

- Prioritize TFs with high betweenness centrality in disease modules

- Validate essentiality using CRISPR screening data where available

- Drug Response Prediction:

- Correlate baseline regulon activity with drug sensitivity

- Build classifier using regulon profiles as features

- Validate predictions in independent datasets

- Combination Therapy Design:

- Identify complementary regulon targets

- Predict synergistic effects using network proximity

- Design sequential targeting strategies based on hierarchy

Validation Approaches:

- Compare predictions with high-throughput drug screening data

- Validate targets using CRISPR knockout in relevant models

- Correlate target expression with clinical response in trial data

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for GRN Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq Data | Profile gene expression at single-cell resolution | 10X Genomics, Smart-seq2 |

| scATAC-seq Data | Map chromatin accessibility at single-cell level | 10X Multiome, SNARE-seq |

| TF Motif Databases | Annotate potential TF-binding sites | JASPAR, CIS-BP |

| GRN Databases | Provide prior knowledge of regulatory interactions | RegNetwork 2025 [14] |

| Perturbation Data | Establish causal regulatory relationships | Perturb-seq, CRISP-seq |

| ChIP-seq Data | Validate TF-binding events ground truth | ENCODE, Cistrome |

| Bulk Reference Data | Provide external regulatory context | ENCODE, GTEx [7] |

| Software Packages | Implement GRN reconstruction algorithms | LINGER [7], GAEDGRN [9], RTN [13] |

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

The field of GRN research is rapidly evolving, with several emerging frontiers promising to enhance our understanding of gene regulation in development, disease, and drug response. The integration of multiomics data at single-cell resolution represents a particularly promising direction, with methods like PRISM-GRN demonstrating that incorporating scATAC-seq alongside scRNA-seq improves inference accuracy, especially for identifying causal relationships [12].

The application of lifelong learning approaches, as exemplified by LINGER, addresses the critical challenge of limited data by leveraging atlas-scale external resources [7]. This paradigm shift from learning each GRN de novo to building upon accumulated knowledge mirrors biological systems themselves and may dramatically accelerate our mapping of regulatory networks across diverse cellular contexts and disease states.

Another emerging frontier is the move toward dynamic GRN models that can capture regulatory changes over time during processes like differentiation, disease progression, or drug treatment response. While most current methods infer static networks, incorporating temporal information through methods like hypergraph representation learning (as in HyperG-VAE) may reveal how regulatory relationships rewire in response to internal and external cues [10].

Diagram 3: Emerging Frontiers in GRN Research and Clinical Translation

As GRN inference methods continue to improve in accuracy and scalability, their clinical translation holds particular promise for personalized medicine approaches. The ability to reconstruct patient-specific GRNs from biopsy material could inform targeted intervention strategies based on the specific regulatory architecture driving an individual's disease. Furthermore, GRN-based drug repurposing approaches may identify novel indications for existing compounds based on their regulon activity signatures rather than single target affinity.

The ongoing development of comprehensive regulatory databases like RegNetwork 2025, which now comprises 125,319 nodes and 11,107,799 regulatory interactions with enhanced reliability scoring, provides an essential foundation for these advances [14]. As these resources continue to expand and incorporate new regulatory elements including long noncoding RNAs and circular RNAs, they will further enhance our ability to reconstruct comprehensive GRNs relevant to development, disease, and therapeutic intervention.

The reconstruction of Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) is a fundamental challenge in systems biology, aiming to decipher the complex causal interactions between transcription factors (TFs) and their target genes [9]. GRNs underpin critical cellular processes, including development, cell differentiation, and disease pathogenesis [9] [2]. The advent of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized this field by providing high-resolution data, but it also introduces specific computational challenges and opportunities centered on three key biological concepts: sparsity, dynamics, and cell-type specificity.

Sparsity in scRNA-seq data manifests as an excess of zero counts, known as "dropout," where transcripts present in a cell are not detected by the sequencing technology [15]. This zero-inflation, affecting 57% to 92% of observed counts in some datasets, obscures true biological signals and complicates the inference of regulatory relationships [15]. Dynamics refer to the temporal changes in GRN architecture. Regulatory relationships are not static; they evolve with cell state, particularly during processes like differentiation and immune response [16]. Finally, cell-type specificity recognizes that GRNs are unique to cell identities and states. Bulk sequencing methods average signals across heterogeneous cell populations, thereby obscuring these specific networks, whereas scRNA-seq allows for their delineation [16] [2].

Understanding and addressing these three concepts is paramount for developing accurate GRN inference methods. This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for computational methodologies that effectively tackle sparsity, dynamics, and cell-type specificity to reconstruct biologically meaningful GRNs.

Application Notes: Methodological Foundations and Comparative Analysis

Methodological Approaches to Key Challenges

Computational methods for GRN inference employ diverse mathematical frameworks, each with distinct strengths in addressing the core challenges. The following table summarizes the primary methodological foundations and their applications.

Table 1: Methodological Foundations for GRN Inference

| Methodological Approach | Core Principle | Utility for Sparsity | Utility for Dynamics | Utility for Cell-Type Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation & Information Theory [2] | Measures association (e.g., Pearson correlation, mutual information) between gene expression levels. | Low; highly sensitive to false zeros. | Low; typically assumes steady-state. | Moderate; can be applied to clustered cell subsets. |

| Regression Models [2] | Models a target gene's expression as a function of potential regulator expressions. | Moderate; can be combined with regularizations to handle noise. | Low without modification. | High; can build separate models for each cell type or state. |

| Dynamical Systems [2] [16] | Uses differential equations or pseudo-temporal ordering to model gene expression changes over time. | Varies by implementation. | High; explicitly models temporal processes. | High; infers networks for specific trajectories or states. |

| Probabilistic Models [2] | Represents the GRN as a graphical model, estimating the probability of regulatory relationships. | Moderate; can model dropout as a probabilistic process. | Moderate; some frameworks incorporate time. | High; can incorporate cell-type labels. |

| Deep Learning [9] [2] [15] | Uses neural networks (e.g., GNNs, Autoencoders) to learn complex, non-linear relationships from data. | High; can be explicitly regularized against dropout (e.g., DAZZLE). | High; can integrate pseudo-time or use sequential models. | High; can learn cell-type-specific network embeddings. |

Comparative Analysis of State-of-the-Art Methods

Several recent methods have been developed with explicit considerations for sparsity, dynamics, and cell-type specificity. The table below benchmarks these tools based on their core innovations and performance.

Table 2: Comparison of Advanced GRN Inference Methods

| Method | Core Innovation | Handling of Sparsity | Handling of Dynamics | Handling of Cell-Type Specificity | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAEDGRN [9] | Gravity-inspired Graph Autoencoder (GIGAE) to capture directed network topology. | Random walk regularization to standardize latent vectors. | Not explicitly addressed; focuses on static network structure. | Uses a modified PageRank algorithm to prioritize important genes in specific contexts. | High accuracy and strong robustness on seven cell types across three GRN types. |

| inferCSN [16] | Sparse regression applied to cells ordered by pseudo-time and grouped into state-specific windows. | L0 and L2 regularization within the regression model. | High; uses pseudo-temporal ordering and sliding windows to model state-specific dynamics. | High; constructs networks for each cell state window defined by pseudo-time. | Outperforms other methods (GENIE3, SINCERITIES) on multiple performance metrics for both simulated and real data. |

| DAZZLE [15] | Dropout Augmentation (DA) to regularize models against zero-inflation. | High; augments data with synthetic dropout events to improve model robustness. | Not its primary focus; based on a static Structural Equation Model (SEM). | Can be applied to pre-clustered cell populations. | Improved performance and increased stability over baseline models like DeepSEM. |

| FigR [17] | Integrates scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data to link TFs to target genes via chromatin accessibility. | Leverages multi-omic data to add a prior that is less susceptible to expression noise. | Models are built for a defined cellular context. | High; infers context-specific networks by using paired data from the same cell. | Provides a framework for generating preliminary GRNs using multi-omic priors. |

Diagram 1: Conceptual workflow linking key biological concepts in scRNA-seq data to computational solutions and biological insights.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Reconstructing Dynamic GRNs using inferCSN

Principle: The inferCSN method infers cell state-specific GRNs by integrating pseudo-temporal ordering of cells with regularized sparse regression [16]. It addresses dynamics by dividing continuous pseudo-time into windows, thereby constructing a network for each cellular state and mitigating biases from uneven cell distribution.

Workflow Steps:

Input Data Preprocessing

- Input: A filtered scRNA-seq count matrix (cells x genes) with precomputed cell-type annotations.

- Gene Filtering: Filter genes to include those with variable expression across cells. It is recommended to include all known Transcription Factors (TFs) from a curated database (e.g., AnimalTFDB).

- Normalization: Normalize the count matrix using a standard method like library size normalization and log-transformation (e.g.,

log1p).

Pseudo-temporal Ordering and Windowing

- Trajectory Inference: Use a trajectory inference algorithm (e.g., Monocle 3, PAGA, or Slingshot) on the preprocessed data to compute a pseudo-time value for each cell. This orders cells along a hypothesized developmental or differentiation trajectory.

- Cell Windowing: Divide the ordered cells into multiple overlapping or non-overlapping windows based on their pseudo-time values. The number of cells per window should be sufficient for stable regression. This step ensures that the inferred network is specific to the cell state captured within that window.

GRN Inference via Sparse Regression

- Model Framework: For each window

w, letE_wbe the gene expression matrix. For each target geneg_i, solve the following sparse regression problem:E_w(:, g_i) = Σ_{j≠i} β_{ij} * E_w(:, g_j) + εwhereβ_{ij}represents the potential regulatory influence of geneg_jong_i, andεis the error term. - Regularization: Apply L0 and/or L2 regularization to the coefficients

β_{ij}to promote sparsity and prevent overfitting. The L0 penalty controls the number of non-zero regulators, while the L2 penalty handles multicollinearity. - Reference Network Calibration (Optional): Use a prior reference network (e.g., from a public database) to calibrate the inferred coefficients and remove likely false positives.

- Model Framework: For each window

Output and Integration

- Output: inferCSN produces a set of GRNs, one for each window, representing the dynamic changes in gene regulation along the pseudo-temporal trajectory.

- Analysis: Compare networks across windows to identify regulatory relationships that are gained or lost, highlighting key transitions in cell state.

Diagram 2: Flowchart of the inferCSN protocol for reconstructing dynamic GRNs.

Protocol 2: Handling Data Sparsity with DAZZLE

Principle: DAZZLE tackles the challenge of data sparsity (dropout) not by imputing missing values, but by augmenting the training data with additional synthetic dropout events. This regularization technique, called Dropout Augmentation (DA), forces the model to become robust to zeros, preventing overfitting and improving the stability of the inferred GRN [15].

Workflow Steps:

Input Data Preparation

- Input: A normalized scRNA-seq expression matrix

Xof dimensions (m cells × n genes). - Transformation: Transform the input counts using

log1pto reduce variance and avoid taking the log of zero.

- Input: A normalized scRNA-seq expression matrix

Dropout Augmentation (DA)

- Synthetic Zero Injection: For each training epoch, create an augmented copy of the input matrix

X_aug. Randomly select a small percentage (e.g., 5-10%) of the non-zero entries inX_augand set them to zero. This simulates additional, realistic dropout events.

- Synthetic Zero Injection: For each training epoch, create an augmented copy of the input matrix

Model Training with Structural Equation Model (SEM)

- Model Architecture: DAZZLE uses a variational autoencoder (VAE) framework where the gene-gene interaction network is represented by a learnable adjacency matrix

A. - Encoder: The encoder

gtakes the augmented dataX_augand produces a latent representationZ.Z = g(X_aug) - Decoder: The decoder

fuses the latent representationZand the adjacency matrixAto reconstruct the original inputX.X_recon = f(A, Z) - Loss Function: The model is trained to minimize the reconstruction error between

X_reconand the originalX, while simultaneously applying sparsity constraints on the adjacency matrixAto prevent a fully connected network.

- Model Architecture: DAZZLE uses a variational autoencoder (VAE) framework where the gene-gene interaction network is represented by a learnable adjacency matrix

GRN Extraction

- After training, the non-zero entries in the learned adjacency matrix

Aconstitute the inferred GRN. The sign and magnitude of the values indicate the direction and strength of the regulatory relationships.

- After training, the non-zero entries in the learned adjacency matrix

Protocol 3: Integrating Multi-omic Data for Specificity with FigR

Principle: FigR enhances cell-type-specific GRN inference by leveraging paired scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data from the same cells [17]. It uses chromatin accessibility to constrain and inform potential regulatory interactions, thereby adding a biologically meaningful prior that improves specificity.

Workflow Steps:

Input Data Preprocessing

- Inputs:

- scRNA-seq Data: A normalized gene expression matrix.

- scATAC-seq Data: A peak accessibility matrix.

- Feature Selection: For RNA, select all TFs and a subset of highly variable non-TF genes. For ATAC, select peaks based on variability (e.g., coefficient of variation).

- Inputs:

Topic Modeling with cisTopic

- Run cisTopic: Apply Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) via

cisTopicto the scATAC-seq data to reduce dimensionality and define "topics" representing recurrent patterns of chromatin accessibility. - Extract Matrix: Obtain the cell-by-topic probability matrix from the selected

cisTopicmodel.

- Run cisTopic: Apply Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) via

Peak-Gene Correlation and TF Motif Mapping

- k-NN Graph: Calculate a k-nearest neighbor (k-NN) graph among cells using the

cisTopictopic matrix to define cellular neighborhoods. - Correlation Calculation: Correlate the accessibility of each peak with the expression of every gene within its genomic neighborhood (e.g., within 200 kb) across the defined cellular neighborhoods.

- TF Mapping: Use

ChromVARor a similar tool to annotate peaks with known Transcription Factor binding motifs.

- k-NN Graph: Calculate a k-nearest neighbor (k-NN) graph among cells using the

GRN Inference in FigR

- Input to FigR: The correlated peak-gene links and the TF-motif annotations are used to define candidate TF-to-Gene interactions.

- Regression Model: FigR fits a regularized regression model to score these candidate interactions based on the correlation strength and the expression levels of the TF and its target gene, ultimately outputting a cell-type-specific GRN.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for GRN Reconstruction

| Category | Item/Resource | Function/Description | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data | scRNA-seq Dataset | Primary input data providing gene expression measurements at single-cell resolution. | 10X Genomics Chromium; SHARE-seq [2]. |

| TF Database | A curated list of transcription factors for a given organism, used to define potential regulators. | AnimalTFDB; allTFs_hg38.txt [17]. | |

| Prior Network Database | Known molecular interactions from literature and databases for network calibration. | STRING; DoRothEA; prior information used in inferCSN [16]. | |

| Software & Algorithms | Trajectory Inference Tool | Computes pseudo-temporal ordering of cells for dynamic GRN analysis. | Monocle 3, Slingshot (used by inferCSN) [16]. |

| Motif Analysis Tool | Annotates accessible chromatin regions with potential TF binders. | ChromVAR (used by FigR) [17]. | |

| Topic Modeling Package | Identifies patterns in scATAC-seq data to reduce dimensionality. | cisTopic (used by FigR) [17]. | |

| Computational Environment | High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Server with multiple CPU cores and large RAM for computationally intensive model training. | Server with 16+ CPU cores, 128GB RAM (used for benchmarking) [16]. |

| Cox-2-IN-16 | Cox-2-IN-16, MF:C19H12BrN3O2, MW:394.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| c-Met-IN-14 | c-Met-IN-14|c-Met Kinase Inhibitor|Research Compound | Bench Chemicals |

Diagram 3: Tool and data integration process for multi-omic GRN reconstruction.

The reconstruction of Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) is a fundamental challenge in biology, aiming to unravel the complex causal relationships between genes and their regulators, such as transcription factors (TFs). GRNs govern critical cellular processes including development, cell identity, and disease progression [2] [1]. The accuracy and resolution of GRN inference are intrinsically linked to the evolution of sequencing technologies. This journey has progressed from bulk transcriptomics to the current era of single-cell multi-omics, each step providing a more nuanced and comprehensive view of regulatory mechanisms [2] [18].

Early computational GRN inference methods relied on data from microarrays and bulk RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq), which measured average RNA expression from populations of cells. These methods identified co-expressed genes using correlation or mutual information but were unable to incorporate crucial epigenetic information about regulatory binding sites [2]. The expansion to bulk multi-omics—such as ATAC-seq for chromatin accessibility, ChIP-seq for TF binding, and Hi-C for chromatin conformation—provided mechanistic insights into regulatory relationships but still lacked the resolution to capture cell-to-cell heterogeneity [2].

The advent of single-cell omics technologies has revolutionized the field by enabling the profiling of molecular features at the single-cell level. Techniques like single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) and single-cell ATAC-seq (scATAC-seq) revealed cellular heterogeneity and led to a new generation of computational methods [2]. The latest frontier is single-cell multi-omics, where technologies such as SHARE-seq and 10x Multiome simultaneously profile multiple modalities—like RNA and chromatin accessibility—from the same single cell [2] [19]. This progression, from bulk to single-cell to multi-modal single-cell data, provides the foundational layers upon which modern, powerful GRN inference methods are built.

Methodological Foundations for GRN Inference

GRN inference relies on diverse statistical and algorithmic principles to uncover regulatory connections. The following table summarizes the core methodological approaches employed by modern computational tools.

Table 1: Core Methodological Foundations for GRN Inference

| Methodological Approach | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Common Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-Based [2] | Measures association (e.g., Pearson's correlation, mutual information) between regulator and target gene expression. | Simple, intuitive; effective for identifying co-expressed genes. | Cannot distinguish directionality; confounded by indirect relationships. |

| Regression Models [2] | Models gene expression as a function of multiple potential regulators (TFs/CREs). | Infers direction and strength of effect; provides interpretable coefficients. | Can be unstable with correlated predictors; prone to overfitting. |

| Probabilistic Models [2] | Uses graphical models to capture dependence between variables, estimating the probability of regulatory relationships. | Allows for filtering and prioritization of interactions. | Often assumes specific data distributions (e.g., Gaussian) which may not hold. |

| Dynamical Systems [2] | Models gene expression as a system evolving over time using differential equations. | Captures diverse factors affecting expression; highly interpretable parameters. | Less scalable to large networks; dependent on prior knowledge and time-series data. |

| Deep Learning [2] [1] | Employs versatile neural network architectures (e.g., autoencoders, graph neural networks) to learn complex regulatory patterns. | Can model complex, non-linear relationships; highly flexible. | Requires large datasets; computationally intensive; can be less interpretable. |

The shift to single-cell multi-omics data has been accompanied by a transition from classical machine learning to more advanced deep learning techniques. Modern methods can be broadly categorized by their learning paradigm, as shown in the table below, which lists representative algorithms.

Table 2: Representative Machine Learning Methods for GRN Inference from Single-Cell Data

| Algorithm Name | Learning Type | Deep Learning | Key Technology | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GENIE3 [1] | Supervised | No | Random Forest | 2010 |

| DeepSEM [1] | Supervised | Yes | Deep Structural Equation Modeling | 2023 |

| STGRNs [1] | Supervised | Yes | Transformer | 2023 |

| GRNFormer [1] | Supervised | Yes | Graph Transformer | 2025 |

| ARACNE [1] | Unsupervised | No | Information Theory (Mutual Information) | 2006 |

| GRN-VAE [1] | Unsupervised | Yes | Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | 2020 |

| GCLink [1] | Contrastive | Yes | Graph Contrastive Link Prediction | 2025 |

| scGPT [19] | Foundation Model | Yes | Generative Pretrained Transformer | 2024 |

A significant recent trend is the emergence of foundation models for single-cell omics [19]. These large, pretrained neural networks, such as scGPT and scPlantFormer, are trained on millions of cells and demonstrate exceptional capabilities in zero-shot cell type annotation, in silico perturbation modeling, and GRN inference. Unlike single-task models, these frameworks use self-supervised pretraining to capture universal hierarchical biological patterns, representing a paradigm shift towards scalable and generalizable GRN analysis [19].

Advanced Protocols for GRN Reconstruction

Protocol 1: Inference of Combinatorial Regulatory Modules with cRegulon

The cRegulon method moves beyond single-TF analysis to infer reusable regulatory modules where multiple TFs act in combination, providing fundamental units that underpin cell type identity [20].

Experimental Workflow:

- Input Data Preparation: Collect single-cell multi-omics data, specifically paired scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data, from the cell populations of interest. The data can be paired at the cell level or the context level (e.g., same cell type or condition).

- Preprocessing and Clustering: Perform standard quality control, normalization, and dimensionality reduction on the scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data. Cluster cells to identify putative cell types or states.

- Initial GRN Construction: For each cell cluster, reconstruct a cluster-specific GRN using a suitable inference method. This network will connect TFs, regulatory elements (REs), and target genes (TGs).

- Compute Combinatorial Effect Matrix: For each cluster-specific GRN, calculate a pairwise combinatorial effect for all TF pairs. This effect combines the co-regulation strength and activity specificity of the TF pair.

- Identify TF Modules via Optimization: Model the combinatorial effect matrix as a mixture of rank-1 matrices, each corresponding to a module of co-regulating TFs. Solve the optimization model (Eq. 2 in [20]) to identify these TF modules across all cell clusters.

- Construct cRegulons: For each identified TF module, assemble the corresponding set of binding REs and co-regulated TGs to form a complete cRegulon.

- Cell Type Annotation: Annotate each cell type (biologically well-annotated cluster) based on the activity and composition of the cRegulons it utilizes.

Diagram 1: cRegulon analysis workflow.

Protocol 2: Multi-Omic Data Integration with scMODAL

The scMODAL framework provides a robust deep-learning solution for integrating diverse single-cell omics modalities, a critical step before downstream GRN analysis, especially when known feature links are limited [21].

Experimental Workflow:

- Input Data and Linked Features: Prepare two unpaired cell-by-feature matrices, ( \mathbf{X}1 ) and ( \mathbf{X}2 ), from different modalities (e.g., scRNA-seq and single-cell proteomics). Compile a limited set of ( s ) known positively correlated feature pairs (e.g., a protein and its coding gene) into matrices ( \widetilde{\mathbf{X}}1 ) and ( \widetilde{\mathbf{X}}2 ).

- Neural Network Training: Train two modality-specific encoder networks (( E1 ), ( E2 )) to map the full feature matrices ( \mathbf{X}1 ) and ( \mathbf{X}2 ) into a shared latent space ( Z ). Simultaneously, train decoder networks (( G1 ), ( G2 )) for autoencoding consistency.

- Adversarial Alignment: Employ a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) with a discriminator to minimize the distribution divergence between the two datasets in the latent space ( Z ), effectively removing unwanted technical variation.

- MNN Anchor Guidance: During training, use the linked features (( \widetilde{\mathbf{X}}1 ), ( \widetilde{\mathbf{X}}2 )) to identify Mutual Nearest Neighbor (MNN) pairs between minibatches of cells. Apply an L2 penalty to keep the embeddings of these anchor pairs close, guiding correct biological alignment.

- Geometric Structure Preservation: For each cell in a minibatch, calculate its Gaussian kernel similarity to other cells. Encourage the encoders to preserve these geometric representations to prevent over-correction and loss of population structure.

- Downstream Analysis: Use the aligned latent representations ( Z ) for unified clustering and visualization. Utilize the cross-modality mapping networks ( E1(G2( \cdot )) ) and ( E2(G1( \cdot )) ) for feature imputation and inference of cross-modal regulatory relationships.

Diagram 2: scMODAL integration architecture.

Successful execution of modern GRN inference studies requires a combination of wet-lab reagents and dry-lab computational resources.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell Multi-omics

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example Technologies / Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Multi-ome Kit | Enables simultaneous profiling of gene expression and chromatin accessibility from the same single cell. | 10x Genomics Multiome (ATAC + Gene Expression), SHARE-seq [2] |

| CITE-seq Antibodies | Allows for integrated quantification of surface protein abundance alongside transcriptome in single cells. | BioLegend TotalSeq Antibodies [21] |

| Nuclei Isolation Kit | Prepares high-quality, intact nuclei from fresh or frozen tissue for scATAC-seq and other epigenomic assays. | Chromium Nuclei Isolation Kit (10x Genomics) [20] |

| Library Preparation Kit | Prepares sequencing libraries from the amplified cDNA or DNA from single-cell assays. | Illumina DNA/RNA Prep Kits [18] |

| Cell Hash Tagging | Enables sample multiplexing by labeling cells from different samples with distinct barcoded antibodies, reducing batch effects and cost. | BioLegend CellPlex [21] |

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools and Datasets for GRN Inference

| Resource Name | Type | Function / Utility |

|---|---|---|

| scGPT [19] | Foundation Model | A generative pretrained transformer for tasks like cell type annotation, multi-omic integration, and GRN inference. |

| DISCO / CZ CELLxGENE [19] | Data Repository | Federated platforms aggregating over 100 million single cells for query and analysis. |

| BioLLM [19] | Benchmarking Framework | A universal interface for integrating and benchmarking over 15 single-cell foundation models. |

| GRN-VAE [1] | Inference Algorithm | A variational autoencoder-based method for inferring GRNs from single-cell data. |

| cRegulon [20] | Inference Algorithm | A method to infer combinatorial TF regulatory modules from single-cell multi-omics data. |

| scMODAL [21] | Integration Tool | A deep learning framework for aligning single-cell multi-omics data with limited feature links. |

A Toolkit for Discovery: Categorizing Modern GRN Inference Methods and Their Applications

Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) are complex systems that represent the intricate interactions between genes, transcription factors (TFs), and other regulatory molecules, controlling gene expression in response to environmental and developmental cues [1] [22]. The reconstruction of accurate GRNs is fundamental to systems biology, with applications in developmental biology, cancer research, and personalized medicine [1]. Among the computational methods developed for GRN inference, regression-based models have emerged as powerful tools for identifying direct regulatory relationships from gene expression data. These techniques formulate GRN inference as a series of regression problems where the expression level of each target gene is predicted based on the expression levels of potential regulator genes [1] [23].

Regression-based approaches are particularly valuable because they can identify causal relationships and handle the high-dimensional nature of genomic data where the number of genes (p) often far exceeds the number of samples (n). Regularization methods such as LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator), Ridge regression, and compressive sensing have proven effective in addressing this "curse of dimensionality" by imposing constraints on the model parameters [23] [24] [25]. These techniques leverage the biological insight that GRNs are inherently sparse, meaning each gene is regulated by only a small subset of all possible regulators [25].

This application note provides a comprehensive overview of these regression-based models, their implementation protocols, and applications in GRN reconstruction, serving as a practical guide for researchers and scientists engaged in computational biology and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations

LASSO Regression

LASSO regression incorporates an L1-norm penalty term that shrinks some regression coefficients to exactly zero, effectively performing variable selection [24]. For GRN inference, this is formulated as minimizing the following objective function:

∑(yi−y^i)2+λΣ|βj|

where yi are actual values, ŷi are predicted values, λ is the regularization parameter controlling the strength of the penalty, and β_j are the regression coefficients [24]. The sparsity-inducing property of LASSO makes it biologically interpretable for GRN inference, as it identifies a small set of candidate regulators for each target gene.

Ridge Regression

Ridge regression employs an L2-norm penalty that shrinks coefficients toward zero without setting them to exactly zero, effectively handling multicollinearity in gene expression data [24]. The objective function for Ridge regression is:

∑(yi−y^i)2+λΣβj2

This approach is particularly useful for datasets with high correlation between transcription factors, as it provides more stable coefficient estimates than standard linear regression [24].

Compressive Sensing

Compressive sensing is a signal processing technique that enables exact reconstruction of sparse signals from relatively few measurements [25]. In the context of GRN inference, the problem is formulated as:

Y = Ωq

where Y represents the measurement (gene expression data), Ω is the sensing matrix, and q is the sparse signal (GRN structure) to be reconstructed [25]. The method relies on the incoherence condition of the sensing matrix and can guarantee exact recovery of the network structure under suitable conditions.

Advanced Hybrid Formulations

Recent advancements have led to hybrid formulations that integrate multiple regularization techniques. The fused LASSO approach incorporates both sparsity and similarity constraints, making it particularly suitable for analyzing multiple datasets from different perturbation experiments [23]. Similarly, the Weighted Overlapping Group Lasso (wOGL) combines network-based regularization with group lasso to utilize prior network knowledge while performing selection of gene sets containing differentially expressed genes [26].

Comparative Analysis of Methods

Table 1: Comparative characteristics of regression-based GRN inference methods

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LASSO | L1-norm penalty; sparsity induction | Variable selection; biologically interpretable | May select only one from correlated features | Bulk RNA-seq analysis; TF-target identification [24] |

| Ridge | L2-norm penalty; coefficient shrinkage | Handles multicollinearity; stable estimates | No variable selection; all features retained | Preprocessing for dimension reduction; multicollinearity-rich datasets [24] |

| Fused LASSO | Combines L1-norm and fusion penalty | Integrates multiple datasets; captures similar networks | Computationally intensive | Time-series data from multiple perturbations [23] |

| Compressive Sensing | Exploits signal sparsity; requires incoherence condition | Theoretical recovery guarantees; minimal measurements | Sensitive to measurement noise and hidden nodes | Network reconstruction from limited time-series data [25] |

| Weighted Overlapping Group Lasso | Integrates network-based regularization with group lasso | Utilizes prior knowledge; captures sparse signals | Requires prior network information | Pathway analysis; integration with existing biological knowledge [26] |

| AcrB-IN-1 | AcrB-IN-1, MF:C32H39N3O4, MW:529.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| Egfr-IN-53 | Egfr-IN-53, MF:C14H13N3O2S, MW:287.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Table 2: Performance characteristics of regression-based methods on different data types

| Method | Bulk RNA-seq | Single-cell RNA-seq | Time-series Data | Multi-omics Integration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LASSO | High accuracy [24] | Moderate (due to noise) | Limited | Possible with extension |

| Ridge | Good for correlated features [24] | Moderate | Limited | Possible with extension |

| Fused LASSO | Good for multiple datasets [23] | Not specifically designed | Excellent [23] | Limited |

| Compressive Sensing | Good with limited samples [25] | Challenging | Excellent [25] | Limited |

| Elastic Net | Combines LASSO and Ridge advantages | Adaptable with modifications | Good | Promising |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: GRN Inference Using LASSO Regression

Application Notes: This protocol details the implementation of LASSO regression for GRN inference from bulk RNA-seq data, suitable for identifying regulator-target relationships in steady-state conditions.

Materials and Reagents:

- Normalized gene expression matrix (genes × samples)

- List of transcription factors

- Computational environment (R/Python with necessary packages)

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Normalize raw read counts using TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) or similar method [4]

- Log-transform expression values if necessary

- Optional: Filter lowly expressed genes

Problem Formulation:

- For each target gene, define a regression problem where the target gene's expression is the response variable

- Potential regulators (TFs) serve as predictors

- Standardize all variables to mean zero and unit variance

Model Implementation:

- Apply LASSO regression for each target gene:

- Use k-fold cross-validation (typically 5- or 10-fold) to select the optimal λ value

- Repeat for all genes in the dataset

Network Construction:

- Extract non-zero coefficients from all regression models

- Construct adjacency matrix where edges represent regulator-target relationships

- Apply false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple testing

Validation:

- Compare with known regulatory interactions from databases

- Use functional enrichment analysis to assess biological relevance

Troubleshooting:

- If too many edges are detected, increase λ value or apply stricter FDR correction

- If no edges are detected, check for low expression variance and consider reducing λ

Protocol 2: GRN Inference Using Compressive Sensing

Application Notes: This protocol implements compressive sensing for GRN reconstruction from limited time-series data, leveraging network sparsity for exact recovery.

Materials and Reagents:

- Time-series gene expression data (genes × time points)

- Potential basis functions for representing dynamics

- Computational environment with convex optimization tools

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Collect time-series measurements of gene expression

- Ensure temporal resolution captures dynamics of interest

- Handle missing values through appropriate imputation

Sensing Matrix Construction:

- Design sensing matrix Ω that captures temporal relationships

- Include candidate basis functions that represent possible regulatory dynamics

- Validate incoherence condition for exact recovery guarantees [25]

Sparse Recovery:

- Solve the optimization problem using L1-minimization:

- Use linear programming or specialized compressive sensing algorithms

- For noisy data, use basis pursuit denoising formulation

Network Reconstruction:

- Extract non-zero elements from solution vector q

- Map these elements to specific regulator-target interactions

- Apply thresholding based on coefficient magnitudes

Experimental Design Guidance:

- Use coherence distribution to identify insufficiently constrained interactions

- Design additional experiments targeting high-coherence regions [25]

Troubleshooting:

- If recovery is poor, check coherence of sensing matrix and consider additional time points

- For noisy data, increase regularization parameter or use robust formulations

Protocol 3: Integrated Multi-Study Analysis Using Fused LASSO

Application Notes: This protocol enables the integration of multiple perturbation experiments using fused LASSO, particularly useful for identifying consistent regulatory interactions across conditions.

Materials and Reagents:

- Multiple gene expression datasets from different perturbations

- Corresponding control datasets

- Computational environment with optimization tools supporting fused LASSO

Procedure:

- Data Integration:

- Collect k gene expression datasets (X¹, X², ..., Xáµ) from different conditions

- Include corresponding reference control datasets (Xᶜ¹, Xᶜ², ..., Xᶜáµ)

- Normalize all datasets to comparable scales [23]

Weight Matrix Calculation:

- Compute differential behavior between perturbation and control datasets

- Construct weight matrices representing similarity in differential expression profiles

Fused LASSO Implementation:

- Implement the fused LASSO objective function [23]:

- Tune parameters λ₠and λ₂ using cross-validation

- Solve the optimization problem using coordinate descent

Network Integration:

- Extract consistent interactions across multiple datasets

- Identify condition-specific regulatory relationships

- Construct consensus network representing core regulatory structure

Biological Validation:

- Compare with known condition-specific responses

- Validate novel predictions using experimental data from literature

Troubleshooting:

- If networks are too similar, reduce λ₂ to allow more condition-specificity

- If networks are too divergent, increase λ₂ to enforce similarity

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Workflow for regression-based GRN inference. This diagram illustrates the comprehensive process for reconstructing gene regulatory networks using regression-based methods, from data preprocessing to biological interpretation, including decision points for method selection based on data characteristics.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for regression-based GRN inference

| Category | Item | Specifications | Application/Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | RNA-seq Data | Bulk or single-cell; minimum 3 replicates per condition | Primary input for inferring regulatory relationships [24] |

| Transcription Factor Database | PlantTFDB, AnimalTFDB; comprehensive TF lists | Identification of potential regulator genes [4] | |

| Prior Knowledge Networks | REGULATOR, STRING; known interactions | Integration for improved prediction [26] | |

| Computational Tools | LASSO Implementation | GLMNET, Scikit-learn; efficient regularization | Sparse regression for variable selection [24] |

| Compressive Sensing Tools | SPGL1, CVX; convex optimization | Sparse signal recovery [25] | |

| Network Visualization | Cytoscape, Gephi; graph layout algorithms | Visualization and analysis of inferred networks | |

| Validation Resources | Gold Standard Networks | RegulonDB, DREAM challenges; validated interactions | Benchmarking method performance [1] |

| Functional Annotation | GO, KEGG; pathway information | Biological validation of inferred networks | |