Protein-Protein Interaction Network Analysis: From Fundamentals to AI-Driven Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis, a critical discipline for understanding cellular function and disease mechanisms.

Protein-Protein Interaction Network Analysis: From Fundamentals to AI-Driven Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis, a critical discipline for understanding cellular function and disease mechanisms. It covers foundational concepts of the interactome and network topology, explores cutting-edge experimental and computational methodologies—including deep learning and large language models—and addresses key challenges in data validation and standardization. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, the content synthesizes current best practices and future directions, highlighting how PPI network insights are directly translating into novel therapeutic strategies for complex diseases like cancer and autoimmune disorders.

Understanding the Interactome: Core Concepts and Network Topology of PPIs

The cellular machinery is governed by a complex web of protein-protein interactions (PPIs) that regulate virtually all biological functions. These interactions form intricate networks, often called the interactome, which provide a systems-level view of cellular organization and dynamics. In these networks, proteins are represented as nodes, and the physical or functional interactions between them are represented as edges [1]. The analysis of PPIs has been revolutionized by the work of Barabási and Oltvai, who demonstrated that cellular networks are governed by universal laws and exhibit key properties such as scale-free topology, small-world properties, and modularity [1].

Protein interaction networks can be categorized into several distinct types based on the nature of the relationships they represent. Binary interaction networks map direct physical interactions between two proteins, typically derived from yeast two-hybrid screens. Co-complex interaction networks represent proteins that are part of the same stable macromolecular complex, usually identified through affinity purification coupled with mass spectrometry (AP-MS). Functional interaction networks encompass both physical and functional associations, incorporating diverse data sources including genetic interactions, co-expression patterns, and shared phylogenetic profiles [2]. Understanding these different network types is crucial for designing appropriate experimental and computational approaches to define the interactome, from stable complexes to transient interactions.

Table 1: Key Properties of Protein-Protein Interaction Networks

| Property | Description | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Scale-free topology | Network connectivity follows a power-law distribution with few highly connected hubs | Biological robustness; mutations in most nodes have limited impact, while hub disruptions can be lethal |

| Small-world properties | Short average path lengths between any two nodes with high clustering | Efficient information and signal propagation within the cell |

| Modularity | Densely connected groups of nodes that form functional units | Corresponds to protein complexes, pathways, and functional modules |

| Hub proteins | Nodes with exceptionally high connectivity | Often essential proteins or key regulatory elements in cellular processes |

Computational Methods for Interactome Mapping

Genomic Context Methods

Computational methods for predicting PPIs can be classified into three main categories: genomic context methods, machine learning algorithms, and text mining approaches [1]. Genomic context methods leverage the structure and organization of genomic data to infer functional relationships between proteins. These methods include domain fusion analysis (which identifies fused homologs of separate proteins in other species), conserved gene neighborhood (which examines the proximity of genes across multiple genomes), and phylogenetic profiles (which compare the presence or absence of genes across different organisms) [1]. The primary advantage of genomic context methods is their ability to perform interspecies comparisons with relatively limited computational resources, enabling rapid calculation of potential interactions. However, these methods typically have lower coverage rates and rely exclusively on genomic features without incorporating experimental validation [1].

The domain fusion method, also known as the "Rosetta stone" method, represents a significant milestone in computational PPI prediction. Developed by Eisenberg and colleagues, this approach was the first computational method to predict PPIs from the genomes of distinct species based on polypeptide analysis [1]. The fundamental premise is that if two separate proteins in one species appear as a single fused protein in another species, the original proteins are likely functionally linked or physically interacting. This method assumes that protein pairs may have evolved from ancestral proteins with interaction domains on the same polypeptide chain [1]. Subsequent improvements incorporated eukaryotic gene sequences, increasing the robustness of predictions due to the larger volume of sequence data available in eukaryotes.

Machine Learning and Text Mining Approaches

Machine learning algorithms represent a powerful approach for PPI prediction, capable of handling multi-dimensional and multi-variety data with high efficiency. Supervised learning methods commonly applied to PPI prediction include support vector machines (SVMs), artificial neural networks, naïve Bayes classifiers, and decision trees [1]. Unsupervised learning methods such as K-means clustering and hierarchical clustering are also employed to identify patterns and groupings in protein interaction data. The main challenge with machine learning approaches is the requirement for massive, high-quality datasets for training, and these methods can be susceptible to errors if training data contains biases or inaccuracies. Additionally, significant computational resources are often required for complex model training and optimization [1].

Text mining approaches extract information about protein interactions from scientific literature and reference databases such as PubMed using natural language processing (NLP) technologies [1]. The major advantage of text mining is the vast amount of information available in published articles, allowing for rapid, inexpensive, and accessible data collection. However, this method is limited to interactions that have been explicitly described in the literature and may miss novel or unreported interactions. Additionally, NLP approaches must contend with the complexity and inconsistency of scientific language and terminology [1]. Increasingly, researchers are combining these computational approaches - for instance, integrating text mining algorithms with machine learning methods - to capture more biologically significant relationships between proteins and improve prediction accuracy [1].

Table 2: Computational Methods for Protein-Protein Interaction Prediction

| Method | Main Advantage | Main Disadvantage | Example Databases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic context | Interspecies comparison with few computational resources; fast calculation | Low coverage rate; prediction using only genomic features | STRING, BioGRID, Hippie, IntAct, HPRD [1] |

| Machine learning algorithm | Handles multi-dimensional data with high efficiency | Requires massive datasets and significant IT resources; high error susceptibility | STRING, BioGRID, IID, Hitpredict [1] |

| Text mining | Many publications available; rapid execution; inexpensive | Limited to interactions cited in articles | STRING, BioGRID, MINT, IntAct, HPRD [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Interactome Mapping

Binary Interaction Mapping via Yeast Two-Hybrid

The yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) system is a powerful molecular biology technique used to detect binary protein-protein interactions through the reconstitution of transcription factor activity in yeast. The protocol involves fusing a "bait" protein to a DNA-binding domain and a "prey" protein to an activation domain. If the bait and prey proteins interact, the DNA-binding and activation domains are brought into proximity, activating reporter gene expression.

Protocol Steps:

- Clone bait gene into vector containing DNA-binding domain (e.g., GAL4-BD)

- Clone prey gene into vector containing activation domain (e.g., GAL4-AD)

- Co-transform both plasmids into appropriate yeast reporter strain

- Plate transformations on selective media lacking specific nutrients to select for plasmid maintenance

- Assay for reporter gene activation by assessing growth on selective media or colorimetric assays

- Confirm interactions through multiple reporter genes to minimize false positives

- Sequence verification of interacting clones to identify specific interacting partners

The Y2H system is particularly valuable for mapping large-scale interactomes due to its relatively high throughput capacity and ability to detect direct binary interactions. However, it may produce false positives from nonspecific interactions or false negatives from incomplete library representation or interactions that don't occur in the yeast nucleus. Recent adaptations include the use of next-generation sequencing to read out Y2H results, dramatically increasing throughput.

Co-Complex Interaction Mapping via Affinity Purification Mass Spectrometry

Affinity purification coupled with mass spectrometry (AP-MS) identifies proteins that exist in the same stable complex through immunoprecipitation of a tagged bait protein followed by mass spectrometric identification of co-purifying proteins. This protocol is particularly useful for characterizing stable protein complexes and their composition under different physiological conditions.

Protocol Steps:

- Design and clone tagged bait protein with an appropriate affinity tag (e.g., FLAG, HA, TAP)

- Express tagged bait in appropriate cell system (mammalian, yeast, bacterial)

- Cell lysis using mild non-denaturing conditions to preserve protein complexes

- Affinity purification of bait protein and associated complexes using tag-specific antibodies or resins

- Stringent washing to remove non-specifically bound proteins

- Elution of protein complexes using competitive elution (e.g., FLAG peptide) or mild denaturation

- Trypsin digestion of eluted proteins into peptides

- Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis

- Bioinformatic analysis to identify specific interactors versus background contaminants

AP-MS data should be processed using statistical frameworks that distinguish specific interactors from nonspecific background binders. Tools like SAINT (Significance Analysis of INTeractome) employ probabilistic models to assign confidence scores to identified interactions based on spectral counts and control purifications. The resulting networks represent co-complex memberships rather than direct binary interactions, which is an important distinction when integrating data from different experimental approaches.

Network Analysis and Visualization Protocols

Network Construction and Centrality Analysis

Protein interaction data from experimental and computational sources can be integrated and analyzed using network analysis libraries such as NetworkX in Python. The following protocol outlines the steps for constructing a PPI network and calculating key centrality measures to identify important nodes.

Protocol Steps:

- Data Acquisition: Download PPI data from databases such as STRING, BioGRID, or IntAct in standard formats like TSV or CSV. These databases collectively contain millions of non-redundant interactions curated from both experimental and computational sources [3] [1].

- Network Construction: Import the interaction data into Python using NetworkX. The typical approach involves creating a graph object and adding edges from a pandas DataFrame containing source and target protein identifiers.

- Centrality Calculation: Compute key centrality measures to identify important nodes within the network. Degree centrality identifies highly connected hubs, betweenness centrality reveals bottleneck proteins that connect network modules, and closeness centrality indicates proteins that can quickly interact with many others.

Hub Identification: Identify hub proteins by selecting nodes in the top 5% of degree distribution. In scale-free networks like most PPI networks, hubs typically have essential cellular functions and may represent potential drug targets [4] [2].

Network Visualization: Create informative visualizations using force-directed layouts that position connected nodes closer together, facilitating the identification of network modules and communities.

- Functional Analysis: Perform Gene Ontology and pathway enrichment analysis on hub proteins and network modules to identify biological processes and pathways that are overrepresented in the network.

Advanced Network Analysis: Filtering and Subnetwork Extraction

Raw PPI networks often contain false positives and can be excessively dense, making meaningful analysis challenging. This protocol describes advanced techniques for network filtering and subnetwork extraction to improve biological interpretability.

Protocol Steps:

- Confidence Filtering: Apply confidence thresholds to interactions based on experimental evidence or computational prediction scores. STRING database provides combined confidence scores that integrate evidence from multiple sources, with scores > 0.7 generally indicating high-confidence interactions [5] [1].

Topology Filtering: Remove nodes with very low connectivity (degree ≤ 2) that may represent false positives or biologically insignificant interactions. Alternatively, focus analysis on the giant connected component of the network, which typically contains the most biologically relevant interactions.

Ego Network Extraction: Create subnetworks centered on specific proteins of interest (seeds) by including all proteins connected within a defined distance (typically 1-2 steps). Ego networks facilitate detailed analysis of local interaction neighborhoods and are particularly useful for studying the context of specific disease genes or drug targets [1].

- Functional Module Detection: Identify densely connected communities within the network using community detection algorithms. These modules often correspond to protein complexes, functional pathways, or coordinated biological processes.

- Disease Subnetwork Analysis: Extract and analyze subnetworks enriched for disease-associated genes to identify disease-specific modules and potential therapeutic targets. Compare network properties between healthy and disease states to identify topological changes associated with pathological conditions [2].

Table 3: Key Network Analysis Metrics and Their Biological Interpretation

| Metric | Calculation | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Degree centrality | Number of connections per node | Hub proteins; often essential genes with central cellular functions |

| Betweenness centrality | Number of shortest paths passing through a node | Bottleneck proteins; connect different network modules; potential drug targets |

| Closeness centrality | Average shortest path length to all other nodes | Proteins that can quickly interact with many others in the network |

| Clustering coefficient | Proportion of a node's neighbors that are connected to each other | Members of tightly interconnected functional modules or complexes |

| Eigenvector centrality | Connections to highly connected nodes | Influential proteins within the network; often key regulators |

Successful interactome mapping requires a combination of experimental reagents, computational tools, and data resources. The following table summarizes key solutions and their applications in PPI research.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Interactome Mapping

| Resource | Type | Function | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| STRING | Database [5] | Functional protein association networks | Integrating known and predicted PPIs with confidence scores; pathway analysis |

| BioGRID | Database [3] | Curated protein, genetic, and chemical interactions | Accessing manually curated physical and genetic interactions from published studies |

| NetworkX | Python library [6] | Network creation, manipulation, and analysis | Calculating network metrics; generating custom network analyses and visualizations |

| Cytoscape | Desktop application [2] | Network visualization and analysis | Interactive network exploration; creating publication-quality figures |

| Yeast Two-Hybrid System | Experimental platform [1] | Detecting binary protein-protein interactions | Screening cDNA libraries for novel interactions; mapping binary interactomes |

| TAP/FLAG tags | Affinity purification tags [1] | Purifying protein complexes under native conditions | Identifying co-complex memberships; studying complex composition under different conditions |

| CRISPR Screening Resources (BioGRID ORCS) | Database [3] | Repository of CRISPR screening data | Identifying genetic dependencies; validating PPI networks through genetic interactions |

Defining the interactome from stable complexes to transient interactions requires an integrated approach combining experimental methods for interaction detection, computational approaches for prediction and validation, and network analysis techniques for biological interpretation. The scale-free nature of PPI networks, with their characteristic hub proteins and modular organization, provides important insights into cellular organization and the molecular basis of disease. As interaction databases continue to expand and methods improve, network-based approaches will play an increasingly important role in identifying novel drug targets, understanding disease mechanisms, and advancing systems-level models of cellular function. The protocols and resources described in this application note provide a foundation for researchers to explore and characterize protein interaction networks in their biological systems of interest.

The analysis of Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks is a cornerstone of modern systems biology, providing crucial insights into cellular function, disease mechanisms, and drug discovery. The architectural principles governing these networks are not random; they exhibit distinct topological properties that define their behavior and functional capabilities. Among these, scale-free and small-world topologies have been extensively documented and characterized within biological systems [7] [8]. A third class, Highly Optimized Tolerance (HOT) networks, represents a model for systems designed for high robustness in specific environments. This article delineates these three key network topologies—scale-free, small-world, and HOT—within the context of PPI research. We provide a structured comparison, detailed protocols for their analysis, and visual tools to aid researchers and drug development professionals in interpreting complex interactome data.

The following table summarizes the defining characteristics, biological significance, and key metrics for the three network topologies in the context of PPI research.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Network Topologies in PPI Research

| Feature | Scale-Free Networks | Small-World Networks | Highly Optimized Tolerance (HOT) Networks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Defining Topological Property | Power-law degree distribution: ( P(k) \sim k^{-\gamma} ) [9] | High clustering coefficient & short average path length [10] | Structured, optimized topology for specific tasks and predictable failures |

| Representation in PPINs | Most proteins have few partners; a few "hub" proteins have many [7] | Any two proteins are connected via a short path; proteins form dense clusters [8] | (Theoretical model for robust system design; less commonly a primary descriptor for native PPINs) |

| Biological Significance | Robustness against random mutations but vulnerability to targeted hub attacks [7] | Efficient signal propagation and information transfer across the network [8] | Suggests evolutionary design for robustness against common perturbations |

| Implications for Drug Discovery | Hub proteins are often essential and represent attractive drug targets (e.g., p53) [7] | Perturbations (e.g., by a drug) can have rapid, widespread effects [8] | Informs the design of therapeutic interventions that are robust to network variations |

| Key Quantitative Metrics | Power-law exponent (( \gamma )), hub identification | Clustering coefficient (C), average path length (L) [10] | Measures of robustness and resource efficiency for expected failure scenarios |

Experimental and Computational Analysis Protocols

Protocol 1: Identifying Scale-Free Properties and Hub Proteins in a PPI Network

Objective: To determine if a given PPI network exhibits scale-free topology and to identify critically important hub proteins. Reagents & Resources: PPI dataset (e.g., from BioGRID [11], STRING [11]), computational environment (e.g., Python/R), network analysis toolbox (e.g., NetworkX, igraph).

Network Construction:

- Input your PPI data, representing each protein as a node and each interaction as an undirected edge.

- Clean the network by removing self-loops and duplicate interactions.

Degree Distribution Analysis:

- Calculate the degree ( k ) for each node (number of connections it has).

- Plot the degree distribution ( P(k) ) on a log-log scale. ( P(k) ) is the probability that a randomly selected node has degree ( k ).

- Fit a power-law distribution ( P(k) \sim k^{-\gamma} ) to the data. A straight-line fit on the log-log plot suggests a scale-free topology. The exponent ( \gamma ) typically falls between 2 and 3 for real-world networks [9].

Hub Identification:

- Define hub proteins based on statistical significance (e.g., nodes with a degree significantly higher than the network average) or a predefined percentile (e.g., top 5%).

- Cross-reference identified hubs with functional databases (e.g., Gene Ontology) to assess their biological roles and essentiality.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Small-World Properties in a PPI Network

Objective: To measure the small-world characteristics of a PPI network, confirming its high local clustering and short global separation. Reagents & Resources: PPI dataset, computational environment, network analysis toolbox.

Metric Calculation:

- Calculate the average clustering coefficient (C) of the network. The clustering coefficient of a node is the probability that two randomly selected neighbors of the node are connected. The average C is the mean of this value across all nodes [10].

- Calculate the average shortest path length (L). This is the average number of steps along the shortest paths for all possible pairs of nodes in the network.

Benchmarking Against Random Networks:

- Generate an ensemble of Erdős–Rényi random networks of the same size (number of nodes) and density (average degree) as your PPI network.

- Calculate the average clustering coefficient (( C{\text{random}} )) and average shortest path length (( L{\text{random}} )) for these random networks.

Small-World Coefficient (σ) Calculation:

- Compute the small-world coefficient: ( \sigma = \frac{C / C{\text{random}}}{L / L{\text{random}}} ) [10].

- A network is typically considered small-world if ( \sigma > 1 ), indicating a much higher clustering coefficient than its random counterpart while maintaining a similar path length.

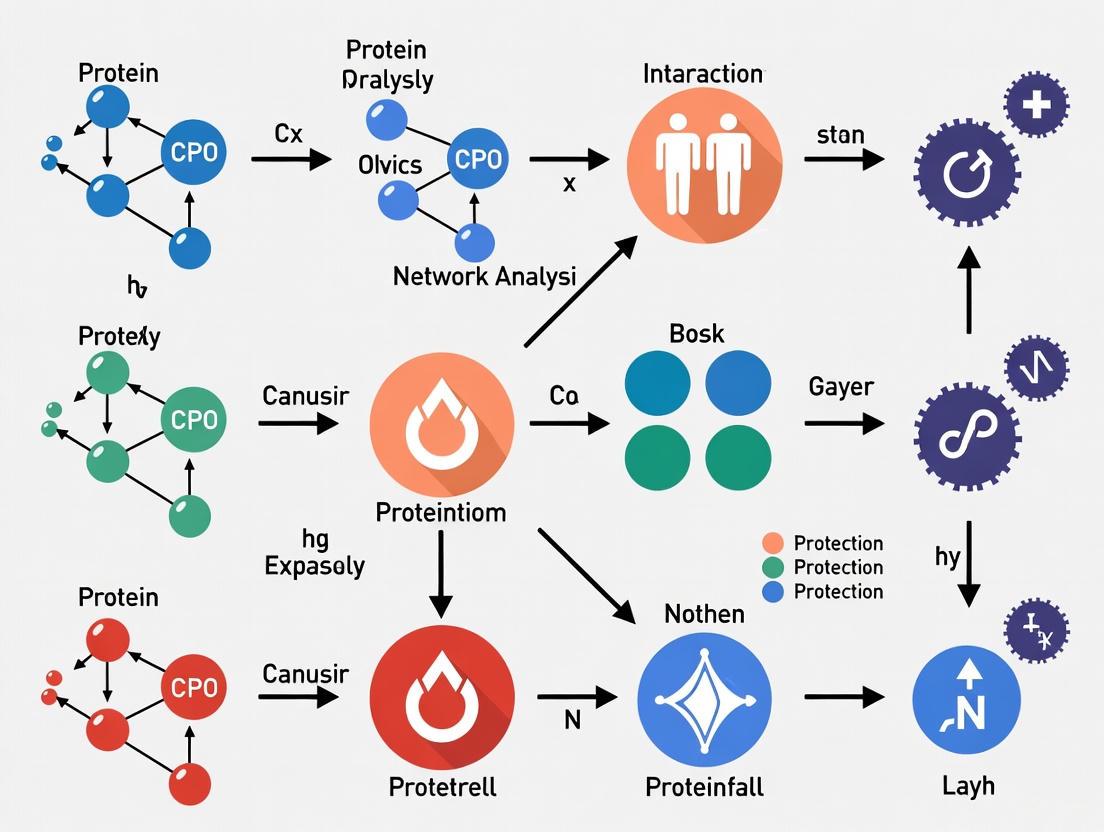

Workflow Visualization for Network Topology Analysis

The diagram below outlines the core computational workflow for analyzing scale-free and small-world properties in a PPI network.

Figure 1: Computational workflow for analyzing PPI network topologies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for PPI Network Topology Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Topology Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| BioGRID [11] | Database | A repository of protein and genetic interactions for constructing networks. |

| STRING [11] | Database | Provides known and predicted PPIs, useful for building more comprehensive networks. |

| Cytoscape | Software Platform | An open-source platform for visualizing complex networks and integrating with attribute data. |

| NetworkX (Python) | Software Library | A Python library for the creation, manipulation, and study of the structure of complex networks. |

| igraph (R/Python) | Software Library | A efficient collection for network analysis, capable of handling large graphs. |

| Gene Ontology (GO) | Database | Provides functional annotations for gene products, used for functional enrichment of hubs. |

Understanding the scale-free and small-world nature of PPI networks provides a powerful framework for explaining their observed robustness, efficient communication, and vulnerability to targeted attacks. While the HOT model offers a compelling perspective on designed robustness, scale-free and small-world properties are well-established, quantifiable features of the interactome. The protocols and tools outlined in this article provide a foundation for researchers to rigorously analyze these topologies, thereby extracting deeper biological insights and informing strategic decisions in drug development and basic research.

In the field of protein-protein interactions (PPIs) research, network analysis techniques have emerged as indispensable tools for deciphering the complex molecular underpinnings of cellular function and disease. Physical interactions among proteins constitute the backbone of cellular function, making them an attractive source of therapeutic targets [12]. The analysis of PPI networks enables researchers to move beyond studying individual proteins to understanding systems-level properties that govern biological behavior.

Three fundamental metrics—degree, clustering coefficient, and betweenness centrality—form the cornerstone of PPI network analysis, providing unique yet complementary insights into network topology and function. These metrics allow researchers to identify proteins with critical structural roles, uncover functional modules, and prioritize candidates for drug discovery efforts. When applied to differentially expressed genes (DEGs) mapped to PPI networks, these metrics can reveal how changes in gene expression translate into broader biological effects, offering deeper insights into the molecular interactions underlying experimental conditions or disease states [13].

This protocol provides detailed methodologies for calculating, interpreting, and applying these essential network metrics in the context of PPI research, with specific consideration for their utility in identifying novel disease-related proteins and their potential use as therapeutic targets.

Theoretical Foundations of Network Metrics

Network Representation of Protein Interactions

In PPI networks, proteins are represented as nodes (or vertices), while their physical or functional interactions are represented as edges (or links). This graphical representation enables the application of graph theory principles to biological systems, transforming complex cellular interactions into computationally analyzable structures.

Formally, a PPI network can be defined as a graph G = (V, E), where V represents the set of proteins (nodes) and E represents the set of interactions (edges) between them. The resulting network can be analyzed to identify key players in cellular processes, with essential genes and successful drug-target proteins often displaying distinctive network properties [14].

Classification of Nodes by Degree

Proteins in PPI networks can be categorized based on their connectivity patterns:

- Low-degree nodes: Proteins with few interactions (typically less than 5) [14]

- Middle-degree nodes: Proteins with intermediate connectivity (typically 6-30 in human PINs) that form tightly interconnected structures called "stratus" [14]

- High-degree nodes: Highly connected proteins (typically more than 31 in human PINs) that connect extensively with low-degree nodes but sparsely with each other, forming an "altocumulus" structure [14]

Research indicates that PPI networks are configured as highly optimized tolerance (HOT) networks, similar to router-level topology of the Internet, where middle-degree nodes form a core backbone for the entire network [14]. This architecture differs from simple scale-free networks generated through preferential attachment and has significant implications for network robustness and drug targeting strategies.

Quantitative Reference Framework

Table 1: Essential Network Metrics for PPI Analysis

| Metric | Mathematical Definition | Biological Interpretation | Typical Range in PINs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree | ( ki = \sum{j \neq i} A_{ij} ) | Number of direct interaction partners a protein has | Human PIN: Low (<5), Middle (6-30), High (>31) [14] |

| Clustering Coefficient | ( Ci = \frac{2ei}{ki(ki-1)} ) | Measures the tendency of a protein's neighbors to interact with each other | Yeast PIN: High for middle-degree (6-38), low for high-degree (>39) nodes [14] |

| Betweenness Centrality | ( g(v) = \sum{s \neq v \neq t} \frac{\sigma{st}(v)}{\sigma_{st}} ) | Quantifies how often a protein acts as a bridge along the shortest path between other proteins | Higher values indicate potential control over information flow in cellular signaling |

Table 2: Node Classification and Properties in Model Organism PINs

| Organism | Low-degree Threshold | Middle-degree Range | High-degree Threshold | Network Architecture Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budding Yeast | <5 | 6-38 | >39 | Highly Optimized Tolerance (HOT) [14] |

| Human | <5 | 6-30 | >31 | Highly Optimized Tolerance (HOT) [14] |

| Key Structural Feature | Connect to high-degree nodes | Form tightly interconnected "stratus" backbone | Form "altocumulus" structure with low-degree nodes | Robust against component failures [14] |

Computational Protocols

Workflow for Comprehensive PPI Network Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for analyzing PPI networks, from data acquisition to the identification and visualization of key network features:

Protocol 1: Network Construction from Differential Expression Data

Purpose: To construct a protein-protein interaction network starting from a list of differentially expressed genes (DEGs).

Materials and Reagents:

- Computing Environment: Python 3.7+ with required libraries (pandas, networkx, requests, matplotlib)

- Data Source: STRING database (https://string-db.org/) for PPI data

- Input Data: CSV file containing DEGs with gene identifiers

Procedure:

- Import necessary libraries:

Load the DEGs CSV file:

Fetch PPI data from STRING database:

Parse and filter PPI data:

Construct network graph:

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If the number of nodes in your network is smaller than your DEG list, some genes may not have corresponding protein interaction data in the database [13].

- For human genes, use species code '9606' in the STRING API call.

- Interaction scores > 0.7 indicate high-confidence interactions suitable for most analyses.

Protocol 2: Calculation of Essential Network Metrics

Purpose: To compute degree, clustering coefficient, and betweenness centrality for all nodes in a PPI network.

Procedure:

- Calculate basic network properties:

Compute degree for all nodes:

Calculate clustering coefficients:

Compute betweenness centrality:

Identify connected components:

Validation Methods:

- Compare your network metrics with published values for quality control.

- Verify that essential genes tend to have higher degree and betweenness values.

- Ensure the network follows typical HOT network properties with specific degree distribution patterns.

Protocol 3: Identification and Visualization of Key Network Nodes

Purpose: To identify hub proteins and central connectors in PPI networks and visualize them effectively.

Procedure:

- Identify hub proteins based on degree:

Identify bottleneck proteins based on betweenness centrality:

Create a visualization with metric-based node coloring:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PPI Network Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| STRING Database | Provides experimentally validated and predicted PPIs | Primary source for interaction data in network construction [13] |

| Cytoscape | Open-source platform for network visualization and analysis | Advanced network styling, analysis, and publication-quality figures [15] |

| NetworkX Python Library | Package for creation, manipulation, and study of complex networks | Core computational toolbox for metric calculation and network analysis [13] |

| NCBI PubMed | Database of biomedical literature | Curated PPI data and validation of network findings [12] |

| Legend Creator App | Cytoscape app for creating customized legends | Generating publication-ready network legends [15] |

Analysis and Interpretation Guidelines

Interpreting Metric Values in Biological Context

The following diagram illustrates the key steps for interpreting network metrics in the context of PPI network analysis:

Degree Interpretation:

- High-degree nodes (hubs) often represent proteins with fundamental cellular functions, but in HOT networks, they may not form the core backbone [14].

- Middle-degree nodes in the "stratus" structure often form the backbone of the network and represent promising drug targets [14].

- Low-degree nodes may perform specialized functions and connect primarily to high-degree nodes.

Clustering Coefficient Interpretation:

- High clustering coefficient indicates proteins whose interaction partners also interact with each other, suggesting functional modules or protein complexes.

- In yeast and human PINs, middle-degree nodes (degrees 6-38 in yeast) show significantly higher cluster coefficients than high-degree nodes [14].

Betweenness Centrality Interpretation:

- High betweenness centrality identifies "bottleneck" proteins that connect different network modules.

- These proteins potentially control information flow and may represent critical regulatory points in cellular signaling.

Application in Drug Discovery

Degree distributions of essential genes, synthetic lethal genes, and human drug-target genes indicate that there are advantageous drug targets among nodes with middle- to low-degree nodes [14]. Such network properties provide the rationale for combinatorial drugs that target less prominent nodes to increase synergetic efficacy and create fewer side effects.

When analyzing PPI networks in disease contexts, focus on:

- Proteins that exhibit both high betweenness centrality and significant differential expression

- Middle-degree nodes that form the backbone of disease-relevant modules

- Network fragmentation patterns that might indicate disrupted cellular processes

Concluding Remarks

The systematic application of degree, clustering coefficient, and betweenness centrality metrics provides a powerful framework for extracting biological insight from protein-protein interaction networks. These metrics enable researchers to move beyond simple interaction lists to understanding the organizational principles of cellular systems.

The recognition that PPI networks are configured as highly optimized tolerance networks with distinct structural features has important implications for drug discovery [14]. Rather than focusing exclusively on highly connected hub proteins, researchers should also consider the strategically important middle-degree nodes that form the backbone of these networks.

As network biology continues to evolve, these essential metrics will remain fundamental tools for translating complex interaction data into meaningful biological discoveries and therapeutic opportunities, particularly when integrated with expression data from differentially expressed genes to create comprehensive models of cellular function and dysfunction.

The Biological Significance of Hubs and Modules in Cellular Function

Biological processes have evolved into intricate systems where proteins act as crucial components, guiding specific pathways. Proteins rarely operate in isolation; over 80% of proteins function within complexes, making the analysis of protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks essential for understanding cellular processes, disease mechanisms, and identifying potential therapeutic targets [16]. Network analysis provides a powerful framework for representing these complex biochemical processes as manageable systems of nodes (proteins) and edges (interactions) [17]. Within these networks, highly connected proteins termed "hubs" and densely interconnected groups of proteins called "modules" play disproportionately important roles in maintaining cellular function and stability [16] [17]. The study of their biological significance has become fundamental to modern systems biology, enabling researchers to move beyond single-molecule reductionism toward a more holistic understanding of cellular dynamics.

Key Concepts: Hubs and Modules

Protein Hubs

In PPI networks, hub proteins are nodes with a significantly higher number of connections compared to the network average. These proteins often serve as critical integration points for multiple biological signals and pathways. Studies have shown that hub proteins can include diverse families of enzymes, transcription factors, and even intrinsically disordered proteins [16]. Due to their central positioning, hubs frequently perform essential biological functions, and their disruption is more likely to cause significant phenotypic consequences compared to non-hub proteins. The identification of hubs provides valuable insights into key regulatory points whose manipulation could offer therapeutic benefits for various diseases.

Network Modules

Modules represent groups of proteins that show dense interconnections among themselves but sparser connections with proteins in other modules. These modules often correspond to:

- Molecular machines performing specific cellular functions (e.g., ribosomes, proteasomes)

- Functional pathways (e.g., signal transduction cascades, metabolic pathways)

- Disease-associated protein complexes

Modules exhibit the property of functional coherence, meaning that proteins within the same module often participate in related biological processes [18] [19]. This characteristic makes module identification particularly valuable for annotating protein functions and understanding how coordinated cellular activities emerge from protein interactions.

Network Properties of Biological Systems

Protein-protein interaction networks exhibit several fundamental properties that have important biological implications:

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Protein-Protein Interaction Networks

| Property | Description | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Scale-free topology | Network connectivity follows a power-law distribution | Robust yet vulnerable to targeted attacks; explains why most mutations have limited effects while some cause significant disruptions |

| Small-world effect | Short average path lengths between any two nodes | Efficient information transfer and signal propagation within the cell |

| Transitivity | High clustering coefficient; neighbors of a node are likely connected | Reflects functional modularity and coordinated protein complexes |

These properties collectively enable biological systems to balance functional specialization (through modular organization) with systems-level integration (through hub connectivity) [17].

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Experimental Techniques for PPI Detection

Several established experimental methods enable the detection and validation of protein-protein interactions, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Protein-Protein Interaction Detection

| Method | Principle | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) | Reconstitution of transcription factor via bait-prey interaction | Binary interaction screening | High-throughput; comprehensive coverage | False positives from auto-activation; limited to nuclear proteins |

| Tandem Affinity Purification-Mass Spectrometry (TAP-MS) | Two-step purification of protein complexes under native conditions | Identification of stable protein complexes | Studies complexes under near-physiological conditions | May miss weak/transient interactions; technically challenging |

| Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) | Antibody-mediated precipitation of target protein and its interactors | Validation of suspected interactions | Works with native proteins in cellular context | Requires specific antibodies; contamination risk |

| Protein Microarrays | High-throughput screening of interactions on solid-phase chips | Proteome-wide interaction mapping | Extremely high-throughput; minimal sample consumption | Immobilized proteins may not reflect native state |

These methods generate the foundational data for constructing PPI networks, though each technique may introduce specific biases that require complementary approaches for validation [16].

Computational Analysis of Hubs and Modules

Computational methods have become indispensable for analyzing the large, complex datasets generated by experimental PPI detection methods:

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) has emerged as a powerful systems biology approach for constructing scale-free gene co-expression networks and identifying gene modules and hub genes [18] [19]. The standard WGCNA protocol involves:

- Network Construction: Calculating pairwise correlations between all genes across samples to create an adjacency matrix

- Module Detection: Using topological overlap measure and hierarchical clustering to identify groups of highly interconnected genes

- Module-Trait Association: Correlating module eigengenes with clinical traits to identify biologically relevant modules

- Hub Gene Identification: Selecting genes with high module membership and gene significance

In a study investigating sepsis-induced myopathy (SIM), researchers applied WGCNA to RNA-seq data from gastrocnemius muscle of LPS-treated mice, identifying key modules enriched for immune response, inflammation, and apoptosis pathways [18]. The hub genes identified (including Cxcl10, Il6, and Stat1) were validated through RT-qPCR and showed high diagnostic potential in ROC curve analysis [18].

Another study focusing on corticosteroid-induced ocular hypertension utilized WGCNA on trabecular meshwork datasets, identifying hub gene modules strongly associated with corticosteroid response [19]. Genes meeting the stringent criteria of |gene significance (GS)| > 0.2 and |module membership (MM)| > 0.8 were classified as hub genes and further validated through protein-protein interaction network analysis [19].

Recent advances in computational methods include deep graph networks (DGNs) for predicting dynamic properties from static PPI networks. One innovative approach, termed DyPPIN (Dynamics of PPIN), enriches PPINs with sensitivity information - a dynamical property measuring how changes in input protein concentration influence output protein concentration [20]. This method successfully predicts sensitivity relationships directly from PPIN topology, bypassing the need for detailed kinetic parameters typically required for ordinary differential equation simulations [20].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PPI Network Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Rneasy Mini Plus Kit (Qiagen) | High-quality RNA extraction | RNA-seq sample preparation for co-expression analysis [18] |

| DESeq2 R Package | Differential gene expression analysis | Identification of significantly altered genes between conditions [18] |

| STRING Database | PPI network resource and analysis | Functional enrichment analysis and network visualization [19] |

| ClusterProfiler R Package | GO and KEGG pathway enrichment | Functional interpretation of gene modules [19] |

| Cytoscape | Network visualization and analysis | Construction and exploration of PPI networks [17] |

| NetworkX Python Package | Network construction and analysis | Computational analysis of network properties [17] |

| CIBERSORT Algorithm | Immune cell infiltration analysis | Deciphering immune context from gene expression data [19] |

Experimental Protocol: Identification of Hub Genes and Modules in Disease

Sample Preparation and RNA Sequencing

Purpose: To generate gene expression data for network construction from disease and control tissues. Materials: Animal or cell line models, RNA extraction kit, RNA-seq library preparation kit, sequencing platform. Procedure:

- Experimental Groups: Divide subjects into experimental (e.g., LPS-induced sepsis) and control groups (n=7-8 per group for adequate power) [18]

- Tissue Collection: Harvest relevant tissues (e.g., gastrocnemius muscle for SIM studies) at appropriate time points post-treatment

- RNA Extraction: Use commercial kits (e.g., Rneasy Mini Plus Kit) to extract high-quality RNA

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare RNA-seq libraries following manufacturer protocols (e.g., Qiagen mRNA-Seq library Prep Kit), sequence using appropriate platform

- Quality Control: Filter raw reads to remove adapters, low-quality reads, and reads with excessive unknown bases using tools like SOAPnuke [18]

Data Preprocessing and Differential Expression Analysis

Purpose: To identify significantly altered genes between experimental conditions. Materials: High-performance computing environment, R statistical software, relevant Bioconductor packages. Procedure:

- Data Normalization: Process raw reads to generate normalized expression values (e.g., RPKM, TPM)

- Differential Expression: Use DESeq2 package in R to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with threshold of FDR < 0.05 and |log2 fold change| > 1.5 [18] [19]

- Data Submission: Submit processed data to public repositories (e.g., GEO) with appropriate accession numbers

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis

Purpose: To identify co-expression modules and hub genes associated with disease phenotypes. Materials: Normalized gene expression matrix, R software with WGCNA package. Procedure:

- Network Construction: Construct a weighted gene network using the WGCNA package in R, selecting appropriate soft-thresholding power to achieve scale-free topology

- Module Detection: Identify modules of highly co-expressed genes using dynamic tree cutting with minimum module size of 30 genes

- Module-Trait Relationship Analysis: Correlate module eigengenes with clinical traits to identify relevant modules

- Hub Gene Identification: Select genes with high module membership (MM > 0.8) and gene significance (GS > 0.2) as hub genes [19]

- Functional Enrichment: Perform GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis on key modules using clusterProfiler [19]

Experimental Validation of Hub Genes

Purpose: To confirm the biological relevance of computationally identified hub genes. Materials: qPCR system, specific primers for hub genes, protein analysis equipment. Procedure:

- Transcript Level Validation: Perform RT-qPCR on hub genes using the same RNA samples

- Statistical Analysis: Confirm significant differential expression patterns consistent with RNA-seq data

- Diagnostic Potential Assessment: Evaluate hub genes' diagnostic utility using ROC curve analysis [18]

- Independent Validation: Validate findings in external datasets when available [18]

Data Presentation and Analysis

Case Study: Sepsis-Induced Myopathy

In a comprehensive study of sepsis-induced myopathy, researchers applied network analysis to identify critical hubs and modules [18]:

Table 4: Hub Genes Identified in Sepsis-Induced Myopathy

| Hub Gene | Log2 Fold Change | Biological Function | Validation Method | Diagnostic Potential (AUC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cxcl10 | Significant upregulation | Chemokine signaling in immune response | RT-qPCR | High (specific values in [18]) |

| Il6 | Significant upregulation | Pro-inflammatory cytokine | RT-qPCR | High (specific values in [18]) |

| Stat1 | Significant upregulation | Signal transduction and transcription activation | RT-qPCR | High (specific values in [18]) |

The functional enrichment analysis revealed that the identified gene modules predominantly pertained to:

- Immune response pathways

- Inflammation mechanisms

- Apoptosis signaling

Using the Connectivity Map (CMAP) database, researchers predicted six potential pharmacological agents that might serve as therapeutic interventions for SIM: halcinonide, lomitapide, TG-101348, GSK-690693, loteprednol, and indacaterol [18].

Case Study: Corticosteroid-Induced Ocular Hypertension

In glaucoma research, network analysis of trabecular meshwork samples identified hub biomarkers and immune-related pathways participating in corticosteroid response [19]:

Table 5: Analytical Approaches in Corticosteroid-Induced Ocular Hypertension Study

| Analysis Type | Datasets Used | Key Parameters | Significant Findings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Expression | GSE124114, GSE37474 | adj. p-value < 0.05, | logFC | > 1.5 | Identified corticosteroid-responsive genes | ||

| WGCNA | GSE124114, GSE37474 | GS | > 0.2, | MM | > 0.8 | Identified hub modules correlated with corticosteroid induction | |

| Immune Infiltration | GSE37474 | CIBERSORT algorithm | Revealed immune cell composition changes | ||||

| Hub Validation | GSE6298, GSE65240 | ROC curve analysis | Confirmed diagnostic accuracy of hub markers |

This study demonstrated how integrating multiple computational approaches provides deeper insights into molecular mechanisms underlying drug-induced side effects, offering potential diagnostic strategies for preventing complications during prolonged corticosteroid therapy [19].

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The integration of PPI network analysis with emerging technologies is opening new frontiers in biological research and therapeutic development. Recent advances include:

Dynamic PPIN Analysis: Traditional PPINs provide static snapshots of the interactome. The novel DyPPIN (Dynamics of PPIN) framework enriches PPINs with sensitivity information computed from biochemical pathways, enabling prediction of how changes in input protein concentration influence output protein concentration without requiring detailed kinetic parameters [20]. This approach uses deep graph networks trained on annotated PPINs to predict sensitivity relationships directly from network topology.

Therapeutic Target Discovery: Hub proteins in disease-associated modules represent promising therapeutic targets. As demonstrated in the SIM study, identified hub genes can be used to query databases like CMAP to predict small molecule compounds that might reverse disease-associated gene expression signatures [18].

Multi-omics Integration: Future directions include integrating PPIN analysis with other data types including genomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data to build more comprehensive models of cellular function. These integrated approaches will enhance our ability to identify critical control points in complex disease networks and develop more effective therapeutic strategies.

The biological significance of hubs and modules extends beyond basic scientific understanding to practical applications in drug development and personalized medicine. As network analysis methodologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly yield increasingly sophisticated insights into cellular function and provide new avenues for therapeutic intervention in complex diseases.

Linking Network Perturbations to Complex Human Diseases

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks form the foundational wiring of cellular processes, where proteins act as crucial components guiding specific pathways and molecular mechanisms [17] [16]. The systematic analysis of these networks provides a holistic framework for understanding how biological components interact and impact one another [21]. When disease-associated mutations impair protein activities within these intricate networks, they cause functional perturbations that disrupt normal cellular function, leading to pathological states [22].

Recent research has demonstrated that a significant majority of disease-associated alleles perturb protein-protein interactions, with approximately two-thirds affecting these critical connections [22]. Strikingly, half of these perturbations correspond to "edgetic" alleles that affect only a specific subset of interactions while leaving most other interactions intact [22]. This nuanced understanding moves beyond traditional models where mutations were assumed to cause complete protein misfolding or stability loss, revealing instead that distinct mutations in the same gene can produce different interaction profiles that often result in distinct disease phenotypes [22].

Experimental Methodologies for Detecting Interaction Perturbations

Protein-protein interaction detection methods are categorically classified into three primary approaches: in vitro, in vivo, and in silico techniques [16]. Each approach offers distinct advantages for capturing different aspects of protein interactions, from stable complexes to transient signaling events.

Table 1: Classification of Protein-Protein Interaction Detection Methods

| Approach | Technique | Summary | Application in Perturbation Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro | Tandem Affinity Purification-Mass Spectrometry (TAP-MS) | Based on double tagging of the protein of interest, followed by two-step purification and mass spectroscopic analysis [16]. | Identifies changes in protein complex composition under wild-type vs. mutant conditions. |

| In Vitro | Protein Microarrays | High-throughput method allowing simultaneous analysis of thousands of parameters within a single experiment [16]. | Screens multiple potential binding partners against mutant protein variants. |

| In Vivo | Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) | Typically carried out by screening a protein of interest against a random library of potential protein partners [16]. | Detects binary interaction changes caused by disease-associated mutations. |

| In Silico | Structure-Based Approaches | Predicts protein-protein interaction if two proteins have similar structure (primary, secondary, or tertiary) [16]. | Models how structural alterations from mutations affect interaction interfaces. |

| In Silico | In Silico Two-Hybrid (I2H) | Method based on the assumption that interacting proteins should undergo coevolution to maintain reliable protein function [16]. | Predicts disruption of coevolutionary patterns in diseased states. |

Detailed Protocol: Affinity Purification-Mass Spectrometry (AP-MS) for Perturbation Detection

Principle: This protocol combines protein complex isolation with mass spectrometry-based identification to detect changes in interaction partners between wild-type and mutant protein variants [16] [23].

Materials:

- Cell culture expressing tagged bait protein (wild-type and mutant)

- Lysis buffer (e.g., RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors)

- Affinity resin appropriate for the tag (e.g., anti-FLAG M2 agarose, glutathione sepharose)

- Wash buffer (compatible with mass spectrometry)

- Elution buffer (specific to the affinity tag)

- Mass spectrometry system (LC-MS/MS)

Procedure:

- Cell Lysis: Harvest cells expressing either wild-type or mutant tagged bait protein. Lyse cells using appropriate lysis buffer. Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble material.

- Affinity Purification: Incubate cleared lysate with appropriate affinity resin for 2-4 hours at 4°C with gentle rotation.

- Washing: Wash resin 3-5 times with wash buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Elution: Elute bound protein complexes using specific elution buffer or competitive elution.

- Protein Digestion: Denature eluted proteins, reduce disulfide bonds, alkylate cysteine residues, and digest with trypsin overnight at 37°C.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze digested peptides using LC-MS/MS. Identify proteins using database search algorithms.

- Data Analysis: Compare identified prey proteins between wild-type and mutant bait samples to identify significantly altered interactions.

Expected Results: Disease-associated mutations typically show either complete loss of interactions (similar to null alleles) or selective loss of specific interactions (edgetic perturbations) while maintaining other binding partners [22].

Diagram 1: Edgetic perturbation showing selective interaction loss.

Computational Analysis of Perturbed Networks

Network Topology and Centrality Measures

Computational analysis of PPI networks employs various topological properties to identify proteins that play critical roles in network integrity and function [23]. When disease perturbations occur, these measures help pinpoint the most vulnerable points in the network.

Table 2: Centrality Measures for Identifying Critical Nodes in Perturbed Networks

| Centrality Measure | Calculation Method | Biological Interpretation | Application in Disease Networks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree Centrality | Number of direct interactions a protein has [23]. | Indicates highly connected "hub" proteins. | Disease-associated hubs often show altered interaction patterns [23]. |

| Betweenness Centrality | Number of shortest paths passing through a node [23]. | Identifies proteins that act as bridges between network regions. | Perturbations in high-betweenness proteins disrupt information flow. |

| Eigenvector Centrality | Measure of influence based on importance of neighboring proteins [23]. | Reflects connection to well-connected proteins. | Identifies proteins in influential network positions vulnerable to perturbations. |

| Closeness Centrality | Average shortest path length to all other nodes [23]. | Proteins that can quickly reach others in the network. | Perturbations affect efficient communication throughout the network. |

Protocol: Network Perturbation Analysis Using Cytoscape and NetworkX

Principle: This protocol utilizes network analysis tools to identify significant changes in network properties resulting from disease-associated mutations [17] [23].

Materials:

- Python environment with NetworkX library

- Cytoscape software with appropriate plugins

- PPI network data (from databases such as BioGRID, IntAct, or STRING)

- Mutation data with interaction perturbations

Procedure:

- Network Construction: Import PPI data into NetworkX to create a graph object where nodes represent proteins and edges represent interactions.

- Perturbation Modeling: Remove or modify edges corresponding to lost interactions in mutant conditions.

- Topological Analysis: Calculate centrality measures (degree, betweenness, closeness, eigenvector) for both wild-type and perturbed networks.

- Statistical Comparison: Perform statistical testing to identify significant changes in network properties.

- Module Detection: Apply clustering algorithms (MCL, MCODE) to identify functional modules affected by perturbations.

- Visualization: Use Cytoscape to visualize network changes, highlighting perturbed interactions and affected modules.

- Pathway Enrichment: Analyze affected modules for enrichment in specific biological pathways using gene ontology tools.

Key Computational Tools:

- NetworkX: Python library for creating, manipulating, and studying complex networks [17] [23]

- Cytoscape: Open-source software platform for visualizing complex networks [23]

- igraph: Network analysis package available for R and Python [23]

- Bioconductor: Provides R packages for PPI network analysis [23]

Diagram 2: Computational workflow for network perturbation analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Network Perturbation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| TAP-Tag Vectors | Double tagging system for tandem affinity purification [16]. | Isolation of protein complexes under native conditions. | Maintains complex integrity during purification. |

| Protein Microarrays | High-throughput screening of protein interactions [16]. | Simultaneous testing of thousands of potential interactions. | Requires careful normalization controls. |

| Yeast Two-Hybrid System | Detection of binary protein interactions in vivo [16] [23]. | Mapping interaction networks for wild-type vs. mutant proteins. | May produce false positives due to non-physiological conditions. |

| Mass Spectrometry-Grade Reagents | Compatible with protein identification by mass spectrometry [16]. | Identification of co-purified proteins in AP-MS. | Avoid detergents and additives that interfere with MS. |

| Cytoscape Software | Network visualization and analysis [23]. | Visualizing interaction perturbations and network properties. | Multiple plugins available for specialized analyses. |

| NetworkX Library | Python package for network analysis [17] [23]. | Computational analysis of network topology and perturbations. | Requires programming proficiency for custom analyses. |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Development

The systematic analysis of network perturbations offers powerful applications in drug target identification and therapeutic development [22] [23]. By understanding how disease mutations specifically alter interaction networks rather than causing complete protein dysfunction, researchers can develop more targeted therapeutic strategies.

Target Identification Strategy: Proteins that represent bottlenecks in disease-perturbed networks, particularly those with high betweenness centrality in essential pathways, often make promising drug targets [23]. Furthermore, the identification of edgetic alleles that specifically disrupt subsets of interactions enables the development of molecules that might counteract these specific effects rather than general protein stabilization.

Network-Based Drug Discovery Workflow:

- Identify functional modules significantly enriched for disease-associated perturbations

- Prioritize candidate proteins within these modules based on network centrality and druggability

- Validate targets using experimental methods (AP-MS, Y2H) to confirm interaction perturbations

- Screen for compounds that restore disrupted interactions or modulate alternative pathways

- Evaluate network-wide effects of candidate compounds to predict side effects and efficacy

Diagram 3: Network-based drug discovery pipeline.

The integration of experimental and computational approaches for analyzing network perturbations provides a powerful framework for understanding complex human diseases. The demonstration that a substantial proportion of disease-associated mutations cause specific, rather than complete, interaction disruptions has transformed our approach to disease mechanism analysis [22]. Future advances in this field will likely focus on capturing the dynamic nature of these perturbations across different cellular conditions and developmental stages [23], as well as improving the integration of multi-omics data to create more comprehensive models of disease networks [23].

As these methodologies continue to evolve, they will enhance our ability to identify precision therapeutic strategies that specifically target the network perturbations underlying individual disease manifestations, ultimately enabling more effective and personalized treatment approaches for complex human disorders.

Mapping the Interactome: A Guide to Experimental and Computational Techniques

Understanding the intricate networks of protein-protein interactions is fundamental to deciphering cellular signaling, regulatory pathways, and the molecular mechanisms of disease. Among the most established experimental methods for elucidating these interactions are Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) and Affinity Purification-Mass Spectrometry (AP-MS). These techniques form the cornerstone of interactome mapping, providing complementary insights into binary protein interactions and multi-protein complex composition, respectively. When integrated with network analysis techniques, data from Y2H and AP-MS enable the construction and interpretation of complex biological systems, offering a powerful framework for hypothesis generation and validation in protein-protein interaction research [24] [25] [26].

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of these two key methodologies:

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Y2H and AP-MS Methods

| Feature | Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) | Affinity Purification-Mass Spectrometry (AP-MS) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Genetic, reconstitution of transcription factor in vivo [27] [25] | Biochemical, purification of protein complexes followed by identification [28] [29] |

| Interaction Type Detected | Direct, binary interactions [25] | Direct and indirect interactions within complexes [29] |

| Output | Binary data (interaction/no interaction) | List of co-purifying proteins |

| Context | Can detect transient interactions in a cellular environment [27] | Often uses overexpressed bait, may lose transient interactions |

| Throughput | High (array or pooled screening) [25] | Medium to High |

Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) System

Principle and Workflow

The Yeast Two-Hybrid system is a powerful genetic method used to discover binary protein-protein interactions in vivo. Pioneered by Stanley Fields and Ok-Kyu Song in 1989, the system relies on the modular nature of transcription factors, which can be split into a DNA-Binding Domain (DBD) and an Activation Domain (AD) [27] [25]. The protein of interest, termed the "bait," is fused to the DBD. Potential interacting proteins, termed "preys," are fused to the AD. If the bait and prey proteins interact, the DBD and AD are brought into proximity, reconstituting a functional transcription factor that then activates reporter gene expression [27] [25]. This system allows for the immediate availability of the cloned gene of the interacting protein and can detect weak, transient interactions without the need for protein purification [27].

The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual workflow of a Y2H experiment:

Key Protocols and Methodologies

High-throughput Y2H screening can be performed using two primary strategies: array-based and pooled library screening.

Array-Based Screening: In this approach, a defined set of preys (e.g., an ORFeome collection) is arrayed in a systematic order, often on agar plates. The bait strain is then mated with the arrayed prey strains. This method is highly controlled, allows for easy identification of interacting pairs based on the prey's position, and facilitates the distinction of background signals from true positives [25]. It is particularly well-suited for interactome studies of small genomes or focused studies on specific protein complexes [25].

Pooled Library Screening: This strategy involves testing the bait against a pooled mixture of prey clones. Positive yeast colonies are selected, and the interacting prey is identified through sequencing of the prey plasmid. While this method can be more efficient in terms of time and resources for large genomes, it requires significant sequencing capacity and subsequent pairwise retests to confirm interactions [25]. Multiple sampling is necessary to ensure comprehensive coverage of the library.

Advantages and Limitations

The Y2H system offers several key advantages: it detects interactions in a physiological-like environment, requires only a single plasmid construction, and can accumulate a weak signal over time without the need for protein purification or antibodies [27]. However, a significant challenge is the occurrence of false positives, which can arise from spontaneous reporter gene activation or non-specific sticky preys [27]. False negatives can also occur if the fusion proteins are improperly localized or folded in the yeast nucleus, or if the interaction is sterically hindered by the fusion tags [27] [25]. Careful experimental design, including the use of multiple controls and different vector systems, is essential to mitigate these issues [25].

Affinity Purification-Mass Spectrometry (AP-MS)

Principle and Workflow

Affinity Purification-Mass Spectrometry is a robust biochemical technique for the unbiased identification of protein-protein interactions, particularly within stable complexes. The method combines the specificity of affinity purification with the sensitivity of mass spectrometry [29]. The process begins with the engineering of a "bait" protein fused to an affinity tag, such as a polyhistidine (His-tag) or glutathione S-transferase (GST) tag. This fusion protein is expressed in a host cell and used as molecular bait to pull down its interacting partners from a complex biological mixture [29]. The resulting protein complexes are purified, enzymatically digested into peptides, and then analyzed by mass spectrometry to identify the co-purifying "prey" proteins [29].

Key Protocols and Data Analysis

The core of the AP-MS protocol lies in the specific and selective purification of the bait protein and its interactors. After transfection and expression of the tagged bait, the cell lysate is passed through a column or resin containing the immobilized ligand specific to the affinity tag. Unbound proteins are washed away under stringent conditions, and the specifically bound protein complex is eluted, typically by competitive elution (e.g., imidazole for His-tags) [29]. The eluted proteins are then prepared for mass spectrometric analysis, which involves digestion with trypsin, chromatographic separation of peptides, and tandem MS (MS/MS) for peptide identification.

A critical subsequent step is data analysis and network visualization. Tools like Cytoscape are extensively used for this purpose. As demonstrated in a protocol analyzing human-HIV protein interactions, AP-MS data can be imported to create networks where bait and prey proteins are nodes and their interactions are edges [28]. This network can then be enriched by merging it with existing interaction data from public databases like STRING, and functionally analyzed using enrichment tools to identify overrepresented biological pathways [28]. The final network can be effectively visualized by mapping experimental data (e.g., quantitative scores) to visual properties like node color and edge thickness [28].

Advantages and Limitations

AP-MS offers several distinct advantages: it enables the comprehensive and unbiased identification of interacting partners without prior knowledge of the interactors, and it can reveal novel interacting partners or post-translational modifications that might be missed by other techniques [29]. Furthermore, it allows for the characterization of multi-protein complexes under near-physiological conditions. However, the method can identify indirect interactions that are not necessarily physically touching the bait protein, which requires additional validation. It may also miss transient or weakly associated proteins that do not survive the purification process. The requirement for a specific affinity tag and the potential for non-specific background binding are also important considerations [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of Y2H and AP-MS experiments relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key components essential for researchers in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Y2H and AP-MS Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gal4-based Vectors | Plasmids for expressing Bait (DBD fusion) and Prey (AD fusion) proteins [27] [25]. | Y2H |

| ORFeome Libraries | Comprehensive collections of Open Reading Frames (ORFs) cloned into prey vectors [25]. | Y2H (Array Screening) |

| Affinity Tags | Short peptide sequences (e.g., His-tag, GST-tag) genetically fused to the bait protein for purification [29]. | AP-MS |

| Immobilized Ligands | Solid supports (e.g., Ni-NTA resin for His-tags, Glutathione resin for GST-tags) that bind the affinity tag [29]. | AP-MS |

| Yeast Reporter Strains | Genetically engineered yeast (e.g., AH109, Y187) with auxotrophic and colorimetric reporter genes [27] [25]. | Y2H |

| Cytoscape | Open-source software platform for visualizing and analyzing molecular interaction networks [28] [26]. | Data Analysis & Visualization |

| STRING Database | Public database of known and predicted protein-protein interactions used for network enrichment [28] [24]. | Data Analysis |

Integrated Data Analysis and Network Visualization

The true power of Y2H and AP-MS data is unlocked through integrated network analysis and visualization. This process transforms lists of interacting proteins into meaningful biological insights. Visualization is a crucial step, as it helps represent complex network data visually, allowing for the quick exploration and identification of substructures like protein complexes or key hub proteins [26].

However, visualizing protein interaction networks (PINs) presents challenges, including the high number of nodes and connections, the heterogeneity of biological data, and the integration of semantic annotations from ontologies like the Gene Ontology [26]. Effective visualization tools must offer clear rendering, fast performance, and interoperability with diverse data formats and databases [26].

Layout algorithms are the core of any visualization tool. Force-directed layouts are commonly used, as they position related nodes closer together, making highly connected proteins and interaction clusters easily identifiable [28] [24]. When creating visualizations, it is critical to use color and size strategically to encode quantitative data (e.g., AP-MS scores mapped to node color or edge width) and to highlight specific interactions [28]. Following best practices in color palette selection ensures visualizations are both interpretable and effective [30].

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are fundamental regulators of nearly all cellular functions, from signal transduction and transcriptional regulation to synaptic plasticity in neuronal cells [11] [31]. Traditional methods for mapping these interactions, such as co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and affinity purification mass spectrometry (AP-MS), have provided invaluable insights but face significant limitations. These include the inability to capture weak or transient interactions, challenges with insoluble proteins, and the disruption of native cellular contexts during cell lysis [32] [31]. To overcome these hurdles, proximity-dependent labeling (PL) techniques have emerged as powerful alternatives that enable the capture of protein interactions within living cells under near-physiological conditions.

The core principle of PL involves fusing a protein of interest (bait) to an engineered enzyme that catalyzes the covalent tagging of nearby proteins with biotin. These biotinylated proteins can then be selectively purified using streptavidin-coated beads and identified via mass spectrometry, providing a snapshot of the local protein environment or "proxisome" [32] [31]. This review focuses on two principal PL platforms: BioID (biotin ligase-based) and APEX (peroxidase-based), detailing their mechanisms, optimizations, and applications for spatiotemporal interactome mapping. By enabling researchers to resolve context-specific protein complexes with high spatial and temporal precision, these techniques are revolutionizing our understanding of cellular network organization and dynamics [33] [34].

Core Proximity Labeling Technologies: Mechanisms and Evolution

Biotin Ligase-Based Techniques: BioID and Its Successors

The original BioID method, introduced in 2012, utilizes a mutated Escherichia coli biotin ligase (BirA) that catalyzes the conversion of biotin and ATP into a reactive biotinoyl-5'-AMP (bioAMP) intermediate [35] [36]. Unlike the wild-type enzyme, BirA releases this active intermediate, which then covalently attaches to lysine residues of proteins located within approximately 10-20 nm [32] [37]. This promiscuous biotinylation allows for the capture of proximal proteins over an 18-24 hour labeling period, enabling the identification of both stable and transient interactions that might be lost during conventional purification [36].