Parameter Estimation in ODE Models: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to AI-Driven Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide to parameter estimation for Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) models, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Parameter Estimation in ODE Models: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to AI-Driven Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to parameter estimation for Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) models, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of the inverse problem in dynamic systems, explores a spectrum of estimation methodologies from traditional Bayesian inference to cutting-edge AI-driven and hybrid approaches like Universal Differential Equations (UDEs) and Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs). The content addresses common computational challenges such as stiffness, high dimensionality, and noisy data, offering practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Finally, it outlines robust frameworks for model validation, performance assessment, and comparative analysis, equipping practitioners with the knowledge to confidently apply these techniques in biomedical research, pharmacokinetics, and epidemiological forecasting.

The Inverse Problem: Foundational Concepts and Challenges in ODE Parameter Estimation

This technical guide serves as a foundational chapter within a broader thesis introducing parameter estimation in ordinary differential equation (ODE) model research. In systems biology, pharmacology, and drug development, mathematical models formulated as ODEs are indispensable for describing the dynamics of complex systems, such as signaling pathways, pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships, and disease progression [1]. The forward problem—simulating system behavior given known model parameters—is often straightforward. The core computational and statistical challenge, known as the inverse problem, is the process of inferring the unknown parameters of these models from observed, typically noisy and sparse, experimental time-series data [1]. Accurate parameter estimation is critical for model validation, uncertainty quantification, and generating reliable predictions for therapeutic intervention [2].

Core Quantitative Data and Methodological Comparison

The field has evolved from classic optimization techniques to advanced statistical frameworks. The table below summarizes the key methodological paradigms and their characteristics based on recent literature.

Table 1: Paradigms in ODE Parameter Estimation from Time-Series Data

| Method Category | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Representative Tools/References | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-Stage Estimation | Separates smoothing of data (stage 1) from parameter optimization (stage 2). | Provides reliable initial values, reduces effects of numerical instability. | Foundational method informing newer techniques [1]. | Initial parameter fitting for well-behaved systems. |

| Bayesian Inference | Updates parameter probability distributions by integrating prior knowledge with observational data. | Quantifies uncertainty, incorporates prior knowledge, robust to noise and partial observations. | magi package (Manifold-constrained Gaussian Process) [1]; MCMC sampling. |

Uncertainty quantification, model comparison, systems with unobserved components. |

| Dynamic Bayesian Networks | Reformulates ODE parameter estimation as inference in a probabilistic graphical model. | Reduces computational burden while maintaining accuracy for kinetic parameters. | Applied to biochemical network inference [1]. | Estimating reaction rates in large metabolic or signaling networks. |

| Langevin Dynamics Sampling | Samples in the joint space of variables and parameters under constraints, avoiding forward integration for each proposal. | Dramatically reduces computational cost for nonlinear systems; efficient for sampling bifurcations/limit cycles. | Constraint-satisfying Langevin dynamics [2]. | Sampling parameter distributions in oscillatory systems (e.g., circadian rhythms, synthetic biology). |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Constraint-Based Langevin Dynamics Sampling

The following protocol details a cutting-edge methodology for parameter estimation, as presented in recent research [2]. This approach is particularly powerful for sampling parameter distributions in systems exhibiting complex dynamics like limit cycles.

Protocol Title: Bayesian Parameter Estimation for ODEs Using Constraint-Satisfying Langevin Dynamics.

Objective: To obtain the posterior distribution of ODE model parameters consistent with observed time-series data, without requiring numerical integration for each proposed parameter set.

Materials & Computational Setup:

- ODE Model: A defined system of ordinary differential equations, (\frac{d\mathbf{x}}{dt} = f(\mathbf{x}, t, \boldsymbol{\theta})), where (\mathbf{x}) is the state vector and (\boldsymbol{\theta}) are the unknown parameters.

- Time-Series Data: Experimental measurements (\mathbf{Y} = {\mathbf{y}(t1), ..., \mathbf{y}(tN)}), potentially noisy and sparse.

- Prior Distributions: Specify prior probability distributions (p(\boldsymbol{\theta})) for all parameters.

- Likelihood Model: Define a probabilistic model linking the ODE solution (\mathbf{x}(t, \boldsymbol{\theta})) to the data (\mathbf{Y}), e.g., (\mathbf{y}(ti) \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{x}(ti, \boldsymbol{\theta}), \sigma^2)).

- Constraint Formulation: Encode the ODE dynamics as a soft constraint within the target probability distribution. This defines an energy landscape in the joint space of ((\mathbf{X}, \boldsymbol{\theta})), where (\mathbf{X}) is a discretized model trajectory.

Procedure:

- Initialization: Propose an initial parameter set (\boldsymbol{\theta}0) and an initial discretized trajectory (\mathbf{X}0) that roughly fits the data.

- Langevin Dynamics Step: Instead of a standard Metropolis-Hastings step, perform simultaneous updates using gradient-based Langevin dynamics: a. Calculate the gradient of the log-posterior (including terms from the data likelihood, parameter priors, and the ODE constraint) with respect to both (\mathbf{X}) and (\boldsymbol{\theta}). b. Update the joint state ((\mathbf{X}, \boldsymbol{\theta})) using the Langevin equation: [ (\mathbf{X}{n+1}, \boldsymbol{\theta}{n+1}) = (\mathbf{X}n, \boldsymbol{\theta}n) + \epsilon \nabla \log p(\mathbf{X}n, \boldsymbol{\theta}n | \mathbf{Y}) + \sqrt{2\epsilon} \boldsymbol{\eta}n ] where (\epsilon) is the step size and (\boldsymbol{\eta}n) is Gaussian noise.

- Constraint Satisfaction: The gradient term derived from the ODE constraint naturally guides the sampler toward trajectories that satisfy the model dynamics, effectively "morphing" the trajectory and parameters simultaneously.

- Iteration & Sampling: Repeat Step 2 for a large number of iterations. After a burn-in period, collect samples ({(\mathbf{X}n, \boldsymbol{\theta}n)}) which represent draws from the joint posterior distribution.

- Analysis: Marginalize over (\mathbf{X}) to analyze the posterior distribution of parameters (p(\boldsymbol{\theta} | \mathbf{Y})). Assess convergence using standard MCMC diagnostics.

Key Advantage: This method avoids the high rejection rate of classic MCMC by not requiring an exact forward integration for each proposal, leading to significant computational speedups, especially for models where dynamics nonlinearly depend on parameters [2].

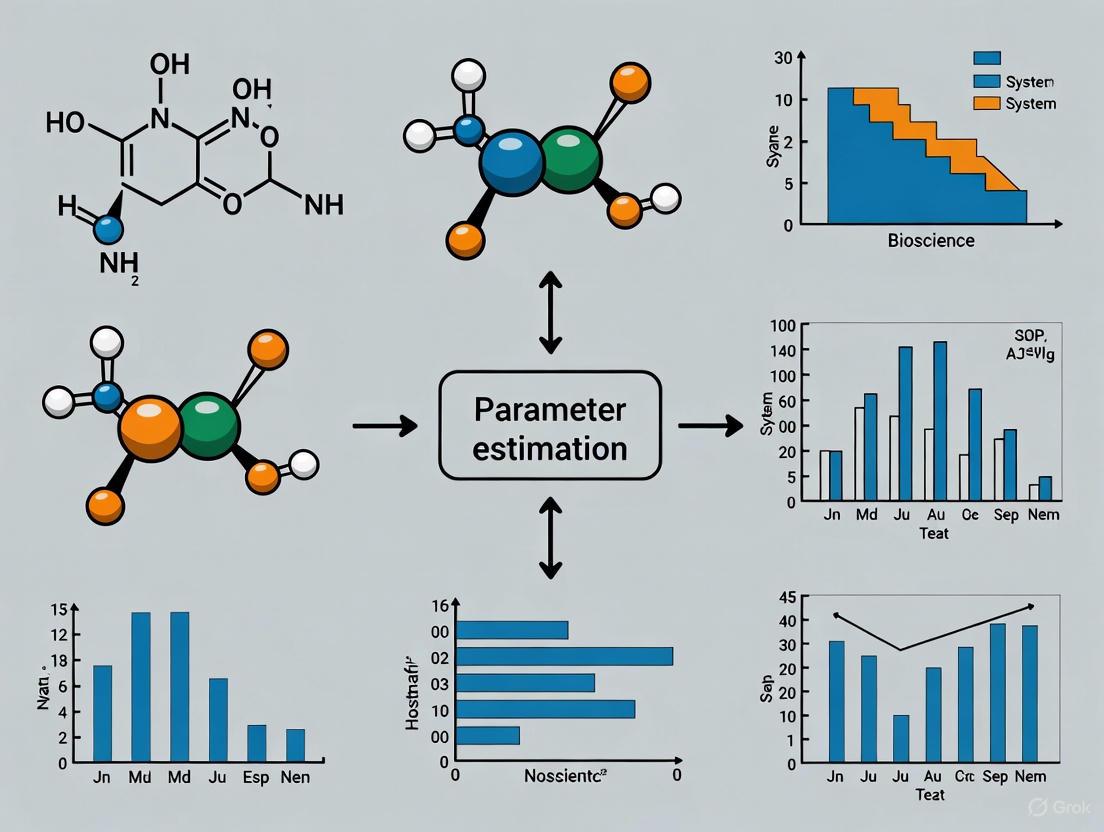

Visualizing the Inverse Problem Workflow and Methodology

The following diagrams illustrate the conceptual framework and the specific Langevin dynamics protocol described above.

Diagram 1: The Inverse Problem in Systems Modeling

Diagram 2: Constraint-Satisfying Langevin Dynamics Protocol

Successful parameter estimation research relies on a combination of specialized software, computational resources, and theoretical frameworks.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ODE Parameter Estimation

| Item | Category | Function/Brief Explanation | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

magi Package |

Software Library | Implements a manifold-constrained Gaussian process framework for Bayesian inference in ODEs with unobserved components, without requiring explicit derivative estimation. | [1] |

| Langevin Dynamics Sampler | Custom Algorithm | Enables efficient sampling of parameter posterior distributions by exploring the joint variable-parameter space under ODE constraints, bypassing costly forward integration. | [2] |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Computational Resource | Provides the necessary parallel processing power for running extensive simulations, MCMC sampling, and large-scale model fitting tasks. | MGCF resources [3] |

| Statistical Programming Environment | Software Platform | Flexible environment (e.g., R, Python with SciPy/Stan/PyMC) for implementing custom estimation algorithms, data analysis, and visualization. | D-Lab workshops [3] |

| Bayesian Inference Framework | Theoretical Toolbox | Provides the statistical foundation for quantifying parameter uncertainty, incorporating prior knowledge, and performing model comparison. | [1] [2] |

| ODE Solver Suite | Numerical Software | Core library for accurate numerical integration of differential equations (e.g., deSolve in R, solve_ivp in SciPy), essential for forward simulations and certain estimation methods. |

Foundational for all work |

| Electronic Lab Notebook (ELN) | Data Management | Securely records experimental protocols, raw time-series data, and analysis workflows, ensuring reproducibility and traceability. | Signals Notebook [3] |

This technical guide explores two cornerstone applications of parameter estimation in ordinary differential equation (ODE) models within biomedical research: epidemiological forecasting and Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling. Framed within a broader thesis on ODE parameter estimation, this document provides researchers and drug development professionals with in-depth methodologies, comparative data, and essential toolkits for implementing these powerful computational approaches.

Ordinary Differential Equations are pivotal for modeling dynamic processes in biology and medicine. The "forward problem" involves simulating system behavior for a given set of parameters, while the "inverse problem" or parameter estimation uses experimental data to infer these unknown parameters [4]. This inverse problem is computationally challenging but essential for creating predictive models that can inform public health decisions and drug development processes.

Parameter estimation connects mathematical models with empirical observation, transforming a theoretical framework into a validated tool for prediction and hypothesis testing. The applications discussed herein are united by their reliance on estimating key parameters from observed data to generate mechanistic, physiologically realistic simulations.

Epidemiological Forecasting with Compartmental Models

Core Methodology and Integration with AI

Compartmental models, such as the Susceptible-Infectious-Recovered (SIR) framework, use ODEs to simulate disease spread through a population. The core SIR dynamics are described by:

dS/dt = -βIS dI/dt = βIS - γI dR/dt = γI

where S, I, and R represent the proportions of susceptible, infectious, and recovered individuals, respectively. The critical parameters to estimate are the transmission rate (β) and recovery rate (γ) [5].

A key advancement is integrating these mechanistic models with data-driven artificial intelligence (AI). Hybrid models combine AI with traditional epidemiological frameworks to enhance forecasting accuracy. AI excels at processing large, complex datasets from sources like satellites and social media, which can be overwhelming for traditional methods [6]. AI's primary roles in these integrated systems include:

- Model Parameterization and Calibration: Identifying and fine-tuning the best values for epidemiological parameters like

βandγto ensure model outputs align with real-world data [6]. - Disease Forecasting and Intervention Assessment: Predicting future outbreak trajectories and evaluating potential impacts of interventions such as vaccination campaigns [6].

A specific implementation, the Physics-Informed Spatial IDentity neural network (PISID), avoids the complexity of graph-based neural networks. Instead, it uses a spatial embedding matrix to encode regional characteristics and a fully connected neural network to infer epidemiological parameters, which then govern an SIR model for forecasting [5].

Experimental Protocol for Hybrid Model Development

Objective: To develop and validate a hybrid physics-informed AI model for multi-region epidemic forecasting.

Workflow:

Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Inputs: Gather historical time-series data on confirmed cases, recovered cases (if available), and population data for each region.

- Cleaning: Address missing values and reporting inconsistencies. Normalize case counts, for example, per 100,000 population.

Spatio-Temporal Encoding:

- Encode regional characteristics and temporal information using an embedding matrix, avoiding complex graph structures [5].

Parameter Inference:

- Feed the encoded spatio-temporal information into a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) to infer region-specific and time-varying epidemiological parameters (e.g.,

β,γ) [5].

- Feed the encoded spatio-temporal information into a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) to infer region-specific and time-varying epidemiological parameters (e.g.,

Mechanistic Model Forecasting:

- Use the inferred parameters to drive the dynamics of a compartmental model (e.g., SIR).

- If the infectious compartment

Iis unobserved, estimate it from the confirmed case data within the model framework. - Numerically solve the ODE system to generate forecasts of future cases [5].

Model Validation:

- Compare forecasts against held-out test data using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

- Perform ablation studies to validate the contribution of the neural network encoding and the physics-based model [5].

Table 1: Key Software and Research Reagents for Epidemiological Modeling

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| SIR/SEIR Framework | Mathematical Model | Provides the foundational ODE structure for simulating disease transmission dynamics. |

| Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) | Neural Network | Infers epidemiological parameters from input data within a hybrid model [5]. |

| Spatial Embedding Matrix | Encoding Technique | Captures unique, time-invariant characteristics of each region for spatial modeling without graphs [5]. |

| Historical Case Data | Dataset | Used for model training, calibration, and validation against real-world outcomes. |

Workflow Diagram for Hybrid Epidemiological Modeling

Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling

Fundamental Concepts and Model Construction

PBPK models are mechanistic constructs that use differential equations to simulate the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) of a compound within the body. Unlike classical "top-down" pharmacokinetic models that rely heavily on fitting plasma data, PBPK models adopt a "bottom-up" approach, integrating independent prior knowledge of human physiology and drug-specific properties to predict drug concentrations in various tissues, including sites of action that are difficult to measure experimentally [7] [8].

A whole-body PBPK model explicitly represents relevant organs and tissues—such as heart, lung, liver, gut, kidney, and brain—interconnected by the circulatory system [7]. The fundamental differential equation governing a tissue compartment is based on mass balance:

Vtissue * (dCtissue/dt) = Qtissue * (Carterial - Cvenoustissue)

where V_tissue is the tissue volume, Q_tissue is the blood flow rate, C_arterial is the arterial drug concentration, and C_venous_tissue is the venous drug concentration leaving the tissue [8]. Drug distribution into tissues is typically described by one of two major assumptions:

- Perfusion-Limited (Flow-Limited) Model: Assumes that membrane permeability is high, and distribution is governed by the rate of blood delivery to the tissue.

- Permeability-Limited (Diffusion-Limited) Model: Accounts for the resistance of the cellular membrane to drug penetration, requiring permeability parameters [8].

The parameters required for a PBPK model fall into three categories:

- Organism Parameters: Species- and population-specific physiological values (e.g., organ volumes, blood flow rates, tissue composition) [7] [8].

- Drug Parameters: Physicochemical properties of the compound (e.g., lipophilicity (logP), solubility, molecular weight, pKa) [7] [8].

- Drug-Biological Properties: Parameters describing the interaction between the drug and the biological system (e.g., fraction unbound in plasma (fu), tissue-plasma partition coefficients (Kp), and metabolic clearance rates) [7].

Key Applications in Drug Development

PBPK modeling has become an integral tool in modern drug development and regulatory science, with several critical applications [7] [9] [8]:

- Predicting Drug-Drug Interactions (DDI): PBPK models can mechanistically simulate the impact of one drug inhibiting or inducing the enzyme responsible for metabolizing another, supporting dose adjustments and potentially reducing the need for clinical DDI studies [8].

- Extrapolation to Special Populations: PBPK models enable virtual simulations of patient subgroups where clinical trials are ethically or practically challenging. This includes:

- Pediatric Populations: Scaling an adult PBPK model by incorporating age-dependent physiological changes [7] [9].

- Organ Impairment Populations: Modifying organ volumes, blood flows, and enzyme function to simulate PK in patients with hepatic or renal impairment [9].

- Genetic Polymorphisms: Incorporating variations in enzyme abundance (e.g., CYP2C19, CYP2D6) to predict exposure in different metabolizer phenotypes across ethnicities [9].

- Formulation Optimization: Modeling oral absorption and dissolution to predict the in vivo performance of different formulations, thus reducing costly bioequivalence studies [8].

Experimental Protocol for PBPK Model Development and Verification

Objective: To construct, qualify, and apply a PBPK model for predicting human pharmacokinetics and drug-drug interactions.

Workflow:

Model Structure Definition:

- Select the relevant physiological compartments (e.g., liver, gut, kidney, adipose).

- Determine the distribution assumption (perfusion- or permeability-limited) for each tissue [8].

Parameter Acquisition:

- System Parameters: Obtain from integrated physiological databases within PBPK software (e.g., organ volumes, blood flows).

- Drug Parameters: Input measured or predicted physicochemical properties (logP, pKa, solubility) [7] [8].

- Drug-Biological Parameters: Incorporate in vitro data for plasma protein binding, hepatic metabolic clearance (using IVIVE), and tissue partition coefficients (often predicted by built-in algorithms) [7].

Model Simulation and Calibration:

- Run the initial simulation and compare the predicted plasma concentration-time profile to available in vivo data (e.g., from early clinical trials).

- Calibrate the model by refining key uncertain parameters (e.g., intrinsic clearance) within biologically plausible ranges to improve the fit [8].

Model Validation:

- Use an independent dataset not used for calibration (e.g., a different dosing regimen or a DDI study) to assess the model's predictive performance [8].

Model Application:

Table 2: Key Software and Research Reagents for PBPK Modeling

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Simcyp Simulator | PBPK Software Platform | Predicts DDIs, pediatric PK, and performs virtual population simulations; widely used in regulatory submissions [8]. |

| GastroPlus | PBPK Software Platform | Specializes in modeling oral absorption and formulation performance using physiology-based biopharmaceutics modeling [8]. |

| PK-Sim | PBPK Software Platform | Open-source whole-body PBPK modeling platform for various species [8]. |

| In Vitro to In Vivo Extrapolation (IVIVE) | Methodological Tool | Scales parameters from in vitro assays (e.g., metabolic stability in liver microsomes) to predict in vivo human clearance [7]. |

| Tissue Partition Coefficient (Kp) | Drug-Biological Parameter | Predicts the steady-state distribution of a drug between tissue and plasma; often estimated using mechanistic equations like Poulin and Theil [7]. |

Workflow Diagram for PBPK Model Development

Parameter Estimation Methodologies for ODE Models

Estimating the parameters of ODE models from observed data is a central challenge. The methods can be broadly categorized as follows:

Shooting Methods (Simulation-Based): These methods directly use an ODE solver to compute the model output for a given parameter set. The error between the simulated output and the observed data defines a loss function, which is then minimized using optimization algorithms (e.g., gradient descent, Newton-Raphson, genetic algorithms) [10] [11]. While flexible, these approaches can be computationally expensive, sensitive to initial guesses, and may converge to local minima [10] [4].

Two-Stage Methods (Collocation/Smoothing): These methods first fit smooth curves (e.g., splines, rational polynomials) to the observed data. The derivatives are estimated from these smoothed curves and then substituted into the ODE model, transforming the problem into a simpler algebraic estimation task [10] [4]. This avoids repeated numerical solution of the ODEs but can be sensitive to noise and data sparsity [10].

Algebraic Methods: For rational ODE models, differential algebra can be used to express parameters in terms of the inputs, outputs, and their derivatives. These derivatives are then estimated from the data to solve for the parameters [10]. This approach can be robust to initial guesses but may be computationally complex to derive [10].

Table 3: Comparison of Parameter Estimation Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shooting/Simulation-Based | Minimize error between model simulation and data via optimization. | Highly flexible; applicable to a wide range of models. | Computationally expensive; sensitive to initial guesses; risk of local minima [10] [4]. |

| Two-Stage/Collocation | Fit data with smooth function, estimate derivatives, and substitute into ODE. | Computationally efficient; does not require repeated ODE solving. | Accuracy depends on data density and quality; derivative estimation can amplify noise [10] [4]. |

| Algebraic | Use differential algebra to derive explicit parameter equations. | Does not require initial guesses or search intervals; can handle local identifiability. | Limited to rational ODE models; derivation can be computationally costly [10]. |

Recent innovations aim to increase the robustness of these methods. For example, one approach combines differential algebra for structural identifiability analysis, rational function interpolation for derivative estimation, and numerical polynomial system solving to find parameters, claiming to overcome sensitivity to initial guesses and search intervals [10]. Another study highlights the use of direct transcription (discretizing both controls and states) and comparing local and global solvers to handle challenging parameter estimation problems in biological systems [12].

Epidemiological forecasting and PBPK modeling represent two sophisticated, high-impact applications of ODE parameter estimation in biomedicine. Both fields are increasingly leveraging hybrid methodologies: epidemiology combines mechanistic compartmental models with AI to enhance predictive power, while PBPK modeling integrates physiological knowledge with in vitro data to perform predictive, "bottom-up" simulation. The choice of parameter estimation technique—whether simulation-based, two-stage, or algebraic—depends on the model structure, data quality, and computational constraints. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly enhance our ability to forecast public health crises and optimize drug therapies with greater precision and confidence.

An In-Depth Technical Guide Framed within a Thesis on Introduction to Parameter Estimation in ODE Models Research

Parameter estimation for Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) models is a foundational task for transforming mechanistic biological knowledge into predictive, quantitative tools in systems biology and drug development [13] [14]. This process involves calibrating model parameters to fit observed experimental data, which is crucial for simulating interventions, understanding disease mechanisms, and predicting drug responses. However, moving from a conceptual ODE model to a reliably calibrated one is fraught with significant mathematical and computational hurdles. This whitepaper, framed as a core chapter of a broader thesis on parameter estimation, delves into the three predominant challenges that stymie robust and efficient parameter identification: the non-convexity of the optimization landscape, the stiffness of the underlying dynamics, and the high dimensionality of both parameter and state spaces. We synthesize recent advances from 2024-2025 research, providing a technical guide that not only elucidates these challenges but also offers practical methodologies and tools to address them.

The Triad of Core Challenges

Non-Convexity: The Pitfall of Local Minima

The objective function in ODE parameter estimation—typically a sum of squared errors between model predictions and data—is almost always non-convex in the parameters [15]. This means the optimization landscape is riddled with numerous local minima, and gradient-based local optimizers can easily converge to suboptimal solutions that do not represent the best possible fit. This non-convexity arises from the nonlinear coupling between parameters and states propagated through the ODE solution. Traditional multi-start strategies, where local optimizations are launched from random initial points, are commonly employed but offer no guarantee of locating the global optimum and are computationally expensive [10] [15].

Recent Advancements and Protocols:

- Deterministic Global Optimization: Recent studies assess the potential of state-of-the-art deterministic global solvers, which use convex relaxations and branch-and-bound frameworks to guarantee global optimality. Current methods are typically limited to problems with ~5 states and 5 parameters, but advances aim to push these boundaries [15].

- Experimental Protocol: The problem is transformed via direct transcription into a large-scale Nonlinear Programming (NLP) problem. Solvers like BARON or ANTIGONE are then applied, exploiting problem structure to tighten bounds and prune the search space.

- Hybrid Two-Stage Global-Local Search: A pragmatic and increasingly automated approach combines a global exploration phase (e.g., Particle Swarm Optimization - PSO) with a subsequent gradient-based refinement [14]. Agentic AI workflows now automate this pipeline, handling the transition between stages [14].

- Experimental Protocol: A population-based algorithm (e.g., PSO) explores the bounded parameter space for a fixed number of iterations or until convergence stagnates. The best-found parameters are then used to initialize a local optimizer (e.g., L-BFGS) that utilizes gradients computed via automatic differentiation through the ODE solver.

- Algebraic and Two-Stage Methods: For rational ODEs, a novel class of methods uses differential algebra and rational function interpolation of data to derive polynomial equations for parameters. This approach can identify all locally identifiable solutions without initial guesses, addressing non-convexity by characterizing the solution manifold [10].

Quantitative Performance Data: The following table summarizes the impact of strategies on handling non-convexity, drawn from benchmark studies.

Table 1: Strategies for Non-Convex Optimization in ODE Parameter Estimation

| Strategy | Key Principle | Guarantee | Typical Scale (States/Params) | Computational Cost | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-start + Local NLP | Random sampling of starts, local convergence | None (heuristic) | Medium-Large | High, scales with starts | [15] |

| Deterministic Global (e.g., BARON) | Convex relaxations & spatial branch-and-bound | Global optimum | Small (~5/~5) | Very High | [15] |

| Hybrid (PSO + Gradient) | Global exploration followed by local refinement | None, but robust | Medium | Medium-High | [14] |

| Algebraic/Two-Stage (ParameterEstimation.jl) | Differential algebra & data interpolation | All local solutions | Medium (Rational ODEs) | Low (avoids repeated ODE solves) | [10] |

Stiffness: The Burden of Multi-Scale Dynamics

Biological systems often exhibit processes operating on vastly different time scales (e.g., fast phosphorylation vs. slow gene expression), leading to stiff ODEs [13] [16]. Stiffness causes explicit numerical solvers (e.g., explicit Runge-Kutta) to require extremely small step sizes for stability, rendering simulations and the associated gradient computations prohibitively slow. This directly impedes the efficiency of parameter estimation.

Recent Advancements and Protocols:

- Specialized Stiff Solvers in Modern Frameworks: The use of robust, implicit, or adaptive solvers designed for stiffness is essential. The SciML ecosystem in Julia, for instance, provides easy access to solvers like

KenCarp4(an implicit Runge-Kutta method) which automatically handle stiff dynamics [13].- Protocol: Within a parameter estimation pipeline, the ODE model is defined and passed to an appropriate stiff solver. The solver's tolerances (

abstol,reltol) are tuned to balance accuracy and speed.

- Protocol: Within a parameter estimation pipeline, the ODE model is defined and passed to an appropriate stiff solver. The solver's tolerances (

- Gradient Computation via Adjoint Methods: For stiff systems, computing gradients for optimization via finite differences is unstable and inefficient. The adjoint sensitivity method provides a stable and scalable way to compute gradients by solving a backward-in-time ODE, and is particularly well-suited for stiff problems [14].

- Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) and Extensions: While vanilla PINNs struggle with stiffness, enhanced formulations like PINNverse reformulate the learning as a constrained optimization problem, improving stability and convergence for inverse problems involving stiff dynamics [17].

- Modified Iterative Algorithms: New numerical methods introduce modified Jacobian matrices within implicit integration schemes to enhance stability and convergence speed for stiff and high-dimensional systems [18].

Table 2: Numerical Solutions for Stiff ODEs in Parameter Estimation

| Solution Component | Example | Role in Mitigating Stiffness | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implicit/Adaptive Solver | KenCarp4, Rodas5, CVODE_BDF |

Uses stable implicit methods to take larger steps | Essential in any simulation-based estimation (shooting, least squares) [13] |

| Sensitivity Algorithm | Adjoint Sensitivity, Forward-Mode Automatic Differentiation | Provides efficient/stable gradient calculation | Critical for gradient-based optimization with stiff models [14] |

| Advanced Neural Solver | PINNverse (Constrained Optimization) | Balances data and physics loss dynamically to overcome training instability | Inverse problem solving with sparse/noisy data [17] |

| Stable Iterative Algorithm | Extended algorithm with modified Jacobian [18] | Improves convergence properties for nonlinear solves in implicit integration | Useful in simultaneous (direct transcription) estimation approaches |

High Dimensionality: The Curse of Many Parameters and States

High-dimensional problems arise from models with many unknown parameters or state variables, such as in large-scale gene regulatory networks (GRNs) [16]. The parameter space grows exponentially, making exploration intractable ("curse of dimensionality"). Furthermore, estimating derivatives or fitting data for many states compounds computational cost.

Recent Advancements and Protocols:

- Dimensionality Reduction via Clustering (CSIEF Procedure): For GRNs, genes with similar expression profiles are clustered into functional modules. Parameter estimation is then performed on the reduced ODE system governing module dynamics, drastically cutting dimensionality [16].

- Protocol: A nonparametric mixed-effects model with a mixture distribution is used for clustering time-course gene expression data. Subsequent ODE modeling and variable selection (e.g., SCAD) are performed at the module level.

- Mixed-Effects Modeling: This statistical framework borrows strength across similar units (e.g., cells, subjects). It separates fixed effects (common parameters) from random effects (individual variations), effectively reducing the number of unique parameters to estimate per individual while accounting for variability [16].

- Sparse Identification and Regularization: Techniques like L1 regularization or the Smoothly Clipped Absolute Deviation (SCAD) penalty are used during inference to drive unnecessary parameters (e.g., weak regulatory links in a network) to zero, promoting interpretable and low-dimensional models [16].

- Universal Differential Equations (UDEs): UDEs address partial mechanistic knowledge. Instead of modeling a fully high-dimensional mechanistic system, unknown parts are replaced with a neural network, which is a flexible but parameterized function. Crucially, regularization (e.g., L2 weight decay) is applied to the ANN component to prevent it from overfitting and to maintain a balance with the interpretable mechanistic parameters [13].

- Agentic AI for Automated Pipeline Scaling: Agentic workflows automate the translation of model specs into differentiable, compiled code (e.g., in JAX), enabling efficient parallel computation across high-dimensional parameter searches and managing the complexity on behalf of the researcher [14].

Table 3: Strategies for Tackling High-Dimensional Parameter Estimation

| Strategy | Mechanism | Typical Dimensionality Reduction | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clustering (e.g., CSIEF) | Groups correlated states (genes) into modules | High: 1000s of genes → 10s of modules | Makes large-scale GRN inference tractable [16] |

| Mixed-Effects Models | Shares information across population, estimates population-level params | Reduces effective params per subject | Handles heterogeneous data; standard in pharmacometrics |

| Sparse Regularization (SCAD/L1) | Adds penalty term to force irrelevant parameters to zero | Identifies parsimonious model structure | Enhances interpretability and generalizability [16] |

| Universal ODEs + Regularization | ANN captures unknown dynamics; regularization controls complexity | Limits ANN from over-parameterizing unknown parts | Balances data-driven flexibility with mechanistic interpretability [13] |

| Automated Differentiable Pipelines | JIT compilation & parallelization of gradient computations | Mitigates computational cost of high-D gradients | Enables practical use of gradient methods on complex models [14] |

Integrated Workflow and Visualization

A modern, robust parameter estimation pipeline must integrate solutions to all three challenges. Below is a proposed workflow and corresponding visualizations.

Diagram 1: Interplay of Core Challenges in ODE Parameter Estimation

Diagram 2: A Modern Integrated Parameter Estimation Pipeline

Diagram 3: Dimensionality Reduction Strategy for High-Dimensional GRNs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

This table details the key software, numerical, and methodological "reagents" required to implement the advanced strategies discussed.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Parameter Estimation

| Category | Reagent/Solution | Function/Purpose | Key Reference/Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Framework | SciML (Julia) / JAX (Python) | Provides ecosystem for differentiable scientific computing, stiff ODE solvers, adjoint methods, and UDEs. | [13] [14] |

| Optimization & Sampling | Particle Swarm Optimizer (PSO) | Global, gradient-free optimizer for initial exploration of non-convex parameter space. | Used in hybrid pipelines [14] |

| L-BFGS / NLopt | Efficient local gradient-based optimizer for final refinement. | Standard in optimization libraries | |

| Differential Algebra Toolbox (SIAN) | Determines parameter identifiability and solution count for rational ODEs. | Used in ParameterEstimation.jl [10] | |

| Numerical Solver | KenCarp4 / CVODE_BDF | Implicit, adaptive solvers for stable integration of stiff ODEs. | Part of SciML Suite [13] |

| Regularization Technique | L2 Weight Decay | Penalizes large weights in ANN components of UDEs to prevent overfitting and aid interpretability. | λ∥θ_ANN∥₂² added to loss [13] |

| SCAD Penalty | Sparse regularization for variable selection in high-dimensional models (e.g., GRNs). | Promotes parsimony [16] | |

| Modeling Paradigm | Universal Differential Equations (UDEs) | Hybrid framework to embed ANNs within mechanistic ODEs for unknown dynamics. | Implemented in SciML [13] |

| Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) | Neural networks trained to satisfy ODE constraints and data; PINNverse improves stability. | For inverse problems [17] | |

| Mixed-Effects Models | Statistical framework for population data, separating shared (fixed) and individual (random) effects. | SAEM algorithm for estimation [16] | |

| Workflow Automation | Agentic AI Workflow | Automates validation, code transformation to JAX, and orchestration of multi-stage optimization. | Described in [14] |

The Critical Role of Uncertainty Quantification in Informed Decision-Making

The development of mechanistic models based on ordinary differential equations (ODEs) is a cornerstone of research in systems biology, pharmacology, and epidemiology. These models translate biological hypotheses into mathematical formalism, allowing researchers to simulate complex dynamics, from intracellular signaling pathways to population-level disease spread [19]. A fundamental and often formidable step in this process is parameter estimation—the calibration of unknown model constants (e.g., reaction rates, transmission coefficients) using observed experimental or clinical data [20]. This inverse problem is ill-posed and fraught with challenges, including noisy and sparse data, structural model misspecification, and the notorious issue of non-identifiability, where multiple parameter sets yield equally good fits to the data [20] [21].

The consequence of ignoring these uncertainties is overconfident and potentially misleading predictions. In high-stakes fields like drug development, where models guide billion-dollar investment decisions and clinical trial design, such overconfidence can be catastrophic [22] [23]. Therefore, moving beyond point estimates to quantify the uncertainty associated with model parameters and forecasts is not merely a statistical refinement; it is a critical component of rigorous, trustworthy, and actionable science. This whitepaper details the methodologies for integrating uncertainty quantification (UQ) into the parameter estimation workflow for ODE models, providing a technical guide for practitioners.

Uncertainty in model predictions stems from multiple, often conflated, sources. Precise UQ requires disentangling these sources, as they inform different mitigation strategies [24].

- Aleatoric (Data) Uncertainty: This is the inherent, irreducible noise in the observational data due to measurement error or stochasticity in the biological process itself. It is typically represented in the error structure (e.g., Poisson, Negative Binomial) of the likelihood function used for parameter estimation [24] [19].

- Epistemic (Model) Uncertainty: This arises from a lack of knowledge, including uncertainty in the estimated parameters, uncertainty about the appropriate model structure, and uncertainty in predictions for inputs far from the training data distribution. This is the primary target of most UQ methods in parameter estimation [24].

- Approximation Uncertainty: Errors introduced by numerical solvers for ODEs or approximate inference methods. While often assumed negligible with modern solvers, it can be significant for stiff or chaotic systems [24] [19].

A robust UQ framework must account for both aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty. The table below summarizes prominent UQ methodologies relevant to dynamical systems modeling.

Table 1: Core Uncertainty Quantification Methods for Model-Based Inference

| Method Category | Core Idea | Representative Techniques | Key Considerations for ODE Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Likelihood-Based & Bootstrapping [20] [19] | Propagate uncertainty from data to parameters by re-sampling or using the likelihood surface. | Parametric Bootstrapping, Profile Likelihood, Fisher Information Matrix. | Computationally intensive but provides asymptotically correct confidence intervals. Requires explicit error model. |

| Bayesian Inference [24] [25] | Treat parameters as random variables with prior distributions; compute posterior distributions given data. | Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), Variational Inference. | Naturally provides full posterior distributions. Incorporates prior knowledge. Computationally very demanding for complex ODEs. |

| Ensemble Methods [24] | Train multiple models (with different initializations, subsets of data, or structures) and assess prediction variance. | Bootstrap Aggregating (Bagging), Deep Ensembles. | Model-agnostic and parallelizable. Can capture model structure uncertainty. May underestimate uncertainty. |

| SDE-Based Regularization [21] | Reformulate an ODE as a Stochastic Differential Equation (SDE) to account for process noise, regularizing the estimation. | Extended Kalman Filtering, Ensemble-based likelihoods for SDEs [26]. | Converts epistemic uncertainty into aleatoric form. Can smooth objective functions, aiding optimization [21]. |

| Selective Classification [22] [23] | In classification tasks (e.g., trial success prediction), the model abstains from prediction when confidence is low. | Conformal Prediction, Monte Carlo Dropout for confidence thresholds. | Directly links UQ to decision-making. Crucial for high-risk applications like clinical trial design [23]. |

Experimental Protocols: Integrating UQ into the Estimation Workflow

Implementing UQ requires embedding it within the parameter estimation pipeline. The following protocols, derived from contemporary toolboxes and research, provide a actionable roadmap [26] [19].

Protocol 3.1: Parameter Estimation with Parametric Bootstrapping

This frequentist approach is widely used for its conceptual clarity and implementation ease [19].

- Model Calibration: Fit the ODE model to the original dataset

yusing an appropriate estimator (e.g., Nonlinear Least Squares, Maximum Likelihood) to obtain the best-fit parameter vectorθ*. - Data Generation: Simulate

N(e.g., 1000) new synthetic datasets{y_sim_i}using the calibrated modelf(t, θ*)and the assumed error structure (e.g., adding Gaussian noise with variance equal to the residual variance, or sampling from a Poisson distribution with meanf(t, θ*)). - Re-estimation: For each synthetic dataset

y_sim_i, re-run the parameter estimation procedure to obtain a bootstrapped parameter vectorθ_i. - Uncertainty Quantification: The empirical distribution of the

Nbootstrapped vectors{θ_i}approximates the sampling distribution of the estimator. Calculate confidence intervals (e.g., 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles) for each parameter and for model forecasts.

Protocol 3.2: Ensemble-Based Likelihood Estimation for Stochastic Models

For models with intrinsic stochasticity or those regularized as SDEs, an ensemble method provides a powerful likelihood approximation [26].

- Problem Formulation: Define an

EnsembleProblemfor the SDE. Specify the number of parallel trajectories (K, e.g., 1000). - Forward Solution: For a given parameter set

θ, solve the SDEKtimes to generate an ensemble of solutions. Compute the summary statistic (e.g., mean trajectoryμ(t, θ)and varianceΣ(t, θ)) across the ensemble at each observation time point. - Likelihood Construction: Define a loss function, such as a Gaussian-based log-likelihood comparing data

yto the ensemble summary:L(θ) ∝ -∑_t [ (y_t - μ(t,θ))^2 / Σ(t,θ) + log Σ(t,θ) ]. A first-differencing scheme can be applied to improve accuracy for the diffusion term [26]. - Optimization & UQ: Optimize

L(θ)to findθ*. To quantify uncertainty, this likelihood can be used within a Bayesian MCMC framework or to compute profile likelihoods.

Protocol 3.3: Uncertainty-Guided Active Learning for Experimental Design

UQ can directly inform which new experiments would most efficiently reduce model uncertainty [24].

- Epistemic Uncertainty Map: Using a UQ method (e.g., Bayesian posterior, ensemble variance), identify regions of the experimental input space (e.g., drug doses, time points) where model predictions have high epistemic uncertainty.

- Acquisition Function: Define a function (e.g., expected information gain, predictive variance) that quantifies the value of a potential new data point.

- Optimal Design: Propose the next experiment(s) at the point(s) that maximize the acquisition function. This strategically collects data where the model is most ignorant.

- Iterative Refinement: Update the model with the new data, re-compute the uncertainty map, and repeat. This closed-loop process maximizes knowledge gain per experimental resource.

The following diagram visualizes the integrated workflow incorporating UQ from model definition to decision support.

Title: Integrated Workflow for Parameter Estimation and Uncertainty Quantification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Robust Inference

Successful implementation of the above protocols relies on a combination of software tools, statistical techniques, and theoretical concepts.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for UQ in Dynamical Systems

| Item / Concept | Function / Purpose | Key Example or Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| DifferentialEquations.jl (Julia) | High-performance suite for solving ODEs, SDEs, and performing ensemble simulations. Essential for Protocol 3.2. | Used in [26] for SDE ensemble parameter estimation. |

| QuantDiffForecast (MATLAB Toolbox) | User-friendly toolbox for parameter estimation, forecasting, and UQ via parametric bootstrapping for ODE models. Embodies Protocol 3.1. | Described in [19] for epidemic modeling. |

| Profile Likelihood Analysis | Assesses practical identifiability by fixing one parameter and optimizing others, revealing flat ridges in the likelihood landscape. | Critical for diagnosing non-identifiability highlighted in [20]. |

| Ensemble Kalman Filter (EnKF) | A data assimilation technique that uses an ensemble of model states to estimate parameters and states in near-real-time, handling nonlinearities well. | Variant used for state estimation in SDE regularization [21]. |

| Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) | A model selection criterion that balances goodness-of-fit with model complexity, penalizing overfitting. Used to choose between competing model structures. | Applied to select among stochastic growth models in [25]. |

| Uncertain Differential Equations (UDEs) | A mathematical framework based on uncertainty theory, an alternative to SDEs when frequency stability of data cannot be assumed. | Proposed for financial and population modeling where SDEs fail [27]. |

| Selective Classification Framework | A decision layer that allows a predictive model (e.g., for clinical trial outcome) to abstain when uncertainty is too high, increasing reliability. | Integrated with HINT model to improve clinical trial prediction [22] [23]. |

Parameter estimation for ODE models is an inverse problem inherently coupled with uncertainty. As demonstrated, this uncertainty is multi-faceted, stemming from data, model structure, and parameters. Ignoring it yields brittle models and overconfident predictions. The methodologies outlined—from bootstrapping and Bayesian inference to SDE-based regularization and active learning—provide a robust arsenal for quantifying this uncertainty.

The ultimate value of UQ is realized in decision-making. In drug development, a forecast with a 95% prediction interval spanning orders of magnitude is a clear signal for caution, potentially triggering a "no-go" decision or a revised trial design [23]. A profile likelihood revealing unidentifiable parameters directs research towards new experiments that can disentangle their effects [20]. By rigorously quantifying what we do not know, we make the knowledge we do have far more powerful and actionable. Integrating UQ is therefore not the final step in analysis but the foundational step towards truly informed and responsible decision-making in science and medicine.

From Bayesian Inference to AI: A Spectrum of Modern Estimation Methodologies

Mathematical models based on ordinary differential equations (ODEs) are essential tools across scientific disciplines for simulating complex dynamic systems, from the spread of infectious diseases to population pharmacokinetics [28] [29]. A fundamental challenge in utilizing these models is parameter estimation—the "inverse problem" of inferring model parameters from observed time-series data while properly accounting for uncertainty [28]. Bayesian methods provide a powerful framework for this task by treating parameters as random variables with probability distributions, enabling researchers to integrate prior knowledge with new data and quantify uncertainty in estimates and predictions [30] [29].

The core of Bayesian inference is Bayes' theorem, which calculates the posterior distribution of parameters given observed data. The theorem is expressed as P(θ|D) = [P(D|θ) × P(θ)] / P(D), where P(θ|D) is the posterior distribution, P(D|θ) is the likelihood, P(θ) is the prior distribution, and P(D) is the evidence [31]. For ODE models in particular, this approach allows for rigorous calibration of parameters such as transmission rates in epidemiology or clearance rates in pharmacokinetics, leading to more reliable predictions and policy decisions [28] [29].

However, implementing Bayesian estimation for ODE models has traditionally required substantial programming expertise in probabilistic programming languages like Stan, creating significant barriers for many researchers [28] [29]. This technical guide explores the core components of Bayesian workflows—Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, prior specification, and the emerging ecosystem of accessible toolboxes—with particular focus on their application to parameter estimation in ODE models.

Theoretical Foundations of Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC)

The Role of MCMC in Bayesian Inference

Markov Chain Monte Carlo comprises a class of algorithms for sampling from probability distributions, making it possible to approximate complex posterior distributions that cannot be computed analytically [32] [31]. In Bayesian statistics, MCMC enables numerical approximation of multidimensional integrals needed for posterior inference [31]. These methods are particularly valuable for ODE models where likelihood functions can be highly complex and computational expensive to evaluate.

MCMC functions as a sampler rather than an optimizer [31]. While optimizers locate parameter values that maximize the likelihood or posterior probability, MCMC generates samples from the posterior distribution, providing a comprehensive view of parameter uncertainty, correlations between parameters, and the overall shape of the posterior [31]. This sampling approach allows researchers to obtain robust uncertainty estimates, understand multimodalities or covariances in their data, and marginalize out nuisance parameters [31].

How MCMC Works

The "Markov Chain" component of MCMC refers to the memoryless property of the process, where each new state depends only on the current state [33]. The "Monte Carlo" component refers to the use of repeated random sampling to approximate the distribution [33]. The most common MCMC algorithms include Metropolis-Hastings, Gibbs sampling, and the No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS) used by Stan [33] [29].

The fundamental process involves an ensemble of "walkers" that explore the parameter space [31]. Each walker:

- Starts at a position defined by a parameter vector

θ - Proposes a move to a new position

θ' - Generates a model with these parameters and compares it to data using a likelihood function

- Accepts or rejects the move based on the ratio of likelihoods between new and current positions [31]

Over thousands of iterations, the collection of accepted positions for all walkers forms a posterior distribution representing the range of plausible parameter values given the data and prior assumptions [33] [31].

Table 1: Common MCMC Algorithms and Their Characteristics

| Algorithm | Key Mechanism | Best Use Cases | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metropolis-Hastings | Accepts/rejects proposed moves based on likelihood ratio | Simple models with moderate parameters | Custom implementations |

| Gibbs Sampling | Samples each parameter from its full conditional distribution | Models with tractable conditional distributions [32] | Custom implementations |

| No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS) | Automatically tunes step size and path length | Complex high-dimensional models [29] | Stan, PyMC3 |

Assessing MCMC Convergence and Performance

Proper implementation of MCMC requires careful assessment of convergence to ensure the algorithm has adequately explored the target distribution [33]. Common diagnostic tools include:

- Trace plots: Visualizations of parameter values across iterations, showing whether chains have stabilized [33]

- Autocorrelation plots: Measure the correlation between samples at different lags, indicating effective sample size [33]

- Gelman-Rubin statistics: Compare within-chain and between-chain variance for multiple chains [29]

Performance varies significantly by programming language. One study found that while R and Python offer rapid development, C and Java provide substantial speed advantages (40-60× faster than R), which can be crucial for complex models requiring long run times [32].

The Critical Role of Prior Distributions

Categories of Priors

In Bayesian analysis, prior distributions represent existing knowledge or beliefs about parameters before observing the data [30] [31]. Priors generally fall into three categories:

- Noninformative Priors: Designed to have minimal influence on posterior inferences, letting the "data speak for themselves" [30]. These are often used when little prior information is available.

- Weakly Informative Priors: Contain some information to keep inferences in a reasonable range without strongly constraining the parameters [30]. These are valuable when data are sparse but strong prior knowledge is lacking.

- Informative Priors: Incorporate substantial information from previous studies, pilot data, or subject matter expertise [30]. These can result in more precise inferences and reduce required sample sizes.

Selecting Appropriate Prior Distributions

The choice of prior distribution depends on the available prior knowledge and the modeling context. Common choices include:

- Normal Priors: Center the distribution around an anticipated value with a specified variance [29]. Suitable when substantial prior knowledge about the parameter exists.

- Uniform Priors: Assume minimal prior knowledge, establishing only a range of plausible values [29]. Useful when reliable prior information is lacking.

- Inverse-Wishart and Wishart Priors: Used for covariance matrices, with Inverse-Wishart often selected for strongly informative priors [34].

- LKJ Priors: Used for correlation matrices, often combined with normal or lognormal distributions for standard deviations [34].

Research has shown that the optimal choice depends on the data structure and degree of informativeness required. For covariance matrix estimation in population pharmacokinetics, Inverse-Wishart or Wishart distributions work well for strongly informative priors, Scaled Inverse-Wishart for weakly informative priors, and Normal + LKJ for noninformative priors [34].

Table 2: Guidance for Prior Distribution Selection in Bayesian Analysis

| Prior Type | When to Use | Recommended Distributions | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informative | Substantial prior knowledge from previous studies or expert knowledge | Normal, Inverse-Wishart, Wishart | Can reduce required sample size; risky if prior is misspecified [30] [34] |

| Weakly Informative | Some prior knowledge available but data should dominate | Scaled Inverse-Wishart, constrained uniform | Provides reasonable constraints without strongly influencing results [30] [34] |

| Noninformative | Little prior knowledge available; desire to let data dominate | Uniform, Normal + LKJ | Requires more data for precise estimates; fewer assumptions [34] [29] |

Prior Sensitivity and Impact on Results

The influence of priors on posterior inferences is particularly important in clinical trials and other settings with limited data. In one Covid-19 trial of nafamostat, researchers used weakly informative priors and obtained a posterior probability of effectiveness of 93%, just below the prespecified 99% threshold for concluding effectiveness [30]. The authors noted that using informative priors based on previous trials would have resulted in an adjusted odds ratio closer to 1.0 and a posterior probability of effectiveness less than 93%, potentially giving decision makers greater confidence in the null results [30].

This highlights the importance of conducting sensitivity analyses with different prior specifications, particularly when data are limited [30] [35]. When prior knowledge is reliable, Bayesian estimation with informative priors is preferred; however, when analysts are overconfident in poor parameter guesses, subset-selection methods may be more robust [35].

Accessible Toolboxes: Lowering Barriers to Bayesian Inference

The BayesianFitForecast Toolbox

BayesianFitForecast is an R toolbox specifically designed to streamline Bayesian parameter estimation and forecasting for ODE models, making these methods accessible to researchers with minimal programming expertise [28] [36] [29]. The toolbox automatically generates Stan files based on user-defined options, eliminating the need for manual coding in Stan's probabilistic programming language [28] [29].

Key features of BayesianFitForecast include:

- User-friendly configuration of ODE models, priors, and error structures

- Automatic MCMC implementation using Stan's No-U-Turn Sampler [29]

- Comprehensive diagnostics including convergence assessment, posterior distributions, credible intervals, and performance metrics [28] [29]

- Built-in Shiny web application for interactive model configuration, visualization, and forecasting [29]

The toolbox supports various error structures appropriate for different data types: Poisson for count data, negative binomial for overdispersed count data, and normal for continuous measurements [29]. This flexibility makes it suitable for diverse applications from epidemiology to healthcare informatics.

Implementation Workflow

Using BayesianFitForecast typically involves these steps:

- Define the ODE Model: Specify the system of differential equations describing the dynamic process

- Configure Model Options: Set parameters, their prior distributions, initial values, and estimation settings

- Load Observational Data: Provide time-series data for model calibration

- Run MCMC Analysis: Execute the Bayesian estimation procedure

- Analyze Results: Examine posterior distributions, convergence diagnostics, and model performance [36]

The following diagram illustrates the complete Bayesian workflow for ODE parameter estimation as implemented in toolboxes like BayesianFitForecast:

Application Examples

BayesianFitForecast has been successfully applied to historical epidemic datasets including the 1918 influenza pandemic in San Francisco and the 1896-1897 Bombay plague [29]. In these applications, researchers compared Poisson and negative binomial error structures within SEIR (Susceptible-Exposed-Infected-Recovered) models, demonstrating robust parameter estimation and forecasting performance [28] [29].

The toolbox is particularly valuable in emerging epidemic situations where data may be limited or noisy, as Bayesian methods can incorporate prior knowledge from related outbreaks or expert opinion to improve inference [28] [29]. The automatic generation of Stan files and comprehensive diagnostic tools significantly reduce the technical barriers to implementing these advanced methods [29].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol for Bayesian ODE Parameter Estimation

A standardized protocol for Bayesian parameter estimation in ODE models includes these key steps:

Model Formulation

Prior Specification

- Select appropriate prior distributions based on available knowledge

- For noninformative settings: Use uniform or diffuse normal priors

- For informative settings: Use normal, gamma, or specialized priors (e.g., Inverse-Wishart for covariance matrices) [34] [29]

- Set hyperparameters based on previous studies or expert knowledge

Likelihood Definition

MCMC Configuration

- Set number of chains (typically 4)

- Determine number of iterations (including warm-up)

- Specify adaptation parameters

- Configure sampler (typically NUTS for ODE models) [29]

Convergence Diagnostics

Posterior Analysis

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Tools for Bayesian ODE Modeling

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role | Implementation Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic Programming Languages | Stan, PyMC3 [33] [29] | Core inference engines for MCMC sampling | Backend for toolboxes; direct coding for advanced users |

| High-Level Toolboxes | BayesianFitForecast (R) [28] [36] [29] | User-friendly interfaces for specifying models and priors | Rapid implementation without deep programming knowledge |

| Diagnostic Packages | Stan diagnostics, PyMC3 plots, coda [33] | Assessing convergence and model fit | Essential post-processing after MCMC runs |

| Differential Equation Solvers | deSolve (R), ODEINT (Python) [28] | Numerical solution of ODE systems | Core component of likelihood calculation |

| Visualization Tools | ggplot2, matplotlib, corner.py [33] [31] | Exploring posterior distributions and model fits | Communication of results and diagnostic checking |

Relationship Between Model Components

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between the key components of a Bayesian ODE model and how they combine to produce posterior inferences:

Bayesian workflows incorporating MCMC methods and thoughtful prior specification provide a powerful approach for parameter estimation in ODE models. The development of accessible toolboxes like BayesianFitForecast is significantly lowering barriers to implementing these advanced methods, making them available to researchers across health informatics, epidemiology, pharmaceutical development, and other fields dealing with dynamic systems [28] [29].

The key to successful implementation lies in appropriate prior selection guided by available knowledge, careful MCMC configuration and diagnostics to ensure reliable inferences, and selection of appropriate error structures for the observational data [30] [29]. As Bayesian methods continue to gain traction in clinical trial design and public health decision-making, tools that streamline their application while maintaining methodological rigor will play an increasingly important role in translating complex mathematical models into practical insights [30] [29].

Future developments in this area will likely focus on improving computational efficiency for high-dimensional models, enhancing diagnostic capabilities, and developing more intuitive interfaces for domain experts who may not have extensive statistical programming backgrounds. The integration of these approaches into mainstream scientific practice promises to enhance our ability to calibrate models to data, quantify uncertainty, and generate reliable predictions from complex dynamic systems.

Parameter estimation for Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) models is a fundamental task in scientific research and drug development, where the goal is to infer unknown model parameters from observed time-series data. This process typically involves solving a minimisation problem to compute the best-fit parameters that minimize the discrepancy between model predictions and experimental measurements. The choice of optimization algorithm—the "solver"—is critical, as it directly impacts the accuracy, reliability, and computational cost of the estimation. Solvers are broadly categorized into local optimizers, which converge to a minimum from a single starting point, and global optimizers, which explore the parameter space more extensively to find the best overall minimum, thus reducing the risk of converging to suboptimal local solutions. The performance of these optimizers varies significantly based on the problem's characteristics, such as non-linearity, presence of constraints, and the computational expense of the ODE model itself. This guide provides an in-depth assessment of traditional local and global solvers, framing their use within the practical context of parameter estimation for ODE models in research and industry.

A Comparative Framework for Local and Global Optimizers

Classification and Core Characteristics

Optimization algorithms can be classified based on their search strategy and scope. Local optimizers efficiently find a minimum in the vicinity of an initial parameter guess. They are often gradient-based and converge quickly but may get trapped in local minima. Global optimizers, in contrast, employ strategies like stochastic sampling or population-based search to explore the entire parameter space, offering a higher probability of finding the global minimum at the cost of increased computational resources. The following table summarizes the core characteristics of common optimizer types.

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Traditional Optimizers

| Optimizer Type | Search Scope | Typical Approach | Key Strengths | Inherent Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Optimizers | Local | Gradient-based, deterministic | High convergence speed near a minimum, computationally efficient for well-behaved problems | High sensitivity to initial guesses; prone to converging to local minima |

| Global Optimizers | Global | Stochastic, heuristic, population-based | Robustness to initial guess; better at finding global minimum on complex landscapes | Computationally expensive; may require many function evaluations; tuning of hyperparameters |

Several specific algorithms are prevalent in scientific computing for parameter estimation. A performance analysis on high-performance computing (HPC) clusters, solving non-linear minimisation problems for signal approximation and denoising, provides a direct comparison of their efficacy [37]. The following table details these algorithms and their experimental performance.

Table 2: Common Solver Algorithms and Experimental Performance

| Solver Name | Classifier | Core Methodology | Reported Experimental Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principal Axis (PRAXIS) | Local | Derivative-free, uses conjugate direction method | Best in minima computation: 38% efficiency with 256 processes for approximation; 46% with 32 processes for denoising [37] |

| L-BFGS (Limited-memory Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno) | Local | Quasi-Newton method, approximates the Hessian matrix | Popular for problems with many parameters; performance highly dependent on problem structure [37] |

| COBYLA (Constrained Optimization by Linear Approximation) | Local | Derivative-free, handles non-linear constraints | Effective for constrained problems without requiring derivatives [37] |

| DIRECT-L (Divide Rectangle-Local) | Global | Deterministic, divides search space into hyper-rectangles | Used for global search; less common in practice compared to stochastic methods [37] |

| ISRES (Improved Stochastic Ranking Evolution Strategy) | Global | Evolutionary algorithm, handles constraints | A robust global strategy, though computationally intensive [37] |

Methodologies for Experimental Comparison

Experimental Design and Workflow

A robust comparison of optimizers requires a structured experimental protocol. A typical workflow involves problem definition, optimizer configuration, computational execution, and performance analysis. The methodology from the HPC comparison study provides a template for such an evaluation [37].

1. Problem Definition: The experiment is designed around two classes of non-linear minimisation problems relevant to real-world applications: signal approximation and signal denoising with different constraints [37]. These problems involve computationally expensive operations, making them suitable for HPC.

2. Optimizer Configuration: A suite of optimizers is selected for head-to-head comparison. This includes both local optimizers (Principal Axis, L-BFGS, COBYLA) and global optimizers (DIRECT-L, ISRES) [37]. Each optimizer is used with its default or standard configuration for a fair comparison.

3. Execution Environment: Experiments are performed on a dedicated HPC cluster to ensure controlled conditions and assess scalability. The cited study used the "CINECA Marconi100 cluster," a top-tier supercomputer, to run tests with varying numbers of processes [37].

4. Performance Metrics: Key metrics are collected for each optimizer run to facilitate comparison [37]:

- Functional Computation: The value of the objective function at the identified minimum.

- Convergence: The number of iterations or function evaluations required to converge.

- Execution Time: The total computational time required.

- Scalability: How performance (e.g., efficiency) changes as the number of parallel processes increases.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

The following table details key software tools and libraries that implement the optimizers and methodologies discussed, forming an essential toolkit for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Parameter Estimation

| Tool/Software | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Optimizer Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| SciML / Julia SciML | Software Framework | A comprehensive ecosystem for scientific machine learning and differential equations. | Implements many local and global optimizers; is the backbone for modern UDE and PINN approaches [13]. |

| ParameterEstimation.jl | Software Package | A Julia package implementing an algebraic parameter estimation approach for rational ODEs. | Provides an alternative, non-optimization-based method for comparison, highlighting robustness issues of traditional optimizers [10]. |

| mrgsolve | R Package | Simulation from ODE-based models (e.g., PK/PD) in R. | Used to simulate ODE models for which parameters need to be estimated, generating data for optimizer testing [38] [39]. |

| Torsten | Library (Stan) | A collection of Stan functions for pharmacometric data analysis using Bayesian inference. | Provides Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) methods, a powerful alternative to traditional optimizers for Bayesian parameter estimation [38] [40]. |

| PINNverse | Training Paradigm | A constrained Physics-Informed Neural Network approach for parameter estimation. | Represents a cutting-edge neural approach against which the performance of traditional optimizers can be benchmarked [17]. |

| bbr / bbr.bayes | R Package | Model management and traceability for NONMEM and Stan. | Helps manage, track, and report the many model runs generated during a systematic optimizer comparison [38] [40]. |

Interpretation of Results and Strategic Guidance

Analysis of Quantitative Findings

The experimental results from the HPC study provide clear, quantitative evidence for solver selection [37]. The Principal Axis (PRAXIS) optimizer demonstrated superior performance in finding the best minima for both signal approximation and denoising tasks. Its efficiency, a measure of how well it utilizes parallel processes, was reported at 38% with 256 processes for the approximation problem and 46% with 32 processes for the denoising problem, outperforming the other tested solvers [37]. This indicates that for these specific classes of problems, a well-chosen local optimizer can be highly effective and scalable.

However, the choice between local and global optimizers is highly context-dependent. Global optimizers like ISRES are designed to be more robust to initial conditions and complex parameter landscapes, a significant advantage when dealing with poorly understood systems or when a good initial parameter guess is unavailable [10]. This robustness comes at a high computational cost, which can be mitigated to some extent through HPC and parallelization, as shown in the scalability analysis [37].

Integrated Workflow for Solver Selection

The following diagram synthesizes the core findings into a strategic decision-making workflow for researchers selecting an optimizer.

This workflow emphasizes that there is no single "best" optimizer. The optimal choice is a strategic decision based on the specific problem. For well-behaved systems or when a good initial estimate is available, efficient local optimizers like Principal Axis are compelling. For complex, poorly understood systems, global optimizers like ISRES are necessary despite their cost. A powerful and widely recommended strategy is the hybrid approach: using a global optimizer to locate the basin of attraction of the global minimum, followed by a local optimizer to rapidly refine the solution to high precision [10]. Furthermore, incorporating methods like regularization is critical to prevent overfitting and improve interpretability, especially when using flexible models [13].

Parameter estimation for Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) models is a foundational challenge in systems biology, pharmacology, and engineering [10]. Traditional approaches, such as simulation-based (shooting) methods, often suffer from non-robustness, dependence on initial guesses, and convergence to local minima, particularly when parameters are only locally identifiable [10]. This research landscape has been transformed by the advent of Scientific Machine Learning (SciML), which hybridizes mechanistic modeling with data-driven learning. Two paradigms at the forefront of this revolution are Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) and Universal Differential Equations (UDEs). This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these hybrid modeling frameworks, framing their development and application within the ongoing quest for robust, efficient, and interpretable parameter estimation in ODE models [10] [13].

Core Paradigms: PINNs and UDEs

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs)

PINNs integrate physical laws, typically expressed as PDEs or ODEs, directly into the loss function of a neural network, enforcing physical consistency during training [41] [42]. Traditional PINNs treat time as an explicit input, which can be incompatible with process control frameworks. Recent advances propose architectures like the Physics-Informed Nonlinear Auto-Regressive with eXogenous inputs (PI-NARX) model, which is accurate, computationally efficient, and designed for dynamic systems [41]. For solving complex PDEs, novel architectures like the augmented Lagrangian-based hybrid Kolmogorov-Arnold network (AL-PKAN) have been introduced to improve interpretability and overcome optimization imbalances inherent in standard multilayer perceptrons [42].

Universal Differential Equations (UDEs)

UDEs explicitly embed neural networks directly into the differential equation's structure, creating a hybrid system: du/dt = f(u, p, t) + NN(u, p, t). This framework is powerful for modeling systems where the underlying physics is only partially known. The neural component learns unmodeled dynamics or corrections from data while the known physics provides structure and interpretability [43] [13]. UDEs have shown significant promise in applications ranging from modeling battery dynamics in smart grids [43] to inferring unknown mechanisms in systems biology [13].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies, highlighting the performance gains of hybrid models over purely data-driven or traditional methods.

| Model | Application | Key Metric | Performance vs. Baseline | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|