Overcoming Computational Bottlenecks in Large-Scale Biological Network Analysis

This article addresses the critical computational challenges researchers face when analyzing large-scale biological networks, such as protein-protein interaction or gene regulatory networks.

Overcoming Computational Bottlenecks in Large-Scale Biological Network Analysis

Abstract

This article addresses the critical computational challenges researchers face when analyzing large-scale biological networks, such as protein-protein interaction or gene regulatory networks. As network data grows exponentially in the post-genomic era, traditional analytical methods are increasingly hampered by memory limitations, processing speed, and scalability issues. We explore foundational concepts, advanced methodologies including AI and high-performance computing (HPC) solutions, and optimization strategies tailored for biomedical applications. A comparative evaluation of modern tools and validation techniques provides a practical guide for selecting appropriate frameworks. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes current knowledge to enable more efficient and insightful network-based discoveries in biomedical research.

The Scaling Problem: Why Large Biological Networks Overwhelm Traditional Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the main types of network analysis, and how do I choose between them? A: The two primary types are Ego Network Analysis and Whole Network Analysis. Your choice depends on the scope of your research question [1].

- Use Ego Network Analysis when your focus is on an individual node (the "ego") and its direct connections ("alters"). This is ideal for studying how an individual's immediate social connections influence behavior, resource access, or information flow. Applications include studying personal influence in public health interventions or analyzing an influencer's network in marketing [1].

- Use Whole Network Analysis when you need to understand the structure and dynamics of an entire bounded system. This approach helps identify influential nodes, discover subgroups or communities, and analyze overall patterns of interaction across an organization or population. It is commonly used in organizational studies to find communication silos or in epidemiology to model disease spread [1].

Q: My genomic dataset is too large to process efficiently. What are my options for simplification? A: For massive biological networks, such as protein-protein interaction or gene co-expression networks, backbone extraction is a key technique for reducing complexity while preserving critical structures [2]. You can use:

- High Similarity (HS) Backbones: These preserve edges with high similarity scores, emphasizing strong, cohesive structures (e.g., tightly interconnected protein complexes). HS-backbones maintain superior connectivity and are robust for initial exploratory analysis [2].

- Low Similarity (LS) Backbones: These retain edges with low similarity scores, highlighting weak or unexpected connections (e.g., novel regulatory pathways). LS-backbones can reveal peripheral structures but may struggle with network fragmentation [2].

Q: How can I analyze data from large-scale, dynamic networks like wireless sensor networks in real-time? A: Traditional batch processing is often unsuitable for dynamic data. Instead, employ stream processing frameworks like Apache Spark Streaming or Apache Flink [3]. These platforms handle data that is potentially unbounded, processing it with low latency as it arrives. This requires using machine learning algorithms adapted for streaming data, which are capable of incremental learning and handling "concept drifts" where the underlying data distribution changes over time [3].

Q: What are the critical steps in a wireless network monitoring experiment to infer neighborhood structures? A: A standard methodology involves passive or active scanning to collect beacon frames [3].

- Data Collection: Deploy sensors or use access points to capture IEEE 802.11 beacon frames, which are broadcast periodically by all access points. The data collected should include the beacon's received power strength [3].

- Data Preprocessing: Clean and integrate the captured data from various heterogeneous sources. This step involves validation and unification of the datasets [3].

- Neighborhood Inference: Use the received power values from multiple beacon measurements to create a reliable map of radio distances between access points. This information can be used to infer network topology and characterize the radio environment [3].

Q: What computational sustainability practices should I consider for large-scale genomic analysis? A: The carbon footprint of computational research is a growing concern. To practice sustainable data science:

- Pursue Algorithmic Efficiency: Re-engineer algorithms to perform complex analyses using significantly less processing power. One team achieved a reduction in compute time and CO2 emissions of more than 99% compared to industry standards by refining their code [4].

- Use Impact Calculators: Tools like the Green Algorithms calculator can model the carbon emissions of a computational task based on parameters like runtime, memory usage, and processor type, helping you make informed decisions [4].

- Leverage Open-Access Resources: Utilize curated public data resources and analytical tools to avoid the repetition of energy-intensive computations [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Network Fragmentation During Backbone Extraction

Issue: When applying a backbone extraction method, the network breaks into many disconnected components, making analysis difficult.

Diagnosis: This is a common problem with Low Similarity (LS) backbones at lower edge retention levels [2]. These methods intentionally keep weak, non-redundant links, which can compromise global connectivity.

Solution:

- Switch to a High Similarity (HS) method: If maintaining a single, connected component is crucial for your analysis (e.g., for studying information flow), use an HS-backbone. HS-backbones are designed to maintain superior interconnectivity and robust structures [2].

- Adjust your retention threshold: Gradually increase the percentage of edges retained in your LS-backbone until the network reaches an acceptable level of connectivity for your specific research question [2].

- Combine approaches: Use an LS-backbone to identify critical weak ties that connect modules, then supplement it with a more connected HS-backbone to understand the core structure.

Problem: Inefficient Processing of Large Network Data

Issue: Analyses are running too slowly, consuming excessive memory, or failing due to the dataset's size.

Diagnosis: This is a fundamental challenge of large-scale network analysis, common in genomics and wireless network analytics. Traditional in-memory processing on a single machine is often insufficient [4] [3].

Solution:

- Adopt Cloud Computing: Migrate your workflow to cloud platforms like Amazon Web Services (AWS) or Google Cloud Genomics. These offer scalable storage and computational power, allowing you to handle terabyte-scale datasets and collaborate globally [5].

- Implement Stream Processing: If your data is continuous (e.g., from network monitors), shift from batch processing to a stream-based model using frameworks like Apache Flink. This reduces latency and avoids the need to store the entire dataset in memory before processing [3].

- Optimize Your Algorithms: "Lift the hood" on your analysis code. Focus on algorithmic efficiency—redesigning algorithms to achieve the same result with significantly fewer computational steps, thereby reducing processing time and power consumption [4].

Problem: Data Integration and Quality in Multi-Omics Studies

Issue: Combining different data types (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) leads to inconsistencies, noise, and unreliable results.

Diagnosis: Multi-omics data is complex and heterogeneous. Each layer has different scales, distributions, and noise characteristics, making integration non-trivial.

Solution:

- Robust Preprocessing: Establish a rigorous preprocessing pipeline. This includes data cleansing, normalization, and transformation specific to each omics layer before integration [3].

- Utilize AI and Machine Learning: Apply AI tools designed for multi-omics data. These can help uncover patterns across different biological layers that might be missed by analyzing each layer in isolation. For example, AI can integrate genomic data with proteomic data to better understand disease mechanisms [5].

- Ensure Informed Consent and Data Governance: Address ethical challenges upfront. For data sharing and integration, ensure that informed consent covers the use of data in multi-omics studies and that your data handling complies with regulations like HIPAA and GDPR [5].

Protocol: Extracting a Similarity-Based Network Backbone

This protocol simplifies a dense network for analysis by preserving the most significant edges based on a link prediction similarity function [2].

1. Define Research Objective:

- Choose a High Similarity (HS) Backbone to uncover a robust, cohesive core structure.

- Choose a Low Similarity (LS) Backbone to discover weak, peripheral, or unexpected connections.

2. Select a Similarity Function: Select one based on the scope of connections you wish to emphasize.

- Preferential Attachment (Local): Assumes nodes connect to well-connected nodes.

- Local Path Index (Quasi-local): Considers local paths of limited length.

- Shortest Path Index (Global): Uses the shortest path distance between nodes [2].

3. Calculate and Filter Edges:

- For all node pairs, calculate the similarity score using your chosen function.

- For each node, sort its edges by their similarity score.

- Retain a top percentage (e.g., top 20%) of a node's edges for an HS-backbone.

- Retain a bottom percentage (e.g., bottom 20%) of a node's edges for an LS-backbone [2].

4. Evaluate the Backbone: Quantitatively assess the extracted backbone against the original network using metrics like:

- Node fraction preserved

- Number of connected components

- Average clustering coefficient

- Degree entropy [2]

Quantitative Data on Backbone Extraction Methods

The following table summarizes the performance of different backbone extraction methods across 18 diverse networks, highlighting their key characteristics and trade-offs [2].

| Method Type | Specific Method | Key Characteristic | Node Preservation | Connectivity | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Similarity (HS) | Preferential Attachment | Emphasizes robust global links between major hubs [2] | Lower | Superior [2] | Identifying core hubs and robust global structures [2] |

| Shortest Path Index | Ensures efficient direct paths [2] | Lower | Superior [2] | Analyzing shortest-path routing and efficiency [2] | |

| Low Similarity (LS) | Preferential Attachment | Uncovers weak peripheral links [2] | Higher [2] | Struggles with fragmentation [2] | Finding weak ties that enhance regional connectivity [2] |

| Shortest Path Index | Identifies critical connections for isolated regions [2] | Higher [2] | Struggles with fragmentation [2] | Revealing vital long-range connectors [2] | |

| Traditional (Reference) | Disparity Filter (Statistical) | Filters based on significance of edge weights [2] | Similar to LS | Varies | General-purpose significance filtering [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Tool | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Apache Spark / Flink | Big data processing frameworks. Spark Streaming uses micro-batches, while Flink allows true stream processing for real-time network data analysis [3]. |

| Cloud Platforms (AWS, Google Cloud) | Provide scalable, on-demand computing power and storage for processing planet-scale datasets, such as those from genomic sequencing [5]. |

| Green Algorithms Calculator | A tool to estimate the carbon footprint of computational tasks, helping researchers make sustainable choices about their analyses [4]. |

| Similarity Functions (e.g., Preferential Attachment) | Predefined metrics used for backbone extraction and link prediction in networks. They compute the likelihood of a connection between nodes based on different assumptions [2]. |

| Single-Cell & Spatial Transcriptomics Tools | Technologies that allow genomic analysis at the level of individual cells and within the spatial context of tissues, revealing cellular heterogeneity and organization [5]. |

| AZPheWAS / MILTON Portals | Examples of open-access data portals that provide curated genomic resources, enabling researchers to make discoveries without repeating energy-intensive computations [4]. |

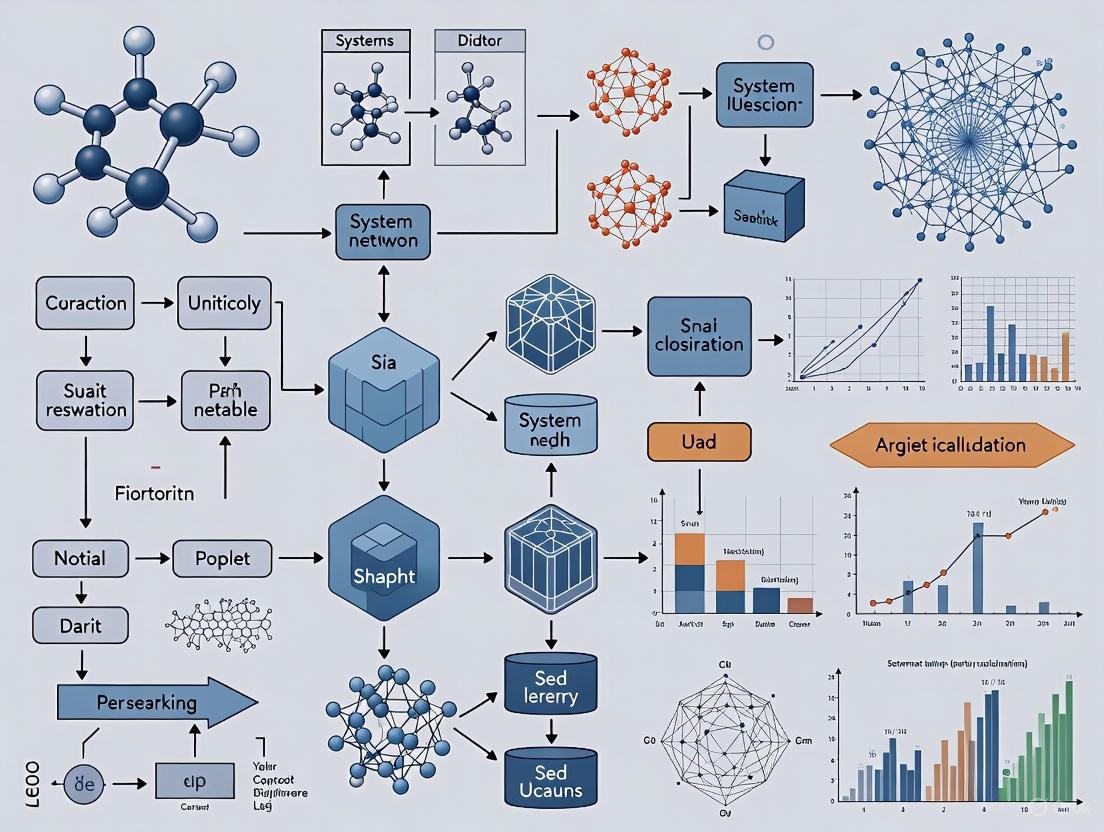

Workflow Visualizations

Network Backbone Extraction Workflow

Stream Processing for Network Data

This technical support center resource is framed within a broader thesis on computational challenges in large-scale network analysis research. It provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals identify and overcome common bottlenecks related to memory, computational complexity, and data sparsity in their computational experiments.

Troubleshooting Guides

Memory Bottlenecks

Problem: Applications crash or slow to a crawl when handling large networks, with high memory usage on individual compute nodes becoming a critical bottleneck, especially on modern high-performance computing (HPC) architectures with limited RAM per core [6].

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Diagnostic Step: Profile your simulator's memory consumption using a linear memory model to identify components contributing most to memory saturation [6].

- Solution: Implement sparse data structures that store only non-zero elements and their indices, drastically reducing memory footprint for zero-rich datasets [7].

- Advanced Solution: For brain-scale network simulations, optimize data structures to exploit the sparseness of the network's local representation and distribute data across thousands of processors [6].

Computational Complexity Bottlenecks

Problem: Graph Neural Network (GNN) training and inference times become prohibitively long, hampering research iteration cycles [8].

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Diagnostic Step: Decompose GNN training/inference time by layer and operator; edge-related calculations are often the primary bottleneck [8].

- Solution: For GNNs with high edge-calculation complexity, focus optimization on the messaging function for every edge. For those with low edge-complexity, optimize the collection and aggregation of message vectors [8].

- Advanced Solution: Adopt Compute-in-Memory (CIM) architectures that perform analog computations directly in memory, fundamentally reducing data movement and the von Neumann bottleneck for matrix multiplications dominant in transformer models [9].

Data Sparsity Bottlenecks

Problem: Analysis of large, sparse datasets (e.g., user interactions, sensor data, biological networks) is slow, making it difficult to complete analyses within practical timeframes [10].

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Diagnostic Step: Confirm that your dataset is indeed sparse (majority zeros/null values) and identify its structural format (e.g., group, network, hierarchical) [10].

- Solution: Use specialized sparse data structures like Compressed Sparse Row (CSR) for row-oriented operations or Compressed Sparse Column (CSC) for column-oriented operations, instead of standard dense arrays [7].

- Advanced Solution: Employ fast sparse modeling algorithms that use pruning to safely skip computations related to unnecessary information, accelerating analysis by up to 73x without accuracy loss [10].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My graph dataset is too large to fit into GPU memory for GNN training. What can I do? A: Sampling techniques are essential for this scenario. They create smaller sub-graphs for mini-batch training, significantly reducing memory usage. However, be aware that current sampling implementations can be inefficient; the sampling time may exceed training time, and small batch sizes can underutilize GPU compute power [8].

Q2: What is the single biggest factor limiting the scalability of neural network simulators on supercomputers? A: On modern supercomputers like Blue Gene/P, the limited RAM available per CPU core is often the critical bottleneck. As network models grow, serial memory overhead from data structures supporting network construction and simulation can saturate available memory, restricting maximum network size [6].

Q3: How can I make my large-scale data analysis both fast and interpretable? A: Sparse modeling techniques are ideal, as they select essential information from large datasets, providing high interpretability. For practical speed, use next-generation algorithms like Fast Sparse Modeling, which employ pruning to accelerate analysis without compromising accuracy [10].

Q4: What is the "von Neumann bottleneck" and how can it be overcome for AI workloads? A: The von Neumann bottleneck is the performance limitation arising from the physical separation of processing and memory units in classical computing architectures. Data movement between these units consumes more energy than computation itself [9]. Compute-in-Memory (CIM) is a promising solution, as it performs computations directly within memory arrays, drastically reducing data movement [9].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Objective: To empirically identify the most time-consuming and memory-intensive stages in GNN training and inference.

Materials: A GPU-equipped server, PyTorch Geometric (PyG) or Deep Graph Library (DGL), and representative GNN models (e.g., GCN, GAT).

Workflow:

- Model Selection & Implementation: Select GNNs representing different computational complexity quadrants (e.g., GCN for high-edge, GAT for high-vertex). Implement them using PyG.

- Decomposition: For each model, decompose the forward and backward passes to the operator level.

- Time Profiling: Use profiling tools (e.g., NVIDIA Nsight Systems) to measure the wall-clock time of each operator over multiple epochs, excluding outliers.

- Memory Profiling: Analyze memory usage during training/inference to identify layers and operators generating the largest intermediate results.

- Analysis: Correlate the empirical profiling data with the theoretical time complexity of the GNN's operations.

GNN Performance Profiling Workflow

Objective: To model, analyze, and reduce the memory consumption of a neuronal network simulator running at an extreme scale.

Materials: Neuronal simulator (e.g., NEST), supercomputing or large cluster environment.

Workflow:

- Model Formulation: Develop a linear memory model breaking down total memory consumption into base overhead, neuronal, and synaptic components:

ℳ(M,N,K) = ℳ₀(M) + ℳₙ(M,N) + ℳc(M,N,K). - Parameterization: Parameterize the model using a combination of theoretical analysis and empirical measurements from running the simulator at smaller scales.

- Component Identification: Use the model to identify which software components (e.g., neuronal infrastructure, connection infrastructure) are the dominant sources of memory consumption as the number of processes (M) increases.

- Optimization & Validation: Redesign data structures to exploit sparsity and reduce identified overheads. Validate the model's predictions by comparing them with memory consumption after optimizations at full scale.

Memory Consumption Analysis Workflow

Table 1: Sparse Data Structure Characteristics [7]

| Structure Name | Best For | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coordinate (COO) | Easy construction, incremental building | Simple to append new non-zero elements | Slow for arbitrary lookups and computations |

| Compressed Sparse Row (CSR) | Row-oriented operations (e.g., row slicing) | Efficient row access and operations | Complex to construct |

| Compressed Sparse Column (CSC) | Column-oriented operations | Efficient column access and operations | Complex to construct |

| Block Sparse (e.g., BSR) | Scientific computations with clustered non-zeros | Reduces indexing overhead, enables vectorization | Overhead if data doesn't fit blocks |

Table 2: Large-Scale Network Visualization Tool Scalability (circa 2017) [11]

| Tool | Maximum Recommended Scale (Nodes/Edges) | Recommended Layout for Large Networks |

|---|---|---|

| Gephi | ~300,000 / ~1,000,000 | OpenOrd, then Yifan-Hu |

| Tulip | Thousands of nodes / 100,000s of edges | (Information not specified in detail) |

| Pajek | (Information not specified in detail) | (Information not specified in detail) |

Table 3: Performance Improvements of Advanced Sparse Modeling [10]

| Technology | Key Innovation | Reported Speed-up | Supported Data Structures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fast Sparse Modeling | Pruning algorithm that skips unnecessary computations | Up to 73x faster than conventional algorithms | Group, Network, Hierarchical (Tree) |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Sparse Data Structures (COO, CSR, CSC) [7] | Efficiently store and manipulate large, primarily empty datasets in memory. |

| Compute-in-Memory (CIM) Architectures [9] | Accelerate AI inference by performing computations directly in memory, overcoming the von Neumann bottleneck. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Libraries (PyG, DGL) [8] | Provide high-level programming models and optimized kernels for developing and running GNNs. |

| Fast Sparse Modeling Algorithms [10] | Enable rapid, interpretable analysis of large datasets by selecting essential information with guaranteed acceleration. |

| Linear Memory Models [6] | Analyze and predict an application's memory consumption to identify and resolve scalability bottlenecks before implementation. |

| Sampling Techniques [8] | Enable GNN training on massive graphs by working on sampled sub-graphs, reducing memory requirements. |

SpGEMM Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is SpGEMM and how does it differ from other sparse matrix operations?

SpGEMM, or Sparse General Matrix-Matrix Multiplication, is the operation of multiplying two sparse matrices. It is distinct from other operations like SpMM (Sparse-dense Matrix-Matrix multiplication) and SDDMM (Sampled Dense-Dense Matrix Multiplication). In SpGEMM, both input matrices (A and X) are sparse, and the output (Y) can be sparse or dense, depending on its structure and the chosen representation [12]. This is a fundamental computational pattern in many data science and network analysis applications [12].

FAQ 2: In which network analysis applications is SpGEMM most critical?

SpGEMM is a foundational operation in numerous network analysis applications, including [12]:

- Graph Algorithms: It is used in algorithms for traversing and analyzing graph structures.

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): It facilitates message passing between nodes.

- Clustering: It helps identify communities or modules within a network.

- Computational Biology and Chemistry: It is used for many-to-many comparisons of biological sequencing data and analyzing molecular structures.

FAQ 3: My SpGEMM operation is unexpectedly slow. What are the primary factors affecting its performance?

Performance is primarily influenced by the compression ratio, which is the ratio of the number of nontrivial arithmetic operations (where both corresponding elements in the input matrices are non-zero) to the number of non-zeroes in the output matrix [12]. A high ratio can indicate more computational work. Other factors include the sparsity pattern of the input matrices and the underlying hardware architecture. The operational intensity (FLOPs per byte of memory traffic) for SpGEMM is often lower than for SpMM, making it more challenging to achieve high performance [12].

FAQ 4: How do I choose between a sparse or dense representation for the output matrix?

The choice depends on the density (fill-in) of the output. If the resulting matrix is also sparse, a sparse representation saves memory. However, if the multiplication results in a densely populated matrix, a dense representation may be more computationally efficient. Tools and libraries implementing the Sparse BLAS or GraphBLAS standards (e.g., GrB_mxm) often handle this representation decision internally based on heuristics [12].

FAQ 5: Can SpGEMM be performed using non-standard arithmetic, like max-plus algebra?

Yes. SpGEMM can be generalized to operate over an arbitrary algebraic semiring [12]. This means the standard + and × operations can be overloaded with other functions, such as max and +, as long as they adhere to the semiring properties. This flexibility allows SpGEMM to model a wide range of network problems, like finding shortest paths.

SpGEMM Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Memory Usage During SpGEMM

Problem: The computation consumes an unexpectedly large amount of memory, potentially causing termination.

Solution:

- Pre-allocate Output Memory: Use a symbolic phase to estimate the number of non-zeroes in the output matrix (

C) before the numeric multiplication. This allows for precise memory allocation. - Check Compression Ratio: A high compression ratio often leads to a dense output. Consider the following metrics [12]:

| Metric | Description | Indicator of High Memory Use |

|---|---|---|

| Compression Ratio | (Sparse FLOPs) / (nnz(C)) [12] |

Ratio >> 1 suggests high computational load relative to output size. |

| Output Density | nnz(C) / (M * N) |

A value approaching 1.0 indicates a nearly dense output. |

- Matrix Partitioning: For very large matrices, use distributed memory algorithms (e.g., 2D or 3D decomposition) to partition the problem across multiple compute nodes [12].

Issue 2: Incorrect Results with Custom Semirings

Problem: The output of the SpGEMM operation does not match the expected mathematical result when using a user-defined semiring.

Solution:

- Verify Semiring Properties: Ensure your custom operators form a valid semiring. For example, the "addition" operator must be associative and commutative, and the "multiplication" operator must be associative. Furthermore, the multiplication must distribute over addition.

- Check Identity Elements: Confirm that the identity elements for both your additive and multiplicative operations are implemented correctly. The default values (often

0and1) may not be appropriate. - Validate Operator Functions: Isolate and unit-test the kernel functions that perform the elemental addition and multiplication to ensure they are bug-free.

Issue 3: Performance Inconsistencies Across Different Networks

Problem: SpGEMM performance varies significantly when applied to different types of network topologies (e.g., social networks vs. road networks).

Solution:

- Profile Sparsity Patterns: Different networks have distinct sparsity structures (e.g., scale-free, mesh-like). Algorithms optimized for one pattern may perform poorly on another.

- Match Algorithm to Topology: Select an SpGEMM algorithm suited to your matrix's structure. The table below summarizes how network model properties can influence analysis, which in turn affects the matrices used in SpGEMM [13].

| Network Model | Key Structural Property | SpGEMM Performance Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Erdős-Rényi (ER) | Random, uniform edge distribution. | Performance is often predictable and stable. |

| Barabási-Albert (BA) | Scale-free with hub nodes [13]. | Output may have irregular sparsity, challenging load balancing. |

| Stochastic Block Model (SBM) | High modularity (community structure) [13]. | Blocked algorithms can be highly effective. |

Experimental Protocols for Network Analysis with SpGEMM

Protocol 1: Network Neighborhood Aggregation (K-Hop)

This is a core operation for gathering information about a node's local environment.

Workflow Diagram:

Methodology:

- Input: A network's adjacency matrix

A(sparse) and an integerkfor the number of hops. - Compute Powers: Use SpGEMM to compute the higher powers of the adjacency matrix (

A^2,A^3, ...,A^k). The non-zero entries inA^kindicate the existence of a path of length exactlykbetween two nodes. - Aggregate: Combine the matrices up to

k(e.g., by summing them) to create a single matrix that represents all connections withinkhops.

Protocol 2: Co-occurrence Analysis (Similarity Network Construction)

This protocol measures how often pairs of entities appear together in a context, common in biological and social network analysis.

Workflow Diagram:

Methodology:

- Input: A binary association matrix

M(sparse), where rows represent one entity type (e.g., genes) and columns represent another (e.g., patients). An entryM[i,j] = 1indicates an association. - Transpose: Compute the transpose of the matrix,

M^T. - Multiply: Perform SpGEMM to compute the similarity matrix

S = M * M^T. The entryS[i,k]now holds the number of common associations between entityiand entityk(e.g., the number of patients in which both genes were present). This is a fundamental pattern for inferring networks from observation data [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function in SpGEMM / Network Analysis |

|---|---|

| Sparse BLAS Libraries | Provides standardized, high-performance implementations of SpGEMM and related operations (e.g., Intel MKL, oneMKL) [12]. |

| GraphBLAS API | A higher-level abstract programming interface (GrB_mxm) that allows for flexible definition of semirings and masks, separating semantics from implementation [12]. |

| Synthetic Network Generators | Tools to generate networks from models like Erdős-Rényi, Barabási-Albert, and Stochastic Block Models for controlled benchmarking and validation [13]. |

| Compression Ratio Analyzer | A tool or script to estimate the compression ratio before full SpGEMM execution, aiding in performance prediction and resource allocation [12]. |

| Distributed-Memory SpGEMM | Libraries (e.g., CTF, CombBLAS) that implement 1.5D/2D algorithms for scaling SpGEMM to massive networks that do not fit on a single machine [12]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common computational bottlenecks in target identification? The most common bottlenecks involve handling high-dimensional data and lengthy processing times. Methods like traditional Support Vector Machines (SVMs) and XGBoost can struggle with large, complex pharmaceutical datasets, leading to inefficiencies and overfitting [14]. Furthermore, 3D convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for binding site identification, while accurate, are computationally intensive [14].

2. How does data quality from real-world sources (like EHRs) specifically impact pathway analysis? The principle of "garbage in, garbage out" is paramount. Poor quality input data, such as unstructured clinical notes or unvalidated molecular profiling, directly leads to misleading Pathway Enrichment Analysis (PEA) results [15] [16]. Confounding factors and biases inherent in Real-World Data (RWD) can skew analysis, requiring advanced Causal Machine Learning (CML) techniques to mitigate, which themselves introduce computational overhead [17].

3. My enrichment analysis results are inconsistent. What could be the cause? Inconsistencies often stem from using an inappropriate analysis type for your data. A key distinction exists between Overrepresentation Analysis (ORA), which uses a simple gene list, and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA), which uses a ranked list [15]. Using ORA with data that requires a ranked approach can produce unstable results. Always clarify your scientific question and data type before selecting a tool [15].

4. Are there strategies to make large-scale network analysis more computationally feasible? Yes, strategies include leveraging optimized algorithms and efficient computational frameworks. For instance, the optSAE + HSAPSO framework for drug classification was designed to reduce computational complexity, achieving a processing time of 0.010 seconds per sample [14]. For network analysis, using tools that employ advanced optimization techniques can significantly improve convergence speed and stability [14].

5. What are the key validation challenges when using computational models for target discovery? A significant challenge is the absence of standardized validation protocols for models, especially those using RWD and CML [17]. Furthermore, models can suffer from poor generalizability to unseen data and a lack of transparency ("black box" problem), making it difficult to trust and validate their predictions for critical decision-making [17] [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Long Processing Times for Large-Scale Molecular Profiling Data

Issue: Whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing data from high-risk pediatric cancer cases takes too long to process for actionable target identification [18].

Diagnosis: This is a classic computational scalability issue. Traditional analysis pipelines may not be optimized for high-throughput, genome-scale data.

Solution:

- Implement Automated Prioritization: Use computational decision support systems like Digital Drug Assignment (DDA), which automatically aggregate evidence to prioritize treatment options, streamlining the interpretation of extensive molecular data [18].

- Optimize Feature Extraction: Employ deep learning frameworks like Stacked Autoencoders (SAE) for efficient, non-linear feature extraction from high-dimensional data, which can reduce computational overhead [14].

- Leverage Evolutionary Optimization: Integrate algorithms like Hierarchically Self-Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization (HSAPSO) to dynamically adapt model parameters, improving convergence speed and stability during analysis [14].

Problem 2: Inaccurate or Biased Results from Observational Real-World Data

Issue: Drug effect estimates from electronic health records (EHRs) are confounded by patient heterogeneity, comorbidities, and treatment histories [17] [16].

Diagnosis: The observational nature of RWD means it lacks the controlled randomization of clinical trials, introducing confounding variables and bias [17].

Solution:

- Apply Causal Machine Learning (CML): Use advanced methods to strengthen causal inference.

- Advanced Propensity Score Modeling: Replace traditional logistic regression with machine learning models (e.g., boosting, tree-based models) to better handle non-linearity and complex interactions when estimating propensity scores [17].

- Doubly Robust Methods: Combine outcome and propensity models using techniques like Targeted Maximum Likelihood Estimation to enhance the validity of causal estimates [17].

- Ensure Data Quality: Build analysis-ready, disease-specific registries from RWD that are deeply curated and harmonized across multiple sites to provide a more representative view of disease biology [16].

Problem 3: Incorrect Pathway Enrichment Results

Issue: Pathway enrichment analysis yields biologically implausible or non-reproducible results.

Diagnosis: This is frequently caused by incorrect tool selection or poor-quality input data [15].

Solution:

- Select the Correct Analysis Type: Before starting, clarify your goal and data type.

- Use Overrepresentation Analysis (ORA) for simple, non-ranked gene lists (e.g., using tools like g:Profiler g:GOSt or Enrichr) [15].

- Use Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) for ranked gene lists (e.g., using the GSEA tool from UCSD/Broad Institute) to identify pathways enriched at the extremes of your ranking [15].

- Validate Input Gene List Quality: Meticulously curate your input gene list to ensure gene identifiers are correct and consistent. Poor input quality guarantees poor output [15].

- Consider Topology: For more precise results, use Topology-based PEA (TPEA) tools that account for interactions between genes and gene products, though be aware their topologies may be incomplete [15].

The following workflow summarizes a robust computational strategy that integrates these troubleshooting principles to overcome common limitations:

Problem 4: Inefficient Handling of Large Biological Networks

Issue: Analysis of protein-protein interaction or co-expression networks becomes intractable due to memory and processing constraints.

Diagnosis: Network analysis algorithms may not scale efficiently to billion-edge graphs, and hardware limitations can be a factor.

Solution:

- Use Efficient Algorithms: Seek out tools and libraries specifically designed for large-scale data network computing and billion-scale network analysis [19].

- Employ Representation Learning: Apply representation learning on networks (e.g., node embeddings) to create lower-dimensional representations of the network that are easier and faster to analyze [19].

- Leverage Multidimensional Graph Analysis: Utilize frameworks that support multidimensional graph analysis to efficiently model and query complex biological relationships [19].

Performance Data of Computational Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Drug Target Identification Methods. This table summarizes the performance and limitations of various approaches, highlighting the trade-offs between accuracy and computational demand.

| Method / Framework | Reported Accuracy | Key Computational Challenge / Limitation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| optSAE + HSAPSO | 95.52% | Performance is dependent on the quality of training data; requires fine-tuning for high-dimensional datasets. | [14] |

| Digital Drug Assignment (DDA) | Identified actionable targets in 72% of pediatric cancer cases (n=100) | Interpretation of extensive molecular profiling; filtering WES results can miss important mutations. | [18] |

| SVM/XGBoost (DrugMiner) | 89.98% | Struggles with large, complex datasets; can suffer from inefficiencies and limited scalability. | [14] |

| 3D Convolutional Neural Network | High accuracy for binding site identification | Computationally intensive for large-scale structural predictions. | [14] |

| Causal ML on RWD | Enables robust drug effect estimation | Challenges related to data quality, computational scalability, and the absence of standardized validation protocols. | [17] |

Table 2: Key computational tools and databases for target identification and pathway analysis, with their primary functions.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway Tools / BioCyc | Database & Software Platform | Provides pathway/genome databases for searching, visualizing, and analyzing metabolic and signaling pathways. | [20] |

| g:Profiler g:GOSt | Web Tool | Performs functional enrichment analysis (ORA) on unordered or ranked gene lists to identify overrepresented pathways. | [15] |

| GSEA | Software Tool | Performs Gene Set Enrichment Analysis on ranked gene lists to identify pathways enriched at the top or bottom of the list. | [15] |

| Enrichr | Web Tool | A functional enrichment analysis web tool used for gene set enrichment analysis. | [15] |

| Cytoscape | Software Platform | An open-source platform for visualizing complex molecular interaction networks and integrating with other data. | [21] |

| Connectivity Map | Database & Tool | A collection of gene-expression profiles from cultured cells treated with drugs, enabling discovery of functional connections. | [21] |

| DrugBank | Database | A comprehensive database containing detailed drug and drug target information. | [14] |

| Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) | Database | Contains metabolite data with chemical, clinical, and molecular biology information for metabolomics and biomarker discovery. | [21] |

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for a computational target identification project, integrating many of the tools and resources listed above, and pinpointing where computational limits often manifest.

AI and HPC Solutions: Advanced Methodologies for Biomedical Network Applications

Leveraging Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for Protein Interaction and Disease Gene Prediction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most effective GNN architectures for PPI prediction, and how do their performances compare? Comparative studies show that various GNN architectures excel at predicting protein-protein interactions. The choice of model often depends on the specific dataset and task, such as identifying interfaces between complexes or within single chains. The table below summarizes the performance of different models from recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of GNN Models for PPI Prediction

| Model / Dataset | Accuracy | Balanced Accuracy | F-Score | AUC | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HGCN (Hyperbolic GCN) [22] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Superior performance on protein-related datasets; general PPI prediction. |

| GNN (Whole Dataset) [23] | 0.9467 | 0.8946 | 0.8522 | 0.9794 | Identifying interfaces between protein complexes. |

| GNN (Interface Dataset) [23] | 0.9610 | 0.8880 | 0.8262 | 0.9793 | Identifying interfaces between chains of the same protein. |

| GNN (Chain Dataset) [23] | 0.8335 | 0.7717 | 0.6025 | 0.8679 | Identifying interface regions on single chains. |

| Graph Autoencoder (GAE) [24] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Link prediction for disease-gene associations. |

| XGDAG (GraphSAGE) [25] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Explainable disease gene prioritization using a PU learning strategy. |

FAQ 2: My model performs well on benchmark PPI datasets but fails on my specific protein data. What could be wrong? This is a common challenge in large-scale network analysis, often related to data distribution shifts. The PPI prediction problem can be framed in several ways, and your internal data might align better with a different experimental setup.

- Check the Task Formulation: The "Chain" dataset task, which involves identifying interface regions on a single chain without information about a binding partner, is the most challenging and shows lower performance (F-Score of 0.6025) [23]. If your data lacks partner information, this could explain the performance drop.

- Evaluate Feature Completeness: Your internal data might lack certain structural or evolutionary features that the pre-trained model relies on. Ensure your node and edge features (e.g., sequence, structure, physico-chemical properties) are comparable to those used in benchmark studies [23].

- Consider Data Scarcity: For specific protein families, the public datasets may be under-represented. Techniques like positive-unlabeled (PU) learning, used in gene-disease association prediction, can be adapted to leverage your unlabeled data [25].

FAQ 3: How can I add explainability to my GNN model for disease-gene association prediction? The XGDAG framework provides a methodology for explainable gene-disease association discovery [25].

- Leverage Explainable AI (XAI) Tools: After training a model like GraphSAGE, use GNN explainability methods to determine which parts of the network (e.g., neighboring genes in the PPI) were most influential in predicting an association.

- Active Explanation for Discovery: Unlike using XAI as a passive justification tool, XGDAG actively uses the explanation subgraphs to extract new candidate genes. Genes that frequently appear in the explanation subgraphs for known disease-associated genes ("seed genes") are prioritized, following the connectivity significance principle [25].

FAQ 4: What is the best way to handle the positive-unlabeled (PU) scenario in disease-gene discovery? Directly treating unlabeled genes as negatives can introduce significant bias. A robust solution involves a multi-step process:

- Label Propagation: Use a method like NIAPU to assign pseudo-labels to unlabeled genes. This process uses a Markovian diffusion on the network to categorize genes into classes like "Likely Positive," "Weakly Negative," and "Reliably Negative" based on their topological features [25].

- Model Training: Train your GNN model (e.g., GraphSAGE) using these propagated pseudo-labels, which provides a more balanced and reliable learning signal than a simple positive/negative split [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model performance is poor on a node-level PPI interface prediction task.

Table 2: Troubleshooting PPI Interface Prediction

| Symptoms | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Recall for interface residues. | Model cannot distinguish interface topology from the broader protein structure. | Use a GNN architecture that captures long-range dependencies in the protein graph. Ensure node/edge features include structural information like solvent accessibility [23]. |

| Low Precision for interface residues. | Model is over-predicting interfaces; class imbalance issue. | Use the "Balanced Accuracy" metric for a clearer picture. Employ weighted loss functions or undersampling of the majority (non-interface) class during training [23]. |

| High performance on validation split but poor performance on test proteins. | Data leakage or overfitting to specific protein folds in the training set. | Ensure a strict separation between proteins in the training and test sets (hold-out by protein, not by residue). Apply regularization techniques like dropout in the GNN [24]. |

Experimental Protocol: Node-Level PPI Interface Prediction [23]

- Data Acquisition: Obtain protein complex structures from the Protein Data Bank in Europe (PDBe), using the PISA (Protein Interfaces, Surfaces, and Assemblies) service to define interface residues.

- Graph Construction:

- Nodes: Represent amino acid residues.

- Edges: Connect residues based on spatial proximity (e.g., Euclidean distance between Cα atoms below a threshold like 10Å) or atomic interactions.

- Node Features: Include residue type (one-hot encoding), secondary structure, solvent accessibility, physico-chemical properties, and evolutionary information from position-specific scoring matrices (PSSMs).

- Edge Features: Can include distance and type of interaction.

- Model Training:

- Task: Frame as a binary node classification task (interface vs. non-interface).

- Architecture: Use a GNN model (e.g., GCN, GAT) with multiple layers to capture higher-order neighborhoods.

- Validation: Perform k-fold cross-validation, ensuring no protein overlap between folds.

Problem: The model fails to predict novel disease-gene associations.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Disease-Gene Association Prediction

| Symptoms | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Good reconstruction of training edges, no novel predictions. | The model is "overfitting" the existing graph and lacks generalization power. The graph autoencoder is simply memorizing. | Use a Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning strategy instead of treating all unlabeled genes as negatives [25]. Regularize the model using dropout. |

| Predictions are biased towards well-studied ("hub") genes. | Topological bias in the network; hub genes are connected everywhere. | Use the explainability phase in XGDAG to find genes connected to multiple seed genes through significant paths, not just the most connected ones [25]. |

Experimental Protocol: Disease-Gene Association with PU Learning and Explainability (XGDAG) [25]

- Data Integration:

- Network: Use a Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network from BioGRID.

- Gene-Disease Associations: Obtain known associations from DisGeNET. These are your positive labels. All other genes are considered unlabeled.

- Label Propagation (NIAPU):

- Calculate network-based features (e.g., Heat Diffusion, Balanced Diffusion) for each gene with respect to a specific disease.

- Use these features to propagate labels and assign pseudo-labels (Likely Positive, Reliably Negative, etc.) to the unlabeled genes.

- GNN Training & Explainability:

- Train a GraphSAGE model on the PPI network using the propagated labels.

- For a given disease, use GNN explainability methods on the trained model to generate explanation subgraphs for the known seed genes.

- Extract genes that appear in these explanation subgraphs as new, high-confidence candidate associations.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents & Resources

| Item Name | Type | Function / Description | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| BioGRID | Database | A curated biological database of protein-protein and genetic interactions. Used as the foundational network. | https://thebiogrid.org [25] |

| DisGeNET | Database | A platform integrating information on gene-disease associations from various sources. Used for positive labels and validation. | https://www.disgenet.org/ [25] |

| PDBe & PISA | Database & Tool | Protein Data Bank in Europe and its Protein Interfaces, Surfaces, and Assemblies service. Provides protein structures and defines interface residues. | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/pisa/ [23] |

| PyTorch Geometric (PyG) | Software Library | A library built upon PyTorch for deep learning on graphs. Provides easy-to-use GNN layers and datasets. | [24] |

| Graphviz | Software Tool | An open-source tool for visualizing graphs specified in the DOT language. Used for creating network diagrams and workflows. |

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

GNN for PPI Interface Prediction

Explainable Disease Gene Discovery

High-Performance Computational Frameworks for Multi-Omics Data Integration

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary computational challenges when integrating heterogeneous multi-omics datasets? A1: The key challenges include data heterogeneity, the "high-dimension low sample size" (HDLSS) problem, missing value imputation, and the need for appropriate scaling, normalization, and transformation of datasets from different omics modalities before integration can occur [26].

Q2: What is the difference between horizontal and vertical multi-omics data integration? A2: Horizontal integration combines data from different studies or cohorts that measure the same omics entities. Vertical integration combines datasets from different omics levels (e.g., genome, transcriptome, proteome) measured using different technologies, requiring methods that can handle greater heterogeneity [26].

Q3: How can researchers choose the most suitable integration strategy for their specific multi-omics analysis? A3: Strategy selection depends on the research question, data types, and desired output. Early Integration is simple but creates high-dimensional data. Mixed Integration reduces noise. Intermediate Integration captures shared and specific patterns but needs robust pre-processing. Late Integration avoids combining raw data but may miss inter-omics interactions. Hierarchical Integration incorporates prior biological knowledge about regulatory relationships [26].

Q4: What are the common pitfalls in network analysis of integrated multi-omics data, and how can they be avoided? A4: A major pitfall is the creation of networks that are computationally intractable due to scale. This can be mitigated by using effective feature selection or dimension reduction techniques during pre-processing to reduce network complexity before analysis begins [26].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue: Memory Overflow During Data Integration

- Problem: The integration process, particularly Early Integration, consumes all available RAM and fails.

- Solution:

- Pre-process Data: Apply stringent feature selection (e.g., variance-based filtering) to each omics dataset individually before integration.

- Use Batch Processing: If possible, break the dataset into smaller batches for integration.

- Increase Virtual Memory: Configure your computing environment to use more virtual memory, though this may slow processing.

- Shift Strategy: Consider using a Late or Mixed Integration approach that does not require concatenating all data into a single, massive matrix [26].

Issue: Poor Integration Performance or Inaccurate Models

- Problem: The integrated model performs poorly on test data or produces biologically inconsistent results.

- Solution:

- Check for Data Leakage: Ensure that normalization and imputation procedures are performed separately on training and test datasets.

- Address Overfitting: With HDLSS data, use regularized machine learning models and ensure rigorous cross-validation.

- Validate Biologically: Use pathway enrichment analysis or compare with known molecular interactions to assess the biological plausibility of results [26].

Issue: Handling Missing Data in Multi-Omics Datasets

- Problem: A significant number of missing values in one or more omics datasets hampers integration.

- Solution:

- Assess Patterns: Determine if data is Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) or not, as this influences the imputation method.

- Apply Imputation: Use sophisticated imputation algorithms (e.g., k-nearest neighbors (KNN), matrix factorization, or multi-omics-specific methods like MINT) to infer missing values.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Run the analysis with and without heavily imputed datasets to ensure the robustness of key findings [26].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementation of Mixed Integration for Classification

Objective: To classify patient samples (e.g., disease vs. control) using a Mixed Integration strategy on transcriptomics and metabolomics data.

Data Pre-processing:

- Normalize each omics dataset (transcriptomics, metabolomics) independently using platform-appropriate methods (e.g., TPM for RNA-Seq, Pareto scaling for metabolomics).

- Perform log-transformation where necessary to stabilize variance.

- Apply feature selection (e.g., removing low-variance features, using DESeq2 for differential expression) to each dataset.

Dimensionality Reduction:

- Independently transform each pre-processed omics matrix into a lower-dimensional space using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or non-linear methods like UMAP.

- Retain the top N components that explain a pre-defined percentage of the variance (e.g., 90%).

Data Integration & Modeling:

- Concatenate the reduced-dimension matrices from all omics types to form a unified feature table.

- Use this combined matrix to train a supervised classifier (e.g., Support Vector Machine, Random Forest).

- Evaluate model performance using a held-out test set or nested cross-validation, reporting metrics like AUC, accuracy, and F1-score [26].

Protocol 2: Network-Based Integration Using Hierarchical Methods

Objective: To construct a multi-omics regulatory network that captures interactions between genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics data.

Prior Knowledge Incorporation:

- Compile a list of known relationships from databases (e.g., protein-protein interactions from STRING, transcription factor-target gene interactions from ENCODE or CHEA).

Omics-Specific Network Construction:

- For each omics layer, compute association networks (e.g., co-expression networks for transcriptomics).

- Use correlation measures (e.g., Spearman, WGCNA) or information-theoretic measures (e.g., mutual information) to define edges.

Hierarchical Integration:

- Use the prior knowledge to constrain the integration process. For example, only allow edges between a transcription factor (protein node) and its known target genes (transcript nodes) if supported by the transcriptomics and proteomics association data.

- Employ a tool like iOmicsPASS or MOFA for structured, hierarchical integration.

Network Analysis:

- Identify highly connected "hub" nodes in the integrated network.

- Perform functional enrichment analysis on network modules to extract biological insights [26].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Vertical Multi-Omics Data Integration Strategies

| Strategy | Description | Advantages | Limitations | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration | Raw or pre-processed datasets are concatenated into a single matrix [26]. | Simple to implement [26]. | Creates a high-dimensional, noisy matrix; discounts data distribution differences [26]. | Exploratory analysis with few, similarly scaled omics layers. |

| Mixed Integration | Datasets are transformed separately, then combined for analysis [26]. | Reduces noise and dimensionality; handles dataset heterogeneity [26]. | May require tuning of transformation for each data type. | Projects where maintaining some data structure is beneficial. |

| Intermediate Integration | Simultaneously integrates datasets to find common and specific factors [26]. | Can capture shared and unique signals across omics types [26]. | Requires robust pre-processing; can be computationally intensive [26]. | Identifying latent factors driving variation across all omics types. |

| Late Integration | Each omics dataset is analyzed separately; results are combined [26]. | Avoids challenges of combining raw data; uses state-of-the-art single-omics tools. | Does not directly capture inter-omics interactions [26]. | When leveraging powerful single-omics models is a priority. |

| Hierarchical Integration | Incorporates prior known regulatory relationships between omics layers [26]. | Truly embodies trans-omics analysis; produces biologically constrained models [26]. | Still a nascent field; methods can be less generalizable [26]. | Hypothesis-driven research with strong prior biological knowledge. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Computational Experiments

| Item / Tool | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| HYFTs Framework | A proprietary system that tokenizes biological sequences into a common data language, enabling one-click normalization and integration of diverse omics and non-omics data [26]. |

| Plixer One | A monitoring tool that provides detailed visibility into network traffic and performance, crucial for diagnosing issues in cloud, hybrid, and edge computing environments used for large-scale analysis [27]. |

| MindWalk Platform | A platform that provides instant access to a pangenomic knowledge database, facilitating the integration of public and proprietary omics data for analysis [26]. |

| Software-Defined Networking (SDN) | Provides a flexible, programmable network infrastructure that allows researchers to dynamically manage data flows and computational resources in a high-performance computing cluster [28]. |

| Intent-Based Networking | Uses automation and analytics to align network operations with business (or research) intent, ensuring that the computational network self-configures and self-optimizes to meet the demands of data-intensive multi-omics workflows [28]. |

Visualizations

Multi-Omics Integration Strategies

Multi-Omics Network Analysis

Data Integration Challenge Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary data preparation bottleneck in large-scale genome sequence analysis, and how does SAGE address it? A1: In large-scale genome analysis, a major bottleneck occurs when genomic sequence data stored in compressed form must be decompressed and formatted before specialized accelerators can process it. This data preparation step greatly diminishes the benefits of these accelerators. SAGE mitigates this through a lightweight algorithm-architecture co-design. It enables highly-compressed storage and high-performance data access by leveraging key genomic dataset properties, integrating a novel (de)compression algorithm, dedicated hardware for lightweight decompression, an efficient storage data layout, and interface commands for data access [29].

Q2: My genomic accelerator isn't achieving expected performance improvements. Could data preparation be the issue? A2: Yes, this is a common issue. State-of-the-art genome sequence analysis accelerators can be severely limited by the data preparation stage. Relying on standard decompression tools creates a significant bottleneck. Integrating SAGE, which is designed for versatility across different sequencing technologies and species, can directly address this. It is reported to improve the average end-to-end performance of accelerators by 3.0x–32.1x and energy efficiency by 13.0x–34.0x compared to using state-of-the-art decompression tools [29].

Q3: How do I classify my data-intensive workload to select the appropriate memory and storage configuration? A3: Based on characterization studies, data-intensive workloads can be grouped into three main categories [30]:

- I/O Bound: Workloads like Hadoop operations. Performance is not significantly affected by DRAM specifications (capacity, frequency, number of channels).

- Compute Bound or Memory Bound: Iterative tasks, such as machine learning in Spark and MPI. These benefit from high-end DRAM, particularly higher frequency and more channels. It's crucial to profile your workload, as using SSDs alone may not shift the bottleneck from storage to memory but can change the workload's behavior from I/O bound to compute bound [30].

Q4: What are the key architectural principles of Computational Storage Devices (CSDs) and Near-Memory Computing relevant to network analysis? A4: CSDs and Near-Memory Computing architectures, such as In-Storage Computing (ISC) and Near Data Processing (NDP), aim to process data closer to where it resides. This paradigm reduces the need to move large volumes of data across the network to the central processor, which is a critical advantage for memory-intensive network analysis tasks. By performing computations within or near storage devices (like SSDs), these architectures help alleviate data movement bottlenecks and improve overall system performance and efficiency for high-performance applications [31].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem Scenario | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slow end-to-end processing speed with a genome analysis accelerator. | Data preparation bottleneck: inefficient decompression and data formatting. | 1. Measure time spent on data decompression vs. core analysis.2. Check compression ratio of input data. | Integrate a co-design solution like SAGE for streamlined decompression and data access [29]. |

| Unexpectedly low performance when running iterative, machine learning tasks on a cluster. | Inadequate memory subsystem for memory/compute-bound workloads. | 1. Profile workload to classify as I/O, memory, or compute-bound.2. Monitor DRAM channel utilization and frequency. | Upgrade to high-end DRAM with higher frequency and more channels for memory-bound workloads [30]. |

| High data transfer latency impacting analysis of large network traffic logs. | Data movement bottleneck between storage and CPU. | 1. Use monitoring tools to track data transfer volumes and times.2. Check storage I/O utilization. | Explore architectures that use Computational Storage Devices (CSDs) for near-data processing [31]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Performance Improvement of SAGE over Standard Decompression Tools [29]

| Metric | Improvement Range |

|---|---|

| End-to-End Performance | 3.0x – 32.1x |

| Energy Efficiency | 13.0x – 34.0x |

Table 2: Workload Classification and Hardware Sensitivity [30]

| Workload Type | Example Frameworks | Sensitive to DRAM Capacity? | Sensitive to DRAM Frequency/Channels? |

|---|---|---|---|

| I/O Bound | Hadoop | No | No |

| Memory/Compute Bound | Spark (ML), MPI | Yes | Yes |

Protocol: Workload Characterization for Memory-Intensive Networks

- Tool Selection: Choose profiling tools suitable for your framework (e.g., Hadoop, Spark).

- Baseline Measurement: Run the workload on a system with low-end DRAM and HDD storage. Record execution time and resource utilization (CPU, I/O, memory).

- Hardware Iteration: Repeat the experiment on a system with high-end DRAM (increased frequency and channels).

- Storage Iteration: Run the experiment again, replacing HDD with high-speed SSDs (e.g., PCIe SSD).

- Bottleneck Analysis: Compare the results from steps 2-4. If performance improves significantly with better DRAM (step 3), the workload is likely memory-bound. If performance improves mainly with better storage (step 4), it is I/O-bound. If neither change yields significant gains, the workload may be compute-bound [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for a SAGE-like Co-Design Experiment

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Genomic-specific Compressor/Decompressor | To maintain high compression ratios comparable to specialized algorithms while enabling fast data access [29]. |

| Lightweight Hardware Decompression Module | To perform decompression with minimal operations and enable efficient streaming of data to the accelerator [29]. |

| Optimized Storage Data Layout | To structure compressed genomic data on storage devices for efficient retrieval and processing by the co-designed hardware [29]. |

| High-Frequency, Multi-Channel DRAM | To provide the necessary bandwidth for memory-bound segments of data-intensive workloads [30]. |

| PCIe SSD Storage | To reduce I/O bottlenecks and potentially shift workload behavior, allowing compute bottlenecks to be identified and addressed [30]. |

| Computational Storage Device (CSD) | To perform processing near data, reducing the data movement bottleneck in large-scale analysis tasks [31]. |

Architectural Diagrams

Diagram 1: SAGE Co-Design Architecture for Genomic Data Analysis

Diagram 2: Workload Characterization and Bottleneck Identification

Technical FAQs: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: How do I resolve low hit rates and poor predictive accuracy in my virtual screening workflow?

Low hit rates often stem from inadequate data quality or incorrect model configuration. Follow this methodology to diagnose and resolve the issue:

Action 1: Audit Your Training Data.

- Problem: Models trained on small, biased, or noisy datasets will not generalize well to new chemical space.

- Solution: Use the QSAR model validation checklist below. Ensure your data comes from consistent, high-throughput screening (HTS) assays and is curated for chemical duplicates and errors. Incorporate negative (inactive) data to reduce false positives [32] [33].

Action 2: Validate Feature Selection and Model Parameters.

- Problem: Irrelevant molecular descriptors or suboptimal hyperparameters skew results.

- Solution: Perform feature importance analysis. For graph neural networks, ensure the node/edge feature representation (e.g., atom type, bond type) is appropriate for your biological context. Systematically tune hyperparameters using a validation set [33].

Action 3: Recalibrate against a Known Benchmark.

- Problem: It's impossible to know if your model's performance is acceptable without a baseline.

- Solution: Test your pipeline on a public benchmark with known outcomes, like the use case where a virtual screen for tyrosine phosphatase-1B inhibitors achieved a ~35% hit rate, vastly outperforming a traditional HTS screen (0.021%) [32]. Compare your model's performance on this benchmark to isolate the problem.

Table: QSAR Model Validation Checklist

| Checkpoint | Target Metric | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Training Data Size | > 5,000 unique compounds | Ensure sufficient data for model generalization [33] |

| Test Set AUC-ROC | > 0.8 | Discriminate between active and inactive compounds [33] |

| Cross-Validation Consistency | Q² > 0.6 | Verify model stability and predictive reliability [32] |

| Applicability Domain Analysis | Defined similarity threshold | Identify compounds for which predictions are unreliable [32] |

FAQ 2: Our heterogeneous network is visually cluttered and uninterpretable. What layout and visualization strategies should we use?

This is a classic challenge in large-scale network analysis. The solution involves choosing the right visual representation for your data density and message.

Action 1: Switch from a Node-Link to an Adjacency Matrix for Dense Networks.

- Problem: Node-link diagrams with thousands of edges become a "hairball," obscuring all structure.

- Solution: For dense networks, use an adjacency matrix. Rows and columns represent nodes, and a filled cell represents an edge. This layout excels at revealing clusters and edge patterns without clutter and allows for easy display of node labels [34].

Action 2: Apply Intentional Spatial Layouts in Node-Link Diagrams.

- Problem: A random or force-directed layout can create unintended spatial groupings that mislead interpretation.

- Solution: Use a layout algorithm that aligns with your story.

- Use force-directed layouts to group conceptually related nodes based on connectivity strength [34].

- Use multidimensional scaling (MDS) if the primary goal is cluster detection [34].

- Position the most critical node (e.g., a core disease pathway) at the center to leverage the "centrality" design principle [34].

Action 3: Ensure Legible Labels and Use Color Effectively.

- Problem: Labels are too small to read, or color schemes are misleading.

- Solution: Font size for labels should be the same as or larger than the figure caption. If labels cannot be legibly placed, provide a high-resolution, zoomable version online. Use color to show node or edge attributes, choosing sequential schemes for continuous data (e.g., expression levels) and divergent schemes to emphasize extremes (e.g., fold change) [34].

FAQ 3: Our Graph Neural Network (GNN) fails to learn meaningful representations for link prediction. What are the potential causes?

GNN performance is highly dependent on the quality and structure of the input graph.

Action 1: Inspect and Refine the Graph Schema.

- Problem: The heterogeneous graph is missing critical node or edge types, or edges lack directionality and sign, which flattens biological meaning.

- Solution: Adopt an expert-guided approach to graph construction. For example, the DeepDrug framework creates a signed directed heterogeneous biomedical graph, incorporating edge directions (e.g., protein A activates protein B) and signs (activation vs. inhibition). This captures crucial pathway logic that a simple association graph misses [35].

Action 2: Implement Node and Edge Weighting.

- Problem: All relationships in the graph are treated as equally important.

- Solution: Incorporate domain knowledge through weighting. Assign higher weights to edges with strong experimental evidence (e.g., high drug-target affinity) or to nodes with known importance in the disease pathology. This guides the GNN's attention to more reliable information [35].

Action 3: Verify the Encoder and Loss Function.

- Problem: The model architecture is not suitable for the task.

- Solution: For drug repurposing framed as a link prediction task, use a dedicated graph autoencoder or a GNN like DeepDrug's signed directed GNN, which is designed to encode the complex relationships into a meaningful embedding space. Ensure your loss function is appropriate for your task, such as a margin-based ranking loss for link prediction [35].

Experimental Protocol: The DeepDrug Methodology for Alzheimer's Disease

The following is a detailed protocol for the AI-driven drug repurposing methodology as implemented in the DeepDrug study, which identified a five-drug combination for Alzheimer's Disease (AD) [35].

Phase 1: Expert-Guided Biomedical Knowledge Graph Construction

- Objective: To build a signed, directed, and weighted heterogeneous graph that accurately encapsulates the complex biology of AD.

- Materials & Steps:

- Node Collection: Assemble nodes of multiple types:

- Genes/Proteins: Extend beyond canonical AD targets (e.g., APP) to include genes associated with neuroinflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and aging. Specifically incorporate "long genes" and somatic mutation markers linked to AD.

- Drugs: Source from approved drug banks (e.g., FDA-approved).

- Diseases: Include AD and related comorbidities.

- Pathways: Add pathways from databases like KEGG and Reactome.

- Edge Establishment: Create edges with specific types, directions, and signs:

- Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs): Define direction (e.g., signaling cascade) and sign (activates/inhibits).

- Drug-Target Interactions: Define the interaction as agonist (positive) or antagonist (negative).

- Disease-Gene Associations: Link diseases to associated genes.

- Drug-Disease Indications: Link drugs to their known treated diseases.

- Graph Weighting: Assign confidence scores to edges (e.g., based on affinity data or evidence level) and nodes (e.g., based on genetic association strength) to reflect biological credibility.

- Node Collection: Assemble nodes of multiple types:

Phase 2: Graph Neural Network Encoding and Representation Learning

- Objective: To transform the complex graph into a lower-dimensional embedding space where the proximity between drug and disease nodes predicts therapeutic potential.

- Materials & Steps:

- Model Architecture: Implement a signed directed GNN. This architecture is critical as it respects the direction and sign of edges during message passing between nodes, unlike standard GNNs.

- Feature Initialization: Initialize node features using available data (e.g., gene expression, drug chemical fingerprints).

- Model Training: Train the GNN in a self-supervised manner using a link prediction task. The model learns to predict missing edges in the graph, thereby learning a powerful, continuous representation (embedding) for each node.

Phase 3: Systematic Drug Combination Selection

- Objective: To identify a synergistic multi-drug combination from the top-ranking candidate drugs.

- Materials & Steps:

- Single Drug Scoring: Calculate a "DeepDrug score" for each drug based on its embedding's proximity to AD-related pathology nodes in the graph.

- Candidate Shortlisting: Apply a diminishing return-based threshold to the ranked list of single drugs to select a manageable set of top candidates.

- Combinatorial Optimization: Systematically evaluate high-order combinations (e.g., 3 to 5 drugs) from the shortlist. The lead combination is selected to maximize the synergistic coverage of multiple AD hallmarks (e.g., neuroinflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction). The DeepDrug study identified Tofacitinib, Niraparib, Baricitinib, Empagliflozin, and Doxercalciferol as the lead combination [35].

Diagram 1: DeepDrug Repurposing Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Resources for AI-Driven Drug Repurposing

| Research Reagent / Resource | Function & Application | Example/Tool |

|---|---|---|

| Structured Biological Knowledge Bases | Provides integrated, high-quality data on compounds, targets, and pathways for building reliable networks. | Open PHACTS Discovery Platform [36] |

| Graph Data Management System | Stores, queries, and manages the large, heterogeneous biomedical graph efficiently. | Neo4j, Amazon Neptune |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Framework | Provides the software environment to build, train, and validate the GNN models for representation learning. | PyTor Geometric, Deep Graph Library (DGL) |

| Cheminformatics Toolkit | Generates molecular descriptors, handles chemical data, and calculates similarities for ligand-based approaches. | RDKit, Open Babel |

| Virtual Screening & Docking Software | Performs structure-based screening by predicting how small molecules bind to a target protein. | AutoDock Vina, Glide (Schrödinger) |

| Network Visualization & Analysis Software | Enables the visualization, exploration, and topological analysis of the biological networks. | Cytoscape, yEd [34] |

Performance Data: AI Impact in Drug Discovery

The following tables summarize key quantitative evidence of AI's impact on improving the drug discovery process.

Table: Comparative Performance: AI vs. Traditional Methods

| Metric | Traditional HTS | AI/vHTS Approach | Context & Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hit Rate | 0.021% | ~35% | Tyrosine phosphatase-1B inhibitor screen [32] |

| Screening Library Size | 400,000 compounds | 365 compounds | Same target, achieving more hits with a smaller library [32] |

| Lead Discovery Time | >12-18 months | Potentially reduced by running in parallel with HTS assay development | CADD requires less preparation time [32] |

| Model Scope for Combination Therapy | Pairwise drug combinations | High-order combinations (3-5 drugs) | DeepDrug's systematic selection beyond two-drug pairs [35] |

Table: AI Model Implementation Parameters (2019-2024)

| AI Methodology | Primary Application in Drug Repurposing | Key Advantage | Reported Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Learning node embeddings from heterogeneous biomedical graphs [33] [35] | Captures complex, high-dimensional relationships between biological entities. | Dependent on data quality and graph structure; "garbage in, garbage out." [33] |