Optimizing Signaling Pathway Analysis with Genetic Algorithms: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of genetic algorithms (GAs) applied to signaling pathway analysis in biomedical research.

Optimizing Signaling Pathway Analysis with Genetic Algorithms: From Foundational Concepts to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of genetic algorithms (GAs) applied to signaling pathway analysis in biomedical research. It establishes the foundational principles of GAs and their relevance to complex biological systems, details methodological implementations for pathway optimization and drug discovery, addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for real-world applications, and presents rigorous validation frameworks for comparing algorithmic performance. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource bridges computational methods with therapeutic development, offering practical insights for leveraging GAs to unravel signaling pathway complexity and accelerate precision medicine initiatives.

Genetic Algorithms and Signaling Pathways: Building Blocks for Complex Biological Optimization

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) are heuristic optimization techniques inspired by natural selection and genetics, providing powerful solutions for complex problems resistant to traditional methods [1] [2]. In computational biology, GAs iteratively evolve populations of candidate solutions through selection, crossover, and mutation operations to approximate optimal solutions [3]. For signaling pathways research—which aims to decipher how cells communicate external signals to regulate internal gene expression—GAs offer a unique capability to simultaneously predict active signaling pathways and their structural topology by integrating protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks and gene expression data [4]. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying key pathways in developmental processes, disease mechanisms like cancer, and tissue regeneration strategies where traditional pathway analysis methods fall short.

The implementation of GAs requires careful consideration of their core components. As Rick Wicklin notes, implementing a genetic algorithm is as much an art as it is a science, requiring numerous heuristic choices about hyperparameters and operators that can significantly impact performance [1]. Within signaling pathways research, these choices become even more critical as researchers must balance biological plausibility with computational efficiency when reconstructing complex biological networks from high-throughput data.

Core Operational Principles

Selection Operations

Selection represents the survival-of-the-fittest mechanism in GAs, determining which candidate solutions proceed to reproduce based on their fitness. In signaling pathways research, the fitness function typically quantifies how well a candidate pathway configuration matches observed gene expression data within the constraints of known PPI networks [4]. Common selection techniques include:

- Tournament Selection: Randomly selects small subsets of individuals from the population and advances the fittest from each subset to the next generation.

- Roulette Wheel (Stochastic Universal) Selection: Assigns selection probability proportional to fitness scores, ensuring fitter individuals have higher chances of selection while maintaining diversity [3].

- Elitism: Preserves a predetermined number of best-performing individuals (eliteCount) unchanged into the next generation, guaranteeing that solution quality does not degrade across generations [3].

For signaling pathway identification, the selection pressure must be carefully balanced. Too strong selection may cause premature convergence to suboptimal pathways, while too weak selection slows useful discovery. The MATLAB documentation highlights that setting EliteCount too high causes the fittest individuals to dominate the population, potentially making the search less effective [3].

Crossover Operations

Crossover (recombination) combines genetic material from parent solutions to create offspring, mimicking biological sexual reproduction [5]. This operation enables the algorithm to exploit promising solution regions by merging beneficial traits from different parents. The following table summarizes common crossover techniques applicable to signaling pathway reconstruction:

Table 1: Crossover Operations in Genetic Algorithms

| Crossover Type | Mechanism | Applications in Signaling Pathways | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Point | Selects one random crossover point; swaps all data beyond this point between parents [5] | Useful for combining pathway segments with functional modules | Crossover point location |

| Two-Point | Selects two random points; swaps genetic material between these points [5] | Preserves blocks of interacting proteins in pathway structures | Start and end points of segment |

| Uniform | Each gene is selected randomly from corresponding genes of either parent [1] [5] | Effective for exploring diverse pathway topologies when combined with repair algorithms for illegal solutions | Individual gene selection probability (ProbCross) |

In practice, the optimal crossover strategy depends on the problem encoding. For signaling pathway identification with potential pathway cross-talk, uniform crossover often provides the necessary flexibility. As demonstrated in SAS/IML implementations, uniform crossover with a probability parameter (e.g., ProbCross = 0.3) exchanges approximately N×ProbCross genes between parent pathways [1]. This approach helps explore novel pathway configurations while maintaining biologically plausible structures through specialized repair operations that handle illegal solutions, such as missing pathway components or duplicated elements.

Mutation Operations

Mutation introduces random variations into individuals, maintaining population diversity and enabling exploration of new solution regions [1]. In signaling pathways research, mutation helps escape local optima by introducing novel protein connections or alternative pathway branches not present in the initial population. The mutation operation is typically controlled by a hyperparameter (pmut or mutation rate) that determines the probability of any single gene being altered [1].

For binary-encoded pathway representations, mutation consists of changing the parity of randomly selected elements. The number of mutation sites (k) can follow a binomial distribution, Binom(pmut, N), where N represents chromosome length [1]. Practical implementations often set a minimum k=1 to ensure mutation occurs even when probabilities are low. In pathway optimization, this might correspond to adding or removing a specific protein interaction from the candidate pathway.

More sophisticated mutation strategies adapt mutation rates based on population diversity metrics or employ targeted mutation operators that prioritize biologically plausible modifications. For example, in the HISP method for signaling pathway identification, mutation respects known biological constraints by only introducing experimentally supported protein interactions from PPI databases [4].

Application Notes: Genetic Algorithms for Signaling Pathway Identification

SPAGI Methodology and Workflow

The Signaling Pathway Analysis for putative Gene regulatory network Identification (SPAGI) method exemplifies the application of GAs to signaling pathway research [4]. SPAGI integrates PPI networks with gene expression data to identify active signaling pathways and their structures. The methodology follows these key stages:

Background Pathway Data Construction: Collects known receptors (R), kinases (K), and transcription factors (TF) from curated databases like Fantom5 and Uniprot, then extracts high-confidence PPIs from STRING database (confidence_score ≥ 700) [4].

Pathway Template Generation: Constructs all possible R-K-TF paths from the PPI data, representing potential signaling pathways.

Genetic Algorithm Optimization: Evolves populations of candidate pathways using fitness functions that measure concordance with gene expression data.

The following Graphviz diagram illustrates the complete SPAGI workflow:

SPAGI Workflow for Signaling Pathway Identification

HISP: Genetic Algorithm with Specialized Operators

The HISP method represents another GA approach specifically designed for signaling pathway reconstruction that incorporates gene knockout data to determine pathway directionality [4]. HISP employs specialized genetic operators tailored to pathway structures:

- Pathway-Aware Crossover: Combines segments of signaling pathways from two parents while maintaining connectivity between receptors, kinases, and transcription factors.

- Constraint-Respecting Mutation: Introduces variations that respect biological constraints, such as only including experimentally supported protein interactions.

- Directionality Incorporation: Utilizes gene knockout data to infer signaling direction during fitness evaluation.

HISP demonstrates how domain-specific knowledge can be incorporated into genetic operators to improve both the efficiency and biological relevance of the optimization process.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing GA for Signaling Pathway Optimization

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for applying GAs to identify active signaling pathways from gene expression and PPI data, based on the SPAGI and HISP approaches [4].

Preparation of Input Data

PPI Network Collection:

- Download PPI data from STRING database (version 10 or higher) for the relevant organism.

- Filter interactions using a confidence threshold (combined_score ≥ 700) to ensure high-quality interactions.

- Extract interactions involving known receptors, kinases, and transcription factors.

Gene Expression Data Processing:

- Obtain gene expression profiles for the biological condition of interest.

- Normalize expression data using appropriate methods (e.g., TPM for RNA-seq, RMA for microarrays).

- Transform expression values to z-scores if comparing across multiple conditions.

Background Pathway Template Generation:

- Enumerate all possible R-K-TF paths from the filtered PPI network.

- Exclude paths containing housekeeping genes if specific pathway activity is desired.

- Store resulting pathway templates with their associated PPI confidence scores.

Genetic Algorithm Configuration

Solution Encoding:

- Represent each candidate solution as a binary vector indicating inclusion/exclusion of specific pathway templates.

- Alternatively, use integer encoding to represent specific protein components and their connections.

Fitness Function Definition:

- Develop a fitness function that measures the agreement between candidate pathways and gene expression data.

- Incorporate PPI confidence scores as weighting factors in the fitness calculation.

- Include penalty terms for biologically implausible pathway structures.

Parameter Settings:

- Set population size based on problem complexity (typically 100-500 individuals).

- Configure selection pressure using tournament size (typically 2-5) or elitism count (1-5% of population).

- Set crossover probability to 0.6-0.8 and mutation probability to 0.01-0.05 per gene.

Execution and Validation

Algorithm Execution:

- Initialize population with random pathways or using domain knowledge.

- Run evolution for a fixed number of generations (typically 100-10,000) or until convergence.

- Maintain diversity using niching or fitness sharing techniques if premature convergence occurs.

Result Validation:

- Compare identified pathways against known signaling pathways from curated databases.

- Perform functional enrichment analysis on pathway components to assess biological relevance.

- Validate predictions using orthogonal data sources (e.g., phosphorylation data for kinase activity).

Protocol: Practical Identifiability Analysis for Experimental Design

Recent advances combine GAs with profile-likelihood methods for optimal experimental design in pharmacological modeling [6]. This protocol describes how to optimize sampling protocols for parameter identification in dose-response experiments:

Define Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) Model:

- Implement mathematical model describing drug concentration and effect (e.g., Eq. 1 in [6]).

- Identify parameters to be estimated (

k,UN,V,βdepending on model complexity).

Configure Genetic Algorithm:

- Encode sampling schedules as chromosomes representing sample timing.

- Use profile-likelihood-based metric as fitness function to minimize parameter uncertainty.

- Set population size to 50-100, crossover rate to 0.7-0.9, mutation rate to 0.01-0.1.

Execute Optimization:

- Run GA for 100-500 generations or until Q-criterion improvement plateaus.

- Validate optimal sampling schedules using Monte Carlo simulations.

- Compare with traditional D-optimality designs to confirm improved performance.

Quantitative Parameters and Performance Metrics

Table 2: Genetic Algorithm Parameters for Signaling Pathway Identification

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | Typical Values | Effect on Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population Parameters | Population Size | 100-500 individuals | Larger sizes increase diversity but computational cost |

| Number of Generations | 100-10,000 | More generations improve solution quality with diminishing returns | |

| Selection Parameters | Elite Count | 1-5% of population | Preserves best solutions; high values may cause premature convergence |

| Selection Method | Tournament (size 2-5) or Stochastic Universal | Tournament size controls selection pressure | |

| Crossover Parameters | Crossover Probability | 0.6-0.8 | Lower values slow recombination of good traits |

| Crossover Type | Uniform, Single-point, Two-point | Dependent on problem structure and encoding | |

| Mutation Parameters | Mutation Probability | 0.01-0.05 per gene | Higher values increase exploration but may disrupt good solutions |

| Mutation Type | Bit-flip, Gaussian, Custom | Domain-specific mutations can improve performance |

Table 3: Performance Metrics for GA in Signaling Pathway Applications

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Interpretation | Reported Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Efficiency | Generations to Convergence | Speed of algorithm progress | 100-10,000 depending on problem complexity |

| Fitness Evaluation Time | Computational cost per generation | Varies with fitness function complexity | |

| Solution Quality | Best Fitness Value | Quality of optimal solution found | Problem-dependent; should improve across generations |

| Average Fitness | Overall population quality | Should trend upward over generations | |

| Biological Relevance | Known Pathway Recovery | Percentage of biologically validated pathways identified | SPAGI: recovered known pathways in lens development [4] |

| Experimental Validation | Concordance with orthogonal experimental data | Case-dependent; crucial for method credibility |

Table 4: Key Research Resources for GA Applications in Signaling Pathways

| Resource Category | Specific Resource | Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPI Databases | STRING Database | Source of protein-protein interaction data | Use high-confidence interactions (score ≥ 700) [4] |

| BioGRID | Curated biological interactions | Provides experimentally validated interactions | |

| Gene Expression Data | GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus) | Source of transcriptomic data | Normalize appropriately for cell type/condition |

| TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) | Cancer-specific expression data | Useful for disease-focused pathway analysis | |

| Signaling Pathway Databases | Fantom5 | Curated receptor database | Source of known signaling molecules [4] |

| Uniprot | Protein information resource | Source of kinase annotations [4] | |

| Software Tools | SPAGI R Package | Implementation of signaling pathway GA | Available via GitHub [4] |

| SAS/IML | General GA implementation | Includes built-in mutation and crossover operations [1] | |

| MATLAB Global Optimization Toolbox | GA framework with customizable operators | Supports linear and nonlinear constraints [3] | |

| Computational Resources | High-Performance Computing Cluster | Parallel fitness evaluation | Essential for large-scale pathway analyses |

| Graphviz | Visualization of pathways and workflows | Create publication-quality diagrams |

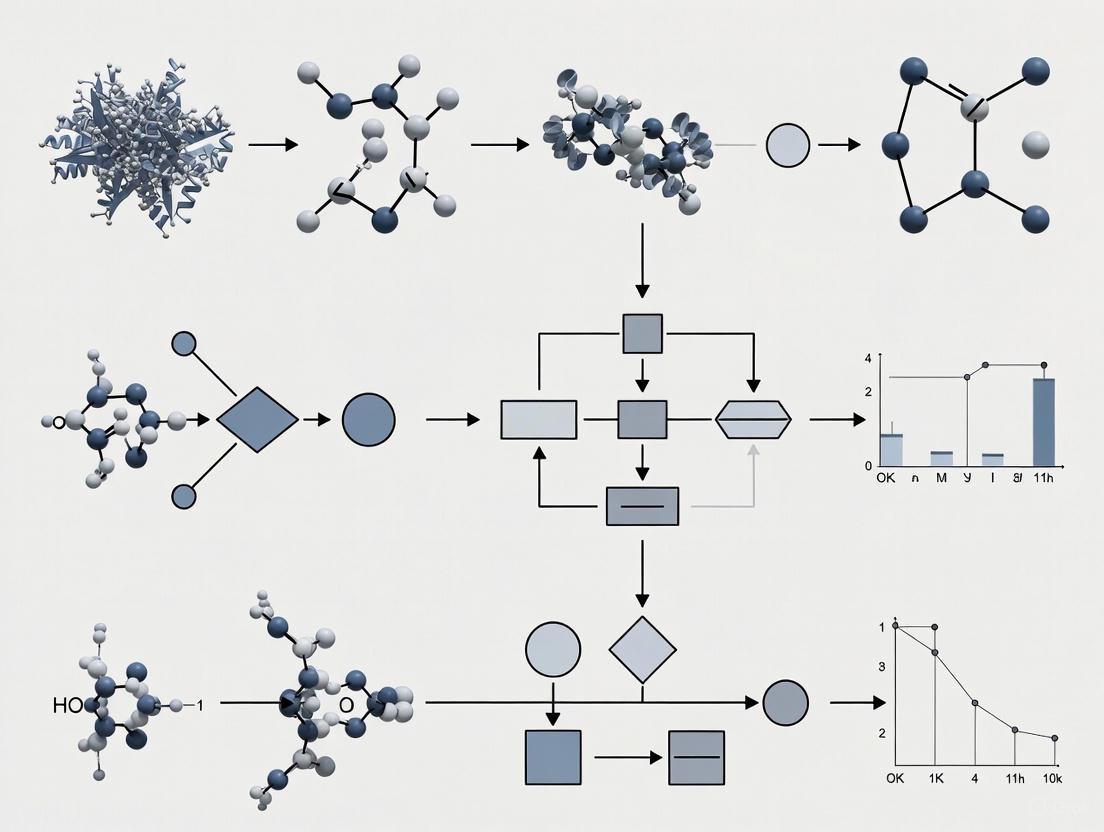

Workflow Visualization: Genetic Algorithm Structure

The following Graphviz diagram illustrates the complete standard genetic algorithm process and how it specializes for signaling pathway identification:

Standard GA Process with Signaling Pathway Specialization

Genetic algorithms provide a powerful framework for addressing the complex challenge of signaling pathway identification from high-throughput biological data. Through the careful implementation of selection, crossover, and mutation operations—tailored to the specific constraints of biological networks—researchers can reconstruct active signaling pathways and their structures with increasing accuracy. The integration of PPI data with gene expression profiles creates a rich foundation for these optimization techniques, while specialized approaches like SPAGI and HISP demonstrate how domain knowledge can be incorporated to enhance biological relevance.

As computational biology continues to grapple with increasingly complex datasets, the flexibility and robustness of genetic algorithms position them as valuable tools for deciphering cellular communication networks. The experimental protocols and parameters outlined in this article provide researchers with practical guidance for implementing these methods in their own signaling pathways research, potentially accelerating discoveries in disease mechanisms and therapeutic development.

Cancer remains a major global health challenge, with its pathogenesis intricately linked to the dysregulation of intracellular signaling networks that control core cellular processes. These pathways, which normally regulate cell growth, differentiation, survival, and death, become subverted in cancer, leading to uncontrolled proliferation and metastatic dissemination [7]. The therapeutic targeting of these aberrant signaling cascades represents a cornerstone of modern precision oncology, offering more specific treatment options compared to traditional chemotherapy [8].

Understanding these signaling pathways is not only crucial for developing targeted therapies but also provides an ideal foundation for applying computational approaches such as genetic algorithms (GAs). GAs can help optimize drug combinations, identify novel drug targets, and decipher complex pathway interactions, thereby accelerating oncology drug discovery [9] [10]. This article explores major cancer signaling pathways, their therapeutic targeting, and the integration of genetic algorithms in signaling pathway research.

Major Cancer-Associated Signaling Pathways

Wnt Signaling Pathway

The evolutionarily conserved Wnt signaling pathway plays fundamental roles in embryonic development, tissue homeostasis, and stem cell maintenance. Its dysregulation is strongly implicated in tumorigenesis, cancer progression, and therapeutic resistance [11] [12]. The pathway branches into canonical (β-catenin-dependent) and non-canonical (β-catenin-independent) signaling.

Canonical Pathway: In the absence of Wnt ligands ("OFF" state), a destruction complex comprising Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC), Axin, Casein Kinase 1 (CK1), and Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3β (GSK3β) facilitates the phosphorylation and proteasomal degradation of β-catenin. Pathway activation ("ON" state) occurs when Wnt ligands bind to Frizzled (FZD) receptors and Low-density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Proteins 5/6 (LRP5/6) co-receptors. This interaction activates Dishevelled (DVL), which inhibits the destruction complex, allowing β-catenin to accumulate and translocate to the nucleus. Nuclear β-catenin then partners with T-cell Factor/Lymphoid Enhancer Factor (TCF/LEF) transcription factors to activate target genes such as c-MYC and Cyclin D1, which promote cell cycle progression and survival [11] [12].

Non-Canonical Pathways: The non-canonical branches, including the planar cell polarity (PCP) and Wnt/Ca²⁺ pathways, regulate cell polarity, migration, and adhesion. The Wnt/Ca²⁺ pathway, activated by ligands like WNT5A, triggers calcium release from the endoplasmic reticulum, activating Calmodulin Kinase II (CAMKII) and Protein Kinase C (PKC), which can inhibit canonical signaling [7] [12].

Dysregulation of Wnt signaling frequently occurs through mutations in key components such as APC and CTNNB1 (encoding β-catenin), or through aberrant expression of Wnt ligands, FZD receptors, or endogenous inhibitors like Dickkopf (DKK) and secreted Frizzled-Related Proteins (sFRPs) [12]. This pathway exhibits extensive crosstalk with other signaling cascades, including PI3K/AKT and MAPK, and influences the tumor microenvironment and immune cell function, contributing to immunotherapy resistance in cancers like non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [7].

PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is a critical regulator of cell growth, proliferation, metabolism, and survival, and is one of the most frequently dysregulated pathways in human cancers [7]. Activation typically begins when growth factors bind to receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), recruiting Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase (PI3K) to the cell membrane. PI3K phosphorylates the lipid phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP₂) to generate phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP₃). This leads to the recruitment and activation of AKT (Protein Kinase B). The tumor suppressor PTEN acts as a key negative regulator by dephosphorylating PIP₃ back to PIP₂. Activated AKT phosphorylates numerous downstream effectors, including mTOR (mammalian Target of Rapamycin), which coordinates protein synthesis, cell growth, and metabolism. Hyperactivation of this pathway, through mutations in PIK3CA (encoding the catalytic subunit of PI3K), AKT, or loss of PTEN, drives uncontrolled cell proliferation and survival [7].

Other Key Pathways

Several additional signaling pathways contribute significantly to cancer pathogenesis:

- MAPK/ERK Pathway: This pathway, often activated by growth factors and Ras mutations, transmits signals from cell surface receptors to the nucleus via a kinase cascade (Ras → Raf → MEK → ERK), regulating gene expression involved in cell proliferation and survival [7].

- Notch Signaling: A highly conserved pathway where cell-to-cell contact triggers proteolytic cleavage of Notch receptors, releasing the Notch Intracellular Domain (NICD) which translocates to the nucleus to activate transcription factors. Its role is context-dependent, acting as an oncogene in some cancers (e.g., T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia) and a tumor suppressor in others [7].

- Hedgehog (Hh) Signaling: Crucial for embryonic patterning, its dysregulation in cancers like basal cell carcinoma and medulloblastoma occurs through mutations in Patched (PTCH) or Smoothened (SMO), leading to constitutive activation of GLI transcription factors [7].

- PD-1/PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint Pathway: While not a driver pathway in cancer cells, this immune regulatory axis is often hijacked by tumors. The interaction between Programmed Death-1 (PD-1) on T cells and its ligand (PD-L1) on tumor cells inactivates T cells, allowing the tumor to evade immune destruction. Inhibiting this interaction with checkpoint blockers has revolutionized cancer immunotherapy [7].

Table 1: Core Components of Major Cancer Signaling Pathways

| Pathway | Key Receptors/Components | Main Downstream Effectors | Common Genetic Alterations in Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wnt/β-catenin | FZD, LRP5/6, DVL | β-catenin, TCF/LEF, GSK3β | APC, CTNNB1 (β-catenin), AXIN mutations [11] [12] |

| PI3K/AKT/mTOR | PI3K, AKT, PTEN, mTOR | PDK1, TSC1/2, S6K | PIK3CA, AKT amplifications; PTEN loss [7] |

| MAPK/ERK | Ras, Raf, MEK, ERK | c-Fos, c-Jun, ELK1 | KRAS, NRAS, BRAF mutations [7] |

| Notch | Notch Receptors, DLL/Jagged | NICD, CSL/RBP-Jκ | Notch translocations/fusions; FBXW7 mutations [7] |

| Hedgehog | PTCH, SMO | GLI1/2/3 | PTCH1 loss; SMO mutations [7] |

Therapeutic Targeting of Signaling Pathways

Targeting dysregulated signaling pathways has become a mainstay of precision oncology. Therapeutic strategies include small molecule inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies, and, more recently, drug repurposing.

Established Targeted Therapies

The development of agents that selectively inhibit key nodes in oncogenic signaling cascades has improved patient outcomes across many cancer types. These include:

- WNT Pathway Inhibitors: Several agent classes are in development, including Porcupine (PORCN) inhibitors (block Wnt ligand secretion), Tankyrase (TNKS) inhibitors (target Axin stability), FZD-targeted monoclonal antibodies, and inhibitors of the β-catenin/TCF transcriptional complex [11].

- PI3K/AKT/mTOR Inhibitors: Alpelisib, a PI3Kα inhibitor, is approved for PIK3CA-mutated breast cancer. Everolimus (mTOR inhibitor) is used in renal cell carcinoma and other malignancies [9] [7].

- MAPK Pathway Inhibitors: BRAF inhibitors (vemurafenib, dabrafenib) and MEK inhibitors (trametinib, cobimetinib) are standard for BRAF-mutant melanoma [7].

- Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Antibodies targeting PD-1 (pembrolizumab, nivolumab), PD-L1 (atezolizumab, durvalumab), and CTLA-4 (ipilimumab) reactivate the immune system against cancer cells [7] [13].

Drug Repurposing in Oncology

Drug repurposing—finding new uses for existing, approved drugs—is a promising strategy to accelerate the availability of cancer therapies while reducing development costs and risks [14]. Examples highlighted in recent research include:

- Sulconazole: An antifungal agent found to inhibit PD-1 expression in cancer and immune cells by blocking NF-κB and calcium signaling, suggesting potential for immunomodulatory therapy [14].

- Olaparib: A PARP inhibitor used in BRCA-mutant breast and ovarian cancers, which has shown efficacy as monotherapy in improving progression-free survival in lung cancer [14].

- BCG (Bacillus Calmette-Guérin): A live attenuated vaccine for tuberculosis, now a standard treatment for carcinoma in situ of the bladder, representing a successful application of immunotherapy in cancer prevention and treatment [13].

Table 2: Selected Targeted Therapies and Repurposed Drugs in Cancer

| Therapeutic Agent | Original Indication (if repurposed) | Molecular Target | Primary Cancer Indication(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpelisib | - | PI3Kα | PIK3CA-mutant Breast Cancer [9] |

| Vantictumab | - | FZD Receptors | Investigational for WNT-driven cancers [12] |

| Pembrolizumab | - | PD-1 | Various (e.g., Melanoma, NSCLC) [13] |

| Sulconazole | Antifungal | NF-κB / Calcium Signaling | Investigational for immunologically evasive tumors [14] |

| Olaparib | BRCA-mutant cancers | PARP | Lung Cancer (under investigation) [14] |

| BCG Vaccine | Tuberculosis | Immune System | Bladder Carcinoma in situ [13] |

Application of Genetic Algorithms in Signaling Pathway Research

Genetic Algorithms (GAs), inspired by natural selection, provide powerful computational methods for solving complex optimization problems in cancer research. They are particularly suited for analyzing the high-dimensional, interconnected data generated from signaling pathway studies.

GA Fundamentals and Workflow

A GA operates by maintaining a population of candidate solutions (chromosomes) that evolve over generations. The process involves key steps: Initialization (creating a random population), Selection (choosing fit individuals for reproduction based on a fitness function), Crossover (recombining genetic material between parents), and Mutation (introducing random changes to maintain diversity). This cycle repeats until a termination criterion is met, yielding an optimized solution [15] [10]. This workflow is highly adaptable to various bioinformatics challenges.

Key Applications in Cancer Signaling

GAs are being applied to critical problems in oncology drug discovery and signaling network analysis:

- Identifying Optimal Drug Target Combinations: Cancer cells often develop resistance by using parallel signaling pathways. Yavuz et al. used protein-protein interaction networks and shortest-path algorithms to discover key communication nodes as optimal co-targets. This approach successfully identified effective combinations like Alpelisib + LJM716 in breast cancer and Alpelisib + Cetuximab + Encorafenib in colorectal cancer, which were validated in patient-derived models [9].

- Discovering Disease Modules: DM-MOGA is a multi-objective GA designed to identify disease modules—subnetworks of closely interacting genes relevant to a specific disease—from gene co-expression networks in NSCLC. It optimizes fitness functions based on network topology and functional similarity, leading to the identification of core modules with confirmed relevance to lung cancer pathogenesis [10].

- Automated Prompt Optimization for Literature Mining: GAAPO (Genetic Algorithmic Applied to Prompt Optimization) uses a hybrid GA framework to evolve prompts for Large Language Models (LLMs). This method can efficiently mine vast scientific literature to extract information on signaling pathways and potential therapeutic associations, demonstrating the utility of GAs in knowledge discovery [15].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Network-Based Identification of Drug Target Combinations

This protocol outlines the computational method for discovering synergistic drug target combinations, as described by Yavuz et al. [9].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| TCGA & AACR GENIE Databases | Sources for somatic mutation profiles from cancer patients [9]. |

| HIPPIE PPI Database | A repository of high-confidence Protein-Protein Interactions to construct the cellular network [9]. |

| PathLinker Algorithm | A graph-theoretic algorithm for reconstructing signaling pathways and calculating k-shortest paths in a network [9]. |

| Enrichr Tool | A web-based tool for pathway enrichment analysis to validate the biological relevance of identified nodes/paths [9]. |

II. Methodology

Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Obtain somatic mutation data from large-scale cancer genomics resources like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and AACR Project GENIE.

- Apply preprocessing: remove low-confidence variants, prioritize primary tumor samples, and filter potential germline events.

- Identify statistically significant pairs of co-existing mutations (doublets) across different proteins using Fisher's Exact Test with multiple testing correction [9].

Network Construction and Analysis:

- Construct a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network using a high-confidence database like HIPPIE.

- For each significant mutation pair (Protein A, Protein B), use the PathLinker algorithm with parameter k=200 to compute the 200 shortest simple paths connecting them within the PPI network. This identifies potential bypass routes cancer cells might use for resistance [9].

Target Identification and Validation:

- The resulting subnetwork comprises the source nodes (Protein A), target nodes (Protein B), and the proteins lying on the shortest paths between them (bridge nodes).

- Proteins that frequently appear as key connectors (bridge nodes) in these subnetworks are prioritized as potential co-targets.

- Validate the therapeutic relevance of the proposed co-targets in preclinical models, such as patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) [9].

Protocol: Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm for Disease Module Identification (DM-MOGA)

This protocol details the use of DM-MOGA for identifying disease-relevant modules from gene expression data in NSCLC [10].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| NCBI GEO Database | Source for NSCLC gene expression microarray datasets [10]. |

| HPRD (Human Protein Reference Database) | Provides the curated Protein-Protein Interaction Network (PPIN) used as a scaffold [10]. |

| Limma R/Bioconductor Package | Statistical analysis tool for identifying Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) from microarray data [10]. |

| GOSemSim R Package | Calculates semantic similarity between Gene Ontology (GO) terms, used to compute a fitness function [10]. |

II. Methodology

Network Construction:

- Differential Expression Analysis: Process raw gene expression data from GEO using the

limmapackage in R to identify DEGs (adjusted p-value < 0.05). - Interaction Estimation: Calculate the interaction intensity (correlation) between DEGs using Gaussian Copula Mutual Information (GCMI).

- Network Integration: Filter the correlation matrix using the HPRD PPIN. Set any correlation to zero if the corresponding protein interaction does not exist in HPRD, resulting in a final gene co-expression network (GCN) [10].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Process raw gene expression data from GEO using the

Pre-Simplification with Boundary Correction:

- To handle large networks, perform a pre-simplification step. This involves randomly selecting a seed node and building a local module (LM) by iteratively adding its high-degree neighbors and their strongly connected joint neighbors.

- Apply a boundary correction strategy to reassign genes on the margin of LMs to the most appropriate module, improving module coherence [10].

DM-MOGA Execution:

- Chromosome Encoding: Represent a solution (a set of modules) as a chromosome where each gene indicates the module assignment of a network node.

- Fitness Evaluation: Optimize two fitness functions simultaneously:

- Davies-Bouldin Index (DBI): Measures module separation and compactness based on topology.

- Clustering Coefficient: Evaluates the connection strength and functional similarity within a module using the

sim_{Rel}score from GOSemSim.

- Evolutionary Operations: Evolve the population over generations using selection, crossover, and mutation operators. The algorithm decomposes the multi-objective problem into several single-objective subproblems for efficiency.

- Solution Selection: After evolution, select the solution with the highest composite score from the Pareto front. The largest module within this solution is typically taken as the core disease module for further biological validation [10].

The intricate network of dysregulated signaling pathways forms the backbone of cancer pathogenesis. A deep understanding of pathways like Wnt, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and MAPK is indispensable for developing targeted therapies that form the core of precision oncology. As this field advances, the integration of sophisticated computational approaches, particularly Genetic Algorithms, is proving to be a powerful strategy. GAs are accelerating discovery by optimizing drug combinations, identifying critical disease modules within molecular interaction networks, and mining complex biological data. The continued synergy between experimental biology and computational optimization holds great promise for unraveling the complexity of cancer signaling and delivering more effective, personalized cancer therapies.

Why GAs Are Ideal for High-Dimensional Biological Search Spaces

In the field of computational biology, researchers are consistently faced with the challenge of navigating high-dimensional search spaces, such as those found in genomics, proteomics, and signaling pathway analysis. These spaces, characterized by thousands of interacting variables, present significant obstacles for conventional optimization techniques due to the curse of dimensionality and the presence of numerous local optima. Genetic Algorithms (GAs) and other evolutionary optimization strategies have emerged as powerful tools for these environments because of their ability to balance broad exploration of the search space with targeted exploitation of promising regions. This application note details how GAs, particularly enhanced variants, are being successfully applied to high-dimensional biological problems, using gibberellin (GA) signaling pathway research as a primary case study. We provide specific protocols and reagent solutions to facilitate the adoption of these methods in signaling pathway research.

Key Advantages of Genetic Algorithms in Biological Contexts

Evolutionary algorithms, including GAs, possess several inherent characteristics that make them particularly suitable for high-dimensional biological optimization problems:

- Population-Based Search: Unlike point-based methods, GAs maintain a diverse population of candidate solutions, enabling parallel exploration of multiple regions in the fitness landscape and reducing the probability of becoming trapped in suboptimal local solutions [16].

- Minimal Assumption Requirement: GAs do not require gradient information or assumptions about the smoothness of the search space, making them ideal for the discontinuous, noisy, and multimodal landscapes common in biological data [17].

- Effective Dimensionality Reduction: Through feature selection and representation learning, GAs can identify compact, biologically relevant subsets from thousands of potential variables. For instance, in gene selection tasks, enhanced GAs have successfully identified ultra-compact biomarker subsets (≤5% of original features) while maintaining high classification performance (F1-score: 0.953±0.012) [16].

- Hybridization Potential: GAs can be effectively combined with local search techniques and gradient-based methods to refine solutions, as demonstrated in neural architecture search applications for medical image segmentation [17].

Case Study: Optimizing Analysis of Gibberellin Signaling Pathways

The gibberellin (GA) signaling pathway represents an ideal proving ground for GA-based optimization in high-dimensional biological spaces. Research into this complex plant hormone pathway involves analyzing multidimensional data from genetic, protein interaction, and phenotypic analyses.

The following diagram illustrates the core components and interactions of the GA signaling pathway, highlighting potential optimization targets:

Diagram 1: Gibberellin Signaling Pathway and Regulatory Mechanisms

Experimental Quantification of GA Pathway Components

Table 1: Phenotypic Effects of GA Signaling Mutants in Arabidopsis

| Genotype/Treatment | Mucilage Accumulation | Stem Elongation | Flowering Time | Key Molecular Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Type (Control) | Baseline (100%) | Baseline | Baseline | Normal DELLA degradation |

| GA3 Treatment | Increased (~150%) | Enhanced | Accelerated | Downregulated DELLA, upregulated biosynthetic genes |

| paclobutrazol Treatment | Decreased (~50%) | Reduced | Delayed | DELLA stabilization |

| ga1-3 (GA-deficient) | Severely reduced | Dwarfed | Delayed | DELLA accumulation |

| dellaQ (DELLA-deficient) | Significantly increased | Enhanced | Accelerated | constitutive GA response |

| pux1 mutant | Increased | Enhanced | Accelerated | Increased GID1 expression, decreased RGA [18] |

Data derived from experimental analyses of Arabidopsis mutants and pharmacological treatments [19] [18].

Protocol: Applying Genetic Algorithms to GA Signaling Pathway Optimization

Workflow for GA-Driven Pathway Analysis

The following diagram outlines the integrated computational and experimental workflow:

Diagram 2: Integrated Workflow for GA-Optimized Signaling Pathway Analysis

Step-by-Step Protocol

Phase 1: Experimental Data Generation

Biological Material Preparation

- Select appropriate plant materials (e.g., Arabidopsis wild-type and mutant lines such as ga1-3, dellaQ, pux1)

- Apply hormone treatments: 10-100 μM GA3 for GA application; 1-10 μM paclobutrazol for GA biosynthesis inhibition

- Implement cold stratification (4°C for 2-4 days) and after-ripening (dry storage for 2-4 weeks) for dormancy-breaking treatments [18]

High-Dimensional Data Collection

- Transcriptomic profiling: Quantify expression of pathway genes (GID1a/b/c, DELLAs, PUX1, MUM4, GATL5, RRT1) via RT-qPCR or RNA-seq

- Protein interaction analysis: Conduct yeast two-hybrid screens and co-immunoprecipitation for GID1-DELLA-PUX1-CDC48 interactions

- Phenotypic quantification: Measure seed mucilage accumulation, root elongation, flowering time, and stem growth parameters

Phase 2: Genetic Algorithm Implementation

Problem Formulation

- Define search space parameters based on experimental data (e.g., gene expression levels, protein concentrations, kinetic parameters)

- Establish fitness function to maximize agreement between pathway model predictions and experimental observations

- Set constraints based on biological plausibility (e.g., non-negative reaction rates)

Algorithm Configuration

- Initialize population with diverse candidate solutions

- Implement enhanced GA strategies:

- Chaotic Lévy flight modulation for dynamic step-size adjustment to prevent premature convergence [16]

- Phase-aware memory banks to preserve elite solutions across generations

- Entropy-informed adaptive restart to maintain population diversity when stagnation is detected

- Set termination criteria (convergence threshold or maximum generations)

Validation and Iteration

- Validate optimized pathway models with independent experimental data

- Perform sensitivity analysis to identify most influential parameters

- Refine search space based on validation results and repeat optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for GA Signaling Pathway Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Inhibitors/Agonists | GA3, paclobutrazol | Modulate GA signaling pathways; establish dose-response relationships | [19] [18] |

| Arabidopsis Mutants | ga1-3, dellaQ, pux1 | Dissect specific component functions in GA signaling cascade | [19] [18] |

| Molecular Biology Tools | Yeast two-hybrid system, Co-IP reagents | Validate protein-protein interactions (GID1-DELLA-PUX1-CDC48) | [19] [18] |

| Gene Expression Assays | RT-qPCR primers for GL2, MUM4, GATL5 | Quantify transcript levels of pectin biosynthesis genes | [19] |

| Computational Resources | CLA-MRFO algorithm, Mixed-GGNAS framework | High-dimensional optimization and feature selection | [16] [17] |

| Visualization Tools | Parallel coordinates, t-SNE, PCA | Explore high-dimensional data relationships and clusters | [20] |

Performance Metrics and Benchmarking

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Optimization Algorithms on High-Dimensional Problems

| Algorithm | Application Context | Key Performance Metrics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLA-MRFO (Enhanced GA) | Gene feature selection | 31.7% performance gain; identified ultra-compact features (≤5%) with F1-score: 0.953±0.012 [16] | Excellent exploration-exploitation balance; consistent behavior (<5% variance) | Requires parameter tuning |

| Mixed-GGNAS (GA + Gradient Descent) | Medical image segmentation | Outperformed state-of-the-art NAS methods and manually designed networks [17] | Combines global search (GA) with local refinement (gradient descent) | Computational intensity |

| Standard GAs | General optimization | Variable performance on CEC'17 benchmark functions [16] | Flexibility; minimal assumptions | Prone to premature convergence |

| Gradient-Based Methods | Differentiable search spaces | Efficient local search in continuous spaces | Fast convergence in smooth landscapes | Poor performance on multimodal problems |

Genetic Algorithms represent a powerful and flexible approach for navigating the high-dimensional search spaces inherent in biological research, particularly in complex signaling pathways such as the gibberellin system. Their population-based nature, ability to handle non-linear relationships, and capacity for identifying meaningful patterns in vast parameter spaces make them ideally suited for modern computational biology challenges. The integration of enhanced strategies such as chaotic Lévy flight modulation and adaptive restart mechanisms further improves their performance in these demanding environments. As biological datasets continue to grow in size and complexity, GAs and other evolutionary approaches will play an increasingly vital role in extracting meaningful biological insights and accelerating discovery in signaling pathway research and drug development.

Key Challenges in Pathway Analysis That GAs Can Address

Pathway analysis is a cornerstone of modern bioinformatics, providing essential tools for extracting meaningful biological insights from high-throughput experimental data such as genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics. The primary goal of these methods is to identify relevant groups of related genes or proteins that are altered in case samples compared to controls, thereby reducing complexity and increasing explanatory power over analyses of individual molecules [21] [22]. Despite their widespread adoption and utility, conventional pathway analysis methods face significant challenges, particularly when dealing with the inherent complexity of biological systems and the limitations of typical experimental datasets.

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) represent a class of computational optimization techniques inspired by the principles of natural selection and genetics. They solve complex problems by iteratively improving a population of potential solutions through selection, crossover, and mutation operations [2]. In the context of pathway analysis, GAs offer promising approaches to overcome methodological limitations, particularly for feature selection, parameter optimization, and identifying optimal pathway modules in large-scale biological networks. This application note outlines key challenges in pathway analysis where GAs provide distinct advantages and presents detailed protocols for their implementation.

Key Challenges in Conventional Pathway Analysis

Multi-Pathway Complexity and Signal Dilution

Experimental gene sets often represent multiple biological pathways simultaneously, which significantly complicates analysis. When a gene set contains genes from different functional modules, association signals to any single pathway become weakened by the presence of genes associated with other pathways [23]. This signal dilution effect reduces the sensitivity of pathway analysis methods, as genes belonging to each specific module may constitute only a small fraction of all genes in the gene set. Additionally, studied gene sets frequently contain noise in the form of genes not related to the main phenotypes, further contributing to false negatives and reduced analytical sensitivity [23].

Dimensionality and Feature Selection Problems

Microarray and other high-throughput technologies face the "large-p-small-n" paradigm, where datasets contain a massive number of features (genes) with only a limited number of samples typically available [24]. This dimensionality problem creates significant challenges for robust statistical analysis, often leading to model overfitting and reduced generalizability. Including too many features can reduce model accuracy, while excluding relevant features may omit crucial biological information [24]. Traditional feature selection methods like Stepwise Forward Selection (SFS) use heuristic approaches that may miss optimal gene combinations, particularly when complex interactions exist between molecular features.

Limitations in Current Methodological Approaches

Pathway analysis methods have evolved through several generations, each with distinct limitations. First-generation Over-Representation Analysis (ORA) approaches treat pathways as simple gene lists, ignoring the underlying network topology and interactions between gene products [22]. They typically rely on arbitrary significance thresholds, discarding moderately significant genes and resulting in substantial information loss. Second-generation Functional Class Scoring (FCS) methods use the entire dataset but still generally assume gene independence, neglecting biological correlations [22]. Modern network-based methods improve sensitivity but can suffer from high false positive rates when testing random gene sets [23]. The table below summarizes these key methodological challenges:

Table 1: Key Challenges in Pathway Analysis Methods

| Challenge Category | Specific Limitations | Impact on Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Pathway Complexity | Signal dilution from mixed pathways [23] | Reduced sensitivity, increased false negatives |

| Dimensionality Problems | Large number of features with small samples [24] | Overfitting, reduced generalizability |

| ORA Methods | Arbitrary thresholds, gene independence assumption [22] | Information loss, biased significance estimates |

| Network-Based Methods | High false positive rates with random gene sets [23] | Reduced specificity, misleading results |

| Topology Ignorance | Treatment of pathways as unstructured gene sets [25] | Loss of positional and regulatory information |

How Genetic Algorithms Address Pathway Analysis Challenges

Enhanced Feature Selection for High-Dimensional Data

Genetic algorithms provide a powerful approach for feature selection in high-dimensional biological data. Unlike traditional methods like Stepwise Forward Selection (SFS), GAs can efficiently explore a much larger solution space of possible gene combinations [24]. In comparative studies, GA-based feature selection frameworks have demonstrated superior performance over SFS approaches, leading to better cancer outcome prediction and the identification of more biologically relevant gene sets [24]. The evolutionary approach of GAs allows them to evaluate feature subsets more comprehensively, considering complex interactions between genes that simpler methods might miss.

Optimization of Pathway Clustering and Module Detection

Pre-clustering of gene sets into more homogeneous modules before pathway analysis can significantly improve sensitivity by separating mixed pathway signals [23]. Genetic algorithms excel at identifying optimal clustering solutions in biological networks. By representing potential cluster configurations as individuals in a population, GAs can evolve toward partitionings that maximize intra-module connectivity while minimizing inter-module connections. This approach is particularly valuable for pathway analysis methods that struggle with complex gene sets representing multiple biological mechanisms, as clustering can increase sensitivity and provide deeper insights into the biological phenomena under investigation [23].

Overcoming Methodological Limitations

GAs address several specific limitations of conventional pathway analysis methods. For ORA approaches, GAs can eliminate the need for arbitrary thresholds through fitness functions that incorporate continuous statistical measures. For network-based methods, GAs can optimize parameter settings to reduce false positive rates [23]. Additionally, GAs can incorporate pathway topology information into the analysis framework, enabling more biologically realistic models that account for interactions and dependencies between pathway components [25]. The versatility of GAs allows them to be integrated with various pathway analysis methodologies, enhancing their performance and robustness.

Table 2: GA Solutions to Pathway Analysis Challenges

| Pathway Analysis Challenge | GA Solution Approach | Advantage Gained |

|---|---|---|

| High-dimensional feature selection | Evolutionary search for optimal gene subsets [24] | Identifies more predictive and biologically relevant gene sets |

| Multi-pathway complexity | Pre-clustering into homogeneous modules [23] | Increased sensitivity and deeper biological insights |

| Arbitrary threshold dependency | Fitness functions using continuous measures | Reduced information loss, more robust results |

| Topology ignorance | Incorporation of network structure in fitness evaluation [25] | More biologically realistic pathway models |

| Parameter optimization | Evolutionary tuning of method parameters [23] | Reduced false positive rates, improved specificity |

Quantitative Performance Comparisons

Evaluations of pathway activity inference methods reveal important performance patterns relevant to GA implementations. Studies comparing topology-based and non-topology-based methods show that methods incorporating pathway structure generally demonstrate greater robustness and reproducibility [25]. In assessments across multiple cancer datasets, topology-based methods consistently outperformed non-topology approaches in reproducibility power, with the entropy-based Directed Random Walk (e-DRW) method exhibiting the highest reproducibility across most datasets [25].

The reproducibility power of pathway activity inference methods generally decreases as the number of pathway selections increases, a trend observed across methodological approaches [25]. This relationship highlights the importance of optimized feature and pathway selection, where GAs can provide significant value. The performance advantage of methods that incorporate biological knowledge into their analytical framework suggests similar benefits could be realized through GA approaches that evolve solutions based on fitness functions incorporating topological information.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: GA-Based Feature Selection for Pathway Analysis

This protocol details the application of genetic algorithms for selecting optimal gene subsets in pathway analysis of microarray data.

Materials:

- Gene expression dataset (e.g., microarray data)

- Pathway database (KEGG, Reactome, or NCI-PID)

- Computational environment with GA capabilities (R, Python)

Procedure:

Data Pre-processing:

- Perform quality control on gene expression data

- Normalize data using appropriate methods (e.g., quantile normalization)

- Conduct pre-selection to reduce feature space using statistical tests (e.g., Welch t-test) [24]

- Retain top 5% of statistically significant genes for further analysis

GA Configuration:

- Encoding: Represent solutions as binary strings where each bit corresponds to a gene's inclusion (1) or exclusion (0) [24]

- Initialization: Generate initial population of 100 individuals randomly

- Fitness Function: Design a function that considers:

- Classification performance (e.g., misclassification error)

- Number of selected features (penalize excessive features)

- Biological relevance (e.g., mutual information between features) [24]

- Selection: Apply roulette wheel selection with elite count of 10

- Crossover: Use scattered crossover with rate of 0.8

- Mutation: Implement bit-flip mutation with rate of 0.2, limiting mutations to 1 to number of active features

Execution and Validation:

- Run GA for fixed generations or until convergence

- Evaluate final gene set using cross-validation

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis on selected genes

- Compare results with traditional methods (e.g., SFS) for performance validation

Protocol 2: Pathway-Aware Clustering with Genetic Algorithms

This protocol describes how to implement GA-based clustering of gene sets into functionally coherent modules before pathway enrichment analysis.

Materials:

- Query gene set from experimental data

- Functional association network (FunCoup or STRING)

- Pathway annotation database (KEGG)

Procedure:

Network Projection:

- Map query gene set onto functional association network

- Extract network neighborhood including direct interactions

GA Clustering Setup:

- Encoding: Represent cluster assignments as integer strings

- Initialization: Create random partitionings of genes into k clusters

- Fitness Function: Optimize for:

- High intra-cluster connectivity density

- Low inter-cluster connections

- Functional coherence based on pathway annotations

- Genetic Operators:

- Specialized crossover that preserves cluster structure

- Mutation operators that reassign genes between clusters

Cluster Optimization:

- Evolve population for specified generations

- Select optimal clustering solution based on fitness

- Validate clusters for functional homogeneity

Pathway Enrichment:

- Perform pathway analysis on each cluster separately using network-based methods (ANUBIX, BinoX, or NEAT) [23]

- Compare results with non-clustered approach

- Evaluate specificity using negative controls

Visualization of GA Applications in Pathway Analysis

Genetic Algorithm Workflow for Pathway Analysis

GA Pathway Analysis Workflow

Signaling Pathway with Sensitivity Amplification

Signaling Cascade with Amplification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for GA-Enhanced Pathway Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| FunCoup Network | Functional association network | Provides evidence-weighted gene interactions for network-based analysis [23] |

| STRING Database | Protein-protein interaction database | Source of confidence scores for association metrics in multivariate tests [26] |

| KEGG Pathway Database | Pathway knowledge base | Reference pathways for enrichment testing and functional interpretation [23] [22] |

| HitPredict Database | Protein interaction database | Alternative source of probabilistic confidence scores for covariance estimation [26] |

| ANUBIX Tool | Network-based pathway analysis | Statistical testing of pathway enrichment using beta-binomial distribution [23] |

| Microarray Data | Gene expression measurements | Primary input data for pathway analysis typically with limited samples [24] |

| Mass Spectrometry Data | Proteomic measurements | Quantitative protein data with limited replicates requiring specialized methods [26] |

Genetic algorithms offer powerful solutions to persistent challenges in pathway analysis, particularly in addressing multi-pathway complexity, high-dimensional feature selection, and methodological limitations of conventional approaches. By leveraging evolutionary principles to explore large solution spaces efficiently, GAs can identify biologically relevant gene sets, optimize pathway clustering, and enhance the sensitivity and specificity of enrichment detection. The protocols and visualizations provided in this application note offer practical guidance for implementing GA-enhanced pathway analysis, enabling researchers to extract more meaningful biological insights from complex high-throughput data. As pathway analysis continues to evolve, genetic algorithms will play an increasingly important role in addressing the computational and statistical challenges of interpreting biological systems.

Multi-context Pathway Modeling Across Cancer Types and Populations

Cancer progression is driven by genetic mutations that disrupt key cellular signaling pathways. However, these disruptions do not present uniformly across all patients or cancer types. The heterogeneity of driver pathways across populations with distinct clinical characteristics—including geographic origin, age, and exposure to lifestyle risk factors—remains inadequately characterized, presenting a significant challenge for personalized oncology [27] [28]. Understanding this heterogeneity is essential for developing context-aware therapeutic strategies.

Computational models, particularly optimization algorithms, are crucial for deciphering this complexity. Genetic algorithms (GAs), a class of evolutionary computation, have emerged as powerful tools for solving complex optimization problems in network medicine [29]. Their application to signaling pathway research enables the identification of minimal intervention sets for network control and the discovery of cancer driver pathways through efficient exploration of vast biological solution spaces. This protocol details the application of multi-context pathway modeling to uncover common and specific mechanisms across diverse cancer populations, with a specific focus on integrating genetic algorithm frameworks.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential research reagents and computational resources for multi-context pathway modeling.

| Item Name | Type | Function/Application | Specific Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA/ICGC Data Portals | Data Repository | Source of pan-cancer genomic profiles and clinical data | Provides somatic mutation, CNV, and clinical data for 23+ cancer types [27] [30] |

| IntOGen Driver Gene Compendium | Gene Set | Curated list of 568 cancer driver genes | Provides a biologically significant gene background for pathway search [27] [28] |

| EntCDP & ModSDP Models | Algorithm | Identifies common and specific driver pathways | Uses information entropy and modified mutual exclusivity [27] [28] |

| Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) Algorithm | Optimization Algorithm | Multi-objective identification of cancer driver pathways | Optimizes for patient coverage and gene network correlation [31] |

| ActivePathways | Software Tool | Integrative pathway enrichment across multi-omics data | Uses statistical data fusion (Brown's method) [30] |

| GDSC/PCAWG Cohorts | Data Repository | Drug sensitivity and whole-genome data | Useful for validation and linking pathways to therapeutic response [30] |

Application Notes: Key Findings and Data

Multi-context analysis of cancer genomic datasets reveals distinct pathway activation patterns stratified by patient geography, clinical cancer subtypes, age, and lifestyle factors.

Table 2: Select context-specific pathway dysregulation findings from pan-cancer analysis.

| Context Stratification | Cancer Type(s) | Common/Enriched Pathway Findings | Specific/Divergent Pathway Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic Region | Bladder Cancer | - | PI3K-Akt pathway (Chinese patients); GPCR pathway (American patients) [27] |

| Cancer Subtype | Lung Cancer | - | mTOR signaling (Lung Adenocarcinoma); FoxO signaling (Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma) [27] |

| Age Group | Glioblastoma (GBM) & AML | - | PAK signaling (Pediatric GBM); Ras signaling (Pediatric AML) [27] [28] |

| Lifestyle Risk Factor | Multiple Cancers | - | Notch-mediated pathways (Alcohol consumption); CDKN-regulated pathways (Obesity-related cancers) [27] |

| Molecular Alteration | 47 PCAWG Cohorts | Apoptotic signaling, Mitotic cell cycle (Coding mutations) [30] | Embryo development, Repression of WNT targets (Integrated coding & non-coding mutations) [30] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Multi-Context Driver Pathway Identification with EntCDP and ModSDP

This protocol uses the EntCDP and ModSDP models to identify driver pathways from mutation data across defined patient contexts [27] [28].

Input Requirements:

- Data: Somatic mutation matrices (e.g., MAF files) from cohorts like TCGA or ICGC. Clinical metadata for patient stratification (region, age, subtype, risk factors).

- Genes: A pre-defined set of candidate driver genes (e.g., the 568 IntOGen genes).

- Software: MATLAB package for EntCDP and ModSDP, available from the provided GitHub repository.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Download and harmonize mutation data from chosen platforms (TCGA, ICGC, cBioPortal). Filter out silent mutations and retain samples with at least one non-silent alteration event (e.g., somatic mutation, INDEL, CNV) [27] [28].

- Patient Stratification: Annotate samples using clinical data to create context-specific cohorts for comparison. Examples include:

- Regional: Group patients from China (CN), Australia (AU), and the United States (US) with the same cancer type.

- Subtype: Compare Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD) vs. Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma (LUSC).

- Age-based: Separate pediatric from adult samples for GBM and AML.

- Risk-based: Create groups based on smoking, alcohol, or obesity status [27] [28].

- Model Application:

- For common pathways shared across compared cohorts (e.g., US and CN bladder cancer), apply the EntCDP model. This entropy-based model maximizes coverage and mutual exclusivity to find shared driver gene sets [27] [28].

- For specific pathways enriched in one cohort relative to others (e.g., pediatric vs. adult AML), apply the ModSDP model. This model identifies gene sets with high coverage and exclusivity in the focal cohort(s) [27] [28].

- Validation and Interpretation:

Protocol B: Genetic Algorithm for Network Control in Drug Repurposing

This protocol uses a genetic algorithm to identify a minimal set of FDA-approved drug targets that can gain control over a disease-specific protein-protein interaction network, a strategy for computational drug repurposing [29].

Input Requirements:

- Network: A directed protein-protein interaction (PPI) network relevant to the cancer of interest (e.g., from SIGNOR or UniProtKB).

- Targets: A set of disease-essential genes (e.g., from CRISPR screens) as the control targets.

- Preferred Inputs: A set of genes that are targets of FDA-approved drugs (e.g., from DrugBank).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Problem Formulation: Define the network controllability problem. The goal is to find a set of input nodes (from the preferred drug targets) that can achieve structural target control over the disease-essential genes [29].

- Initialization: Generate an initial population of candidate solutions. Each solution is a set of potential input nodes, initially created by selecting one node from the predecessors of each target node within a set distance [29].

- Fitness Evaluation: Check if each candidate solution (set of input nodes) satisfies the Kalman rank condition for structural controllability over the target set. Discard any solution that fails this condition [29].

- Evolutionary Search:

- Selection: Retain solutions with the smallest number of input nodes and those that maximize the use of preferred FDA-approved drug targets.

- Crossover: Create new candidate solutions by combining parts (input nodes) of two parent solutions from the current population.

- Mutation: Generate new candidates by randomly adding or removing input nodes from existing solutions, ensuring the new sets are also checked for controllability [29].

- Termination and Output: Repeat the evolutionary steps for a predefined number of generations or until convergence. The output is a set of minimal input node sets that control the disease network and are enriched for druggable targets [29].

Protocol C: Integrative Multi-Omics Pathway Enrichment with ActivePathways

This protocol uses the ActivePathways tool to integrate evidence from multiple omics datasets to discover enriched pathways that may be missed by single-dataset analysis [30].

Input Requirements:

- Omics Data: A table of P-values with genes in rows and different omics datasets in columns (e.g., p-values from mutation burden, CNV, differential expression).

- Pathways: A collection of gene sets (e.g., GO Biological Processes, Reactome pathways).

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Fusion: For each gene, combine significance scores (P-values) from multiple omics datasets using Brown's extension of Fisher's combined probability test. This method accounts for dependencies between datasets [30].

- Gene List Creation: Rank genes by their integrated significance and apply a lenient cutoff (e.g., unadjusted combined P-value < 0.1) to create a candidate gene list for enrichment analysis [30].

- Integrative Enrichment Analysis: Perform pathway enrichment analysis on the ranked, integrated gene list using a ranked hypergeometric test. Identify significantly enriched pathways after multiple testing correction (e.g., Q-value < 0.05) [30].

- Evidence Attribution: Re-analyze the gene lists from each individual omics dataset to determine which specific dataset(s) provided evidence for the pathways discovered in the integrated analysis. This highlights pathways that are only apparent through data fusion [30].

The protocols outlined herein provide a framework for applying advanced computational models, including genetic algorithms, to the critical task of mapping cancer pathway heterogeneity. The consistent finding of context-specific pathway dysregulation underscores the limitations of a one-size-fits-all model of cancer biology and therapy. By stratifying patients based on clinical and molecular contexts, researchers can prioritize therapeutic targets that are more likely to be effective in defined patient groups, thereby accelerating the development of personalized cancer treatments. The integration of these computational approaches with experimental validation will be essential for translating these insights into clinical practice.

Implementation Strategies: Deploying Genetic Algorithms for Pathway Discovery and Drug Optimization

Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithms (MOGAs) for Balancing Efficacy, Safety, and Specificity

Application Notes

The optimization of cancer immunotherapies requires balancing multiple, often competing objectives: maximizing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target toxicity and ensuring high specificity for tumor cells. The cGAS-STING pathway has emerged as a promising innate immune signaling axis that detects cytoplasmic DNA and drives potent anti-tumor immune responses through type I interferon production [32] [33]. However, clinical application faces challenges including poor bioavailability of STING agonists, widespread inflammation at high doses, and insufficient tumor-specific targeting [34] [32]. Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithms (MOGAs) provide a computational framework to navigate this complex optimization landscape by simultaneously evolving solutions across multiple fitness objectives, enabling the identification of Pareto-optimal therapeutic parameters that balance these critical constraints.

MOGA-Optimized cGAS-STING Immunotherapy

Recent advances in cGAS-STING activation strategies demonstrate the critical need for multi-objective optimization. Messenger RNA delivery of cGAS to tumor cells represents a promising approach that harnesses the tumor's own machinery to produce the STING activator cGAMP, resulting in enhanced local immune activation with reduced systemic toxicity [33]. In murine melanoma models, this approach combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors achieved complete tumor eradication in 30% of mice, demonstrating superior efficacy over either treatment alone [33]. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) offer another tunable platform for cGAS-STING agonist delivery, leveraging their large surface area and adjustable porosity to enhance bioavailability and tumor accumulation [34]. MOGA optimization can identify ideal MOF physicochemical properties—including particle size, surface charge, and release kinetics—that simultaneously maximize tumor delivery efficiency while minimizing off-target accumulation.

Table 1: Key Parameters for MOGA Optimization of cGAS-STING Immunotherapies

| Optimization Parameter | Efficacy Objective | Safety Objective | Specificity Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanocarrier Size | Enhanced tumor penetration (<100nm) | Reduced liver sequestration (>10nm) | Tumor ECM matching (20-200nm) |

| Surface Charge | Enhanced cellular uptake (slightly positive) | Reduced protein opsonization (neutral) | Tumor cell targeting (ligand-functionalized) |

| Drug Release Kinetics | Sustained IFN-I production (>24h) | Avoid burst release inflammation (controlled) | pH/enzyme-triggered (tumor microenvironment) |

| Dosing Frequency | Maximum T-cell priming (multi-dose) | Minimize cytokine storm (spaced) | Adaptive scheduling (biomarker-guided) |

| Immune Checkpoint Combination | Synergistic tumor regression (anti-PD-1) | Reduced immune-related adverse events (timing) | Spatial co-targeting (tumor microenvironment) |

Quantitative Analysis of Optimization Trade-offs

Statistical analysis of high-dimensional therapeutic data presents particular challenges for evaluating multi-objective outcomes. Sparse multivariate methods such as sparse partial least squares (SPLS) have demonstrated superior performance in analyzing correlated outcome measures common in immunotherapy studies, maintaining high positive predictive value while minimizing false positives compared to univariate approaches [35]. This statistical framework is particularly suitable for MOGA implementation, where algorithm fitness functions must accurately capture complex relationships between therapeutic parameters and multiple outcome measures without overemphasizing correlated but non-causal variables.

Table 2: Statistical Performance Comparison for Multi-Objective Therapeutic Analysis

| Statistical Method | Sample Size (N=200) | Sample Size (N=1000) | High-Dimensional Data (M=2000) | PPV (Binary Outcome) | False Positive Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate (FDR) | Moderate power | High false positive rate | Poor performance | 0.72 | Low |

| LASSO | Good performance | Excellent performance | Good variable selection | 0.85 | Moderate |

| SPLS | Reduced PPV | Best performance | Best performance | 0.89 | High |

| Random Forest | Moderate power | Good performance | Limited variable selection | 0.78 | Moderate |

| Principal Component Regression | Good performance | Good performance | Limited interpretation | 0.81 | Moderate |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: MOGA-Optimized mRNA-cGAS Lipid Nanoparticle Formulation

Reagents and Equipment

- mRNA encoding cGAS: In vitro transcribed, nucleoside-modified mRNA with 5' cap and 3' polyA tail

- Ionizable lipid library: Structurally diverse lipids (C12-16 tail lengths, various headgroups)

- Helper lipids: DSPC, cholesterol, DMG-PEG2000

- Microfluidic mixer: Precision NanoSystems NanoAssemblr or equivalent

- Dynamic light scattering instrument: For size and PDI measurement

- Cell lines: B16-F10 melanoma, CT26 colon carcinoma, primary immune cells

- Animal model: C57BL/6 mice, syngeneic tumor models

Lipid Nanoparticle Formulation Optimization

Design of Experiments: Create initial population of 100 LNP formulations using Latin hypercube sampling across 5-dimensional parameter space:

- Ionizable lipid:mRNA ratio (10:1 to 50:1, w/w)

- Lipid composition (ionizable:helper:PEG ratio)

- Flow rate ratio (aqueous:organic 1:1 to 5:1)

- Total flow rate (5-20 mL/min)

- Buffer pH (4.0-6.5)

High-throughput formulation: Prepare LNP library using microfluidic mixing with specified parameters for each formulation.

Characterization: Measure size (target 50-100nm), PDI (<0.2), encapsulation efficiency (>90%), and mRNA integrity for each formulation.

MOGA Implementation:

- Population size: 100 formulations per generation

- Fitness objectives:

- Efficacy: IFN-β production in tumor cells (pg/mL, maximize)

- Safety: IFN-β production in healthy cells (pg/mL, minimize)

- Specificity: Tumor cell uptake vs. healthy cell uptake (ratio, maximize)

- Genetic operators: Simulated binary crossover (probability=0.9), polynomial mutation (probability=0.1)

- Termination criterion: <5% improvement in hypervolume over 10 generations

Validation: Test Pareto-optimal formulations in vitro and in vivo, measuring tumor growth inhibition, immune cell infiltration, and systemic cytokine levels.

Protocol: In Vivo Evaluation of MOGA-Optimized cGAS-STING Therapy

Tumor Implantation and Treatment

- Implant 5×10^5 B16-F10 melanoma cells subcutaneously in C57BL/6 mice (Day 0).

- Randomize mice into treatment groups (n=8-10) when tumors reach 50-100mm³ (Day 7-10).

- Administer MOGA-optimized LNP formulations intratumorally every 3 days for 3 treatments:

- Group 1: PBS control

- Group 2: Empty LNPs

- Group 3: Non-optimized mRNA-cGAS LNPs

- Group 4: MOGA-optimized mRNA-cGAS LNPs

- Group 5: MOGA-optimized mRNA-cGAS LNPs + anti-PD-1 (200μg, IP, days 1,4,7)

Efficacy and Safety Assessment

- Tumor monitoring: Measure tumor dimensions every 2 days using digital calipers. Calculate volume as (length × width²)/2.

- Survival tracking: Monitor mice for humane endpoints (tumor volume >1500mm³ or ulceration).

- Immunological analysis (Day 21):

- Collect tumors, digest to single-cell suspension, and analyze by flow cytometry for CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, Tregs, dendritic cells, and macrophages.

- Measure cytokine levels in tumor homogenates (IFN-β, CXCL10, IL-6) and serum (for systemic toxicity assessment).

- Perform immunohistochemistry for CD3+ T cell infiltration and tumor cell apoptosis (TUNEL staining).

- Toxicity evaluation:

- Monitor body weight daily.

- Assess liver and kidney function (serum ALT, BUN).

- Score systemic inflammation signs (posture, activity, piloerection).

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Visualization

Diagram 1: MOGA-Optimized cGAS-STING Immunotherapy Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions