Optimizing Biochemical Models with Particle Swarm Optimization: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to calibrate and validate complex biochemical models.

Optimizing Biochemical Models with Particle Swarm Optimization: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on applying Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to calibrate and validate complex biochemical models. It covers foundational PSO principles tailored for biological systems, details methodological implementation for parameter estimation, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and presents rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing current research and practical case studies, this resource demonstrates how PSO's powerful global search capabilities can overcome traditional limitations in biochemical model parameterization, leading to more accurate, reliable, and clinically relevant computational models.

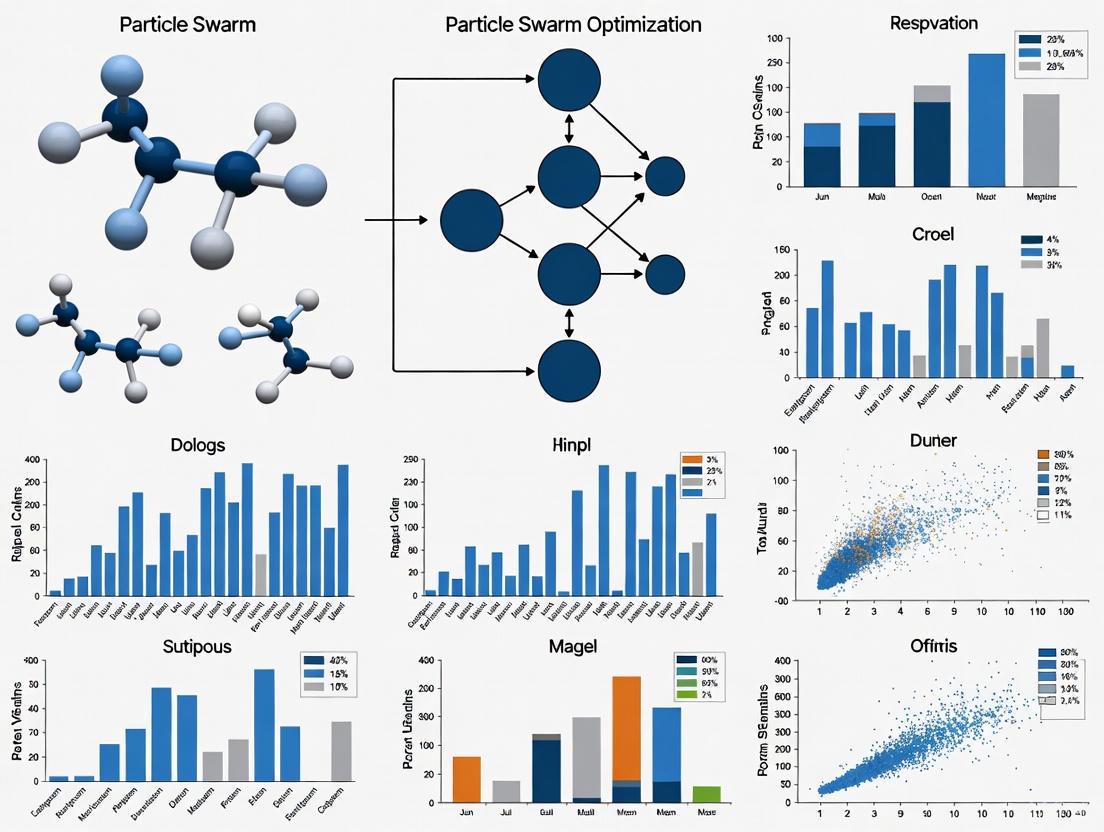

PSO Fundamentals: Bridging Swarm Intelligence and Biochemical Systems

Core Principles of Particle Swarm Optimization and Biological Inspiration

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is a population-based stochastic optimization technique inspired by the collective intelligence of social organisms, first developed by Kennedy and Eberhart in 1995 [1] [2]. The algorithm simulates the social dynamics observed in bird flocking and fish schooling, where individuals in a group coordinate their movements to efficiently locate resources such as food [2]. In PSO, potential solutions to an optimization problem, called particles, navigate through the search space by adjusting their positions based on their own experience and the collective knowledge of the swarm [1]. This bio-inspired approach has become one of the most widely used swarm intelligence algorithms due to its simplicity, efficiency, and applicability to a wide range of complex optimization problems [3] [2].

The biological foundation of PSO lies in the concept of swarm intelligence, where simple agents following basic rules give rise to sophisticated global behavior through local interactions [1] [4]. Natural systems such as bird flocks, fish schools, and insect colonies demonstrate remarkable capabilities for problem-solving, adaptation, and optimization without centralized control [4] [5]. PSO captures these principles through a computational model that balances individual exploration with social exploitation, enabling efficient search through high-dimensional, non-linear solution spaces commonly encountered in biochemical and pharmaceutical research [3] [6].

Biological Foundations and Algorithmic Principles

Natural Inspiration and Social Behavior

The PSO algorithm draws direct inspiration from the collective behavior observed in animal societies. In nature, bird flocks and fish schools exhibit sophisticated group coordination that enhances their ability to locate food sources and avoid predators [2]. Individual members maintain awareness of their neighbors' positions and velocities while simultaneously remembering their own successful locations [1]. This dual memory system forms the biological basis for PSO's two fundamental components: the cognitive component (personal best) and social component (global best) [2].

The algorithm conceptualizes particles as simple agents that represent potential solutions within the search space. Each particle adjusts its trajectory based on both its personal historical best performance and the best performance discovered by its neighbors [1] [2]. This social sharing of information mimics the communication mechanisms observed in natural swarms, where successful discoveries by individual members quickly propagate throughout the group, leading to emergent intelligent search behavior [3] [4].

Mathematical Formalization

The core PSO algorithm operates through iterative updates of particle velocities and positions. For each particle i in the swarm at iteration t, the velocity update equation is:

V→t+1i = V→ti + φ1R1ti(p→ti - x→ti) + φ2R2ti(g→t - x→ti) [2]

Where:

V→t+1irepresents the new velocity vector for particle iV→tiis the current velocity vectorφ1andφ2are acceleration coefficients (cognitive and social weights)R1tiandR2tiare uniformly distributed random vectorsp→tiis the personal best position of particle ig→tis the global best position found by the entire swarmx→tiis the current position of particle i

The position update is then calculated as:

x→t+1i = x→ti + V→t+1i [2]

In the original PSO algorithm, both cognitive and social acceleration coefficients (φ1 and φ2) were typically set to 2, balancing the influence of individual and social knowledge [2]. The random vectors R1ti and R2ti maintain diversity in the search process, preventing premature convergence to local optima—a critical consideration for complex biochemical landscapes with multiple minima [3] [2].

Neighborhood Topologies

PSO implementations utilize different communication topologies that define how information flows through the swarm. The gbest (global best) model connects all particles to each other, creating a fully connected social network where the best solution found by any particle is immediately available to all others [2]. This promotes rapid convergence but may increase susceptibility to local optima. In contrast, the lbest (local best) model restricts information sharing to defined neighborhoods, creating partially connected networks that can maintain diversity for longer periods and explore more thoroughly before converging [2].

Table 1: PSO Neighborhood Topologies and Characteristics

| Topology Type | Information Flow | Convergence Speed | Diversity Maintenance | Best Suited Problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Best (gbest) | Fully connected; all particles share information | Fast convergence | Lower diversity; higher premature convergence risk | Unimodal, smooth landscapes |

| Local Best (lbest) | Restricted to neighbors; segmented information flow | Slower, more deliberate convergence | Higher diversity; better local optima avoidance | Multimodal, complex landscapes |

| Von Neumann | Grid-based connections; balanced information flow | Moderate convergence | Good diversity maintenance | Mixed landscape types |

| Ring | Each particle connects to immediate neighbors only | Slowest convergence | Maximum diversity preservation | Highly multimodal problems |

PSO Variants and Enhancements for Biochemical Applications

Advanced PSO Formulations

Recent advances in PSO have produced specialized variants that address specific challenges in biochemical optimization. Biased Eavesdropping PSO (BEPSO) introduces interspecific communication dynamics inspired by animal eavesdropping behavior, where particles can exploit information from different "species" or subpopulations [3]. This approach enhances diversity by allowing particles to make cooperation decisions based on cognitive bias mechanisms, significantly improving performance on high-dimensional problems [3]. Altruistic Heterogeneous PSO (AHPSO) incorporates energy-driven altruistic behavior, where particles form lending-borrowing relationships based on judgments of "credit-worthiness" [3]. This bio-inspired altruism delays diversity loss and prevents premature convergence, making it particularly valuable for complex biochemical model calibration [3].

Bare Bones PSO (BBPSO) eliminates the velocity update equation, instead generating new positions using a Gaussian distribution based on the personal and global best positions [1]. Quantum PSO (QPSO) incorporates quantum mechanics principles to enhance global search capabilities, while Adaptive PSO (APSO) techniques dynamically adjust parameters during the optimization process to maintain optimal exploration-exploitation balance [1].

Hybrid PSO Approaches

Hybridization with other optimization techniques has produced powerful variants for biochemical applications. The integration of PSO with gradient-based methods creates a robust framework for biological model calibration, combining PSO's global search capabilities with local refinement from gradient descent [7]. PSO-GA hybrids incorporate evolutionary operators like mutation and crossover to enhance diversity, while PSO-neural network hybrids enable simultaneous feature selection and model optimization for biomedical diagnostics [1] [8].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of PSO Variants on Benchmark Problems

| PSO Variant | CEC'13 30D | CEC'13 50D | CEC'13 100D | CEC'17 50D | CEC'17 100D | Constrained Problems | Computational Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEPSO | Statistically better than 10/15 algorithms | Statistically better than 10/15 algorithms | Statistically better than 10/15 algorithms | Statistically better than 11/15 algorithms | Statistically better than 11/15 algorithms | 1st place mean rank | Moderate |

| AHPSO | Statistically better than 10/15 algorithms | Statistically better than 10/15 algorithms | Statistically better than 10/15 algorithms | Statistically better than 11/15 algorithms | Statistically better than 11/15 algorithms | 3rd place mean rank | Moderate |

| Standard PSO | Baseline performance | Baseline performance | Baseline performance | Baseline performance | Baseline performance | Middle ranks | Low |

| L-SHADE | Competitive | Competitive | Competitive | Competitive | Competitive | Not specified | High |

| I-CPA | Competitive | Competitive | Competitive | Competitive | Competitive | Not specified | High |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Standard PSO Implementation Protocol

Protocol 1: Basic PSO for Biochemical Model Parameter Estimation

Objective: Calibrate parameters of a biochemical kinetic model using standard PSO.

Materials and Setup:

- Optimization Framework: Python with PySwarms or MATLAB with PSO Toolbox

- Population Size: 20-50 particles (problem-dependent)

- Parameter Bounds: Defined based on biochemical constraints

- Computational Resources: Multi-core processor for parallel fitness evaluation

Procedure:

- Initialization Phase:

- Define search space boundaries based on biologically plausible parameter ranges

- Initialize particle positions uniformly random within boundaries

- Initialize particle velocities with small random values

- Set cognitive (c₁) and social (c₂) parameters to 2.0

- Set inertia weight (ω) to 0.9 for initial exploration

Iteration Phase:

- For each particle, simulate biochemical model with current parameters

- Calculate fitness (e.g., sum of squared errors between model and experimental data)

- Update personal best (pbest) if current position yields better fitness

- Identify global best (gbest) position across entire swarm

- Update velocities: vᵢ = ωvᵢ + c₁r₁(pbestᵢ - xᵢ) + c₂r₂(gbest - xᵢ)

- Update positions: xᵢ = xᵢ + vᵢ

- Apply boundary constraints to keep particles within feasible region

Termination Phase:

- Continue iterations until maximum generations (100-500) reached

- OR until fitness improvement falls below threshold (1e-6) for 10 consecutive iterations

- Return global best solution as optimized parameter set

Validation:

- Perform cross-validation with withheld experimental data

- Assess parameter identifiability through sensitivity analysis

- Compare with traditional gradient-based optimization methods

BEPSO Protocol for Complex Biochemical Landscapes

Protocol 2: Biased Eavesdropping PSO for Multimodal Optimization

Objective: Locate multiple promising regions in complex biochemical response surfaces.

Specialized Materials:

- Algorithm Implementation: Custom BEPSO based on [3]

- Subpopulation Management: Kernel-based clustering for species identification

- Eavesdropping Probability Matrix: Controls information flow between subpopulations

Procedure:

- Heterogeneous Population Initialization:

- Initialize swarm with diverse behavioral strategies

- Define eavesdropping probability matrix for interspecific communication

- Establish cognitive bias parameters for cooperation decisions

Multi-modal Search Phase:

- Evaluate particles using biochemical objective function

- Identify distinct subpopulations based on spatial and behavioral characteristics

- Update personal best positions within species context

- Apply eavesdropping mechanism: particles access information from other species

- Implement biased decision-making: particles choose whether to cooperate based on perceived benefit

- Update velocities and positions with species-specific parameters

Diversity Maintenance:

- Monitor population diversity using genotypic diversity measures

- Trigger niching mechanisms if diversity drops below threshold

- Maintain archive of promising solutions from different regions

Solution Refinement:

- Apply local search to promising regions identified through eavesdropping

- Return diverse set of high-quality solutions for further biochemical validation

PSO-FeatureFusion Protocol for Bioinformatic Applications

Protocol 3: Integrated Feature Selection and Model Optimization

Objective: Simultaneously optimize feature selection and classifier parameters for biomedical prediction tasks [9] [8].

Materials:

- Biological Datasets: Transcriptomic, proteomic, or clinical data

- Feature Preprocessing: Normalization and dimensionality reduction tools

- PSO Framework: Modified for multi-objective optimization

Procedure:

- Feature Standardization:

- Apply PCA or autoencoders to address dimensional mismatch [9]

- Transform heterogeneous features into unified similarity matrices

- Handle data sparsity through similarity-based representations

Unified Optimization:

- Encode both feature subsets and classifier parameters in particle position

- Define composite fitness function: accuracy + regularization + feature sparsity

- Implement constraint handling for feasible solutions

Swarm Intelligence:

- Initialize population with random feature subsets and parameters

- Evaluate particles using cross-validation on training data

- Update positions using constrained PSO velocity updates

- Apply binary conversion for feature selection components

Model Validation:

- Assess final model on independent test set

- Compare with traditional sequential feature selection approaches

- Perform statistical significance testing

Application to Biochemical Model Calibration

Kinetic Parameter Estimation

PSO has demonstrated exceptional capability in calibrating complex biochemical models where traditional gradient-based methods struggle with non-identifiability and local optima [7] [6]. In kinetic model calibration, PSO efficiently explores high-dimensional parameter spaces to minimize the discrepancy between model simulations and experimental data [7]. The hybrid PSO-gradient approach combines the global perspective of swarm intelligence with local refinement capabilities, creating a robust optimization pipeline for systems biology applications [7].

The algorithm's ability to handle non-differentiable objective functions is particularly valuable for biochemical systems with discontinuous behaviors or stochastic dynamics [6]. Furthermore, PSO does not require good initial parameter estimates, making it suitable for novel biological systems where prior knowledge is limited [2] [6].

Drug Discovery and Biomarker Identification

In pharmaceutical applications, PSO enhances drug discovery pipelines through efficient optimization of molecular properties and binding affinities [6]. The PSO-FeatureFusion framework enables integrated analysis of heterogeneous biological data, capturing complex interactions between drugs, targets, and disease pathways [9]. For Parkinson's disease diagnosis, PSO-optimized models achieved 96.7-98.9% accuracy by simultaneously selecting relevant vocal biomarkers and tuning classifier parameters [8].

Table 3: PSO Performance in Biomedical Applications

| Application Domain | Dataset Characteristics | PSO Performance | Comparative Baseline | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parkinson's Disease Diagnosis [8] | 1,195 records, 24 features | 96.7% accuracy, 99.0% sensitivity, 94.6% specificity | 94.1% (Bagging classifier) | Unified feature selection and parameter tuning |

| Parkinson's Disease Diagnosis [8] | 2,105 records, 33 features | 98.9% accuracy, AUC=0.999 | 95.0% (LGBM classifier) | Robustness to feature dimensionality |

| Drug-Drug Interaction Prediction [9] | Multiple benchmark datasets | Competitive or superior to state-of-the-art | Deep learning and graph-based models | Dynamic feature interaction modeling |

| Biological Model Calibration [7] | Various kinetic models | Improved convergence and solution quality | Traditional gradient methods | Avoidance of local optima |

Visualization of PSO Workflows

Standard PSO Algorithm Flowchart

Hybrid PSO for Biochemical Model Calibration

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for PSO-Enhanced Biochemical Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSO Software Frameworks | Algorithm implementation and customization | Provide pre-built PSO variants and visualization tools | PySwarms (Python), MATLAB PTO, Opt4J |

| Biochemical Modeling Platforms | Simulation of biological systems for fitness evaluation | Compatibility with PSO parameter optimization | COPASI, Virtual Cell, SBML-compliant tools |

| High-Performance Computing | Parallel fitness evaluation for large swarms | Reduces optimization time for complex models | Multi-core CPUs, GPU acceleration, cloud computing |

| Data Preprocessing Tools | Handling dimensional mismatch and data sparsity | Critical for heterogeneous biological data integration | PCA, autoencoders, similarity computation [9] |

| Hybrid Optimization Controllers | Coordination between global and local search | Manages transition from PSO to gradient methods | Custom middleware, optimization workflow managers |

| Benchmark Datasets | Algorithm validation and performance comparison | Standardized assessment across methods | CEC test suites, UCI biological datasets [3] [8] |

| Visualization and Analysis | Solution quality assessment and convergence monitoring | Essential for interpreting high-dimensional results | Parallel coordinates, convergence plots, sensitivity visualization |

Why PSO is Uniquely Suited for Biochemical Model Parameterization

Parameter estimation for biochemical models presents significant challenges, including high dimensionality, multi-modality, and experimental data sparsity. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) has emerged as a particularly effective meta-heuristic for addressing these challenges due to its faster convergence speed, lower computational requirements, and flexibility in handling complex biological systems. This application note explores the unique advantages of PSO for biochemical model parameterization, provides structured comparisons of PSO variants, details experimental protocols for implementation, and visualizes key workflows. The content is specifically framed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking robust solutions for biochemical model calibration.

Biochemical model parameterization represents a critical step in systems biology, drug discovery, and metabolic engineering, where accurate parameter estimates are essential for predictive modeling. This process is typically framed as a non-linear optimization problem where the residual between experimental measurements and model simulations is minimized [10]. The complex dynamics of biological systems, coupled with noisy and often incomplete experimental data, create optimization landscapes characterized by multiple local minima that challenge traditional gradient-based methods [11] [12].

Particle Swarm Optimization, inspired by the social behavior of bird flocking and fish schooling, has demonstrated particular efficacy in this domain [13]. As a population-based stochastic algorithm, PSO views potential solutions as particles with individual velocities flying through the problem space. Each particle combines aspects of its own historical best location with those of the swarm to determine subsequent movements [13]. This collective intelligence enables effective navigation of complex parameter spaces while maintaining a favorable balance between exploration and exploitation.

The unique suitability of PSO for biochemical applications stems from several inherent advantages: faster convergence speed compared to genetic algorithms, lower computational requirements, ease of parallelization, and fewer parameters requiring adjustment [14] [13]. Furthermore, PSO's population-based structure naturally accommodates hybrid approaches that combine its global search capabilities with local refinement techniques, making it particularly valuable for addressing the multi-scale, multi-modal problems prevalent in biochemical systems [10] [11].

Comparative Analysis of PSO Variants for Biochemical Applications

Various PSO modifications have been developed specifically to address challenges in biochemical parameter estimation. The table below summarizes key variants and their performance characteristics:

Table 1: PSO Variants for Biochemical Parameter Estimation

| PSO Variant | Core Innovation | Biochemical Application | Reported Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSO-FeatureFusion [9] | Combines PSO with neural networks to integrate multiple biological features | Drug-drug interaction and drug-disease association prediction | Task-agnostic, modular, handles feature dimensional mismatch, addresses data sparsity |

| Random Drift PSO (RDPSO) [14] | Modifies velocity update equation inspired by free electron model | Parameter estimation for nonlinear biochemical dynamic systems | Better balance between global and local search, improved performance on high-dimensional problems |

| Dynamic Optimization with PSO (DOPS) [10] | Hybrid multi-swarm PSO with Dynamically Dimensioned Search | Benchmark biochemical problems and human coagulation cascade model | Near-optimal estimates with fewer function evaluations, effective on high-dimensional problems |

| Modified PSO with Decomposition [11] | Employs decomposition technique for improved exploitation | Metabolism of CAD system; E-coli models | 54.39% and 26.72% average reduction in RMSE for simulation and experimental data respectively |

| PSO with Constrained Regularized Fuzzy Inferred EKF (CRFIEKF) [12] | Integrates fuzzy inference with regularization | Glycolytic processes, JAK/STAT and Ras signaling pathways | Eliminates need for experimental time-course data, handles ill-posed problems |

These specialized PSO implementations address specific limitations of standard optimization approaches for biochemical systems. The modifications primarily focus on improving convergence properties, handling high-dimensional parameter spaces, incorporating domain knowledge, and managing noisy or sparse experimental data.

Experimental Protocols for Biochemical Parameter Estimation

General PSO Framework for Biochemical Models

The standard PSO protocol for biochemical parameter estimation involves the following steps:

Problem Formulation:

- Define the biochemical model structure (e.g., system of ODEs, S-system)

- Identify parameters to be estimated and their plausible bounds

- Formulate objective function (typically sum of squared errors between experimental and simulated data)

PSO Initialization:

- Set swarm size (typically 20-50 particles)

- Initialize particle positions randomly within parameter bounds

- Initialize particle velocities

- Set cognitive (c1) and social (c2) parameters (typically ~1.49-2.05)

- Set inertia weight (constant or decreasing)

Iteration Process:

- For each particle, simulate model with current parameter values

- Calculate objective function value

- Update personal best (pbest) and global best (gbest) positions

- Update particle velocities and positions

- Continue until convergence criteria met (max iterations, minimal improvement)

Validation:

- Validate optimized parameters with withheld experimental data

- Perform sensitivity analysis to assess parameter identifiability

The Dynamic Optimization with Particle Swarms (DOPS) protocol combines multi-swarm PSO with Dynamically Dimensioned Search:

Multi-Swarm Initialization:

- Create multiple sub-swarms with distinct particle populations

- Initialize particles across parameter space using Latin Hypercube sampling

Multi-Swarm PSO Phase:

- Each sub-swarm performs independent PSO optimization

- Particles update based on sub-swarm best and global best

- Sub-swarms periodically regroup to share information

Adaptive Switching:

- Monitor rate of error convergence

- Switch to DDS phase when improvement falls below threshold for specified iterations

DDS Refinement Phase:

- Initialize DDS with globally best particle from PSO phase

- Greedily update by perturbing randomly selected parameter subsets

- Number of parameters perturbed decreases with function evaluations

Termination:

- Final solution is best parameter set found after allocated function evaluations

For integrating heterogeneous biological features (e.g., genomic, proteomic, drug, disease data):

Feature Preparation:

- Standardize feature dimensions using PCA or autoencoders

- Transform raw features into similarity matrices to address sparsity

Feature Combination:

- Systematically combine entity A (size k, n features) and entity B (size l, m features)

- Generate all possible feature pairs between entities

Model Training and Optimization:

- Model each feature pair using lightweight neural networks

- Use PSO to optimize feature contributions and interactions

- Employ modular, parallelizable design for computational efficiency

Output Integration:

- Aggregate results from multiple models into final prediction

- Maintain interpretability through explicit feature interaction modeling

Visualization of PSO Workflows in Biochemical Research

PSO-FeatureFusion Architecture

PSO-FeatureFusion Workflow for Heterogeneous Biological Data Integration

DOPS Hybrid Algorithm Flow

DOPS Hybrid Optimization Flow Combining PSO and DDS

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for PSO in Biochemical Modeling

| Category | Item | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Resources | High-performance computing cluster | Parallel processing of particle evaluations | Large-scale models requiring numerous function evaluations |

| MATLAB/Python/R environments | Implementation of PSO algorithms and biochemical models | Flexible prototyping and algorithm development | |

| SBML-compatible modeling tools | Standardized representation of biochemical models | Interoperability between modeling and optimization | |

| Data Resources | Time-course experimental data | Training data for parameter estimation | Traditional parameter estimation approaches |

| Fuzzy Inference System | Creates dummy measurement signals from imprecise relationships | CRFIEKF approach when experimental data is limited [12] | |

| Similarity matrices | Denser representations of sparse biological data | PSO-FeatureFusion for heterogeneous data integration [9] | |

| Algorithmic Resources | Tikhonov regularization | Stabilizes solutions for ill-posed problems | Handling noise and data limitations [12] |

| Dynamically Dimensioned Search | Single-solution heuristic for parameter refinement | DOPS hybrid approach for efficient convergence [10] | |

| Decomposition techniques | Enhances exploitation near final solution | Modified PSO for improved local search [11] |

Particle Swarm Optimization offers a uniquely powerful approach to biochemical model parameterization, addressing fundamental challenges including multi-modality, high dimensionality, and data sparsity. The specialized PSO variants discussed in this application note demonstrate significant improvements over conventional optimization methods, particularly through hybrid strategies that combine PSO's global search capabilities with efficient local refinement techniques. The provided protocols, visualizations, and resource guidelines offer researchers practical frameworks for implementing these advanced optimization strategies in diverse biochemical modeling contexts, from drug discovery to metabolic engineering and systems biology. As biological models continue to increase in complexity, PSO-based approaches will remain essential tools for robust parameter estimation and model validation.

Key Challenges in Biochemical Modeling That PSO Addresses

Biochemical modeling aims to build mathematical formulations that quantitatively describe the dynamical behavior of complex biological processes, such as metabolic reactions and signaling pathways. These models are typically formulated as systems of differential equations, the kinetic parameters of which must be identified from experimental data. This parameter estimation problem, also known as the inverse problem, represents a cornerstone for building accurate dynamic models that can help understand functionality at the system level [14].

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is a population-based stochastic optimization technique inspired by the social behavior of bird flocking or fish schooling. Since its inception in the mid-1990s, PSO has undergone significant advancements and has been recognized as a leading swarm-based algorithm with remarkable performance for problem-solving [1]. In biochemical modeling, PSO offers distinct advantages over traditional local optimization methods, particularly for high-dimensional, nonlinear, and multimodal problems that are characteristic of biological systems.

Key Challenges in Biochemical Modeling

Biochemical modeling presents several unique challenges that complicate parameter estimation and model calibration:

Multimodality and Non-convexity

The parameter landscapes of biochemical models typically contain multiple local optima, making it difficult for gradient-based local optimizers to find globally optimal solutions. This multimodality arises from the nonlinear nature of biochemical interactions and complex feedback mechanisms [14].

High-dimensional Parameter Spaces

Complex biochemical pathway models often involve numerous parameters that must be estimated simultaneously. For instance, a three-step pathway benchmark model contains 36 parameters, creating a challenging high-dimensional optimization problem [14].

Computational Expense

Each objective function evaluation requires solving systems of differential equations, making the optimization process computationally intensive. This challenge is compounded by the need for multiple runs to account for stochasticity in experimental data and algorithm performance [14].

Ill-conditioning and Parameter Sensitivity

Biochemical models are often ill-conditioned, with parameters exhibiting varying degrees of sensitivity. Small changes in certain parameters can lead to significant changes in system behavior, while others have minimal impact, creating a challenging optimization landscape [14].

Table 1: Key Challenges in Biochemical Modeling and PSO Solutions

| Challenge | Impact on Modeling | PSO Solution Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Multimodality | Gradient-based methods trap in local optima | Stochastic global search with population diversity |

| High-dimensionality | Curse of dimensionality; search space grows exponentially | Cooperative swarm intelligence with parallel exploration |

| Computational Expense | Long simulation times limit exploration | Efficient guided search with minimal function evaluations |

| Ill-conditioning | Parameter uncertainty and instability | Robustness to noisy and ill-conditioned landscapes |

PSO Methodologies for Biochemical Modeling

Standard PSO Algorithm

The standard PSO algorithm operates using a population of particles that navigate the search space. Each particle (i) at iteration (t) has a position (Xi^t) and velocity (Vi^t) in the D-dimensional space. The velocity and position update equations are:

[ \begin{aligned} Vi^{t+1} &= \omega Vi^t + c1 r1^t (Pi^t - Xi^t) + c2 r2^t (g^t - Xi^t) \ Xi^{t+1} &= Xi^t + Vi^{t+1} \end{aligned} ]

where (\omega) is the inertia weight, (c1) and (c2) are acceleration coefficients, (r1^t) and (r2^t) are random numbers in U(0,1), (P_i^t) is the particle's personal best position, and (g^t) is the swarm's global best position [15].

Advanced PSO Variants for Biochemical Applications

Several PSO variants have been developed specifically to address challenges in biochemical modeling:

Random Drift PSO (RDPSO): This variant incorporates a random drift term inspired by the free electron model in metal conductors placed in an external electric field. RDPSO fundamentally modifies the velocity update equation to enhance global search ability and avoid premature convergence [14].

Dynamic PSO (DYN-PSO): Designed specifically for dynamic optimization of biochemical processes, DYN-PSO enables direct calls to simulation tools and facilitates dynamic optimization tasks for biochemical engineers. It has been applied to optimize inducer and substrate feed profiles in fed-batch bioreactors [16].

Flexible Self-adapting PSO (FLAPS): This self-adapting variant addresses composite objective functions that depend on both optimization parameters and additional, a priori unknown weighting parameters. FLAPS learns these weighting parameters at runtime, yielding a dynamically evolving and iteratively refined search-space topology [17].

Constriction Factor PSO (CSPSO): This approach introduces a constriction factor to control the balance between cognitive and social components in the velocity equation, restricting particle velocities within a certain range to prevent excessive exploration or exploitation [15].

Table 2: PSO Variants for Biochemical Modeling

| PSO Variant | Key Features | Best Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|

| RDPSO | Random drift term for enhanced global search; uses exponential or Gaussian distributions | Complex parameter estimation with high risk of premature convergence |

| DYN-PSO | Direct simulation tool calls; tailored for dynamic optimization | Fed-batch bioreactor optimization; dynamic pathway modeling |

| FLAPS | Self-adapting weighting parameters; flexible objective function | Multi-response problems with conflicting quality features |

| CSPSO | Constriction factor for balanced exploration-exploitation | Well-posed problems requiring stable convergence |

| Quantum PSO | Quantum-behaved particles for improved search space coverage | Large-scale problems with extensive search spaces |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

RDPSO for Biochemical Pathway Identification

Objective: Estimate parameters of nonlinear biochemical dynamic models from time-course data [14].

Materials and Software:

- MATLAB programming environment

- Biochemical simulation toolbox (e.g., COPASI, SBtoolbox2)

- Experimental dataset (metabolite concentrations over time)

Procedure:

- Problem Formulation:

- Define the system of differential equations representing the biochemical pathway

- Specify parameters to be estimated and their feasible ranges

- Formulate objective function as sum of squared errors between experimental and simulated data

Algorithm Initialization:

- Set swarm size (typically 30-50 particles)

- Define RDPSO parameters: random drift magnitude, acceleration coefficients

- Initialize particle positions randomly within parameter bounds

- Initialize velocities to zero or small random values

Iterative Optimization:

- For each particle, simulate the biochemical model with current parameters

- Calculate objective function value

- Update personal best and global best positions

- Apply RDPSO velocity update with random drift component: [ Vi^{t+1} = \chi[\omega Vi^t + c1 r1^t (Pi^t - Xi^t) + c2 r2^t (g^t - X_i^t)] + \mathcal{D} ] where (\mathcal{D}) represents the random drift term

- Update particle positions

- Apply boundary handling if particles exceed parameter bounds

Termination and Validation:

- Run until maximum iterations reached or convergence criteria met

- Validate optimal parameters with separate test dataset

- Perform sensitivity analysis on identified parameters

FLAPS for SAXS-Guided Protein Simulations

Objective: Find functional parameters for small-angle X-ray scattering-guided protein simulations using a flexible objective function that balances multiple quality criteria [17].

Materials:

- SAXS experimental data

- Molecular dynamics simulation software (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD)

- Protein structure files

Procedure:

- Flexible Objective Function Setup:

- Define multiple response functions (e.g., SAXS fit quality, physical plausibility, structural constraints)

- Implement standardization procedure for responses: [ f(\mathbf{x}; \mathbf{z}) = \sumj \frac{Rj(\mathbf{x}) - \muj}{\sigmaj} ] where (\muj) and (\sigmaj) are updated each generation based on current response values

Self-Adapting PSO Implementation:

- Initialize population with random positions in parameter space

- For each generation:

- Evaluate all responses for each particle

- Update OF parameters ((\muj), (\sigmaj)) based on current generation's responses

- Re-evaluate fitness using updated OF parameters

- Update personal best and global best positions

- Apply velocity update with constriction or inertia weight

Parameter Space Exploration:

- Utilize dynamic velocity clamping based on search space dimensions: [ \mathbf{s}{\max} = 0.7 G^{-1} (\mathbf{b}{\text{up}} - \mathbf{b}_{\text{lo}}) ] where (G) is the maximum number of generations

Result Interpretation:

- Select best parameter set based on final fitness

- Analyze trade-offs between different response criteria

- Validate with additional SAXS experiments if possible

Diagram 1: FLAPS Workflow for SAXS-Guided Protein Simulations

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function in PSO-assisted Biochemical Modeling | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MATLAB with PSO Toolbox | Algorithm implementation and parameter tuning | Provides built-in functions for standard PSO; customizable for variants |

| COPASI | Biochemical system simulation and model analysis | Open-source; enables model simulation for objective function evaluation |

| SBtoolbox2 | Systems biology model construction and analysis | MATLAB-based; facilitates standardized model representation |

| Experimental Dataset | Time-course metabolite concentrations or protein expression levels | Used for model calibration and validation; should include sufficient time points |

| SAXS Data Processing Software | Processing and analysis of small-angle X-ray scattering data | Critical for SAXS-guided simulations; converts raw data to comparable profiles |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulation of biomolecular dynamics | GROMACS, NAMD, or AMBER for physics-based simulation |

| High-Performance Computing Cluster | Parallel execution of multiple simulations | Essential for computationally intensive parameter estimation |

Performance Analysis and Validation

Convergence Behavior

The convergence analysis of PSO algorithms remains an active research area. Recent studies have applied martingale theory and Markov chain analysis to establish theoretical convergence properties [18]. For biochemical applications, the Constriction Standard PSO (CSPSO) has demonstrated better balance between exploration and exploitation, modifying all terms of the PSO velocity equation to avoid premature convergence [15].

Comparative Performance

In comparative studies, PSO has demonstrated advantages over other global optimization methods for biochemical applications:

- Compared to Genetic Algorithms: PSO shows faster convergence speed and lower computational needs while maintaining similar or better solution quality [14]

- Compared to Simulated Annealing: PSO is more easily parallelizable and has better convergence characteristics for high-dimensional problems [14]

- Compared to Evolutionary Strategies: PSO requires fewer objective function evaluations to reach comparable solution quality [14]

Diagram 2: Performance Comparison of PSO Against Other Optimization Methods

Application Success Cases

PSO has been successfully applied to various biochemical modeling challenges:

- Thermal Isomerization of α-pinene: RDPSO successfully estimated 5 parameters from reaction data, outperforming other global optimizers especially under noisy data conditions [14]

- Three-step Pathway Model: RDPSO handled 36-parameter estimation for a complex pathway model, demonstrating scalability to high-dimensional problems [14]

- Fed-batch Bioreactor Optimization: DYN-PSO optimized inducer and substrate feed profiles to maximize production of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase [16]

- SAXS-Guided Protein Structure Determination: FLAPS effectively balanced multiple objective criteria to determine optimal parameters for structure refinement [17]

Particle Swarm Optimization addresses fundamental challenges in biochemical modeling by providing robust, efficient, and effective solutions to the parameter estimation problem. The adaptability of PSO through various specialized variants enables researchers to tackle the multimodality, high-dimensionality, and computational complexity inherent in biochemical systems. As biochemical models continue to increase in complexity and scope, PSO-based approaches offer promising pathways for extracting meaningful parameters from experimental data, ultimately enhancing our understanding of biological systems at the molecular level.

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is a population-based metaheuristic algorithm inspired by the social behavior of bird flocking and fish schooling [19]. Since its inception in the mid-1990s, PSO has undergone significant advancements, including various enhancements, extensions, and modifications [1]. In the realm of biological systems research, PSO has emerged as a powerful optimization tool for addressing complex challenges in bioinformatics, biochemical process modeling, and drug discovery. The algorithm's ability to efficiently navigate high-dimensional, multimodal search spaces makes it particularly suitable for biological applications where parameter estimation, feature integration, and model identification are paramount [14] [9]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of PSO variants specifically relevant to biological systems, detailing their mechanisms, applications, and implementation protocols to assist researchers in selecting and applying appropriate PSO strategies to their specific biological optimization problems.

Fundamental PSO Mechanism and Biological Adaptations

Core PSO Algorithm

The standard PSO algorithm operates using a population of candidate solutions, called particles, that move through the search space. Each particle adjusts its position based on its own experience and the experience of neighboring particles. The position (X) and velocity (V) of each particle are updated iteratively according to the following equations [19]:

Velocity Update:

Vk(i+1) = ωVk(i) + c1r1(pbest,ik - Xk(i)) + c2r2(gbest,i - Xk(i))

Position Update:

Xk(i+1) = Xk(i) + Vk(i+1)

Where:

Vk(i)is the velocity of particle k at iteration iXk(i)is the position of particle k at iteration iωis the inertia weight controlling the influence of previous velocityc1, c2are acceleration coefficients (cognitive and social components)r1, r2are random numbers between 0 and 1pbest,ikis the best position found by particle k so fargbest,iis the best position found by the entire swarm so far

PSO Adaptations for Biological Systems Complexity

Biological systems present unique challenges including high dimensionality, nonlinear dynamics, data sparsity, and heterogeneous feature spaces that require specialized PSO adaptations [9] [14]. The inherent noise in biological measurements and the often multi-modal nature of biological optimization landscapes further complicate the application of standard optimization approaches. PSO variants address these challenges through enhanced exploration-exploitation balance, specialized boundary handling, and mechanisms to maintain population diversity throughout the optimization process.

Table 1: Key Challenges in Biological Systems and PSO Adaptation Strategies

| Biological Challenge | PSO Adaptation Strategy | Representative Variants |

|---|---|---|

| High-dimensional parameter spaces | Velocity clamping, Dimension-wise learning | RDPSO [14] |

| Noisy biological measurements | Robust fitness evaluation, Statistical measures | PSO-FeatureFusion [9] |

| Multi-modal fitness landscapes | Niching, Multi-swarm approaches | BEPSO, AHPSO [20] |

| Dynamic system behaviors | Adaptive inertia weight, Re-initialization | DYN-PSO [16] |

| Computational complexity | Surrogate modeling, Hybrid approaches | BPSO-RL [21] |

Key PSO Variants for Biological Applications

Random Drift PSO (RDPSO) for Biochemical Systems Identification

The Random Drift PSO (RDPSO) represents a significant advancement for parameter estimation in nonlinear biochemical dynamical systems [14]. This variant incorporates principles from the free electron model in metal conductors under external electric fields, fundamentally modifying the particle velocity update equation to enhance global search capabilities. RDPSO replaces the traditional velocity components with a random drift term, enabling more effective navigation of complex, high-dimensional parameter spaces common in biochemical models. The exponential distribution-based sampling in RDPSO's novel variant provides superior performance for estimating parameters of complex dynamic pathways, including those with 36+ parameters, under both noise-free and noisy data scenarios [14].

PSO-FeatureFusion for Heterogeneous Biological Data Integration

PSO-FeatureFusion addresses the critical challenge of integrating heterogeneous biological data sources—such as genomic, proteomic, drug, and disease data—through a unified framework that combines PSO with neural networks [9]. This approach dynamically models pairwise feature interactions and learns their optimal contributions in a task-agnostic manner. The method transforms raw features into similarity matrices to mitigate data sparsity and employs dimensionality reduction techniques (PCA or autoencoders) to handle feature dimensional mismatches across entities. Applied to drug-drug interaction and drug-disease association prediction, PSO-FeatureFusion has demonstrated robust performance across multiple benchmark datasets, matching or outperforming state-of-the-art deep learning and graph-based models [9].

Bio PSO (BPSO) with Reinforcement Learning for Dynamic Environments

The Bio PSO (BPSO) algorithm modifies the velocity update equation using randomly generated angles to enhance searchability and avoid premature convergence [21]. When integrated with Q-learning reinforcement learning (as BPSO-RL), this approach combines global path planning capabilities with local adaptability to dynamic obstacles. While initially applied to automated guided vehicle navigation, the BPSO-RL framework shows significant promise for biological applications requiring adaptation to dynamic environments, such as real-time optimization of bioprocesses or adaptive experimental design in high-throughput screening [21].

Biased Eavesdropping PSO (BEPSO) and Altruistic Heterogeneous PSO (AHPSO)

Inspired by interspecific eavesdropping behavior in animal communication, BEPSO enables particles to dynamically access and exploit information from distinct groups or species within the swarm [20]. This creates heterogeneous behavioral dynamics that enhance exploration in complex fitness landscapes. AHPSO incorporates conditional altruistic behavior where particles form lending-borrowing relationships based on "energy" and "credit-worthiness" assessments [20]. Both algorithms have demonstrated statistically significant superiority over numerous comparator algorithms on high-dimensional problems (CEC'13, CEC'14, CEC'17 test suites), particularly maintaining population diversity without sacrificing convergence efficiency—a critical advantage for biological optimization problems with complex, constrained search spaces [20].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of PSO Variants on Biological and Benchmark Problems

| PSO Variant | Key Mechanism | Theoretical Basis | Reported Performance Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDPSO [14] | Random drift with exponential distribution | Free electron model in physics | Better quality solutions for biochemical parameter estimation than other global optimizers |

| PSO-FeatureFusion [9] | PSO with neural networks for feature interaction | Similarity-based feature transformation | Matches or outperforms state-of-the-art deep learning and graph models on bioinformatics tasks |

| BEPSO/AHPSO [20] | Eavesdropping and altruistic behaviors | Animal communication and evolutionary dynamics | Statistically superior to 11 of 15 comparator algorithms on CEC17 50D-100D problems |

| BPSO-RL [21] | Angle-based velocity update with Q-learning | Swarm intelligence with reinforcement learning | Great performance in unimodal problems, best fitness with fewer iterations |

Experimental Protocols for Biological Applications

Protocol 1: Parameter Estimation for Biochemical Dynamic Systems Using RDPSO

Application Scope: This protocol details the application of Random Drift PSO for estimating parameters of nonlinear biochemical dynamical systems, such as metabolic pathways and signaling cascades [14].

Materials and Reagents:

- Experimental time-course data for biochemical species concentrations

- Mathematical model structure defining the system of differential equations

- Computational environment with RDPSO implementation (MATLAB, Python, or R)

Procedure:

- Problem Formulation:

- Define the system of ordinary differential equations representing the biochemical network

- Identify parameters to be estimated and define their plausible ranges based on biological constraints

- Formulate the objective function as the sum of squared errors between experimental data and model simulations

RDPSO Configuration:

- Initialize swarm size (typically 50-100 particles)

- Set random drift parameters based on problem dimensionality

- Define stopping criteria (maximum iterations or convergence threshold)

Optimization Execution:

- Distribute initial particle positions uniformly across parameter space

- For each iteration:

- Simulate the model for each particle's parameter set

- Calculate objective function value for each particle

- Update personal best and global best positions

- Apply random drift velocity update

- Update particle positions

- Continue until stopping criteria met

Validation:

- Perform cross-validation with withheld experimental data

- Assess parameter identifiability through profile likelihood or bootstrap analysis

- Validate biological plausibility of estimated parameters

Troubleshooting:

- For premature convergence, increase swarm size or adjust drift parameters

- For slow convergence, implement adaptive parameter control

- For parameter identifiability issues, incorporate regularization terms or prior knowledge

Protocol 2: Heterogeneous Biological Data Integration Using PSO-FeatureFusion

Application Scope: This protocol describes the implementation of PSO-FeatureFusion for integrating diverse biological data types (genomic, proteomic, drug, disease) to predict relationships such as drug-drug interactions or drug-disease associations [9].

Materials and Reagents:

- Heterogeneous biological datasets (e.g., drug chemical structures, disease phenotypes, protein-protein interactions)

- Similarity computation methods appropriate for each data type

- Neural network framework for feature integration

Procedure:

- Feature Preparation:

- For each biological entity, compute relevant similarity matrices

- Apply dimensionality reduction (PCA or autoencoders) to standardize feature dimensions

- Handle missing data through imputation or similarity-based approaches

Feature Combination:

- Generate pairwise feature combinations between entity A and entity B

- For each feature pair, create input representations capturing their interactions

Model Architecture Setup:

- Implement lightweight neural networks for each feature pair

- Design the PSO-based optimization to learn optimal feature contributions

- Define the fusion mechanism to combine feature pair predictions

PSO-Neural Network Hybrid Optimization:

- Initialize particle positions representing feature weights

- For each particle, train the neural network architecture with the weighted features

- Evaluate model performance using cross-validation

- Update particles based on validation performance

- Iterate until optimal feature weights are identified

Prediction and Interpretation:

- Apply the trained model to new instances

- Analyze feature contributions to identify key biological factors

- Validate predictions against external biological knowledge

Troubleshooting:

- For overfitting, implement regularization in neural network components

- For computational bottlenecks, employ parallel processing for feature pairs

- For imbalanced data, incorporate weighted loss functions or sampling strategies

Visualization of PSO Workflows in Biological Contexts

Biochemical Parameter Estimation with RDPSO

PSO-FeatureFusion for Biological Data Integration

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for PSO in Biological Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function in PSO Biological Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Frameworks | MATLAB, Python (PySwarms, DEAP), R | Implementation of PSO algorithms and variant customization |

| Biological Data Repositories | NCBI, UniProt, DrugBank, TCGA | Source of heterogeneous biological data for optimization problems |

| Modeling and Simulation | COPASI, SBML-compatible tools, custom ODE solvers | Simulation of biochemical systems for fitness evaluation |

| Performance Assessment | Statistical testing frameworks, Cross-validation utilities | Validation of PSO performance and biological significance |

| High-Performance Computing | GPU acceleration, Parallel computing frameworks | Handling computational complexity of biological optimization |

PSO variants offer powerful and flexible optimization capabilities for addressing the complex challenges inherent in biological systems research. From parameter estimation in dynamic biochemical models to integration of heterogeneous omics data, specialized PSO approaches demonstrate significant advantages over traditional optimization methods. The continued development of biologically-inspired PSO variants, such as those incorporating eavesdropping and altruistic behaviors, promises further enhancements in our ability to optimize complex biological systems. By following the detailed protocols and utilizing the appropriate variants outlined in this application note, researchers can effectively leverage PSO advancements to accelerate discovery in biochemistry, systems biology, and drug development.

Implementing PSO for Biochemical Model Calibration: A Step-by-Step Methodology

Mathematical modeling is a powerful paradigm for analyzing and designing complex biochemical networks, from metabolic pathways to cell signaling cascades [22]. The development of these models is typically an iterative process where parameters are estimated by minimizing the residual between experimental measurements and model simulations, framed as a non-linear optimization problem [22]. Biochemical models present unique challenges for parameter estimation, including non-linear dynamics, multiple local extrema, noisy experimental data, and computationally expensive function evaluations [22] [23]. The inherent multi-modality of these systems renders local optimization techniques such as pattern search, Nelder-Mead simplex methods, and Levenberg-Marquardt often incapable of reliably obtaining globally optimal solutions [22]. This application note defines the core components of formulating optimization problems for biochemical models, with specific focus on objective function selection and parameter boundary definition within the context of particle swarm optimization (PSO) frameworks.

Core Components of the Optimization Problem

Objective Functions in Biochemical Modeling

The objective function quantifies the discrepancy between experimental data and model predictions, serving as the primary metric for evaluating parameter sets. In biochemical contexts, this typically involves comparing time-course experimental data with corresponding model simulations [23]. For a model with parameters θ, the general form minimizes the residual error: J(θ) = Σ[yexp(ti) - ymodel(ti, θ)]², where yexp and ymodel represent experimental and simulated values, respectively [23].

The complex dynamics of large biological systems and noisy, often incomplete experimental data sets pose a unique estimation challenge [22]. Objective functions for these problems are often non-convex with multiple local minima, necessitating global optimization strategies [22] [23]. For case studies involving complex pathways such as PI(4,5)P2 synthesis, objective functions typically incorporate multiple measured species (e.g., PI(4)P, PI(4,5)P2, and IP3 concentrations) to sufficiently constrain parameter space [24].

Table 1: Common Objective Function Formulations in Biochemical Optimization

| Function Type | Mathematical Form | Application Context | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of Squared Errors | J(θ) = Σ[yexp(ti) - ymodel(ti, θ)]² | Time-course data fitting [23] | Simple, widely applicable |

| Weighted Least Squares | J(θ) = Σwi[yexp(ti) - ymodel(t_i, θ)]² | Data with varying precision [23] | Accounts for measurement quality |

| Maximum Likelihood | J(θ) = -log L(θ⎪y_exp) | Problems with known error distributions | Statistical rigor |

| Multi-Objective | J(θ) = [J1(θ), J2(θ), ..., J_k(θ)] | Multiple, competing objectives [25] | Balances trade-offs |

Establishing Parameter Boundaries

Defining appropriate parameter boundaries is crucial for efficient optimization, particularly for population-based meta-heuristics like PSO. Proper parameter bounds help constrain the search space to biologically plausible regions while maintaining algorithm efficiency [23]. Parameter boundaries should be informed by:

- Prior biochemical knowledge (e.g., enzyme kinetics, known physiological ranges)

- Physical constraints (e.g., positive concentrations, irreversible reactions)

- Numerical stability of the integration methods

- Preliminary local searches to identify promising regions [23]

Overly restrictive bounds may exclude optimal solutions, while excessively wide bounds can dramatically reduce optimization efficiency. For large-scale models with 95+ parameters, as encountered in biogeochemical modeling, global sensitivity analysis can identify parameters with the strongest influence to inform bound selection [25].

Table 2: Parameter Boundary Considerations for Biochemical Models

| Boundary Type | Typical Range | Rationale | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetic Constants (kcat, Km) | 10-3 to 103 (physiological ranges) | Experimentally observable values [22] | Log-transformed search space |

| Initial Conditions | 0 to 10 × expected physiological concentrations | Non-negative, biologically plausible | Linear bounds with penalty functions |

| Hill Coefficients | 0.5 to 4-5 (cooperativity) | Empirical observations | Narrow bounds for specific mechanisms |

Particle Swarm Optimization Frameworks

Standard PSO Algorithm

Particle Swarm Optimization is a population-based stochastic optimization technique inspired by social behavior patterns such as bird flocking [26]. In the context of biochemical parameter estimation, each particle represents a potential parameter vector θ, and the swarm explores parameter space through iterative position and velocity updates [26].

The continuous PSO algorithm updates particle positions using:

- vi(t+1) = w·vi(t) + c1·r1·(pi - xi(t)) + c2·r2·(pg - xi(t))

- xi(t+1) = xi(t) + vi(t+1)

where w is inertia weight, c1 and c2 are acceleration coefficients, r1 and r2 are random values, pi is the particle's best position, and pg is the swarm's best position [26].

Advanced PSO Variants for Biochemical Applications

Several enhanced PSO variants have been developed specifically to address challenges in biochemical parameter estimation:

Dynamic Optimization with Particle Swarms (DOPS): A novel hybrid meta-heuristic that combines multi-swarm PSO with dynamically dimensioned search (DDS) [22] [27]. DOPS uses multiple sub-swarms where updates are influenced by both the best particle in the sub-swarm and the current globally best particle, with an adaptive switching criterion to transition to DDS when convergence stalls [22].

Random Drift PSO (RDPSO): Inspired by the free electron model in metal conductors, RDPSO modifies the velocity update equation to enhance global search capability, improving performance on high-dimensional, multimodal problems [23].

DYN-PSO: Designed for dynamic optimization of biochemical processes, this variant enables direct calls to simulation tools and has been applied to optimize inducer and substrate feed profiles in fed-batch bioreactors [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for PSO in Biochemical Optimization

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| DOPS Software | Hybrid multi-swarm PSO with DDS [22] | Parameter estimation for human coagulation cascade model |

| cupSODA | GPU-powered deterministic simulator [28] | Parallel fitness evaluations for large biochemical networks |

| BGC-Argo Data | Multi-variable experimental constraints [25] | Parameter optimization for marine biogeochemical models (95 parameters) |

| BALiBASE | Reference protein alignments for validation [26] | Testing multiple sequence alignment algorithms |

| Biochemical Benchmark Sets | Standardized problem sets for method validation [22] | Performance comparison across optimization algorithms |

Experimental Protocol: Parameter Estimation Using DOPS

Problem Formulation

This protocol outlines parameter estimation for a biochemical model using the Dynamic Optimization with Particle Swarms (DOPS) framework, applicable to both metabolic networks and signaling pathways [22] [24].

Materials and Software Requirements:

- DOPS software (available under MIT license at http://www.varnerlab.org) [22]

- Biochemical model encoded as a function that simulates system dynamics

- Experimental dataset for calibration (e.g., time-course metabolite measurements)

- Computational environment capable of handling function evaluations

Step 1: Define the Objective Function 1.1 Encode the mathematical model of the biochemical system as a function that takes parameter vector θ and returns simulated trajectories. 1.2 Formulate the objective function as the sum of squared errors between experimental data and corresponding simulation outputs [22] [23]. 1.3 For multi-output systems, implement appropriate weighting schemes to balance contributions from different measured species.

Step 2: Establish Parameter Boundaries 2.1 Conduct literature review to establish biologically plausible ranges for each parameter. 2.2 Set lower and upper bounds (θL, θU) for all parameters, typically using logarithmic scaling for kinetic constants. 2.3 Validate that bounds permit physiologically realistic simulation outcomes.

Step 3: Configure DOPS Algorithm 3.1 Initialize algorithm parameters: - Number of particles: 40-100 (problem-dependent) - Maximum function evaluations (N): 4000 (adjust based on computational budget) [22] - Adaptive switching threshold: 10-20% of N without improvement [22] - Sub-swarm size: 5-20 particles [22]

Step 4: Execute Optimization 4.1 Initialize particle positions randomly within parameter bounds. 4.2 Run multi-swarm PSO phase until switching criterion met. 4.3 Automatically switch to DDS phase for greedy refinement. 4.4 Return best parameter vector and corresponding objective value.

Step 5: Validation and Analysis 5.1 Perform identifiability analysis on optimal parameter set. 5.2 Validate against unused experimental data (if available). 5.3 Perform local sensitivity analysis around optimum.

Case Study: PI(4,5)P2 Synthesis Pathway

A recent application of these principles optimized five kinetic parameters governing PI(4,5)P2 synthesis and degradation using experimental time-course data for PI(4)P, PI(4,5)P2, and IP3 [24]. The resulting model achieved strong correlation with experimental trends and reproduced dynamic behaviors relevant to cellular signaling, demonstrating the effectiveness of this approach for precision medicine applications [24].

Performance Analysis and Validation

Benchmark Testing

Comprehensive performance evaluation is essential for validating any optimization framework. DOPS was tested using classic optimization test functions (Ackley, Rastrigin), biochemical benchmark problems, and real-world biochemical models [22]. Performance was compared against common meta-heuristics including differential evolution (DE), simulated annealing (SA), and dynamically dimensioned search (DDS) across T = 25 trials with N = 4000 function evaluations per trial [22].

Table 4: Performance Comparison Across Optimization Algorithms

| Algorithm | 10D Ackley | 10D Rastrigin | 300D Rastrigin | CHO Metabolic | S. cerevisiae |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOPS | Best performance [22] | Best performance [22] | Only approach finding near-optimum [22] | Optimal solutions | Optimal solutions |

| DDS | Good performance | Good performance | Suboptimal | Suboptimal | Suboptimal |

| DE | Good performance | Good performance | Suboptimal | Suboptimal | Suboptimal |

| SA | Suboptimal | Suboptimal | Poor performance | Suboptimal | Suboptimal |

| Standard PSO | Suboptimal | Suboptimal | Poor performance | Suboptimal | Suboptimal |

Convergence Behavior

The hybrid structure of DOPS demonstrates distinct convergence phases. The initial multi-swarm PSO phase rapidly explores the parameter space, while the DDS phase provides refined local search [22]. This combination addresses the tendency of standard PSO to become trapped in local minima while maintaining efficiency [22] [23]. For the 300-dimensional Rastrigin function, DOPS was the only approach that found near-optimal solutions within the function evaluation budget, highlighting its scalability to high-dimensional problems common in systems biology [22].

Proper formulation of the optimization problem through careful definition of objective functions and parameter boundaries is foundational to successful parameter estimation in biochemical models. Particle swarm optimization variants, particularly hybrid approaches like DOPS that combine multi-swarm PSO with DDS, demonstrate superior performance on challenging biochemical optimization problems with multi-modal, high-dimensional parameter spaces. The protocols outlined provide researchers with practical guidance for implementing these methods, while case studies across diverse biochemical systems confirm their applicability to real-world modeling challenges. As biochemical models continue to increase in complexity, further development of efficient global optimization strategies will remain essential for advancing systems biology and precision medicine applications.

Integrating PSO with Modeling Frameworks like FABM

This document presents application notes and protocols for integrating Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) with modular modeling frameworks, specifically the Framework for Aquatic Biogeochemical Models (FABM). This work is situated within a broader thesis investigating the application of metaheuristic optimization algorithms, particularly PSO, to parameter estimation and uncertainty quantification in complex, dynamic biochemical systems models [14]. The inherent challenges of biochemical model calibration—including high dimensionality, nonlinearity, multimodality, and parameter correlation—make global optimization techniques essential [14]. PSO, a swarm intelligence algorithm inspired by the social behavior of bird flocking, has emerged as a powerful tool for such problems due to its simplicity, efficiency, and robust global search capabilities [1] [15]. Meanwhile, frameworks like FABM provide a standardized, flexible environment for developing and coupling biogeochemical process models to hydrodynamic drivers [29] [30]. The integration of PSO's optimization prowess with FABM's modular modeling infrastructure creates a potent platform for advancing systems biology and drug discovery research, enabling the rigorous calibration of complex models against experimental data [31] [14].

Foundational Concepts: PSO and FABM Architecture

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO): Core Algorithm and Variants

PSO is a population-based stochastic optimization technique where potential solutions, called particles, traverse a multidimensional search space [1]. Each particle adjusts its trajectory based on its own best-known position (pbest) and the best-known position of the entire swarm (gbest). The standard velocity (V) and position (X) update equations for particle i in dimension d at iteration t are:

V_id(t+1) = ω * V_id(t) + c1 * r1 * (pbest_id - X_id(t)) + c2 * r2 * (gbest_d - X_id(t))

X_id(t+1) = X_id(t) + V_id(t+1)

where ω is the inertia weight, c1 and c2 are cognitive and social acceleration coefficients, and r1, r2 ~ U(0,1) [15].

For challenging biochemical inverse problems, variants of PSO are often employed. The Constriction Factor PSO (CF-PSO) introduces a coefficient χ to ensure convergence, modifying the velocity update as shown in studies analyzing convergence [15]. Random Drift PSO (RDPSO) incorporates a randomness component inspired by the thermal motion of electrons to enhance global exploration and avoid premature convergence, which has proven effective for biochemical systems identification [14]. Adaptive PSO (APSO) dynamically adjusts parameters like ω during the search to balance exploration and exploitation [1].

Table 1: Key PSO Variants for Biochemical Model Calibration

| Variant | Core Modification | Advantage for Biochemical Models | Typical Parameter Settings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard PSO (SPSO) | Basic velocity/position update. | Simplicity, ease of implementation. | ω=0.7298, c1=c2=1.49618 [15] |

| Constriction Factor PSO (CF-PSO) | Velocity multiplied by constriction factor χ. | Guaranteed convergence, controlled particle dynamics. | χ~0.729, c1+c2 > 4 [15] |

| Random Drift PSO (RDPSO) | Adds a random drift term to velocity. | Improved global search, avoids local optima in multimodal landscapes. | Depends on drift distribution (e.g., exponential) [14] |

| Adaptive PSO (APSO) | Inertia weight ω decreases linearly or based on fitness. | Better balance of exploration/exploitation across search phases. | ωstart=0.9, ωend=0.4 [1] |

FABM Framework Architecture

The Framework for Aquatic Biogeochemical Models (FABM) is an open-source, Fortran-based framework designed to simplify the coupling of biogeochemical models to physical hydrodynamic models [29] [30]. Its core design principle is separation of concerns: it provides standardized interfaces (Application Programming Interfaces - APIs) that allow biogeochemical model code to be written once and then connected to various host hydrodynamics models (e.g., GETM, GOTM, ROMS) without modification [29] [32]. This is achieved by having the host model provide the physical environment (temperature, salinity, light, diffusivity) at a given location and time, while the FABM-linked biogeochemical module returns the rates of change of its state variables (e.g., nutrient concentrations, phytoplankton biomass). This modularity makes FABM an ideal testbed for applying optimization algorithms like PSO, as the biological model can be treated as a "black-box" function whose parameters need to be estimated.

Diagram 1: FABM Modular Architecture (Max 760px)

Integration Strategy and System Design

Integrating PSO with FABM involves creating an optimization wrapper that repeatedly executes the FABM-coupled model with different parameter sets proposed by the PSO algorithm, comparing model output to observational data, and guiding the swarm toward an optimal parameter configuration.

System Workflow:

- Initialization: Define the parameter search space (lower/upper bounds) for the FABM model parameters to be optimized. Initialize the PSO swarm with random positions (parameter sets) and velocities within these bounds.

- Evaluation Loop: For each particle (parameter set) in each iteration: a. The parameter set is passed to the FABM model configuration. b. The coupled hydrodynamic-biogeochemical model (host + FABM) is run over the desired simulation period. c. Model outputs (e.g., time series of chlorophyll-a, nutrient concentrations) are extracted and compared to observational target data. d. A fitness (objective) function value is computed, typically the sum of weighted squared errors (SSE) or the negative log-likelihood.

- PSO Update: Based on the fitness values, each particle updates its pbest. The swarm identifies the gbest. The PSO algorithm then updates velocities and positions for the next iteration.

- Termination: The loop continues until a convergence criterion is met (e.g., minimal improvement in gbest fitness, maximum iterations).

Diagram 2: PSO-FABM Integration Workflow (Max 760px)

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Parameter Estimation for a Nutrient-Phytoplankton-Zooplankton-Detritus (NPZD) Model

This protocol details the steps to calibrate a generic NPZD model coupled via FABM using PSO.

1. Objective: Estimate kinetic parameters (e.g., maximum growth rate μ_max, grazing rate g_max, mortality rates, remineralization rate) that minimize the discrepancy between model output and observed time-series data for phytoplankton biomass (e.g., from chlorophyll sensors) and nutrient concentrations.

2. Pre-optimization Setup:

- FABM Model: Implement or select an NPZD model within the FABM framework. Ensure it compiles and runs correctly with your host hydrodynamic model.

- Observational Data: Prepare a dataset of target variables (e.g., nitrate, chlorophyll) with corresponding times and locations/spatial averages matching the model domain.

- Parameter Bounds: Define physiologically/chemically plausible lower and upper bounds for each parameter to be optimized.

- Fitness Function: Define the objective function. A common choice is the weighted Sum of Squared Errors (SSE):

Fitness = Σ_i w_i * Σ_t (Y_obs(i,t) - Y_model(i,t))^2whereiindexes state variables,tindexes time points,Yare the values, andw_iare weights to balance different variable scales (e.g., μM for nutrients vs. mg/m³ for chlorophyll).

3. PSO Configuration:

- Algorithm Variant: Select CF-PSO or RDPSO for robust convergence [15] [14].

- Swarm Size: Use 20-50 particles. Larger swarms aid global search but increase computational cost.

- Parameters: Set constriction factor χ=0.729, c1=c2=2.05 for CF-PSO [15]. For RDPSO, set parameters as described in the relevant literature [14].

- Stopping Criteria: Maximum iterations (e.g., 200-500) OR fitness improvement <

1e-6over 50 iterations.

4. Execution:

- Automate the loop described in Section 3 using a scripting language (Python, MATLAB). The script should: a. Generate model configuration files with the proposed parameters for each particle. b. Launch the host+FABM model executable. c. Parse model output and compute fitness. d. Implement the PSO update rules.

- Run the optimization on a high-performance computing cluster due to the computational intensity.

5. Validation:

- Run the calibrated model with the optimal parameters on a validation period (data not used in calibration).

- Perform sensitivity analysis on the optimal parameters.

Protocol B: Mechanism Discrimination in Drug-Target Kinetics (Inspired by Biochemical PSO Applications)

Although FABM is ecosystem-focused, the PSO integration logic is directly transferable to biochemical kinetic models relevant to drug discovery, aligning with the thesis context [31] [14].