Optimization in Computational Systems Biology: A Beginner's Guide to Methods, Applications, and Best Practices

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive introduction to optimization methods in computational systems biology.

Optimization in Computational Systems Biology: A Beginner's Guide to Methods, Applications, and Best Practices

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive introduction to optimization methods in computational systems biology. It covers foundational concepts, from defining optimization problems to understanding their critical role in analyzing biological systems. The article explores key algorithmic strategies—including deterministic, stochastic, and heuristic methods—and their practical applications in model tuning and biomarker identification. It further addresses common computational challenges and validation strategies to ensure model reliability, offering a practical roadmap for leveraging optimization to accelerate drug discovery and advance personalized medicine.

What is Optimization in Systems Biology? Core Concepts and Why It Matters

Optimization, at its essence, is the process of making a system or design as effective or functional as possible by systematically selecting the best element from a set of available alternatives with regard to specific criteria [1]. In mathematical terms, an optimization problem involves maximizing or minimizing a real function (the objective function) by choosing input values from a defined allowed set [1]. This framework is ubiquitous, forming the backbone of decision-making in fields from engineering and economics to the life sciences [2] [1].

In biology, the principle of optimization takes on a profound significance. Biological systems are shaped by the relentless pressures of evolution and natural selection in environments with finite resources [3]. The paradox of biology lies in the fact that while living things are energetically expensive to maintain in a state of high organization, they display a striking parsimony in their operations [3]. This tendency toward efficiency arises from a fundamental imperative: the biological unit (whether a gene, cell, organism, or colony) that achieves better efficiency than its neighbors gains a reproductive advantage [3]. Consequently, the benefit-to-cost ratio of almost every biological function is subject to optimization, leading to predictable structures and behaviors [3] [4]. This guide frames these concepts within the context of computational systems biology, where mathematical optimization is leveraged to understand, model, and engineer living systems.

Mathematical Foundations of Optimization

The formal structure of an optimization problem consists of three key elements: decision variables (parameters that can be varied), an objective function (the performance index to be maximized or minimized), and constraints (requirements that must be met) [2]. Problems are classified based on the nature of the variables and the form of the functions. Continuous optimization involves real-valued variables, while discrete (or combinatorial) optimization involves integers, permutations, or graphs [1]. A critical distinction is between convex and non-convex problems. Convex problems have a single, global optimum and are generally easier to solve reliably [2] [1]. Non-convex problems may have multiple local optima, necessitating global optimization techniques to find the best overall solution [2] [5].

A classic illustrative example is the "diet problem," a linear programming (LP) task to find the cheapest combination of foods that meets all nutritional requirements [2]. Here, the cost is the linear objective function, the amounts of food are continuous decision variables, and the nutritional needs form linear constraints.

Quantitative Comparison of Optimization Problem Types

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Optimization Problem Classes in Computational Biology

| Problem Class | Variable Type | Objective & Constraints | Solution Landscape | Typical Applications in Systems Biology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Programming (LP) [2] [1] | Continuous | Linear | Convex; single global optimum | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), metabolic network optimization [2]. |

| Nonlinear Programming (NLP) [1] | Continuous | Nonlinear | Often non-convex; potential for multiple local optima | Parameter estimation in kinetic models, optimal experimental design [2] [5]. |

| Integer/Combinatorial Optimization [1] | Discrete | Linear or Nonlinear | Non-convex; combinatorial explosion | Gene knockout strategy prediction, network inference [2]. |

| Global Optimization [5] | Continuous/Discrete | Generally Nonlinear | Explicitly searches for global optimum among many local optima | Parameter estimation in multimodal problems, robust model fitting [5]. |

Optimization as a Biological Principle

Biological optimization is not an abstract concept but a measurable reality driven by evolutionary competition. It manifests across all hierarchical levels, from molecular networks to whole organisms and ecosystems [3]. The driving force is the "zero-sum game" of survival and reproduction: saving operational energy allows an organism to redirect resources toward reproductive success, providing a competitive edge [3].

This leads to the prevalence of biological optima. An optimum can be narrow (highly selective, with high costs for deviation, like the precisely tuned wing strength of a hummingbird) or broad (allowing flexibility with minimal cost penalty, as seen in many genetic variations) [3]. Broad optima are often a consequence of biological properties like environmental sensing, adaptive response, and the existence of functionally equivalent alternate forms [3].

A powerful demonstration is found in developmental biology. Research on fruit fly (Drosophila) embryogenesis shows that the information flow governing segmentation is near the theoretical optimum [4]. Maternal inputs activate a network of gap genes, which in turn regulate pair-rule genes to create the body plan. Cells achieve remarkable positional accuracy (within 1%) by optimally reading the concentrations of multiple gap proteins [4]. Furthermore, the system is configured to minimize noise, using inputs in inverse proportion to their noise levels—a strategy analogous to clear communication [4]. This observed optimality presents a profound question about its origin, sitting at the intersection of evolutionary and design-based explanations [4].

Optimization in Computational Systems Biology: Methodologies and Protocols

Computational systems biology employs optimization as a core tool for both understanding and engineering biological systems. Key applications include model building, reverse engineering, and metabolic engineering.

Key Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) for Metabolic Phenotype Prediction

- Objective: To predict the optimal metabolic flux distribution in a genome-scale network under steady-state conditions to maximize biomass or product yield.

- Methodology:

- Network Reconstruction: Assemble a stoichiometric matrix (S) representing all known metabolic reactions in the organism.

- Constraint Definition: Apply physico-chemical constraints (steady-state: S·v = 0) and capacity bounds (α ≤ v ≤ β) on reaction fluxes (v).

- Objective Function: Define a biologically relevant linear objective to maximize (e.g., biomass reaction flux).

- Linear Programming Solution: Solve the LP problem: max (c^T·v) subject to S·v = 0 and α ≤ v ≤ β, where c is a vector defining the objective.

- Validation & Interpretation: Compare predicted growth rates or secretion profiles with experimental data [2].

- Relevant Search Results: This methodology is the engine behind metabolic flux analysis and is used for in silico prediction of E. coli and yeast capabilities [2].

Protocol 2: Parameter Estimation for Dynamical Model Tuning

- Objective: To find the unknown parameters (e.g., rate constants) of a mechanistic model (e.g., ODEs) that best fit experimental time-series data.

- Methodology:

- Model Formulation: Define the model structure as a set of differential equations: dx/dt = f(x, θ, t), where x are state variables and θ are unknown parameters.

- Cost Function Definition: Typically, a least-squares objective is used: min Σ [ymodel(ti, θ) - ydata(ti)]^2, where y is the measured output.

- Global Optimization: Due to the problem's non-convexity, apply a global optimization algorithm (e.g., multi-start methods, evolutionary algorithms) to avoid local minima.

- Uncertainty Analysis: Use techniques like profile likelihood or Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) to assess parameter identifiability and confidence intervals [5].

- Relevant Search Results: Parameter estimation is formulated as a nonlinear programming problem, often requiring global optimization methods [2] [5].

Protocol 3: Optimal Experimental Design (OED)

- Objective: To plan experiments that maximize the information gained (e.g., about model parameters) while minimizing cost or time.

- Methodology:

- Define Information Metric: Select a criterion from optimal design theory (e.g., D-optimality to minimize parameter covariance).

- Formulate Optimization Problem: Decision variables are experimental controls (e.g., measurement time points, input doses). The objective function is the chosen information metric, evaluated via the expected model output.

- Solve NLP Problem: Use optimization algorithms to find the control variables that maximize the information metric [2].

- Relevant Search Results: OED is crucial for making the best use of expensive and time-consuming biological experiments [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Tools for Optimization-Driven Systems Biology Research

| Tool / Reagent Category | Specific Example / Function | Role in Optimization Research |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Solvers & Libraries | CPLEX, Gurobi (LP/QP), IPOPT (NLP), MEIGO (Global Opt.) [2] [5] | Provide robust algorithms to numerically solve formulated optimization problems. |

| Modeling & Simulation Platforms | COPASI, PySB, Tellurium, SBML-compatible tools | Enable the creation, simulation, and parameterization of mechanistic biological models for use in optimization. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models | Recon (human), iJO1366 (E. coli), Yeast8 (S. cerevisiae) [2] | Serve as the foundational constraint-based framework for FBA and metabolic engineering optimizations. |

| Global Optimization Algorithms | Multi-start NLP, Genetic Algorithms (sGA), Markov Chain Monte Carlo (rw-MCMC) [5] | Essential for solving non-convex problems like parameter estimation and structure identification. |

| Optimal Experimental Design Software | PESTO, Data2Dynamics, STRIKE-GOLDD | Implement OED protocols to inform efficient data collection for model discrimination and calibration. |

| Synthetic Biology Design Tools | OptCircuit framework, Cello, genetic circuit design automation [2] | Use optimization in silico to design genetic components and circuits with desired functions before construction. |

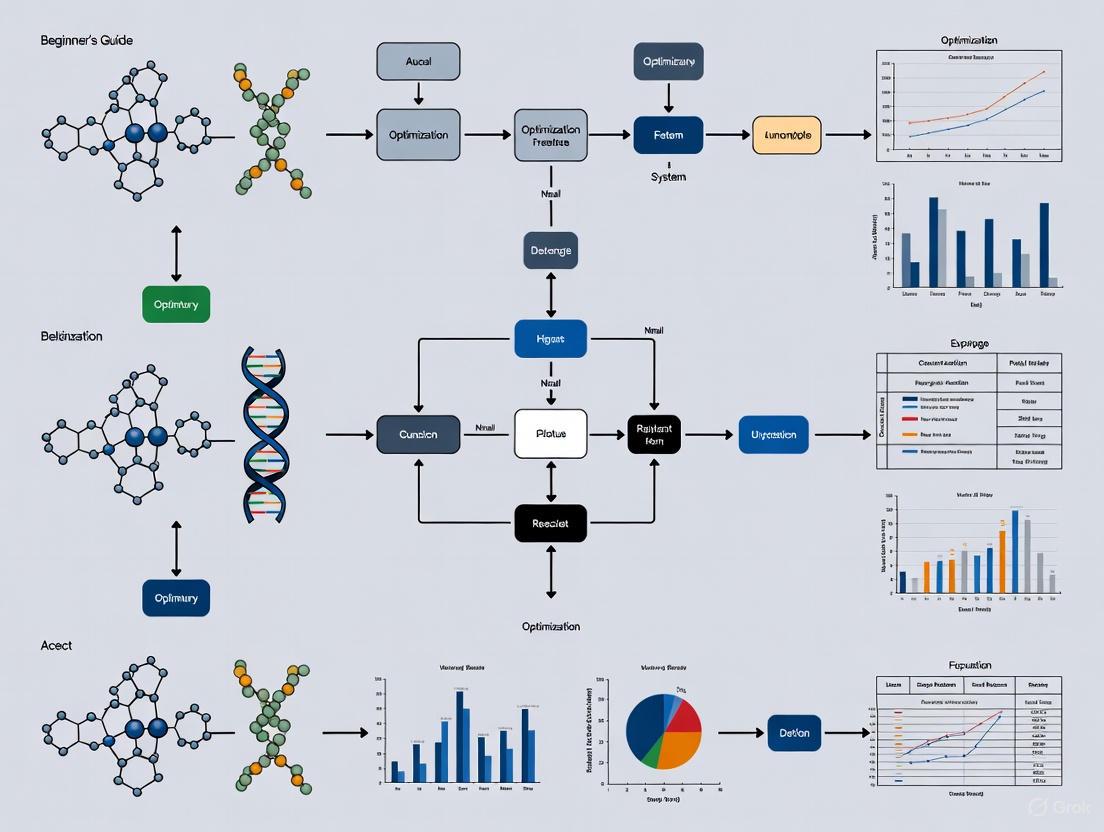

Visualization of Core Concepts

Title: Components of a Mathematical Optimization Problem

Title: Optimization as a Unifying Principle Across Biological Scales

Title: The Iterative Cycle of Modeling and Optimization in Systems Biology

Mathematical optimization is a systematic approach for determining the best decision from a set of feasible alternatives, subject to specific limitations [6] [7]. In the field of computational systems biology, which aims to understand and engineer complex biological systems, optimization methods have become indispensable [2] [8]. The rationale for using optimization in this domain is rooted in the inherent optimality observed in biological systems—structures and networks shaped by evolution often represent compromises between conflicting demands such as efficiency, robustness, and adaptability [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, framing biological questions as optimization problems provides a powerful, quantitative framework for hypothesis generation, model building, and rational design [2] [9]. This guide serves as a beginner's introduction to the three foundational pillars of any optimization problem: decision variables, objective functions, and constraints, contextualized for applications in systems biology.

Core Elements of an Optimization Problem

An optimization model is formally characterized by four main features: decision variables, parameters, an objective function, and constraints [9]. Parameters are fixed input data, while the other three elements define the structure of the problem itself.

Decision Variables

Decision variables represent the unknown quantities that the optimizer can modify to achieve a desired outcome [6] [10]. They are the levers of the system under control. In a general model, decision variables are denoted as a vector x = (x₁, x₂, ..., xₙ) [11]. An assignment of values to all variables is called a solution [10].

In Computational Systems Biology: Decision variables can represent a wide array of biological quantities. They may be continuous (e.g., metabolite concentrations, enzyme expression levels, or drug dosages) or discrete (e.g., presence/absence of a gene knockout, integer number of reaction steps) [2]. For instance, in the classical "diet problem"—one of the first modern optimization problems—the decision variables are the amounts of each type of food to be purchased [2]. In metabolic engineering, decision variables could be the fluxes through a network of biochemical reactions [2].

Objective Function

The objective function, often denoted as f(x), is a mathematical expression that quantifies the performance or outcome to be optimized (maximized or minimized) [6] [12]. It provides the criterion for evaluating the quality of any given solution defined by the decision variables [2]. In machine learning contexts, it is often referred to as a loss or cost function [12] [13].

In Computational Systems Biology: The choice of objective function is critical and reflects a hypothesis about what the biological system is optimizing. Common objectives include:

- Maximizing the growth rate of a cell in metabolic flux balance analysis [2].

- Minimizing the difference between model predictions and experimental data during parameter estimation [2].

- Maximizing the production yield of a target metabolite in metabolic engineering [2].

- Minimizing the cost of a drug regimen while achieving therapeutic efficacy [9].

Constraints

Constraints are equations or inequalities that define the limitations or requirements imposed on the decision variables [6] [14]. They dictate the allowable choices and define the feasible region—the set of all solutions that satisfy all constraints [10] [7]. A solution is termed feasible if it meets all constraints [7]. Constraints can be equality (e.g., representing mass-balance in a steady-state metabolic network) or inequality (e.g., representing resource limitations or capacity bounds) [14].

In Computational Systems Biology: Constraints encode known physico-chemical and biological laws, as well as experimental observations.

- Equality Constraints: Often used to represent steady-state mass balances in metabolic networks (input = output) [2].

- Inequality Constraints: Can represent enzyme capacity limits (maximum reaction rate, V_max), nutrient availability, or regulatory boundaries [2].

- Bounds: Simple lower and upper limits on variables, such as non-negativity constraints for concentrations [10] [11].

Table 1: Summary of Core Optimization Elements with Biological Examples

| Element | Definition | Role in Problem | Example in Systems Biology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Variables | Unknown quantities the optimizer controls. | Represent the choices to be made. | Flux through a metabolic reaction, level of gene expression, dosage of a drug. |

| Objective Function | Function to be maximized or minimized. | Quantifies the "goodness" of a solution. | Maximize biomass production, minimize model-data error, minimize treatment cost. |

| Constraints | Equations/inequalities limiting variable values. | Define the feasible and realistic solution space. | Mass conservation (equality), reaction capacity limits (inequality), non-negative concentrations (bound). |

Formulation and Problem Types in Biological Research

A general optimization problem can be formulated as [9]: Maximize (or Minimize) f(x₁, …, xₙ; α₁, …, αₖ) Subject to gᵢ(x₁, …, xₙ; α₁, …, αₖ) ≥ 0, i = 1, …, m

Problems are classified based on the nature of the variables and the form of the objective and constraint functions, which dictates the solving strategy.

Table 2: Classification of Optimization Problems Relevant to Systems Biology

| Problem Type | Decision Variables | Objective & Constraints | Key Characteristics & Biological Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Programming (LP) | Continuous | All linear functions. | Efficient, globally optimal solution guaranteed. Used in Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) of metabolism [2] [11]. |

| Nonlinear Programming (NLP) | Continuous | At least one nonlinear function. | Can be multimodal (multiple local optima). Used in dynamic model parameter estimation [2] [7]. |

| (Mixed-)Integer Programming (MIP/MILP) | Continuous and discrete (integer/binary). | Linear or nonlinear. | Computationally challenging. Used to model gene knockout strategies (binary on/off) [2] [9]. |

| Multi-Objective Optimization | Any type. | Multiple conflicting objective functions. | Seeks a set of Pareto-optimal trade-off solutions. Balances, e.g., drug efficacy vs. toxicity [7]. |

Visualizing the Core Relationship: The following diagram illustrates the fundamental relationship between the three key elements.

Diagram 1: Interplay of Core Elements in an Optimization Problem

Experimental and Computational Methodologies in Systems Biology

The application of optimization in systems biology follows rigorous workflows. Below is a detailed protocol for a common task: Parameter Estimation in Dynamic Biochemical Models, which is typically formulated as a nonlinear programming (NLP) or global optimization problem [2].

Protocol: Parameter Estimation via Optimization

Problem Formulation:

- Decision Variables: Unknown kinetic parameters of the model (e.g., Michaelis constants (Kₘ), catalytic rates (k_cat)).

- Objective Function: Minimize the sum of squared errors (SSE) between model simulations (y_model(t, p)) and experimental time-course data (y_data(t)) for selected species.

- Minimize SSE(p) = Σt (ymodel(t, p) – y_data(t))²

- Constraints: Include bounds on parameters based on physiological knowledge (e.g., 0 < p < p_max), and the system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) describing the biochemical network, which must be satisfied at all times.

Algorithm Selection:

Implementation & Solving:

- Use modeling software (e.g., Python with SciPy, COPASI, MATLAB) to encode the ODE model, objective, and constraints [9].

- Interface with a suitable solver engine (e.g., IPOPT for NLP, Gurobi/CPLEX for LP/MILP, or built-in global optimizers) [9].

- Execute the optimization routine, monitoring convergence.

Model Validation & Analysis:

- Assess goodness-of-fit (e.g., R², residual analysis).

- Perform sensitivity or identifiability analysis on the estimated parameters.

- Validate the calibrated model against a separate validation dataset.

Workflow for Optimization in Systems Biology: The general process of applying optimization in a research context is summarized below.

Diagram 2: Systems Biology Optimization Research Workflow

Successful implementation of optimization in computational systems biology relies on a suite of software tools and data resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions (Software & Data)

| Item | Category | Function in Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Python with SciPy/CVXPY | Modeling Language & Library | Provides a flexible environment for problem formulation, data handling, and accessing various optimization solvers [9]. |

| R with optimx/nloptr | Modeling Language & Library | Statistical computing environment with packages for different optimization algorithms, useful for parameter fitting. |

| Gurobi / CPLEX | Solver Engine | High-performance commercial solvers for LP, QP, and MIP problems, widely used in metabolic network analysis [9]. |

| COPASI / SBML | Modeling & Simulation Tool | Specialized software for simulating and optimizing biochemical network models; uses SBML as a standard model exchange format. |

| Global Optimization Solvers(e.g., SCIP, BARON) | Solver Engine | Designed to find global solutions for non-convex NLP and MINLP problems, crucial for reliable parameter estimation [2]. |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models(e.g., for E. coli, S. cerevisiae) | Data / Model Repository | Large-scale constraint-based models that serve as the foundation for flux optimization studies in metabolic engineering [2]. |

| Bioinformatics Databases(e.g., KEGG, BioModels) | Data Repository | Provide curated pathway information and kinetic models necessary for building realistic constraints and objective functions. |

Mastering the formulation of decision variables, objective functions, and constraints is the critical first step in leveraging mathematical optimization within computational systems biology [6]. This framework transforms qualitative biological questions into quantifiable, computable problems, enabling tasks from network inference and model calibration to the rational design of synthetic circuits and therapeutic strategies [2] [9]. While the field faces challenges such as problem scale, multimodality, and inherent biological stochasticity [2] [7], a clear understanding of these core elements empowers researchers to select appropriate problem classes and solution strategies. As optimization software and computational power advance, these methods will increasingly underpin the model-driven, hypothesis-generating engine of modern biological and biomedical discovery.

In modern biological research, optimization has transitioned from a useful computational tool to a fundamental methodology for tackling the overwhelming complexity and scale of contemporary datasets. The core challenge facing researchers today lies in navigating high-dimensional biological systems where the number of variables—from genes and proteins to metabolic fluxes—can reach astronomical numbers, while experimental resources remain severely constrained [2] [15]. Optimization provides the mathematical framework to make biological systems as effective or functional as possible by finding the best compromise among several conflicting demands subject to predefined requirements [2].

The necessity for optimization in biology stems from several intersecting factors: the exponential growth in data generation from high-throughput technologies, the inherent complexity of biological networks with their nonlinear interactions and feedback loops, and the practical constraints of time and resources in experimental settings [16] [17]. In essence, optimization methods serve as a crucial bridge between vast, multidimensional biological data and actionable biological insights, enabling researchers to extract meaningful patterns, build predictive models, and design effective intervention strategies [2] [18].

This technical guide explores the fundamental principles, key applications, and methodological approaches that make optimization indispensable for modern biology, with particular emphasis on handling complexity and high-dimensional data in computational systems biology research.

Mathematical Foundations of Biological Optimization

At its core, mathematical optimization in biology involves three key elements: decision variables (biological parameters that can be varied), an objective function (the performance index quantifying solution quality), and constraints (requirements that must be met, usually expressed as equalities or inequalities) [2]. These components can be adapted to numerous biological contexts, from tuning enzyme expression levels in metabolic pathways to selecting optimal feature subsets in high-dimensional omics data.

Biological optimization problems can be categorized based on their mathematical properties:

- Linear Programming (LP): Applied when both objective function and constraints are linear with respect to decision variables, commonly used in flux balance analysis of metabolic networks [2]

- Nonlinear Programming (NLP): Necessary when constraints or objective functions are nonlinear, representing much more difficult problems that frequently appear in biological systems due to their inherent nonlinearity [2]

- Convex vs. Nonconvex Optimization: Convex problems have unique solutions and can be solved efficiently, while nonconvex problems may have multiple local solutions (multimodality) requiring global optimization techniques [2]

- Integer/Combinatorial Optimization: Used when decision variables are discrete, such as in gene knockout strategies where variables represent presence or absence of specific genes [2]

A critical challenge in biological optimization is the curse of dimensionality, where the number of possible configurations grows exponentially with the number of variables, making exhaustive search strategies computationally intractable [16] [19]. This is particularly problematic in omics data analysis, where the number of features (p) can reach millions while sample sizes (n) remain relatively small [16].

Table 1: Classification of Optimization Problems in Computational Biology

| Problem Type | Key Characteristics | Biological Applications | Solution Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Programming (LP) | Linear objective and constraints | Metabolic flux balance analysis | Efficient for large-scale problems |

| Nonlinear Programming (NLP) | Nonlinear objective or constraints | Parameter estimation in pathway models | Multiple local solutions; requires global optimization |

| Integer/Combinatorial | Discrete decision variables | Gene knockout strategy identification | Computational time increases exponentially with problem size |

| Convex Optimization | Unique global solution | Certain model fitting problems | Highly desirable but not always possible to formulate |

| High-Dimensional Optimization | Number of variables >> samples | Feature selection in omics data | Curse of dimensionality; overfitting |

Key Applications in Computational Systems Biology

Metabolic Engineering and Synthetic Biology

Optimization methods have become the computational engine behind metabolic flux balance analysis, where optimal flux distributions are calculated using linear optimization to represent metabolic phenotypes under specific conditions [2]. This approach provides a systematic framework for metabolic engineering, enabling researchers to identify genetic modifications that optimize the production of target compounds.

In synthetic biology, optimization facilitates the rational redesign of biological systems. For instance, Bayesian optimization has been successfully applied to optimize complex metabolic pathways, such as the heterologous production of limonene and astaxanthin in engineered Escherichia coli [15]. These approaches can identify optimal expression levels for multiple enzymes in a pathway, dramatically reducing the experimental resources required compared to traditional one-factor-at-a-time approaches. The BioKernel framework demonstrated this capability by converging to optimal solutions using just 22% of the experimental points required by traditional grid search methods [15].

Drug Development and Pharmacokinetic Optimization

In pharmaceutical research, optimization plays a critical role in Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD), providing quantitative predictions and data-driven insights that accelerate hypothesis testing and reduce costly late-stage failures [18]. Optimization techniques are embedded throughout the drug development pipeline, from early target identification to post-market surveillance.

Key applications include:

- Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling: Mechanistic modeling that optimizes drug formulation and dosing regimens by simulating the interplay between physiology and drug properties [18]

- Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR): Computational modeling that optimizes the prediction of biological activity based on chemical structure [18]

- ADME Optimization: Critical for enhancing absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion properties of therapeutic compounds through in vitro and in vivo experimental optimization [20]

- Dose Optimization: Using exposure-response modeling and clinical trial simulation to identify optimal dosing strategies that maximize efficacy while minimizing toxicity [18]

Analysis of High-Dimensional Omics Data

The analysis of high-dimensional biomedical data represents one of the most prominent applications of optimization in modern biology. Feature selection algorithms are optimization techniques designed to identify the most relevant variables from datasets with thousands to millions of features [16] [19]. These methods are essential for reducing model complexity, decreasing training time, enhancing generalization capability, and avoiding the curse of dimensionality [19].

Hybrid optimization algorithms such as Two-phase Mutation Grey Wolf Optimization (TMGWO), Improved Salp Swarm Algorithm (ISSА), and Binary Black Particle Swarm Optimization (BBPSO) have demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in identifying significant features for classification tasks in biomedical datasets [19]. For example, the TMGWO approach combined with Support Vector Machines achieved 96% accuracy in breast cancer classification using only 4 features, outperforming recent Transformer-based methods like TabNet (94.7%) and FS-BERT (95.3%) while being more computationally efficient [19].

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Bayesian Optimization for Biological Systems

Bayesian optimization (BO) has emerged as a particularly powerful strategy for biological optimization problems characterized by expensive-to-evaluate objective functions, experimental noise, and high-dimensional design spaces [15]. The strength of BO lies in its ability to find global optima with minimal experimental iterations by building a probabilistic model of the objective function and using an acquisition function to guide the selection of the next most informative experiments.

The core components of Bayesian optimization include:

- Gaussian Process (GP): Serves as a probabilistic surrogate model that provides both predictions and uncertainty estimates for unexplored regions of parameter space [15]

- Acquisition Function: Balances exploration (sampling uncertain regions) and exploitation (sampling regions with high predicted values) to select the next experimental conditions [15]

- Iterative Experimental Design: Updates the probabilistic model with each new data point, creating a closed-loop optimization system [15]

Figure 1: Bayesian Optimization Workflow for Biological Experimental Campaigns

Advanced Optimization Frameworks

Recent advances have introduced even more powerful optimization frameworks specifically designed for complex biological systems:

Deep Active Optimization with Neural-Surrogate-Guided Tree Exploration (DANTE) represents a cutting-edge approach that combines deep neural networks with tree search methods to address high-dimensional, noisy optimization problems with limited data availability [21]. DANTE utilizes a deep neural surrogate model to approximate the complex response landscape and employs a novel tree exploration strategy guided by a data-driven upper confidence bound to balance exploration and exploitation [21].

Key innovations in DANTE include:

- Neural-Surrogate-Guided Tree Exploration (NTE): Uses deep neural networks as surrogate models to guide the search process in high-dimensional spaces [21]

- Conditional Selection: Prevents value deterioration by selectively expanding nodes that show promise [21]

- Local Backpropagation: Enables escape from local optima by updating visitation data only between root and selected leaf nodes [21]

This approach has demonstrated superior performance in problems with up to 2,000 dimensions, outperforming state-of-the-art methods by 10-20% while utilizing the same number of data points [21].

Experimental Protocol: Bayesian Optimization for Metabolic Pathway Tuning

For researchers implementing Bayesian optimization for metabolic engineering applications, the following protocol provides a detailed methodology:

Problem Formulation:

- Define the biological objective function (e.g., product titer, yield, productivity)

- Identify tunable parameters (e.g., inducer concentrations, promoter strengths)

- Establish parameter bounds based on biological constraints

Initial Experimental Design:

- Select 5-10 initial design points using Latin Hypercube Sampling to maximize space-filling properties

- For 4-parameter optimization, 8 initial points typically provide sufficient coverage [15]

Iterative Optimization Cycle:

- Conduct experiments at designated parameter combinations

- Measure objective function values with appropriate technical replicates (minimum n=3)

- Update Gaussian Process model with new data using a Matern kernel with gamma noise prior to handle biological variability [15]

- Optimize acquisition function (Expected Improvement recommended for balance of exploration/exploitation) to select next parameter combination [15]

- Continue for 15-20 iterations or until convergence criteria met (e.g., <5% improvement over 3 consecutive iterations)

Validation:

- Confirm optimal parameter combination with independent biological replicates (n≥3)

- Compare performance against traditional approaches (e.g., one-factor-at-a-time) to quantify improvement

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Optimization-Driven Biological Experiments

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Optimization Workflow | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Marionette E. coli Strains | Tunable expression system with orthogonal inducible transcription factors | Multi-dimensional optimization of metabolic pathways [15] |

| Inducer Compounds (e.g., Naringenin) | Precise control of gene expression levels | Fine-tuning enzyme expression in synthetic pathways [15] |

| Spectrophotometric Assays | High-throughput quantification of target compounds | Rapid evaluation of optimization objectives (e.g., astaxanthin production) [15] |

| MPRAsnakeflow Pipeline | Streamlined data processing for massively parallel reporter assays | Optimization of regulatory sequences [22] |

| Tidymodels Framework | Machine learning workflows for omics data analysis | Feature selection and model optimization in high-dimensional data [22] |

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The future of optimization in computational systems biology points toward increasingly integrated and automated workflows. The development of self-driving laboratories represents a particularly promising direction, where optimization algorithms directly control experimental systems in closed-loop fashion, dramatically accelerating the design-build-test-learn cycle [21] [17]. These systems will leverage advances in artificial intelligence and robotics to conduct experiments with minimal human intervention.

Several emerging trends will shape the future landscape of biological optimization:

Digital Twins: Highly realistic computational models of biological systems, from cellular processes to entire organs, will enable in silico optimization before physical experimentation [17]. These digital replicas will allow researchers to explore vast parameter spaces computationally, reserving wet-lab experiments for validation of the most promising candidates [17].

Multi-scale Optimization: Future methodologies must address optimization across biological scales, from molecular interactions to cellular behavior and population dynamics [17]. This will require novel computational approaches that can efficiently navigate hierarchical objective functions with constraints at multiple levels of biological organization.

Explainable AI in Optimization: As optimization algorithms become more complex, there is growing need for interpretability, particularly in biomedical applications where understanding biological mechanisms is as important as predictive accuracy [23] [22]. Methods for explaining why particular solutions are optimal will be crucial for building trust and generating biological insights.

Integration of Prior Knowledge: Future optimization frameworks will better incorporate existing biological knowledge through informative priors in Bayesian methods or constraint definitions in mathematical programming approaches [18] [17]. This will make optimization more efficient by reducing the search space to biologically plausible regions.

Despite these promising developments, significant challenges remain. Data quality and quantity continue to limit optimization effectiveness, particularly for problems with extreme dimensionality where sample sizes are insufficient [16]. Computational complexity presents another barrier, as many global optimization problems belong to the class of NP-hard problems where obtaining guaranteed global optima is impossible in reasonable time [2]. Finally, methodological accessibility must be addressed through user-friendly software tools and education to make advanced optimization techniques available to biological researchers without deep computational backgrounds [15] [22].

Optimization has become an indispensable component of modern biological research, providing the mathematical foundation for extracting meaningful insights from complex, high-dimensional data. From tuning metabolic pathways to selecting informative features in omics datasets, optimization methods enable researchers to navigate vast biological design spaces with unprecedented efficiency. As biological datasets continue to grow in size and complexity, and as we strive to engineer biological systems with increasing sophistication, the role of optimization will only become more central to biological discovery and engineering.

The continued development of biological optimization methodologies—particularly approaches that can handle noise, heterogeneity, and multiple scales—will be essential for addressing the most pressing challenges in biomedicine, synthetic biology, and biotechnology. By closing the loop between computational prediction and experimental validation, optimization provides a powerful framework for accelerating the pace of biological discovery and engineering, ultimately enabling more effective therapies, sustainable bioprocesses, and fundamental insights into the principles of life.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) into computational systems biology is fundamentally restructuring the drug discovery pipeline and enabling truly personalized medicine. This whitepaper details the practical implementation of these technologies, demonstrating their impact through specific quantitative metrics, including a reduction in discovery timelines from a decade to under a year and a rise in the projected AI-driven biotechnology market to USD 11.4 billion by 2030 [24] [25]. We provide an in-depth examination of the underlying computational methodologies, from multimodal AI frameworks to novel optimization algorithms like Adaptive Bacterial Foraging (ABF), and present validated experimental protocols that researchers can deploy to accelerate their work in precision oncology and therapeutic development [26] [24].

The foundational challenge in modern drug discovery and personalized medicine is the sheer complexity and high-dimensionality of biological data. Optimization in computational systems biology involves formulating biological questions—such as identifying a drug candidate or predicting a patient's treatment response—as problems that can be solved computationally. This moves research beyond traditional trial-and-error towards a predictive science.

This shift is powered by the convergence of three factors: the availability of large-scale molecular and clinical datasets (e.g., from biobanks), advancements in ML algorithms, and increases in computational power [27] [24]. The goal is to find the optimal parameters within a complex biological system—for instance, the set of genes that serve as the most predictive biomarkers or the molecular structure with the highest therapeutic efficacy and lowest toxicity. Framing this as an optimization problem allows researchers to efficiently navigate a vast search space that would be intractable using manual methods.

AI in Drug Discovery: From Concept to Candidate

Artificial intelligence is being systematically embedded across the entire drug development value chain, introducing unprecedented efficiencies.

Quantitative Impact of AI on the Drug Discovery Pipeline

The integration of AI is yielding measurable improvements in the speed, cost, and success rate of bringing new therapeutics to market, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of AI on Drug Discovery and Development

| Metric | Traditional Process | AI-Accelerated Process | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Discovery Timeline | 4-6 years | Weeks to 30 days [24] [28] | Industry Reports & Case Studies |

| Overall Development Cycle | 12+ years | 5-7 years [28] | Industry Analysis |

| R&D Cost Reduction | Baseline | 40-60% projected reduction [28] | Industry Analysis |

| Clinical Trial Enrollment | Manual screening (months) | AI-driven matching (hours), 3x faster [27] | Clinical Research Platforms |

| Global AI in Biotech Market | - | Projected to grow from $4.6B (2025) to $11.4B (2030) [25] | Market Research Report |

Key Applications and Methodologies

Accessing Novel Biological Targets: AI algorithms, particularly deep learning models, analyze vast genomic, proteomic, and transcriptomic datasets to identify and validate new drug targets. For example, BenevolentAI's Knowledge Graph integrates disparate biomedical data to uncover novel target-disease associations, which has proven instrumental in areas like neurodegenerative disease research [29] [24].

Generating Novel Compounds: Generative AI models, such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), can design de novo molecular structures with optimized properties for a specific target. Companies like Insilico Medicine and Atomwise utilize these technologies to create and screen billions of virtual compounds in silico, dramatically accelerating the hit-to-lead process [29] [24].

Predicting Clinical Success: ML models are trained on historical clinical trial data to forecast the Probability of Success (POS) for new candidates. These models analyze factors including target biology, chemical structure, and preclinical data to flag potential toxicity or efficacy issues early, enabling better resource allocation and risk management [24].

Table 2: Leading AI Companies in Drug Discovery and Their Specializations

| Company | Core Specialization | Key Technology/Platform | Therapeutic Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exscientia | AI-driven precision therapeutics | Automated drug design platform | Oncology, Immunology [29] |

| Recursion | Automated biological data generation | RECUR platform (cellular imaging + AI) | Fibrosis, Oncology, Rare Diseases [29] [25] |

| Schrödinger | Physics-based molecular modeling | Advanced computational chemistry platform | Oncology, Neurology [29] [25] |

| Atomwise | Structure-based drug discovery | AtomNet platform (Deep Learning) | Infectious Diseases, Cancer [29] |

| Relay Therapeutics | Protein motion and drug design | Dynamo platform | Precision Oncology [29] |

Workflow Diagram: AI-Driven Drug Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the iterative, AI-powered workflow from target identification to preclinical candidate selection.

Enabling Personalized Medicine through Computational Genomics

Personalized medicine aims to tailor therapeutic interventions to an individual's unique molecular profile. AI acts as the critical engine that translates raw genomic data into clinically actionable insights.

Genomic Profiling in Oncology

The use of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) in oncology has identified actionable mutations in a significant proportion of patients. One retrospective study of 1,436 patients with advanced cancer found that comprehensive genomic profiling identified actionable aberrations in 637 patients. Those who received matched, targeted therapy showed significantly improved outcomes: response rates of 11% vs. 5%, and longer overall survival (8.4 vs. 7.3 months) compared to those who did not [30].

AI-Powered Diagnostic and Screening Tools

- Ultra-Rapid Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS): A landmark study demonstrated a cloud-distributed nanopore sequencing workflow that delivers a genetic diagnosis in just 7 hours and 18 minutes, enabling timely diagnoses for critically ill infants and directly impacting clinical decisions such as medication selection and surgery [27].

- Newborn Screening: Population-scale initiatives like the GUARDIAN study are using WGS to screen for hundreds of treatable, early-onset genetic disorders that are absent from standard newborn screening panels. Data from the first 4,000 newborns showed that 3.7% screened positive for such conditions [27].

A Practical Guide to Optimization Algorithms and Experimental Protocols

For researchers, selecting and implementing the right optimization strategy is paramount. Below is a detailed protocol for a novel ML-based approach validated on colon cancer data, demonstrating the integration of optimization algorithms into a biomedical research pipeline.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: ABF-Optimized CatBoost for Multi-Targeted Therapy Prediction in Colon Cancer

This protocol outlines the methodology for developing a model that predicts drug response and identifies multi-targeted therapeutic strategies for Colon Cancer (CC) using high-dimensional molecular data [26].

4.1.1 Objective To integrate biomarker signatures from gene expression, mutation data, and protein interaction networks for accurate prediction of drug response and to enable a multi-targeted therapeutic approach for CC.

4.1.2 Materials and Data Sources (The Scientist's Toolkit) Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Item/Resource | Function/Description | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Data | Provides transcriptome-wide RNA quantification for biomarker discovery. | TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas), GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus) [26] |

| Mutation Data | Identifies somatic variants and driver mutations. | TCGA, COSMIC (Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer) [26] |

| Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks | Maps functional relationships between proteins to identify hub genes. | STRING database, BioGRID [26] |

| Adaptive Bacterial Foraging (ABF) Optimization | An optimization algorithm that refines search parameters to maximize predictive accuracy. | Custom implementation in Python/R [26] |

| CatBoost Algorithm | A high-performance gradient boosting algorithm for classification tasks. | Open-source library (e.g., catboost Python package) [26] |

| Validation Datasets | Independent datasets used to assess model generalizability and avoid overfitting. | GEO repository (e.g., GSE131418) [26] |

4.1.3 Step-by-Step Workflow

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Download CC datasets (e.g., RNA-seq, SNP arrays) from TCGA and GEO.

- Perform standard normalization (e.g., TPM for RNA-seq, RMA for microarray data) and batch effect correction.

- Annotate data with clinical outcomes (e.g., survival, drug response).

Feature Selection using ABF Optimization:

- Formulate feature selection as an optimization problem where the goal is to find the subset of genes that maximizes the predictive model's accuracy.

- Implement the ABF algorithm, which mimics the foraging behavior of E. coli bacteria. The algorithm uses techniques for chemotaxis, swarming, reproduction, and elimination-dispersal to efficiently explore the high-dimensional feature space.

- The ABF algorithm's objective function is designed to maximize a fitness score (e.g., F1-score) from a preliminary CatBoost model while minimizing the number of selected features.

Model Training with CatBoost:

- Train the CatBoost classifier using the features selected by the ABF algorithm.

- Utilize CatBoost's built-in handling of categorical data (e.g., mutation types) and its robustness to overfitting.

- Perform hyperparameter tuning via cross-validation.

Model Validation and Interpretation:

- Validate the final ABF-CatBoost model on held-out internal test sets and external public datasets (e.g., GSE131418) [26].

- Evaluate performance using accuracy, specificity, sensitivity, F1-score, and Area Under the Curve (AUC).

- Interpret the model to identify the top contributing biomarkers and their relationship to drug response.

4.1.4 Results and Performance In the referenced study, this ABF-CatBoost integration achieved an accuracy of 98.6%, with a sensitivity of 0.979 and specificity of 0.984 in classifying patients and predicting drug responses, outperforming traditional models like Support Vector Machines and Random Forests [26].

Optimization in Cellular Programming

Beyond data analysis, optimization principles are being applied to control biological systems themselves. Harvard researchers have developed a computational framework that treats the control of cellular organization (morphogenesis) as an optimization problem [31].

- Method: The framework uses automatic differentiation—a technique central to training neural networks—to efficiently compute how small changes in a cell's genetic network parameters will affect the final tissue-level structure.

- Application: The computer learns the "rules" of cellular growth, which can be inverted to answer the inverse problem: "How do we program individual cells to self-organize into a desired complex structure, like a specific organoid?" [31]. This represents the holy grail of computational bioengineering.

The Multimodal AI Framework and Future Outlook

The next frontier is multimodal AI, which integrates diverse data types—genomic, clinical, imaging, and real-world data—to deliver more holistic and accurate biomedical insights [24]. This approach is transformative because it provides a systems-level view of disease, moving beyond single-omics analyses.

Key future trends and challenges include:

- The Rise of Agentic and Generative AI: These technologies will further automate the design-test-learn cycle in drug discovery, generating novel therapeutic candidates and experimental hypotheses with minimal human intervention [24] [25].

- Federated Learning for Data Privacy: This allows AI models to be trained across multiple decentralized data sources (e.g., different hospitals) without sharing the raw data, thus preserving patient privacy and enabling collaboration [29] [24].

- Navigating the Evolving Regulatory Landscape: Regulatory agencies are showing a growing willingness to accept real-world data and innovative trial designs (e.g., synthetic control arms) as part of the evidence base for new therapies, particularly in rare diseases [27].

- Addressing Ethical and Technical Hurdles: Widespread adoption depends on overcoming challenges related to data quality, algorithmic bias, model interpretability ("black box" problem), and ensuring equitable access to these advanced technologies [24] [30].

Key Optimization Algorithms and Their Practical Applications in Biology

In the field of computational systems biology, researchers aim to gain a better understanding of biological phenomena by integrating biology with computational methods [5]. This interdisciplinary approach often requires the assistance of global optimization algorithms to adequately tune its tools, particularly for challenges such as model parameter estimation (model tuning) and biomarker identification [5]. The core problem is straightforward: biological systems are inherently complex, with multitude of interacting components, and the concomitant lack of information about essential dynamics makes identifying appropriate systematic representations particularly challenging [32]. Finding the optimal mathematical model that explains experimental data among a vast number of possible configurations is not trivial; for a system with just five different components, there can be more than 3.3 × 10^7 possible models to test [32].

The selection of an appropriate optimization algorithm is therefore not merely a technical implementation detail but a fundamental strategic decision that can determine the success or failure of a research project. The "No Free Lunch Theorem" reminds us that there is no single optimization algorithm that performs best across all possible problem classes [5]. What constitutes the "right" tool depends critically on the specific problem structure, the nature of the parameters, the computational resources available, and the characteristics of the biological data. This guide provides a structured framework for making this critical selection, enabling researchers in computational systems biology to systematically match algorithm properties to their specific research challenges.

Optimization Problem Classes in Systems Biology

Optimization problems in computational systems biology can be formally expressed as minimizing a cost function, c(θ), that quantifies the discrepancy between model predictions and experimental data, subject to constraints that reflect biological realities [5]. The vector θ contains the p parameters to be estimated, which may include rate constants, scaling factors, or significance thresholds. These parameters may be continuous (e.g., reaction rates) or discrete (e.g., number of genes in a biomarker panel), and are typically subject to bounds and functional constraints reflecting biological plausibility [5].

The principal classes of optimization challenges in systems biology include:

Model Tuning: Estimating unknown parameters in dynamical models, often formulated as systems of differential or stochastic equations, to reproduce experimental time series data [5]. For example, the Lotka-Volterra predator-prey model depends on four parameters (growth rate α, death rate b, consumption rate a, and conversion efficiency β) that must be estimated to match observed population dynamics [5].

Biomarker Identification: Selecting an optimal set of molecular features (e.g., genes, proteins, metabolites) that can accurately classify samples into categories such as healthy/diseased or drug responder/non-responder [5] [33]. This often involves identifying functionally coherent subnetworks or modules within larger biological networks [33].

Network Reconstruction: Inferring the structure and dynamics of gene regulatory networks, signaling pathways, and metabolic networks from high-throughput omics data [33]. This may involve Bayesian network approaches, differential equation models, or other mathematical frameworks to capture signal transduction and regulatory relationships [33].

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Optimization Problem Classes in Computational Systems Biology

| Problem Class | Key Applications | Parameter Types | Objective Function Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Tuning | Parameter estimation for ODE/PDE models, model fitting to time-series data | Continuous (rates, concentrations) | Often non-linear, non-convex, computationally expensive to evaluate |

| Biomarker Identification | Feature selection, disease classification, prognostic signature discovery | Mixed (discrete feature counts, continuous thresholds) | Combinatorial, high-dimensional, may involve ensemble scoring |

| Network Reconstruction | Signaling pathway inference, gene regulatory network modeling, metabolic network modeling | Mixed (discrete network structures, continuous parameters) | Highly structured, often regularized to promote sparsity |

Algorithm Taxonomy and Methodological Foundations

Optimization algorithms can be broadly categorized into three methodological families: deterministic, stochastic, and heuristic approaches [5]. Each employs distinct strategies for exploring parameter space and has characteristic strengths and limitations for systems biology applications.

Deterministic Methods: Multi-Start Non-Linear Least Squares (ms-nlLSQ)

The multi-start non-linear least squares method is based on a Gauss-Newton approach and is primarily applied for fitting experimental data to continuous models [5]. This method operates by initiating local searches from multiple starting points in parameter space, effectively reducing the risk of converging to suboptimal local minima. The technical implementation involves iteratively solving the normal equations for linearized approximations of the model until parameter estimates converge within a specified tolerance.

Key characteristics of ms-nlLSQ include:

- Theoretical Foundation: Rooted in classical optimization theory with proven local convergence properties under specific differentiability conditions [5]

- Parameter Support: Exclusively suited for continuous parameter spaces [5]

- Implementation Considerations: Requires calculation or approximation of Jacobian matrices, with performance dependent on careful selection of initial starting points

Stochastic Methods: Random Walk Markov Chain Monte Carlo (rw-MCMC)

Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods are stochastic techniques particularly valuable when models involve stochastic equations or simulations [5]. The rw-MCMC algorithm explores parameter space through a random walk process, where proposed parameter transitions are accepted or rejected according to probabilistic rules that balance exploration of new regions with exploitation of promising areas.

Distinguishing features of rw-MCMC include:

- Theoretical Foundation: Provides asymptotic convergence to global minima under specific regularity conditions [5]

- Parameter Support: Accommodates both continuous and non-continuous objective functions [5]

- Implementation Considerations: Requires careful tuning of proposal distributions and convergence diagnostics to ensure proper sampling of the target distribution

Heuristic Methods: Genetic Algorithms (sGA) and FAMoS

Genetic Algorithms belong to the class of nature-inspired heuristic methods that have been successfully applied across a broad range of optimization applications in systems biology [5]. The simple Genetic Algorithm (sGA) operates by maintaining a population of candidate solutions that undergo selection, crossover, and mutation operations emulating biological evolution.

The Flexible and dynamic Algorithm for Model Selection (FAMoS) represents a more recent advancement specifically designed for analyzing complex systems dynamics within large model spaces [32]. FAMoS employs a dynamic combination of backward- and forward-search methods alongside a parameter swap search technique that effectively prevents convergence to local minima by accounting for structurally similar processes.

Key attributes of heuristic approaches include:

- Theoretical Foundation: Certain implementations provably converge to global solutions for problems with discrete parameters [5]

- Parameter Support: Handles both continuous and discrete parameters, offering exceptional flexibility [5] [32]

- Implementation Considerations: Requires specification of population sizes (for sGA), genetic operators, and termination criteria; FAMoS needs user-defined cost functions and fitting routines

Decision Framework: Matching Algorithms to Biological Problems

Selecting the appropriate optimization algorithm requires systematic evaluation of both problem characteristics and practical constraints. The following decision framework provides structured guidance for this selection process.

Algorithm Comparison and Selection Guidelines

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Optimization Algorithms for Systems Biology Applications

| Algorithm | Methodological Class | Parameter Space | Convergence Properties | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-start Non-linear Least Squares (ms-nlLSQ) | Deterministic | Continuous parameters only | Proven local convergence; requires multiple restarts for global optimization | Model tuning with continuous parameters; differentiable objective functions; moderate-dimensional problems |

| Random Walk Markov Chain Monte Carlo (rw-MCMC) | Stochastic | Continuous and non-continuous objective functions | Asymptotic convergence to global minimum under specific conditions | Stochastic models; Bayesian inference; posterior distribution exploration; problems with multiple local minima |

| Simple Genetic Algorithm (sGA) | Heuristic (Evolutionary) | Continuous and discrete parameters | Proven global convergence for discrete parameter problems | Mixed-integer problems; biomarker identification; non-differentiable objective functions; complex multi-modal landscapes |

| FAMoS | Heuristic (Model Selection) | Flexible, adaptable to various structures | Dynamical search avoids local minima; suitable for large model spaces | Complex systems dynamics; large model spaces; model selection for ODE/PDE systems; network reconstruction |

Decision Workflow for Algorithm Selection

The following diagram illustrates a systematic workflow for selecting the appropriate optimization algorithm based on problem characteristics:

Implementation Considerations and Best Practices

Successful application of optimization algorithms in computational systems biology requires attention to several practical implementation aspects:

Data Pre-processing: Proper arrangement and cleaning of input datasets is fundamental to successful optimization [34]. This includes random shuffling of data instances, handling of outliers, and normalization of features to comparable scales.

Performance Evaluation: For model selection problems, information criteria such as the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) or Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) provide robust measures for comparing model performance while accounting for complexity [32].

Experimental Design: When applying optimization to experimental systems biology, split datasets into independent training, validation, and test sets, reserving the test set for final evaluation only after completing training and optimization phases [34].

Hyperparameter Tuning: Most optimization algorithms require careful tuning of their own parameters (e.g., population size in genetic algorithms, step sizes in MCMC). Allocate sufficient resources for this meta-optimization process.

Case Studies and Experimental Protocols

Case Study 1: Model Selection for T Cell Proliferation Dynamics

Biological Context: Analysis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferation dynamics in 2D suspension versus 3D tissue-like ex vivo cultures, revealing heterogeneous proliferation potentials influenced by culture conditions [32].

Experimental Protocol:

- Global Model Definition: Define a global model containing all possible interactions and processes thought to play a role in T cell proliferation dynamics

- Algorithm Configuration: Implement FAMoS with a cost function based on negative log-likelihood or information criteria (AICc/BIC)

- Model Search: Execute the FAMoS algorithm with dynamical backward/forward search and parameter swap capabilities

- Validation: Compare identified optimal model against experimental data using goodness-of-fit tests and posterior predictive checks

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Culture Systems: 2D suspension and 3D tissue-like ex vivo cultures for simulating different physiological environments

- Flow Cytometry Reagents: Antibodies for CD4+ and CD8+ cell identification and proliferation tracking

- Computational Environment: R statistical platform with FAMoS package for model selection implementation [32]

Case Study 2: Biomarker Identification for Colorectal Cancer

Biological Context: Identification of population-specific gene signatures across colorectal cancer (CRC) populations from gene expression data using topological and biological feature-based network approaches [33].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Collection: Obtain gene expression datasets from multiple CRC populations

- Network Construction: Build protein-protein interaction networks incorporating Gene Ontology annotations

- Feature Selection: Apply clique connectivity profile (CCP) analysis to identify discriminative network features

- Classification Modeling: Implement genetic algorithm-based feature selection to optimize classification performance while minimizing feature set size

- Validation: Test identified biomarker panels on independent validation cohorts using cross-validation protocols

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Gene Expression Platforms: Microarray or RNA-seq platforms for transcriptomic profiling

- Bioinformatics Databases: Protein-protein interaction networks, Gene Ontology annotations, pathway databases

- Computational Tools: Network analysis software, statistical packages for classification modeling

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for optimization-driven biomarker discovery:

The selection of appropriate optimization algorithms represents a critical strategic decision in computational systems biology research. By understanding the fundamental properties of different algorithm classes and systematically matching them to problem characteristics, researchers can significantly enhance their ability to extract meaningful biological insights from complex data. The framework presented here provides structured guidance for this selection process, emphasizing the importance of aligning algorithmic properties with specific research questions in model tuning, biomarker identification, and network reconstruction.

As the field continues to evolve with increasingly complex datasets and biological questions, the development of more sophisticated optimization approaches remains essential. Future directions will likely include hybrid algorithms that combine the strengths of multiple methodologies, as well as approaches specifically designed to handle the multi-scale, hierarchical nature of biological systems. By maintaining a principled approach to algorithm selection and implementation, researchers can maximize the potential of computational methods to advance our understanding of biological systems.

In computational systems biology, researchers strive to construct quantitative, predictive models of biological systems—from intracellular signaling networks to population-level disease dynamics [5] [35]. A fundamental and recurrent challenge in this endeavor is model tuning or parameter estimation: the process of calibrating a mathematical model's unknown parameters (e.g., reaction rate constants, binding affinities) so that its predictions align with observed experimental data [5] [36]. This calibration is most commonly formulated as a non-linear least squares (NLS) optimization problem, where the goal is to minimize the sum of squared residuals between the model's output and the empirical measurements [5].

However, biological models are inherently complex and non-linear, leading to objective functions that are non-convex and littered with multiple local minima [5] [36]. Traditional gradient-based local optimization algorithms, such as the Levenberg-Marquardt method, are highly efficient but possess a critical flaw: their success is heavily dependent on the initial guess for the parameters. A poor starting point can cause the solver to converge to a suboptimal local minimum, resulting in a model that poorly represents the underlying biology and yields inaccurate predictions [37] [36].

This is where deterministic multi-start strategies prove invaluable. Unlike stochastic global optimization methods (e.g., Genetic Algorithms, Markov Chain Monte Carlo), which use randomness and offer no guarantee of convergence, deterministic multi-start methods provide a systematic and reproducible framework for exploring the parameter space [5] [36]. The core idea is to launch multiple local optimizations from a carefully selected set of starting points distributed across the parameter space. By doing so, the algorithm samples multiple "basins of attraction," increasing the probability of locating the global optimum—the parameter set that provides the best possible fit to the data [37] [5]. This guide delves into the methodology, implementation, and application of Multi-Start Non-Linear Least Squares (ms-nlLSQ) as a robust tool for data fitting in computational systems biology research.

Mathematical Foundations of Non-Linear Least Squares

The parameter estimation problem is formalized as follows. Given a model ( M ) that predicts observables ( \hat{y}i ) as a function of parameters ( \boldsymbol{\theta} = (\theta1, \theta2, ..., \thetap) ) and independent variables ( \boldsymbol{x}i ) (e.g., time, concentration), and a set of ( n ) experimental observations ( { (\boldsymbol{x}i, yi) }{i=1}^n ), the goal is to find the parameter vector ( \boldsymbol{\theta}^* ) that minimizes the sum of squared residuals [5]:

[ \min{\boldsymbol{\theta}} S(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \min{\boldsymbol{\theta}} \sum{i=1}^{n} [yi - M(\boldsymbol{x}i; \boldsymbol{\theta})]^2 = \min{\boldsymbol{\theta}} || \boldsymbol{y} - \boldsymbol{M}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) ||^2_2 ]

The function ( S(\boldsymbol{\theta}) ) is the objective function. In systems biology, ( M ) is often a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs), making ( S(\boldsymbol{\theta}) ) a non-linear, non-convex function of ( \boldsymbol{\theta} ) [36] [35]. Local algorithms iteratively improve an initial guess ( \boldsymbol{\theta}^{(0)} ) by following a descent direction (e.g., the negative gradient or an approximate Newton direction) until a convergence criterion is met. The multi-start framework wraps this local search procedure within a broader global search strategy.

Comparison of Global Optimization Methodologies in Systems Biology

The table below summarizes key properties of ms-nlLSQ against other prominent global optimization methods used in the field, as highlighted in the literature [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Global Optimization Techniques in Computational Systems Biology

| Method | Type | Convergence Guarantee | Parameter Type Support | Key Principle | Typical Application in Systems Biology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Start NLS (ms-nlLSQ) | Deterministic | To local minima from each start point | Continuous | Execute local NLS solver from multiple initial points. | Fitting ODE model parameters to continuous experimental data (e.g., time-course metabolomics) [37] [5]. |

| Random Walk MCMC (rw-MCMC) | Stochastic | Asymptotic to global minimum | Continuous, Non-continuous | Stochastic sampling of parameter space guided by probability distributions. | Bayesian parameter estimation for stochastic models or when incorporating prior knowledge [5]. |

| Genetic Algorithm (sGA) | Heuristic/Stochastic | Not guaranteed (but often effective) | Continuous, Discrete | Population-based search inspired by natural selection (crossover, mutation). | Biomarker identification (discrete feature selection) and model tuning [5]. |

| Deterministic Outer Approximation | Deterministic | To global optimum within tolerance | Continuous | Reformulates problem into mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) to provide rigorous bounds [36]. | Guaranteed global parameter estimation for small to medium-scale dynamic models [36]. |

The Multi-Start Algorithm: A Deterministic Workflow

The efficacy of a multi-start method hinges on intelligent selection of starting points to balance thorough exploration of the parameter space with computational efficiency. The ideal scenario is to initiate exactly one local optimizer within each basin of attraction [37]. In practice, advanced multi-start algorithms aim to approximate this.

A sophisticated implementation, such as the one in the gslnls R package, modifies the algorithm from Hickernell and Yuan (1997) [37]. It can operate with or without pre-defined bounds for parameters. The process dynamically updates promising regions in the parameter space, avoiding excessive computation in regions that lead to already-discovered local minima.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of a generic, yet advanced, deterministic multi-start algorithm for NLS fitting.

Diagram 1: Deterministic Multi-Start NLS Algorithm Workflow (78 characters)

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide with the Hobbs' Weed Infestation Example

To ground the theory in practice, we detail an experimental protocol using a classic example from nonlinear regression analysis: modeling weed infestation over time from Hobbs (1974) [37]. The model is a three-parameter logistic growth curve.

Detailed Methodology

1. Problem Definition & Model Formulation:

- Objective: Fit the logistic model ( y = \frac{b1}{1 + b2 \exp(-b_3 x)} ) to the Hobbs weed dataset, where ( y ) is weed density and ( x ) is time [37].

- Goal: Find the parameter vector ( \boldsymbol{\theta} = (b1, b2, b_3) ) that minimizes the sum of squared residuals.

2. Parameter Space Definition:

- Define plausible lower and upper bounds for each parameter based on biological/physical reasoning. For example:

- ( b1 \in [0, 1000] ) (carrying capacity)

- ( b2 \in [0, 1000] ) (scaling parameter)

- ( b_3 \in [0, 10] ) (growth rate) [37].

- Alternatively, if knowledge is limited for some parameters, their bounds can be left undefined (

NA), allowing the algorithm to dynamically adapt [37].

3. Multi-Start Execution (using gslnls in R):

- Tool: Use the

gsl_nls()function from thegslnlspackage, which provides a built-in multi-start procedure [37] [38]. - Code Implementation:

- Process: The algorithm internally generates candidate start points, runs the local Levenberg-Marquardt solver from each, and retains the best-found solution [37] [38].

4. Solution Analysis & Validation:

- Examine the summary output: parameter estimates, standard errors, and residual sum-of-squares.

- Compare the fit visually and quantitatively to a fit obtained from a single, poorly chosen starting point to illustrate the risk of local minima.

- For the Hobbs example, the global solution is approximately ( (b1, b2, b_3) = (196.1863, 49.0916, 0.3136) ) with a residual sum-of-squares of 2.587 [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Start NLS Fitting

| Item Name | Category | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| gslnls R Package | Software Library | Provides the gsl_nls() function with integrated, advanced multi-start algorithm for solving NLS problems [37] [38]. |

Implements a modified Hickernell & Yuan (1997) algorithm. Requires GNU Scientific Library (GSL). |

| GNU Scientific Library (GSL) | Numerical Library | A foundational C library for numerical computation. Provides robust, high-performance implementations of local NLS solvers (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt) used by gslnls [38]. |

Must be installed (>= v2.3) on the system for installing gslnls from source. |

| NIST StRD Nonlinear Regression Archive | Benchmark Datasets | A collection of certified difficult nonlinear regression problems with reference parameter values and data. Used for validating and stress-testing fitting algorithms [37]. | Example: The Gauss1 problem with 8 parameters [37]. |

| SelfStart Nonlinear Models | Model Templates | Pre-defined nonlinear models in R (e.g., SSlogis, SSmicmen) that contain automatic initial parameter estimation routines, providing excellent starting values for single-start or multi-start routines [37]. |

Useful when applicable to the biological model at hand. |

| Orthogonal Collocation on Finite Elements | Discretization Method | A technique to transform a dynamic model described by ODEs into an algebraic system, making it directly amenable to standard NLS and multi-start optimization frameworks [36]. | Crucial for formulating parameter estimation of ODE models as a standard NLS problem. |

Implementation Guide for Systems Biology Models

Applying ms-nlLSQ to a typical systems biology model involving ODEs requires a specific pipeline. The following diagram and steps outline this process.

Diagram 2: Parameter Estimation Pipeline for ODE Models (73 characters)

Key Steps:

- ODE Model Formulation: Represent the biological network (e.g., metabolic pathway, signaling cascade) as a system of ODEs [5] [35].

- Model Discretization: Use a method like orthogonal collocation on finite elements to transform the continuous-time ODE system into a set of algebraic equations [36]. This is a critical step for using standard NLS solvers.

- Objective Function Definition: Formally define ( S(\boldsymbol{\theta}) ) using the discretized model and the experimental dataset [36].

- Bound Specification: Establish realistic lower and upper bounds (

lb,ub) for all parameters ( \theta ) based on literature or biological constraints [5]. - Multi-Start Execution: Implement the workflow from Diagram 1 using a tool like