Optimization Algorithms for Computational Systems Biology: From Model Tuning to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive review of optimization algorithms powering modern computational systems biology.

Optimization Algorithms for Computational Systems Biology: From Model Tuning to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of optimization algorithms powering modern computational systems biology. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of global optimization—from deterministic and stochastic to nature-inspired heuristic methods. It details their critical applications in calibrating complex biological models, identifying biomarkers, and accelerating drug discovery through GPU-enhanced simulations. The scope extends to methodological advances in AI and quantum computing, practical strategies for overcoming convergence and scalability challenges, and rigorous frameworks for algorithm validation. By synthesizing current methodologies with emerging trends, this review serves as a strategic guide for selecting and implementing optimization techniques to solve pressing problems in biomedicine and therapeutic development.

The Core Principles: Why Optimization is Fundamental to Computational Systems Biology

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between a model parameter and a variable?

In computational models, particularly those based on ordinary differential equations (ODEs), parameters are constants whose values define the model's behavior, such as kinetic rate constants, binding affinities, or scaling factors. Once estimated, these values are fixed. In contrast, variables are the model's internal states that change over time, such as the concentrations of molecules like proteins or metabolites. For example, in a signaling pathway model, the rate of phosphorylation would be a parameter, while the concentration of the phosphorylated protein over time would be a variable [1] [2].

My model fits the training data well but fails to predict new data. What is wrong?

This is a classic sign of overfitting or model non-identifiability. Non-identifiability means that multiple, different sets of parameter values can produce an equally good fit to your initial data, but these parameters may not represent the true underlying biology. To overcome this, you can:

- Reduce Model Complexity: Consider simplifying your model by reducing the number of unknown parameters.

- Collect Additional Data: Generate new experimental data under different conditions or measure additional variables to constrain the model further [1].

- Introduce Constraints: Use mathematical techniques, such as differential elimination, to derive algebraic constraints between parameters, which are then added to the objective function to guide the optimization toward biologically realistic solutions [3].

How do I choose an objective function for my parameter estimation problem?

The choice of objective function is critical and depends on your data and its normalization. Two common approaches are:

- Least-Squares (LS): Minimizes the sum of squared differences between measured and simulated data.

- Log-Likelihood (LL): Used when you have knowledge of the statistical distribution of your measurement noise [1]. A key decision is how to align your simulated data (e.g., in nanomolar concentrations) with your experimental data (often in arbitrary units). The table below compares two standard methods.

| Method | Description | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scaling Factor (SF) | Introduces unknown scaling factors that multiply simulations to match the data scale [1]. | Straightforward to implement. | Increases the number of unknown parameters, which can aggravate non-identifiability [1]. |

| Data-Driven Normalization of Simulations (DNS) | Normalizes simulated data in the exact same way as the experimental data (e.g., dividing by a control or maximum value) [1]. | Does not introduce new parameters, thus avoiding aggravated non-identifiability. Can significantly improve optimization speed [1]. | Requires custom implementation in the objective function, as it depends on the dynamic output of each simulation [1]. |

Which optimization algorithm should I use?

No single algorithm is best for all problems, but some perform well in biological applications. The following table summarizes the properties of several commonly used and effective algorithms.

| Algorithm | Type | Key Features | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| LevMar SE | Deterministic (Gradient-based) | Uses sensitivity equations for efficient gradient calculation; often performs best in speed and accuracy comparisons [1]. | Problems with continuous parameters and objective functions [1] [2]. |

| GLSDC | Hybrid (Heuristic) | Combines a global genetic algorithm with a local Powell's method; effective for complex problems with local minima [1]. | Larger, more complex models where gradient-based methods get stuck [1]. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Heuristic | A population-based search inspired by natural selection; good for exploring large parameter spaces [2] [3]. | Problems with non-convex objective functions or when little is known about good initial parameter values [2]. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | Heuristic | Another population-based method that simulates social behavior [3]. | Similar applications to Genetic Algorithms. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Parameter estimation fails to converge or finds poor fits.

A failure to converge to a good solution can be caused by poorly scaled parameters, ill-defined boundaries, or a difficult error landscape.

- Symptoms:

- The optimization algorithm terminates without meeting convergence criteria.

- The final objective function value is unacceptably high.

- Small changes in initial parameter guesses lead to vastly different results.

- Solutions:

- Parameter Scaling: Ensure all parameters are scaled to have similar orders of magnitude (e.g., between 0.1 and 10). This helps the algorithm navigate the parameter space more efficiently.

- Check Bounds: Define realistic lower and upper bounds for all parameters based on biological knowledge. This drastically reduces the search space.

- Use Multi-Start: Run the optimization from many different, randomly chosen initial parameter sets (e.g., via Latin Hypercube sampling) to find the global minimum rather than a local one [1] [2].

- Switch Algorithms: If a gradient-based method like Levenberg-Marquardt fails, try a heuristic method like a Genetic Algorithm or GLSDC, which are better at escaping local minima [1] [2].

Problem: Model parameters are non-identifiable.

Non-identifiability means that different parameter combinations yield identical model outputs, making it impossible to find a unique solution.

- Symptoms:

- The algorithm finds many different parameter sets with nearly identical goodness-of-fit.

- Parameters have very large confidence intervals.

- Parameters show strong correlations with each other.

- Solutions:

- Apply DNS: Use Data-driven Normalization of Simulations instead of Scaling Factors to avoid introducing unnecessary unknown parameters [1].

- Add Constraints: Incorporate algebraic constraints derived via differential elimination. This technique rewrites your system of ODEs into an equivalent form, providing relationships between parameters and observables that must hold true. Adding these as penalty terms in your objective function can guide the optimization toward accurate, unique solutions [3].

- Reduce Model Complexity: Fix some parameters to literature values or simplify the model structure to reduce the number of free parameters [1].

- Design New Experiments: The most effective solution is often to collect additional data, such as time courses for currently unmeasured variables or data from new perturbation experiments [1].

Experimental Protocol: Parameter Estimation with DNS

This protocol outlines the steps for estimating parameters using the Data-driven Normalization of Simulations (DNS) approach, which has been shown to improve identifiability and convergence speed [1].

1. Problem Formulation

- Model Definition: Define your ODE model ( \frac{d}{dt}x = f(x,\theta) ), where ( x ) is the state vector and ( \theta ) is the parameter vector to be estimated.

- Observable Definition: Define the model outputs ( y = g(x) ) that correspond to your experimental measurements.

2. Data Preprocessing

- Normalize Experimental Data: Apply the same normalization used for your biological replicates to your experimental data ( \hat{y} ). For example, divide all data points by the value of the control condition or the maximum value in the time course to get ( \tilde{y} = \hat{y} / \hat{y}_{ref} ) [1].

3. Implement the Objective Function with DNS

- Simulate: For a given parameter set ( \theta ), run the ODE solver to get the simulated trajectories ( y(t, \theta) ).

- Apply DNS: Normalize the simulated output ( y(t, \theta) ) using the same reference as the data. For instance, ( y{normalized}(t, \theta) = y(t, \theta) / y{ref}(t, \theta) ). Note that ( y_{ref} ) is calculated from the simulation and depends on ( \theta ) [1].

- Calculate Error: Compute the sum of squared errors between the normalized experimental data ( \tilde{y} ) and the normalized simulation ( y_{normalized} ).

4. Optimization and Validation

- Execute Optimization: Use a selected optimization algorithm (see Table 2) to find the parameter set ( \theta^* ) that minimizes the error from the DNS objective function.

- Validate: Assess the fit on a validation dataset not used during estimation and perform identifiability analysis on the estimated parameters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function in the Context of Model Optimization |

|---|---|

| ODE Solver | Software component (e.g., in COPASI, MATLAB, or Python's SciPy) that numerically integrates the differential equations to simulate model trajectories for a given parameter set [1]. |

| Sensitivity Equations Solver | Computes how model outputs change with respect to parameters. This gradient information is used by algorithms like LevMar SE to efficiently navigate the parameter space [1]. |

| Differential Elimination Software | Algebraic tool (e.g., in Maple or Mathematica) used to rewrite a system of ODEs, revealing hidden parameter constraints that can be added to the objective function to improve estimation accuracy [3]. |

| Global Optimization Toolbox | A software library containing implementations of algorithms like Genetic Algorithms, Particle Swarm Optimization, and multi-start methods for robust parameter estimation [2] [3]. |

| Tolbutamide-13C | Tolbutamide-13C Stable Isotope |

| Antibacterial agent 100 | Antibacterial Agent 100|C28H29BrN2|HY-146060 |

Troubleshooting Guide: Optimization Algorithms in Computational Systems Biology

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My optimization algorithm gets stuck in a suboptimal solution when modeling metabolic networks. How can I improve its exploration of the solution space?

A1: This is a classic symptom of an algorithm trapped by a local optimum in a multimodal landscape. In nonlinear problems, the solution space often contains multiple good solutions (modes), and standard algorithms can prematurely converge on one. To address this:

- Implement Niching or Speciation: Use algorithms like Niching Particle Swarm Optimization or a Knowledge-Driven Brain Storm Optimization (KBSOOS) that actively maintain multiple, diverse solution subpopulations. This prevents a single good solution from dominating the entire search process too early [4].

- Hybrid Global-Local Search: Adopt a coevolutionary mechanism that combines a global explorer (e.g., Monte Carlo Tree Search) with a local refiner (e.g., an Evolutionary Algorithm). This allows for broad exploration while still thoroughly investigating promising regions [5].

- Check Problem Formulation: The non-convex nature of your objective function or constraints may be creating a highly fragmented feasible region. Simplifying the model or using constraint relaxation strategies can sometimes make the landscape more navigable [5].

Q2: According to the 'No Free Lunch' Theorem, no single algorithm is best for all problems. How should I systematically select an algorithm for my specific biological model?

A2: The 'No Free Lunch' (NFL) theorem indeed states that when averaged over all possible problems, no algorithm outperforms any other [6] [7]. This makes algorithm selection a critical, knowledge-driven step.

- Exploit Prior Information: NFL tells us that improvement hinges on using prior information to match procedures to problems [6]. Analyze the known properties of your biological system. Does it have smooth, differentiable dynamics? Use gradient-based methods. Is it discrete and combinatorial? Consider evolutionary or swarm intelligence algorithms [8].

- Benchmark with Purpose: Don't just test algorithms at random. Select a small set of algorithms that are well-suited to the structure of your problem (e.g., nonlinear, constrained, high-dimension) and benchmark them on a simplified version of your model. The goal is to find the best tool for your specific class of problem, not for all problems [7].

- Consider a Meta-Learning Approach: To circumvent NFL, you can lift the problem to a meta-level. Develop a portfolio of algorithms and use a selector to choose the most appropriate one based on the features of the specific problem instance at hand [7].

Q3: How can I handle the high computational cost of optimizing non-convex, multi-modal models, which is common in systems biology?

A3: The computational complexity of Nonlinear Combinatorial Optimization Problems (NCOPs) is a fundamental hurdle [5]. Several strategies can help manage this:

- Knowledge-Driven Optimization: Move from "black-box" to "gray-box" optimization. Incorporate known biological constraints and domain knowledge directly into the algorithm to prune the search space and guide the search more efficiently, reducing wasteful function evaluations [4].

- Constraint Relaxation: For problems with complex constraints, temporarily relax them to create a simpler, surrogate problem. Find good solutions in this relaxed space and then refine them to satisfy the original constraints. This can be automated using structured reasoning with Large Language Models (LLMs) to generate relaxation strategies [5].

- Algorithm Tuning and Zero-Order Methods: If your model is a black box where gradients are unavailable or unreliable, focus on efficient zero-order routines (e.g., some evolutionary algorithms) that use only objective function values. Properly tuning their parameters (population size, mutation rates) can significantly enhance performance [8].

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Optimization Algorithms for a Multimodal Problem

This protocol provides a methodology for comparing the performance of different optimization algorithms on a benchmark multimodal function, simulating the challenge of finding multiple optimal solutions in a biological network.

1. Objective: To evaluate and compare the ability of different algorithms to locate multiple global and local optima in a single run.

2. Materials and Reagents (Computational):

- Software: Python 3.8+ with scientific libraries (NumPy, SciPy).

- Algorithms: Implementations of Niching Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Differential Evolution (DE), and a Knowledge-Driven Brain Storm Optimization (BSO) variant [4].

- Benchmark Function: The Two-Peak Trap Function [4]. This is a standard function used to test multimodal optimization capabilities.

3. Procedure: 1. Initialization: * For each algorithm, initialize a population of 50 candidate solutions uniformly distributed across the predefined search space. * Set a maximum function evaluation budget of 50,000 for all algorithms to ensure a fair comparison. 2. Execution: * Run each algorithm on the Two-Peak Trap Function. Ensure that the niching parameters (e.g., niche radius for PSO) are set according to literature standards for the chosen benchmark. * Each algorithm should be run for 50 independent trials with different random seeds to gather statistically significant results. 3. Data Collection: * At the end of each run, record all found solutions and their fitness values. * Calculate the following performance metrics for each run [4]: * Optima Ratio (OR): The proportion of all known optima that were successfully located. * Success Rate (SR): The percentage of independent runs in which all global optima were found. * Proposed Diversity Indicator: A measure of how well the found solutions are distributed across the different optima basins, providing a fuller picture than OR or SR alone [4].

4. Analysis: * Compile the results from all trials into a summary table. * Perform a statistical test (e.g., Wilcoxon rank-sum test) to determine if there are significant differences in the performance of the algorithms. * The algorithm with the highest average OR and Diversity Indicator, and a consistently high SR, can be considered the most effective for this type of multimodal problem.

Performance Metrics Table for Multimodal Optimization

The table below summarizes key metrics for evaluating algorithms on multimodal problems [4].

| Metric Name | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Optima Ratio (OR) | The proportion of all known optima that were successfully located. | Closer to 1.0 indicates a more successful search. |

| Success Rate (SR) | The percentage of independent runs in which all global optima were found. | Higher is better; indicates consistency. |

| Convergence Speed (CS) | The average number of function evaluations required to find all global optima. | Lower is better; indicates higher efficiency. |

| Diversity Indicator | A measure of the distribution of found solutions across different optima basins. | Higher values indicate better diversity maintenance. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key computational "reagents" and their roles in designing optimization experiments for computational systems biology.

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Evolutionary Algorithm (EA) | A population-based metaheuristic inspired by natural selection, effective for global exploration of complex, non-convex solution spaces [5]. |

| Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) | A method for systematic decision-making and strategy exploration, useful for guiding searches in combinatorial spaces [5]. |

| Brain Storm Optimization (BSO) | A swarm intelligence algorithm that uses clustering and idea-generation concepts to organize search and maintain diversity [4]. |

| Constraint Relaxation Strategy | A technique to temporarily simplify non-convex constraints, making the problem more tractable for initial optimization phases [5]. |

| Niching/Speciation Mechanism | A subroutine within an algorithm that forms and maintains subpopulations around different optima, crucial for solving multimodal problems [4]. |

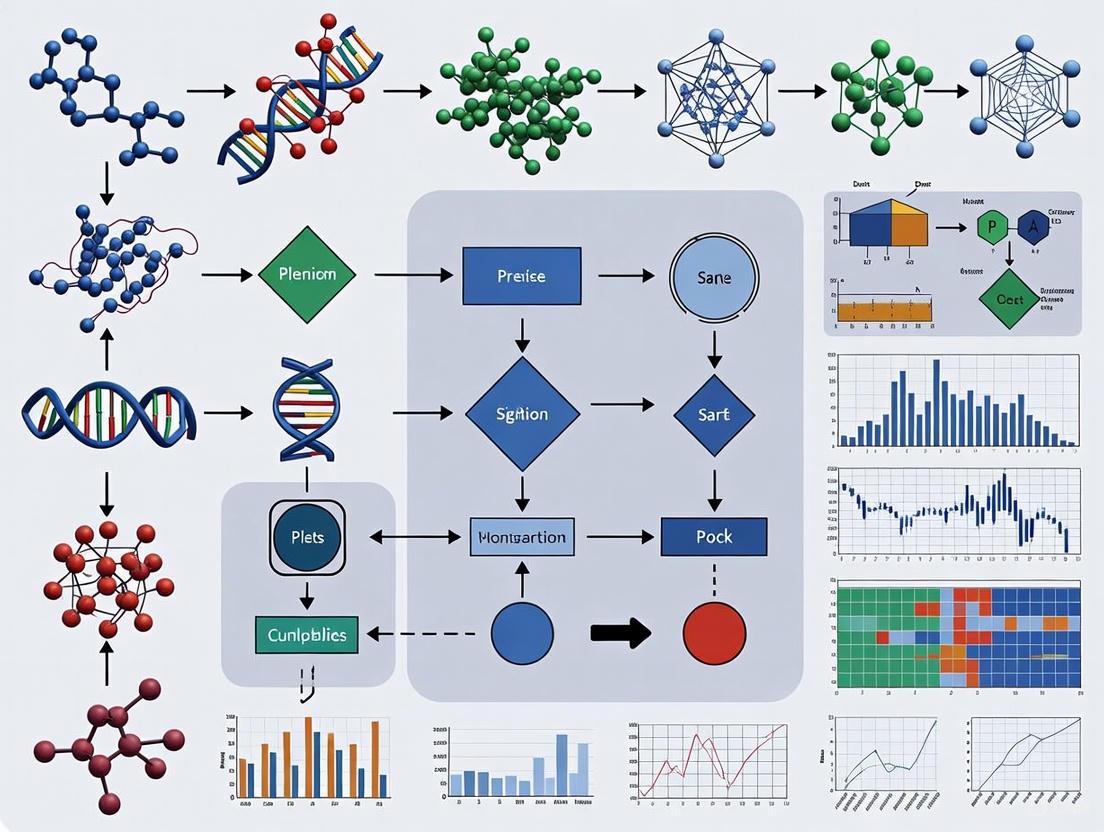

Workflow Diagram: A Knowledge-Driven Optimization Framework

The diagram below illustrates a modern, knowledge-driven framework for tackling complex optimization problems in computational systems biology, which leverages insights to navigate the challenges posed by non-linearity and multi-modality [4] [5].

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the fundamental difference between deterministic and stochastic global optimization methods?

Deterministic methods provide theoretical guarantees of finding the global optimum by exploiting problem structure, and they will always produce the same result when run repeatedly on the same problem [9] [10]. In contrast, stochastic methods incorporate random processes, which means they can return different results on different runs; they do not guarantee a global optimum but often find a "good enough" solution in a feasible time [2] [9] [11].

2. My stochastic optimization algorithm returns a different "best" solution each time it runs. Is it broken?

No, this is expected behavior. Stochastic algorithms, like Genetic Algorithms or Particle Swarm Optimization, use random sampling to explore the solution space. This variability helps escape local optima [2] [11]. The solution is to run the algorithm multiple times and select the best solution from all runs, or to use a fixed random seed to make the results reproducible [11].

3. When should I choose a heuristic method over a deterministic one for my biological model?

Heuristic methods are particularly suitable when your problem has a large, complex search space, when the objective function is "black-box" (you cannot exploit its mathematical structure), or when you have limited computation time and a "good enough" solution is acceptable [12] [9]. Deterministic methods are best when the global optimum is strictly required and the problem structure (e.g., convexity) can be exploited, though they may become infeasible for very large or complex problems [12] [9].

4. What does it mean if my optimization algorithm finds many local optima with high variability?

Finding multiple local optima is common in non-convex problems, which are frequent in systems biology [12]. High variability in the solutions can indicate a "flat" objective function region or that the algorithm is effectively exploring the search space rather than converging prematurely [11]. If this variability is problematic, you might need to reformulate your objective function or consider a different optimization algorithm.

5. How can I decide which optimization algorithm is best for parameter estimation in my dynamic model?

The choice often depends on the model's characteristics and your goals. For deterministic models, multi-start least squares methods can be effective [2]. For models involving stochastic equations or simulations, Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods are a natural choice [2]. If some parameters are discrete or the problem is very complex, a heuristic method like a Genetic Algorithm may be most suitable [2] [12].

Troubleshooting Common Optimization Problems

| Problem Description | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Algorithm converges to a poor local optimum | • Poor initial guess.• Inadequate exploration of search space.• Step size too small. | • Use a multi-start approach [2].• Employ a global optimization algorithm (e.g., GA, MCMC) [2] [12].• Adjust algorithm parameters (e.g., increase mutation rate in GA). |

| Optimization takes too long | • High-dimensional parameter space.• Costly objective function evaluation (e.g., simulating a large model).• Inefficient algorithm. | • Use a surrogate model (e.g., DNN) to approximate the objective function [13].• If possible, use a stochastic method for controllable time [9].• Reduce problem dimensionality if possible. |

| High variability in results (Stochastic Methods) | • Inherent randomness of the algorithm.• Insufficient number of algorithm runs. | • Use a fixed random seed for reproducibility [11].• Aggregate results from multiple independent runs. |

| Solution violates constraints | • Constraints not properly implemented.• Algorithm does not handle constraints well. | • Use penalty functions to incorporate constraints into the objective function.• Choose an algorithm designed for constrained optimization. |

Comparison of Global Optimization Methods

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the three main global optimization strategies [2] [12] [9].

| Feature | Deterministic | Stochastic | Heuristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Optimum Guarantee | Yes (theoretical) | Stochastic (guaranteed only with infinite time) | No guarantee |

| Problem Models | LP, IP, NLP, MINLP | Any model | Any model, especially complex black-box |

| Typical Execution Time | Can be very long | Controllable | Controllable |

| Handling of Discrete/Continuous Vars | Mixed (e.g., MINLP) | Continuous & Discrete [2] | Continuous & Discrete [2] |

| Example Algorithms | Branch-and-Bound, αBB [10] | Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) [2] | Genetic Algorithms (GA), Particle Swarm [2] [14] |

| Best for | Problems where global optimum is mandatory and problem structure is exploitable. | Finding a good solution in limited time for complex problems; models with stochasticity [2]. | Very complex, high-dimensional problems where a good-enough solution is acceptable [12] [13]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Computational Optimization |

|---|---|

| Multi-start Algorithm | A deterministic strategy to run a local optimizer from multiple initial points to find different local optima and increase the chance of finding the global one [2]. |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) | A stochastic method particularly useful for fitting models that involve stochastic equations or for performing Bayesian inference [2]. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | A nature-inspired heuristic that uses operations like selection, crossover, and mutation on a population of solutions to evolve toward an optimum [2] [12]. |

| Deep Neural Network (DNN) Surrogate | A deep learning model used to approximate a complex, expensive-to-evaluate objective function, drastically speeding up the optimization process [13]. |

| Convex Relaxation | A deterministic technique used to find a lower bound for the global optimum in non-convex problems by solving a related convex problem [10]. |

| ATX inhibitor 7 | ATX inhibitor 7, MF:C21H22F3N7O2, MW:461.4 g/mol |

| Jak3-IN-9 | Jak3-IN-9, MF:C17H23N5O4S, MW:393.5 g/mol |

Methodological Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the general workflows for the primary optimization strategies.

Deterministic Global Optimization Workflow

Stochastic/Heuristic Optimization Workflow

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Hub

This section provides targeted solutions for common challenges researchers face when implementing nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithms in computational systems biology.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm converges to a local optimum prematurely when tuning parameters for my differential equation model of cell signaling. How can I improve its exploration?

- Problem: Premature convergence is often caused by a loss of population diversity.

- Solutions:

- Adjust Algorithm Parameters: Experiment with increasing the inertia weight or social/cognitive parameters to encourage broader exploration of the parameter space [15].

- Use a Variant: Switch to a more advanced algorithm like the Competitive Swarm Optimizer with Mutated Agents (CSO-MA). Its mutation step allows particles to explore more distant regions, helping the swarm escape local optima [15].

- Hybrid Approach: Combine PSO with a local search method. Let PSO identify a promising region, then use a deterministic method to fine-tune the solution [2].

Q2: For biomarker identification, I need an optimizer that handles both continuous (significance thresholds) and discrete (number of features) parameters. Which algorithm is suitable?

- Problem: Many standard optimization algorithms are designed for either continuous or discrete spaces, but not both.

- Solution: Genetic Algorithms (GAs) are well-suited for this. Their representation using chromosomes can be easily adapted to include both real-valued and integer-valued genes, making them ideal for mixed-parameter problems like feature selection [2].

Q3: The objective function for my model tuning is computationally expensive to evaluate (each call involves a stochastic simulation). How can I optimize efficiently?

- Problem: Running a full metaheuristic requires thousands of function evaluations, which is infeasible with slow, simulation-based objectives.

- Solutions:

- Surrogate Modeling: Replace the expensive simulation with a cheaper surrogate model (e.g., a Gaussian Process or neural network) that approximates the input-output relationship. The optimizer runs on the surrogate [2].

- Algorithm Selection: Consider using a method like Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), which, in implementations like random walk MCMC (rw-MCMC), can be effective for problems involving stochastic simulations and typically requires fewer evaluations per iteration than population-based methods [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Algorithm Pitfalls

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor convergence or erratic performance | Incorrect algorithm hyperparameters (e.g., swarm size, mutation rate). | Run the algorithm on a simple benchmark function with known optimum. | Systematically tune hyperparameters. Refer to literature for recommended values [15]. |

| Results are not reproducible | Random number generator not seeded. | Run the same optimization twice and check for identical results. | Set a fixed seed at the start of your code to ensure reproducibility. |

| Algorithm is too slow | High-dimensional problem or expensive objective function. | Profile your code to identify bottlenecks. | Consider dimension reduction techniques for your data or use a surrogate model [2]. |

| Constraint violations in final solution | Ineffective constraint-handling method. | Check if the algorithm has a built-in mechanism for constraints (e.g., penalty functions). | Implement a robust constraint-handling technique, such as a dynamic penalty function or a feasibility-preserving mechanism. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in the field.

Protocol 1: Model Parameter Tuning using Competitive Swarm Optimizer with Mutated Agents (CSO-MA)

Application: Estimating unknown parameters (e.g., rate constants) in a systems biology model (e.g., a predator-prey model or a cell cycle model) to fit experimental time-series data [15] [2].

Detailed Methodology:

Problem Formulation:

- Objective Function: Define a cost function, typically a sum of squared errors (SSE), that quantifies the difference between your model's output and the experimental data.

- Parameter Space: Define the lower and upper bounds (

lbandub) for each parameter to be estimated.

Algorithm Initialization:

- Swarm Size: Generate an initial swarm of

nparticles (e.g.,n = 100). Each particle's position is a random vector within the defined parameter bounds. - Velocities: Initialize particle velocities to zero or small random values.

- Swarm Size: Generate an initial swarm of

CSO-MA Iteration:

- Pairing and Competition: Randomly partition the swarm into pairs. In each pair, compare the objective function values. The particle with the better (lower) value is the winner, the other is the loser.

- Loser Update: The loser updates its velocity and position by learning from the winner and the swarm center [15].

v_j^{t+1} = R1 * v_j^t + R2 * (x_i^t - x_j^t) + φ * R3 * (x̄^t - x_j^t)x_j^{t+1} = x_j^t + v_j^{t+1}- where

R1, R2, R3are random vectors,φis the social factor, andx̄^tis the swarm center.

- Mutation: Randomly select a loser particle and a variable (parameter) within it. Mutate that parameter by setting it to either its minimum or maximum bound. This step enhances diversity [15].

Termination: Repeat Step 3 until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., a maximum number of iterations or convergence tolerance is achieved).

Protocol 2: Biomarker Identification using Genetic Algorithms (GAs)

Application: Selecting an optimal, small subset of features (genes, proteins) from high-dimensional omics data to classify samples (e.g., healthy vs. diseased) [2].

Detailed Methodology:

Problem Formulation:

- Objective Function: Typically a combination of classification accuracy (e.g., from a SVM or random forest classifier) and a penalty for the number of features selected (to promote parsimony).

- Representation: Encode a potential solution (a subset of features) as a binary chromosome. Each gene in the chromosome is a

1(feature included) or0(feature excluded).

Algorithm Initialization: Create an initial population of

Nrandom binary chromosomes.GA Iteration:

- Evaluation: Compute the fitness (objective function value) for each chromosome in the population.

- Selection: Select parent chromosomes for reproduction, with a probability proportional to their fitness (e.g., using roulette wheel or tournament selection).

- Crossover: Recombine pairs of parents to produce offspring. For binary chromosomes, single-point or uniform crossover is common.

- Mutation: Randomly flip bits (

0to1or vice versa) in the offspring with a small probability.

Termination: Repeat the iteration until convergence or a maximum number of generations is reached. The best chromosome in the final population represents the selected biomarker.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential computational tools and their functions for implementing nature-inspired metaheuristics in computational systems biology.

| Tool / Resource | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| CSO-MA (Matlab/Python) | Swarm-based algorithm for continuous parameter optimization (e.g., model tuning). | Superior performance on high-dimensional problems; mutation step prevents premature convergence [15]. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Evolutionary algorithm for mixed-integer optimization (e.g., biomarker identification). | Handles continuous and discrete parameters; uses selection, crossover, and mutation [2]. |

| PySwarms (Python) | A comprehensive toolkit for Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO). | User-friendly; includes various PSO variants and visualization tools [15]. |

| Random Walk MCMC | Stochastic technique for optimization, especially with stochastic models. | Suitable when objective function involves stochastic simulations; supports non-continuous functions [2]. |

| Multi-start nlLSQ | Deterministic approach for non-linear least squares problems (e.g., data fitting). | Efficient for continuous, convex problems; can be trapped in local optima for complex landscapes [2]. |

| Antiplatelet agent 2 | Antiplatelet Agent 2|Research Compound | Antiplatelet Agent 2 is a potent P2Y12 ADP receptor antagonist for cardiovascular disease research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| (4-NH2)-Exatecan | (4-NH2)-Exatecan, MF:C23H21N3O4, MW:403.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Performance Data & Benchmarking

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Metaheuristics on Benchmark Functions [15]

| Algorithm | Average Error (Function f₉) | Average Error (Function fâ‚â‚€) | Average Error (Function fâ‚â‚) | Key Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSO-MA | 3.2e-12 | 5.8e-08 | 2.1e-09 | Excellent global exploration and convergence accuracy. |

| Standard PSO | 7.5e-09 | 2.3e-05 | 4.7e-07 | Good balance of speed and accuracy. |

| Basic CSO | 5.1e-11 | 1.1e-06 | 8.9e-08 | Robust performance on separable functions. |

Table 2: Algorithm Suitability for Systems Biology Tasks [2]

| Task | Recommended Algorithm(s) | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Model Tuning (Deterministic ODEs) | CSO-MA, Multi-start nlLSQ | Handles continuous parameters; efficient for non-linear cost functions. |

| Model Tuning (Stochastic Sims) | rw-MCMC, GA | Effective for noisy, simulation-based objective functions. |

| Biomarker Identification | Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Naturally handles discrete (feature count) and continuous (thresholds) parameters. |

| High-Dimensional Problems | CSO-MA, PSO | Swarm-based algorithms scale well with problem dimension [15]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most suitable global optimization methods for parameter estimation in dynamic biological models? For estimating parameters in dynamic biological models like systems of differential equations, Multi-Start Non-Linear Least Squares (ms-nlLSQ) is widely used when dealing with deterministic models and continuous parameters [2]. For models involving stochasticity, Random Walk Markov Chain Monte Carlo (rw-MCMC) methods are more appropriate as they can handle non-continuous objective functions and complex probability landscapes [2]. When facing problems with mixed parameter types (continuous and discrete) or highly complex, non-convex search spaces, Genetic Algorithms (GAs) provide robust heuristic approaches inspired by natural evolution [2] [12].

How do I choose between deterministic, stochastic, and heuristic optimization approaches for my systems biology problem? Your choice depends on the problem characteristics and parameter types. Deterministic methods like ms-nlLSQ are suitable only for continuous parameters and objective functions, offering faster convergence but requiring differentiable functions [2]. Stochastic methods like rw-MCMC support both continuous and non-continuous objective functions, making them ideal for stochastic models and when you need global optimization guarantees [2]. Heuristic methods like GAs are most flexible, supporting both continuous and discrete parameters, and excel in complex, multimodal landscapes though they don't always guarantee global optimality [2] [12].

Why do many optimization methods in computational systems biology perform poorly on my large-scale models? Many biological optimization problems belong to the class of NP-hard problems where obtaining guaranteed global optima becomes computationally infeasible as model size increases [12]. This is particularly true for problems like identifying gene knockout strategies in genome-scale metabolic models, which have combinatorial complexity [12]. Solutions include using approximate stochastic global optimization methods that find near-optimal solutions efficiently, or developing hybrid methods that combine global and local techniques [12].

What principles from biological systems have inspired computational optimization algorithms? Evolutionary principles of selection, recombination, and mutation have inspired Genetic Algorithms that evolve solution populations toward optimality [2]. The stochastic behavior of molecular systems has informed Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods that explore solution spaces probabilistically [2]. Additionally, the robustness and redundancy observed in biological networks have inspired optimization approaches that maintain diversity and avoid premature convergence to suboptimal solutions [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Optimization Algorithm Converging to Poor Local Solutions

Symptoms: Your parameter estimation consistently returns biologically implausible values, or small changes to initial conditions yield dramatically different results.

Diagnosis: You are likely dealing with a multimodal, non-convex objective function with multiple local minima, which is common in biological systems due to their inherent complexity and redundancy [2] [16].

Solutions:

- Implement multi-start strategies: Run local optimizers from multiple randomly chosen starting points to better explore the parameter space [2].

- Switch to global optimization methods: Use stochastic methods like rw-MCMC or heuristic methods like Genetic Algorithms that are designed to escape local minima [2].

- Reformulate your objective function: Sometimes, the problem can be reformulated as a convex optimization problem, which guarantees finding the global solution [12].

Verification: A well-tuned optimizer should produce consistent results across multiple runs with different random seeds, and the resulting parameters should generate model behaviors that qualitatively match experimental observations.

Problem: Unacceptable Computational Time for Large-Scale Models

Symptoms: Optimization runs take days or weeks to complete, making research progress impractical.

Diagnosis: You may be facing the curse of dimensionality with too many parameters, or your objective function evaluations (e.g., model simulations) may be computationally expensive.

Solutions:

- Employ efficient global optimization (EGO) methods: These methods build surrogate models of the objective function to reduce the number of expensive function evaluations [12].

- Utilize parallel computing: Many optimization algorithms, particularly population-based methods like Genetic Algorithms, can be parallelized to distribute function evaluations across multiple processors [17].

- Simplify your model: Identify and remove negligible reactions or parameters through sensitivity analysis before optimization.

- Use hybrid methods: Combine fast global explorers with efficient local refiners to balance exploration and exploitation [12].

Verification: Monitor optimization progress over time; effective optimizers should show significant improvement in initial iterations with diminishing returns later.

Problem: Handling Stochastic Models and Noisy Data

Symptoms: Optimization results vary dramatically between runs despite identical settings, making conclusions unreliable.

Diagnosis: Your model may have inherent stochasticity (e.g., biochemical reactions with low copy numbers) or your experimental data may have significant measurement noise [12].

Solutions:

- Use specialized stochastic optimization methods: Methods like rw-MCMC are specifically designed for problems where the objective function involves stochastic simulations or noisy evaluations [2].

- Implement appropriate averaging: For stochastic models, run multiple simulations at each parameter point and optimize based on average behavior.

- Apply robust optimization techniques: These methods explicitly account for uncertainty in parameters and measurements [17].

- Utilize optimal experimental design: Plan experiments to maximize information gain while minimizing noise impact [12].

Verification: For stochastic problems, focus on statistical properties of solutions rather than single runs, and use techniques like cross-validation to assess generalizability.

Optimization Methods Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Global Optimization Methods in Computational Systems Biology

| Method | Parameter Types | Objective Function | Convergence | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Start Non-Linear Least Squares (ms-nlLSQ) | Continuous only | Continuous | Local minimum | Deterministic models, continuous parameters [2] |

| Random Walk Markov Chain Monte Carlo (rw-MCMC) | Continuous | Continuous & non-continuous | Global minimum (under specific hypotheses) | Stochastic models, probabilistic inference [2] |

| Genetic Algorithms (GAs) | Continuous & discrete | Continuous & non-continuous | Global minimum for discrete problems | Complex multimodal landscapes, mixed parameter types [2] |

Table 2: Algorithm Selection Guide Based on Problem Characteristics

| Problem Feature | Recommended Methods | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Model Type | Deterministic: ms-nlLSQ; Stochastic: rw-MCMC, GAs | Stochastic models require methods robust to noise [2] [12] |

| Parameter Types | Continuous: ms-nlLSQ, rw-MCMC; Mixed: GAs | Discrete parameters exclude pure continuous methods [2] |

| Scale | Small: ms-nlLSQ; Large: GAs with hybridization | NP-hard problems require approximate methods for large scales [12] |

| Computational Budget | Limited: ms-nlLSQ; Extensive: GAs, rw-MCMC | Stochastic and heuristic methods typically need more function evaluations [2] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Parameter Estimation Using Multi-Start Least Squares

Purpose: Estimate unknown parameters in deterministic biological models to reproduce experimental time series data.

Materials:

- Experimental time course data

- Mathematical model (system of ODEs or PDEs)

- Computational implementation of model equations

- Optimization software (MATLAB, Python SciPy, R optim)

Procedure:

- Formulate objective function: Define sum of squared differences between model simulations and experimental data.

- Set parameter bounds: Define biologically plausible lower and upper bounds for all parameters.

- Generate starting points: Create multiple (typically 100-1000) randomly sampled parameter vectors within bounds.

- Run local optimizations: From each starting point, perform local least-squares optimization.

- Cluster solutions: Group similar solutions to identify distinct local minima.

- Select best solution: Choose parameter set with lowest objective function value.

- Validate results: Test optimized parameters with withheld experimental data.

Troubleshooting Notes: If solutions cluster into many distinct groups, your model may be unidentifiable - consider simplifying the model or collecting additional data [2].

Protocol 2: Biomarker Identification Using Genetic Algorithms

Purpose: Identify minimal sets of features (genes, proteins) that optimally classify biological samples.

Materials:

- Omics dataset (genomic, proteomic, metabolomic) with sample classes

- Computing environment with GA implementation (Python DEAP, R GA, MATLAB Global Optimization Toolbox)

Procedure:

- Encode solutions: Represent biomarker sets as binary strings (1=feature included, 0=excluded).

- Define fitness function: Combine classification accuracy (e.g., SVM or random forest) with penalty for large feature sets.

- Initialize population: Create random population of candidate biomarker sets.

- Evaluate fitness: Assess classification performance of each candidate set using cross-validation.

- Apply genetic operators:

- Selection: Preferentially retain high-fitness solutions

- Crossover: Combine parts of parent solutions to create offspring

- Mutation: Randomly flip bits to maintain diversity

- Iterate: Repeat evaluation and genetic operations for generations until convergence.

- Validate final set: Test best biomarker set on independent validation dataset.

Troubleshooting Notes: If algorithm converges too quickly, increase mutation rate or population size to maintain diversity [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Optimization in Computational Systems Biology

| Research Reagent | Function | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Global Optimization Algorithms | Navigate complex, multimodal parameter spaces to find optimal solutions | Multi-start methods, Genetic Algorithms, MCMC [2] |

| Model Tuning Software | Estimate unknown parameters to fit models to experimental data | Nonlinear least-squares, maximum likelihood estimation [2] |

| Biomarker Identification Tools | Select optimal feature subsets for sample classification | Wrapper methods with evolutionary computation [2] |

| Metabolic Flux Analysis | Determine optimal flux distributions in metabolic networks | Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), constraint-based modeling [12] |

| Optimal Experimental Design | Plan experiments to maximize information gain | Fisher information maximization, parameter uncertainty reduction [12] |

| Antibacterial agent 106 | Antibacterial Agent 106|Potent Anti-MRSA Compound | Antibacterial agent 106 is an orally active compound with potent efficacy against multidrug-resistant Gram-positive pathogens, including MRSA. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| AChE-IN-10 | AChE-IN-10, MF:C23H27F2NO4S, MW:451.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Visualization

Optimization Workflow in Systems Biology

Biological Inspiration for Computational Algorithms

From Theory to Practice: Algorithmic Strategies and Their Biomedical Applications

Multi-start Non-Linear Least Squares (ms-nlLSQ) for Deterministic Model Tuning

Computational systems biology aims to gain mechanistic insights into biological phenomena through dynamical representations of biological systems. A fundamental task in this field is model tuning, which involves estimating unknown parameters in models, such as rate constants in systems of differential equations, to accurately reproduce experimental time-series data [2]. This problem is frequently formulated as a nonlinear least-squares (NLS) optimization problem, where the goal is to minimize the sum of squared differences between experimental observations and model predictions [2] [18].

Standard NLS solvers, such as the Gauss-Newton or Levenberg-Marquardt algorithms, are local optimization methods that iteratively improve an initial parameter guess. However, these methods possess a significant limitation: they can converge to local minima rather than the global optimum, and their success is highly dependent on the quality of the initial parameter values [2] [19]. This is particularly problematic in systems biology, where model parameters are often correlated and objective functions can be non-convex with multiple local solutions [2] [19].

The Multi-start Non-Linear Least Squares (ms-nlLSQ) approach directly addresses this challenge. It works by launching a local NLS solver, such as a Gauss-Newton method, from multiple different starting points within the parameter space [2]. The solutions from all these starts are collected and ranked by their goodness-of-fit (e.g., the lowest residual sum of squares), and the best solution is selected. This strategy significantly increases the probability of locating the global minimum rather than being trapped in a suboptimal local minimum [20].

Key Concepts and Mathematical Formulation

The Nonlinear Least-Squares Problem

In the context of model tuning, the NLS problem is typically formulated as follows [18]:

Let ( Yi ) represent the (i)-th observed data point, and ( f(\mathbf{x}i, \boldsymbol{\theta}) ) be the model prediction for the inputs ( \mathbf{x}i ) and parameter vector ( \boldsymbol{\theta} = (\theta1, \ldots, \thetap) ). The objective is to find the parameter values ( \hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}} ) that minimize the sum of squared residuals: [ \min{\boldsymbol{\theta}} S(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \sum{i=1}^{n} \big[Yi - f(\mathbf{x}i, \boldsymbol{\theta})\big]^2 ] The vector form of the objective function for the solver is: [ \min{\boldsymbol{\theta}} \|\mathbf{f}(\boldsymbol{\theta})\|2^2 ] where ( \mathbf{f}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) ) is a vector-valued function whose components are the residuals ( fi(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = Yi - f(\mathbf{x}i, \boldsymbol{\theta}) ) [21]. It is crucial to provide the solver with this vector of residuals, not the scalar sum of their squares [21].

The Multi-Start Strategy

A "start" or "initial point" refers to a single initial guess for the parameter vector ( \boldsymbol{\theta}^{(0)} ) from which a local NLS solver begins its iterative process [20]. The fundamental idea behind ms-nlLSQ is that by initiating searches from a diverse set of points spread throughout the parameter space, the algorithm can explore different "basins of attraction" [22]. The best solution from all the local searches is chosen as the final estimate for the global minimum.

Implementation and Software Tools

The following diagram illustrates the complete ms-nlLSQ workflow, from problem definition to solution validation.

Software Implementations in R and MATLAB

Various software packages provide implementations of the ms-nlLSQ approach. The table below summarizes key tools available in R and MATLAB environments.

Table 1: Software Implementations of ms-nlLSQ

| Software Environment | Package/Function | Key Features | Local Solver Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| R | nls_multstart (from nls.multstart package) |

Uses AIC scores with Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm; multiple starting values [23] [24]. | Levenberg-Marquardt (via minpack.lm) [24] |

| R | nls2 |

Performs brute-force, grid-search, or random-search for multiple trials [23]. | Base R nls() [23] |

| R | gsl_nls (from gslnls package) |

Modified multistart procedure; can dynamically update parameter ranges; interfaces with GSL library [22]. | GSL Levenberg-Marquardt [22] [25] |

| MATLAB | MultiStart with lsqnonlin |

Creates multiple start points automatically; can plot best function value during iteration [20]. | lsqnonlin [20] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Software Tools for ms-nlLSQ Implementation

| Tool Name | Environment | Primary Function | Typical Use Case in Systems Biology |

|---|---|---|---|

| nls.multstart | R | Automated multiple starting value selection for NLS | Fitting pharmacokinetic models (e.g., Hill function) to metabolite data [24] |

| gslnls | R | Robust NLS solving with advanced trust-region methods | Handling difficult problems like Hobbs' weed infestation model [22] [25] |

| MultiStart | MATLAB | Global optimization wrapper for local solvers | Fitting multi-parameter models to biological data with multiple local minima [20] |

| lsqnonlin | MATLAB | Local NLS solver with bound constraints | Core solver for parameter estimation in differential equation models [21] |

| minpack.lm | R | Levenberg-Marquardt implementation | Provides the underlying solver for nls.multstart [24] |

| Methyl Belinostat-d5 | Methyl Belinostat-d5, MF:C16H16N2O4S, MW:337.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Ecopipam-d4 | Ecopipam-d4 Stable Isotope | Ecopipam-d4 is a deuterium-labeled internal standard for precise LC-MS/MS quantification in pharmacokinetic and metabolic research. For Research Use Only. | Bench Chemicals |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my standard NLS fitting sometimes fail to converge or produce unrealistic parameters?

This is a common issue when the objective function has multiple local minima or when parameters are highly correlated [19]. Standard NLS solvers are local optimizers that converge to the nearest minimum from the starting point. If your initial guess is in the basin of attraction of a local minimum, the solver cannot escape. Furthermore, in models with correlated parameters, the error surface can contain long, narrow "valleys" where the solver may experience parameter evaporation (parameters diverging to infinity) [22] [25]. The ms-nlLSQ approach mitigates this by systematically exploring the parameter space from multiple starting locations.

Q2: How many starting points should I use in my ms-nlLSQ analysis?

There is no universal answer, as the required number depends on the complexity of your model and the ruggedness of the objective function [19]. As a general guideline, start with at least 50-100 well-spread starting points for models with 3-5 parameters [20]. For more complex models, you may need hundreds or thousands of starts. The goal is to sufficiently cover the parameter space so that the same best solution is found repeatedly from different initial points. Some implementations, like gsl_nls, can dynamically update parameter ranges during the multistart process, which can improve efficiency [22].

Q3: What is the difference between ms-nlLSQ and stochastic methods like Genetic Algorithms?

Ms-nlLSQ is a deterministic approach that uses traditional local NLS solvers from multiple starting points [2]. In contrast, Genetic Algorithms (GAs) and other metaheuristics are stochastic and mimic principles of biological evolution like mutation and selection [19]. While GAs are less likely to be trapped in local minima, they can have difficulty precisely resolving the absolute minimum due to their stochastic nature and typically require many more function evaluations [19]. Ms-nlLSQ often provides a good balance between global exploration and precise local convergence, especially when paired with robust local solvers like Levenberg-Marquardt.

Q4: My ms-nlLSQ runs are yielding different "best" solutions. What does this indicate?

If different runs with the same settings produce different "best" solutions, this suggests that your objective function may have multiple distinct local minima with similar goodness-of-fit values [19]. This can occur when:

- Your data is insufficient to uniquely identify all parameters (identifiability issues).

- Parameters are highly correlated.

- The model is overly complex for the available data.

You should investigate the different solutions to see if they produce similar model predictions despite different parameter values. If so, you may need to simplify the model, collect more informative data, or use regularization techniques. Profiling the likelihood surface can help assess parameter identifiability [23].

Q5: How can I generate effective starting points for the multistart process?

Several strategies exist for generating starting points:

- Uniform random sampling within plausible parameter bounds.

- Latin Hypercube sampling for better space-filling properties.

- Grid search over a defined range (feasible only for low-dimensional problems).

- Using solutions from simplified models as starting points for more complex models.

- Leveraging

selfStartmodels in R, which contain initialization functions to automatically compute reasonable starting values from the data [22].

Many modern ms-nlLSQ implementations, such as nls_multstart and gsl_nls, can automatically generate and manage starting points for you [24] [22].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Solver Failures Due to Parameter Evaporation

Symptoms: The optimization fails with errors like "singular gradient" or parameters running away to extremely large values [22] [25].

Solutions:

- Implement parameter bounds: Constrain parameters to physiologically or mathematically plausible ranges using

lbandubarguments inlsqnonlinor thelowerandupperarguments in R functions [21] [24]. - Use a more robust algorithm: Switch from Gauss-Newton to Levenberg-Marquardt, which combines gradient descent and Gauss-Newton directions for better stability [22] [25].

- Reparameterize the model: Transform parameters to a different scale (e.g., use log-scale for parameters that span several orders of magnitude) to improve conditioning [24].

- Try a different solver: The GSL solvers in the

gslnlspackage offer advanced trust-region methods with geodesic acceleration that can handle difficult problems [25].

Problem: Excessive Computation Time

Symptoms: The ms-nlLSQ analysis takes impractically long to complete.

Solutions:

- Reduce the number of starts: Begin with a smaller set of starts (e.g., 50) to get an initial solution, then increase if necessary.

- Use parallel processing: Many ms-nlLSQ implementations support parallel computation. For example, MATLAB's

MultiStartcan useparforloops, and R packages likenls.multstartcan leverage parallel backends [20]. - Simplify the model: Consider whether all parameters are necessary, or if some can be fixed based on prior knowledge.

- Improve initial guesses: Use exploratory data analysis or simplified models to inform better starting points, reducing the number of iterations needed.

Problem: Poor Fit Despite Multiple Starts

Symptoms: Even the best solution from ms-nlLSQ shows significant systematic deviations from the data.

Solutions:

- Re-evaluate the model structure: The model itself might be inadequate to describe the biological system. Consider alternative mechanistic formulations.

- Check for data quality issues: Identify and potentially remove outliers that might be distorting the fit.

- Increase parameter bounds: Your global minimum might lie outside the currently searched parameter space.

- Consider weighted least squares: If measurement errors are heteroscedastic, implement weights to prevent high-variance data points from disproportionately influencing the fit [23].

Advanced Applications in Computational Systems Biology

Relationship to Other Optimization Methodologies

Ms-nlLSQ represents one of three main optimization strategies successfully applied in computational systems biology, alongside stochastic methods like Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) and heuristic nature-inspired methods like Genetic Algorithms (GAs) [2]. The following diagram illustrates how these methodologies relate within the optimization landscape for biological applications.

Case Study: Pharmacokinetic Modeling in Drug Development

In pharmacokinetic modeling, such as estimating parameters for the Hill function or extended Tofts model, ms-nlLSQ has proven particularly valuable [24] [26]. These models often contain parameters that are difficult to identify from data alone and may have correlated parameters that create multiple local minima in the objective function. For example, when fitting parent fraction data from PET pharmacokinetic studies, using nls.multstart with the Hill function provides more reliable parameter estimates than single-start methods, leading to more accurate predictions of drug metabolism and distribution [24].

The ms-nlLSQ approach is especially crucial when moving from individual curve fitting to population modeling, where consistency in finding global minima across multiple subjects is essential for valid statistical inference and biological interpretation.

Markov Chain Monte Carlo (rw-MCMC) for Stochastic Model Calibration

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General MCMC Concepts

What is MCMC and why is it used for calibrating stochastic models in systems biology?

Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) is a class of algorithms used to draw samples from probability distributions that are difficult to characterize analytically. In the context of stochastic model calibration in computational systems biology, MCMC is particularly valuable because it allows researchers to estimate posterior distributions of model parameters without knowing all the distribution's mathematical properties. MCMC works by creating a Markov chain of parameter samples, where each new sample depends only on the previous one, and whose equilibrium distribution matches the target posterior distribution. This is especially useful for Bayesian inference with complex biological models, where posterior distributions are often intractable via direct analytical methods. The "Monte Carlo" aspect refers to the use of random sampling to estimate properties of the distribution, while "Markov Chain" indicates the sequential sampling process where each sample serves as a stepping stone to the next [27] [28].

When should I use Random Walk MCMC (rw-MCMC) versus other optimization methods?

rw-MCMC is particularly suited for problems where the objective function is non-convex, involves stochastic equations or simulations, or when you need to characterize the full posterior distribution rather than just find a point estimate. It supports both continuous and non-continuous objective functions. In contrast, multi-start non-linear least squares methods (ms-nlLSQ) are more appropriate when both model parameters and the objective function are continuous, while Genetic Algorithms are better suited for problems involving discrete parameters or when dealing with complex, multi-modal parameter spaces. The choice depends on your specific problem characteristics, including parameter types, model structure, and whether you need full distributional information or just optimal parameter values [2].

Implementation Questions

How do I set the target acceptance rate for my RW sampler?

The target acceptance rate is a crucial parameter for controlling the efficiency of Random Walk MCMC. While the optimal acceptance rate can vary depending on the specific problem and dimension of the parameter space, a common default target is 0.44 for certain implementations. However, you may want to experiment with different values, such as 0.234, to examine the effect on estimation results. In some software frameworks, this may require creating a custom sampler if the target rate is hard-coded in the standard implementation [29].

When should I use log-scale sampling versus reflective sampling in RW-MCMC?

Use log=TRUE when your parameter domain is strictly positive (such as variance or standard deviation parameters) and has non-trivial posterior density near zero. This transformation expands the unit interval [0,1] to the entire space of negative reals, effectively removing the lower boundary and often improving sampling efficiency. Use reflective=TRUE when your parameter domain is bounded on an interval (such as probabilities bounded in [0,1]) with non-trivial posterior density near the boundaries. This makes proposals "reflect" off boundaries rather than proposing invalid values outside the parameter space [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnosing MCMC Convergence Issues

Problem: Poor mixing or convergence as indicated by low Effective Sample Size (ESS)

Diagnosis:

- ESS values below 200 (shown in red in tools like Tracer) indicate insufficient independent samples [30]

- Trace plots show high autocorrelation with a "blocky" or "skyline" appearance [30]

- Parameter values change slowly and inefficiently explore the posterior distribution

Solutions:

- Increase number of generations: Run MCMC for more iterations [30]

- Adjust proposal distribution: Tune the scale of random perturbations in the RW algorithm

- Modify adaptFactorExponent: Values closer to 0.5 make adaptation attenuate slowly, while values closer to 1 (like 0.8) make it stabilize quickly [29]

- Reparameterize model: Transform parameters to improve geometry of posterior distribution

- Use block sampling: Sample correlated parameters jointly rather than individually [31]

Problem: MCMC chain fails to reach stationarity

Diagnosis:

- Trace shows clear directional trend rather than random fluctuation around a mean [30]

- Starting values appear unreasonable relative to the stabilized distribution

- Different chains started from different points fail to converge to same distribution

Solutions:

- Adjust starting values: Choose initial values more plausible under the posterior

- Extend burn-in period: Discard more initial samples before assessing convergence

- Check prior specifications: Ensure priors are not unduly influencing or constraining posterior

- Verify model identifiability: Check that parameters are structurally identifiable from the data [32]

Addressing Performance and Efficiency Problems

Problem: Slow computation or excessive memory usage

Diagnosis:

- MCMC runs take impractically long time for reasonable number of iterations

- Memory constraints limit chain length or number of parameters

- Proposals are frequently rejected, wasting computational effort

Solutions:

- Optimize likelihood calculations: Profile code to identify computational bottlenecks

- Use adaptive MCMC: Implement algorithms that tune proposal distributions during sampling

- Reduce model complexity: Simplify model structure where scientifically justified

- Parallelize chains: Run multiple chains simultaneously rather than one long chain

- Implement thinning: Save only every k-th sample to reduce storage requirements

Problem: Biased sampling or inaccurate posterior approximation

Diagnosis:

- Posterior summaries change substantially with different random seeds

- Important regions of parameter space are poorly explored

- Multi-modal distributions are inadequately sampled

Solutions:

- Multiple chains: Run several independent chains from dispersed starting values

- Specialized samplers: Use algorithms designed for multi-modal distributions

- Parameter transformations: Improve geometry of parameter space for more efficient exploration

- Diagnostic checks: Compare posterior predictions with empirical data [32]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for rw-MCMC Implementation

| Tool/Category | Function | Example Applications/Options |

|---|---|---|

| Sampling Algorithms | Generate parameter samples from posterior distribution | Random Walk Metropolis, Metropolis-Hastings, Hamiltonian Monte Carlo [28] |

| Diagnostic Software | Assess convergence and sampling quality | Tracer (for ESS, trace plots), R/coda package [30] |

| Proposal Distributions | Generate new parameter proposals in RW chain | Normal distribution, Multivariate Normal for block sampling [27] |

| Transformation Methods | Improve sampling efficiency through reparameterization | Log-transform for positive parameters, Logit for bounded parameters [29] |

| Adaptive Mechanisms | Automatically tune sampler parameters during runtime | Adaptive RW with scaling based on acceptance rate [29] |

MCMC Diagnostic Workflow

Table: Interpretation of Key MCMC Diagnostics

| Diagnostic | Target Value | Interpretation | Remedial Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effective Sample Size (ESS) | >200 per parameter [30] | Measures independent samples; low ESS indicates high autocorrelation | Increase iterations, improve parameterization, use block sampling |

| Acceptance Rate | 0.234-0.44 for RW [29] | Balance between exploration and exploitation; too high/low reduces efficiency | Scale proposal distribution, adjust adaptation parameters |

| Gelman-Rubin Diagnostic (R-hat) | <1.05 | Compares between-chain vs within-chain variance; high values indicate non-convergence | Run longer chains, improve starting values, check model identifiability |

| Trace Plot Inspection | Stationary, well-mixed [30] | Visual assessment of convergence and exploration | Various based on specific pattern observed |

| Autocorrelation Plot | Rapid decay to zero | Measures dependence between successive samples; slow decay indicates poor mixing | Increase thinning interval, improve proposal mechanism |

Advanced Configuration Guide

How to customize RW samplers for specific parameter types:

For strictly positive parameters (e.g., rate constants):

- Use

log=TRUEto sample on log scale - Prevents invalid proposals and improves efficiency near boundary [29]

- Use

For bounded parameters (e.g., probabilities between 0 and 1):

- Use

reflective=TRUEto handle boundaries - Proposals "reflect" off boundaries rather than being rejected [29]

- Use

For correlated parameters:

- Use block sampling instead of univariate sampling [31]

- Implement multivariate proposal distributions

- Significantly improves mixing for correlated parameters

Example implementation code structure for customized RW sampler:

While specific code depends on your software environment (e.g., NIMBLE, Stan, PyMC), the general approach for creating a custom RW sampler with modified target acceptance rate involves:

- Copying the existing RW sampler code

- Modifying the target acceptance rate parameter (e.g., from 0.44 to 0.234)

- Registering the custom sampler with your MCMC framework

- Assigning the custom sampler to relevant parameters [29]

Integrating rw-MCMC with profile likelihood methods:

For models with many parameters, consider combining rw-MCMC with profile likelihood approaches:

- Use MCMC for full posterior exploration

- Employ profile likelihood for practical identifiability analysis [32]

- This hybrid approach provides both Bayesian and frequentist perspectives on parameter uncertainty

Genetic Algorithms (GA) and Evolutionary Strategies for Biomarker Identification

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the main advantages of using Genetic Algorithms for biomarker selection compared to traditional statistical methods?

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) offer several key advantages for identifying biomarkers from high-dimensional biological data. They are particularly effective for problems where the number of features (e.g., genes, proteins) vastly exceeds the number of samples (the "p >> n" problem), a common scenario in omics studies [33]. Unlike univariate statistical methods that assess features individually, GAs can identify multivariate biomarker panels—combinations of features that together have superior predictive power [34]. As heuristic global optimization methods, GAs are less likely to become trapped in local optima compared to some local search algorithms, enabling a more effective exploration of the vast solution space of possible biomarker combinations [2].

FAQ 2: My GA for biomarker selection is converging too quickly and yielding suboptimal panels. How can I improve its performance?

Premature convergence is often a sign of insufficient population diversity or high selection pressure. You can address this by:

- Adjusting Genetic Operator Rates: Increase the probability of mutation to introduce more diversity and prevent the dominance of a single solution early in the process [2].

- Using Hybrid Approaches: A highly effective strategy is to use a filter method first to reduce the feature space. For instance, combine the minimal Redundancy Maximum Relevance (mRMR) ensemble to select a top subset of genes, and then use a GA to refine the selection. This mRMRe-GA hybrid has been shown to enhance classification accuracy while using fewer genes [35].

- Reviewing Fitness Function: Ensure your fitness function (or objective function) accurately reflects the clinical or biological goal, such as maximizing classification accuracy while penalizing overly complex models [2].

FAQ 3: How can I handle the computational complexity of GAs when working with large-scale genomic datasets?

The computational cost of GAs is a recognized challenge, especially with large datasets [12]. Mitigation strategies include:

- Dimensionality Reduction: As in the mRMRe-GA approach, first use a fast filter method to select a manageable subset of a few hundred top candidate features before applying the GA [35].

- Parallelization: GAs are inherently parallelizable. You can distribute the evaluation of individual chromosomes or entire populations across multiple processors or high-performance computing (HPC) nodes to significantly reduce computation time [36].

- Efficient Fitness Evaluation: Optimize the code for your fitness function, as this is the most computationally intensive part of the algorithm. Using efficient classifiers like Support Vector Machines (SVM) within the fitness evaluation can also help [35].

FAQ 4: What are the best practices for validating a biomarker panel discovered using a GA?

Validation is essential to ensure that a biomarker is robust and fit-for-purpose [34]. The process must be rigorous and independent.

- Phased Validation: Follow a phased approach. After discovery in your initial training set, validate the panel's performance on a separate, held-out test set from the same study [37].

- External Validation: The most critical step is external validation, which tests the biomarker panel on a completely independent patient cohort and potentially different laboratories to assess generalizability [37].

- Analytical Validation: Ensure the biomarker can be reliably detected using the intended clinical platform (e.g., PCR-based assays) [37].

- Benchmarking: Compare the performance of your GA-derived panel against biomarkers identified by traditional methods and established clinical variables to demonstrate added value [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Classification Performance of the Selected Biomarker Panel

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Data Quality and Preprocessing Issues. Raw biomedical data is often noisy and affected by technical biases. If these are not corrected, the GA may optimize for technical artifacts rather than biological signal [33].

- Solution: Implement a rigorous data preprocessing pipeline. This should include data type-specific quality control (e.g., using

arrayQualityMetricsfor microarray data), normalization, transformation, and filtering of uninformative features (e.g., those with near-zero variance) [33].

- Solution: Implement a rigorous data preprocessing pipeline. This should include data type-specific quality control (e.g., using

- Cause: Inadequate Fitness Function. The objective function used to drive the GA may be misaligned with the end goal.

- Cause: Overfitting to the Training Data. The algorithm may have memorized noise in the training data rather than learning generalizable patterns.

- Solution: Use internal validation techniques like cross-validation (e.g., Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation - LOOCV) within the GA workflow to evaluate the generalizability of candidate solutions [35]. Additionally, employ regularized machine learning models (e.g.,

glmnet) as the classifier within the GA to reduce overfitting [34].

- Solution: Use internal validation techniques like cross-validation (e.g., Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation - LOOCV) within the GA workflow to evaluate the generalizability of candidate solutions [35]. Additionally, employ regularized machine learning models (e.g.,

Problem 2: Inconsistent Results Between Algorithm Runs

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Stochastic Nature of GAs. Different random number seeds can lead to different final biomarker panels.

- Solution: Run the GA multiple times with different random seeds and analyze the stability of the results. Features that consistently appear in the top-performing panels across multiple runs are more likely to be robust biomarkers [2].

- Cause: Poorly Tuned Algorithm Parameters. The performance of a GA is sensitive to parameters like population size, crossover rate, and mutation rate.

- Solution: Perform a parameter sweep or use automated hyperparameter tuning to find a robust configuration for your specific dataset. The table below summarizes key parameters and their effects.