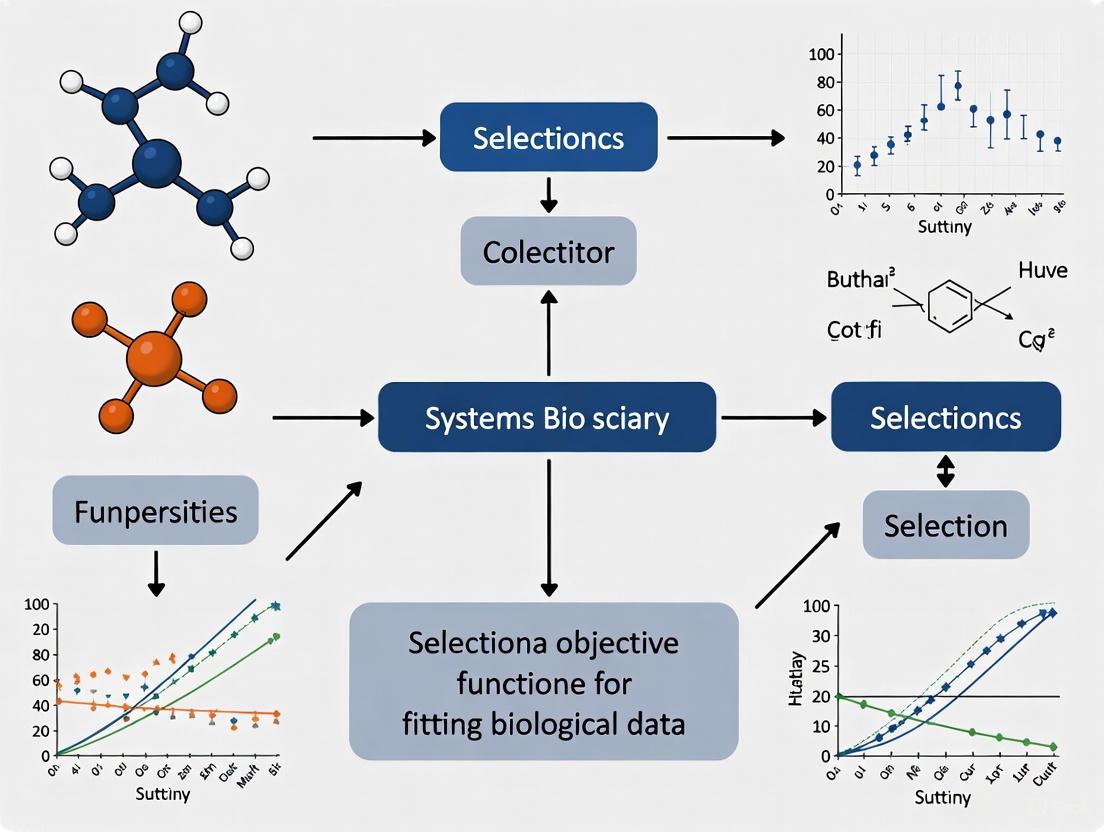

Objective Function Selection for Biological Data Fitting: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Selecting appropriate objective functions is a critical yet challenging step in fitting mathematical models to biological data, directly impacting parameter estimation accuracy, model predictive power, and ultimately, scientific and clinical...

Objective Function Selection for Biological Data Fitting: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

Selecting appropriate objective functions is a critical yet challenging step in fitting mathematical models to biological data, directly impacting parameter estimation accuracy, model predictive power, and ultimately, scientific and clinical decision-making. This comprehensive review addresses the foundational principles, methodological applications, troubleshooting strategies, and validation frameworks for objective function selection across diverse biological contexts—from gene regulatory networks and single-cell analysis to pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling and drug development. We synthesize current best practices for navigating common challenges including experimental noise, sparse temporal sampling, high-dimensional parameter spaces, and non-identifiability issues. By comparing traditional and emerging approaches through both theoretical and practical lenses, this article provides researchers and drug development professionals with a structured framework for optimizing objective function choice to enhance model reliability and biological insight across computational biology applications.

Understanding Objective Functions: Theoretical Foundations and Biological Contexts

Within biological research, the selection of an objective function is a critical step that directly influences the quality of parameter estimation and model evaluation. This article provides application notes and protocols for three fundamental objective functions—Least Squares, Log-Likelihood, and Chi-Square—framed within the context of biological data fitting. We detail their theoretical underpinnings, provide comparative analysis, and offer structured guidelines for their implementation in typical biological research scenarios, such as computational biology, system biology modeling, and the analysis of categorical data. The content is designed to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the knowledge to make informed decisions in optimizing their data fitting procedures.

In the domain of biological data fitting, an objective function (also referred to as a goodness-of-fit function or a cost function) serves as a mathematical measure of the discrepancy between a model's predictions and observed experimental data [1]. The process of parameter estimation involves adjusting model parameters to minimize this discrepancy, a procedure formally known as optimization. The choice of objective function is paramount, as it dictates the landscape of the optimization problem and can significantly impact the identifiability of parameters, the convergence speed of algorithms, and the biological interpretability of the results [1].

The three methods discussed herein—Least Squares, Log-Likelihood, and Chi-Square—form the cornerstone of statistical inference for many biological applications. Least Squares is a versatile method for fitting models to continuous data. Log-Likelihood provides a foundation for probabilistic model comparison and parameter estimation, particularly for models that are complex and simulation-based. The Chi-Square test is a robust, distribution-free statistic ideal for analyzing categorical data, such as genotype counts or disease incidence across treatment groups [2] [3]. This article will dissect these functions, providing a structured comparison and practical protocols for their application.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the three objective functions in biological contexts.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of Least Squares, Log-Likelihood, and Chi-Square objective functions.

| Feature | Least Squares | Log-Likelihood | Chi-Square |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Minimizes the sum of squared residuals between observed and predicted values [4]. | Maximizes the likelihood (or log-likelihood) that the observed data was generated by the model with given parameters [5]. | Evaluates the sum of squared differences between observed and expected counts, normalized by the expected counts [6] [2]. |

| Primary Application | Regression analysis, fitting continuous data (e.g., protein concentration time courses) [1]. | Parameter estimation and model selection for probabilistic models, including complex simulators [7] [1]. | Goodness-of-fit testing for categorical data (e.g., genetic crosses, contingency tables) [2] [3]. |

| Data Requirements | Continuous dependent variables. | Can handle both discrete and continuous data, depending on the assumed probability distribution. | Frequencies or counts of cases in mutually exclusive categories [3]. |

| Key Advantages | Simple to understand and apply; computationally efficient [4]. | Principled foundation for inference; allows for model comparison via AIC/BIC; can handle simulator-based models where likelihoods are intractable [7]. | Robust to data distribution; provides detailed information on which categories contribute to differences [3]. |

| Key Limitations | Sensitive to outliers; assumes errors are normally distributed for statistical tests. | Can be computationally expensive for complex models; may require simulation-based estimation (e.g., IBS) for intractable likelihoods [7]. | Requires a sufficient sample size (expected frequency ≥5 in most cells) [3]. |

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol 1: Parameter Estimation using Least Squares Regression

Principle: This protocol is used to fit a model (e.g., a straight line or a system of ODEs) to continuous biological data by minimizing the sum of squared differences between observed data points and model predictions [4] [1].

Materials:

- Software: MATLAB (with

lsqnonlin), R (withnlsorlm), or Python (withscipy.optimize.least_squares). - Data: A dataset of continuous measurements (e.g., metabolite concentrations over time).

Procedure:

- Formulate the Model: Define your mathematical model,

y = f(x, θ), whereθis the vector of parameters to be estimated. - Define the Residuals: For each data point

i, compute the residual,r_i = y_observed,i - f(x_i, θ). - Construct the Objective Function: The Least Squares objective is the sum of squared residuals:

S(θ) = Σ (r_i)^2[4]. - Optimize: Use an optimization algorithm (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt) to find the parameter values

θthat minimizeS(θ). - Address Data Scaling: For relative data (e.g., Western blot densities in arbitrary units), choose a scaling method.

- Scaling Factor (SF) Approach: Introduce a scaling parameter

αfor each observable, so the fit becomesỹ ≈ α * y(θ). Estimateαsimultaneously withθ[1]. - Data-Driven Normalization of Simulations (DNS) Approach: Normalize both the experimental data and model simulations in the same way (e.g., to a control or maximum value). This avoids introducing new parameters and can improve identifiability and convergence speed [1].

- Scaling Factor (SF) Approach: Introduce a scaling parameter

Visualization of the Least Squares Workflow:

Protocol 2: Model Fitting via Maximum Log-Likelihood Estimation

Principle: This protocol finds the parameter values that maximize the probability (likelihood) of observing the experimental data under the model. For practical purposes, the log-likelihood is maximized (or the negative log-likelihood is minimized) [5].

Materials:

- Software: R, Python, or specialized tools like PEPSSBI for DNS [1].

- Data: Can be diverse: trial-by-trial behavioral responses, discrete counts, or continuous measurements.

Procedure:

- Define the Likelihood Function: Assume a probability distribution for the data (e.g., Normal for continuous, Binomial for success/failure). The likelihood

L(θ)for all data points is the product of the individual probabilities. - Compute Log-Likelihood: Convert the product to a sum by taking the natural logarithm:

LL(θ) = Σ log(Probability(Data_i | θ)). - Optimize: Use an optimization algorithm to find the parameters

θthat maximizeLL(θ). - Handle Intractable Likelihoods with Simulation: For complex simulator-based models where the likelihood cannot be calculated directly, use a sampling method.

- Inverse Binomial Sampling (IBS): For each observation, run the simulator until a matching output is generated. The number of samples required provides an unbiased estimate of the log-likelihood. This is particularly useful in computational neuroscience and cognitive science [7].

Visualization of the Maximum Likelihood Workflow:

Protocol 3: Goodness-of-Fit Testing with Pearson's Chi-Square

Principle: This protocol tests whether the observed distribution of a categorical variable differs significantly from an expected (theoretical) distribution [2] [3]. It is widely used in genetics and epidemiology.

Materials:

- Software: Any statistical software (R, SPSS, Excel) with Chi-square test functionality.

- Data: Frequency counts of observations falling into mutually exclusive categories.

Procedure:

- State Hypotheses:

- Null Hypothesis (H₀): The population follows the specified distribution.

- Alternative Hypothesis (Hₐ): The population does not follow the specified distribution [2].

- Create a Contingency Table: Tabulate the observed counts (

O) for each category. - Calculate Expected Counts: Compute expected counts (

E) for each category based on the theoretical distribution (e.g., a 1:1 sex ratio, or independence between variables) [3]. For a contingency table,Efor a cell = (Row Total × Column Total) / Grand Total. - Compute the Chi-Square Statistic: Apply the formula:

χ² = Σ [ (O - E)² / E ][6] [2] [3]. - Determine Significance: Compare the calculated

χ²to a critical value from the Chi-square distribution with the appropriate degrees of freedom (df = number of categories - 1for goodness-of-fit). Ifχ²exceeds the critical value, reject the null hypothesis [2].

Visualization of the Chi-Square Testing Workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential computational tools and their functions in objective function-based analysis.

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Optimization Algorithms (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt, Genetic Algorithms) | Iteratively searches parameter space to find the values that minimize (or maximize) the objective function [1]. |

| Sensitivity Equations (SE) | A computational method that efficiently calculates the gradient of the objective function, speeding up gradient-based optimization [1]. |

| Inverse Binomial Sampling (IBS) | A simulation-based method to obtain unbiased estimates of log-likelihood for complex models where the likelihood is intractable [7]. |

| Data Normalization Scripts (for DNS) | Custom code (e.g., in Python/R) to apply the same normalization to both experimental data and model outputs, facilitating direct comparison without scaling parameters [1]. |

| Chi-Square Critical Value Table | A reference table used to determine the statistical significance of the calculated Chi-square statistic based on degrees of freedom and significance level (α) [2]. |

The strategic selection of an objective function is a critical decision in biological data fitting that extends beyond mere mathematical convenience. Least Squares remains a powerful and intuitive tool for fitting continuous data. The Log-Likelihood framework offers a statistically rigorous approach for model selection and is adaptable to complex, stochastic models via simulation-based methods like IBS. The Chi-Square test provides a robust, non-parametric solution for analyzing categorical data. By aligning the properties of these objective functions—summarized in this article's protocols and tables—with the specific characteristics of their biological data and research questions, scientists can enhance the reliability, interpretability, and predictive power of their computational models.

The Role of Objective Functions in Parameter Estimation for Biological Systems

Mathematical models, particularly those based on ordinary differential equations (ODEs), are fundamental tools in systems biology for quantitatively understanding complex biological processes such as cellular signaling pathways. These models describe how biological system states evolve over time according to the relationship ( \frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}t}x = f(x,\theta) ), where ( x ) represents the state vector and ( \theta ) denotes the kinetic parameters. A critical challenge in developing these models lies in determining the unknown parameter values ( \theta ), which are often not directly measurable experimentally. Parameter estimation addresses this challenge by indirectly inferring parameter values from experimental measurement data, formulating it as an optimization problem that minimizes an objective function (or goodness-of-fit function) quantifying the discrepancy between experimental observations and model simulations.

The selection of an appropriate objective function is paramount, as it directly influences the accuracy, reliability, and practical identifiability of the estimated parameters. The objective function defines the landscape that optimization algorithms navigate, and an ill-chosen function can lead to convergence to local minima, increased computational time, or failure to identify biologically plausible parameter sets. This article examines the types, properties, and practical applications of objective functions for parameter estimation in biological systems, providing structured protocols and resources to guide researchers in making informed selections for their specific modeling contexts.

Types of Objective Functions and Their Formulations

Quantitative Data-Based Objective Functions

When working with quantitative numerical data, such as time-course measurements or dose-response curves, several standard objective functions are commonly employed. The choice among them often depends on the nature of the available data and the error structure.

Least Squares (LS): This fundamental approach minimizes the simple sum of squared differences between experimental data points ( \tilde{y}i ) and model simulations ( yi(\theta) ). Its formulation is ( f{\text{LS}}(\theta) = \sumi (\tilde{y}i - yi(\theta))^2 ) [1]. It is most appropriate when measurement errors are independent and identically distributed, but may perform poorly with heterogeneous variance across data points.

Chi-Squared (( \chi^2 )): This method extends least squares by incorporating weighting factors, typically the inverse of the variance ( \sigmai^2 ) associated with each data point. The objective function is ( f{\chi^2}(\theta) = \sumi \omegai (\tilde{y}i - yi(\theta))^2 ), where ( \omegai = 1/\sigmai^2 ) [8]. It is statistically more rigorous than LS when reliable estimates of measurement variance are available, as it gives less weight to more uncertain data points.

Log-Likelihood (LL): For a fully probabilistic approach, the log-likelihood function can be used. For data assumed to be normally distributed, maximizing the log-likelihood is equivalent to minimizing a scaled version of the chi-squared function. It provides a foundation for rigorous statistical inference, including uncertainty quantification [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Standard Objective Functions for Quantitative Data

| Objective Function | Mathematical Formulation | Key Assumptions | Primary Use Cases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Least Squares (LS) | ( f{\text{LS}}(\theta) = \sumi (\tilde{y}i - yi(\theta))^2 ) | Homoscedastic measurement errors | Initial fitting; simple models with uniform error | |

| Chi-Squared (( \chi^2 )) | ( f{\chi^2}(\theta) = \sumi \frac{(\tilde{y}i - yi(\theta))^2}{\sigma_i^2} ) | Known or estimable measurement variances ( \sigma_i^2 ) | Data with heterogeneous quality or known error structure | |

| Log-Likelihood (LL) | ( f_{\text{LL}}(\theta) = -\log \mathcal{L}(\theta | \tilde{y}) ) | Specified probability distribution for data (e.g., Normal) | Probabilistic modeling; rigorous uncertainty quantification |

Incorporating Qualitative Data via Inequality Constraints

A significant advancement in biological parameter estimation is the formal integration of qualitative data (e.g., categorical phenotypes, viability outcomes, or directional trends) alongside quantitative measurements. This is particularly valuable when quantitative data are sparse, but rich qualitative observations are available, such as knowledge that a protein concentration increases under a treatment or that a specific genetic mutant is non-viable [9].

The method converts qualitative observations into inequality constraints on model outputs. For example, the knowledge that the simulated output ( yj(\theta) ) should be greater than a reference value ( y{\text{ref}} ) can be formulated as the constraint ( gj(\theta) = y{\text{ref}} - y_j(\theta) < 0 ). A static penalty function is then used to incorporate these constraints into the overall objective function:

[ f{\text{qual}}(\theta) = \sumj Cj \cdot \max(0, gj(\theta)) ]

Here, ( C_j ) is a problem-specific constant that determines the penalty strength for violating the ( j )-th constraint. The total objective function to be minimized becomes a composite of the quantitative and qualitative components:

[ f{\text{tot}}(\theta) = f{\text{quant}}(\theta) + f_{\text{qual}}(\theta) ]

where ( f_{\text{quant}}(\theta) ) can be any of the standard functions like LS or ( \chi^2 ) [9]. This approach allows automated parameter identification procedures to leverage a much broader range of experimental evidence, significantly improving parameter identifiability and model credibility.

Scaling and Normalization Strategies for Data Alignment

A critical practical issue in parameter estimation is aligning the scales of model simulations and experimental data. Experimental data from techniques like western blotting or RT-qPCR are often in arbitrary units (a.u.), while models may simulate molar concentrations or dimensionless quantities. Two primary approaches address this:

Scaling Factor (SF) Approach: This method introduces unknown scaling factors ( \alphaj ) that multiplicatively relate simulations to data: ( \tilde{y}i \approx \alphaj yi(\theta) ). These ( \alpha_j ) parameters must then be estimated simultaneously with the kinetic parameters ( \theta ) [1]. While commonly used, a key drawback is that it increases the number of parameters to be estimated, which can aggravate practical non-identifiability—the existence of multiple parameter combinations that fit the data equally well.

Data-Driven Normalization of Simulations (DNS) Approach: This strategy applies the same normalization to model simulations as was applied to the experimental data. For instance, if data are normalized to a reference point ( \tilde{y}i = \hat{y}i / \hat{y}{\text{ref}} ), simulations are normalized identically: ( \tilde{y}i \approx yi(\theta) / y{\text{ref}}(\theta) ) [1]. The primary advantage of DNS is that it does not introduce new parameters. Evidence shows that DNS can improve optimization convergence speed and reduce non-identifiability compared to the SF approach, especially for models with a large number of unknown parameters [1].

Scaling and Normalization Workflow for aligning model simulations with experimental data.

Practical Protocols for Objective Function Implementation

Protocol 1: Formulating the Objective Function for a New Model

This protocol guides the initial setup of a parameter estimation problem for a biological model.

- Define the Output Function: Specify the function ( y = g(x) ) that maps the model's internal state variables ( x ) to the observables ( \tilde{y} ) for which experimental data exist [1].

- Select the Core Objective Function: Choose a base function ( f_{\text{quant}}(\theta) ) based on your data characteristics. Use Least Squares for a simple, initial approach. Prefer Chi-Squared if reliable estimates of measurement error variance are available.

- Choose a Scaling Strategy: Decide between SF and DNS. For models with many parameters or when facing identifiability issues, prefer DNS to avoid increasing parameter count. The software PEPSSBI provides support for DNS [1].

- Incorporating Qualitative Data: List all qualitative biological observations. For each, formulate a corresponding inequality constraint ( gj(\theta) < 0 ). Choose penalty constants ( Cj ) (often starting with a value of 1) and construct the penalty function ( f{\text{qual}}(\theta) ). The total objective function is then ( f{\text{tot}}(\theta) = f{\text{quant}}(\theta) + f{\text{qual}}(\theta) ) [9].

Protocol 2: Selecting and Applying an Optimization Algorithm

The choice of optimization algorithm is intertwined with the selected objective function.

- Gradient-Based Algorithms (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt): These are efficient and often the fastest choice for problems where gradients can be computed. They are well-suited for standard least-squares problems [8]. The gradient can be calculated via:

- Finite Differences (FD): Simple but potentially inefficient and inaccurate for high-dimensional problems.

- Sensitivity Equations (SE): Provides exact gradients by solving an augmented ODE system. Efficient for models with moderate numbers of parameters and equations [1] [8].

- Adjoint Sensitivity Analysis: More complex to implement but highly efficient for models with very large numbers of parameters, as the computational cost is largely independent of the parameter count [8].

- Metaheuristic/Global Optimization Algorithms (e.g., Genetic Algorithms, Differential Evolution, GLSDC): These methods do not require gradient information and are better at escaping local minima. They are recommended for complex, non-convex objective functions, such as those incorporating qualitative constraints, or when little prior knowledge of parameter values exists [1] [8] [9].

- Implementation with Multistart: Regardless of the algorithm, perform multistart optimization (multiple independent runs from random initial parameter values) to mitigate the risk of converging to a local minimum [8]. Benchmarking suggests that for large-scale problems, hybrid stochastic-deterministic methods like GLSDC can outperform local gradient-based methods [1].

Optimization Algorithm Selection Logic based on problem characteristics.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Multi-Sample and Multi-Omics Network Inference

Emerging frameworks like CORNETO (Constrained Optimization for the Recovery of Networks from Omics) generalize network inference from prior knowledge and multi-omics data as a unified optimization problem. CORNETO uses structured sparsity and network flow constraints within its objective function to jointly infer context-specific biological networks across multiple samples (e.g., different conditions, time points). This allows for the identification of both shared and sample-specific molecular mechanisms, yielding sparser and more interpretable models than analyzing samples independently [10].

Uncertainty Quantification

After point estimation of parameters, it is crucial to quantify their uncertainty. The profile likelihood method is a powerful and computationally feasible approach for this task, providing confidence intervals for parameters and revealing practical identifiability—whether parameters are uniquely determined by the data [8] [9]. This analysis is essential for assessing the reliability of model predictions.

Table 2: Essential Software Tools for Parameter Estimation and Uncertainty Analysis

| Software Tool | Primary Function | Key Features Related to Objective Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Data2Dynamics [1] | Parameter estimation for dynamic models | Supports least-squares and likelihood-based objectives; advanced uncertainty analysis |

| PEPSSBI [1] | Parameter estimation | Provides specialized support for Data-Driven Normalization (DNS) |

| PyBioNetFit [8] [9] | General-purpose parameter estimation | Supports rule-based modeling; implements penalty functions for qualitative data constraints |

| AMICI/PESTO [8] | High-performance parameter estimation & UQ | Uses adjoint sensitivity for efficient gradient computation; profile likelihood for UQ |

| COPASI [8] | Biochemical simulation and analysis | Integrated environment with multiple optimization algorithms and objective functions |

| CORNETO [10] | Network inference from omics | Unified optimization framework for multi-sample, prior-knowledge-guided inference |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Resources for Parameter Estimation in Systems Biology

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Format | Role and Function in Parameter Estimation |

|---|---|---|

| Model Specification | Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) [8] | Standardized format for encoding models, ensuring compatibility with estimation tools like COPASI and AMICI. |

| Model Specification | BioNetGen Language (BNGL) [8] | Rule-based language for succinctly modeling complex site-graph dynamics in signaling networks. |

| Data & Model Repository | BioModels Database [8] | Curated repository of published models, useful for benchmarking new objective functions and methods. |

| Optimization Solvers | Levenberg-Marquardt [8] | Efficient gradient-based algorithm for nonlinear least-squares problems. |

| Optimization Solvers | Differential Evolution [9] | Robust metaheuristic algorithm effective for global optimization and handling non-smooth objective functions. |

| Uncertainty Analysis | Profile Likelihood [8] [9] | Method for assessing parameter identifiability and generating confidence intervals. |

In the field of biological data fitting research, the selection of an appropriate objective function is paramount. This choice is heavily influenced by the fundamental characteristics of the data itself, which is often plagued by three interconnected challenges: technical noise, data sparsity, and heteroscedasticity. Technical noise introduces non-biological fluctuations that obscure true signals, while sparsity results from missing values or limited sampling, particularly in single-cell technologies. Heteroscedasticity—the phenomenon where data variability is not constant across measurements—further complicates analysis by violating key assumptions of many statistical models. Together, these challenges can severely distort biological interpretation, leading to unreliable model parameters and misguided conclusions if not properly addressed through tailored objective functions and analytical frameworks.

The Nature of the Challenges

Technical noise in biological data arises from multiple sources throughout the experimental pipeline. In functional genomics approaches, this includes variation originating from sampling, sample work-up, and analytical errors [11]. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data suffers particularly from technical noise, often manifested as "dropout" events where gene expression measurements are recorded as zero despite the presence of actual biological signal [12] [13]. These dropouts occur due to several factors: (1) low amounts of mRNA in individual cells, (2) technical or sequencing artifacts, and (3) inherent cell type differences where some cells exhibit genuinely low expression levels for certain genes [13]. The problem is compounded by the fact that measurement techniques for biological data are generally less developed than those for electrical or mechanical systems, resulting in noisier measurements overall [14].

Data Sparsity in Biological Systems

Biological data sparsity manifests in two primary forms: limited experimental sampling and high-dimensional measurements with many missing values. Sparse temporal sampling—where inputs and outputs are sampled only a few times during an experiment, often unevenly spaced—is common when measuring biological quantities at the cellular level due to technical limitations and the labor involved in data collection [14]. In single-cell epigenomics, such as single-cell Hi-C data (scHi-C), sparsity appears as extremely sparse contact frequency matrices within chromosomes, requiring robust noise reduction strategies to enable meaningful cell annotation and significant interaction detection [12]. High-dimensional gene expression datasets present another sparsity challenge, where the number of genes (features) far exceeds the number of samples, making it difficult to identify the most biologically influential features [15].

Heteroscedasticity Across Biological Data Types

Heteroscedasticity represents a fundamental challenge in biological data analysis, where the variability of measurements is not constant but depends on the value of the measurements themselves. This phenomenon is frequently observed in pseudo-bulk single-cell RNA-seq datasets, where different experimental groups exhibit distinct variances [16]. For example, in studies of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), healthy controls consistently demonstrate lower variability than patient groups, while research on human macrophages from lung tissues shows even more pronounced heteroscedasticity across conditions [16]. In metabolomics data, heteroscedasticity occurs because the standard deviation resulting from uninduced biological variation depends on the average measurement value, introducing additional structure that complicates analysis [11]. This non-constant variance directly violates the homoscedasticity assumption underlying many conventional statistical methods, leading to biased results and inaccurate biological conclusions if unaddressed.

Table 1: Characteristics of Key Challenges in Biological Data Analysis

| Challenge | Primary Manifestations | Impact on Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Technical Noise | Dropout events in scRNA-seq; measurement artifacts; non-biological fluctuations | Obscures true biological signals; complicates cell type identification; distorts differential expression analysis |

| Data Sparsity | Limited temporal sampling; high-dimensional feature spaces; missing values in epigenetic data | Hampers trajectory inference; reduces statistical power; impedes detection of subtle biological variations |

| Heteroscedasticity | Group-specific variances in pseudo-bulk data; mean-variance dependence in metabolomics | Violates homoscedasticity assumptions; leads to poor error control; reduces power to detect differentially expressed genes |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Noise Reduction Frameworks

RECODE and iRECODE Platforms

The RECODE (resolution of the curse of dimensionality) algorithm represents a significant advancement in technical noise reduction for single-cell sequencing data. This method models technical noise—arising from the entire data generation process from lysis through sequencing—as a general probability distribution, including the negative binomial distribution, and reduces it using eigenvalue modification theory rooted in high-dimensional statistics [12]. The recently upgraded iRECODE framework extends this capability to simultaneously address both technical noise and batch effects while preserving full-dimensional data. The iRECODE workflow follows these key steps:

- Essential Space Mapping: Gene expression data is mapped to an essential space using noise variance-stabilizing normalization (NVSN) and singular value decomposition.

- Batch Correction Integration: Batch correction is implemented within this essential space using algorithms such as Harmony, minimizing decreases in accuracy and computational costs associated with high-dimensional calculations.

- Variance Modification: Principal-component variance modification and elimination are applied to reduce technical noise while preserving biological signals.

This integrated approach has demonstrated substantial improvements in batch noise correction, reducing relative errors in mean expression values from 11.1-14.3% to just 2.4-2.5% in benchmark tests [12]. The method has been successfully applied to diverse single-cell modalities beyond transcriptomics, including single-cell Hi-C for epigenomics and spatial transcriptomics data.

SmartImpute for Targeted Imputation

SmartImpute offers a targeted approach to address dropout events in scRNA-seq data by focusing imputation on a predefined set of biologically relevant marker genes. This framework employs a modified generative adversarial imputation network (GAIN) with a multi-task discriminator that distinguishes between true biological zeros and missing values [13]. The experimental protocol for implementing SmartImpute involves:

- Marker Gene Panel Selection: Begin with a core set of 580 well-established marker genes (such as the BD Rhapsody Immune Response Targeted Panel) and customize based on specific research objectives using the provided R package (https://github.com/wanglab1/tpGPT) that utilizes a generative pre-trained transformer model.

- Data Preparation: Identify the target gene panel within the gene expression data, incorporating a proportion of non-target genes to ensure robust model generalizability without losing dataset information.

- Model Training: Implement the modified GAIN architecture with a multi-task discriminator to impute missing values while preserving biological zeros, avoiding assumptions about underlying data distributions.

- Validation: Assess imputation quality through UMAP clustering, heatmap visualization of gene expression patterns, and downstream analyses such as cell type prediction accuracy.

When applied to head and neck squamous cell carcinoma data, SmartImpute demonstrated remarkable improvements in distinguishing closely related cell types (CD4 Tconv, CD8 exhausted T, and CD8 Tconv cells) while preserving biological distinctiveness between myocytes, fibroblasts, and myofibroblasts [13].

Addressing Heteroscedasticity

voomByGroup and voomQWB Methods

To address group heteroscedasticity in pseudo-bulk scRNA-seq data, two specialized methods have been developed: voomByGroup and voomWithQualityWeights using a blocked design (voomQWB). These approaches specifically account for unequal group variances that commonly occur in biological datasets [16]. The experimental protocol for implementing these methods includes:

- Heteroscedasticity Detection: Prior to analysis, assess dataset heteroscedasticity through (1) multi-dimensional scaling plots to visualize within-group variation, (2) calculation of common biological coefficient of variation across groups, and (3) examination of group-specific voom trends to identify differences in mean-variance relationships.

- Method Selection: Choose between voomByGroup for direct modeling of group-specific variances or voomQWB for assigning quality weights as "blocks" within groups.

- Parameter Specification: For voomQWB, specify sample group information via the var.group argument in the voomWithQualityWeights function to produce identical quality weights for samples within the same group.

- Performance Validation: Compare error control and detection power against standard methods that assume homoscedasticity using simulation studies and experimental datasets with known ground truths.

These methods have demonstrated superior performance in scenarios with unequal group variances, effectively controlling false discovery rates while maintaining detection power for differentially expressed genes [16].

Bayesian Optimization with Heteroscedastic Noise Modeling

For experimental optimization in biological systems, Bayesian optimization with heteroscedastic noise modeling provides a powerful framework for navigating high-dimensional design spaces with non-constant variability. The BioKernel implementation offers a no-code interface with specific capabilities for handling biological noise [17]. The protocol for applying this method involves:

- System Configuration: Select appropriate modular kernel architecture (e.g., Matern kernel with gamma noise prior) and acquisition function (Expected Improvement, Upper Confidence Bound, or Probability of Improvement) based on experimental goals.

- Noise Modeling: Enable heteroscedastic noise modeling to capture non-constant measurement uncertainty inherent in biological systems.

- Experimental Design: Utilize the acquisition function to sequentially select experimental conditions that balance exploration of uncertain regions with exploitation of known high-performing areas.

- Iterative Optimization: Conduct sequential experiments guided by the Bayesian optimization algorithm, updating the probabilistic model after each iteration.

This approach has demonstrated remarkable efficiency in biological applications, converging to optimal conditions in just 22% of the experimental points required by traditional grid search methods when applied to limonene production optimization in E. coli [17].

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Addressing Biological Data Challenges

| Method | Primary Application | Key Steps | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| iRECODE | Dual noise reduction in single-cell data | Essential space mapping; integrated batch correction; variance modification | Relative error in mean expression; integration scores (iLISI, cLISI); computational efficiency |

| SmartImpute | Targeted imputation in scRNA-seq | Marker gene panel selection; modified GAIN training; biological zero preservation | Cell type discrimination; cluster separation; prediction accuracy with SingleR |

| voomByGroup/voomQWB | Heteroscedasticity in pseudo-bulk data | Heteroscedasticity detection; group-specific variance modeling; quality weight assignment | False discovery rate control; power analysis; silhouette scores |

| Bayesian Optimization | Experimental design under noise | Kernel selection; acquisition function optimization; sequential experimentation | Convergence rate; resource efficiency; objective function improvement |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RECODE Platform | Comprehensive noise reduction for single-cell omics | Extensible to scRNA-seq, scHi-C, spatial transcriptomics; parameter-free operation |

| SmartImpute Framework | Targeted imputation for scRNA-seq data | GitHub: https://github.com/wanglab1/SmartImpute; customizable marker gene panels |

| voomByGroup/voomQWB | Differential expression with heteroscedasticity | Compatible with limma pipeline; handles group-specific variances in pseudo-bulk data |

| BioKernel | Bayesian optimization for biological experiments | No-code interface; modular kernel architecture; heteroscedastic noise modeling |

| Marionette-wild E. coli Strain | High-dimensional pathway optimization | Genomically integrated array of 12 orthogonal inducible transcription factors; enables 12-dimensional optimization |

| BD Rhapsody Immune Response Targeted Panel | Marker gene foundation for targeted imputation | Core set of 580 well-established marker genes; customizable for specific research needs |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Integrated Noise Reduction Workflow

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Noise Reduction Pipeline. This workflow illustrates the integrated approach for simultaneous technical noise reduction and batch effect correction in single-cell data analysis.

Bayesian Optimization for Biological Systems

Diagram 2: Bayesian Optimization Cycle. This diagram outlines the iterative process of model-based experimental optimization for biological systems with heteroscedastic noise.

The challenges of noise, sparsity, and heteroscedasticity in biological data necessitate sophisticated analytical approaches that directly inform objective function selection in biological data fitting research. As demonstrated through the methodologies and protocols outlined, successful navigation of these challenges requires domain-specific solutions that respect the unique characteristics of biological data generation systems. The integration of noise-aware statistical frameworks like iRECODE and voomByGroup, targeted computational approaches such as SmartImpute, and optimization strategies like heteroscedastic Bayesian optimization collectively provide a robust toolkit for researchers confronting these fundamental data challenges. By selecting and implementing these specialized objective functions and corresponding experimental protocols, researchers can extract more biologically meaningful insights from their data, ultimately advancing drug development and basic biological research in the face of increasingly complex and high-dimensional data landscapes.

The selection of an appropriate statistical framework is a critical step in biological data fitting research. The choice between Bayesian and Frequentist approaches fundamentally shapes how models are calibrated, how uncertainty is quantified, and how inferences are drawn from experimental data. While the Frequentist paradigm has long dominated many scientific fields, Bayesian methods have gained significant traction in biological domains such as epidemiology, ecology, and drug development, particularly for handling complex models with limited data. This article provides a comparative analysis of both philosophical foundations and practical implementations of these competing statistical frameworks, with specific application to biological data fitting challenges. We examine core philosophical differences, evaluate performance across biological case studies, and provide detailed protocols for implementing both approaches in practice, focusing on their applicability to objective function selection in biological research.

Philosophical Foundations and Interpretive Frameworks

At their core, Bayesian and Frequentist approaches represent fundamentally different interpretations of probability and its role in statistical inference (Table 1).

Table 1: Core Philosophical Differences Between Bayesian and Frequentist Approaches

| Aspect | Frequentist Approach | Bayesian Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Definition of Probability | Long-run frequency of events [18] [19] | Degree of belief or plausibility in a proposition [20] [19] |

| Treatment of Parameters | Fixed, unknown constants [19] | Random variables with probability distributions [21] [19] |

| Incorporation of Prior Knowledge | No formal mechanism for incorporating prior knowledge [19] | Explicitly incorporated via prior distributions [17] [19] |

| Uncertainty Intervals | Confidence Interval: If the data collection and CI calculation were repeated many times, 95% of such intervals would contain the true parameter [18] | Credible Interval: Given the observed data and prior, there is a 95% probability that the true parameter lies within this interval [18] |

| Hypothesis Testing | P-value: Probability of observing data as extreme as, or more extreme than, the actual data, assuming the null hypothesis is true [22] [19] | Bayes Factor: Ratio of the likelihood of the data under one hypothesis compared to another [22] |

The Frequentist interpretation views probability as the long-run frequency of events across repeated trials [18] [19]. Parameters are treated as fixed, unknown constants, and probability statements apply only to the data and the procedures used to estimate those parameters. A p-value, for instance, represents the probability of observing data as extreme as the current data, assuming the null hypothesis is true [22] [19]. Similarly, a 95% confidence interval indicates that if the same data collection and analysis procedure were repeated indefinitely, 95% of the calculated intervals would contain the true parameter value [18].

In contrast, the Bayesian framework interprets probability as a subjective degree of belief about propositions or parameters [20] [19]. Parameters are treated as random variables described by probability distributions. Bayesian inference formally incorporates prior knowledge or beliefs via prior distributions, which are updated with observed data through Bayes' theorem to produce posterior distributions [17] [19]. This allows for direct probability statements about parameters, such as "there is a 95% probability that the true value lies within this credible interval" [18].

These philosophical differences manifest in practical interpretations. As one analogy illustrates, when searching for a misplaced phone using a locator beep, a Frequentist would rely solely on the auditory signal to infer the phone's location, while a Bayesian would combine the beep with prior knowledge of common misplacement locations to guide the search [20].

Performance Comparison in Biological Applications

Recent comparative studies have evaluated the performance of Bayesian and Frequentist approaches across various biological modeling contexts, particularly in ecology and epidemiology. A comprehensive 2025 analysis compared both frameworks across three biological models using four datasets with standardized normal error structures to ensure fair comparison [23] [24].

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Biological Models [23] [24]

| Model & Data Context | Observation Scenario | Frequentist Performance | Bayesian Performance | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lotka-Volterra Predator-Prey (Hudson Bay data) | Both prey and predator observed | Excellent (MAE, MSE, PI coverage) | Good | Frequentist excels with rich, fully observed data |

| Lotka-Volterra Predator-Prey | Prey only or predator only | Good | Better | Bayesian superior with partial observability |

| Generalized Logistic (Lung injury, 2022 U.S. mpox) | Fully observed | Excellent (MAE, MSE) | Good | Frequentist performs best with well-observed settings |

| SEIUR Epidemic (COVID-19 Spain) | Partially observed latent states | Good | Excellent (Uncertainty quantification) | Bayesian excels with latent-state uncertainty and sparse data |

The analysis revealed that structural and practical identifiability significantly influences method performance [23] [24]. Frequentist inference demonstrated superior performance in well-observed settings with rich data, such as the generalized logistic model for lung injury and mpox outbreaks, and the Lotka-Volterra model when both predator and prey populations were observed [23] [24]. These scenarios typically feature high signal-to-noise ratios and minimal parameter correlations, allowing maximum likelihood estimation to converge efficiently to accurate point estimates.

Conversely, Bayesian inference outperformed in scenarios characterized by high latent-state uncertainty and sparse or partially observed data, as exemplified by the SEIUR model applied to COVID-19 transmission in Spain [23] [24]. In such contexts, the explicit incorporation of prior information and full probabilistic treatment of parameters enabled more robust parameter recovery and superior uncertainty quantification. For the Lotka-Volterra model under partial observability (where only prey or predator data was available), Bayesian methods also demonstrated advantages [23] [24].

Another comparative study on prostate cancer risk prediction using 33 genetic variants found that both approaches provided only marginal improvements in predictive performance when adding genetic information to clinical variables [25]. However, methods that incorporated external information—either through Bayesian priors or Frequentist weighted risk scores—achieved slightly higher AUC improvements (from 0.61 to 0.64) compared to standard logistic regression using only the current dataset [25].

Practical Implementation Protocols

Frequentist Workflow for Biological Data Fitting

Protocol Objective: To estimate parameters of a biological model and quantify uncertainty using Frequentist inference.

Materials and Reagents:

- Computational Environment: MATLAB with QuantDiffForecast (QDF) toolbox [23] [24] or R with

statspackage [26] - Data Requirements: Time-series or cross-sectional biological data

- Model Specification: Ordinary differential equations or algebraic models describing the biological system

Procedure:

- Model Formulation: Define the biological system using appropriate mathematical representations (e.g., ODEs for population dynamics)

- Objective Function Specification: Formulate the sum of squared differences between observed and predicted values as the objective function [23]

- Parameter Estimation: Implement nonlinear least-squares optimization using algorithms such as Levenberg-Marquardt [23]

- Uncertainty Quantification:

- Model Validation: Assess goodness-of-fit using residuals analysis and compute performance metrics (MAE, MSE) [23] [24]

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For non-converging optimization: adjust algorithm settings or initial parameter values

- For wide confidence intervals: consider structural identifiability analysis [23] [24]

Bayesian Workflow for Biological Data Fitting

Protocol Objective: To estimate posterior distributions of biological model parameters through Bayesian inference.

Materials and Reagents:

- Computational Environment: Stan via R (

rstanarm[26]) or Python (pymc3[19]) - Data Requirements: Experimental observations with appropriate likelihood specification

- Prior Information: Historical data or expert knowledge for prior distributions

Procedure:

- Prior Specification:

- Likelihood Definition: Specify the probability distribution of observed data given model parameters

- Posterior Sampling:

- Convergence Diagnostics:

- Posterior Analysis:

- Extract posterior summaries (means, medians, credible intervals)

- Perform posterior predictive checks to assess model fit

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For poor MCMC convergence: reparameterize model or adjust sampler settings

- For computational bottlenecks: reduce model complexity or use variational inference

Bayesian Optimization for Biological Experimentation

Protocol Objective: To efficiently optimize biological systems with limited experimental resources using Bayesian optimization.

Materials and Reagents:

- Software Framework: BioKernel or similar Bayesian optimization platform [17]

- Experimental System: Biological assay with quantifiable output (e.g., metabolite production)

- Design Variables: Factors to be optimized (e.g., inducer concentrations, media components)

Procedure:

- Experimental Design Space Definition: Identify input parameters and their feasible ranges [17]

- Initial Design: Select initial experimental points using space-filling design

- Surrogate Model Building:

- Acquisition Function Optimization:

- Select next experiment using Expected Improvement or Upper Confidence Bound [17]

- Balance exploration and exploitation based on experimental goals

- Iterative Experimentation:

- Conduct experiment at suggested condition

- Update GP model with new results

- Repeat until convergence to optimum

Application Notes:

- For astaxanthin production optimization, Bayesian optimization converged to near-optimal conditions in 22% of the experiments required by grid search [17]

- Particularly valuable for high-dimensional optimization problems (up to 20 dimensions) common in synthetic biology [17]

Table 3: Essential Resources for Statistical Modeling in Biological Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Frequentist Analysis | QuantDiffForecast (QDF) MATLAB Toolbox [23] [24] | ODE model fitting via nonlinear least squares with parametric bootstrap |

| Bayesian Analysis | BayesianFitForecast (BFF) with Stan [23] [24] | Hamiltonian Monte Carlo sampling for posterior estimation |

| Bayesian Analysis | R packages: rstanarm, brms [19] [26] |

Accessible Bayesian modeling interfaces |

| Bayesian Optimization | BioKernel [17] | No-code Bayesian optimization for biological experimental design |

| General Statistical Computing | R stats package [26], Python scipy.stats, pymc3 [19] |

Core statistical functions and Bayesian modeling |

| Clinical Trial Applications | PRACTical design analysis tools [26] | Personalized randomized controlled trial analysis |

Decision Framework for Objective Function Selection

The choice between Bayesian and Frequentist approaches should be guided by specific research constraints and goals (Table 4).

Table 4: Method Selection Guide for Biological Data Fitting

| Research Context | Recommended Approach | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Rich, complete data | Frequentist | Maximum efficiency with minimal assumptions [23] [24] |

| Sparse or noisy data | Bayesian | Robust uncertainty quantification [23] [24] |

| Prior information available | Bayesian (informative priors) | Leverages historical data or expert knowledge [19] [26] |

| Requiring objective analysis | Frequentist (or Bayesian with uninformative priors) | Minimizes subjectivity [19] |

| Complex, high-dimensional optimization | Bayesian optimization | Sample-efficient global optimization [17] |

| Sequential decision-making | Bayesian | Natural framework for iterative updating [19] |

| Regulatory compliance | Frequentist | Established standards in many domains [19] |

Frequentist methods are generally preferred when analyzing rich, fully observed datasets where computational efficiency is prioritized and minimal assumptions are desired [23] [24]. They provide a straightforward, objective framework that is well-established in many biological disciplines and regulatory contexts [19].

Bayesian approaches offer advantages when dealing with sparse data, complex models with latent variables, or when incorporating prior information from previous studies [23] [24] [19]. They are particularly valuable in sequential experimental designs where beliefs are updated as new data arrives, and in optimization problems where sample efficiency is critical [17] [19].

For researchers seeking a middle ground, empirical Bayes methods and Bayesian approaches with uninformative priors can provide some benefits of Bayesian inference while maintaining objectivity similar to Frequentist methods [19]. In many cases with large sample sizes and uninformative priors, both approaches yield substantively similar results [18] [19].

Both Bayesian and Frequentist statistical frameworks offer distinct philosophical perspectives and practical advantages for biological data fitting. The optimal choice depends critically on specific research contexts, including data richness, model complexity, availability of prior information, and analytical goals. Frequentist methods excel in well-observed settings with abundant data, while Bayesian approaches provide superior uncertainty quantification for sparse data and complex models with latent variables. As biological research continues to confront increasingly complex systems and limited experimental resources, thoughtful selection and implementation of appropriate statistical frameworks will remain essential for robust inference and efficient optimization. By understanding both the philosophical underpinnings and practical performance characteristics of these approaches, researchers can make informed decisions that enhance the reliability and efficiency of their biological data fitting endeavors.

In biological data fitting, the selection of an objective function is not merely a technical step but a fundamental strategic decision that directly aligns a model with its ultimate purpose. Whether the goal is accurate prediction of system behaviors, mechanistic explanation of underlying processes, or intelligent design of biological systems, the choice of optimization criterion dictates the model's capabilities and limitations. This framework is particularly crucial in synthetic biology and drug development, where experimental resources are severely constrained and suboptimal model selection can lead to costly, inconclusive campaigns. Bayesian optimization has emerged as a powerful solution for such scenarios, enabling researchers to intelligently navigate complex parameter spaces and identify high-performing conditions with dramatically fewer experiments than conventional approaches [17]. The following sections establish a structured methodology for matching model objectives to appropriate function selection, supported by quantitative comparisons, experimental protocols, and practical implementation tools.

Theoretical Framework: Aligning Purpose with Mathematical Formalism

A Taxonomy of Model Purposes

Biological models generally serve one of three primary purposes, each demanding distinct mathematical formulations and evaluation criteria:

Prediction: Focuses on forecasting future system states or responses under novel conditions. The objective function must prioritize accuracy and generalizability to unseen data, often employing likelihood-based or empirical risk minimization approaches. For example, machine learning models in drug discovery optimize predictive accuracy for target validation and biomarker identification [27].

Explanation: Aims to elucidate causal mechanisms and generate biologically interpretable insights. The objective function should enforce parsimony and structural fidelity to known biology, often incorporating prior knowledge constraints. Methods like CORNETO exemplify this approach by integrating prior knowledge networks (PKNs) to guide inference toward biologically plausible hypotheses [10].

Design: Supports the creation of novel biological systems with desired functionalities. The objective function must balance performance optimization with practical constraints, often employing sophisticated exploration-exploitation strategies. Bayesian optimization excels here by sequentially guiding experiments toward optimal outcomes with minimal resource expenditure [17].

Objective Function Selection Guide

Table 1: Alignment of model purposes with objective function characteristics and representative algorithms.

| Model Purpose | Primary Objective | Function Characteristics | Representative Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction | Forecasting accuracy | High predictive power, generalizability | Deep Neural Networks [27], Gaussian Processes [17] |

| Explanation | Mechanistic insight | Interpretability, biological plausibility, parsimony | Symbolic Regression [28], Knowledge-Based Network Inference [10] |

| Design | Performance optimization | Sample efficiency, constraint handling | Bayesian Optimization [17], Multi-objective Optimization [28] |

Quantitative Comparison of Optimization Approaches

Empirical evaluations demonstrate the significant efficiency gains achieved by purpose-driven optimization strategies. In a retrospective analysis of a metabolic engineering study, Bayesian optimization converged to the optimal limonene production regime in just 22% of the experimental points required by traditional grid search [17]. This represents a reduction from 83 to approximately 18 unique experiments needed to identify near-optimal conditions. Similarly, LogicSR, a framework combining symbolic regression with prior biological knowledge, demonstrated superior accuracy in reconstructing gene regulatory networks from single-cell data compared to state-of-the-art methods [28]. The table below quantifies these performance advantages across different biological domains.

Table 2: Empirical performance comparison of optimization methods across biological applications.

| Application Domain | Traditional Method | Advanced Method | Performance Advantage | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Engineering [17] | Grid Search | Bayesian Optimization | 78% reduction in experiments | Points to convergence (83 vs. 18) |

| Gene Regulatory Network Inference [28] | Standard Boolean Networks | LogicSR (Symbolic Regression) | Superior accuracy | Edge recovery and combinatorial logic capture |

| Multi-sample Network Inference [10] | Single-sample analysis | CORNETO (Joint inference) | Improved robustness | Identification of shared and condition-specific features |

Experimental Protocols for Objective Function Implementation

Protocol 1: Bayesian Optimization for Biological Design

This protocol details the implementation of Bayesian optimization for resource-efficient biological design, such as optimizing culture conditions or pathway expression.

I. Experimental Preparation

- Define Parameter Space: Identify critical input variables (e.g., inducer concentrations, temperature, media components) and their plausible ranges.

- Establish Objective Function: Define a quantifiable, reproducible output metric (e.g., product titer, fluorescence intensity, growth rate).

- Plan Experimental Logistics: Account for batch effects, replication strategy, and measurement noise.

II. Computational Setup (BioKernel Framework)

- Select Kernel Function: Choose a covariance function appropriate for the biological system. The Matern kernel is a robust default for capturing smooth trends [17].

- Configure Acquisition Function: Select a function to balance exploration and exploitation:

- Expected Improvement (EI): General-purpose, balances exploration and exploitation.

- Upper Confidence Bound (UCB): More exploratory, suitable for high-noise environments.

- Probability of Improvement (PI): More exploitative, risks convergence to local optima.

- Incorporate Noise Model: Enable heteroscedastic noise modeling if measurement uncertainty varies significantly across the parameter space [17].

III. Iterative Experimental Cycle

- Initial Design: Conduct a small, space-filling set of experiments (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sample).

- Model Update: Fit the Gaussian Process surrogate model to all collected data.

- Next-Point Selection: Identify the parameter set that maximizes the acquisition function.

- Experiment & Measurement: Conduct the proposed experiment and measure the outcome.

- Loop: Repeat steps 2-4 until convergence or resource exhaustion.

IV. Validation

- Confirm optimal performance in biological replicates.

- Validate model predictions at held-out test points.

Protocol 2: Knowledge-Guided Network Inference for Explanation

This protocol outlines the use of frameworks like CORNETO for inferring context-specific biological networks by integrating omics data with structured prior knowledge.

I. Data and Knowledge Curation

- Compile Prior Knowledge Network (PKN): Assemble a network of known interactions from structured databases (e.g., SIGNOR, KEGG, Reactome). The PKN can be a graph or hypergraph [10].

- Process Omics Data: Prepare normalized omics measurements (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics) for multiple samples or conditions.

II. Framework Initialization

- Map Data to PKN: Project omics measurements onto the corresponding nodes in the PKN.

- Define Objective: Formulate the inference task as a constrained optimization problem (e.g., find a sparse subnetwork that best explains the data).

- Set Sparsity Constraints: Implement structured sparsity penalties to jointly infer networks across multiple samples, distinguishing shared and sample-specific mechanisms [10].

III. Network Inference and Analysis

- Execute Optimization: Solve the mixed-integer optimization problem to identify the optimal context-specific subnetwork.

- Reconstruct Network: Extract the selected edges and nodes to build the inferred network.

- Topological Analysis: Identify key regulators, enriched pathways, and functional modules within the inferred network.

IV. Biological Validation

- Perform enrichment analysis on the inferred network components.

- Design perturbation experiments (e.g., knockdown, inhibition) to test predicted key regulators.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential computational tools and biological reagents for implementing objective-driven biological optimization.

| Category | Item | Function/Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | BioKernel [17] | No-code Bayesian optimization interface | Optimizing media composition and incubation times |

| CORNETO [10] | Unified framework for knowledge-guided network inference | Joint inference of signalling networks from multi-omics data | |

| LogicSR [28] | Symbolic regression for gene regulatory network inference | Inferring combinatorial TF logic from scRNA-seq data | |

| Biological Resources | Marionette E. coli Strains [17] | Genomically integrated orthogonal inducible transcription factors | Creating high-dimensional optimization landscapes for pathway tuning |

| Prior Knowledge Networks [10] | Structured repositories of known molecular interactions | Providing biological constraints for explainable network inference | |

| scRNA-seq Datasets [28] | High-dimensional gene expression measurements at single-cell resolution | Inferring dynamic gene regulatory networks during differentiation |

Practical Implementation: Selecting and Applying Objective Functions Across Biological Domains

Inferring objective functions from experimental data is a cornerstone of building accurate dynamical models in biological research. This process, often termed inverse optimal control or inverse optimization, involves deducing the optimization principles that underlie biological phenomena from observational data [29]. Living organisms exhibit remarkable adaptations across all scales, from molecules to ecosystems, many of which correspond to optimal solutions driven by evolution, training, and underlying physical and chemical constraints [29]. The selection of an appropriate objective function is thus critical for constructing models that are not only predictive but also biologically interpretable. This is particularly true in therapeutic contexts, where understanding the mechanisms driving disease processes like cancer metastasis can reveal potential therapeutic targets [30].

The challenge lies in the inherent complexity of biological systems. Parameters in biochemical reaction networks can span orders of magnitude, systems often exhibit stiff dynamics, and experimental data is typically sparse and noisy [31] [32]. Furthermore, the optimality principles themselves may be complex, involving multiple criteria, nested functions on different biological scales, active constraints, and even switches in objective during the observed time horizon [29]. This protocol outlines established and emerging methodologies for defining and inferring objective functions for dynamical systems described by Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs), Partial Differential Equations (PDEs), and Hybrid Models, with a focus on applications in drug development research.

Theoretical Foundations and Definitions

Core Concepts

- Dynamical System: A system of equations describing the time evolution of state variables (e.g., metabolite concentrations, cell densities). For ODEs, this is expressed as ( \frac{dm(t)}{dt} = S \cdot v(t, m(t), \theta) ), where ( m ) represents metabolite concentrations, ( S ) is the stoichiometric matrix, ( v ) is the flux vector, and ( \theta ) are parameters [32].

- Objective Function (Loss Function): A scalar function that quantifies the discrepancy between model predictions and experimental data, often combined with regularization terms. It is the target of minimization during model training.

- Inverse Optimal Control (IOC): A comprehensive framework for inferring optimality principles (including multi-criteria objectives and constraints) directly from experimental data [29].

- Universal Differential Equations (UDEs): A hybrid modeling framework that combines mechanistic differential equations with data-driven machine learning components, such as artificial neural networks (ANNs), to model systems where underlying equations are partially unknown [31].

- Parameter Identifiability: The property of a model and dataset that ensures its parameters can be uniquely determined from the available data, a common challenge in biological modeling [32].

Table of Common Objective Functions in Biological Modeling

Table 1: Typology of objective functions used in dynamical systems biology.

| Model Type | Objective Function Formulation | Key Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classic ODE/PDE | ( J(\theta) = \sum (y{pred} - y{obs})^2 ) Mean-squared error between prediction and observation. | Parameter estimation for metabolic kinetic models [32]; Inference of PDEs for cell migration [30]. | Intuitive; Well-understood theoretical properties. |

| Scale-Normalized ODE/PDE | ( J(\theta) = \frac{1}{N} \sum \left( \frac{m{pred} - m{obs}}{\langle m_{obs} \rangle} \right)^2 ) Mean-centered loss to handle large concentration ranges [32]. | Fitting kinetic models with metabolite concentrations spanning orders of magnitude [32]. | Prevents loss function domination by high-abundance species. |

| Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) | ( J(\theta) = -\log \mathcal{L}(\theta \mid \text{Data}) ) Where ( \mathcal{L} ) is the likelihood function. | Calibration with complex noise models; Enables uncertainty quantification [31]. | Statistically rigorous; Accounts for measurement noise. |

| Hybrid Model (UDE) | ( J(\thetaM, \theta{ANN}) = \text{MSE} + \lambda \parallel \theta{ANN} \parallel2^2 ) Combines data misfit and L2-regularization on ANN weights [31]. | Systems with partially known mechanisms [31] [32]. | Balances mechanistic insight with data-driven flexibility. |

Protocols for Objective Function Selection and Application

Protocol 1: Generalized Inverse Optimal Control for Biological Systems

This protocol describes a data-driven approach to infer multi-criteria optimality principles, including potential switches in objective, directly from experimental data [29].

Step 1: Problem Formulation and Data Preparation

- Define the state variables of the biological system and the control inputs (if any).

- Gather high-quality, time-resolved experimental data for the state variables. The data quality is paramount for a well-posed inference problem [29].

Step 2: Define a Candidate Set of Optimality Principles

- Postulate a set of potential objective functions (e.g., maximization of robustness, minimization of time, energy efficiency) based on domain knowledge [29].

- Consider the potential for nested objective functions operating at different biological scales (e.g., cellular, tissue, organ).

- Account for the possibility of active constraints and switches between dominant optimality principles during the observed time horizon.

Step 3: Model Inference and Validation

- Use the generalized inverse optimal control framework to infer which combination of principles best explains the observed data.

- Validate the inferred principles by testing their predictive power on a held-out dataset not used for inference.

- The resulting principles can be used for forward optimal control to predict and manipulate biological systems in biomedical applications [29].

Protocol 2: Building and Training Universal Differential Equations (UDEs)

This protocol outlines a systematic pipeline for developing hybrid models, which is critical when a system is only partially understood [31] [32].

Step 1: Model Design and Hybridization

- Define the Mechanistic Core: Formulate the parts of the system that are well-understood using known ODEs/PDEs (e.g., mass balance equations from stoichiometry) [32].

- Identify the Black-Box Component: Replace unknown or overly complex dynamic processes with a neural network. For example, an unknown reaction flux ( v(t, m(t), \theta) ) can be replaced by an ANN [31] [32].

- The resulting UDE takes the form: ( \frac{dm(t)}{dt} = S \cdot \text{ANN}(t, m(t), \theta_{ANN}) ) or a hybrid where only some fluxes are modeled by ANNs.

Step 2: Implementation and Pre-Training Setup

- Reparameterization: Log-transform mechanistic parameters ( \theta_M ) to enforce positivity and handle large value ranges. For bounded optimization, use a tanh-based transformation [31].

- Input Normalization: Normalize inputs to the ANN to improve numerical conditioning.

- Solver Selection: For systems with stiff dynamics (common in biology), use specialized stiff ODE solvers (e.g.,

KenCarp4,Kvaerno5) [31] [32].

Step 3: Training with a Multi-Start and Regularization Strategy

- Loss Function: Use a scale-normalized loss (see Table 1) and a regularized objective for the ANN:

Total Loss = Data Misfit + λ * ||θ_ANN||₂²[31] [32]. - Multi-Start Optimization: Jointly sample initial values for mechanistic parameters ( \thetaM ), ANN parameters ( \theta{ANN} ), and hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate, ANN size) to thoroughly explore the complex (hyper-)parameter space [31].

- Gradient Clipping: Clip the global gradient norm (e.g., to a value of 4) to prevent explosion during training, a common issue with neural ODEs [32].

- Early Stopping: Monitor performance on a validation set and stop training when it ceases to improve to prevent overfitting [31].

- Loss Function: Use a scale-normalized loss (see Table 1) and a regularized objective for the ANN:

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below.

Protocol 3: Inferring PDEs from Scratch Assay Data for Drug Effect Quantification

This protocol uses weak-form PDE inference to quantitatively measure the effect of drugs on cell migration and proliferation mechanisms, disambiguating contributions from random motion, directed motion, and cell division [30].

Step 1: Experimental Data Acquisition and Processing

- Perform a scratch assay on a confluent cell monolayer, with and without the drug of interest.

- Use live-cell microscopy to capture the evolution of the cell density field over time.

- Apply automated image processing to convert microscopy data into quantitative cell density maps [30].

Step 2: Candidate PDE Inference

- Employ a weak-form system identification technique (e.g., using the

WeakSINDyalgorithm) to automatically identify parsimonious PDE models from the cell density data. - The candidate model library should include bases for diffusion (random motion), advection (directed motion), and reaction (proliferation/death) terms [30].

- The inference process will select the dominant terms and estimate their parameters.

- Employ a weak-form system identification technique (e.g., using the

Step 3: Model Validation and Drug Effect Analysis

- Validate the identified PDE model by assessing its fit to the experimental data.

- Quantify the uncertainty in the inferred parameters.

- Compare the parameter values (e.g., the diffusion coefficient for random motion) between the control and drug-treated conditions. A reduction in the diffusion coefficient indicates the drug inhibits random cell migration [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential computational tools and resources for dynamical modeling in biology.

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| jaxkineticmodel [32] | A JAX-based Python package for simulation and training of kinetic and hybrid models. | Efficient parameter estimation for large-scale metabolic kinetic models; Building UDEs for systems biology. |

| SciML Ecosystem (Julia) [31] | A comprehensive suite for scientific machine learning, including advanced UDE solvers. | Handling stiff biological ODEs; Implementing and training complex hybrid models. |

| WeakSINDy Algorithms [30] | A model discovery tool for inferring parsimonious PDEs from data using weak formulations. | Identifying mechanistic models of cell migration and proliferation from scratch assay data. |

| Multi-Start Optimization Pipeline [31] | A robust parameter estimation strategy that samples many initial points to find global minima. | Reliable training of complex models (e.g., UDEs) with non-convex loss landscapes. |

| Log-/Tanh- Parameter Transformation [31] [32] | Ensures parameters remain in positive and/or physically plausible ranges during optimization. | Essential for handling biochemical parameters that span orders of magnitude. |

Concluding Remarks

The selection and inference of objective functions is a foundational step in modeling biological dynamics. While classic least-squares approaches remain useful, the field is moving towards more sophisticated frameworks like Generalized Inverse Optimal Control and Universal Differential Equations. These methods leverage both prior mechanistic knowledge and the pattern-recognition power of machine learning to create models that are predictive, interpretable, and capable of revealing underlying biological principles. The successful application of these protocols requires careful attention to the peculiarities of biological data, including stiffness, noise, and sparsity. By adhering to the detailed methodologies outlined herein, researchers in drug development can robustly calibrate models to quantitatively assess therapeutic interventions, from the metabolic to the cellular scale.