Network Topology of ASD Risk Genes: From Genetic Architecture to Therapeutic Discovery

This article synthesizes current research on the network topology of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) risk genes, addressing a core challenge in the field: bridging the gap between hundreds of identified...

Network Topology of ASD Risk Genes: From Genetic Architecture to Therapeutic Discovery

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the network topology of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) risk genes, addressing a core challenge in the field: bridging the gap between hundreds of identified genetic associations and a coherent understanding of the disorder's underlying biology. We explore the foundational genetic architecture of ASD, highlighting the shift from single-gene to polygenic and network-based perspectives. The content details advanced computational methodologies, including network propagation and co-expression analysis, that are used to pinpoint biologically relevant gene modules and core regulatory hubs from complex genomic data. We further address the critical challenge of heterogeneity by examining strategies for deconvolving ASD into more genetically homogeneous subtypes and optimizing network models for enhanced predictive power. Finally, we evaluate the translational potential of these approaches, showcasing how network-based findings are being validated and applied to identify novel biomarkers and reposition existing drugs for ASD treatment. This resource is designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage systems biology for breakthroughs in ASD etiology and therapy.

The Genetic Landscape and Network Architecture of Autism Spectrum Disorder

The genetic architecture of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) represents a complex continuum spanning rare, high-penetrance mutations and common, small-effect polygenic variation. This technical review synthesizes contemporary evidence from large-scale genomic studies to delineate the oligogenic model of ASD liability, wherein additive and interactive effects across variant classes determine individual risk and phenotypic outcomes. We provide quantitative comparisons of effect sizes and population attributable risks, detailed experimental methodologies for variant detection and burden analysis, and visualizations of genetic networks. For drug development professionals, this work highlights pathway convergence points and the critical importance of patient stratification based on genetic profiles for targeted therapeutic intervention.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) exemplifies the complexity of neurodevelopmental conditions, with its genetic underpinnings comprising multiple classes of risk variants operating through diverse biological mechanisms. Historically, research approaches have bifurcated into the study of rare variants with large effects and common variants with individually small effects, but contemporary models recognize their synergistic interplay in determining liability [1] [2]. This technical guide comprehensively synthesizes current understanding of ASD's oligogenic architecture, framing evidence within the context of risk genes network topology research.

The emerging paradigm rejects simplistic dichotomies in favor of a multifactorial model where de novo mutations (DNMs), inherited rare variants, and polygenic risk backgrounds collectively shape neurodevelopmental trajectories [1]. Recent studies employing person-centered phenotypic decomposition have revealed that distinct clinical presentations correlate with specific genetic programs, enabling more precise mapping of genotype-phenotype relationships [3]. Furthermore, evidence indicates that age at diagnosis reflects divergent developmental trajectories with distinct genetic profiles, underscoring the temporal dimension of genetic risk manifestation [4].

For researchers and therapeutic developers, understanding this architectural complexity is paramount for target identification, clinical trial design, and patient stratification strategies. This review integrates quantitative genetic findings with methodological guidance and network-based analytical frameworks to advance these applications.

The Spectrum of Genetic Contributions to ASD Liability

ASD liability arises from the integrated contribution of multiple variant classes with differing effect sizes and population frequencies. The table below quantifies the key parameters for major genetic risk categories.

Table 1: Quantitative Profile of Major Genetic Risk Variants in ASD

| Variant Class | Effect Size (OR/RRR) | Population Attributable Fraction | Key Characteristics | Associated Clinical Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rare De Novo Mutations (protein-truncating) | 2.5-20+ [1] | ~5-10% [1] | Arise spontaneously in germline; negative selection | Lower adaptive functioning, greater behavioral symptoms relative to family background [5] |

| Inherited Rare Variants (private, LGD) | 1.5-3.0 [1] | ~10-15% (estimated) | Transmitted across generations; often oligogenic | More likely in multiplex families; older mutational origin (2-3 generations) [1] |

| Common Variants (polygenic) | 1.05-1.15 per allele [2] | 40-50% [2] | Aggregate in polygenic scores; additive effects | Later diagnosis; increased socioemotional difficulties in adolescence [4] |

| Rare CNVs | 2.0-10.0 [1] | ~5% | Recurrent deletions/duplications; variable expressivity | Intellectual disability, developmental delays [6] |

The additive model of liability accumulation is supported by empirical evidence showing that ASD subjects carrying rare potentially damaging variants (PDVs) still carry a significant burden of common risk variants—intermediate between non-carrier ASD subjects and control subjects [2]. This indicates that common polygenic risk contributes to liability even in the presence of major rare variants.

Table 2: Developmental Trajectories and Genetic Correlations by Diagnosis Age

| Developmental Profile | Typical Age at Diagnosis | Polygenic Correlation with ADHD/Mental Health Conditions | Early Social/Communication Abilities | Socioemotional Trajectory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Childhood Emergent | Earlier diagnosis (by age 5-7) | Moderate genetic correlations [4] | Lower abilities in early childhood [4] | Stable or modestly attenuating difficulties [4] |

| Late Childhood Emergent | Later diagnosis (mid-childhood to adolescence) | Moderate to high positive genetic correlations [4] | Fewer difficulties in early childhood [4] | Increasing difficulties in late childhood/adolescence [4] |

Methodological Approaches for Variant Detection and Burden Analysis

Whole Exome/Genome Sequencing for De Novo Mutation Detection

Experimental Protocol: DNM identification requires trio-based design (proband + both parents) with high-quality sequencing.

- DNA Preparation: Extract DNA from whole blood (Korean, SSC cohorts) or saliva (SPARK cohort) using standardized protocols [5].

- Sequencing Platforms: Utilize Illumina platforms (NovaSeq 6000 for SPARK WES; HiSeq X10 for SSC WGS; HiSeq X for Korean WGS) [5].

- Variant Calling Pipeline:

- Align reads to GRCh38 using BWA-mem

- Process with GATK following best practices (v4.1.8.1 for Korean WES; v3.5 for SPARK/SSC)

- Apply variant quality score recalibration (VQSR)

- Perform joint genotyping with iterative gVCF genotyper (Korean WGS) or GLnexus (v1.4.1 for SPARK) [5]

- DNV Identification: Use Hail 0.2 de_novo() function with allele frequency <0.01% in gnomAD v3.1 non-neuro population [5].

- Quality Filtering:

- Heterozygous SNPs: QUAL ≥7.5, GQmean ≥36, DPmean ≥34, allele balance 0.275-0.725

- Heterozygous indels: QUAL ≥10.51, gDP ≥3, AB 0.214-0.786 [5]

- Variant Annotation: Apply Hail's vep() function with Ensembl VEP v109.3; classify as protein-truncating (PTV), missense (MIS), or synonymous [5].

Polygenic Risk Scoring and G-BLUP Analysis

Experimental Protocol: Common variant burden assessment for case-control and family-based designs.

- Genotyping and Quality Control:

- Genotype on Illumina platforms (Infinium OmniExpressExome-8 for PAGES; Human1M for SSC)

- Impute at Michigan Imputation Server using HRC reference panel [2]

- Apply post-imputation QC: exclude variants with R² < 0.3, MAF < 0.01

- LD Pruning: Use PLINK 2.0 with --clump-r² 0.81; --clump-kb 50 to obtain ~910K SNPs [2].

- PRS Calculation:

- Obtain GWAS summary statistics from ASD meta-analyses

- Clump SNPs to remove LD (r² < 0.1 within 250kb windows)

- Calculate scores as weighted sum of risk alleles: ( PRS = \sum{i}βi × Gi ) where (βi) is effect size and (G_i) is allele count [2]

- G-BLUP Implementation:

- Use genomic relationship matrix (GRM) from ~550K LD-pruned SNPs

- Apply mixed linear models to predict ASD status: ( y = Xβ + Zu + ε ) where u ~ N(0, Gσ²g) [2]

- Tune parameters via cross-validation within reference population

Within-Family Phenotype Deviation Analysis

Experimental Protocol: Control for familial background in phenotype-genotype mapping.

- Phenotype Standardization: Collect standardized measures of ASD core symptoms (Social Communication Questionnaire) and adaptive functioning (Vineland) [5].

- WFSD Calculation: Compute within-family standardized deviation: ( WFSD = \frac{(P{proband} - μ{unaffected})}{σ{unaffected}} ) where (μ{unaffected}) and (σ_{unaffected}) are mean and standard deviation of unaffected family members' scores [5].

- Outlier Analysis: Identify genes with high intrafamilial variability using per-gene WFSD distributions; apply statistical cutoffs (e.g., Z > 2.5) [5].

- Mutation Site Mapping: Corregate phenotypic heterogeneity with functional domains (e.g., voltage-sensing vs. pore-forming domains in SCN2A) [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for ASD Genetic Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Application in ASD Genetics | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina Sequencing Platforms | NovaSeq 6000, HiSeq X10, HiSeq X | Whole genome/exome sequencing of trios | DNM discovery in SSC, SPARK, Korean cohorts [5] |

| Genotyping Arrays | Infinium OmniExpressExome-8, Human1M, HumanOmni-2.5 | Common variant profiling in large cohorts | Polygenic scoring in PAGES, SSC [2] |

| GRCh38 Reference Genome | Genome Reference Consortium human build 38 | Unified reference for alignment and variant calling | All major consortium studies (SPARK, SSC, MSSNG) [5] |

| HRC Reference Panel | Haplotype Reference Consortium, ~65,000 haplotypes | Genotype imputation for common variants | Imputation at Michigan Imputation Server [2] |

| gnomAD Database | v3.1 non-neuro subset | Population allele frequency filtering | DNM identification (AF < 0.01%) [5] |

| STRING Database | v11, minimum score 0.9 threshold | Protein-protein interaction network construction | Interactome generation for PTHS [7] |

| Cytoscape with MCODE | v3.9.1, MCODE plug-in | Network module identification | Molecular complex detection in co-expression networks [7] |

| WGCNA R Library | v1.72-1, minimum module size 30 | Co-expression network analysis | Module identification in neural differentiation data [7] |

Network Topology of ASD Risk Genes

The convergence of ASD risk genes into functional networks represents a fundamental insight from systems biology approaches. Protein-protein interaction and co-expression analyses reveal that seemingly heterogeneous genetic risk factors coalesce into coordinated biological programs.

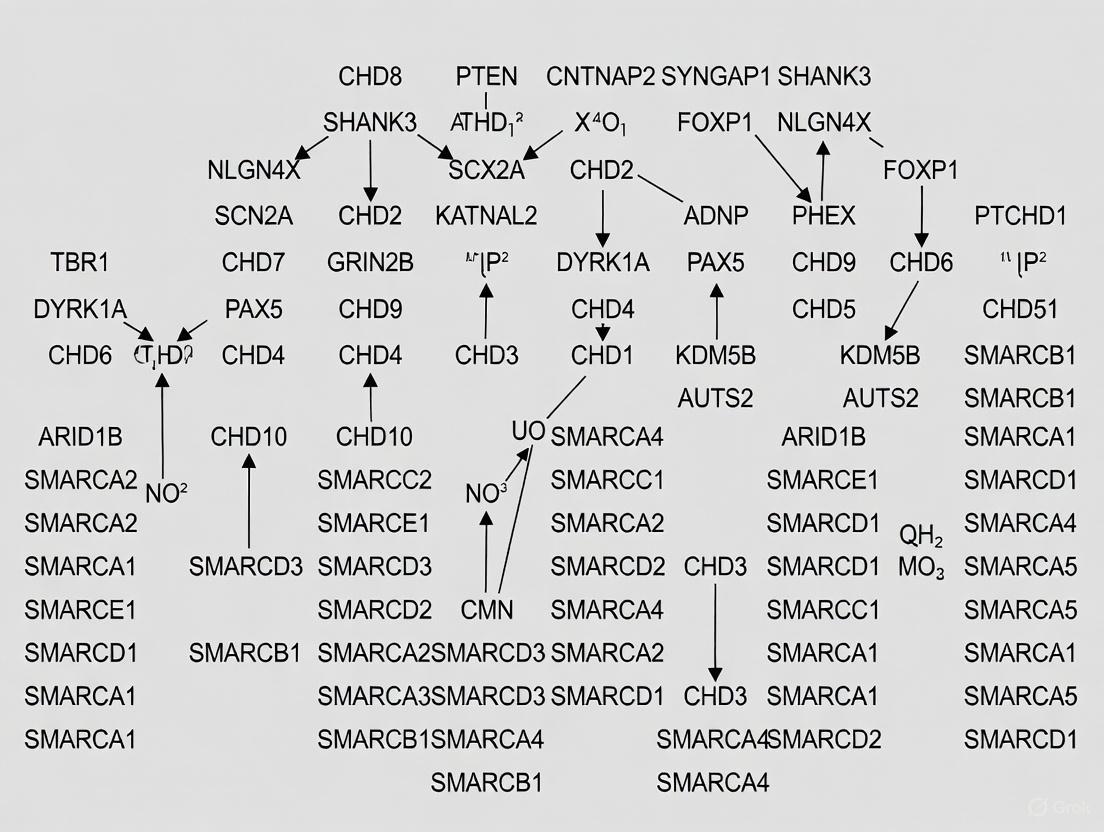

Figure 1: Integrated Network of ASD Genetic Risk Convergence. Multiple genetic risk classes converge on molecular networks that drive cellular phenotypes and clinical manifestations.

Analysis of Pitt-Hopkins syndrome (PTHS), a monogenic form of ASD caused by TCF4 mutations, reveals striking network topology through co-expression analysis in neural progenitor cells (NPCs) and neurons. The PTHS interactome demonstrates temporal specificity, with NPC networks enriched for upregulated genes (325 nodes, 504 edges; hypergeometric test p = 5.05e-34) while neuronal networks show predominant downregulation (673 nodes, 1897 edges; p = 7.58e-49) [7]. This temporal dynamic illustrates how ASD risk genes operate in developmentally regulated programs.

Hub gene analysis further identifies central nodes within co-expression modules, including:

- Histone gene family members - associated with neuronal differentiation pathways

- Synaptic vesicle trafficking proteins - regulating neurotransmission and connectivity

- Cell signaling mediators - integrating developmental cues [7]

These hub genes represent potential therapeutic targets as their central network positions exert disproportionate influence on overall system behavior.

Implications for Therapeutic Development

The oligogenic architecture of ASD necessitates precision medicine approaches for therapeutic development. Several strategic implications emerge:

Patient Stratification Biomarkers

Genetic profiling enables identification of biologically coherent subgroups with distinct pathway disruptions. Phenotypic decomposition analyses reveal four clinically distinct classes with characteristic genetic profiles: Social/behavioral, Mixed ASD with DD, Moderate challenges, and Broadly affected [3]. Each class demonstrates unique co-occurring condition patterns and developmental trajectories, suggesting differential treatment responses.

Target Prioritization Framework

The network topology of ASD risk genes provides a rational framework for target prioritization. Hub genes within co-expression modules represent particularly influential nodes whose modulation may produce cascading effects through entire functional networks [7]. For example, histone modification genes identified in PTHS analyses offer epigenetic intervention points.

Developmental Timing Considerations

The efficacy of targeted interventions likely depends on developmental windows. Genes associated with earlier ASD diagnosis show distinct expression patterns from those with later diagnosis [4], suggesting that treatments targeting these pathways may have age-dependent efficacy. Network analyses revealing temporal shifts in gene expression between NPC and neuronal stages further support this concept [7].

The genetic architecture of ASD embodies a complex, multilayered model where rare and common variants collectively determine liability through additive effects on convergent biological pathways. This oligogenic model supersedes earlier dichotomous frameworks and provides a more nuanced foundation for understanding disease mechanisms and advancing therapeutic development. The integration of person-centered phenotypic analysis with network biology approaches offers particularly promising directions for identifying coherent subgroups and their associated genetic programs. For drug development professionals, these advances enable more precise patient stratification, target identification, and clinical trial design aligned with the underlying biological heterogeneity of ASD.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition with a strong genetic basis. Research over the past decade has revealed that its pathogenesis involves hundreds of risk genes converging onto a limited set of biological pathways. Network-based analyses of these genes have proven particularly valuable for elucidating ASD pathophysiology, moving beyond single-gene approaches to system-level understanding. This whitepaper examines three core pathways—synaptic function, chromatin remodeling, and transcriptional regulation—that emerge consistently from network topology studies of ASD risk genes. By integrating findings from genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses, we provide a comprehensive technical overview of these pathways, their interconnections, and their implications for therapeutic development.

Synaptic Function and Signaling Pathways

Synaptic dysfunction represents one of the most consistently implicated mechanisms in ASD pathogenesis. Network analyses of ASD risk genes reveal significant enrichment for genes encoding proteins essential for synaptic formation, function, and plasticity.

Key Synaptic Pathways

Glutamatergic Signaling: Genes encoding glutamate receptors (GRIN2B) and postsynaptic density proteins (SHANK3) are frequently disrupted in ASD. These proteins mediate excitatory synaptic transmission and are crucial for learning and memory. Alterations in the balance between excitatory and inhibitory signaling have been proposed as a fundamental mechanism underlying ASD-related behaviors. Impaired NMDA receptor-dependent long-term potentiation (LTP) and enhanced long-term depression (LTD) have been observed in multiple ASD models, suggesting disrupted synaptic plasticity mechanisms [8] [9].

GABAergic Signaling: Genes involved in GABA synthesis (GAD), transport, and receptor function (GABRB3) show altered expression in ASD. These disruptions affect inhibitory neurotransmission, potentially contributing to the excitatory/inhibitory imbalance observed in ASD neural circuits. Postmortem studies have revealed significantly reduced levels of glutamic acid decarboxylase and GABAA and GABAB receptor alterations in brains of individuals with autism [9].

Neurexin-Neuroligin Pathway: These cell adhesion molecules organize presynaptic and postsynaptic domains and mediate trans-synaptic signaling. Mutations in genes encoding these proteins (NLGN3, NLGN4, NRXN1) disrupt synaptic connectivity and are among the most robustly associated with ASD. These proteins form a trans-synaptic bridge that organizes both sides of the synapse and regulates the balance of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission [10] [9].

Synaptic Multi-Omics Analysis

Recent advances in synaptosome analysis have enabled detailed molecular characterization of synaptic components in ASD. Integrated multi-omics approaches analyzing miRNAs, mRNAs, and proteins in synaptosomes from post-mortem brain tissues have revealed significant alterations in ASD.

Table 1: Synaptosome Multi-Omics Analysis in ASD

| Analysis Type | Sample Characteristics | Key Findings | Technical Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA-Seq | 27 AD, 14 controls | Upregulation of miRNA-501-3p, miRNA-502-3p, miRNA-877-5p with AD progression | Total RNA extraction with TriZol; LC Sciences HiSeq |

| mRNA-Seq | 27 AD, 14 controls | Hundreds of differentially expressed mRNAs affecting microglia, astrocytes, electron transport chain | Poly(A) RNA sequencing; Illumina NovaSeq 6000 |

| Proteomic Analysis | 27 AD, 14 controls | Alterations in Calsyntenin-1, GluR2, GluR4, Neurexin-2A | Mass spectrometry of synaptosomal proteins |

Integrated analysis revealed complex relationships between deregulated synaptic miRNAs and their target mRNAs and proteins, demonstrating the impact of deregulated miRNAs on synaptic function in ASD. DIABLO analysis showed intricate relationships among mRNAs, miRNAs, and proteins that could be key in understanding synaptic pathophysiology [8].

Chromatin Remodeling Mechanisms

Chromatin remodeling refers to the dynamic adjustment of chromatin structure through the action of enzyme complexes that change nucleosome positioning, composition, and accessibility. Network analyses have identified significant enrichment of chromatin remodeling genes among high-confidence ASD risk genes.

Chromatin Remodeling Complexes in ASD

ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes utilize ATP hydrolysis to alter nucleosome positions and modify histone-DNA interactions. These complexes are categorized into four major families based on their catalytic subunits and functional mechanisms.

Table 2: Chromatin Remodeling Complexes Implicated in ASD

| Complex Family | Key Subunits | Mechanism of Action | ASD Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| SWI/SNF | ARID1B, SMARCA2, SMARCA4 | Nucleosome sliding, eviction; chromatin decompaction | De novo LoF mutations in ARID1B, SMARCA2 |

| CHD/NuRD | CHD8, CHD7 | Nucleosome repositioning, histone deacetylation | CHD8 among strongest ASD risk genes |

| ISWI | SMARCA1, BAZ1B | Nucleosome spacing, chromatin compaction | Implicated in ASD via network analyses |

| INO80 | INO80, YY1 | Histone variant exchange (H2A.Z) | YY1 mutations associated with ASD |

These complexes regulate the accessibility of DNA to transcription factors and RNA polymerase, thereby controlling gene expression programs critical for neurodevelopment. Their disruption in ASD alters the transcriptional landscape of developing neurons, affecting processes such as neuronal differentiation, migration, and connectivity [10] [11] [12].

Mechanisms of Chromatin Remodeling

Nucleosome Sliding: Remodeling complexes use ATP hydrolysis to break histone-DNA contacts and reposition nucleosomes along DNA, exposing or concealing regulatory sequences.

Nucleosome Eviction: Complete removal of nucleosomes from specific DNA regions creates persistently accessible chromatin domains.

Histone Variant Exchange: Replacement of canonical histones with specialized variants (e.g., H2A.Z) alters nucleosome stability and properties.

Histone Modification: Covalent modifications (acetylation, methylation) of histone tails influence chromatin compaction and protein recruitment. Notably, genes encoding histone-modifying enzymes (KATNAL2, SUV420H1, ASH1L, MLL3) are recurrently mutated in ASD, particularly those involved in histone lysine methylation and demethylation [10] [12].

Transcriptional Regulation Networks

Transcriptional regulation represents a central hub in ASD gene networks, with numerous risk genes encoding transcription factors, coactivators, and components of the transcriptional machinery.

Transcriptional Complexes and Pioneer Factors

The process of transcriptional activation involves sequential recruitment of coregulatory complexes to gene regulatory elements. Chromatin modifiers play essential roles in this process by altering chromatin structure to facilitate transcription.

Pioneer Factors: Specialized transcription factors capable of binding compacted chromatin and initiating chromatin decompaction. Examples include FoxA and GATA factors, which can bind their target sequences in nucleosomal DNA and recruit additional factors. These factors exhibit cooperative relationships with nuclear receptors; for instance, FoxA1 and ERα bind DNA cooperatively, with each capable of pioneering chromatin access depending on cellular context [13].

Core Transcriptional Machinery: The basal transcription apparatus, including RNA polymerase II and associated general transcription factors, is recruited to promoters following chromatin remodeling.

Mediator Complex: A multi-subunit complex that bridges transcription factors with the RNA polymerase II apparatus, integrating signals from various regulatory elements.

Transcriptional Dysregulation in ASD

Network analyses have identified several key transcriptional regulators as high-confidence ASD risk genes, including TBR1, BCL11A, and MYT1L. These transcription factors often function at the top of regulatory hierarchies controlling neurodevelopmental gene expression programs. The convergence of ASD risk genes on specific transcriptional networks is evidenced by protein-protein interaction modules strongly enriched for autism candidate genes, with members exhibiting unusual evolutionary constraint against mutations [10].

ASD-associated mutations in transcriptional regulators disrupt gene expression programs essential for proper brain development, including neuronal specification, migration, and connectivity. These disruptions alter the transcriptomic landscape of the developing brain, ultimately affecting neural circuit formation and function [9].

Network Analysis Methods and Experimental Protocols

Network-based approaches provide powerful tools for identifying convergent pathways from diverse ASD genetic risk factors. These methods leverage protein-protein interactions, gene co-expression patterns, and functional annotations to detect modules enriched for ASD risk genes.

Gene Correlation Network Analysis

Sample Preparation:

- Utilize gene expression profiles from relevant tissues (e.g., peripheral blood lymphocytes or brain regions)

- Dataset: GSE25507 from NCBI with 82 autistic patients and 64 healthy controls

- Each sample contains 23,520 genes

- Data preprocessing with MAS5 and RMA algorithms

Network Construction:

- Establish Spearman correlation networks for both case and control groups

- Analyze structural parameters (average degree) under different thresholds

- Identify genes with significant differences in average degree between groups (MD-Gs)

Functional Analysis:

- Annotate top MD-Gs with significant structural differences

- Perform enrichment analysis for biological processes and pathways

- Validate findings against known ASD pathways and mechanisms [14]

Integrated Multi-Omics Analysis

Synaptosome Preparation:

- Extract synaptosomes from post-mortem brain samples (Brodmann's Area 10 of frontal cortices)

- Use Syn-PER Reagent with Dounce glass homogenization on ice

- Centrifuge at 1400g for 10min at 4°C, then collect supernatant

- Recentrifuge supernatant at 15,000g for 20min at 4°C to obtain synaptosome pellet

- Characterize isolated synaptosomes by transmission electron microscopy

Multi-Omics Profiling:

- Extract total RNA including miRNAs using TriZol reagent

- Perform miRNA and mRNA sequencing commercially (LC Sciences)

- Conduct proteomic analysis of synaptosomal proteins via mass spectrometry

- Integrate datasets using DIABLO analysis to identify multimodal molecular signatures [8]

Statistical Genetics Approach

Variant Calling and Annotation:

- Use exome sequencing data from 3,871 ASD cases and 9,937 controls

- Call SNVs and indels using GATK (v2.6) in a single large batch

- Identify de novo mutations with enhanced calling methods

- Annotate variants by type (de novo, case, control, transmitted, non-transmitted) and severity (LoF, damaging missense)

Gene-Based Association Testing:

- Apply TADA (Transmission and De novo Association) statistical model

- Integrate de novo, transmitted, and case-control variation

- Calculate gene-level Bayes Factors and False Discovery Rate q-values

- Validate findings using orthogonal approaches (e.g., female-male frequency differences) [10]

Pathway Visualization

Synaptic Dysfunction in ASD

Chromatin Remodeling in ASD

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ASD Pathway Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application in ASD Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Kits | Illumina TruSeq stranded mRNA kit | Library preparation for transcriptomic studies of ASD models |

| Antibodies | Anti-SHANK3, Anti-CHD8, Anti-PSD-95 | Protein expression analysis in postmortem brain tissues and cellular models |

| Cell Lines | iPSC-derived neurons from ASD patients | Modeling patient-specific mutations in synaptic and chromatin pathways |

| Animal Models | Shank3 KO, Chd8 heterozygous, Fmr1 KO mice | In vivo functional validation of ASD risk genes and pathways |

| Chromatin Assays | ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq kits | Profiling chromatin accessibility and histone modifications in ASD |

| Synaptosome Isolation | Syn-PER Reagent | Isolation of synaptic fractions for proteomic and transcriptomic analysis |

| Bioinformatic Tools | TADA, STRING, Cytoscape | Network analysis of ASD risk genes and pathway convergence |

Network analysis of ASD risk genes has systematically identified synaptic function, chromatin remodeling, and transcriptional regulation as three principal pathways disrupted in autism spectrum disorder. These pathways do not operate in isolation but exhibit significant crosstalk, forming an interconnected network that orchestrates neurodevelopment. The convergence of genetic risk factors onto these core pathways provides a framework for understanding ASD pathophysiology and developing targeted interventions. Future research should aim to further elucidate the temporal dynamics of these pathway disruptions across development and their specific roles in different neural circuits. The continued refinement of network-based approaches, combined with multi-omics profiling of well-characterized cohorts, will likely yield additional insights into ASD biology and identify novel therapeutic targets.

The autism spectrum disorder (ASD) interactome represents a comprehensive map of protein-protein interactions (PPIs) that form the molecular basis of neurodevelopmental processes. In the context of ASD risk gene research, network topology provides a crucial framework for understanding how seemingly disparate genetic risk factors converge on shared biological pathways. ASD is characterized by profound genetic heterogeneity, with hundreds of risk genes identified through sequencing studies, yet these genes consistently converge on specific functional networks and biological processes [15] [16]. The interactome concept moves beyond single-gene analysis to reveal how mutations in different genes can disrupt interconnected protein networks, ultimately leading to common pathological outcomes in ASD.

Recent advances in network medicine have demonstrated that proteins encoded by ASD risk genes do not operate in isolation but rather form functional modules within larger biological networks. These modules represent groups of proteins that work together to execute specific cellular functions, and their disruption provides critical insights into ASD pathophysiology. The application of interactome mapping in ASD research has revealed that the topological properties of risk genes within protein networks—including their connectivity, centrality, and relationship to network hubs—can illuminate fundamental disease mechanisms and identify novel therapeutic targets [16] [17].

Methodological Approaches for Interactome Mapping

Experimental Techniques for PPI Mapping

Proximity-Dependent Labeling in Neuronal Models

BioID2 (Proximity-Dependent Biotin Identification) has emerged as a powerful technique for mapping PPIs in cell-type-specific contexts. In this method, a promiscuous biotin ligase is fused to a protein of interest (bait), which then biotinylates proximate proteins in living cells. The biotinylated proteins can subsequently be purified and identified via mass spectrometry. This approach has been successfully applied to map interactions for 41 ASD risk genes in primary mouse neurons, revealing convergent pathways including mitochondrial processes, Wnt signaling, and MAPK signaling [17]. The key advantage of BioID2 is its ability to capture weak and transient interactions in live cells under physiological conditions.

Immunoprecipitation-Mass Spectrometry (IP-MS) in Human Neurons

IP-MS in induced excitatory neurons represents another robust approach for mapping the ASD interactome. This technique involves expressing ASD risk genes in human stem-cell-derived neurogenin-2 induced excitatory neurons (iNs), followed by immunoprecipitation of the index proteins and identification of interactors via liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [15] [18]. A landmark study applying this methodology to 13 high-confidence ASD risk genes identified more than 1,000 interactions, approximately 90% of which were novel, underscoring the importance of cell-type-specific protein interaction mapping [15]. The workflow typically includes validation steps through Western blotting and assessment of interaction reproducibility, with successful applications demonstrating greater than 80% replication rates.

Computational and Network-Based Approaches

Network Diffusion and Module Detection

Network diffusion-based methods analyze the propagation of genetic signals through molecular interaction networks to identify disease-relevant modules. These approaches leverage the "guilt-by-association" principle, positing that genes causing similar phenotypes tend to interact physically or functionally [16]. The network smoothing index (NSI) quantifies the network relevance of each gene in relation to a set of input ASD risk genes, considering the whole network while mitigating the excessive influence of highly connected hubs [16]. This method has proven particularly valuable for integrating multiple, non-overlapping ASD risk gene lists from different studies and identifying significantly connected gene modules associated with ASD.

Machine Learning and Gene Prioritization

Machine learning approaches integrate diverse data types—including spatiotemporal gene expression patterns from human brain development, gene-level constraint metrics, and network features—to predict novel ASD risk genes [19]. These methods typically employ supervised learning algorithms trained on known ASD risk genes from resources like SFARI (Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative) and use features such as brain region-specific co-expression patterns, protein-protein interaction network topologies, and evolutionary constraint metrics. Validation studies demonstrate that genes identified through these prediction models show enrichment in independent sets of ASD risk genes and tend to be dysregulated in postmortem ASD brains [19].

Key Findings from ASD Interactome Studies

Convergent Biological Pathways in ASD

Interactome mapping studies have consistently identified several key biological pathways that represent points of convergence for multiple ASD risk genes.

Table 1: Key Pathways Dysregulated in ASD Identified Through Interactome Mapping

| Pathway | ASD Risk Genes Involved | Biological Function | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synaptic Transmission | Multiple genes encoding synaptic scaffolding, vesicle trafficking, and neurotransmitter receptor proteins | Regulation of neuronal communication, synaptic plasticity, and neurotransmitter release | IP-MS in human iNs shows enrichment for synaptic proteins [15] [18] |

| Wnt Signaling | Proteins involved in canonical and non-canonical Wnt pathways | Regulation of neuronal differentiation, axon guidance, and synapse formation | BioID2 in primary neurons identifies Wnt components [17] |

| mTOR Signaling | PTEN, TSC1/2, and associated regulators | Control of cell growth, protein synthesis, and metabolism | Network analysis reveals mTOR pathway enrichment [15] |

| Chromatin Remodeling | CHD8, ARID1B, and other chromatin regulators | Epigenetic regulation of gene expression during neurodevelopment | Co-expression modules show chromatin remodeling enrichment [19] |

| Mitochondrial Function | Genes encoding mitochondrial proteins and metabolic regulators | Cellular energy production, oxidative stress response, and metabolism | BioID2 shows association between ASD risk genes and mitochondrial activity [17] |

| GABAergic Signaling | G protein subunits, GABA receptors, and associated proteins | Primary inhibitory neurotransmission in CNS | In silico analysis implicates G proteins in GABAergic pathways [20] [21] |

Network Topology of ASD Risk Genes

Table 2: Network Topology Properties of ASD Risk Genes

| Topological Property | Description | Research Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree Centrality | Number of direct interactions for a protein in the network | ASD risk proteins show variable connectivity, with some acting as hubs (e.g., DYRK1A with 604 interactors) and others having limited connections (e.g., PTEN with 3 interactors) | [15] |

| Betweenness Centrality | Measure of a protein's role as a connector between different network modules | Proteins with high betweenness may represent critical points of network vulnerability in ASD | [16] |

| Module Membership | Assignment of proteins to functionally related clusters | ASD risk genes cluster into distinct modules reflecting biological pathways (synaptic function, chromatin remodeling, etc.) | [17] [19] |

| Evolutionary Constraint | Tolerance to functional genetic variation | ASD risk genes show significant intolerance to protein-disrupting mutations (high pLI scores) | [19] |

Signaling Pathways in ASD Revealed by Interactome Mapping

G Protein-Coupled Receptor Signaling Pathways

Recent interactome studies have revealed dysregulation of G protein subunits in ASD pathophysiology. Experimental evidence shows altered serum levels of specific G protein subunits in individuals with ASD compared to controls, with significantly decreased GNAO1 and significantly increased GNAI1 levels observed [20] [21]. In silico analysis of the interaction networks involving these G protein subunits implicates them in GABAergic and dopamine signaling pathways, both critically involved in the neurobiological basis of ASD [21]. These findings suggest that dysregulation of G protein signaling pathways may represent a convergent mechanism in ASD.

IGF2BP Complex as a Convergent Network Node

Interactome studies in human induced neurons have identified the insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins (IGF2BP1-3) as a highly interconnected complex within the ASD protein network. These proteins, which together form an m6A-reader complex, each interact with at least five ASD index proteins, suggesting they may function as major mediators in convergent biological pathways for ASD risk [15] [18]. This complex potentially regulates a transcriptional circuit of ASD-associated genes, representing a point of functional integration for multiple genetic risk factors.

Clinical and Translational Applications

ASD Subtyping Based on Network Pathology

Recent large-scale studies have leveraged interactome data to identify biologically distinct subtypes of ASD. By analyzing data from over 5,000 children in the SPARK cohort and employing computational models that consider combinations of clinical traits and genetic profiles, researchers have defined four clinically and biologically distinct subtypes of autism [22]:

- Social and Behavioral Challenges Group (37%): Characterized by core autism traits without developmental delays, but with frequent co-occurring conditions like ADHD, anxiety, and depression.

- Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay (19%): Features developmental milestones delays but typically without anxiety, depression, or disruptive behaviors.

- Moderate Challenges (34%): Presents with milder core autism-related behaviors and typical developmental milestone achievement.

- Broadly Affected (10%): Displays wide-ranging challenges including developmental delays, social-communication difficulties, and co-occurring psychiatric conditions.

Each subtype demonstrates distinct genetic profiles, with the Broadly Affected group showing the highest proportion of damaging de novo mutations, while the Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay group is more likely to carry rare inherited genetic variants [22]. This subtyping approach enables more precise mapping of genetic risk factors to specific clinical presentations.

Drug Target Identification

Interactome mapping facilitates network-based drug target discovery by identifying proteins that occupy critical positions within dysregulated pathways. For example, the identification of the IGF2BP complex as a convergent node suggests that modulating its function could potentially impact multiple ASD risk pathways simultaneously [15] [18]. Similarly, the delineation of specific G protein signaling abnormalities points to potential targets for pharmacological intervention [20] [21]. The ability to cluster risk genes based on PPI networks has also been shown to identify gene groups corresponding to clinical behavior score severity, enabling more targeted therapeutic development [17].

Research Reagent Solutions for Interactome Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ASD Interactome Mapping

| Reagent/Tool | Application | Key Features | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| BioID2 System | Proximity-dependent labeling in live cells | Promiscuous biotin ligase for labeling proximate proteins, works in neuronal cells | Mapping protein interactions for 41 ASD risk genes in primary neurons [17] |

| IP-MS Platform | Protein complex isolation and identification | Antibody-based purification followed by LC-MS/MS identification | Identifying >1,000 interactions for 13 ASD genes in human iNs [15] [18] |

| STRING Database | Protein-protein interaction prediction | Integrates known and predicted PPIs from multiple sources | Building interactomes for network diffusion analysis [16] [20] |

| BrainSpan Atlas | Spatiotemporal gene expression reference | Transcriptomic data across human brain development and regions | Machine learning prediction of ASD risk genes [19] |

| SFARI Gene Database | Curated ASD risk gene resource | Categorizes genes by evidence strength for ASD association | Training and validation sets for prediction models [19] |

| Human iN Differentiation Protocol | Generation of excitatory neurons from stem cells | Neurogenin-2 induction for consistent excitatory neuron production | Cell-type-specific PPI mapping for ASD risk genes [15] [18] |

Future Directions

The evolving field of ASD interactome research is increasingly moving toward integration of multi-omics data and cell-type-specific network mapping. Future efforts will likely focus on expanding PPI networks to include more ASD risk genes across different neuronal cell types (e.g., inhibitory neurons, glial cells) and developmental time points. The combination of interactome data with other data modalities—including transcriptomics, epigenomics, and clinical information—holds promise for developing comprehensive network models that can predict disease trajectories and treatment responses. Additionally, the application of single-cell proteomics and spatial transcriptomics to ASD research will likely provide unprecedented resolution in understanding the cell-type-specific organization of protein networks disrupted in ASD.

As these technologies advance, interactome mapping will increasingly inform precision medicine approaches for ASD, enabling clinicians to match individuals with specific network pathologies to targeted interventions. The continued refinement of ASD subtypes based on underlying biological mechanisms, coupled with network-based drug discovery, represents a promising pathway toward more effective, personalized treatments for autism spectrum disorder.

The genetic architecture of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is exceptionally complex, characterized by high heritability estimates of 64-91% alongside significant heterogeneity [23]. Unraveling this complexity requires sample sizes orders of magnitude larger than those available to individual research institutions. This necessity has driven the formation of international consortia and large-scale genomic resources that aggregate data across multiple research sites. The Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research for Knowledge (SPARK) consortium, for example, represents a massive effort to collect and analyze genetic data from over 50,000 individuals with ASD, with current genomic data available for more than 115,000 participants, including over 44,000 with autism who have undergone whole exome sequencing [24]. Similarly, the Autism Sequencing Consortium (ASC) brings together international scientists who share ASD samples and genetic data, facilitating joint analysis of large-scale data from many groups [25]. These collaborative frameworks have enabled researchers to overcome previous limitations in statistical power, leading to the identification of hundreds of genetic loci significantly associated with ASD risk and providing insights into the biological pathways disrupted in the condition [26] [27].

The value of these resources extends beyond mere data aggregation. They provide standardized phenotypic characterization, implement rigorous quality control procedures, and develop innovative analytical frameworks that enable the research community to explore genotype-phenotype relationships at unprecedented resolution. The MSSNG resource, for instance, has recently expanded to include whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data from 5,100 individuals with ASD and 6,212 non-ASD family members, facilitating comprehensive examination of the roles of many types of genetic variation in ASD, including common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), rare and de novo single nucleotide variants (SNVs), short insertions/deletions (indels), mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) variants, and structural variants (SVs) [23]. This expanded scope allows researchers to move beyond a narrow focus on protein-coding regions to investigate the full genomic landscape of ASD.

Table 1: Major Genomic Resources for ASD Research

| Resource | Sample Size | Data Types | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPARK | >115,000 participants (44,000+ with ASD WES) [24] | WES, WGS, SNP array | Diverse genetic ancestry; family-based design; integration with phenotypic data |

| MSSNG | 11,312 individuals (5,100 with ASD) [23] | WGS (GRCh38) | Comprehensive variant calls (SNVs, CNVs, SVs, TREs); cloud-based data access via Google Cloud Platform |

| ASC | >50,000 exomes planned [25] | WES, WGS | International collaboration; coordinated analysis across sites; focus on rare variants |

| iPSYCH-PGC | >18,000 individuals with ASD [28] | GWAS | Population-based cohort; integration with national registries; common variant focus |

Key Findings from Genomic Studies

Common Variant Associations through GWAS

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified specific common genetic variants contributing to ASD risk, though their individual effect sizes are typically small. A recent GWAS on 6,222 case-pseudocontrol pairs from the SPARK dataset identified one novel genome-wide significant (GWS) locus and four significant loci through meta-analysis with previous studies [28]. The previously discovered three GWS ASD susceptibility loci from the iPSYCH-PGC study together explain only 0.13% of the liability for autism risk, whereas all common variants are estimated to explain 11.8% of liability [28], indicating that numerous additional common risk variants remain to be discovered.

Functional follow-up of GWAS findings has provided crucial insights into the biological mechanisms through which common variants influence ASD risk. For the novel locus identified in the SPARK GWAS, researchers employed a massively parallel reporter assay (MPRA) and identified a putative causal variant (rs7001340) with strong impacts on gene regulation [28]. Expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) data demonstrated an association between the risk allele and decreased expression of DDHD2 (DDHD domain containing 2) in both adult and prenatal brains, establishing DDHD2 as a novel gene associated with ASD risk [28]. This work exemplifies the progression from genetic association to biological mechanism that is becoming increasingly possible with large sample sizes.

More recent findings have revealed that the polygenic architecture of autism can be decomposed into genetically correlated factors that align with clinical heterogeneity. A 2025 study demonstrated that common genetic variants account for approximately 11% of the variance in age at autism diagnosis and can be broken down into two modestly genetically correlated (rg = 0.38) autism polygenic factors [4]. One factor associates with earlier autism diagnosis and lower social and communication abilities in early childhood, while the second links to later autism diagnosis and increased socioemotional and behavioral difficulties in adolescence, with differential genetic correlations with other neurodevelopmental conditions [4].

Rare Variant Contributions through WES/WGS

Whole exome and whole genome sequencing studies have dramatically expanded the catalog of rare variants contributing to ASD risk. The latest release of the MSSNG resource has enabled the identification of ASD-associated rare variants in 14.1% of individuals with ASD from MSSNG and 14.5% from the Simons Simplex Collection (SSC) [23]. In terms of genomic architecture, 52% were nuclear sequence-level variants, 46% were nuclear structural variants, and 2% were mitochondrial variants [23]. This comprehensive assessment demonstrates that structural variants contribute nearly as much as sequence-level variants to ASD genetic risk, highlighting the importance of analyzing all variant types.

By incorporating de novo variants from 12,375 additional trios from MSSNG and SPARK into the ASC's TADA+ analysis, researchers have identified 134 ASD-associated genes with false discovery rate (FDR) <0.1, including 67 new genes not previously associated with ASD [23]. Notably, 27 of these new genes are not currently in the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI) Gene database, providing novel molecules for study [23]. The evidence for most new genes constituted a mix of de novo protein-truncating variants (PTVs), de novo damaging missense (DMis) variants, and excess PTVs in cases compared with controls, though some genes showed evidence exclusively of PTVs (e.g., MED13, TANC2, DMWD) or de novo DMis variants (e.g., ATP2B2, DMPK, PAPOLG) [23]. This provides insight into potential molecular mechanisms, with haploinsufficiency suggested as a common mechanism for PTV-biased genes and gain-of-function or dominant-negative mechanisms for DMis-biased genes.

Table 2: Variant Types Identified in ASD Genomic Studies

| Variant Category | Specific Types | Contribution to ASD Risk | Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Variants | Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) | ~11.8% of liability [28] | GWAS |

| Rare Coding Variants | Protein-truncating variants (PTVs), Damaging missense (DMis) | Identified in 14.1-14.5% of ASD cases [23] | WES, WGS |

| Structural Variants | Copy number variants (CNVs), inversions, large insertions, uniparental isodisomies | 46% of rare variant findings [23] | WGS, microarray |

| Other Variants | Tandem repeat expansions (TREs), mitochondrial variants | ~2% of rare variant findings [23] | Specialized WGS analysis |

Gene Networks and Biological Pathways

Integration of genomic findings with network analysis approaches has revealed that ASD-risk genes converge on specific biological processes and pathways. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis of differentially expressed genes in ASD has identified key hub genes including SHANK3, NLRP3, SERAC1, TUBB2A, MGAT4C, TFAP2A, EVC, GABRE, TRAK1, and GPR161 [26]. These genes display high connectivity within molecular networks and have demonstrated strong discriminatory power in differentiating ASD from controls, particularly MGAT4C (AUC = 0.730) [26].

Network-based analyses leverage the principle of "guilt by association," where the function of an unannotated protein may be similar to that of its neighbors in a network if many of those neighbors are annotated with the same function [29]. Dense interconnections in protein interaction networks are characteristic of protein complexes or pathways, enabling identification of both known complexes and novel components of known systems [29]. In the context of ASD, such approaches have revealed abnormalities in key biological pathways involved in synaptic function, chromatin remodeling, and transcriptional regulation [26].

Recent work has also linked genetic findings to specific phenotypic presentations through person-centered approaches. Using generative mixture modeling on broad phenotypic data from 5,392 individuals in the SPARK cohort, researchers identified four clinically relevant classes of ASD that demonstrate distinct patterns of core, associated, and co-occurring traits [3]. These phenotypic classes show correspondence to genetic and molecular programs of common, de novo and inherited variation, with class-specific differences in the developmental timing of affected genes aligning with clinical outcome differences [3]. This represents a significant advance beyond trait-centric approaches that marginalize co-occurring phenotypes.

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) Protocol

The standard protocol for GWAS in ASD research involves several key steps, as exemplified by the SPARK consortium approach [28]. First, genotype data undergoes rigorous quality control, including removal of individuals with call rates below a predetermined threshold and exclusion of monozygotic twins. Phasing is performed using algorithms such as EAGLE v2.4.1, followed by imputation using reference panels like the Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine (TOPMed) Freeze 5b, which consists of 125,568 haplotypes from multiple ancestries [28]. For family-based designs like SPARK, pseudocontrols are generated by selecting the alleles not inherited from parents to cases using PLINK 1.9 [28].

Association testing typically employs generalized linear models implemented in PLINK2 for SNPs with minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥ 0.01 and imputation quality score (R2) > 0.5 [28]. In family-based designs, cases and pseudocontrols are matched on environmental variables and genetic ancestry, eliminating the need for additional covariates. For population-based studies, covariates such as principal components are included to account for population stratification. Meta-analysis with previous GWAS datasets is performed using tools like METAL to enhance statistical power [28].

Figure 1: GWAS Workflow for ASD Genetics. The diagram illustrates the sequential steps from sample collection to functional validation of findings.

Whole Exome/Genome Sequencing Analysis

For sequencing-based studies, the analytical pipeline begins with quality assessment of raw sequencing data, followed by alignment to a reference genome (typically GRCh38 in recent studies) [23]. Variant calling employs multiple callers such as GATK and DeepVariant to enhance sensitivity and specificity [24]. Joint calling across samples improves accuracy for low-frequency variants [23]. Annotation of variants incorporates multiple databases to predict functional consequences, including effects on protein coding, regulatory elements, and evolutionary conservation.

Rare variant association tests for ASD typically employ specialized statistical frameworks like the transmission and de novo association (TADA) test, which integrates multiple lines of evidence including de novo mutations, rare inherited variants, and case-control differences in mutation burden [23]. The TADA+ framework, developed by the Autism Sequencing Consortium, incorporates data from tens of thousands of trios to identify genes with FDR < 0.1 [23]. For structural variant detection, multiple algorithms are often combined, followed by manual curation to reduce false positives.

Network Analysis and Integration Approaches

Network analysis of ASD genetic data involves constructing protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks using databases like STRING (confidence score threshold ≥ 0.4) and importing into visualization software such as Cytoscape [26]. Differential expression analysis identifies significantly up- and down-regulated genes using linear modeling approaches with thresholds of |log2FC| > 1.5 and adjusted p-value (FDR) < 0.05 [26]. Functional enrichment analysis employing Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways uses hypergeometric distribution with multiple testing correction [26].

Network-based drug prediction utilizes the Connectivity Map (CMap) platform to identify potential therapeutic compounds that reverse expression signatures associated with ASD [26]. Immune infiltration correlation analysis explores associations between key genes and immune cell subpopulations using deconvolution algorithms implemented in R packages like "GSVA" [26]. Machine learning approaches, particularly random forest classifiers, are employed to identify feature genes with the highest importance scores for autism prediction, with performance validation through out-of-bag error estimates and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis [26].

Figure 2: Network Analysis Workflow. The process integrates multiple data types to identify key genes and pathways in ASD.

Genomic Datasets and Consortia

SPARK (Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research for Knowledge): Provides genomic data from over 115,000 participants, including WES data from 44,000+ individuals with autism. The resource includes mapped sequencing reads, SNP array genotyping data, and variant call files from multiple callers [24]. Access is controlled by a Data Access Committee for approved researchers.

MSSNG: A whole-genome sequencing resource containing data from 11,312 individuals (5,100 with ASD) aligned to GRCh38. The dataset includes joint-called small variants, structural variant calls, tandem repeat expansions, and polygenic risk scores [23]. Data are stored on the Google Cloud Platform with variant calls, annotations, and phenotype data available as BigQuery tables.

Autism Sequencing Consortium (ASC): An international collaboration that shares ASD samples and genetic data, currently working to sequence more than 50,000 exomes. The ASC hosts shared data and analysis at a single site to enable joint analysis of large-scale data from many groups [25].

Simons Simplex Collection (SSC): Includes permanently available genetic and phenotypic data from 2,600 simplex families (families with one child affected by ASD and unaffected parents and siblings). The collection includes detailed phenotypic assessments and serves as a valuable replication cohort [3].

Analytical Tools and Software

PLINK: A whole-genome association analysis toolset used for quality control, association analysis, and population stratification analysis. Essential for GWAS preprocessing and analysis [28].

STRENGTH (Structural Variation Detection): Tools for identifying copy number variants and other structural variations from WGS data. Critical for comprehensive variant detection beyond SNVs [23].

Cytoscape: An open-source platform for complex network visualization and analysis. Used for constructing and analyzing protein-protein interaction networks in ASD [26].

TADA (Transmission And De Novo Association): A statistical framework for identifying disease-associated genes by integrating de novo mutations and rare inherited variants. The enhanced TADA+ version incorporates data from tens of thousands of trios [23].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Application in ASD Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Datasets | SPARK, MSSNG, SSC, ASC [24] [23] [25] | Primary data sources for genetic discovery and validation |

| Analysis Tools | PLINK, EAGLE, METAL, TADA [28] [23] | Quality control, association testing, meta-analysis, rare variant association |

| Network Analysis | Cytoscape, STRING database, clusterProfiler [26] | PPI network construction, functional enrichment analysis |

| Functional Validation | Massively Parallel Reporter Assays (MPRA) [28] | Experimental validation of non-coding variant function |

| Expression Data | GTEx, BrainSpan, GEO datasets (e.g., GSE18123) [26] | Context-specific gene expression patterns and eQTL mapping |

The integration of large-scale genomic resources has fundamentally transformed our understanding of ASD genetics, moving from isolated discoveries to systematic mapping of risk genes and biological pathways. The convergence of findings from GWAS, WES, and WGS approaches has revealed a complex genetic architecture encompassing common and rare variants, coding and non-coding regions, and diverse molecular mechanisms. Network-based analyses have demonstrated that apparently heterogeneous genetic risk factors converge on coherent biological pathways, particularly those involved in synaptic function, chromatin modification, and transcriptional regulation.

Future research will need to address several key challenges. First, increasing ancestral diversity in ASD genomic studies remains imperative, as current resources are still predominantly European-ancestry individuals. Second, integrating multi-omic data—including epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic profiles—will provide a more comprehensive view of the molecular mechanisms underlying ASD. Third, bridging the gap between genetic discovery and clinical application requires improved understanding of genotype-phenotype relationships and developmental trajectories, as exemplified by recent work decomposing phenotypic heterogeneity and identifying genetic programs underlying clinical differences [3] [4]. As these efforts mature, they hold promise for developing targeted interventions based on an individual's specific genetic profile and ultimately improving outcomes for autistic individuals across the lifespan.

Computational Methods for Uncovering Network Topology and Core Genes in ASD

Network propagation has emerged as a powerful computational technique for integrating multi-omic data within the context of protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks, offering significant potential for identifying autism spectrum disorder (ASD) risk genes. This method functions by simulating the flow of information through a biological network, starting with seed genes and propagating their influence to nearby nodes, thereby prioritizing genes based on their network proximity to known ASD-associated genes. By leveraging this approach on a scaffold of documented protein interactions, researchers can effectively combine diverse genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic datasets. This integration provides a more comprehensive understanding of the complex molecular interactions underlying ASD, ultimately helping to pinpoint high-confidence candidate genes and biological pathways for further experimental validation and therapeutic targeting [30] [31].

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition affecting an estimated 1 in 44 children, characterized by challenges in social communication, behavior, and learning. Its etiology is profoundly heterogeneous, involving a complicated interplay of genetic and environmental factors. A critical step in unraveling ASD's pathophysiology is identifying its genetic underpinnings, which is challenging due to the disorder's polygenic nature and the modest effect sizes of many contributing variants [30]. Extensive molecular studies have charted the ASD landscape across various information layers, including genome-wide association studies (GWAS), differential gene expression, alternative splicing changes, differential methylation, and copy number variations. Each investigation typically generates candidate lists of ASD-associated genes, creating a pressing need for computational methods that can consolidate these findings into a unified framework [30].

Network propagation offers a robust solution to this integration challenge. This method is grounded in the concept that genes associated with a specific disorder are not randomly distributed in a biological network but tend to cluster together or reside in specific network neighborhoods. The technique involves simulating a "random walk" on a PPI network, where known disease-associated genes serve as seeds. The influence of these seeds is then propagated to adjacent nodes, assigning a score to every gene in the network that reflects its proximity to the seed set. This approach effectively smooths noisy omics data and leverages the local structure of the interactome to prioritize candidate genes based on their network relationships rather than just individual statistical significance [30] [31]. Within the context of ASD, this is particularly valuable for discovering genes that may not reach genome-wide significance in standalone studies but that reside in network modules densely populated with other ASD risk genes, suggesting their functional relevance.

Core Methodology: A Technical Deep Dive

Data Integration and Feature Generation

The first stage in constructing a network propagation model for ASD involves the careful curation of diverse omic data sets to be used as seeds for the propagation process. The goal is to capture the multifaceted molecular perturbations associated with the disorder.

Table 1: Exemplary Multi-Omic Data Sources for ASD Network Propagation

| Data Type | Data Source | Number of Genes | Biological Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Gene Expression (DGE) | Cortex Samples [30] | 1,611 | Identifies genes with altered mRNA levels in post-mortem ASD brain tissues. |

| Differential Alternative Splicing | Cortex Samples [30] | 833 | Pinpoints genes with disrupted RNA splicing patterns in ASD. |

| Transmitted/De Novo Association (TADA) | Whole-Exome Sequencing [30] | 102 | Highlights genes enriched for rare, high-impact genetic variants. |

| Differential DNA Methylation & Expression | Cross-Cortex Analysis [30] | 18 | Reveals genes whose regulation may be affected by epigenetic changes. |

| Analysis of De Novo CNVs | Simons Simplex Collection [30] | 65 | Identifies genes located in genomic regions affected by copy number variations. |

Each of these ASD-related gene lists is used as a seed for an independent network propagation process on a PPI network. The human PPI network from Signorini et al. (2021), comprising 20,933 proteins and 251,078 interactions in its main connected component, serves as an effective scaffold. The initial value of each seed protein from a list of size s is set to 1/s. Network propagation is then run with a damping parameter ɑ = 0.8, a common setting that balances the influence of the seed nodes with the global network structure. The results are normalized using the eigenvector centrality method to prevent biases arising from the varying degrees (connectedness) of proteins within the network. The output is a set of propagation scores for each gene, representing its network proximity to the seed genes from each distinct omic dataset. These scores become the feature set for the gene in subsequent predictive modeling [30].

Machine Learning Integration

Once network-propagated features are generated for each gene, they are integrated using a machine learning model to produce a unified prediction score for ASD association. A random forest classifier is frequently employed for this task due to its ability to handle high-dimensional data and model complex interactions between features without overfitting.

The model requires a set of positive and negative examples for training. The SFARI Gene Scoring Module is a standard resource for this, providing a expert-curated assessment of evidence for gene association with ASD. In a typical training setup, "Category 1" (High Confidence) genes from SFARI are used as positives. An equal number of negative genes are randomly selected from those not present in the SFARI database to create a balanced dataset. The random forest model is then trained using the propagated feature vectors of these genes. A common implementation uses the sklearn Python package with default parameters: a maximum of 100 trees, no maximum tree depth, and a minimum of 2 samples required to split an internal node. The model's performance is rigorously evaluated using 5-fold cross-validation, assessing metrics like the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) and the Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC) [30].

Experimental Protocol and Validation

Performance Benchmarking

To validate the efficacy of the network propagation approach, its performance must be compared against existing state-of-the-art methods. A recent study demonstrated that a model integrating ten propagated features achieved a mean AUROC of 0.87 and an AUPRC of 0.89 in cross-validation, indicating high predictive accuracy [30]. Furthermore, this integrated model was shown to outperform the previous leading predictor, forecASD. When the same random forest classifier was trained on the features used by forecASD (BrainSpan expression and STRING interaction data), it yielded an AUROC of 0.87. In contrast, the network propagation features achieved a superior AUROC of 0.91 on the same dataset. As a negative control, running the propagation procedure on a random degree-preserving network still resulted in a relatively high AUROC (0.82), which underscores the intrinsic quality of the seed gene sets but also highlights the critical importance of using a biologically accurate PPI network [30].

Table 2: Model Performance Comparison (AUROC)

| Method | Data Features | AUROC |

|---|---|---|

| Integrated Network Propagation | 10 propagated scores from multi-omic data [30] | 0.91 |

| forecASD Benchmark | BrainSpan expression & STRING network [30] | 0.87 |

| Negative Control | Propagation on random degree-preserving network [30] | 0.82 |

After establishing model accuracy, an optimal classification cutoff (e.g., 0.86) can be calculated to maximize the product of specificity and sensitivity, facilitating the application of the model to predict novel ASD-associated genes. The biological relevance of the top-predicted genes is further confirmed by showing that their scores are significantly higher than those of random negative genes for SFARI categories 2 and 3, which were not used in the initial model training [30].

Functional Enrichment Analysis

Prioritized gene lists must be interpreted through the lens of biological function. Functional enrichment analysis of the top 84 genes predicted by a network propagation model (using a threshold that maximizes the sum of precision and recall) revealed several key pathways and phenotypes associated with ASD.

From the Human Phenotype Ontology, "Autistic Behavior" was the most significantly enriched term. Gene Ontology analysis of Biological Processes (GO:BP) and Molecular Functions (GO:MF) further connected these top genes to critical neural functions, providing a biological sanity check for the computational predictions and suggesting potential mechanisms for the disorder's pathophysiology [30]. This step is crucial for transitioning from a list of candidate genes to actionable biological insights.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing a network propagation pipeline for ASD gene discovery requires a suite of key data resources and software tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| SFARI Gene Database [30] | Gene Database | Provides expert-curated gene scores used as gold-standard labels for training and validating predictive models. |

| STRING Database [32] | PPI Network | A source of protein-protein interaction data that can serve as the scaffold for network propagation algorithms. |

| Signorini PPI Network [30] | PPI Network | A high-quality, manually curated human PPI network used specifically in the referenced study. |

| Cytoscape & CytoHubba [31] [32] | Network Analysis Software | Platforms for visualizing complex molecular interaction networks and identifying highly connected hub genes. |

| g:Profiler [30] | Functional Enrichment Tool | Used to perform statistical enrichment analysis of gene lists against GO terms, pathways, and phenotypic ontologies. |

| sklearn (Scikit-learn) [30] | Python Library | Provides the machine learning framework (e.g., Random Forest classifier) for integrating features and making predictions. |

Signaling Pathways and Convergent Biology

Network propagation studies in ASD have consistently revealed a convergent molecular architecture, implicating specific biological pathways and processes. A prominent finding is the convergence of multiple ASD-linked transcriptional regulators on a common set of synaptic genes. Research involving the depletion of nine different ASD-risk transcriptional regulators (including chromatin modifiers like CHD8 and SETD5, and transcription factors like TBR1) in primary neurons showed that despite their disparate primary functions, they disrupt the expression of a shared set of genes encoding critical synaptic proteins. This convergence was further reflected in a drastic disruption of neuronal firing patterns throughout maturation, linking transcriptional dysregulation directly to aberrant neuronal function [33].

Furthermore, a convergent molecular network has been identified underlying both ASD and congenital heart disease (CHD), explaining the clinical co-morbidity between these conditions. Network genetics approaches have pinpointed 101 genes with shared genetic risk for both disorders. This shared network is highly enriched for genes involved in specific pathways, with a family of ion channels (e.g., the sodium transporter SCN2A) being a key convergent pathway linking these functions to early brain and heart development. Validation in model systems like Xenopus tropicalis confirmed that disruption of these shared risk genes causes abnormalities in both organ systems [34].

Beyond the genome and transcriptome, phosphoproteomic studies add another layer of regulation. Multi-omics investigations of ASD mouse models (Shank3Δ4–22 and Cntnap2−/−) have identified that autophagy-related pathways are particularly affected. While global proteomics showed changes in postsynaptic components and mTOR signaling, phosphoproteomics revealed unique phosphorylation sites in key autophagy-related proteins like ULK2, RB1CC1, and ATG16L1. This suggests that altered phosphorylation patterns, not just expression changes, contribute significantly to the impaired autophagic flux observed in ASD models, highlighting a potential post-translational mechanism in the disorder's pathology [35].

Network propagation represents a paradigm shift in how researchers integrate complex, multi-scale biological data to elucidate the foundations of polygenic disorders like ASD. By using a PPI network as a scaffold, this method provides a powerful framework for consolidating evidence from genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic studies, effectively prioritizing high-confidence candidate genes that reside in relevant biological neighborhoods. The consistent discovery of convergent pathways—such as synaptic gene regulation, ion channel function, and autophagy—through independent network-based analyses underscores the robustness of this approach. As PPI networks become more complete and multi-omic datasets continue to expand, network propagation will remain an indispensable tool for translating genetic associations into a functional understanding of ASD biology, ultimately guiding the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is characterized by profound genetic heterogeneity, involving hundreds of risk genes that converge on a limited set of neurodevelopmental pathways. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) has emerged as a powerful systems biology approach to navigate this complexity by identifying modules of highly correlated genes in transcriptomic data, revealing functional networks dysregulated in ASD. Unlike differential expression analysis that focuses on individual genes, WGCNA considers the network topology of the entire transcriptome, capturing subtle but coordinated changes across biological pathways. This approach has proven particularly valuable for elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying ASD, as functionally related genes often exhibit coordinated expression patterns despite diverse genetic origins. Research demonstrates that ASD risk genes systematically coalesce into co-expression modules enriched for specific biological functions during human cortical development, including synaptic formation, chromatin remodeling, and immune responses [36] [37] [38]. By mapping these networks, researchers can identify central "hub genes" that may exert disproportionate influence on biological processes and represent promising targets for therapeutic intervention.

Key Dysregulated Modules and Pathways in ASD

WGCNA studies of postmortem ASD brain tissues have consistently identified specific dysregulated modules that illuminate the disorder's pathophysiology. These modules reflect core disruptions in neuronal function, immune processes, and cortical patterning.

Table 1: Key Dysregulated Co-Expression Modules Identified in ASD Brain Transcriptomes

| Module/Study | Expression in ASD | Key Functions/Pathways | Notable Hub Genes | Cellular Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuronal Module (M12) [36] | Downregulated | Synaptic transmission, vesicular transport | A2BP1, APBA2, SCAMP5, CNTNAP1 | Neurons, especially inhibitory neurons |

| Immune/Glial Module (M16) [36] | Upregulated | Immune/inflammatory response, astrocyte/microglia markers | - | Astrocytes, activated microglia |

| M2-Microglial Module (mod5) [37] | Upregulated | Type I interferon pathway, cytokine signaling, M2 microglial state | - | M2-activated microglia |

| Neuronal Module (mod1) [37] | Downregulated | Synaptic transmission, neuronal development | - | Neurons |

| Histone Module [7] | Dysregulated | Histone modification, neuronal differentiation | - | Neural progenitor cells, neurons |

Beyond these consistent module alterations, WGCNA has revealed fundamental disruptions in cortical organization in ASD. Remarkably, regional transcriptomic signatures that typically distinguish frontal and temporal cortex are significantly attenuated in ASD brains, suggesting abnormalities in cortical patterning established during fetal development [36]. This finding aligns with anatomical evidence of reduced structural differentiation between cortical regions in ASD, implicating impaired regional specification as a core disease mechanism.