Network Medicine: Harnessing Interactome Analysis for Disease Gene Discovery and Therapeutic Development

Interactome analysis represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research, moving beyond static gene lists to dynamic network models of disease.

Network Medicine: Harnessing Interactome Analysis for Disease Gene Discovery and Therapeutic Development

Abstract

Interactome analysis represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research, moving beyond static gene lists to dynamic network models of disease. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging protein-protein interaction networks (interactomes) to elucidate disease mechanisms. We explore the foundational principles of network medicine, detail cutting-edge methodological approaches from affinity purification mass spectrometry (AP-MS) to machine learning integration, and address key challenges like interactome incompleteness. The content further covers critical validation strategies and comparative analyses of public resources, synthesizing how these approaches are successfully identifying novel disease genes and revealing therapeutic vulnerabilities for aging, cancer, and rare diseases.

The Interactome Revolution: From Gene Lists to Network Biology in Human Disease

In molecular biology, an interactome constitutes the complete set of molecular interactions within a particular cell. The term specifically refers to physical interactions among molecules but can also describe indirect genetic interactions [1]. Traditionally, the scientific community has relied on static maps of these interactions; however, proper cellular functioning requires precise coordination of a vast number of events that are inherently dynamic [2]. A shift from static to dynamic network analysis represents a major step forward in our ability to model cellular behavior, and is increasingly critical for elucidating the mechanisms of human disease [2]. This paradigm shift is fundamental to disease gene discovery, as it allows researchers to understand how perturbations in these dynamic networks lead to pathological states.

From Static Maps to Dynamic Networks

Static interactome maps provide a crucial scaffold of potential interactions but offer no information about when, where, or under what conditions these interactions occur [2]. These maps are often derived from high-throughput methods like yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) systems or affinity purification coupled with mass spectrometry (AP/MS) [1].

A dynamic view of the interactome, in contrast, considers that an interaction may or may not occur depending on spatial, temporal, and contextual variation [2]. This dynamic variation can be:

- Reactive: Caused by exogenous factors like an environmental stimulus.

- Programmed: Driven by endogenous signals such as cell-cycle dynamics or developmental processes [2].

The integration of dynamic data—such as gene expression from knock-out experiments or protein abundance changes from quantitative mass spectrometry—onto static network scaffolds is a powerful approach to infer this temporal and contextual information [2]. Quantitative cross-linking mass spectrometry (XL-MS), for instance, enables the detection of interactome changes in cells due to environmental, phenotypic, pharmacological, or genetic perturbations [3].

Experimental Methods for Mapping Interactomes

Large-scale experimental mapping of interactomes relies on a few key methodologies, each with its own strengths and limitations. The following table summarizes the primary techniques and their application in generating dynamic data.

| Method | Core Principle | Key Applications | Considerations for Dynamic Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) [1] | Detects binary protein-protein interactions by reconstituting a transcription factor. | Genome-wide binary interaction mapping; suited for high-throughput screening. | Can produce false positives from interactions between proteins not co-expressed in time/space; best combined with contextual data [1]. |

| Affinity Purification Mass Spectrometry (AP/MS) [1] | Purifies a protein complex under near-physiological conditions followed by MS identification of components. | Identifying stable protein complexes; considered a gold standard for in vivo interactions [1]. | Provides a snapshot of complexes in a given condition; can be made dynamic by performing under multiple perturbations (e.g., time course, drug dose) [3]. |

| Cross-Linking Mass Spectrometry (XL-MS) [3] | Captures transient and weak interactions in situ using chemical cross-linkers, providing spatial constraints. | Detecting transient interactions; elucidating protein complex structures; quantitative dynamic interactome studies [3]. | Ideal for dynamic studies. Quantitative XL-MS using isotopic labels can directly measure interaction changes across different cellular states [3]. |

| Genetic Interaction Networks [1] | Identifies pairs of genes where mutations combine to produce an unexpected phenotype (e.g., lethality). | Uncovering functional relationships and buffering pathways; predicting gene function. | Reveals functional dynamics and redundancies; large-scale screens can map genetic interaction networks under different conditions [1]. |

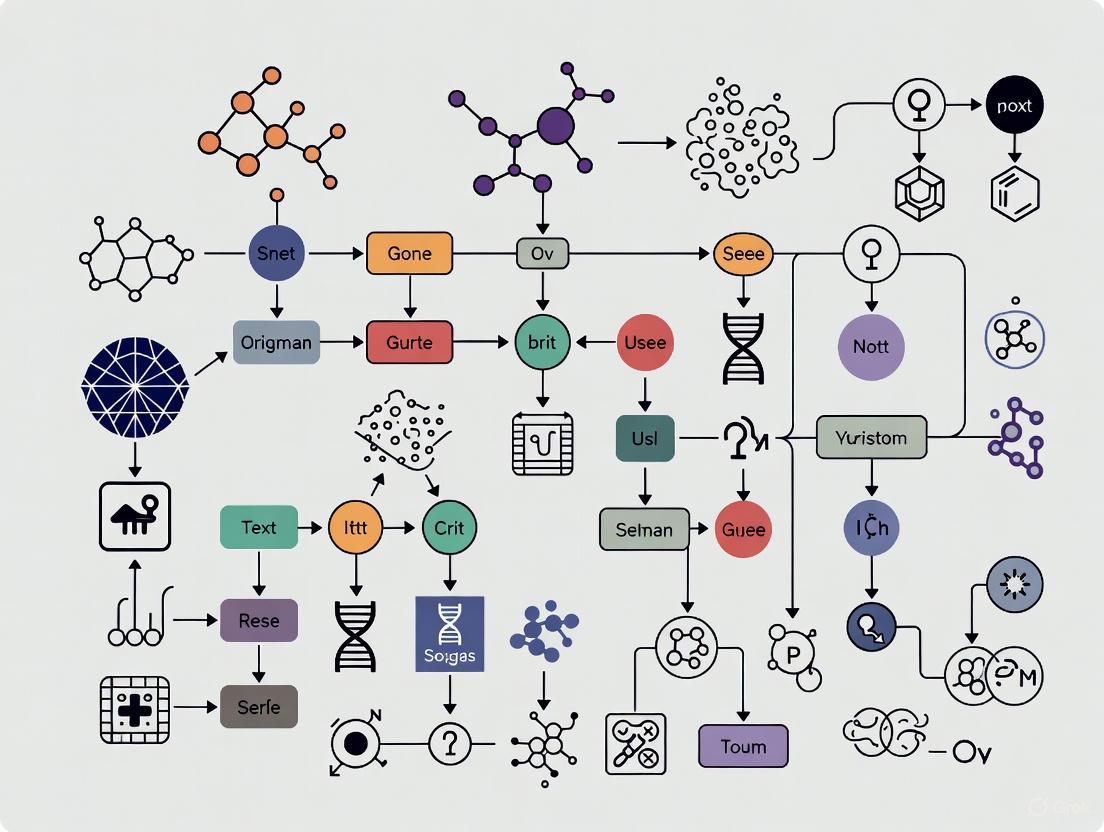

The following workflow diagram outlines a generalized protocol for generating and analyzing dynamic interactome data, integrating multiple methods:

Computational Analysis of Dynamic Interactomes

Computational methods are essential for interpreting static and dynamic interaction data. These approaches transform raw data into biological insights, particularly for disease gene discovery.

| Computational Method | Primary Function | Application in Disease Research |

|---|---|---|

| Network Validation & Filtering [1] | Assesses coverage/quality of interactomes and filters false positives using annotation similarity or subcellular localization. | Creates a reliable network foundation for downstream analysis, crucial for accurate disease gene association. |

| Pathway Inference [2] | Discovers signaling pathways from PPI data by finding paths between sensors/regulators, evaluated with gene expression. | Identifies disrupted pathways in disease; methods include linear path enumeration and Steiner tree algorithms [2]. |

| Interactome Comparison [2] [1] | Uncovers conserved pathways/modules via network alignment; predicts interactions through homology transfer ("interologs"). | Uses model organism data to inform human disease biology; limitations include evolutionary divergence and source data reliability [1]. |

| Gene Burden Analysis [4] | A statistical framework for rare variant gene burden testing in large sequencing cohorts to identify new disease-gene associations. | Directly identifies novel disease genes; the geneBurdenRD framework was used in the 100,000 Genomes Project to find new associations [4]. |

| Machine Learning for PPI Prediction [1] | Distinguishes interacting from non-interacting protein pairs using features like colocalization and gene co-expression. | Expands incomplete interactomes; Random Forest models have predicted interactions for schizophrenia-associated proteins [1]. |

The process of computationally analyzing an interactome for disease gene discovery can be visualized as a pipeline:

| Tool or Resource | Function in Interactome Research |

|---|---|

| Cytoscape [5] | Open-source software platform for visualizing complex molecular interaction networks and integrating these with any type of attribute data. |

| XLinkDB [3] | An online database and tool suite specifically for storing, visualizing, and analyzing cross-linking mass spectrometry data, including 3D visualization of quantitative interactomes. |

| geneBurdenRD [4] | An open-source R analytical framework for rare variant gene burden testing in large-scale rare disease sequencing cohorts to identify new disease-gene associations. |

| GeneMatcher [6] | A web-based platform that enables connections between researchers, clinicians, and patients from around the world who share an interest in the same gene, accelerating novel gene discovery. |

| Isotopically Labeled Cross-Linkers [3] | Chemical cross-linkers (e.g., "light" and "heavy" forms) that enable quantitative comparison of protein interaction abundance between different sample states using mass spectrometry. |

Application in Disease Gene Discovery and Drug Development

The dynamic interactome framework is revolutionizing disease research. Large-scale rare disease studies, such as the 100,000 Genomes Project, employ gene burden analytical frameworks to identify novel disease-gene associations by comparing cases and controls [4]. This approach has successfully identified new associations for conditions like monogenic diabetes, epilepsy, and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease [4].

Furthermore, linking a novel gene to a disorder, as demonstrated by the discovery of DDX39B's role in a neurodevelopmental syndrome, provides a critical window into fundamental biology and is the first step toward developing targeted therapeutic strategies [6]. The topology of an interactome can also predict how a network reacts to perturbations, such as gene mutations, helping to identify drug targets and biomarkers [1].

Visualization of Dynamic Interactomes

Effective visualization is key to interpreting complex interactome data. Tools like Cytoscape are industry standards for creating static network views and performing topological analysis [5]. For dynamic data, advanced tools are emerging. XLinkDB 3.0, for instance, enables three-dimensional visualization of multiple quantitative interactome datasets, which can be viewed over time or with varied perturbation levels as "interactome movies" [3]. This is crucial for observing functional conformational and protein interaction changes not evident in static snapshots.

The field of interactome analysis has matured from compiling static inventories of interactions to modeling their dynamic nature. This shift, powered by integrated experimental and computational methodologies, is providing an unprecedented, systems-level view of cellular function. For researchers focused on disease gene discovery and drug development, embracing this dynamic view is no longer optional but essential. It offers a powerful framework to pinpoint pathogenic mechanisms, diagnose patients with rare diseases, and identify new therapeutic targets, ultimately translating complex network biology into tangible clinical impact.

Network medicine represents a paradigm shift in understanding human disease, moving from a focus on single effector genes to a comprehensive view of the complex intracellular network [7]. Given the functional interdependencies between molecular components in a human cell, a disease is rarely a consequence of an abnormality in a single gene but reflects perturbations of the complex intracellular network [7]. This approach recognizes that the impact of a genetic abnormality spreads along the links of the interactome, altering the activity of gene products that otherwise carry no defects [7]. The field aims to ultimately replace our current, mainly phenotype-based disease definitions by subtypes of health conditions corresponding to distinct pathomechanisms, known as endotypes [8]. Framed within interactome analysis for disease gene discovery, network medicine offers a platform to systematically explore the molecular complexity of diseases, leading to the identification of disease modules and pathways, and revealing molecular relationships between apparently distinct phenotypes [7].

The Architecture of the Human Interactome

The human interactome consists of numerous molecular networks, each capturing different types of functional relationships. With approximately 25,000 protein-encoding genes, about a thousand metabolites, and an undefined number of distinct proteins and functional RNA molecules, the nodes of the interactome easily exceed one hundred thousand cellular components [7]. The totality of interactions between these components represents the human interactome, which provides the essential framework for identifying disease modules [7].

Table 1: Molecular Networks Comprising the Human Interactome

| Network Type | Nodes Represent | Links Represent | Key Databases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Interaction Networks | Proteins | Physical (binding) interactions | BioGRID, HPRD, MINT, DIP |

| Metabolic Networks | Metabolites | Participation in same biochemical reactions | KEGG, BIGG |

| Regulatory Networks | Transcription factors, genes | Regulatory relationships | TRANSFAC, UniPROBE, JASPAR |

| RNA Networks | RNA molecules | RNA-DNA interactions | TargetScan, miRBase, TarBase |

| Genetic Interaction Networks | Genes | Synthetic lethal or modifying interactions | BioGRID |

Organizing Principles of Biological Networks

Biological networks are not random but follow core organizing principles that distinguish them from randomly linked networks [7]. The scale-free property means the degree distribution follows a power-law tail, resulting in the presence of a few highly connected hubs that hold the whole network together [7]. These hubs can be classified into "party hubs" that function inside modules and coordinate specific cellular processes, and "date hubs" that link together different processes and organize the interactome [7]. Additionally, biological networks display the small-world phenomenon, meaning there are relatively short paths between any pair of nodes, so most proteins or metabolites are only a few interactions from any other proteins or metabolites [7].

Disease Modules: The Functional Units of Pathology

Definition and Properties

Disease-associated genes form highly connected subnetworks within protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks known as disease modules [8]. The fundamental hypothesis is that the phenotypic impact of a defect is not determined solely by the known function of the mutated gene, but also by the functions of components with which the gene and its products interact—its network context [7]. This context means that a disease phenotype reflects various pathobiological processes that interact in a complex network, leading to deep functional, molecular, and causal relationships among apparently distinct phenotypes [7]. Research has demonstrated that biological and clinical similarity of two diseases results in significant topological proximity of their corresponding modules within the interactome [8].

Local Neighborhoods and Network Proximity

The concept of local neighborhoods refers to the immediate network environment surrounding disease-associated genes. Studies have shown that disease genes are not distributed randomly throughout the interactome but cluster in specific neighborhoods [7] [8]. The local network properties around disease modules provide critical insights into disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. For instance, shared therapeutic targets or shared drug indications are correlated with high topological module proximity [8]. Furthermore, the network-based separation between drug targets and disease modules is indicative of drug efficacy, and FDA-approved drug combinations are proximal to each other and to the modules of the targeted diseases in the interactome [8].

Diagram 1: Disease modules within interactome. This diagram illustrates two disease modules (A and B) within the broader interactome, connected via a central hub protein. Dashed lines represent potential cross-module interactions that may explain comorbid conditions or shared pathomechanisms.

Methodological Framework for Disease Module Discovery

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The discovery of disease modules involves sophisticated computational and experimental approaches. Bird's-eye-view (BEV) approaches use large-scale disease association data gathered from multiple sources, while close-up approaches focus on specific diseases starting with molecular data for well-characterized patient cohorts [8]. BEV approaches have demonstrated that disease-associated genes form disease modules within PPI networks and that biological and clinical similarity of two diseases results in significant topological proximity of these modules [8]. However, these approaches must account for significant biases in data, including the fact that disease-associated proteins are tested more often for interaction than others, and the limitations of phenotype-based disease definitions [8].

Gene burden testing frameworks have been developed specifically for Mendelian diseases, analyzing rare protein-coding variants in large-scale genomic datasets [4]. The minimal input for such frameworks includes: (1) a file of rare, putative disease-causing variants obtained from merging and processing variant prioritization tool output files for each cohort sample; (2) a file containing a label for each case-control association analysis to perform within the cohort; and (3) corresponding file(s) with user-defined identifiers and case-control assignment per sample [4].

Diagram 2: Disease gene discovery workflow. This workflow outlines the key steps in identifying disease genes and modules, from patient selection through sequencing to network analysis and validation.

Quantitative Analysis of Disease Associations

Large-scale genomic studies enable the systematic discovery of novel disease-gene associations through rare variant burden testing. The 100,000 Genomes Project applied such methods to 34,851 cases and their family members, identifying 141 new associations across 226 rare diseases [4]. Following in silico triaging and clinical expert review, 69 associations were prioritized, of which 30 could be linked to existing experimental evidence [4].

Table 2: Representative Novel Disease-Gene Associations from Large-Scale Studies

| Disease Phenotype | Associated Gene | Genetic Evidence | Functional Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monogenic Diabetes | UNC13A | Strong burden test p-value | Known β-cell regulator |

| Schizophrenia | GPR17 | Significant association | G protein-coupled receptor function |

| Epilepsy | RBFOX3 | Rare variant burden | Neuronal RNA splicing factor |

| Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease | ARPC3 | Gene burden | Actin-related protein complex |

| Anterior Segment Ocular Abnormalities | POMK | Variant accumulation | Protein O-mannose kinase |

The analytical framework for such discoveries involves rigorous statistical testing for gene-based burden analysis of single probands and family members relative to control families [4]. This includes enhanced variant filtering and statistical modeling tailored to Mendelian diseases and unbalanced case-control studies with rare events [4].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Network Medicine

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Databases | 100,000 Genomes Project, Deciphering Developmental Disorders, Centers for Mendelian Genomics | Provide large-scale sequencing data for gene discovery |

| Interaction Databases | BioGRID, HPRD, MINT, DIP, KEGG | Curate molecular interactions for network construction |

| Disease Association Databases | OMIM, DisGeNET, GeneMatcher | Link genetic variants to disease phenotypes |

| Analytical Frameworks | geneBurdenRD, Exomiser | Perform statistical burden testing and variant prioritization |

| Validation Tools | GeneMatcher, patient cohorts | Connect researchers studying same genes across institutions |

The gene discovery process often begins with patients exhibiting suspected genetic disorders who remain undiagnosed after standard genomic testing [6]. For example, in the discovery of the DDX39B-associated neurodevelopmental disorder, researchers began with a patient with short stature, small head, low muscle tone, and developmental delays, using GeneMatcher to identify five additional patients with mutations in the same gene across the United Kingdom and Hong Kong [6]. All six patients had similar clinical presentations, ranging in age from 1 to 36 years old, demonstrating the value of global collaboration in validating novel gene-disease associations [6].

Current Challenges and Limitations

Data Biases and Limitations

Network medicine faces significant challenges related to data biases and limitations. Study bias distorts functional gene annotation resources, as cancer-associated proteins and other well-studied proteins are tested more often for interactions than others [8]. This bias affects network analysis methods, which may learn primarily from node degrees rather than exploiting biological knowledge encoded in network edges [8]. Additionally, incompleteness of disease-gene association and protein-protein interaction data remains a substantial limitation [8]. Perhaps most fundamentally, the reliance on phenotype-based disease definitions in current association data creates circularity, as network medicine aims to overcome these very definitions by discovering molecular endotypes [8].

The Local Blurriness Problem in Bird's-Eye-View Approaches

While BEV approaches show strong global-scale correlations between different types of disease association data, they demonstrate only partial reliability at the local scale [8]. This "local blurriness" means that when zooming in on individual diseases, the picture becomes less reliable [8]. For example, in analyses of neurodegenerative diseases, while global empirical P-values comparing gene- and drug-based diseasomes were significant at the 0.001 level, only two of seven local empirical P-values were significant at the 0.05 level [8]. This indicates that BEV network medicine only allows a distal view of endotypes and must be supplemented with additional molecular data for well-characterized patient cohorts to yield translational results [8].

Network medicine, through the study of local neighborhoods and disease modules, provides a powerful framework for understanding human disease in the context of the interactome. The core principles—that diseases arise from perturbations of cellular networks, that disease genes cluster in modules, and that network topology informs biological and clinical relationships—are transforming disease gene discovery research [7]. However, realizing the full potential of this approach requires addressing significant challenges, particularly the biases in current data resources and the limitations of bird's-eye-view analyses [8]. Future progress will depend on integrating large-scale computational approaches with detailed molecular studies of well-characterized patient cohorts, ultimately leading to a mechanistically grounded disease vocabulary that transcends current phenotype-based classification systems [8]. As the field advances, network medicine promises to identify new disease genes, uncover the biological significance of disease-associated mutations, and identify drug targets and biomarkers for complex diseases [7].

The conventional "one-gene, one-disease" model presents significant limitations in explaining the complex etiology of most human disorders. Network medicine, founded on the systematic mapping of protein-protein interactions (the interactome), offers a transformative framework by positing that disease genes do not operate in isolation but cluster within specific interactome neighborhoods known as disease modules [9] [10]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the evidence supporting disease gene clustering, details the experimental and computational methodologies for mapping these modules, and explores the profound implications for disease gene discovery and therapeutic development. The core thesis is that the interactome serves as an indispensable scaffold for interpreting genetic findings, revealing underlying biological pathways, and identifying novel drug targets.

Historically, the quest to understand genotype-phenotype relationships has been guided by a reductionist paradigm, successfully identifying mutations in over 3,000 human genes associated with more than 2,000 disorders [9]. However, challenges such as incomplete penetrance, variable expressivity, and the modest explanatory power of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for many complex traits underscore the limitations of this approach [9] [11]. These observations suggest that most genotype-phenotype relationships arise from a higher-order complexity inherent in cellular systems [9].

Network biology addresses this complexity by representing cellular components as nodes and their physical or functional interactions as edges. The comprehensive map of these interactions is the interactome [9]. The organizing principle of network medicine is that proteins involved in the same disease tend to interact directly or cluster in a specific, interconnected region of the interactome, forming a disease module [10]. This perspective shifts the focus from single genes to the functional neighborhoods and pathways they inhabit, providing a systems-level understanding of disease mechanisms.

The Theoretical Foundation of Disease Modules

The disease module concept is predicated on several key, testable hypotheses that have been empirically validated [10]:

- Disease proteins interact directly: Proteins associated with a specific disease have a higher probability of physical interaction than would be expected by chance.

- Disease proteins form interconnected clusters: These proteins aggregate into a connected subnetwork or module within the larger interactome.

- Functional unity: Proteins within a disease module are often involved in the same biological process or cellular function.

- Network locality of related diseases: Pathologically similar diseases occupy adjacent neighborhoods within the interactome, while unrelated diseases are topologically distant.

The existence of these modules explains why the functional impact of a mutation often depends not on a single gene but on the perturbation of the entire module to which it belongs [10].

Table 1: Key Properties and Evidence for Disease Modules in the Interactome

| Property | Description | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Local Clustering | Disease-associated genes form interconnected subnetworks. | In ~85% of diseases studied, seed proteins form a distinct subnetwork linked by no more than one intermediary protein [10]. |

| Pathway Enrichment | Modules are enriched for specific biological pathways. | The COPD network neighborhood was enriched for genes differentially expressed in multiple patient tissues [11]. |

| Topological Relationship | Related diseases reside in nearby network neighborhoods. | Network propagation revealed shared communities between autism and congenital heart disease [12]. |

| Predictive Power | Modules can identify novel candidate genes. | A network-based closeness approach identified 9 novel COPD-related candidates from 96 FAM13A interactors [11]. |

Methodologies for Mapping Disease Modules

Acquiring the Reference Interactome and Disease Gene Sets

The first step is the construction of a high-quality, comprehensive reference interactome.

- Reference Interactome Sources: The human interactome is compiled from curated databases, including:

- Disease Gene Sets ("Seeds"): Initial disease-associated genes are gathered from:

Core Computational Algorithms for Module Detection

Once seeds are mapped onto the interactome, several algorithms can extract the disease module.

Network Propagation and Random Walk

Network propagation "smoothes" the initial signal from the seed genes across the interactome, allowing the identification of genes that are topologically close to multiple seeds, even if they are not direct interactors. The Degree-Adjusted Disease Gene Prioritization (DADA) algorithm uses a degree-adjusted random walk to overcome the bias toward highly connected genes (hubs) [11].

Workflow:

- Seed genes are assigned an initial probability score.

- A random walk with restart (RWR) algorithm simulates the propagation of these scores through the network. At each step, the walker can move to a neighbor or jump back to a seed node.

- After many iterations, the probability scores stabilize. Genes with high final scores are considered part of the disease module.

This method was used to build an initial Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) network neighborhood of 150 genes, which formed a significant connected component (Z-score = 27, p < 0.00001) [11].

Network-Based Closeness for Targeted Data Integration

The incompleteness of the reference interactome can leave key disease genes disconnected. The CAB (Closeness to A from B) metric addresses this by measuring the topological distance between a set of experimentally identified interactors (A) and an established disease module (B) [11].

Protocol:

- Targeted Experiment: Perform affinity purification-mass spectrometry for a disease gene of interest (e.g., FAM13A in COPD) to identify its direct protein interactors (Set A).

- Initial Module: Establish an initial disease network neighborhood (Set B) using a method like DADA.

- Calculate Closeness: For each protein in Set A, compute its weighted shortest path distance to all proteins in Set B.

- Statistical Significance: Compare the observed distances to a null distribution generated from random gene sets. Proteins with a Z-score below a significance threshold (e.g., -1.6 for p < 0.05) are considered significantly close and integrated into the comprehensive disease module.

This approach identified 9 out of 96 FAM13A interactors as being significantly close to the COPD neighborhood [11].

Validation and Functional Analysis

- Genetic Signal Enrichment: The genes in the proposed module should be enriched for sub-threshold genetic association signals from GWAS (p-value plateau analysis) [11].

- Differential Expression: The module should be enriched for genes differentially expressed in relevant diseased tissues (e.g., alveolar macrophages, lung tissue for COPD) [11].

- Community Detection: Algorithms like multiscale community detection can be applied to the module to identify finer-grained, pathway-level substructures [12].

Applications in Disease Research and Drug Development

Elucidating Shared Biology Between Comorbid Diseases

Network medicine can reveal molecular mechanisms underlying disease comorbidity. A protocol termed NetColoc uses network propagation to measure the distance between gene sets for different diseases [12]. For diseases that are colocalized in the interactome, common gene communities can be extracted. This approach successfully identified a convergent molecular network underlying autism spectrum disorder and congenital heart disease, suggesting shared developmental pathways [12].

De Novo Drug Design via Interactome Learning

The interactome provides a foundation for advanced AI-driven drug discovery. The DRAGONFLY framework uses a deep learning model trained on a drug-target interactome graph, where nodes represent ligands and protein targets, and edges represent high-affinity interactions [13].

Methodology:

- Interactome Construction: Compile a graph of ~360,000 ligands and ~3,000 targets with annotated bioactivities from databases like ChEMBL.

- Model Architecture: A Graph Transformer Neural Network encodes molecular graphs (of ligands or 3D protein binding sites), and a Long-Short Term Memory network decodes these into novel SMILES strings.

- Zero-Shot Generation: The model generates novel drug-like molecules tailored for specific bioactivity, synthesizability, and structural novelty without requiring application-specific fine-tuning.

This method was prospectively validated by generating new partial agonists for the Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma (PPARγ), with top designs synthesized and confirmed via crystal structure to have the anticipated binding mode [13].

Drug Repurposing and Polypharmacology

Network medicine rationalizes drug repurposing by analyzing a drug's position relative to disease modules. A drug's therapeutic effect is often the result of its action on multiple proteins within a disease module. Analyzing the "distance" between a drug's protein targets and a disease module can predict its efficacy [10]. Furthermore, charting the rich trove of drug-target interactions—averaging 25 targets per drug—dramatically expands the usable drug space and offers repurposing opportunities [10].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Interactome Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORFeome Collections | Biological Reagent | Provides full sets of open reading frames (ORFs) for model organisms and human genes. | Enables high-throughput interactome mapping assays like yeast two-hybrid screens [9]. |

| Affinity Purification-Mass Spectrometry (AP-MS) | Experimental Protocol | Identifies physical protein-protein interactions for a specific bait protein. | Identifying 96 novel interactors of the COPD-associated protein FAM13A [11]. |

| STRING / BioGRID | Database | Provides a curated reference network of known protein-protein interactions. | Serves as the scaffold for mapping seed genes and running network algorithms [12]. |

| NetColoc Software | Computational Tool | Implements network propagation and colocalization analysis for two disease gene sets. | Identifying shared network communities between two phenotypically related diseases [12]. |

| Cytoscape | Software Platform | An open-source platform for visualizing complex networks and integrating with attribute data. | Visualization and analysis of disease modules; supports community detection plugins [12]. |

| DRAGONFLY | AI Model | An interactome-based deep learning model for de novo molecular design. | Generating novel, synthetically accessible PPARγ agonists with confirmed bioactivity [13]. |

The paradigm that "networks matter" is fundamentally reshaping biomedical research. The consistent finding that disease genes cluster in the interactome provides a powerful, unbiased scaffold for moving beyond the limitations of reductionism. The methodologies outlined—from network propagation and data integration to AI-based drug design—provide researchers with a concrete toolkit for discovering new disease genes, unraveling shared pathobiology, and accelerating the development of precise therapeutics. The interactome, though still incomplete, has emerged as an essential map for navigating the complexity of human disease.

Network proximity measures have emerged as fundamental computational tools in systems biology, enabling researchers to move beyond simple correlative relationships to infer causal biological mechanisms. By quantifying the topological relationship between biomolecules within complex interaction networks, these measures facilitate the prioritization of disease genes, the identification of functional modules, and the discovery of novel drug targets. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of network proximity concepts, their mathematical underpinnings, and their practical applications in disease research and therapeutic development. We present quantitative validations of these approaches, detailed experimental methodologies for their implementation, and visualization of key workflows, thereby offering researchers a comprehensive framework for leveraging interactome analysis in biomedical discovery.

Molecular interaction networks provide a structural framework for representing the complex interplay of biomolecules within cellular systems. The fundamental premise of network proximity is that the topological relationship between genes or proteins in these networks reflects their functional relationship and potential involvement in shared disease mechanisms [14]. This principle of "guilt-by-association" has been instrumental in shifting from a reductionist view of disease causality toward a systems-level understanding where diseases arise from perturbations of interconnected cellular systems rather than isolated molecular defects [15] [16].

The transition from correlation to causation in network biology hinges on the observation that disease-associated proteins often reside in the same network neighborhoods [15]. This non-random distribution enables the computational inference of novel disease genes through network proximity measures, even in the absence of direct genetic evidence [16]. The biological significance of this approach is underscored by empirical studies showing that proteins with high proximity to known disease-associated proteins are enriched for successful drug targets, validating the causal implications of network positioning [16].

Table 1: Key Network Proximity Measures and Their Applications

| Proximity Measure | Mathematical Basis | Primary Applications | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Walk with Restarts (RWR) | Simulates information flow with probability of returning to seed nodes | Disease gene prioritization, Functional annotation | Identifies regions of network frequently visited from seed nodes |

| Network Propagation | Models diffusion processes through network edges | Identification of disease modules, Drug target discovery | Reveals areas of influence surrounding seed proteins |

| Topological Similarity | Compares network connectivity patterns | Functional prediction, Complex identification | Detects proteins with similar interaction patterns |

| Diffusion State Distance | Measures multi-hop connectivity differences | Comparative interactome analysis, Phenotype mapping | Quantifies overall topological relationship between nodes |

Network Proximity in Disease Gene Discovery and Drug Target Identification

Theoretical Foundations and Mechanisms

Network proximity measures operate on the principle that the functional relatedness of biomolecules is reflected in their interconnectivity within molecular networks [14]. When a set of "seed" proteins known to be associated with a particular disease is identified, the proximity of other proteins to this seed set in the interactome provides evidence for their potential involvement in the same disease process [14] [15]. This approach effectively amplifies genetic signals by propagating evidence through biological networks, serving as a "universal amplifier" for identifying disease associations that might otherwise remain undetected due to limitations in study power or design [16].

The linearity property of many network proximity measures is particularly important for their practical application. This property means that the proximity of a node to a set of seed nodes can be represented as an aggregation of its proximity to the individual nodes in the set [14]. This enables efficient computation and indexing of proximity information, facilitating rapid queries and large-scale analyses. From a biological perspective, linearity allows for the decomposition of complex disease associations into contributions from individual molecular components, supporting more nuanced mechanistic interpretations.

Empirical Validations and Therapeutic Applications

Multiple studies have provided empirical validation for network proximity approaches in disease gene discovery and drug development. A systematic analysis of 648 UK Biobank GWAS studies demonstrated that network propagation of genetic evidence identifies proxy genes that are significantly enriched for successful drug targets [16]. This finding confirms that network proximity can effectively bridge the gap between genetic associations and therapeutically relevant mechanisms.

The clinical relevance of these approaches is further supported by historical data on drug development programs. Targets with direct genetic evidence succeed in Phase II clinical trials 73% of the time compared to only 43% for targets without such evidence [14]. Notably, while only 2% of preclinical drug discovery programs focus on genes with direct genetic links, these account for 8.2% of approved drugs, indicating their higher probability of success [16]. Network proximity methods extend this advantage by identifying proxy targets that share network locality with direct genetic hits, thereby expanding the universe of therapeutically targetable mechanisms.

Table 2: Drug Target Success Rates Based on Genetic Evidence

| Evidence Type | Phase II Success Rate | Representation in Approved Drugs | Example Network Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Genetic Evidence | 73% [16] | 8.2% [16] | High-confidence genetic hits (HCGHs) |

| Network Proxy Genes | Enriched for success [16] | 93.8% of targets lack direct evidence [16] | Random walk, Network propagation |

| No Genetic Evidence | 43% [16] | NA | Conventional target discovery |

Quantitative Analysis of Network Proximity Performance

Systematic evaluation of network proximity measures has yielded quantitative insights into their performance characteristics and optimal implementation parameters. Studies examining the efficiency of computing set-based proximity queries have demonstrated that sparse indexing schemes based on the linearity property can drastically improve computational efficiency without compromising accuracy [14]. This is particularly valuable for large-scale analyses across multiple diseases and network types.

The statistical characterization of network proximity scores has revealed important considerations for assessing their significance. Research indicates that the choice of the number of Monte Carlo simulations has a significant effect on the accuracy of figures computed via this method [14]. While estimates based on a small number of simulations diverge significantly from actual values, robust estimates emerge when a sufficient number of simulations is used. This underscores the importance of proper parameterization in computational implementations.

Analysis of different biological network types has provided insights into their relative utility for specific applications. Protein networks formed from specific functional linkages such as protein complexes and ligand-receptor pairs have been shown to be suitable for guilt-by-association network propagation approaches [16]. More sophisticated methods applied to global protein-protein interaction networks and pathway databases also successfully retrieve targets enriched for clinically successful drug targets, demonstrating the versatility of network-based approaches across different biological contexts.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Network-Based Disease Gene Prioritization Using Random Walk with Restarts

The following protocol outlines the steps for implementing Random Walk with Restarts (RWR) for disease gene prioritization, a method shown to be effective for identifying proteins in dense network regions surrounding seed nodes [14].

Step 1: Network Construction and Preparation

- Compile a comprehensive protein-protein interaction network from curated databases (e.g., BioGRID, STRING, HPRD)

- Represent the network as an adjacency matrix A where Aᵢⱼ = 1 if proteins i and j interact, 0 otherwise

- Normalize the adjacency matrix to create a column-stochastic transition matrix W

Step 2: Seed Set Definition

- Define the set S of seed proteins with known disease associations

- Create an initial probability vector p₀ where p₀(i) = 1/|S| if i ∈ S, 0 otherwise

Step 3: Random Walk Iteration

- Iterate the random walk process: pₜ₊₁ = (1 - α)Wpₜ + αp₀

- The parameter α (typically 0.1-0.3) represents the restart probability, controlling the balance between local exploration and return to seed nodes

- Continue iterations until convergence (||pₜ₊₁ - pₜ|| < ε, where ε is a small threshold, e.g., 10⁻⁶)

Step 4: Result Interpretation and Validation

- Rank all proteins in the network by their steady-state probability values in p∞

- Validate top-ranking candidates through literature review, functional enrichment analysis, or experimental follow-up

- Assess statistical significance using reference models that account for network topology and seed set characteristics [14]

Protocol 2: Quantitative Interactome Analysis via Chemical Crosslinking Mass Spectrometry (qXL-MS)

Quantitative chemical crosslinking with mass spectrometry (qXL-MS) provides experimental validation of network proximity by directly measuring changes in protein interactions and conformations across biological states [17] [18].

Step 1: Experimental Design and Sample Preparation

- Grow cells under conditions of interest (e.g., drug-sensitive vs. chemoresistant cancer cells) using SILAC (Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino Acids in Cell Culture) for isotopic encoding [18]

- Treat living cells with membrane-permeable crosslinkers (e.g., DSSO, BS3) to capture protein interactions in their native cellular environment

- Quench crosslinking reaction, harvest cells, and prepare protein extracts

Step 2: Sample Processing and Peptide Enrichment

- Digest proteins with trypsin to generate crosslinked peptides

- Enrich crosslinked peptides using affinity purification or size exclusion chromatography

- Fractionate peptides using liquid chromatography to reduce complexity

Step 3: Mass Spectrometry Analysis and Data Acquisition

- Analyze peptides by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

- Use collision-induced dissociation (CID) or higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) to fragment peptides

- For isobaric crosslinkers (e.g., iqPIR), employ multi-stage MS to obtain quantitative information [17]

Step 4: Data Processing and Quantitative Analysis

- Identify crosslinked peptides using database search tools (e.g., MassChroQ, MaxQuant, pQuant)

- Quantify crosslink abundance using MS1 intensity measurements or isobaric reporter ions

- Normalize data across samples and perform statistical analysis to identify significant interaction changes

- Map quantitative changes to protein interaction networks to identify perturbed modules

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Network Proximity Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| SILAC (Stable Isotope Labeling with Amino Acids in Cell Culture) | Metabolic labeling for quantitative proteomics | qXL-MS for interactome dynamics [18] | Enables precise relative quantification between biological states |

| DSSO (Disuccinimidyl Sulfoxide) | MS-cleavable crosslinker | In vivo crosslinking for interaction mapping [17] | Allows tandem MS fragmentation for improved identification |

| BS3-d₀/d₁₂ (Bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate) | Isotope-coded crosslinker | Quantitative structural studies [17] | Provides binary comparison capability via deuterium encoding |

| iqPIR (Isobaric Quantitative Protein Interaction Reporter) | Multiplexed quantitative crosslinker | High-throughput interactome screening [17] | Enables multiplexing of up to 6 samples simultaneously |

| Cytoscape | Network visualization and analysis | Integration and visualization of network proximity results [19] | Open-source platform with extensive plugin ecosystem |

| XLinkDB | Database for crosslinking data | Storage and interpretation of qXL-MS results [17] [18] | Enables mapping of crosslinks to existing protein structures |

Visualization of Network Proximity Concepts and Results

The following diagram illustrates the core concept of network proximity in disease gene identification, showing how proximity measures can identify functionally related modules from initially dispersed seed nodes.

Network proximity measures represent a powerful framework for advancing from correlative observations to causal inferences in biological research. By leveraging the topological properties of molecular interaction networks, these approaches enable the identification of disease-relevant functional modules and therapeutically targetable mechanisms that might otherwise remain obscured by the complexity of biological systems. The quantitative validations presented in this whitepaper, demonstrating enrichment of successful drug targets among proteins with high network proximity to known disease genes, provide compelling evidence for the biological significance of these methods.

Future developments in network biology will likely focus on more dynamic and context-specific implementations of proximity measures, incorporating tissue-specific interactions, temporal changes during disease progression, and multi-omic data integration. As interactome mapping technologies continue to advance, particularly through quantitative approaches like qXL-MS, and computational methods become increasingly sophisticated, network proximity analysis will play an expanding role in translating genomic discoveries into therapeutic insights, ultimately fulfilling the promise of precision medicine through network-based mechanistic understanding.

The traditional view of the cell as a static collection of molecules has been superseded by a dynamic model where cellular function emerges from complex, ever-changing networks of interactions. The interactome—the complete set of molecular interactions within a cell—is not a fixed map but a highly plastic system that undergoes significant rewiring in response to developmental cues, environmental stimuli, and, critically, during the onset and progression of disease [20] [21]. For researchers focused on disease gene discovery, understanding this dynamism is paramount. It moves the inquiry beyond identifying static lists of differentially expressed genes or proteins toward deciphering how the rewiring of protein-protein interactions (PPIs) drives pathological phenotypes and creates novel therapeutic vulnerabilities [21] [22]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the principles, methods, and analytical frameworks for studying interactome dynamics, positioning this knowledge within the critical context of discovering novel disease-associated genes and targets.

Core Principles: Why Interactome Dynamics Matter for Disease

Protein interaction networks are fundamentally reshaped during cellular state transitions. A seminal concept in network medicine is that proteins associated with similar diseases tend to cluster within localized neighborhoods or "disease modules" in the interactome [23] [24]. This topological principle provides a powerful framework for candidate gene prioritization. When a cell enters a disease state, such as senescence or transformation, these modules are not merely activated; they are reconfigured. Interactions are gained, lost, or altered in strength, stabilizing new pathological programs. For instance, in cellular senescence, interactomics has revealed dynamic rewiring that stabilizes DNA damage response hubs, restructures the nuclear lamina, and regulates the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) [21] [22]. These changes are driven not by single molecules but by the collective behavior of the network. Therefore, mapping the context-specific interactome—the network state unique to a disease condition—becomes essential for moving from correlation to causation in disease gene discovery [24].

Quantitative Methodologies for Mapping Dynamic PPIs

Capturing the transient and condition-specific nature of PPIs requires advanced quantitative proteomics coupled with clever experimental design.

Affinity Purification Quantitative Mass Spectrometry (AP-QMS)

AP-MS remains a cornerstone for identifying components of protein complexes. Quantitative versions (AP-QMS) use stable isotope labeling to distinguish specific interactors from non-specific background [25]. Two primary strategies govern sample preparation:

- Purification After Mixing (PAM): Cell lysates from differentially labeled conditions (e.g., bait-expressing vs. control) are mixed before affinity purification. This minimizes experimental variation during purification. SILAC metabolic labeling is typically used [25].

- Mixing After Purification (MAP): Affinity purifications are performed separately on different samples, and the eluates are mixed after purification for MS analysis. This offers flexibility for using any stable isotope labeling method (SILAC, iTRAQ, TMT) and is crucial for studying weak or transient interactions that might be lost in a mixed lysate [25].

Proximity-Dependent Labeling (BioID/TurboID)

This method overcomes limitations of AP-MS related to capturing weak, transient, or membrane-associated interactions. A bait protein is fused to a promiscuous biotin ligase (e.g., BioID or the faster TurboID). In living cells, the enzyme biotinylates proximate proteins, which can then be captured and identified by streptavidin purification and MS. This provides a snapshot of the in vivo interaction environment over time, ideal for mapping dynamic interactions in pathways like DNA damage response [20] [21].

Proximity Ligation Imaging Cytometry (PLIC) for Rare Populations

Studying interactome dynamics in rare, primary cell populations (e.g., specific immune cells, stem cells) is challenging. PLIC combines Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA) with Imaging Flow Cytometry (IFC). PLA uses antibody pairs with DNA oligonucleotides to generate an amplified fluorescent signal only when two target proteins are within <40 nm. IFC allows this signal to be quantified and its subcellular localization analyzed in thousands of single cells in suspension, defined by multiple surface markers. This enables high-resolution, quantitative analysis of PPIs and post-translational modifications in rare populations directly ex vivo [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Interactome Dynamics Studies

| Reagent/Method | Core Function | Key Application in Dynamics |

|---|---|---|

| Tandem Affinity Purification (TAP) Tags | Allows two-step purification under native conditions to increase specificity. | Isolating stable core complexes with minimal background for structural studies [20]. |

| Stable Isotope Labeling (SILAC, iTRAQ/TMT) | Enables accurate multiplexed quantification of proteins across samples. | Distinguishing condition-specific interactors from background in AP-QMS and quantifying interaction changes [25]. |

| TurboID / APEX2 Enzymes | Engineered promiscuous biotin ligases for rapid in vivo proximity labeling. | Mapping transient interactions and microenvironment neighborhoods in living cells under different stimuli [21]. |

| PLA Probes & Kits | Antibody-conjugated DNA oligonucleotides for in situ detection of proximal proteins. | Validating PPIs and their subcellular localization in fixed cells or tissues; foundational for PLIC [26]. |

| Cross-linking Mass Spectrometry (XL-MS) Reagents | Chemical crosslinkers (e.g., DSSO) that covalently link interacting proteins. | Capturing and stabilizing transient interaction interfaces for structural insight into complex dynamics [21]. |

| Validated PPI Antibody Panels | High-specificity antibodies for a wide range of target proteins. | Essential for immunoaffinity purification, PLA, and Western blot validation across experimental conditions. |

Network Analytics: From Static Maps to Dynamic Predictions

Once context-specific PPI data is generated, sophisticated computational analyses are required to extract biological meaning and prioritize disease genes.

Global Network Algorithms for Gene Prioritization

Early methods relied on local network properties, such as looking for direct interactors of known disease genes. Superior performance is achieved with global network algorithms like Random Walk with Restart (RWR) and Diffusion Kernel methods [23]. These algorithms simulate a "walker" moving randomly through the network from known disease seed genes. Its steady-state probability distribution over all nodes ranks candidate genes by their network proximity to the disease module, effectively capturing both direct and indirect functional associations. This method significantly outperformed local measures, achieving an Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) of up to 98% in prioritizing disease genes within simulated linkage intervals [23].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Gene Prioritization Methods on Disease-Gene Families [23]

| Method | Principle | Mean Performance (Enrichment Score)* |

|---|---|---|

| Random Walk / Diffusion Kernel | Global network distance/similarity measure. | 25.9 |

| ENDEAVOUR | Data fusion from multiple genomic sources. | 18.4 |

| Shortest Path (SP) | Minimum path length to any known disease gene. | 17.2 |

| Direct Interaction (DI) | Physical interaction with a known disease gene. | 12.8 |

| PROSPECTR (Sequence-Based) | Machine learning on sequence features (e.g., gene length). | 10.9 |

*Higher score indicates better ranking of true disease genes within a candidate list.

Integrating Co-Expression with Interactome Topology

Gene co-expression networks derived from RNA-seq data are inherently context-specific but lack physical interaction data. Integrating them with the canonical interactome bridges this gap. The SWItch Miner (SWIM) algorithm identifies critical "switch genes" within a co-expression network that govern state transitions (e.g., healthy to diseased) [24]. When these switch genes are mapped onto the human interactome, they form localized, connected subnetworks that overlap for similar diseases and are distinct for different diseases. This SWIM-informed disease module provides a powerful, context-aware filter for identifying novel candidate disease genes within an interactome neighborhood [24].

Predicting Higher-Order Interaction Dynamics

Most networks model binary interactions. However, understanding cooperative (proteins A and B bind simultaneously to C) versus competitive (A and B compete for the same site on C) relationships within triplets is key for mechanistic insight. A computational framework embedding the human PPI network into hyperbolic space can classify triplets. Using topological and geometric features (angular distances in hyperbolic space are key), a Random Forest classifier achieved an AUC of 0.88 in distinguishing cooperative from competitive triplets. This was validated by AlphaFold 3 modeling, showing cooperative partners bind at distinct sites [27].

Table 3: Hyperbolic Embedding & Triplet Classification Results [27]

| Metric | Description | Value / Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Network Size (High-Confidence) | Proteins & Interactions after confidence filtering (HIPPIE ≥0.71). | 15,319 proteins, 187,791 interactions |

| Structurally Annotated Cooperative Triplets | Non-redundant triplets from Interactome3D used as positive class. | 211 triplets |

| Key Predictive Feature | Most important for classifier performance. | Angular distance in hyperbolic space |

| Model Performance (AUC) | Random Forest classifier performance. | 0.88 |

| Paralog Enrichment | Biological insight for cooperative triplets. | Paralogous partners often bind a common protein at non-overlapping sites |

Diagram 1: Interactome Dynamics in Disease Gene Discovery Workflow (99 chars)

Diagram 2: Key Experimental Methods for Dynamic PPI Mapping (97 chars)

Diagram 3: Network-Based Prioritization via Random Walk (99 chars)

The study of interactome dynamics represents a paradigm shift in disease research. By moving from static catalogs to condition-specific networks, researchers can identify the functional rewiring events that are causal to disease phenotypes. The integration of advanced quantitative proteomics (AP-QMS, proximity labeling), specialized protocols for challenging systems (PLIC), and sophisticated network analytics (global algorithms, integration with transcriptomics, higher-order prediction) creates a powerful pipeline for disease gene discovery. This approach not only prioritizes candidate genes within loci from linkage studies with high accuracy [23] but also reveals the mechanistic underpinnings of how those genes, through their altered interactions, drive pathology. As these methods mature and are integrated with single-cell and spatial technologies, they promise to decode the network-based origins of disease with unprecedented precision, guiding the development of targeted network-modulating therapies.

Mapping the Cellular Wiring Diagram: Experimental and Computational Approaches

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) represent the fundamental framework of cellular processes, forming intricate networks that dictate biological function and dysfunction. The comprehensive mapping of these interactions, known as the interactome, has become crucial for understanding molecular mechanisms in health and disease [28]. The limitations of traditional methods like yeast two-hybrid systems—including high false-positive rates, inability to detect transient interactions, and constraints of studying proteins in non-native environments—have driven the development of more sophisticated in vivo approaches [28]. Among these, Affinity Purification Mass Spectrometry (AP-MS), TurboID-mediated proximity labeling, and Cross-Linking Mass Spectrometry (XL-MS) have emerged as powerful high-throughput techniques that enable system-wide charting of protein interactions to unprecedented depth and accuracy [28]. When applied to disease gene discovery, these methods provide critical functional context for genetic findings by revealing how disease-associated proteins assemble into complexes and pathways, offering insights into pathological mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets [4] [29].

Technical Foundations and Methodologies

Affinity Purification Mass Spectrometry (AP-MS)

Principles and Applications AP-MS is a robust technique for elucidating protein interactions by coupling affinity purification with mass spectrometry analysis. In a typical AP-MS workflow, a tagged molecule of interest (bait) is selectively enriched along with its associated interaction partners (prey) from a complex biological sample using an affinity matrix, such as an antibody against a specific bait or tag [28]. The bait-prey complexes are subsequently washed with high stringency to remove non-specifically bound proteins, then eluted and digested into peptides for liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis [28]. This approach allows researchers to identify prey proteins associated with a particular bait, with computational analysis distinguishing true interactors from background contaminants.

A critical decision in AP-MS experimental design involves selecting between antibodies against endogenous proteins or tagged proteins for affinity purification. While antibodies against endogenous proteins enable study of proteins in their native state, they can be challenging to generate with high specificity [28]. Tagging the bait protein allows for more standardized purification but introduces its own challenges, particularly regarding protein expression levels. Researchers must choose between overexpression of tagged proteins or endogenous tagging using genome editing techniques like CRISPR-Cas9. Overexpression can lead to non-physiological protein levels and artifacts, while CRISPR-Cas9-mediated endogenous tagging maintains native expression levels despite being technically more challenging [28].

Protocol: AP-MS for Protein Complex Isolation

Cell Lysis and Preparation: Harvest and lyse cells using appropriate lysis buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, plus protease and phosphatase inhibitors) to maintain protein interactions while minimizing non-specific binding [28] [30].

Affinity Purification: Incubate cell lysate with affinity matrix (antibody-conjugated beads or tag-specific resin) for 1-2 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation [30]. For immunoprecipitation, use Protein A/G magnetic beads bound to specific antibody complexed with target antigen [30].

Washing: Pellet beads and wash multiple times with high-stringency wash buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS) to remove non-specifically bound proteins while preserving true interactions [28].

Elution: Elute bound proteins using competitive analytes (e.g., excess peptide for antibody-based purification), low pH buffer, or reducing conditions compatible with downstream MS analysis [30].

Sample Processing for MS: Digest purified proteins either on-bead or after elution using trypsin, then label with tandem mass tags (TMT) or prepare for label-free quantitation [28].

LC-MS/MS Analysis: Analyze resulting peptides via liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry to identify interacting proteins [28].

Table 1: Key Considerations for AP-MS Experimental Design

| Factor | Options | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bait Capture | Antibodies against endogenous proteins | Studies proteins in native state | Challenging to generate high-specificity antibodies |

| Tagged proteins | Standardized purification | Potential overexpression artifacts | |

| Tagging Approach | Overexpression | Technically straightforward | Non-physiological protein levels |

| Endogenous tagging (CRISPR-Cas9) | Maintains native expression | Technically challenging | |

| Quantitation | Label-free | Cost-effective, straightforward | Less precise for complex samples |

| Tandem Mass Tags (TMT) | Multiplexing capability, precise quantitation | Ratio compression issues |

TurboID-Mediated Proximity Labeling

Principles and Applications Proximity labeling-mass spectrometry (PL-MS) has emerged as a powerful alternative to traditional interaction methods, enabling identification of protein-protein interactions, protein interactomes, and even protein-nucleic acid interactions within living cells [31]. TurboID, an engineered biotin ligase, catalyzes the covalent attachment of biotin to proximal proteins within a limited radius (typically 10-20 nm) when genetically fused to a bait protein and expressed in living cells [31] [32]. Through directed evolution, TurboID has substantially higher activity than previously described biotin ligases like BioID, enabling higher temporal resolution and broader application in vivo [32]. The biotinylated proteins are subsequently selectively captured through affinity purification using streptavidin-coated beads, followed by enzymatic digestion and LC-MS/MS analysis to characterize the bait protein's interactome [31].

TurboID offers significant advantages for mapping interactions in native cellular environments, particularly for capturing transient or weak interactions that traditional co-IP-MS struggles to detect [31]. Split-TurboID, consisting of two inactive fragments of TurboID that can be reconstituted through protein-protein interactions or organelle-organelle interactions, provides even greater targeting specificity than full-length enzymes alone [32]. This approach has proven valuable for mapping subcellular proteomes and studying the spatial organization of protein networks in live mammalian cells [32] and plant systems [31].

Protocol: TurboID Proximity Labeling in Arabidopsis

Plant Preparation and Biotin Treatment:

- Prepare transgenic plants expressing Bait-TurboID fusion protein and appropriate controls (e.g., YFP-TurboID localized to same subcellular compartment) [31].

- Grow seedlings for 7-10 days under controlled conditions (22-23°C, 16h light/8h dark cycle).

- Harvest seedlings and incubate in 50 μM biotin solution for 3 hours to enable proximity-dependent biotinylation [31].

Protein Extraction and Biotin Desalting:

- Grind plant tissues in liquid nitrogen and extract with cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton-X-100, 0.5% SDC, protease inhibitors) [31].

- Sonicate lysate and centrifuge to remove debris.

- Desalt protein extract using PD-10 desalting columns to remove free biotin that could interfere with streptavidin binding [31].

Affinity Purification:

- Incubate desalted protein extracts with Streptavidin magnetic beads for several hours or overnight with gentle mixing [31].

- Wash beads sequentially with buffers of increasing stringency:

- 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.5) with 2% SDS

- 50 mM Tris buffer with 150 mM NaCl, 0.4% SDS, 1% Triton-X-100 (repeat twice)

- 1 M KCl

- 0.1 M Na₂CO₃

- 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate solution [31]

On-Bead Digestion and LC-MS/MS:

- Add digestion buffer (100 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.5, 0.5% SDC, and 0.5% SLS) to washed beads.

- Digest with trypsin to generate peptides for LC-MS/MS analysis [31].

- Identify biotinylated proteins through database searching of MS data.

Figure 1: TurboID Proximity Labeling Workflow for Interactome Mapping

Cross-Linking Mass Spectrometry (XL-MS)

Principles and Applications Cross-linking mass spectrometry (XL-MS) is unique among MS-based techniques due to its capability to simultaneously capture protein-protein interactions from their native environment and uncover their physical interaction contacts, permitting determination of both identity and connectivity of protein-protein interactions in cells [33]. In XL-MS, proteins are first reacted with bifunctional cross-linking reagents that physically tether spatially proximal amino acid residues through covalent bonds [33]. The cross-linked proteins are enzymatically digested, and resulting peptide mixtures are analyzed via LC-MS/MS. Subsequent database searching of MS data identifies cross-linked peptides and their linkage sites, providing distance constraints (typically 20-30 Å, depending on the cross-linker) that can be utilized for various applications ranging from structure validation and integrative modeling to de novo structure prediction [33].

XL-MS provides structural insights by stabilizing interactions via chemical cross-linkers for distance restraints critical for understanding both spatial relationships and interaction domains [28]. This technique has proven particularly valuable for studying large and dynamic protein complexes that have proven recalcitrant to traditional structural methods like X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy [33]. Recent technological advancements in XL-MS have dramatically propelled the field forward, enabling a wide range of applications in vitro and in vivo, not only at the level of protein complexes but also at the proteome scale [33].

Protocol: XL-MS for Interaction Mapping

Cross-Linking Reaction:

- React purified protein complexes or cell lysates with homobifunctional cross-linkers (e.g., DSSO, BS3) that target primary amines (lysine residues) or other reactive groups [33].

- Optimize cross-linker concentration and reaction time to maximize specific cross-links while minimizing non-specific conjugation.

Quenching and Digestion:

- Quench cross-linking reaction with appropriate quenching agents (e.g., ammonium bicarbonate for amine-reactive cross-linkers).

- Digest cross-linked proteins with specific proteases (typically trypsin) to generate peptide mixtures [33].

Peptide Separation and Enrichment:

- Separate and potentially enrich cross-linked peptides from complex peptide mixtures using fractionation or affinity-based methods.

- Utilize cleavable cross-linkers to facilitate simplified MS/MS fragmentation and identification [33].

LC-MS/MS Analysis and Data Processing:

- Analyze peptides via liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry using instruments capable of high mass accuracy and resolution.

- Use specialized software (e.g., pLink, xQuest/xProphet, Kojak) to identify cross-linked peptides from complex MS/MS data [33].

- Apply false discovery rate (FDR) control to ensure identification reliability.

Table 2: Bioinformatics Tools for XL-MS Data Analysis

| Software | Cross-linker Compatibility | Key Features | Identification Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| pLink | Non-cleavable, Cleavable | FDR estimation, High-throughput capability | Treats cross-links as large modifications |

| xQuest/xProphet | Non-cleavable, Isotope-labeled | Isotope-based pre-filtering, FDR control | Reduces search space through pre-filtering |

| Kojak | Non-cleavable, Cleavable | Fast search algorithm, FDR control | Heuristic approaches to minimize search space |

| StavroX | Non-cleavable, Cleavable | Mass correlation matching | Compares precursor masses to theoretical cross-links |

| SIM-XL | Non-cleavable, Cleavable | Spectral comparison, Network analysis | Uses dead-end modifications to eliminate possibilities |

Comparative Analysis of Techniques

Each high-throughput technique offers distinct advantages and limitations, making them complementary rather than competitive approaches for interactome mapping. Understanding their respective strengths enables researchers to select the most appropriate method for specific biological questions or to integrate multiple approaches for comprehensive interaction mapping.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of High-Throughput Interaction Techniques

| Parameter | AP-MS | TurboID | XL-MS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Limited to co-purifying complexes | ~10-20 nm radius from bait | Atomic (specific residues) |

| Interaction Type | Stable complexes | Proximal proteins (direct and indirect) | Direct physical contacts |

| Temporal Resolution | Endpoint measurement | Configurable (minutes to hours) | Endpoint measurement |

| Native Environment | Requires cell lysis | In living cells | Can be performed in vitro or in vivo |

| Transient Interactions | Limited detection | Excellent capture | Excellent stabilization |

| Structural Information | None | None | Distance restraints (20-30 Å) |

| Key Challenges | False positives from contamination | Background biotinylation, optimization of expression | Computational complexity, low abundance |

| Ideal Applications | Stable complex identification | Subcellular proteome mapping, weak/transient interactions | Structural modeling, interaction interfaces |

Figure 2: Technique Selection Guide for Different Interaction Types

Integration with Disease Gene Discovery

The application of high-throughput interaction techniques has profound implications for disease gene discovery and functional validation. By mapping physical interactions for disease-associated proteins, researchers can place novel disease genes into functional context, identify previously unrecognized components of pathological pathways, and suggest potential therapeutic targets [4] [29]. Statistical frameworks for rare variant gene burden analysis, when integrated with protein interaction networks, significantly enhance the ability to identify and validate novel disease-gene associations from genomic sequencing data [4].

For rare disease gene discovery, where 50-80% of patients remain undiagnosed after genomic sequencing, protein interaction data can provide critical functional evidence to support variant pathogenicity [4]. When novel candidate genes physically interact with established disease proteins, this interaction evidence substantially increases confidence in their disease association. Furthermore, understanding how disease-associated variants alter protein interactions can reveal mechanistic insights into pathogenesis, potentially identifying points for therapeutic intervention across multiple related disorders.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for High-Throughput Interaction Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity Matrices | Protein A/G Magnetic Beads, Glutathione Sepharose, Streptavidin Beads | Capture and purification of bait-prey complexes or biotinylated proteins |

| Cross-linking Reagents | DSSO, BS3, DSG | Stabilize protein interactions through covalent bonding for XL-MS |

| Proximity Labeling Enzymes | TurboID, BioID, APEX | Catalyze proximity-dependent biotinylation of interacting proteins |

| Proteases | Trypsin, Lys-C | Digest proteins into peptides for MS analysis |

| Mass Spectrometry Tags | Tandem Mass Tags (TMT), Isobaric Tags (iTRAQ) | Enable multiplexed quantitative proteomics |

| Chromatography Columns | C18 columns, PD-10 desalting columns | Peptide separation and sample cleanup |

| Bioinformatics Tools | pLink, xQuest/xProphet, MaxQuant | Identify cross-linked peptides and analyze MS data |

AP-MS, TurboID, and XL-MS represent complementary pillars of modern high-throughput interactome analysis, each offering unique capabilities for mapping protein interactions across different spatial and temporal scales. AP-MS excels at identifying stable protein complexes, TurboID captures proximal interactions in living cells with high temporal resolution, and XL-MS provides structural constraints for modeling interaction interfaces. When integrated with genomic approaches for disease gene discovery, these techniques transform candidate gene lists into functional biological networks, revealing pathological mechanisms and potential therapeutic opportunities. As these methods continue to evolve alongside advances in mass spectrometry instrumentation and computational analysis, they promise to further illuminate the intricate protein interaction networks that underlie both normal physiology and disease states.

Interactome analysis provides a systems-level framework for understanding cellular function and disease mechanisms. This technical guide details the methodology for constructing protein-protein interaction networks (interactomes) using two principal genomic data types: phylogenetic profiles and gene fusion events. Within the context of disease gene discovery, these approaches enable the identification of novel disease modules, elucidate pathogenic rewiring mechanisms in cancer, and facilitate the prioritization of candidate disease genes. We present standardized protocols, analytical workflows, and resource specifications to equip researchers with practical tools for implementing these analyses in both discovery and diagnostic settings.