Network Biology in Autism Spectrum Disorder: From Molecular Mechanisms to Precision Therapeutics

This comprehensive review explores how biological network analysis is transforming our understanding of Autism Spectrum Disorder's complex etiology.

Network Biology in Autism Spectrum Disorder: From Molecular Mechanisms to Precision Therapeutics

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores how biological network analysis is transforming our understanding of Autism Spectrum Disorder's complex etiology. By integrating multi-omics data through advanced computational approaches, researchers are identifying key network modules, convergent pathways, and clinically relevant subtypes that transcend traditional diagnostic boundaries. We examine methodological advances in gene co-expression networks, protein-protein interaction mapping, and machine learning frameworks that enable prioritization of causal genes and pathways. The article addresses critical challenges in network medicine for ASD, including biological heterogeneity and data integration, while highlighting validation strategies and comparative analyses that bridge computational discoveries with clinical applications in biomarker development and targeted therapeutics.

Decoding ASD Complexity: Network Principles and Genetic Architecture

The network paradigm shift in neurodevelopmental disorder research

The study of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs), such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), is undergoing a fundamental transformation. This shift moves away from categorical, symptom-based diagnostic models toward a dimensional, systems-level understanding rooted in biological network analysis [1] [2]. This "network paradigm" posits that the clinical heterogeneity of NDDs arises from variations in the complex interplay within and across multiple biological scales—from genetic and molecular networks to macroscale brain connectomes [1] [3]. Framed within a broader thesis on biological network analysis in ASD research, this approach seeks to decode the shared and distinct network architectures that underlie cognitive variability and symptomatology. The convergence of high-throughput genomics, advanced neuroimaging, and machine learning now allows researchers to model individual-specific "neural fingerprints" and identify reproducible neurobiological subgroups that transcend traditional diagnostic boundaries [1] [2]. This article provides detailed application notes and protocols for implementing this network-centric framework in NDD research, with a focus on translating discoveries into personalized therapeutic strategies.

Application Notes & Protocols

From Group-Averages to Personalized Brain Network (PBN) Architectures

Core Concept: Traditional neuroimaging analyses often obscure critical individual differences by averaging data across groups. The PBN framework leverages connectomics and graph theory to characterize the unique wiring diagram—or "neural fingerprint"—of an individual's brain [1].

Protocol: Individual-Specific Connectome Generation

- Data Acquisition: Acquire high-resolution resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) data. For robust functional connectivity, collect at least 10-15 minutes of low-motion rs-fMRI data [2].

- Preprocessing & Parcellation: Process data using standardized pipelines (e.g., fMRIPrep, QSIPrep) for motion correction, normalization, and denoising. Parcellate the brain into a predefined atlas (e.g., Schaefer 400-parcel) to define network nodes.

- Network Construction: For functional connectivity, calculate pairwise temporal correlations (e.g., Pearson's r) between regional time-series to create a subject-specific functional connectivity matrix. For structural connectivity, use tractography on DTI data to estimate the strength of white matter pathways between regions.

- Graph Analysis: Model the brain as a graph where nodes are brain regions and edges are connection strengths. Compute individual graph metrics (e.g., clustering coefficient, path length, betweenness centrality) using tools like the Brain Connectivity Toolbox or NetSciPy. These metrics quantify the efficiency and integration of an individual's brain network [1].

Transdiagnostic Dimensional Phenotyping via Connectome-Based Predictive Modeling (CPM)

Core Concept: Symptoms exist on a continuum across diagnostic labels. CPM links an individual's whole-brain connectivity pattern directly to dimensional behavioral measures (e.g., social responsiveness, inattention) [2].

Protocol: Connectome-Based Symptom Mapping

- Feature Selection: From the N x N connectivity matrix for all subjects, extract the upper triangle elements (edges) as features.

- Association Testing: For each edge, compute its correlation with the target symptom score (e.g., ADOS severity) across all participants in a discovery sample, using a method like multivariate distance matrix regression (MDMR) to assess whole-brain associations [2].

- Network Identification: Select edges significantly associated with the symptom (p < 0.01, FDR-corrected). Sum the strengths of these edges for each subject to create a "summary network strength" score.

- Validation: Test the predictive power of this summary score in an independent validation sample using linear regression or machine learning models to predict symptom severity.

Integrating Multi-Omic Data with Biological Network Analysis

Core Concept: Genetic risk for NDDs is polygenic and involves dysregulated biological pathways. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) can pinpoint central hubs and modules relevant to disorder etiology [4] [5].

Protocol: PPI Network Construction and Hub Gene Identification

- DEG Identification: From transcriptomic data (e.g., RNA-seq from post-mortem brain tissue or iPSC-derived neurons), identify DEGs between case and control groups using tools like DESeq2 or edgeR (adjusted p-value < 0.05, |log2FC| > 0.5).

- Network Retrieval: Input the list of DEGs into the STRING database via its API or Cytoscape's STRING app to retrieve a PPI network with a confidence score threshold (e.g., > 0.4) [5].

- Functional Enrichment: Perform over-representation analysis on genes within the network or its subnetworks for Gene Ontology (GO) terms and KEGG pathways using clusterProfiler or the built-in STRING enrichment tool [4] [5].

- Hub Gene Selection: Calculate network centrality measures (degree, betweenness) within the PPI network using Cytoscape. Integrate machine learning (e.g., Random Forest) on the original expression data to rank genes by importance for classification. Prioritize genes that are both central in the PPI network and important in the Random Forest model as high-confidence candidates [4].

Data Presentation: Key Quantitative Findings from Network-Centric Studies

Table 1: Network-Derived Subgroups in ADHD from Large-Scale Neuroimaging

| Subtype Identifier | Defining Characteristic | Key Network-Level Difference | Source Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delayed Brain Growth ADHD (DBG-ADHD) | Delayed cortical maturation trajectory | Altered functional organization in frontoparietal and default mode networks | Standardized brain charts from >123,000 structural MRI scans [1] |

| Prenatal Brain Growth ADHD (PBG-ADHD) | Accelerated prenatal cortical growth pattern | Distinct functional connectivity profiles compared to DBG-ADHD | Normative modeling of large-scale MRI data [1] |

Table 2: Key ASD-Associated Genes Identified via Integrated Network & Machine Learning Analysis

| Gene Symbol | Random Forest Importance Rank | Primary Associated Biological Function (from Enrichment) | Potential as Biomarker (AUC from ROC analysis) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHANK3 | High | Synaptic scaffolding, postsynaptic density | Not specified in source [4] |

| NLRP3 | High | Immune regulation, inflammasome complex | Not specified in source [4] |

| MGAT4C | High | Protein glycosylation, immune signaling | 0.730 [4] |

| TUBB2A | High | Neuronal microtubule structure, cytoskeleton | Not specified in source [4] |

Table 3: In Vitro Neuronal Network Phenotypes of 15q11.2 Deletion Model

| Phenotype Category | Specific Measurement | Result in 15q11.2 Deletion vs. Control | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural | Neurite Complexity / Length | Decreased | Impaired neuronal arborization and connectivity [6] |

| Cellular Composition | Proportion of Inhibitory Neurons | Increased | Shift in excitation/inhibition balance [6] |

| Functional (MEA) | Multiunit Activity & Bursting | Reduced | Lower overall network activity [6] |

| Functional (MEA) | Network Synchronization | Reduced | Impaired coordinated neural communication [6] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: In Vitro Modeling of Genetic Risk Using iPSC-Derived Neuronal Networks

Objective: To assess the structural and functional consequences of a neurodevelopmental risk copy number variant (CNV) on human neuronal network formation and activity [6].

Detailed Methodology:

- iPSC Culture & Neural Differentiation:

- Maintain control and 15q11.2 deletion carrier iPSC lines in Essential 8 medium on vitronectin-coated plates.

- Differentiate iPSCs into forebrain cortical neural progenitor cells (NPCs) using dual SMAD inhibition (e.g., with LDN193189 and SB431542) in suspension to form embryoid bodies, followed by plating on Matrigel.

- Manually isolate neural rosettes and expand NPCs in N2/B27-containing media with FGF2.

- Neuronal Differentiation & Plating for Assays:

- Dissociate NPCs and plate at defined density (e.g., 50,000 cells/cm²) onto multi-electrode array (MEA) plates pre-coated with poly-D-lysine/laminin for functional assays, or onto imaging plates for structural analysis.

- Culture neurons in neurobasal-based medium supplemented with BDNF, GDNF, and ascorbic acid for 6-8 weeks, with half-medium changes twice weekly.

- Structural Analysis (Confocal Imaging):

- Fix neurons at defined time points (e.g., Day 35, Day 56). Immunostain for MAP2 (neurites), Synapsin (presynaptic terminals), and specific markers for excitatory (vGlut1) and inhibitory (GAD67) neurons.

- Acquire high-resolution z-stack images. Use automated tracing software (e.g., Neurolucida, Filament Tracer) to quantify total neurite length, number of branches, and soma count.

- Functional Analysis (Multielectrode Array - MEA):

- Record spontaneous extracellular action potentials from mature neuronal networks (e.g., from Week 6 onward) using a commercial MEA system.

- Record for 10-15 minutes per well under baseline conditions. Analyze mean firing rate, bursting activity (bursts per minute, spikes within bursts), and network synchronization metrics (e.g., cross-correlation between electrode pairs).

Protocol B: Transdiagnostic Connectome-Based Symptom Mapping

Objective: To identify shared brain functional connectivity patterns associated with core symptom dimensions across children with ASD and ADHD [2].

Detailed Methodology:

- Participant Phenotyping:

- Recruit children (ages 6-12) with rigorous primary diagnoses of ASD (with/without ADHD) or ADHD without ASD. Exclude individuals with IQ < 65.

- Administer the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS-2) to obtain a calibrated severity score (CSS) for autism symptoms. Administer the Kiddie-SADS or a similar clinician interview to obtain ADHD symptom severity ratings.

- MRI Data Acquisition & Preprocessing:

- Acquire T1-weighted structural and resting-state fMRI (eyes-open) scans on a 3T scanner (e.g., Siemens Prisma). A minimum of 6.5 minutes of low-motion rs-fMRI data is required.

- Preprocess data using a standardized pipeline (e.g., fMRIPrep) including motion correction, slice-time correction, normalization to MNI space, nuisance regression (WM, CSF, global signal, motion parameters), and band-pass filtering (0.008-0.1 Hz).

- Connectome Construction & Multivariate Association Analysis:

- Parcellate the preprocessed fMRI data using a functional atlas (e.g., Shen 268-node). Extract the mean time series from each region.

- Compute a 268 x 268 Pearson correlation matrix for each subject, representing their functional connectome.

- Use Multivariate Distance Matrix Regression (MDMR) to test for a whole-brain association between the matrix of inter-subject connectivity dissimilarities and the autism symptom severity score (ADOS-CSS), while covarying for ADHD rating, age, sex, and site.

- Post-hoc Seed-Based Analysis & Genetic Enrichment:

- Based on MDMR results, define significant regions (nodes) as seeds. Extract the whole-brain connectivity pattern (seed-to-voxel or seed-to-node) for each subject.

- Correlate the strength of specific connections (e.g., between left middle frontal gyrus and posterior cingulate cortex [2]) with symptom scores across the transdiagnostic sample.

- Spatially map the symptom-associated connectivity pattern onto the Allen Human Brain Atlas to extract the expression profile of genes enriched in those regions. Perform enrichment analysis for known ASD/ADHD risk genes.

Mandatory Visualization

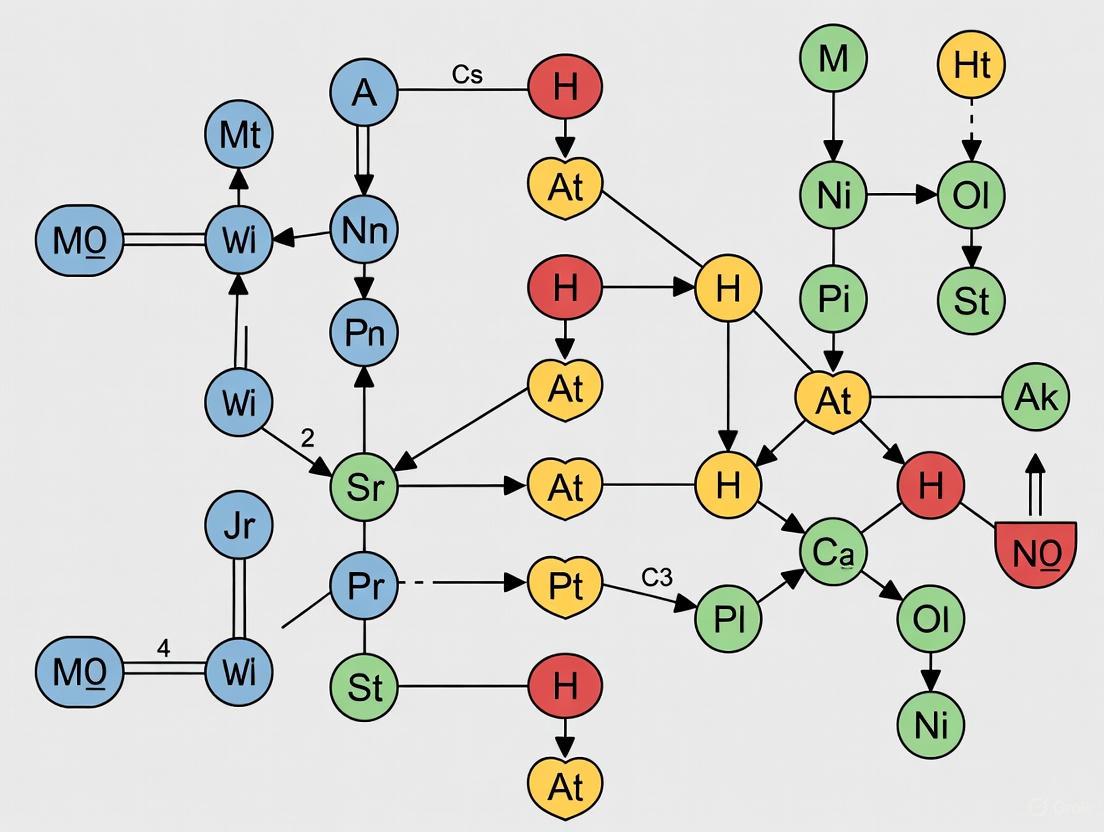

Diagram 1: Integrated Multi-Scale Network Analysis Workflow for NDDs

Diagram 2: Key Signaling Pathways Implicated by Network Analysis in ASD

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Network-Centric NDD Research

| Item / Reagent | Primary Function in Protocol | Key Consideration / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Provides a genetically relevant, human-derived model system to study the impact of NDD risk variants on neuronal development and function. | Use well-characterized lines from repositories (e.g., NIMH Stem Cell Center) or generate from patient fibroblasts. Isogenic controls are ideal. [6] |

| Multi-Electrode Array (MEA) System | Enables non-invasive, long-term, and parallel recording of spontaneous and evoked electrical activity from in vitro neuronal networks, quantifying firing, bursting, and synchronization. | Choose systems with 48-96 wells for throughput. Software for analyzing network burst parameters is critical. [6] |

| STRING Database & Cytoscape | STRING: Curated database of known and predicted Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs). Cytoscape: Open-source platform for visualizing and analyzing molecular interaction networks. | Use STRING for PPI network retrieval and initial enrichment. Use Cytoscape for advanced network visualization, clustering (e.g., MCODE), and hub analysis. [4] [5] |

| Brain Parcellation Atlas | Provides a standardized map to divide the brain into discrete regions (nodes) for consistent network construction across subjects and studies. | Choice affects results. Common atlases include Schaefer (functional), AAL (anatomical), and the HCP-MMP1.0 (multi-modal). [1] [2] |

| Normative Brain Charts | Large-scale, age-specific reference models of brain structure (volume, thickness) and function derived from tens of thousands of scans. Allows identification of individual deviations. | Enables the detection of neurobiological subtypes (e.g., PBG-ADHD) that are invisible to categorical diagnosis. Data from initiatives like UK Biobank are crucial. [1] |

| Conditional Variational Autoencoder (cVAE) / Generative Models | A machine learning architecture capable of synthesizing an individual's predicted brain connectome from non-imaging features (age, genetics) or augmenting limited datasets. | Facilitates data sharing privacy and enables precision medicine approaches by predicting individual-level network phenotypes. [1] |

| Connectivity Map (CMap) | A resource that links gene expression changes induced by small molecules to disease signatures. Used for in silico drug repurposing predictions. | After identifying a disease-associated gene expression signature (e.g., from PPI hub genes), query CMap to find compounds that may reverse it. [4] |

The understanding of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has evolved from a focus on individual genes to a systems-level analysis of complex biological networks. ASD is characterized by impairments in reciprocal social interaction and communication, and by restricted and repetitive behaviors, with a current estimated global prevalence of approximately 1–2% [7] [8]. Family and twin studies have consistently demonstrated a strong genetic component, with concordance rates of 70–90% in monozygotic twins compared to up to 30% in dizygotic twins [8]. Early genetic studies focused primarily on identifying single genes of large effect, but recent research has revealed a vastly more complex architecture involving hundreds of risk genes interacting through sophisticated biological networks. This application note explores this evolving genetic landscape and provides detailed methodologies for investigating ASD genetic architecture, emphasizing the integration of network analysis approaches to uncover convergent pathways and potential therapeutic targets.

The Spectrum of Genetic Risk in ASD

Genetic risk for ASD spans a continuum from rare, high-penetrance variants to common inherited polymorphisms, each contributing to disease susceptibility through potentially distinct yet overlapping biological mechanisms.

Table 1: Categories of Genetic Risk Factors in ASD

| Variant Category | Prevalence in ASD | Key Examples | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rare De Novo CNVs | 5–10% [7] | 16p11.2 deletions/duplications, 15q11-q13 duplications [8] | Affect multiple genes with synaptic functions; often associated with macrocephaly (deletion) or microcephaly (duplication) [8] |

| Rare Inherited Variants | Significant contribution in multiplex families [9] | 7 newly identified risk genes from multiplex family WGS [9] | Often show combinatorial effects with polygenic risk; reduced penetrance in parents [9] |

| Syndromic Monogenic | 5–10% [8] | FMR1 (Fragile X), TSC1/2 (Tuberous Sclerosis) [8] | Disrupt regulators of gene expression affecting multiple downstream pathways |

| Common Polygenic Risk | ~50% of genetic risk [9] | Numerous SNPs identified through GWAS [10] [9] | Individual small effects that collectively contribute significantly to risk |

| Chromosomal Abnormalities | 2–5% [8] | 15q11q13 duplication (1–3%) [8] | Large structural rearrangements detectable by karyotyping |

Recent evidence from whole-genome sequencing of multiplex families (families with multiple autistic children) has revealed a significant role for rare inherited protein-truncating variants in known ASD risk genes [9]. Furthermore, ASD polygenic score (PGS) is overtransmitted from nonautistic parents to autistic children who harbor rare inherited variants, suggesting combinatorial effects that may explain reduced penetrance in parents [9]. These findings support an additive complex genetic risk architecture involving both rare and common variation.

Network Analysis of ASD Genetic Architecture

Protein-Protein Interaction Networks in Human Neurons

Recent advances in proteomics have enabled the mapping of protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks for ASD risk genes in biologically relevant cellular contexts. A landmark study by Pintacuda et al. generated PPI networks in human stem-cell-derived neurogenin-2 induced excitatory neurons (iNs) for 13 high-confidence ASD risk genes [11]. This work identified over 1,000 interactions, approximately 90% of which were previously unreported, emphasizing the importance of cell-type-specific protein interactions [11].

Table 2: Key Findings from Neuronal Protein Interaction Studies

| Aspect | Finding | Research Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Novel Interactions | ~90% of >1,000 identified interactions were novel [11] | Most neurally relevant PPIs were missing from previous databases derived from non-neural tissues |

| Central Connectors | Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins (IGF2BP1-3) formed a highly interconnected m6A-reader complex [11] | Potential convergence point for multiple ASD risk pathways |

| Isoform-Specific Interactions | ANK2 giant exon (exon 37) required for numerous disease-relevant interactions [11] | Critical role for neuron-specific isoforms in ASD pathophysiology |

| Network Connectivity | SFARI genes form a highly connected cluster in causal networks (p = 3×10⁻⁷) [12] | Supports pathway-level convergence despite genetic heterogeneity |

Protocol: Protein-Protein Interaction Mapping in Human Neurons

Application: Identification of novel protein interactions for ASD risk genes in human neuronal models.

Materials:

- Human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)

- Neurogenin-2 (NGN2) expression system for differentiation to excitatory neurons

- Immunoprecipitation-competent antibodies against ASD risk proteins

- Liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) system

- Western blotting apparatus for validation

Procedure:

- Differentiation to Induced Excitatory Neurons:

- Generate NGN2-induced excitatory neurons (iNs) from human iPSCs using established protocols [11].

- Culture neurons for 3-5 weeks to allow maturation and expression of neuronal protein networks.

Protein Complex Immunoprecipitation:

- Lyse cells using mild lysis buffer (e.g., 1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0) to preserve protein complexes.

- Incubate lysates with validated antibodies against ASD risk proteins (e.g., DYRK1A, PTEN) overnight at 4°C.

- Capture immune complexes using protein A/G beads during 2-hour incubation at 4°C.

- Wash beads extensively with lysis buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

Protein Identification and Quantification:

- Elute bound proteins from beads using low-pH buffer or direct digestion with trypsin.

- Analyze peptides via LC-MS/MS using a high-resolution mass spectrometer.

- Process raw data using standard proteomics software (MaxQuant, Proteome Discoverer).

- Identify specific interactors versus contaminants using control IPs.

Validation Experiments:

- Confirm key interactions using western blotting of reciprocal IPs.

- Assess functional consequences of interactions through CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of specific genes followed by proteomic analysis.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Include isotype control antibodies to identify non-specific binders.

- Use multiple biological replicates to ensure reproducibility.

- For transmembrane proteins like ANK2, optimize lysis conditions to maintain solubility while preserving interactions.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for mapping protein-protein interactions (PPIs) in human induced neurons. Key steps include differentiation of iPSCs to neurons, immunoprecipitation of protein complexes, mass spectrometry analysis, and network construction followed by validation.

Causal Network Analysis for ASD Gene-Phenotype Relationships

Beyond physical interactions, causal network analysis aims to map directional relationships between genes, proteins, and phenotypic outcomes. The SIGNOR (SIGnaling Network Open Resource) database employs an "activity-flow" model where edges represent causal relationships (e.g., "protein A up-regulates protein B") [12]. A recent curation effort embedded over 300 additional ASD-associated genes from the SFARI database into this causal network, enabling systematic analysis of their connectivity [12].

Key Findings:

- 778 of 1003 SFARI genes are now annotated in SIGNOR, with the vast majority (770) forming a single connected network [12]

- SFARI proteins form a highly interconnected cluster with 411 directed causal edges extracted from 285 publications [12]

- Random walk community detection identified four major functional communities related to neuronal development, synaptic processes, and neurotransmitter metabolism [12]

Polygenic Architecture and Developmental Trajectories

Recent evidence suggests that ASD's genetic architecture can be decomposed into distinct polygenic factors associated with different developmental trajectories and clinical presentations.

Protocol: Polygenic Factor Analysis in Developmental Cohorts

Application: Identification of genetically distinct ASD subtypes with different developmental trajectories.

Materials:

- Longitudinal birth cohort data (e.g., Millennium Cohort Study, Longitudinal Study of Australian Children)

- Genetic data (SNP arrays or whole-genome sequencing)

- Behavioral assessment tools (e.g., Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire - SDQ)

- Clinical diagnostic information on age at ASD diagnosis

Procedure:

- Developmental Trajectory Modeling:

- Collect longitudinal SDQ data across multiple timepoints from childhood to adolescence.

- Use growth mixture modeling to identify latent trajectory classes without a priori hypotheses.

- Validate optimal number of classes using statistical fit indices (BIC, aBIC, BLRT).

Genetic Data Processing:

- Perform quality control on genetic data: sample call rate >98%, SNP call rate >95%, HWE p>1×10⁻⁶.

- Calculate ASD polygenic scores using latest GWAS summary statistics.

- Conduct genetic correlation analysis between identified trajectory classes.

Association Analysis:

- Test associations between trajectory classes and age at ASD diagnosis using chi-square tests.

- Evaluate contribution of polygenic scores to trajectory class membership using multinomial regression.

- Assess genetic correlations with related neurodevelopmental conditions (ADHD, mental health conditions).

Key Findings from Recent Research:

- Two distinct developmental trajectories emerge: "early childhood emergent" (difficulties stable or modestly attenuating) and "late childhood emergent" (difficulties increasing in adolescence) [10]

- These trajectories are associated with age at diagnosis (p=1.42×10⁻⁴) and have different genetic profiles [10]

- ASD polygenic architecture decomposes into two genetically correlated factors (rg=0.38):

Figure 2: Two-factor model of ASD polygenic architecture showing distinct developmental trajectories and comorbidity patterns. The two factors show moderate genetic correlation (rg=0.38) but different clinical presentations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ASD Network Analysis Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Models | NGN2-induced excitatory neurons (iNs) [11] | Critical for neuron-specific protein interaction studies; reveals interactions missed in non-neural cells |

| Genomic Databases | SFARI Gene database (https://gene.sfari.org/) [12] | Expert-curated ASD risk genes with evidence scores; essential for candidate gene prioritization |

| Interaction Databases | SIGNOR database [12] | Causal signaling relationships in machine-readable format; enables network-based analysis |

| Proteomic Tools | Co-immunoprecipitation with LC-MS/MS [11] | Identifies protein complexes in neuronal contexts; requires validation with orthogonal methods |

| Single-Cell Transcriptomics | Seurat v.3 pipeline [13] | Enables identification of cell-type-specific expression patterns for ASD risk genes |

| Gene Prioritization Metrics | pLI scores [13], brain critical exons [13] | Identifies genes intolerant to loss-of-function mutations; helps prioritize functional variants |

The understanding of ASD genetic architecture has evolved substantially from a focus on individual high-penetrance variants to a complex network model involving hundreds of genes interacting through defined biological pathways. The integration of protein interaction data, causal network analysis, and developmental genetic trajectories provides a more comprehensive framework for understanding ASD pathophysiology. The experimental protocols outlined here—from neuronal proteomics to polygenic trajectory analysis—provide researchers with practical methodologies to advance this systems-level understanding. Future research should focus on integrating these diverse data types to identify convergent, actionable pathways for therapeutic development, while considering the developmental context in which these genetic risk factors operate.

Key Biological Networks Implicated in ASD Pathogenesis

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction, as well as restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities [14]. The disorder's pathogenesis involves a highly heterogeneous genetic architecture and disruptions in multiple, converging biological networks. Large-scale genomic studies and advanced proteomic approaches have begun to map the intricate protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks and signaling pathways that underlie ASD pathophysiology [15] [16]. This application note synthesizes current findings on key biological networks in ASD and provides detailed methodological protocols for investigating these networks, enabling researchers to advance both mechanistic understanding and therapeutic development.

Key Biological Networks in ASD Pathogenesis

Research has identified several core biological networks consistently implicated in ASD pathogenesis. These networks represent convergent molecular mechanisms through which diverse genetic risk factors manifest in ASD-related neurodevelopmental alterations.

Table 1: Key Biological Networks in ASD Pathogenesis

| Biological Network | Key Components | ASD Association | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synaptic Development & Function | SHANK, SYNGAP, NLGN, NRXN | Altered synaptic transmission, excitation/inhibition balance [17] | Neuron-specific PPI mapping shows disrupted synaptic protein networks [16] |

| Chromatin Remodeling & Transcriptional Regulation | CHD8, MECP2, ADNP | Impaired neuronal differentiation, gene expression dysregulation [18] [19] | Enrichment in social/behavioral ASD subclass; Wnt, Notch signaling pathways [20] |

| Mitochondrial & Metabolic Processes | Mitochondrial proteins, metabolic enzymes | Oxidative phosphorylation deficits, energy metabolism impairment [16] [17] | CRISPR knockout shows association between mitochondrial activity and ASD risk genes [16] |

| Neuronal Signaling Pathways | MAPK, Wnt, mTOR signaling | Disrupted neurodevelopment, neuronal connectivity [16] | Multi-omics integration reveals pathway-specific enrichment in ASD subtypes [20] [16] |

| Immunoinflammatory Response | Cytokines, microglial genes | Neuroinflammation, altered synaptic pruning [14] [17] | Transcriptomic studies show innate immune response dysregulation [17] |

Protein-Protein Interaction Networks

A comprehensive neuron-specific proximity-labeling proteomics study mapping 41 ASD risk genes revealed extensive PPI networks with significant convergence [16]. This research identified that:

- ASD risk genes share common protein partners and biological pathways despite genetic heterogeneity

- De novo missense variants significantly disrupt normal PPI networks

- PPI network clustering corresponds to clinical behavior score severity, linking molecular mechanisms to phenotypic expression

- Key convergent pathways include mitochondrial/metabolic processes, Wnt signaling, and MAPK signaling

Diagram 1: ASD risk genes converge on key biological networks

Quantitative Genetics of ASD Subdomains

Genome-wide association studies of ASD phenotypic subdomains have revealed distinct genetic architectures across different symptom manifestations. Analysis of six ADI-R-derived subdomains shows varying heritability estimates and polygenic risk score associations.

Table 2: Genetic Architecture of ASD Phenotypic Subdomains

| ASD Subdomain | h²SNP | PRS for ASD Diagnosis (Variance Explained) | Genetic Correlation with Social Domains | Key Identified Genes/Loci |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Interaction (SI) | 0.2-0.4 | 2.3-3.3% | High | 11q23 [21] |

| Peer Interaction (PI) | 0.2-0.4 | 2.3-3.3% | High | - |

| Joint Attention (JA) | 0.2-0.4 | 2.3-3.3% | High | - |

| Nonverbal Communication (NVC) | 0.2-0.4 | 0.7% | Moderate | - |

| Restricted Interests (RI) | 0.2-0.4 | 4.5% | Low | - |

| Repetitive Sensory-Motor Behavior (RB) | 0.2-0.4 | 1.2% | Low | 19q13.3 [21] |

Key findings from quantitative genetic studies include:

- Social communication subdomains (SI, PI, JA) share genetic risk factors [21]

- Restricted/repetitive behavior subdomains (RI, RB) are genetically independent of each other and from social domains [21]

- The polygenic risk score for categorical ASD diagnosis explains varying variance across subdomains (0.7-4.5%) [21]

- Eight genome-wide significant hits have been identified for specific subdomains [21]

ASD Subclasses from Integrated Phenotypic-Genomic Analysis

Recent research leveraging the SPARK cohort has identified four distinct ASD subclasses through integrated analysis of phenotypic and genotypic data [20]. This person-centered approach classified individuals based on comprehensive trait profiles and revealed distinct biological signatures for each subclass.

Table 3: ASD Subclasses with Distinct Phenotypic and Biological Profiles

| ASD Subclass | Prevalence | Core Phenotypic Features | Developmental Trajectory | Key Biological Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social & Behavioral Challenges | 37% | ADHD, anxiety, depression, mood dysregulation, repetitive behaviors | Typical developmental milestones, later diagnosis | Postnatal gene activity, neuronal action potentials [20] |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | 19% | Developmental delays, fewer behavioral comorbidities | Early developmental delays | Prenatal gene activity [20] |

| Moderate Challenges | 34% | Milder symptoms across domains, no developmental delays | Typical developmental milestones | - |

| Broadly Affected | 10% | Widespread challenges across all domains | Significant developmental delays | Multiple convergent pathways |

Notably, each subclass demonstrated minimal overlap in impacted biological pathways, with distinct functional enrichment:

- Social/Behavioral Challenges class: Genes predominantly active postnatally [20]

- ASD with Developmental Delay class: Genes predominantly active prenatally [20]

- Each class associated with previously implicated but largely non-overlapping ASD pathways [20]

Experimental Protocols for ASD Network Analysis

Protocol: Neuron-Specific Proximity-Labeling Proteomics (BioID2)

Purpose: To identify protein-protein interaction networks for ASD risk genes in neuronal contexts [16].

Materials:

- Primary neuronal cultures (E18 rat cortical neurons recommended)

- BioID2 vectors with ASD risk gene coding sequences

- BirA*-tagging constructs

- Biotin supplementation

- Streptavidin-coated magnetic beads

- Mass spectrometry equipment and reagents

Methodology:

- Construct Preparation: Clone 41 ASD risk genes into BioID2 vectors with neuronal promoters

- Neuronal Transfection: Transfect primary neurons at DIV 7-10 using appropriate methods

- Biotin Labeling: Supplement with 50μM biotin for 24 hours to enable proximity-dependent biotinylation

- Cell Lysis: Harvest and lyse neurons in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors

- Affinity Purification: Incubate with streptavidin-coated magnetic beads for 2 hours at 4°C

- Stringent Washing: Perform serial washes with RIPA, 1M KCl, 0.1M Na2CO3, and 2M urea in Tris buffer

- On-Bead Digestion: Digest proteins with trypsin overnight at 37°C

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze peptides using LC-MS/MS with appropriate controls

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Identify high-confidence interactions using SAINT algorithm, perform pathway enrichment

Validation: Include controls for non-specific biotinylation, validate key interactions by co-immunoprecipitation, assess functional impact of de novo missense variants on PPI networks

Protocol: Transcriptomic Analysis of ASD and Comorbid Conditions

Purpose: To identify key genes and regulatory networks underlying ASD and comorbid conditions such as sleep disturbances [22].

Materials:

- GEO datasets (GSE18123 for ASD, GSE48113 for sleep disturbances)

- R packages: limma, WGCNA, clusterProfiler

- miRcode database access

- CMap database for drug repositioning

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Download and preprocess gene expression data from GEO database

- Quality Control: Apply quantile normalization, remove batch effects, filter low-expression genes

- Differential Expression: Identify DEGs using limma with thresholds (adj. p < 0.05, |log2FC| > 0.585)

- Co-expression Analysis: Perform WGCNA to identify gene modules associated with clinical features

- Functional Enrichment: Conduct HALLMARK GSEA and KEGG pathway analysis

- Regulatory Network Mapping: Predict miRNA-gene interactions using miRcode database

- Drug Repositioning: Query CMap database to identify potential therapeutic compounds

- Immune Infiltration Analysis: Estimate immune cell proportions and correlate with key genes

Key Applications: Identification of shared genes (e.g., LAMC3 in ASD and sleep disturbances), construction of regulatory networks, discovery of potential therapeutic targets [22]

Protocol: Network Structure Analysis of Gene Correlation

Purpose: To identify autism-related genes through structural analysis of gene correlation networks [23].

Materials:

- Gene expression datasets (e.g., GSE25507 from NCBI)

- Statistical analysis tools (R recommended)

- Network analysis packages

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Process gene expression data from peripheral blood lymphocytes (82 ASD, 64 controls)

- Statistical Screening: Apply sequential hypothesis testing:

- Two-sample KS test for distribution consistency

- Single-sample KS test for normality

- F-test for variance homogeneity

- Appropriate t-test (standard or Welch's) or Mann-Whitney test

- Network Construction: Build Spearman correlation networks for control and ASD groups

- Structural Analysis: Calculate average degree and other network parameters across different thresholds

- Gene Identification: Identify genes with maximal structural differences (MD-Gs) between networks

- Functional Annotation: Perform enrichment analysis of identified genes

Analysis Parameters: FDR thresholds: KS two-sample (0.0005), KS single-sample (0.001), F-test (0.001), t-test/Mann-Whitney (0.001) [23]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for ASD Network Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteomic Tools | BioID2 vectors, Streptavidin beads, Mass spectrometry reagents | PPI network mapping [16] | Proximity-dependent labeling, protein complex isolation, interaction identification |

| Genomic Analysis Tools | WGCNA R package, limma package, GEO datasets | Transcriptomic network analysis [22] [21] | Co-expression analysis, differential expression, module identification |

| Cell Models | Primary neuronal cultures, iPSC-derived neurons | Functional validation of ASD risk genes [16] | Neuron-specific network analysis, developmental pathway studies |

| Bioinformatic Databases | miRcode, CMap, KEGG, HALLMARK gene sets | Pathway enrichment and drug repositioning [22] | Regulatory network prediction, therapeutic compound identification |

| Genetic Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 systems, SNP arrays, Sequencing platforms | Functional validation and genetic association [16] | Gene editing, variant functional assessment, association studies |

Visualization of Key Signaling Pathways in ASD

Diagram 2: Signaling pathways from genetics to behavior in ASD

The integration of large-scale genomic data with detailed phenotypic information has revealed distinct biological networks underlying ASD pathogenesis. These networks - encompassing synaptic function, chromatin remodeling, mitochondrial processes, and specific signaling pathways - provide a framework for understanding how diverse genetic risk factors converge on common neurodevelopmental mechanisms. The experimental protocols outlined herein enable researchers to systematically investigate these networks, from neuron-specific protein interactions to transcriptomic regulation across ASD subdomains. As these approaches continue to evolve, they promise to advance both biological understanding and precision medicine approaches for ASD.

Application Notes

This document outlines a structured methodology for investigating the shared molecular architecture between Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), sleep disturbances (SD), and immune dysfunction. This comorbidity is highly prevalent, with approximately 40-80% of individuals with ASD experiencing significant sleep problems [22] [24], and a substantial body of evidence pointing to concurrent immune dysregulation [25] [26]. The following integrated protocol leverages multi-omics data and network analysis to identify central players and pathways in this complex relationship, providing a framework for identifying novel diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets.

Table 1: Key Genes Implicated in ASD with Sleep and Immune Comorbidity

| Gene Symbol | Primary Function | Association with ASD | Association with Sleep | Association with Immune Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAMC3 | Neural development, cortical layering | Key shared gene identified via WGCNA & DEG analysis [22] [27] | Key shared gene identified via WGCNA & DEG analysis [22] [27] | Expression positively correlated with specific immune cell proportions [22] [27] |

| SHANK3 | Synaptic scaffolding protein | Strongly associated; high importance in random forest model [28] [4] | Mouse models show altered sleep architecture (increased REM) [24] | - |

| CHD8 | Chromatin remodeling, transcription regulation | High-penetrance risk gene [24] | Mouse models show reduced wakefulness, disrupted REM sleep [24] | - |

| MGAT4C | Glycosylation enzyme | Potential robust biomarker (AUC = 0.730) [28] [4] | - | Shows significant correlation with multiple immune cell types [28] [4] |

| NLRP3 | Innate immunity, inflammasome | Key feature gene from random forest analysis [28] [4] | - | Central to inflammatory response; part of immune dysregulation in ASD [28] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Identification of Comorbidity-Associated Genes

Objective: To identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and co-expression modules associated with ASD and comorbid sleep disturbances.

Workflow Overview: The following diagram illustrates the multi-dataset integration and analysis workflow for identifying key genes and pathways.

Materials & Reagents:

- Data Source: Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) accession numbers GSE18123 (ASD) and GSE48113 (sleep disturbance) [22].

- Software: R statistical environment (version 4.2.2 or higher).

- R Packages:

limma(v3.58.1) for differential expression,WGCNA(v1.72) for co-expression network analysis.

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Download raw gene expression data (e.g., CEL files) from the specified GEO datasets.

- Perform background correction, log2 transformation, and quantile normalization using the

limmaandaffypackages. - Remove batch effects using the

removeBatchEffectfunction inlimmaif necessary. - Filter out low-expression genes (e.g., genes below the 20th percentile in >80% of samples).

Differential Expression Analysis:

- Using the

limmapackage, fit a linear model to compare ASD and SD samples against their respective controls. - Define DEGs using an adjusted p-value < 0.05 and an absolute log2 fold change (

|log2FC|) > 0.585 [22].

- Using the

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA):

- Use the

WGCNAR package to construct co-expression networks for the ASD and SD datasets separately. - Choose an appropriate soft-thresholding power (β) to achieve a scale-free topology.

- Construct a topological overlap matrix (TOM) and identify gene modules using dynamic tree cutting.

- Correlate module eigengenes with the ASD and SD traits. Select modules with the highest significance for downstream analysis.

- Identify hub genes within significant modules based on module membership (MM) and gene significance (GS) scores.

- Use the

Integration of Gene Sets:

Protocol 2: Functional Enrichment and Pathway Analysis

Objective: To determine the biological processes, molecular functions, and signaling pathways enriched in the identified gene sets.

Procedure:

- Gene Set Enrichment Analysis:

- Perform HALLMARK gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using the

clusterProfilerR package (v4.10.1) on the ranked list of DEGs or the gene set of interest. - This helps identify broad, well-defined biological themes.

- Perform HALLMARK gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using the

- Pathway Enrichment Analysis:

- Conduct Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis on the list of key genes or DEGs using

clusterProfiler. - Use a hypergeometric test with a significance threshold of adjusted p-value < 0.05. Pathways frequently implicated include those involved in immune function and TNF-related signaling [25], neurodevelopment, and oxidative stress [22].

- Conduct Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis on the list of key genes or DEGs using

Protocol 3: Analysis of Immune Cell Infiltration

Objective: To quantify differences in immune cell populations between ASD and control samples and correlate these with key gene expression.

Materials & Reagents:

- Input Data: Normalized gene expression matrix from blood or peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) samples (e.g., from GSE18123).

- Software: R package

GSVA(v1.46.x).

Procedure:

- Immune Deconvolution:

- Use the

GSVApackage to perform immune deconvolution on the transcriptomic expression matrix. - Employ a validated reference signature matrix (e.g., from the literature) to resolve the relative proportions of diverse immune cell subtypes (e.g., T cells, B cells, NK cells, monocytes).

- Use the

- Statistical Correlation:

- Compare the estimated proportions of immune cells between ASD and control groups using a Wilcoxon test.

- Perform correlation analysis (Spearman or Pearson) between the expression levels of key genes (e.g., LAMC3, MGAT4C, SHANK3) and the proportions of immune cell subpopulations.

- Visualize significant correlations using a heatmap generated with the

corrplotR package (v0.95) [28] [4].

Protocol 4: In-depth Immune Profiling via Multi-omics

Objective: To deeply characterize immune dysregulation in ASD using transcriptomic, proteomic, and single-cell RNA sequencing.

Workflow Overview: This diagram outlines the multi-omics approach for dissecting immune dysregulation in ASD.

Materials & Reagents:

- Biological Samples: PBMCs and plasma from well-characterized ASD and matched control subjects [25].

- Transcriptomics: NanoString nCounter Human Immune Exhaustion Panel (785 genes) and associated master kit.

- Proteomics: Multiplex immunoassay platforms (e.g., Luminex) for cytokine/protein quantification.

- Single-cell RNA-seq: Platform for single-cell library preparation and sequencing (e.g., 10x Genomics).

Procedure:

- Targeted Transcriptomics:

- Extract high-quality RNA from PBMCs.

- Hybridize 100 ng of RNA per sample using the NanoString nCounter panel and run on the nCounter Digital Analyzer.

- Perform data normalization and differential expression analysis on the Rosalind platform or using

limmain R. Validate signatures in independent blood and brain tissue datasets [25].

Proteomic Profiling:

- Analyze plasma samples using a high-throughput multiplex proteomic assay.

- Identify differentially expressed proteins (e.g., TNFSF10/TRAIL, TNFSF11/RANKL, TNFSF12/TWEAK) focusing on pathways highlighted by transcriptomic data, such as TNF signaling [25].

Single-cell RNA Sequencing:

- Prepare single-cell suspensions from PBMCs.

- Construct scRNA-seq libraries and sequence on an appropriate platform.

- Perform standard bioinformatic analysis (cell clustering, marker gene identification) to assign cell types.

- Analyze expression of dysregulated genes and pathways (from steps 1 and 2) within specific immune cell subsets (e.g., CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, NK cells) to pinpoint cellular contributors to ASD immune pathology [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Item | Function/Application in Protocol | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| nCounter Human Immune Panel | Targeted transcriptomic profiling of 785 immune-related genes from PBMC RNA [25]. | NanoString panel #XT-H-EXHAUST-12 |

| limma R Package | Statistical analysis for identifying differentially expressed genes from microarray or RNA-seq data [22] [28]. | R package, version 3.58.1 |

| WGCNA R Package | Construction of weighted gene co-expression networks to identify modules of highly correlated genes [22]. | R package, version 1.72 |

| GSVA R Package | Deconvolution of bulk transcriptomic data to estimate abundances of immune cell populations [28]. | R package, version 1.46.x |

| clusterProfiler R Package | Functional enrichment analysis (GO, KEGG) of gene lists to identify overrepresented biological pathways [28]. | R package, version 4.10.1 |

| Cytoscape Software | Visualization and further analysis of protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks and other biological networks [28]. | Version 3.10.3 or higher |

| Chd8 Mutant Mice | Established model for studying ASD with sleep comorbidities; used for EEG/EMG sleep architecture analysis [24]. | Available from JAX (Stock #030583) |

Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Gene Networks Across Neurodevelopment

The developing mammalian brain is characterized by precisely orchestrated spatiotemporal gene expression patterns that guide cellular differentiation, regional identity, and circuit formation. Disruptions to these molecular programs represent a core pathological mechanism in complex neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [29] [30]. The intricate choreography of brain development extends well into the postnatal period, with both the brain and epigenome undergoing continuous maturation through adolescence [30]. Traditional bulk omics approaches have historically obscured critical cell-type-specific dynamics, but emerging single-cell and spatial technologies now enable unprecedented resolution of these processes [31]. This Application Note synthesizes recent methodological advances for mapping spatiotemporal gene networks, with particular emphasis on applications within ASD research. We provide detailed experimental protocols for spatial multi-omic profiling and computational workflows for identifying disease-relevant network perturbations, offering researchers a comprehensive toolkit for investigating neurodevelopmental pathogenesis.

Technical Foundations of Spatiotemporal Analysis

Spatial Multi-Omic Profiling Technologies

Spatially resolved transcriptomics (SRT) technologies have evolved into two principal categories: imaging-based and sequencing-based methods, each with complementary advantages and limitations [32]. Imaging-based SRT technologies (e.g., MERFISH, seqFISH, Xenium) use fluorescence in situ hybridization to measure hundreds of target genes at single-cell or subcellular resolution, but are limited to predefined gene panels [32] [31]. In contrast, sequencing-based SRT technologies (e.g., 10x Visium, Slide-seq, DBiT-seq) capture transcriptome-wide expression profiles, though historically at lower spatial resolution (spots containing multiple cells) [32]. Recent advancements in sequencing-based technologies like Stereo-seq and Ex-ST have achieved subcellular resolution, albeit at increased cost [31].

The integration of epigenomic and proteomic measurements with transcriptomic profiling represents a frontier in spatial biology. The deterministic barcoding in tissue (DBiT) platform enables simultaneous genome-wide profiling of chromatin accessibility (spatial ATAC-RNA-protein sequencing; spatial ARP-seq) or histone modifications (spatial CUT&Tag-RNA-protein sequencing; spatial CTRP-seq) alongside the whole transcriptome and approximately 150 proteins within the same tissue section [29]. This spatial tri-omic approach provides unprecedented insight into the molecular mechanisms operating across all layers of the central dogma during brain development and disease states [29].

Table 1: Comparison of Selected Spatial Transcriptomics Technologies

| Technology | Type | Spatial Resolution | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Visium | Sequencing-based | Multicellular (55 μm) | Whole transcriptome, standardized workflow | Multiple cells per spot |

| MERFISH | Imaging-based | Subcellular | High resolution, single-cell analysis | Targeted panel only |

| DBiT-seq | Sequencing-based | Cellular (15-20 μm) | Multi-omics integration (ATAC/RNA/protein) | Does not always resolve single cell |

| Stereo-seq | Sequencing-based | Subcellular | High resolution & capture efficiency | High cost |

| Slide-seq | Sequencing-based | Cellular (10 μm) | High spatial resolution | Lower detection efficiency |

Computational Methods for Spatial Pattern Analysis

A crucial early step in SRT data analysis is the detection of spatially variable genes (SVGs) - genes whose expression exhibits non-random, informative spatial patterns [32]. Computational methods for SVG detection can be categorized by their underlying definitions and biological interpretations:

- Overall SVGs: Screen informative genes for downstream analyses including spatial domain identification and functional gene modules. Methods include SpatialDE, SPARK, and nnSVG [32].

- Cell-type-specific SVGs: Reveal spatial variation within a cell type, helping identify distinct subpopulations or states [32].

- Spatial-domain-marker SVGs: Serve as marker genes to annotate and interpret previously detected spatial domains [32].

For large-scale datasets, computational efficiency becomes paramount. PreTSA offers a computationally efficient method for modeling temporal and spatial gene expression patterns in datasets comprising millions of cells, significantly outperforming traditional generalized additive models (GAM) in processing speed while maintaining analytical accuracy [33]. This method employs B-splines and efficient matrix operations to characterize expression patterns, enabling application to extremely large datasets that have become increasingly common with advancing technologies [33].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Spatial Tri-Omics Profiling of Developing Brain Tissue

This protocol describes the procedure for simultaneous profiling of the epigenome, transcriptome, and proteome from the same tissue section using DBiT-based spatial ARP-seq [29].

Materials and Reagents

- Tissue Preparation:

- Fresh-frozen brain tissue sections (10-20 μm thickness)

- Formaldehyde (1-3% for fixation)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Ethanol gradients (50%, 70%, 100%)

- Spatial Barcoding:

- DBiT microfluidic channel array chips (100 or 220 channels)

- Barcoded oligos (A1-A100/220, B1-B100/220)

- Tn5 transposase loaded with universal ligation linker

- Biotinylated poly(T) adapter

- Antibody Staining:

- Cocktail of antibody-derived DNA tags (ADTs) for target proteins (~150 antibodies)

- Primary antibodies validated for DBiT-seq

- Secondary antibodies if required

- Library Preparation:

- Reverse transcription reagents

- PCR amplification reagents

- Solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads

- Library quantification reagents (Qubit, Bioanalyzer)

- Equipment:

- Cryostat

- Microfluidic chip alignment system

- Thermocycler

- Next-generation sequencer (Illumina recommended)

Procedure

Tissue Preparation and Fixation

- Section fresh-frozen brain tissue at 10-20 μm thickness using a cryostat and transfer to glass slides.

- Fix tissue with formaldehyde (1-3%) for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Wash with PBS and dehydrate through ethanol gradients (50%, 70%, 100%).

Antibody Incubation

- Incubate tissue section with a cocktail of ADTs for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Wash with PBS to remove unbound antibodies.

Spatial Barcoding with Microfluidics

- Assemble first microfluidic chip with parallel channels (A1-A100/220) on tissue section.

- Introduce first set of spatial barcodes (Ai) through channels and incubate for 5 minutes.

- Remove first chip and assemble second chip with perpendicular channels (B1-B100/220).

- Introduce second set of spatial barcodes (Bj) and incubate for 5 minutes.

- This creates a 2D grid of spatially barcoded tissue pixels (20 μm for 100 barcodes, 15 μm for 220 barcodes).

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Perform in-tissue reverse transcription with biotinylated poly(T) adapter.

- Release barcoded cDNAs (from mRNAs and ADTs) and genomic DNA fragments.

- Construct separate libraries for gDNA (chromatin accessibility) and cDNA (transcriptome/proteome).

- Quantify libraries and sequence on Illumina platform (recommended depth: >50,000 reads per spot).

Data Processing

- Demultiplex reads using spatial barcodes (Ai and Bj) to assign to tissue pixels.

- Align cDNA reads to reference transcriptome and ADT reads to antibody barcode database.

- Align gDNA reads to reference genome for chromatin accessibility profiling.

- Generate integrated matrices of gene expression, protein abundance, and chromatin accessibility across spatial coordinates.

*Figure 1: Spatial Tri-Omics Experimental Workflow. The integrated protocol enables simultaneous profiling of transcriptome, epigenome, and proteome from a single tissue section.*

Protocol: Network-Based Identification of ASD-Associated Genes

This protocol describes a computational approach for identifying autism-associated genes through network propagation and machine learning, integrating multiple omic data sources [34].Materials and Software

- Data Resources:

- ASD-associated gene lists from genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic studies (e.g., SFARI Gene database)

- Protein-protein interaction network (e.g., STRING, Signorini et al. network with 20,933 proteins)

- Gene expression data from brain tissues (e.g., BrainSpan Atlas)

- Software:

- Python 3.7+ with scikit-learn, pandas, numpy

- R 4.0+ with WGCNA, Seurat for co-expression analysis

- Network analysis tools (Cytoscape with MCODE plugin)

Procedure

Feature Generation through Network Propagation

- Compile multiple ASD-associated gene lists from different data sources (e.g., GWAS, differential expression, copy number variation).

- For each gene list, perform network propagation on PPI network:

- Set initial value of each seed protein to 1/s (where s is seed set size)

- Run propagation with damping parameter α = 0.8

- Normalize results using eigenvector centrality to correct for node degree bias

- Generate feature set comprising propagation scores from all input gene lists.

Machine Learning Classification

- Prepare training set with positive examples (SFARI Category 1 genes) and negative examples (random genes not in SFARI).

- Train random forest classifier using propagation scores as features.

- Optimize hyperparameters through cross-validation.

- Evaluate classifier performance using 5-fold cross-validation (target AUROC > 0.85).

Functional Validation

- Perform functional enrichment analysis on top predicted genes (GO, KEGG, Human Phenotype Ontology).

- Validate predictions against independent gene sets (SFARI scores 2 and 3).

- Compare performance against existing predictors (e.g., forecASD).

Applications in Autism Spectrum Disorder Research

Network Dysregulation in ASD Pathogenesis

Gene co-expression network analysis has revealed functionally coherent modules disrupted in ASD across multiple brain regions. Studies integrating transcriptome data from 178 brain tissues identified 365 network-specific core genes (NCGs) across 18 co-expression modules significantly correlated with ASD [35]. These modules were enriched for biological processes including synaptic transmission, chromatin organization, and immune response, highlighting the diverse pathological mechanisms involved in ASD [35] [36]. In Pitt-Hopkins syndrome (PTHS), a monogenic form of ASD caused by TCF4 mutations, network analysis of patient-derived neural cells revealed distinct interactomes for neural progenitor cells (325 nodes, 504 edges) and neurons (673 nodes, 1897 edges) [36]. The NPC interactome showed significant enrichment for upregulated genes in PTHS patients, while the neuronal interactome displayed more downregulated genes, suggesting developmental stage-specific impacts of TCF4 mutation [36]. Hub gene analysis identified central nodes involved in histone modification, synaptic vesicle trafficking, and cell signaling, suggesting potential therapeutic targets [36]. *Table 2: Key Network Analysis Findings in ASD Research*| Study Type | Key Findings | Biological Processes Implicated | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-region Brain Transcriptomics | 365 NCGs in 18 co-expression modules | Synaptic transmission, chromatin organization, immune response | [35] |

| Monogenic ASD (PTHS) Model | Distinct NPC vs. neuronal interactomes | Histone modification, synaptic function, cell signaling | [36] |

| Blood-based Transcriptomics | 244 differentially expressed genes | Gland development, cardiovascular development, nervous system embryogenesis | [23] |

| Network Propagation Predictor | 84 high-confidence ASD genes | Chromatin organization, histone modification, neuron cell-cell adhesion | [34] |

Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Brain Development

Recent spatial multi-omic studies have mapped the progressive molecular patterning of the developing mouse brain from postnatal day 0 (P0) to P21, revealing intricate temporal persistence and spatial spreading of chromatin accessibility for layer-defining transcription factors [29]. In the cortex, transcription factors such as CUX1/2 (upper layers II/III/IV), TBR1 (layers IV/V/VI), and CTIP2 (deeper layers V/VI) exhibited distinct spatial expression gradients that evolved across developmental timepoints [29]. These layer-defining transcription factors showed reduced protein expression and cellular density by P21 compared to early postnatal stages, consistent with the progression of cortical maturation [29]. In the corpus callosum, spatial profiling revealed dynamic chromatin priming of myelin genes across subregions, with a lateral-to-medial progression of myelination marked by the sequential appearance of MBP (starting at P7) and MOG (starting at P10) proteins [29]. This spatial progression was only completed by P21, when myelination extended throughout the entire corpus callosum and into cortical regions [29]. These findings demonstrate the precise spatiotemporal coordination of transcriptional and epigenetic programs underlying white matter development.*Figure 2: Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Key Molecular Markers During Postnatal Brain Development. Cortical layer-defining transcription factors show decreased expression over time while myelination markers progressively increase and spread.*

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

*Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Spatiotemporal Network Analysis*| Reagent/Resource | Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| DBiT Microfluidic Chips | Spatial Omics | Enables spatial barcoding for multi-omic profiling | Spatial ARP-seq, spatial CTRP-seq [29] |

| Antibody-Derived DNA Tags (ADTs) | Proteomics | Converts antibody binding to sequenceable barcodes | Spatial co-profiling of ~150 proteins [29] |

| 10x Visium/Visium HD | Spatial Transcriptomics | Whole transcriptome mapping with spatial context | Spatial domain identification, SVG detection [32] [31] |

| MERFISH Panel | Spatial Transcriptomics | Targeted high-resolution spatial gene expression | Cell-type mapping in subcortical regions [32] |

| STRING Database | Network Analysis | Protein-protein interaction network resource | Network propagation, interactome construction [36] [34] |

| SFARI Gene Database | ASD Resources | Curated ASD-associated gene annotations | Training classifiers, validating predictions [35] [34] |

| WGCNA R Package | Network Analysis | Weighted gene co-expression network analysis | Module identification, hub gene detection [35] [36] |

| PreTSA Algorithm | Computational Tool | Efficient spatial/temporal pattern modeling | Large-scale SVG/TVG detection [33] |

The integration of spatial multi-omic technologies with network-based computational approaches provides unprecedented insight into the spatiotemporal dynamics of gene networks across neurodevelopment. The experimental and analytical protocols detailed in this Application Note offer researchers comprehensive methodologies for investigating these complex processes, with particular relevance to ASD pathogenesis. As these technologies continue to evolve, future advances in resolution, multi-omic integration, and computational scalability will further enhance our ability to decipher the intricate molecular programs governing brain development and their disruption in neurodevelopmental disorders. These approaches hold significant promise for identifying novel therapeutic targets and biomarkers for complex conditions like autism spectrum disorder.

Computational Approaches for ASD Network Analysis: From WGCNA to AI

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) in ASD Transcriptomics

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by impairments in social interaction, communication, and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, with a rapidly increasing prevalence of at least 1.5% in developed countries [22]. The etiological complexity of ASD stems from highly heterogeneous genetic and environmental factors that converge on common biological pathways, making systems biology approaches particularly valuable for elucidating its underlying mechanisms. Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) has emerged as a powerful computational framework that addresses this complexity by moving beyond single-gene analyses to identify networks of highly correlated genes (modules) that represent functional biological units [37] [38].

In the context of ASD research, WGCNA provides a robust methodology for detecting coordinated gene expression patterns across different brain regions, developmental stages, or experimental conditions, enabling researchers to identify disease-relevant modules and their key regulatory elements (hub genes) [22] [39]. This approach has proven particularly valuable for integrating multi-omics data, identifying biomarker signatures, and uncovering the molecular architecture of ASD and its frequently co-occurring conditions, such as sleep disturbances, which affect approximately 50-80% of children with ASD compared to 25-40% in typically developing children [22]. By treating gene modules as functional units, WGCNA effectively reduces the dimensionality of high-throughput transcriptomic data while enhancing the biological interpretability of results and providing a network-based foundation for understanding the systems-level properties of ASD pathophysiology.

Theoretical Foundations of WGCNA

Key Concepts and Network Topology

WGCNA constructs a weighted network based on pairwise correlations between gene expression profiles across multiple samples, preserving the continuous nature of co-expression information rather than applying arbitrary hard thresholds to define connections [37]. The fundamental mathematical representation of a WGCNA network is the adjacency matrix, a symmetric n × n matrix where each element a_ij quantifies the connection strength between genes i and j, with values ranging from 0 to 1 [37]. This adjacency matrix is derived through a soft thresholding approach that emphasizes strong correlations while penalizing weak ones, with the optimal threshold parameter (β) selected to approximate a scale-free topology network, a property commonly observed in biological systems where few genes (hubs) have many connections while most genes have few connections [37] [38].

The topological overlap measure (TOM) represents a crucial advancement over simple correlation, as it not only considers the direct connection between two genes but also their shared neighborhood connections, providing a more biologically meaningful measure of network interconnectedness [37] [38]. This transformation helps identify modules of highly interconnected genes with similar expression patterns that often correspond to functional units, with the module eigengene (ME) defined as the first principal component of a given module serving as the most representative expression profile for that entire group of genes [38]. The network analysis culminates in the identification of hub genes within modules, which are highly connected genes that often play crucial regulatory roles and may represent potential therapeutic targets for ASD intervention [22] [38].

Comparison with Alternative Analytical Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Transcriptomic Analysis Methods in ASD Research

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Suitable ASD Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Expression | Identifies individual genes with significant expression changes between conditions | Simple interpretation; well-established statistics | Multiple testing burden; ignores gene interactions; limited biological context | Initial screening; candidate gene identification; validation studies |

| WGCNA | Identifies modules of co-expressed genes; preserves continuous correlation information | Systems-level perspective; robust to outliers; enhanced biological interpretability | Requires larger sample sizes; computational complexity; parameter selection | Pathway discovery; network hub identification; multi-omics integration |

| PCA | Redimensionality through linear transformation to orthogonal components | Effective noise reduction; visualization of sample relationships | Linear assumptions; difficult biological interpretation of components | Data quality control; batch effect assessment; exploratory analysis |

| Machine Learning | Pattern recognition through supervised or unsupervised algorithms | Predictive modeling; handles complex interactions | Black box nature; risk of overfitting; requires large datasets | Classification models; biomarker panels; subtype identification |

WGCNA offers distinct advantages for ASD research compared to conventional differential expression analysis, as it specifically addresses the polygenic nature of ASD by focusing on groups of functionally related genes rather than individual genes with large effect sizes [37] [38]. This approach not only enhances statistical power by reducing multiple testing burden but also provides inherent biological context through the identified modules, allowing researchers to formulate testable hypotheses about ASD pathophysiology even when individual effect sizes are small [22]. Furthermore, WGCNA's focus on correlation patterns rather than mean expression differences makes it particularly robust to batch effects and normalization artifacts that frequently complicate ASD transcriptomic studies, especially when integrating data across different brain banks or sequencing platforms [38].

WGCNA Protocol for ASD Transcriptomics

Experimental Design and Data Preparation

Sample Size Considerations: For reliable WGCNA of ASD transcriptomic data, a minimum of 20-30 samples is generally recommended, though larger sample sizes (n > 100) substantially improve module detection and stability, particularly given the heterogeneous nature of ASD [37] [38]. When designing studies specifically for WGCNA, researchers should prioritize sample homogeneity in terms of brain region, developmental stage, and technical processing to maximize detection of biologically meaningful correlations, while still including sufficient phenotypic diversity to relate modules to clinical traits of interest [22].

Data Preprocessing Pipeline: Raw gene expression data from microarray or RNA-seq experiments must undergo rigorous quality control and normalization before WGCNA. For RNA-seq data, count normalization using variance-stabilizing transformations (e.g., DESeq2) or transcript-per-million (TPM) is essential, followed by filtering to remove lowly expressed genes (typically those below the 20th percentile in more than 80% of samples) [22]. Batch effects, particularly critical when combining datasets from different sources or processing dates, should be identified and corrected using established methods such as the removeBatchEffect function from the limma package or ComBat, with careful documentation of all preprocessing steps to ensure reproducibility [22] [40].

Trait Data Preparation: Clinical and phenotypic data relevant to ASD should be organized in a structured format compatible with WGCNA functions, including both continuous (e.g., severity scores, cognitive measures) and categorical variables (e.g., comorbid conditions, responder status). For studies investigating ASD comorbidities such as sleep disturbances, precisely defined trait measurements are essential for subsequent module-trait relationship analyses [22].

Step-by-Step Computational Protocol

Software Environment Setup: The following R packages are essential for implementing WGCNA in ASD research:

Network Construction and Module Detection:

Relating Modules to ASD Clinical Traits:

Identification and Validation of Hub Genes:

Downstream Bioinformatics Analyses

Functional Enrichment Analysis: Gene modules significantly associated with ASD traits require thorough functional annotation to interpret their biological relevance. The clusterProfiler package provides comprehensive tools for this purpose:

Cross-Study Validation and Meta-Analysis: To enhance the robustness of WGCNA findings in ASD research, validation in independent datasets is essential. Module preservation statistics between discovery and validation datasets provide quantitative measures of reproducibility:

Application of WGCNA in ASD Research

Case Study: Molecular Comorbidity of ASD and Sleep Disturbances

A recent study applied WGCNA to elucidate the shared molecular mechanisms between ASD and sleep disturbances (SD), integrating gene expression data from the GEO database (datasets GSE18123 for ASD and GSE48113 for SD) [22]. The analysis identified LAMC3 as a key shared gene between ASD and SD, encoding a protein crucial for neural development and associated with cortical malformations [22]. Functional enrichment analysis of comorbidity-related modules revealed significant associations with oxidative stress response, neurodevelopmental processes, and immune signaling pathways, providing mechanistic insights into this frequent clinical comorbidity [22].

The study further constructed a regulatory network around LAMC3, identifying several potential miRNA regulators, most notably hsa-miR-140-3p.1, which showed strong predicted regulatory effects on LAMC3 expression [22]. Immune infiltration analysis conducted in conjunction with WGCNA revealed significant differences in immune cell proportions between ASD and control groups, with LAMC3 expression positively correlated with specific immune cell populations, suggesting potential neuroimmune interactions at the interface of ASD and sleep pathophysiology [22].

Research Reagent Solutions for WGCNA in ASD

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for WGCNA in ASD Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Packages | Application in WGCNA Pipeline | Key Features for ASD Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| R Packages for Network Construction | WGCNA, igraph, dynamicTreeCut | Network construction, module detection, hub gene identification | Scale-free topology assessment; signed/unsigned networks; soft thresholding |

| Functional Annotation Tools | clusterProfiler, org.Hs.eg.db, GO.db, KEGG.db | Pathway enrichment; functional interpretation of modules | Brain-specific ontologies; neurodevelopmental pathways; drug-target databases |

| Data Visualization | ggplot2, gplots, Dendextend, Cytoscape | Network visualization; heatmaps; dendrograms | Integration with Cytoscape for publication-quality figures; modular heatmaps |

| Gene Expression Databases | GEO, ArrayExpress, BrainSpan, PsychENCODE | Data sourcing; validation studies | Brain region-specific expression; developmental trajectories; matched clinical data |

| Annotation Databases | miRBase, TFdb, DrugBank | Regulatory network analysis; drug repositioning | miRNA-target predictions; transcription factor networks; compound screening |

Integration with Multi-Omics Data in ASD