Network Biology and Machine Learning for Prioritizing Brain-Expressed ASD Risk Genes

This article synthesizes current computational strategies for identifying and prioritizing autism spectrum disorder (ASD) risk genes specifically expressed in the brain.

Network Biology and Machine Learning for Prioritizing Brain-Expressed ASD Risk Genes

Abstract

This article synthesizes current computational strategies for identifying and prioritizing autism spectrum disorder (ASD) risk genes specifically expressed in the brain. It explores the foundational genetic and transcriptomic landscape of ASD, details advanced methodologies combining network propagation, co-expression analysis, and machine learning, and addresses key challenges in model optimization and validation. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, the content highlights how integrated, network-based approaches are elucidating shared biological pathways and creating robust frameworks for novel therapeutic target discovery.

The Genetic and Molecular Landscape of Autism Spectrum Disorder

The Polygenic Architecture and High Heritability of ASD

Quantitative Data on ASD Heritability and Genetic Risk

Table 1: Heritability and Genetic Contributions to ASD

| Genetic Component | Quantitative Measure | Context / Cohort | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Narrow-sense heritability (common variants) | ~60% of liability | Multiplex families | [1] |

| Narrow-sense heritability (common variants) | ~40% of liability | Simplex families | [1] |

| Variance in age at diagnosis explained by common SNPs | ~11% | Independent cohorts | [2] |

| Variance in age at diagnosis explained by sociodemographic factors | <15% | Meta-analyses | [2] |

| Proportion of ASD risk from common variation | ≥50% | Population-based | [3] |

| Proportion of ASD risk from de novo and Mendelian variation | 15-20% | Population-based | [3] |

Table 2: Characteristics of Genetically Correlated ASD Subtypes

| Feature | Factor 1: Earlier-Diagnosed ASD | Factor 2: Later-Diagnosed ASD | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Correlation (rg) | Reference | rg = 0.38 (s.e. = 0.07) with Factor 1 | [2] |

| Core Challenges | Lower social and communication abilities in early childhood | Increased socioemotional/behavioural difficulties in adolescence | [2] |

| Genetic Correlation with ADHD/Mental Health | Moderate | Moderate to high positive correlations | [2] |

| Developmental Trajectory | Difficulties emerge in early childhood, remain stable or modestly attenuate | Fewer difficulties in early childhood, increase in late childhood/adolescence | [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Genomic Analyses

Protocol: Identification of ASD Subtypes via Phenotypic and Genotypic Integration

Objective: To classify clinically relevant and biologically distinct subgroups of ASD by integrating multi-modal phenotypic and genotypic data. [4]

Workflow Summary:

Data Collection:

- Cohort: Utilize a large cohort with matched phenotypic and genetic data (e.g., SPARK cohort).

- Phenotypic Data: Collect extensive data including yes/no traits, categorical responses (e.g., language levels), and continuous measures (e.g., age at developmental milestones).

- Genotypic Data: Obtain whole-genome or exome sequencing data.

Data Modeling and Class Assignment:

- Model Selection: Employ a general finite mixture model. This model can handle different data types individually and integrate them into a single probability for each individual.

- Approach: Use a "person-centered" approach, modeling the full spectrum of an individual's traits together to define groups with shared phenotypic profiles.

- Output: Assign individuals to distinct classes based on the highest probability of class membership.

Biological Validation:

- Pathway Analysis: For each phenotypic class, trace the biological processes and molecular pathways affected by the genetic variants (e.g., neuronal action potentials, chromatin organization).

- Developmental Timing Analysis: Investigate the prenatal vs. postnatal activity of impacted genes within each class to link phenotypic presentation to developmental windows.

Protocol: Cortex-Wide Transcriptomic Analysis in Post-Mortem Brain

Objective: To identify consistent patterns of transcriptomic dysregulation across the cerebral cortex in ASD and assess the attenuation of regional gene expression identity. [5]

Workflow Summary:

Sample Preparation:

- Tissue Source: Acquire post-mortem brain samples from individuals with ASD and neurotypical controls.

- Regions: Sample multiple cortical regions spanning frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes, including association and primary sensory areas (e.g., 11 distinct regions).

- RNA Extraction: Isolate high-quality RNA (e.g., with high RNA Integrity Numbers - RIN).

RNA Sequencing and Quantification:

- Perform RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) on all samples.

- Quantify gene and transcript (isoform) expression levels.

Differential Expression (DE) Analysis:

- Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and transcripts between ASD and control groups, both cortex-wide and within each specific cortical region.

- Use a false discovery rate (FDR) threshold (e.g., < 0.05) to account for multiple testing.

Co-expression Network Analysis:

- Construct weighted gene co-expression networks (WGCNA) across all samples.

- Partition genes into modules (clusters) of highly co-expressed genes.

- Summarize each module's expression profile using its module eigengene.

- Correlate module eigengenes with ASD status and other experimental variables.

Assessment of Attenuated Regional Identity (ARI):

- Systematically contrast gene expression between all unique pairs of cortical regions in controls and ASD.

- Identify genes that typically differentiate cortical regions in controls but show reduced differential expression in ASD.

- Use permutation- or bootstrap-based statistical approaches to test for significant ARI.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Analytical Tools for ASD Genomics Research

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Context of Use |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina Microarrays / RNA-sequencing | Profiling gene expression and identifying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in post-mortem brain tissue. | Transcriptomic analysis of cortical regions. [5] [6] |

| Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) | Comprehensive identification of rare inherited and de novo single nucleotide variants (SNVs), copy number variants (CNVs), and structural variations. | Interrogating the full genetic architecture in multiplex and simplex families. [7] [3] |

| Whole exome sequencing (WES) | Targeted sequencing of protein-coding exons to identify rare, functional variants in known and novel ASD risk genes. | Gene discovery efforts in large cohorts. [7] |

| General Finite Mixture Models | Statistical modeling to integrate diverse data types (binary, categorical, continuous) and identify latent subgroups without a priori hypotheses. | Data-driven subtyping of ASD based on phenotypic and genotypic data. [4] |

| Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) | Systems biology method to organize genes into modules (networks) based on co-expression, revealing underlying biological pathways and key hub genes. | Analyzing transcriptomic data from post-mortem brain to find disease-associated modules. [5] [6] |

| Growth Mixture Models | A statistical technique to identify unobserved latent classes (subgroups) following distinct developmental trajectories based on longitudinal data. | Modeling socioemotional and behavioural trajectories associated with age at ASD diagnosis. [2] |

| Polygenic Risk Scores (PGS) | An aggregate score quantifying an individual's genetic liability for a trait, based on the cumulative effect of many common variants. | Assessing common variant burden and its correlation with traits like language delay. [3] [8] |

| GCTA Software | Tool for estimating the proportion of phenotypic variance explained by all common SNPs (SNP-based heritability). | Estimating narrow-sense heritability of ASD from case-control genotype data. [1] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the relative contribution of common polygenic risk versus rare inherited variants in ASD? A1: Evidence suggests a complex, additive model. Common genetic variation is estimated to explain at least 50% of ASD liability, while rare inherited variants also contribute significantly, particularly in multiplex families. Notably, ASD polygenic score (PGS) is overtransmitted from nonautistic parents to autistic children who also harbor rare inherited variants, indicating combinatorial effects. [3] [1]

Q2: How does the genetic architecture differ between simplex and multiplex ASD families? A2: The genetic architecture differs substantially. Simplex families (one affected individual) show a stronger contribution from de novo mutations and a lower narrow-sense heritability from common variants (~40%). Multiplex families (≥2 affected individuals) show a depletion of de novo mutations, a stronger signal from rare inherited variants, and a higher common variant heritability (~60%). [1]

Q3: Are there distinct genetic factors associated with the age at which an individual receives an ASD diagnosis? A3: Yes. Recent research has decomposed the polygenic architecture of autism into two genetically correlated factors. One factor is associated with earlier diagnosis and lower childhood social-communication abilities. The other is linked to later diagnosis, increased adolescent difficulties, and higher genetic correlations with ADHD and mental-health conditions. Common genetic variants account for ~11% of the variance in diagnosis age. [2]

Q4: What are the core transcriptomic signatures of ASD in the brain, and how widespread are they? A4: Transcriptomic analyses of post-mortem brain tissue reveal widespread dysregulation across the cerebral cortex, not limited to association areas. Core signatures include: 1) Downregulation of synaptic and neuronal genes, 2) Upregulation of immune and glial genes, and 3) Attenuation of Regional Identity (ARI), where the normal molecular differences between cortical regions are diminished. This ARI is most pronounced in posterior (sensory) regions. [5] [6]

Q5: How can I filter for brain-expressed genes most relevant to ASD pathology in my network analysis? A5: Prioritize genes that are:

- Members of co-expression modules (from WGCNA) that are significantly correlated with ASD status in brain tissue. These modules are often enriched for synaptic function or immune response. [5] [6]

- Hub genes within these disease-associated modules, as they are likely functionally important. [6]

- Genes whose expression patterns are spatially correlated with structural neuroimaging alterations (e.g., cortical volume changes) in ASD. [9]

- Genes that show differential expression, particularly in primary sensory cortices like the primary visual cortex (BA17), where some of the strongest transcriptomic signals have been detected. [5]

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the primary function of the SFARI Gene database? SFARI Gene is a core database for autism research, providing curated information on human genes associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). It helps researchers assess the strength of evidence linking specific genes to ASD through its gene scoring system [10].

2. How can I filter for high-confidence ASD risk genes? Use the SFARI Gene Scoring module, which categorizes genes based on the strength of evidence linking them to ASD. A score of '1' represents high confidence, often involving genes linked to syndromic forms of autism. The database is updated regularly (e.g., as of October 2025) and allows you to view and download gene lists by their score category [11] [12].

3. Why is it crucial to filter for brain-expressed genes in ASD research? ASD involves widespread transcriptomic dysregulation across the cerebral cortex. Focusing on brain-expressed genes ensures biological relevance, as many ASD risk genes function in neural development, synaptic transmission, and cortical patterning. Omitting this step can introduce noise from genes not active in the relevant tissue context [5] [13].

4. My network analysis of ASD genes yields unclear results. What could be wrong? This is a common troubleshooting point. Inconsistent results can stem from:

- Inadequate tissue filtering: Your gene list may include candidates not expressed in the brain regions critical for ASD.

- Heterogeneity of data: ASD involves many genetic variants; consider if your analysis accounts for this. Network-based approaches that account for structural differences between healthy and ASD gene networks can be more informative [14].

- Technical variability: Differences in sample processing, sequencing platforms, or data normalization can affect downstream analysis [5] [14].

5. Where can I find transcriptomic data from specific brain regions? Large-scale studies, such as the one published in Nature (2022), provide RNA-sequencing data from up to 11 different cortical areas. These datasets are invaluable for understanding region-specific gene expression and dysregulation in ASD [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Overly Broad Gene List from SFARI

| Symptom | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Network analysis contains many genes with no known neural function; high background noise. | Gene list includes genes scored based on genetic evidence from blood or other tissues, which may not be expressed in the brain. | Filter for brain-expressed genes. Cross-reference your SFARI gene list with brain-specific transcriptomic atlases (e.g., from [5]) or use the EAGLE Score provided in the SFARI Human Gene Module, which can help prioritize genes with predicted brain expression [12]. |

Issue 2: Integrating Genetic and Transcriptomic Data

| Symptom | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Difficulty connecting high-confidence risk genes from SFARI to dysregulated pathways in brain tissue. | A direct link between a genetic mutation and a functional outcome in the brain is complex and not always obvious. | Perform a co-expression network analysis. This method, as used in recent studies [5] [15], groups genes with similar expression patterns into modules. You can then test if SFARI high-confidence genes are significantly enriched within specific, dysregulated modules (e.g., synaptic or immune modules) to uncover functional pathways. |

The table below summarizes key data sources for acquiring and filtering gene lists for ASD network research.

| Resource Name | Data Type | Key Utility in Filtering | Key Metrics / Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| SFARI Gene Database [11] [10] | Curated Gene List | Provides a manually curated starting list of ASD-associated genes with evidence scores. | Gene Score (1-S, 1, 2, 3), Genetic Category (Syndromic, Rare Single Gene, etc.), EAGLE Score (for brain expression prediction). |

| Brain Transcriptomic Atlas (e.g., [5]) | RNA-seq Data | Identifies genes actively expressed in the brain and reveals region-specific (e.g., BA17) and cell-type-specific dysregulation in ASD. | Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs), log2 Fold Change, Co-expression Modules. |

| Spatiotemporal Gene Expression Resource (e.g., STAGE) [13] | Spatial Transcriptomics | Validates the precise spatial and temporal expression of ASD risk genes in intact human brain tissue, crucial for understanding developmental mechanisms. | In situ hybridization data across cortical areas and developmental time points. |

Experimental Protocol: Co-expression Network Analysis for Pathway Identification

This protocol outlines a method to identify dysregulated pathways from a filtered list of brain-expressed ASD genes, based on methodologies from recent literature [5] [15].

1. Input Data Preparation

- Gene Expression Matrix: Obtain a RNA-sequencing dataset from relevant brain tissue (e.g., post-mortem cortex) of ASD cases and neurotypical controls. The 2022 Nature study used 725 samples from 11 cortical areas [5].

- Gene Filtering: Filter the expression matrix to include genes from your high-confidence SFARI list that are robustly expressed in the brain tissue of interest.

2. Network Construction using WGCNA

- Software: Use the Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) R package [15].

- Soft-Thresholding: Choose a soft-thresholding power (β) that achieves a scale-free topology fit index close to 0.90. This emphasizes strong correlations over weak ones.

- Module Detection: Identify modules of highly co-expressed genes using a block-wise approach. Set a minimum module size (e.g., 30 genes) [15].

3. Module Trait Association

- Calculate Module Eigengenes (ME): The first principal component of each module, representing the module's overall expression pattern.

- Correlate MEs with ASD: Statistically correlate module eigengenes with the trait of interest (e.g., ASD vs. Control status) to identify significantly dysregulated modules.

4. Hub Gene Identification & Functional Enrichment

- Identify Hub Genes: Within significant modules, calculate Module Membership (correlation of a gene's expression with the module eigengene). Genes with high membership (e.g., >0.9) are central "hub" genes [15].

- Pathway Analysis: Perform functional enrichment analysis (e.g., using Gene Ontology or KEGG pathways) on genes within dysregulated modules to uncover underlying biology.

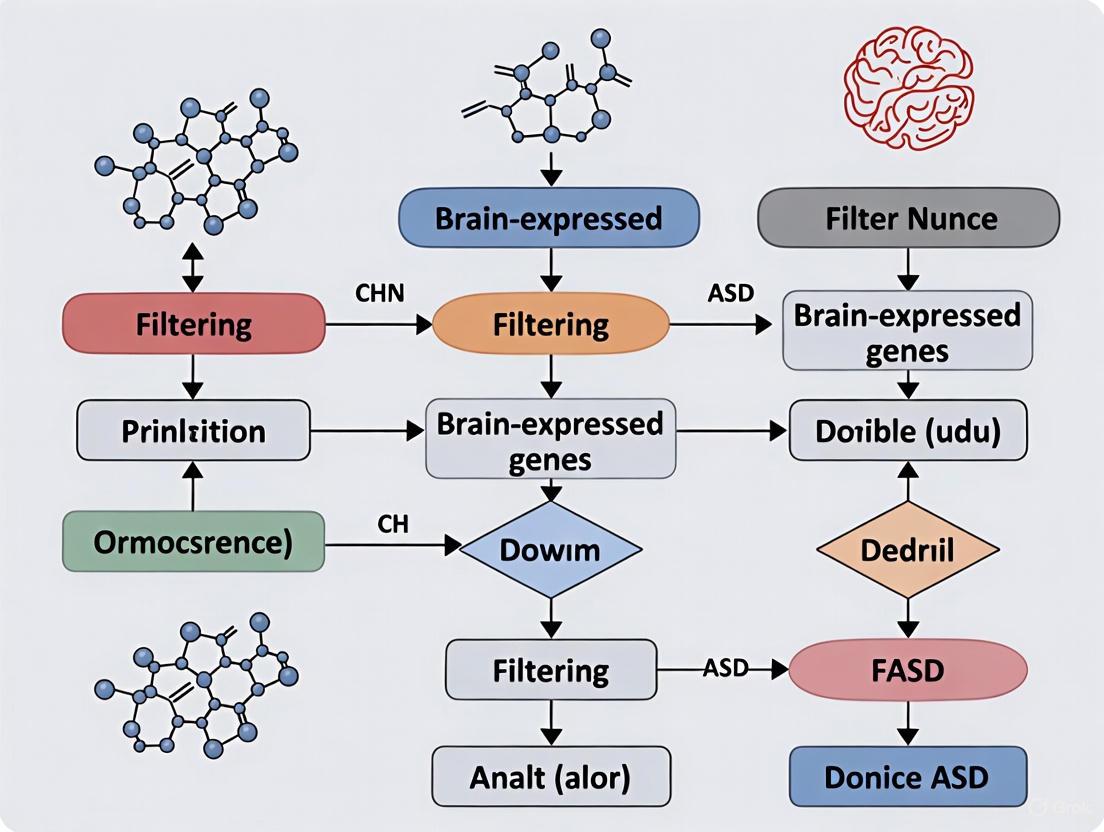

Workflow for identifying dysregulated pathways from SFARI genes using brain transcriptomics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| SFARI Gene Database | Foundational resource for obtaining a curated, evidence-ranked list of ASD candidate genes [11] [10]. |

| Brain Transcriptomic Datasets (e.g., from [5]) | Provide the quantitative expression data needed to filter for brain-active genes and perform co-expression network analysis. |

| WGCNA R Package | Primary software tool for constructing weighted gene co-expression networks and identifying functional modules [15]. |

| STRING Database | Used to build protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks from a list of genes, helping to visualize and analyze physical and functional interactions [15]. |

| Cytoscape with MCODE Plugin | Software environment for visualizing molecular interaction networks and identifying highly interconnected regions (clusters) within large networks [15]. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics Platforms (e.g., NanoString WTA) | Technologies used to validate the spatial localization of gene expression within intact brain tissue, crucial for understanding regional pathology [13]. |

Major Biological Pathways Implicated in ASD Pathogenesis

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs for ASD Network Research

This technical support center is designed within the context of a broader thesis focused on filtering brain-expressed genes for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) network research. It provides targeted troubleshooting guides, frequently asked questions (FAQs), and essential resources for researchers investigating the complex biological pathways underlying ASD pathogenesis.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in ASD Pathway Analysis

Issue 1: Low Overlap Between Gene Lists from Different Studies

- Problem: Candidate gene lists from genome-wide association studies (GWAS), differential expression, and copy number variation (CNV) analyses show minimal overlap, complicating convergence analysis [16].

- Solution: Employ network-based integration methods. Use a network propagation approach on a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network to diffuse signals from seed gene lists. This identifies genes with high network proximity to multiple evidence sources, revealing functional convergence not apparent from simple list overlaps [16].

Issue 2: Heterogeneous Data Obscures Clear Biological Signals

- Problem: ASD's extreme phenotypic and genetic heterogeneity makes it difficult to pinpoint coherent pathway dysregulation when analyzing cohorts as a single group [17] [18].

- Solution: Implement a person-centered, subtyping approach before pathway analysis. Use generative mixture models on broad phenotypic data (e.g., >230 traits) to identify biologically distinct subtypes [18] [19]. Subsequent pathway analysis should be performed within each subtype (e.g., Social/Behavioral, Broadly Affected) to identify subtype-specific genetic programs and dysregulated pathways [18] [19].

Issue 3: Difficulty in Interpreting Results from Network Analysis

- Problem: Large gene networks or interactomes are generated, but key drivers and functional modules are not easily identifiable.

- Solution: Apply module detection algorithms and hub gene analysis.

- Use tools like Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE) to identify highly interconnected subnetworks (potential molecular complexes) within your PPI network [15].

- Perform Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) to find modules of co-expressed genes. Identify hub genes within modules based on high module membership (MM > 0.9) [15].

- Functionally characterize these modules and hub genes using enrichment analysis for Gene Ontology (GO) terms and pathways like KEGG [15] [20].

Issue 4: Integrating Multi-Omics Data for Pathway Discovery

- Problem: Combining genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data types is methodologically challenging.

- Solution: Build a machine learning classifier that uses network-propagated scores from multiple omics datasets as features. For example, use network propagation scores from ten different ASD-associated gene lists (from DGE, DTE, CNV, methylation studies) as a feature set for each gene. Train a random forest model on known high-confidence ASD genes to prioritize new candidate genes and pathways [16].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most statistically enriched signaling pathways in ASD according to current gene sets? A: Systematic enrichment analyses of ASD risk genes (e.g., from SFARI database) consistently highlight several key pathways. The most significantly enriched pathways often include Calcium signaling pathway and Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction [20]. Furthermore, network analyses reveal that the MAPK signaling pathway and Calcium signaling pathway act as interactive hubs, connecting multiple other dysregulated processes [20]. The PI3K-Akt pathway is also prominently implicated in immune-inflammatory responses in the CNS [21].

Q2: How does ASD heterogeneity impact the search for convergent pathways? A: Heterogeneity is a major challenge but does not preclude finding convergence. While over 1200 genes are associated with ASD, their functions often converge on specific biological processes and cell types [17]. Pathway analysis of risk genes shows enrichment in common networks such as synaptic transmission, synapse organization, chromatin (histone) modification, and regulation of nervous system development [17]. The key is to seek "homogeneity from heterogeneity" by stratifying individuals into biologically meaningful subgroups before pathway analysis [17] [18].

Q3: Are there specific pathways linked to distinct clinical subtypes of ASD? A: Yes, emerging research links subtypes to distinct genetic programs. For example, in the Broadly Affected subtype (characterized by severe delays and co-occurring conditions), there is a high burden of damaging de novo mutations. The Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay subtype shows a stronger association with rare inherited variants [18] [19]. Furthermore, the timing of gene expression differs: mutations in genes active later in childhood are more linked to the Social and Behavioral Challenges subtype, which often has a later diagnosis [18].

Q4: What is the role of non-neuronal pathways (e.g., immune, metabolic) in ASD pathogenesis? A: Multisystem involvement is a key feature. Pathway analyses reveal strong enrichment for immune-inflammatory pathways (e.g., cytokine signaling, interferon response) and mitochondrial dysfunction (electron transport chain) [21]. These peripheral disruptions are hypothesized to induce neuroinflammation, which then interacts with core synaptic pathways (e.g., glutamatergic/GABAergic signaling), affecting neurodevelopment and trans-synaptic signaling [22] [21].

Q5: How can I validate if a dysregulated pathway from in silico analysis is relevant to brain function in ASD? A: Couple computational findings with brain imaging genetics. Identify genes whose cortical expression patterns correlate with functional MRI (fMRI) metrics (e.g., fALFF, ReHo) in neurotypical brains. Then, test if this gene-activity correlation is disrupted in post-mortem ASD brain tissue. This can validate pathways involved in excitatory/inhibitory balance (e.g., genes like PVALB) and highlight affected cortical regions like the visual cortex [23].

Table 1: Epidemiological and Genetic Heterogeneity Metrics in ASD

| Metric | Value | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Current Estimated Prevalence | 1% - 2% of children | General population estimates [17] |

| Male-to-Female Ratio | Approximately 4:1 | Highly replicated finding [17] [22] |

| Heritability Estimate | 64% - 91% | Based on twin studies [17] |

| Recurrence Risk in Siblings | 15%-25% (males), 5%-15% (females) | In families with an existing ASD child [17] |

| Cases with Identified Genetic Variants | ~10-20% | Through current genetic testing [17] |

| Genes in SFARI Database | >1200 genes | Catalog of ASD-associated genes [17] |

Table 2: Phenotypic Subtypes Identified in a Large Cohort (SPARK, n=5,392)

| Subtype Name | Approximate Prevalence | Key Phenotypic & Genetic Characteristics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social and Behavioral Challenges | 37% | Core ASD traits, typical developmental milestones, high co-occurring ADHD/anxiety. Genetic disruptions in genes active later in childhood [18] [19]. | |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | 19% | Developmental delays, variable core symptoms, lower psychiatric co-morbidity. Enriched for rare inherited genetic variants [18] [19]. | |

| Moderate Challenges | 34% | Milder core symptoms, typical milestones, low co-occurring conditions. | [18] [19] |

| Broadly Affected | 10% | Severe delays, extreme core symptoms, multiple co-occurring conditions. Highest burden of damaging de novo mutations [18] [19]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Network Propagation & Machine Learning for Gene Prioritization [16]

- Seed Gene Collection: Compile multiple ASD-associated gene lists from orthogonal studies (e.g., differential expression, GWAS, CNV, methylation). Aim for 5-10 lists.

- Network Propagation: Use a high-confidence human PPI network (e.g., from STRING). For each seed list, set initial node values (seeds=1/list_size, others=0). Run a network propagation algorithm (e.g., Random Walk with Restart) with a damping parameter (α=0.8). Normalize the resulting scores using eigenvector centrality.

- Feature Construction: Each gene now has N propagation scores (one from each seed list). This N-dimensional vector is its feature set.

- Model Training: Label high-confidence ASD genes (e.g., SFARI Category 1) as positives. Select an equal number of random non-ASD genes as negatives. Train a Random Forest classifier using the propagation score features.

- Validation: Perform cross-validation. Apply the model to independent gene sets (e.g., SFARI Category 2/3) to assess prioritization performance.

Protocol 2: Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) for Module Discovery [15]

- Data Input: Prepare a gene expression matrix (genes x samples) from your transcriptomic data (e.g., RNA-Seq from neural progenitor cells or neurons).

- Preprocessing & Thresholding: Filter lowly expressed genes. Choose a soft-thresholding power (β) that achieves an approximate scale-free topology (R² > 0.8).

- Network Construction & Module Detection: Construct an adjacency matrix, transform it to a Topological Overlap Matrix (TOM), and perform hierarchical clustering. Use dynamic tree cutting to identify modules of co-expressed genes. Set a minimum module size (e.g., 30).

- Module Eigengene & Merging: Calculate the module eigengene (ME, first principal component) for each module. Merge modules with highly correlated MEs (e.g., correlation > 0.9).

- Hub Gene Identification: For each module, calculate Module Membership (MM, correlation of gene expression with the ME). Genes with high MM (e.g., >0.9) are intra-modular hub genes.

- Functional Enrichment: Perform GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis on genes within each significant module.

Visualization of Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: Convergent Biological Pathways in ASD Pathogenesis

Diagram 2: Integrated Computational Workflow for ASD Pathway Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for ASD Network & Pathway Research

| Item | Function / Description | Key Utility |

|---|---|---|

| SFARI Gene Database | A curated database of ASD-associated genes and variants, categorized by evidence strength. | Primary source for seed genes, positive training sets, and background knowledge [17] [16] [20]. |

| STRING Database | A comprehensive resource of known and predicted Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs). | Used to construct biological networks for propagation and interaction analyses [16] [15]. |

| BrainSpan Atlas | A developmental transcriptome atlas of the human brain. | Provides spatiotemporal gene expression data for feature generation and validating developmental expression patterns [16] [18]. |

| KEGG Pathway Database | A collection of manually drawn pathway maps for metabolism, genetic processes, and signaling. | Standard reference for performing pathway enrichment analysis on gene sets [15] [20]. |

| Gene Ontology (GO) Consortium | A structured, controlled vocabulary (ontologies) for describing gene functions. | Used for functional enrichment analysis of gene modules or prioritized lists (Biological Process, Molecular Function, Cellular Component) [17] [15]. |

| Cytoscape / WGCNA R Package | Software for complex network visualization and analysis / R package for weighted co-expression network analysis. | Essential tools for constructing, visualizing, and analyzing gene networks and identifying modules [15]. |

| Post-mortem Brain Repositories (e.g., Autism BrainNet) | Sources of well-characterized brain tissue from donors with ASD and controls. | Critical for validating gene expression and pathway findings in the human ASD brain [23]. |

| Imaging Genetics Datasets (e.g., ABIDE) | Publicly available repositories combining neuroimaging data and phenotypic information from individuals with ASD. | Enables validation of pathway relevance through brain imaging genetics approaches [23]. |

The Critical Role of Brain-Expressed Genes and Non-Coding Regions

The following tables summarize the core quantitative findings and implicated genomic elements from recent studies on Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

Table 1: Summary of Key Findings on Brain-Expressed Genes in ASD

| Finding | Experimental System | Key Metric/Result | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enriched Expression in Inhibitory Neurons [24] | Human single-cell RNA-seq (fetal & adult brain; cerebral organoids) | ASD candidates show enriched expression in inhibitory neurons; hubs in inhibitory neuron co-expression modules [24]. | Supports the E/I imbalance hypothesis; inhibitory neurons are a major affected subtype [24]. |

| Convergence of Transcriptional Regulators (TRs) [25] | ChIP-seq in developing human & mouse cortex; in vitro CRISPRi. | Five ASD-associated TRs (ARID1B, BCL11A, etc.) share substantial overlap in genomic binding sites [25]. | Suggests a common transcriptional regulatory landscape disruption leading to convergent neurodevelopmental outcomes [25]. |

| Predictive Gene Expression Model [26] | Microarray data from Allen Brain Atlas (190 human brain structures). | Model achieved 84% accuracy in predicting autism-implicated genes [26]. | Provides a baseline transcriptome for prioritizing and validating novel ASD candidate genes [26]. |

Table 2: Implicated Non-Coding Genomic Elements in ASD Risk

| Genomic Element | Definition | Key Findings in ASD | Example Genes/Regions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Accelerated Regions (HARs) [27] | Genomic regions conserved in evolution but significantly diverged in humans. | Rare, inherited variants in HARs substantially contribute to ASD risk, especially in consanguineous families [27]. | HARs near IL1RAPL1 [27]. |

| VISTA Enhancers (VEs) [27] | Experimentally validated neural enhancers. | Patient variants in VEs alter enhancer activity, contributing to ASD etiology [27]. | VEs near OTX1 and SIM1 [27]. |

| Conserved Neural Enhancers (CNEs) [27] | Evolutionarily conserved regions predicted to be neural enhancers. | Rare variation in CNEs adds to ASD risk, implicating disruption of ancient regulatory codes [27]. | - |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions in ASD Gene Network Research

Q: My analysis of a novel ASD gene list shows no significant enrichment for any specific brain cell type. What could be wrong? A: This is a common issue. We recommend troubleshooting the following:

- Data Quality: Ensure your gene list is curated from reliable sources (e.g., SFARI, AutismKB) and is of sufficient size for robust statistical power [24].

- Resolution of Reference Data: The cell-type specificity of ASD genes is often revealed only with high-resolution single-cell transcriptomics data. Using bulk tissue data or data with poorly defined cell types can obscure these signals [24]. Verify that your reference dataset (e.g., from human fetal or adult cortex) includes well-annotated inhibitory and excitatory neuron subtypes [24].

- Methodology: Re-check the parameters of your enrichment analysis tool (e.g., EWCE). Using inappropriate background gene lists or an insufficient number of bootstrap permutations can lead to false negatives [24].

Q: How can I functionally validate the impact of a non-coding variant identified in a patient with ASD? A: The established pipeline involves:

- Enhancer Assays: Clone the wild-type and mutant enhancer sequence (e.g., from a HAR or VISTA enhancer) into a reporter vector (e.g., luciferase assay) and test in a relevant neural cell line or primary culture. A significant change in activity suggests a functional impact [27].

- Genome Editing: Use CRISPR/Cas9 to introduce the patient-specific variant into a human iPSC line. Differentiate these iPSCs into neurons (e.g., cortical cultures) and look for downstream transcriptomic or cellular phenotypes, such as those described in the convergence study (e.g., changes in NeuN+ or GFAP+ cells) [27] [25].

Q: The "E/I imbalance" is frequently cited, but what is the direct molecular and cellular evidence from human genetics? A: Key evidence from human transcriptomic studies includes:

- Expression Enrichment: High-confidence ASD risk genes are not just expressed in neurons, but show significantly enriched expression in inhibitory neurons compared to other cell types [24].

- Co-expression Networks: These same genes are more likely to be hubs in gene co-expression modules that are highly active in inhibitory neurons [24].

- Postmortem Signatures: Upregulated genes in ASD cortex samples are enriched for genes with high basal expression in inhibitory neurons, hinting at a potential change in cellular composition or state [24].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cell-Type Enrichment Analysis for ASD Gene Sets

Objective: To determine if a given set of ASD-associated genes shows enriched expression in specific human brain cell types (e.g., inhibitory neurons).

Materials & Reagents:

- Input Gene List: Curated list of ASD candidate genes (e.g., from SFARI database) [24].

- Reference Transcriptome Data: Single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from healthy human brain tissue. Key datasets used in foundational studies include those from fetal brain, adult brain, and cerebral organoids [24].

- Software Tool: Expression Weighted Cell-type Enrichment (EWCE) package for R/Bioconductor [24].

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Obtain the reference scRNA-seq dataset where cell types have been previously classified by the original authors. Format the data into a matrix of log2(FPKM or TPM) values per gene per cell type [24].

- Run EWCE Analysis:

- Import your ASD gene list and the expression matrix into EWCE.

- Use the

bootstrap.enrichment.testfunction with a high number of permutations (e.g., 10,000) to determine if the ASD genes show statistically significant enriched expression in any cell type compared to random gene sets [24].

- Generate Bootstrap Plots: Use the

generate.bootstrap.plotsfunction to identify the specific genes that drive the enrichment signal in a significant cell type. Genes with a relative expression >1.2-fold greater than the mean bootstrap expression are typically considered "enriched" [24]. - Validation: Perform secondary analysis, such as Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA), on the reference data to identify modules of co-expressed genes and see if the ASD genes are hubs in modules specific to certain cell types [24].

Protocol 2: Investigating Non-Coding Variation in ASD

Objective: To assess the contribution of rare inherited variants in non-coding regions (HARs, VEs, CNEs) to ASD risk.

Materials & Reagents:

- Sample Cohorts: Genomic data from ASD probands and families, with particular attention to simplex (single occurrence) and multiplex/consanguineous families [27].

- Genomic Region Sets: Curated lists of HARs, experimentally validated VISTA enhancers (VEs), and conserved neural enhancers (CNEs) [27].

- Functional Assay Reagents: Luciferase reporter vectors, cell culture materials for neural lineages, and CRISPR/Cas9 components for genome editing [27].

Methodology:

- Variant Identification: Perform whole-genome or targeted sequencing on patient cohorts. Filter for rare, inherited variants that fall within the defined HAR, VE, and CNE regions [27].

- Association Analysis: Test for enrichment of these variants in ASD probands compared to controls. This analysis has shown that the contribution is most substantial in probands from consanguineous families, which enriches for recessive inheritance patterns [27].

- Functional Characterization:

- Enhancer Activity Assay: Clone the wild-type and variant-containing genomic sequence upstream of a minimal promoter driving a luciferase reporter. Transfert into a relevant neural cell model and measure reporter activity. Altered activity indicates a functional impact on the enhancer [27].

- CRISPR-based Validation: Introduce the variant into a human iPSC line using CRISPR/Cas9 homology-directed repair. Differentiate the iPSCs into cortical neurons and analyze for phenotypic changes, such as alterations in the transcriptome (e.g., RNA-seq) or in the ratio of neuronal and glial cell types [25].

Signaling Pathways & Workflows

Diagram 1: Transcriptional Convergence in ASD Pathogenesis

Diagram 2: Functional Analysis of Non-Coding Variants

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for ASD Gene Network Studies

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Key Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell RNA-seq Datasets [24] | Profiling gene expression across diverse cell types in the human brain to establish a baseline and identify cell-type-specific enrichment. | Datasets from fetal brain, adult brain, and cerebral organoids are critical. Public repositories like the Allen Brain Atlas are key sources [26]. |

| Expression Weighted Cell-type Enrichment (EWCE) [24] | A statistical R package to test if a gene set shows significant enriched expression in a specific cell type. | The core tool for quantifying cell-type enrichment from scRNA-seq data. Uses bootstrap sampling for significance testing [24]. |

| ChIP-seq for Transcriptional Regulators (TRs) [25] | Mapping the genomic binding sites of ASD-associated TRs to identify shared regulatory targets. | Applied to TRs like ARID1B, BCL11A, FOXP1, TBR1, and TCF7L2 in developing cortex, revealing substantial binding site overlap [25]. |

| CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi) [25] | For targeted knockdown of specific genes (e.g., ARID1B, TBR1) in model systems to study downstream effects. | Used in mouse cortical cultures to validate convergent biology and model haploinsufficiency [25]. |

| Reporter Assay Vectors [27] | Testing the functional impact of non-coding variants on enhancer activity. | Typically luciferase-based systems; used to confirm that patient variants in HARs/VEs alter enhancer function [27]. |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [27] [25] | Generating human neuronal models for functional validation of genetic findings. | Can be genetically edited (via CRISPR/Cas9) to introduce patient variants and then differentiated into relevant neuronal subtypes for phenotyping [27]. |

Computational Methods for Gene Prioritization: From Networks to Machine Learning

Network Propagation on Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Core Network Propagation Protocol for ASD Gene Discovery

Objective: To prioritize novel Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) risk genes by propagating known associations through a Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network [28].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Seed Gene Selection: Compile a list of known high-confidence ASD-associated genes from trusted sources (e.g., SFARI Gene database). These serve as the initial seeds for the propagation algorithm [28].

- Network Preparation: Obtain a comprehensive human PPI network. The network used by Zadok et al. contained 20,933 proteins and 251,078 interactions [28].

- Initialization: Assign an initial probability score to each protein in the network. Seed proteins from the known ASD list are typically assigned a non-zero score (e.g., 1/s, where

sis the number of seeds), while all other proteins are set to zero [28]. - Propagation Execution: Apply a network propagation algorithm, such as random walk with restart. The propagation process is governed by the formula and a damping parameter (often set to α=0.8), which controls the influence of a node's neighbors versus its initial state [28].

- Score Normalization: Normalize the resulting propagation scores using a method like eigenvector centrality to account for biases introduced by highly connected proteins (hubs) in the network [28].

- Gene Prioritization: Rank all genes in the network based on their final propagation score. Genes with high scores are considered strong novel candidates for ASD association [28].

Protocol for Constructing Cell-Type-Specific PPI Networks

Objective: To generate neuronal-specific PPI networks for ASD risk genes, overcoming the limitation of non-neural cellular models [29].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Cell Generation: Differentiate human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) into excitatory neurons using neurogenin-2 (NGN2) induction [29].

- Protein Extraction and Immunoprecipitation (IP): For each ASD index protein (bait), perform IP using a specific antibody in the induced neuronal cell lysates [29].

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): Identify proteins that co-precipitate with the bait protein using Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [29].

- Interaction Validation: Validate a subset of identified interactions using orthogonal methods like Western blotting. Assess technical replication (e.g., >80% replication rate) [29].

- Network Mapping and Analysis: Construct the PPI network with index proteins and their identified interactors. Analyze the network to identify highly interconnected nodes and functionally convergent pathways [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for PPI Network Propagation Studies in ASD.

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| PPI Network Datasets | A comprehensive graph of known protein interactions used as the scaffold for propagation. | Human PPI network from Signorini et al. (2021) (20,933 proteins) [28]. |

| ASD Gene Seeds | Curated list of high-confidence genes associated with ASD to initialize the propagation algorithm. | SFARI Gene database (Categories S & 1 as positives) [28]. |

| Software for Propagation | Tools to execute and visualize the network propagation algorithm and resulting networks. | NAViGaTOR (for efficient, large-network visualization); Cytoscape (extensible platform with plugins for analysis) [30]. |

| Validation Databases | Resources of experimentally derived, cell-type-specific interactions to validate computational predictions. | Neuronal PPI networks from induced human neurons (e.g., Pintacuda et al. 2023) [29]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: My network propagation results include many well-known, highly connected genes. How can I distinguish truly novel ASD candidates from generic network hubs?

Issue: The algorithm is biased towards high-degree nodes, making it difficult to identify novel, non-hub genes.

Solution:

- Apply Normalization: Always use normalization techniques, such as eigenvector centrality, to mitigate the bias introduced by nodes with a high number of connections [28].

- Leverage Cell-Type-Specific Data: Filter your results or use as a seed list proteins found in neuronal-specific PPI studies. A significant finding from recent research is that ~90% of interactions in human neurons are novel and not found in standard databases, which can help break away from generic hub bias [29].

- Functional Enrichment Analysis: Use tools like g:Profiler to perform enrichment analysis on your top-ranked genes. Prioritize gene lists that show significant enrichment for pathways strongly linked to ASD etiology, such as chromatin organization, histone modification, and neuron cell-cell adhesion [28].

FAQ 2: I am getting a low replication rate when I validate predicted interactions in my lab's cellular models. What could be the cause?

Issue: Discrepancy between computational predictions and experimental validation.

Solution:

- Check Cell-Type Relevance: The PPI network used for propagation may not reflect the biology of your validation model. A study comparing PPIs in stem-cell-derived neurons versus postmortem cerebral cortex found only ~40% replication, highlighting the impact of cell type and developmental stage [29].

- Consider Isoform Specificity: Ensure your validation model expresses the correct protein isoform. Research on ANK2 in ASD showed that many disease-relevant interactions depend on a single neuron-specific giant exon, which would be missed if the wrong isoform is studied [29].

- Verify Experimental Conditions: Confirm that your IP-MS protocol is optimized for detecting true interactions and that controls are in place to rule out non-specific binders [29] [31].

FAQ 3: How do I choose the right PPI assay to validate interactions I discover through network propagation?

Issue: Selecting an appropriate experimental method for validation.

Solution: The choice depends on your protein of interest and research goal. Below is a comparison of common methods.

Table 2: Guide to Selecting a PPI Validation Assay [31].

| Assay | Principle | Best For | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) | Reconstitution of a transcription factor via protein interaction. | Detecting binary, intracellular interactions; scalable screening. | Interactions may not occur in yeast; proteins must localize to nucleus. |

| Membrane Yeast Two-Hybrid (MYTH) | Split-ubiquitin system reconstitution. | Studying full-length membrane proteins and their interactions. | Limited to membrane proteins; can have false positives. |

| Affinity Purification Mass Spectrometry (AP-MS) | Purification of a protein complex and identification of components by MS. | Uncovering protein complexes in a near-native context. | Cannot distinguish direct from indirect interactions. |

FAQ 4: My network is very large, and the visualization is cluttered, making interpretation difficult. What can I do?

Issue: Poor visualization of large, complex PPI networks.

Solution:

- Use Advanced Visualization Tools: Employ software like Cytoscape or NAViGaTOR. Cytoscape is open-source and highly extensible via plugins for analysis and visualization, while NAViGaTOR offers high-performance rendering for huge networks [30].

- Apply Layout Algorithms: Use force-directed or organic layout algorithms that position connected nodes closer together, which can help reveal underlying network structures like clusters or complexes [30].

- Filter and Cluster: Before visualization, filter the network based on propagation scores or confidence metrics. Apply integrated clustering algorithms to identify and then visualize distinct functional modules instead of the entire network [30].

Quantitative Data & Performance Metrics

Table 3: Performance Metrics of a Network Propagation Model for ASD Gene Prediction [28].

| Metric | Value | Description / Implication |

|---|---|---|

| AUROC (Area Under the ROC Curve) | 0.87 | Measures the overall ability to distinguish between ASD-associated and non-associated genes. A value of 0.87 indicates high accuracy. |

| AUPRC (Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve) | 0.89 | A more informative metric than AUROC for imbalanced datasets (where true positives are rare). A value of 0.89 is considered excellent. |

| Optimal Classification Cutoff | 0.86 | The score threshold that maximizes the product of specificity and sensitivity, used for making binary predictions. |

| Performance vs. ForecASD (AUROC) | 0.91 vs. 0.87 | The described propagation-based method outperformed a previous state-of-the-art predictor (forecASD) in a comparative analysis [28]. |

Workflow & Pathway Visualizations

Network Propagation Workflow

Neuronal PPI Mapping Pipeline

Gene Co-expression Network Analysis with WGCNA and Leiden Algorithms

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

Data Preprocessing and Network Construction

Q1: My WGCNA analysis on human brain transcriptome data is running very slowly or crashing. How can I improve computational efficiency?

A: Performance issues are common with large-scale transcriptomic data. Implement these solutions:

- Filter genes first: Prior to WGCNA, filter out lowly expressed genes. Retain only genes with counts per million (CPM) > 1 in a sufficient number of samples to reduce dataset size and noise [32].

- Subset to relevant genes: For focused studies, such as on Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), filter your gene list to brain-expressed genes or candidate genes from databases like SFARI before network construction. This dramatically reduces computational load [33] [34].

- Leverage high-performance computing: For very large datasets, use a computing cluster. WGCNA can be parallelized to utilize multiple processors [32].

- Consider alternative algorithms: For extremely large datasets, emerging methods like Weighted Gene Co-expression Hypernetwork Analysis (WGCHNA) are designed for better computational efficiency and can capture higher-order gene interactions [35].

Q2: How do I choose the right soft-power threshold for building a scale-free network in brain-expressed gene data?

A: Selecting the soft-power threshold (β) is critical for constructing a biologically meaningful, scale-free network.

- Standard Procedure: Use the

pickSoftThresholdfunction in the WGCNA R package. The goal is to choose the lowest power for which the scale-free topology fit index (R²) reaches a plateau, typically above 0.80 or 0.90 [32]. - Troubleshooting a Low Fit: If the scale-free topology fit is low, it does not necessarily mean the analysis is invalid. Focus on the resulting gene modules and their biological coherence. The network can still yield valuable insights [36].

- Refer to Established Protocols: Follow detailed, step-by-step protocols for soft-threshold selection, which include code and diagnostic plot interpretation [32].

Q3: What are the key differences between a co-expression network and a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network?

A: These networks capture different biological relationships, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Co-expression and PPI Networks

| Feature | Co-expression Network | PPI Network |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship Type | Transcriptional coordination & regulation [36] | Physical & functional interactions between proteins [36] |

| Biological Level | Upstream (mRNA expression) [36] | Downstream (protein function) [36] |

| Input Data | Gene expression matrix (e.g., RNA-seq) [36] | List of genes/proteins (e.g., from differential expression) [36] |

| Primary Insight | Shared regulatory control & functional groups [36] | Mechanistic pathways & protein complexes [36] |

Module Detection and Analysis

Q4: The Louvain algorithm is producing disconnected clusters in my gene modules. How can I ensure well-connected communities?

A: This is a known flaw of the Louvain algorithm. The recommended solution is to use the Leiden algorithm.

- The Problem: The Louvain algorithm can assign nodes to a cluster even if they are not connected, leading to poorly defined modules [37].

- The Solution: The Leiden algorithm guarantees well-connected clusters and often runs faster than Louvain. It also produces higher-quality partitions that are "subset optimal" [37].

- Implementation:

Q5: How can I identify key hub genes within a co-expression module relevant to ASD pathology?

A: Hub genes are highly connected genes within a module and are often critical for the module's function.

- Identification Metrics: Hub genes are typically identified by high intramodular connectivity (kWithin) or high module membership (MM), which measures how well a gene's expression correlates with the module's eigengene [40] [32].

- Validation: Combine network statistics with functional evidence. True hub genes should also be:

- Downstream Analysis: Export the top hub genes and visualize the subnetwork using tools like Cytoscape for further inspection [32].

Functional Interpretation and Validation

Q6: My gene modules are not showing significant enrichment in standard functional databases. What alternative strategies can I use?

A: A lack of standard functional enrichment can occur, especially for novel or brain-specific processes.

- Refine Your Background Gene Set: Instead of using the whole genome as background, use a list of brain-expressed genes. This reduces dilution from irrelevant genes and increases detection power for neurological functions.

- Leverage Brain-Specific Resources:

- Use the BrainSpan Atlas to analyze the spatiotemporal expression patterns of your module genes. Co-expressed genes often show similar developmental trajectories [33].

- Check for enrichment in cell-type-specific markers (e.g., neurons, glia) from brain single-cell RNA-seq studies.

- Investigate Other Ontologies: Look beyond GO Biological Process and KEGG. Try enrichment in:

- Mouse Phenotype (e.g., MGI) for behavioral or neurological traits.

- Disease Ontology or DisGeNET for associations with neurodevelopmental disorders.

- Protein-protein interaction networks to see if module genes form a tight physical complex, even if the pathway is not yet annotated [33].

Q7: How do I integrate and visualize my co-expression network results effectively?

A: Effective visualization is key to interpretation and communication.

- Cytoscape for Module Visualization: Cytoscape is the standard tool for visualizing gene networks. You can export module genes and their connection strengths from WGCNA and import them into Cytoscape to visualize hub genes and network topology [32].

- Gephi for Large Network Overview: For a high-level view of all modules, use Gephi.

- Export your network in

graphmlformat. - Import it into Gephi.

- Use the Leiden algorithm (via a plugin) to detect communities.

- Color nodes by cluster and resize them by degree centrality.

- Apply a force-directed layout like ForceAtlas2 for an intuitive visualization [38].

- Export your network in

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a Co-expression Network from Brain Transcriptome Data

This protocol outlines the steps to build a gene co-expression network using WGCNA, specifically tailored for analyzing brain-expressed genes in ASD research [32].

1. Software and Data Preparation

- Software: Install R (>4.2.0) and required packages:

WGCNA: Core package for network analysis.clusterProfiler: For functional enrichment analysis.org.Hs.eg.db: For gene identifier mapping [32].

- Data Input: Start with a normalized gene expression matrix (e.g., TPM or FPKM from RNA-seq) where rows are genes and columns are samples. Filter to include only brain-expressed genes.

2. Data Preprocessing and Filtering

- Remove Lowly Expressed Genes: This reduces noise and computational load.

- Check for Outliers: Use hierarchical clustering to identify and remove any outlier samples that may distort the network.

3. Network Construction and Module Detection

- Choose Soft Power: Use the

pickSoftThresholdfunction to select a power (β) that approximates a scale-free topology. - Build the Network: Construct an adjacency matrix and transform it into a Topological Overlap Matrix (TOM) to minimize spurious connections.

- Detect Modules: Perform hierarchical clustering on the TOM-based dissimilarity matrix and use the Leiden algorithm (or dynamic tree cut) to identify gene modules [32] [37].

4. Downstream Analysis

- Relate Modules to Traits: Correlate module eigengenes with external traits (e.g., disease status, brain region).

- Identify Hub Genes: Calculate intramodular connectivity for genes within modules of interest.

- Functional Enrichment: Use

clusterProfilerto run GO and KEGG enrichment analysis on key modules [32].

Protocol 2: Integrating Leiden Algorithm for Improved Module Detection

This protocol supplements the WGCNA workflow by applying the Leiden algorithm to ensure well-connected gene modules [37].

1. Export Network from WGCNA

- After constructing the TOM, export the network for a specific module or the entire network in a format compatible with network visualization tools (e.g.,

graphml).

2. Community Detection with Leiden in Gephi

- Import: Open the

graph.graphmlfile in Gephi. - Run Statistics: In the

Statisticstab, run Average Degree and the Leiden Algorithm.- Settings: Quality function = Modularity; Resolution = 1.0 [38].

- Visualize:

- In the

Appearancepane, selectNodes > Partition, and chooseClusterto color the graph by the Leiden communities. - Select

Nodes > Ranking, chooseDegree, and set min/max sizes to resize nodes by connectivity [38].

- In the

- Layout: Use the

ForceAtlas2layout withPrevent Overlapchecked to achieve a clear visualization [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for ASD Co-expression Network Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| BrainSpan Atlas | Transcriptome Database | Provides developmental stage-specific and brain region-specific gene expression data for filtering and validation [33]. |

| WGCNA R Package | Software Package | Core tool for constructing weighted co-expression networks, detecting modules, and calculating hub genes [32]. |

| Leiden Algorithm | Clustering Algorithm | A superior community detection method that guarantees well-connected modules in a network [37]. |

| Cytoscape | Network Visualization Tool | Visualizes gene co-expression networks and subnetworks, allowing for interactive exploration of hub genes [32]. |

| clusterProfiler | R Package | Performs functional enrichment analysis (GO, KEGG) on gene modules to interpret biological meaning [32]. |

| SFARI Gene Database | Gene Database | A curated database of ASD candidate genes used for pre-filtering or validating network findings [34]. |

| Gephi | Network Visualization Tool | Provides powerful layouts and clustering algorithms (like Leiden) for visualizing large, entire networks [38]. |

Integrating Multi-Omics Data with Random Forest and SVM Classifiers

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary data preprocessing steps before integrating multi-omics data for classifier analysis? Before analysis, raw data must undergo rigorous preprocessing. This includes normalization to address technical variations (e.g., using DESeq2's median-of-ratios for RNA-seq or quantile normalization for proteomics), batch effect correction with tools like ComBat or Limma, and handling of missing values through imputation or filtering. Standardizing data into a compatible format (e.g., sample-by-feature matrices) is crucial for successful integration [41] [42].

Q2: How do I choose between early, intermediate, and late integration strategies for my multi-omics dataset? The choice depends on your research goal and data structure. Early Integration concatenates all omics features into a single matrix for analysis, which is simple but can be affected by data heterogeneity. Intermediate Integration uses methods like MOFA+ to project different omics into a shared latent space, preserving data structure. Late Integration involves building separate models for each omics type and combining the results, which handles data heterogeneity well but may miss inter-omics interactions [43] [44].

Q3: What are the common pitfalls when training Random Forest on high-dimensional multi-omics data, and how can I avoid them?

Common pitfalls include overfitting due to the "large p, small n" problem, class imbalance, and ignoring feature correlations. To mitigate these: perform strict feature selection before training; use stratified sampling or balanced class weights; tune hyperparameters (like max_features and n_estimators) via cross-validation; and validate findings on an independent test set [41] [45].

Q4: Why might my SVM model perform poorly on integrated multi-omics data, and how can I improve it?

Poor performance often stems from inappropriate kernel choice, improper parameter tuning, or high dimensionality. To improve your model: scale features before training; use grid search to optimize the regularization parameter C and kernel parameters; consider linear kernels for very high-dimensional data; and employ feature selection or extraction (like PCA) to reduce dimensionality and highlight relevant features [45].

Q5: In the context of ASD research, how can I ensure my biological findings are robust? To ensure robustness: account for major confounders like sex, age, and post-mortem interval in your model; perform rigorous cross-validation and external validation if possible; apply multiple testing corrections to control false discovery rates; and integrate findings with known biological knowledge of ASD, such as synaptic or immune pathways, to assess coherence [41] [46].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Classifier Performance (Accuracy/Precision) on Integrated Data

Problem: Your Random Forest or SVM model shows low predictive accuracy after integrating transcriptomic and proteomic data from ASD brain samples.

Solution:

- Diagnose Data Quality: Check for and correct batch effects that may introduce technical noise. Use PCA plots colored by batch to visualize unwanted variation [41].

- Re-evaluate Feature Selection: High-dimensional omics data contains many irrelevant features. Apply univariate (e.g., ANOVA) or model-based (e.g., Random Forest feature importance) selection to filter for the most informative features, such as brain-expressed genes relevant to ASD [41].

- Optimize Hyperparameters: For Random Forest, increase

n_estimatorsand tunemax_depth. For SVM, use a cross-validated grid search to find the optimalCandgammavalues [45]. - Validate Integration Strategy: If using early integration, the scale difference between omics can confuse the model. Try intermediate integration (e.g., using MOFA+) to extract coordinated signals first [43].

Issue 2: Inconsistent Results Between Random Forest and SVM

Problem: Random Forest and SVM classifiers yield divergent feature importance and prediction outcomes on the same dataset.

Solution:

- Understand Algorithmic Differences: Random Forest is robust to non-informative features and can model complex interactions, while SVM is sensitive to feature scaling and aims to find a global decision boundary. divergent results can reveal different aspects of the data [45].

- Inspect Feature Space: Apply dimensionality reduction (t-SNE, UMAP) to visualize how the two algorithms separate the classes. This can reveal if one model is capturing nonlinear patterns the other misses.

- Benchmark on a Single Omic: Run both classifiers on a single, well-understood omic layer (e.g., transcriptomics) to isolate whether the inconsistency stems from data integration or the algorithms themselves.

Issue 3: Technical Errors During Data Integration and Model Training

Problem: You encounter specific computational errors, such as memory issues, shape mismatches, or failure to converge.

Solution:

- Memory Errors with Large Datasets:

- Solution: For Random Forest, reduce the feature dimension first or use the

max_samplesparameter. For SVM, consider using a linear SVM (LinearSVCin scikit-learn) which is more memory-efficient for high-dimensional data [45].

- Solution: For Random Forest, reduce the feature dimension first or use the

- Data Shape Mismatch in Early Integration:

- Problem: Matrices from different omics (e.g., genomics and metabolomics) cannot be concatenated due to different sample sizes.

- Solution: Ensure you are using matched samples. The integration must be performed on the same set of biological samples across all omics layers. Re-check your sample IDs and alignment [42] [44].

- SVM Failing to Converge:

- Problem: The optimization algorithm hits the iteration limit.

- Solution: Increase the

max_iterparameter, scale your features (usingStandardScaler), or try a simpler linear kernel [45].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Key Preprocessing and Normalization Methods

The table below summarizes standard methods for different data types, crucial for preparing data for classifiers.

Table 1: Standard Preprocessing Methods for Different Omics Types

| Omics Data Type | Common Normalization Methods | Key Tools/Packages | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomics (RNA-seq) | Median-of-ratios, TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) | DESeq2, edgeR [41] | Corrects for library size and composition biases |

| Proteomics (Mass Spec) | Quantile Normalization, Variance-Stabilizing Normalization | Limma, specific vendor software [41] | Mitigates technical variation from sample handling and instrumentation |

| Metabolomics | Pareto Scaling, Log Transformation | MetaboAnalyst [46] | Reduces the influence of high-intensity metabolites and makes data more normally distributed |

| Epigenomics (Methylation) | Background correction, Subset Quantile Normalization | Minfi, SWAN [41] | Adjusts for technical differences between arrays/probes |

Workflow for Multi-Omics Integration in ASD Research

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for integrating multi-omics data to filter brain-expressed genes in ASD research using Random Forest and SVM.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for Multi-Omics Analysis in ASD Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| DESeq2 / edgeR | R packages for normalization and differential expression analysis of RNA-seq data. | Used to identify dysregulated brain-expressed genes in ASD vs. control cohorts [41]. |

| MOFA+ | Tool for unsupervised intermediate integration of multiple omics layers. | Discovers latent factors that capture shared variation across omics, revealing coordinated molecular pathways [41] [44]. |

| ComBat / Limma | Statistical methods for adjusting for batch effects in high-dimensional data. | Critical for combining datasets from different sequencing runs or labs to avoid technical confounders [41]. |

| Random Forest | Ensemble machine learning classifier for feature selection and prediction. | Robust for high-dimensional data; provides intrinsic measure of feature importance for gene ranking [45]. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Classifier that finds an optimal hyperplane to separate classes. | Effective for binary classification tasks (e.g., ASD vs. Control) when carefully tuned [45]. |

| 16S rRNA Sequencing | Profiling microbial community composition in gut microbiome studies. | Used in ASD research to link gut microbiota alterations (e.g., diversity loss) with the disorder [46]. |

| Metaproteomics Pipeline | Identification and quantification of proteins from complex microbial communities. | Helps identify bacterial proteins (e.g., from Bifidobacterium) that may interact with host physiology in ASD [46]. |

| scikit-learn | Python library providing implementations of RF, SVM, and many other ML tools. | The standard library for building and evaluating machine learning models [45]. |

Technical Support & FAQs

Q1: Our team has identified a module of co-expressed genes from brain tissue. What is the most critical first step to assess its potential for drug repositioning? A1: The most critical first step is to perform enrichment analysis for genetically associated variants [47]. This determines if the gene community is enriched for genes previously linked to ASD, which validates its biological relevance and increases the likelihood that targeting it will have a therapeutic effect. A community lacking this enrichment may not be causally linked to the disorder.

Q2: When using transcriptomic data from public repositories like GEO, what preprocessing steps are essential to ensure reliable community detection?

A2: Essential preprocessing includes log2 transformation and quantile normalization of the data to make samples comparable [47]. Furthermore, it is crucial to correct for batch effects using methods like the ComBat function from the sva package in R, which uses adjustment coefficients calculated from control samples to remove technical variation not due to biological signal [47].

Q3: We have a promising gene community but a limited number of patient samples. How can we build a robust machine learning model for classification without overfitting? A3: You can implement a robust machine learning framework with feature selection [47]. This involves using a 5-fold cross-validation procedure, coupled with a feature selection algorithm like Boruta, to identify the most predictive genes within your community before training the final classifier, such as a Random Forest [47]. This process helps prevent overfitting by focusing on the most robust features.

Q4: A drug we are investigating for repurposing showed efficacy in our model but has a known risk of cardiac arrhythmias. Should we terminate the project? A4: Not necessarily. A drug's history should inform, not necessarily halt, repurposing efforts. For example, Thioridazine was withdrawn from the market for cardiac arrhythmias but is still actively researched in drug repurposing for other indications [48]. The decision should be based on a risk-benefit analysis for the new disease, considering factors like dosage, formulation, and the severity of the condition being treated.

Q5: How can we interpret a complex machine learning model to understand which genes in our community are driving the ASD classification? A5: Employ eXplainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) techniques. The SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method can be applied to measure and quantify the contribution of each gene to the classification model's output [47]. This helps allocate credit among genes and identifies the most pivotal players within your causal community.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Building a Gene Co-Expression Network from Brain Transcriptomic Data

Objective: To identify stable communities of co-expressed genes from post-mortem brain tissue of ASD and control subjects.

Materials:

- Data Source: Publicly available brain microarray dataset (e.g., GSE28475 from GEO) [47].

- Software: R with packages Bioconductor,

igraph, andsva[47].

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Download the dataset and apply batch effect correction using the

ComBatfunction, estimating adjustments on control samples only. Then, log2 transform and quantile normalize the data [47]. - Network Construction: Construct a complex network where genes are nodes. Create a link between two genes if the Pearson’s correlation between their expression profiles is significant (e.g., at a 99% confidence interval). Weight the links based on the correlation value [47].

- Community Detection: Apply the Leiden algorithm to partition the network into communities. Run the algorithm multiple times under different random initializations to evaluate the stability of the partitions. A hierarchical strategy can be employed, repeatedly running the algorithm to break large communities into smaller, more biologically interpretable subgroups [47].

Protocol 2: Validating Gene Communities with a Machine Learning Pipeline

Objective: To determine if the identified gene communities can robustly classify ASD versus control samples.

Materials:

- Data: Preprocessed expression data and the gene lists for each community from Protocol 1.

- Software: R with packages

BorutaandRandomForest[47].

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: For each gene community, extract the expression matrix for the genes in that community across all samples (ASD and control).

- Feature Selection: Apply the Boruta algorithm to the training set (using 5-fold cross-validation) to identify genes that are statistically significant predictors of ASD status [47].

- Model Training and Validation: Train a Random Forest classifier using the genes confirmed by Boruta. Evaluate model performance (e.g., accuracy, sensitivity) on the cross-validation folds and on an independent test dataset (e.g., GSE28521) to ensure generalizability [47].

- Model Interpretation: Use the SHAP method on the trained model to explain the output and quantify the importance of each gene in the community to the classification decision [47].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of a Machine Learning Pipeline on ASD Transcriptomic Data [47]

| Dataset | Number of Genes Used | Model Description | Classification Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSE28475 (Full Feature Set) | All significant genes from communities | Random Forest with Boruta feature selection | 98% ± 1% |

| Independent Test Set (GSE28521) | All significant genes from communities | Random Forest with Boruta feature selection | 88% ± 3% |

| Independent Test Set (GSE28521) | Causal Community 1 (43 genes) | Random Forest with Boruta feature selection | 78% ± 5% |

| Independent Test Set (GSE28521) | Causal Community 2 (44 genes) | Random Forest with Boruta feature selection | 75% ± 4% |

Table 2: Key Characteristics of Transcriptomic Datasets Used in ASD Drug Repurposing Research [47]

| Dataset (GEO ID) | Sample Type | Total Samples | ASD Samples | Control Samples | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE28475 | Post-mortem prefrontal cortex | 104 | 33 | 71 | Training & Discovery |

| GSE28521 | Post-mortem prefrontal cortex | 58 | 29 | 29 | Independent Validation |

Signaling Pathways & Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for ASD Gene Network & Drug Repurposing Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Post-mortem Brain Tissue | Source for transcriptomic analysis to identify dysregulated gene expression in ASD vs. control. | Prefrontal cortex tissue; datasets like GSE28475 and GSE28521 from GEO [47]. |

| Microarray Datasets | Provide genome-wide gene expression data for building co-expression networks and machine learning. | Publicly available from GEO; require preprocessing (normalization, batch correction) [47]. |

| R Statistical Software | Primary platform for data preprocessing, network analysis, community detection, and machine learning. | Requires packages: sva (batch correction), igraph (networks), Boruta (feature selection), RandomForest (classification) [47]. |

| Leiden Algorithm | A community detection algorithm used to partition the gene co-expression network into stable, relevant subgroups [47]. | Implemented in R; superior for finding stable partitions in large networks. |

| Boruta Algorithm | A feature selection algorithm based on Random Forests, used to identify genes within a community that are statistically significant predictors of ASD [47]. | Helps reduce dimensionality and prevent overfitting by confirming or rejecting feature importance. |