Network Analysis in Systems Biology: From Foundations to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of network analysis methodologies and their transformative applications in systems biology and drug discovery.

Network Analysis in Systems Biology: From Foundations to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of network analysis methodologies and their transformative applications in systems biology and drug discovery. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores foundational concepts of biological networks, details computational methods for network inference and multi-omics integration, addresses key analytical challenges, and examines validation frameworks. By synthesizing current research and emerging trends, this resource serves as both an introductory guide and reference for implementing network-based approaches to understand complex biological systems and accelerate therapeutic development.

Understanding Biological Networks: Systems-Level Foundations for Complex Disease Analysis

The study of biological systems has undergone a fundamental transformation, moving from a traditional reductionist approach to an integrative network-based paradigm. Reductionism, which has dominated science since Descartes and the Renaissance, is a "divide and conquer" strategy that assumes complex problems are solvable by breaking them down into smaller, simpler components [1]. This approach has been tremendously successful, epitomized by the triumphs of molecular biology, such as demonstrating that DNA alone is responsible for bacterial transformation [2]. However, reductionism faces inherent limitations when confronting the emergent properties of biological systems—characteristics of the whole that cannot be predicted from studying isolated parts [2]. The systems perspective addresses these limitations by appreciating the holistic and composite characteristics of a problem, recognizing that "the forest cannot be explained by studying the trees individually" [1].

This shift has been catalyzed by technological advances, particularly high-throughput technologies that generate abundant data on system elements and interactions [3]. The completion of the human genome project revealed that human complexity arises not just from our 30,000-35,000 genes but from the intricate regulatory networks and interactions between their respective products [1]. Understanding phenotypic traits requires examining the collective action of multiple individual molecules, leading to the emergence of systems biology as a discipline that incorporates technical knowledge from systems engineering, nonlinear dynamics, and computational science [1]. This whitepaper examines the core principles underlying this paradigm shift and provides practical methodologies for implementing network-based approaches in biological research.

Core Principles: Contrasting the Two Paradigms

Fundamental Tenets and Limitations

Reductionism in medical science manifests in several prominent practices: (1) focus on a singular dominant factor in disease, (2) emphasis on corrective homeostasis, (3) inexact unidimensional risk modification, and (4) additive treatments for multiple conditions [1]. While clinically useful, this approach leaves little room for contextual information and neglects complex interplays between system components.

Network-based biology operates on different principles, viewing cellular and organismal constituents as fundamentally interconnected [2]. This paradigm employs mathematical graph theory, reducing a system's elements to nodes (vertices) and their pairwise relationships to edges (links) [3]. Depending on available information, edges can be characterized by signs (positive for activation, negative for inhibition) or weights quantifying confidence levels, strengths, or reaction speeds [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Reductionist and Network-Based Approaches in Biology

| Aspect | Reductionist Approach | Network-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Individual components | Interactions between components |

| System View | Collection of parts | Integrated whole |

| Analytical Method | Isolate and study individually | Study in context of connections |

| Disease Model | Single causative factor | Network perturbations |

| Treatment Strategy | Targeted, singular therapies | Combinatorial, system-wide approaches |

| Mathematical Foundation | Linear causality | Graph theory, nonlinear dynamics |

| Data Requirements | Focused, hypothesis-driven | Comprehensive, high-throughput |

Theoretical Foundations and Emergent Properties

The theoretical underpinnings of network biology draw from General Systems Theory and cybernetics [1]. A fundamental concept is emergence, where novel properties arise from the nonlinear interaction of multiple components that cannot be predicted by studying individual elements in isolation [2]. A classic example is how knowledge of water's molecular structure fails to predict emergent properties like surface tension [2].

Biological networks exhibit specific topological properties that influence their functional behavior. Research has identified small-world and scale-free characteristics in biological networks, along with recurring network motifs that may represent functional units [4]. Understanding these properties enables researchers to identify key regulatory points and predict system behavior under perturbation.

Network Analysis Methodologies in Systems Biology

Network Construction and Data Integration

Constructing biological networks begins with data integration from multiple knowledge bases. The Global Integrative Network (GINv2.0) exemplifies this approach, incorporating human molecular interaction data from ten distinct knowledge bases including KEGG, Reactome, and HumanCyc [5]. A significant challenge in integration is reconciling different definitions of nodes and edges across signaling and metabolic networks.

The meta-pathway structure addresses this challenge by introducing intermediate nodes for each reaction, creating a unified topological structure that accommodates both signaling and metabolic networks [5]. This approach uses a SIF-like format with intermediate nodes (SIFI) to represent biochemical reactions more accurately.

Table 2: Standardized Data Formats for Network Integration

| Format | Description | Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| SIF (Simple Interaction Format) | Semi-structured format specifying source node, edge type, and target nodes | Signaling networks, protein-protein interactions | Simple, works with many analysis tools |

| SIFI (SIF with Intermediate nodes) | Extends SIF with intermediate nodes representing reaction states | Integrating signaling and metabolic networks | Preserves reaction participant information |

| BioPAX | OWL-based format for pathway representation | Comprehensive pathway data exchange | Rich semantic relationships |

| SBML | XML-based format for biochemical models | Dynamic modeling, simulation | Standard for mathematical models |

| GML | Graph Modeling Language | General network visualization | Flexible, supports attributes |

Network Inference from Experimental Data

Graph inference uses gene/protein expression information to predict network structure, identifying which genes/proteins influence others through various regulatory mechanisms [3]. Several computational approaches enable this inference:

- Clustering Algorithms: Group genes with statistically similar expression profiles, enabling "guilt by association" functional predictions [3]. Tools include the Arabidopsis coexpression tool based on microarray data.

- Bayesian Methods: Find directed, acyclic graphs describing causal dependency relationships among system components [3]. These methods establish initial edges heuristically and refine them through iterative search-and-score algorithms.

- Model-Based Methods: Relate the rate of change in gene expression with the levels of other genes using either differential equations (continuous) or Boolean relationships (discrete) [3].

- Constraint-Based Methods: Reconstruct metabolic pathways from stoichiometric information using approaches like flux balance analysis [3].

Experimental Protocol: Network Inference from Time-Course Expression Data

Objective: Infer a regulatory network from gene expression time-series data.

Materials and Reagents:

- RNA extraction kit (e.g., Qiagen RNeasy)

- Microarray or RNA-seq platform

- Computational resources (R/Bioconductor, MATLAB)

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Plan time points to capture dynamic processes (e.g., cell cycle, drug response)

- Data Collection: Extract RNA at each time point and perform gene expression profiling

- Data Preprocessing:

- Normalize expression data using RMA (microarrays) or TPM (RNA-seq)

- Identify differentially expressed genes using Characteristic Direction method [4]

- Network Inference:

- For discrete modeling: Apply Boolean network inference algorithms

- For continuous modeling: Use ordinary differential equations to relate expression changes

- Substitute experimental data into relational equations

- Solve the system of equations for regulatory relationships

- Network Refinement:

- Filter possible solutions using parsimony principles (economy of regulation)

- Validate predictions with experimental perturbations

- Compare with known interaction databases for confirmation

Applications: This protocol was used to infer circadian regulatory pathways in Arabidopsis, predicting novel relationships between cryptochrome and phytochrome genes [3].

Visualization and Analytical Techniques

Network Layout Algorithms and Visualization Tools

Visualizing large-scale molecular interaction networks presents computational challenges. WebInterViewer implements a fast-layout algorithm that uses a multilevel technique: (1) grouping nodes into connected components, then (2) refining the layout based on pivot nodes and local neighborhoods [6]. This approach is significantly faster than naive force-directed layout implementations.

For complex networks with limited readability, abstraction operations are essential:

- Clique collapse: Replace densely interconnected node groups with star-shaped subgraphs

- Composite nodes: Collapse nodes with identical interaction partners into single nodes [6]

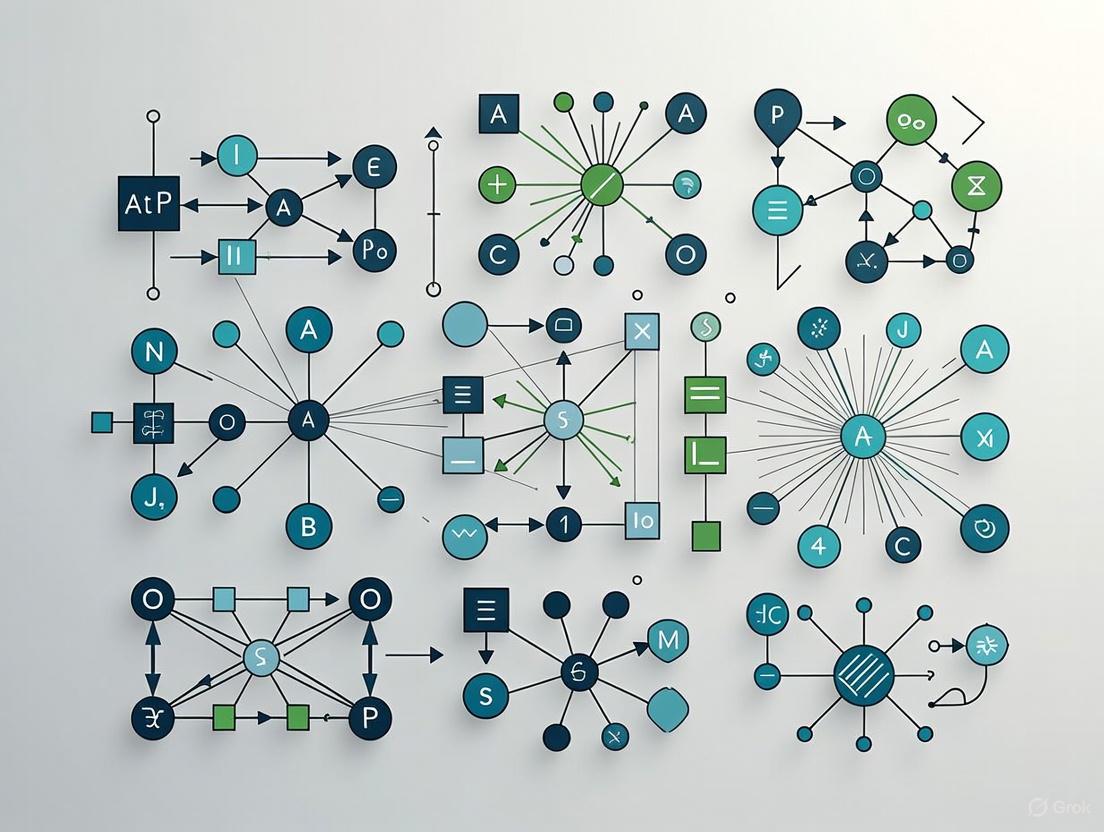

Network Analysis Workflow: Reductionist vs. Network-Based Approaches

Advanced Analytical Methods

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis examines whether defined sets of genes exhibit statistically significant differences between biological states [4]. Advanced implementations include:

- Enrichr: Web-based tool for gene set enrichment analysis [4]

- Principal Angle Enrichment Analysis (PAEA): Improved method for enrichment analysis [4]

- Expression2Kinases: Infers upstream regulators from differentially expressed genes [4]

Clustering methods for network analysis include:

- Principal Component Analysis: Reduces dimensionality while preserving variation

- Self-Organizing Maps: Neural network-based clustering

- Network-Based Clustering: Uses network topology to identify functional modules [4]

Systems Biology Pipeline: From Data to Biological Insights

Successful implementation of network-based biology requires both computational tools and experimental reagents. The following table summarizes key resources for network analysis and validation.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Network Biology

| Category | Resource/Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Bases | KEGG, Reactome, HumanCyc | Source of curated molecular interactions | Pathway analysis, network construction [5] |

| Network Visualization | Cytoscape, WebInterViewer | Graph drawing and visualization | Visual exploration of interaction networks [6] |

| Data Integration | GINv2.0, PathwayCommons | Integrated interaction networks | Comprehensive network analysis [5] |

| Gene Expression Analysis | Enrichr, GEO2Enrichr | Gene set enrichment analysis | Functional interpretation of gene lists [4] |

| Sequencing Analysis | TopHat, Cufflinks, STAR | RNA-seq data processing | Transcriptome network inference [4] |

| Clustering Tools | MATLAB, R/Bioconductor | Multivariate data analysis | Identifying co-expression modules [4] |

| Experimental Validation | CRISPR/Cas9, siRNA | Gene perturbation | Testing network predictions [3] |

| Protein Interaction | Yeast two-hybrid, AP-MS | Protein-protein interaction mapping | Experimental edge validation [3] |

The transition from reductionist to network-based paradigms represents more than just a methodological shift—it constitutes a fundamental change in how we conceptualize biological systems. Reductionism and network approaches are not mutually exclusive but rather complementary ways of studying complex phenomena [2]. The reductionist approach remains invaluable for detailed mechanistic understanding, while network biology provides the contextual framework for understanding system-level behaviors.

The future of biological research lies in effectively integrating these approaches, leveraging their respective strengths to tackle the profound complexity of living systems. As technological advances continue to enhance our ability to collect comprehensive datasets and computational methods become increasingly sophisticated, network-based approaches will play an ever more central role in biological discovery and therapeutic development.

Biological networks provide a foundational framework for understanding the complex interactions that define cellular function and organismal behavior. In systems biology, networks move beyond the study of individual components to model the system as a whole, revealing emergent properties that cannot be understood by examining parts in isolation. The four network types discussed in this guide—Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI), Gene Regulatory (GRN), Metabolic, and Signaling Networks—form the core infrastructure of cellular information processing and control. Analyzing these networks enables researchers to decipher disease mechanisms, identify therapeutic targets, and understand fundamental biological processes through their interconnected architecture.

Table 1: Core Biological Network Types and Their Functions

| Network Type | Primary Components | Biological Function | Representation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) | Proteins (nodes) | Formation of protein complexes and functional modules to execute cellular processes [7] [8] | Undirected graph |

| Gene Regulatory (GRN) | Genes, transcription factors (nodes) | Control of gene expression levels and timing in response to internal/external signals [9] [10] | Directed graph |

| Metabolic | Metabolites, enzymes (nodes) | Conversion of substrates into products for energy production and biomolecule synthesis [11] | Bipartite graph |

| Signaling | Proteins, lipids, second messengers (nodes) | Transmission and processing of extracellular signals to trigger intracellular responses | Directed graph |

Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks

Definition and Biological Significance

Protein-Protein Interaction networks map the physical contacts and functional associations between proteins within a cell. These interactions are fundamental to most biological processes, including cell signaling, immune response, and cellular organization [7]. PPIs form the execution layer of cellular activity, where proteins come together to form complexes that catalyze reactions, form structural elements, and regulate each other's functions. The mapping of PPIs provides critical insights into cellular mechanisms and offers a resource for identifying potential therapeutic targets for various diseases [8].

Advanced Experimental Methodologies

Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) Screening

The Yeast Two-Hybrid system is a high-throughput method for detecting binary protein interactions. This method relies on the modular nature of transcription factors, which typically have separate DNA-binding and activation domains. The protocol involves fusing a "bait" protein to a DNA-binding domain and a "prey" protein to an activation domain. If the bait and prey proteins interact, they reconstitute a functional transcription factor that drives the expression of reporter genes. The key steps include: (1) Constructing bait and prey plasmid libraries; (2) Co-transforming bait and prey constructs into yeast reporter strains; (3) Selecting for interactions on nutrient-deficient media or through colorimetric assays; (4) Sequencing interacting clones to identify partner proteins. While Y2H is powerful for screening large libraries, it may produce false positives due to non-specific interactions and cannot detect interactions in their native cellular context.

Affinity Purification-Mass Spectrometry (AP-MS)

Affinity Purification coupled with Mass Spectrometry identifies proteins that form complexes in vivo. This method provides a more native context for interactions compared to Y2H. The protocol involves: (1) Tagging the bait protein with an epitope (e.g., FLAG, HA, or GST); (2) Expressing the tagged protein in the appropriate cellular system; (3) Lysing cells under mild conditions to preserve complexes; (4) Capturing the bait protein and its interactors using antibodies against the tag; (5) Washing away non-specifically bound proteins; (6) Eluting the protein complex and identifying co-purified proteins using mass spectrometry. AP-MS excels at detecting stable complexes but may miss transient interactions and requires careful controls to distinguish specific from non-specific binders.

Computational Prediction Methods

Recent advances in deep learning have revolutionized PPI prediction, enabling accurate forecasting from protein sequence and structural information.

AttnSeq-PPI: Hybrid Attention Mechanism

AttnSeq-PPI employs a transfer learning-driven hybrid attention framework to enhance prediction accuracy [7]. The methodology uses Prot-T5, a protein-specific large language model, to generate initial sequence embeddings. A two-channel hybrid attention mechanism then combines multi-head self-attention and multi-head cross-attention. The self-attention captures dependencies among amino acid residues within a single protein, while the cross-attention identifies relevant parts of one protein sequence in the context of its potential partner. This architecture is complemented by hybrid pooling (combining max and average pooling) to improve generalization and prevent overfitting. The model frames PPI prediction as a binary classification problem, trained and evaluated using 5-fold cross-validation on benchmark datasets like human intra-species (36,630 interacting pairs from HPRD) and yeast datasets [7].

HI-PPI: Hierarchical Integration with Hyperbolic Geometry

HI-PPI addresses limitations in capturing hierarchical organization within PPI networks by integrating hyperbolic graph convolutional networks with interaction-specific learning [8]. This method processes both protein structure (via contact maps) and sequence data. The hyperbolic GCN layer iteratively updates protein embeddings by aggregating neighborhood information in hyperbolic space, where the distance from the origin naturally reflects hierarchical level. A gated interaction network then extracts pairwise features using Hadamard products of protein embeddings filtered through a dynamic gating mechanism. Evaluated on SHS27K (1,690 proteins, 12,517 PPIs) and SHS148K (5,189 proteins, 44,488 PPIs) datasets, HI-PPI achieved Micro-F1 scores of 0.7746 on SHS27K, outperforming second-best methods by 2.62%-7.09% [8].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of PPI Prediction Methods on Benchmark Datasets

| Method | SHS27K (Micro-F1) | SHS148K (Micro-F1) | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| HI-PPI | 0.7746 | 0.7921 | Hyperbolic GCN with interaction-specific learning [8] |

| MAPE-PPI | 0.7554 | 0.7682 | Heterogeneous GNN for multi-modal data [8] |

| BaPPI | 0.7591 | 0.7615 | Ensemble approach with multiple classifiers [8] |

| AFTGAN | 0.7228 | 0.7413 | Attention-free transformer with GAN [8] |

| PIPR | 0.7043 | 0.7215 | Convolutional neural networks on sequences [8] |

Research Reagent Solutions for PPI Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PPI Network Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Epitope Tags (FLAG, HA, GST) | Enable specific purification of bait protein and its interactors | Affinity Purification-Mass Spectrometry (AP-MS) |

| Yeast Reporter Strains | Host system for detecting binary protein interactions | Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) Screening |

| Protein A/G Beads | Solid support for antibody-based purification | Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) |

| Cross-linkers (Formaldehyde, DSS) | Capture transient interactions by covalent fixation | Cross-linking Mass Spectrometry (CL-MS) |

| Prot-T5 Embedding Model | Generates contextual protein sequence representations | Computational PPI prediction (AttnSeq-PPI) [7] |

Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs)

Definition and Biological Significance

Gene Regulatory Networks represent the directed interactions between transcription factors and their target genes, forming the control system that governs cellular identity, function, and response to stimuli. A GRN is formally represented as a network where nodes represent genes and edges represent regulatory interactions [10]. These networks precisely modulate cellular behavior and functional states, mapping how genes control each other's expression across environmental conditions and developmental stages [9]. In disease research, particularly cancer, GRN analysis reveals key transcription factors like p53 and MYC that drive tumorigenesis, along with their downstream networks, providing insights for personalized therapies [9].

Computational Inference Methodologies

GTAT-GRN: Graph Topology-Aware Attention

GTAT-GRN employs a graph topology-aware attention mechanism with multi-source feature fusion to overcome limitations of traditional GRN inference methods [9]. The methodology integrates three complementary information streams: (1) Temporal features capturing gene expression dynamics across time points (mean, standard deviation, maximum/minimum, skewness, kurtosis, time-series trend); (2) Expression-profile features summarizing baseline expression levels and variation across conditions (baseline expression level, expression stability, expression specificity, expression pattern, expression correlation); (3) Topological features derived from structural properties of the network (degree centrality, in-degree, out-degree, clustering coefficient, betweenness centrality, local efficiency, PageRank score, k-core index). These features are processed through a Graph Topology-Aware Attention Network (GTAT) that combines graph structure information with multi-head attention to capture potential gene regulatory dependencies. The model was validated on DREAM4 and DREAM5 benchmarks, outperforming methods like GENIE3 and GreyNet across AUC and AUPR metrics [9].

GT-GRN: Graph Transformer Framework

GT-GRN enhances GRN inference by integrating multimodal gene embeddings through a transformer architecture [10]. This approach addresses data sparsity, nonlinearity, and complex gene interactions that hinder accurate network reconstruction. The framework combines: (1) Autoencoder-based embeddings that capture high-dimensional gene expression patterns while preserving biological signals; (2) Structural embeddings derived from previously inferred GRNs, encoded via random walks and a BERT-based language model to learn global gene representations; (3) Positional encodings capturing each gene's role within the network topology. These heterogeneous features are fused and processed using a Graph Transformer, enabling joint modeling of both local and global regulatory structures. This multi-network integration strategy minimizes methodological bias by combining outcomes from various inference techniques [10].

Table 4: Feature Types in GRN Inference and Their Biological Functions

| Feature Category | Specific Metrics | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Features | Mean, Standard Deviation, Maximum/Minimum, Skewness, Kurtosis, Time-series Trend | Captures dynamic expression patterns and regulatory relationships [9] |

| Expression-profile Features | Baseline Expression Level, Expression Stability, Expression Specificity, Expression Pattern, Expression Correlation | Characterizes expression stability, context specificity, and potential functional pathways [9] |

| Topological Features | Degree Centrality, In-degree, Out-degree, Clustering Coefficient, Betweenness Centrality, PageRank Score | Elucidates structural roles, information flow control, and hub gene identification [9] |

Metabolic Networks

Definition and Biological Significance

Metabolic networks represent the complete set of metabolic and physical processes that determine the physiological and biochemical properties of a cell. These networks comprise chemical reactions of metabolism, metabolic pathways, and regulatory interactions that guide these reactions. In their visualized form, nodes represent metabolites and enzymes, while edges represent enzymatic reactions [11]. The structure of metabolic networks follows a bow-tie architecture, with diverse inputs converging through universal central metabolites before diverging into diverse outputs. This organization provides robustness and efficiency to cellular metabolism, allowing cells to maintain metabolic homeostasis while adapting to changing nutrient conditions.

Visualization and Analysis Framework

The KEGG global metabolic network provides a standardized framework for metabolic network visualization and analysis [11]. The visualization interface consists of three main components: (1) A central network visualization area where nodes and edges represent metabolites and enzymatic reactions respectively; (2) A toolbar at the top for changing background color, switching view styles, specifying highlighting colors, and downloading network views as images; (3) A pathway table on the left displaying metabolic pathways or modules ranked by their enrichment P-values [11].

In the KEGG layout, certain reactions are represented multiple times at different locations to reduce cluttering—a visualization technique that maintains readability while representing metabolic complexity. Users can interact with the network by double-clicking on edges to view corresponding reaction information (KO and compounds), using mouse scroll to zoom in and out, and clicking on pathway names to highlight KO members (edges) within the network, with edge thicknesses reflecting abundance levels [11]. This interactive framework supports enrichment analysis of shotgun data, allowing researchers to visually explore results within the context of known metabolic pathways.

Signaling Networks

Definition and Biological Significance

Signaling networks integrate and process information from extracellular stimuli to orchestrate appropriate intracellular responses. These networks detect environmental cues through membrane receptors, transduce signals through intracellular signaling cascades, and ultimately regulate cellular processes such as gene expression, metabolism, and cell fate decisions. Unlike linear pathways, signaling networks feature extensive crosstalk, feedback loops, and context-dependent outcomes, enabling cells to make sophisticated decisions based on complex input combinations. Dysregulation of signaling networks underpins many diseases, particularly cancer, autoimmune disorders, and metabolic conditions, making them prime targets for therapeutic intervention.

Analytical Approaches and Challenges

Signaling network analysis employs both experimental and computational methods to map interactions and quantify signal flow. Mass spectrometry-based phosphoproteomics enables large-scale mapping of phosphorylation events, revealing kinase-substrate relationships and signaling dynamics. Fluorescence imaging techniques, including FRET and live-cell tracking, provide spatiotemporal resolution of signaling events. Computationally, Boolean networks and ordinary differential equation models simulate signaling dynamics, while perturbation screens identify critical nodes. The primary challenges in signaling network analysis include context-specificity (signaling differs by cell type and condition), pleiotropy (components function in multiple pathways), and quantitative modeling of post-translational modifications. Recent advances in single-cell analysis and spatial proteomics are addressing these challenges by capturing signaling heterogeneity within cell populations.

Network Analysis in Chemical Safety Applications

CESRN: Chemical Enterprise Safety Risk Network

Network analysis extends beyond molecular biology to industrial safety applications. The Chemical Enterprise Safety Risk Network (CESRN) applies complex network theory to analyze risk factors in chemical production [12]. This approach constructs a network where nodes represent risk factors (human factors, material and machine conditions, management factors, environmental conditions) and accident results, while edges represent causal relationships between factors and results [12]. The adjacency matrix M = (m{ij}){n×n} defines the network structure, where connection strength between nodes i and j is calculated as m{ij} = w{ij}e{ij}, with w{ij} representing the co-occurrence rate and e_{ij} indicating connection status [12].

Quantitative Risk Analysis Methodology

The CESRN framework enables quantitative risk analysis through several computational steps. First, risk factors and accident chains are extracted from safety production accident data using the Cognitive Reliability and Error Analysis Method (CREAM) [12]. The methodology then calculates node risk thresholds and dynamic risk values that consider multiple factors to deduce chemical accident evolution mechanisms. Applied to 481 safety production accident records from 30 hazardous chemical enterprises (2010-2022), this approach identified 24 Human Factors, 17 Material and Machine Conditions, 7 Management Factors, 20 Environmental Conditions, and 19 Accident Factors [12]. The resulting evolution model simulates actual chemical accident development processes, enabling quantitative evaluation of risk factor importance and informing targeted control measures.

Integrated Analysis Across Network Types

Biological systems integrate these network types into a cohesive hierarchy of information flow and control. Signaling networks detect environmental stimuli and transmit information to GRNs, which reprogram cellular function through changes in gene expression. The proteins produced through GRN activity form PPI networks that execute cellular functions, while metabolic networks provide energy and building blocks. This multi-layer organization creates both robustness and vulnerability—perturbations can be buffered through network redundancy, but failure at critical hubs can cause system-wide dysfunction. Multi-omic integration approaches now enable researchers to reconstruct these cross-network interactions, revealing how genetic variation propagates through molecular networks to influence phenotype. This integrated perspective is essential for understanding complex diseases and developing network-based therapeutic strategies that target emergent properties rather than individual components.

In systems biology research, cellular processes are modeled as complex networks where biological components like proteins, genes, and metabolites are represented as nodes, and their interactions are represented as links or edges. Understanding the architecture of these networks through topology and identifying pivotal elements through centrality measures provides a powerful framework for deciphering biological function, robustness, and vulnerability. This approach allows researchers to move beyond studying isolated parts and toward a holistic understanding of system-wide behavior. The strategic analysis of network topology and centrality is thus foundational for identifying critical components, with profound implications for understanding disease mechanisms and accelerating drug development.

Foundational Concepts of Network Topology

Network topology defines the arrangement of elements within a network. In systems biology, this translates to the physical or logical layout of biological interactions [13]. The topology determines how information, such as a biochemical signal, flows through the system and directly influences the network's resilience to failure and its dynamic behavior [14] [15].

There are two primary perspectives for describing network topology:

- Physical Topology: Concerned with the actual physical layout of the network components and connections [14] [13].

- Logical Topology: Focuses on how data flows through the network, regardless of its physical structure [14] [13].

Table 1: Core Types of Network Topologies and Their Biological Applications

| Topology | Key Characteristics | Representation in Biological Systems | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Star | All nodes connected to a central hub [14] [15]. | A transcription factor regulating multiple target genes [14]. | Failure of a leaf node doesn't crash system; easy to manage [14] [15]. | Central hub failure is catastrophic [14] [15]. |

| Ring | Each node connected to two neighbors, forming a closed loop [14] [15]. | Metabolic cycles (e.g., Krebs Cycle) [15]. | Ordered, predictable data flow; no network collisions [14]. | A single node/link failure can disrupt the entire circuit [14] [15]. |

| Bus | All nodes share a single communication backbone [14] [15]. | Signaling along a linear pathway. | Simplicity; requires less cabling [14] [15]. | Backbone failure halts all transmission; security low [14] [15]. |

| Mesh | Every node connected to every other node [14] [15]. | Dense protein-protein interaction networks. | Highly robust and redundant; fault diagnosis is easy [14] [15]. | Expensive/complex to install and maintain [14] [15]. |

| Tree | Hierarchical structure with root and child nodes [14] [15]. | Lineage differentiation trees in developmental biology. | Scalable; easy to manage and expand [14]. | Dependent on root and backbone health; complex setup [14] [15]. |

| Hybrid | Combination of two or more topologies [14] [15]. | A complex, multi-layer signaling network. | Highly flexible; adaptable to specific needs [14]. | Challenging to design; high infrastructure cost [14] [15]. |

Centrality Measures for Identifying Critical Nodes

Centrality measures are quantitative metrics that assign a numerical value, or ranking, to each node in a network based on its structural importance [16]. In the context of systems biology, these measures help pinpoint the most influential or critical components within a complex biological network, such as essential proteins or key regulatory genes [17]. Different measures highlight different aspects of "importance," and the choice of measure depends on the specific biological question.

Table 2: Key Centrality Measures and Their Interpretation in Systems Biology

| Centrality Measure | What It Quantifies | Biological Interpretation | When to Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree Centrality | The number of direct connections a node has [17] [16]. | A highly interactive protein or a gene connected to many others. Indicates local influence or potential "hub" status. | To find nodes with the most immediate local influence or high connectivity [17]. |

| Betweenness Centrality | How often a node lies on the shortest path between other pairs of nodes [17] [16]. | A protein that acts as a critical bridge or bottleneck between different network modules. | To identify brokers, gatekeepers, or potential control points in network flow [17]. |

| Closeness Centrality | The average length of the shortest path from a node to all other nodes [17] [16]. | A metabolite or signaling molecule that can rapidly communicate with many other components in the network. | To find nodes that can spread information or influence most efficiently throughout the network [17]. |

| Eigenvector Centrality | A node's connection influence, based on both its number and quality of connections [16]. | A transcription factor that is not only highly connected but also connected to other highly influential factors. | To find nodes that are connected to other well-connected nodes, capturing "influence by association." |

Methodological Framework for Network Analysis

Experimental Protocol for Network Construction and Analysis

A robust methodology for identifying critical components in a biological system involves a multi-step process that integrates data, network theory, and experimental validation.

Step 1: Data Acquisition and Network Construction

- Objective: To build a comprehensive network model of the biological system.

- Procedure:

- Compile Interaction Data: Gather high-quality data from trusted databases (e.g., protein-protein interactions from STRING, metabolic reactions from KEGG, genetic interactions from BioGRID).

- Define Nodes and Edges: Clearly define the biological entities as nodes (e.g., genes, proteins) and their interactions as edges.

- Construct the Network: Use network analysis software (e.g., Cytoscape) to create a graphical representation of the system. The resulting network can be undirected (e.g., protein interactions) or directed (e.g., signaling pathways).

Step 2: Topological Characterization

- Objective: To understand the global architecture of the constructed network.

- Procedure:

- Identify Topology: Visually and computationally analyze the network to classify its overall topology (e.g., scale-free, modular) and identify local structures like cliques and modules.

- Calculate Basic Metrics: Compute global metrics such as network diameter, average path length, and clustering coefficient to quantify its structural properties.

Step 3: Centrality Calculation

- Objective: To compute multiple centrality measures for every node in the network.

- Procedure:

- Select Centrality Measures: Choose a panel of relevant measures. Degree, Betweenness, and Closeness centrality are a common starting point [17].

- Run Algorithms: Use built-in functions in network analysis tools (e.g., NetworkX in Python, Cytoscape plugins) to calculate the values for each measure.

- Generate Rankings: Create a ranked list of nodes based on each centrality measure.

Step 4: Integrative Analysis and Candidate Prioritization

- Objective: To integrate results from multiple centrality measures and identify high-priority candidates for validation.

- Procedure:

- Compare Rankings: Look for nodes that consistently rank highly across multiple different centrality measures. These are strong candidates for critical system components.

- Generate a Shortlist: Create a focused list of top candidate nodes (e.g., top 5-10%) for downstream experimental validation.

Step 5: Experimental Validation

- Objective: To biologically validate the predicted critical nodes.

- Procedure:

- Perturbation Experiments: Use techniques like RNAi (knockdown), CRISPR-Cas9 (knockout), or small-molecule inhibitors to perturb the candidate nodes in vitro or in vivo.

- Phenotypic Assessment: Measure the functional impact of the perturbation on key system outputs or phenotypes (e.g., cell viability, expression of downstream targets, metabolic flux).

- Network Re-assessment: If possible, re-analyze the network topology after perturbation to observe changes in connectivity and flow, confirming the node's role.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Network Biology

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Network Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Cytoscape | Software Platform | An open-source platform for visualizing complex networks and integrating them with any type of attribute data. Essential for visual exploration and basic computation. |

| STRING Database | Biological Database | A database of known and predicted protein-protein interactions, used as a primary source for constructing protein-centric networks. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 | Molecular Tool | Enables targeted gene knockout for the experimental validation of critical nodes identified through centrality measures by observing resultant phenotypic changes. |

| siRNA/shRNA Libraries | Molecular Tool | Allows for high-throughput knockdown of candidate genes to screen for functional importance and network fragility. |

| NetworkX (Python) | Programming Library | A Python library for the creation, manipulation, and study of the structure, dynamics, and functions of complex networks. Ideal for custom centrality calculations. |

| RNA-Seq | Profiling Technology | Measures gene expression changes following node perturbation, providing data to re-wire the network and understand downstream consequences. |

In systems biology, the complex workings of cellular processes are decoded using two primary conceptual frameworks: biological pathways and interaction networks. A biological pathway is a series of actions among molecules in a cell that leads to a certain product or a change in the cell, such as turning genes on and off, spurring cell movement, or triggering the assembly of new molecules [18]. In contrast, a biological interaction network is a broader collection of interactions (edges) between biological entities (nodes), such as proteins, genes, or metabolites, representing the cumulative functional or physical connectivity within a biological system [19] [20]. These representations are not mutually exclusive; pathways can be viewed as specialized, functionally coherent subsets within larger, more complex interaction networks [21]. Understanding their distinct structures, functions, and appropriate applications is fundamental to network analysis in systems biology research, with direct implications for interpreting genomic data and identifying novel therapeutic strategies [19] [22].

Defining the Core Concepts

Biological Pathways: Directed and Functional Units

Biological pathways are typically characterized by their defined start and end points, and a sequence of actions aimed at accomplishing a specific cellular task [18] [19]. They are often visualized as directed graphs, where the order of interactions conveys a logical flow of information or material.

The principal types of biological pathways include:

- Metabolic pathways involve a series of chemical reactions that either break down a molecule to release energy or utilize energy to build complex molecules. An example is glycolysis, the process by which cells break down glucose into energy molecules [18] [20].

- Signal transduction pathways move a signal from a cell's exterior to its interior. This typically begins with a ligand binding to a cell surface receptor, initiating a cascade of intracellular events, often involving protein modifications, which ultimately leads to a specific cellular response like the production of a particular protein [18].

- Gene-regulatory pathways control the transcription of genes, turning them on and off in response to various signals. This ensures that proteins are produced at the right time and in the right amounts, and is crucial for processes from development to cellular stress responses [18] [20].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Biological Pathway Types

| Pathway Type | Primary Function | Key Components | Representation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic | Breakdown & synthesis of molecules for energy & building blocks | Substrates, Products, Enzymes | Directed network with metabolites as nodes and enzymatic reactions as edges [19] [20]. |

| Signal Transduction | Relay signals from extracellular environment to trigger cellular response | Ligands, Receptors, Kinases, Second Messengers | Often linear or tree-like cascades; information flow is directional [18] [19]. |

| Gene-Regulatory | Control gene expression (transcription) | Transcription Factors, DNA Promoter Elements | Directed network; edges represent activation or inhibition of transcription [18] [20]. |

Biological Interaction Networks: The Global Interactome

Biological interaction networks provide a holistic, system-wide view of molecular relationships. They are generally defined by all known relationships among a set of biological entities within a defined knowledge space, and as such, lack an obvious, predefined boundary tied to a single functional outcome [19]. The nodes and edges in these networks are more homogeneous than in integrated pathway models.

Major classes of biological interaction networks include:

- Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks: Nodes represent proteins, and undirected edges represent physical interactions between them, as identified by high-throughput methods like yeast two-hybrid screening or mass spectrometry [6] [20]. Highly connected proteins (hubs) in PPI networks are often essential for survival [20].

- Gene Co-expression Networks: These are association networks where nodes are genes and edges represent significant correlations in their expression levels across different conditions (e.g., from microarray or RNA-seq data). They are powerful for identifying functional modules of co-regulated genes [20].

- Metabolic Networks: Encompass the complete set of metabolic reactions and pathways in an organism. Nodes are metabolites, and edges are reactions connecting them [20].

- Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs): A directed network where nodes are genes and transcription factors, and edges represent regulatory relationships (e.g., activation or repression of a target gene by a transcription factor) [20].

Table 2: Principal Types of Biological Interaction Networks

| Network Type | Node Entity | Edge Meaning | Network Nature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) | Protein | Physical binding or functional association | Undirected [20] |

| Gene Regulatory (GRN) | Gene / Transcription Factor | Transcriptional regulation (activation/inhibition) | Directed [19] [20] |

| Metabolic | Metabolite | Biochemical reaction | Can be directed or undirected [20] |

| Gene Co-expression | Gene | Significant correlation in expression level | Undirected, weighted [20] |

Figure 1: Conceptual comparison of a linear pathway versus a complex interaction network. The pathway shows a directed, sequential process, while the network displays multiple, interconnected relationships.

Structural and Functional Comparison

The choice between a pathway-centric and a network-centric view has profound implications for data interpretation, analysis, and biological insight.

Key Comparative Attributes

- Linearity vs. Reticulation: Pathways often imply a degree of linearity or a predetermined sequence of events to achieve a specific function. In contrast, networks are inherently reticulate, with many nodes participating in multiple, often overlapping, processes. Most pathways do not start at point A and end at point B, and when multiple biological pathways interact, they form a biological network [18].

- Functional Specificity vs. Holistic Connectivity: A pathway is defined by its functional outcome (e.g., apoptosis, glucose metabolism). A network's boundaries are defined by the current knowledge of all interactions, making it a map of potential functional connections, many of which may be context-dependent [19] [21].

- Context Dependency: Molecular interactions within pathways are often considered in a specific spatial, temporal, or functional context. In a static PPI network, all interactions are presented as potential, lacking this contextual layer, which can lead to a misleading representation of cellular organization [21].

- Dynamic Nature: Both pathways and networks are dynamic, but the tools to represent this differ. Pathway models can more easily incorporate dynamic states (e.g., ligand-bound vs. unbound receptor). Network dynamics are often studied by mapping data like gene expression onto a static interaction scaffold [21].

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Pathways and Networks

| Attribute | Biological Pathway | Interaction Network |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Execute a specific, discrete cellular function | Represent all possible physical/functional connections |

| Structural Nature | More linear or directed acyclic; has input & output | Reticulate, web-like; no single start/end [18] |

| Boundaries | Defined by a specific biological function | Defined by the extent of known interactions; fuzzy [19] |

| Context | Inherently includes spatial/temporal context (e.g., signaling upon stimulus) | Often static; context must be added via other data (e.g., gene expression) [21] |

| Composition | Heterogeneous (proteins, small molecules, DNA) | Typically homogeneous nodes (e.g., all proteins in a PPI) [19] |

| Interpretability | Intuitive, directly linked to biochemistry | Complex, requires computational analysis for interpretation |

The Integrative View: Pathways as Subnetworks and the Rise of Meta-Structures

The distinction between pathways and networks is increasingly blurred in modern systems biology. Pathways are now often understood as functional modules or sub-networks within the larger global interactome [21]. This integrative view is crucial because "biological pathways are far more complicated than once thought. Most pathways do not start at point A and end at point B. In fact, many pathways have no real boundaries, and pathways often work together to accomplish tasks" [18].

Efforts like the Global Integrative Network (GINv2.0) exemplify the push for unification. GINv2.0 integrates molecular interaction data from ten distinct knowledge bases (e.g., KEGG, Reactome, HumanCyc) into a unified topological network. It introduces a "meta-pathway" structure that uses an intermediate node to represent the temporary, conceptual state of molecules in a biochemical reaction. This allows both signaling and metabolic reactions to be stored in a consistent Simple Interaction Format (SIF), facilitating the analysis of crosstalk between different network types [5].

Similarly, a pathway network has been developed where entire pathways themselves become nodes. In this high-level network, edges connect pathways based on the similarity of their functional annotations (e.g., Gene Ontology terms). This representation provides an intuitive functional interpretation of cellular organization, avoiding the noise of molecular-level data and naturally incorporating pleiotropy, as proteins can be represented in multiple pathway-nodes [21].

Methodologies for Network and Pathway Analysis

Experimental Protocols for Construction and Validation

The construction of accurate biological pathways and networks relies on diverse experimental techniques that provide the foundational data.

1. High-Throughput Protein Interaction Mapping:

- Objective: To systematically identify physical interactions between proteins on a proteome-wide scale.

- Protocol (Yeast Two-Hybrid - Y2H):

- The coding sequence of a "bait" protein is fused to a DNA-binding domain.

- The coding sequences of "prey" proteins are fused to a transcription activation domain.

- Both bait and prey constructs are co-expressed in yeast.

- If the bait and prey proteins interact, the DNA-binding and activation domains are brought into proximity, activating reporter genes.

- Positive interactions are identified by yeast growth on selective media or through colorimetric assays [20].

- Validation: Putative interactions from Y2H are often confirmed using co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) followed by western blotting.

2. Generating Gene Co-Expression Networks from RNA-seq Data:

- Objective: To identify groups of genes with correlated expression patterns across diverse conditions, suggesting co-regulation or functional relatedness.

- Protocol (Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis - WGCNA):

- Data Preparation: Obtain RNA-seq count or FPKM/TPM data from multiple samples. Filter lowly expressed genes and normalize the data.

- Correlation Matrix: Calculate pairwise correlation coefficients (e.g., Pearson or Spearman) for all gene pairs across all samples.

- Adjacency Matrix: Transform the correlation matrix into an adjacency matrix, often using a soft-power threshold to emphasize strong correlations.

- Network Construction: Convert the adjacency matrix into a topological overlap matrix (TOM) to measure network interconnectedness.

- Module Detection: Use hierarchical clustering to identify modules (clusters) of highly co-expressed genes.

- Functional Analysis: Annotate modules by enrichment analysis of Gene Ontology terms or known pathways [20].

3. Mapping Perturbations to Pathways/Networks in Disease:

- Objective: To identify pathways or network modules dysregulated in a specific disease (e.g., from GWAS or transcriptomics data).

- Protocol (Gene Set Enrichment Analysis - GSEA):

- Ranking: Rank all genes in the genome based on their correlation with a phenotype (e.g., disease vs. healthy). This could be from differential expression analysis or p-values from GWAS.

- Enrichment Score (ES): For a given pathway gene set S, walk down the ranked list of genes, increasing a running-sum statistic when a gene in S is encountered and decreasing it otherwise. The ES is the maximum deviation from zero encountered.

- Significance Assessment: Permute the phenotype labels to create a null distribution of ES and calculate a nominal p-value.

- Multiple Testing Correction: Adjust p-values for multiple hypothesis testing across all evaluated pathways [19].

Computational Tools for Visualization and Comparison

The analysis of large-scale pathways and networks requires specialized computational tools.

- Cytoscape: An open-source platform for complex network visualization and analysis. Its core functionality can be extended with plugins for pathway data import, network analysis, and layout [6] [5].

- WebInterViewer: A tool designed specifically for visualizing large-scale molecular interaction networks. It uses a fast-layout algorithm that is an order of magnitude faster than classical methods and provides abstraction operations (e.g., collapsing cliques) to reduce complexity for analysis [6].

- CompNet: A GUI-based tool dedicated to the visual comparison of multiple biological interaction networks. It allows visualization of union, intersection, and complement regions of selected networks. Features like "pie-nodes" (where each slice represents a different network) help in identifying key nodes across networks. It also includes metrics like the CompNet Neighbor Similarity Index (CNSI) to capture neighborhood architecture [23].

- PHUNKEE (Pairing subgrapHs Using NetworK Environment Equivalence): An algorithm for identifying similar subgraphs in a pair of biological networks. It is novel in that it includes information about the network context (edges adjoining the subgraph) during comparison, not just the internal edges. This has been shown to improve the identification of functionally similar regions in protein-protein interaction networks [24] [25].

Figure 2: A generalized workflow for integrative network analysis in disease research, combining multiple data types to identify dysregulated functional modules.

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The integration of pathway and network analysis has become a cornerstone of modern, systems-level drug discovery and development, moving beyond the "one-target, one-drug" paradigm.

- Identifying Druggable Targets in Complex Diseases: The failure of the single-target approach for most cancers highlighted the need for a network perspective. Instead of targeting individual genetic mutations, researchers now identify which biological pathways are disrupted by these mutations. Patients can then receive drugs most likely to repair the pathways affected in their particular tumors. For example, the success of Gleevec for chronic myeloid leukemia, which targets a single defective protein, is an exception. For most other cancers, targeting two or three core pathways is a more promising strategy [18].

- Network Pharmacology and Polypharmacology: Network-based approaches allow for the deliberate design of drugs that act on multiple targets simultaneously (polypharmacology). By analyzing network neighborhoods, researchers can identify key nodes (proteins) whose modulation would most effectively restore a dysregulated network to its healthy state. This is particularly relevant in complex diseases like cancer and autoimmune disorders, where robustness is built into the network [22].

- Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP): QSP builds mechanistic mathematical models that incorporate drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics with network and pathway models of disease. These models simulate the effects of a drug on the entire biological system, predicting efficacy and potential side effects, thereby optimizing therapy and guiding clinical trial design [22].

- Drug Repurposing: Network comparisons can reveal unexpected similarities between disease networks. If two distinct diseases share a common dysregulated network module, a drug known to act on that module in one disease may be repurposed for the other [21].

Table 4: The Scientist's Toolkit - Essential Resources for Network and Pathway Analysis

| Resource / Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoscape [6] [5] [23] | Software Platform | Complex network visualization and integration with omics data. | Visualize PPI networks, overlay gene expression data, perform network layout and analysis. |

| KEGG, Reactome [19] [5] | Pathway Database | Curated repositories of known biological pathways. | Pathway enrichment analysis; providing prior knowledge for network construction. |

| BioGRID, STRING [20] | Interaction Database | Databases of known and predicted molecular interactions. | Source of edges for constructing PPI and functional association networks. |

| GINv2.0 [5] | Integrated Network | A comprehensive topological network integrating data from 10 knowledge bases. | Studying crosstalk between signaling and metabolism; systems-level analysis. |

| Gene Ontology (GO) [19] [21] | Vocabulary / Database | Controlled vocabulary for gene product functions and locations. | Functional annotation of network modules and pathways; calculating functional similarity. |

| GSEA Software [19] | Analytical Tool | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. | Determine if a pre-defined set of genes (pathway) shows statistically significant differences between two biological states. |

Biological pathways and interaction networks offer complementary perspectives for deciphering the complexity of living systems. Pathways provide a curated, functionally intuitive view of discrete cellular processes, making them indispensable for formulating testable hypotheses about specific molecular mechanisms. Interaction networks, in contrast, offer a global, systems-level map that reveals the interconnected nature of these processes, capturing emergent properties like robustness and modularity. The most powerful insights arise from integrating these two views—viewing pathways as dynamic, context-dependent functional modules within the larger interactome. As resources like GINv2.0 and sophisticated comparison algorithms like PHUNKEE continue to mature, they empower researchers and drug developers to move from a reductionist view to a holistic one. This integrated approach is crucial for unraveling the complex etiology of human disease and for designing effective, multi-targeted therapeutic strategies that can modulate entire dysregulated networks rather than just single targets.

In the field of systems biology, cellular processes are understood not through the isolated study of individual molecules, but by analyzing the complex networks of interactions between them. This network-centric perspective requires access to high-quality, comprehensive data on protein interactions, genetic associations, and biochemical pathways. Key resources that serve this need include STRING for protein-protein association networks, BioGRID for curated biological interactions, and pathway databases such as Reactome [26]. These repositories provide the foundational data that enable researchers to construct and analyze molecular networks, thereby uncovering the organizational principles and functional dynamics of biological systems. This guide provides a technical overview of these resources, detailing their data sources, content, and application within network analysis workflows.

STRING: Protein-Protein Association Networks

STRING is a database of known and predicted protein-protein interactions. Its interactions include both direct (physical) and indirect (functional) associations, derived from computational prediction, knowledge transfer between organisms, and aggregation from other primary databases [27]. As of 2023, STRING covers 59,309,604 proteins from 12,535 organisms, making it one of the most comprehensive resources for protein association data [27] [28].

- Data Sources: STRING integrates evidence from five main sources: genomic context predictions, high-throughput lab experiments, (conserved) co-expression, automated text mining, and previous knowledge in databases [27].

- Interaction Evidence: Each interaction in STRING is assigned a confidence score, which can be used to filter networks. The database contains over 27 billion total interactions, including 977 million at high confidence (score ≥ 0.700) and 332 million at the highest confidence (score ≥ 0.900) [27].

- Use Cases: STRING is particularly useful for generating initial hypotheses about protein function, analyzing genomic data in a network context, and performing functional enrichment analyses [28].

BioGRID: Biological General Repository for Interaction Datasets

BioGRID is an open-access database dedicated to the manual curation of protein and genetic interactions from multiple species [29]. As of late 2025, BioGRID houses over 2.25 million non-redundant interactions from more than 87,000 publications [30]. All interactions are derived from experimental evidence reported in the primary literature, making BioGRID a gold standard for high-confidence interaction data.

- Data Curation: BioGRID interactions are exclusively derived from expert manual curation, excluding computationally predicted interactions to maintain high confidence [29]. It uses structured vocabularies with 17 different protein interaction evidence codes (e.g., affinity capture-mass spectrometry, co-crystal structure, two-hybrid) and 11 genetic interaction evidence codes (e.g., synthetic lethality, synthetic rescue) [29].

- Expanded Content: In addition to molecular interactions, BioGRID captures protein post-translational modifications (PTMs), interactions with bioactive small molecules and drugs, and gene-phenotype relationships from genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 screens through its BioGRID-ORCS extension [29] [30].

- Themed Curation: To manage the vast human biomedical literature, BioGRID undertakes themed curation projects focused on specific biological processes or diseases, such as the ubiquitin-proteasome system, autophagy, COVID-19, and Alzheimer's Disease [29] [30].

Pathway Databases: Reactome

Pathway databases systematically associate proteins with their functions and link them into networks that describe the biochemical reaction space of an organism [31]. Reactome is one such knowledgebase that provides detailed, manually curated information about biological pathways.

- Data Model: Reactome employs a rigorous data model that classifies physical entities (proteins, small molecules, complexes) and the events (reactions, pathways) they participate in [31]. This allows for the consistent representation of diverse biological processes, including biochemical transformations, binding events, signal transduction, and transport reactions.

- Content and Scope: As of Version 94 (released September 2025), Reactome contains 2,825 human pathways, 16,002 reactions, and 11,630 proteins [32]. All annotations are supported by experimental evidence from the literature.

- Application: Reactome is essential for pathway enrichment analysis, visualizing biological processes, and interpreting genomic datasets in the context of established regulatory and metabolic networks [31] [32].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of STRING, BioGRID, and Reactome

| Feature | STRING | BioGRID | Reactome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Protein-protein associations (functional & physical) | Protein & genetic interactions, PTMs, chemical interactions | Curated biological pathways & reactions |

| Data Origin | Computational prediction, transfer, high-throughput data, text mining | Manual curation from literature (low & high-throughput) | Manual curation from literature |

| Coverage | 59.3M proteins from 12,535 organisms [27] | >2.25M non-redundant interactions from >87k publications [30] | 2,825 human pathways, 16,002 reactions [32] |

| Key Content | Functional associations, integrated scores | Genetic & physical interactions, CRISPR screens, PTMs, drug targets | Pathway maps, reactions, molecular complexes |

| Evidence Quality | Confidence-scored (low to high) | High (experimentally verified) | High (expertly curated) |

Quantitative Comparison of Coverage

A systematic comparison of PPI databases highlights their complementary nature. Research indicates that the combined use of STRING and UniHI retrieves approximately 84% of experimentally verified PPIs, while 94% of total PPIs (experimental and predicted) across databases are retrieved by combining hPRINT, STRING, and IID [33]. Among experimentally verified PPIs found exclusively in individual databases, STRING contributed around 71% of the unique hits [33]. When assessed against a set of literature-curated, experimentally proven PPIs (a "gold standard" set), databases like GPS-Prot, STRING, APID, and HIPPIE each covered approximately 70% of the curated interactions [33]. These findings underscore that while a single database may provide substantial coverage, a combined multi-database approach is often necessary for the most comprehensive analysis.

Table 2: Coverage of Protein-Protein Interaction Databases

| Database Combination | Coverage Type | Approximate Coverage |

|---|---|---|

| STRING + UniHI | Experimentally Verified PPIs | 84% [33] |

| hPRINT + STRING + IID | Total PPIs (Experimental & Predicted) | 94% [33] |

| STRING (Exclusive Contribution) | Experimentally Verified PPIs | 71% [33] |

| GPS-Prot, STRING, APID, HIPPIE | Gold Standard Curated Interactions | ~70% each [33] |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

BioGRID's Manual Curation Protocol

BioGRID's high-quality data stems from its rigorous manual curation pipeline [29]. The general workflow is as follows:

- Literature Collection: Publications are identified through automated PubMed searches and user submissions.

- Curation: Expert curators extract interaction data from the main text, figures, tables, and supplementary information of publications.

- Annotation: Each interaction is assigned to one or more structured evidence codes.

- Physical Interaction Evidence Codes: Affinity Capture-MS, Affinity Capture-Western, Two-hybrid, Co-crystal Structure, FRET, etc.

- Genetic Interaction Evidence Codes: Synthetic Lethality, Synthetic Growth Defect, Synthetic Rescue, Dosage Lethality, etc.

- Quality Control: Curated data undergoes review before integration into the public database.

- Data Integration and Release: The entire database is updated monthly, with versioned public releases [29] [30].

STRING's Data Integration and Scoring

STRING employs a different, complementary approach that combines multiple evidence channels to predict associations and assign confidence scores [27].

- Evidence Channel Processing: Data from genomic context, high-throughput experiments, co-expression, and text mining are processed independently.

- Benchmarking: Each evidence channel is benchmarked against a reference set of trusted functional partnerships (e.g., KEGG pathways).

- Score Calibration: The performance of each channel in the benchmark determines how the raw evidence is converted into probabilistic scores.

- Data Integration: Scores from independent channels are combined into a single, unified confidence score for each protein-protein association.

- Transfer Across Organisms: Functional associations are transferred between organisms based on orthology, significantly expanding coverage for less-studied species [27].

Pathway Annotation in Reactome

Reactome's curation process creates a coherent, computer-readable model of human biology [31].

- Entity Definition: Curators first define the physical entities involved (proteins, chemicals, complexes), including their various modified forms and subcellular locations.

- Reaction Annotation: Events are annotated as reactions with defined inputs, outputs, catalysts (enzymes), and regulators (e.g., activating or inhibitory interactions).

- Pathway Assembly: Individual reactions are organized into larger pathways, which are linked to corresponding Gene Ontology (GO) biological process terms.

- Orthology Inference: The curated human pathways are used to computationally infer pathway annotations for orthologous proteins in other species, leveraging the manually curated human data model.

- Visualization and Analysis: The curated data is made accessible through a pathway browser, analysis tools, and programmatic interfaces [31] [32].

Workflow Visualization and The Scientist's Toolkit

The typical workflow for utilizing these resources in a systems biology project involves data retrieval, network construction, and analysis. The following diagram illustrates this process and the role of each major resource.

Network Analysis Data Integration Workflow

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Resources for Network Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoscape [34] | Software Platform | Network visualization and integration | Visualizing interaction networks, integrating attribute data, performing network analysis via apps. |

| STRING [27] [28] | Online Database | Protein-protein association network retrieval | Initial hypothesis generation, functional enrichment analysis of gene/protein lists. |

| BioGRID [29] [30] | Online Database | Curated protein/genetic interactions and PTMs | Building high-confidence interaction networks from experimentally verified data. |

| Reactome [31] [32] | Online Database | Curated pathway knowledge | Pathway enrichment analysis, visualizing biological processes in a standardized framework. |

| Enrichr [4] | Web-based Tool | Gene set enrichment analysis | Determining functional enrichment of gene lists against hundreds of annotated libraries. |

STRING, BioGRID, and Reactome each provide unique and critical data types for network analysis in systems biology. STRING offers unparalleled coverage and functional association predictions, BioGRID delivers high-confidence, manually curated interactions, and Reactome supplies the context of established biochemical pathways. A robust analytical strategy leverages the strengths of all three repositories. Furthermore, the integration of these data sources with powerful visualization and analysis tools like Cytoscape creates a powerful ecosystem for modeling biological systems. This integrated approach enables researchers to move from static lists of genes or proteins to dynamic network models that offer deeper insights into cellular function, disease mechanisms, and potential therapeutic interventions.

Computational Methods and Applications: Network Inference, Multi-Omics Integration, and Drug Discovery

Complex biological systems are governed by intricate interaction networks among molecules such as genes, proteins, and metabolites. Network inference provides a powerful framework for reconstructing these conditional dependency structures from high-throughput biological data, offering a systems-level view of cellular processes [35] [36]. In computational network biology, graphical models translate observed data into networks where nodes represent biological entities and edges represent statistical relationships, enabling researchers to uncover regulatory pathways, identify key therapeutic targets, and understand disease mechanisms [37] [36]. This technical guide examines three foundational approaches for network inference: Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs) for undirected symmetric relationships, Bayesian Networks for directed acyclic causal structures, and Vector Autoregression (VAR) models for temporal dependencies. Each method offers distinct advantages for specific biological contexts, from static protein interaction networks to dynamic gene regulatory processes, providing computational biologists with essential tools for deciphering the complexity of living systems.

Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs)

Theoretical Foundations

Gaussian Graphical Models (GGMs) represent a class of undirected graphical models where the absence of an edge between two nodes indicates conditional independence between the corresponding random variables given all other variables [38] [39]. Formally, for a random vector (Y = (Y1, \dots, Yp)^T \sim Np(\mu, \Sigma)), the concentration matrix (\Omega = \Sigma^{-1} = (\omega{ij})) encodes the conditional independence structure through the relationship:

[ Yi \perp Yj \mid Y{V\setminus ij} \iff \omega{ij} = 0 ]

where (V\setminus ij) denotes all variables except (Yi) and (Yj) [36]. This equivalence between zero elements in the precision matrix and conditional independence forms the theoretical basis for GGMs, making them particularly valuable for identifying direct associations in biological networks while filtering out indirect correlations [39].

In biological applications, GGMs are regularly employed to reconstruct gene co-expression networks, protein-protein interaction networks, and metabolic networks [36]. The sparsity assumption commonly applied in GGM estimation aligns well with biological reality, where cellular networks are typically characterized by hub nodes and scale-free properties rather than fully connected structures [38] [36].

Bayesian Inference for GGMs

Bayesian approaches to GGM inference provide several advantages, including incorporation of prior knowledge, natural uncertainty quantification for estimated networks, and encouragement of sparsity through appropriate prior specifications [36]. The G-Wishart distribution serves as the conjugate prior for the precision matrix (\Omega) constrained to a graph (G):

[ p(\Omega \mid G, b, D) = I_G(b, D)^{-1} |\Omega|^{(b-2)/2} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2} \text{tr}(\Omega D)\right) ]

where (b > 2) is the degrees of freedom parameter, (D) is a positive definite symmetric matrix, and (IG) is the normalizing constant [38]. This formulation restricts (\Omega) to the space (PG) of positive definite matrices with zero entries corresponding to missing edges in (G) [38] [36].

For multiple related networks across different experimental conditions or disease subtypes, Bayesian methods enable information sharing through hierarchical priors. The Markov random field (MRF) prior encourages common edges across related sample groups:

[

p(G^{(1)}, \ldots, G^{(K)}) \propto \exp\left(\sum{k=1}^K \alpha \|E^{(k)}\| - \sum{k

where (\|E^{(k)}\|) denotes the number of edges in graph (G^{(k)}), and (\eta_{kl}) measures similarity between groups (k) and (l) [38]. This approach is particularly valuable in cancer genomics, where networks may be shared across molecular subtypes but with distinct features specific to each subtype [38] [36].

Experimental Protocol for GGM Inference

Protocol: Bayesian GGM Network Reconstruction from Gene Expression Data

Table: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource | Type | Function | Example Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Matrix | Data Input | (n \times p) matrix with samples as rows, features as columns | RNA-seq, microarray data |

| BDgraph R Package | Software | Bayesian inference for GGMs using birth-death MCMC | [39] |

| ssgraph R Package | Software | Bayesian inference using shotgun stochastic search | [39] |

| BGGM R Package | Software | Bayesian Gaussian Graphical Models | [39] |

| baygel R Package | Software | Bayesian graph estimation using Laplacian priors | [39] |

| G-Wishart Prior | Computational | Prior distribution for precision matrices | [38] |

Data Preprocessing: Normalize gene expression data (e.g., TPM for RNA-seq, RMA for microarrays) and transform to approximate multivariate normality using appropriate transformations (e.g., log, voom).

Graph Space Prior Specification: Define prior distributions over the graph space. Common choices include:

- Erdős-Rényi prior: Each edge included independently with probability (p)

- Scale-free prior: Preferentially attaches new nodes to highly connected nodes

Precision Matrix Prior: Specify G-Wishart prior (WG(b, D)) with hyperparameters:

- (b = 3) (minimal degrees of freedom for proper prior)

- (D = I_p) (identity matrix for neutral prior information)

Posterior Computation: Implement Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling:

- Use birth-death MCMC (BDgraph) for efficient graph space exploration

- Alternatively, use reversible jump MCMC for joint graph and precision matrix sampling