Network Analysis in Disease Pathophysiology: From Systems Biology to Precision Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of network-based approaches for elucidating disease pathophysiology and accelerating drug discovery.

Network Analysis in Disease Pathophysiology: From Systems Biology to Precision Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of network-based approaches for elucidating disease pathophysiology and accelerating drug discovery. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of biological networks, key methodological applications including target identification and drug repurposing, crucial troubleshooting and optimization strategies for robust analysis, and comparative validation of computational techniques. By synthesizing insights from systems biology, quantitative systems pharmacology, and machine learning, this resource serves as a guide for leveraging network medicine to decode complex diseases and develop more effective, targeted therapeutics.

The Network Paradigm: Foundations of Complex Disease Biology

The traditional reductionist approach to human biology, which breaks down systems into their individual components, has proven insufficient for capturing the true nature of disease in all of its dynamic topological complexity [1]. This limitation has become increasingly apparent in addressing challenges such as the declining number of approved drugs and their limited effectiveness in heterogeneous patient populations [1]. Network medicine has emerged as a holistic alternative that conceptualizes disease not as a consequence of single molecular defects but as perturbations within complex molecular interaction networks [1]. This framework offers a natural description of the complex interplay of diverse components within biological systems, providing a powerful approach for interpreting the vast amount of multimodal data being generated to understand healthy and disease states [1].

The integration of biological networks with artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning techniques, represents the frontier of this field, enhancing the speed, predictive precision, and biological insights of computational analyses of large multiomic datasets [1]. This combined approach has demonstrated significant potential for elucidating complex disease mechanisms, identifying drug targets, and guiding increasingly precise therapies [1]. This article provides a comprehensive technical overview of biological network principles, methodologies, and applications within disease pathophysiology research.

Theoretical Foundations of Biological Networks

Basic Network Theory and Terminology

In its most general form, a network is a structure ( N = (V, E) ), where ( V ) is a finite set of nodes or vertices and ( E \subseteq V \otimes V ) is a set of pairs of links or edges [2]. The links can carry a weight, parametrizing interaction strength, and a direction. All information in a network structure is contained in its associated connectivity matrix, encoded through its combinatorial, topological, and geometric properties [2].

In biological contexts, nodes typically represent biological entities (proteins, genes, metabolites, cells, or entire organs), while edges represent their interactions, regulatory relationships, or functional associations [2]. The neurophysiology-network representation map often involves drastic simplifications on both sides. Many studies, particularly at macroscopic scales, utilize a simple network structure—one that has neither self nor multiple edges between the same pair of nodes [2].

From Reductionism to Systems-Level Understanding

Network medicine addresses fundamental challenges rooted in outdated paradigms of disease definition and a lack of fundamental understanding of the complex biological processes underlying health and disease [1]. The reductionist approach to human pathobiology cannot adequately represent disease in all of its dynamic topological complexity [1]. Networks provide a systematic framework for addressing a wide range of biomedical challenges by associating homeostatic biological processes and disease-associated perturbations with connected microdomains (disease modules) within molecular networks [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Research Approaches

| Aspect | Reductionist Approach | Network Medicine Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Unit | Single molecules or pathways | Interactive network modules |

| Disease Concept | Result of single molecular defects | Perturbations in complex networks |

| Analytical Focus | Individual components | System-wide interactions and emergent properties |

| Therapeutic Strategy | Single-target drugs | Multi-target, network-correcting interventions |

| Data Interpretation | Linear causality | Non-linear, system-level dynamics |

Technical Methodologies in Network Analysis

Data Acquisition and Experimental Protocols

Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomic Networks

Data-independent acquisition mass spectrometry (DIA-MS) strategies provide unique advantages for qualitative and quantitative proteome probing of biological samples, allowing constant sensitivity and reproducibility across large sample sets [3]. Unlike data-dependent acquisition (DDA), which sequentially surveys peptide ions and selects a subset for fragmentation based on intensity, DIA systematically collects MS/MS scans for all precursor ions by repeatedly cycling through predefined sequential m/z windows [3].

Experimental Protocol: DIA-MS for Protein Network Mapping

- Sample Preparation: Extract proteins from biological samples of interest (tissue, blood, cells)

- Protein Digestion: Digest proteins into peptides using trypsin or similar proteases

- Liquid Chromatography: Separate peptides by liquid chromatography (LC)

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Utilize Sequential Window Acquisition of all Theoretical Mass Spectra (SWATH) or similar DIA approaches

- Fragment all peptides within predefined m/z windows (typically 25 Da)

- Generate multiplexed fragment ion spectra of all analytes

- Spectral Library Generation:

- Create a preselected peptide library from DDA experiments or spectral libraries

- Include proteotypic peptides proven to be most consistently detected and quantified

- Data Extraction: Use computational tools to extract peptide identifications and quantification from raw spectral data files

The key advantage of DIA is the ability to reproducibly measure large numbers of proteins across multiple samples, ensuring coverage of proteotypic peptides, including those containing PTM amino acid residues, specific splice variants, and peptides carrying non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [3].

Computational Analysis of Post-Translational Modifications

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) are routinely tracked as disease markers and serve as molecular targets for developing target-specific therapies [3]. Computational analysis of modified peptides was pioneered 20 years ago and remains an active research area [3]. PTM-search algorithms fall into three categories: targeted, untargeted, and de novo PTM-search methods [3].

Experimental Protocol: PTM Analysis via DIA-MS

- Library Generation: Build tissue-specific PTM libraries to increase detection and quantification accuracy

- Data Acquisition: Perform DIA-MS with appropriate fragmentation windows

- Data Processing:

- Identify modified peptides based on parent ion mass shifts and retention time changes

- Utilize shared transition ions of unmodified fragment ions to identify novel PTMs

- Validation: Conduct secondary experiments for proper PTM localization confirmation when multiple residues within the peptide could possess the PTM

This approach has proven particularly valuable for analyzing low-abundance modifications such as citrullination, an irreversible deimidation of arginine residues that plays roles in epigenetics, apoptosis, and cancer [3].

Computational Tools and Software Ecosystem

Robust tools for data analysis are required to analyze MS/MS spectra and translate large-scale proteome data into biological knowledge [3]. The table below summarizes key computational software for analyzing DIA data.

Table 2: Computational Tools for Biological Network Analysis

| Software | Input Spectra Format | Type of Quantitation | Application Scope | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skyline | mzML, mzXML, mz5, vendor formats | MS2 | Targeted proteomics analysis | MacLean et al. 2010 |

| Open Swath | mzML, mzXML | MS2 | DIA data processing pipeline | Röst et al. 2014 |

| Spectronaut | HTRMS, WIFF, RAW | MS1, MS2 | Spectral library-based DIA analysis | Reiter et al. 2011 |

| PeakView | WIFF | MS2 | Visualization and validation of DIA data | Sciex |

| SWATHProphet | mzML, mzXML | MS2 | Statistical validation of DIA results | Keller et al. 2016 |

Visualization of Biological Networks

The visual representation of biological networks has become increasingly challenging as underlying graph data grows larger and more complex [4]. Effective visual analysis requires collaboration between biological domain experts, bioinformaticians, and network scientists to create useful visualization tools [4]. Current gaps in biological network visualization practices include an overabundance of tools using schematic or straight-line node-link diagrams despite powerful alternatives, and limited integration of advanced network analysis techniques beyond basic graph descriptive statistics [4].

Network Medicine in Disease Pathophysiology and Therapeutics

Disease Module Identification and Characterization

A major goal of network medicine is identifying subnetworks within larger biological networks that underlie disease phenotypes (disease modules) [1]. AI's increasingly recognized success lies in its incorporation of network-based analysis to overcome limitations of small individual associations often insufficient to uncover novel disease mechanisms [1].

Experimental Protocol: Disease Module Identification

- Network Foundation: Begin with a comprehensive molecular interaction network (typically protein-protein interaction)

- Data Projection: Project omics profiles or genome-wide association study summary statistics onto the network

- Node/Edge Weighting: Assign scores/weights to nodes/edges based on projected data

- Module Detection: Apply computational methods to identify disease modules within these weighted interaction networks [1]

- Validation: Use reductionist approaches to test predicted biological effects of novel genes identified within modules [1]

This approach has successfully mapped network modules for many diseases, providing new insights into the etiology of complex diseases including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cerebrovascular diseases, Alzheimer's disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and autoimmune diseases [1].

Drug Discovery and Repurposing

The disease module framework enables systematic comparison between diseases, often identifying previously unrecognized common pathways or disease drivers [1]. This aids in developing mechanism-based drugs by unveiling novel targets within disease modules and prioritizing approved drugs predicted to interact with those targets as candidates for drug repurposing [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Biological Network Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Trypsin/Lys-C | Protein digestion into peptides | Sample preparation for proteomic analysis |

| TMT/Isobaric Tags | Multiplexed sample labeling for quantitative proteomics | Comparing protein expression across multiple conditions |

| Protein A/G Beads | Immunoprecipitation of protein complexes | Interaction network mapping via co-immunoprecipitation |

| Crosslinking Agents | Stabilization of protein-protein interactions | Capturing transient interactions for network analysis |

| SCIEX TripleTOF/Thermo Orbitrap | High-resolution mass spectrometry platforms | DIA-MS data acquisition for proteomic network mapping |

| Graph Database Systems | Storage and querying of network-structured data | Biological network data management and analysis |

| Single-Cell RNA-seq Kits | Transcriptome profiling at single-cell resolution | Cell-type specific network construction |

| Pathway Analysis Software | Functional interpretation of network modules | Biological context assignment for identified modules |

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The integration of network medicine with artificial intelligence represents a promising path toward precision medicine [1]. However, several important challenges remain. A basic understanding of biological networks requires further refinement to leverage their potential fully in clinical settings [1]. The intracellular organization of the proteome is more dynamic and complex than previously appreciated, and new technologies continue to reveal more details on the structure and function of intercellular communication and tissue organization [1].

A critical challenge involves determining the appropriate level of biological and network detail necessary for meaningful insights [2]. This requires understanding how given network structure can perform specific functions, coupled with better characterization of neurophysiological stylized facts and of the structure-dynamics-function relationship [2]. Future research directions should focus on developing multiscale individual networks that assemble cross-organ or tissue interactions, cell-cell and cell type-specific gene-gene interaction networks, along with other potential biological networks that can be analyzed using graph convolutional network approaches [1].

As the field advances, network-based strategies will play an increasingly important role in integrating multiple layers of biological information into a single holistic view of human pathobiology—the physiome—and whole-person health [1]. This systematic framework promises to transform our approach to complex diseases and their treatments, moving beyond single targets to understand the expected effects of drugs with multiple targets and opening new avenues for combinatorial drug design [1].

The complexity of biological systems and their dysfunctions in disease can be systematically mapped and understood through the lens of biological networks. The discipline of network medicine has emerged as an unbiased, comprehensive framework for interrogating large-scale, multi-omic data to elucidate disease mechanisms and advance therapeutic discovery [5]. This approach moves beyond the reductionist view of single gene or protein dysfunctions to model pathology as a disturbance within complex, interconnected cellular systems. Three core network types—protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks, signal transduction networks, and metabolic networks—serve as foundational pillars for this paradigm, each offering unique insights into cellular organization and function. By analyzing the structure and dynamics of these networks, researchers can identify disease modules, prioritize therapeutic targets, and understand the fundamental principles governing cellular pathophysiology [6].

Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks

Protein-protein interaction networks are mathematical representations of the physical contacts between proteins within a cell. These interactions are fundamental regulators of virtually all cellular processes, including signal transduction, cell cycle regulation, transcriptional control, and the maintenance of cytoskeletal dynamics [7]. In PPI networks, nodes represent individual proteins, and edges connecting them represent physical interactions, which can be direct or indirect, stable or transient, and homodimeric or heterodimeric [7]. The topological modules within PPI networks often correspond to functional units, such as macromolecular complexes (e.g., the ribosome or proteasome) or components of the same biological pathway, making them essential for understanding how cellular functions are organized and executed [6] [8].

Quantitative Features and Functional Insights

Table 1: Key Characteristics of PPI Networks

| Feature | Description | Implication in Disease |

|---|---|---|

| Network Type | "Influence-based" network [9] | Represents functional relationships rather than mass flow. |

| Node Essentiality | Highly connected nodes (hubs) often correlate with lethality upon deletion [9] | Hub proteins can represent critical, non-druggable targets; network neighbors may offer alternative targets. |

| Disease Modules | Genes associated with a specific disease tend to cluster together in topologically close network regions [6] | Allows for the identification of new disease genes and pathways based on network proximity to known genes. |

| Functional Clustering | Topological modules often map to protein complexes or coordinated biological processes [6] | A disease mutation in one protein can implicate an entire complex or pathway in the pathology. |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Elucidating the PPI network requires a combination of experimental and computational techniques.

Experimental Protocols:

- Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) Screening: A classic high-throughput method for detecting binary interactions. A "bait" protein is fused to a DNA-binding domain, and a "prey" library is fused to a transcription activation domain. Interaction reconstitutes a functional transcription factor, activating reporter genes [7].

- Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) followed by Mass Spectrometry: A method for identifying protein complexes. An antibody against a target protein is used to pull it and its binding partners out of a cell lysate. The recovered complexes are then separated and identified using mass spectrometry, revealing endogenous, stable interactions [7].

- Cross-Linking Mass Spectrometry (XL-MS): A rapidly advancing technique that uses chemical cross-linkers to covalently stabilize protein interactions before analysis by mass spectrometry. Modern variations like "click-linking" improve efficiency and interactome coverage, providing structural information on the interaction interfaces [8]. In-situ cross-linking, as demonstrated in studies of the proteasome, preserves complex cellular contexts that can be lost in vitro [8].

Computational Prediction using Deep Learning: Deep learning has revolutionized the prediction of PPIs, overcoming limitations of earlier sequence-similarity-based methods.

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): GNNs are exceptionally suited for PPI prediction as they model the innate graph structure of interaction networks. Variants like Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) aggregate information from a protein's neighboring nodes to generate a representative embedding. Graph Attention Networks (GATs) improve on this by assigning adaptive weights to neighbors, capturing heterogeneous interaction strengths [7].

- Workflow: Protein sequences and/or structural features are encoded as initial node features. The GNN model then performs multiple rounds of message passing between connected nodes to learn complex topological patterns. The final node embeddings are used to predict the likelihood of an interaction, either through a classification layer or by calculating a similarity score [7]. Frameworks like AG-GATCN integrate GATs with temporal convolutional networks for robustness, while RGCNPPIS combines GCN and GraphSAGE to extract both macro-topological and micro-structural motifs [7].

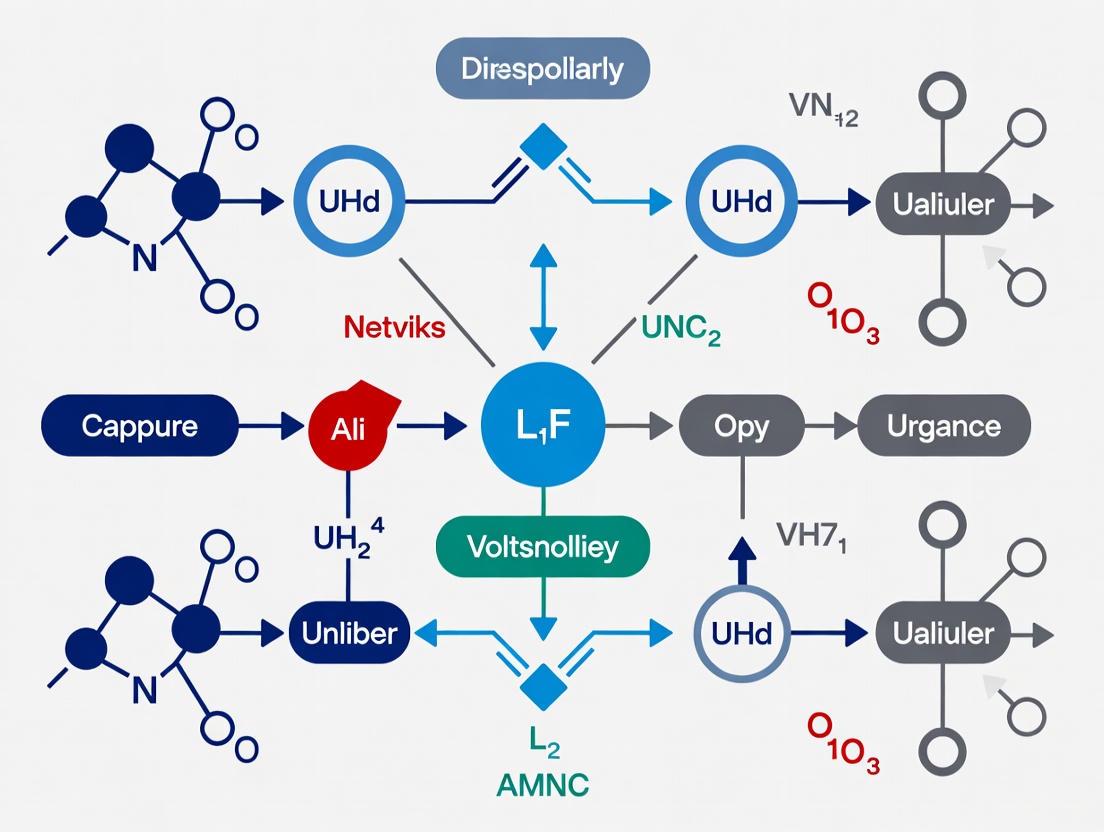

Visualization of a PPI Network Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a typical integrated workflow for constructing and analyzing PPI networks, combining both experimental and computational approaches.

Signal Transduction Networks

Signal transduction networks are computational circuits that enable cells to perceive, process, and respond to environmental cues and changes. These networks are composed of signaling pathways that are highly interconnected, allowing for the integration of multiple signals and the generation of specific, context-dependent cellular responses. In eukaryotes, these networks can be highly complex, comprising 60 or more proteins [10]. The fundamental computational unit found across all signaling networks is the protein phosphorylation/dephosphorylation cycle, also known as the cascade cycle [10]. A quintessential example is the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, a series of consecutive phosphorylation events that amplifies a signal and ultimately regulates critical processes like cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival [10].

Quantitative Features and Functional Insights

Table 2: Key Characteristics of Signal Transduction Networks

| Feature | Description | Implication in Disease |

|---|---|---|

| Core Motif | Phosphorylation/dephosphorylation cascade cycle [10] | Offers a huge variety of control and computational circuits, both analog and digital. |

| Network Type | "Influence-based" network [9] | Represents information flow, governed by kinetic parameters and feedback loops. |

| Dysregulation | Aberrant signaling (e.g., constitutive activation) is a hallmark of cancer and inflammatory diseases. | Targeted therapies (e.g., kinase inhibitors) are designed to re-wire these malfunctioning networks. |

| Cross-talk | Extensive interaction between different signaling pathways. | Explains drug side-effects and compensatory mechanisms, highlighting the need for polypharmacology. |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Experimental Protocols:

- Phospho-Proteomics via Mass Spectrometry: A powerful protocol for mapping signaling network activity. Cells under different conditions (e.g., stimulated vs. unstimulated) are lysed, and proteins are digested into peptides. Phosphopeptides are enriched using titanium dioxide or immobilized metal affinity chromatography and then analyzed by high-resolution mass spectrometry. This allows for the quantitative identification and quantification of thousands of phosphorylation sites, providing a snapshot of signaling network states [8].

- Single-Cell Signaling Network Profiling (e.g., SN-ROP): This method uses mass cytometry (CyTOF) to profile signaling networks at single-cell resolution. Cells are stained with metal-tagged antibodies targeting specific phosphorylated (active) signaling proteins. The single-cell data reveals the dynamic heterogeneity of signaling responses within a population and can identify distinct signaling profiles associated with disease states, such as those driven by redox stress [8].

Computational Modeling:

- Kinetic Modeling: This approach uses ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to model the dynamics of a signaling network. Each reaction (e.g., phosphorylation, dephosphorylation, complex formation) is described by a rate law. By numerically integrating these equations, researchers can simulate the time-dependent behavior of the network, predict the effects of perturbations (e.g., drug inhibitions or mutations), and test hypotheses about network topology and regulation [10].

Visualization of a Canonical MAPK Signaling Pathway

The following diagram depicts a core motif in signal transduction networks: the MAPK cascade.

Metabolic Networks

Metabolic networks represent the complete set of biochemical reactions that occur within a cell to sustain life. These reactions are organized into pathways that convert nutrients into energy, precursor metabolites, and biomass. In contrast to PPI and signaling networks, metabolic networks are flow networks, where mass and energy are conserved at each node (metabolite) [9]. This fundamental difference imposes unique constraints and properties. Nodes represent metabolites, and edges represent biochemical reactions catalyzed by enzymes. The holistic study of these networks, known as flux analysis, aims to understand the flow of reaction metabolites through the network under different physiological and pathological conditions [11].

Quantitative Features and Functional Insights

Table 3: Key Characteristics of Metabolic Networks

| Feature | Description | Implication in Disease |

|---|---|---|

| Network Type | "Flow-based" network with mass/energy conservation [9] | Function is constrained by stoichiometry and thermodynamics. |

| Node Essentiality | Poor correlation between metabolite connectivity (number of reactions) and lethality of disrupting those reactions [9] | Even low-connectivity nodes (metabolites) can be critical if they are unique precursors for essential biomass components. |

| Robustness | Exhibits functional redundancy with alternative pathways. | Diseases like cancer exploit this to rewire metabolism for proliferation (Warburg effect). |

| Compensation-Repression (CR) Model | A systems-level principle where disruption of a core metabolic function is compensated for by genes with the same function while other functions are repressed [11] | Reveals how cells dynamically rewire metabolic flux in response to genetic or environmental perturbations, a mechanism conserved from worms to humans. |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Experimental Protocols:

- Isotope Tracing and Flux Analysis: This is a gold-standard method for measuring metabolic flux. Cells are fed nutrients labeled with stable isotopes (e.g., ¹³C-glucose). As the labeled molecules progress through the metabolic network, the incorporation and position of the isotope in downstream metabolites are tracked using mass spectrometry or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Computational modeling of this labeling data allows for the quantification of intracellular reaction rates (fluxes) [11].

- Systems-Level Flux Inference (e.g., Worm Perturb-Seq): A novel genomics approach to infer metabolic flux at a systems level. As described in Walhout lab's 2025 research, this high-throughput method involves systematically depleting the expression of hundreds of metabolic genes (e.g., via RNAi) in C. elegans and then using RNA sequencing to measure the transcriptomic consequences. The resulting gene expression data is used with computational models to infer the "wiring" of the metabolic network—which reactions are active or carry flux under normal conditions and how the network rewires upon perturbation [11].

Computational Modeling:

- Flux Balance Analysis (FBA): A constraint-based modeling approach used to predict the growth rate or metabolic phenotype of a genome-scale metabolic network. FBA assumes the network is in a steady-state (no metabolite accumulation) and optimizes for a biological objective, such as biomass production. It does not require kinetic parameters and has been successfully used to predict the lethality of gene knockouts and understand the metabolic capabilities of organisms from bacteria to human cells [9].

Visualization of Metabolic Network Analysis and Rewiring

The following diagram illustrates the process of analyzing metabolic network flux and its rewiring in response to perturbations.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Databases for Biological Network Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| STRING | Database | A comprehensive database of known and predicted protein-protein interactions for numerous species, useful for initial PPI network construction [7]. |

| BioGRID | Database | An open-access repository for protein and genetic interactions curated from high-throughput studies and manual literature extraction [7]. |

| Cross-linkers (e.g., DSSO) | Chemical Reagent | Cell-permeable, MS-cleavable cross-linkers used in XL-MS to covalently stabilize transient and weak protein interactions in living cells for structural interactome mapping [8]. |

| Stable Isotopes (e.g., ¹³C-Glucose) | Chemical Reagent | Essential for isotope tracing experiments to track metabolic flux and determine the activity of metabolic pathways in different conditions or disease states [11]. |

| Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) | Vocabulary/Resource | A standardized vocabulary of clinical phenotypes used to link patient symptoms to network-based analyses of underlying molecular mechanisms in network medicine [6]. |

| Worm Perturb-Seq (WPS) | Methodological Platform | A high-throughput genomics method that combines systematic gene depletion with RNA sequencing to infer metabolic network wiring and rewiring principles at a systems level [11]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Computational Tool | A class of deep learning models (e.g., GCN, GAT) specifically designed to learn from graph-structured data, making them ideal for predicting PPIs and analyzing network topology [7]. |

The intricate pathophysiology of human diseases is increasingly being decoded through the lens of network biology. The disease module hypothesis posits that cellular functions are organized into interconnected modules, and diseases arise from the perturbation of these functional units [12]. Genes or proteins associated with a specific disease are not scattered randomly throughout the molecular interaction network but instead cluster in distinct neighborhoods, forming what are known as disease modules [12]. This paradigm represents a fundamental shift from single-target approaches to a systems-level understanding of disease mechanisms.

Biological networks—including protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks, gene co-expression networks, and signaling networks—exhibit inherent modularity, with groups of molecules collaborating to perform specific biological functions [12]. When these tightly connected groups malfunction, they can produce disease phenotypes. The identification and characterization of disease modules provide a powerful framework for understanding disease etiology, identifying comorbid relationships, and discovering new therapeutic targets [12]. Research has demonstrated that disease-associated genes identified through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) often reside in interconnected network communities, validating the functional relatedness of genetically linked disease components [12].

Computational Methodologies for Disease Module Identification

Community Detection Algorithms

Community detection algorithms form the computational backbone of disease module identification. These methods analyze the topological structure of biological networks to identify densely connected groups of nodes (genes/proteins) that may correspond to functional units. Multiple algorithmic approaches have been developed, each with distinct strengths and applications in biological contexts [12].

Table 1: Community Detection Algorithms for Disease Module Identification

| Algorithm | Type | Key Features | Biological Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Louvain | Non-overlapping | Maximizes modularity; fast execution | General protein interaction networks [13] |

| Recursive Louvain (RL) | Non-overlapping | Iteratively breaks large communities into smaller, biologically relevant sizes | Improved disease module identification in heterogeneous networks [13] |

| BIGCLAM | Overlapping | Detects hierarchically nested, densely overlapping communities | Networks with multi-functional proteins [13] |

| CONDOR | Bipartite | Extends modularity maximization to bipartite networks | eQTL networks linking SNPs to gene expression [14] |

| ALPACA | Differential | Optimizes differential modularity to compare community structures between reference and perturbed networks | Differential network analysis in disease states [14] |

The Recursive Louvain (RL) algorithm addresses a critical challenge in biological network analysis: the discrepancy between community sizes generated by standard algorithms and biologically relevant module sizes. By iteratively applying the Louvain method to break large communities into smaller units, RL produces modules that more closely match the scale of known functional pathways [13]. This approach has demonstrated a 50% improvement in identifying disease-relevant modules compared to traditional methods when evaluated across 180 GWAS datasets [12].

For bipartite networks, which connect different types of biological entities (e.g., SNPs and genes), specialized algorithms like CONDOR implement bipartite modularity optimization. This approach has successfully identified communities containing local hub nodes (core SNPs) enriched for disease associations in expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) networks [14].

Differential Network Analysis

Understanding how disease perturbs biological networks requires comparing healthy and diseased states. ALPACA (ALtered Partitions Across Community Architectures) represents a significant advancement in differential network analysis by optimizing a differential modularity metric that captures how community structures differ between reference and perturbed networks [14]. Unlike simple edge subtraction approaches that transfer noise from both networks, ALPACA directly identifies differential modules that highlight specific network regions most altered in disease conditions.

The CRANE method builds upon this approach by providing a statistical framework for assessing the significance of structural differences between networks. This four-phase process includes: (1) estimating reference and perturbed networks, (2) identifying differential features, (3) generating constrained random networks for null distribution estimation, and (4) calculating empirical p-values for the observed differential features [14].

Differential Network Analysis Workflow: This diagram illustrates the ALPACA methodology for identifying differential modules between reference and perturbed (disease) networks through differential modularity optimization.

Experimental Protocol for Disease Module Identification

A comprehensive protocol for identifying and validating disease modules involves multiple stages:

Network Construction: Assemble biological networks from reliable databases. The DREAM challenge on Disease Module Identification provided six heterogeneous networks: PPI-1 (STRING database), PPI-2 (InWeb), signaling networks, co-expression networks (Gene Expression Omnibus), cancer networks (Project Achilles), and homology networks (CLIME algorithm) [12].

Pre-processing: Implement quality control measures to address biological network noise. This includes removing interactions with low confidence scores and filtering nodes with questionable annotations [12].

Community Detection: Apply appropriate algorithms based on network characteristics:

- For non-overlapping communities in standard networks: Recursive Louvain

- For overlapping communities: BIGCLAM

- For bipartite networks: CONDOR

- For differential analysis: ALPACA

Disease Enrichment Analysis: Evaluate identified modules against known disease-gene associations from databases such as DisGeNET and ClinVar using hypergeometric tests with Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction [13]. Mutations affecting genes within identified communities show significantly greater pathogenicity (p ≪ 0.01) and greater impact on protein fitness [13].

Validation: Replicate findings in independent datasets. For example, in Alzheimer's disease research, modules identified in the ROSMAP cohort were validated in an independent single-nucleus dataset [15].

Applications in Disease Research and Drug Development

Case Study: Alzheimer's Disease Module Discovery

A recent study applied systems biology methods to single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) data from dorsolateral prefrontal cortex tissues of 424 participants from the Religious Orders Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project (ROSMAP) [15]. Researchers identified cell-type-specific co-expression modules associated with Alzheimer's disease traits, including amyloid-β deposition, tangle density, and cognitive decline [15].

Notably, astrocytic module 19 (ast_M19) emerged as a key network associated with cognitive decline through a subpopulation of stress-response cells [15]. Using a Bayesian network framework, the researchers modeled directional relationships between modules and AD progression, providing insights into the temporal sequence of molecular events in disease pathogenesis [15]. This approach demonstrated how cell-type-specific network analysis can uncover novel therapeutic targets within biologically relevant disease modules.

Advancing Drug Development through Human Disease Models

The high failure rates of drug development—reaching 95% in 2021—highlight the limitations of animal models in predicting human therapeutic responses [16]. Bioengineered human disease models including organoids, bioengineered tissue models, and organs-on-chips (OoCs) now enable more physiologically relevant testing of therapeutic interventions targeting disease modules [16].

Table 2: Human Disease Models for Validating Disease Module Discoveries

| Model Type | Key Features | Applications in Disease Module Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Organoids | Self-organizing 3D structures from stem cells; emulate human organ development | Study cell-cell interactions within disease modules; high-throughput drug screening [16] |

| Bioengineered Tissue Models | Cells seeded on scaffolds; air-liquid interface cultivation | Model tissue-specific transport and junction properties relevant to module function [16] |

| Organs-on-Chips (OoCs) | Microfluidic platforms with perfused, interconnected tissues | Study multi-tissue crosstalk within disease module pathways; real-time monitoring [16] |

These human model systems address critical limitations of animal models, including species-specific differences in receptor expression, immune responses, and pathomechanisms [16]. For target validation within disease modules, OoCs currently constitute the most promising approach to emulate human disease pathophysiology in vitro [16].

Disease Module Research Pipeline: This workflow illustrates the integration of computational disease module identification with experimental validation using human disease models and subsequent therapeutic applications.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Disease Module Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function in Disease Module Research |

|---|---|---|

| Network Databases | STRING, InWeb, DisGeNET, ClinVar | Provide curated molecular interactions and disease-gene associations for network construction [13] [12] |

| Community Detection Software | NetZoo package (CONDOR, ALPACA, CRANE) | Implement specialized algorithms for biological network community detection [14] |

| Human Disease Models | Organoid protocols, OoC platforms | Enable experimental validation of predicted disease modules in human-relevant systems [16] |

| Validation Databases | GWAS catalogs, ROSMAP transcriptomic data | Provide benchmark datasets for testing disease module predictions [15] [12] |

The field of disease module research is advancing toward more sophisticated multi-scale network models that integrate molecular, cellular, and physiological data. The integration of single-cell omics technologies with network medicine approaches is enabling the identification of cell-type-specific disease modules, as demonstrated in Alzheimer's research [15]. Future methodologies must account for the overlapping nature of biological communities, as genes frequently participate in multiple functional processes and disease mechanisms [12].

Challenges remain in standardizing disease model validation, establishing regulatory guidelines, and scaling production for high-throughput applications [16]. However, the systematic identification of disease modules provides a powerful framework for understanding pathophysiological mechanisms, discovering novel therapeutic targets, and ultimately developing more effective treatments for complex diseases. As these approaches mature, they promise to bridge the translational gap between basic research and clinical applications by focusing therapeutic development on biologically coherent disease modules rather than individual molecular targets.

The human interactome represents a comprehensive map of physical and functional interactions between proteins in a cell, forming a complex network that underpins all cellular functions [17]. Protein-protein interaction networks (PPINs) are constructed from binary interactions, representing direct physical contacts between two proteins, and serve as a primary resource for understanding cellular organization [17]. The intricate web of relationships within the interactome controls crucial biological processes ranging from molecular transport to signal transduction, and its disruption is intimately linked to disease pathogenesis [17]. The discipline of Network Medicine has emerged to approach human pathologies from this systemic viewpoint, mining molecular networks to extract disease-related information from complex topological patterns [6].

Investigating perturbed processes using biological networks has been instrumental in uncovering mechanisms that underlie complex disease phenotypes [18]. Rapid advances in omics technologies have prompted the generation of high-throughput datasets, enabling large-scale, network-based analyses that facilitate the discovery of disease modules and candidate mechanisms [18]. The knowledge generated from these computational efforts benefits biomedical research significantly, particularly in drug development and precision medicine applications [18]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of interactome mapping methodologies, analytical frameworks, and their applications in elucidating disease pathophysiology.

Methodologies for Interactome Mapping

Experimental Approaches for Protein Interaction Detection

Multiple high-throughput experimental techniques have been developed to map the human interactome systematically. Yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assays and affinity purification coupled with mass spectrometry (AP-MS) have been essential in mapping the human interactome [17]. These approaches detect pairwise interactions through complementary mechanisms: Y2H identifies binary interactions through reconstitution of transcription factors, while AP-MS detects protein complexes through co-purification.

Cross-linking and mass spectrometry (XL-MS) enable detection of both intra- and inter-molecular protein interactions in organelles, cells, tissues and organs [19]. Quantitative XL-MS extends this capability to detect interactome changes in cells due to environmental, phenotypic, pharmacological, or genetic perturbations [19]. This approach provides distance constraints on protein residues through chemical crosslinkers, helping elucidate the structures of proteins and protein complexes. Quantitative crosslink data can be derived from samples isotopically labeled light or heavy, using technologies such as SILAC or at the level of the crosslinker, enabling precise measurement of interaction dynamics [19].

Several curated databases provide comprehensive protein-protein interaction data, each with distinct strengths and curation approaches:

Table 1: Major Protein-Protein Interaction Databases

| Database | Interaction Count | Key Features | Update Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| BioGRID | 2,251,953 non-redundant interactions from 87,393 publications [20] | Includes protein, chemical, and genetic interactions; themed curation projects focused on specific diseases | Monthly [20] |

| STRING | >20 billion interactions across 59.3 million proteins [21] | Functional enrichment analysis; pathway visualization; 12535 organisms | Continuously updated |

| Human Protein Atlas Interaction Resource | 22,979 consensus interactions predicted by AlphaFold 3 [22] | Integrated data from four interaction databases for 15,216 genes; metabolic pathways for 2,882 genes | Regularly updated |

| XLinkDB | Custom dataset upload and analysis [19] | Specialized in cross-linking mass spectrometry data; 3D visualization capabilities | Continuously updated |

Computational and Structural Integration

Computational frameworks have become increasingly important for predicting and characterizing interactions. The AlphaFold system has revolutionized interactome mapping by providing predicted three-dimensional structures for protein-protein interactions [22]. The Human Protein Atlas incorporates AlphaFold 3 predictions for 22,979 consensus interactions, enabling structural insights at unprecedented scale [22].

For higher-order interactions, novel computational approaches are emerging. A recent framework classifies protein triplets in the human protein interaction network (hPIN) as cooperative or competitive using hyperbolic space embedding and machine learning [17]. This approach uses topological, geometric, and biological features to distinguish whether multiple binding partners can bind simultaneously (cooperative) or compete for binding sites (competitive), achieving high prediction accuracy (AUC = 0.88) [17].

Network Analysis and Disease Module Discovery

Fundamental Network Concepts in Biology

Biological networks represent relationships between molecular entities, with nodes typically representing proteins, genes, or metabolites, and edges representing interactions or other relationships [6]. The key concept in most network medicine approaches is that of the "disease-related module" - a set of network nodes that are enriched in internal connections compared to external connections [6]. Topologically, these modules represent sub-networks with some degree of independence from the rest of the network, and in biological contexts, they often correspond to functional modules comprising molecular entities involved in the same biological process [6].

In protein interaction networks, topological modules have been shown to correspond to interacting proteins involved in the same biological process, forming molecular complexes, or working together in signaling pathways [6]. This relationship between topological modules and functional modules forms the basis of most approaches in Network Medicine, allowing researchers to connect diseases with their underlying molecular mechanisms [6].

Network Propagation and Gene Prioritization

Network propagation or network diffusion approaches detect topological modules enriched in seed genes known to be associated with a disease according to various pieces of evidence [6]. These methodologies are crucial for:

- Filtering candidate genes: Discarding or adding new genes based on their belonging/closeness to disease modules

- Gene prioritization: Using network information to filter large sets of variants from genome-wide association studies (GWAS)

- Predicting new disease associations: Identifying genes potentially associated with diseases that could be more "druggable"

- Functional insight: Relating diseases to biological functions due to the relationship between topological modules and functional modules

Visualization and Analytical Tools

Network visualization presents significant challenges due to the complexity and scale of biological interaction data. The classic visualization pipeline involves transforming raw data into data tables, then creating visual structures and views based on task-driven user interaction [4]. Cytoscape serves as a primary tool for network visualization and analysis, enabling researchers to explore complex relationships and processes in weighted and directed graphs [23].

XLinkDB 3.0 provides specialized informatics tools for storing and visualizing protein interaction topology data, including three-dimensional visualization of quantitative interactome datasets [19]. This platform enables viewing crosslink data in table format with heatmap visualization or as PPI networks in Cytoscape, facilitating efficient data exploration [19].

Diagram 1: Interactome Analysis Workflow. This workflow illustrates the pipeline from data acquisition to biological interpretation, incorporating both experimental and computational data sources.

Network Medicine Applications in Disease Research

Disease Network Construction and Analysis

Network-based approaches have been successfully applied to model disease regulation and progression. Diagnosis Progression Networks (DPNs) constructed from large-scale claims data reveal temporal relationships between diseases, providing directionality, strength, and progression time estimates for disease transitions [23]. These networks incorporate critical risk factors such as age, gender, and prior diagnoses, which are often overlooked in genetic-based networks [23].

DPNs exhibit characteristic topological properties, typically forming scale-free networks where a few diseases share numerous links while most diseases show limited associations [23]. The combined degree distribution follows a power law (γ=2.65), indicating that a small number of hub diseases such as chronic kidney disease and heart failure are highly connected to other diseases [23]. Analysis of in-degree and out-degree distributions reveals strong positive correlation (adjusted r=0.799), showing that diagnoses leading to many other diagnoses tend to have many incoming edges [23].

Phenotype-Centered Network Approaches

The Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) provides a standardized vocabulary for describing human phenotypes in a hierarchical structure, enabling computational studies of phenotype-network relationships [6]. Phenotype-centered network approaches are particularly valuable for:

- Patient stratification: Using clinical phenotypes to subgroup patients for personalized interventions

- Disease clustering: Grouping diseases according to phenotypic similarities despite different genetic causes

- Gene prioritization: Identifying candidate genes based on phenotypic profiles rather than predetermined disease categories

It has been established that diseases with similar phenotypes are often caused by functionally related genes, with the extreme case being genetically heterogeneous diseases caused by genes involved in the same biological unit [6]. This observation provides the foundation for using phenotypic similarity to infer functional relationships between genes and proteins.

Quantitative Interactome Mapping for Dynamic Processes

Quantitative XL-MS enables detection of interactome changes in cells due to environmental, phenotypic, pharmacological, or genetic perturbations [19]. This approach combines crosslinking data with protein abundance measurements to delineate conformational and interaction changes due to posttranslational modifications or protein interactor-induced allosteric changes, rather than simply changes in protein abundance [19].

The unique capability to visualize interactome changes in samples treated with increasing concentrations of drugs, or samples crosslinked longitudinally during environmental perturbation, can reveal functional conformational and protein interaction changes not evident in other large-scale data [19]. These dynamic interactome measurements provide unprecedented insight into biological function during perturbation.

Experimental Protocols for Interactome Mapping

Cross-Linking Mass Spectrometry (XL-MS) Protocol

Cross-linking coupled with mass spectrometry has emerged as a powerful technique for detecting protein interactions and determining spatial constraints. The following protocol outlines the key steps for quantitative XL-MS analysis:

Sample Preparation:

- Grow cells in isotopically labeled media (SILAC) for quantitative comparisons

- Cross-link proteins using cleavable cross-linkers (e.g., DSSO) in situ

- Quench cross-linking reaction

- Lyse cells and extract proteins

- Digest proteins with trypsin

- Enrich for cross-linked peptides via affinity purification

Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Analyze peptides by LC-MS/MS using data-dependent acquisition

- Use stepped collision energy to fragment peptides

- Identify cross-linked peptides using specialized search algorithms (e.g., XLinkX, MaxLynx)

- Quantify light and heavy cross-linked peptides according to peak areas of parent ions in MS1

- Calculate ratio of abundance in experimental versus reference condition

Data Processing and Validation:

- Filter identifications using false discovery rate threshold (typically <1%)

- Map cross-links to protein structures and models

- Validate interactions using orthogonal methods when possible

Network Propagation Analysis Protocol

Network propagation approaches are valuable for identifying disease-relevant modules within larger interaction networks:

Input Data Preparation:

- Compile seed genes with known disease associations from genomic studies

- Select appropriate protein-protein interaction network (e.g., from BioGRID, STRING)

- Annotate network nodes with additional attributes (expression, mutations)

Network Analysis:

- Implement random walk with restart algorithm to propagate information from seed genes

- Adjust propagation parameters (restart probability) based on network density

- Calculate significance of node scores using permutation testing

- Extract module boundaries using community detection algorithms

- Validate modules using functional enrichment analysis

Result Interpretation:

- Prioritize candidate genes based on network proximity to known disease genes

- Annotate modules with functional information (GO terms, pathways)

- Integrate with additional omics data for validation

- Generate hypotheses for experimental follow-up

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Interactome Mapping

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction Databases | BioGRID [20] | Repository of protein, chemical, and genetic interactions | 2.25M+ curated interactions; monthly updates |

| STRING [21] | Functional protein association networks | >20B interactions; pathway enrichment analysis | |

| Human Protein Atlas [22] | Protein-protein interaction networks with structural data | AlphaFold 3 predictions; subcellular localization | |

| Experimental Tools | Cross-linking Mass Spectrometry [19] | Detection of protein interactions and spatial constraints | In situ interaction mapping; quantitative applications |

| CRISPR Screening (BioGRID ORCS) [20] | Functional genomics screening | Curated CRISPR screens; 2,217 screens from 418 publications | |

| Computational Tools | XLinkDB [19] | Cross-linked peptide database and analysis | 3D visualization; quantitative interactome analysis |

| Cytoscape [23] | Network visualization and analysis | Plugin architecture; versatile visualization options | |

| AlphaFold 3 [22] | Protein structure and interaction prediction | High-accuracy structure prediction for complexes | |

| Analytical Frameworks | Hyperbolic Embedding [17] | Network geometry analysis | Reveals functional organization; predicts cooperative interactions |

| Random Forest Classification [17] | Machine learning for interaction prediction | Distinguishes cooperative vs. competitive triplets (AUC=0.88) |

Diagram 2: Cooperative vs. Competitive Interactions in Protein Triplets. This diagram illustrates how proteins with distinct binding interfaces can form cooperative complexes, while those with overlapping interfaces compete for binding.

Interactome mapping has evolved from simple binary interaction catalogs to sophisticated, quantitative networks that capture the dynamic nature of cellular organization. The integration of structural data through AlphaFold predictions, quantitative interaction measurements through XL-MS, and advanced computational frameworks has transformed our ability to model cellular processes in health and disease [22] [19] [17].

Future directions in interactome research include more integrative and dynamic network approaches to model disease development and progression [18]. The need for advanced visualization tools that can represent complex, multi-dimensional interactome data remains a challenge, with current tools predominantly using schematic node-link diagrams despite the availability of powerful alternatives [4]. Additionally, there is a recognized need for visualization tools that integrate more advanced network analysis techniques beyond basic graph descriptive statistics [4].

The application of network-based approaches to precision medicine continues to expand, with phenotype-centered strategies offering particular promise for patient stratification and personalized intervention design [6]. As interactome mapping technologies become more sophisticated and accessible, they will increasingly inform drug discovery pipelines and therapeutic development strategies, ultimately enabling a more comprehensive understanding of disease pathophysiology through the lens of network biology.

The study of complex networks has fundamentally transformed our understanding of disease pathophysiology by providing a framework to analyze biological systems as interconnected webs of molecular interactions. Living systems are characterized by an immense number of components immersed in intricate networks of interactions, making them prototypical examples of complex systems whose properties cannot be fully understood through reductionist approaches alone [6]. Network medicine has emerged as the discipline that approaches human pathologies from this systemic viewpoint, recognizing that many pathologies cannot be reduced to a failure in a single gene or a small number of genes in a simple, additive way [6]. These complex diseases are better reflected at the "network level," allowing the integration of information on the relationships between genes, drugs, environmental factors, and more.

The robustness and fragility of biological networks play a crucial role in determining disease susceptibility and progression. Research on network percolation models has demonstrated that networks with highly skewed degree distributions, such as power-law networks, exhibit dramatically different resilience properties compared to random networks with Poisson degree distributions [24]. This structural understanding provides critical insights into why certain biological systems can withstand some perturbations while being exceptionally vulnerable to others, with direct implications for understanding disease mechanisms and developing therapeutic interventions.

Theoretical Foundations of Network Robustness and Fragility

Fundamental Concepts in Network Resilience

Network robustness refers to a system's ability to maintain its structural integrity and functional capacity when subjected to random failures or targeted attacks, while network fragility describes its vulnerability to specific perturbations. The seminal work by Callaway et al. extended percolation theory to graphs with completely general degree distributions, providing exact solutions for cases including site percolation, bond percolation, and models where occupation probabilities depend on vertex degree [24]. This theoretical framework is essential for understanding real-world networks, which often possess power-law or other highly skewed degree distributions quite unlike the Poisson distributions typically studied in classical random graph models [24].

The percolation threshold represents a critical point where a network transitions from connected to fragmented states. For biological networks, this threshold has direct analogs in disease propagation and resilience to functional disruption. The duality observed in epidemic models on complex networks reveals that depending on network properties, simulations can yield dramatically different outcomes even when mean-field theories predict identical epidemic thresholds [25]. This duality manifests particularly in scale-free networks, where for power-law degree distributions with exponent γ > 3, standard SIS models exhibit vanishing thresholds while modified models show finite thresholds, indicating fundamentally different activation mechanisms [25].

Epidemic Models and Network Structure

The Susceptible-Infected-Susceptible (SIS) epidemic model serves as a fundamental framework for studying disease spread on networks. Recent analyses of altered SIS dynamics that preserve the central properties of spontaneous healing and infection capacity increasing unlimitedly with vertex degree reveal a dual scenario [25]. In uncorrelated synthetic networks with power-law degree distributions where γ < 5/2, SIS dynamics are robust across different models, while for γ > 5/2, thresholds align better with heterogeneous rather than quenched mean-field theory [25].

Table 1: Epidemic Threshold Behavior in Power-Law Networks with Different Exponent Ranges

| Power-Law Exponent Range | Standard SIS Model | Modified SIS Models | Activation Trigger |

|---|---|---|---|

| γ < 2.5 | Robust across models | Robust across models | Innermost k-core component |

| 2.5 < γ < 3 | Vanishing threshold | Finite threshold | Innermost k-core component |

| γ > 3 | Vanishing threshold | Finite threshold | Collective network activation |

This duality is elucidated through analysis of epidemic lifespan on star graphs and network core structures. The activation of modified SIS models is triggered in the innermost component of the network given by a k-core decomposition for γ < 3, while it happens only for γ < 5/2 in the standard model [25]. For γ > 3, activation in the modified dynamics involves essentially the whole network collectively, while it is triggered by hubs in standard SIS dynamics [25]. This fundamental understanding of how disease dynamics depend on network topology provides critical insights for predicting susceptibility and designing interventions.

Network Approaches to Human Disease Pathophysiology

Disease Modules in Molecular Networks

A cornerstone of network medicine is the concept of the "disease-related module" – a topological cluster within molecular networks where disease-associated genes/proteins tend to congregate [6]. These modules represent sub-networks with enriched internal connections compared to external connections, and in biological contexts, they correspond to functional units comprising molecularly related entities [6]. In protein interaction networks, topological modules typically involve proteins participating in the same biological process, forming macromolecular complexes, or working together in signaling pathways [6]. The relationship between topological modules and disease-related modules forms the foundation of most network medicine approaches, enabling researchers to connect diseases with their underlying molecular mechanisms.

Network propagation or network diffusion methodologies detect these disease modules from initial sets of "seed" genes known to be associated with a particular disease [6]. These approaches leverage the topological structure of molecular networks to identify modules enriched in these seed genes, allowing for: (1) filtering and prioritizing candidate genes based on their proximity to established disease modules; (2) predicting novel disease-associated genes that might be more druggable; (3) linking diseases to specific biological functions and pathways; and (4) understanding molecular mechanisms through the network context of disease genes [6]. This methodology has proven particularly valuable for complex diseases like cancer, where the transition from health to disease is characterized by the concentration of mutated genes in specific network modules rather than a general increase in mutation count [6].

Phenotype-Centered Network Analysis

Traditional disease classifications are increasingly being supplemented by phenotype-centered approaches that leverage the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) – a standardized vocabulary describing human phenotypes in a hierarchical structure [6]. This approach recognizes that diseases characterized by similar HPO term profiles often cluster together and are frequently caused by functionally related genes [6]. The extreme case involves genetically heterogeneous diseases caused by genes participating in the same biological unit, such as macromolecular complexes, pathways, or organelles.

Table 2: Key Resources for Phenotype-Centered Network Analysis

| Resource Type | Specific Resource | Application in Network Medicine |

|---|---|---|

| Phenotype Ontology | Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) | Standardized vocabulary for clinical signs and symptoms |

| Molecular Networks | Protein-Protein Interaction Networks | Identifying disease modules and functional complexes |

| Methodology | Network Propagation | Detecting disease modules from seed genes |

| Data Integration | GWAS Integration | Prioritizing variants from association studies |

Phenotype-centered network approaches are particularly valuable for personalized medicine applications, as they facilitate patient stratification based on phenotypic manifestations and enable the design of targeted interventions. This methodology acknowledges that the complex human pathological landscape cannot always be neatly partitioned into discrete "diseases," as the same disease can manifest differently across individuals, while different diseases can share common phenotypes [6].

Methodological Framework for Network Analysis in Disease Research

Experimental Protocols for Network Medicine

Network Propagation Methodology

Network propagation techniques represent a cornerstone approach for identifying disease modules from seed genes. The standard protocol involves multiple stages: First, seed gene identification compiles an initial set of genes associated with a disease through genomic studies (GWAS, sequencing), transcriptomic analyses, or literature mining. Second, network construction builds or selects appropriate molecular networks (protein-protein interaction, genetic interaction, or co-expression networks). Third, propagation algorithm application uses random walk with restart, diffusion kernel, or other propagation methods to identify network regions enriched around seed genes. Fourth, module extraction applies clustering algorithms to define the boundaries of potential disease modules. Finally, functional annotation links identified modules to biological processes, pathways, and cellular components to derive mechanistic insights [6].

The mathematical foundation typically involves representing the molecular network as a graph G(V, E) with nodes V representing genes/proteins and edges E representing interactions. The propagation process can be modeled as:

F(t+1) = αF(0) + (1-α)WF(t)

Where F(t) represents the influence vector at step t, F(0) is the initial vector based on seed genes, W is the normalized adjacency matrix, and α is the restart probability controlling the balance between local and global exploration [6].

k-Core Decomposition for Network Activation Analysis

The k-core decomposition method provides a systematic approach for analyzing network resilience and identifying critical regions for disease activation. The protocol involves: (1) Network preparation by compiling the relevant molecular network; (2) Iterative pruning by repeatedly removing all nodes with degree less than k until no more nodes can be removed; (3) k-core identification where the remaining nodes form the k-core; (4) Increasing k by incrementing k and repeating the process to identify higher k-cores; (5) Activation mapping by correlating disease-associated genes with specific k-core levels [25].

This methodology has revealed that for power-law networks with γ > 3, epidemic activation in modified SIS dynamics involves collective network activation across essentially the entire network, while standard SIS activation is triggered primarily by hubs [25]. This approach helps identify network regions most critical for maintaining functional integrity and those most vulnerable to targeted interventions.

Visualization of Network Analysis Workflows

Visualization of k-Core Decomposition Process

Research Reagent Solutions for Network Medicine

Implementing network medicine approaches requires specialized computational tools, data resources, and analytical frameworks. The table below summarizes essential resources for investigating network robustness and fragility in disease contexts.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Network Medicine Investigations

| Resource Category | Specific Resource/Technology | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Network Databases | Protein-Protein Interaction Networks (STRING, BioGRID) | Provide foundational network structures for analysis |

| Phenotype Ontologies | Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) | Standardize phenotypic descriptions for correlation studies |

| Network Analysis Platforms | Cytoscape with Network Propagation Plugins | Enable visualization and analysis of disease modules |

| k-Core Decomposition Tools | NetworkX, igraph libraries | Identify critical network regions and resilience properties |

| Epidemic Modeling Frameworks | Custom SIS Model Implementations | Simulate disease spread on molecular networks |

| Data Integration Resources | GWAS Catalog, ClinVar | Link genetic variants to disease associations and phenotypes |

Implications for Therapeutic Intervention Development

Network-Based Drug Target Identification

The network perspective revolutionizes therapeutic intervention by shifting focus from single targets to entire functional modules. Approaches that locate disease-related modules enable researchers to: (1) filter initial gene sets to discard or add genes based on their proximity to established disease modules; (2) predict novel genes potentially associated with diseases that might be more "druggable"; (3) relate diseases to specific biological functions due to the relationship between topological modules and functional modules; and (4) understand molecular mechanisms through the network context of disease genes, enabling the design of interventions aimed at rewiring malfunctioning networks [6].

Cancer research exemplifies this approach, where studies have demonstrated that the transition from health to disease is characterized by the concentration of mutated genes in network modules rather than a general increase in mutation numbers [6]. Even in highly complex diseases involving hundreds to thousands of genes, these tend to concentrate in a reduced number of modules/pathways, providing focused intervention points [6].

Leveraging Network Fragility for Selective Interventions

The inherent fragility of certain network structures provides strategic opportunities for therapeutic interventions. Research on percolation processes reveals that networks with power-law degree distributions display specific vulnerability profiles, where targeted removal of highly connected hubs can rapidly fragment the network [24]. This principle translates to therapeutic strategies that intentionally disrupt disease modules by targeting critical hub proteins or fragile network connections.

The dual behavior observed in epidemic models on complex networks further informs intervention strategies [25]. For diseases operating through mechanisms analogous to standard SIS dynamics with γ > 3, where activation is triggered by hubs, interventions can focus on these critical nodes. Conversely, for diseases following modified SIS dynamics with collective network activation, broader network-modulating approaches may be necessary. This framework enables more precise matching of intervention strategies to the specific network properties of different disease states.

Methodologies and Applications: From Target Identification to Drug Repurposing

The complexity of human diseases, particularly multifactorial conditions like cancer, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative disorders, necessitates a shift from a reductionist, single-omics view to a holistic, systemic perspective. Network Medicine has emerged as a discipline that approaches human pathologies from this systemic point of view by representing biological systems as complex networks of interacting molecular components [6]. In these networks, nodes represent entities such as genes, proteins, or metabolites, and edges represent any type of generic relationship between them, such as physical interactions, chemical transformations, or regulatory influences [6]. The foundational principle underpinning this approach is the "disease module hypothesis," which posits that genes or proteins associated with a specific disease tend to cluster together in a specific neighborhood of the molecular network [6]. Even for complex diseases involving hundreds to thousands of genes, these tend to concentrate in a reduced number of topological modules, which often correspond to functional modules like biological pathways or macromolecular complexes [6]. This network-based framework enables researchers to move beyond the "one-gene, one-disease" paradigm and instead investigate the broader molecular context and interactions that give rise to pathological states, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of disease pathophysiology [6] [26].

The integration of multi-omics data—encompassing genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—is crucial for constructing a detailed map of these disease modules. Each omics layer provides a unique and partial view of the complex molecular regulatory networks underlying health and disease [27]. Metabolomics, in particular, plays a pivotal role by reflecting both endogenous metabolic pathways and external factors such as diet, drugs, and lifestyle, thereby bridging the gap between genotypes and observable phenotypes [27]. However, integrating these diverse data types presents significant challenges due to their high dimensionality, heterogeneity, and noise [27] [26]. This whitepaper serves as a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals, detailing advanced methods for constructing and analyzing multi-layered disease networks to elucidate pathological mechanisms and identify novel therapeutic targets.

Data Integration Methodologies for Network Construction

Constructing a comprehensive disease network begins with the collection and curation of data from multiple molecular layers. The following table summarizes the primary omics data types, their descriptions, and common public sources used in network construction.

Table 1: Multi-Omics Data Types and Sources for Network Construction

| Omics Data Type | Biological Significance | Example Data Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Provides information on genetic variations (e.g., SNPs, mutations) that may predispose to or cause disease. | TCGA, GWAS Catalog |

| Transcriptomics | Reveals gene expression changes across conditions, indicating active biological processes. | TCGA, GTEx Database [28] |

| Proteomics | Identifies and quantifies proteins and their post-translational modifications, the key functional actors. | HIPPIE Database [28] |

| Metabolomics | Reflects the ultimate downstream product of cellular processes, closest to the phenotype. | HMDB [27] |

| Prior Knowledge & Pathways | Provides curated context on molecular relationships, interactions, and functional pathways. | KEGG, STRING, REACTOME, Gene Ontology, HuRI, TRRUST [27] [28] |

Computational Frameworks for Data Integration

Several computational strategies exist for integrating these diverse omics data, each with distinct strengths and weaknesses. They can be broadly categorized as follows:

- Statistical Integration Methods: These methods, such as canonical correlation analysis, identify shared patterns across datasets but often struggle to capture the complex, non-linear relationships inherent in biological systems [27].

- Network-Based Integration: This approach maps molecular components and their relationships onto a unified graph, providing a holistic view of the system. A key technique is the construction of a multiplex network, where different layers represent different biological scales (e.g., genome, transcriptome, proteome, phenome), all connected via shared genes [28]. This allows for the systematic evaluation of a genetic defect's impact across all levels of biological organization [28].

- Machine and Deep Learning (ML/DL) Approaches: These methods are powerful for uncovering hidden patterns in high-dimensional data. Ensemble models like Random Forests (RFs) are robust to noise and useful for feature selection [27]. More recently, Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) have shown remarkable success. GCNs are a type of deep learning designed to work on graph structures, capable of propagating and refining node attributes by aggregating information from a node's neighbors [27]. Frameworks like MODA (Multi-Omics Data Integration Analysis) leverage GCNs with attention mechanisms to integrate initial feature importance scores derived from multiple ML methods (like t-tests, fold change, RF, and LASSO) and map them onto a biological knowledge graph, thereby mitigating data noise and capturing intricate molecular relationships [27].

Technical Protocols for Network Construction and Analysis

Protocol 1: Constructing a Disease-Specific Biological Knowledge Graph

This protocol details the steps for building a context-aware network that integrates prior knowledge with experimental omics data.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Network Construction

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Protocol | Key Features / Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| KEGG, REACTOME, STRING | Provides curated molecular relationships for backbone network. | Source of pathway, physical, and functional interactions. |

| HMDB, BRENDA | Incorporates metabolomic context and enzyme relationships. | Essential for integrating metabolites into the molecular network. |

| TCGAbiolinks R Package | Facilitates programmatic access to omics data from TCGA. | Standardizes data acquisition from large public repositories. |