Navigating the Challenges in Dynamic Model Calibration: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Dynamic model calibration is a critical, yet often under-standardized, step in creating credible computational models for biomedical research and drug development.

Navigating the Challenges in Dynamic Model Calibration: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

Dynamic model calibration is a critical, yet often under-standardized, step in creating credible computational models for biomedical research and drug development. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current landscape, challenges, and best practices in calibrating dynamic models, with a focus on infectious disease and pharmacological applications. We explore the foundational purpose of calibration, review methodological advances and common pitfalls, and provide a structured framework for troubleshooting and validation. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this review synthesizes recent evidence to offer practical guidance for enhancing the transparency, reproducibility, and reliability of calibrated models used to inform public health policy and clinical decisions.

Why Calibrate? Establishing the Purpose and Critical Gaps in Dynamic Modeling

Model calibration is a fundamental process in computational science and data-driven modeling, serving as a critical bridge between theoretical constructs and real-world observations. It is defined as the process of adjusting model parameters or functions to match an existing dataset, which can be conducted through trial-and-error or formulated as an optimization task to minimize the difference between data and model output [1]. In the broader context of dynamic model calibration research, challenges arise from increasing model complexity, data heterogeneity, and the need for robust validation frameworks that ensure model reliability across diverse applications.

The critical importance of calibration extends across numerous domains, from building energy simulation [2] and healthcare technology assessment [3] to machine learning classification systems [4] [5]. As models grow more sophisticated, the calibration process ensures they remain grounded in empirical reality, providing decision-makers with trustworthy predictions for critical applications.

Theoretical Foundations of Model Calibration

Core Definitions and Concepts

At its essence, model calibration concerns the agreement between a model's probabilistic predictions and observed empirical frequencies [4]. A perfectly calibrated model demonstrates that when it predicts an event with probability c, that event should occur approximately c proportion of the time [4]. For example, if a weather forecasting model predicts a 70% chance of rain on multiple days, roughly 70% of those days should actually experience rain for the model to be considered well-calibrated [4].

This process is distinct from but related to model validation and verification. While calibration focuses on minimizing the difference between model predictions and observed data, validation involves comparing model output to an independent dataset not used during calibration, and verification checks the model for internal inconsistencies, errors, and bugs [1] [3]. Together, these processes form a comprehensive framework for establishing model credibility.

The Calibration Problem as Mathematical Optimization

Fundamentally, calibration can be formulated as a mathematical optimization problem where the goal is to minimize an objective function that quantifies the goodness of fit between model predictions and experimental data [1]. A common approach uses error models such as:

[E = \sum{i=1}^n \frac{(xi - yi)^2}{yi^2}]

which quantifies the distance between model output (xi) and observed data (yi) [1]. The calibration process seeks parameter values that minimize this error function, bringing model outputs into closer alignment with empirical observations.

Calibration Metrics and Evaluation Frameworks

Quantitative Metrics for Calibration Assessment

Table 1: Key Metrics for Evaluating Model Calibration

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation | Strengths | Limitations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected Calibration Error (ECE) | (ECE = \sum_{m=1}^M \frac{ | B_m | }{n} | \text{acc}(Bm) - \text{conf}(Bm) |) [4] | Measures how well model probabilities match observed frequencies | Simple, intuitive interpretation | Sensitive to binning strategy; only considers maximum probabilities |

| Maximum Calibration Error (MCE) | Maximum error across probability bins [1] | Identifies worst-case calibration discrepancy | Highlights extreme miscalibration | Doesn't represent overall calibration performance | ||

| Brier Score | Mean squared difference between predicted probabilities and actual outcomes [4] | Comprehensive measure of probabilistic prediction accuracy | Evaluates both calibration and refinement | Difficult to decompose calibration component | ||

| Coefficient of Determination (R²) | Proportion of variance in data explained by the model [1] | Measures overall model fit to data | Common, widely understood metric | Doesn't specifically target probability calibration |

Visual Assessment Tools

Beyond quantitative metrics, visual diagnostic tools play a crucial role in assessing calibration. Reliability diagrams (also known as calibration plots) illustrate the relationship between predicted probabilities and observed frequencies, typically by binning predictions and plotting mean predicted probability against observed frequency in each bin [1] [5].

The probably package in R provides multiple approaches for creating calibration plots, including binned plots (grouping probabilities into discrete buckets), windowed plots (using overlapping ranges to handle smaller datasets), and model-based plots (fitting a classification model to the events against estimated probabilities) [5]. These visualizations enable researchers to identify specific regions where models may be under- or over-confident in their predictions.

Techniques and Algorithms for Model Calibration

Methodological Approaches

Table 2: Classification of Model Calibration Techniques

| Category | Methods | Typical Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-processing Methods | Temperature scaling, isotonic regression, Platt scaling [1] [4] | Machine learning classifiers, neural networks | Computationally efficient; applied after model training |

| Optimization-based Methods | Least squares optimization, Bayesian optimization, population-based stochastic search [1] [2] | Physical systems, building energy models, hydrological models | Requires careful specification of objective function |

| Parallel Computing Frameworks | Parallel random-sampling-based algorithms, Latin Hypercube Sampling, Generalized Likelihood Uncertainty Estimation (GLUE) [1] | Complex models with long simulation times | Reduces computational burden; enables extensive parameter exploration |

| Online/Adaptive Methods | State estimation, data fusion techniques, recursive parameter updates [1] | Systems with continuous data streams, digital twins | Maintains calibration as new data becomes available |

Implementation Workflows

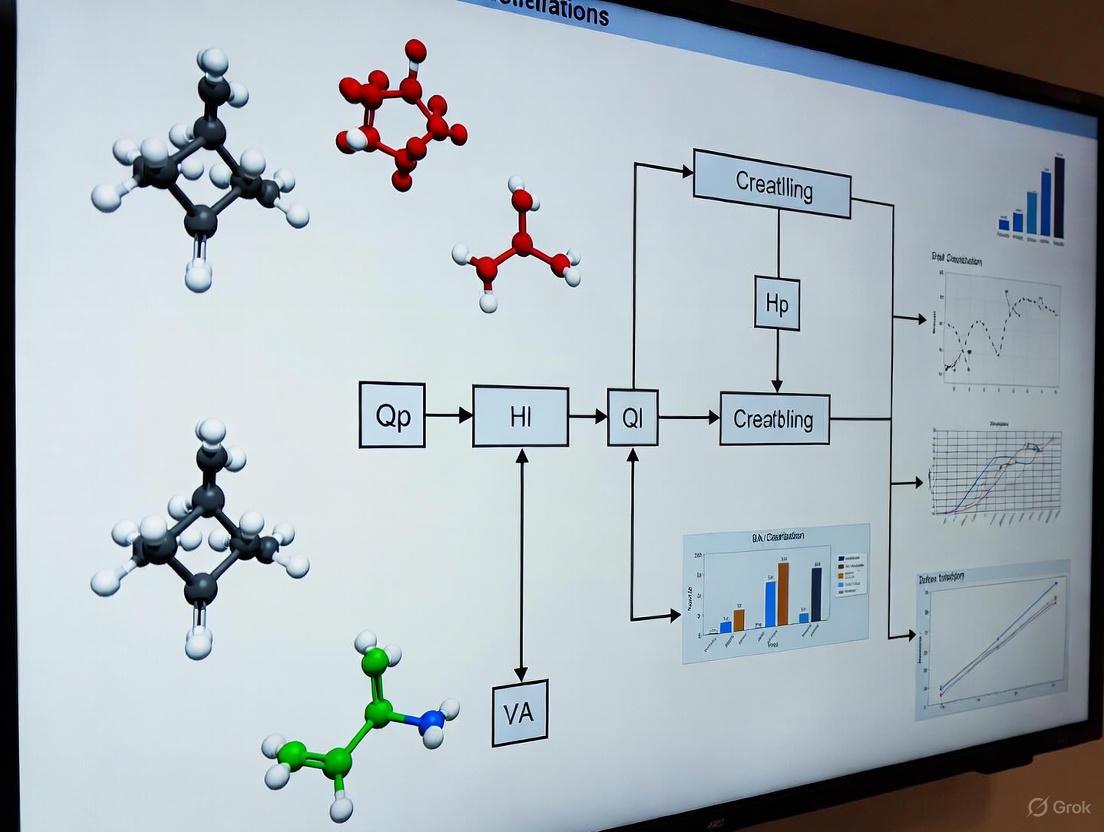

The calibration workflow typically follows a systematic process that begins with model specification and proceeds through parameter estimation, validation, and potential refinement. The following diagram illustrates a generalized calibration workflow applicable across multiple domains:

General Model Calibration Workflow: This diagram illustrates the iterative process of model calibration, from initial setup through validation and potential refinement.

Domain-Specific Applications

Healthcare and Medical Decision Making

In health technology assessment, calibration plays a crucial role in ensuring models accurately represent disease progression and treatment effects [3]. The process of "parameter estimation" is used to fit unknown parameters like kinetic rate constants and initial concentrations to experimental data, formulated as a mathematical optimization problem minimizing an objective function that measures goodness of fit [1]. For healthcare models, validation techniques include face validity (expert review), internal validation (comparison with data used in development), external validation (comparison with independent data), and predictive validation (assessing accuracy on future observations) [3].

Building Energy Modeling

The building energy modeling (BEM) domain faces significant challenges with the "performance gap" between simulation predictions and actual measurements [2]. Calibration serves as a critical step in addressing these discrepancies by systematically adjusting uncertain parameters within BEM to better align simulation predictions with actual measurements [2]. This process is essential for applications such as measurement and verification, retrofit analysis, fault detection and diagnosis, and building operations and control [2].

Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence

In machine learning, particularly for classification models, poor calibration can lead to unreliable posterior probabilities that negatively affect trustworthiness and decision-making quality [1] [4]. Modern convolutional neural networks often produce posterior probabilities that do not reliably reflect true empirical probabilities [1]. Methods such as temperature scaling have been shown to improve calibration error metrics in these networks by adjusting neural network logits before converting them to probabilities [1].

Experimental Protocols and Research Reagents

Essential Research Components

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Calibration Experiments

| Tool/Category | Example Implementations | Function in Calibration Process |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization Algorithms | Bayesian optimization, genetic algorithms, particle swarm optimization [1] [2] | Efficiently search parameter space to minimize objective function |

| Statistical Software Packages | probably (R), scikit-learn (Python), custom Bayesian tools [5] | Provide calibration diagnostics, visualization, and metrics calculation |

| Parallel Computing Frameworks | Parallel random-sampling algorithms, Latin Hypercube Sampling [1] | Distribute computationally intensive calibration across multiple processors |

| Validation Datasets | Holdout datasets, cross-validation partitions, external data sources [3] | Provide independent assessment of calibration performance |

| Visualization Tools | Reliability diagrams, calibration plots, residual analysis [1] [5] | Enable qualitative assessment of calibration quality |

Detailed Calibration Protocol

A comprehensive calibration protocol involves multiple methodological stages:

Problem Formulation: Clearly define the model purpose, key outputs of interest, and criteria for successful calibration.

Data Preparation: Collect and preprocess observational data for calibration, ensuring representative coverage of the model operating conditions.

Parameter Selection: Identify which model parameters to calibrate, typically focusing on those with high uncertainty and significant influence on outputs.

Objective Function Specification: Define mathematical criteria for measuring fit between model outputs and observational data.

Optimization Execution: Apply appropriate algorithms to identify parameter values that minimize the objective function.

Validation Assessment: Test calibrated model performance against independent data not used in the calibration process.

Sensitivity Analysis: Evaluate how changes in parameters affect model outputs to identify influential factors and potential identifiability issues.

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual structure of a calibration system, showing the relationship between model parameters, the computational model, and the calibration process:

Calibration System Architecture: This diagram shows how the calibration process interacts with model components, parameters, and observational data to produce improved parameter estimates.

Challenges and Future Directions

Persistent Challenges in Model Calibration

Dynamic model calibration research faces several significant challenges:

Computational Complexity: Calibrating complex models often requires a large number of simulations, creating substantial computational demands [1] [2]. Parallelization can improve speed, but communication overhead in distributed systems often reduces parallel efficiency as tasks exceed available processing units [1].

Data Limitations: Sample selection bias, dataset shift (including covariate shift, probability shift, and domain shift), and non-representative training data can significantly impact model performance in real-world applications [1].

Parameter Identifiability: Complex models with large parameter spaces may suffer from non-identifiability, where different parameter combinations yield similar outputs, making unique calibration impossible [1] [2].

Overfitting: Calibration may produce models that fit the calibration dataset well but perform poorly on new data, especially for models with many parameters relative to available data [1].

Methodological Gaps: Despite growing interest, calibration remains under-standardized, often impeded by limited guidance, insufficient data, and ambiguity regarding appropriate methods and metrics across domains [2].

Emerging Solutions and Research Frontiers

Current research addresses these challenges through several promising avenues:

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: AI methods show promise for automating and enhancing calibration processes, though challenges remain in real-world deployment [2]. Techniques like Bayesian neural networks and Gaussian processes offer principled uncertainty quantification alongside calibration.

Advanced Uncertainty Quantification: Modern approaches better characterize and propagate uncertainties through the modeling chain, from input parameters to final predictions [2]. This includes sophisticated sensitivity analysis and Bayesian methods that explicitly represent epistemic and aleatoric uncertainties.

Transfer Learning and Domain Adaptation: Methods that leverage knowledge from related models or domains help address data scarcity issues, particularly for novel systems with limited observational data [1].

Standardized Benchmarks and Open-Source Tools: Growing availability of benchmark datasets and open-source calibration tools promotes reproducibility and methodological comparison across studies [2] [5].

Model calibration represents a fundamental process for aligning computational models with empirical evidence across diverse scientific and engineering disciplines. As models grow increasingly complex and influential in decision-making, rigorous calibration methodologies become essential for ensuring their reliability and trustworthiness. The continued development of robust, efficient calibration techniques—particularly those addressing dynamic systems, uncertainty quantification, and computational constraints—remains a critical research frontier with substantial practical implications across domains from healthcare to energy systems to artificial intelligence.

The Critical Role of Calibration in Bridging the Model Performance Gap

The discrepancy between simulation predictions and actual measurements, commonly known as the performance gap, presents a fundamental challenge across computational modeling disciplines. As models are increasingly used beyond the design phase to inform critical decisions in fields ranging from building energy management to infectious disease forecasting and drug development, bridging this gap has become paramount [2]. The well-known adage by George Box that "All models are wrong, but some are useful" underscores the importance of acknowledging modeling limitations while systematically striving for greater utility in real-world applications [2]. Model calibration serves as the crucial methodological bridge between theoretical simulations and empirical reality—a systematic process of adjusting uncertain parameters within a computational model to better align its predictions with observed measurements [2].

The performance gap manifests differently across domains but shares common underlying challenges. In building energy modeling, this gap represents the difference between projected and actual energy consumption [2]. In infectious disease modeling, it appears as discrepancies between predicted and observed transmission dynamics [6]. In chemical synthesis, it emerges as the challenge of converting theoretical reaction pathways into executable experimental procedures [7]. In all these contexts, calibration provides the methodological foundation for reducing these discrepancies and enhancing model credibility before deployment in critical applications.

Foundational Calibration Methodologies and Metrics

Core Calibration Approaches

Calibration methodologies span a spectrum from traditional manual approaches to advanced automated techniques. The choice of method depends on model complexity, data availability, computational resources, and the intended application of the calibrated model.

- Manual Calibration: Traditional approach relying on expert knowledge and iterative parameter adjustment, often using trial-and-error methods.

- Mathematical Optimization: Formal numerical approaches that systematically vary parameters to optimize goodness-of-fit measures, including gradient-based methods and metaheuristics [8].

- Bayesian Methods: Statistical approaches that estimate posterior parameter distributions, explicitly quantifying uncertainty through techniques like Markov Chain Monte Carlo.

- Machine Learning-Augmented Calibration: Emerging techniques that leverage AI to accelerate parameter search or learn calibration mappings directly from data [2].

Evaluation Metrics and Standards

Rigorous evaluation metrics are essential for assessing calibration quality. The building energy modeling field has established two key statistical metrics for quantifying calibration accuracy [2]:

- Coefficient of Variation of the Root Mean Square Error (CVRMSE): Measures the variation in errors between simulated and measured data, with lower values indicating better calibration.

- Normalized Mean Bias Error (NMBE): Quantifies systematic over- or under-prediction in the model.

However, research indicates that fixed calibration thresholds may be insufficient across diverse contexts [2]. Effective calibration requires modelers to critically navigate trade-offs between model complexity, data availability, computational resources, and stakeholder needs rather than adhering rigidly to generic benchmarks.

Table 1: Key Statistical Metrics for Calibration Quality Assessment

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Common Thresholds |

|---|---|---|---|

| CVRMSE | $\sqrt{\frac{\sum{i=1}^n (yi - \hat{y}_i)^2}{n-p}} / \bar{y}$ | Hourly variation accuracy | Lower values indicate better calibration |

| NMBE | $\frac{\sum{i=1}^n (yi - \hat{y}_i)}{(n-p)\bar{y}}$ | Systematic bias | Values close to zero preferred |

| Normalized Levenshtein Similarity | (For sequence comparison) | Procedure sequence accuracy | 50-100% for chemical procedures [7] |

Domain-Specific Calibration Challenges and Applications

Infectious Disease Model Calibration

In infectious disease modeling, calibration is frequently employed to estimate parameters for evaluating intervention impacts, with parameters calibrated primarily because they are unknown, ambiguous, or scientifically relevant beyond mere model execution [6]. The comprehensive PIPO (Purpose-Input-Process-Output) framework has been proposed to standardize calibration reporting, emphasizing four critical components [6]:

- Purpose: The goal of calibration and parameters targeted

- Inputs: Data and evidence used for fitting

- Process: Algorithms, software, and computational methods

- Outputs: Calibrated parameter sets and their uncertainty

This framework addresses the concerning finding that only 20% of infectious disease models provide accessible implementation code, significantly hampering reproducibility [6].

Cross-Domain Data Integration Frameworks

The CrossLabFit methodology represents a significant advancement for integrating qualitative and quantitative data across multiple laboratories, overcoming constraints of single-lab data collection [8]. This approach harmonizes disparate qualitative assessments into a unified parameter estimation framework by using machine learning clustering to represent qualitative constraints as dynamic "feasible windows" that capture significant trends to which models must adhere [8].

The integrative cost function in CrossLabFit combines quantitative and qualitative elements:

$J(\theta) = J{quantitative} + J{qualitative}$

Where $J{quantitative}$ measures differences between simulated variables and empirical data, while $J{qualitative}$ penalizes deviations from feasible windows derived from multi-lab qualitative constraints [8].

Chemical Synthesis Procedure Prediction

In chemical synthesis, the Smiles2Actions model demonstrates how AI can convert chemical equations to fully explicit sequences of experimental actions, achieving normalized Levenshtein similarity of 50% for 68.7% of reactions [7]. Trained on 693,517 chemical equations and associated action sequences extracted from patents, this approach can predict adequate procedures for execution without human intervention in more than 50% of cases [7].

Table 2: Calibration Applications Across Domains

| Domain | Primary Calibration Challenge | Characteristic Methods | Notable Advances |

|---|---|---|---|

| Building Energy | Performance gap between predicted/actual consumption | CVRMSE, NMBE metrics | AI methods for operational fault detection [2] |

| Infectious Disease | Parameter identifiability with limited data | Compartmental/individual-based models | PIPO reporting framework [6] |

| Chemical Synthesis | Converting equations to executable procedures | Sequence-to-sequence models | Smiles2Actions (50%+ autonomous execution) [7] |

| Biomedical Science | Integrating multi-lab data with biological variability | CrossLabFit feasible windows | Unified qualitative/quantitative cost functions [8] |

Advanced Calibration Workflows and Protocols

Multi-Model Calibration Framework

In analytical chemistry, Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) faces long-term reproducibility challenges. A novel multi-model calibration approach marked with characteristic lines establishes multiple calibration models using data collected at different time intervals, with characteristic line information reflecting variations in experimental conditions [9]. During analysis of unknown samples, the optimal calibration model is selected through characteristic matching, significantly improving average relative errors and standard deviations compared to single calibration models [9].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the comprehensive calibration process integrating multiple data sources and validation steps:

Experimental Protocol: CrossLabFit Implementation

For researchers implementing the CrossLabFit methodology, the following detailed protocol enables integration of multi-lab data [8]:

Materials and Software Requirements

- Python 3.8+ with pyPESTO, NumPy, SciPy, and scikit-learn

- GPU acceleration support for differential evolution algorithms

- Dataset A (primary quantitative data for model explanation)

- Dataset B+ (auxiliary qualitative data from multiple labs)

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Formulate Mathematical Model: Express the biological system using Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) with parameter set $\theta$

- Compile Multi-Lab Data: Collect both quantitative datasets and qualitative observations from available literature

- Cluster Qualitative Data: Apply machine learning clustering to auxiliary data to define "feasible windows" representing significant trends

- Implement Cost Function: Combine quantitative and qualitative components: $J(\theta) = J{quantitative} + J{qualitative}$

- Configure Optimization: Set up GPU-accelerated differential evolution to navigate the complex cost function landscape

- Execute Parameter Estimation: Run optimization to identify parameter sets that minimize $J(\theta)$ while respecting feasible windows

- Validate with Hold-Out Data: Assess calibrated model against data not used in the calibration process

- Perform Identifiability Analysis: Check practical and structural identifiability of parameters using profile likelihood

Expected Outcomes

- Significantly improved model accuracy and parameter identifiability

- Narrowed plausible parameter space through incorporation of qualitative constraints

- Enhanced biological faithfulness of model trajectories through feasible windows

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Calibration Experiments

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paragraph2Actions | Natural language processing of experimental procedures | Chemical synthesis automation | Extracts action sequences from patent text [7] |

| CrossLabFit Framework | Integration of multi-lab qualitative/quantitative data | Biomedical model calibration | Uses feasible windows to constrain parameters [8] |

| PIPO Reporting Framework | Standardized calibration documentation | Infectious disease models | 16-item checklist for reproducibility [6] |

| GPU-Accelerated Differential Evolution | High-performance parameter optimization | Complex model calibration | Essential for navigating high-dimensional parameter spaces [8] |

| Reaction Fingerprints | Chemical similarity assessment | Retrosynthetic analysis and procedure prediction | Enables nearest-neighbor model for reaction procedures [7] |

| Transformer Architectures | Sequence-to-sequence prediction | Experimental procedure generation | BART model for chemical action sequences [7] |

Future Directions and Emerging Challenges

As calibration methodologies evolve, several promising research directions are emerging. AI-augmented calibration shows particular promise, with machine learning approaches being developed to automate parameter estimation and reduce computational burdens [2]. However, significant challenges remain in the real-world deployment of these methods, particularly regarding data requirements and generalizability across diverse contexts.

The standardization of calibration reporting through frameworks like PIPO [6] represents another critical direction, addressing the current reproducibility crisis in computational modeling. As one review found, only 20% of infectious disease models provide accessible implementation code [6], highlighting the urgent need for more transparent reporting practices.

Future research must also address the tension between model complexity and identifiability. While model simplification is a common approach to tackle identifiability problems, this dramatically limits the holistic understanding of complex biological problems [8]. Methodologies like CrossLabFit that enable calibration of complex models through innovative use of multi-source data offer promising alternatives to simplification.

Model calibration stands as a critical discipline for bridging the pervasive performance gap between theoretical simulations and empirical observations across scientific domains. By systematically adjusting uncertain parameters to align model predictions with measured data, calibration transforms theoretically interesting but practically limited models into trustworthy tools for decision support. The emerging methodologies surveyed—from CrossLabFit's multi-lab data integration to PIPO's standardized reporting and Smiles2Actions' experimental procedure prediction—demonstrate the dynamic evolution of calibration science.

As computational models assume increasingly prominent roles in guiding decisions with significant societal impacts, from public health policy to energy planning and drug development, the rigor and transparency of calibration practices become paramount. The continued development and adoption of robust calibration frameworks will be essential for ensuring that these powerful tools deliver on their promise of illuminating complex systems while faithfully representing empirical reality.

Reproducibility is a cornerstone of the scientific method, yet numerous fields currently face a crisis characterized by widespread inconsistencies in reporting and significant challenges in reproducing research findings. This challenge is acutely present in specialized research areas that depend on complex model calibration, where the transparency and completeness of methodological reporting directly impact the reliability of evidence used for critical decision-making. Within the context of dynamic model calibration research, these issues manifest as incomplete descriptions of calibration purposes, inputs, processes, and outputs, ultimately hindering the replication of studies and validation of their conclusions. This technical review examines the current state of reporting inconsistencies across multiple research domains, quantifies their prevalence and impact, and proposes structured frameworks and toolkits designed to enhance methodological transparency and reproducibility.

Quantitative Evidence of Reporting Gaps

Recent systematic assessments across diverse scientific fields reveal consistent patterns of insufficient methodological reporting that undermine reproducibility. The tables below synthesize quantitative findings from scoping reviews and pilot studies that evaluated the completeness of reporting in systematic reviews and infectious disease modeling.

Table 1: Reporting Completeness in Nutrition Science Systematic Reviews [10]

| Assessment Tool | Domain Evaluated | Completion Rate | Critical Weaknesses Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMSTAR 2 | Methodological Quality | Critically Low Quality | Critical flaws found in all 8 sampled SRs |

| PRISMA 2020 | Overall Reporting Transparency | 74% (Item fulfillment) | Unfulfilled items related to methods and results |

| PRISMA-S | Search Strategy Reporting | 63% (Item fulfillment) | Inconsistent reporting of search methodologies |

Table 2: Calibration Reporting in Infectious Disease Models (Scoping Review of 419 Models) [6]

| Reporting Dimension | Completeness Rate | Key Omission Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose of Calibration | High | Justification for parameter selection |

| Calibration Inputs | Moderate | Insufficient detail on data sources and priors |

| Calibration Process | Variable | Incomplete description of algorithms and implementation |

| Calibration Outputs | Low | Only 20% provided accessible implementation code |

| Uncertainty Analysis | Low | Omission of confidence intervals or posterior distributions |

The data from nutrition science reveals that even systematic reviews conducted by expert teams to inform national dietary guidelines suffer from critical methodological weaknesses and suboptimal reporting transparency, particularly in documenting search strategies [10]. Similarly, in infectious disease modeling, a scoping review found that while the purpose of calibration was generally well-reported, the implementation details and outputs suffered from significant omissions, with only 20% of models providing accessible code necessary for replication [6]. This demonstrates a widespread pattern where critical methodological details remain inadequately documented, preventing independent verification and reproduction of findings.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Reproducibility

To systematically evaluate reproducibility, researchers have developed standardized assessment methodologies. The following protocols detail the experimental approaches used to generate the quantitative evidence presented in Section 2.

Protocol for Assessing Systematic Review Reproducibility

This protocol was applied to evaluate the reliability and reproducibility of systematic reviews (SRs) produced by the Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review (NESR) team for the 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans [10].

Research Questions:

- Do the SRs report a transparent, complete, and accurate account of their process?

- Would reproducing the search strategy and data analysis change the original conclusions?

Sample Selection:

- A sample of 8 SRs from the DGA dietary patterns subcommittee was selected for KQ1.

- One SR on "dietary patterns and neurocognitive health" (n=26 studies) was selected for reproduction in KQ2.

Assessment Methods:

- Methodological Quality: Two independent reviewers applied the AMSTAR 2 tool to assess overall confidence and identify critical weaknesses.

- Reporting Transparency: The PRISMA 2020 checklist was applied to evaluate overall reporting completeness.

- Search Strategy Reporting: The PRISMA-S checklist was used to assess the transparency of literature search methodologies.

- Search Reproducibility: The original search strategy was evaluated using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) checklist and reproduced within a 10% margin of the original results.

Data Synthesis:

- Results from each assessment tool were summarized visually and critically evaluated.

- SRs were judged to have low reliability and reproducibility if tools identified critical flaws in methodological quality or substantial lack of reporting transparency.

Protocol for Scoping Review of Model Calibration Reporting

This protocol guided the scoping review of calibration practices in infectious disease transmission models to develop and apply the Purpose-Input-Process-Output (PIPO) reporting framework [6].

Search Strategy:

- Databases: Literature searches were conducted in multiple databases for studies published between January 1, 2018, and January 16, 2024.

- Focus Diseases: HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria transmission-dynamic models.

- Inclusion Criteria: Models that employed calibration to align parameters with empirical data or other evidence.

Framework Development:

- The PIPO framework was developed based on author expertise and published calibration best practices.

- The 16-item checklist was organized into four components: Purpose, Inputs, Process, and Outputs.

Data Extraction and Analysis:

- Two independent reviewers extracted data from 419 eligible models using the PIPO framework.

- Reporting comprehensiveness was assessed by quantifying the number of PIPO items adequately reported in each study.

- The association between model characteristics (structure, stochasticity) and calibration methods was analyzed.

Visualization of Reporting Frameworks and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate key frameworks and workflows developed to standardize reporting and enhance reproducibility across research domains.

ReproSchema Ecosystem for Standardized Data Collection

ReproSchema addresses inconsistencies in survey-based data collection through a schema-centric framework that standardizes assessment definitions and facilitates reproducible data collection [11].

PIPO Framework for Model Calibration Reporting

The Purpose-Input-Process-Output (PIPO) framework provides a standardized structure for reporting calibration methods in infectious disease models to enhance transparency and reproducibility [6].

The following table details key research reagent solutions and computational tools that support reproducible research practices in model calibration and evidence synthesis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Reproducible Calibration Research

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ReproSchema Ecosystem [11] | Standardizes survey-based data collection through schema-driven framework | Psychological assessments, clinical questionnaires, general surveys |

| PIPO Reporting Framework [6] | Standardizes reporting of model calibration purposes, inputs, processes, and outputs | Infectious disease transmission models |

| AMSTAR 2 Tool [10] | Critical appraisal tool for assessing methodological quality of systematic reviews | Evidence synthesis, guideline development |

| PRISMA 2020 & PRISMA-S [10] | Reporting checklists for systematic reviews and their search strategies | Literature reviews, meta-analyses |

| Open-Source Calibration Tools [2] | Software packages for building energy model calibration | Building performance simulation, energy efficiency analysis |

The current state of scientific reporting reveals widespread inconsistencies that significantly challenge reproducibility, particularly in specialized fields utilizing dynamic model calibration. Quantitative evidence from systematic reviews and scoping reviews demonstrates consistent patterns of insufficient methodological reporting, omission of critical implementation details, and limited sharing of analytical code. These reporting gaps impede independent verification of research findings, potentially compromising the evidence base used for clinical and policy decisions. The implementation of structured reporting frameworks like ReproSchema and PIPO, along with adherence to established methodological quality tools, presents a promising path toward enhanced transparency. For researchers in drug development and other fields dependent on complex modeling, adopting these standardized approaches and essential research tools is critical for ensuring that calibration processes and their outcomes are reproducible, reliable, and fit for purpose in informing high-stakes decisions.

The development of dynamic models, such as transmission-dynamic models for infectious diseases, is a cornerstone of modern scientific research for understanding complex systems and predicting their behavior. These models are characterized by parameters—fixed values or variables that determine model behavior. However, a critical and often challenging step in the modeling process is model calibration (or model fitting), which involves identifying parameter values so that model outcomes are consistent with observed data or other evidence [6] [12]. Inaccuracies in model calibration can result in inference errors, compromising the validity of modeled results that inform pivotal decisions, such as public health policies [6]. Despite its importance, the reporting of how calibration is conducted has historically been inconsistent, hampering reproducibility and potentially compromising confidence in the validity of studies [6] [12]. To address this gap, the Purpose-Inputs-Process-Outputs (PIPO) framework was developed as a standardized reporting framework for infectious disease model calibration, offering a structured approach to enhance transparency and reproducibility [6].

The PIPO Framework: Core Components and Definitions

The PIPO framework is a 16-item reporting checklist for describing calibration in modeling studies. It was developed based on expertise in conducting calibration for transmission-dynamic models and published guidance on calibration best practices [6]. Its primary goal is to ensure reproducibility by facilitating clear communication of calibration aims, methods, and results. The framework is built upon four interconnected components, detailed below.

Purpose

The Purpose component establishes the goal of the calibration and the scientific problem being addressed. It answers the question: Why is the calibration being performed? The purpose provides the context, which could be to infer the value of an epidemiologically important parameter (e.g., the duration of an incubation period) or to enable prediction of disease trends under a range of interventions to support policy decisions [6] [12]. Clearly articulating the purpose is the first step in defining the calibration exercise.

Inputs

The Inputs component details the essential elements fed into the calibration algorithm. This involves reporting on two key aspects:

- Parameters to be Calibrated: This includes specifying which parameters are calibrated, justifying their selection, and reporting whether prior knowledge (e.g., pre-existing data, estimates, or expert opinion) was incorporated to inform their calibration [12].

- Calibration Targets: This involves describing the empirical data or published estimates used as targets for the model to match. Reporting includes the number of targets, the type of data (e.g., incidence, prevalence), and whether they are raw data or statistical summaries [12].

The clarity of input reporting is critical because choices about which parameters to fix and which to calibrate, as well as the type of data used as a target, directly impact parameter identifiability and the resulting estimates [12].

Process

The Process component describes the execution of the calibration. It encompasses the methodological details required to replicate the procedure, including:

- The name of the calibration method (e.g., Approximate Bayesian Computation, Markov-Chain Monte Carlo) and a description of how it works [12].

- The goodness-of-fit (GOF) measure used to quantify the agreement between model outcomes and calibration targets.

- Implementation details, such as the programming language, software versions, and the accessibility of the implementation code [12].

This component provides the "recipe" for how the calibration was conducted, moving from inputs to outputs.

Output

The Output component characterizes the results of the calibration process. It requires reporting on:

- The form of the calibrated estimates, specifying whether they are a single "point estimate," multiple "sample estimates," or a "distribution estimate" [12].

- The size of the calibration outputs (e.g., the number of parameter sets retained).

- The uncertainty associated with the calibrated parameter estimates and corresponding model outcomes [12].

Thorough reporting of outputs is essential for interpreting the model's results and their reliability. The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and key elements of the PIPO framework.

Quantitative Evidence: A Scoping Review of Calibration Practices

To assess current calibration practices and the comprehensiveness of their reporting, the PIPO framework was applied in a scoping review of 419 infectious disease transmission models of HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria published between 2018 and 2024 [12]. The review systematically mapped how calibration is conducted and reported, providing valuable quantitative insights into the field. The following tables summarize the key findings.

Table 1: Model Characteristics and Calibration Methods from Scoping Review (n=419 models)

| Characteristic | Category | Number of Models | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Structure | Compartmental | 309 | 74% |

| Individual-Based (IBM) | 81 | 20% | |

| Other | 29 | 6% | |

| Analytical Purpose | Intervention Evaluation | 298 | 71% |

| Other (e.g., Forecasting, Mechanism) | 121 | 29% | |

| Primary Reason for Parameter Calibration | Parameter Unknown/Ambiguous | 168 | 40% |

| Value Scientifically Relevant | 85 | 20% | |

| Calibration Method Association | ABC more frequent with IBMs | Not Specified | - |

| MCMC more frequent with Compartmental | Not Specified | - |

Table 2: Comprehensiveness of Calibration Reporting (PIPO Framework Items)

| Reporting Completeness | Number of Models | Percentage | Key Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| All 16 PIPO items reported | 18 | 4% | Best practice exemplars |

| 11-14 PIPO items reported | 277 | 66% | Majority of studies |

| 10 or fewer items reported | 124 | 28% | Significant reporting gaps |

| Least Reported Item: Accessible Implementation Code | 82 | 20% | Major barrier to reproducibility |

The data reveal that the choice of calibration method is significantly associated with model structure and stochasticity. Furthermore, the reporting of calibration is heterogeneous, with the vast majority of models omitting several key items. The most notable gap is the availability of implementation code, which was accessible for only 20% of models, presenting a substantial barrier to reproducibility [12].

Experimental Protocols: A Detailed Methodology for Model Calibration

Drawing from the PIPO framework and established protocols for dynamic model calibration [13], the following section provides a detailed, actionable methodology for researchers. This protocol is designed to navigate challenges such as parameter identifiability, local minima, and computational complexity.

Workflow for Dynamic Model Calibration

The calibration process is iterative and can be visualized as a workflow encompassing all PIPO components. The diagram below outlines the key stages, from problem definition to output analysis.

Step-by-Step Protocol

Define Purpose and Scope:

- Formulate a precise scientific question the calibrated model should answer. For example: "What is the impact of a new vaccination program on malaria incidence over the next decade?" This defines the Purpose [6].

Specify Inputs:

- Parameters: Identify which model parameters are unknown or ambiguous. Justify their selection for calibration. Conduct a prior identifiability analysis (e.g., using profile likelihood) to check if parameters can be uniquely estimated from the available data. Incorporate prior knowledge by defining plausible bounds or formal prior distributions for each parameter [12] [13].

- Calibration Targets: Gather and pre-process empirical data (e.g., incidence, prevalence, mortality rates) to be used as targets. Ensure the targets are informative for the parameters being calibrated. The number of targets should ideally exceed the number of calibrated parameters.

Configure and Execute the Process:

- Algorithm Selection: Choose a calibration method appropriate for the model structure and data. For complex, stochastic models (e.g., Individual-Based Models), Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) is often suitable. For compartmental models, Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods are widely used [12].

- Goodness-of-Fit (GOF): Define a quantitative GOF measure, such as a sum of squared errors or a likelihood function, to evaluate the match between model outputs and calibration targets.

- Implementation: Code the model, the calibration algorithm, and the GOF measure in a programming language like R, Python, or C++. Document all software versions and settings.

Analyze Outputs:

- Parameter Estimates: Examine the resulting parameter values or distributions. Assess their practical identifiability and biological plausibility.

- Uncertainty Quantification: Report confidence intervals, credible intervals, or posterior distributions to communicate the uncertainty in the calibrated estimates [12].

- Model Fit: Visually and statistically assess how well the calibrated model reproduces the calibration targets. Use techniques like posterior predictive checks.

Validation and Reporting:

- Validate the calibrated model against a hold-out dataset not used in the calibration.

- Document the entire process comprehensively using the PIPO framework as a checklist to ensure all critical information is reported for reproducibility [6].

Successful implementation of the PIPO framework relies on a suite of computational tools and methodological approaches. The following table details key "research reagents" essential for dynamic model calibration.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Model Calibration

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior Knowledge | Informational Input | Informs parameter bounds and prior distributions, improving identifiability. | Using published estimates for a disease's latent period to constrain a calibrated parameter [12]. |

| Empirical Data | Calibration Target | Serves as the benchmark for evaluating model fit during calibration. | Historical incidence data for tuberculosis used to align model output with reality [12]. |

| Approximate Bayesian Computation (ABC) | Computational Process | A likelihood-free method for parameter inference, ideal for complex stochastic models. | Calibrating an individual-based model of HIV transmission where the likelihood is intractable [12]. |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) | Computational Process | A class of algorithms for sampling from a probability distribution, often a posterior distribution. | Precisely estimating parameter distributions and uncertainty in a compartmental malaria model [12]. |

| Goodness-of-Fit Metric | Analytical Process | Quantifies the discrepancy between model simulations and calibration targets. | Using a weighted sum of squared errors to fit a model to both prevalence and mortality data simultaneously. |

| Programming Environment (R, Python) | Implementation Platform | Provides the ecosystem for coding the model, calibration algorithm, and analysis. | Using Python with SciPy for optimization or R with rstan for Bayesian inference [12] [13]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Infrastructure | Provides the computational power needed for thousands of model runs required by methods like ABC and MCMC. | Running a large-scale parameter sweep for a complex, spatially-explicit transmission model. |

The PIPO framework provides a critical, structured methodology for addressing the pervasive challenges of transparency and reproducibility in dynamic model calibration research. By systematically guiding researchers to report on the Purpose, Inputs, Process, and Outputs of calibration, it mitigates the risks of inference errors that can compromise model-based decisions. Empirical evidence from a recent scoping review underscores the framework's necessity, revealing significant heterogeneity and frequent omissions in current reporting practices, particularly regarding the accessibility of implementation code [12]. The integration of the PIPO framework into the standard workflow for developing and reporting on dynamic models, as detailed in the provided protocols and toolkits, promises to enhance the credibility, reliability, and ultimate utility of computational models in scientific research and public health policy.

Dynamic model calibration in pharmacology is a critical process for translating in silico predictions into clinically viable insights. The primary challenge lies in accurately inferring unknown model parameters from observed data and systematically evaluating the impact of pharmacological interventions. This process is fundamental in drug development, where understanding complex drug-drug interactions (DDIs) can mitigate adverse effects and improve therapeutic outcomes. This guide details a computational framework designed to address these core challenges, enabling robust prediction of both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions.

Core Methodological Framework

The INDI (INferring Drug Interactions) algorithm provides a novel, large-scale in silico approach for DDI prediction [14]. Its design addresses two primary objectives: (1) predicting new cytochrome P450 (CYP)-related DDIs and non-CYP-related DDIs, and (2) creating a generalizable strategy for predicting interactions for novel drugs with no existing interaction data.

The algorithm operates on a pairwise inference scheme, calculating the similarity of a query drug pair to drug pairs with known interactions [14]. It employs seven distinct drug-drug similarity measures to determine the interaction likelihood. The framework was trained and validated on a comprehensive gold standard of 74,104 DDIs assembled from DrugBank and Drugs.com [14].

- Assembly of a DDI Gold Standard: The gold standard distinguishes between three interaction types [14]:

- CYP-related DDIs (CRDs): Both drugs are metabolized by the same CYP enzyme with supporting evidence for CYP involvement (10,106 interactions).

- Potential CYP-related DDIs (PCRDs): Both drugs are metabolized by the same CYP but lack direct evidence for CYP involvement in the interaction (18,261 interactions).

- Non-CYP-related DDIs (NCRDs): No shared CYP enzymes between the drugs (45,737 interactions). The final datasets for algorithm construction included 5,039 CRDs (spanning 352 drugs) and 20,452 NCRDs (spanning 671 drugs) after ensuring all similarity measures could be computed [14].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

The INDI Algorithm Workflow

The INDI algorithm functions through three sequential steps [14]:

- Construction of Drug-Drug Similarity Measures: Seven different similarity measures are assembled for each drug pair, including chemical similarity and ligand-based chemical similarity.

- Feature Construction: Classification features are built based on the computed similarity measures, creating a multidimensional profile for each drug pair.

- Classification and Prediction: A classifier is applied to the feature set to rank and predict new DDIs. The framework uses distinct sections of the gold standard (CRDs and NCRDs) to predict respective interaction types.

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow, from data assembly to the generation of clinical predictions:

Parameter Inference and Trait Prediction

A key extension of the INDI framework is its ability to infer interaction-specific traits, moving beyond binary prediction [14]. The methodology for parameter inference involves:

- Action Recommendation: The algorithm predicts the recommended clinical action upon co-administration of two drugs, classifying them into categories such as contraindicate, generally avoid, adjust dosage, or monitor therapy.

- CYP Isoform Inference: For interactions predicted to be CYP-related, the framework identifies the specific CYP isoforms (e.g., CYP2D6, CYP3A4) involved. This enables physicians to consider patient-specific genetic polymorphisms and seek alternative medications.

Validation and Clinical Prevalence Assessment

The experimental protocol included a large-scale validation to assess the algorithm's performance and clinical relevance [14]:

- Cross-Validation: The model was evaluated using cross-validation, achieving high specificity and sensitivity levels (Area Under the Curve, AUC ≥ 0.93).

- Application to Real-World Data: The validated model was applied to three clinical data sources:

- The FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS).

- Chronic medication records from hospitalized patients in Israel.

- Commonly administered drug combinations.

- Outcome Correlation: For the patient data, the frequency of hospital admissions was correlated with the administration of known or predicted severely interacting drugs.

Quantitative Results and Data Synthesis

Algorithm Performance and Clinical Impact

The application of the INDI framework yielded significant quantitative findings, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Summary of INDI Algorithm Performance and Clinical Prevalence Findings [14]

| Metric | Result | Context / Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-Validation AUC | ≥ 0.93 | Demonstrates high specificity and sensitivity in predicting DDIs. |

| FAERS Coverage | 53% of drug events | Potential connection to known (41%) or predicted (12%) DDIs. |

| Hospitalized Patients | 18% received interacting drugs | Patients received known or predicted severely interacting drugs. |

| Admission Correlation | Increased frequency | Associated with administration of severely interacting drugs. |

Gold Standard Data Composition

The composition of the interaction gold standard used for model training is detailed below.

Table 2: Composition of the Drug-Drug Interaction (DDI) Gold Standard [14]

| Interaction Type | Description | Number of Interactions | Drugs Spanned |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP-Related (CRD) | Both drugs metabolized by same CYP with evidence. | 10,106 | 352 |

| Potential CYP-Related (PCRD) | Both drugs metabolized by same CYP without direct evidence. | 18,261 | Not Specified |

| Non-CYP-Related (NCRD) | No shared CYP enzymes between drugs. | 45,737 | 671 |

| Total | Complete dataset from DrugBank and Drugs.com. | 74,104 | 1,227 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of computational DDI prediction models requires a foundation of specific data resources and software tools. The following table lists essential components for research in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Resources for Computational DDI Prediction

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Interaction Database | Source of known DDIs for model training and validation. | DrugBank [14], Drugs.com [14] |

| Chemical Structure Database | Provides data for calculating chemical similarity between drugs. | PubChem, ChEMBL |

| Adverse Event Reporting System | Real-world data for validating predictions and assessing clinical impact. | FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) [14] |

| CYP Metabolism Data | Curated information on which drugs are metabolized by specific CYP isoforms. | DrugBank, scientific literature |

| Similarity Computation Library | Software for calculating molecular and phenotypic similarity measures. | Open-source chemoinformatics toolkits (e.g., RDKit) |

| Machine Learning Framework | Environment for building and training the classification model. | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch |

Signaling Pathways and Pharmacodynamic Interactions

Pharmacodynamic (PD) interactions occur when drugs affect the same or cross-talking signaling pathways at their site of action [14]. Unlike pharmacokinetic interactions, PD interactions are not related to metabolism but to the pharmacological effect itself. The following diagram illustrates a generalized signaling pathway where two drugs can interact pharmacodynamically.

How to Calibrate: A Guide to Modern Methods, Frameworks, and Workflows

Calibration is a fundamental process in scientific research and engineering, involving the adjustment of model parameters so that outputs align closely with observed data or established standards [15]. In computational modeling, calibration (also referred to as model fitting) is the process of selecting values for model parameters such that the model yields estimates consistent with existing evidence [6]. This process is particularly crucial for dynamic models used in fields ranging from infectious disease epidemiology to emissions control systems, where accurate parameterization directly impacts model validity and predictive power.

The challenge of calibration has grown increasingly complex with the advancement of sophisticated computational models. As noted in research on infectious disease modeling, inaccuracies in calibration can result in inference errors, compromising the validity of modeled results that inform critical public health policies [6]. Similarly, in engineering applications, traditional manual calibration methods can require six or more weeks of intensive labor [16], creating significant bottlenecks in development and optimization processes. These challenges have driven the development of automated approaches that leverage machine learning and advanced optimization algorithms to accelerate calibration while improving accuracy and reproducibility.

Manual Calibration Approaches

Core Methodology and Process

Manual calibration represents the traditional approach to parameter estimation, relying heavily on human expertise and iterative adjustment. This process typically involves a skilled technician or researcher who makes incremental changes to model parameters based on observed discrepancies between model outputs and reference data [15]. The manual calibration workflow generally follows these stages:

Initial Setup: The instrument or model is prepared for calibration, which may involve stabilization, initialization, or establishing baseline conditions.

Parameter Adjustment: Based on domain knowledge and observed outputs, the technician makes deliberate changes to target parameters.

Performance Verification: The calibrated system is tested against known standards or validation data to assess accuracy.

Documentation: Results are recorded, including final parameter values, calibration date, and reference standards used.

This approach offers direct control over each calibration step, allowing experts to apply nuanced understanding of the system and make judgment calls that might challenge automated systems [15]. The flexibility of manual calibration makes it particularly valuable for novel or complex systems where established automated routines may not yet exist.

Applications and Limitations

Manual calibration remains prevalent in research contexts where models are highly specialized or where calibration frequency does not justify the development of automated solutions. In infectious disease modeling, for instance, manual approaches are often employed when working with novel model structures or when integrating diverse data sources [6].

However, manual calibration presents significant limitations. The process is inherently time-intensive and labor-intensive, with calibration of complex systems like diesel aftertreatment systems potentially requiring six or more weeks of expert work [16]. This approach also suffers from subjectivity and potential inconsistencies, as different technicians may apply different judgment criteria. Furthermore, the reliance on human expertise creates challenges for reproducibility, as the complete rationale for parameter choices may not be fully documented [6].

Automated Calibration Systems

Fundamental Principles

Automated calibration systems represent a paradigm shift from manual approaches, leveraging software and algorithms to perform calibration tasks with minimal human intervention. These systems employ optimization algorithms to systematically search parameter spaces, identifying values that minimize the discrepancy between model outputs and target data [15] [17]. The core principle involves defining an objective function (or cost function) that quantifies this discrepancy, then applying numerical optimization techniques to find parameter values that minimize this function.

A key advantage of automated systems is their ability to execute complex calibration routines consistently and document the process comprehensively. As noted in infectious disease modeling research, clarity in reporting calibration procedures is essential for reproducibility and credibility [6]. Automated systems inherently generate detailed logs of parameter choices, optimization paths, and convergence metrics, addressing a significant limitation of manual approaches.

Machine Learning-Enhanced Calibration

Recent advances have integrated machine learning techniques with traditional optimization approaches, creating hybrid methods that offer significant performance improvements. Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), for example, has developed methods that automate the calibration of heavy-duty diesel truck emissions control systems using machine learning and algorithm-based optimization [16]. Their approach uses a physics-informed neural network machine learning model that learns from both data and the laws of physics, providing faster and more accurate results compared to manual methods.

This machine learning approach enables the system to learn optimal calibration settings and map calibration processes, allowing for full automation. Through simulations of active systems, researchers can fine-tune control parameters to lower emissions and rapidly identify optimal settings [16]. The result is a scalable, cost-effective pathway for calibration that reduces processes that traditionally took weeks to mere hours.

Comparative Analysis: Manual vs. Automated Calibration

The choice between manual and automated calibration involves trade-offs across multiple dimensions, including cost, time, accuracy, and flexibility. The table below provides a systematic comparison of these approaches based on current implementations across different fields.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Manual and Automated Calibration Approaches

| Factor | Manual Calibration | Automated Calibration |

|---|---|---|

| Time Requirements | Labor-intensive; can require 6+ weeks for complex systems [16] | Significant time reduction; can calibrate in as little as 2 hours for some applications [16] |

| Initial Investment | Lower initial cost; primarily requires skilled personnel and basic tools [15] | Higher upfront investment in software, machinery, and training [15] |

| Long-term Cost Efficiency | Higher ongoing labor costs and potential error-related expenses [15] | Lower long-term costs due to reduced labor and higher accuracy [15] |

| Accuracy & Consistency | Dependent on technician skill; susceptible to human error and inconsistencies [15] | Higher precision through algorithms and sensors; consistent performance [15] |

| Reproducibility | Challenging due to incomplete documentation of decision process [6] | Enhanced through detailed data logs and standardized processes [6] |

| Flexibility | High adaptability to unique scenarios; expert judgment applicable [15] | Increasingly adaptable through software updates; may struggle with novel situations [15] |

| Documentation | Manual recording prone to inconsistencies and omissions [6] | Automated, comprehensive data logging [15] |

Return on Investment Considerations

The economic case for automated calibration systems becomes compelling when considering total lifecycle costs rather than just initial investment. While automated systems require significant upfront investment in technology, the long-term savings in labor costs and increased productivity often offset these initial expenses [15]. The automation of repetitive tasks results in fewer errors and less downtime, ultimately leading to substantial cost savings, particularly for organizations with frequent calibration needs.

For smaller operations with limited budgets and less frequent calibration requirements, manual calibration may remain economically viable. However, for larger organizations or those operating in highly regulated environments where calibration frequency is high, automated systems typically provide superior ROI through consistent accuracy, comprehensive documentation, and reduced labor requirements [15].

Methodological Framework for Calibration

The PIPO Framework for Reporting Calibration

In response to inconsistent reporting practices in computational modeling, researchers have developed structured frameworks to standardize calibration documentation. The Purpose-Input-Process-Output (PIPO) framework provides a comprehensive 16-item checklist for reporting calibration in scientific studies [6]. This framework addresses four critical components of calibration:

Purpose: Documents the goal of calibration, including which parameters require estimation and why these specific parameters were selected.

Inputs: Specifies the data, model structure, and prior information used to inform the calibration process.

Process: Details the computational methods, algorithms, and implementation details employed during calibration.

Outputs: Describes the results, including point estimates, uncertainty quantification, and diagnostic assessments.

The development of such frameworks responds to systematic reviews showing that calibration reporting is often incomplete. A scoping review of infectious disease models found that only 4% of models reported all essential calibration items, with implementation code being the least reported element (available in only 20% of models) [6]. Standardized frameworks like PIPO address these deficiencies by providing clear guidelines for comprehensive reporting.

Methodology for Comparing Optimization Algorithms

In automated calibration, the selection of appropriate optimization algorithms is critical. Researchers have proposed standardized methodologies for comparing algorithm performance in auto-tuning applications [17]. This methodology includes four key steps:

Experimental Setup: Defining consistent testing conditions and performance metrics.

Tuning Budget: Establishing comparable computational resources for all algorithms.

Dealing with Stochasticity: Implementing statistical methods to account for random variations.

Quantifying Performance: Developing standardized metrics for comparing results.

This structured approach enables meaningful comparisons between different optimization strategies, addressing a significant challenge in auto-tuning research where variations in experimental design often preclude direct comparison between studies [17].

The workflow below illustrates the generalized calibration process, highlighting the critical stages where methodological choices significantly impact outcomes:

Figure 1: Generalized Calibration Workflow: This diagram illustrates the sequential stages of the calibration process, from defining objectives through documentation of results.

Domain-Specific Applications

Infectious Disease Modeling

In epidemiological modeling, calibration plays a crucial role in estimating key parameters that determine disease transmission dynamics. A scoping review of tuberculosis, HIV, and malaria models published between 2018-2024 revealed that parameters were calibrated primarily because they were unknown or ambiguous (40% of models) or because determining their value was relevant to the scientific question beyond being necessary to run the model (20% of models) [6].

The choice of calibration method in infectious disease modeling is significantly associated with model structure and stochasticity. Approximate Bayesian computation is more frequently used with individual-based models (IBMs), while Markov-Chain Monte Carlo methods are more common with compartmental models [6]. This specialization reflects how methodological choices must adapt to specific model characteristics and research questions.

Emissions Control Systems

In engineering applications, calibration is essential for optimizing system performance while ensuring regulatory compliance. The development of automated calibration for heavy-duty diesel truck emissions control systems demonstrates how machine learning can dramatically accelerate processes that traditionally required extensive manual effort [16]. By combining advanced modeling with automated optimization, researchers can calibrate selective catalytic reduction (SCR) systems in hours rather than weeks while improving system performance and ensuring compliance with evolving environmental standards.

Self-Driving Laboratories

The emergence of self-driving laboratories (SDLs) represents a frontier in automated calibration and optimization. These intelligent systems integrate experimental automation with data-driven decision-making, requiring robust calibration and anomaly detection methods to maintain operational safety and efficiency [18]. In these environments, calibration extends beyond parameter estimation to include real-time adjustment of experimental conditions based on continuous feedback, creating dynamic optimization loops that accelerate scientific discovery.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol for Machine Learning-Enhanced Calibration

Based on the successful implementation of automated calibration for emissions control systems [16], the following protocol provides a generalizable framework for developing machine learning-enhanced calibration systems:

System Modeling:

- Develop a physics-informed neural network model that incorporates domain knowledge

- Structure the model to learn from both empirical data and physical laws

- Define input-output relationships based on system physics

Data Collection:

- Gather historical calibration data, including parameter settings and performance outcomes

- Generate supplementary data through controlled simulations

- Validate data quality and relevance to target calibration tasks

Model Training:

- Implement training procedures that balance data-driven learning with physical constraints

- Establish convergence criteria based on prediction accuracy and physical plausibility

- Validate model performance against held-out test data

Optimization Implementation:

- Deploy algorithm-based optimization to identify parameter settings

- Define objective functions that balance multiple performance criteria

- Implement search algorithms appropriate for the parameter space

Validation and Verification:

- Test automated calibration against manual results for benchmark systems

- Verify performance across operational range

- Conduct robustness testing under varying conditions

This protocol can reduce calibration timelines from weeks to hours while improving performance, as demonstrated in emissions control applications where it consistently delivered faster calibration and improved conversion efficiency [16].

Reagents and Computational Tools

The implementation of advanced calibration methods requires both computational resources and methodological tools. The table below summarizes key resources referenced in the literature:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Calibration Implementation

| Resource | Type | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physics-Informed Neural Network | Algorithm | Combines data-driven learning with physical constraints for improved accuracy [16] | Emissions control system calibration |

| Archivist (Python Tool) | Software Tool | Processes metadata files using user-defined functions and combines outputs into unified file [19] | Metadata handling in simulation workflows |

| Approximate Bayesian Computation | Statistical Method | Parameter estimation for complex models where likelihood computation is challenging [6] | Individual-based models in epidemiology |

| Markov-Chain Monte Carlo | Statistical Method | Bayesian parameter estimation through posterior sampling [6] | Compartmental models in epidemiology |

| Auto-Tuning Optimization Algorithms | Computational Method | Efficiently searches parameter spaces to identify optimal configurations [17] | Performance optimization in computational systems |

Visualization of Automated Calibration Architecture

The architecture of automated calibration systems integrates multiple components, from data acquisition through optimization implementation. The following diagram illustrates the information flows and decision points in a machine learning-enhanced calibration system:

Figure 2: Automated Calibration System Architecture: This diagram illustrates the integrated components of a machine learning-enhanced calibration system, showing how data, machine learning, and optimization layers interact to produce calibrated models.

Future Directions and Challenges

The evolution of calibration techniques continues to address persistent challenges in computational modeling and system optimization. Key areas for future development include:

Reproducibility and Reporting Standards

Inconsistent reporting remains a significant challenge across multiple domains. In infectious disease modeling, comprehensive reporting of calibration practices is exception rather than rule, with only 4% of models reporting all essential items in the PIPO framework [6]. Developing domain-specific reporting standards and tools that facilitate automatic documentation represents a promising direction for addressing these deficiencies.

Integration of Physical Constraints with Data-Driven Methods

Hybrid approaches that combine physics-based modeling with machine learning, such as physics-informed neural networks, demonstrate significant potential for improving both the efficiency and accuracy of calibration [16]. These methods leverage the complementary strengths of first-principles understanding and data-driven pattern recognition, potentially overcoming limitations of purely empirical approaches.

Real-Time Calibration in Autonomous Systems

The emergence of self-driving laboratories and other autonomous systems creates demand for calibration methods that can operate in real-time with limited human supervision [18]. This requires developing robust anomaly detection systems and adaptive calibration protocols that can respond to changing conditions while maintaining operational safety and efficiency.

Methodological Standardization

The development of standardized methodologies for comparing optimization algorithms addresses a critical need in auto-tuning research [17]. Similar standardization efforts across other calibration domains would facilitate more meaningful comparisons between methods and accelerate methodological advances through clearer evaluation criteria.

As calibration methodologies continue to evolve, the integration of manual expertise with automated efficiency promises to enhance both the accuracy and accessibility of parameter estimation across scientific and engineering disciplines. The ongoing challenge remains balancing computational sophistication with practical implementation, ensuring that advanced calibration techniques deliver tangible improvements in model reliability and predictive performance.