Multi-Start Nonlinear Least Squares: Implementation Strategies for Robust Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to multi-start nonlinear least squares (NLS) implementation, specifically tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Multi-Start Nonlinear Least Squares: Implementation Strategies for Robust Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to multi-start nonlinear least squares (NLS) implementation, specifically tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers foundational principles of NLS and the critical need for multi-start approaches to avoid local minima in complex biological models. The content explores practical implementation methodologies using modern tools like R's gslnls package, details proven troubleshooting strategies for common convergence issues, and presents rigorous validation frameworks for comparing algorithm performance. By synthesizing current best practices with pharmaceutical applications such as drug-target interaction prediction and pharmacokinetic modeling, this guide aims to enhance the reliability and efficiency of parameter estimation in biomedical research.

Understanding Nonlinear Least Squares and the Multi-Start Imperative

The progression from linear to nonlinear regression represents a fundamental expansion in the toolkit for data analysis, enabling researchers to model complex, real-world phenomena with greater accuracy. While linear models assume a straight-line relationship between independent and dependent variables, nonlinear regression captures more intricate, curved relationships, providing a powerful framework for understanding sophisticated biological and chemical systems. This advancement is particularly crucial in drug development, where dose-response relationships, pharmacokinetic profiles, and biomarker interactions often follow complex patterns that cannot be adequately described by simple linear models [1].

The transition involves significant mathematical considerations, moving from closed-form solutions obtainable through ordinary least squares to iterative optimization algorithms required for estimating parameters in nonlinear models. This shift introduces complexities in model fitting, including sensitivity to initial parameter guesses and the potential to converge on local rather than global minima. Within this context, multi-start nonlinear least squares implementation provides a robust methodology for navigating complex parameter spaces, offering researchers greater confidence in their model solutions by initiating searches from multiple starting points [2].

Core Mathematical Formulations

Linear Regression Foundation

Linear regression establishes the fundamental framework for understanding relationship modeling between variables, employing a mathematically straightforward approach. The model assumes the form:

y = Xβ + ε

where y represents the vector of observed responses, X denotes the design matrix of predictor variables, β encompasses the parameter vector requiring estimation, and ε signifies the error term. The solution is obtained by minimizing the sum of squared residuals (SSR):

SSR = Σ(yi - ŷi)²

This minimization yields the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimator, β̂ = (XᵀX)⁻¹Xᵀy, a closed-form solution that provides a global optimum without requiring iterative methods. This direct computability makes linear regression highly accessible, though its assumption of linearity presents limitations for modeling complex biological processes in pharmaceutical research [1].

Nonlinear Regression Formulation

Nonlinear regression addresses the limitation of linearity by allowing models with parameters that enter the function nonlinearly:

y = f(X, β) + ε

Here, f represents a nonlinear function with respect to the parameter vector β. Unlike its linear counterpart, this framework accommodates sigmoidal curves, exponential decay, and asymptotic growth patterns frequently encountered in pharmacological and biological studies. The parameter estimation again involves minimizing the sum of squared residuals:

min Σ(yi - f(Xi, β))²

However, this minimization no longer provides a closed-form solution, necessitating iterative optimization algorithms such as Gauss-Newton, Levenberg-Marquardt, or trust-region methods to converge on parameter estimates [2]. This introduces computational complexity and sensitivity to initial starting values for parameters, which can lead to convergence to local minima rather than the global optimum—a challenge specifically addressed by multi-start techniques.

Multi-Start Nonlinear Least Squares Implementation

The multi-start approach enhances robustness against the local minima problem by initiating the optimization process from multiple, distinct starting points within the parameter space. This methodology increases the probability of locating the global minimum of the cost function. The implementation typically follows this workflow:

- Define the parameter space and bounds for estimation

- Generate or select multiple initial parameter vectors, often using quasi-random sequences like Sobol sequences or Latin Hypercube sampling for better space coverage

- Execute the chosen nonlinear least-squares algorithm (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt) from each starting point

- Compare the final sum of squared residuals across all runs

- Select the parameter estimates corresponding to the lowest achieved residual

The GSL multi-start nonlinear least-squares implementation offers specialized functionality for this purpose, particularly valuable for modeling complex biological systems where model parameters may have dependencies and interactions that create a complicated optimization landscape with multiple local minima [2].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Regression Formulations

| Feature | Linear Regression | Nonlinear Regression | Multi-Start Nonlinear Least Squares |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Form | y = Xβ + ε | y = f(X,β) + ε | y = f(X,β) + ε |

| Solution Method | Closed-form (OLS) | Iterative optimization | Multiple iterative optimizations |

| Parameter Estimate | β̂ = (XᵀX)⁻¹Xᵀy | Numerical approximation | Multiple numerical approximations with selection |

| Optima Guarantee | Global optimum | Possible local optima | Enhanced probability of global optimum |

| Computational Load | Low | Moderate to high | High (scales with number of starts) |

| Primary Applications | Linear relationships, trend analysis | Complex biological processes, saturation curves, periodic phenomena | Challenging optimization landscapes, critical parameter estimation |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Multi-Start Nonlinear Least Squares with GSL

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for implementing multi-start nonlinear least squares optimization using the GNU Scientific Library (GSL), particularly valuable for modeling complex pharmacological relationships.

Materials and Software Requirements

- GSL library (version ≥ 2.3) installed on the system

- R programming environment with

gslnlspackage installed - Dataset with observed response and predictor variables

Procedure

- Function Definition: Define the nonlinear model function in R, specifying the mathematical relationship between predictors and response. For exponential decay modeling: where A, lam, and b represent the parameters for estimation [2].

Parameter Initialization: Determine plausible ranges for initial parameter values based on domain knowledge or exploratory data analysis.

Algorithm Configuration: Set control parameters for the optimization algorithm, including the maximum number of iterations (default: 100) and convergence tolerance (default: 1.49e-08) [2].

Multi-Start Execution: Implement the multi-start optimization using the

gsl_nls()function with multiple initial parameter sets:Solution Validation: Compare the residual sum of squares across multiple starts and examine parameter convergence. The solution with the lowest residual sum of squares represents the best fit.

Results Interpretation: Extract parameter estimates, standard errors, and confidence intervals using the

summary()andconfint()functions in R.

Protocol 2: Comparative Evaluation of Linear vs. Nonlinear Models

This protocol outlines a systematic approach for comparing the performance of linear and nonlinear regression models, essential for determining the appropriate modeling framework for specific research applications.

Procedure

- Data Preparation: Split the dataset into training and validation subsets using an appropriate ratio (e.g., 70/30 or 80/20).

Model Specification:

- Formulate a linear model capturing the hypothesized linear relationship

- Develop one or more nonlinear models representing alternative mechanistic hypotheses

Model Fitting:

- Fit the linear model using ordinary least squares

- Fit nonlinear models using iterative optimization with multi-start implementation to mitigate local optima issues

Performance Assessment: Evaluate models using multiple metrics calculated on the validation set:

- R-squared (R²): Proportion of variance explained

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE): Average absolute difference between observed and predicted values

- Mean Squared Error (MSE): Average squared difference, giving higher weight to large errors

- Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE): Average percentage difference [3]

Statistical Comparison: Employ hypothesis testing or information criteria (AIC/BIC) to determine if the nonlinear model provides statistically significant improvement over the linear alternative.

Residual Analysis: Examine residual plots for patterns, which may indicate model misspecification in either formulation.

Visualization of Workflows

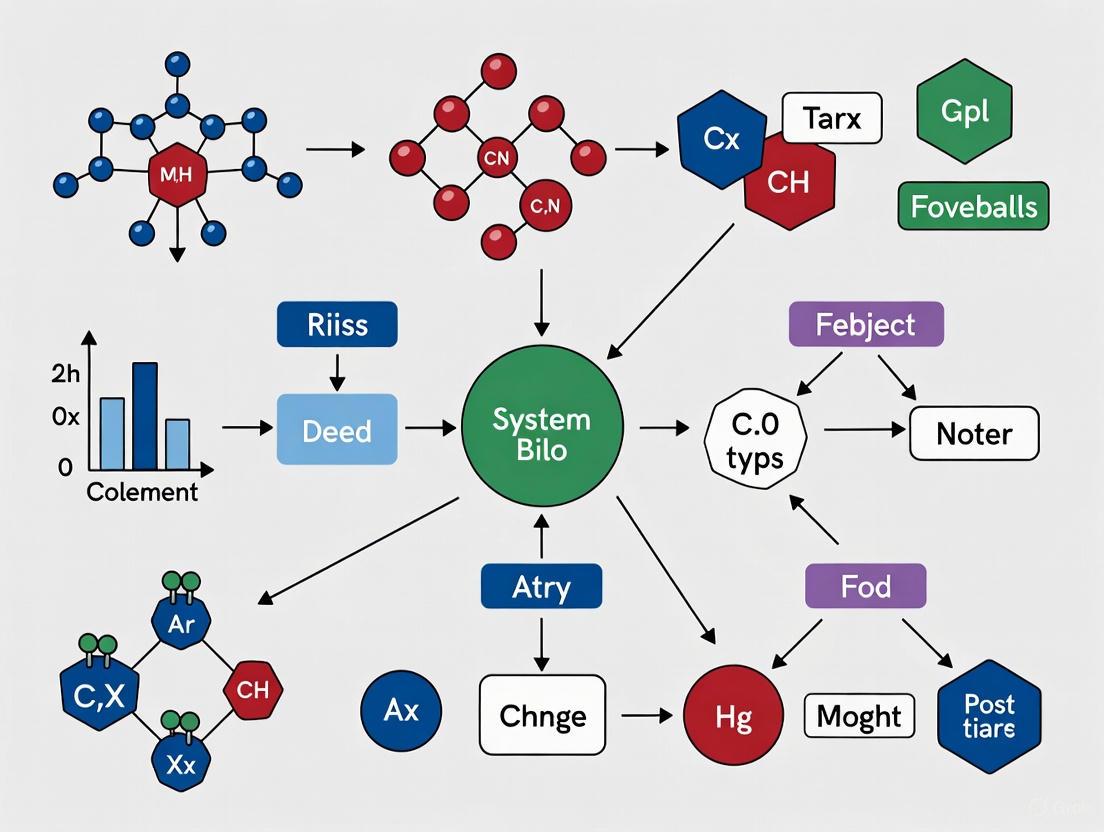

Nonlinear Least-Squares Optimization Workflow

Nonlinear Least-Squares Optimization Workflow

Multi-Start Algorithm Implementation

Multi-Start Algorithm Implementation

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Regression Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GNU Scientific Library (GSL) | Provides robust implementations of nonlinear least-squares algorithms (Levenberg-Marquardt, trust-region) | Core computational engine for parameter estimation in nonlinear models [2] |

| R gslnls Package | R bindings for GSL multi-start functionality with support for robust regression | Accessible interface for researchers familiar with R programming [2] |

| Color Contrast Analyzer | Validates sufficient visual contrast in diagrams per WCAG guidelines (4.5:1 minimum ratio) | Ensuring accessibility and readability of research visualizations [4] [5] |

| Decision Tree Algorithms | Non-linear modeling technique that automatically captures nonlinearities and interactions | Identifying hidden determinants with complex relationships to response variables [1] |

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) | Advanced non-linear regression capable of modeling complex phenotypic relationships | Predicting complex traits from genotypic data in pharmaceutical research [3] |

| SHAP Importance Analysis | Interprets complex model predictions and identifies feature contributions | Explaining non-linear model outputs and validating biological plausibility [3] |

Optimization is a fundamental process in biological research, essential for tasks ranging from model calibration and parameter estimation to metabolic engineering and drug target identification [6]. Biological systems are inherently complex, characterized by intrinsic variability, randomness, and uncertainty that are essential for their proper function [7]. This complexity gives rise to optimization landscapes filled with numerous local minima—points that appear optimal within a limited neighborhood but are suboptimal globally. Single-start optimization methods, particularly nonlinear least squares (NLLS) algorithms, initialize from a single parameter set and iteratively refine this estimate by moving downhill until no further improvement is possible [8] [9]. While computationally efficient for simple systems, this approach presents profound limitations when applied to complex biological problems where the error landscape exhibits multiple minima and parameter correlations are common [8] [10].

The constrained disorder principle (CDP) explains that biological systems operate through built-in variability constrained within dynamic borders [7]. This variability manifests as aleatoric uncertainty (from noise, missing data, and measurement error) and epistemic uncertainty (from lack of knowledge or data) [7]. When fitting models to biological data, these uncertainties create optimization landscapes where NLLS algorithms frequently converge to local minima, yielding parameter estimates that are mathematically valid but biologically irrelevant or suboptimal. The problem is particularly acute in systems with correlated parameters, where the optimization landscape contains narrow valleys and large plateaus that trap single-start algorithms [10]. As biological modeling increasingly informs critical applications like drug development and synthetic biology, overcoming the local minima challenge has become imperative for extracting meaningful insights from complex biological data.

Mathematical Foundations: Error Landscapes and Convergence Properties

Formulating Biological Optimization Problems

In biological optimization, we typically seek parameters $\theta = (\theta1, \theta2, ..., \theta_n)$ that minimize an objective function $f(\theta)$, often formulated as the sum of squared residuals between observed data and model predictions:

$$ \text{WSSR}(\theta) = \sum{i=1}^{N} \left( \frac{yi - \hat{y}i(\theta)}{\sigmai} \right)^2 $$

where $yi$ are observed values, $\hat{y}i(\theta)$ are model predictions, $\sigma_i$ are measurement uncertainties, and $N$ is the number of data points [9]. The weighted sum-of-squared residuals (WSSR) defines an n-dimensional error surface where elevation corresponds to error magnitude. Global minimization seeks the parameter set $\theta^*$ that produces the lowest WSSR across the entire parameter space [6].

Table 1: Characteristics of Error Landscapes in Biological Systems

| Landscape Feature | Impact on Optimization | Biological Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple local minima | High risk of convergence to suboptimal solutions | Heterogeneity in biological processes [7] |

| Correlated parameters | Elongated valleys in error landscape | Compensatory mechanisms in biological networks [8] |

| Narrow attraction basins | Difficulty finding global minimum | Limited data resolution and high noise [10] |

| High-dimensionality | Exponential growth of search space | Complex interactions in biological systems [11] |

Why Single-Start Methods Fail

Single-start methods like Gauss-Newton and Levenberg-Marquardt begin with an initial guess $\theta0$ and generate a sequence $\theta1, \theta2, ..., \thetak$ that converges to a local minimum [9] [10]. The fundamental limitation is that these algorithms cannot escape the attraction basin of their starting point. In biological systems, common scenarios leading to failure include:

Parameter correlation: When model parameters are highly correlated, the error landscape contains elongated valleys with similar WSSR values along the valley floor. Single-start methods may converge to any point along this valley, introducing user bias through the initial parameter selection [8].

Inadequate starting points: Without a priori knowledge of parameter values, researchers may select initial guesses too distant from the global minimum, causing convergence to physically implausible solutions or parameter evaporation (divergence to infinity) [10].

Rugged error landscapes: Biological models with many parameters and complex dynamics produce error surfaces with numerous local minima of varying depths. Single-start methods inevitably become trapped in the nearest local minimum [12].

Multi-Start Optimization Frameworks for Biological Systems

Hybrid Genetic Algorithm-NLLS Approaches

The MENOTR (Multi-start Evolutionary Nonlinear OpTimizeR) framework addresses local minima challenges by combining genetic algorithms (GA) with NLLS methods [8]. Genetic algorithms employ population-based stochastic search inspired by natural selection, maintaining diversity through mechanisms like mutation, crossover, and selection. This approach enables broad exploration of the parameter space without becoming trapped in local minima. MENOTR leverages GA to identify promising regions of the parameter space, then applies NLLS for precise local refinement, maximizing the strengths of both approaches while minimizing their inherent drawbacks [8].

Table 2: Comparison of Optimization Algorithms for Biological Systems

| Algorithm | Mechanism | Local Minima Resistance | Computational Cost | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-start NLLS | Gradient-based local search | Low | Low | Well-behaved systems with good initial estimates |

| Genetic Algorithms | Population-based stochastic search | High | High | Complex landscapes without gradient information |

| Hybrid GA-NLLS (MENOTR) | Global exploration with local refinement | High | Medium | Biological systems with correlated parameters [8] |

| Differential Evolution | Vector-based population evolution | High | High | Noisy biological data with many parameters [12] |

| Deep Active Optimization | Neural surrogate with tree search | High | Medium-High | High-dimensional biological spaces [11] |

Advanced Escape Strategies

Recent research has developed specialized techniques to help optimization algorithms escape local minima once detected:

Local Minima Escape Procedure (LMEP): This approach enhances differential evolution by detecting when the population has converged to a local minimum and applying a "parameter shake-up" to escape it [12]. The method monitors population diversity and, when trapped, reinitializes portions of the population while preserving the best solutions.

Deep Active Optimization with Neural-Surrogate-Guided Tree Exploration (DANTE): This method uses deep neural networks as surrogate models of the objective function, combined with tree search exploration guided by a data-driven upper confidence bound [11]. The approach includes conditional selection and local backpropagation mechanisms that help escape local optima in high-dimensional problems.

Human network strategies: Studies of synchronized human networks reveal biological inspiration for escape mechanisms, including temporary coupling strength reduction, tempo adjustment, and oscillation death [13]. These strategies parallel computational techniques like adaptive parameter control and temporary acceptance of suboptimal moves.

Experimental Protocols for Biological Optimization

Protocol: Multi-Start Parameter Estimation for Biochemical Kinetics

This protocol outlines the procedure for implementing multi-start optimization to estimate parameters in biochemical kinetic models, using the MENOTR framework or similar hybrid approaches [8].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

- Software Environment: R, Python, or MATLAB with optimization toolboxes

- Experimental Dataset: Time-course measurements of biochemical species

- Mathematical Model: System of ordinary differential equations representing reaction kinetics

- Computational Resources: Multi-core processor or computing cluster for parallelization

Procedure

- Model Formulation: Derive a hypothesis-based mathematical model representing the biochemical system, typically as a system of ordinary differential equations: $$ \frac{dSi}{dt} = fi(S, \theta, t) $$ where $S_i$ are biochemical species concentrations and $\theta$ are kinetic parameters to be estimated [9].

Objective Function Definition: Implement the WSSR function comparing experimental data with model simulations: $$ \text{WSSR}(\theta) = \sum{i=1}^{N} \sum{j=1}^{M} \left( \frac{S{ij}^{\text{exp}} - S{ij}^{\text{model}}(\theta)}{\sigma{ij}} \right)^2 $$ where $S{ij}^{\text{exp}}$ are experimental measurements, $S{ij}^{\text{model}}(\theta)$ are model predictions, and $\sigma{ij}$ are measurement uncertainties [9].

Parameter Space Definition: Establish biologically plausible bounds for each parameter based on literature values or preliminary experiments.

Initial Population Generation: Create a diverse population of parameter vectors using Latin Hypercube Sampling or similar space-filling designs to ensure comprehensive coverage of the parameter space.

Genetic Algorithm Phase: Execute the genetic algorithm with appropriate settings:

- Population size: 50-500 individuals

- Selection: Tournament or fitness-proportional selection

- Crossover: Blend or simulated binary crossover

- Mutation: Polynomial or Gaussian mutation

- Termination: Maximum generations or fitness plateau

Local Refinement Phase: Apply NLLS optimization to the best solutions from the genetic algorithm phase using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm for robust convergence [10].

Solution Validation: Assess solution quality through goodness-of-fit metrics, parameter identifiability analysis, and biological plausibility of the estimated parameters.

Protocol: Handling Noisy Biological Data with Uncertainty Quantification

Biological measurements inherently contain significant noise and variability that must be accounted for during optimization [7]. This protocol extends the basic multi-start approach to handle uncertain biological data.

Procedure

- Uncertainty Characterization: Quantify measurement errors through experimental replicates or instrument specifications. Classify uncertainties as aleatoric (irreducible noise) or epistemic (reducible through better models or data) [7].

Bayesian Framework Implementation: Incorporate uncertainty through Bayesian inference, seeking the posterior parameter distribution: $$ P(\theta|D) \propto P(D|\theta) \cdot P(\theta) $$ where $P(D|\theta)$ is the likelihood and $P(\theta)$ is the prior distribution.

Bootstrap Resampling: Apply bootstrap methods to estimate parameter confidence intervals by repeatedly fitting the model to resampled datasets [9].

Model Discrepancy Modeling: Include explicit terms for model inadequacy when the mathematical model cannot perfectly represent the biological system, even with optimal parameters [7].

Applications in Biological Research and Drug Development

Case Study: Drug Target Identification and Combination Therapy

Network-based systems biology approaches use optimization to identify effective drug combinations by exploiting high-throughput data [14]. Researchers constructed a molecular interaction network integrating protein interactions, protein-DNA interactions, and signaling pathways. A novel model was developed to detect subnetworks affected by drugs, with a scoring function evaluating overall drug effect considering both efficacy and side-effects. Multi-start optimization was essential for navigating the complex search space of possible drug combinations, successfully identifying Metformin and Rosiglitazone as an effective combination for Type 2 Diabetes—later validated as the marketed drug Avandamet [14].

Case Study: Metabolic Engineering and Strain Design

Optimization frameworks enable metabolic engineers to steer cellular metabolism toward desired products [15]. Constraint-based methods like Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) use optimization to predict metabolic flux distributions under steady-state assumptions. Multi-start approaches are particularly valuable for genome-scale metabolic models where alternative optimal solutions exist. Computational strain design procedures relying on mathematical optimization frameworks benefit from multi-start implementation to identify and quantify genetic interventions while minimizing cellular counteractions [15].

Case Study: Protein Folding and Molecular Dynamics

The protein folding problem represents a fundamental challenge where optimization techniques bridge biology, chemistry, and computation [14]. Energy minimization approaches seek the tertiary structure corresponding to the global minimum of the free energy landscape. This landscape typically contains numerous local minima that trap conventional optimization methods. Multi-start approaches and evolutionary algorithms have demonstrated superior performance in locating native protein conformations by more comprehensively exploring the conformational space.

Implementation Guidelines and Best Practices

Software and Computational Considerations

Implementing multi-start optimization for biological systems requires both specialized algorithms and computational resources:

Software Tools

- R Packages:

gslnlsprovides multistart nonlinear least squares implementation with the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm [10] - Python Libraries: SciPy optimization suite, DEAP for evolutionary algorithms

- Specialized Tools: MENOTR for hybrid GA-NLLS optimization [8]

- Commercial Software: Scientist, Origin, KinTek Explorer with multi-start capabilities

Computational Strategies

- Parallelization: Distribute individual starts across multiple cores or nodes

- Adaptive Termination: Implement convergence criteria based on both objective function improvement and parameter stability

- Memory Management: Cache simulation results to avoid recomputing identical parameter sets

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Parameter Evaporation: When parameters diverge to infinity during optimization, implement parameter constraints or use transformed parameters (e.g., logarithms of rate constants) to maintain biological plausibility [9] [10].

Identifiability Problems: When parameters are non-identifiable from available data, apply regularization techniques or redesign experiments to provide more informative data.

Excessive Computation Time: For computationally expensive biological models, employ surrogate modeling or approximate approaches during the global search phase.

The local minima challenge represents a fundamental limitation of single-start optimization methods in complex biological systems. The inherent variability, uncertainty, and high-dimensionality of biological models create error landscapes where traditional NLLS algorithms frequently converge to suboptimal solutions. Multi-start approaches, particularly hybrid frameworks combining global search with local refinement, provide a robust solution to this challenge by more comprehensively exploring parameter spaces and dramatically reducing dependence on initial parameter guesses. As biological research increasingly relies on computational models to understand complex phenomena and develop therapeutic interventions, multi-start optimization will continue to grow in importance, enabling researchers to extract meaningful biological insights from complex, noisy data while avoiding the pitfalls of local minima.

Global optimization is a critical challenge across numerous scientific and industrial domains, particularly in fields like drug discovery where model parameters must be estimated from experimental data. Multi-start optimization has emerged as a fundamental strategy for addressing non-convex problems containing multiple local minima. This metaheuristic approach iteratively applies local search algorithms from multiple starting points within the feasible domain, significantly increasing the probability of locating the global optimum [16].

The importance of multi-start methods has grown substantially with the rise of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and data-intensive sciences, where optimization forms the backbone of model training and parameter estimation [16]. In pharmaceutical research, particularly in drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction and nonlinear pharmacokinetic modeling, these methods enable researchers to escape suboptimal local solutions and converge toward biologically relevant parameter estimates [17] [10].

This article presents fundamental principles, protocols, and applications of multi-start optimization, with specific emphasis on nonlinear least squares problems in drug development contexts. We establish theoretical foundations, detail practical implementation methodologies, and provide validated experimental protocols for researchers working at the intersection of computational biology and pharmaceutical sciences.

Theoretical Foundations

Problem Formulation and Definitions

The global optimization problem for box-constrained minimization can be formally stated as:

where S is a closed hyper-rectangular region of R^n, and the vector x = (x₁, ..., xₙ) represents the optimization variables. A vector x* is the global minimum if f(x*) ≤ f(x) for all x ∈ S [16]. In the context of nonlinear least squares, the objective function f(x) typically takes the form:

where yᵢ are observed data points, M(tᵢ, x) is the model prediction at condition tᵢ with parameters x, and the sum extends over all observations.

Local minima present significant challenges in pharmaceutical modeling. As observed in practical applications, "parameter evaporation" occurs when optimization algorithms diverge toward infinity when poorly initialized [10]. This behavior is particularly problematic in drug discovery applications where model parameters often have physical interpretations and biologically implausible values can invalidate scientific conclusions.

The Curse of Scale-Freeness

Theoretical analysis reveals fundamental limitations of basic multi-start approaches. For Random Multi-Start (RMS) methods, where empirical objective values (EOVs) are treated as independent and identically distributed random variables, the expected relative gap between the best-found solution and the true supremum exhibits "scale-freeness" [18].

This phenomenon manifests as a power-law behavior where the number of additional trials required to halve the relative error increases asymptotically in proportion to the number of trials already completed. This creates a Zeno's paradox-like situation figuratively described as "reaching for the goal makes it slip away" [18]. Mathematically, this is expressed through the expected relative gap:

where Zₙ = max(X₁, X₂, ..., Xₙ) represents the best EOV after n trials, and x* is the supremum of EOVs [18]. This theoretical framework explains why naive multi-start methods face diminishing returns and require strategic enhancements for practical effectiveness in large-scale optimization problems.

Methodologies and Algorithms

Basic Multi-Start Framework

The conventional multi-start method operates through a straightforward iterative process:

- Generate a candidate point within the feasible domain S

- Apply a local optimization algorithm from the candidate point

- Record the discovered local minimum

- Repeat until computational budget is exhausted

- Select the best-found solution across all trials

This approach classified as a stochastic global optimization technique, serves as the foundation for more sophisticated variants [16]. In computational practice, multi-start methods are particularly valuable for non-convex problems where the objective function contains multiple local optima, as they systematically increase the likelihood of locating the global optimum [16].

Advanced Sampling Strategies

The distribution of starting points significantly impacts multi-start performance. Basic random sampling, while simple to implement, often proves inefficient in high-dimensional spaces. Advanced alternatives include:

- Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS): Divides each variable's range into equal intervals and selects points ensuring each interval is sampled exactly once, providing superior space-filling properties compared to random sampling [16].

- Adaptive LHS: Modifies traditional LHS to maintain constant search space coverage rates even as dimensionality increases, addressing the exponential decline in coverage that plagues conventional methods [16].

- Quasi-random Sequences: Utilizes low-discrepancy sequences (Halton, Sobol) for more uniform sampling than random points [16].

Table 1: Sampling Method Comparison for Multi-Start Optimization

| Method | Space Coverage | Implementation Complexity | Scalability to High Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Sampling | Variable, often poor | Low | Poor |

| Latin Hypercube Sampling | Excellent | Medium | Good |

| Adaptive LHS | Controlled rate | High | Excellent |

| Quasi-random Sequences | Good | Medium | Good |

Selective Multi-Start with Interval Arithmetic

Recent advances propose integrating Interval Arithmetic (IA) with LHS to create selective multi-start frameworks. This approach prioritizes sampling points using hypercubes generated through LHS and their corresponding interval enclosures, guiding optimization toward regions more likely to contain the global minimum [16].

The interval methodology provides two significant advantages: (1) enabling discarding of regions that cannot contain the global minimum, thereby reducing the search space; and (2) verifying a minimum as global—a capability not available using standard real arithmetic [16]. This represents a substantial theoretical and practical advancement over conventional multi-start methods, which assume uniform sampling without quantifying spatial coverage.

Experimental Protocols

Multi-Start Nonlinear Least Squares Protocol

The following protocol details the implementation of multi-start nonlinear least squares fitting for parameter estimation in pharmacological models, based on established implementations in R package gslnls [10].

Materials and Software Requirements

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Start Optimization

| Item | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Environment | Computational platform for optimization | Version 4.0 or higher |

gslnls R package |

Implements multi-start NLS with LHS | Available from CRAN |

| Benchmark datasets | Validation and performance assessment | NIST StRD, Hobbs' weed infestation |

| Local optimization algorithm | Convergence from individual starting points | Levenberg-Marquardt recommended |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Problem Formulation:

- Define the nonlinear model

y ~ M(t, θ)where θ represents model parameters - Specify feasible parameter ranges based on scientific knowledge:

θᵢ ∈ [aᵢ, bᵢ]

- Define the nonlinear model

Algorithm Configuration:

- Select the multistart algorithm in

gsl_nls()with undefined starting ranges: - Alternatively, specify fixed parameter ranges when prior knowledge exists:

- Select the multistart algorithm in

Execution and Monitoring:

- Execute the algorithm with appropriate computational resources

- Monitor convergence behavior across restarts

- Track the best-found solution across all starting points

Validation:

- Verify solution quality against known test problems

- Assess parameter identifiability through sensitivity analysis

- Confirm biological plausibility of parameter estimates

Drug-Target Interaction Prediction Protocol

The following protocol adapts the multi-start framework for predicting drug-target interactions (DTI) using regularized least squares with nonlinear kernel fusion (RLS-KF), based on established methodologies in pharmaceutical informatics [17].

Materials and Data Requirements

- Data Sources: KEGG BRITE, BRENDA, SuperTarget, and DrugBank databases

- Similarity Matrices: Chemical structure similarity (Sd) and target sequence similarity (St)

- Interaction Data: Known drug-target interactions from benchmark datasets (enzymes, ion channels, GPCRs, nuclear receptors)

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Preparation:

- Compile drug-target interaction adjacency matrix Y, where Yᵢⱼ = 1 if drug i interacts with target j

- Calculate Gaussian Interaction Profile (GIP) kernels using the equation: where Y_tᵢ is the interaction profile for target i, and σ is the kernel bandwidth [17]

- Compute chemical structure similarity matrices using SIMCOMP tool [17]

Kernel Fusion:

- Apply nonlinear kernel fusion technique to combine multiple similarity measures

- Derive shared and complementary information from various kernel matrices

Model Training:

- Implement RLS-KF algorithm to predict unknown interactions

- Employ 10-fold cross-validation for performance assessment

- Calculate area under precision-recall curve (AUPR) as primary metric

Validation:

- Verify top-ranked interaction predictions using experimental data from literature

- Confirm findings using bioassay results in PubChem BioAssay database

- Compare with previous studies for consistency assessment

Applications in Drug Discovery

Drug-Target Interaction Prediction

Multi-start optimization plays a crucial role in predicting drug-target interactions, a fundamental task in drug discovery. The RLS-KF algorithm achieves state-of-the-art performance with AUPR values of 0.915, 0.925, 0.853, and 0.909 for enzymes, ion channels, GPCRs, and nuclear receptors, respectively, based on 10-fold cross-validation [17]. These results demonstrate significant improvement over previous methods, with performance further enhanced by using recalculated kernel matrices, particularly for small nuclear receptor datasets (AUPR = 0.945) [17].

The multi-start framework enables robust parameter estimation in kernel-based methods, which have emerged as the most popular approach for DTI prediction due to their ability to handle complex similarity measures and interaction networks [17]. This application exemplifies how global optimization techniques directly contribute to pharmaceutical development by identifying novel drug targets and facilitating drug repositioning.

Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Modeling

Nonlinear least squares problems frequently arise in pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling, where multi-start methods prevent convergence to biologically implausible local minima. The Hobbs' weed infestation model exemplifies a challenging nonlinear regression problem where standard Gauss-Newton algorithms often diverge with poor initialization, while multi-start approaches with Levenberg-Marquardt stabilization successfully converge to meaningful parameter estimates [10].

Table 3: Performance Comparison for Benchmark Problems

| Problem | Parameters | Standard NLS Success Rate | Multi-Start Success Rate | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hobbs' weed model | 3 | ~40% | ~98% | Parameter evaporation |

| NIST Gauss1 | 8 | ~25% | ~95% | Multiple local minima |

| DTI prediction | Variable | ~60% | ~92% | High-dimensional kernels |

Multi-start optimization provides a fundamental framework for addressing complex global optimization challenges in pharmaceutical research and drug development. The principles outlined in this article—from basic multi-start methods to advanced selective sampling with interval arithmetic—establish a comprehensive foundation for researchers implementing these techniques in practical applications.

The experimental protocols for nonlinear least squares and drug-target interaction prediction offer validated methodologies that can be directly implemented or adapted to specific research contexts. As optimization continues to form the backbone of AI and machine learning applications in drug discovery, mastering these multi-start fundamentals becomes increasingly essential for researchers seeking to extract meaningful insights from complex biological data.

The integration of sophisticated sampling strategies, local optimizer selection, and validation protocols creates a robust approach for overcoming the "curse of scale-freeness" that limits basic multi-start methods. Through systematic application of these principles, researchers can significantly enhance their capability to identify globally optimal solutions in high-dimensional parameter spaces characteristic of modern pharmacological problems.

Application Notes

The integration of advanced computational methods is transforming drug discovery, with Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) Prediction and Pharmacokinetic (PK) Modeling emerging as two pivotal applications. These methodologies are increasingly supported by sophisticated optimization frameworks, including multi-start nonlinear least squares algorithms, which enhance model robustness and predictive accuracy by effectively navigating complex parameter landscapes and avoiding local minima [19].

Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) Prediction

DTI prediction is a cornerstone of in-silico drug discovery, aimed at identifying potential interactions between chemical compounds and biological targets. The field has evolved from traditional ligand-based and structure-based methods to modern deep learning approaches that leverage large-scale biological and chemical data [20].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of Advanced DTI Prediction Models

| Model Name | Core Methodology | Key Advantage | Reported AUROC | Reported AUPR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DTIAM [21] | Self-supervised pre-training of drug and target representations | Unified prediction of interaction, affinity, and mechanism of action (MoA) | >0.96 (est. from text) | 0.901 [22] |

| EviDTI [23] | Evidential Deep Learning (EDL) on multi-dimensional drug/target features | Quantifies prediction uncertainty, preventing overconfidence | 0.8669 (Cold-start) | - |

| MVPA-DTI [22] | Heterogeneous network with multiview path aggregation | Integrates 3D drug structure and protein sequence views from LLMs (Prot-T5) | 0.966 | 0.901 |

| Hetero-KGraphDTI [24] | Graph Neural Networks with knowledge-based regularization | Incorporates biological knowledge from ontologies (e.g., Gene Ontology) | 0.98 (Avg.) | 0.89 (Avg.) |

A major challenge in DTI prediction is the cold-start problem, which refers to predicting interactions for novel drugs or targets absent from training data. Frameworks like DTIAM address this through self-supervised pre-training on large, unlabeled datasets to learn robust foundational representations of molecular graphs and protein sequences, demonstrating substantial performance improvement in cold-start scenarios [21]. Another significant challenge is model overconfidence, where models assign high probability scores to incorrect predictions. EviDTI tackles this by employing evidential deep learning to provide calibrated uncertainty estimates for each prediction, allowing researchers to prioritize high-confidence candidates for experimental validation [23].

Pharmacokinetic (PK) Modeling

PK modeling predicts the time course of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) within the body. Two dominant computational approaches are Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) and Population PK (PopPK) modeling.

Table 2: Regulatory Application of PBPK Models (2020-2024)

| Application Domain | Frequency (%) | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Drug-Drug Interactions (DDI) | 81.9% | Predicting exposure changes when drugs are co-administered [25] [26]. |

| Organ Impairment (Hepatic/Renal) | 7.0% | Dose recommendation for patients with impaired organ function [25] [26]. |

| Pediatric Dosing | 2.6% | Predicting PK and optimizing doses for pediatric populations [25] [26]. |

| Food-Effect Evaluation | ~1% | Assessing the impact of food on drug absorption [25] [26]. |

PBPK modeling is a mechanistic approach that constructs a mathematical representation of the human body as a network of physiological compartments (e.g., liver, kidney). By integrating system-specific parameters (e.g., organ sizes, blood flow rates) with drug-specific properties (e.g., lipophilicity, plasma protein binding), it can quantitatively predict drug concentration-time profiles in plasma and specific tissues, offering superior extrapolation capabilities compared to traditional compartmental models [25] [26]. Between 2020 and 2024, 26.5% of all new drugs approved by the FDA included PBPK models in their submissions, with the highest adoption in oncology (42%) [25] [26].

PopPK analysis uses non-linear mixed-effects (NLME) models to identify and quantify sources of inter-individual variability in drug exposure (e.g., due to weight, genetics, organ function) [19]. A key challenge has been the manual, time-intensive process of structural model development. Recent automation platforms, such as pyDarwin, leverage machine learning to efficiently search vast model spaces, identifying robust PopPK model structures in a fraction of the time required by manual methods [19]. The multi-start optimization inherent in these algorithms is crucial for thoroughly exploring the parameter space and converging on the global, rather than a local, optimum.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Predicting DTIs with a Self-Supervised Unified Framework (DTIAM)

Objective: To predict novel drug-target interactions (DTIs), binding affinities (DTA), and mechanisms of action (MoA: activation/inhibition) using the DTIAM framework [21].

Workflow Overview:

Materials & Reagents:

- Drug & Target Data: SMILES strings of drug compounds and amino acid sequences of target proteins.

- Interaction Data: Benchmark datasets like Yamanishi_08 or Hetionet, containing known drug-target pairs.

- Computational Resources: High-performance computing (HPC) cluster or GPU-equipped workstation.

- Software: DTIAM implementation (e.g., Python, PyTorch/TensorFlow).

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Standardize drug representations by converting SMILES strings into molecular graphs, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges.

- Tokenize protein sequences into their constituent amino acids or common k-mers.

- Self-Supervised Pre-training:

- Drug Module: Train the drug encoder using the multi-task self-supervised strategy on a large, unlabeled molecular dataset (e.g., from PubChem).

- Target Module: Pre-train the protein encoder on a large, unlabeled protein sequence database (e.g., UniRef) using a masked language modeling objective.

- Downstream Task Fine-tuning:

- Combine the pre-trained drug and target encoders.

- Feed the learned drug and target representations into a downstream prediction module (e.g., a neural network or an AutoML framework) for the specific task (DTI, DTA, or MoA classification).

- Train the entire model on the labeled benchmark dataset. Use a warm start, drug cold start, and target cold start validation setting to rigorously evaluate performance [21].

- Validation:

- Use standard metrics such as Area Under the ROC Curve (AUROC), Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR), Accuracy, and F1-score to assess model performance.

- For cold start scenarios, ensure drugs or targets in the test set are not present in the training set.

Protocol 2: Implementing an Automated PopPK Workflow with pyDarwin

Objective: To automatically develop a population pharmacokinetic (PopPK) model structure for a drug with extravascular administration (e.g., oral, subcutaneous) using the pyDarwin optimization framework [19].

Workflow Overview:

Materials & Reagents:

- Clinical Data: Drug concentration-time data from Phase 1 clinical trials, including patient demographic information (e.g., weight, age, sex).

- Software: pyDarwin library, NONMEM software for NLME modeling, and a suitable scripting environment (e.g., Python).

- Computational Resources: A 40-CPU, 40 GB RAM computing environment is recommended for efficient processing [19].

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Curate the PK dataset. Ensure data includes subject ID, time of dose, dosing regimen, concentration measurements, and relevant covariates.

- Format the dataset according to the requirements of the NLME software (e.g., NONMEM).

- Configure Automated Search:

- Define a generic model search space for extravascular drugs. This space should include options for 1- and 2-compartment models, various absorption models (e.g., first-order, zero-order, transit compartments), and different residual error models.

- Implement a penalty function within pyDarwin that combines the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to discourage over-parameterization and a term to penalize biologically implausible parameter estimates (e.g., extremely high standard errors, unrealistic volumes of distribution) [19].

- Execute Model Search:

- Initiate the pyDarwin optimization process, which uses a Bayesian optimizer with a random forest surrogate model combined with an exhaustive local search.

- The algorithm will iteratively generate candidate model structures, evaluate them using NONMEM, compute the penalty score, and use this information to propose the next set of candidate models.

- Model Selection & Validation:

- Upon convergence, select the model structure with the optimal penalty score.

- Perform standard model diagnostics (e.g., visual predictive checks, goodness-of-fit plots) to validate the final selected model.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Protocols

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example Sources / Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Language Model | Encodes biophysical and functional features from raw amino acid sequences. | Prot-T5 [22], ProtTrans [23], ProtBERT [20] |

| Molecular Pre-training Model | Learns meaningful representations of molecular structure from graphs or SMILES. | MG-BERT [23], MolBERT [20], ChemBERTa [20] |

| PBPK Simulation Platform | Mechanistic, physiology-based simulation of drug PK in virtual populations. | Simcyp Simulator [25] [26], GastroPlus [25] |

| NLME Modeling Software | Gold-standard software for developing and fitting PopPK models. | NONMEM [19], Monolix, R (nlmixr) |

| Optimization Framework | Automates the search for optimal model structures and parameters. | pyDarwin [19] |

| Curated Interaction Database | Provides ground-truth data for training and validating DTI models. | DrugBank [23], Davis [23], KIBA [23] |

The accurate quantification of error structures is a foundational step in pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling and bioanalytical method development. Nonlinear least squares (NLS) fitting is the standard computational method for parameter optimization in these domains [27] [28]. However, a well-understood limitation of classical NLS algorithms is their dependence on user-supplied initial parameter guesses, which can lead to convergence on local—rather than global—minima, especially in models with correlated parameters [29]. This dependency introduces potential user bias and reduces the reliability of the resultant error structure models, such as Assay Error Equations (AEEs), which are critical for weighting data in PK modeling [30].

Multi-start nonlinear least squares (MSNLS) algorithms directly address this challenge by initiating local optimization routines from numerous starting points within the parameter space, systematically exploring it to identify the global optimum with higher probability [31] [32]. This Application Note frames the discussion of error structures and model requirements within the context of implementing MSNLS, providing detailed protocols for robust error model establishment.

Characterizing Error Structures in Bioanalytical Data

The variance of experimental measurements is rarely constant across their range. Most bioanalytical methods, including Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), exhibit heteroscedasticity, where the standard deviation (SD) of the measurement varies with the analyte concentration [30]. Correct characterization of this relationship is not merely a statistical formality; it is essential for proper data weighting in subsequent PK/PD modeling, where the optimal weight is inversely proportional to the variance (1/σ²) [30] [27].

Common Error Models and Their Mathematical Forms

Error models describe the functional relationship between the measured concentration (C) and its standard deviation (SD) or variance (Var). The choice of model is an underlying critical assumption that impacts all downstream analyses.

Table 1: Common Error Structure Models in Bioanalysis

| Model Name | Functional Form (SD vs. Concentration, C) | Typical Application | Key Assumption |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant SD (Homoscedastic) | SD = a | Methods where analytical noise is independent of concentration. Rare in modern LC-MS/MS [30]. | Additive Gaussian error dominates. |

| Constant CV (Proportional Error) | SD = a · C | Often an initial approximation for chromatographic assays. | Relative error is constant across the range. |

| Linear Error Model | SD = a + b · C | Recommended for characterizing LC-MS/MS method precision profiles [30]. | Error has both fixed (additive) and concentration-dependent (proportional) components. |

| Power Model | SD = a · C^b | A flexible, empirical model for complex heteroscedasticity. | The power b dictates the shape of the variance function. |

| Polynomial Model | SD = a + b·C + c·C² | Historically used for automated clinical analyzers [30]. | Error structure can be captured by a low-order polynomial. |

Protocol 1: Establishing an Assay Error Equation (AEE) for an LC-MS/MS Method

This protocol details the experimental and computational workflow for developing a robust AEE, integrating the MSNLS approach for robust fitting.

Objective: To determine the precise relationship between the measured concentration and its standard deviation for a given bioanalytical method (e.g., carbamazepine assay via LC-MS/MS) [30].

Materials & Reagents:

- Drug analyte and isotopically labeled internal standard (IS) [30].

- LC-MS grade solvents (acetonitrile, methanol, water) [30].

- Drug-free human serum matrix.

- Validated LC-MS/MS system with electrospray ionization (ESI) and multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) capability [30] [33].

- Statistical software with NLS and MSNLS capabilities (e.g., R with the

gslnlspackage [2] [32]).

Experimental Workflow:

Figure 1: Assay Error Equation (AEE) Development Workflow. The process from sample preparation to validated error model, highlighting the integration of MSNLS optimization.

Procedure:

Sample Preparation: Prepare calibration standards and quality control (QC) samples by spiking analyte into the appropriate matrix (e.g., human serum) across the entire validated concentration range. Include a minimum of 6-20 different concentration levels. For each level, prepare a sufficient number of independent replicates (n ≥ 6, ideally 24) from independently spiked specimens to reliably estimate the SD. Repeat this across multiple independent analytical runs (e.g., 3 experiments) to capture inter-day variance [30].

Instrumental Analysis: Analyze all samples using the fully validated LC-MS/MS method. The method should detail chromatographic conditions, MRM transitions (e.g., m/z 148.19 > 74.02 for 4-hydroxyisoleucine [33]), and data acquisition parameters.

Data Compilation: For each concentration level i, calculate the mean measured concentration (C̄_i) and the standard deviation (SD_i) from all replicate measurements across all experimental runs.

Preliminary Model Selection & Fitting: Plot SDi versus *C̄i* (precision profile). Based on the visual pattern and field knowledge (e.g., linear models are often suitable for LC-MS/MS [30]), select a candidate error model from Table 1. Perform an initial NLS fit using a standard algorithm (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt) to obtain preliminary parameter estimates and the residual sum of squares.

MSNLS Refinement: Implement a multi-start routine to verify the global optimality of the fit and avoid local minima.

- Using

gslnlsin R: Utilize thegsl_nls()function. Instead of a single starting point, define wide lower and upper bounds for each parameter in the error model [32]. - Algorithm Logic: The MSNLS algorithm (e.g., as implemented in

gslnls) generates a population of starting points within the defined hyper-rectangles. It runs local optimizations from these points, clusters similar solutions, and iteratively focuses search efforts on promising regions to efficiently locate the global minimum of the residual sum of squares [31] [32].

- Using

Validation: Validate the final AEE by checking the goodness-of-fit (e.g., residual plots, R²), and by assessing if the predicted SDs are accurate for validation samples not used in the fit. Robust regression techniques like Theil's regression with the Siegel estimator have been found effective for finalizing AEEs [30].

Model Requirements and the MSNLS Solution Strategy

The requirements for a successful NLS model fit extend beyond a correct mathematical form. Key requirements include identifiability, appropriate weighting, and provision of initial parameter estimates that lead to the global optimum.

Protocol 2: Implementing MSNLS for a Complex Pharmacokinetic Model

This protocol applies MSNLS to fit a complex nonlinear model, such as a multi-compartment PK model with an associated error structure, where parameter correlation is high and initial guesses are uncertain.

Objective: To estimate the parameters (e.g., clearance CL, volume V, rate constants) of a nonlinear PK model (e.g., a two-compartment model with Michaelis-Menten elimination [28]) from observed plasma concentration-time data.

Materials & Reagents:

- PK/PD dataset (Time, Concentration, Subject covariates).

- Software with MSNLS capability:

gslnlsin R [2] [32], AIMMS with its MultiStart module [31], FICO Xpress NonLinear with multistart [34], or custom tools like MENOTR [29]. - Defined PK model equation and associated error model (AEE from Protocol 1).

Computational Workflow:

Figure 2: Multi-Start NLS Algorithm Logic. An iterative process of sampling, local optimization, and clustering to efficiently find the global solution.

Procedure:

Model and Error Definition: Formulate the structural PK model, f(Θ, t), where Θ is the vector of parameters. Integrate the error model from the AEE such that the weight for observation i is w_i = 1 / (SD(C_i))². The objective is to minimize the weighted residual sum of squares (WRSS): ∑ w_i · ( C_obs,i - f(Θ, t_i) )² [27].

Define Parameter Search Space: Instead of a single initial guess, define plausible lower and upper bounds for each parameter in Θ based on physiological or pharmacological principles (e.g., clearance must be positive, volume between 5-500 L). This is the most critical user input in MSNLS.

Configure and Execute MSNLS:

- In

gslnls, this is done directly in thestartargument as shown in Protocol 1. The algorithm will dynamically handle the search [32]. - In a system like AIMMS, the procedure

DoMultiStartis called on the generated mathematical program instance. The algorithm generatesNumberOfSamplePoints, selects the bestNumberOfSelectedSamplePoints, and solves the NLP from each, filtering points that fall into the "basin of attraction" of an already-found solution using cluster analysis to avoid redundant work [31].

- In

Analysis of Results: The MSNLS output will provide the parameter set Θ corresponding to the lowest WRSS found (the putative global minimum). Standard diagnostics (parameter correlations, confidence intervals via

confintdingslnls[2], residual plots) should be performed on this final model.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Computational Tools

| Item / Software | Primary Function / Role | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

gslnls R Package [2] [32] |

Provides R bindings to the GNU Scientific Library (GSL) for NLS and MSNLS fitting via gsl_nls(). Supports robust regression and large/sparse problems. |

Primary tool for implementing MSNLS in pharmacokinetic data fitting and AEE development within the R environment. |

| AIMMS with MultiStart Module [31] | A modeling system with a built-in, scriptable multistart algorithm for nonlinear programs (NLPs). Uses cluster analysis to manage starting points. | Solving complex, constrained optimization problems in pharmaceutical supply chain or dose regimen optimization. |

| FICO Xpress NonLinear with Multistart [34] | A solver feature that performs parallel multistart searches by perturbing initial points and solver controls to explore the feasible space for local optima. | Large-scale, industrial nonlinear optimization problems where robustness to initial points is required. |

| MENOTR Toolbox [29] | A hybrid metaheuristic toolbox combining Genetic Algorithms (GA) with NLS to overcome initial guess dependence, specifically designed for biochemical kinetics. | Fitting complex kinetic and thermodynamic models where parameter correlation is high and traditional NLS fails. |

| Validated LC-MS/MS System [30] [33] | Gold-standard bioanalytical platform for quantifying drug concentrations in biological matrices with high sensitivity and specificity. | Generating the precision profile data necessary for empirical AEE development. |

| Isotopically Labeled Internal Standards (IS) [30] | Compounds chemically identical to the analyte but with heavier isotopes, added to samples to correct for variability in sample preparation and ionization. | Critical for ensuring accuracy and precision in LC-MS/MS assays, improving the reliability of the SD estimates used in AEEs. |

Practical Implementation: Algorithms and Tools for Robust Parameter Estimation

Within the framework of a broader thesis on multi-start nonlinear least squares implementation, the selection of an appropriate optimization algorithm is paramount. Nonlinear least squares problems are ubiquitous in scientific and industrial research, from calibrating models in drug development to solving inverse problems in non-destructive evaluation. This application note provides a detailed comparison of three prominent algorithms—Gauss-Newton (GN), Levenberg-Marquardt (LM), and NL2SOL—focusing on their theoretical foundations, performance characteristics, and implementation protocols to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate method for their specific applications.

The efficacy of a multi-start approach, which involves initiating optimization from multiple starting points to locate the global minimum, is highly dependent on the performance of the underlying local optimization algorithm. Key considerations include convergence rate, robustness to noise, handling of ill-conditioned problems, and computational efficiency. This document synthesizes current research findings to provide a structured framework for algorithm selection within this context.

Gauss-Newton (GN) Method

The Gauss-Newton algorithm is a classical approach for solving non-linear least squares problems by iteratively solving linearized approximations. It approximates the Hessian matrix using only first-order information, assuming that the second-order derivatives of the residuals are negligible. For a residual function ( \mathbf{r}(\mathbf{x}) ), the update step ( \mathbf{\delta} ) is determined by solving:

[ (\mathbf{J}^T\mathbf{J}) \mathbf{\delta} = -\mathbf{J}^T \mathbf{r} ]

where ( \mathbf{J} ) is the Jacobian matrix of the residuals. The GN algorithm converges rapidly when the initial guess is close to the solution and the residual at the minimum is small. However, its primary limitation is that the matrix ( \mathbf{J}^T\mathbf{J} ) may become singular or ill-conditioned, particularly when the starting point is far from the solution or for problems with large residuals [35] [36].

Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) Method

The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm addresses the instability of the Gauss-Newton method by introducing a damping factor, effectively interpolating between Gauss-Newton and gradient descent. The update step in LM is given by:

[ (\mathbf{J}^T\mathbf{J} + \lambda \mathbf{I}) \mathbf{\delta} = -\mathbf{J}^T \mathbf{r} ]

where ( \lambda ) is the damping parameter and ( \mathbf{I} ) is the identity matrix. A modified version replaces the identity matrix with the diagonal of ( \mathbf{J}^T\mathbf{J} ), enhancing scale invariance [36]. The LM method is more robust than GN when starting far from the solution and can handle problems where the Jacobian is rank-deficient. Recent convergence analyses confirm that LM exhibits quadratic convergence under appropriate conditions, even for inverse problems with Hölder stability estimates [37] [38].

NL2SOL Algorithm

NL2SOL is an adaptive nonlinear least-squares algorithm that employs a trust-region approach with sophisticated Hessian approximation. Its distinctive feature is the adaptive choice between two Hessian approximations: the Gauss-Newton approximation alone, and the Gauss-Newton approximation augmented with a quasi-Newton approximation for the remaining second-order terms. This hybrid approach allows NL2SOL to maintain efficiency on small-residual problems while providing robustness on large-residual problems or when the starting point is poor. The algorithm is particularly effective for problems that are not over-parameterized and typically exhibits fast convergence [39] [40] [41].

Table 1: Core Algorithmic Characteristics

| Feature | Gauss-Newton (GN) | Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) | NL2SOL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hessian Approximation | ( \mathbf{J}^T\mathbf{J} ) | ( \mathbf{J}^T\mathbf{J} + \lambda \mathbf{D} ) | Adaptive: GN + quasi-Newton |

| Update Strategy | Linear solve | Damped linear solve | Trust-region |

| Primary Convergence | Quadratic (favorable conditions) | Quadratic (under assumptions) | Quadratic |

| Key Strengths | Fast for small residuals | Robust to poor initializations | Efficient for large residuals |

Performance Comparison and Selection Criteria

Quantitative Performance Analysis

A comprehensive comparison of 15 different non-linear optimization algorithms for recovering conductivity depth profiles using eddy current inspection provides valuable performance insights. The study evaluated algorithms based on their error reduction after ten iterations under different noise conditions and a priori estimates [35].

Table 2: Algorithm Performance in Inverse Problem Application

| Algorithm | Performance in Case 1 (Low Noise) | Performance in Case 2 (High Noise) | Computational Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gauss-Newton | Fast convergence when well-conditioned | Prone to instability | Low |

| Levenberg-Marquardt | Competitive | Most competitive in some noisy cases | Moderate |

| Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (BFGS) | Most competitive in some cases | Variable performance | Moderate |

| NL2SOL (Augmented LM) | Most competitive in some cases | Robust performance | Moderate to High |

The study concluded that the most competitive algorithm after ten iterations was highly dependent on the a priori estimate and noise level. For certain problem configurations, BFGS, augmented LM (NL2SOL), and LM each performed best in different case studies, highlighting the importance of problem-specific selection [35].

Algorithm Selection Guidelines

Based on the synthesized research, the following selection criteria are recommended for implementation within a multi-start framework:

For well-conditioned problems with small residuals and good initial guesses: The Gauss-Newton method is often the most efficient choice due to its simplicity and rapid convergence.

For problems with uncertain initializations or moderate noise levels: The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm provides a balanced approach with good robustness while maintaining reasonable convergence rates.

For problems with large residuals, strong nonlinearity, or when working with limited data support: NL2SOL is generally preferred due to its adaptive Hessian approximation and trust-region implementation, which often makes it more reliable than GN or LM [35] [40] [41].

Within multi-start frameworks: Consider employing different algorithms at various stages—faster, less robust algorithms for initial screening of starting points, and more sophisticated algorithms like NL2SOL for refinement of promising candidates.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol for Conducting Algorithm Comparisons

Objective: To empirically evaluate the performance of GN, LM, and NL2SOL algorithms on a specific nonlinear least squares problem.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Development environment: MATLAB, Python (with SciPy), or a compiled language with appropriate numerical libraries

- Implementation of the residual function and Jacobian computation

- Test problem with known minimum (synthetic or benchmark)

- Data set (synthetic or experimental) for calibration

Procedure:

- Problem Formulation:

- Define the residual vector ( \mathbf{r}(\mathbf{x}) ) for the target problem

- Implement function to compute Jacobian matrix (analytic or finite-difference)

Algorithm Configuration:

- Set common parameters: maximum iterations (e.g., 100-1000), function tolerance (e.g., 1e-8)

- Configure algorithm-specific parameters:

- LM: Initial damping parameter (e.g., 1e-3), update strategy

- NL2SOL: Convergence tolerances (xctol, rfctol), trust region parameters

Experimental Execution:

- Execute each algorithm from identical starting points

- For multi-start framework, select diverse initial points across parameter space

- Record for each run: iteration count, function evaluations, computation time, final objective value, and convergence status

Performance Metrics Collection:

- Track convergence history (objective value vs. iteration)

- Compute convergence rates from experimental data

- Record robustness metrics (success rate from multiple starting points)

Sensitivity Analysis:

- Test algorithm performance with different noise levels added to synthetic data

- Evaluate scalability with problem dimension (number of parameters)

Deliverables:

- Performance comparison table highlighting relative strengths

- Convergence history plots for visual comparison

- Recommendation for primary algorithm in specific application domains

Protocol for Multi-Start Nonlinear Least Squares Implementation

Objective: To implement a robust multi-start framework for global optimization of nonlinear least squares problems.

Procedure:

- Initialization Phase:

- Define parameter bounds and distribution for initial guesses

- Determine number of starting points (typically 50-1000 based on problem dimension and computational budget)

- Generate diverse starting points using Latin Hypercube Sampling or similar space-filling design

Screening Phase:

- Execute fast, approximate optimization from each starting point using a moderate iteration limit

- Apply clustering in parameter space to identify promising regions

- Select top candidates (e.g., 10-20% of initial points) based on objective value for refinement

Refinement Phase:

- Execute robust optimization algorithm (e.g., NL2SOL or LM) on promising candidates

- Use strict convergence tolerances for final refinement

- Apply convergence diagnostics to verify local minima

Validation and Selection:

- Compare final solutions from different starting points

- Select global minimum candidate based on objective value and constraint satisfaction

- Perform posterior analysis (e.g., confidence intervals, parameter correlations)

Visualization of Algorithm Workflows

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Test Problems | Validate algorithm performance | Use known benchmark problems with controlled noise |

| Experimental Calibration Data | Real-world performance evaluation | Nuclear graphite conductivity [35], chemical kinetics |

| Finite Element Model | Forward problem solver for inverse problems | Generate synthetic data with superimposed noise [35] |

| Jacobian Calculation | Provide gradient information | Analytic form or finite-difference approximation |

| Convergence Metrics | Quantitative performance assessment | Track objective value, parameter changes, gradient norms |

| NL2SOL Software Implementation | Reference robust algorithm | FORTRAN library or Dakota implementation [39] [40] |

| Multi-Start Framework | Global optimization capability | Implement space-filling design for diverse starting points |

This application note has provided a comprehensive comparison of the Gauss-Newton, Levenberg-Marquardt, and NL2SOL algorithms for nonlinear least squares optimization within the context of multi-start implementation research. The performance analysis demonstrates that algorithm selection is highly problem-dependent, with factors such as residual size, initialization quality, and noise levels significantly influencing optimal choice.

For researchers implementing multi-start frameworks, a hybrid approach that leverages the strengths of each algorithm at different stages of the optimization process is recommended. The experimental protocols and visualization workflows provided herein offer practical guidance for empirical evaluation and implementation. As optimization requirements evolve in scientific and industrial applications, particularly in domains such as drug development and inverse problems, this structured approach to algorithm selection provides a foundation for robust and efficient parameter estimation.

Nonlinear least squares (NLS) estimation represents a fundamental computational challenge across scientific domains, particularly in pharmaceutical research where parameters of complex biological models must be accurately estimated from experimental data. The gslnls R package implements multi-start optimization algorithms through bindings to the GNU Scientific Library (GSL), providing enhanced capabilities for addressing the critical limitation of initial value dependence in traditional NLS algorithms [42] [43]. This implementation deep dive explores the package's theoretical foundations, practical applications, and protocol development within the broader context of multi-start nonlinear least squares implementation research.

The core challenge in NLS optimization lies in the non-convex nature of parameter estimation problems, where local optimization algorithms frequently converge to suboptimal local minima depending on their starting parameters [43]. This dependency introduces potential user bias and reduces reproducibility in scientific modeling. The gslnls package addresses this limitation through modified quasi-random sampling algorithms based on Hickernell and Yuan's work [10], enabling more robust parameter estimation for complex biochemical, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic models encountered in drug development.

Theoretical Foundations and Algorithmic Implementation

Trust Region Methods in GSL

The gslnls package provides R bindings to the GSL gsl_multifit_nlinear and gsl_multilarge_nlinear modules, implementing several trust region algorithms for nonlinear least squares problems [2] [42]. Trust region methods solve NLS problems by iteratively optimizing local approximations within a constrained region around the current parameter estimate, adjusting the region size based on approximation accuracy.

The available algorithms include:

- Levenberg-Marquardt (

"lm"): The default algorithm that interpolates between gradient descent and Gauss-Newton approaches [42] - Levenberg-Marquardt with geodesic acceleration (

"lmaccel"): An extended algorithm incorporating second-order curvature information for improved stability and convergence [42] - Powell's dogleg (

"dogleg"): An approach that models the trust region subproblem with a piecewise linear path [2] - Double dogleg (

"ddogleg"): An enhancement of the dogleg algorithm incorporating information about the Gauss-Newton step [44] - 2D subspace (

"subspace2D"): A method searching a larger subspace for solutions [44]

Table 1: Trust Region Algorithms in gslnls

| Algorithm | Key Features | Best Suited Problems |

|---|---|---|

| Levenberg-Marquardt | Balance between gradient descent and Gauss-Newton | Small to moderate problems with good initial guesses |

| LM with geodesic acceleration | Second-order curvature information | Problems susceptible to parameter evaporation |

| Powell's dogleg | Piecewise linear path in trust region | Well-scaled problems with approximate Jacobian |

| Double dogleg | Includes Gauss-Newton information | Problems far from minimum |

| 2D subspace | Searches larger solution space | Problems where dogleg converges slowly |

Multi-Start Algorithm Implementation

The multi-start algorithm in gslnls implements a modified version of the Hickernell and Yuan (1997) algorithm designed to efficiently explore the parameter space while minimizing computational redundancy [10] [44]. The algorithm employs quasi-random sampling using Sobol sequences (for parameter dimensions <41) or Halton sequences (for dimensions up to 1229) to generate initial starting points distributed throughout the parameter space [44].

Key innovations in the implementation include:

- Dynamic range adjustment: Parameter ranges can be updated during optimization when starting ranges are partially or completely unspecified [10]

- Inverse logistic scaling: Starting values are scaled to favor regions near the center of the parameter domain, improving convergence efficiency [44]

- Two-phase local search: Inexpensive and expensive local search phases with different iteration limits optimize the trade-off between exploration and computation [44]