Multi-Scale Biological Networks: Bridging Molecular to Organ-Level Physiology for Drug Discovery

This article explores the transformative role of multi-scale biological network models in understanding human physiology and advancing therapeutic development.

Multi-Scale Biological Networks: Bridging Molecular to Organ-Level Physiology for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of multi-scale biological network models in understanding human physiology and advancing therapeutic development. It provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of biological hierarchy—from molecular to organ levels. The piece details cutting-edge computational methodologies, including data-driven model identification and multilayer network control, and addresses key challenges in integrating disparate biological scales. Through comparative analysis of model types and validation via case studies in cancer and neuroscience, we demonstrate how these integrative frameworks enable accurate phenotype prediction and identification of robust, clinically relevant drug targets, ultimately bridging the gap between genotype and complex disease phenotypes.

The Hierarchical Architecture of Life: Defining Multi-Scale Biological Networks

Biological systems are fundamentally multiscale, operating across diverse spatial and temporal domains—from the atomic level of biomolecules to the complete organism [1]. This complex hierarchy, where interactions at smaller scales dictate phenomena at larger scales, presents a significant challenge for traditional research methods that focus on a single tier of resolution. A comprehensive understanding of human physiology requires the explicit integration of data and models across these scales [1]. The multiscale nature of biological systems means that their components often behave differently in isolation than when integrated into the living organism, necessitating computational models that can capture the connectivity between these divergent scales of biological function [1]. This integration is crucial for advancing research, diagnosis, and the development of personalized therapies, as it enables the mapping of detailed anatomical data with standardized disease characteristics [2].

Defining the Scales of Biological Organization

Biological organization can be explicitly divided into spatial and temporal scales. The explicit modeling of multiple tiers of resolution provides additional information that cannot be obtained by independently exploring a single scale in isolation [1].

Table 1: Characteristic Spatial Scales in Biological Systems

| Scale Tier | Typical Size Range | Key Components and Processes |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic/Molecular | Ångströms (Å) to nanometers (nm) | Protein folding, molecular binding, gene transcription, metabolic reactions. |

| Organelle/Cellular | Nanometers (nm) to micrometers (µm) | Signal transduction, organelle function, cellular metabolism, cell division. |

| Tissue | Micrometers (µm) to millimeters (mm) | Cellular neighborhoods, extracellular matrix, functional tissue units (e.g., renal corpuscle). |

| Organ | Millimeters (mm) to centimeters (cm) | Organ-specific functions (e.g., gas exchange in lungs, filtration in kidneys). |

| Organism | Centimeters (cm) to meters (m) | Systemic physiology, inter-organ communication, whole-body homeostasis. |

Table 2: Characteristic Temporal Scales in Biological Systems

| Biological Process | Typical Time Scale | Associated Spatial Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Phosphorylation | Milliseconds to seconds | Molecular |

| Gene Expression | Minutes to hours | Cellular |

| Cell Division | Hours to days | Cellular |

| Tissue Remodeling | Days to weeks | Tissue |

| Organ Development | Weeks to years | Organ |

| Organism Lifespan | Years to decades | Organism |

The relationship between spatial and temporal scales is often interdependent, with subcellular processes generally occurring on much faster time scales than those at the tissue or organ level [3]. The cell represents a central focal plane, being the minimal unit of life, from which one can scale up to tissues and organs or down to molecules and atoms [3].

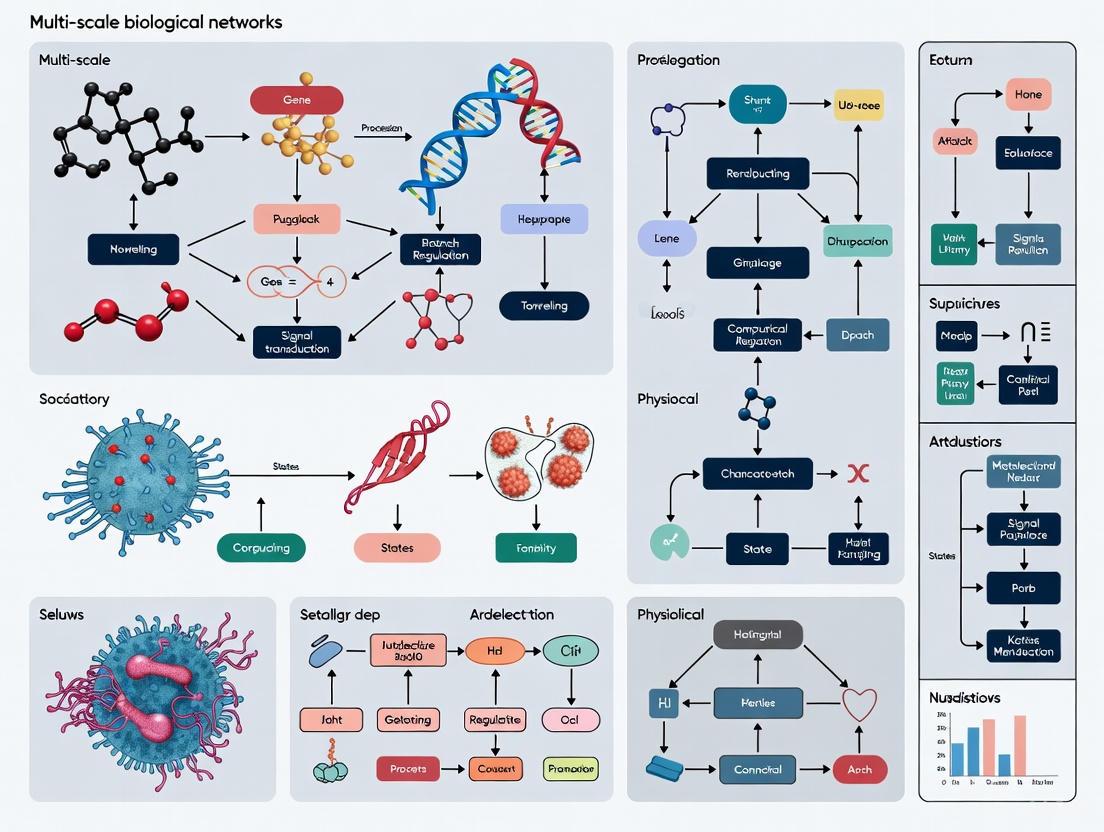

Figure 1: The hierarchical spatial organization of biological systems from atoms to organisms.

Computational Frameworks for Multiscale Modeling

Mathematical and computational models are uniquely positioned to capture the connectivity between divergent biological scales, bridging the gap between isolated in vitro experiments and whole-organism in vivo models [1]. These models can be broadly classified into continuous and discrete strategies, each with distinct strengths for capturing different aspects of system dynamics [1].

Continuous Modeling Approaches

Continuous modeling strategies typically employ Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) and Partial Differential Equations (PDEs). Systems of ODEs, frequently using mass action kinetics, are leveraged to represent chemical reactions within the cell, where the assumption of steady state is often valid due to rapid kinetics relative to the overall model timeframe [1]. Models of reaction-diffusion kinetics, often implemented as PDEs, are used to represent intra- and extracellular molecular binding and diffusion [1]. Finite element and finite volume methods are particularly suited for modeling geometrically constrained properties across scales, such as cell surface interfaces and tissue mechanics [1].

Data-Driven System Identification

For cases where deriving governing equations from first principles is impractical, data-driven methods can identify dynamics directly from observational data. The SINDy (Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics) framework identifies sparse models by selecting a minimal set of nonlinear functions to capture system dynamics [4]. Weak SINDy and iNeural SINDy improve robustness against noisy and sparse data, with the latter integrating neural networks and an integral formulation to handle challenging datasets [4]. Other approaches include symbolic regression methods like PySR and ARGOS, which use evolutionary algorithms to discover closed-form equations, and Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs), which incorporate physical laws into their structure [4].

A Novel Hybrid Framework for Multi-Scale Data

A recent algorithmic framework integrates the weak formulation of SINDy, Computational Singular Perturbation (CSP), and neural networks (NNs) for Jacobian estimation [4]. This approach automatically partitions a dataset into subsets characterized by similar dynamics, allowing valid reduced models to be identified in each region without facing a wide time scale spectrum [4]. When SINDy fails to recover a global model from a full dataset, CSP—leveraging Jacobian estimates from NNs—successfully isolates dynamical regimes where SINDy can be applied locally [4]. This framework has been successfully validated using the Michaelis-Menten biochemical model, consistently identifying appropriate reduced dynamics even when data originated from stochastic simulations [4].

Figure 2: Workflow for data-driven multiscale system identification using SINDy, CSP, and neural networks.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Data-Driven Multiscale System Identification

This protocol outlines the methodology for identifying reduced models from multiscale observational data using the SINDy-CSP-NN framework [4].

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Collect high-dimensional time-series data from the biological system of interest. Data can originate from simulations (e.g., stochastic versions of biochemical models like Michaelis-Menten) or experimental observations.

- Preprocess data to handle noise and missing values. Normalize datasets if necessary to ensure numerical stability in subsequent steps.

Neural Network Training for Jacobian Estimation:

- Design a neural network architecture suitable for approximating the system's dynamics. The network should take the system state as input and output the estimated derivative.

- Train the network using the preprocessed observational data. The loss function typically minimizes the difference between the network's predicted state derivative and the finite-difference approximation of the actual state derivative.

- Use automatic differentiation on the trained network to compute the Jacobian matrix of the vector field for any given state point in the dataset [4].

Time-Scale Decomposition with Computational Singular Perturbation (CSP):

- Employ the CSP algorithm using the Jacobian matrices estimated by the neural network.

- The algorithm will identify the number of exhausted modes and partition the dataset into subsets where the dynamics evolve on similar time scales [4].

- This step effectively isolates regions of the phase space where distinct, reduced models govern the dynamics.

Sparse Model Identification with SINDy:

- For each data subset generated by CSP, create a comprehensive library of candidate basis functions (e.g., polynomials, trigonometric functions) that could potentially describe the dynamics.

- Apply the SINDy algorithm to each subset independently to perform sparse regression. This identifies the minimal set of functions from the library that accurately capture the dynamics within that specific regime [4].

- The output is a set of parsimonious, interpretable ordinary differential equations for each dynamical regime.

Model Validation:

- Validate the identified reduced models by comparing their predictions against held-out experimental or simulated data not used in the training process.

- Assess the models' ability to capture key dynamical features, such as transient behaviors and steady states, within their respective regions of validity.

Protocol: Analyzing Cell Neighborhoods in Tissue

This protocol describes a method for quantifying changes in cellular microenvironments, relevant for studying diseases like bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) in lung tissue [2].

Tissue Sampling and Multiplexed Imaging:

- Obtain tissue samples from both healthy and diseased subjects.

- Perform multiplexed immunofluorescence microscopy on tissue sections. This technique labels multiple specific cell types (e.g., parenchymal cells, endothelial cells, macrophages) with distinct fluorescent markers within the same sample.

Image Analysis and Cell Typing:

- Use computational image analysis tools to identify individual cell nuclei and their spatial coordinates within the tissue.

- Classify each cell based on its marker expression profile into specific cell types (e.g., endothelial, epithelial, immune cells).

Spatial Analysis with Cell Distance Explorer:

- Input the cell type and coordinate data into a spatial analysis tool, such as the publicly available Cell Distance Explorer [2].

- The tool systematically quantifies and visualizes the distances between different cell types, defining the local cellular neighborhood.

Comparative Visualization and Statistical Analysis:

- Generate cell distance distribution graphs (e.g., violin plots) to compare the spatial organization in healthy versus diseased tissue.

- Statistically compare distance distributions for cell types common to both conditions to identify significant changes in tissue architecture resulting from disease or aging [2].

Table 3: Key Computational and Experimental Resources for Multiscale Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tool / Reagent | Function and Application in Multiscale Research |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Modeling Tools | COmplex PAthways SImulator (COMPASI) [1] | Executes systems of ODEs to model molecular pathways within multiscale models (e.g., TGF-β1 in wound healing). |

| SINDy Algorithm [4] | Identifies sparse, interpretable dynamical systems models directly from time-series data. | |

| Cytoscape [5] | Open-source platform for visualizing complex biological networks and integrating with other data. | |

| Spatial Analysis Platforms | Human Reference Atlas (HRA) [2] | Provides a multiscale, 3D common coordinate framework for aggregating and analyzing data across spatial scales. |

| Cell Distance Explorer [2] | Publicly available tool to systematically quantify and visualize distances between cell types in tissue. | |

| Data Visualization Resources | Circos [5] | Tool for creating circular layouts, ideal for visualizing genomic data and linkages. |

| CIE Lab Color Space [6] | A perceptually uniform color space for creating accurate and accessible scientific visualizations. | |

| Experimental Reagents | Multiplexed Immunofluorescence Antibodies [2] | Enable simultaneous labeling of multiple cell types in tissue for spatial analysis of cellular neighborhoods. |

The inherent multiscale structure of biology, from atoms to organisms, demands integrative research strategies that transcend traditional single-scale approaches. Computational frameworks that couple continuous and discrete models, along with novel data-driven methods like the SINDy-CSP-NN framework, are proving essential for characterizing biological components holistically [4] [1]. The ongoing development of resources like the Multiscale Human Reference Atlas provides the foundational infrastructure to map and model this complexity in support of precision medicine [2]. As these tools and methodologies mature, they offer the promise of unlocking deeper insights into complex biological phenomena, from tissue patterning and disease pathogenesis to the development of novel therapeutic interventions.

In the study of multi-scale biological networks in human physiology, the precise definition of scale forms the foundation for generating meaningful, reproducible data. Scale encompasses three interdependent dimensions: resolution (the smallest distinguishable detail), field of view (the total area observed), and level of biological organization (the structural hierarchy from molecules to organisms). These dimensions exist in a fundamental trade-off: increasing resolution typically necessitates decreasing field of view, while the biological question dictates the appropriate level of organization that must be targeted. Understanding and navigating these relationships is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to connect molecular mechanisms to physiological outcomes.

Modern technological advances are rapidly reshaping these traditional constraints. Cutting-edge approaches now enable the integration of data across scales, from nanoscale protein complexes to macroscale brain networks [7]. This whitepaper provides a technical framework for defining scale in biological research, offering quantitative comparisons, detailed methodologies, and practical tools for designing experiments within multi-scale biological networks.

Quantitative Dimensions of Scale: A Technical Reference

The following tables summarize key quantitative parameters across biological scales, providing a reference for experimental design.

Table 1: Spatial Scale Characteristics Across Biological Levels

| Level of Biological Organization | Typical Spatial Scale | Resolution of Representative Technologies | Field of View of Representative Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Complexes | 1 - 100 nm | ~1 nm (Cryo-EM) | ~1 μm² (Cryo-EM) |

| Subcellular Organelles | 100 nm - 1 μm | ~200 nm (Light Microscopy) | ~100 μm² (Confocal Microscopy) |

| Single Cells | 1 - 100 μm | ~200 nm (Super-resolution Microscopy) | ~1 mm² (Whole-slide Imaging) |

| Tissues | 100 μm - 1 cm | ~1 μm (Medical CT) | ~0.5 m² (Whole-body CT) |

| Organ Systems | 1 cm - 2 m | 1-10 mm (fMRI) | ~0.5 m² (Whole-body CT) |

Table 2: Temporal Resolution and Data Volume Across Imaging Modalities

| Imaging Modality | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Resolution | Data Volume per Sample | Primary Biological Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Microscopy | Minutes to hours | < 10 nm | Terabytes to Petabytes | Synaptic connectivity, ultrastructure [8] |

| Confocal Microscopy | Seconds to minutes | ~200 nm | Megabytes to Gigabytes | Live cell imaging, 3D tissue architecture [9] |

| Two-Photon Calcium Imaging | Sub-second | ~1 μm | Gigabytes to Terabytes | Neural population dynamics [8] |

| Functional MRI (fMRI) | 1-2 seconds | 1-2 mm | Megabytes to Gigabytes | Brain-wide functional connectivity [10] |

| Medical CT | Sub-second | 50-500 μm | Gigabytes | Gross anatomy, lesion detection [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Scale Integration

Multimodal Cell Mapping for Subcellular Architecture

Objective: To systematically map protein subcellular organization across scales by integrating biophysical interaction data and immunofluorescence imaging [7].

Workflow Overview: The multi-stage experimental and computational workflow is summarized below:

Detailed Methodology:

Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition:

- Cell Line: Use U2OS osteosarcoma cells with systematic C-terminal Flag-HA tagging via lentiviral expression from the human ORFeome library.

- Protein Interaction Data (AP-MS): Isolate protein complexes from whole-proteome extracts using affinity purification. Identify interacting partners via tandem mass spectrometry to generate a protein-protein interaction network.

- Imaging Data (Immunofluorescence): Perform confocal imaging of cells stained with antibodies against target proteins. Co-stain each sample with reference markers for nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum, and microtubules to provide consistent subcellular landmarks.

Multimodal Data Integration:

- Process imaging and AP-MS data streams separately to generate protein features for each modality.

- Employ a self-supervised machine learning approach to create a unified multimodal embedding for each protein. This approach minimizes reconstruction loss (preserving original data) while optimizing contrastive loss (capturing protein similarities/differences across modalities).

Assembly Detection and Annotation:

- Compute all pairwise protein-protein distances in the multimodal embedding space.

- Apply multiscale community detection to identify protein assemblies as modular communities at multiple resolutions.

- Annotate assemblies through expert curation assisted by large language models (GPT-4), which generates descriptive names and functional interpretations for protein sets with high confidence.

Validation: Systematically validate assemblies using an orthogonal method: perform proteome-wide size-exclusion chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (SEC-MS) in the same U2OS cellular context.

Functional Connectomics Across Visual Cortical Areas

Objective: To bridge neuronal function and circuitry at the cubic millimeter scale in mouse visual cortex by co-registering in vivo calcium imaging with electron microscopy reconstruction [8].

Detailed Methodology:

In Vivo Calcium Imaging:

- Subject: Use transgenic mice (Slc17a7-Cre and Ai162) expressing GCaMP6s in excitatory neurons.

- Imaging System: Employ a two-photon random access mesoscope (2P-RAM) with wide field of view.

- Visual Stimulation: Present naturalistic and parametric video stimuli to the mouse's left visual field during imaging, while monitoring behavior (locomotion, eye movements, pupil diameter).

- Spatial Coverage: Perform 14 individual scans across multiple imaging planes (up to 500 μm depth) targeting primary visual cortex (VISp) and higher visual areas (VISrl, VISal, VISlm) to capture retinotopically matched neurons.

- Data Processing: Automatically segment somas using constrained non-negative matrix factorization. Extract and deconvolve fluorescence traces to yield activity traces for approximately 75,000 neurons.

Electron Microscopy Reconstruction:

- Tissue Preparation: Extract the imaged tissue volume, prepare for EM, and section.

- Imaging: Continuously image sections over six months using serial section transmission EM (TEM).

- Reconstruction: Montage and align EM data. Densely segment the volume using scalable convolutional networks. Perform extensive proofreading on a subset of neurons to correct automated segmentation errors.

Data Co-registration:

- Acquire high-resolution structural stacks with fluorescent dye (Texas Red) to label vasculature as fiducial markers.

- Register functional imaging data with the structural stack, then co-register with the EM volume.

- Assign 3D centroids to functionally imaged neurons in the shared coordinate system to match neuronal responses to their structural connectivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Multi-Scale Biological Imaging

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| ORFeome Library | Provides standardized, sequence-validated open reading frames for systematic protein tagging | Genome-scale protein interaction mapping [7] |

| GCaMP6s Calcium Indicator | Genetically encoded calcium sensor for monitoring neuronal activity | In vivo calcium imaging of excitatory neurons in visual cortex [8] |

| Flag-HA Tandem Tag | Affinity tag for purification and detection of expressed proteins | Isolation of protein complexes for AP-MS [7] |

| Texas Red Fluorescent Dye | Vasculature labeling for creating fiducial markers | Co-registration between calcium imaging and electron microscopy data [8] |

| Specific Antibodies for Immunofluorescence | Target protein detection with subcellular resolution | Mapping protein localization patterns in U2OS cells [7] |

| GPT-4 Large Language Model | Computational tool for generating descriptive names and functional interpretations | Annotating previously undocumented protein assemblies [7] |

Computational Framework for Multi-Scale Data Integration

The integration of data across scales requires sophisticated computational approaches. The following diagram illustrates the information flow in a generalized multi-scale analysis pipeline, from raw data acquisition to biological insight:

Key Computational Considerations:

- Data Volume Management: Modern imaging datasets can reach terabytes for a single experiment (e.g., time-lapse confocal microscopy) or petabytes for connectomics projects [11] [8]. Effective management requires tiered storage architectures balancing accessibility and cost.

- Multimodal Integration: Self-supervised approaches position proteins or neural entities in embedding spaces such that original imaging and interaction features can be reconstructed with minimal information loss while capturing relative similarities [7].

- Community Detection: Multiscale community detection techniques identify modular organization at different hierarchical levels, from protein complexes to brain networks [10] [7].

- Spatial and Quantitative Preservation: Methods like STABLE (Spatial and Quantitative Information Preserving Biomedical Image Translation) enforce information consistency and employ learnable upsampling operators to maintain precise spatial alignment and signal intensities when translating between imaging modalities [12].

Defining scale through the precise interrelationship of resolution, field of view, and biological organization level is fundamental to advancing human physiology research and drug development. The experimental frameworks and technical resources presented here provide researchers with practical methodologies for investigating biological networks across spatial and organizational scales. As multimodal data integration becomes increasingly sophisticated—encompassing molecular precision, cellular resolution, and system-level dynamics—our ability to uncover the organizing principles of human physiology will fundamentally transform. The emerging paradigm leverages computational power to bridge traditional scale boundaries, promising unprecedented insights into health and disease.

Biological systems are inherently multiscale, organized hierarchically from molecular complexes and cells to tissues and entire organs [13]. At every level of this hierarchy, the physical or functional proximity between constituent elements—be they proteins, cells, or brain regions—forms a foundational layer of biological organization. Proximity networks have emerged as a powerful computational framework for quantifying and analyzing these relationships, enabling researchers to move from descriptive observations to predictive, quantitative models. These networks represent biological entities as nodes and their pairwise proximities as edges, creating a unified data structure that transcends traditional scale boundaries. Within physiology and drug development, this approach facilitates mechanistic insights into how local interactions at smaller scales give rise to emergent physiological behaviors at larger scales, ultimately bridging the gap between cellular pathophysiology and organism-level clinical manifestations.

The analytical power of proximity networks stems from their ability to integrate heterogeneous data types through a common mathematical formalism. Whether derived from protein co-localization, neuronal synaptic connectivity, or cellular adjacencies in tissues, proximity relationships can be encoded as network structures amenable to a consistent suite of computational analyses. This review examines how proximity networks serve as a unifying framework across biological scales, detailing the methodological approaches for their construction and analysis, and highlighting their transformative applications in basic research and therapeutic development.

Foundational Principles and Mathematical Formalisms

Defining Proximity Networks

At its core, a proximity network represents a collection of biological entities (nodes) and their pairwise proximity relationships (edges). Formally, for a set of n entities, each entity i (1 ≤ i ≤ n) is described by a data profile Xi representing its measurable characteristics [14]. A distance measure μ quantifies the dissimilarity between entities i and j as μ(Xi, Xj), with higher values indicating greater dissimilarity. Through application of a threshold or probabilistic connection rule, these distances are transformed into a network representation that captures the system's functional architecture.

The mathematical representation begins with the construction of distance matrices that encode all pairwise relationships. Given two data matrices X and Y containing different classes of measurements over the same n entities, distance measures μX and μY generate corresponding distance matrices DX and DY [14]. The relationship between these different proximity measures can then be quantified using statistical approaches such as the Mantel test, which computes a correlation between distance matrices, or the RV coefficient, which characterizes matrix congruence [14]. These foundational operations enable researchers to test hypotheses about how different types of biological proximity relate to one another—for example, whether genetic similarity predicts functional connectivity in neural circuits.

Key Mathematical Models

Several mathematical models provide the theoretical underpinnings for proximity network analysis across biological scales:

The S1 Model: This latent space model positions nodes on a circle with coordinates (κ, θ), where κ represents a node's expected degree and θ its angular similarity coordinate [15]. The connection probability between nodes follows a Fermi-Dirac distribution: p(χij) = 1/(1+χij^1/T), where χij = RΔθij/(μκiκj) is the effective distance and T ∈ (0,1) is the temperature parameter controlling clustering [15]. This model generates networks with tunable degree distributions and strong clustering, mimicking key properties of biological networks.

Dynamic-S1 Model: For temporal proximity data, this extension generates network snapshots as realizations of the S1 model, effectively capturing the time-varying nature of biological interactions while maintaining mathematical tractability [15]. The model reproduces characteristic properties of human proximity networks, including broad distributions of contact durations and repeated group formations.

Hyperbolic Mapping: The S1 model is isometric to random hyperbolic graphs (the H2 model) through the transformation ri = R̂ - 2ln(κi/κ0), which maps degree variables to radial coordinates [15]. This mapping reveals that effective distance χij ≈ e^(½(xij-R̂)), where xij is the approximate hyperbolic distance, providing geometric intuition for why hyperbolic embeddings often successfully capture biological network organization.

Table 1: Core Mathematical Models for Biological Proximity Networks

| Model | Key Parameters | Biological Interpretation | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 Model | κ (degree variable), θ (angular coordinate), T (temperature) | κ: Biological popularity or centrality; θ: Functional similarity; T: Clustering tendency | Static network embedding, community detection, link prediction |

| Dynamic-S1 | Time-varying κ(t), θ(t) parameters | Evolving cellular functions or spatial arrangements | Temporal human proximity networks, epidemic spreading analysis |

| Hyperbolic H2 | r (radial coordinate), θ (angular coordinate) | r: Node centrality; θ: Functional role | Brain networks, protein-protein interactions, multi-scale modeling |

Proximity Networks Across Biological Scales

Molecular and Cellular Scales

At molecular scales, proximity networks capture physical interactions between biomolecules, providing insights into cellular machinery and potential therapeutic targets. Protein-protein interaction networks represent the most established application, where nodes correspond to proteins and edges represent confirmed physical binding or co-complex membership. These networks enable systems-level analysis of cellular signaling, with highly connected "hub" proteins often representing essential cellular components and potential drug targets. Recent advances extend beyond binary interactions to include higher-order networks that capture multi-way relationships, such as triadic interactions where one node regulates the interaction between two others [16]. Information-theoretic approaches like the "Triaction" algorithm can mine these complex relationships from gene expression data, revealing previously overlooked regulatory mechanisms in conditions like Acute Myeloid Leukemia [16].

At the cellular level, proximity networks model spatial organization and functional relationships between cells within tissues. Single-cell RNA sequencing data can be transformed into cellular proximity networks by calculating transcriptional similarity between individual cells, enabling identification of rare cell states and transitional populations during differentiation. In neuroscience, brain-wide cellular connectivity atlases are emerging as comprehensive proximity networks, mapping neuronal connections across the entire brain to understand information processing hierarchies [16]. The Human Reference Atlas (HRA) initiative exemplifies this approach, creating multiscale networks that link anatomical structures, cell types, and biomarkers across the entire human body [16].

Tissue and Organ Systems

In tissue and organ systems, proximity networks model both structural connectivity and functional coordination between distinct anatomical regions. In neuroscience, the brain's connectome represents perhaps the most sophisticated application of proximity networking, with white matter tractography defining structural connections between cortical regions [10]. Beyond physical connections, researchers construct multiscale structural connectomes that incorporate cortico-cortical proximity, microstructural similarity, and white matter connectivity to create comprehensive models of brain organization [10]. Gradient mapping of these networks reveals principal axes of spatial organization, such as the sensory-association axis, which shows continuous expansion during childhood development, reflecting functional specialization of the maturing brain [10].

The analytical power of these networks emerges from their ability to integrate multiple data types. As demonstrated in the multiscale brain structural study, the combination of geodesic distance (physical proximity), microstructural similarity (tissue composition), and white matter connectivity (structural wiring) provides a more complete picture of organizational principles than any single measure alone [10]. This integration enables researchers to track developmental and disease-related reorganization across scales, revealing how local cellular changes propagate to alter system-wide function.

Organism-Level Proximity Networks

At the organism level, human proximity networks capture physical interactions between individuals in social and healthcare settings, with profound implications for understanding disease transmission and social behavior [15]. These temporal networks represent close-range proximity among humans, with edges signifying physical proximity during specific time intervals. Studies have captured such networks in diverse environments including hospitals, schools, scientific conferences, and offices using both direct (RFID) and indirect (Bluetooth) sensing technologies [15]. Despite different contexts and measurement methods, these networks consistently exhibit universal properties including broad distributions of contact durations and repeated formation of interaction groups [15].

The dynamic-S1 model provides a mathematical foundation for these empirical observations, generating synthetic temporal networks that reproduce characteristic structural and dynamical properties of human proximity systems [15]. This model compatibility enables meaningful embedding of time-aggregated proximity networks into low-dimensional spaces, facilitating applications including community identification, efficient routing, link prediction, and analysis of epidemic spreading patterns [15].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Data Acquisition and Network Construction

Constructing biological proximity networks requires specialized methodologies tailored to each scale of investigation:

Molecular Proximity Networks: For protein-protein interactions, affinity purification mass spectrometry (AP-MS) and yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) screens provide complementary approaches for mapping physical proximities. Cross-linking mass spectrometry can further capture transient interactions in native cellular environments. For genomic proximities, chromatin conformation capture techniques (Hi-C, ChIA-PET) measure three-dimensional spatial organization of DNA segments within the nucleus.

Cellular Proximity Networks: Single-cell RNA sequencing enables reconstruction of cellular proximity through computational analysis of transcriptional similarity. Spatially resolved transcriptomics technologies now directly capture spatial organization while profiling gene expression. The Human Reference Atlas consortium provides standardized protocols for mapping cells to reference anatomical structures, enabling cross-study integration [16].

Human Proximity Networks: The SocioPatterns platform provides standardized methodologies for capturing face-to-face interactions in closed settings using active RFID tags, with typical parameters including 20-second time resolution and 1.5-meter proximity range [15]. Bluetooth-based approaches offer wider detection ranges (up to 10 meters) but lower spatial precision, suitable for community-scale studies over extended periods [15].

Analytical Approaches and Computational Tools

The analysis of biological proximity networks employs a diverse toolkit of computational methods:

Distance Matrix Comparison: The Mantel test quantifies correlation between distance matrices, with statistical significance estimated via permutation testing [14]. The RV coefficient provides an alternative measure of matrix congruence with analytical significance testing [14]. For spatial analysis, empirical variograms quantify how property differences vary with spatial separation: γ(k) = (1/|N(k)|) · Σ_(i,j)∈N(k) [dYij]², where N(k) contains entity pairs with spatial distance ≈ k [14].

Network Embedding: Hyperbolic mapping approaches embed time-aggregated proximity networks into hyperbolic space using methods based on the S1 model [15]. These embeddings facilitate community detection, greedy routing, and link prediction by leveraging the geometric structure of latent spaces.

Multiscale Integration: Gradient mapping approaches extract principal axes of organization from multiscale structural connectomes, revealing hierarchical organization patterns such as the sensory-association axis in brain networks [10]. These methods can track developmental changes in network organization and their relationship to cognitive maturation.

Higher-Order Analysis: Information-theoretic frameworks like "Triaction" algorithmically identify triadic interactions where one node regulates the relationship between two others [16]. These approaches move beyond pairwise connections to capture more complex dependency structures in biological systems.

Table 2: Key Analytical Techniques for Proximity Networks

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Outputs | Biological Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matrix Comparison | Mantel test, RV coefficient, Empirical variogram | Matrix correlations, Spatial dependence patterns | Integration of multi-modal data, Spatial covariance structure |

| Network Embedding | Hyperbolic mapping (H2), S1 model fitting, Gradient analysis | Low-dimensional representations, Continuous organizational axes | Latent geometry, Developmental trajectories, Community structure |

| Temporal Analysis | Dynamic-S1 model, Markov modeling, Cross-correlation networks | Transition probabilities, Influence networks, Dynamic communities | Interaction patterns, Information flow, Epidemic spreading dynamics |

| Higher-Order Analysis | Triadic interaction mining, Hypergraph construction | Regulatory triples, Group interactions | Complex dependencies, Higher-order structure beyond pairwise |

Successful construction and analysis of biological proximity networks requires both experimental and computational resources:

Data Acquisition Tools: For molecular proximity networks, crosslinking reagents (e.g., formaldehyde, DSS) stabilize protein complexes for interaction studies. For cellular networks, barcoded oligonucleotides in single-cell RNA sequencing protocols enable transcriptional profiling of individual cells. For human proximity networks, the SocioPatterns platform provides open-hardware solutions for face-to-face interaction tracking [15].

Computational Tools: The BrainSpace toolbox enables gradient analysis of neuroimaging data, critical for mapping principal axes of brain organization [10]. For multiscale structural analysis, the MICA-MNI repository provides specialized code for generating structural manifolds that integrate multiple proximity measures [10]. The Human Reference Atlas offers comprehensive APIs and exploration tools for mapping data across anatomical scales [16].

Specialized Algorithms: The "Triaction" algorithm implements information-theoretic detection of triadic interactions from gene expression data [16]. Variogram matching approaches generate surrogate maps for estimating spatial correlation significance, available through the brainsmash toolbox [10]. Hyperbolic embedding algorithms enable mapping of time-aggregated proximity networks into geometric spaces [15].

Reference Datasets: The Allen Human Brain Atlas provides comprehensive molecular data mapped to brain anatomy, enabling multi-scale integration [10]. The HuBMAP Human Reference Atlas offers a common coordinate framework for the healthy human body, with semantically annotated 3D representations of anatomical structures [16].

Applications in Physiology and Therapeutic Development

Basic Research Applications

Proximity networks enable fundamental advances in understanding physiological systems across scales:

Mapping Developmental Trajectories: Multiscale structural analysis reveals how brain organization matures from childhood to adolescence, with the expansion of the principal gradient space reflecting enhanced differentiation between primary sensory and higher-order transmodal regions [10]. This developmental reorganization correlates with cortical morphology maturation and underlies improvements in cognitive abilities such as working memory and attention [10].

Characterizing Disease Heterogeneity: Network-based stratification of Huntington's disease patients using allele-specific expression data reveals distinct molecular subtypes with potential implications for disease progression and treatment response [16]. Similar approaches have been applied to cancer, identifying molecularly distinct subgroups with prognostic significance.

Modeling Microbiome Ecology: Cross-feeding networks represent microbial communities as bipartite graphs linking consumers and resources, revealing tipping points in diversity that emerge from metabolic interdependencies [16]. Percolation theory applied to these networks explains discontinuous transitions in community diversity in response to structural changes.

Therapeutic Development and Precision Medicine

Proximity networks are transforming therapeutic development through multiple mechanisms:

Drug Target Identification: Protein-protein interaction networks enable systematic identification of therapeutic targets by pinpointing essential hubs or dysregulated modules in disease states. Network proximity measures can predict drug efficacy and repurposing opportunities by quantifying the proximity of drug targets to disease modules in the interactome.

Clinical Trial Optimization: The emergence of in silico clinical trials leverages computational models representative of clinical populations to simulate intervention effects across heterogeneous cohorts [17]. This approach accelerates therapeutic evaluation while reducing costs and ethical concerns associated with traditional trials.

Digital Twin Development: The vision has shifted from generating a universal human model to creating patient-specific models ("digital twins") that enable personalized prediction of treatment responses [17]. These models integrate individual clinical data with multiscale biological networks to simulate personalized physiological and therapeutic outcomes.

Mental Health Applications: The network theory of psychopathology conceptualizes mental disorders as networks of symptoms, with connectivity strength among symptoms potentially predicting treatment response and recovery timelines [16]. Weaker baseline connectivity correlates with greater subsequent improvement, suggesting network-based biomarkers of therapeutic plasticity.

Future Directions and Conceptual Challenges

The evolving field of biological proximity networks faces several important frontiers:

Integration of Mechanistic and Data-Driven Modeling: A key challenge involves bridging first-principles mechanistic models with pattern-recognizing data-driven approaches [17]. Mechanistic models provide generalizability and respect fundamental biological constraints, while data-driven models better capture empirical observations; their systematic integration represents a promising direction for future methodology development.

Handling Biological Variability: Moving from population-level models to individual predictions requires explicit consideration of inter-individual and intra-individual variability [17]. Virtual cohort studies that sample from distributions of model parameters can capture this heterogeneity, enabling more robust translation from basic research to clinical applications.

Standardization and Interoperability: Progress depends on developing open tools, data standards, and metadata frameworks that enable cross-study integration and replication [17]. Initiatives like the Human Reference Atlas exemplify this approach, creating common coordinate frameworks for mapping data across scales [16].

Temporal Network Analysis: Most current analyses focus on static network representations, but biological systems are inherently dynamic. Developing analytical frameworks for temporal proximity networks that capture both instantaneous relationships and their evolution over time represents an important frontier, with preliminary approaches showing promise in modeling epidemic spreading and social behavior [15].

As these challenges are addressed, proximity networks will increasingly serve as the foundational data structure for multiscale biological modeling, ultimately enabling more predictive, personalized, and effective therapeutic interventions across the spectrum of human disease.

Biological networks provide a powerful framework for understanding the complex interactions that govern human physiology. By representing biological entities as nodes and their relationships as edges, these networks enable researchers to move beyond a one-molecule-at-a-time approach to a systems-level perspective essential for comprehensive physiological research [18]. The visual representation and analysis of these networks have become challenging in their own right as underlying graph data grows ever larger and more complex, requiring collaboration between domain experts, bioinformaticians, and network scientists [18]. Within the context of multi-scale human physiology research, biological networks typically fall into three fundamental categories: physical interaction networks, which map direct molecular contacts; genetic interaction networks, which reveal functional relationships through phenotypic analysis; and functional interaction networks, which represent coordinated biological roles and pathways. Together, these network types form interconnected layers that span from molecular to organismal levels, providing the computational foundation for deciphering disease mechanisms and identifying therapeutic targets in drug development.

Physical Interaction Networks

Definition and Biological Significance

Physical interaction networks map direct physical contacts between biomolecules, providing a structural basis for understanding molecular complex formation and signal transduction mechanisms. The most prominent examples include Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks that catalog stable complexes and transient signaling connections, and Protein-DNA interaction networks that document transcription factor binding to genomic regulatory elements. These networks are foundational to mechanistic studies in physiology as they reveal the actual physical architecture of cellular machinery [5]. For drug development professionals, physical interaction networks offer crucial insights into drug target engagement, potential off-target effects, and the structural context of molecular function.

Key Experimental Methodologies

Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) Screening

The Yeast Two-Hybrid system is a powerful high-throughput method for detecting binary protein interactions through reconstitution of transcription factor activity in yeast cells.

Experimental Protocol:

- Construct Creation: Clone "bait" protein gene into DNA-Binding Domain (DBD) vector and "prey" protein gene into Activation Domain (AD) vector

- Yeast Transformation: Co-transform both constructs into appropriate yeast reporter strain (e.g., AH109 or Y187)

- Selection Plating: Plate transformed yeast on minimal media lacking specific nutrients (e.g., -Leu/-Trp) to select for successful transformants

- Interaction Screening: Transfer colonies to higher stringency selection plates (e.g., -Leu/-Trp/-His/-Ade) containing X-α-Gal for colorimetric detection

- Validation: Confirm positive interactions through β-galactosidase liquid assays and sequence analysis of prey plasmids

Affinity Purification-Mass Spectrometry (AP-MS)

AP-MS identifies protein complex components by purifying tagged bait proteins and their associated partners followed by mass spectrometric identification.

Experimental Protocol:

- Cell Lysis: Prepare native cell lysates from tissues or cell lines expressing tagged bait protein

- Affinity Purification: Incubate lysate with tag-specific affinity resin (e.g., anti-FLAG M2 agarose, glutathione sepharose for GST tags, nickel-NTA for His tags)

- Washing: Perform sequential washes with lysis buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins

- Elution: Competitively elute complexes using tag-specific peptides (FLAG peptide) or altering buffer conditions (reduced pH, high imidazole)

- Proteolytic Digestion: Digest eluted proteins with trypsin/Lys-C mixture

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Separate peptides by reverse-phase liquid chromatography and analyze by tandem mass spectrometry

- Data Processing: Identify proteins from fragmentation spectra using database search algorithms (MaxQuant, Proteome Discoverer) and apply statistical filters (SAINT, CompPASS) to distinguish specific interactions from background

Table 1: Quantitative Metrics for Physical Interaction Network Characterization

| Network Metric | Biological Interpretation | Typical Range | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree Distribution | Network robustness and hub identification | Power-law exponent (γ): 1.5-2.5 | P(k) ~ k^(-γ) |

| Betweenness Centrality | Essential bottleneck proteins in information flow | 0-1 (normalized) | Shortest paths through node |

| Clustering Coefficient | Modularity and functional complex formation | 0.4-0.8 (biological networks) | Triangle density around node |

| Network Diameter | Information propagation efficiency | 4-12 (cellular networks) | Longest shortest path |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Physical Interaction Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-FLAG M2 Agarose | Immunoaffinity purification of FLAG-tagged bait proteins | Sigma A2220, Thermo Fisher PI8823 |

| Streptavidin Magnetic Beads | Purification of biotinylated proteins and complexes | Pierce 88816, Dynabeads M-270 |

| Cross-linking Reagents | Stabilization of transient interactions (formaldehyde, DSS) | Pierce 22585 (DSS), Thermo 28906 (formaldehyde) |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Preservation of protein complex integrity during lysis | Roche 4693132001, Thermo 78430 |

| TMT/Isobaric Tags | Multiplexed quantitative proteomics | Thermo 90110 (TMT11-plex), 90406 (TMTpro-16) |

Genetic Interaction Networks

Definition and Biological Significance

Genetic interaction networks map functional relationships between genes by revealing how combinations of genetic perturbations produce unexpected phenotypes that deviate from single mutant predictions. These networks are categorized into several types: synthetic lethality (where two non-lethal mutations combined cause lethality), suppression (where one mutation reverses another's phenotype), and epistasis (where one mutation masks another's effect) [19]. In the context of multi-scale physiology, genetic interactions reveal functional redundancy, backup pathways, and compensatory mechanisms that maintain system robustness. For drug development, synthetic lethal interactions provide powerful opportunities for therapeutic targeting, particularly in oncology where cancer-specific vulnerabilities can be exploited while sparing healthy tissues.

Key Experimental Methodologies

Synthetic Genetic Array (SGA) Analysis

SGA automates yeast genetics to systematically construct double mutants and quantify genetic interactions across thousands of gene pairs.

Experimental Protocol:

- Query Strain Construction: Generate query strain with a deletion mutation marked by a selectable marker (e.g., kanMX)

- Arraying Procedure: Robotically pin query strain onto high-density array of ~5000 deletion mutant strains (the "array")

- Mating Phase: Incubate to allow mating between query and array strains on rich media (YPD)

- Diploid Selection: Transfer to minimal media selecting for diploids (e.g., -His/-Leu)

- Sporulation Induction: Transfer to nitrogen-deficient media to induce meiosis and sporulation

- Haploid Selection: Transfer to media containing canavanine and thialysine to select for haploid double mutants

- Phenotypic Scoring: Measure colony size as fitness proxy after 48-72 hours growth

- Interaction Scoring: Calculate genetic interaction scores (ε) from observed vs. expected double mutant fitness

CRISPR-Based Genetic Interaction Screening

CRISPR-mediated gene knockout or inhibition enables genetic interaction mapping in mammalian cells with single-guide RNA (sgRNA) libraries.

Experimental Protocol:

- Library Design: Design sgRNA pairs targeting gene combinations (typically 3-10 sgRNAs per gene)

- Lentiviral Production: Package sgRNA library in lentiviral particles at low MOI (<0.3) to ensure single infection

- Cell Infection: Transduce target cells (e.g., cancer cell lines) and select with puromycin for 48-72 hours

- Time Points Collection: Harvest cells at initial (T0) and final (Tend) time points (typically 14-21 population doublings)

- Sequencing Library Prep: Amplify integrated sgRNA sequences with barcoded primers

- Next-Generation Sequencing: Sequence sgRNA representation on Illumina platform (minimum 500x coverage)

- Differential Abundance Analysis: Calculate sgRNA fold-changes between T0 and Tend using MAGeCK or BAGEL algorithms

- Interaction Scoring: Compute genetic interaction scores from differential fitness effects

Table 3: Quantitative Analysis of Genetic Interactions

| Interaction Type | Statistical Measure | Threshold Values | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Lethality | z-score (fitness defect) | ε ≤ -2.0, FDR < 0.05 | Essential backup or parallel pathway |

| Suppression | z-score (fitness increase) | ε ≥ 2.0, FDR < 0.05 | Compensatory mechanism or pathway bypass |

| Positive Interaction | S-score (positive) | ε > 0.08, p < 0.05 | Bufferring relationship or redundancy |

| Negative Interaction | S-score (negative) | ε < -0.08, p < 0.05 | Synergistic fitness defect |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Genetic Interaction Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| Yeast Deletion Collection | Comprehensive array of ~5000 non-essential gene knockouts | Thermo Fisher YSC1053 |

| CRISPR sgRNA Libraries | Pooled guides for combinatorial gene knockout | Addgene 1000000096 (Human), 1000000121 (Mouse) |

| Lentiviral Packaging Plasmids | Production of sgRNA lentiviral particles | Addgene 8453 (psPAX2), 12260 (pMD2.G) |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Kits | sgRNA representation quantification | Illumina 15048964 (NovaSeq), 20020490 (MiSeq) |

| Cell Viability Assays | High-throughput fitness measurement | Promega G7571 (CellTiter-Glo), Abcam ab228563 (MTT) |

Functional Interaction Networks

Definition and Biological Significance

Functional interaction networks represent biochemical relationships and coordinated biological roles between biomolecules, often inferred from multiple data types rather than direct physical measurement. These networks include metabolic pathways that map enzyme-substrate relationships, signaling pathways that document information flow from receptor to cellular response, and gene co-expression networks that reveal transcriptional programs [19]. Unlike physical networks, functional networks capture indirect relationships and membership in common processes, making them particularly valuable for understanding system-level properties in human physiology. For researchers investigating complex diseases, functional networks provide the conceptual framework for understanding how molecular perturbations propagate through biological systems to produce phenotypic outcomes, thereby identifying potential intervention points for therapeutic development.

Network Construction Methodologies

Gene Co-expression Network Analysis

Gene co-expression networks infer functional relationships based on transcriptional coordination across diverse conditions using correlation metrics.

Computational Protocol:

- Expression Matrix Compilation: Collect RNA-seq or microarray data from large compendium of diverse conditions (minimum 50-100 samples)

- Data Preprocessing: Apply normalization (RPKM/TPM for RNA-seq, RMA for microarrays) and batch effect correction (ComBat)

- Correlation Calculation: Compute pairwise correlation between all gene pairs using Pearson, Spearman, or biweight midcorrelation

- Adjacency Matrix Construction: Transform correlation matrix to adjacency matrix using signed or unsigned network with power law transformation (β = 6-12)

- Topological Overlap Matrix: Calculate TOM to assess network interconnectedness while dampening spurious connections

- Module Detection: Identify co-expression modules using hierarchical clustering with dynamic tree cut (minClusterSize = 30)

- Module Functional Annotation: Enrichment analysis (GO, KEGG) using Fisher's exact test with FDR correction

- Hub Gene Identification: Calculate module membership (eigengene-based connectivity) and intramodular connectivity

Signaling Pathway Reconstruction

Signaling networks map information flow from extracellular stimuli to intracellular responses using curated knowledge and phosphoproteomics data.

Computational Protocol:

- Literature Curation: Extract known signaling relationships from pathway databases (KEGG, Reactome, WikiPathways)

- Phosphoproteomics Integration: Map time-resolved phosphosite data to identify regulated signaling events

- Network Enrichment: Apply PHONEMeS or KiNNeX algorithms to infer context-specific signaling topologies

- Boolean Network Modeling: Represent pathway as logical rules where nodes are ON/OFF based on input states

- Model Perturbation: Simulate knockout/knockdown experiments to predict signaling outcomes

- Experimental Validation: Test predictions using targeted phospho-flow cytometry or Western blotting

Table 5: Quantitative Parameters for Functional Network Analysis

| Analysis Type | Key Parameters | Typical Values | Computational Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-expression Networks | Soft threshold power, TOM similarity, Module min size | β = 6-12, TOM > 0.15, minSize = 30 | WGCNA, CEMiTool |

| Signaling Networks | Edge confidence score, Conservation score, Perturbation effect | 0-1 confidence, >0.6 conserved | PHONEMeS, CytoKinate |

| Metabolic Networks | Reaction flux, Enzyme capacity, Thermodynamic constraints | 0-100 mmol/gDW/h, Keq values | COBRApy, MetaboAnalyst |

| Pathway Enrichment | Odds ratio, FDR correction, Minimum gene set | OR > 2, FDR < 0.05, min=5 | GSEA, clusterProfiler |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 6: Essential Research Reagents for Functional Network Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Sequencing Kits | Transcriptome profiling for co-expression networks | Illumina 20040859 (NovaSeq), Thermo Fisher 18091164 (Ion Torrent) |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Signaling network validation by Western/flow | CST 9018S (p-Akt Ser473), 4370S (p-p44/42 Thr202/Tyr204) |

| Pathway Reporters | Live-cell signaling dynamics monitoring | Promega CS193A1 (NF-κB), N2081 (AP-1) |

| Metabolomics Standards | Quantitative metabolic network analysis | Cambridge Isotopes CLM-1577 (13C-glucose), IROA Technologies 300100 (MS standards) |

Integrated Multi-Scale Network Analysis in Physiology

Network Alignment and Comparison Methods

The integration of physical, genetic, and functional networks requires sophisticated alignment techniques that map corresponding nodes and pathways across different network layers and biological contexts. Probabilistic network alignment approaches address this challenge by formulating alignment as an inference problem where observed networks are considered noisy copies of an underlying blueprint network [20]. This method enables researchers to simultaneously align multiple networks while quantifying uncertainty through posterior distributions over possible alignments, which proves particularly valuable when single optimal alignments may be misleading. For physiology research, these techniques enable cross-species comparisons to identify conserved functional modules, alignment of networks from different physiological states to pinpoint disease-associated rewiring, and integration of multi-omic networks to create unified models of physiological processes.

Visualization Strategies for Multi-Scale Networks

Effective visualization is essential for interpreting complex biological networks, with layout choice heavily dependent on network properties and research questions. While node-link diagrams remain most common for their intuitive representation of relationships, adjacency matrices offer advantages for dense networks by eliminating edge clutter and enabling clear visualization of edge attributes [5]. For multi-scale physiology research, effective visualization requires adhering to key principles: determining figure purpose before creation to ensure visual elements support the intended message; providing readable labels and captions with sufficient font size; using color strategically to represent attributes while ensuring accessibility; and applying layering and separation to reduce visual complexity [5]. These strategies become particularly important when visualizing how perturbations at molecular network levels propagate through physiological systems to impact tissue and organ function.

Applications in Drug Development

Biological network analysis has transformed target identification and validation in pharmaceutical research by contextualizing individual targets within their network environments. Genetic interaction networks identify synthetic lethal partners for precision oncology approaches, while physical interaction networks reveal drug target complexes and potential off-target effects. Functional networks enable prediction of system-wide responses to therapeutic intervention and identification of biomarkers for patient stratification. The integration of these network types creates comprehensive models that predict both efficacy and adverse effects by accounting for network robustness and bypass mechanisms, ultimately increasing clinical success rates through more informed target selection.

Computational Frameworks and Clinical Applications in Multi-Scale Modeling

In the study of complex multi-scale biological networks, researchers primarily employ two contrasting philosophical approaches: bottom-up and top-down modeling. These paradigms form the foundation for investigating human physiology, from molecular interactions to whole-organism functions. The bottom-up approach models a system by directly simulating its individual components and their interactions to elucidate emergent system behaviors [21]. Conversely, the top-down approach considers the system as a whole, using macroscopic behaviors as variables to model system dynamics based primarily on experimental observations [21]. The fundamental distinction lies in their starting points: bottom-up begins with detailed elemental attributes, while top-down initiates from high-level business entities or strategic objectives [22].

These approaches are particularly relevant in the framework of multi-scale biological systems, where regulation occurs across many orders of magnitude in space and time—spanning from molecular scales (10⁻¹⁰ m) to entire organisms (1 m), and temporally from nanoseconds to years [21]. Biological systems inherently exhibit a hierarchical structure where genes encode proteins, proteins form organelles and cells, and cells constitute tissues and organs, with feedback loops operating across these scales [21]. This complex integration presents significant challenges for both experimental interpretation and mathematical modeling, necessitating sophisticated approaches that can bridge these scales effectively.

Conceptual Foundations and Theoretical Frameworks

The Bottom-Up Approach

The bottom-up approach in systems biology aims to construct detailed models that can be simulated under diverse physiological conditions. This methodology combines all organism-specific information into a complete genome-scale metabolic reconstruction [23]. The process typically involves several key phases: draft reconstruction of metabolic networks, manual curation to refine the model, mathematical network reconstruction, and finally validation of these models through rigorous literature analysis (bibliomics) [23].

A prime example of bottom-up modeling is the development of genome-scale metabolic reconstructions, which began with the first comprehensive reconstruction of Haemophilus influenza in 1999 [23]. This approach has since expanded dramatically, with reconstructions now available for numerous organisms ranging from bacteria and archaea to multicellular eukaryotes [23]. These reconstructions are often assembled into structured knowledgebases like BiGG (Biochemically, Genetically, and Genomically structured), which collaborate with computational tools such as the COBRA (Constraint Based Reconstruction and Analysis) toolbox to facilitate comprehensive metabolic network analysis [23].

The Top-Down Approach

In contrast, the top-down approach utilizes metabolic network reconstructions that leverage 'omics' data (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics) generated through high-throughput genomic techniques like DNA microarrays and RNA-Seq [23]. This methodology applies appropriate statistical and bioinformatics methodologies to process data from omics levels down to pathways and individual genes [23]. Rather than building from first principles, top-down modeling typically begins with observed clinical data to derive system characteristics, often employing empirical models with scope limited to the range of input data [24].

In practice, top-down approaches are frequently used in pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling, where researchers analyze quantitative relationships between drug exposure and physiological responses [24]. For example, in cardiac safety assessment, top-down models establish exposure-response relationships for QT interval prolongation based on clinical observations from thorough QT/QTc studies [24]. These models often utilize statistical approaches like linear mixed-effects models to describe relationships between drug concentrations and observed effects [24].

The Emerging Middle-Out Strategy

A hybrid methodology, the middle-out approach, combines elements of both bottom-up and top-down strategies [24]. This approach leverages bottom-up mechanistic models while utilizing available in vivo information to determine unknown or uncertain parameters [24]. Middle-out modeling is particularly valuable in drug development, where it integrates physiological knowledge with clinical observations to create more robust predictive models [24]. This strategy acknowledges that purely mechanistic models may lack necessary clinical relevance, while entirely empirical models may fail to provide sufficient physiological insight for extrapolation beyond observed conditions.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Modeling Approaches

| Characteristic | Bottom-Up Approach | Top-Down Approach | Middle-Out Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Basic components/elements | System as a whole | Intermediate level of organization |

| Data Foundation | First principles, mechanistic knowledge | Observed empirical data | Combination of mechanistic knowledge and empirical data |

| Model Structure | Built from component interactions | Derived from system behavior | Calibrated mechanistic framework |

| Primary Strength | Predictive for emergent properties | Directly reflects observed system behavior | Balances prediction with empirical validation |

| Key Limitation | Computationally intensive, potentially infeasible for complex systems | Limited extrapolation beyond observed conditions | Requires careful parameterization |

Methodological Implementation and Workflows

Bottom-Up Modeling Methodology

The implementation of bottom-up modeling follows a systematic workflow that emphasizes mechanistic completeness. The draft reconstruction phase involves compiling all known metabolic reactions for an organism based on genomic annotation and biochemical databases [23]. This is followed by manual curation, where domain experts refine the model by verifying reaction stoichiometry, cofactor usage, and mass balance through extensive literature review [23].

The mathematical reconstruction phase translates the biochemical network into a computational format using constraint-based modeling approaches [23]. The COBRA toolbox has become a standard computational resource for this purpose, performing flux-balance analysis (FBA) to define metabolic behavior of substrates and products within a solution space context [23]. This toolbox includes functions for network gap filling, 13C analysis, metabolic engineering, omics-guided analysis, and visualization [23].

Finally, the validation phase tests model predictions against experimental data, with iterative refinement improving model accuracy and predictive capability [23]. For multicellular organisms, this process may extend to tissue-specific reconstructions that account for metabolic specialization across different cell types [23].

Diagram 1: Bottom-up modeling workflow for metabolic networks

Top-Down Modeling Methodology

Top-down modeling employs a contrasting workflow that begins with system-level observations. The process typically initiates with data acquisition from high-throughput experimental techniques such as microarrays, RNA-Seq, proteomics, or metabolomics [23]. For pharmaceutical applications, this often involves clinical data from intervention studies, such as thorough QT/QTc studies in cardiac safety assessment [24].

The data processing phase applies statistical and bioinformatics methods to extract meaningful patterns from complex datasets [23]. This may include normalization procedures, dimensionality reduction techniques, and identification of correlated variables or response patterns [24]. In pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling, this phase establishes quantitative relationships between drug exposure metrics and observed physiological responses [24].

The model development phase constructs mathematical representations that describe system behavior, often employing statistical models like linear mixed-effects models, analysis of variance (ANOVA), or analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) [24]. These models aim to capture central tendencies in the data while accounting for covariates and random effects that influence system behavior [24].

Finally, model application uses the derived relationships to predict system behavior under new conditions, inform decision-making, or guide further experimental design [24]. Throughout this process, model scope remains constrained by the range of available observational data.

Diagram 2: Top-down modeling methodology for biological systems

Multi-Scale Integration Strategies

Multi-scale modeling represents a sophisticated approach that bridges different biological hierarchies. The fundamental challenge lies in appropriately representing dynamical behaviors of a high-dimensional model from a lower scale by a low-dimensional model at a higher scale [21]. This process enables information from molecular levels to propagate effectively to cellular, tissue, and organ levels.

A successful multi-scale framework typically employs different mathematical representations at different biological scales [21]. For example, Markovian transitions may simulate stochastic opening and closing of single ion channels, ordinary differential equations (ODEs) model action potentials and whole-cell calcium transients, while partial differential equations (PDEs) describe electrical wave conduction in tissue and heart [21]. The key requirement is that models at different scales exhibit consistent behaviors, with low-dimensional representations accurately capturing essential dynamics of more detailed systems [21].

Table 2: Multi-Scale Modeling in Biological Systems

| Biological Scale | Typical Modeling Approach | Key Applications | Technical Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular (10⁻¹⁰ m) | Molecular dynamics, Markov models | Ion channel gating, protein folding | Computational intensity, parameter estimation |

| Cellular (10⁻⁶ m) | Ordinary differential equations, Stochastic simulations | Metabolic networks, signal transduction | Scalability, managing combinatorial complexity |

| Tissue (10⁻³ m) | Partial differential equations, Agent-based models | Cardiac electrophysiology, neural networks | Spatial discretization, intercellular coupling |

| Organ (10⁻¹ m) | Lumped parameter models, Finite element methods | Whole-heart dynamics, organ metabolism | Heterogeneity, integration of multiple cell types |

| Organism (1 m) | Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic models | Drug disposition, systemic responses | Data integration, computational resources |

Applications in Drug Development and Safety Assessment

Cardiac Safety Assessment

The assessment of cardiac safety represents a critical application of modeling approaches in pharmaceutical development. Drug-induced arrhythmias, particularly torsades de pointes, remain a significant concern causing early termination of drug candidates at various development stages [24]. The current screening paradigm focuses heavily on hERG channel inhibition but generates substantial false positives, unnecessarily constricting development pipelines [24].

Bottom-up approaches in cardiac safety utilize biophysically detailed cardiac myocyte models that incorporate descriptions of multiple ion channels beyond hERG, including fast sodium channels, persistent sodium channels, calcium channels, and additional potassium channels [24]. These models enable comprehensive assessment of how drug effects on specific channels translate to changes in action potential morphology and duration [24]. The Comprehensive In vitro Proarrhythmia Assay (CIPA) initiative exemplifies this approach, seeking to modernize cardiac safety screening by integrating information across multiple ion channels [24].

Top-down approaches in cardiac safety predominantly rely on clinical data from thorough QT/QTc studies [24]. These studies analyze central tendency of QTc intervals, categorical outcomes, and exposure-response relationships using statistical models including analysis of variance, mixed-effects models, and linear concentration-effect relationships [24]. Regulatory decisions often incorporate these models when evaluating whether drugs exceed the threshold of concern (5 ms QTc prolongation with upper confidence bound exceeding 10 ms) [24].

Metabolic Network Analysis

In metabolic research, bottom-up and top-down approaches enable comprehensive investigation of physiological processes. Bottom-up metabolic reconstructions have been developed for various organisms, from unicellular bacteria and yeast to multicellular organisms including mice and humans [23]. These reconstructions facilitate simulation of metabolic capabilities under different nutritional or genetic conditions [23].

Top-down metabolic analysis leverages omics data to infer metabolic activity states. For example, in ruminant nutrition research, top-down approaches analyze transcriptomic and proteomic data to understand metabolic processes in context of nutrition [23]. Tissue-specific reconstructions for liver and adipose tissue in cattle demonstrate how top-down methods can enhance understanding of productive efficiency [23].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Multi-Scale Modeling

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Modeling Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Omics Technologies | DNA microarrays, RNA-Seq, Mass spectrometry | Generate high-throughput molecular data for network reconstruction | Top-down approach, data-driven modeling |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Heterologous cell lines expressing ion channels, Stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes | Provide experimental data on specific biological components | Bottom-up parameterization, middle-out validation |

| Computational Toolboxes | COBRA toolbox, BiGG knowledgebase | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis of metabolic networks | Bottom-up metabolic modeling |

| Ion Channel Screening | Automated patch-clamp systems, Voltage-sensitive dyes | High-throughput assessment of ion channel function | Cardiac safety applications, CIPA initiative |

| Statistical Software | R, Python scikit-learn, NONMEM | Implementation of mixed-effects models, exposure-response analysis | Top-down PK/PD modeling, population analysis |

| Mathematical Frameworks | Ordinary differential equations, Partial differential equations, Markov models | Represent biological processes at different scales | Multi-scale model integration |

Comparative Analysis and Strategic Implementation

Performance Characteristics and Limitations

Both bottom-up and top-down approaches present distinct advantages and limitations. Bottom-up modeling offers adaptability and robustness for studying emergent properties of systems with large numbers of interacting elements [21]. However, this approach becomes computationally intensive, often prohibitively so, and resulting models can become too complicated for practical application or intuitive understanding [21].