Multi-Omics Data Integration Frameworks: A Comprehensive Guide for Complex Disease Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of multi-omics data integration frameworks and their pivotal role in deciphering complex diseases.

Multi-Omics Data Integration Frameworks: A Comprehensive Guide for Complex Disease Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of multi-omics data integration frameworks and their pivotal role in deciphering complex diseases. It explores the foundational principles of multi-omics layers—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—and details advanced computational methodologies, including machine learning and AI-driven tools like Flexynesis. The content addresses critical challenges in data harmonization, interpretation, and clinical translation, while offering comparative analyses of popular frameworks such as MOFA, DIABLO, and SNF. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current trends, real-world applications, and future directions to empower precision medicine initiatives and accelerate therapeutic discovery.

The Multi-Omics Landscape: Core Concepts and Biological Workflows for Complex Diseases

The advent of high-throughput technologies has revolutionized biomedical research, enabling the comprehensive profiling of biological systems across multiple molecular layers—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics [1]. This multi-dimensional data, collectively termed "multi-omics," provides an unprecedented opportunity to move beyond reductionist views and adopt a holistic, systems-level understanding of biology and disease pathogenesis [2]. Multi-omics integration is the computational and statistical synthesis of these disparate data types to construct a more complete and causal model of biological processes [3]. For complex, multifactorial diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative disorders, this integrative approach is particularly powerful, as it can unravel the myriad molecular interactions that single-omics analyses might miss [1]. Framed within a thesis on data integration frameworks for complex disease research, this document serves as a detailed application note and protocol, outlining the methodologies, tools, and practical applications of multi-omics integration for researchers and drug development professionals.

Foundational Methods and Data Integration Strategies

Integrating multi-omics data presents significant computational challenges due to high dimensionality, heterogeneity, and technical noise across platforms [1]. The choice of integration strategy is pivotal and depends fundamentally on the experimental design and data structure.

Types of Integration

A primary distinction is made based on whether data from different omics layers are derived from the same biological unit (e.g., the same cell or sample).

- Vertical (Matched) Integration: This approach merges data from different omics modalities (e.g., RNA and protein) measured within the same set of cells or samples. The cell or sample itself serves as the anchor for integration [3]. This is the ideal scenario for understanding direct molecular relationships within a biological unit.

- Diagonal (Unmatched) Integration: This more challenging form integrates different omics data measured in different sets of cells or samples. Since a common biological anchor is absent, computational methods must project data into a co-embedded space to find latent commonalities [3].

- Mosaic Integration: A specialized strategy used when experimental designs feature various combinations of omics across samples. If sufficient overlap exists (e.g., some samples have RNA+Protein, others have RNA+Epigenomics), tools can integrate across all modalities by leveraging the shared data types [3].

Computational Methodologies

A diverse array of computational tools has been developed to tackle these integration paradigms. The underlying methodologies can be broadly categorized as follows [3]:

- Matrix Factorization (e.g., MOFA+): Decomposes high-dimensional data into lower-dimensional latent factors that capture shared and specific variations across omics types.

- Manifold Alignment (e.g., UnionCom, Pamona): Aligns datasets by preserving the intrinsic geometric structure (manifold) of each omics layer.

- Deep Learning (e.g., Variational Autoencoders, DCCA): Uses neural networks to learn non-linear, lower-dimensional representations that integrate multiple modalities.

- Network-Based Methods (e.g., citeFUSE, Seurat): Constructs graphs or networks where nodes represent biological features or samples, and edges represent relationships, facilitating integration in the network space.

- Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) & Nearest Neighbor Methods (e.g., Seurat v3): Identify linear relationships between datasets or find similar cells across modalities for alignment.

Table 1: Selected Multi-Omics Integration Tools and Their Characteristics [3]

| Tool Name | Year | Primary Methodology | Integration Capacity (Modalities) | Integration Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOFA+ | 2020 | Factor Analysis | mRNA, DNA methylation, chromatin accessibility | Matched |

| totalVI | 2020 | Deep Generative Model | mRNA, protein | Matched |

| Seurat v4/v5 | 2020/2022 | Weighted Nearest-Neighbour / Bridge Integration | mRNA, protein, chromatin accessibility, spatial | Matched & Unmatched |

| GLUE | 2022 | Graph-Linked Variational Autoencoder | Chromatin accessibility, DNA methylation, mRNA | Unmatched |

| Cobolt | 2021 | Multimodal Variational Autoencoder | mRNA, chromatin accessibility | Mosaic |

| Pamona | 2021 | Manifold Alignment | mRNA, chromatin accessibility | Unmatched |

Key Public Data Repositories

Leveraging existing, well-curated multi-omics datasets is crucial for method development and validation. Several major repositories provide such resources, primarily in oncology [2].

Table 2: Major Public Repositories for Multi-Omics Data [2]

| Repository | Primary Focus | Key Omics Data Types Available |

|---|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Pan-Cancer | RNA-Seq, DNA-Seq, miRNA-Seq, SNV/CNV, DNA Methylation, RPPA (Proteomics via CPTAC) |

| International Cancer Genomics Consortium (ICGC) | Pan-Cancer | Whole Genome Sequencing, Somatic/Germline Mutations |

| Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) | Cancer Cell Lines | Gene Expression, Copy Number, Sequencing, Pharmacological Profiles |

| Molecular Taxonomy of Breast Cancer (METABRIC) | Breast Cancer | Gene Expression, SNP, CNV, Clinical Data |

| Omics Discovery Index (OmicsDI) | Consolidated Multi-Disease | Genomics, Transcriptomics, Proteomics, Metabolomics from 11+ sources |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: A Framework for Complex Disease Analysis

The following protocol outlines a robust, multi-stage analytical framework for integrating multi-omics data to elucidate disease mechanisms, as exemplified in a study on Methylmalonic Aciduria (MMA) [4]. This framework combines quantitative trait locus analysis, correlation network construction, and enrichment analyses.

Protocol Title: Integrative Multi-Omics Analysis for Disease Mechanism Prioritization

Objective: To identify and prioritize dysregulated molecular pathways in a complex disease by accumulating evidence from genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data layers.

Input Data Requirements:

- Genomics: Whole Genome or Exome Sequencing data (VCF format) for patients and controls.

- Transcriptomics: RNA-Sequencing count or FPKM/TPM matrix.

- Proteomics: Quantitative protein abundance matrix (e.g., from DIA/SWATH-MS).

- Metabolomics: Quantitative metabolite abundance profile.

- Clinical Phenotype: Vector of disease severity or relevant clinical endpoint for the cohort.

Experimental Workflow:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Step 1: Protein Quantitative Trait Loci (pQTL) Analysis

- Objective: Map genetic variants that influence protein abundance levels.

- Procedure:

- Quality Control: Filter genetic variants (SNPs) for call rate >95% and minor allele frequency (MAF) >1%. Normalize protein abundance data (e.g., log2 transformation, quantile normalization).

- Association Testing: For each protein-SNP pair, perform a linear regression (or linear mixed model to account for population structure):

Protein_abundance ~ Genotype + Covariates. Covariates typically include age, sex, and principal components of genetic variation. - Significance Thresholding: Apply a genome-wide significance threshold (e.g., p < 5e-8). Identify cis-pQTLs (SNP within 1 Mb of the protein-coding gene) and trans-pQTLs.

- Pathway Enrichment: Perform over-representation analysis (ORA) or gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) on the genes corresponding to proteins with significant pQTLs using databases like REACTOME or KEGG [4].

Step 2: Multi-Omic Correlation Network Analysis

- Objective: Identify highly correlated modules of proteins and metabolites that may represent functional units.

- Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Merge normalized proteomics and metabolomics matrices. Filter features with excessive missing values.

- Network Construction: Calculate a pairwise correlation matrix (e.g., using Spearman or Pearson correlation) between all proteins and metabolites.

- Module Detection: Use a network clustering algorithm (e.g., the blockwiseModules function in WGCNA) to group features into modules based on topological overlap. Each module is assigned a color label (e.g., MEblue, MEbrown) [4].

- Module Trait Association (Step 3): Correlate the first principal component (module eigengene) of each module with the clinical trait of interest (e.g., disease severity). Identify modules with significant eigengene-trait correlations (p < 0.05).

Step 4 & 5: Transcriptomic Validation via GSEA and TF Analysis

- Objective: Corroborate findings from proteomic/metabolomic layers at the transcriptomic level and identify upstream regulators.

- Procedure for GSEA:

- Rank all genes based on their differential expression correlation with the phenotype.

- Run pre-ranked GSEA using molecular pathways from MSigDB or REACTOME to see if pathways identified in Steps 1 & 2 are also enriched at the transcript level [4].

- Procedure for TF Enrichment:

- Use tools like ChEA3 or Enrichr to test if the promoters of genes from significant modules or pathways are enriched for binding sites of specific transcription factors [4].

Step 6: Cross-Layer Evidence Integration

- Objective: Synthesize findings to prioritize high-confidence mechanisms.

- Procedure: Manually or algorithmically evaluate the concordance of evidence. For example, a pathway like "Glutathione Metabolism" is prioritized if it is: (a) enriched among pQTL-linked proteins, (b) central to a proteome-metabolome module strongly associated with disease severity, and (c) significantly enriched in GSEA of transcriptomic data [4].

Application in Complex Disease Research: A Case Study

This integrative framework is powerfully demonstrated in research on Methylmalonic Aciduria (MMA), a rare metabolic disorder with a poorly understood pathogenesis [4].

Application Workflow: Methylmalonic Aciduria (MMA) Case Study [4]

Key Insight: The integration of evidence across all omics layers converged on glutathione metabolism as a central disrupted pathway in MMA, a finding that was not apparent from any single data type alone. The network analysis further implicated compromised lysosomal function [4]. This systems-level understanding provides new actionable targets for therapeutic investigation and biomarker development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful multi-omics studies rely on both biological and computational reagents. Below is a list of essential solutions and platforms used in the field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Integration

| Category | Item / Platform | Function in Multi-Omics Research |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial Analysis Platforms | Metabolon's Multiomics Tool (in IBP) | A unified bioinformatics platform for uploading, integrating, and analyzing multi-omics data. It features predictive modelling (Logistic Regression, Random Forest), latent factor analysis (DIABLO), and REACTOME-based pathway enrichment [5]. |

| DNAnexus Platform | A cloud-based data management and analysis platform designed to centralize, process, and collaborate on multi-omics, imaging, and phenotypic data, enabling scalable and reproducible workflows [6]. | |

| Core Analytical Algorithms | DIABLO (Data Integration Analysis for Biomarker discovery using Latent cOmponents) | A multivariate method used to identify correlated features (latent components) across multiple omics datasets that best discriminate between sample groups (e.g., disease vs. control), ideal for biomarker discovery [5]. |

| Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) | A widely used R package for constructing correlation networks from omics data, identifying modules of highly correlated features, and relating them to clinical traits [4]. | |

| Critical Reference Databases | REACTOME | A curated, peer-reviewed database of biological pathways and processes. Used for functional interpretation via over-representation or pathway activity score analysis of multi-omics results [5] [4]. |

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | A primary public repository providing matched multi-omics data across numerous cancer types, serving as an essential benchmark and training resource for method development and validation [2]. | |

| Experimental Reagents (Example) | iRT (Indexed Retention Time) Peptides (e.g., from Biognosys) | Synthetic peptides spiked into proteomics samples to enable highly consistent and accurate retention time alignment across liquid chromatography runs, a critical step for reproducible quantitative proteomics in a multi-omics pipeline [4]. |

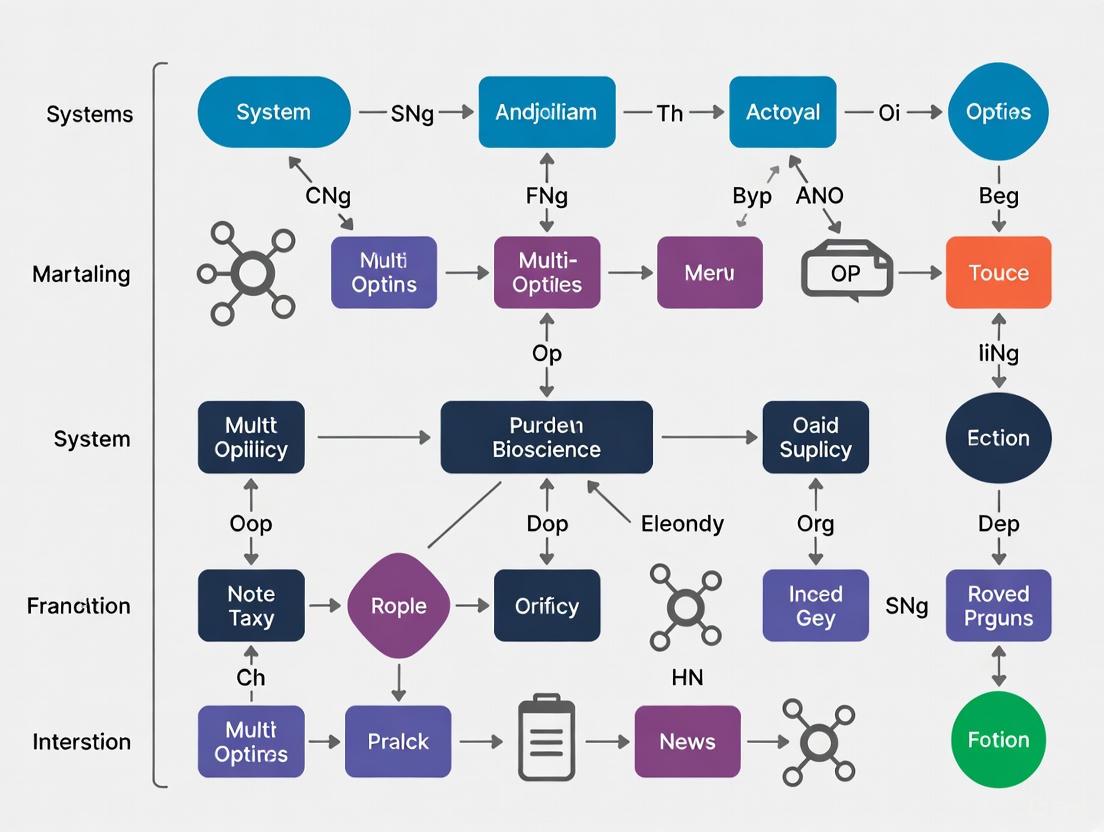

Visualization of a Key Identified Pathway

Based on the MMA case study findings, the following diagram illustrates the glutathione metabolism pathway, a central mechanism highlighted by the integrative analysis [4].

Multi-omics integration represents the forefront of systems biology, providing a powerful framework to decode the complexity of biological systems and disease [1]. By moving beyond single-layer analyses, it enables the identification of coherent biological narratives—such as the role of glutathione metabolism in MMA—that are substantiated by convergent evidence across molecular layers [4]. The field is supported by a growing arsenal of computational methods for matched, unmatched, and mosaic integration [3], accessible public data resources [2], and emerging commercial platforms that streamline the analytical process [5] [6].

For the broader thesis on frameworks for complex disease research, this integrative approach is not merely an analytical option but a necessity. It directly addresses the polygenic and multifactorial nature of diseases by mapping the interconnected web of genomic variation, regulatory changes, protein activity, and metabolic flux. Future developments will likely focus on improving the scalability of methods for single-cell and spatial multi-omics, standardizing data integration protocols, and incorporating machine learning to predict emergent phenotypes from integrated molecular signatures. As these frameworks mature, they will increasingly guide the discovery of robust biomarkers, the stratification of patient populations, and the identification of novel therapeutic targets, ultimately paving the way for more precise and effective medicine.

Multi-omics integration represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research, moving beyond single-layer analyses to provide a comprehensive view of biological systems [1]. The analysis and integration of datasets across multiple omics layers—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—provides global insights into biological processes and holds great promise in elucidating the myriad molecular interactions associated with complex human diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative disorders [1] [7]. These technologies enable researchers to collect large-scale datasets that, when integrated, can reveal underlying pathogenic changes, filter novel associations between biomolecules and disease phenotypes, and establish detailed biomarkers for disease [7]. However, integrating multi-omics data presents significant challenges due to high dimensionality, heterogeneity, and the complexity of biological systems [1] [8]. This article outlines the key omics layers and their integrated application in complex disease research, providing methodological guidance and practical frameworks for researchers.

Core Omics Technologies: Methods and Applications

Genomics

Genomics involves the application of omics to entire genomes, aiming to characterize and quantify all genes of an organism and uncover their interrelationships and influence on the organism [7]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) represent a typical application of genomics, screening millions of genetic variants across genomes to identify disease-associated susceptibility genes and biological pathways [7]. Key technologies include genotyping arrays, third-generation sequencing for whole-genome sequencing, and exome sequencing [7]. While genomics can identify novel disease-associated variants, most acquired variants have no direct biological relevance to disease, necessitating integration with other omics layers for functional validation [7].

Transcriptomics

Transcriptomics studies the expression of all RNAs from a given cell population, offering a global perspective on molecular dynamic changes induced by environmental factors or pathogenic agents [7]. The transcriptome includes protein-coding RNAs (mRNAs), long noncoding RNAs, short noncoding RNAs (microRNAs, small-interfering RNAs, etc.), and circular RNAs [7]. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) represents the primary technology for transcriptomic analysis, with single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) emerging as a powerful approach for detecting transcripts of specific cell types in diseases such as cancer and Alzheimer's disease [7]. Notably, noncoding RNAs have demonstrated significant associations with various diseases, including diabetes and cancer [7].

Proteomics

Proteomics enables the identification and quantification of all proteins in cells or tissues, providing direct functional information about cellular states [7]. Since RNA analysis often lacks correlation with protein expression due to post-transcriptional modifications, proteomics offers a more accurate reflection of functional cellular activities [7]. Mass spectrometry-based methods represent the most widely used approach, including stable isotope labeling proteomics and label-free proteomics [7]. Critically, post-translational modifications—including phosphorylation, glycosylation, ubiquitination, and acetylation—play crucial roles in intracellular signal transduction, protein transport, and enzyme activity, with specialized analyses (e.g., phosphoproteomics) uncovering novel mechanisms in type 2 diabetes, Alzheimer's disease, and various cancers [7].

Metabolomics

Metabolomics focuses on studying small molecule metabolites derived from cellular biological metabolic processes, including carbohydrates, fatty acids, and amino acids [7]. As immediate reflections of cellular physiology, metabolite levels can immediately reflect dynamic changes in cell state, with abnormal metabolite levels or ratios potentially inducing disease [7]. Metabolomics encompasses both untargeted and targeted approaches and demonstrates quantifiable correlations with other omics layers, such as predicting metabolite levels from mRNA counts or correlating gut bacteria with amino acid levels [7].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Omics Technologies

| Omics Layer | Analytical Focus | Key Technologies | Primary Applications | Notable Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA sequences and variations | Genotyping arrays, WGS, WES | GWAS, variant discovery | Identifies hereditary factors and disease predisposition |

| Transcriptomics | RNA expression patterns | RNA-seq, scRNA-seq | Gene regulation studies, biomarker discovery | Reveals active cellular processes and regulatory mechanisms |

| Proteomics | Protein expression and modifications | Mass spectrometry, protein arrays | Functional pathway analysis, drug target identification | Direct measurement of functional effectors |

| Metabolomics | Small molecule metabolites | MS and NMR spectroscopy | Metabolic pathway analysis, diagnostic biomarkers | Closest reflection of phenotypic state |

Integrated Multi-Omics Analysis

Data Integration Strategies

Integrating multiple omics datasets is crucial for achieving a comprehensive understanding of biological systems [9]. Several computational approaches have been developed for this purpose, which can be broadly categorized into three groups:

- Combined omics integration: This approach analyzes each omics dataset independently and integrates findings at the interpretation level, often using pathway enrichment analysis [9].

- Correlation-based integration: These methods apply statistical correlations between different omics datasets to identify co-regulated features, using network-based approaches to visualize relationships [9].

- Machine learning approaches: These utilize one or more types of omics data, potentially incorporating additional information, to comprehensively understand responses at classification and regression levels [9].

Specific correlation-based methods include gene co-expression analysis integrated with metabolomics data, which identifies gene modules that are co-expressed and links them to metabolites, and gene-metabolite networks, which visualize interactions between genes and metabolites in a biological system [9]. Tools such as Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) and visualization software like Cytoscape are commonly employed for these analyses [9].

Performance Comparison Across Omics Layers

A systematic comparison of genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data from the UK Biobank involving 500,000 individuals with complex diseases revealed significant differences in predictive performance across omics layers [10]. Using a machine learning pipeline to build predictive models for nine complex diseases, researchers found that proteomic biomarkers consistently outperformed those from other omics for both disease incidence and prevalence prediction [10].

Table 2: Predictive Performance of Different Omics Layers for Complex Diseases

| Omics Layer | Number of Features | Median AUC Incidence | Median AUC Prevalence | Optimal Feature Number for AUC≥0.8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteomics | 5 proteins | 0.79 (0.65-0.86) | 0.84 (0.70-0.91) | ≤5 for most diseases |

| Metabolomics | 5 metabolites | 0.70 (0.62-0.80) | 0.86 (0.65-0.90) | Variable by disease |

| Genomics | Scaled PRS | 0.57 (0.53-0.67) | 0.60 (0.49-0.70) | Limited clinical significance |

This research demonstrated that as few as five proteins could achieve area under the curve (AUC) values of 0.8 or more for both predicting incident and diagnosing prevalent disease, suggesting substantial potential for dimensionality reduction in clinical biomarker applications [10]. For example, in atherosclerotic vascular disease (ASVD), only three proteins—matrix metalloproteinase 12 (MMP12), TNF Receptor Superfamily Member 10b (TNFRSF10B), and Hepatitis A Virus Cellular Receptor 1 (HAVCR1)—achieved an AUC of 0.88 for prevalence, consistent with established knowledge of inflammation and matrix degradation in atherogenesis [10].

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Integration

Study Design Considerations

Effective multi-omics studies require careful experimental planning to ensure meaningful integration and interpretation [11]. Key considerations include:

- Disease characteristics: The selection of omics technologies should align with the pathological features of the disease under investigation [7].

- Sample size and power: Adequate sample sizes are essential for robust statistical analysis, particularly given the high dimensionality of omics data [11].

- Temporal considerations: For dynamic processes, longitudinal sampling can capture changes across omics layers over time [11].

- Data compatibility: Ensuring that datasets from different omics platforms are compatible and appropriately normalized is crucial for valid integration [8].

Research objectives in translational medicine applications typically fall into five categories: (i) detecting disease-associated molecular patterns, (ii) subtype identification, (iii) diagnosis/prognosis, (iv) drug response prediction, and (v) understanding regulatory processes [11]. The choice of omics combinations and integration methods should align with these specific objectives.

Protocol for Multi-Omics Data Integration

The following workflow outlines a standardized approach for multi-omics data integration, adaptable to various disease contexts and research questions:

Sample Preparation and Data Generation

- Collect appropriate biological samples (tissue, blood, cells) under standardized conditions

- Extract DNA, RNA, proteins, and metabolites using validated protocols

- Perform genomic (WGS/WES), transcriptomic (RNA-seq), proteomic (mass spectrometry), and metabolomic (MS/NMR) profiling

- Apply quality control measures specific to each omics technology

Data Preprocessing and Normalization

- Process raw data using platform-specific methods (e.g., normalization for RNA-seq)

- Address missing data using appropriate imputation methods (e.g., MICE for metabolomics data, missForest for transcriptomics) [8]

- Apply batch correction to account for technical variability

- Transform data to ensure compatibility across platforms

Feature Selection and Dimensionality Reduction

- Identify significantly altered features in each omics dataset using appropriate statistical methods

- Apply feature reduction techniques (e.g., median absolute deviation) to focus on most variable elements [8]

- Retain biologically relevant features for integration

Multi-Omics Data Integration

- Select appropriate integration method based on research objective:

- Validate integration robustness through cross-validation

Biological Interpretation and Validation

- Conduct pathway enrichment analysis to identify dysregulated biological processes

- Construct molecular networks to visualize cross-omics interactions

- Validate key findings using independent methods (e.g., immunohistochemistry, functional assays)

Multi-Omics Data Integration Workflow

Case Study: Multi-Omics Analysis of Methylmalonic Aciduria

Study Design and Implementation

A comprehensive multi-omics framework was applied to methylmalonic aciduria (MMA), a rare metabolic disorder, to demonstrate the power of integrated analysis for elucidating disease mechanisms [4]. The study integrated genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiling with biochemical and clinical data from 210 patients with MMA and 20 controls [4]. The analytical approach included:

- Protein quantitative trait locus (pQTL) analysis to map genetic loci influencing protein abundance levels

- Correlation network analyses integrating proteomics and metabolomics data

- Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and transcription factor enrichment analysis based on disease severity from transcriptomic data

This multi-layered approach revealed that glutathione metabolism plays a critical role in MMA pathogenesis, a finding substantiated by evidence across multiple molecular layers [4]. Additionally, the analysis revealed compromised lysosomal function in patients with MMA, highlighting the importance of this cellular compartment in maintaining metabolic balance [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Multi-Omics Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Application Context | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | QIAamp DNA Mini Kit | Genomics/Transcriptomics | High-quality DNA/RNA isolation for sequencing |

| Sequencing Library Prep | TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Library Kit | Whole Genome Sequencing | Library construction for Illumina platforms |

| Proteomics Standards | Biognosys iRT Kit | Mass Spectrometry Proteomics | Retention time calibration and quality control |

| Cell Culture Media | Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) | Cell-based multi-omics studies | Maintenance of primary cell cultures |

| Chromatin Analysis | ATAC-sequencing reagents | Epigenomics studies | Assessment of chromatin accessibility |

| Metabolomic Standards | Stable isotope-labeled metabolites | Targeted metabolomics | Quantification and method validation |

Computational Tools for Multi-Omics Integration

Several computational tools have been developed to address the challenges of multi-omics data integration:

- Holomics: A user-friendly R Shiny application that provides a well-defined workflow for multi-omics data integration, particularly suitable for scientists with limited bioinformatics knowledge [8]. It implements algorithms from the mixOmics package and offers automated filtering processes based on median absolute deviation (MAD) [8].

- mixOmics: An R package that uses sparse multivariate models for multi-block data design and integrative analysis [8]. It includes methods for single-omics analyses (PCA, PLS-DA) and multi-omics analyses (DIABLO) [8].

- Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA): Used for co-expression network analysis to identify modules of highly correlated genes and their association with other omics layers [4].

- Cytoscape: Network visualization software that enables the construction and analysis of gene-metabolite networks and other multi-omics interactions [9].

Numerous public repositories provide access to multi-omics datasets for research and method development:

- The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): Contains genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics data for various cancer types [11].

- Answer ALS: Provides whole-genome sequencing, RNA transcriptomics, ATAC-sequencing, proteomics, and deep clinical data for ALS research [11].

- UK Biobank: A prospective study of 500,000 individuals with extensive phenotypic and multi-omics data, particularly valuable for complex disease research [10].

- jMorp: A database/repository containing genomics, methylomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics data [11].

Multi-Omics Tools and Applications Ecosystem

The integration of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics provides unprecedented opportunities for understanding complex disease mechanisms and identifying novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets. While each omics layer offers unique insights into biological systems, their integrated analysis reveals emergent properties that cannot be captured by single-omics approaches. The protocols and frameworks outlined in this article provide a roadmap for researchers to design and implement effective multi-omics studies, leveraging publicly available tools and resources. As multi-omics technologies continue to evolve and become more accessible, they hold tremendous promise for advancing precision medicine and improving patient outcomes across a wide spectrum of complex diseases.

The study of complex human disorders requires a holistic perspective that moves beyond single-layer molecular analysis. Multi-omics—the integrated analysis of data from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics—provides a powerful framework for piecing together the complete biological puzzle of health and disease [12]. This approach reveals interactions across biological layers, helping to identify disease features that remain invisible in single-omics studies [12]. For instance, a disease phenotype might only be fully explained by combining DNA variants, methylation patterns, gene expression, and protein activity [12].

The field is expanding rapidly, with the multi-omics market valued at USD 2.76 billion in 2024 and projected to reach USD 9.8 billion by 2033, demonstrating a compound annual growth rate of 15.32% [12]. This growth is fueled by rising investments, growing demand for personalized medicine, and continuous technological progress. The recent launch of the NIH Multiomics for Health and Disease Consortium, with over US$50 million in funding, further underscores the strategic importance of this field [12]. This Application Note provides a comprehensive workflow from sample collection to data integration, specifically framed within complex disease research for drug development applications.

Multi-Omics Experimental Design and Sample Preparation

Strategic Planning and Sample Collection

Successful multi-omics studies begin with meticulous experimental design aimed at minimizing variability that can compromise data integration. Variability begins long before data collection—sample acquisition, storage, extraction, and handling affect every subsequent omics layer, making poor pre-analytics the single greatest threat to reproducibility [13].

Key considerations for sample preparation include:

- Uniform Collection Procedures: Enforce uniform collection, aliquoting, and storage procedures across all samples, limiting freeze-thaw cycles and logging all sample metadata in a shared Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) [13].

- Sample Quality Assessment: Remove invalid data containing null values, NaN, INF, or samples where zero values exceed 10% of total data points [14].

- Cohort Harmonization: Address harmonization issues that arise when samples from multiple cohorts are analyzed in different laboratories worldwide, which complicates data integration [15].

Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Studies

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Multi-Omics Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function in Multi-Omics Workflow | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Common Reference Materials | Enables cross-layer comparability and cross-site standardization [13]. | Certified cell-line lysates, isotopically labeled peptide standards [13]. |

| Liquid Biopsy Kits | Non-invasive collection of biomarkers including ctDNA, RNA, proteins, and metabolites [15] [16]. | Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis, exosome profiling [16]. |

| Single-Cell Multi-Omics Kits | Simultaneous profiling of genome, transcriptome, and epigenome from the same cells [15]. | Assays for transposase-accessible chromatin with sequencing (ATAC-seq) paired with RNA-seq [17]. |

| Internal Control Spikes | Normalization and quality control for technical variability within and across omics layers [13]. | Ratio-based normalization controls, retention-time calibration standards for mass spectrometry [13]. |

Data Generation and Preprocessing for Multiple Omics Layers

Technology Platforms and Data Characteristics

Modern multi-omics studies leverage diverse technological platforms to capture complementary biological information. Advances now enable multi-omic measurements from the same cells, allowing investigators to correlate specific genomic, transcriptomic, and/or epigenomic changes within those individual cells [15]. Similarly, the integration of both extracellular and intracellular protein measurements, including cell signaling activity, provides another layer for understanding tissue biology [15].

Table 2: Multi-Omics Data Types and Analytical Platforms

| Omics Layer | Key Technologies | Data Characteristics | Preprocessing Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) [15], SNP arrays | Variant call format (VCF) files, genotype matrices | Variant annotation, quality filtering, linkage disequilibrium pruning |

| Epigenomics | DNA methylation arrays, ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq [17] | Methylation beta values, chromatin accessibility peaks | Peak calling, background correction, batch effect adjustment |

| Transcriptomics | RNA-seq [18], single-cell RNA-seq [18], spatial transcriptomics [15] | Gene expression counts, transcript per million (TPM) | Normalization, batch correction, removal of low-variance features [14] |

| Proteomics | Mass spectrometry, affinity-based arrays | Protein abundance values, spectral counts | Imputation of missing values, variance stabilization normalization |

| Metabolomics | Mass spectrometry, NMR spectroscopy | Metabolite abundance values, spectral peaks | Peak alignment, solvent background subtraction, retention time correction |

Data Quality Control and Preprocessing Pipeline

Robust preprocessing is essential for generating analyzable multi-omics data. The preprocessing phase must address several common challenges: complex preprocessing including normalization, missing values, batch effects, outliers, sparse or low-variance features, multicollinearity, and artifacts [12].

Critical preprocessing steps include:

- Missing Value Estimation: Omics data often contain missing values which could cause potential issues in downstream analysis. Users can exclude features with too many missing values or perform missing value estimation based on several widely used methods [19].

- Data Filtering: Given the high-dimensional nature of omics data, it is strongly recommended to perform unspecific data filtering to exclude features that are unlikely to be useful in downstream analysis. Features that are relatively consistent can be safely excluded based on their inter-quantile ranges (IQRs) or other variance measures [19].

- Quality Checking and Normalization: The goal is to make different omics data more 'integrable' by sharing similar distributions. Users can visually examine the distribution of individual omics data through density plots, PCA plots, and t-SNE plots. Based on the visual assessment, users can choose among a variety of data transformation, centering, and scaling options to improve integrability [19].

Computational Integration and Analytical Methods

Methodological Approaches for Multi-Omics Data Integration

The integration of disparate omics datasets requires sophisticated computational approaches that can handle data heterogeneity, high dimensionality, and complex biological relationships. Optimal integrated multi-omics approaches interweave omics profiles into a single dataset for higher-level analysis, starting with collecting multiple omics datasets on the same set of samples and then integrating data signals from each prior to processing [15].

Table 3: Multi-Omics Data Integration Methods and Applications

| Integration Method | Key Algorithms/Tools | Strengths | Complex Disease Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Similarity-Based Networks | Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) [14] [19], Graph Attention Networks (GAT) [14] | Captures sample relationships, handles heterogeneity | Disease subtyping [12], cancer classification [14] |

| Matrix Factorization | Multi-Omics Factor Analysis (MOFA), Joint Non-negative Matrix Factorization | Identifies latent factors, reduces dimensionality | Pattern discovery across omics layers, biomarker identification |

| Graph Neural Networks | Multi-Omics Graph Convolutional Network (MOGONET) [14], Multi-omics Data Integration Learning Model (MODILM) [14] | Incorporates biological network information, captures complex relationships | Complex disease classification [14], drug response prediction [20] |

| Knowledge-Driven Integration | Biological pathway mapping, knowledge graphs [12] | Leverages prior knowledge, enhances interpretability | Pathway analysis, mechanistic insights [12] |

| Deep Learning Models | multiDGD [17], Deep Neural Networks [14], Variational Autoencoders [17] | Handles non-linear relationships, powerful representation learning | Patient stratification [15], predictive model building [16] |

Implementation of Advanced Integration Models

MODILM for Complex Disease Classification: The MODILM (Multi-Omics Data Integration Learning Model) framework exemplifies a modern approach specifically designed for complex disease classification [14]. This method includes four key steps: (1) constructing a similarity network for each omics data using cosine similarity measure; (2) leveraging Graph Attention Networks to learn sample-specific and intra-association features; (3) using Multilayer Perceptron networks to map learned features to a new feature space; and (4) fusing these high-level features using a View Correlation Discovery Network to learn cross-omics features in the label space [14]. This approach has demonstrated superior performance in classifying complex diseases including cancer subtypes [14].

multiDGD for Joint Representation Learning: multiDGD is a scalable deep generative model that provides a probabilistic framework to learn shared representations of transcriptome and chromatin accessibility [17]. Unlike Variational Autoencoder-based models, multiDGD uses no encoder to infer latent representations but rather learns them directly as trainable parameters, and employs a Gaussian Mixture Model as a more complex and powerful distribution over latent space [17]. This model shows outstanding performance on data reconstruction without feature selection and learns well-clustered joint representations from multi-omics data sets from human and mouse [17].

Validation and Interpretation in Complex Disease Research

Analytical Validation and Biological Interpretation

Robust validation is essential for translating multi-omics findings into meaningful biological insights and clinical applications. The integration of multi-omics data also accelerates the drug development process by improving therapeutic strategies, predicting drug sensitivity, and repurposing existing drugs [12].

Key validation approaches include:

- Cross-Platform Verification: Important findings should be verified using complementary analytical platforms. For example, genes identified through microarray and RNA-seq analyses should be validated in patient samples using qRT-PCR [18].

- Functional Enrichment Analysis: Mapped genes and metabolites of interest should be analyzed in known metabolic pathways or networks to generate biological hypotheses [19].

- Independent Cohort Validation: Discoveries should be tested in independent patient cohorts to ensure generalizability and clinical relevance.

Reproducibility Framework and Quality Assurance

Reproducibility is a critical challenge in multi-omics research, with many results failing replication due to practices like HARKing (hypothesizing after results are known) that undermine reproducibility [12]. Building a reproducibility-driven framework requires addressing several key aspects:

Essential components of a reproducibility framework:

- Standardized Operating Procedures (SOPs): Create standardized operating procedures for every omics layer and adopt common reference materials for true cross-layer comparability [13].

- Batch Effect Monitoring: Use reference samples, dashboards, and ratio-based normalization to track technical drift and quantify variation over time [13].

- Version Control: Containerize software, track all parameters, and log every data lineage from instrument to result [13].

- Data Integration with Robust Pipelines: Implement systems that maintain strict version control of analysis pipelines, documenting any software or parameter changes to allow reproducibility to be verified years after initial publication [13].

The Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) provides an exemplary model for multi-omics reproducibility, implementing a comprehensive QA/QC architecture that combined standardized reference materials, harmonized workflows, and centralized data governance [13]. Through these measures, CPTAC achieved reproducible proteogenomic profiles across independent sites with cross-site correlation coefficients exceeding 0.9 for key protein quantifications [13].

This Application Note has outlined a comprehensive workflow for multi-omics studies from sample collection through data integration, emphasizing applications in complex disease research and drug development. The field continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping its future trajectory.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are anticipated to play an even bigger role in multi-omics analysis, enabling more sophisticated predictive models that can forecast disease progression and treatment responses based on biomarker profiles [16]. Similarly, liquid biopsies are poised to become a standard tool in clinical practice, facilitating real-time monitoring of disease progression and treatment responses [16]. The rise of network-based integration methods that abstract biological interactions into network models represents another significant trend, particularly valuable for capturing the complex interactions between drugs and their multiple targets [20].

As these technological advances continue, the multi-omics workflow described here will become increasingly essential for unraveling the complexity of human diseases and accelerating the development of personalized therapeutic approaches.

The Role of Multi-Omics in Unraveling Disease Heterogeneity and Mechanisms

Application Notes

Multi-omics data integration has emerged as a powerful framework for obtaining a comprehensive view of disease mechanisms, particularly for complex, multifactorial diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative disorders [1]. By simultaneously analyzing multiple molecular layers—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics—researchers can move beyond single-layer insights to understand the systemic properties of biological systems in health and disease [11]. This approach is transforming translational medicine by enabling precise patient stratification, revealing molecular heterogeneity, and identifying novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets [1] [11].

The design of a successful multi-omics study begins with formulating a clear biological question, which directly influences the choice of omics technologies, datasets, and analytical methods [21]. Subsequent critical steps include selecting appropriate omics layers, ensuring high data quality, and standardizing data across platforms to enable valid comparisons [21]. The integration of these diverse datasets can identify disease-associated molecular patterns, define disease subtypes, understand regulatory processes, predict drug response, and improve diagnosis and prognosis [11].

Table 1: Key Multi-Omics Technologies and Their Applications in Disease Research

| Omics Layer | Biological Insight | Common Technologies | Primary Applications in Disease Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Genetic variations, DNA sequence | WGS, WES | Identify hereditary factors, predispositions, and driver mutations [4] |

| Transcriptomics | Gene expression levels, alternative splicing | RNA-seq, scRNA-seq | Uncover differentially expressed genes and pathways; identify cell subpopulations [22] |

| Proteomics | Protein abundance, post-translational modifications | DIA-MS, LC-MS/MS | Link genotype to phenotype; identify therapeutic targets and signaling pathways [23] [4] |

| Metabolomics | Metabolic state, pathway fluxes | Mass spectrometry | Reflect biochemical activities and metabolic dysregulation [4] |

| Epigenomics | DNA methylation, histone modifications | ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq | Reveal regulatory mechanisms influencing gene expression [11] |

The analysis of multi-omics data presents significant challenges due to its high dimensionality, heterogeneity, and complexity [1] [12]. Computational methods such as network-based approaches offer a holistic view of relationships among biological components [1]. Machine learning and consensus clustering can identify molecular subgroups within seemingly uniform diseases [22] [24]. For example, in Alzheimer's disease, machine learning integration of transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and lipidomic profiles revealed four unique multimodal molecular profiles with distinct clinical outcomes, highlighting the molecular heterogeneity of the disease [24]. Similarly, in breast cancer, integrated single-cell and bulk RNA sequencing analyses identified a distinct glycolysis-activated epithelial cancer cell subtype associated with poor prognosis and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment [22].

To enhance reproducibility and reuse, researchers are increasingly adopting FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) principles for both data and computational workflows [25]. This includes using workflow managers like Nextflow, containerization with Docker or Apptainer/Singularity, version control, and rich metadata documentation [25]. These practices help ensure that multi-omics analyses are transparent, reproducible, and build upon a solid computational foundation.

Protocols

Protocol 1: An Integrated Workflow for Multi-Omics Data Analysis

This protocol outlines a general workflow for multi-omics data integration, synthesizing methods from several recent studies [25] [11] [22].

Step 1: Experimental Design and Data Collection

- Define Clear Biological Questions: Determine whether the study focuses on subtype identification, biomarker discovery, understanding regulatory mechanisms, or other objectives [11] [21].

- Select Appropriate Omics Layers: Choose complementary omics technologies based on the research question (refer to Table 1) [21].

- Implement Consistent Experimental Design: Ensure samples are matched across omics layers and that experimental conditions are standardized to minimize batch effects [21].

- Apply Quality Control: Perform technology-specific quality checks. For single-cell RNA-seq, check mitochondrial gene expression percentage; for proteomics, use retention time peptides to monitor performance [22] [4].

Step 2: Data Preprocessing and Harmonization

- Process Raw Data: Use appropriate tools for each omics type (e.g., Cell Ranger for scRNA-seq, MaxQuant for proteomics) [22].

- Normalize Data: Apply normalization methods suitable for each data type (e.g., TPM for RNA-seq, variance-stabilizing normalization for proteomics) [21].

- Address Batch Effects: Use ComBat or other batch correction methods when integrating datasets from different sources [21].

- Standardize Identifiers: Map all biomolecules to standard identifiers (e.g., HGNC for genes, UniProt for proteins) to enable cross-omics integration [23].

Step 3: Data Integration and Analysis

- Choose Integration Method: Select based on research objective (see Table 2).

- Perform Cross-Omics Correlation: Identify relationships between different molecular layers (e.g., transcript-protein correlations) [23].

- Implement Multimodal Clustering: Use tools like ConsensusClusterPlus to identify disease subtypes based on integrated patterns [22].

- Construct Co-expression Networks: Apply WGCNA to identify modules of correlated genes across omics layers [22] [4].

Table 2: Multi-Omics Data Integration Methods by Research Objective

| Research Objective | Computational Methods | Example Tools | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subtype Identification | Multimodal clustering, Matrix factorization | iClusterPlus, ConsensusClusterPlus | Patient subgroups, molecular subtypes [22] [12] |

| Detect Disease-Associated Patterns | Correlation networks, Regression models | WGCNA, Linear Regression | Molecular signatures, biomarker panels [11] [23] |

| Understand Regulatory Processes | QTL analysis, Pathway enrichment | pQTL/eQTL analysis, GSEA | Causal networks, regulatory mechanisms [11] [4] |

| Biomarker Discovery | Machine learning, Feature selection | LASSO, Random Forest | Predictive signatures, prognostic models [22] [4] |

| Drug Response Prediction | Network-based integration, Sensitivity prediction | OncoPredict, Correlation networks | Therapy response biomarkers, drug targets [11] [22] |

Step 4: Validation and Interpretation

- Conduct Functional Enrichment: Use tools like GSEA to identify pathways enriched in discovered subtypes or signatures [4].

- Validate Findings: Employ independent cohorts or experimental validation (e.g., RT-qPCR, functional assays) [22].

- Interpret Results: Contextualize findings using known pathways and networks from databases like KEGG and Reactome [23].

Protocol 2: A Computational Framework for Multi-Omics Mechanistic Insight

This protocol details a specific analytical framework for elucidating disease mechanisms through multi-omics integration, based on established workflows [4].

Step 1: Protein Quantitative Trait Loci (pQTL) Analysis

- Prepare Genotype and Protein Data: Use whole genome sequencing (WGS) data and quantitative proteomics from the same samples [4].

- Perform pQTL Mapping: Identify genetic variants associated with protein abundance levels using linear regression models, accounting for relevant covariates [4].

- Distinguish cis- and trans-pQTLs: Classify pQTLs based on proximity to the protein-coding gene (cis: within 1 MB; trans: elsewhere in genome) [4].

- Conduct Enrichment Analysis: Test pQTLs for enrichment in functional categories and pathways relevant to the disease [4].

Step 2: Correlation Network Analysis

- Construct Correlation Networks: Calculate pairwise correlations between proteins and metabolites across samples [4].

- Identify Network Modules: Use algorithms to detect groups of highly interconnected proteins and metabolites [4].

- Test Module-Trait Associations: Correlate module eigengenes (first principal components) with clinical traits and disease severity [4].

- Characterize Key Modules: Perform functional enrichment on genes/proteins in disease-associated modules [4].

Step 3: Transcriptomic Validation

- Conduct Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA): Test if genes from pQTL and network analyses show concordant expression changes in transcriptomic data [4].

- Perform Transcription Factor (TF) Enrichment: Identify TFs whose targets are enriched among differentially expressed genes, stratified by disease severity [4].

- Integrate Findings: Accumulate evidence across omics layers to prioritize disrupted pathways with multi-modal support [4].

Protocol 3: Single-Cell Multi-Omics Integration for Tumor Heterogeneity

This protocol describes how to integrate single-cell and bulk omics data to investigate metabolic heterogeneity in cancer, following established methods [22].

Step 1: Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Analysis

- Quality Control and Filtering: Retain cells meeting quality thresholds (e.g., gene counts, mitochondrial percentage) [22].

- Data Normalization and Integration: Normalize counts and correct for technical variations using methods like SCTransform [22].

- Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: Perform UMAP/t-SNE for visualization and graph-based clustering to identify cell subpopulations [22].

- Cell Type Annotation: Identify marker genes for each cluster and annotate cell types using known markers [22].

- Subcluster Analysis: Further cluster epithelial/cancer cells to identify metabolic subpopulations [22].

Step 2: Metabolic Analysis of Cancer Subpopulations

- Calculate Metabolic Activity: Use tools like scMetabolism R package to quantify metabolic pathway activities [22].

- Identify Metabolically Distinct Subtypes: Detect epithelial cancer cell subtypes with activated glycolysis or other metabolic pathways [22].

- Differential Expression Testing: Compare metabolic subpopulations using the FindMarkers() function to identify subtype-specific markers [22].

Step 3: Bulk Tissue Validation and Stratification

- Consensus Clustering: Apply ConsensusClusterPlus to bulk transcriptomic data to stratify patients into molecular clusters [22].

- Survival Analysis: Compare clinical outcomes between clusters using Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests [22].

- Tumor Microenvironment Characterization: Decode immune cell infiltration abundances using tools wrapped in the IOBR R package [22].

Step 4: Prognostic Model Construction

- Identify Hub Genes: Use WGCNA to identify modules associated with cancer subclusters and extract hub genes [22].

- Build Predictive Model: Apply machine learning algorithms to construct a metabolic risk signature [22].

- Validate Model: Test the prognostic model across multiple independent cohorts [22].

- Therapeutic Implications: Predict drug sensitivity using OncoPredict and validate potential targets through functional experiments [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Multi-Omics Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Fibroblast Cultures | Biological Sample | Model patient-specific physiology | In vitro disease modeling for MMA [4] |

| Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) | Cell Culture Reagent | Support fibroblast growth | Culture medium for patient-derived cells [4] |

| TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Library Kit | Library Prep Kit | Prepare WGS libraries | Whole genome sequencing for pQTL analysis [4] |

| QIAmp DNA Mini Kit | Nucleic Acid Extraction | Isolate genomic DNA | DNA extraction for WGS [4] |

| Nextflow | Workflow Manager | Orchestrate computational pipelines | Reproducible multi-omics analysis [25] |

| Docker/Apptainer | Containerization | Capture runtime environment | Ensure computational reproducibility [25] |

| ConsensusClusterPlus | R Package | Multimodal clustering | Identify disease subtypes [22] |

| WGCNA | R Package | Co-expression network analysis | Identify correlated gene modules [22] [4] |

| scMetabolism | R Package | Quantify metabolic activity | Identify metabolic subtypes in cancer [22] |

| OncoPredict | R Package | Drug sensitivity prediction | Predict chemotherapy response [22] |

| TRIzol Reagent | RNA Isolation | Extract total RNA | RNA preparation for transcriptomics [22] |

| SYBR GreenER Supermix | qPCR Reagent | Quantitative PCR detection | Validate gene expression findings [22] |

The landscape of biomedical research has been fundamentally reshaped by the advent of single-cell and spatial multi-omics technologies. These approaches have transitioned from specialized techniques to indispensable tools, enabling the unprecedented resolution of cellular heterogeneity and spatial organization within complex tissues [26] [27]. Since the introduction of single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) in 2009, the field has rapidly evolved beyond transcriptomics to encompass parallel profiling of genomic, epigenomic, proteomic, and metabolomic readouts from individual cells [26]. This technological revolution is propelling novel discoveries across all niches of biomedical research, particularly in elucidating the mechanisms of complex diseases, where it provides a comprehensive view of the multilayered molecular interactions that drive pathogenesis [1] [28]. The convergence of single-cell resolution with spatial context represents the next frontier, offering a multi-dimensional window into cellular niches and tissue microenvironments that is transforming our understanding of biology in health and disease [29] [30].

Quantitative Trends in Technology Adoption and Data Generation

The adoption of single-cell and spatial multi-omics is demonstrated by a massive increase in the scale and scope of research efforts. Current studies routinely profile hundreds of thousands to millions of cells, a stark contrast to the capabilities available just a few years ago [26] [28].

Table 1: Scale of Single-Cell and Spatial Multi-Omics Studies in Human Tissues

| Tissue/System | Number of Cells/Nuclei | Number of Donors | Key Findings | Year | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Heart (Ventricular) | 881,081 | 79 | Illuminated cell types/states in DCM and ACM | 2022 | [26] |

| Human Heart (Health/Disease) | 592,689 | 42 | Comprehensive characterization in health, DCM, and HCM | 2022 | [26] |

| Human Myocardial Infarction | 191,795 | 23 | Integrative molecular map of human myocardial infarction | 2022 | [26] |

| Multiple Tissues (Fetal) | ~4.98 million | 121 | Organ-specific and cell-type specific gene regulations | 2020 | [26] |

| Cross-Species (Foundation Models) | 33-110 million | N/A | Scalable pretraining for zero-shot cell annotation & perturbation prediction | 2025 | [28] |

The data generation is supported by platforms like the Galaxy single-cell and spatial omics community (SPOC), which at the time of writing had over 175 tools, 120 training resources, and had processed more than 300,000 analysis jobs [27]. Computational frameworks are now being trained on datasets of unprecedented scale, with models like scGPT pretrained on over 33 million cells and Nicheformer extending this to 110 million cells, enabling robust zero-shot generalization capabilities [28].

Application Note 1: Resolving Cardiovascular Disease Heterogeneity

Experimental Aims

Cardiovascular diseases remain a leading cause of mortality worldwide, characterized by complex cellular remodeling processes. This application note details the use of single-cell multi-omics to deconvolve the cellular heterogeneity of human hearts in health and disease, specifically focusing on dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM) [26].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cardiac Single-Cell Multi-Omics

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Single-cell partitioning and barcoding | Enables profiling of tens of thousands of cells in a single experiment [26] |

| Single-cell ATAC-seq Kit | Assessing chromatin accessibility | Uncover chromatin biology of heart diseases [26] |

| C1 Fluidigm IFC | Integrated Fluidic Circuit for cell capture | Automates cell staining, lysis, and preparation; allows microscopic examination [26] |

| BD Rhapsody | Targeted scRNA-seq with full-length TCR potential | Enables immune profiling alongside transcriptomics [31] |

| Spatial Barcoded Surfaces | Spatial nuclei tagging for positional mapping | Donates DNA barcodes to nuclei for direct spatial measurement [30] |

Methodological Protocol

Sample Preparation and Single-Nuclei RNA-seq:

- Tissue Acquisition: Obtain human ventricular samples from non-failing and failing hearts (e.g., DCM, ACM). Snap-freeze tissue in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C [26].

- Nuclei Isolation: Mechanically homogenize frozen tissue in lysis buffer. Filter the homogenate through a cell strainer and purify nuclei via density gradient centrifugation [26].

- Single-Nuclei Partitioning: Load the nuclei suspension onto the 10x Genomics Chromium controller to partition single nuclei into droplets containing barcoded beads [26].

- Library Preparation: Perform reverse transcription, cDNA amplification, and library construction following the manufacturer's protocol. Include sample indexes for multiplexing [26].

- Sequencing: Sequence libraries on an Illumina platform to a minimum depth of 50,000 reads per nucleus [26].

Multi-Omic Integration and Data Analysis:

- Data Processing: Demultiplex sequencing data and align reads to the human reference genome (e.g., GRCh38). Generate gene-barcode matrices [26].

- Quality Control: Filter out low-quality nuclei based on gene counts, UMIs, and mitochondrial percentage.

- Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: Perform principal component analysis (PCA) followed by graph-based clustering. Visualize cells in two dimensions using UMAP.

- Cell Type Annotation: Identify major cardiac cell types (cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, pericytes, immune cells) using known marker genes [26].

- Differential Expression: Identify genes significantly dysregulated between disease and control states within each cell type.

- Integrated Analysis with scATAC-seq: Process scATAC-seq data from coronary arteries to identify cell-type-specific regulatory elements and transcription factors. Use integration tools (e.g., Seurat, Giotto Suite) to map chromatin accessibility to transcriptomic clusters [26] [29].

Key Workflow Diagram

Diagram: Integrated Workflow for Cardiac Single-Cell Multi-Omics Analysis

Application Note 2: Spatial Mapping of Tumor Microenvironment

Experimental Aims

Gastrointestinal tumors pose significant clinical challenges due to their high heterogeneity and complex tumor microenvironment (TME). This protocol details the application of spatial multi-omics to dissect the cellular architecture, metabolic-immune interactions, and spatial niches within colorectal and gastric cancer tissues [30] [32].

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Spatial Multi-Omics Reagents and Platforms

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Spatially Barcoded Oligo Arrays | Genome-wide transcriptome capture | Captures RNA transcripts with positional information [30] |

| Multiplexed FISH Probes | Targeted transcript imaging | Visualizes pre-defined gene sets with subcellular resolution [30] |

| Antibody Panels (CODEX/IMC) | Spatial proteomics | Measures 40+ protein markers in situ [32] |

| Spatial Nuclei Tagging Surface | Direct single-cell spatial mapping | Donates DNA barcodes to nuclei for direct measurement [30] |

| DESI-MSI Platform | Spatial metabolomics imaging | Maps metabolic gradients within tumor microenvironment [32] |

Methodological Protocol

Spatial Transcriptomics and Proteomics:

- Tissue Sectioning: Cryosection fresh-frozen or FFPE-preserved gastrointestinal tumor tissues at 5-10μm thickness. Mount sections on appropriate slides for the chosen spatial platform [30].

- Spatial Barcoding: For array-based methods, place tissue sections on spatially barcoded oligo arrays. Perform permeabilization to release RNAs that are then captured by spatial barcodes [30].

- Library Construction: Synthesize cDNA from captured RNA, amplify, and construct sequencing libraries with spatial barcodes preserved.

- Multiplexed Protein Detection: For spatial proteomics, stain tissue with metal-tagged or fluorescently labeled antibody panels. For cyclic imaging, perform iterative staining, imaging, and dye inactivation cycles [32].

- Image Registration: Stain adjacent sections with H&E for histological annotation and align with multi-omics data.

Single-Cell Spatial Multi-Omics Integration:

- Data Generation: Perform scRNA-seq on dissociated tumor cells to create a reference atlas. Integrate with spatial data using computational tools like Giotto Suite [29] [32].

- Cell Type Deconvolution: Use reference-based deconvolution algorithms to infer the proportion of cell types within each spatial spot [30].

- Spatial Pattern Identification: Identify spatially variable genes and proteins using spatial autocorrelation statistics (e.g., Moran's I).

- Niche Discovery: Apply clustering algorithms to spatial coordinates and molecular profiles to identify recurrent cellular neighborhoods and interface regions [29].

- Metabolic-Immune Mapping: Integrate DESI-MSI metabolomic data with transcriptomic and proteomic maps to visualize metabolic gradients (e.g., lactate) and their correlation with immune cell distributions [32].

Key Workflow Diagram

Diagram: Spatial Multi-Omics Analysis of Tumor Microenvironment

Computational Frameworks for Multi-Omics Data Integration

The complexity and volume of data generated by single-cell and spatial technologies necessitate sophisticated computational frameworks for integration and interpretation. These ecosystems have become critical to sustaining progress in the field [29] [28].

Giotto Suite: This modular suite of R packages provides a technology-agnostic ecosystem for spatial multi-omics analysis. At its core, Giotto Suite implements an innovative data framework with specialized classes (giottoPoints, giottoPolygon, giottoLargeImage) that efficiently represent point (e.g., transcripts), polygon (e.g., cell boundaries), and image data. This framework facilitates the organization and integration of multiple feature types (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics) across multiple spatial units (e.g., nucleus, cell, tissue domain), enabling multiscale analysis from subcellular to tissue level [29].

Foundation Models: Models such as scGPT, pretrained on massive datasets of over 33 million cells, demonstrate exceptional cross-task generalization capabilities. These transformer-based architectures utilize self-supervised pretraining objectives including masked gene modeling and multimodal alignment to capture hierarchical biological patterns. They enable zero-shot cell type annotation, in silico perturbation modeling, and gene regulatory network inference across diverse biological contexts [28].

Multimodal Integration Approaches: Advanced computational strategies are being developed to harmonize heterogeneous data types. PathOmCLIP aligns histology images with spatial transcriptomics via contrastive learning, while GIST combines histology with multi-omic profiles for 3D tissue modeling. Tensor-based fusion methods and mosaic integration techniques (e.g., StabMap) enable robust integration even when datasets don't measure identical features [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

Table 4: Comprehensive Toolkit for Single-Cell and Spatial Multi-Omics Research

| Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Platforms | 10x Genomics Chromium, BD Rhapsody, ICELL8 | Single-cell partitioning, barcoding, and library preparation [26] [31] |

| Spatial Technologies | 10x Visium, MERFISH, CODEX, DESI-MSI, Spatial Nuclei Tagging | Molecular profiling with tissue context preservation [29] [30] [32] |

| Computational Frameworks | Giotto Suite, Seurat, Scanpy, scGPT, CellRank | Data analysis, integration, visualization, and interpretation [29] [28] [31] |

| Analysis Platforms | Galaxy SPOC, DISCO, CZ CELLxGENE Discover | Reproducible workflows, federated analysis, data sharing [27] [28] |

| Specialized Toolkits | TCRscape, Immunarch, Loupe V(D)J Browser | Domain-specific analysis (e.g., immune repertoire) [31] |

Single-cell and spatial multi-omics technologies have fundamentally transformed our approach to investigating complex biological systems and disease mechanisms. The integration of multimodal data at cellular resolution provides an unprecedented panoramic view of the molecular networks driving cardiovascular pathogenesis, tumor heterogeneity, and other complex disease processes. As computational frameworks continue to evolve alongside wet lab methodologies, the field is poised to overcome current challenges related to data heterogeneity, analytical complexity, and clinical translation. The ongoing development of more accessible platforms, standardized analytical workflows, and AI-powered interpretation tools will further democratize these powerful technologies, accelerating their impact on biomarker discovery, drug development, and ultimately, precision medicine approaches for complex human diseases.

Computational Frameworks and AI Tools: From Theory to Translational Applications

The integration of multi-omics data has become a cornerstone of modern biomedical research, particularly in the study of complex diseases. Multi-omics data fusion refers to the computational integration of diverse biological data modalities—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics, and metabolomics—to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of biological systems and disease mechanisms. The core challenge lies in effectively combining these heterogeneous data types, which differ in scale, resolution, and biological interpretation. The three primary computational frameworks for addressing this challenge are early fusion (data-level integration), intermediate fusion (feature-level integration), and late fusion (decision-level integration). Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations for specific research contexts and analytical objectives in complex disease research [11].

The fundamental motivation for multi-omics integration stems from the recognition that complex diseases like cancer, neurological disorders, and metabolic conditions arise from dysregulated interactions across multiple biological layers rather than alterations in a single molecular component. As noted in a recent perspective on translational medicine, "Biology can be viewed as data science, and Medicine is moving towards a precision and personalised mode" [11]. Multi-omics profiling facilitates this transition by enabling researchers to capture the systemic properties of investigated conditions through specialized analytics per data layer and multisource data integration [11].

Classification of Multi-Omics Fusion Approaches

Early Fusion (Data-Level Integration)

Early fusion, also known as data-level integration or concatenation-based fusion, involves combining raw datasets from multiple omics layers into a single unified representation before analysis. In this approach, features from each modality are concatenated into one comprehensive matrix that serves as input for machine learning models [33] [34]. The combined dataset, with samples as rows and all omics features as columns, is then processed using statistical or machine learning methods.

Experimental Protocol: Early Fusion Implementation

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize each omics dataset separately using platform-specific methods (e.g., RSEM for RNA-seq, beta values for methylation data).

- Feature Selection: Apply dimensionality reduction to each omics layer to manage computational complexity (e.g., select top 5,000 most variable genes in transcriptomics data).

- Data Concatenation: Merge selected features from all omics layers into a single matrix using sample identifiers as anchors.

- Model Training: Input the combined matrix into classifiers such as Random Forest or Support Vector Machines.

- Validation: Perform cross-validation and external validation to assess model performance and prevent overfitting.

A key advantage of early fusion is its ability to capture inter-omics relationships directly from the input data, potentially revealing novel cross-modal interactions [33]. However, this approach faces significant challenges with high-dimensionality and data heterogeneity, as noted by researchers: "A simple concatenation of features across the omics is likely to generate large matrices, outliers, and highly correlated variables" [34]. The resulting "curse of dimensionality" is particularly problematic when working with limited patient samples, which is common in biomedical studies [35].

Intermediate Fusion (Feature-Level Integration)

Intermediate fusion, also known as feature-level integration, processes each omics layer separately initially, then integrates them into a joint representation before the final analysis. This approach preserves the unique characteristics of each data type while enabling the model to learn cross-modal relationships [33]. Intermediate fusion typically employs sophisticated algorithms that can model complex, non-linear relationships between omics layers.

Experimental Protocol: Intermediate Fusion with Similarity Network Fusion (SNF)

- Similarity Matrix Construction: For each omics layer, construct a patient similarity network using appropriate distance metrics (e.g., Euclidean distance for continuous data).

- Network Fusion: Iteratively fuse the similarity networks using methods like Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) to create a unified patient network that captures shared information across omics types.

- Feature Extraction: Apply the Integrative Network Fusion (INF) framework, which introduces a novel feature ranking scheme (rSNF) that sorts multi-omics features according to their contribution to the SNF-fused network structure [36].

- Model Training: Train machine learning classifiers (e.g., Random Forest) on the integrated features for prediction tasks.

- Biomarker Identification: Extract top-ranked biomarkers from the fused network for biological validation.

Intermediate integration methods "encourage predictions from different data views to align" through agreement parameters that facilitate cross-omics learning [37]. Deep learning architectures particularly excel at intermediate fusion, with autoencoders and graph neural networks effectively creating shared latent representations that capture the essential biological patterns across omics modalities [38] [33]. For example, graph neural networks model multi-omics data as heterogeneous networks with multiple node types (e.g., genes, proteins, metabolites) and diverse edges representing their biological relationships [34].

Late Fusion (Decision-Level Integration)

Late fusion, also known as decision-level integration, involves training separate models on each omics layer and then combining their predictions using a meta-learner. This approach maintains the integrity of each data modality throughout the modeling process, only integrating information at the final decision stage [39] [33].

Experimental Protocol: Late Fusion for Cancer Subtype Classification

- Individual Model Training: Train specialized machine learning models (e.g., Random Forest, SVM, neural networks) separately on each omics dataset (e.g., RNA-seq, miRNA-seq, methylation data).

- Prediction Generation: Each model produces prediction probabilities for the outcome of interest (e.g., cancer subtypes, survival risk).