Multi-Objective Optimization in Metabolic Engineering: Strategies for Robust Strain Design and Pharmaceutical Production

This article explores the critical role of multi-objective optimization in advancing metabolic engineering for pharmaceutical and chemical production.

Multi-Objective Optimization in Metabolic Engineering: Strategies for Robust Strain Design and Pharmaceutical Production

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of multi-objective optimization in advancing metabolic engineering for pharmaceutical and chemical production. It addresses the core challenge of balancing multiple, often competing, cellular objectives such as maximizing product yield, maintaining robust growth, and minimizing byproduct formation. The content is structured to guide researchers and drug development professionals from foundational principles to advanced computational methodologies, including consensus algorithms and genetic algorithms for strain design. It provides practical insights into troubleshooting network imbalances and optimizing pathways across transcriptomic, translatome, proteome, and reactome levels. Finally, it covers validation frameworks and comparative genomic tools like CONGA to assess strain performance and functional metabolic capabilities, offering a comprehensive resource for developing efficient microbial cell factories.

The Need for Multi-Objective Optimization in Metabolic Engineering

Defining Multi-Objective Optimization in a Metabolic Context

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is multi-objective optimization in the context of metabolic engineering? Multi-objective optimization (MOO) is a computational methodology used to solve problems where several biological objective functions must be optimized simultaneously within a microbial host. In metabolic engineering, this typically involves identifying genetic modifications that enable an optimal trade-off between competing cellular goals, such as maximizing the production of a target biochemical while maintaining sufficient cell growth or minimizing by-product formation. Unlike single-objective approaches, MOO does not yield a single optimal solution but rather a set of Pareto optimal solutions, where improving one objective necessitates compromising another [1] [2].

Q2: Why is a multi-objective approach necessary? Couldn't we just maximize production? Microbial cells are complex systems where metabolism is often geared toward growth and survival, not toward overproducing a single compound for industrial purposes. A singular focus on maximizing product titer can lead to non-viable strains with severely impaired growth [1]. Multi-objective optimization is necessary to account for these inherent trade-offs. It helps design balanced microbial chassis that achieve high productivity without catastrophic fitness costs, which is crucial for sustaining industrial bioprocesses [3] [2].

Q3: What are the typical objective functions used in these optimizations? The choice of objectives depends on the engineering goal. Common pairs of objective functions include:

- Maximizing product yield vs. Maximizing biomass growth [1] [2].

- Maximizing a desired product vs. Minimizing an undesirable by-product [2].

- Maximizing productivity vs. Minimering substrate consumption. Some advanced frameworks also incorporate dynamic objectives, such as optimizing enzyme activation profiles over time to improve metabolic efficiency during fermentations [4].

Q4: What computational tools are available for multi-objective metabolic optimization? Several algorithms and software tools have been developed, including:

- MOMO (Multi-Objective Metabolic Mixed Integer Optimization): An open-source framework that identifies reaction deletions to optimize multiple objectives simultaneously. It has been experimentally validated for ethanol production in yeast [2] [5].

- MOME (Multi-Objective Metabolic Engineering): An algorithm that models both gene knockouts and enzyme up/down-regulation for overproduction [1].

- Methods based on kinetic models, which use dynamic optimization to predict optimal time-dependent enzyme expression levels [6] [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Cell Growth After Implementing Predicted Gene Knockouts

Possible Cause and Solution

- Cause: The in silico prediction may have insufficiently accounted for gene essentiality or the knockout may have disrupted a critical metabolic flux.

- Solution:

- Verify Gene Essentiality: Before experimental implementation, cross-reference the knockout list with databases of essential genes for your model organism.

- Implement a Tuning Mechanism: Instead of a complete knockout, consider using CRISPRi or promoter tuning to down-regulate, rather than eliminate, the reaction flux [7] [8].

- Re-run Optimization with Constraints: Add constraints to the optimization model to ensure a minimum allowable biomass production rate is maintained [1].

Problem 2: In Silico Predictions Do Not Match Experimental Results

Possible Cause and Solution

- Cause: The genome-scale model may lack organism-specific regulatory information, or the simulation medium may not reflect the actual experimental conditions.

- Solution:

- Refine the Model: Incorporate transcriptomic or proteomic data to create context-specific models that better reflect the internal regulatory state of the cell.

- Validate Simulated Conditions: Ensure the nutrient constraints (e.g., carbon source, oxygen availability) in the model accurately match your fermentation setup [1] [4].

- Consider Dynamic Effects: Switch from steady-state to dynamic optimization frameworks, which can predict time-varying enzyme profiles and may better capture the fermentation dynamics [6] [4].

Problem 3: Unacceptable Levels of By-Product Formation

Possible Cause and Solution

- Cause: The metabolic network has been redirected in a way that creates a new, or enhances an existing, overflow metabolism.

- Solution:

- Re-formulate the MOO Problem: Include the minimization of the specific by-product as an explicit third objective in the optimization [2].

- Target By-Production Pathways: Identify and implement additional knockouts in the genes responsible for the by-product synthesis, as suggested by tools like MOMO [2].

- Explore Alternative Knockout Strategies: The Pareto front from a MOO analysis contains multiple strain designs. Select an alternative solution that offers a better trade-off between main product and by-product formation [1] [3].

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The following table summarizes the core methodologies cited in this document.

Table 1: Summary of Key Multi-Objective Optimization Methodologies in Metabolic Engineering.

| Method Name | Type of Model | Primary Decision Variables | Example Application | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOME [1] | Genome-scale (FBA) | Gene knockouts, enzyme up/down-regulation | Ethanol overproduction in E. coli | Identified knockout strategies increasing ethanol production by up to 832% |

| MOMO [2] [5] | Genome-scale (MILP) | Reaction deletions | Ethanol production in S. cerevisiae | Predicted and experimentally validated deletion strains with increased ethanol levels |

| Kinetic Model Optimization [6] | Dynamic kinetic model | Enzyme concentration levels (up/down-regulation) | CHO cell antibody production | Increased productivity, product titer, and biomass while keeping by-products low |

| Homo-Organic Acid Design [3] | Genome-scale (FBA) | Gene knockout targets | Production of acetic, lactic, and succinic acids in E. coli | Designed strains for homo-production (minimal by-products) of organic acids |

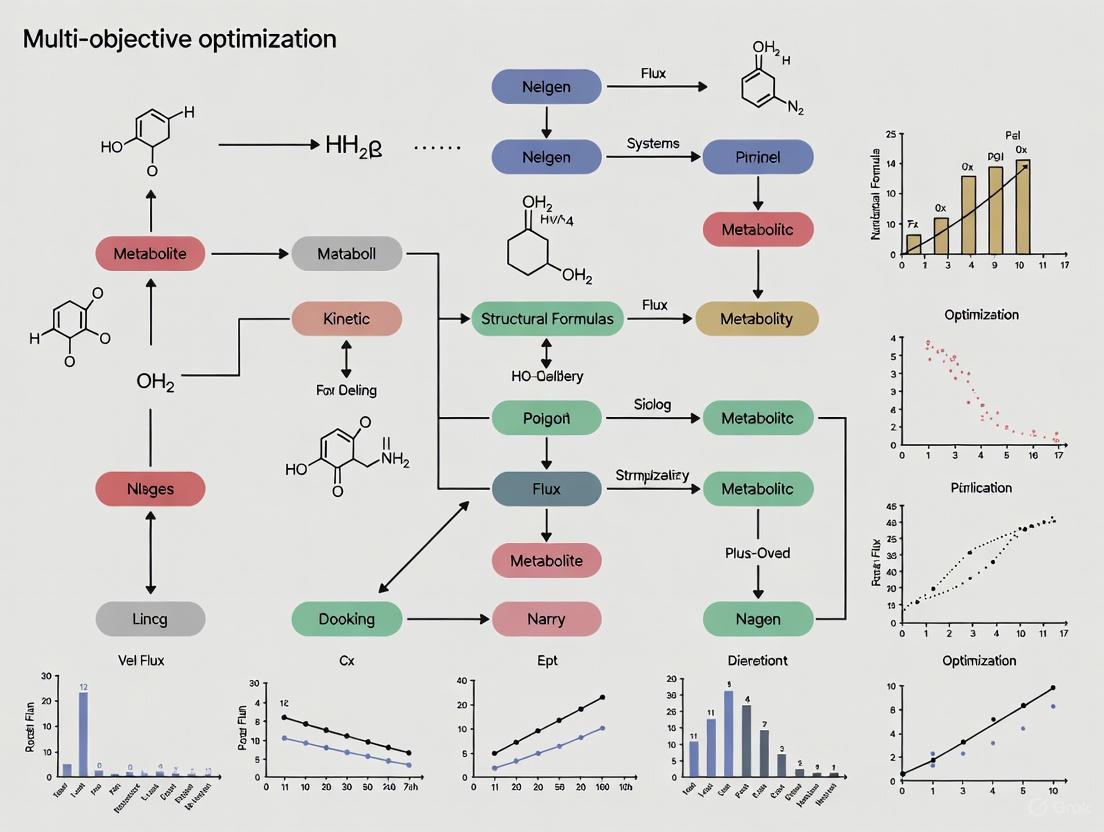

Visualizing the Multi-Objective Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for applying multi-objective optimization to a metabolic engineering problem, from model setup to experimental implementation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential research reagents, software, and materials for conducting multi-objective metabolic engineering.

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model | In silico representation of an organism's metabolism; the core constraint model for FBA and MOO. | Models for E. coli, S. cerevisiae; available from databases like BiGG and ModelSEED [1] [2]. |

| MOO Software | Open-source computational platforms to perform multi-objective optimizations. | MOMO (uses PolySCIP solver), MOME algorithm [1] [2] [5]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | For precise gene knockouts or knock-ins as predicted by the optimization. | Enables efficient genome editing in model hosts like E. coli and S. cerevisiae [8]. |

| CRISPRi (Interference) | For fine-tuned down-regulation of gene expression without full knockout. | Useful for implementing "up/down-regulation" suggestions and tuning flux [7]. |

| Fermentation Bioreactor | For experimental validation of engineered strains under controlled conditions. | Key for measuring objective functions like product titer, growth rate, and yield [1] [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why can't I simply maximize both product yield and biomass growth simultaneously? The metabolic network has a limited capacity. The substrate (e.g., glucose) is a shared resource that the cell can direct either towards biomass generation (growth) or towards product synthesis (yield). This creates a fundamental trade-off [9]. Optimizing for high product yield often requires diverting resources away from growth, which can result in low volumetric productivity due to insufficient biomass concentration in the bioreactor [9].

Q2: What is the practical difference between yield and productivity, and why does it matter for my bioprocess? While both are critical, they represent different aspects of process economics:

- Yield: The efficiency of converting the substrate into the desired product (e.g., grams of product per gram of substrate). A high yield minimizes raw material costs [9].

- Productivity (Volumetric): The amount of product formed per unit volume of the bioreactor per unit time (e.g., grams per liter per hour). A high productivity reduces capital costs by maximizing the output of a given bioreactor size [9]. A high-yield strain with a very low growth rate may have low productivity, making the process economically unviable despite efficient substrate use [9].

Q3: My model predicts high product titers, but my actual bioreactor experiments show accumulation of unexpected byproducts. Why does this happen? Constraint-based models, like those used in Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), predict what the metabolic network can do under optimal conditions, but they do not always capture full cellular regulation. Byproduct secretion can occur due to:

- Kinetic limitations: Enzyme catalytic rates or metabolite transport may not be optimal.

- Redox imbalance: The cell may produce byproducts to regenerate essential cofactors (e.g., NAD+) that are not balanced in your engineered pathway.

- Regulatory effects: Native allosteric regulation or transcriptional control not included in the model can activate alternative pathways.

Q4: What does "growth-coupled production" mean, and how can it help stabilize my production strain? Growth-coupled production is a design principle where you engineer the strain so that the production of your target metabolite becomes obligatory for growth [10]. This links production directly to the evolutionary pressure to grow, making the production trait more stable over long-term fermentation and during adaptive laboratory evolution [10]. Computational methods like OptKnock can identify gene knockout strategies that enforce this coupling [10].

Q5: How can multi-objective optimization help me design a better strain? Single-objective optimization (e.g., only maximizing yield) often leads to strains with unacceptable trade-offs (e.g., no growth). Multi-objective optimization allows you to simultaneously optimize for several conflicting goals, such as product yield, biomass growth rate, and minimization of byproducts [3]. The output is a set of Pareto-optimal solutions—strains where you cannot improve one objective without making another worse. This provides a spectrum of optimal designs from which you can choose the best compromise for your specific process [3] [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Product Titer Despite High Predicted Yield

Symptoms: The strain grows well, and the calculated yield from consumed substrate is high, but the final concentration (titer) of the product in the bioreactor is low.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Biomass Density | Measure final dry cell weight. Check growth curve for early stationary phase or cell death. | - Use a fed-batch process to achieve higher cell densities [9].- Optimize media composition to support robust growth. |

| Poor Productivity | Calculate the volumetric productivity over the fermentation timeline. | Use dynamic models (like dFBA) to identify strains with a better balance of growth and production, rather than just yield [9]. |

| Product Degradation or Volatilization | Check chemical stability of product under fermentation conditions (pH, temperature). | Modify bioreactor conditions (e.g., pH control, gas stripping) to prevent product loss. |

Problem: Unwanted Byproduct Secretion

Symptoms: Accumulation of byproducts (e.g., acetate, lactate, glycerol) that compete for carbon and can inhibit growth or downstream purification.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient Redox Balance | Measure intracellular NAD+/NADH ratios. Check if byproduct is a redox sink (e.g., glycerol). | - Introduce heterologous genes to create a synthetic NADH sink.- Knock out genes for major byproduct-forming reactions (e.g., lactate dehydrogenase, ldhA) [3]. |

| Overflow Metabolism | Analyze metabolic fluxes during high substrate uptake. Common in rich media or with high sugar concentrations. | - Control substrate feeding rate in fed-batch to avoid overflow.- Engineer the central metabolism to have higher capacity (e.g., amplify TCA cycle). |

| Incomplete Pathway Design | Use (^{13})C Metabolic Flux Analysis ((^{13})C-MFA) to map active fluxes in your engineered strain. | Ensure your heterologous pathway is correctly integrated and that competing native pathways are sufficiently down-regulated. |

Problem: Model Predictions Do Not Match Experimental Results

Symptoms: Computational models suggest high flux to a product, but experimental measurements show minimal production.

Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Model Constraints | Verify the model's uptake/secretion rates and biomass composition match your experimental setup. | Re-constrain the model with experimentally measured uptake rates and perform flux variability analysis (FVA) to check feasibility. |

| Missing Regulatory Constraints | Check literature for known post-translational regulation (e.g., inhibition) of key enzymes in your pathway. | Incorporate regulatory information into your model or use kinetic models to better predict flux [6]. |

| Non-Optimal Enzyme Expression | Measure transcript (RNA-seq) and protein (proteomics) levels for pathway enzymes. | Use characterized promoters and RBS libraries to tune the expression of each enzyme for optimal flux balance [11]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Dynamic FBA (dFBA) for Bioprocess Prediction

This protocol outlines how to simulate the dynamic behavior of a metabolic model in a bioreactor, which is essential for predicting titer and productivity, not just yield [9].

Methodology:

- Base Model: Start with a genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., iJO1366 for E. coli).

- Define Production Envelope: Calculate the Pareto frontier of product flux vs. biomass flux using a constraint-based modeling toolbox (e.g., COBRA Toolbox) [9].

- Create Hypothetical Strains: Sample multiple points along the production envelope, each representing a hypothetical strain with a different yield/growth trade-off.

- Set Up Dynamic Simulation: Use a framework like DyMMM. The core equations model the bioreactor [9]:

- Biomass Accumulation:

dX/dt = μ * X - (F_in / V) * X - Substrate Consumption:

dS/dt = -v_s * X + (F_in / V) * (S_feed - S) - Product Formation:

dP/dt = v_p * X - (F_in / V) * P - Flux Solution: At each time step, fluxes (

v_s,v_p,μ) are calculated by solving an FBA problem:max c^T * v, subject toS * v = 0andlb ≤ v ≤ ub.

- Biomass Accumulation:

- Run Simulation: Integrate the system of equations over the desired fermentation time (e.g., using ODE45 in MATLAB).

- Evaluate Performance: From the simulation output, calculate the final product titer (T), overall yield (Y), and average volumetric productivity (P) [9].

Protocol: Multi-objective Strain Design using OptKnock and GDLS

This protocol uses bi-level optimization to identify gene knockout strategies for growth-coupled production [10] [1].

Methodology:

- Problem Formulation: The problem is structured as a bi-level optimization, where the outer problem maximizes product flux, and the inner problem maximizes biomass growth, subject to a set of reaction knockouts (

y_j), represented by binary variables [1]. - Mathematical Formulation:

- Inner Problem (Cell Growth):

max v_biomasssubject toS * v = 0,v_min ≤ v ≤ v_max. - Outer Problem (Engineering Strategy):

max v_productsubject to the inner problem andv_j = 0 if y_j = 1,∑ (1 - y_j) ≤ K, whereKis the maximum number of knockouts.

- Inner Problem (Cell Growth):

- Algorithm Selection:

- Implementation:

- Use the COBRA Toolbox or dedicated strain design software.

- Define the target product and the maximum number of knockouts (K).

- Run the algorithm to obtain a list of suggested gene deletion targets.

Signaling Pathways & Workflows

Diagram: Multi-objective Strain Design & Validation Workflow

Diagram: Trade-off Between Key Metabolic Objectives

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and computational tools for conducting multi-objective optimization and validation in metabolic engineering.

| Category | Item / Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Models | Genome-Scale Model (e.g., iJO1366, iMM904) | A mathematical representation of an organism's metabolism, used as the foundation for in silico predictions and strain design [10] [1]. |

| Software & Toolboxes | COBRA Toolbox | A MATLAB suite for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis. Used for FBA, production envelope calculation, and implementing strain design algorithms [9]. |

| Software & Toolboxes | OptFlux | A software platform for Metabolic Engineering tasks, including strain optimization using algorithms like OptKnock [12]. |

| Analytical Tools | GC-MS / LC-MS | Gas/Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Used for precise identification and quantification of metabolites, products, and byproducts for model validation [11]. |

| Analytical Tools | Biosensors | Engineered biological components that report on the concentration of a target metabolite, enabling high-throughput screening of strain libraries [11]. |

| Strain Construction | CRISPR-Cas9 System | Enables precise gene knockouts, knock-ins, and regulatory edits as predicted by computational models [11]. |

The Limitations of Single-Objective Approaches

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My single-objective strain optimization for succinic acid production has stalled. The strain grows well but has low productivity. What is happening? This is a classic symptom of a poorly balanced metabolic network. You are likely experiencing metabolic burden, where resources are diverted toward rapid growth (biomass) at the expense of the product pathway. Single-objective optimization, such as only maximizing growth rate in a Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) model, fails to capture the inherent trade-off between microbial growth and product synthesis [13] [14].

Q2: Why does my model predict high product yield, but the lab results are disappointing? Your single-objective model is likely missing critical physiological constraints. In silico models that optimize for a single output (e.g., product flux) often overlook real-world complexities such as:

- Enzyme burden: High expression of pathway enzymes can overwhelm cellular machinery [14].

- Thermodynamic constraints: The model may propose flux distributions that are kinetically or thermodynamically infeasible [4].

- Toxic intermediate accumulation: The objective function does not penalize the buildup of metabolites that inhibit growth or production [4].

Q3: How can I account for both yield and productivity in my design?

You need to move to a multi-objective framework. Instead of a single goal, you optimize for two or more conflicting objectives simultaneously. A common approach is to use an objective function like Biomass-Product Coupled Yield (BPCY), which balances growth (G), product formation (P), and substrate uptake (S): BPCY = (P * G) / S [13]. This prevents the model from sacrificing all growth for product, or vice-versa.

Q4: What is the practical drawback of manually tuning a single-objective function? The process is semi-blind and inefficient. You must repeatedly guess a scalar reward function (e.g., a weighted combination of goals), run an optimization, check the result, and re-adjust. This does not systematically explore trade-offs and puts the burden of understanding the complex problem on the engineer, rather than providing a set of clear options for a well-informed decision [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Product Titer Despite High Predicted Flux

Symptoms:

- In silico FBA simulation predicts high product flux.

- Experimental validation shows low extracellular product concentration.

- Cell growth may be slower than predicted.

Diagnosis Procedure:

- Calculate the Metabolic Burden: Quantify the protein synthesis demand of your engineered pathway. Compare the ribosomal usage of your production strain to a wild-type strain.

- Profile Intermediate Metabolites: Use LC-MS to check for the accumulation of pathway intermediates, indicating a kinetic or regulatory bottleneck not captured by the model [4].

- Analyze Time-Series Data: Measure substrate, biomass, and product concentrations over time. A single end-point measurement often misses the dynamics where trade-offs occur.

Solution: Adopt a multi-objective optimal control framework. Instead of maximizing just product at one time point, optimize the dynamic profile of enzyme expression to balance multiple goals across the fermentation timeline. This can predict a "just-in-time" enzyme activation strategy that minimizes burden while maximizing production [4].

Problem: Genetically Unstable Engineered Strain

Symptoms:

- Loss of production capability after serial passaging.

- Genetic rearrangements or loss of pathway genes.

Diagnosis Procedure:

- Check Plasmid Copy Number: If using plasmid-based expression, verify that the copy number is stable over generations.

- Sequence the Pathway: Identify mutations or deletions in the engineered genes.

Solution: The single-objective of maximizing product forced the cell into a high-stress state that is not evolutionarily stable. A multi-objective design should include genetic stability as a goal.

- Integrate genes into genomic safe harbors: Use bioinformatics tools to identify chromosomal locations that allow high, stable expression without compromising fitness [14].

- Use multi-objective algorithms: Algorithms like OptGene or Simulated Annealing can be configured to select for gene deletions that not only improve product yield but also maintain a sufficiently high growth rate, leading to more robust and stable strains [13].

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Objective Strain Optimization using BPCY

This protocol outlines a computational method for identifying gene knockout targets that balance product yield and growth.

1. Define the Multi-Objective Problem:

- Objective Function: Formulate the Biomass-Product Coupled Yield (BPCY).

- Decision Variables: The set of potential gene knockouts.

- Constraints: The stoichiometric and capacity constraints of the genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., iJO1366 for E. coli).

2. Configure the Optimization Algorithm:

- Tool: Use a meta-heuristic algorithm such as Simulated Annealing (SA) or a Set-based Evolutionary Algorithm (SEA) [13].

- Representation: Use a variable-length set-based representation for the knockouts, allowing the algorithm to find the optimal number of deletions.

- Parameters (Example for SA):

- Initial temperature: 100

- Cooling rate: 0.95

- Number of iterations: 50,000

3. Run the Optimization:

- For each candidate knockout set (generated by the SA/SEA), simulate the mutant phenotype using Flux Balance Analysis (FBA).

- Calculate the BPCY value from the simulated fluxes.

- Iterate until convergence or a maximum number of evaluations is reached.

4. Validate the Solution:

- In silico: Analyze the Pareto front of solutions that trade off growth versus product yield.

- In vivo: Select the top 3-5 proposed knockout strategies, construct the strains, and characterize them in bioreactors to measure the BPCY and genetic stability.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Multi-Objective Strain Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model (e.g., iJO1366, Yeast8) | A computational representation of metabolism. Serves as the constraint set for in silico FBA and optimization [13]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Toolkit | Enables precise genomic integration of pathway genes into identified "safe harbors" to minimize metabolic burden and improve genetic stability [14]. |

| LC-MS/MS System | Used for metabolomics profiling to detect the accumulation of toxic intermediates and validate/refine model predictions [4]. |

| Biofoundry Automation | Allows high-throughput combinatorial testing of promoter/gene variants to empirically balance expression levels in a pathway, providing data for multi-objective models [14]. |

| Simulated Annealing Software | A meta-heuristic optimization algorithm effective at solving the combinatorial problem of finding optimal gene knockout sets for multi-objective functions like BPCY [13]. |

Comparative Analysis: Single vs. Multi-Objective Outcomes

Table 2: Comparing Optimization Approaches for Succinic Acid Production in S. cerevisiae

| Feature | Single-Objective (Maximize Product Flux) | Multi-Objective (Maximize BPCY) |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Product Yield | High | Moderate |

| Theoretical Growth Rate | Very Low | Good |

| Predicted Productivity | Low | High |

| Genetic Stability | Poor | Good |

| Metabolic Burden | Very High | Managed |

| Industrial Relevance | Low | High |

Workflow Visualization

Multi-Objective Strain Optimization Workflow

Metabolic Burden from Single-Objective Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the Pareto set and Pareto front in the context of multi-objective optimization?

In multi-objective optimization, the Pareto set and Pareto front are fundamental concepts. The Pareto set consists of all the possible solutions that are not dominated by any other solution in the search space. A solution is considered non-dominated if no other solution exists that is better in at least one objective without being worse in any other objective. The Pareto front is the set of objective vectors corresponding to the solutions in the Pareto set. It visually represents the trade-offs between different objectives, showing where improving one objective inevitably worsens another. Each point on this front represents a unique, optimal trade-off [16].

FAQ 2: Why is multi-objective optimization particularly important in metabolic engineering?

Metabolic engineering aims to optimize microorganisms for biotechnology applications, such as producing a metabolite of interest. Traditionally, the focus was on optimizing a single criterion, like the synthesis rate of a target metabolite. However, biological systems are interconnected and involve complex regulatory loops. Optimizing for maximum yield alone may lead to unrealistic or unviable cellular states, such as an excessive metabolic burden on the host or harmful accumulation of intermediate compounds. Multi-objective optimization allows researchers to balance several key biological criteria simultaneously—such as maximizing product titer, maximizing biomass, and minimizing byproduct concentrations—to identify robust and viable engineering strategies [6] [17].

FAQ 3: What is a common challenge when analyzing the results of a multi-objective optimization, and how can it be addressed?

A significant challenge is that the Pareto set can contain a very large, or even infinite, number of optimal solutions, making it impractical to test all of them in the laboratory. To address this, researchers use Pareto filters and other multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) methods. These tools help to screen and rank the alternatives, identifying a preferred subset of solutions. For example, one might focus on "knee" points, which offer a significantly better trade-off, or on solutions that are robust to small parameter changes, thereby narrowing down the options to the most promising candidates for experimental validation [17].

Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses common issues encountered during multi-objective optimization experiments in metabolic engineering.

Table: Common Problems and Solutions in Multi-Objective Optimization

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| The optimization algorithm fails to converge or finds poor solutions. | The problem is non-convex and the algorithm is trapped in a local optimum. | Use global optimization methods specifically designed for non-linear models (e.g., GMA models) to guarantee finding a solution near the global optimum [17]. |

| The Pareto front is too large to analyze effectively. | The number of Pareto-optimal solutions is overwhelming for decision-making. | Apply a Pareto filter to identify a preferred subset, such as solutions with the best trade-off slopes ("knees") or those that are least sensitive to parameter variations [17]. |

| The resulting enzymatic profiles are biologically unrealistic or too complex. | The optimization did not sufficiently penalize the number or extent of enzymatic changes. | Include the number of enzymatic changes or the metabolic burden as an explicit objective in the multi-objective formulation [17]. |

| Visualizing the trade-offs between more than three objectives is difficult. | Human perception limits easy visualization of high-dimensional data. | Use dimensionality reduction techniques or parallel coordinate plots. For 2- or 3-objective problems, always plot the 2D/3D Pareto front for direct visual analysis [16]. |

Experimental Protocol: Identifying Pareto-Optimal Enzymatic Profiles

This protocol outlines the methodology for performing multi-objective optimization on a kinetic metabolic model to identify a preferred subset of enzymatic profiles, as described by Pozo et al. (2012) [17].

Objective

To identify a set of Pareto-optimal enzymatic modifications that balance the trade-off between maximizing a desired metabolic flux (e.g., ethanol production) and minimizing associated cellular costs (e.g., intermediate metabolite concentrations or the number of enzymatic changes).

Materials and Equipment

- Kinetic Metabolic Model: A validated, non-linear kinetic model of the target metabolic network (e.g., a Generalized Mass Action (GMA) model).

- Computational Environment: Software capable of performing global optimization (e.g., MATLAB, Python with suitable libraries).

- Multi-Objective Optimization Solver: An implementation of a suitable algorithm (e.g., the epsilon-constraint method for global optimization).

Procedure

Problem Formulation:

- Define Objectives: Formally state the objective functions. A typical setup includes:

- Objective 1: Maximize the production flux of a target metabolite (e.g., ethanol).

- Objective 2: Minimize the Euclidean norm of the vector of logarithmic enzyme concentrations, which reflects the metabolic burden of enzymatic changes [17].

- Define Decision Variables: These are typically the levels of enzymatic activities that can be manipulated.

- Set Constraints: Define constraints that ensure cell viability, such as bounds on internal metabolite concentrations and reaction fluxes.

- Define Objectives: Formally state the objective functions. A typical setup includes:

Model Input:

- Provide the optimization algorithm with the full set of model equations and parameters that define the metabolic network.

Optimization Execution:

- Apply a multi-objective global optimization method, such as the epsilon-constraint-based heuristic, to generate a set of solutions that approximate the true Pareto front [17].

Post-Optimal Analysis (Pareto Filtering):

- Filter Solutions: Process the resulting Pareto set with a Pareto filter to reduce the number of solutions based on pre-defined decision-maker preferences.

- Identify "Knee" Points: Look for solutions on the Pareto front where a small improvement in one objective would lead to a large deterioration in the other—these often represent the most attractive compromises.

Validation (In Silico):

- Simulate the metabolic network using the identified enzymatic profiles from the filtered Pareto set to verify the predicted behavior.

Data Analysis

- Plot the Pareto front, typically with one objective on each axis, to visualize the trade-off.

- Analyze the enzymatic profiles (e.g., the pattern and magnitude of up- and down-regulation) corresponding to different points on the front to understand the biological strategies they represent.

Conceptual Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for conducting multi-objective optimization in metabolic engineering, from model preparation to the final selection of engineering targets.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Multi-Objective Optimization in Metabolic Engineering

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Kinetic Model (e.g., GMA) | A non-linear mathematical representation of the metabolic network that captures regulatory effects and reaction kinetics. It is the core "reagent" for in silico optimization [17]. |

| Global Optimization Algorithm | A computational method designed to find the global optimum of a problem, overcoming non-convexities that trap local optimization solvers. Essential for reliable results in non-linear models [17]. |

| Multi-Objective Solver (e.g., ε-Constraint) | The specific algorithm used to handle multiple, conflicting objectives and generate the Pareto set of optimal solutions [17]. |

| Pareto Filter | A computational tool for post-processing the results to identify a smaller, more manageable subset of optimal solutions based on additional criteria (e.g., best trade-offs) [17]. |

| Colorblind-Friendly Palette | A predefined set of colors (e.g., Okabe-Ito, ColorBrewer) used for data visualization to ensure that Pareto fronts and other graphs are interpretable by all viewers, including those with color vision deficiency [18] [19]. |

Computational Frameworks and Algorithms for Multi-Objective Strain Design

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is OptPipe and what is its primary function in metabolic engineering? OptPipe is a computational pipeline designed for optimizing metabolic engineering targets through a consensus approach. It integrates predictions from multiple distinct optimization algorithms to generate robust hypotheses for genetic modifications. Its primary function is to identify optimal gene knockout strategies that enhance the production of target biochemicals while maintaining cellular growth [20] [21].

2. Which algorithms does OptPipe integrate? The pipeline combines solutions from several knockout prediction procedures, including OptKnock, RobustKnock, OptGene, and RobOKoD. It also incorporates a screening method based on Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) to exhaustively enumerate deletion strategies [20].

3. How does OptPipe rank the proposed genetic modification strategies? OptPipe ranks suggested mutants using a statistical method called the rank product test. It combines the rankings from the different algorithms based on several performance criteria, such as maximal growth rate, maximal target production, and minimal target production. The results are then corrected for multiple comparisons to control the False Discovery Rate (FDR), providing a statistically robust list of candidates [20].

4. What is the purpose of the pre-processing step? The pre-processing step filters the network reactions to create a manageable set of candidate reactions for deletion. It removes essential reactions (whose deletion prevents growth), blocked reactions (which carry no flux), and synthetic/export reactions, thereby significantly reducing the computational search space and time [20].

5. A common error states "Problem gets infeasible" during the pre-processing step. What does this mean and how can it be resolved? This error typically occurs when the model constraints are too restrictive. To resolve it:

- Action 1: Verify the consistency of your input data, including the genome-scale model and any experimental constraints.

- Action 2: Ensure that the applied constraints (e.g., nutrient uptake rates) do not inadvertently make the model unable to produce biomass or the target metabolite. Loosening the bounds on key exchange reactions may help restore feasibility [20].

6. What should I do if the pipeline produces an overly long list of candidate strategies? You can refine the results by applying stricter biological filters.

- Action 1: Adjust the biomass threshold to filter out mutants with insufficient growth rates. The default threshold is 0.1 h⁻¹ [20].

- Action 2: Filter out strategies that result in zero maximal target production [20].

- Action 3: Prioritize candidates that consistently rank high across the different algorithms used within OptPipe, as the consensus approach is designed to yield more reliable predictions [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High False Discovery Rate (FDR) in Ranked Results

Problem: The final list of candidate mutants includes many strategies that are statistically insignificant after multiple test correction.

| Potential Cause | Solution | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Too many hypotheses (deletion strategies) are being tested simultaneously. | Apply stricter pre-processing filters to reduce the initial candidate pool. | Controlling the FDR becomes more challenging as the number of tests increases. Reducing the number of candidates (N) improves the power of the rank product statistic [20]. |

| The performance criteria used for ranking are not sufficiently discriminatory. | Incorporate additional biological constraints or performance metrics, such as a minimum flux for cofactor regeneration, into the ranking step. | Adding relevant criteria helps to better distinguish between high-quality and low-quality solutions, leading to a more meaningful consensus ranking. |

Protocol: Enhanced Pre-processing for FDR Control

- Identify Essential Reactions: Perform Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) with single reaction deletions. A reaction is essential if its deletion reduces the maximum biomass below a set threshold (e.g., < 1% of wild-type growth) [20].

- Identify Blocked Reactions: Use Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) to find reactions that cannot carry any flux under the defined conditions [20].

- Filter Non-Gene Associated Reactions: Remove synthetic, exchange, and transport reactions that lack gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations.

- Apply Filters: Remove the reactions identified in steps 1-3 from the candidate deletion set before running the main OptPipe pipeline.

Issue: Discrepancy Between In Silico Predictions and Experimental Validation

Problem: A gene knockout strategy predicted by OptPipe to increase target production fails to do so in the wet-lab experiment.

| Potential Cause | Solution | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| The model does not account for all regulatory mechanisms or kinetic constraints. | Use the MOMA (Minimal Metabolic Adjustment) framework within the pipeline to predict flux distributions, as it may provide a more realistic simulation of mutant metabolism. | MOMA assumes the mutant's flux distribution is close to the wild-type's, avoiding the overly optimistic assumption of optimal growth in the knockout strain [20]. |

| The model's constraints do not reflect the actual experimental conditions. | Incorporate quantitative experimental data (e.g., substrate uptake rates) as constraints in the model. Allow for a flexibility (e.g., 20%) in the bounds to account for biological variability [20]. | Constraint-based models are context-dependent. Using accurate constraints ensures the in silico environment mirrors the in vivo conditions. |

Protocol: Integrating Experimental Data for Improved Predictions

- Gather Data: Obtain measured uptake/secretion rates and growth rates from cultivations of the wild-type strain.

- Set Constraints: Apply these data as constraints to the corresponding reactions in the model.

- Allow Flexibility: To account for inherent experimental variability and potential changes in the engineered strain, apply a 20% flexibility to the lower and upper bounds derived from the experimental data [20].

- Re-run Analysis: Execute the OptPipe pipeline with the updated, data-constrained model.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Case Study: Maximizing Malonyl-CoA inCorynebacterium glutamicum

This protocol details the application of OptPipe for enhancing the production of malonyl-CoA, a key precursor for phenolic compounds [20] [21].

1. Methodologies

- Model: A genome-scale metabolic model of Corynebacterium glutamicum.

- OptPipe Workflow:

- Pre-processing: Candidate reactions were selected by removing essential, blocked, and non-gene-associated reactions.

- Optimization: The OptKnock, RobustKnock, OptGene, and RobOKoD algorithms were run on the candidate set.

- Screening: Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) was performed on all possible gene deletions to calculate maximal and minimal malonyl-CoA production under optimal growth.

- Ranking: The results were merged, and mutants were ranked based on:

- Maximal growth rate (FBA)

- Minimal malonyl-CoA production (FVA, given max growth)

- Maximal malonyl-CoA production (FVA, given max growth)

- Consensus: The rank product test was applied, and FDR was controlled using q-values.

2. Key Experimental Results The following table summarizes the in silico predictions and subsequent in vivo validation for the top candidate identified by OptPipe [20] [21].

| Strain | Predicted Growth Rate (h⁻¹) | Predicted Malonyl-CoA Increase | Experimentally Measured Malonyl-CoA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild Type | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline |

| ΔsdhCAB (Succinate Dehydrogenase) | Maintained > 0.1 h⁻¹ | Significant Increase | Confirmed Significant Increase |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram Title: OptPipe Consensus Workflow for Metabolic Engineering

Multi-Objective Optimization Logic

Diagram Title: Multi-Objective Optimization in OptPipe

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key resources used in conjunction with OptPipe for the C. glutamicum malonyl-CoA case study.

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Role in the OptPipe Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model | A stoichiometric representation of the organism's metabolism (e.g., iCglΔNR for C. glutamicum). | The foundational in silico framework on which all FBA, FVA, and optimization algorithms are executed [20]. |

| OptPipe Software | A pipeline integrating multiple optimization algorithms for consensus prediction. Available at: https://github.com/AndrasHartmann/OptPipe [20] [22]. | The core computational platform that automates the pre-processing, optimization, and consensus ranking steps. |

| Constraint-Based Modeling Toolbox (e.g., COBRA) | A software suite (like the COBRA Toolbox) for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis of metabolic networks. | Provides the computational backbone for performing FBA, FVA, and often includes implementations of algorithms like OptKnock used by OptPipe [21]. |

| Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) | A computational technique to determine the minimum and maximum possible flux through each reaction in a network. | Used in the screening method to calculate the potential range of target production for each mutant and to identify blocked reactions in pre-processing [20]. |

Genetic Algorithms (OptGene) for Complex, Non-Linear Engineering Objectives

Within the framework of multi-objective optimization in metabolic engineering research, genetic algorithms (GAs) provide a powerful, flexible approach for identifying optimal genetic interventions. The OptGene method leverages these algorithms to solve complex, non-linear strain design problems that are often intractable for traditional mixed-integer linear programming methods [23]. This heuristic search method is particularly valuable for optimizing sophisticated cellular objectives, such as productivity (a non-linear function) or for simultaneously maximizing product yield while minimizing by-product formation and the number of genetic modifications [24]. By efficiently exploring the vast combinatorial space of possible gene knockouts, OptGene enables researchers to identify non-intuitive engineering targets that couple cellular growth with the production of high-value chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and biofuels [23] [25].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using OptGene over other strain design algorithms like OptKnock?

OptGene offers two major advantages. First, it demands relatively less computational time, enabling the solution of larger problems and the identification of a family of near-optimal solutions. Second, its formulation allows the optimization of non-linear objective functions or the incorporation of non-linear constraints, which are critical for many industrially relevant objectives like productivity [23].

Q2: My OptGene run is converging to a sub-optimal solution. What parameters should I adjust?

Premature convergence is a known drawback of genetic algorithms. To mitigate this, focus on the parameters that control the balance between exploration and exploitation. Increasing the mutation rate can reintroduce genetic diversity, while a larger population size helps maintain a broader search of the solution space. Comprehensive parameter sensitivity analyses are recommended to find the optimal settings for your specific problem [24].

Q3: What does the error "The value of 'targetRxn' is invalid. It must satisfy the function: @(x)ischar(x)" mean?

This error, encountered in implementations like the COBRA Toolbox, typically indicates an issue with input formatting. It often occurs when cell arrays ({}) are used for the targetRxn or substrateRxn inputs instead of a character array or string scalar. Ensure these variables are defined as simple character vectors [26].

Q4: How does OptGene handle the prediction of mutant phenotypes?

The algorithm itself is independent of the phenotype prediction method. The fitness of a candidate mutant (individual) can be calculated using Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), Minimization of Metabolic Adjustment (MOMA), Regulatory ON/OFF Minimization (ROOM), or any other suitable algorithm. This flexibility allows researchers to choose the prediction method most appropriate for their engineered strain [23].

Q5: Can OptGene incorporate non-native reactions into a host organism?

Yes. Advanced GA frameworks can be extended to simultaneously optimize the insertion of non-native reactions from a preprocessed pool of candidates while identifying gene knockout targets. This mimics the functionality of frameworks like OptStrain and adds a significant level of sophistication to the strain design process [24].

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Errors and Solutions

| Error Message | Probable Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

TypeError: show() got an unexpected keyword argument 'notebook_handle' [27] |

Version incompatibility with plotting libraries. | Disable plotting by setting the plot parameter to False in the run method. |

Error using optGene ... The value of 'targetRxn' is invalid. [26] |

Input variable is a cell array instead of a character array. | Provide the reaction name as a string (e.g., 'EX_etoh(e)') without cell braces {}. |

Expected a string scalar or character vector... [26] |

Input variable is of a numeric type (double). |

Ensure the targetRxn, substrateRxn, and other reaction identifiers are passed as text. |

| Premature convergence to a sub-optimal solution [24] | Poor balance between exploration and exploitation. | Increase the mutation rate and/or population size; conduct parameter sensitivity analysis. |

Performance and Optimization

Problem: Optimization is running very slowly.

- Solution: Pre-process the model to remove duplicate, dead-end, and lethal reactions. This reduces the problem size and the number of local optimal solutions, speeding up the search [23].

Problem: The algorithm is not finding any viable knockout strategies.

- Solution: Verify the constraints on the model, particularly the substrate uptake and oxygen conditions. Ensure that the

fraction_of_optimumparameter for the biomass objective is not set too restrictively, as this may over-constrain the solution space [28].

Key Experimental Parameters and Reagents

Core Algorithm Parameters for Reliable Optimization

The performance of an OptGene simulation is highly sensitive to its parameter settings. The following table summarizes key parameters and their impact, derived from comprehensive sensitivity analyses [24].

| Parameter | Description | Impact & Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Mutation Rate | Probability of randomly changing a gene deletion target. | Prevents premature convergence; too high a rate may destroy good solutions. |

| Population Size | Number of candidate solutions (individuals) in each generation. | A larger size improves search space exploration but increases computation time. |

| Number of Generations | Total number of evolutionary iterations. | Must be sufficient for fitness convergence; can be set with a maximum limit. |

| Max Evaluations | Total number of mutant phenotypes evaluated. | A key termination criterion; ensures the run finishes in a reasonable time. |

| Crossover Method | Mechanism for combining two parent solutions (e.g., one-point, uniform). | Affects the mixing of genetic material; uniform crossover can enhance diversity. |

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in OptGene Experiments |

|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model | A stoichiometric reconstruction of metabolism (e.g., iJO1366 for E. coli); serves as the in silico platform for testing knockout strategies [28]. |

| Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Rules | Logical associations that map genes to reactions; essential for translating a gene knockout into a reaction deletion in the model [29]. |

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | A linear programming approach used to simulate the metabolic phenotype (flux distribution) of a wild-type or mutant strain under steady-state [29]. |

| Phenotypic Phase Plane | A visualization of the relationship between growth and product formation; helps in interpreting and validating OptGene results [28]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing an OptGene Run

The following diagram illustrates the core iterative workflow of the OptGene algorithm, from the initial population to the final identification of optimal gene knockout strategies.

Detailed Step-by-Step Methodology

The protocol below outlines a typical OptGene run using the cameo Python package, demonstrated for acetate overproduction in E. coli.

Model Loading and Pre-processing

- Load a genome-scale metabolic model (e.g.,

iJO1366for E. coli). - Pre-process the model to remove duplicate and dead-end reactions, which reduces the search space and helps avoid local optima [23].

- Load a genome-scale metabolic model (e.g.,

Define the Engineering Objective

- Clearly specify the target reaction (e.g.,

'EX_ac_e'for acetate secretion). - Define the biomass reaction (the cellular objective, e.g.,

'BIOMASS_Ec_iJO1366_core_53p95M'). - Identify the substrate uptake reaction (e.g.,

'EX_glc__D_e'for glucose) [28].

- Clearly specify the target reaction (e.g.,

Configure and Run OptGene

- Initialize the

OptGeneclass with the model. - Execute the

runmethod with defined parameters. Themax_evaluationsparameter is critical for limiting computational time.

- Initialize the

Analyze and Validate Results

- The algorithm returns a set of potential knockout strategies (reactions and genes).

- Examine the predicted target flux, biomass flux, and fitness (e.g., biomass-coupled product yield) for each solution.

- Use techniques like Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) to assess the robustness of the predicted phenotype [28] [29].

- Visually inspect the location of knockouts within the metabolic network to ensure biological feasibility.

Parameter Sensitivity and Advanced Configuration

Navigating Parameter Relationships

Optimizing the interplay between key parameters is crucial for algorithm performance. The diagram below depicts the core relationships and trade-offs to consider when configuring OptGene.

Advanced Multi-Objective Implementation

For complex engineering tasks, OptGene can be extended to handle multiple objectives simultaneously. The following table contrasts the standard implementation with an advanced multi-objective setup.

| Feature | Standard OptGene | Advanced Multi-Objective GA |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Maximize product yield or flux [23]. | Find a Pareto-optimal set of solutions balancing multiple goals [24]. |

| Secondary Objectives | Not explicitly considered. | Minimize number of knockouts; maximize productivity; maximize yield [24]. |

| Fitness Function | Single, often linear, objective (e.g., ( bpcy = \frac{(Biomass \times Product)}{Substrate} )) [28]. | Composite or Pareto-based ranking evaluating all objectives simultaneously. |

| Solution Output | A single "best" solution or a ranked list. | A family of solutions representing trade-offs (the Pareto front). |

| Implementation Tip | Use the basic OptGene.run() method. |

Requires a custom fitness function that aggregates or ranks based on multiple criteria. |

Constraint-Based Modeling and Bi-Level Optimization (OptKnock, RobustKnock)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between OptKnock and RobustKnock?

OptKnock is a bi-level optimization framework that identifies reaction knockouts to maximize a biochemical production rate, under the assumption that the mutant cell will maximize its biomass growth rate [30] [31]. However, this can lead to overly optimistic designs, as alternate optimal solutions might exist where the cell achieves the same growth but reduces production [30] [32]. RobustKnock improves upon this by using a max-min optimization to guarantee a minimal production rate even in the presence of alternate optimal solutions, making the design more robust [32].

FAQ 2: When should I use MOMAKnock or ROOM instead of OptKnock?

You should consider MOMAKnock or ROOM when the assumption that knockout mutants immediately achieve maximum growth is unrealistic. These methods are based on the observation that engineered strains often have flux distributions that minimize metabolic adjustment from the wild-type state rather than maximizing growth, especially before long-term evolutionary adaptation [33] [31]. MOMAKnock uses a quadratic programming problem to minimize the Euclidean distance (L2-norm) of flux changes [33], while ROOM uses a mixed-integer linear programming problem to minimize the number of significant flux changes (L0-norm) [31].

FAQ 3: What are the common solution strategies for bi-level optimization problems in strain design?

The most common method involves transforming the bi-level problem into a single-level equivalent. For methods with a linear inner problem (like OptKnock), this is often done by replacing the inner problem with its dual constraints and enforcing strong duality [30] [34]. For methods with a quadratic inner problem (like MOMAKnock), an adaptive piecewise linearization algorithm can be used [33]. Another general approach is to use the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) conditions, which is applicable when the inner problem is continuous [34].

FAQ 4: My OptKnock-derived strain is not producing the predicted yield. What could be wrong?

This is a known limitation of the optimistic OptKnock framework. The strain might be operating at an alternate optimal solution where growth is maximized but production is not [31] [32]. To diagnose this, perform Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) on the engineered model to see if the desired production rate is achievable within the range of optimal growth solutions [34]. For future designs, consider using pessimistic frameworks like P-OptKnock or P-ROOM, which are specifically designed to deliver more robust results under model uncertainty and non-cooperative cellular behavior [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Numerical Instabilities or Infeasibilities when Solving the Bi-Level MILP

- Problem: The solver fails to find a solution, returns an infeasible model, or the solution is numerically unstable.

- Solution:

- Verify Inner Problem Feasibility: Ensure that for any given set of knockouts, the inner problem (e.g., FBA for biomass maximization) remains feasible. Check the bounds (

v_min,v_max) on essential reactions, especially the biomass reaction itself [30] [34]. - Check Solver Logs: Look for warnings about numerical precision or ill-conditioned matrices.

- Reformulate using KKT: If using a duality-based transformation, consider switching to a KKT-based reformulation, which has been noted to be more stable and reliable for genome-scale models [34].

- Verify Inner Problem Feasibility: Ensure that for any given set of knockouts, the inner problem (e.g., FBA for biomass maximization) remains feasible. Check the bounds (

Issue 2: The Computed Strain Design is Overly Optimistic and Fails In Vivo

- Problem: The model predicts high production, but experimental results show low yields, even though the strain grows as predicted.

- Solution:

- Switch to a Robust Formulation: Replace OptKnock with RobustKnock, P-OptKnock, or P-ROOM [31] [32]. These methods account for the possibility that the cell might not cooperate with the production objective.

- Use a Different Phenotypic Assumption: The biomass maximization assumption may not hold for your mutant. Implement MOMAKnock, which uses the MOMA criterion, often yielding predictions that agree better with experimental data for knockout strains [33].

- Validate with FVA: Before moving to experiments, use Flux Variability Analysis on the designed mutant to check the range of possible production fluxes at maximum growth. A large variability indicates the design is not robust [34].

Issue 3: The Optimization is Computationally Prohibitive for Large Models

- Problem: The mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) problem takes too long to solve for genome-scale metabolic models.

- Solution:

- Limit Knockouts: Start by searching for a small number of knockouts (e.g., 1-3) and gradually increase [28].

- Use Heuristic Methods: For a larger number of knockouts, use heuristic approaches like OptGene, which uses evolutionary algorithms and can be more efficient for complex searches [28].

- Network Compression: Pre-process the metabolic network to remove blocked reactions and simplify the model, thereby reducing the problem size [30].

Comparison of Major Bi-Level Optimization Methods

The table below summarizes the key methodologies for strain design using bi-level optimization.

| Method | Primary Objective | Inner Problem (Cellular Objective) | Solution Technique | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OptKnock [30] [28] | Max chemical production | Max biomass yield | Bi-level MILP → Single-level MILP via duality | Simple, intuitive formulation |

| RobustKnock [30] [32] | Guarantee min chemical production | Max biomass yield | Max-min MILP | Robust against alternate optimal solutions |

| MOMAKnock [33] | Max chemical production | Min metabolic adjustment (L2-norm) | Bi-level MIQP → Single-level MILP via adaptive linearization | More accurate prediction for knockout fluxes |

| ROOM [31] | Max chemical production | Min number of significant flux changes (L0-norm) | Bi-level MILP | Uses regulatory on/off minimization |

| P-OptKnock / P-ROOM [31] | Max chemical production under worst-case scenario | Max biomass (P-OptKnock) or Min flux changes (P-ROOM) | Pessimistic bi-level optimization → Single-level MIP | Generates robust strategies under model uncertainty |

| OptGene [28] | Max chemical production | Max biomass yield | Heuristic (Evolutionary Algorithm) | Scalable to a large number of knockouts |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing an OptKnock Workflow

This protocol outlines the steps to compute reaction knockout strategies using the OptKnock framework, as demonstrated with the straindesign and cameo toolboxes [30] [28].

1. Model Loading and Preparation

- Load a genome-scale metabolic model in SBML format.

- If necessary, add heterologous pathways for the target chemical. For example, to model 1,4-butanediol (BDO) production, add the necessary metabolites (e.g.,

sucsal_c,14bdo_e) and enzymatic reactions (e.g.,AKGDC,SSCOARx) to the model [30]. - Verify that the pathway is functional by performing FBA with the exchange reaction of the target chemical as the objective.

2. Define the Strain Design Module

- Specify the method (e.g.,

OPTKNOCK). - Define the inner objective, typically the biomass reaction (e.g.,

BIOMASS_Ecoli_core_w_GAM). - Define the outer objective, the exchange reaction of the target chemical (e.g.,

EX_14bdo_e). - Set additional constraints, such as a minimum required growth rate (e.g.,

BIOMASS_Ecoli_core_w_GAM >= 0.5) [30].

3. Configure Knockout Costs and Limits

- Assign a cost of 1 to genes or reactions that are allowed to be knocked out.

- Optionally, remove essential genes (e.g.,

s0001for spontaneous reactions) from the knockout candidate list [30]. - Set the maximum number of knockouts (

max_costormax_knockouts) to limit the search space [30] [28].

4. Execute the Strain Design Computation

- Call the

compute_strain_designsfunction with the model, module, and cost parameters. - Use the

BESTsolution approach to enforce optimality [30]. - The output will be a list of intervention sets, each specifying the reactions to be knocked out.

5. Validate the Proposed Designs

- For each proposed knockout strategy, apply the knockouts to the model by setting the bounds of the corresponding reactions to zero.

- Perform Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) on the production reaction at maximum growth to check if the predicted production is mandatory or if there are alternate optima with lower yield [34].

- This validation step is crucial before proceeding with experimental implementation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Software

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Example Use in Strain Design |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model | A mathematical representation of a metabolic network. | Serves as the in silico platform for simulating metabolism and predicting knockout effects (e.g., iAF1260, iJO1366) [34] [28]. |

| FBA (Flux Balance Analysis) | Constraint-based method to predict steady-state metabolic fluxes. | Solves the inner problem to predict cellular growth phenotype after genetic perturbations [33] [31]. |

| FVA (Flux Variability Analysis) | Determines the range of possible fluxes for each reaction in a network. | Used to validate the robustness of a strain design by checking the variability in production flux at optimal growth [34]. |

| MILP Solver | Software for solving Mixed-Integer Linear Programming problems. | Computes the optimal solution for single-level reformulations of OptKnock and RobustKnock (e.g., Gurobi, CPLEX) [30] [34]. |

| StrainDesign / COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based software suites for constraint-based modeling. | Provides implemented functions for running OptKnock, RobustKnock, and related algorithms [30]. |

| cameo | Python-based software for strain design and metabolic engineering. | Provides high-level APIs for running methods like OptKnock and OptGene [28]. |

Workflow Diagram: Bi-Level Strain Design & Validation

Bi-Level Strain Design and Validation Workflow

Method Evolution Diagram: From OptKnock to Pessimistic Frameworks

Evolution of Bi-Level Optimization Methods in Strain Design

Kinetic Model Integration for Dynamic Multi-Objective Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary advantage of using multi-objective optimization over single-objective approaches for kinetic models in metabolic engineering? Multi-objective optimization (MOO) recognizes that engineering goals often conflict, such as maximizing product yield while minimizing the accumulation of inhibitory by-products like lactate and ammonia [6]. Instead of providing a single "best" solution, MOO generates a set of Pareto-optimal solutions [35]. Each solution on this "Pareto front" represents a different trade-off between the competing objectives, empowering researchers to select a strategy that best aligns with their overall project goals and constraints [36].

FAQ 2: How does the framework handle the uncertainty inherent in biological parts and kinetic parameters? The MOO tuning framework is designed to work with qualitative regions or intervals of parameter values rather than requiring exact, precise numbers [35]. It actively searches for all combinations of kinetic parameters that fulfill the desired dynamic behavior, effectively identifying kinetic motifs—sets of parameters that yield robust circuit performance [35]. This provides experimenters with flexible guidelines for part selection, acknowledging that biological characterization is often subject to variability.

FAQ 3: My dynamic multi-objective optimization algorithm struggles to track changing solutions when the problem environment shifts. What strategies can I use? This is a known challenge in Dynamic Multi-objective Optimization Problems (DMOPs). Effective strategies involve equipping your algorithm to detect changes and respond adaptively [37]. One approach is to use multi-swarm algorithms like dynamic Vector Evaluated Particle Swarm Optimisation (DVEPSO) [38]. Another is to implement restart strategies, where upon detecting an environmental change, the algorithm replaces a portion of its population with new, randomly generated or knowledge-informed solutions to re-explore the search space [37]. Using past solutions to train a predictive model like a Support Vector Machine (SVM) to classify and generate good initial populations for a new environment has also shown validity [39].

FAQ 4: Can this methodology be applied to large-scale, industrially relevant models, such as mammalian cell cultures? Yes. The methodology has been successfully applied to computationally challenging, large-scale models, including a kinetic metabolic model of Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells to optimize antibody production [6]. The approach identified enzymatic modifications that simultaneously increased productivity, biomass, and product titer while keeping inhibitory metabolites low [6] [36]. This demonstrates its applicability to industrially significant and complex host organisms.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Convergence or Inaccurate Pareto Front in Kinetic Model Optimization

Problem Description: The optimization algorithm fails to find a satisfactory set of trade-off solutions, or the resulting Pareto front is poorly defined and does not capture the true trade-offs between objectives.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Verify Model Calibration: Ensure your kinetic model is properly calibrated with reliable initial parameter estimates. An inaccurate model will lead to misguided optimization results [40].

- Check Objective Function Formulation: Review your objective functions. They must accurately and quantitatively encode the desired biological behavior. Poorly formulated objectives will guide the search in the wrong direction [35].

- Analyze Algorithm Parameters: Examine the settings of your multi-objective algorithm (e.g., NSGA-II, SPEA2). Key parameters like population size, crossover, and mutation rates significantly impact performance [38] [41].

Resolution:

- Adopt Advanced Algorithms: Implement state-of-the-art algorithms designed for complex landscapes. For instance, an improved SPEA2 algorithm with path evolution and adaptive step strategy has been shown to accelerate convergence and improve accuracy in kinetic model optimization [41].

- Utilize Global Optimization: For parameter estimation, use a global, multi-objective optimization approach to avoid getting trapped in local optima, which is a common pitfall [40].

- Leverage Visualization Tools: Use software tools that provide level diagrams or other visualizations of multi-objective results to better understand the relationships between parameters and objectives and to diagnose issues with the Pareto front [42].

Issue 2: Failure to Achieve Desired Circuit Behavior Despite Optimal In Silico Parameters

Problem Description: The parameter values identified by the optimization framework fail to produce the expected dynamic behavior when implemented experimentally in the wet-lab.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Check for Context Effects: Investigate whether the presence of a downstream load is influencing your synthetic device's performance, an effect known as retroactivity [35]. The in silico model may not have accounted for this.

- Review Parameter Tunability: Confirm that the parameters identified as key tuning knobs (e.g., enzyme concentrations, promoter strengths) are indeed practical to tune experimentally within the suggested ranges [35].

- Assess Model Fidelity: Evaluate if the kinetic model's structure adequately captures the essential regulatory and metabolic interactions. An oversimplified model may not reflect biological reality.

Resolution:

- Incorporate Context in Design: During the optimization process, incorporate information about the circuit's intended context (e.g., host chassis, genomic location) into the model to account for load effects [35].

- Focus on Parameter Regions: Instead of fixed parameter values, use the MOO framework to obtain qualitative regions or intervals of parameters that produce the desired behavior. This provides a buffer for biological uncertainty [35].

- Iterate with Experimental Data: Use the initial experimental results to refine the kinetic model and restart the optimization process. This model-based design cycle progressively narrows the gap between in silico predictions and wet-lab results.

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Objective Dynamic Optimization of a CHO Cell Metabolic Model

This protocol details the methodology for identifying enzymatic modification targets to enhance antibody production in Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells, as cited in metabolic engineering research [6] [36].

Objectives and Model Definition

Primary Objectives:

- Maximize antibody product titer.

- Maximize biomass growth.

- Minimize the concentration of inhibitory by-products (e.g., lactate, ammonia).

Kinetic Model:

- Utilize a large-scale, compartmented kinetic model of CHO cell metabolism. The model should include uptake kinetics, central carbon metabolism, and antibody production pathways. The model is typically defined by a set of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) representing the mass balance for each metabolite [36].

Optimization Problem Formulation

The dynamic multi-objective optimization problem is formulated mathematically as follows:

Find u(t) that optimizes: [ J[u(t)] = [J1(u(t)), J2(u(t)), ..., Jn(u(t))] ] subject to: [ \frac{dx(t)}{dt} = f(x(t), u(t), p), \quad x(t0) = x_0 ] [ g(x(t), u(t), p) \leq 0 ] [ h(x(t), u(t), p) = 0 ]

Where:

- ( J_i ) are the performance indices (objectives) to be optimized.

- ( u(t) ) is the vector of control variables (e.g., enzyme expression levels).

- ( x(t) ) is the vector of state variables (metabolite concentrations).

- ( p ) is the vector of fixed model parameters.

- ( g ) and ( h ) are inequality and equality path constraints, respectively.

Computational Procedure

Step 1: Control Vector Parameterization Discretize the continuous control variables (enzyme levels) into a finite set of parameters. This transforms the dynamic optimization problem into a nonlinear programming problem (NLP) [36].

Step 2: Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm (MOEA) Apply a state-of-the-art MOEA, such as NSGA-II or an improved SPEA2 variant, to solve the NLP [41]. The algorithm will evolve a population of potential solutions (enzyme modulation strategies) over many generations.

Step 3: Pareto Front Analysis The output of the MOEA is a set of non-dominated solutions—the Pareto front. Each point represents a unique trade-off between the objectives (e.g., high titer vs. low growth). Researchers can select the most suitable solution based on overarching project priorities [6] [36].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Diagram 1: Workflow for multi-objective optimization of a CHO cell model.

Key Reagent Solutions for Metabolic Engineering Experiments

The following table lists essential materials and computational tools used in the featured research for the model-based optimization of CHO cells [6] [36].

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in the Experiment / Field |

|---|---|

| CHO Cell Kinetic Model | A semi-mechanistic, dynamic model used to simulate metabolism and predict the outcome of genetic modifications in silico [6] [36]. |

| Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm (e.g., NSGA-II, SPEA2) | The computational core that performs the optimization, identifying the Pareto-optimal set of enzyme modulation strategies [36] [41]. |

| Dynamic Optimization Software | Software platform (e.g., custom tools from BioPreDyn project) used to formulate and solve the dynamic parameter estimation and optimization problems [36]. |

| Enzyme Expression Vectors | Plasmids or other delivery systems used to experimentally implement the up- or down-regulation of target enzymes identified by the optimization [36]. |

Visualizing the Optimization Core Concept

The fundamental outcome of a multi-objective optimization is the Pareto front. The relationship between the optimal solutions on the front and the sub-optimal solutions in the search space is a key concept for researchers to interpret results correctly.

Diagram 2: Relationship between search space and the Pareto-optimal front.

The pursuit of designing Escherichia coli strains for the homo-production of organic acids—where a single target acid is the primary fermentation product—is a central challenge in modern metabolic engineering. Achieving this goal requires a multi-objective optimization approach, where engineers must balance competing cellular objectives. An ideal strain must not only maximize product titer, yield, and productivity but also maintain a sufficiently high growth rate and minimize the secretion of undesired byproducts [3]. This case study examines the application of this framework for the production of acetate, lactate, and succinate, and provides a technical support resource to address common experimental hurdles.

Core Challenges in Homo-Organic Acid Production

Engineers face several interconnected challenges when designing robust production strains. The table below summarizes the primary obstacles and their underlying causes.

Table 1: Core Challenges in Developing Homo-Organic Acid Producing E. coli Strains

| Challenge | Description | Root Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Organic Acid Toxicity | Inhibition of cell growth and metabolism at low pH, reducing final product titers. | Undissociated acids diffuse freely across the cell membrane, dissociating in the neutral cytoplasm and acidifying the internal pH (pHi). This can denature enzymes and disrupt metabolism [43]. |

| Byproduct Formation | Production of a mixture of acids (e.g., formate, ethanol, lactate) instead of a single product. | Native E. coli mixed-acid fermentation pathways are designed to maintain redox balance (NAD+/NADH) under anaerobic conditions [44]. |