Mining the Genome: How Data Mining Unlocks Genetic Interactions in Complex Diseases

This article explores the critical role of data mining and machine learning in deciphering the complex genetic interactions underlying multifactorial diseases.

Mining the Genome: How Data Mining Unlocks Genetic Interactions in Complex Diseases

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of data mining and machine learning in deciphering the complex genetic interactions underlying multifactorial diseases. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive overview from foundational concepts to cutting-edge applications. We cover the fundamental principles of genetic interactions like synthetic lethality and their therapeutic potential, detail key machine learning methodologies from neural networks to random forests, address significant challenges in data integration and model validation, and compare the performance of computational predictions against high-throughput biological screens. The synthesis of these areas highlights how computational approaches are accelerating the discovery of novel drug targets and advancing the field of precision medicine.

The Blueprint of Complexity: Understanding Genetic Interactions and Their Role in Disease

In the genomics-driven landscape of complex disease research, understanding genetic interactions has moved from a theoretical concept to a practical imperative. Genetic interactions occur when the combined effect of two or more genetic alterations on a phenotype deviates from the expected additive effect. In oncology, these interactions, particularly the extreme negative form known as synthetic lethality (SL), have created transformative opportunities for targeted therapy. Synthetic lethality describes a relationship where simultaneous disruption of two genes results in cell death, while alteration of either gene alone is viable [1] [2]. This principle is clinically validated, most famously with PARP inhibitors selectively targeting tumors with BRCA1/2 deficiencies, showcasing how synthetic lethality can exploit cancer-specific vulnerabilities while sparing healthy tissues [2] [3]. The discovery of such interactions is now supercharged by advanced data mining of large-scale genomic datasets and high-throughput functional screens, enabling the systematic identification of therapeutic targets previously obscured by biological complexity.

Key Concepts and Definitions

The following table defines the core types of genetic interactions central to this field.

Table 1: Core Types of Genetic Interactions

| Interaction Type | Definition | Therapeutic Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Lethality (SL) | An extreme negative genetic interaction where co-inactivation of two non-essential genes causes cell death [1]. | Enables selective targeting of cancer cells with a pre-existing mutation in one gene partner [2] [3]. |

| Epistasis | A broader term for any deviation from independence in the effects of genetic alterations on a phenotype [2] [4]. | Helps map the fitness landscape of tumors, informing on disease aggressiveness and potential resistance mechanisms. |

| Conditional Epistasis | A triple gene interaction where the epistatic relationship between two genes depends on the mutational status of a third gene [2] [4]. | Identifies biomarkers for therapy success or failure, crucial for patient stratification. |

Computational Data Mining Methods

Computational methods are essential for pre-selecting candidate genetic interactions from the vast combinatorial space, thereby focusing experimental validation efforts.

Statistical and Survival-Based Approaches

The SurvLRT (Survival Likelihood Ratio Test) method identifies epistatic gene pairs and triplets from cancer patient genomic and survival data [2] [4]. It operates on the principle that a decrease in tumor cell fitness due to a specific genotype will be reflected in prolonged patient survival. For synthetic lethal pairs like BRCA1 and PARP1, survival of patients with tumors harboring co-inactivation of both genes is significantly longer than expected from the survival of patients with single mutations or wild-type genotypes [2]. SurvLRT formalizes this through a statistical model based on Lehmann alternatives, testing the null hypothesis (no epistasis, gene alterations are independent) against the alternative (presence of an interaction) [4]. A key strength of SurvLRT is its ability to detect triple epistasis, which can identify biomarkers. For instance, it successfully identified TP53BP1 deletion as a biomarker that alleviates the synthetic lethal effect between BRCA1 and PARP1, explaining why some BRCA1-mutated tumors do not respond to PARP inhibitor therapy [2] [4].

Benchmarking Scoring Algorithms for CRISPR Screen Data

With the rise of combinatorial CRISPR screening, various scoring methods have been developed to infer genetic interactions. A 2025 benchmarking study analyzed five such methods using five different combinatorial CRISPR datasets, evaluating them based on benchmarks of paralog synthetic lethality [1]. The study concluded that no single method performed best across all screens, but identified two generally well-performing algorithms. Of these, Gemini-Sensitive was noted as a reasonable first choice for researchers, as it performs well across most datasets and has an available, applicable R package [1].

Table 2: Computational Methods for Mining Genetic Interactions

| Method | Primary Data Input | Key Principle | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| SurvLRT [2] [4] | Patient genomic data (e.g., mutations) and clinical survival data. | Infers tumor fitness from patient survival to test for significant epistatic effects. | Significant epistatic gene pairs and triplets; biomarkers of therapy context. |

| Gemini-Sensitive [1] | Combinatorial CRISPR screen fitness data. | A statistical scoring algorithm to identify negative genetic interactions from perturbation screens. | A ranked list of candidate synthetic lethal gene pairs. |

| Coexpression & SoF [2] | Tumor genomic data (e.g., from TCGA) and gene expression data. | SoF (Survival of the Fittest): Identifies SL pairs via under-representation of co-inactivation. Coexpression: Assumes SL partners participate in related biological processes. | Candidate SL gene pairs based on mutual exclusivity or functional association. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Computational predictions require rigorous experimental validation. High-throughput combinatorial CRISPR screening has become the gold standard for this.

Protocol: Combinatorial CRISPR-Cas9 Screening for Synthetic Lethality

This protocol outlines the key steps for conducting a dual-guide CRISPR screen to identify synthetic lethal gene pairs, based on a large-scale 2025 pan-cancer study [3].

I. Library Design and Cloning

- Gene Pair Selection: Select candidate gene pairs from computational predictions (e.g., paralog pairs, regression models, integrated 'omics analyses). The library used in the cited study contained 472 gene pairs [3].

- Guide RNA (gRNA) Design: For each gene, design 6-8 gRNAs with high on-target efficiency and low off-target scores. This is critical when targeting paralogs with high sequence similarity [3].

- Vector Construction: Clone gRNA pairs into a dual-promoter lentiviral vector (e.g., utilizing hU6 and mU6 promoters). To mitigate positional bias, place half of the gRNAs for each gene behind each promoter. Include "safe-targeting" control gRNAs that target genomic regions with no known function to calculate single vs. double knockout effects accurately [3].

- Library QC: Sequence the final library to ensure correct representation and complexity.

II. Cell Line Screening

- Cell Culture: Transduce a panel of Cas9-expressing cancer cell lines (e.g., from melanoma, NSCLC, pancreatic cancer) with the lentiviral library at a low MOI (e.g., 0.3) to ensure most cells receive a single vector. Perform screens in technical triplicate with high library representation (e.g., 1000x) [3].

- Time Course: Maintain the cultures for a sufficient duration (e.g., 28 days) to allow depletion of gRNAs targeting synthetic lethal pairs due to cell death [3].

- Control Samples: Include short-term (e.g., 7-day) samples from Cas9 WT lines to establish the initial gRNA abundance for normalization [3].

III. Sequencing and Data Analysis

- DNA Extraction and Sequencing: Harvest cells at the endpoint, extract genomic DNA, amplify the gRNA regions by PCR, and perform high-throughput sequencing [3].

- Quality Control: Assess screen quality using metrics like Gini Index and replicate correlation. Exclude samples or replicates that fail QC thresholds (e.g., NNMD > -2) [3].

- Interaction Scoring: Process raw sequencing reads into a count matrix. Use specialized algorithms (e.g., Gemini-Sensitive) to score genetic interactions from the gRNA enrichment/depletion patterns [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Genetic Interaction Studies

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Combinatorial CRISPR Library [3] | High-throughput interrogation of gene pairs for synthetic lethality. | Requires dual-promoter system (hU6/mU6); includes target gRNAs, safe-targeting controls, essential/non-essential gene controls. |

| Dual-Guide Vector [3] | Lentiviral delivery of two gRNAs into a single cell. | Modified spacer and tracr sequences recommended to reduce plasmid recombination. |

| Cas9-Expressing Cell Lines [3] | Provide the nuclease machinery for CRISPR-mediated gene knockout. | Must be from relevant cancer lineages; should be genomically and transcriptomically characterized. |

| Safe-Targeting gRNA Controls [3] | Control for the effect of inducing a double-strand break without disrupting a gene. | Critical for accurately calculating the interaction effect between two gene knockouts. |

| Scoring Algorithm (R package) [1] | Computes genetic interaction scores from combinatorial screen data. | "Gemini-Sensitive" is a recommended, widely applicable method available in R. |

| Patient Genomic & Survival Data [2] [4] | Computational mining of epistasis from real-world clinical data. | Sources include TCGA; used by methods like SurvLRT which requires survival outcomes and mutation status. |

Signaling Pathways and Biological Mechanisms

The clinical success of PARP inhibitors in BRCA-deficient cancers exemplifies the translation of a synthetic lethal interaction into therapy. The underlying biological mechanism involves two complementary DNA repair pathways.

- Normal Cells: In a healthy cell, a single-strand break (SSB) is primarily repaired by the PARP-mediated pathway. If this repair fails and the SSB progresses to a more toxic double-strand break (DSB) during replication, the backup pathway—BRCA-mediated Homologous Recombination (HR)—can effectively repair the damage, ensuring cell survival [2].

- BRCA-Deficient Cancer Cells: In a tumor cell with a mutated BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene, the HR repair pathway is disrupted. The cell becomes reliant on PARP for SSB repair. Administering a PARP inhibitor knocks out this primary repair pathway. With both major repair pathways incapacitated, DNA damage accumulates, leading to genomic instability and selective cancer cell death [2].

- Context Dependence and Biomarkers: The efficacy of this therapy can be influenced by third-party genes, a phenomenon known as conditional epistasis. For example, a mutation in TP53BP1 can restore HR function in BRCA1-deficient cells, creating a resistance mechanism and serving as a negative biomarker for PARP inhibitor response [2] [4].

The integration of sophisticated data mining techniques with high-throughput experimental validation represents the forefront of identifying genetic interactions in complex diseases. Computational methods like SurvLRT for analyzing patient data and Gemini-Sensitive for scoring CRISPR screens provide powerful frameworks for generating candidate SL pairs and contextual biomarkers. These computational predictions are then efficiently tested through robust experimental protocols, such as combinatorial CRISPR screening. As these methodologies continue to mature and are applied to ever-larger datasets, they promise to rapidly expand the catalog of targetable genetic interactions, ultimately accelerating the development of precise, effective, and personalized therapeutic strategies for cancer and other complex diseases.

The intricate pathology of complex diseases like cancer is governed by multilayered biological information, encompassing genetic, epigenetic, transcriptomic, and histologic data [5]. Individually, each data type provides only a fragmentary view of the disease mechanism. The biomedical significance of this field stems from the critical need to integrate these disparate data modalities to obtain a systems-level understanding [5]. This holistic view is paramount for deciphering the dynamic genetic interactions and state-specific pathological mechanisms that drive disease progression and therapeutic resistance. Advances in data mining Methodologies are now making this integration possible, revealing previously hidden interactions. For instance, a recent analysis of 25,000 tumor samples revealed that 27.45% of cancer genes, including well-known drivers like ARID1A, FBXW7, and *SMARCA4, exhibit shifts in their interaction patterns between primary and metastatic cancer states [6]. This underscores the dynamic nature of tumor progression and establishes a compelling rationale for the development and application of sophisticated data integration frameworks in modern biomedical research.

Quantitative Evidence of Genetic Dynamics

Large-scale genomic studies are quantitatively mapping the complex landscape of genetic interactions in cancer, providing concrete evidence of their biomedical significance. The following table synthesizes key findings from recent research.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings on Genetic Interactions in Cancer

| Metric | Finding | Biomedical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Interaction Shifts | 27.45% of cancer genes show altered interaction patterns between primary and metastatic states [6]. | Cancer state is a critical determinant of gene function, necessitating state-specific research and therapeutic strategies. |

| State-Specific Interactions | Identification of 7 state-specific genetic interactions, 38 primary-specific high-order interactions, and 21 metastatic-specific high-order interactions [6]. | Primary and metastatic cancers operate through distinct biological mechanisms, which may represent unique therapeutic vulnerabilities. |

| Shift in Driver Status | Genes including ARID1A, FBXW7, and SMARCA4 shift between one-hit and two-hit driver patterns across states [6]. | The role of a gene in tumorigenesis is context-dependent, impacting risk models and targeted therapy approaches. |

An Integrated Experimental Protocol for Mapping Genetic Interactions

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for using the Deep Latent Variable Path Modelling (DLVPM) framework to map complex dependencies between multi-modal data types, such as multi-omics and histology, in cancer research [5].

Primary Workflow and Protocol

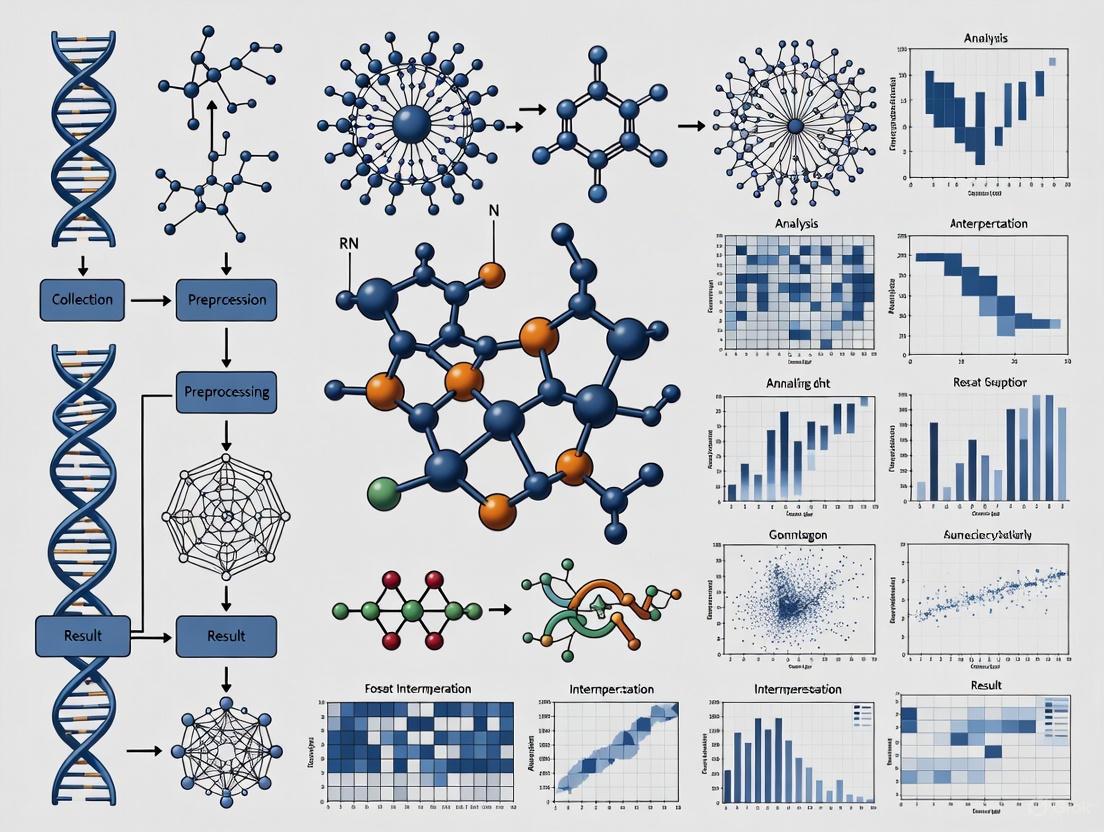

The schematic below outlines the core DLVPM process for integrating diverse data types to uncover latent relationships.

Pre-modeling and Data Preparation

- Step 1: Define the Path Model Hypothesis: The analysis begins by specifying an adjacency matrix, C, where elements c_ij ∈ {0,1} represent the presence or absence of a hypothesized direct influence from data type i to data type j [5]. This matrix is a formalization of the biological assumptions guiding the integration.

- Step 2: Data Collection and Curation: Gather multimodal datasets. A foundational example is the use of the Breast Cancer dataset from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), which includes single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), methylation profiles, microRNA sequencing, RNA sequencing, and histological whole-slide images [5]. Data must undergo standard pre-processing and quality control specific to each modality.

Model Training and Optimization

- Step 3: Initialize Measurement Models: For each of the K data types, define a specialized neural network (e.g., convolutional networks for images, feed-forward networks for omics data). This network, for data type i, is formulated as Ῡi (Xi, Ui, Wi), where Xi is the input data, Ui represents the parameters of the network's core, and W_i are the weights of the final linear projection layer [5].

- Step 4: Train the DLVPM Algorithm: The model is trained end-to-end to optimize the following objective function [5]:

- Objective: max Σ (c_ij * tr(Ῡi^T Ῡj)) for all i ≠ j. This maximizes the trace (a measure of association) between the DLVs of connected data types.

- Constraint: Ῡi^T Ῡi = I for all i. This ensures the DLVs for each data type are orthogonal, minimizing redundancy within the modality's embedding.

- Step 5: Model Validation: Benchmark the performance of DLVPM against classical path modelling methods, such as Partial Least Squares Path Modelling (PLS-PM), in its ability to identify known and novel associations between data types [5].

Post-modeling and Analysis

- Step 6: Downstream Analysis and Interpretation: Use the trained model for various downstream tasks. This includes:

- Stratification: Applying the model to single-cell or spatial transcriptomic data to identify novel cell states or histologic-transcriptional associations [5].

- Identification of Synthetic Lethal Interactions: Applying the molecular subcomponent of the model to CRISPR-Cas9 screen data from cell lines to identify genes with state-specific essentiality [5].

- Association Mapping: Analyzing the path model coefficients to identify specific genetic loci with significant associations to histological phenotypes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and computational tools are essential for implementing the protocols described above.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Genetic Interaction Data Mining

| Item/Tool Name | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| TCGA Datasets | A comprehensive, publicly available resource that provides correlated multi-omics and histology data from thousands of tumor samples, serving as a benchmark for model development and testing [5]. |

| DLVPM Framework | A computational method that combines deep learning with path modelling to integrate multimodal data and map their complex, non-linear dependencies in an explorative manner [5]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Screens | Used for functional validation, these screens identify gene dependencies and synthetic lethal interactions in different cancer states, which can be interpreted through the lens of the DLVPM model [5]. |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | A technology that maps gene expression within the context of tissue architecture, used to validate and provide mechanistic insights into histologic-transcriptional associations discovered by the model [5]. |

| Cloud Computing Platforms (e.g., Google Cloud Genomics, AWS) | Provide the scalable storage and computational power necessary to process and analyze the terabyte-scale data generated by NGS and multimodal integration studies [7]. |

Detailed Visualization of Multimodal Data Integration

The following diagram illustrates the specific flow of information and the modeling of interactions between different data types within the DLVPM framework.

The biomedical significance of researching genetic interactions in cancer and complex diseases lies in moving beyond a static, single-layer view of biology to a dynamic, integrated systems-level understanding. The ability to mine complex datasets has revealed that a significant proportion of cancer genes alter their interaction patterns based on disease state [6]. Methodologies like DLVPM, which leverage deep learning to integrate histology with multi-omics data, are pivotal for creating a unified model of disease pathology [5]. This holistic approach is not merely an academic exercise; it directly enables the identification of state-specific biological mechanisms and therapeutic vulnerabilities, thereby paving the way for precise therapeutic interventions tailored to the evolving landscape of a patient's disease.

The analysis of high-dimensional data represents a fundamental challenge in modern computational biology, particularly in the study of complex diseases. Traditional statistical methods, designed for datasets with many observations and few variables, often fail when confronted with the "large p, small n" paradigm common in genomics, where the number of features (p) such as genetic variants, gene expression levels, or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) vastly exceeds the number of observations (n) or study participants [7]. This dimensionality curse necessitates specialized analytical frameworks and visualization tools that can handle thousands to millions of variables while extracting biologically meaningful signals from substantial noise.

In complex diseases research, high-dimensionality arises from multiple technological fronts. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies like Illumina's NovaSeq X and Oxford Nanopore platforms generate terabytes of whole genome, exome, and transcriptome data, capturing genetic variation across large populations [7]. Multi-omics approaches further compound this dimensionality by integrating genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and epigenomic data layers to provide a comprehensive view of biological systems [7]. This data explosion has rendered traditional statistical methods insufficient, requiring innovative approaches that can address collinearity, overfitting, and computational complexity while maintaining statistical power and biological interpretability.

Methodological Framework for High-Dimensional Genetic Data

Advanced Visualization Strategies for High-Dimensional Data

Effective visualization of high-dimensional data requires moving beyond traditional two-dimensional scatterplots. GGobi is an open-source visualization program specifically designed for exploring high-dimensional data through highly dynamic and interactive graphics [8]. Its capabilities include:

- Data Tours: These allow researchers to "tour" through high-dimensional spaces using projection methods like principal components analysis (PCA) and grand tours, effectively enabling them to see separation between clusters in high dimensions [8].

- Multiple Linked Views: GGobi supports scatterplots, barcharts, parallel coordinates plots, and scatterplot matrices that are interactive and linked through brushing and identification techniques [8] [9]. When a researcher selects points in one visualization, corresponding points are highlighted across all other open visualizations.

- Extensible Framework: GGobi can be embedded in R through the

rggobipackage, creating a powerful synergy between GGobi's direct manipulation graphical environment and R's robust statistical analysis capabilities [8] [9]. This integration allows researchers to fluidly examine the results of R analyses in an interactive visual environment.

The system uses parallel coordinates plots, which represent multidimensional data by using multiple parallel axes rather than the perpendicular axes of traditional Cartesian plots [9]. This visualization technique enables researchers to identify patterns, clusters, and outliers across many variables simultaneously, making it particularly valuable for exploring genetic datasets with hundreds of dimensions.

Statistical Protocols for High-Dimensional Genetic Analysis

Protocol 1: Estimating Heritability of Drug Response with GxEMM

Purpose: To quantify the proportion of variability in drug response attributable to genetic factors using Gene-Environment Interaction Mixed Models (GxEMM) [10].

Materials and Reagents:

- Genotypic data (SNP array or whole-genome sequencing data)

- Phenotypic drug response measurements

- Covariate data (age, sex, principal components for ancestry)

- High-performance computing infrastructure

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Quality control of genetic data including SNP filtering based on call rate, minor allele frequency, and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

- Genetic Relationship Matrix (GRM) Construction: Calculate the genetic similarity between all pairs of individuals based on genome-wide SNPs.

- Model Fitting: Implement GxEMM to partition phenotypic variance into genetic, environmental, and gene-environment interaction components.

- Heritability Estimation: Calculate the proportion of phenotypic variance explained by genetic factors (h² = Vg/Vp).

Interpretation: High heritability estimates suggest strong genetic determinants of drug response, warranting further investigation into specific genetic variants.

Protocol 2: Identifying Gene-Drug Interactions with TxEWAS

Purpose: To identify transcriptome-wide associations between gene expression and drug response phenotypes using Transcriptome-Environment Wide Association Study (TxEWAS) framework [10].

Materials and Reagents:

- RNA-seq or microarray gene expression data

- Drug response metrics (IC50, AUC, therapeutic efficacy)

- Clinical covariate data

- Cloud computing platform (AWS, Google Cloud Genomics)

Methodology:

- Expression Quantification: Process RNA-seq data to obtain normalized gene expression counts (TPM or FPKM).

- Quality Control: Remove batch effects and normalize expression data across samples.

- Association Testing: Perform transcriptome-wide association between each gene's expression and drug response metrics, adjusting for relevant covariates.

- Multiple Testing Correction: Apply false discovery rate (FDR) control to account for thousands of simultaneous tests.

- Validation: Confirm identified associations in independent cohorts or through functional experiments.

Interpretation: Significant associations indicate genes whose expression levels modify drug response, potentially serving as biomarkers for treatment stratification.

Table 1: Key Analytical Tools for High-Dimensional Genetic Data

| Tool/Platform | Primary Function | Data Type | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| GGobi [8] | Interactive visualization | High-dimensional multivariate data | Multiple linked views, dynamic projections, R integration |

| GxEMM [10] | Heritability estimation | Genetic and phenotypic data | Models gene-environment interactions, accounts for population structure |

| TxEWAS [10] | Gene-drug interaction identification | Transcriptomic and drug response data | Genome-wide coverage, adjusts for covariates |

| DeepVariant [7] | Variant calling | NGS data | Deep learning-based, higher accuracy than traditional methods |

| Cloud Genomics Platforms [7] | Data storage and analysis | Multi-omics data | Scalability, collaboration features, cost-effectiveness |

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Approaches

AI and machine learning have become indispensable for high-dimensional genomic analysis [7]. These approaches include:

- Deep Learning for Variant Calling: Tools like Google's DeepVariant utilize convolutional neural networks to identify genetic variants from NGS data with greater accuracy than traditional methods [7].

- Polygenic Risk Scores: Machine learning models integrate effects of thousands of genetic variants to predict individual susceptibility to complex diseases [7].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Autoencoders and other neural network architectures compress high-dimensional genetic data into lower-dimensional representations while preserving biologically relevant patterns.

Application to Complex Diseases and Drug Development

Case Study: Pharmacogenomics in Clinical Trials

Incorporating genetic analysis into clinical drug development presents both opportunities and challenges. Key considerations include:

- Prospective Planning: Designing clinical trials with prospective genetic testing and consent built into the protocol enables genetic analysis of both efficacy and adverse events [11].

- Ethnic Variability: Accounting for ethnic variability in genetic variant prevalence is crucial for appropriate recruitment and enrollment strategies [11].

- Return of Results: Developing frameworks for returning genetic results to participants in a timely and usable format promotes patient engagement and data utility beyond the immediate trial [11].

A compelling example comes from the Tailored Antiplatelet Therapy Following Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (TAILOR-PCI) study, which evaluated how genetic variants affect responses to clopidogrel and clinical outcomes [11]. This study exemplifies the movement toward genetics-enabled drug development that shifts from traditional one-phase, one-drug trials toward "evidence generation engines" using master protocols, standardized consent processes, and linked clinical trial platforms [11].

Case Study: Prader-Willi Syndrome Research

Research on Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS) illustrates the challenges of conducting clinical trials in rare genetic disorders with limited patient populations [11]. Key issues include:

- Patient Stratification: Understanding how phenotypic variability across genetic subtypes affects treatment response is essential for trial interpretation [11].

- DNA Collection: Incorporating DNA collection into clinical trials enables assessment of genetic factors related to drug safety, as demonstrated by a Phase 3 PWS trial where genetic information could have informed the evaluation of fatal pulmonary embolism [11].

- Multi-Omics Integration: The Foundation for Prader-Willi Research's pilot PWS Genomes Project combines whole-genome sequencing with registry data to inform clinical management, drug selection, and trial stratification [11].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Genetic Interactions Research

| Research Reagent | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq X [7] | High-throughput sequencing | Large-scale whole genome sequencing, population studies |

| Oxford Nanopore [7] | Long-read sequencing | Structural variant detection, real-time sequencing |

| CRISPR Screening Tools [7] | Functional genomics | High-throughput gene perturbation, target identification |

| Multi-Omics Integration Platforms | Data integration | Combines genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic data |

| Cloud Computing Infrastructure [7] | Data storage and analysis | HIPAA/GDPR compliant, scalable processing |

Visualization Protocols and Workflows

High-Dimensional Data Visualization Workflow

High-Dimensional Data Visualization Workflow

Gene-Drug Interaction Analysis Pipeline

Gene-Drug Interaction Analysis Pipeline

The challenge of high-dimensionality in genetics research necessitates a fundamental shift from traditional statistical methods to integrated analytical frameworks. Through specialized visualization tools like GGobi, advanced statistical methods including GxEMM and TxEWAS, and AI-powered analytical platforms, researchers can now navigate the complexity of multi-omics data to uncover genetic interactions in complex diseases. These approaches are transforming drug development by enabling more precise patient stratification, target identification, and safety prediction. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they will increasingly power precision medicine approaches that account for the complex genetic architecture underlying disease susceptibility and treatment response.

Understanding the genetic architecture of complex diseases requires the integration of large-scale, heterogeneous biological data. The convergence of high-throughput genomic technologies, extensive biobanking initiatives, and sophisticated computational tools has created unprecedented opportunities for deciphering gene-gene and gene-environment interactions underlying disease pathogenesis. These data resources provide the foundational elements for applying data mining approaches to uncover complex genetic interactions that escape conventional single-variant analyses. This application note outlines the primary data sources and analytical protocols essential for investigating epistatic networks in complex disease traits, providing researchers with practical frameworks for leveraging these resources in their studies of genetic interactions.

Table 1: Major National Biobank Initiatives with Whole-Genome Sequencing Data

| Biobank Name | Participant Count | Key Population Characteristics | Primary Data Types | Unique Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK Biobank | ~500,000 participants [12] | 54% female, 46% male; predominantly European ancestry [12] | WGS for 490,640 participants; health records; lifestyle data [12] | One of the most comprehensive population-based health resources [12] |

| All of Us Research Program | 245,388 WGS participants (target >1M) [12] | 77% from groups underrepresented in research [12] | WGS; EHR; physical measurements; wearable data [12] | Focus on diversity and inclusive precision medicine [12] |

| Biobank Japan | ~200,000 participants [12] | Balanced gender distribution (53.1% male, 46.9% female) [12] | WGS for 14,000; SNP arrays; metabolomic & proteomic data [12] | Disease-focused on 51 common diseases in Japanese population [12] |

| PRECISE Singapore | Target 100,000+ participants [12] | Chinese (58.4%), Indian (21.8%), Malay (19.5%) [12] | WGS; multi-omics including transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics [12] | Integrated advanced imaging and diverse Asian representation [12] |

Genomic Databases and Repositories

Genomic databases serve as critical infrastructure for storing, curating, and distributing data on genetic variations, gene expression, protein interactions, and functional genomic elements. These repositories vary in scope from comprehensive reference databases to specialized resources focusing on specific data types or disease areas, each offering unique value for genetic interaction studies.

The BioGRID database represents a premier resource for protein-protein and genetic interaction data, with curated information from 87,393 publications encompassing over 2.2 million non-redundant interactions [13]. Particularly relevant for complex disease research is the BioGRID Open Repository of CRISPR Screens (ORCS), which contains curated data from 2,217 genome-wide CRISPR screens from 418 publications, encompassing 94,219 genes across 825 different cell lines and 145 cell types [13]. This resource provides systematic functional genomic data essential for validating genetic interactions suggested by computational mining approaches.

For gene expression data, repositories such as the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and ArrayExpress archive functional genomic datasets, while the Systems Genetics Resource (SGR) offers integrated data from both human and mouse studies specifically designed for complex trait analysis [14]. The SGR web application provides pre-computed tables of genetic loci controlling intermediate and clinical phenotypes, along with phenotype correlations, enabling researchers to investigate relationships between DNA variation, intermediate phenotypes, and clinical traits [14].

Table 2: Specialized Genomic Databases for Interaction Studies

| Database Name | Primary Focus | Data Content | Applications in Complex Disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| BioGRID ORCS [13] | CRISPR screening data | 2,217 curated CRISPR screens; 94,219 genes; 825 cell lines [13] | Functional validation of genetic interactions; identification of gene essentiality networks |

| Systems Genetics Resource [14] | Complex trait genetics | Genotypes, clinical and intermediate phenotypes from human and mouse studies [14] | Mapping relationships between genetic variation, molecular traits, and clinical outcomes |

| PLOS Recommended Repositories [15] | General genomic data | Diverse data types through specialized repositories (GEO, GenBank, dbSNP) [15] | Access to standardized, community-endorsed data for integrative analyses |

National biobanks have emerged as transformative resources for complex disease genetics, combining large-scale participant cohorts with whole-genome sequencing and rich phenotypic data. These initiatives enable researchers to investigate gene-gene and gene-environment interactions across diverse populations with sufficient statistical power to detect modest genetic effects characteristic of complex traits.

The UK Biobank exemplifies this approach with approximately 500,000 participants aged 40-69 years, providing WGS data for 490,640 individuals that encompasses over 1.1 billion single-nucleotide polymorphisms and approximately 1.1 billion insertions and deletions [12]. This resource integrates genomic data with extensive phenotypic information collected through surveys, physical and cognitive assessments, and electronic health record linkage, creating a comprehensive platform for investigating complex disease etiology.

The All of Us Research Program addresses historical biases in genomic research by specifically recruiting participants from groups historically underrepresented in biomedical research, with 77% of its 245,388 WGS participants belonging to these populations [12]. This diversity is crucial for ensuring that genetic risk predictions and therapeutic insights benefit all population groups equitably. Similarly, Singapore's PRECISE initiative captures genetic diversity across major Asian ethnic groups (Chinese, Indian, and Malay), enabling population-specific investigations of genetic interactions in complex diseases [12].

Diagram 1: Biobank data workflow for genetic interaction studies. WGS = Whole Genome Sequencing; QC = Quality Control.

High-Throughput Functional Genomic Screens

High-throughput functional genomic screens provide systematic approaches for interrogating gene function and genetic interactions at scale. CRISPR-based screens, in particular, have revolutionized our ability to identify genetic dependencies, synthetic lethal interactions, and context-specific gene essentiality relevant to complex disease mechanisms.

The BioGRID ORCS database exemplifies the scale and sophistication of modern functional screening resources, encompassing curated data from 418 publications with detailed metadata annotation capturing experimental parameters such as cell line, genetic background, screening conditions, and phenotypic readouts [13]. These datasets enable researchers to identify genetic interactions through synthetic lethality analyses, pathway-based functional modules, and context-specific genetic dependencies.

Protocol 1 outlines a standard workflow for analyzing CRISPR screen data to identify genetic interactions:

Protocol 1: Analysis of CRISPR Screening Data for Genetic Interactions

Objective: Identify synthetic lethal genetic interactions from genome-wide CRISPR screening data.

Input Data: Raw read counts from CRISPR guide RNA sequencing; sample metadata; reference genome annotation.

Step 1 - Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

- Trim adapter sequences from raw sequencing reads using Cutadapt [13]

- Align reads to the reference genome using BWA or Bowtie2

- Quantify guide RNA abundance from aligned reads

- Perform quality control: assess library complexity, read distribution, and sample correlation

- Remove guides with low counts across samples (minimum threshold: 10 reads per guide)

Step 2 - Normalization and Batch Effect Correction

- Normalize read counts using DESeq2's median of ratios method or similar approach

- Correct for batch effects using ComBat or remove unwanted variation (RUV) methods

- Regress out technical covariates (sequencing depth, batch, etc.)

Step 3 - Gene-Level Analysis

- Aggregate guide-level counts to gene-level scores using the MAGeCK or drugZ algorithms

- Calculate gene essentiality scores comparing control vs. experimental conditions

- Identify significantly depleted or enriched genes (FDR < 0.1)

Step 4 - Genetic Interaction Identification

- Compute differential genetic interaction scores using statistical frameworks like hitman

- Identify synthetic lethal pairs showing stronger combined effects than expected

- Validate interactions using orthogonal datasets (e.g., protein-protein interactions)

Step 5 - Functional Interpretation

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis on interacting gene sets

- Map genetic interactions to protein complexes and biological pathways

- Integrate with clinical genomic data to assess disease relevance

Output: Ranked list of genetic interactions; functional annotation of interacting gene sets; pathway context of genetic interactions.

Data Integration Methodologies

Integrating diverse genomic data types is essential for comprehensive understanding of complex genetic interactions. Multi-omics approaches combine genomics with transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics to provide a systems-level view of biological processes underlying disease pathogenesis [7] [16].

A critical development in genomic data integration is the conceptual framework that classifies integration approaches based on the biological question, data types, and stage of integration [17]. This framework distinguishes between integrating similar data types (e.g., multiple gene expression datasets) versus heterogeneous data types (e.g., genomic, clinical, and environmental data), each requiring specialized methodologies [17].

Protocol 2 provides a structured approach for multi-omics data integration focused on identifying master regulatory networks in complex diseases:

Protocol 2: Multi-Omics Data Integration for Complex Disease Traits

Objective: Integrate genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic data to identify master regulators of disease phenotypes.

Input Data: Gene expression matrix (e.g., RNA-seq); genetic variant data (e.g., SNP arrays); DNA methylation data; clinical phenotype data.

Step 1 - Data Matrix Design

- Structure data with genes as biological units in rows and omics variables in columns [18]

- Align features across datasets using official gene symbols or genomic coordinates

- Create a multi-block data structure with matched samples across omics layers

Step 2 - Formulate Specific Biological Questions

- Define analysis goal: description (major interplay), selection (biomarkers), or prediction (outcomes) [18]

- Example question: "How do genetic variants and DNA methylation interact to affect gene expression in disease tissue?"

Step 3 - Tool Selection

- Choose integration method appropriate for data types and biological question

- Recommended tools: mixOmics for multi-block integration [18]

- Consider dimensionality reduction methods (PCA, PLS) for high-dimensional data [18]

Step 4 - Data Preprocessing

- Handle missing values using k-nearest neighbors imputation or deletion

- Normalize data within each omics type (e.g., variance stabilizing transformation for RNA-seq)

- Remove batch effects using ComBat or surrogate variable analysis

- Transform data to approximate normal distributions where appropriate

Step 5 - Preliminary Single-Omics Analysis

- Perform quality control and exploratory analysis on each dataset separately

- Identify major sources of variation within each data type

- Assess data structure and identify potential confounders

Step 6 - Multi-Omics Integration Execution

- Apply DIABLO or similar multi-block integration method from mixOmics package [18]

- Identify correlated variables across omics datasets

- Extract multi-omics signatures explaining maximum covariance with phenotype

- Validate stability of selected features using cross-validation

Step 7 - Biological Interpretation

- Annotate selected features with functional information

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis on multi-omics modules

- Construct network models of regulatory relationships

- Generate hypotheses for experimental validation

Output: Integrated multi-omics signatures; network models of genetic interactions; candidate master regulators; functional annotation of disease-relevant pathways.

Diagram 2: Multi-omics data integration approaches. Early = data combined before analysis; Intermediate = features combined before modeling; Late = results combined after separate analyses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Genetic Interaction Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application in Genetic Studies |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Screening Libraries (e.g., Brunello, GeCKO) | Genome-wide gene knockout | Systematic identification of genetic dependencies and synthetic lethal interactions [13] |

| Illumina NovaSeq X Series | High-throughput sequencing | Whole-genome sequencing for large biobank cohorts [7] |

| Oxford Nanopore Technologies | Long-read sequencing | Detection of structural variants and haplotype phasing [7] |

| mixOmics R Package | Multi-omics data integration | Statistical framework for identifying correlated features across omics datasets [18] |

| BioGRID ORCS Database | CRISPR screen repository | Access to curated genome-wide screening data from published studies [13] |

| Cloud Computing Platforms (AWS, Google Cloud) | Scalable data analysis | Computational infrastructure for large-scale genomic data mining [7] |

Quality Control and Data Standards

Maintaining data quality throughout the integration pipeline is paramount for generating reliable insights into genetic interactions. Data quality dimensions including currency, representational consistency, specificity, and reliability must be systematically addressed when combining heterogeneous genomic data sources [19]. Quality-aware genomic data integration requires careful attention to metadata standards, controlled vocabularies, and interoperability frameworks to ensure that integrated datasets support valid biological conclusions.

For genomic data deposition, community-endorsed repositories should be selected based on criteria including stable persistent identifiers, open access policies, long-term preservation plans, and community adoption [15]. Recommended repositories for different data types include GEO and ArrayExpress for functional genomics data; GenBank, EMBL, and DDBJ for sequences; and dbSNP for genetic variants [15]. Adherence to these standards ensures that data mining efforts for genetic interactions can build upon reproducible, well-annotated foundational datasets.

The integration of genomic databases, biobanks, and high-throughput functional screens creates powerful synergies for deciphering genetic interactions in complex diseases. By leveraging the protocols and resources outlined in this application note, researchers can design systematic approaches to identify and validate epistatic networks contributing to disease pathogenesis. As these data resources continue to expand in scale and diversity, they will increasingly support the development of more comprehensive models of disease etiology and create new opportunities for therapeutic intervention targeting genetic interaction networks.

The AI Toolbox: Machine Learning Methods for Detecting Gene-Gene Interactions

Understanding the genetic underpinnings of complex diseases represents one of the most significant challenges in modern genomics. Unlike single-gene disorders, conditions like diabetes, cancer, and inflammatory bowel disease are influenced by complex networks of multiple genes working together through non-linear interactions [20]. The sheer number of possible gene combinations creates a computational challenge that conventional statistical approaches struggle to address. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS), which attempt to find individual genes linked to a trait, often lack the statistical power to detect the collective effects of groups of genes [20].

Machine learning algorithms, particularly neural networks, support vector machines (SVM), and random forests, have emerged as powerful tools for analyzing high-dimensional genomic data. These methods can model complex, non-additive relationships between genetic variants and phenotypic outcomes, moving beyond the limitations of traditional linear models [21]. Neural networks can approximate any function and scale effectively with large datasets [22]. Random forests naturally capture interactive effects of high-dimensional risk variants without imposing specific model structures [21]. Though less frequently highlighted for interaction detection, SVMs provide robust performance in high-dimensional settings where the number of features exceeds the number of samples [23].

This article provides application notes and protocols for implementing these core algorithms in genetic interaction research, with a focus on detecting epistasis and modeling polygenic risk in complex diseases.

Algorithm Comparison and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Core Algorithm Characteristics for Genetic Analysis

| Algorithm | Key Strengths | Interaction Detection Capability | Interpretability | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Networks | Models complex non-linear relationships; scales with data size; flexible architectures [22] | Explicitly models interactions through hidden layers and non-linear activations [22] | Lower intrinsic interpretability; requires post-hoc methods like NID, PathExplain [22] | Genome-wide risk prediction; large-scale epistasis detection; deep feature interaction maps [22] |

| Random Forests | Model-free approach; handles categorical data naturally; provides feature importance; efficient parallelization [21] | Naturally captures interactive effects through decision tree splits [21] | High interpretability through variable importance measures and individual tree inspection [21] | Genetic risk score construction; variant prioritization; traits with epistatic architectures [21] |

| Support Vector Machines | Effective in high-dimensional spaces; robust to overfitting; versatile kernels [23] | Limited intrinsic capability; dependent on kernel choice | Moderate; support vectors provide some insight but kernel transformations can obscure relationships [23] | Smaller-scale genomic prediction; binary classification tasks; scenarios with clear margins of separation |

Table 2: Reported Performance Metrics Across Genomic Studies

| Algorithm | Application | Reported Performance | Comparison to Traditional Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible Neural Networks (GenNet) | Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) case-control study [22] | Identified seven significant epistasis pairs with high consistency between interpretation methods [22] | Superior to exhaustive epistasis detection methods; more computationally efficient for genome-wide data |

| Random Forest (ctRF) | Alzheimer's disease, BMI, atopy [21] | Consistently outperformed classical additive models for traits with complex genetic architectures [21] | Enhanced prediction accuracy compared to C+T, lassosum, and LDPred for non-additive traits |

| SVM | Wheat rust resistance prediction [23] | Avoided limitations imposed by statistical structure of features [23] | Performance constrained by complexity and scale of data compared to deep learning approaches |

| ResDeepGS (CNN) | Crop phenotype prediction [23] | 5%-9% accuracy improvement on wheat data compared to existing methods [23] | Outperformed GBLUP, RF, and other deep learning models across multiple crop datasets |

Neural Networks for Genetic Interaction Detection

Protocol: Visible Neural Networks with Biological Prior Knowledge

Application Note: Visible neural networks (VNNs) embed biological knowledge directly into the network architecture, creating sparse, interpretable models that respect biological hierarchy. The GenNet framework structures networks where SNPs are grouped into genes, and genes into pathways, allowing the model to learn importance at multiple biological levels [22].

Experimental Workflow:

Input Preparation

- Encode SNP data using either additive (0,1,2) or one-hot encoding.

- Perform quality control: remove rare variants (MAF <5%), exclude variants violating Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p<0.001).

- Adjust for population stratification using principal components.

Network Architecture Definition

- Define layer 1 (SNP to gene): Connect each SNP to its corresponding gene node based on genomic annotations.

- Define layer 2 (Gene to pathway): Connect gene nodes to their biological pathways using databases like KEGG or Reactome.

- Add multiple filters per gene to capture different patterns (Supplementary Fig. 1) [22].

- Use convergence layers to merge multiple filters back to single nodes.

Model Training

- Implement using the GenNet framework (https://github.com/arnovanhil/GenNet) [22].

- Use binary cross-entropy loss for case-control studies.

- Optimize with Adam optimizer with default parameters.

- Employ early stopping based on validation AUC.

Interaction Detection

- Apply post-hoc interpretation methods to trained networks:

Diagram 1: Visible Neural Network Architecture

Case Study: Detecting Epistasis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Background: Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has a known but incompletely characterized genetic component involving gene-gene interactions [22].

Dataset: International IBD Genetics Consortium (IIBDGC) dataset:

- 130,071 SNPs after quality control

- 66,280 samples (32,622 cases, 33,658 controls)

- Feature:sample ratio ≈ 2:1 [22]

Implementation:

- Trained GenNet VNN with SNP→gene→pathway architecture

- Gene annotations from Ensembl

- Pathway annotations from Reactome

- Applied NID and DFIM to trained network

Results: Identified seven significant epistasis pairs through follow-up association testing on candidates from interpretation methods [22].

Random Forests for Non-Linear Genetic Effects

Protocol: Random Forest-based Genetic Risk Scores

Application Note: Random forests construct GRS by treating SNP genotypes as categorical variables without assuming a specific genetic model, naturally capturing epistatic interactions. The ensemble of decision trees provides robust risk prediction for complex traits with non-additive genetic architectures [21].

Experimental Workflow:

Data Preparation

- Code SNP genotypes as 0,1,2 (additive) or maintain as categorical.

- Include principal components as covariates to adjust for population stratification.

- Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets.

Model Training with Enhanced RF Methods

- ctRF (clumping and thresholding RF): Perform LD clumping to remove correlated SNPs (-r² threshold 0.1) within 250kb windows, retaining most significant SNPs. Apply p-value thresholding (5e-8 to 0.1) to select optimal SNP subset [21].

- wRF (weighted RF): Adjust SNP sampling probability in tree nodes based on GWAS association strength from base data.

Parameter Tuning

- Optimize mtry (number of features considered per split): typical range √p to p/3, where p is number of SNPs.

- Set ntree (number of trees) to 500-1000 for stabilization.

- Use validation set to tune hyperparameters.

GRS Calculation and Interpretation

- Compute GRS as predicted disease probability using the method of Malley et al. (2012) implemented in the R package "ranger" [21].

- Calculate variable importance measures (permutation importance or Gini importance).

- Extract interaction patterns through tree inspection.

Diagram 2: Random Forest GRS Workflow

Case Study: Predicting Complex Traits with ctRF

Background: Traditional GRS methods assume additive genetic effects, potentially missing non-linear interactions in traits like Alzheimer's disease and BMI [21].

Dataset:

- Alzheimer's Disease Sequencing Project (ADSP)

- Taiwan Biobank (BMI)

- LIGHTS cohort (atopy)

Implementation:

- Applied ctRF with LD clumping and p-value thresholding

- Incorporated base data from large-scale GWAS summary statistics

- Compared performance against C+T, lassosum, and LDPred

Results: ctRF consistently outperformed classical additive models when traits exhibited complex genetic architectures, demonstrating the importance of capturing non-linear genetic effects [21].

Support Vector Machines in Genomic Selection

Protocol: SVM for Genomic Prediction

Application Note: SVMs handle high-dimensional genomic data by finding optimal hyperplanes that maximize separation between classes in a transformed feature space. While less naturally suited for interaction detection than other methods, their robustness in high-dimensional spaces makes them valuable for genomic prediction tasks [23].

Experimental Workflow:

Data Preprocessing

- Standardize genotype data (mean=0, variance=1).

- Address class imbalance through weighting or sampling.

- Perform feature selection to reduce dimensionality if needed.

Model Training

- Select appropriate kernel:

- Linear kernel for interpretability and high-dimensional data

- RBF kernel for capturing complex non-linear relationships

- Optimize regularization parameter C through cross-validation

- For RBF kernel, optimize gamma parameter

- Select appropriate kernel:

Model Evaluation

- Use nested cross-validation to avoid overfitting

- Evaluate using AUC-ROC for classification, R² for continuous traits

- Compare against baseline models (GBLUP, RR-BLUP)

Implementation Considerations: SVMs struggle with large sample sizes due to computational complexity O(n³) and provide limited insight into genetic interactions compared to random forests and neural networks [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| GenNet | Software Framework | Implements visible neural networks for genetics with biological prior knowledge [22] | https://github.com/arnovanhil/GenNet |

| GAMETES | Simulation Tool | Generates pure and strict epistatic models without marginal effects for benchmarking [22] | Open-source package |

| EpiGEN | Simulation Tool | Simulates complex phenotypes based on realistic genotype data with LD structure [22] | Available from original publication |

| DRscDB | Database | Centralizes scRNA-seq datasets for querying expression patterns [24] | https://www.flyrnai.org/tools/single_cell |

| ranger | R Package | Efficient implementation of random forests for high-dimensional data [21] | CRAN |

| DIOPT | Ortholog Tool | Identifies orthologs and paralogs across species [24] | https://www.flyrnai.org/DIOPT |

| FlyPhoneDB | Analysis Tool | Predicts cell-cell communication from scRNA-seq data [24] | https://www.flyrnai.org/tools/fly_phone |

| TWAVE | AI Model | Identifies gene combinations underlying complex diseases using generative AI [20] | From corresponding author |

The complex nature of genetic interactions in disease requires a multifaceted algorithmic approach. Visible neural networks provide the most sophisticated framework for modeling complex non-linear relationships in genome-wide data, while random forests offer an interpretable, robust method for capturing epistasis in genetic risk prediction. Support vector machines remain valuable for specific applications with clear separation margins. By leveraging the strengths of each algorithm through ensemble methods or sequential analysis, researchers can more effectively unravel the complex genetic architectures underlying human disease.

Future directions should focus on developing more interpretable AI approaches, integrating multi-omics data, and implementing federated learning to address data privacy concerns while advancing precision medicine.

In the context of data mining for genetic interactions in complex diseases, understanding the distinction between supervised and unsupervised machine learning is paramount. These methodologies offer complementary approaches for deciphering the complex genotype-phenotype relationships that underlie conditions like cancer, diabetes, and autoimmune disorders [25] [26]. Supervised learning relies on labeled datasets to train models for predicting outcomes or classifying data based on known genetic interactions [27]. In contrast, unsupervised learning discovers hidden patterns and intrinsic structures from unlabeled genetic data without prior knowledge or training, making it invaluable for exploratory analysis in complex disease research [26] [28]. The choice between these paradigms depends critically on the research objectives, data availability, and the current state of knowledge about the genetic architecture of the disease under investigation [25].

Performance Comparison and Selection Guidelines

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, strengths, and weaknesses of supervised and unsupervised learning approaches in the context of genetic data analysis for complex diseases.

Table 1: Comparison of Supervised and Unsupervised Learning for Genetic Data

| Feature | Supervised Learning | Unsupervised Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Core Objective | Prediction and classification of known outcomes [27] | Discovery of hidden patterns and data structures [28] |

| Data Requirements | Labeled training data (e.g., known disease associations) [27] | Raw, unlabeled data (e.g., genotype data without phenotypes) [26] |

| Common Algorithms | Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests, Linear Regression [29] [27] | K-means, Hierarchical Clustering, Principal Component Analysis [26] [28] |

| Primary Applications in Genetics | Disease risk prediction, classifying disease subtypes, drug response prediction [29] | Patient stratification, genetic subgroup discovery, anomaly detection in sequences [26] [28] |

| Key Advantages | High predictive accuracy, interpretable models, well-suited for clinical translation [27] | No need for labeled data, potential to discover novel biological insights [26] |

| Major Challenges | Dependency on large, high-quality labeled datasets [27] | Results can be harder to interpret and validate biologically [26] |

Evaluation studies on gene regulatory network inference have demonstrated that supervised methods generally achieve higher prediction accuracies when comprehensive training data is available [30]. However, in scenarios where labeled data is scarce or the goal is novel discovery, unsupervised techniques like clustering provide a powerful alternative, capable of identifying genetically distinct patient subgroups without prior class labels [26].

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Protocol 1: Supervised Classification for Disease Risk Prediction

This protocol outlines the use of a Random Forest classifier to predict individual disease risk from genome-wide association study (GWAS) data.

Step 1: Data Preparation and Feature Selection

- Obtain genotype data (e.g., SNP arrays) and corresponding phenotype labels (e.g., case/control status) [25].

- Perform quality control: filter SNPs based on call rate, minor allele frequency, and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

- Use filter methods (e.g., Fisher's exact test) or embedded feature selection from Random Forests to identify a panel of genetic variants most predictive of the disease state [25] [29].

Step 2: Model Training and Validation

- Split the dataset into training (e.g., 70%) and testing (e.g., 30%) subsets.

- Train the Random Forest model on the training set. The algorithm will construct multiple decision trees, each using a random subset of the data and features, to minimize overfitting [29].

- Tune hyperparameters (e.g., number of trees, tree depth) via cross-validation.

- Validate the model's performance on the held-out test set using metrics such as Area Under the Curve (AUC), accuracy, and precision [30].

Step 3: Interpretation and Downstream Analysis

- Extract feature importance scores from the trained Random Forest model to identify genetic variants with the greatest predictive power [29].

- Integrate top-ranking variants with functional genomic data (e.g., protein-protein interaction networks) to glean biological insights into disease mechanisms [25].

Protocol 2: Unsupervised Clustering for Patient Stratification

This protocol describes an unsupervised clustering approach to identify distinct genetic subgroups within a patient cohort, which may correspond to different disease etiologies or treatment responses.

Step 1: Data Preprocessing and Linkage Disequilibrium Pruning

Step 2: Clustering and Cluster Number Determination

Step 3: Statistical Validation and Biological Interpretation

- Conduct statistical tests (accounting for family-wise error rate) to identify the specific genetic variants that are significantly different between the derived clusters [26].

- Perform gene pathway enrichment analysis (e.g., Gene Ontology) on the genes containing significant variants to understand the potential biological processes distinguishing the patient subgroups [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for Machine Learning with Genetic Data

| Item/Tool | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Arrays | High-throughput technology to genotype hundreds of thousands of genetic variants (SNPs) across the genome [26]. | Generating the primary genetic dataset for both supervised and unsupervised analyses. |

| Bioinformatics Suites (PLINK, GCTA) | Software tools for performing quality control, population stratification, and basic association testing on genetic data. | Preprocessing raw genotype data into a clean, analysis-ready format. |

| Machine Learning Libraries (scikit-learn, TensorFlow) | Programming libraries that provide implemented versions of classification (SVM, Random Forest) and clustering (k-means, HAC) algorithms [29]. | Building and training predictive models and clustering algorithms. |

| Interaction Networks (StringDB, KEGG) | Databases of known physical and genetic interactions, or curated biological pathways [25]. | Providing a priori biological knowledge for feature selection or interpreting results from clustering [25]. |

| Cluster Validation Metrics (Silhouette Index) | Internal metrics used to evaluate the quality and determine the optimal number of clusters in an unsupervised analysis [26]. | Objectively identifying the most robust clustering structure in the data. |

Synthetic lethality (SL) describes a genetic interaction where simultaneous disruption of two genes leads to cell death, while individual disruption of either gene does not affect viability [31] [32]. This concept provides a powerful framework for precision oncology by enabling selective targeting of cancer cells bearing specific genetic alterations, such as mutations in tumor suppressor genes that are themselves difficult to target directly [33] [34]. The paradigm is exemplified by PARP inhibitors, which selectively kill cancer cells with homologous recombination deficiencies, particularly BRCA1/2 mutations [33] [32].

Advancements in data mining and high-throughput screening technologies have dramatically accelerated the discovery of synthetic lethal interactions [34] [35]. This case study examines integrated computational and experimental methodologies for identifying these interactions, with particular focus on their application within complex disease research and cancer drug development.

Key Synthetic Lethality Targets and Mechanisms

Established DNA Damage Response Targets

Table 1: Established Synthetic Lethality Targets in Cancer Therapy

| Target | Primary Function | Synthetic Lethal Partner | Therapeutic Inhibitors | Cancer Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PARP | Base excision repair (BER) of single-strand breaks [33] | BRCA1/2, other HRD genes [33] [32] | Olaparib, Niraparib, Rucaparib [33] [32] | Ovarian, breast, pancreatic, prostate cancers [33] [32] |

| ATR | Replication stress response, cell cycle checkpoint activation [33] | ATM, ARID1A, TP53 [33] [32] | In clinical development [33] | Various cancers with DDR deficiencies [33] |

| WEE1 | Cell cycle regulation, G2/M checkpoint [32] | TP53 mutations [32] | In clinical development [32] | TP53-mutant cancers [32] |

| PRMT | Arginine methylation, multiple cellular processes [32] | MTAP deletions [32] | In clinical development [32] | MTAP-deficient cancers [32] |

The mechanistic basis of PARP inhibitor sensitivity in BRCA-deficient cells involves dual mechanisms. PARP inhibitors not only block base excision repair but also trap PARP enzymes on DNA, leading to replication fork collapse and double-strand breaks that cannot be repaired in homologous recombination-deficient cells [33] [32].

Signaling Pathways for Synthetic Lethality

(Diagram 1: PARP-BRCA Synthetic Lethality Mechanism)

Computational Prediction Framework

Data Mining and Machine Learning Approaches

Table 2: Data Sources for Synthetic Lethality Prediction

| Data Type | Source Examples | Application in SL Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Interactions | Yeast SL networks [36] | Evolutionary conservation patterns [31] [36] |

| Cancer Genomics | GDSC, TCGA [34] | Identification of cancer-associated mutations [37] [34] |

| Gene Expression | CCLE, GTEx [37] | Context-specific functional relationships [37] |

| Chemical-Genetic | Drug sensitivity screens [34] | Drug-gene synthetic lethal interactions [31] [34] |

| Protein Interactions | STRING, BioGRID [36] | Network-based SL inference [36] |

Machine learning algorithms applied to these datasets include supervised learning for classifying known SL pairs, unsupervised approaches for identifying novel patterns, and reinforcement learning for de novo molecular design [38]. Specific techniques include random forests, support vector machines, and deep neural networks, which can integrate multi-omics data to predict genetic interactions [38].

The SCHEMATIC resource exemplifies modern approaches, combining CRISPR pairwise gene knockout experiments across tumor cell types with large-scale drug sensitivity assays to identify clinically actionable synthetic lethal interactions [34].

Experimental Validation Workflow

(Diagram 2: Synthetic Lethality Discovery Pipeline)

Experimental Protocols

Combinatorial CRISPR-Cas9 Screening Protocol

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide Synthetic Lethality Screening

- Objective: Identify synthetic lethal gene partners for a known cancer driver mutation (e.g., BRCA1) using combinatorial CRISPR-Cas9 screening.

Duration: 4-6 weeks

Step 1: Library Design and Preparation

Step 2: Cell Line Engineering and Infection

- Engineer your cancer cell line of interest (e.g., a BRCA1-deficient cell line) to stably express Cas9 nuclease.

- Transduce cells with the dgRNA library at a low MOI (Multiplicity of Infection ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive a single dgRNA construct.

- Culture transduced cells for 48 hours, then add puromycin (or appropriate selection antibiotic) for 5-7 days to select for successfully transduced cells.

Step 3: Screening and Sample Collection

- Passage cells continuously for 14-21 days to allow phenotypic manifestation.

- Maintain sufficient cell coverage (at least 500 cells per gRNA) throughout the screening to preserve library complexity.

- Collect a minimum of 50 million cells at both the initial (T0) and final (T14/21) time points for genomic DNA extraction.

Step 4: Sequencing and Data Analysis

- Amplify the integrated gRNA sequences from genomic DNA by PCR and subject them to next-generation sequencing.

- Map sequencing reads to the reference library to count the abundance of each gRNA pair at T0 and T14/21.

- Identify depleted gRNA pairs in the final time point using statistical frameworks like MAGeCK or drugZ, indicating potential synthetic lethal interactions.

Computational Prediction Protocol

Protocol 2: Data Mining for SL Prediction Using Multi-Omics Data

- Objective: Computationally predict synthetic lethal interactions by integrating multi-omics data from public repositories.

Duration: 2-3 weeks

Step 1: Data Collection and Integration

- Download multi-omics data (genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic) from relevant sources such as TCGA, GDSC, or CCLE.

- Preprocess the data: normalize gene expression datasets, annotate genetic variants, and impute missing values where appropriate.

Step 2: Feature Engineering

- Generate feature vectors for gene pairs, incorporating:

- Co-expression patterns across cancer types.

- Evolutionary conservation scores from model organisms.

- Network proximity in protein-protein interaction networks.

- Functional similarity based on Gene Ontology annotations.

- Mutual exclusivity of mutations in cancer cohorts.

- Generate feature vectors for gene pairs, incorporating:

Step 3: Model Training and Prediction

- Employ a supervised machine learning framework if training on known SL pairs.

- Use a positive set of known SL pairs (e.g., from SynLethDB) and a negative set of non-interacting pairs.

- Train a random forest or gradient boosting model to classify gene pairs as synthetic lethal or non-synthetic lethal.

- Apply the trained model to genome-wide gene pairs to generate novel SL predictions.

Step 4: Result Prioritization and Validation

- Prioritize candidate SL pairs based on prediction scores and clinical relevance.

- Filter for pairs where one gene is frequently altered in a cancer type of interest.

- Generate a ranked list of candidate pairs for experimental validation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Synthetic Lethality Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Screening Libraries | Genome-wide dgRNA libraries (e.g., Human Brunello library) [35] [36] | High-throughput identification of SL gene pairs via combinatorial gene knockout. |

| CRISPR System Components | Cas9 nuclease, gRNA expression vectors [35] | Enables precise gene editing for functional validation of SL candidates. |

| Viral Delivery Systems | Lentiviral, retroviral packaging systems [36] | Efficient delivery of genetic constructs into diverse cell types. |

| Viability/Cytotoxicity Assays | CellTiter-Glo, Annexin V staining, colony formation assays | Quantification of cell death and proliferation inhibition following gene perturbation. |

| Validated Chemical Inhibitors | PARPi (Olaparib), ATRi, WEE1i [33] [32] | Pharmacological validation of SL targets and combination therapy studies. |

| Bioinformatic Tools & Databases | SynLethDB, GDSC, DepMap [34] [36] | Computational prediction, analysis, and prioritization of SL interactions. |

The integration of data mining approaches with advanced experimental technologies like combinatorial CRISPR screening creates a powerful pipeline for discovering synthetic lethal interactions [34] [35]. These frameworks enable the identification of context-specific genetic vulnerabilities that can be targeted for precision oncology applications.

As these technologies mature, several challenges remain, including improving the penetrance of synthetic lethal interactions across cancer contexts and addressing acquired resistance mechanisms [32] [34]. Future directions will likely involve more sophisticated multi-omics integration, patient-specific SL prediction using artificial intelligence, and the development of next-generation screening platforms that better model tumor microenvironment complexities [37] [38]. The continued systematic discovery of synthetic lethal interactions promises to expand the repertoire of targeted therapies available for personalized cancer treatment.

The advent of high-throughput technologies has catalyzed a paradigm shift in biomedical research, moving from single-layer analyses to integrative multi-omics approaches. Multi-omics integration combines data from various molecular levels—including genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—to construct comprehensive models of biological systems and disease mechanisms [39]. This holistic perspective is particularly transformative for studying complex diseases, where pathogenesis rarely stems from aberrations in a single molecular layer but rather from dynamic interactions across multiple biological levels.

The fundamental premise of multi-omics is that biological entities function as interconnected systems rather than isolated components. As noted in a recent technical review, "the combination of several of these omics will generate a more comprehensive molecular profile either of the disease or of each specific patient" [39]. This systemic view enables researchers to move beyond correlative associations toward mechanistic understandings of disease pathogenesis, identifying novel diagnostic biomarkers, molecular subtypes, and therapeutic targets that remain invisible when examining individual omics layers in isolation.