Mastering Parameter Estimation in Systems Biology: A Comprehensive Guide to Data2Dynamics Software

This comprehensive guide explores parameter estimation and uncertainty quantification using Data2Dynamics (D2D), an open-source MATLAB toolbox specifically designed for dynamic modeling of biological systems.

Mastering Parameter Estimation in Systems Biology: A Comprehensive Guide to Data2Dynamics Software

Abstract

This comprehensive guide explores parameter estimation and uncertainty quantification using Data2Dynamics (D2D), an open-source MATLAB toolbox specifically designed for dynamic modeling of biological systems. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the article covers foundational concepts through advanced applications, including structural and practical identifiability analysis, optimization algorithms, regularization techniques, and optimal experimental design. The content addresses critical challenges in biochemical network modeling and provides practical methodologies for reliable parameter estimation, statistical assessment of uncertainties, and model validation to enhance predictive capability in biomedical research.

Understanding Data2Dynamics: Foundations for Quantitative Dynamic Modeling in Biological Systems

Data2Dynamics (D2D) is a powerful, open-source modeling environment for MATLAB specifically designed for establishing ordinary differential equation (ODE) models based on experimental data, with a particular emphasis on biochemical reaction networks [1] [2]. This computational framework addresses two of the most critical challenges in dynamical systems modeling: constructing dynamical models for large datasets and complex experimental conditions, and performing efficient and reliable parameter estimation for model fitting [2]. The software is engineered to transform experimental observations into quantitatively accurate and predictive mathematical models, making it an invaluable tool for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in systems biology and systems medicine.

A key innovation of the Data2Dynamics environment is its computational architecture. The numerically expensive components, including the solving of differential equations and associated sensitivity systems, are parallelized and automatically compiled into efficient C code, significantly accelerating the modeling process [2]. This technical optimization enables researchers to work with complex models and large datasets that would otherwise be computationally prohibitive. The software is freely available for non-commercial use and has been successfully applied across a range of scientific applications that have led to peer-reviewed publications [1] [2].

Core Capabilities and Features

Data2Dynamics provides a comprehensive suite of tools tailored to the complete model development workflow. The table below summarizes its principal capabilities:

Table 1: Core Capabilities of the Data2Dynamics Software

| Feature Category | Specific Capabilities | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Estimation | Stochastic & deterministic optimization [1] | Multiple algorithms for model calibration (parameter estimation). |

| Uncertainty Analysis | Profile likelihood & Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) [1] | Frequentist and Bayesian methods for parameter, measurement, and prediction uncertainties. |

| Data Integration | Error bars and error model fitting [1] | Handles experimental error bars and allows fitting of error parameters. |

| Model Inputs | Parameterized functions & cubic splines [1] | Inputs can be estimated together with model dynamics. |

| Numerical Performance | Parallelized C code compilation [2] | Efficient calculation of dynamics and derivatives. |

| Regularization | L1 regularization & L2 priors [1] | Incorporates prior knowledge and regularizes parameter fold-changes. |

| Experimental Design | Identification of informative designs [1] | Supports optimal design of experiments. |

A distinguishing feature of D2D is its robust approach to uncertainty. It moves beyond mere curve-fitting to provide a full statistical assessment of the identified parameters and predictions [1]. This is crucial for evaluating the reliability of a model's conclusions. Furthermore, the framework supports the use of splines to model system inputs, which can be estimated simultaneously with the model's dynamic parameters, offering significant flexibility for handling complex experimental conditions [1].

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Estimation

The following section details a standard protocol for estimating parameters and assessing model quality using the Data2Dynamics environment. This workflow is fundamental for calibrating ODE models to experimental data.

Protocol 1: Core Workflow for Model Calibration and Uncertainty Analysis

Primary Objective: To estimate unknown model parameters, validate the model fit, and quantify the practical identifiability and uncertainty of the estimated parameters.

Materials and Reagents:

- Software: MATLAB installation with the Data2Dynamics toolbox installed.

- Computational Resources: A multi-core computer is recommended to leverage the built-in parallelization.

- Data: Quantitative time-course experimental data. The data should be in a format compatible with D2D (e.g., tabular data specifying measured species, time points, values, and associated uncertainties).

Procedure:

- Model Definition: Formulate the ODE model representing the biochemical network. This includes defining the state variables (e.g., species concentrations), parameters (e.g., kinetic rates), and the system of differential equations describing their interactions.

- Data Integration and Error Modeling: Load the experimental data into the D2D environment. Define the observation function that links the model's states to the measurable data. Specify the error model, which can either use experimental error bars provided with the data or fit error parameters simultaneously with the model parameters [1].

- Parameter Estimation (Calibration): Select an optimization algorithm (e.g., deterministic or stochastic) to minimize the discrepancy between the model output and the experimental data [1]. This step finds the parameter set that provides the best fit.

- Practical Identifiability Analysis: After finding the best-fit parameters, perform a practical identifiability analysis using the profile likelihood approach [1] [3]. This involves re-optimizing all other parameters while constraining one parameter to a range of fixed values, thereby generating a likelihood profile for each parameter. A parameter is considered practically identifiable if its profile likelihood has a unique minimum.

- Uncertainty Quantification: Use the results from the profile likelihood analysis to calculate confidence intervals for the parameters [1]. For a more comprehensive Bayesian uncertainty assessment, employ the implemented Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling methods [1] [2].

- Model Validation and Prediction: Simulate the model with the estimated parameters and confidence intervals to validate its performance against data not used for calibration. Use the validated model to generate predictions for new experimental conditions.

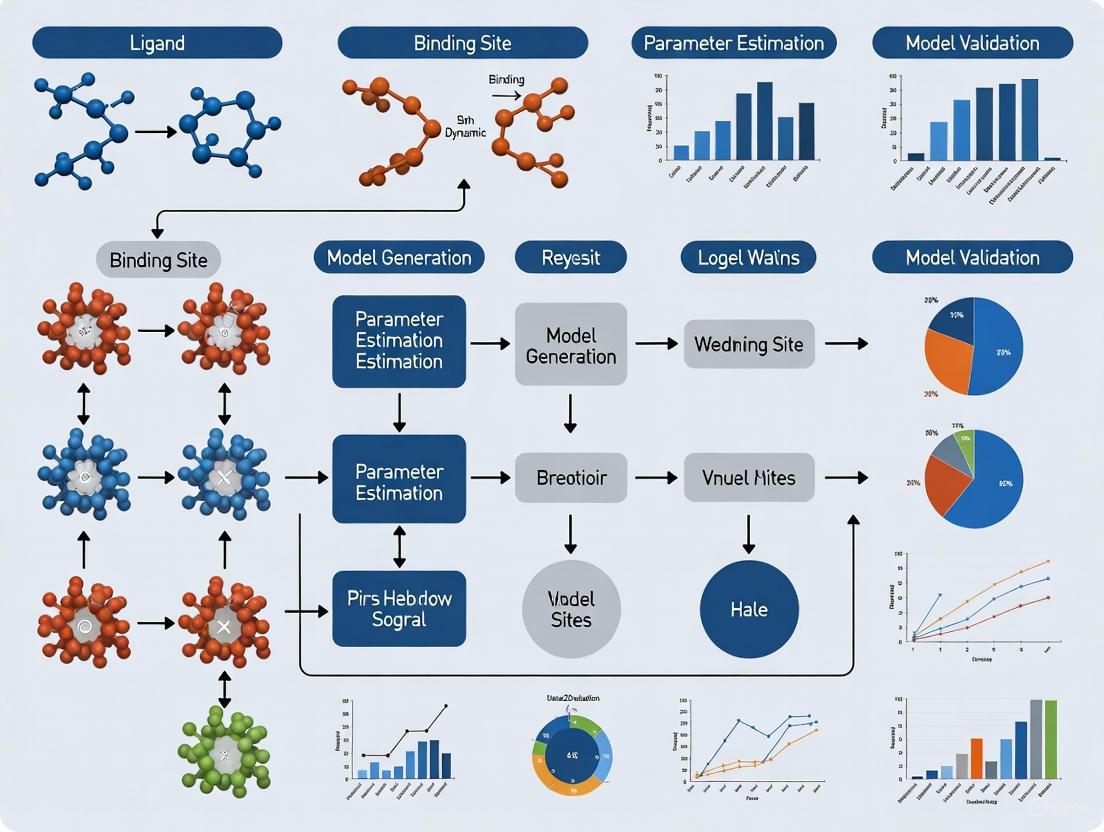

Diagram Title: D2D Parameter Estimation Workflow

Advanced Application: Identifiability Analysis

A fundamental challenge in dynamical modeling is identifiability—whether the available data are sufficient to uniquely determine the model's parameters [4]. Data2Dynamics provides integrated methodologies to address this critical issue.

Structural vs. Practical Identifiability

Identifiability is categorized into two main types:

- Structural Identifiability: A parameter is structurally non-identifiable if, even with perfect, noise-free infinite data, it cannot be uniquely determined due to the model's structure (e.g., over-parameterization). While D2D is a tool for application, recent methodological developments like the StrucID algorithm are advancing the field of structural identifiability analysis for ODE models [4].

- Practical Identifiability: A parameter is practically non-identifiable when the available experimental data is insufficient in quantity or quality to estimate the parameter reliably, often due to noise or limited measurements [4] [3]. This is a primary focus of the D2D framework.

Protocol 2: Assessing Practical Identifiability via Profile Likelihood

Objective: To determine which parameters of a calibrated model are practically identifiable given the specific dataset.

Procedure:

- Model Calibration: Complete the core parameter estimation protocol to obtain a best-fit parameter set.

- Profile Setup: Select a parameter of interest. Define a realistic range of values around its best-fit estimate.

- Profile Calculation: For each fixed value of the selected parameter in the defined range, re-optimize all other free parameters in the model. This generates a profile likelihood curve, which is a plot of the optimization objective value (e.g., log-likelihood) against the fixed parameter value.

- Interpretation: Analyze the profile likelihood curve. A parameter is practically identifiable if its profile exhibits a clear, unique minimum. A flat profile or a profile with multiple minima of similar height indicates practical non-identifiability [3].

- Iteration: Repeat this process for all key parameters in the model to create a diagnotic overview of the model's practical identifiability.

Diagram Title: Identifiability Analysis Framework

Integrated Workflow in Drug Target Identification

Data2Dynamics often serves as a critical component in larger, integrated software pipelines for drug discovery. A prominent example is the DataXflow framework, which synergizes D2D for data-driven modeling with optimal control theory to identify efficient drug targets [5].

In this integrated approach:

- Topology Definition: The regulatory network (topology) of the disease system, such as a gene network in cancer, is defined.

- Model Calibration with D2D: D2D is used to translate the network topology into a system of ODEs (e.g., using the SQUAD model) and fit the model parameters to quantitative measurement data, such as transcriptome data from cancer cell lines [5].

- Optimal Control: Once a well-fitting model is established, an optimal control framework purposefully exploits the encoded information. Therapeutic interventions (e.g., drug inhibitions or activations) are modeled as external stimuli. The framework calculates the most efficient combination of these stimuli to steer the system from a pathological state (e.g., high proliferation) to a desired physiological state (e.g., high apoptosis) [5].

A showcased application used this pipeline with data from a non-small cell lung cancer cell line, identifying the inhibition of Aurora Kinase A (AURKA) and activation of CDH1 as a highly efficient drug target combination to overcome therapy resistance [5]. This demonstrates how D2D's rigorous parameter estimation underpins the discovery of plausible therapeutic strategies in complex networks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key "research reagents" and tools essential for conducting experiments with the Data2Dynamics software.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Type | Function in the Modeling Process |

|---|---|---|

| Data2Dynamics (D2D) [1] [2] | Software Environment | The core MATLAB-based toolbox for model definition, parameter estimation, and uncertainty analysis. |

| MATLAB [2] | Software Platform | The required numerical computing platform that hosts the D2D environment. |

| Experimental Dataset [5] | Data | Quantitative time-course data (e.g., protein concentrations, mRNA levels) used to calibrate the model. |

| ODE Model | Mathematical Construct | The system of ordinary differential equations formally describing the biochemical reaction network. |

| Optimization Algorithms [1] | Computational Method | Stochastic or deterministic algorithms (e.g., particle swarm, trust-region) used to find best-fit parameters. |

| Profile Likelihood [1] [3] | Analytical Method | The primary method implemented in D2D for assessing practical identifiability of parameters. |

| Error Model [1] | Statistical Construct | Defines how measurement errors are handled, either from data or as parameters to be estimated. |

Data2Dynamics is a powerful, open-source modeling environment for MATLAB, specifically tailored to the challenges of parameter estimation in dynamical systems described by ordinary differential equations (ODEs). While its development was driven by applications in systems biology, particularly for modeling biochemical reaction networks, its capabilities are applicable to a wide range of dynamic modeling problems. The core purpose of this software is to facilitate the construction of dynamical models from experimental data, providing reliable and efficient model calibration alongside a comprehensive statistical assessment of uncertainties. This makes it an invaluable tool for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who need to build predictive models from complex, noisy biological data [1] [2].

Core Features and Capabilities

The Data2Dynamics software integrates a suite of numerical methods designed to address the complete modeling workflow. Its features can be categorized into three main areas: parameter estimation, uncertainty analysis, and computational efficiency.

Table 1: Core Features of the Data2Dynamics Software

| Feature Category | Specific Methods/Techniques | Description and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Estimation | Deterministic & Stochastic Optimization Algorithms | Finds parameter values that minimize the deviation between model prediction and experimental data [1]. |

| L1 and L2 Regularization | Incorporates prior knowledge and penalizes parameter fold-changes to prevent overfitting [1]. | |

| Treatment of Inputs | Model inputs can be implemented as parameterized functions or cubic splines and estimated with model dynamics [1]. | |

| Uncertainty Analysis | Profile Likelihood | A frequentist approach for assessing practical identifiability and confidence intervals of parameters and predictions [1] [6]. |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) | A Bayesian method for sampling from parameter posterior distributions [1]. | |

| Two-Dimensional Profile Likelihood | Used for optimal experimental design by quantifying expected parameter uncertainty for a specified experimental condition [6]. | |

| Data & Error Handling | Explicit Error Bars | Incorporates known measurement noise of experimental data [7]. |

| Parametrized Noise Models | Allows for the simultaneous estimation of error parameters (e.g., magnitude of noise) alongside model dynamics [7] [1]. | |

| Computational Efficiency | Parallelized Solvers & Derivatives | Numerical solvers and sensitivity calculations are parallelized and automatically compiled into efficient C code for speed [2]. |

| PARFOR Loops | Leverages the MATLAB Distributed Computing Toolbox for additional parallelization [7]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Core Parameter Estimation and Practical Identifiability Analysis

This protocol outlines the steps for calibrating a dynamic model and assessing the practical identifiability of its parameters using the profile likelihood approach within Data2Dynamics.

Step 1: Model Definition and Data Integration

- 1.1. Define the ODE Model: Formulate the system of ordinary differential equations representing the biochemical network. The model is defined as

x˙(t) = f(x, p, u), wherexare biological states,pare model parameters, anduare experimental perturbations [6]. - 1.2. Specify Observables and Noise Model: Define the observables

y(t) = g(x(t), s_obs) + ϵ, which link the model states to measurable quantities. The measurement noiseϵcan be defined as normally distributed, with its magnitude (s_err) either provided or estimated [6].

- 1.1. Define the ODE Model: Formulate the system of ordinary differential equations representing the biochemical network. The model is defined as

Step 2: Parameter Estimation via Numerical Optimization

- 2.1. Define the Objective Function: The software constructs an objective function (e.g., a likelihood function) that quantifies the discrepancy between model simulations and experimental data.

- 2.2. Perform Optimization: Use either deterministic (e.g., gradient-based) or stochastic (e.g., evolutionary) optimization algorithms provided by Data2Dynamics to find the parameter set

p*that minimizes the objective function [1].

Step 3: Practical Identifiability Analysis using Profile Likelihood

- 3.1. Profile Calculation: For each parameter of interest

p_i, the profile likelihood is computed by repeatedly optimizing over all other parametersp_j (j≠i)while constrainingp_ito a range of fixed values around its estimated valuep_i*[6]. - 3.2. Confidence Interval Evaluation: Determine the confidence intervals for each parameter based on the likelihood ratio test. A parameter is deemed practically unidentifiable if its profile likelihood does not exceed the confidence threshold at its bounds, indicating that the available data is insufficient to constrain it [4].

- 3.1. Profile Calculation: For each parameter of interest

Protocol for Optimal Experimental Design using 2D Profile Likelihood

This protocol describes how to use the two-dimensional profile likelihood method to design informative experiments that reduce parameter uncertainty.

Step 1: Initial Model Calibration

- Calibrate the model using all currently available data, following the protocol in Section 3.1, to obtain a preliminary parameter estimate and uncertainty quantification.

Step 2: Define Candidate Experimental Conditions

- Identify a set of feasible future experimental conditions. This could include different time points for measurement, various doses of a perturbation, or different observable outputs to measure [6].

Step 3: Construct Two-Dimensional Profile Likelihoods

- 3.1. For a target parameter

θand a candidate experimental condition, the software calculates a two-dimensional profile. This profile evaluates the expected profile likelihood forθacross a range of possible measurement outcomesy_expfor that new experiment [6]. - 3.2. The range of reasonable measurement outcomes

y_expis informed by the current model knowledge, using concepts like validation profiles [6].

- 3.1. For a target parameter

Step 4: Calculate Expected Uncertainty Reduction

- For each candidate experimental condition, compute a design criterion (e.g., the expected average width of the confidence interval for

θafter performing the experiment) based on the two-dimensional profile likelihood [6].

- For each candidate experimental condition, compute a design criterion (e.g., the expected average width of the confidence interval for

Step 5: Select and Execute Optimal Design

- 5.1. Compare the design criteria across all candidate conditions and select the one that is predicted to minimize the uncertainty of the target parameter(s) the most.

- 5.2. Perform the wet-lab experiment under the chosen optimal condition.

- 5.3. Integrate the new data point into the dataset and re-estimate the parameters. The uncertainty of the target parameter

θshould be substantially reduced, validating the design [6].

Workflow Visualization

Parameter Estimation and Uncertainty Analysis Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the integrated workflow for model calibration, identifiability analysis, and optimal experimental design in Data2Dynamics.

Model Calibration and Refinement Workflow

Optimal Experimental Design Logic

This diagram details the logical decision process and algorithm behind the active learning approach for efficient data collection, as implemented in tools like E-ALPIPE.

Active Learning for Practical Identifiability

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key computational tools and conceptual "reagents" essential for working with the Data2Dynamics environment.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Type | Function in the Research Process |

|---|---|---|

| Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) System | Mathematical Model | Represents the dynamic behavior of the biochemical reaction network, forming the core hypothesis of the system's mechanism [2] [6]. |

| Experimental Dataset | Data | Time-resolved measurements of biological observables used to calibrate the ODE model and estimate its parameters [2]. |

| Parameterized Noise Model | Statistical Model | Quantifies the measurement error of experimental data, allowing for simultaneous estimation of model dynamics and error parameters [7] [1]. |

| Profile Likelihood Function | Computational Algorithm | Assesses practical identifiability of parameters and determines reliable confidence intervals, overcoming limitations of asymptotic approximations [1] [6]. |

| Two-Dimensional Profile Likelihood | Experimental Design Tool | Predicts the uncertainty reduction for a parameter of interest under a candidate experiment, enabling optimal design before wet-lab work [6]. |

| Parallelized ODE Solver | Computational Tool | Speeds up the numerical solution of differential equations and associated sensitivity systems by leveraging multi-core processors [7] [2]. |

System Requirements and Software Dependencies

Minimum System Requirements

The following table summarizes the minimum hardware and software requirements for running Data2Dynamics:

| Component | Minimum Requirement | Recommended Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Operating System | Windows, macOS, or Linux supporting MATLAB | Windows 11/10, macOS latest, or Linux latest |

| MATLAB Version | MATLAB R2018b or later | MATLAB R2021b or later |

| Processor | Dual-core CPU | Quad-core or higher processor |

| Memory | 8 GB RAM | 16 GB RAM or more |

| Storage | 500 MB free space | 1 GB free space for models and data |

| Additional Toolboxes | - | Parallel Computing Toolbox [7] |

Required MATLAB Toolboxes and Components

| Component | Function | Requirement Level |

|---|---|---|

| MATLAB Base | Core computational engine | Mandatory |

| Parallel Computing Toolbox | PARFOR loops and distributed computing [7] | Optional but recommended |

| Optimization Toolbox | Parameter estimation algorithms | Beneficial |

MATLAB Environment Configuration

Hardware Implementation Settings

Configure MATLAB's hardware settings for optimal performance with Data2Dynamics:

| Configuration Parameter | Recommended Setting | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Byte Ordering | Match production hardware (Little/Big Endian) [8] | Ensures bit-true agreement for results |

| Signed Integer Division | Set based on compiler (Zero/Floor) [8] | Optimizes generated code |

| Data Type Bit Lengths | char ≤ short ≤ int ≤ long (max 32 bits) [8] | Maintains compatibility |

| Array Layout | Column-major [9] | MATLAB's native array format |

Code Generation Configuration

| Setting Category | Parameter | Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| Target Selection | System target file | grt.tlc (Generic Real-Time) |

| Build Process | Generate code only | Enabled for model development |

| Code Generation Objectives | Check model before generating code | Enabled [9] |

| Comments | Include MATLAB source code as comments | Enabled for traceability [9] |

Data2Dynamics Installation Protocol

Installation Procedure

Post-Installation Verification

| Verification Step | Expected Outcome | Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| Path Verification | Data2Dynamics functions accessible in MATLAB | Manually add installation directory to MATLAB path |

| Example Execution | Bachmann et al. 2011 example runs successfully [7] | Check for missing dependencies |

| Parallel Processing | Parallel workers start (if toolbox available) [7] | Verify Parallel Computing Toolbox license |

Experimental Setup for Parameter Estimation

Computational Workflow for Model Calibration

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Software Tool | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Data2Dynamics Modeling Environment | ODE model construction and calibration [1] | Dynamic modeling of biochemical reaction networks |

| Experimental Biomolecular Data | Quantitative measurements for model calibration [10] | Parameter estimation and model training |

| Noise Model Parameters | Characterization of measurement errors [11] | Statistical assessment of data quality |

| C Code Compiler | Acceleration of numerical computations [12] | Improved performance for differential equation solving |

| Parallel Computing Toolbox | Distributed parameter estimation [7] | Reduced computation time for complex models |

Configuration for High-Performance Computing

Parallel Processing Configuration

| Setting | Configuration | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| PARFOR Loops | Enable for parameter scans [7] | Distributed parameter estimation |

| Sensitivity Calculations | Parallelized solvers [12] | Faster gradient calculations |

| Number of Workers | Set based on available CPU cores | Optimized resource utilization |

Memory and Storage Optimization

| Parameter | Setting | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum Array Size | Based on available RAM | Prevents memory overflow |

| Caching of Results | Enable for repeated calculations | Reduces computation time |

| Data Logging | Selective output saving | Minimizes storage requirements |

Validation and Testing Protocol

System Verification Procedure

Execute the following steps to validate your Data2Dynamics installation:

- Basic Functionality Test: Run the provided Bachmann et al. 2011 example [7]

- Performance Benchmark: Time execution of parallel versus serial computation

- Accuracy Verification: Compare results with published outcomes [10]

- Toolbox Integration: Confirm optional toolboxes are properly detected

This configuration framework provides researchers with a robust foundation for parameter estimation studies using Data2Dynamics, ensuring reproducible and computationally efficient modeling of dynamical systems in biochemical applications.

The quantitative understanding of cellular processes, such as signal transduction and metabolism, hinges on the ability to construct and calibrate mechanistic mathematical models [13]. This document outlines core principles and protocols for formulating such models, specifically transitioning from descriptions of biochemical reactions to systems of Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs). This process forms the essential first step in a broader research pipeline focused on parameter estimation, wherein tools like the Data2Dynamics (D2D) software are employed for reliable parameter inference, uncertainty quantification, and model selection [14] [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering this formulation is critical for building interpretable models that can predict system dynamics, identify key regulatory nodes, and ultimately inform therapeutic strategies [15].

Part I: Theoretical Foundations

The Mass Action Principle as the Basis for ODEs

The translation of a biochemical reaction network into ODEs is most commonly founded on the law of mass action. This principle states that the rate of an elementary reaction is proportional to the product of the concentrations of its reactants, with a constant of proportionality known as the rate constant [13]. This approximation assumes a well-mixed, deterministic system with a sufficiently large number of molecules (typically >10²–10³) to neglect stochastic fluctuations [13].

- Formal Representation: An elementary biochemical reaction is written as: ( \sumi \alphai Si \xrightarrow{k} \sumj \betaj Pj ) where (Si) are substrate species, (Pj) are product species, (\alphai) and (\betaj) are stoichiometric coefficients, and (k) is the rate constant.

- ODE Derivation: The contribution of this single reaction to the rate of change of a species concentration (X) is given by ( k \prodi [Si]^{\alphai} ), multiplied by the net stoichiometric coefficient of (X) ((\betaX - \alpha_X)). The total ODE for (X) is the sum of contributions from all reactions in which it participates [16].

The Canonical Example: Michaelis-Menten Enzymatic Reaction

The foundational model for enzyme kinetics illustrates the formulation process and the relationship between a full ODE model and familiar simplified approximations [13].

Biochemical Reaction Scheme: ( E + S \underset{kr}{\stackrel{kf}{\rightleftharpoons}} C \xrightarrow{k_{cat}} E + P )

Full ODE System (Mass Action): The resulting ODEs for the concentrations of substrate ([S]), enzyme ([E]), complex ([C]), and product ([P]) are: [ \begin{aligned} \frac{d[S]}{dt} &= -kf [E][S] + kr [C] \ \frac{d[E]}{dt} &= -kf [E][S] + (kr + k{cat})[C] \ \frac{d[C]}{dt} &= kf [E][S] - (kr + k{cat})[C] \ \frac{d[P]}{dt} &= k{cat} [C] \end{aligned} ] Under the quasi-steady-state assumption ((d[C]/dt ≈ 0)) for conditions where the enzyme is much less concentrated than the substrate, this system reduces to the classic Michaelis-Menten equation for the initial velocity (v = d[P]/dt): [ v = \frac{V{max} [S]}{KM + [S]} ] where (V{max} = k{cat}[E]{total}) and (KM = (kr + k{cat})/kf) [13].

Key Considerations in Model Formulation

- Deterministic vs. Stochastic: While mass-action ODEs are deterministic, stochastic models (e.g., using the Chemical Master Equation) are necessary for systems with low copy numbers [13].

- Spatial Effects: Transport and diffusion are modeled using Partial Differential Equations (PDEs). In ODE frameworks, spatial compartmentalization is often represented as separate, well-mixed volumes linked by transport reactions [13].

- Modeling Observable Outputs: Experimental measurements ((z)) often do not directly reflect model state variables ((x)). They are related via an observation function (h) and a measurement mapping (g), which can be linear (e.g., (g(x)=a \cdot x + b)) or nonlinear (e.g., a saturating fluorescence readout) [17]. [ z = g(h(x, \theta)) + \varepsilon ] where (\varepsilon) is measurement noise. Correctly specifying this mapping is crucial for parameter estimation [17].

Part II: Practical Protocols & Application Notes

Protocol: From a Reaction Diagram to a Simulatable ODE Model

This protocol details the steps to implement a formulated ODE model in a computational environment suitable for subsequent analysis with parameter estimation tools like D2D.

Materials & Software:

- Diagramming Tool (e.g., draw.io) to define the reaction network.

- Mathematical Software (e.g., MATLAB with D2D toolbox [1], Python with PySB or pyPESTO [17], or Mathematica [16]).

- ODE Solver: A robust numerical integrator (e.g., CVODE, ode15s). The D2D software provides efficient integration [1].

Procedure:

- Define Species and Compartments: List all chemical species (e.g., proteins, metabolites, complexes) and their putative locations (e.g., cytosol, nucleus).

- List All Elementary Reactions: Decompose biochemical mechanisms into reversible/irreversible binding, catalytic, and translocation steps. Assign a symbolic rate constant to each reaction arrow.

- Write Stoichiometric Equations: For each reaction, write the balanced chemical equation.

- Apply Mass Action Kinetics: For each species, derive its ODE by summing mass action terms from all reactions.

- Implement in Software: a. In a D2D model definition file (MATLAB), species and parameters are declared, and ODEs are written in a dedicated function [1]. b. Alternatively, in Python/pyPESTO, models can be defined using the AMICI or PEtab standards.

- Simulate and Verify: Perform an initial simulation with guessed parameters to check for conservation laws, expected steady-states, and numerical stability.

Protocol: Designing Experiments for Parameter Estimation

Reliable parameter estimation requires informative data. This protocol guides the experimental design for generating such data [14].

Key Considerations:

- Perturbations: Measure system responses to targeted perturbations (e.g., kinase inhibitors, gene knockdowns, ligand stimulations) to probe different parts of the network.

- Temporal Resolution: Time-course data should have sufficient density to capture the dynamics of interest (e.g., rapid phosphorylation vs. slow gene expression).

- Observable Selection: Prioritize measuring species that are direct outputs of the model's observation function (h). If using semi-quantitative readouts (e.g., FRET), plan for calibration experiments or use estimation methods that can infer the nonlinear mapping (g) [17].

- Replication: Include biological and technical replicates to estimate measurement noise levels.

Experimental Workflow Diagram:

Protocol: Parameter Estimation & Uncertainty Analysis using Data2Dynamics

This protocol details the core steps of model calibration using the D2D software, a cornerstone of the referenced thesis research [14] [1].

Procedure:

- Model and Data Integration: Load the ODE model definition and the experimental data into D2D. Specify the observation function (h) and the measurement mapping (e.g., linear scaling with parameters

a,b) for each dataset. - Define the Objective Function: D2D typically uses a Maximum Likelihood approach. The objective function is the negative log-likelihood, which quantifies the misfit between model simulations and data, weighted by measurement noise [14] [17].

- Multi-Start Optimization: Due to the non-convex nature of the problem, perform optimization from many randomly sampled starting points for the parameters. D2D supports both local (e.g.,

fmincon) and global (e.g.,PSwarm) optimizers [1]. - Identifiability Analysis & Confidence Intervals: Use the Profile Likelihood method to assess which parameters are identifiable from the data and to compute confidence intervals. This involves re-optimizing the objective function while constraining one parameter at a time [14].

- Prediction Uncertainty: Use the profile likelihood or sampling methods to propagate parameter uncertainties to predictions of unmeasured observables or new experimental conditions.

- Model Selection: Use likelihood ratio tests to compare competing model structures (e.g., different reaction mechanisms) [14].

Parameter Estimation Workflow Diagram:

Part III: Data, Tools, and Advanced Frameworks

The table below summarizes key characteristics of well-studied models that serve as benchmarks for formulation and estimation methods.

Table 1: Benchmark Models for Formulation and Parameter Estimation

| Model Name | Biological Process | Key Features (Stiffness, Nonlinearity) | Number of States (nx) | Number of Typical Parameters (nθ) | Reference Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Michaelis-Menten | Enzyme Kinetics | Fast equilibration, model reduction. | 4 | 3 (kf, kr, kcat) | [13] |

| Glycolytic Oscillator | Central Metabolism | Nonlinear feedback, stable oscillations, stiff. | 7 | 12+ | [15] |

| JAK-STAT Signaling | Cytokine Signaling | Multi-compartment, delays, widely used for estimation benchmarks. | ~10-15 | 20+ | [14] |

| EGFR/ERK Pathway | Growth Factor Signaling | Large network, multiple phosphorylation cycles, semi-quantitative data. | 20+ | 50+ | [17] |

| Calcium Oscillations | Cell Signaling | Positive & negative feedback, non-mass action kinetics (e.g., Hill functions). | 3-7 | 10+ | [16] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists critical software and methodological "reagents" for implementing the described protocols.

Table 2: Essential Toolkit for ODE Model Formulation & Estimation

| Tool / Solution | Primary Function | Role in the Research Pipeline | Key Feature for Parameter Estimation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data2Dynamics (D2D) [1] | Integrated modeling environment (MATLAB). | Core platform for model definition, simulation, parameter estimation, and uncertainty analysis. | Implements profile likelihood for confidence intervals; efficient gradients. |

| pyPESTO [17] | Parameter EStimation TOolbox (Python). | Portable framework for parameter estimation, profiling, and sampling. | Modular, connects to various model simulators (AMICI, PEtab). |

| AMICI | Advanced Multilanguage Interface for CVODES. | High-performance ODE solver & sensitivity analysis engine. | Provides exact gradients for optimization, essential for scalability. |

| Mathematica [16] | Symbolic mathematics platform. | Prototyping model formulation, symbolic derivation, and educational exploration. | Symbolic manipulation of ODEs and analytic solutions (when possible). |

| Universal Differential Equations (UDEs) [15] | Hybrid modeling framework. | Embedding neural networks within ODEs to model unknown mechanisms. | Balances mechanistic knowledge with data-driven flexibility; requires careful regularization. |

| Spline-based Mapping [17] | Method for handling semi-quantitative data. | Inferring the unknown nonlinear measurement function (g) during estimation. | Allows use of FRET, OD data without prior calibration; implemented in pyPESTO. |

Advanced Framework: Universal Differential Equations (UDEs)

For systems with partially unknown mechanisms, UDEs offer a powerful extension to pure mechanistic ODEs. A UDE replaces a part of the ODE's vector field (f(x,θ)) with an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) [15]: [ \dot{x} = f{\text{known}}(x, θM) + ANN{\text{unknown}}(x, θ{ANN}) ] Protocol Notes for UDEs:

- Formulation: Clearly separate mechanistically interpretable parameters (θM) (e.g., known rate constants) from black-box ANN parameters (θ{ANN}).

- Training: Use a multi-start pipeline combining best practices from systems biology (likelihood, parameter bounds) and machine learning (regularization like weight decay, early stopping) [15].

- Regularization: Apply L2 regularization ((λ||θ{ANN}||^22)) to prevent the ANN from overfitting and absorbing dynamics that should be attributed to the mechanistic part, preserving interpretability of (θ_M) [15].

- Software: Implement using flexible frameworks like Julia's SciML or by combining pyPESTO/PyTorch.

Observable Mapping Diagram (Linear vs. Nonlinear):

Effective parameter estimation in dynamical systems modeling, particularly within biochemical reaction networks, hinges on the precise integration of quantitative experimental data and the explicit specification of error models. This application note details the methodologies for data preparation, error model formulation, and subsequent analysis using the Data2Dynamics (D2D) modeling environment [1] [12]. Framed within a broader thesis on robust parameter estimation, this guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with structured protocols to enhance the reliability and identifiability of their mathematical models.

Quantitative dynamic modeling of biological systems using ordinary differential equations (ODEs) is a cornerstone of systems biology and drug development [18]. The Data2Dynamics software is a MATLAB-based environment specifically tailored for establishing ODE models based on experimental data, with a key feature being reliable parameter estimation and statistical assessment of uncertainties [1] [7]. The calibration of these models involves minimizing the discrepancy between noisy experimental data and model trajectories, a process fundamentally dependent on the quality and structure of the input data and the statistical treatment of measurement noise [18]. This document outlines the necessary data formats, proposes standard error models, and provides detailed experimental protocols to guide users in preparing inputs for successful model calibration and practical identifiability analysis [19].

Data Formats for Integration

Experimental data for D2D must be structured to link quantitative observations to model states. The observations are linked via observation functions g to the model states x(t), and include observation parameters (e.g., scalings, offsets) [18]. Data can be provided with or without explicit measurement error estimates.

Table 1: Standard Data Input Format for Time-Course Experiments

| Column Name | Description | Data Type | Required | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

observableId |

Identifier linking to model observable | String | Yes | pSTAT5A_rel |

time |

Measurement time point | Numeric | Yes | 15.0 |

measurement |

Quantitative readout (e.g., concentration, intensity) | Numeric | Yes | 0.85 |

scale |

Scaling factor (if part of observation parameters) | Numeric | No | 1.0 |

offset |

Additive offset (if part of observation parameters) | Numeric | No | 0.1 |

sd |

Standard deviation of measurement noise (if known) | Numeric | No | 0.05 |

expId |

Identifier for distinct experimental conditions | String | Yes | Exp1_10nM_IL6 |

Error Model Specification

The D2D framework can deal with experimental error bars but also allows fitting of error parameters (error models) [1]. This dual approach is critical for accurate likelihood calculation during parameter estimation.

Table 2: Common Error Models for Measurement Noise

| Model Name | Formula | Parameters | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant Variance | σ² = σ₀² |

σ₀ (noise magnitude) |

Homoscedastic noise across all data points. |

| Relative Error | σ² = (σ_rel * y_model)² |

σ_rel (relative error) |

Noise proportional to the signal magnitude. |

| Combined Error | σ² = σ₀² + (σ_rel * y_model)² |

σ₀, σ_rel |

Accounts for both absolute and relative noise components. |

| Parameterized Error Model | User-defined function linking σ to y_model and parameters θ_error |

θ_error |

For complex, experimentally-derived noise structures. |

Measurement noise ε is typically assumed to be additive and normally distributed, ydata = g(x(t), θobs) + ε, where ε ~ N(0, σ²) [18]. The parameters of the chosen error model (σ₀, σ_rel, etc.) can be estimated simultaneously with the dynamical model parameters during calibration [1].

Title: Integration of Error Models into Parameter Estimation Workflow

Protocols for Practical Identifiability Analysis

Practical identifiability analysis (PIA) assesses whether available data are sufficient for reliable parameter estimates. The E-ALPIPE algorithm is an active learning method that recommends new data points to establish practical identifiability efficiently [19].

Protocol: Sequential Active Learning for Optimal Experimental Design

Objective: To minimize the number of experimental observations required to achieve practically identifiable parameters. Materials: An initial dataset, a calibrated mathematical model, and the E-ALPIPE algorithm implementation. Procedure:

- Initialization: Perform multistart parameter estimation on the initial dataset to obtain a profile likelihood-based confidence interval for each parameter [19] [18].

- Candidate Generation: Define a set of feasible new experimental conditions (e.g., time points, perturbations).

- Point Selection: For each candidate, simulate expected data and compute the expected reduction in the width of profile likelihood confidence intervals for all parameters.

- Recommendation: Select the candidate point predicted to yield the largest overall reduction in parameter uncertainty.

- Iteration: Conduct the recommended experiment, add the new data point to the dataset, and repeat steps 1-4 until all parameters are deemed practically identifiable (confidence intervals below a predefined threshold). Outcome: A minimally sufficient dataset for reliable parameter estimation, reducing cost and resource consumption [19].

Title: Active Learning Loop for Efficient Data Collection

Protocol: Multistart Optimization and Result Grouping with Nudged Elastic Band

Objective: To reliably distinguish between distinct local optima and suboptimal, incompletely converged fits in complex parameter landscapes.

Materials: D2D software, a defined model and dataset, a local optimizer (e.g., fmincon), and an implementation of the Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) method [18].

Procedure:

- Multistart Optimization: Run a large number (e.g., >100) of local optimizations from randomly sampled initial parameter guesses [18].

- Cluster Results: Group endpoint parameter vectors with similar objective function values.

- Path Finding (NEB): For pairs of fits within a cluster, use the NEB method to find an optimal path in parameter space connecting them. The method minimizes a combined action of the objective function and spring forces between discretized "images" along the path [18].

- Profile Analysis: Examine the profile of the objective function along the calculated path.

- If the profile shows a smooth, monotonic transition without exceeding a statistically significant threshold (e.g., a likelihood ratio threshold), the fits belong to the same optimum basin.

- If a significant barrier exists, they represent distinct local optima.

- Group Merging: Merge all fits connected by barrier-free paths into a single group representing one unique optimum. Outcome: A validated grouping of optimization results, clarifying the true number of local optima and ensuring robust parameter selection [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Parameter Estimation in Dynamical Systems

| Item | Function / Description | Relevance to Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Data2Dynamics (D2D) Software | MATLAB-based modeling environment for ODEs. Provides parallelized solvers, parameter estimation, and uncertainty analysis [1] [12]. | Core platform for all modeling, fitting, and PIA workflows. |

| Quantitative Immunoblotting Data | Time-course measurements of protein phosphorylation or abundance. Provides observableId, time, measurement, and sd for Table 1. |

Primary source of quantitative data for signaling pathway models. |

| E-ALPIPE Algorithm Code | Implementation of the sequential active learning algorithm for practical identifiability [19]. | Protocol 4.1 for optimal experimental design. |

| Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) Code | Implementation for finding optimal paths between parameter estimates in high-dimensional landscapes [18]. | Protocol 4.2 for analyzing multistart optimization results. |

| Profile Likelihood Calculation Scripts | Routines to compute confidence intervals by exploring likelihood profiles for each parameter. | Used in PIA (Protocol 4.1) and for statistical assessment [1]. |

| Global & Local Optimizers | Particle swarm, simulated annealing (global); fmincon, lsqnonlin (local). Configured within D2D for multistart strategies [18]. |

Essential for the parameter estimation step in all protocols. |

| Error Model Template Functions | MATLAB functions encoding the mathematical forms in Table 2 (Constant, Relative, Combined error). | Required for accurate likelihood calculation during model calibration. |

Parameter estimation is a fundamental challenge in systems biology, where mechanistic models of biological processes are calibrated using experimental data to yield accurate and predictive insights. The Data2Dynamics modeling environment for MATLAB is a powerful tool tailored specifically for this purpose, enabling reliable parameter estimation and uncertainty analysis for dynamical systems described by ordinary differential equations (ODEs) [2] [20]. This computational framework efficiently handles the numerical solution of differential equations and associated sensitivity systems by parallelizing calculations and compiling them into efficient C code, making it particularly suited for complex biological networks and large datasets [2] [1].

Within systems biology, robust parameter estimation is critical for constructing meaningful models across several core application areas, including cellular signaling networks, pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) studies, and infectious disease dynamics. By implementing advanced parameter estimation algorithms alongside both frequentist and Bayesian methods for uncertainty analysis, Data2Dynamics provides researchers with a comprehensive environment for model calibration, validation, and experimental design [1] [10]. This article details established protocols and applications of Data2Dynamics within these domains, providing practical guidance for researchers seeking to implement this powerful tool in their investigative workflows.

Application Note 1: Signaling Networks

Background and Biological Significance

Cellular signaling networks, such as the Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF)-dependent Akt pathway in the PC12 cell line, represent a fundamental class of systems biological models where parameter estimation plays a crucial role in elucidating signal transduction mechanisms [21]. These ODE-based models typically describe the temporal dynamics of protein-protein interactions, post-translational modifications, and feedback regulations that govern cellular decisions like proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. The accurate calibration of these models against experimental data enables researchers to identify key regulatory nodes, predict system responses to novel perturbations, and identify potential therapeutic targets for disease intervention.

Protocol: Parameter Estimation for Signaling Pathways

The protocol for estimating parameters in signaling network models follows a systematic workflow encompassing model definition, data integration, identifiability analysis, optimization, and uncertainty quantification [21] [10].

Step 1: Model and Data Preparation Define the ODE system representing the signaling network topology, specifying state variables (protein concentrations), parameters (kinetic rates), and observables (measured signals). Format experimental data—typically time-course measurements of phosphorylated proteins—according to PEtab (Parameter Estimation tabular) format for seamless integration [21].

Step 2: Structural Identifiability Analysis Perform structural identifiability analysis using tools like STRIKE-GOLDD to determine if perfect, noise-free data would theoretically allow unique estimation of all parameters [21]. Address structural non-identifiabilities by modifying model structure or fixing parameter values when supported by prior knowledge.

Step 3: Parameter Estimation via Optimization Execute numerical optimization using either stochastic or deterministic algorithms available in Data2Dynamics to minimize the discrepancy between model simulations and experimental data [1] [21]. The objective function typically follows a maximum likelihood framework, incorporating appropriate error models for the measurement noise.

Step 4: Uncertainty Quantification Calculate confidence intervals for parameter estimates using profile likelihood or Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods [21] [10]. This step assesses the practical identifiability of parameters given the available data and its noise characteristics.

Step 5: Model Validation and Prediction Validate the calibrated model using data not included in the estimation process and derive predictions for untested experimental conditions [10]. Utilize the model to design informative new experiments that would optimally reduce parameter uncertainties.

Table 1: Representative parameters from EGF/Akt signaling pathway model

| Parameter | Description | Estimated Value | Units | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k1 | EGF binding rate | 0.05 | nM⁻¹·min⁻¹ | 15 |

| k2 | Phosphorylation rate | 1.2 | min⁻¹ | 22 |

| k3 | Feedback rate | 0.8 | min⁻¹ | 28 |

| Kd | Dissociation constant | 0.1 | nM | 31 |

Table 2: Experimental data requirements for signaling network calibration

| Data Type | Time Points | Conditions | Replicates | Measurement Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phospho-ERK | 0, 2, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60 min | 4 EGF doses | 3 | 10-15% |

| Phospho-Akt | 0, 2, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60 min | 4 EGF doses | 3 | 10-15% |

| Total protein | 0, 60 min | All conditions | 2 | 5-10% |

Visualization of Signaling Pathway and Workflow

Figure 1: EGF/Akt signaling pathway and modeling workflow

Application Note 2: Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics

Background and Biological Significance

Pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) models form the cornerstone of modern drug development, describing the time-course of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion (ADME), and physiological effects [21]. The calibration of these ODE-based models with experimental data enables the prediction of drug behavior in different patient populations, optimization of dosing regimens, and reduction of late-stage drug development failures. Through precise parameter estimation, researchers can quantify inter-individual variability, identify covariates affecting drug exposure and response, and support regulatory decision-making.

Protocol: PK/PD Model Calibration

The protocol for PK/PD model calibration shares the core parameter estimation workflow with signaling networks but incorporates specific considerations for pharmaceutical applications and mixed-effects modeling for population data.

Step 1: Structural Model Selection Choose appropriate model structures for PK (e.g., multi-compartmental models) and PD (e.g., direct effect, indirect response, or transit compartment models) based on compound characteristics and available prior knowledge [21].

Step 2: Error Model Specification Define error models for both the PK and PD components, accounting for proportional, additive, or combined error structures based on assay characteristics and variability patterns in the data [22].

Step 3: Parameter Estimation Execute the parameter estimation using optimization algorithms, with particular attention to parameter identifiability given typically sparse sampling in clinical studies [21]. For population data, implement mixed-effects modeling approaches to estimate both fixed effects (population typical values) and random effects (inter-individual variability).

Step 4: Model Evaluation Perform predictive checks and residual analysis to validate model adequacy, using visual predictive checks and bootstrap methods when appropriate [10].

Step 5: Dosage Regimen Optimization Utilize the calibrated model to simulate various dosing scenarios and identify optimal regimens that maximize therapeutic effect while minimizing adverse events [21].

Table 3: Key PK parameters for a representative small molecule drug

| Parameter | Description | Typical Value | Inter-individual Variability (%) | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL | Clearance | 5.2 | 32.1 | L/h |

| Vc | Central volume | 25.5 | 28.7 | L |

| Ka | Absorption rate | 0.8 | 45.2 | h⁻¹ |

| F | Bioavailability | 0.85 | 15.3 | - |

| t1/2 | Half-life | 6.5 | 25.4 | h |

Table 4: Data requirements for comprehensive PK/PD modeling

| Data Type | Sampling Time Points | Subjects/Conditions | Critical Measurements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma concentrations | Pre-dose, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24 h | 6-12 per group | Cmax, Tmax, AUC |

| Biomarker response | Pre-dose, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 48 h | 6-12 per group | Baseline, Emax, EC50 |

| Clinical endpoint | Daily until study end | All subjects | Primary efficacy endpoint |

Application Note 3: Infectious Disease Modeling

Background and Biological Significance

Mathematical models of infectious disease dynamics serve as powerful tools for understanding transmission mechanisms, predicting outbreak trajectories, and evaluating intervention strategies [23] [24]. These models range from compartmental frameworks (e.g., SIR, SIRS) to complex agent-based simulations, incorporating factors such as population heterogeneity, behavioral feedback, and spatial diffusion. Parameter estimation in these models enables quantification of key epidemiological parameters such as basic reproduction number (R₀), generation intervals, and age-dependent susceptibility, informing public health policies and resource allocation during outbreaks.

Protocol: Disease Model Calibration

The calibration of infectious disease models presents unique challenges due to the complex interplay between transmission dynamics, observation processes, and intervention effects.

Step 1: Model Structure Definition Select an appropriate model structure based on the disease characteristics, including compartmental divisions (e.g., susceptible, exposed, infectious, recovered), population stratification (e.g., by age, risk group, geography), and intervention components [23] [24].

Step 2: Integration of Surveillance Data Compile and format surveillance data, which may include case reports, hospitalization records, serological surveys, and mortality statistics, accounting for under-reporting and surveillance artifacts through appropriate observation models [23].

Step 3: Time-Varying Parameter Estimation Implement estimation procedures for time-varying parameters (e.g., transmission rates affected by interventions or behavior change) using smoothing splines or change-point models [23].

Step 4: Stochastic Model Implementation For outbreaks in small populations or near elimination thresholds, implement stochastic model formulations to account for demographic noise and extinction probabilities [24].

Step 5: Intervention Scenario Analysis Use the calibrated model to simulate the impact of various intervention strategies (e.g., vaccination, social distancing, treatment programs) and quantify their expected effectiveness under different implementation scenarios [23].

Table 5: Key epidemiological parameters for a respiratory infectious disease

| Parameter | Description | Estimated Value | 95% Confidence Interval | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R₀ | Basic reproduction number | 3.2 | [2.8-3.7] | - |

| 1/γ | Infectious period | 5.1 | [4.5-5.8] | days |

| 1/σ | Latent period | 3.2 | [2.8-3.7] | days |

| p | Reporting fraction | 0.45 | [0.38-0.53] | - |

Table 6: Data streams for infectious disease model calibration

| Data Type | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Resolution | Key Parameters Informed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case notifications | Daily or weekly | Regional or national | Transmission rate, reporting rate |

| Hospitalizations | Daily | Healthcare facility | Severity fraction, healthcare demand |

| Serological surveys | Pre- and post-outbreak | Community | Cumulative infection rate |

| Mortality data | Weekly | National | Infection fatality ratio |

Visualization of Disease Modeling Approach

Figure 2: Compartmental disease model structure and calibration workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 7: Essential computational tools for parameter estimation with Data2Dynamics

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in Workflow | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data2Dynamics | MATLAB Environment | Core modeling environment for parameter estimation, uncertainty analysis, and model selection | http://www.data2dynamics.org [2] |

| PEtab | Data Format Standard | Standardized format for encoding models, experimental data, and parameters to enable reproducible modeling | https://github.com/PEtab-dev/PEtab [21] |

| calibr8 | Python Package | Construction of calibration models describing relationship between measurements and underlying quantities | Python Package [22] |

| murefi | Python Package | Framework for building hierarchical models that share parameters across experimental replicates | Python Package [22] |

| AMICI | Tool | Efficient simulation and sensitivity analysis of ODE models | https://github.com/AMICI-dev/AMICI [21] |

| pyPESTO | Tool | Parameter estimation toolbox offering optimization and uncertainty analysis methods | https://github.com/ICB-DCM/pyPESTO [21] |

Experimental Design Considerations

Effective parameter estimation requires carefully designed experiments that generate informative data for model calibration. Key considerations include:

Temporal Sampling Design: Schedule measurements to capture rapid transitions and steady states, with increased sampling density during dynamic phases [10]. For signaling networks, early time points (seconds to minutes) are critical; for PK studies, include rapid sampling post-dose and around expected Tmax.

Perturbation Experiments: Incorporate deliberate system perturbations—such as ligand stimulations, inhibitor treatments, or genetic modifications—to excite system dynamics and improve parameter identifiability [10].

Replication Strategy: Include sufficient biological and technical replicates to characterize experimental noise, with typical recommendations of 3-5 replicates for most assay types [22].

Error Model Characterization: Dedicate experimental effort to characterize measurement error structures through repeated measurements of standards and controls, enabling appropriate weighting of data during parameter estimation [22].

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Structural and Practical Identifiability

A critical foundation for reliable parameter estimation is assessing whether available data sufficiently constrain parameter values. Structural identifiability analysis examines whether parameters could be uniquely determined from perfect, continuous, noise-free data, addressing issues arising from model structure such as parameter symmetries or redundancies [21]. Practical identifiability analysis evaluates whether the actual available data—with its finite sampling and measurement noise—allows for precise parameter estimation, typically assessed through profile likelihood or MCMC methods [21] [19].

Recent methodological advances include active learning approaches like E-ALPIPE, which sequentially recommend new data collection points most likely to establish practical identifiability, substantially reducing the number of observations required while producing accurate parameter estimates [19]. This approach is particularly valuable in resource-limited experimental settings where efficient data collection is essential.

Uncertainty Analysis and Model Prediction

Beyond point estimates of parameters, comprehensive uncertainty analysis is essential for credible model-based predictions. Data2Dynamics implements both frequentist (profile likelihood) and Bayesian (MCMC sampling) approaches for uncertainty quantification [1] [10]. Profile likelihood provides confidence intervals with clear statistical interpretation, while MCMC sampling generates full posterior distributions that naturally propagate uncertainty to model predictions [10].

For prediction tasks, calculating prediction uncertainties that incorporate both parameter uncertainties and observational noise provides a more complete assessment of the reliability of model extrapolations [10]. This is particularly crucial when models inform decision-making in drug development or public health policy, where understanding the range of possible outcomes is as important as point predictions.

The Data2Dynamics modeling environment provides researchers with a comprehensive, robust toolkit for parameter estimation across the core application domains of systems biology. Through structured protocols addressing signaling networks, pharmacokinetics, and disease modeling, researchers can implement statistically rigorous approaches to model calibration, uncertainty quantification, and experimental design. The integration of advanced methodologies—including identifiability analysis, active learning for optimal experimental design, and comprehensive uncertainty propagation—ensures that models parameterized with Data2Dynamics yield biologically meaningful, predictive insights that advance scientific understanding and support translational applications in drug development and public health.

Practical Implementation: Parameter Estimation Workflows and Optimization Techniques in D2D

In the field of systems biology and quantitative dynamical modeling, parameter estimation represents a critical step in developing models that accurately reflect biological reality. The process involves determining the unknown parameters of a model such that its predictions align closely with experimental observations. This alignment is quantified through an objective function, which measures the discrepancy between model predictions and empirical data. Within the context of the Data2Dynamics modeling environment [2] [7], a sophisticated software package for MATLAB tailored to dynamical systems in systems biology, the choice and formulation of this objective function are paramount. The software facilitates the construction of dynamical models for biochemical reaction networks and implements reliable parameter estimation techniques using numerical optimization methods.

Two fundamental approaches for defining the objective function in parameter estimation are the Weighted Residual Sum of Squares (RSS) and Likelihood Formulation. The weighted RSS provides a framework to account for heterogeneous measurement variances across data points, while the likelihood approach offers a statistical foundation based on probability theory. Understanding the mathematical foundations, practical implementations, and interrelationships of these methods is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in quantitative modeling of biological processes. This document outlines the formal definitions, computational procedures, and practical protocols for implementing these objective functions within dynamical modeling frameworks, with specific reference to applications in drug development and systems pharmacology.

Theoretical Foundations

Residual Sum of Squares (RSS)

The Residual Sum of Squares (RSS) serves as a fundamental measure of model fit in regression analysis. It quantifies the total squared discrepancy between observed data points and the values predicted by the model [25]. Mathematically, for a set of n observations, the RSS is defined as:

[ \text{RSS} = \sum{i=1}^{n} (yi - \hat{y}_i)^2 ]

where (yi) represents the observed value and (\hat{y}i) represents the corresponding model prediction [25]. In essence, RSS is the sum of the squared residuals, where each residual is the difference between an observed value and its fitted value. Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression minimizes this RSS, thereby producing the best possible fit for a given model [25].

The interpretation of RSS is seemingly straightforward: a smaller RSS indicates a closer fit of the model to the data, with a value of zero representing a perfect fit without any error [25]. However, a single RSS value in isolation is challenging to interpret meaningfully due to its dependence on the data's scale and the number of observations [25]. Consequently, RSS is most valuable when comparing competing models for the same dataset, rather than as an absolute measure of goodness-of-fit.

Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE)

Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) is a powerful and general method for estimating the parameters of an assumed probability distribution, given some observed data [26] [27]. The core concept involves choosing parameter values that maximize the likelihood function, which represents the probability of observing the given data as a function of the model parameters [26]. Intuitively, MLE identifies the parameter values under which the observed data would be most probable.

Formally, given a parameter vector (\theta = [\theta1, \theta2, \ldots, \thetak]^T) and observed data vector (\mathbf{y} = (y1, y2, \ldots, yn)), the likelihood function (L(\theta; \mathbf{y})) is defined as the joint probability (or probability density) of the observations given the parameters [26] [27]. For computational convenience, we often work with the log-likelihood function:

[ \ell(\theta; \mathbf{y}) = \ln L(\theta; \mathbf{y}) ]

The maximum likelihood estimate (\hat{\theta}) is then the value that maximizes the likelihood function:

[ \hat{\theta} = \underset{\theta \in \Theta}{\operatorname{arg\,max}} \, L(\theta; \mathbf{y}) = \underset{\theta \in \Theta}{\operatorname{arg\,max}} \, \ell(\theta; \mathbf{y}) ]

In practice, finding the maximum often involves solving the likelihood equations obtained by setting the first partial derivatives of the log-likelihood with respect to each parameter to zero [26] [28]. MLE possesses several desirable statistical properties, including consistency (convergence to the true parameter value as sample size increases) and efficiency (achieving the smallest possible variance among unbiased estimators) in large samples [26].

Table 1: Key Properties of RSS and MLE Approaches

| Feature | Residual Sum of Squares (RSS) | Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophical Basis | Geometric distance minimization | Probability maximization |

| Core Objective | Minimize sum of squared errors | Maximize likelihood of observed data |

| Error Handling | Implicitly assumes homoscedasticity (unless weighted) | Explicitly models error structure |

| Interpretation | Measure of model fit (smaller is better) | Statistical evidence for parameters (larger is better) |

| Implementation | Often simpler computationally | Can be computationally intensive for complex models |

| Optimality | Best linear unbiased estimator (under Gauss-Markov assumptions) | Consistent, efficient, asymptotically normal |

Weighted Residual Sum of Squares

Formulation and Motivation

The standard RSS approach assumes constant variance in the errors across all observations, a condition known as homoscedasticity. However, in many experimental contexts, particularly in biological and pharmacological research, this assumption is violated, and the errors exhibit heteroscedasticity—their variances differ across observations [29] [30]. In such cases, Weighted Least Squares (WLS) provides a generalization of ordinary least squares that incorporates knowledge of this unequal variance into the regression [29].

The weighted sum of squares is formulated as:

[ S(\beta) = \sum{i=1}^{n} wi ri^2 = \sum{i=1}^{n} wi (yi - f(x_i, \beta))^2 ]

where (ri) is the residual for the i-th observation, and (wi) is the weight assigned to that observation [29]. The weights are typically chosen to be inversely proportional to the variance of the observations:

[ wi = \frac{1}{\sigmai^2} ]

This weighting scheme ensures that observations with smaller variance (and hence greater reliability) contribute more heavily to the parameter estimation than observations with larger variance [29] [30]. The weighted least squares estimate is then obtained by minimizing the weighted sum of squares:

[ \hat{\beta}{WLS} = \arg\min{\beta} \sum{i=1}^{n} wi (yi - f(xi, \beta))^2 = (X^T W X)^{-1} X^T W Y ]

where (W) is a diagonal matrix containing the weights (w_i) [29] [30].

Determining Weights in Practice

In theoretical applications, the true variances (\sigma_i^2) might be known, but in practice, they often need to be estimated from the data [29] [30]. Several approaches exist for determining appropriate weights:

Known Variances: In some cases, variances are known from external sources or experimental design. For example, if the i-th response is an average of (ni) observations, then (\text{Var}(yi) = \sigma^2/ni) and the weight should be (wi = n_i) [30].

Residual Analysis: When variances are unknown, an ordinary least squares regression can be performed first. The resulting residuals can then be analyzed to identify patterns of heteroscedasticity [30]:

- If a residual plot against a predictor shows a megaphone shape, regress the absolute residuals against that predictor and use the fitted values as estimates of (\sigma_i).

- Similarly, if a residual plot against fitted values shows a megaphone shape, regress the absolute residuals against the fitted values.

Iterative Methods: The weighted least squares procedure can be iterated until the estimated coefficients stabilize, an approach known as iteratively reweighted least squares [30].

Table 2: Common Weighting Schemes in Practical Applications

| Scenario | Variance Structure | Recommended Weight | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Averaged Measurements | (\text{Var}(yi) = \sigma^2/ni) | (wi = ni) | Experimental replicates with different sample sizes |

| Proportional to Predictor | (\text{Var}(yi) = xi\sigma^2) | (wi = 1/xi) | Variance increases with measurement magnitude |

| Known Standard Deviations | (\text{Var}(yi) = \text{SD}i^2) | (wi = 1/\text{SD}i^2) | External estimates of measurement precision available |

| Theoretical Model | Specific variance model | Model-based weights | When error generation process is understood |

Likelihood Formulation

Principles and Calculation

The likelihood approach to parameter estimation is grounded in probability theory. For a set of independent observations (y1, y2, \ldots, y_n), the likelihood function is defined as the joint probability of the observations given the parameters [27]. For discrete random variables, this is the joint probability mass function, while for continuous random variables, it is the joint probability density function.

The formal definition depends on the nature of the variables:

- For discrete data: (L(\theta; x1, x2, \ldots, xn) = P(X1 = x1, X2 = x2, \ldots, Xn = x_n; \theta))

- For continuous data: (L(\theta; x1, x2, \ldots, xn) = f{X1, X2, \ldots, Xn}(x1, x2, \ldots, xn; \theta))

When observations are independent and identically distributed, the likelihood simplifies to the product of individual probabilities or densities [27]:

[ L(\theta; x1, x2, \ldots, xn) = \prod{i=1}^n f(x_i; \theta) ]

The log-likelihood is then:

[ \ell(\theta; x1, x2, \ldots, xn) = \sum{i=1}^n \ln f(x_i; \theta) ]

As a concrete example, for a binomial distribution with success probability (\theta), the log-likelihood for x successes in n trials is [28]:

[ \ell(\theta) = x \ln(\theta) + (n - x) \ln(1 - \theta) + \text{constant} ]

Differentiating with respect to (\theta) and setting to zero yields the maximum likelihood estimate (\hat{\theta} = x/n) [28].

Error Estimation for MLE

For smooth log-likelihood functions, the uncertainty in the parameter estimates can be assessed using the second derivative of the log-likelihood function [28]. Specifically, the variance of the MLE can be approximated by the negative inverse of the second derivative of the log-likelihood evaluated at the maximum:

[ \text{Var}(\hat{\theta}) \approx -\left( \frac{\partial^2 \ell}{\partial \theta^2} \bigg\rvert_{\hat{\theta}} \right)^{-1} ]

This approximation becomes exact when the likelihood function is normally distributed around the maximum [28]. The resulting standard error is:

[ \text{SE}(\hat{\theta}) = \sqrt{-\left( \frac{\partial^2 \ell}{\partial \theta^2} \bigg\rvert_{\hat{\theta}} \right)^{-1}} ]

This approach to error estimation facilitates the construction of confidence intervals around the parameter estimates, which is essential for assessing the reliability of the estimated parameters in practical applications.

Connection Between RSS and Likelihood Approaches

Equivalence Under Normal Distribution Assumptions

A fundamental relationship exists between the RSS and MLE approaches when the errors are assumed to be independent and normally distributed with constant variance. For a normal distribution with mean (f(x_i, \beta)) and variance (\sigma^2), the log-likelihood function is:

[ \ell(\beta, \sigma^2; y) = -\frac{n}{2} \ln(2\pi) - \frac{n}{2} \ln(\sigma^2) - \frac{1}{2\sigma^2} \sum{i=1}^n (yi - f(x_i, \beta))^2 ]

Maximizing this log-likelihood with respect to (\beta) is equivalent to minimizing the sum of squared residuals (\sum{i=1}^n (yi - f(x_i, \beta))^2), as the other terms are constant with respect to (\beta) [28]. This establishes the equivalence between least squares and maximum likelihood estimation under the assumption of normally distributed errors with constant variance.

When the variances are not equal but known up to a proportionality constant, the connection extends to weighted least squares. For independent normal errors with variances (\sigmai^2 = \sigma^2 / wi), the log-likelihood becomes:

[ \ell(\beta, \sigma^2; y) = \text{constant} - \frac{1}{2\sigma^2} \sum{i=1}^n wi (yi - f(xi, \beta))^2 ]

Maximizing this likelihood is equivalent to minimizing the weighted sum of squares [28]. This relationship provides a statistical justification for the weighted least squares approach, demonstrating that it produces maximum likelihood estimates when errors are normally distributed with known relative variances.

Advantages and Limitations of Each Approach

Both the weighted RSS and likelihood approaches offer distinct advantages in different modeling contexts:

Weighted RSS Advantages:

- Computational simplicity and numerical stability

- Intuitive geometric interpretation

- Direct extension from ordinary least squares

- Generally robust for well-behaved systems

Weighted RSS Limitations:

- Optimality depends on correct specification of weights

- Limited theoretical justification when errors are non-normal

- Does not automatically provide uncertainty estimates for parameters

- Susceptible to bias from influential outliers [25]

Likelihood Approach Advantages: