Markov Chain Monte Carlo Methods for Stochastic Models: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development.

Markov Chain Monte Carlo Methods for Stochastic Models: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development. It covers the foundational theory of MCMC and its necessity for analyzing complex stochastic models, details key algorithms like Metropolis-Hastings and Gibbs sampling, and offers practical solutions for common implementation challenges such as convergence and efficiency. Furthermore, it outlines rigorous diagnostic and validation techniques to ensure result reliability and presents a comparative analysis of modern MCMC algorithms, empowering readers to effectively apply these powerful computational techniques to problems in quantitative biology and clinical research.

The What and Why of MCMC: Foundations for Stochastic Modeling

Theoretical Foundations of Bayesian Inference

Bayesian inference provides a probabilistic framework for updating beliefs about model parameters (θ) based on observed data (D) and prior knowledge [1]. This approach is fundamentally governed by Bayes' theorem, which computes the posterior distribution through a combination of prior knowledge and observed evidence. The theorem is expressed as:

[p(θ|D) = \frac{p(D|θ) × p(θ)}{p(D)}]

where (p(θ|D)) represents the posterior distribution of parameters given the data, (p(D|θ)) is the likelihood function indicating the probability of the data given the parameters, (p(θ)) is the prior distribution encoding existing knowledge about the parameters before observing data, and (p(D)) is the model evidence (also called marginal likelihood) serving as a normalizing constant [1].

This framework offers significant advantages for complex stochastic models, including the ability to quantify uncertainty through complete posterior distributions rather than point estimates, naturally incorporate prior knowledge from domain experts or previous studies, perform model comparison through Bayes factors computed from marginal likelihoods, and make predictions by integrating over all possible parameter values weighted by their posterior probabilities [1].

The choice of prior distribution depends on the available domain knowledge. Informative priors incorporate specific, well-justified information about parameter values, while weakly informative priors regularize estimation without strongly influencing results. Non-informative priors attempt to minimize the impact of prior information, though this concept requires careful consideration [2].

Table 1: Components of Bayes' Theorem and Their Interpretations

| Component | Mathematical Notation | Interpretation | Role in Inference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior Distribution | (p(θ)) | Belief about θ before observing data | Encodes existing knowledge or constraints |

| Likelihood Function | (p(D|θ)) | Probability of data given specific parameters | Connects parameters to observed data |

| Posterior Distribution | (p(θ|D)) | Updated belief about θ after observing data | Primary output for inference and decision |

| Model Evidence | (p(D)) | Probability of data under the model | Enables model comparison and selection |

The Sampling Problem in Bayesian Analysis

For most practical Bayesian modeling scenarios, the posterior distribution (p(θ|D)) cannot be derived analytically due to intractable high-dimensional integrals in the normalization constant [1]. This fundamental challenge, known as the sampling problem, necessitates computational methods to approximate posterior distributions.

The sampling problem manifests differently across model classes. For white-box models with physics-based equations, parameters often have direct physical interpretations but yield complex posterior surfaces [1]. Black-box models like neural networks possess universal approximation properties but contain parameters without physical meaning, making prior specification challenging [1] [2]. Grey-box models combine physical principles with flexible components, often leading to high-dimensional parameter spaces with both interpretable and non-interpretable parameters [1].

The core difficulty emerges from the need to compute expectations of functions (h(θ)) under the posterior distribution:

[E[h(θ)|D] = \frac{\int h(θ) p(D|θ) p(θ) dθ}{\int p(D|θ) p(θ) dθ}]

These integrals become analytically intractable for complex models with high-dimensional parameter spaces, necessitating approximate computational methods [3].

Markov Chain Monte Carlo as a Solution

Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods solve the sampling problem by constructing a Markov chain that explores the parameter space such that its stationary distribution equals the desired posterior distribution [3]. After a sufficient number of iterations (burn-in period), samples from the chain can be treated as correlated draws from the target posterior.

The theoretical foundation of MCMC requires establishing several key properties. Irreducibility ensures all relevant regions of the parameter space can be reached from any starting point, while aperiodicity guarantees the chain doesn't cycle through states periodically [3]. Harris recurrence provides the theoretical basis for convergence to the unique stationary distribution, and the ergodic theorem justifies using sample averages to approximate posterior expectations [3].

Table 2: Major MCMC Algorithm Classes and Their Characteristics

| Algorithm | Key Mechanism | Best-Suited Problems | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metropolis-Hastings | Proposed moves accepted/rejected via probability ratio | General-purpose sampling; adaptable to various models | Proposal distribution tuning critical for efficiency |

| Gibbs Sampling | Iterative sampling from full conditional distributions | Models with tractable conditional distributions | Highly efficient when conditionals are standard distributions |

| Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) | Uses gradient information for Hamiltonian dynamics | High-dimensional, complex posterior geometries | Requires differentiable probability model; sensitive to step size parameters |

| No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS) | Extends HMC with adaptive path length | Complex models without manual tuning | Automatically determines trajectory length; computationally intensive |

| Reversible Jump MCMC | Allows dimension-changing moves | Variable-dimension model selection problems | Complex implementation; requires careful proposal design |

Practical Implementation Protocols

Protocol: MCMC for Pharmacokinetic Input Estimation

Application Context: This protocol addresses the challenge of estimating unknown input functions in pharmacological systems, such as drug absorption rates, when only output measurements (e.g., plasma concentrations) are available [4].

Experimental Workflow:

Problem Specification: Define the differential equation system representing drug kinetics: [ \frac{dx(t)}{dt} = f(t, x(t), u(t)) ] where (x(t)) represents system states (e.g., drug concentrations in compartments), and (u(t)) is the unknown input function to be estimated [4].

Prior Selection: For input functions, common choices include:

- Gaussian process priors with penalized first or second derivatives: [ \ln p(u(t)) ∝ -τ\int_a^b \left(\frac{d^ju}{dt^j}\right)^2 dt ]

- Entropy-based priors for discrete-time inputs: [ \ln p(u(t)) ∝ -τ\sum{k=0}^{Ne-1} uk \ln\left(\frac{uk}{mk}\right) ] where (mk) represents baseline values [4].

Functional Representation: Represent the input function using basis expansions: [ u(t) = \sum{i=0}^{NB-1} θi Bi(t) ] where (B_i(t)) are chosen basis functions (e.g., piecewise constant, B-splines, or Karhunen-Loève basis) [4].

Algorithm Selection: Choose between:

- Maximum a Posteriori (MAP) estimation using optimal control techniques for point estimates

- Full Bayesian inference using MCMC for complete posterior distributions [4]

Convergence Assessment: Run multiple chains from dispersed starting points and compute Gelman-Rubin statistics to ensure (\hat{R} < 1.05) for all parameters of interest.

Protocol: Bayesian System Identification for Nonlinear Dynamics

Application Context: Identify nonlinear dynamical systems from experimental data, commonly encountered in structural dynamics, mechanical engineering, and biological systems [1].

Experimental Workflow:

Model Structure Selection: Choose between white-box, black-box, and grey-box modeling approaches based on available physical knowledge and system complexity [1].

Prior Specification: Place appropriate priors on model parameters:

- For physically meaningful parameters, use informative priors based on domain knowledge

- For nuisance parameters, employ weakly informative regularizing priors

- For neural network components, consider layer-scaled Gaussian priors rather than isotropic priors for improved sampling efficiency [2]

Hierarchical Model Construction: For population studies, implement hierarchical structure: [ \begin{aligned} yi &\sim p(yi|θi) \quad \text{(Individual level)} \ θi &\sim p(θ_i|φ) \quad \text{(Population level)} \ φ &\sim p(φ) \quad \text{(Hyperpriors)} \end{aligned} ]

MCMC Algorithm Selection: Based on problem dimensionality and posterior geometry:

- Gibbs sampling for conditionally conjugate models

- Hamiltonian Monte Carlo for complex, high-dimensional posteriors

- Adaptive MCMC during initial exploration phases

Model Assessment: Compute posterior predictive distributions and compare with empirical data to assess model adequacy.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for MCMC Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Functionality | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic Programming Languages | Stan, PyMC3, Turing.jl | High-level model specification and automatic inference | Rapid prototyping; complex model development |

| Statistical Software | R, Python with NumPy/SciPy | Data preprocessing and posterior analysis | Data preparation; result visualization |

| Specialized MCMC Algorithms | NUTS, Particle Gibbs, Slice Sampling | Advanced sampling for challenging posterior distributions | High-dimensional models; multi-modal distributions |

| Convergence Diagnostics | Gelman-Rubin statistic, trace plots, autocorrelation | Assess MCMC convergence and sampling quality | All MCMC applications |

| High-Performance Computing | Parallel chains, GPU acceleration | Reduce computational time for complex models | Large datasets; computationally intensive models |

Application Case Studies

Drug Discovery Using Input Estimation

In pharmacological applications, MCMC enables estimation of unknown input functions such as drug absorption rates from output measurements. A study evaluating eflornithine pharmacokinetics in rats demonstrated how Bayesian input estimation recovers absorption profiles and bioavailability using sparse concentration measurements [4]. The MCMC approach provided full posterior distributions for the input function, enabling quantification of uncertainty in absorption rate estimates—critical for dosage decisions in drug development.

The implementation utilized a hierarchical model structure with penalized smoothness priors on the input function, represented via B-spline basis expansions. Hamiltonian Monte Carlo sampling provided efficient exploration of the high-dimensional parameter space, with computational advantages over traditional optimal control methods when uncertainty quantification was essential [4].

Phase-Type Aging Model Estimation

The Phase-Type Aging Model (PTAM) represents a class of Coxian-type Markovian models for quantifying aging processes, but presents significant estimability challenges due to flat likelihood surfaces [5]. Traditional maximum likelihood estimation fails with profile likelihood functions that are flat and analytically intractable.

A specialized MCMC approach addressed these challenges through a two-level sampling scheme. The outer level employs data augmentation via Exact Conditional Sampling, while the inner level implements Gibbs sampling with rejection sampling on a logarithmic scale [5]. This approach successfully handled left-truncated data common in real-world studies where individuals enter at different physiological ages, demonstrating improved parameter estimability through incorporation of sound prior information.

Bayesian Neural Networks with Scaled Priors

Recent advances in Bayesian neural networks demonstrate the critical importance of prior specification for MCMC sampling efficiency. Research comparing isotropic Gaussian priors with layer-wise scaled Gaussian priors found significant improvements in convergence statistics and sampling efficiency when using properly scaled priors [2].

In experiments across eight classification datasets, MCMC sampling with layer-scaled priors demonstrated faster convergence measured by potential scale reduction factors and more effective sample sizes per computation time. This approach also mitigated the "cold posterior effect" where posterior scaling artificially improves prediction, suggesting proper prior specification addresses fundamental model misspecification issues [2].

The implementation utilized the No-U-Turn Sampler with 8 chains run for 200 Monte Carlo steps after 1000-step burn-in periods, with thinning to retain every fourth sample. This protocol generated ensembles of 400 neural networks for robust uncertainty quantification.

Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods represent a cornerstone of computational statistics, enabling researchers to draw samples from complex probability distributions that are analytically intractable. These methods are particularly indispensable in Bayesian statistical analysis, where they facilitate the estimation of posterior distributions for model parameters in complex stochastic models [6]. The power of MCMC lies in its foundation on three interconnected mathematical pillars: Markov chains, stationary distributions, and ergodicity. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these core concepts is crucial for proper implementation of MCMC algorithms in areas such as pharmacokinetic modeling, dose-response analysis, and molecular dynamics simulation.

The fundamental principle underlying MCMC is the construction of a Markov chain that eventually converges to a target distribution, from which samples can be drawn. Once the Markov chain has approximately reached this target distribution, its states can be used as approximate random samples for constructing estimates of unknown quantities of interest [6]. This process elegantly combines the theory of Markov processes with Monte Carlo simulation techniques to solve challenging integration and optimization problems common in stochastic models research.

Core Theoretical Framework

Markov Chains

A Markov chain is a discrete-time stochastic process (X0, X1, \ldots) that possesses the Markov property, meaning that the future state depends only on the present state, not on the full history of previous states [6]. Formally, this is expressed as:

[ P(X{t+1} = x{t+1} | Xt = xt, X{t-1} = x{t-1}, \ldots, X0 = x0) = P(X{t+1} = x{t+1} | Xt = xt) ]

For a Markov chain with a countable state space, the transition probabilities between states can be represented by a matrix (P), where (P(i,j) = P(X{t+1} = j | Xt = i)) [7]. In the context of MCMC for general state spaces, these concepts extend to transition kernels, which describe the probability of moving from one state to another.

Table 1: Key Properties of Markov Chains in MCMC Context

| Property | Mathematical Definition | Role in MCMC |

|---|---|---|

| Irreducibility | For all (x, y \in \mathbb{X}), there exists (s) such that (P^s(x, y) > 0) [3] | Ensces the chain can reach all parts of the state space |

| Aperiodicity | Greatest common divisor of ({n \geq 1: P^n(x,x) > 0}) is 1 for all (x) [3] | Prevents cyclic behavior that impedes convergence |

| Recurrence | (Px(\taux < \infty) = 1) and (\mathbb{E}x[\taux] < \infty) for all (x) [3] | Guarantees the chain returns to each state infinitely often |

Stationary Distributions

A stationary distribution (\pi) for a Markov chain is a probability distribution that remains unchanged as the chain evolves. Formally, (\pi) is stationary if:

[ \pi = \pi P ]

In the context of MCMC, the stationary distribution is designed to match the target distribution from which we wish to sample [7]. This is a fundamental aspect of MCMC algorithms - we construct a Markov chain whose stationary distribution equals our target probability distribution of interest. For a positive recurrent Markov chain, the stationary distribution exists, is unique, and can be approximated by running the chain for a sufficiently long time [7].

The existence of a stationary distribution is crucial for MCMC methods because it ensures that, regardless of the initial state, the distribution of the Markov chain will converge to this target distribution. This property allows researchers to use the states of the chain as approximate samples from the desired distribution after an appropriate burn-in period.

Ergodicity

Ergodicity is the property that ensures a Markov chain not only has a stationary distribution but also converges to it from any starting point, and that time averages converge to spatial averages [7]. Formally, for an ergodic Markov chain with stationary distribution (\pi), the following holds almost surely for any function (g) with (\mathbb{E}_{\pi}[|g|] < \infty):

[ \lim{t \to \infty} \frac{1}{t} \sum{i=0}^{t-1} g(Xi) = \sum{x \in \mathbb{X}} g(x) \pi(x) ]

A sufficient condition for ergodicity in countable Markov chains is that the chain is irreducible, aperiodic, and positive recurrent [7]. In practice, ergodicity ensures that our MCMC estimates converge to the correct values given sufficient computation time, making it a fundamental requirement for practical MCMC applications.

Table 2: Conditions for Ergodicity in Countable Markov Chains

| Condition | Description | Practical Verification in MCMC |

|---|---|---|

| Irreducibility | Possible to reach any state from any other state in finite steps [7] | Ensure proposal distribution has support covering entire target distribution |

| Aperiodicity | Chain does not exhibit periodic behavior [7] | Include possibility of remaining in current state (e.g., through rejection) |

| Positive Recurrence | Expected return time to each state is finite [3] | Guaranteed if stationary distribution exists for irreducible chain |

Relationship Between Concepts and MCMC Convergence

The interrelationship between Markov chains, stationary distributions, and ergodicity forms the theoretical foundation for MCMC methods. The convergence of MCMC algorithms relies on the careful construction of a Markov chain that satisfies all the conditions for ergodicity with the target distribution as its stationary distribution.

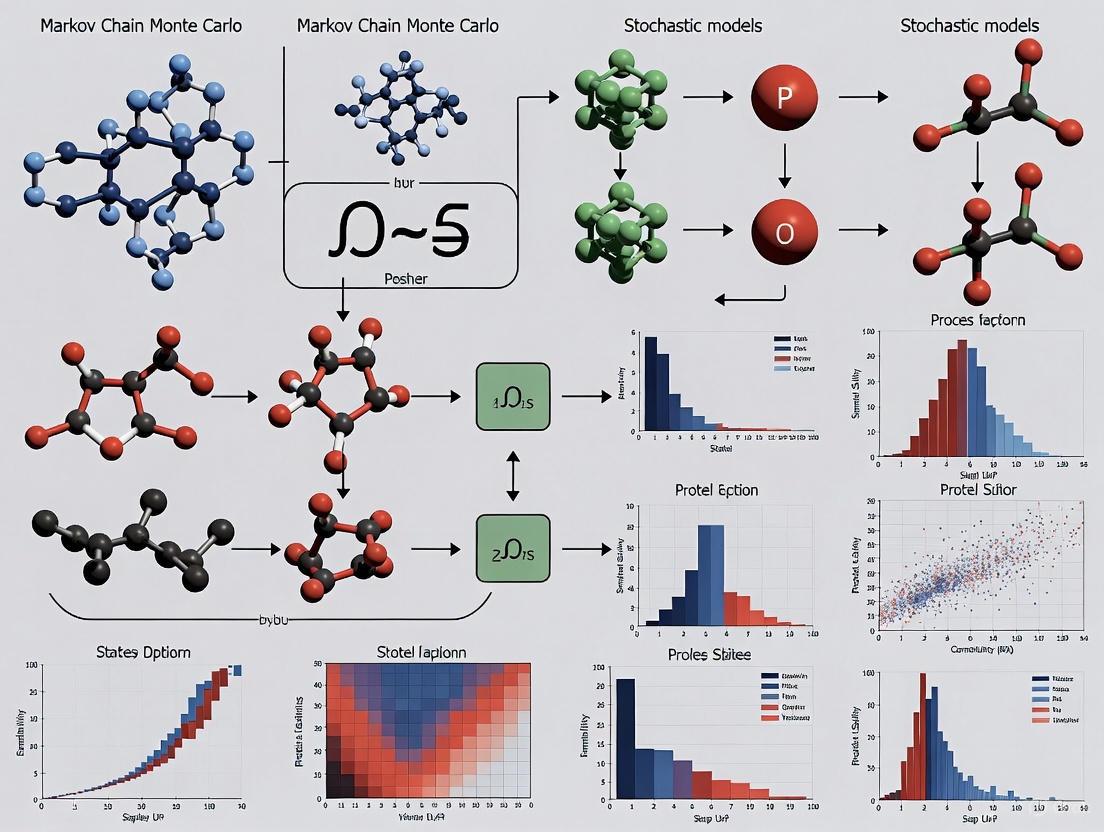

The following diagram illustrates the logical dependencies between these core concepts and their role in ensuring successful MCMC estimation:

Logical Dependencies for MCMC

This relationship shows that properly designed Markov chains converge to stationary distributions, and under ergodic conditions, enable consistent parameter estimation through MCMC. For practitioners, this means that verifying these properties (either theoretically or diagnostically) is essential for validating MCMC implementations in research applications.

Experimental Protocols for MCMC Implementation

Protocol 1: Establishing Stationarity and Burn-in Determination

Purpose: To determine the burn-in period required for the Markov chain to converge to its stationary distribution before sampling begins.

Materials:

- Target probability distribution (\pi(x))

- Initial state (X_0)

- Transition kernel (P(x, y)) satisfying detailed balance with respect to (\pi)

Procedure:

- Initialize the Markov chain at (X_0)

- For (t = 1) to (T{max}): a. Generate (Xt) from (P(X{t-1}, \cdot)) b. Record the value of (Xt)

- Apply convergence diagnostics to the sequence ({X_t})

- Determine the burn-in time (B) where the chain appears to have reached stationarity

- Discard samples (X0, X1, \ldots, X_{B-1})

Convergence Diagnostics:

- Gelman-Rubin statistic (requires multiple chains) [6]

- Heidelberger-Welch stationarity test [6]

- Geweke's diagnostic test [6]

- Visual inspection of trace plots

Expected Outcomes:

- Identification of appropriate burn-in period (B)

- Statistical evidence that ({X_t}) for (t \geq B) follows the target distribution (\pi)

Protocol 2: Ergodicity Assessment and Sampling Efficiency

Purpose: To verify ergodic properties and determine sampling intervals for approximately independent samples.

Materials:

- Markov chain after burn-in ({XB, X{B+1}, \ldots, X{T{max}})

- Functions of interest (h(x)) for estimation

Procedure:

- Calculate the empirical average of (h): (\hat{\mu} = \frac{1}{T{max}-B+1} \sum{t=B}^{T{max}} h(Xt))

- Compute the empirical autocorrelation function (\hat{\rho}(k)) for lag (k)

- Determine the integrated autocorrelation time (\tau{int} = 1 + 2 \sum{k=1}^{\infty} \hat{\rho}(k))

- Calculate the effective sample size: (ESS = \frac{T{max}-B+1}{\tau{int}})

- If ESS is too small, determine a thinning interval (K) and retain every (K)-th sample

Interpretation:

- High autocorrelation indicates slow mixing and poor ergodicity

- Low ESS suggests need for longer runs or improved algorithm

- Thinning reduces storage but may not improve estimation efficiency

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for MCMC Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Kernels | Defines Markov chain movement (e.g., Random Walk, Gibbs) [6] | Core mechanism for state transitions in all MCMC algorithms |

| Target Distribution π | The probability distribution to be sampled [6] [7] | Represents posterior distribution in Bayesian analysis |

| Proposal Distribution | Generates candidate states in Metropolis-Hastings [6] | Controls exploration efficiency of the state space |

| Convergence Diagnostics | Assess stationarity and mixing (e.g., Gelman-Rubin) [6] | Validates algorithm implementation and results reliability |

| Autocorrelation Analysis | Measures dependency between successive samples [6] | Determines effective sample size and thinning requirements |

MCMC Assessment Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for implementing and validating MCMC methods in research practice, incorporating both theoretical guarantees and practical diagnostics:

MCMC Implementation Workflow

This workflow highlights the essential steps in proper MCMC implementation, emphasizing the connection between theoretical properties and practical assessment. For researchers in drug development, this systematic approach ensures reliable results in critical applications such as clinical trial simulations and pharmacokinetic modeling.

The Monte Carlo (MC) principle represents a foundational concept in computational statistics, providing a powerful framework for solving complex problems through random sampling. This approach transforms deterministic challenges, such as calculating high-dimensional integrals, into stochastic problems amenable to statistical solutions. In the context of Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods for stochastic models, this principle evolves from simple random sampling to sophisticated algorithms that enable researchers to sample from intricate probability distributions encountered in real-world scientific problems [8] [9].

The significance of Monte Carlo methods extends across multiple disciplines, including computational statistics, Bayesian inference, and drug development, where they facilitate parameter estimation, uncertainty quantification, and predictive modeling. For researchers and drug development professionals, these methods offer a mathematically rigorous approach to handling complex models where traditional analytical methods fail [9]. The evolution from basic Monte Carlo integration to MCMC represents a paradigm shift in how scientists approach stochastic models, enabling the analysis of previously intractable problems in areas from pharmacokinetics to dose-response modeling and molecular dynamics.

Theoretical Foundations

The Monte Carlo Principle in Integration

At its core, the Monte Carlo principle for integration leverages the law of large numbers to approximate expectations and integrals through empirical averages. Given a random variable ( X ) with probability density function ( p(x) ), the expectation of a function ( f(X) ) can be approximated as [9]:

[ E[f(X)] = \int f(x)p(x)dx \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} f(xi) ]

where ( x_i ) are independent samples drawn from ( p(x) ). This stochastic integration approach proves particularly valuable in high-dimensional spaces where traditional numerical methods suffer from the "curse of dimensionality."

The variance of the Monte Carlo estimator decreases as ( O(1/\sqrt{N}) ), independent of dimensionality, making it exceptionally suited for complex models in drug development and molecular simulation. This fundamental property explains the widespread adoption of Monte Carlo methods across scientific disciplines where high-dimensional integration is required [9].

From Simple Sampling to Markov Chains

While classical Monte Carlo methods rely on independent sampling from target distributions, this approach becomes computationally infeasible for complex, high-dimensional distributions encountered in practical research settings. Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods overcome this limitation by generating dependent samples through a constructed Markov chain that eventually converges to the target distribution as its stationary distribution [3] [8].

The theoretical justification for MCMC lies in the ergodic theorem, which establishes that under certain regularity conditions, sample averages converge to expected values even with dependent samples [3]:

[ \lim{n\to\infty} \frac{1}{n} \sum{i=1}^{n} h(X_i) = \int h(x) \pi(dx) ]

where ( \pi ) is the stationary distribution of the Markov chain ( (X_n) ). This critical insight enables researchers to sample from complex posterior distributions in Bayesian analysis and other challenging probability distributions [3].

Table 1: Key Theoretical Concepts in Monte Carlo Methods

| Concept | Mathematical Foundation | Research Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Monte Carlo Integration | ( E[f(X)] \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} f(xi) ) | Enables high-dimensional integration in pharmacokinetic models |

| Markov Chain Convergence | ( \pi(B) = \int K(x,B)\pi(dx) ) | Ensures samples represent target distribution in Bayesian inference |

| Detailed Balance | ( \pi(x)T(x'|x) = \pi(x')T(x|x') ) | Foundation for constructing valid MCMC algorithms |

| Ergodicity | ( \lim{n\to\infty} \frac{1}{n} \sum{i=1}^{n} h(X_i) = \int h(x) \pi(dx) ) | Justifies using dependent samples for estimation |

Monte Carlo Methodologies and Protocols

Fundamental Monte Carlo Integration Protocol

Protocol 1: Monte Carlo Integration for Expectation Estimation

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for estimating complex integrals and expectations using basic Monte Carlo methods, particularly valuable in early research phases for establishing baseline results.

Problem Formulation

- Define the target integral in the form ( I = \int_{\Omega} f(x)p(x)dx ), where ( p(x) ) is a probability density function.

- Identify the sampling domain ( \Omega ) and ensure ( p(x) ) is a proper probability density (integrates to 1).

Sampler Implementation

- Implement an algorithm to generate independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) samples ( {xi}{i=1}^N ) from ( p(x) ).

- For standard distributions (normal, uniform, exponential), use established random number generators.

- For complex distributions, implement appropriate transformation or rejection sampling methods.

Estimation Procedure

- For each sample ( xi ), compute ( f(xi) ).

- Calculate the empirical average: ( \hat{I}N = \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^N f(x_i) ).

- Compute the sample variance: ( \hat{\sigma}^2N = \frac{1}{N-1} \sum{i=1}^N (f(xi) - \hat{I}N)^2 ).

Convergence Assessment

- Estimate the standard error: ( SE = \hat{\sigma}_N / \sqrt{N} ).

- Construct confidence intervals: ( \hat{I}N \pm z{\alpha/2} \cdot SE ), where ( z_{\alpha/2} ) is the appropriate quantile from the standard normal distribution.

- Determine if additional samples are needed to achieve desired precision.

This protocol finds application in molecular simulation, risk assessment in clinical trial design, and pharmacokinetic modeling, where rapid estimation of expectations is required [8] [9].

Metropolis-Hastings MCMC Protocol

Protocol 2: Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm for Complex Distributions

The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm enables sampling from distributions known only up to a normalizing constant, making it invaluable for Bayesian inference and complex stochastic models.

Initialization

- Choose an initial state ( x_0 ) from which the Markov chain will begin.

- Select a proposal distribution ( q(x'\|x) ) that is easy to sample from (e.g., symmetric normal distribution).

- Set the number of iterations ( N ) and burn-in period ( B ).

Iterative Sampling

- For ( t = 0, 1, 2, \ldots, N-1 ): a. Generate a candidate ( x' \sim q(x'\|xt) ). b. Compute the acceptance probability: [ \alpha = \min\left(1, \frac{p(x')q(xt\|x')}{p(xt)q(x'\|xt)}\right) ] where ( p(\cdot) ) is the target density (possibly unnormalized). c. Draw ( u \sim \text{Uniform}(0,1) ). d. If ( u \leq \alpha ), accept the candidate: ( x{t+1} = x' ). e. Otherwise, reject the candidate: ( x{t+1} = x_t ).

Post-processing

- Discard the first ( B ) samples as burn-in to ensure the chain has reached stationarity.

- Assess convergence using trace plots, autocorrelation, and diagnostic statistics.

- Use remaining samples ( {xB, x{B+1}, \ldots, x_N} ) for estimation.

The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm forms the foundation for Bayesian parameter estimation in drug development, allowing researchers to obtain posterior distributions for model parameters without complex analytical calculations [8] [9].

Figure 1: Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm Workflow. This diagram illustrates the iterative process of candidate generation and acceptance/rejection in the Metropolis-Hastings MCMC method.

Hamiltonian Monte Carlo Protocol

Protocol 3: Hamiltonian Monte Carlo for High-Dimensional Models

Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) employs physical system dynamics to efficiently explore high-dimensional parameter spaces, making it particularly suitable for complex hierarchical models in drug development.

System Setup

- Define the target distribution ( p(\theta) ) for parameters ( \theta ).

- Introduce auxiliary momentum variables ( \rho \sim \text{MultiNormal}(0, M) ), where ( M ) is the mass matrix.

- Construct the Hamiltonian: ( H(\rho, \theta) = -\log p(\theta) + \frac{1}{2} \rho^T M^{-1} \rho ).

Dynamics Simulation

- For each transition:

a. Sample new momentum: ( \rho \sim \text{MultiNormal}(0, M) ).

b. Simulate Hamiltonian dynamics using the leapfrog integrator:

- Calculate half-step update: ( \rho \leftarrow \rho - \frac{\epsilon}{2} \frac{\partial V}{\partial \theta} )

- Update position: ( \theta \leftarrow \theta + \epsilon M^{-1} \rho )

- Update momentum: ( \rho \leftarrow \rho - \frac{\epsilon}{2} \frac{\partial V}{\partial \theta} ) c. Repeat for ( L ) steps to obtain proposal ( (\rho^, \theta^) ).

- For each transition:

a. Sample new momentum: ( \rho \sim \text{MultiNormal}(0, M) ).

b. Simulate Hamiltonian dynamics using the leapfrog integrator:

Metropolis Correction

- Compute the acceptance probability: [ \alpha = \min\left(1, \exp(H(\rho, \theta) - H(\rho^, \theta^))\right) ]

- Accept or reject the proposal based on ( \alpha ).

Parameter Tuning

- Adjust step size ( \epsilon ) to achieve optimal acceptance rate (~65%).

- Set trajectory length ( L ) to ensure sufficient exploration.

- Adapt mass matrix ( M ) to account for parameter correlations.

HMC is particularly valuable in high-dimensional Bayesian models, molecular dynamics simulations, and complex pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling, where random walk methods become inefficient [10].

Table 2: Comparison of Monte Carlo Sampling Methods

| Method | Key Mechanism | Optimal Application Context | Convergence Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Monte Carlo | Independent sampling from target distribution | Simple integrals with standard distributions | ( O(1/\sqrt{N}) ) convergence, independent of dimension |

| Metropolis-Hastings | Proposal-acceptance with detailed balance | Complex Bayesian models with unnormalized densities | Burn-in period critical; monitor autocorrelation |

| Hamiltonian Monte Carlo | Hamiltonian dynamics with gradient information | High-dimensional correlated distributions | Tuning of ( \epsilon ) and ( L ) essential for efficiency |

| Gibbs Sampling | Conditional sequential updating | Models with tractable full conditionals | No tuning parameters; efficient for certain graphical models |

Research Applications and Case Studies

Bayesian Analysis in Epidemiological Studies

Monte Carlo methods have revolutionized Bayesian analysis in epidemiological research, which directly informs drug development decisions. A case study examining the association between residential magnetic field exposure and childhood leukemia demonstrates the practical application of MCMC [9]. The analysis utilized a logistic regression model of the form:

[ \text{Logit}(\Pr(D=1)) = \beta0 + \beta1 x ]

where ( x ) indicates exposure. Using MCMC methods, researchers obtained the posterior distribution of the odds ratio ( \exp(\beta_1) ), providing a complete characterization of uncertainty beyond point estimates. This approach enabled comprehensive uncertainty quantification essential for risk assessment in public health and pharmaceutical development.

The implementation followed these specific steps:

- Model Specification: Defined likelihood function based on binomial distribution and prior distributions for parameters.

- MCMC Configuration: Implemented Metropolis-Hastings algorithm with normal proposal distribution.

- Convergence Diagnostics: Monitored trace plots, autocorrelation, and Gelman-Rubin statistics.

- Posterior Analysis: Summarized posterior distributions using means, credible intervals, and density plots.

This case study illustrates how MCMC methods enable full Bayesian inference for epidemiological parameters, providing drug developers with robust evidence for target identification and risk-benefit assessment [9].

Uncertainty Quantification in Geophysical Inversions

The Obsidian software platform for 3-D geophysical inversion demonstrates advanced MCMC applications in complex physical systems, illustrating principles applicable to medical imaging and biophysical modeling in drug development [11]. This system addresses several challenges relevant to scientific computing:

- Multi-modal Posteriors: Implementation of parallel tempering to explore multiple modes simultaneously.

- High-Dimensional Parameter Spaces: Use of preconditioned Crank-Nicolson proposals for efficient exploration.

- Complex Constraints: Incorporation of geological prior information through structured prior distributions.

The methodology employed includes:

- Parallel Tempering: Maintaining multiple chains at different temperatures to facilitate mode switching.

- Adaptive Proposals: Adjusting proposal distributions based on chain history to improve efficiency.

- Multi-Sensor Data Fusion: Combining information from multiple sources with proper uncertainty weighting.

For drug development researchers, this case study illustrates sophisticated approaches to high-dimensional inverse problems relevant to medical imaging, system pharmacology, and quantitative systems toxicology [11].

Figure 2: MCMC Research Workflow. This diagram outlines the systematic process for implementing MCMC methods in research applications, from problem formulation to results interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MCMC

| Tool/Reagent | Specification/Purpose | Research Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stan Modeling Language | Probabilistic programming language with NUTS sampler | High-dimensional Bayesian inference | Automatic differentiation; optimal for models with continuous parameters |

| No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS) | Self-tuning variant of HMC | Eliminates manual tuning of trajectory length | Adaptive step size and mass matrix estimation during warmup |

| Preconditioned Crank-Nicolson | Proposal mechanism for Gaussian processes | Maintains stationarity for high-dimensional proposals | Preserves geometric structure of target distribution |

| Parallel Tempering | Multiple chains at different temperatures | Multi-modal posterior exploration | Enables mode switching through replica exchange |

| Chroma.js Palette Helper | Color palette generation and testing | Accessible data visualization | Ensures color blindness compatibility in research figures |

| Viz Palette Tool | Color deficiency simulation | Accessibility testing of visualizations | Critical for preparing inclusive conference presentations |

The Monte Carlo principle, evolving from basic integration techniques to sophisticated Markov chain methods, provides an indispensable framework for stochastic modeling in scientific research and drug development. Through protocols like Metropolis-Hastings and Hamiltonian Monte Carlo, researchers can tackle increasingly complex problems in Bayesian inference, parameter estimation, and uncertainty quantification. The continued development of MCMC methodologies ensures that scientists have access to powerful computational tools for extracting meaningful insights from complex stochastic models, ultimately accelerating the pace of discovery in pharmaceutical research and development.

Why MCMC? Tackling Intractable Distributions in High Dimensions

In computational statistics, physics, and pharmaceutical research, scientists frequently encounter complex probability distributions that are high-dimensional and analytically intractable. These posterior distributions arise from Bayesian models where the normalization constant—the marginal likelihood or evidence—is impossible to calculate analytically due to high-dimensional integration [8]. Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods provide a powerful computational framework for sampling from these complex distributions, enabling parameter estimation, uncertainty quantification, and scientific inference where traditional methods fail [3] [4].

The fundamental advantage of MCMC lies in its ability to approximate these intractable distributions using only the unnormalized functional form of the target distribution, bypassing the need to compute computationally prohibitive integrals [8]. This capability is particularly valuable in drug discovery and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PKPD) modeling, where researchers must estimate unknown parameters and input functions from sparse experimental data [4].

Theoretical Foundations: Why MCMC Works

Markov Chains and Stationary Distributions

MCMC methods construct a Markov chain whose stationary distribution equals the target probability distribution of interest. A Markov chain is a stochastic process where the probability of transitioning to any future state depends only on the current state, not on the path taken to reach it (the Markov property) [12]. Through careful algorithm design, these chains can be engineered so that after a sufficient number of transitions (the burn-in period), the chain produces samples from the desired target distribution [3] [8].

The mathematical foundation ensures that for a properly constructed Markov chain:

- The chain will converge to a unique stationary distribution π regardless of the starting point [3]

- After convergence, samples from the chain can be used as representative samples from the target distribution [3]

- The ergodic theorem guarantees that sample averages converge to the expected values under the target distribution [3]

The Detailed Balance Condition

MCMC algorithms satisfy the detailed balance condition, which ensures the Markov chain converges to the correct target distribution. This condition requires that for any two states A and B:

Where π(·) is the target distribution and T(·|·) is the transition probability [8]. This mathematical guarantee makes MCMC a principled approach rather than merely a heuristic.

Table 1: Key Properties for MCMC Convergence

| Property | Mathematical Definition | Role in MCMC |

|---|---|---|

| φ-Irreducibility | Any set with positive probability under φ can be reached from any starting point [3] | Ensures the chain can explore the entire state space |

| Aperiodicity | The chain does not exhibit periodic behavior [3] | Prevents cyclic behavior that would prevent convergence |

| Harris Recurrence | The chain returns to certain sets infinitely often [3] | Guarantees strong convergence properties |

| Positive Recurrence | The chain has a finite expected return time to all sets [3] | Ensures the existence of a stationary distribution |

MCMC Algorithms and Protocols

Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm

The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm is one of the most fundamental MCMC methods, providing a general framework for sampling from complex distributions [13].

Experimental Protocol

- Initialization: Choose an arbitrary starting point θ₀ and proposal distribution g(·|·)

- Iteration: For each time step t = 1, 2, ..., N:

- Proposal: Generate a candidate point θ* from g(θ|θₜ₋₁)

- Acceptance Ratio: Calculate α = min(1, [f(θ)g(θₜ₋₁|θ)]/[f(θₜ₋₁)g(θ|θₜ₋₁)]), where f(·) is the unnormalized target distribution

- Decision: Set θₜ = θ* with probability α, otherwise θₜ = θₜ₋₁

- Burn-in: Discard the first B samples (typically B = 10-20% of N) to ensure convergence

- Collection: Retain the remaining samples for analysis [8]

Workflow Visualization

Gibbs Sampling

Gibbs sampling is particularly useful for high-dimensional problems where the joint distribution is complex but conditional distributions are tractable [13].

Experimental Protocol

- Initialization: Choose starting values for all parameters: θ₁⁽⁰⁾, θ₂⁽⁰⁾, ..., θₚ⁽⁰⁾

- Iteration: For each sampling iteration t = 1, 2, ..., N:

- Sample θ₁⁽ᵗ⁾ ~ p(θ₁|θ₂⁽ᵗ⁻¹⁾, θ₃⁽ᵗ⁻¹⁾, ..., θₚ⁽ᵗ⁻¹⁾)

- Sample θ₂⁽ᵗ⁾ ~ p(θ₂|θ₁⁽ᵗ⁾, θ₃⁽ᵗ⁻¹⁾, ..., θₚ⁽ᵗ⁻¹⁾)

- ...

- Sample θₚ⁽ᵗ⁾ ~ p(θₚ|θ₁⁽ᵗ⁾, θ₂⁽ᵗ⁾, ..., θₚ₋₁⁽ᵗ⁾)

- Collection: Retain all samples after burn-in for analysis [13]

Table 2: Comparison of MCMC Sampling Algorithms

| Characteristic | Metropolis-Hastings | Gibbs Sampling |

|---|---|---|

| Generality | Works for almost any target distribution [13] | Requires sampling from full conditional distributions [13] |

| Proposal Distribution | Requires careful tuning [13] | Not needed; uses conditional distributions [13] |

| Ease of Use | Difficult to tune for good performance [13] | Easier when conditionals are known [13] |

| Computational Efficiency | Can be slow with poor proposal or correlated parameters [13] | Efficient if conditionals are easy to sample from [13] |

| Correlation Handling | Can handle correlated parameters but may mix slowly [13] | Can get stuck with highly correlated parameters [13] |

Pharmaceutical Application: Input Estimation in PKPD Modeling

Problem Formulation

In drug discovery, MCMC enables the estimation of unknown input functions to known dynamical systems given sparse measurements. This is particularly valuable for estimating oral absorption rates and bioavailability of drugs [4].

The problem can be formalized as estimating an input function u(t) in a system of ordinary differential equations:

Where x(t) is the system state, u(t) is the unknown input function, y(t) are measured quantities, and v(t) represents measurement noise [4].

MCMC Protocol for Input Estimation

Bayesian Framework

The input estimation problem is formulated in a Bayesian context:

Where:

- p(u(t)|y₁:ₙ) is the posterior distribution of the input function

- p(y₁:ₙ|u(t)) is the likelihood of observed data

- p(u(t)) is the prior distribution encoding assumptions about the input function [4]

Functional Representation

The input function u(t) is represented using a finite basis expansion:

Where Bᵢ(t) are basis functions and θᵢ are parameters to be estimated [4].

Prior Specification

Common priors for scalar input functions include:

- Smoothness priors: Penalize the j-th derivative ∫[dʲu/dtʲ]²dt [4]

- Gaussian process priors: Define priors using mean and covariance functions [4]

- Entropy priors: Encourage similarity between neighboring time points [4]

Input Estimation Workflow

Diagnostic Framework and Convergence Assessment

Visual Diagnostics

MCMC requires careful diagnostics to ensure valid results. Key diagnostic tools include:

- Trace plots: Visualize parameter values across iterations; good mixing should resemble "hairy caterpillars" [14]

- Autocorrelation plots: Assess correlation between successive samples; high autocorrelation reduces effective sample size [14]

- Energy plots: Diagnostic for Hamiltonian Monte Carlo, revealing potential sampling pathologies [14]

- Forest plots: Display credible intervals for multiple parameters simultaneously [14]

Quantitative Diagnostics

Convergence Metrics

- Gelman-Rubin statistic (R-hat): Compares within-chain and between-chain variance; values near 1.0 indicate convergence [14] [12]

- Effective Sample Size (ESS): Estimates the number of independent samples; low ESS indicates high autocorrelation [14]

- Geweke test: Compares means from early and late segments of the chain [12]

Diagnostic Protocol

- Multiple Chains: Run at least 4 chains with dispersed starting values

- Convergence Assessment: Calculate R-hat for all parameters; values <1.05 indicate convergence

- Sampling Efficiency: Compute ESS; aim for ESS > 400 for reliable inference

- Visual Inspection: Examine trace plots for good mixing and stationarity

- Model Refinement: If diagnostics indicate problems, reconsider priors or model structure [14]

Table 3: MCMC Diagnostic Interpretation and Actions

| Diagnostic | Ideal Result | Problem Indicated | Remedial Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trace Plot | Stable mean, constant variance, good mixing [14] | Drift, trends, or poor mixing [14] | Increase burn-in, adjust proposal distribution [14] |

| R-hat | < 1.05 [14] | > 1.1 indicates non-convergence [14] | Run longer chains, improve parameterization [14] |

| Effective Sample Size | > 400 per parameter [14] | Low ESS indicates high autocorrelation [14] | Increase iterations, thin chains, reparameterize [14] |

| Autocorrelation | Rapid decay to zero [14] | High, persistent autocorrelation [14] | Adjust sampler tuning parameters [14] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for MCMC Research

| Tool/Category | Function | Examples/Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic Programming Frameworks | Define Bayesian models and perform inference | PyMC (Python), Stan (C++), BUGS (standalone) [14] |

| Diagnostic Visualization | Assess convergence and sampling efficiency | ArviZ (Python), coda (R), MCMCvis (R) [14] |

| Optimization Libraries | Solve optimization problems for MAP estimation | CasADi (used in pharmaceutical applications) [4] |

| Specialized Samplers | Handle specific sampling challenges | Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC), No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS) [14] |

| High-Performance Computing | Parallelize chains and handle large models | MPI, GPU acceleration, cloud computing [15] |

Advanced Methodologies and Recent Developments

The field of MCMC continues to evolve with several advanced methodologies enhancing its applicability to high-dimensional problems:

Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC)

HMC uses gradient information to propose distant states with high acceptance probability, dramatically improving sampling efficiency in high-dimensional spaces [14]. The No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS) automatically tunes HMC parameters, making it suitable for complex models without manual tuning [14].

Sequential Monte Carlo (SMC)

SMC methods combine MCMC with particle filtering, making them particularly effective for sequential Bayesian problems and models with multimodality [3] [15].

Preconditioning and Adaptation

Recent theoretical advances in preconditioning MCMC algorithms have led to improved mixing in high-dimensional spaces [15]. Adaptive MCMC algorithms automatically tune proposal distributions during the sampling process, improving efficiency without compromising theoretical guarantees [15].

MCMC methods provide an indispensable framework for tackling intractable distributions in high-dimensional spaces, particularly in pharmaceutical research and drug discovery. By enabling sampling from complex posterior distributions, MCMC empowers researchers to quantify uncertainty, estimate unknown parameters and input functions, and make informed decisions based on sparse experimental data.

The continued development of MCMC methodology—including improved samplers, better diagnostic tools, and advanced theoretical understanding—ensures these methods will remain at the forefront of computational statistics and Bayesian inference for complex stochastic models in scientific research.

Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods represent a cornerstone of modern computational statistics, enabling researchers to draw samples from complex, high-dimensional probability distributions that are analytically intractable. These methods combine the probabilistic framework of Markov chains with Monte Carlo sampling to address challenging numerical integration and optimization problems across scientific disciplines. The evolution of MCMC from its origins in statistical physics to its current status as an indispensable tool in Bayesian inference, drug discovery, and machine learning demonstrates its fundamental importance in computational science. This article traces the historical development of MCMC methodologies, provides detailed experimental protocols for their implementation, and illustrates their practical applications in pharmaceutical research and development, with particular emphasis on stochastic modeling in drug discovery.

Historical Development of MCMC Methods

The theoretical foundations of MCMC methods emerged in the mid-20th century through pioneering work in statistical physics. The landmark development came in 1953 with the Metropolis algorithm, proposed by Nicholas Metropolis, Arianna and Marshall Rosenbluth, Augusta and Edward Teller at Los Alamos National Laboratory [3]. This algorithm was originally designed to solve complex integration problems in statistical physics using early computers, providing the first practical framework for sampling from probability distributions in high-dimensional spaces.

The field experienced another major advancement in 1970 when W.K. Hastings generalized the Metropolis algorithm, creating the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm and inadvertently introducing component-wise updating ideas that would later form the basis of Gibbs sampling [3]. Simultaneously, theoretical foundations were being solidified through work such as the Hammersley–Clifford theorem in Julian Besag's 1974 paper [3].

The "MCMC revolution" in mainstream statistics occurred following demonstrations of the universality and ease of implementation of sampling methods for complex statistical problems, particularly in Bayesian inference [3]. This transformation was accelerated by increasing computational power and the development of specialized software like BUGS (Bayesian inference Using Gibbs Sampling). Theoretical advancements, including Luke Tierney's rigorous treatment of MCMC convergence in 1994 and subsequent analysis of Gibbs sampler structure, further established MCMC as a robust framework for statistical computation [3].

Table 1: Key Historical Developments in MCMC Methods

| Year | Development | Key Contributors | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | Metropolis Algorithm | Metropolis, Rosenbluths, Tellers | First practical algorithm for sampling from high-dimensional distributions |

| 1970 | Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm | W.K. Hastings | Generalized Metropolis algorithm for broader applications |

| 1984 | Gibbs Sampling Formulation | Geman and Geman | Formal naming and application to image processing |

| 1990s | BUGS Software | Spiegelhalter et al. | Made Bayesian MCMC methods accessible to applied researchers |

| 1995 | Reversible Jump MCMC | Peter J. Green | Enabled handling of variable-dimension models |

Subsequent developments have continued to expand the MCMC toolkit, introducing particle filters (Sequential Monte Carlo) for sequential problems, Perfect sampling for exact simulation, and RJMCMC (Reversible Jump MCMC) for handling variable-dimension models [3]. These advancements have enabled researchers to tackle increasingly complex models that were previously computationally intractable.

Fundamental MCMC Algorithms and Protocols

Theoretical Foundations

MCMC methods create samples from a continuous random variable with probability density proportional to a known function [3]. These samples can be used to evaluate integrals, expected values, and variances. The fundamental concept involves constructing a Markov chain whose elements' distribution approximates the target distribution—that is, the Markov chain's equilibrium distribution matches the desired distribution [3]. The accuracy of this approximation improves as more steps are included in the chain.

A critical theoretical foundation is the concept of stationary distribution. For a Markov chain with transition kernel K(·,·), a σ-finite measure π is invariant if it satisfies:

π(B) = ∫X K(x,B) π(dx), for all B ∈ B(X) [3]

When such an invariant probability measure exists for a ψ-irreducible chain, the chain is classified as positive recurrent. The practical implication is that after a sufficient number of steps (the "burn-in" period), the samples generated by the chain can be treated as draws from the target distribution [16].

Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm Protocol

The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm remains one of the most widely used MCMC methods. The protocol below details its implementation:

Table 2: Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm Components

| Component | Description | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Target Distribution | Distribution π(·) to sample from | The equilibrium distribution to be approximated |

| Proposal Distribution | Conditional distribution q(·|x) | Generates candidate values based on current state |

| Acceptance Probability | α(x,y) = min(1, (π(y)q(x|y))/(π(x)q(y|x))) | Determines whether to accept or reject candidate |

| Initial Value | x0 in support of target distribution | Starting point for the Markov chain |

| Burn-in Period | Initial N iterations discarded | Eliminates bias from initial state selection |

Experimental Protocol:

Initialization: Select a starting value X0 belonging to the support of the target distribution. Choose a proposal distribution q(y|x) from which samples can be generated efficiently (e.g., multivariate normal with mean x) [16].

Iteration Step: For each iteration t = 1, 2, ..., N:

- Generate a proposal Y from the distribution q(·|Xt-1)

- Compute the acceptance probability: α(Xt-1, Y) = min(1, (π(Y)q(Xt-1|Y))/(π(Xt-1)q(Y|Xt-1)))

- Draw U from a Uniform(0,1) distribution

- If U ≤ α, accept the proposal and set Xt = Y; otherwise, reject the proposal and set Xt = Xt-1 [16]

Burn-in Removal: Discard the first B samples (typically 10-20% of total iterations) to eliminate the influence of the starting point [16].

Output: The remaining samples {XB+1, ..., XN} constitute the MCMC sample from the target distribution.

A key advantage of the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm is that it requires knowledge of the target density π(·) only up to a multiplicative constant, as this constant cancels in the acceptance probability ratio [16]. This property makes it particularly valuable for Bayesian inference, where posterior distributions are often known only up to a normalizing constant.

Gibbs Sampling Protocol

Gibbs sampling is another fundamental MCMC algorithm particularly useful for multivariate distributions. The protocol assumes we want to generate draws of a random vector X = (X(1), ..., X(k)) having joint density f(x(1), ..., x(k)).

Experimental Protocol:

Initialization: Select a starting vector X0 = (X0(1), ..., X0(k)) belonging to the support of the target distribution.

Iteration Step: For each iteration t = 1, 2, ..., N:

- Sample Xt(1) ~ f(x(1)|Xt-1(2), ..., Xt-1(k))

- Sample Xt(2) ~ f(x(2)|Xt(1), Xt-1(3), ..., Xt-1(k))

- ...

- Sample Xt(k) ~ f(x(k)|Xt(1), ..., Xt(k-1)) [16]

Burn-in Removal: Discard the first B samples to ensure convergence to the stationary distribution.

Output: The remaining samples {XB+1, ..., XN} constitute the MCMC sample from the target multivariate distribution.

Gibbs sampling is particularly efficient when the full conditional distributions are known and easy to sample from. The algorithm can be shown to be a special case of the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm where proposals are always accepted [16].

MCMC in Drug Discovery and Development

Input Estimation in Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics

MCMC methods have proven particularly valuable in pharmaceutical research for input estimation problems in pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling. In these applications, researchers aim to recover the form of an input function that cannot be directly observed and for which there is no generating process model [4].

A typical application involves estimating the oral absorption rate of a drug given measurements of drug plasma concentration, assuming a model of drug distribution and elimination is available [4]. Of particular interest is estimating oral bioavailability—the fraction of the drug that is absorbed into the systemic circulation [4].

The problem can be formally specified using a system of ordinary differential equations:

dx(t)/dt = f(t, x(t), u(t)) y(t) = g(t, x(t), u(t), v(t)) x(t0) = x0

where x(t) represents the system state, u(t) is the input function to be estimated, y(t) are the measured quantities, and v(t) represents measurement noise [4].

Bayesian MCMC Protocol for PK/PD Input Estimation:

Problem Specification:

- Define the prior for u(t), typically penalizing the first or second derivative to avoid unnecessarily oscillatory functions

- Choose a functional representation for u(t) using a finite set of parameters (e.g., piecewise constant functions or basis function expansions)

- Determine the statistical quantities of interest (e.g., MAP estimate, credible intervals) [4]

Implementation Options:

- Maximum a Posteriori (MAP) estimation using techniques from optimal control theory

- Full Bayesian estimation using MCMC approaches [4]

Case Study Application - Eflornithine Pharmacokinetics:

- Objective: Estimate oral absorption rate and bioavailability of eflornithine using pharmacokinetic data from rats

- Method: Represent the input function using a finite basis expansion and estimate coefficients using MCMC sampling

- Challenges: Sparse temporal sampling necessitates appropriate regularization [4]

Body Mass Response Modeling

Another application involves estimating energy intake based on body mass measurements in metabolic research [4]. This approach is particularly important in developing drugs aimed at reducing body mass or improving metabolic parameters.

Case Study Application - FGFR1c Antibody Research:

- Objective: Estimate energy intake from body-mass measurements of mice exposed to monoclonal antibodies targeting the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) 1c

- Method: Use MCMC-based input estimation to reconstruct unobserved energy intake patterns from longitudinal body mass data

- Outcome: Provides insights into drug mechanisms and efficacy through recovery of latent input functions [4]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for MCMC Implementation

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization Software (CasADi) | Provides tools for numerical optimization | Used for Maximum a Posteriori estimation in input problems [4] |

| Gaussian Process Priors | Defines prior distributions over functions | Regularizes input estimation; penalizes unnecessary complexity [4] |

| Karhunen–Loève Expansion | Basis function representation for stochastic processes | Dimensionality reduction for input function representation [4] |

| BUGS/Stan Platforms | High-level programming environments for Bayesian analysis | Implements complex MCMC models with minimal coding [9] |

| Proposal Distribution Tuners | Adaptive algorithms for proposal distribution adjustment | Optimizes MCMC sampling efficiency and convergence [16] |

Current Trends and Future Directions

The field of MCMC continues to evolve with several emerging trends. Recent methodological advances include improved algorithms for handling high-dimensional models, more efficient sampling techniques, and better convergence diagnostics. The integration of MCMC with other computational approaches such as variational inference and deep learning represents a particularly promising direction [17].

Upcoming scholarly events, including the "Advances in MCMC Methods" workshop scheduled for December 10-12, 2025, highlight the ongoing vitality of methodological research in this field [18]. Similarly, the International Conference on Monte Carlo Methods and Applications (MCM) 2025, scheduled for July 28 to August 1, 2025, at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago, will continue to bring together a multidisciplinary community of Monte Carlo researchers and practitioners [17].

Current research focuses on several cutting-edge areas, including Hamiltonian Monte Carlo for more efficient exploration of parameter spaces, Sequential Monte Carlo methods for dynamic models, and randomized quasi-Monte Carlo techniques for variance reduction [17]. These developments continue to expand the applicability and efficiency of MCMC methods across scientific domains.

In pharmaceutical applications, future directions include more sophisticated Bayesian hierarchical models for clinical trial design, improved methods for pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling, and enhanced approaches for biomarker identification and validation. As computational power increases and algorithms become more refined, MCMC methodologies will continue to provide indispensable tools for tackling the complex stochastic models that underlie modern drug discovery and development.

MCMC in Action: Key Algorithms and Real-World Applications in Biomedicine

Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods have revolutionized Bayesian statistics and the analysis of complex stochastic models, with the Metropolis-Hastings (M-H) algorithm standing as a foundational pillar of this computational framework. As a method for obtaining sequences of random samples from probability distributions where direct sampling is difficult, M-H has become indispensable across numerous scientific domains, particularly in pharmaceutical research and drug development. The algorithm's power lies in its ability to sample from complex posterior distributions that frequently arise in Bayesian inference, even when these distributions are only known up to a normalizing constant [19] [16]. This technical note explores the theoretical underpinnings, practical implementation, and specific applications of the M-H algorithm in stochastic modeling research, with particular emphasis on pharmaceutical applications.

Theoretical Foundations

The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm operates by constructing a Markov chain that explores the parameter space in such a way that the stationary distribution of the chain exactly equals the target distribution from which samples are desired [16]. This elegant mathematical property ensures that, after a sufficient number of iterations (including an appropriate burn-in period), the samples generated closely follow the target distribution [19] [16].

Formally, the algorithm requires only that the target probability density function ( P(x) ) be known up to a constant of proportionality, which aligns perfectly with the common scenario in Bayesian inference where posterior distributions are proportional to the product of likelihood and prior but have computationally intractable normalizing constants [20] [21].

The mathematical foundation rests on the detailed balance condition, which ensures the Markov chain converges to the correct stationary distribution. For a transition probability ( P(x' \mid x) ) and stationary distribution ( \pi(x) ), this condition requires ( \pi(x)P(x' \mid x) = \pi(x')P(x \mid x') ) for all ( x, x' ) [19]. The M-H algorithm achieves this through a carefully designed acceptance probability that corrects for asymmetries in the proposal distribution.

Algorithm Specification and Implementation

Core Algorithm

The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm proceeds through the following iterative steps [19] [20] [16]:

- Initialization: Choose an arbitrary starting point ( xt ) and a proposal distribution ( g(x' \mid xt) )

- Iteration for each time step ( t ):

- Generate a candidate sample ( x' ) from ( g(x' \mid xt) )

- Calculate the acceptance probability: [ \alpha = \min \left(1, \frac{P(x')}{P(xt)} \times \frac{g(xt \mid x')}{g(x' \mid xt)} \right) ]

- Generate a uniform random number ( u \in [0, 1] )

- If ( u \leq \alpha ), accept the candidate ( x_{t+1} = x' )

- Else, reject the candidate and set ( x{t+1} = xt )

A special case known as the Metropolis algorithm occurs when the proposal distribution is symmetric (i.e., ( g(x' \mid xt) = g(xt \mid x') )), which simplifies the acceptance probability to ( \alpha = \min \left(1, \frac{P(x')}{P(x_t)} \right) ) [19] [20].

Practical Implementation Considerations

Successful implementation requires careful attention to several practical aspects:

- Burn-in period: Initial samples should be discarded as they may follow a distribution different from the target, especially if the starting point is in a region of low probability density [19] [16]

- Autocorrelation: Unlike direct sampling methods, MCMC produces correlated samples, which reduces the effective sample size and increases estimation variance [19]

- Convergence diagnostics: Multiple methods exist for assessing convergence, including visual inspection of trace plots and more formal statistical tests [16]

Table 1: Common Proposal Distributions in Metropolis-Hastings Sampling

| Proposal Type | Formulation | Acceptance Probability | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Walk | ( x^* = x^{(t-1)} + z ) where ( z \sim N(0, \sigma^2) ) | ( \min \left(1, \frac{P(x^*)}{P(x^{(t-1)})} \right) ) | General purpose; multimodal distributions |

| Independence Chain | ( x^* \sim N(\mu, \sigma^2) ) (independent of current state) | ( \min \left(1, \frac{P(x^)q(x^{(t-1)})}{P(x^{(t-1)})q(x^)} \right) ) | When good approximation to target is available |

Experimental Protocols

Basic Implementation in R

The following protocol provides a complete implementation of the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm for sampling from an exponential distribution using a random walk proposal [20]:

Protocol for Bayesian Parameter Estimation

For Bayesian parameter estimation problems, such as estimating parameters of the van Genuchten model for soil water retention curves, the following protocol applies [22]:

- Model Specification: Define the likelihood function based on the scientific model and observational data

- Prior Selection: Choose appropriate prior distributions for all parameters

- Proposal Tuning: Select proposal distributions and tune their parameters (e.g., variance) to achieve acceptance rates between 20-40%

- Chain Configuration: Run multiple chains with different starting points to assess convergence

- Convergence Assessment: Monitor convergence using Gelman-Rubin statistics and trace plots

- Inference: Use post-burn-in samples for parameter estimation and uncertainty quantification

Table 2: Performance Metrics for M-H Algorithm in Different Scenarios

| Application Context | Optimal Acceptance Rate | Effective Sample Size (per 10,000 iterations) | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Van Genuchten Model Parameters [22] | 23-40% | ~1,000-2,500 | Strong parameter correlations, identifiability issues |

| Antimalarial Drug Sensitivity [23] | 25-45% | ~800-1,500 | Poor concentration design, parameter non-identifiability |

| Pharmacokinetic Input Estimation [4] | 20-40% | ~1,200-2,000 | High-dimensional input functions, sparse data |

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) Modeling

The M-H algorithm has proven particularly valuable in PK/PD modeling, where it enables estimation of unknown input functions to known dynamical systems given sparse measurements of state variables [4]. This input estimation problem arises when trying to recover the absorption profile of orally administered drugs or when estimating energy intake from body-mass measurements in metabolic studies.

In cases where the system dynamics are nonlinear, established linear deconvolution methods fail, making MCMC approaches essential. The M-H algorithm facilitates Bayesian input estimation by treating the unknown input function as a random process with appropriate prior distributions, often penalizing unnecessarily oscillatory solutions through Gaussian process priors or roughness penalties [4].

Antimalarial Drug Sensitivity Estimation

A specialized application of the M-H algorithm appears in estimating ex vivo antimalarial sensitivity in patients infected with multiple parasite strains [23]. Researchers developed a "Two-Slopes" model to estimate the proportion of each strain and their respective IC50 values (drug concentration that inhibits 50% of parasite growth).

The PGBO (Population Genetics-Based Optimizer) algorithm, based on M-H, demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional nonlinear regression methods, particularly when the experimental concentration design was suboptimal [23]. This application highlights the algorithm's robustness in complex pharmacological models where standard optimization techniques fail due to sensitivity to initial values or presence of local optima.

Visualization and Workflow

Diagram Title: Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm Workflow

Diagram Title: Markov Chain Convergence to Target Distribution

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for M-H Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Environment [20] [22] | Primary platform for algorithm implementation | Extensive MCMC packages (coda, mcmc, MCMCpack) |

| Proposal Distribution Tuner | Adjusts proposal variance for optimal acceptance | Target acceptance rate: 20-40% for random walk chains |

| Convergence Diagnostics | Assesses chain convergence to target distribution | Gelman-Rubin statistic, trace plots, autocorrelation |

| Burn-in Identifier | Determines initial samples to discard | Multiple heuristic approaches available |

| Effective Sample Size Calculator | Measures information content accounting for autocorrelation | Critical for estimation precision assessment |

The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm remains a versatile workhorse for stochastic models research, particularly in pharmaceutical applications where complex hierarchical models and intractable likelihood functions are common. Its ability to sample from posterior distributions known only up to a normalizing constant makes it indispensable for Bayesian inference in drug discovery and development.

While the algorithm presents challenges in terms of convergence diagnostics and parameter tuning, its flexibility continues to drive adoption across diverse domains. Future directions include development of more efficient proposal mechanisms, automated tuning procedures, and integration with other Monte Carlo methods such as Hamiltonian Monte Carlo for improved performance in high-dimensional spaces. As computational power increases and Bayesian methods become further entrenched in pharmaceutical research, the M-H algorithm will continue to serve as a fundamental tool for tackling increasingly complex inference problems.

Gibbs Sampling for Conditional Probability Structures

Gibbs sampling, a foundational Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method, enables researchers to sample from complex multivariate probability distributions by iteratively sampling from simpler conditional distributions [24] [25]. This algorithm has become indispensable across scientific domains where analytical solutions to Bayesian inference problems are intractable, including drug discovery, computational biology, and statistical physics [4] [26]. The core principle relies on constructing a Markov chain that converges to the target distribution by sequentially updating each variable while conditioning on the current values of all other variables [24]. For Bayesian practitioners, this provides a powerful mechanism to approximate posterior distributions for parameters of interest, enabling parameter estimation, uncertainty quantification, and model comparison without relying on potentially inaccurate asymptotic approximations [27].

Within pharmaceutical and biomedical research, Gibbs sampling offers particular advantages for problems with high-dimensional parameter spaces and complex dependency structures. The method's ability to decompose intricate joint distributions into manageable conditional distributions makes it suitable for hierarchical models common in pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling, protein structure prediction, and clinical trial analysis [4] [26]. Furthermore, when implementing Gibbs sampling within Bayesian frameworks, researchers can incorporate prior knowledge through carefully chosen prior distributions, which helps stabilize parameter estimates—especially beneficial when working with limited data [27].

Fundamental Principles and Algorithm

Mathematical Foundation

Gibbs sampling operates on the principle that the conditional distribution of one variable given all others is proportional to the joint distribution [24]. Formally, for a set of variables ( X = (X1, X2, ..., Xn) ), the conditional distribution for each variable ( Xj ) given all others is:

[ P(Xj = xj | (Xi = xi){i \neq j}) = \frac{P((Xi = xi){i})}{P((Xi = xi){i \neq j})} \propto P((Xi = xi){i}) ]

This proportionality means the normalizing constant (often computationally expensive to calculate) is not required for sampling [24]. The algorithm generates a sequence of samples that constitute a Markov chain, whose stationary distribution converges to the target joint distribution, allowing approximation of marginal distributions, expected values, and other statistical quantities [24] [25].

Algorithmic Implementation

The basic Gibbs sampling procedure follows these steps [24]:

- Initialize all variables ( X^{(0)} = (x1^{(0)}, x2^{(0)}, ..., x_n^{(0)}) )

- For each iteration ( t = 1, 2, ..., T ):

- Sample ( x1^{(t)} \sim P(X1 | x2^{(t-1)}, x3^{(t-1)}, ..., xn^{(t-1)}) )

- Sample ( x2^{(t)} \sim P(X2 | x1^{(t)}, x3^{(t-1)}, ..., xn^{(t-1)}) )

- ...

- Sample ( xn^{(t)} \sim P(Xn | x1^{(t)}, x2^{(t)}, ..., x_{n-1}^{(t)}) )

- Store the sequence of samples ( {X^{(1)}, X^{(2)}, ..., X^{(T)}} )

In practice, initial samples (the burn-in period) are typically discarded to ensure the chain has reached stationarity, and samples may be thinned to reduce autocorrelation [24]. The sequence of updates, known as a "scan," traditionally updates each variable exactly once per iteration, though heterogeneous updating schedules may improve efficiency for certain problems [28].

Table 1: Key Properties and Advantages of Gibbs Sampling

| Property | Description | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Avoids Marginalization | Direct sampling from conditionals eliminates need for difficult integration | Enables inference in hierarchical Bayesian models with latent variables |

| Automatically Satisfies Detailed Balance | Each conditional update maintains target stationary distribution | Guarantees convergence without additional acceptance steps |