Mapping the Disconnected Mind: Systems Biology Approaches to Brain Connectivity in Autism Spectrum Disorder

This article synthesizes the latest research on brain connectivity patterns in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) through the lens of systems biology.

Mapping the Disconnected Mind: Systems Biology Approaches to Brain Connectivity in Autism Spectrum Disorder

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest research on brain connectivity patterns in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) through the lens of systems biology. For researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational shift from categorical diagnoses to dimensional, biology-driven subtypes. The content details advanced methodological frameworks that integrate neuroimaging, transcriptomics, and AI-powered connectome analysis to map neural circuits and identify driver genes. We examine key challenges in data integration and model optimization, and present compelling validation from both human studies and cross-model preclinical research. The review concludes by highlighting emerging therapeutic targets and the promising clinical implications of a systems-level understanding of ASD pathophysiology, paving the way for precision medicine interventions.

Beyond Diagnosis: Uncovering the Shared and Divergent Neural Circuits of Autism

The classical categorical diagnosis of neurodevelopmental conditions is transitioning toward a dimensional, biology-driven framework. Groundbreaking research leveraging large-scale datasets and advanced computational models demonstrates that autism symptom severity maps onto distinct patterns of brain connectivity and related gene expression, transcending traditional diagnostic boundaries of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). This paradigm shift, central to modern autism systems biology research, reveals that shared clinical presentations are underpinned by shared biological features, including atypical maturation of large-scale brain networks and distinct genetic programs. This whitepaper details the key quantitative findings, experimental methodologies, and essential research tools that are defining the future of precision psychiatry and therapeutics for neurodevelopmental conditions.

Key Quantitative Findings: From Symptoms to Biology

Recent studies have moved beyond diagnostic labels to quantify the relationship between symptom severity and its neurobiological substrates. The tables below synthesize core findings from pivotal research.

Table 1: Brain Connectivity Correlates of Symptom Severity

| Symptom Dimension | Associated Brain Networks | Connectivity Pattern | Implicated Biological Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autism Symptom Severity (across ASD & ADHD diagnoses) | Frontoparietal (FP) and Default-Mode (DM) Networks [1] | Increased connectivity between FP and DM nodes [1] | Atypical functional maturation; decreased connectivity typical with age [1] |

| Rich-Club Organization (Structural & Functional) | Hub regions (e.g., medial frontal, medial parietal, insula) [2] | ASD: Higher connectivity inside rich club [2] | Disruption of global brain network efficiency and integration [2] |

| ADHD: Lower connectivity inside rich club; higher connectivity outside rich club [2] |

Table 2: Data-Driven ASD Subtypes and Their Biological Signatures

| ASD Subtype | Prevalence | Core Clinical Phenotype | Associated Genetics & Biology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social & Behavioral Challenges | ~37% [3] [4] | Core ASD traits; co-occurring ADHD, anxiety, depression; no developmental delays [3] [4] | Mutations in genes active postnatally; later age of diagnosis [4] |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | ~19% [3] [4] | Developmental delays (e.g., walking, talking); fewer co-occurring psychiatric conditions [3] [4] | Rare, inherited genetic variants; genes active prenatally [4] |

| Moderate Challenges | ~34% [3] [4] | Milder core ASD traits; no developmental delays or major psychiatric co-morbidities [3] [4] | Distinct biological pathways with little overlap to other subgroups [3] |

| Broadly Affected | ~10% [3] [4] | Widespread challenges: developmental delays, severe core traits, psychiatric co-morbidities [3] [4] | Highest proportion of damaging de novo mutations [4] |

Experimental Protocols: Core Methodologies

To ensure reproducibility and facilitate further research, this section outlines the detailed methodologies for key experiments cited.

Protocol: Connectome-Based Symptom Mapping and Spatial Transcriptomics

This integrative protocol links brain connectivity patterns with gene expression [1].

1. Participant Recruitment & Phenotyping:

2. Neuroimaging Data Acquisition:

- Modality: Resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI).

- Parameters: Standardized acquisition protocols on 3T MRI scanners. Ensure minimal head movement, with preprocessing steps to correct for motion artifacts.

3. Brain Network Construction:

- Preprocessing: Perform slice-time correction, realignment, normalization to standard space (e.g., MNI), and band-pass filtering.

- Parcellation: Apply a brain atlas to define network nodes (e.g., 200-400 regions).

- Edge Definition: Calculate Fisher-z transformed Pearson correlation coefficients between the mean time series of all node pairs to create a subject-specific functional connectivity matrix.

4. Connectome-Based Modeling:

- Symptom Mapping: Use multivariate linear models or machine learning to identify connections whose strength is significantly associated with autism symptom severity scores across the entire cohort, regardless of diagnosis [1].

5. In Silico Spatial Transcriptomic Analysis:

- Data Mapping: Map the significant functional connectivity patterns onto publicly available brain-wide gene expression data from the Allen Human Brain Atlas.

- Enrichment Analysis: Perform spatial correlation analyses to test for enrichment of the connectivity patterns with the expression maps of gene sets previously implicated in ASD and ADHD. This identifies biological processes (e.g., neural development) linked to the observed connectivity-symptom relationship [1].

Protocol: Person-Centered Subtyping via Mixture Modeling

This protocol identifies clinically and biologically distinct subgroups within a heterogeneous condition like autism [3] [4].

1. Data Collection from Large-Scale Cohorts:

- Cohort: Utilize large datasets (e.g., SPARK cohort) with deep phenotypic and genetic data from thousands of individuals with ASD.

- Phenotypic Variables: Collate over 230 variables per individual, including core ASD traits, co-occurring psychiatric conditions (ADHD, anxiety), developmental milestones, and cognitive profiles [3].

2. Data Integration with General Finite Mixture Modeling:

- Model Selection: Employ general finite mixture models due to their ability to handle different data types (binary, categorical, continuous) simultaneously.

- Clustering: The model calculates a probability for each individual belonging to a latent class based on their full phenotypic profile, thereby defining data-driven subgroups [3].

3. Genetic Analysis within Subtypes:

- Variant Analysis: Within each phenotypic subgroup, analyze the burden of various genetic variant types (e.g., de novo mutations, rare inherited variants).

- Pathway Analysis: Conduct gene set enrichment analyses to identify distinct biological pathways (e.g., neuronal action potentials, chromatin organization) significantly associated with each subtype. Notably, there is little overlap in impacted pathways between subtypes [3] [4].

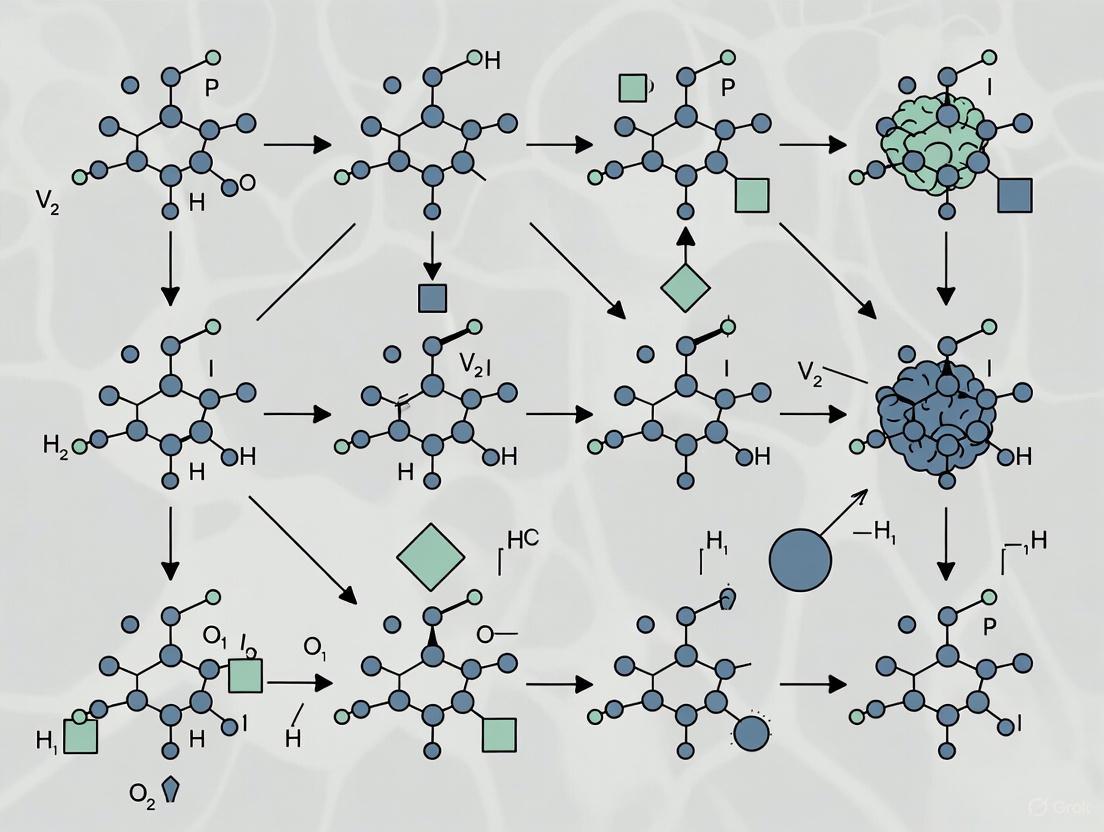

Visualizing the Research Workflow

The following diagram, generated using Graphviz, illustrates the integrated logical workflow of the dimensional paradigm research.

Research Workflow in the Dimensional Paradigm

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Resources for Dimensional Connectivity Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| SPARK Cohort Data | Large-scale dataset providing deep phenotypic and genotypic data for person-centered subtyping and genetic analysis [3] [4] | Over 5,000 participants with ASD; >230 phenotypic variables per individual [3] |

| Allen Human Brain Atlas | Publicly available spatial transcriptomic database for mapping brain connectivity patterns to gene expression [1] | Microarray data from postmortem brains across multiple cortical and subcortical regions |

| High-Angular Resolution Diffusion Imaging (HARDI) | Advanced MRI technique for mapping white matter structural connectivity with high fidelity [2] | Superior to DTI for resolving complex fiber crossings; used for rich-club organization analysis |

| General Finite Mixture Models | Computational model for integrating diverse data types to identify latent subgroups within heterogeneous populations [3] | Capable of handling binary, categorical, and continuous phenotypic data simultaneously |

| Conditional Variational Autoencoders (cVAE) | Deep generative model for inferring or generating personalized brain connectomes from individual characteristics [5] | Trained on large datasets (e.g., UK Biobank) to predict individual connectivity patterns |

| Graph Theory Metrics | Quantitative tools for analyzing the topological organization of brain networks [5] [2] | Includes clustering coefficient, path length, and rich-club coefficient |

| Rich-Club Analysis | A specific graph theory method to identify and analyze highly connected hub regions and their connections [2] | Differentiates between connections inside and outside the rich club, revealing distinct disorder profiles |

The profound heterogeneity inherent in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) presents a central obstacle to understanding its etiology and developing targeted interventions. This whitepaper synthesizes recent, high-dimensional data to argue that ASD heterogeneity can be systematically decomposed into biologically distinct groups through the integration of person-centered phenotypic parsing, neuroimaging-based stratification, and deep genomic analysis. We frame this decomposition within the broader thesis of brain connectivity patterns and systems biology, demonstrating that convergent biological signatures—spanning genetic programs, neural circuit dynamics, and developmental trajectories—underline clinically meaningful subgroups. This synthesis provides a roadmap for precision research and therapeutic development, moving beyond a unitary diagnostic model towards a stratified understanding of ASD pathobiology.

The Challenge of Heterogeneity: From Symptom to System

Autism spectrum disorder is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interaction alongside restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, yet its presentation is remarkably diverse [6]. This heterogeneity manifests across multiple levels: in core and co-occurring clinical phenotypes [6] [3], underlying genetic architectures [6] [7], and patterns of brain structure and function [8] [9] [10]. Traditional case-control paradigms, which assume biological homogeneity within the diagnostic group, have often yielded inconsistent neuroimaging findings and diluted genetic signals [10]. The field is consequently shifting towards data-driven, person-centered approaches that aim to identify robust subgroups with shared biological underpinnings, thereby reducing heterogeneity and linking specific mechanisms to clinical outcomes [6] [3] [9].

Decomposing Phenotypic Heterogeneity into Clinically Meaningful Classes

Recent large-scale studies leveraging extensive phenotypic and genetic data have successfully identified replicable, person-centered subgroups within ASD.

Key Experimental Protocol: Person-Centered Phenotypic Parsing via General Finite Mixture Modeling (GFMM)

- Cohort & Data: Analysis of 5,392 individuals from the SPARK cohort [6] [3]. The model incorporated 239 heterogeneous phenotype features from diagnostic questionnaires (SCQ, RBS-R, CBCL) and developmental history.

- Modeling Approach: A General Finite Mixture Model (GFMM) was employed to accommodate continuous, binary, and categorical data types without fragmenting individuals into separate traits [6]. This person-centered method clusters individuals based on their complete phenotypic profile.

- Validation: Model fit was assessed using Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and validation log-likelihood. Identified classes were validated against external medical history data (co-occurring diagnoses, interventions) and replicated in an independent cohort (Simons Simplex Collection, n=861) using matched features [6].

This analysis revealed four robust phenotypic classes with distinct profiles (Table 1) [6] [3].

Table 1: Phenotypic Classes Derived from Person-Centered Modeling

| Class Name | Approx. Prevalence | Core Phenotypic Profile | Co-occurring Conditions & Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social/Behavioral Challenges | 37% | High scores in social communication & restricted/repetitive behaviors; disruptive behavior, attention deficit, anxiety. | Enriched for ADHD, anxiety, depression; few developmental delays; later age of diagnosis. |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay (DD) | 19% | Nuanced presentation in core symptoms; strong enrichment of developmental delays. | Highly enriched for language delay, intellectual disability, motor disorders; lower levels of ADHD/anxiety. |

| Moderate Challenges | 34% | Consistently lower difficulties across all measured categories compared to other autistic children. | Fewer co-occurring challenges; no substantial developmental delays. |

| Broadly Affected | 10% | Consistently high difficulties across all seven phenotypic categories. | Enriched for almost all co-occurring conditions; cognitive impairment; early age of diagnosis; high number of interventions. |

Identifying Neural Subtypes Beyond Behavior

Phenotypic classes provide one axis of stratification; neuroimaging reveals distinct brain-based subtypes that may cut across or refine behavioral categories.

Key Experimental Protocol: Normative Modeling of Functional Connectivity for Neural Subtyping

- Cohort & Data: Resting-state fMRI data from 1046 participants (479 ASD, 567 typical development) across ABIDE-I and II sites [9].

- Feature Extraction: Multilevel functional connectivity features were calculated, including static functional connectivity strength (SFCS), dynamic functional connectivity strength (DFCS), and its variance (DFCV).

- Normative Modeling: Normative models of multilevel FC were built using the typical development (TD) group. For each ASD individual, deviations (Z-scores) from these normative trajectories were computed.

- Clustering: Clustering analysis was applied to the deviation scores to identify neural subtypes [9].

- Behavioral Correlation: Identified subtypes were compared on clinical scores (ADOS, SRS) and validated on an independent cohort (n=21 ASD) using gaze patterns from social eye-tracking tasks [9].

Studies using such approaches have identified at least two distinct neural subtypes with opposing functional connectivity deviation patterns (e.g., one with hyper-connectivity in visual/cerebellar networks and hypo-connectivity in frontoparietal/default mode networks, and another with the inverse pattern) despite comparable clinical symptom severity [9]. Other work has found unique multimodal neuroimaging signatures (e.g., combining fALFF and grey matter volume) associated with traditional DSM-IV subtypes (Autistic, Asperger’s, PDD-NOS), correlating with different ADOS subdomains [8]. Furthermore, effective connectivity within the Default Mode Network shows dynamic, age-related abnormalities in ASD, with patterns differing between children (mixed hyper-/hypo-connectivity) and adolescents/adults (predominantly hypo-connectivity) and correlating with symptom severity [11].

Table 2: Representative Neural Imaging Subtypes in ASD

| Subtyping Basis | Identified Subtypes | Key Neural Characteristics | Clinical/Behavioral Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normative FC Deviations [9] | Subtype A | Positive deviations in occipital/cerebellar networks; negative deviations in frontoparietal/DMN/cingulo-opercular networks. | Distinct gaze patterns on social eye-tracking tasks, despite similar ADOS scores. |

| Subtype B | Inverse pattern of deviations relative to Subtype A. | ||

| Multimodal Fusion (fALFF + GMV) [8] | Asperger’s PDD-NOS Autistic | Common basis in dorsolateral PFC & temporal cortex. Unique negative fALFF in subcortical areas (e.g., putamen-parahippocampus for Asperger’s; thalamus-amygdala-caudate for Autistic). | Each pattern correlates with different ADOS subdomains (social interaction is common). Subtype-specific patterns predict symptoms only within the corresponding subtype. |

| Cortical Thickness Normative Modeling [10] | 5 Clusters (e.g., Clusters 1-5) | Three clusters show widespread decreased CT; two show increased CT. | Clusters load differentially onto symptoms (e.g., one cluster with lower IQ, more severe ADOS-RRB, ADHD) and polygenic risk scores. |

Mapping Genetic Architecture onto Phenotypic and Neural Groups

The critical advance is linking these stratified groups to distinct biological programs. Genetic analyses reveal that the identified phenotypic classes are underpinned by divergent genetic architectures and molecular pathways.

Key Experimental Protocol: Genetic Analysis of Phenotypic Classes

- Analysis Framework: After phenotypic class assignment, genetic data (common variation via polygenic scores, de novo, and rare inherited variants) were analyzed within each class [6] [3].

- Pathway & Expression Analysis: Impacted genes were analyzed for enrichment in biological pathways and for their expression patterns across human brain development.

- Deep Learning Genomic Subtyping: An independent, interpretable deep learning framework analyzed genome-wide variant annotations (functional scores, conservation, TF motif disruption) from 18,673 features to identify genomic clusters [7].

Findings include:

- Class-Specific Pathway Disruption: The four phenotypic classes showed little overlap in their impacted biological pathways (e.g., neuronal action potentials, chromatin organization), each associated largely with a different class [3].

- Developmental Timing of Gene Expression: A key discovery was that genes impacted by mutations in the Social/Behavioral Challenges class were predominantly active postnatally, consistent with this group's fewer developmental delays and later diagnosis. Conversely, genes impacted in the Mixed ASD with DD class were predominantly active prenatally [6] [3].

- Genomic Clusters: Deep learning identified four robust genomic clusters with distinct patterns of de novo and polygenic variant burden and disruption of transcription factor regulatory networks, correlating with specific clinical traits [7].

- Symptom Severity Genetics: Brain connectivity patterns associated with autism symptom severity (across ASD and ADHD diagnoses) spatially overlap with the expression of genes implicated in both disorders, pointing to shared genetic mechanisms for shared clinical presentations [1].

- Profound Autism Biology: Toddlers with profound autism (the most severe phenotype) show dysregulation of specific gene pathways controlling embryonic proliferation, differentiation, neurogenesis, and DNA repair, distinguishing them from moderate/mild subtypes [12].

Table 3: Genetic Architecture Linked to Stratified Groups

| Stratified Group | Genetic & Molecular Signature | Implicated Biological Processes |

|---|---|---|

| Social/Behavioral Challenges Class [6] [3] | Variants affect genes active postnatally. | Pathways related to neuronal signaling, synaptic function. |

| Mixed ASD with DD Class [6] [3] | Variants affect genes active prenatally. | Chromatin organization, transcriptional regulation. |

| Deep Learning Genomic Cluster [7] | Distinct de novo/polygenic burden; unique TF network disruption. | Variant-specific regulatory architectures. |

| Profound Autism Subtype [12] | Dysregulated embryonic pathways. | Cell proliferation, neurogenesis, DNA repair (PI3K-AKT, RAS, Wnt signaling). |

| Symptom Severity (Transdiagnostic) [1] | Brain patterns align with expression of ASD/ADHD risk genes. | Neural development genes. |

Synthesis: Integrating Layers into Biologically Distinct Groups

The convergence of evidence advocates for a multi-axial framework to decompose ASD heterogeneity (Diagram 1). Person-centered phenotyping defines clinically coherent subgroups. Neuroimaging reveals brain circuit subtypes that may offer biomarkers and reflect differential neurodevelopmental trajectories. Genomics provides the mechanistic anchor, showing that these stratified groups are driven by differences in mutational burden, the developmental timing of gene disruption, and specific dysregulated molecular pathways. For example, a child in the "Broadly Affected" phenotypic class is more likely to have early prenatal pathogenic variants disrupting neurogenic pathways, potentially aligning with a neural subtype showing widespread connectivity deviations and the "profound autism" biological signature [6] [12].

Diagram 1: Framework for Decomposing ASD Heterogeneity into Biologically Distinct Groups.

Key signaling pathways implicated across subgroups, particularly in more severe forms involving early developmental disruption, include the PI3K-AKT-mTOR, RAS-ERK, and Wnt/β-catenin pathways [12]. These pathways converge on regulating fundamental processes like cell cycle progression, proliferation, and differentiation.

Diagram 2: Key Signaling Pathways Implicated in ASD Subtypes, Especially Profound Autism.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Advancing this stratified research agenda requires a suite of specialized resources and methodologies.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for ASD Stratification Research

| Category | Specific Solution / Resource | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cohort & Data | SPARK Cohort [6] [3] | Provides large-scale, matched phenotypic and genetic data for discovery. |

| Simons Simplex Collection (SSC) [6] | Provides deeply phenotyped independent cohort for replication. | |

| ABIDE I/II Databases [8] [11] [9] | Aggregated, multi-site neuroimaging datasets for brain-based subtyping. | |

| EU-AIMS LEAP Cohort [10] | Large, well-characterized cohort with multimodal data for normative modeling. | |

| Computational & Analytical | General Finite Mixture Models (GFMM) [6] | Person-centered statistical modeling for integrating heterogeneous phenotypic data. |

| Normative Modeling Frameworks [9] [10] | Quantifies individual deviations from typical neurodevelopmental trajectories. | |

| Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) [12] | Integrates multiple data modalities (clinical, molecular) to identify patient clusters. | |

| Interpretable Deep Learning Networks [7] | Analyzes high-dimensional genomic features to identify regulatory subtypes. | |

| Spectral Dynamic Causal Modeling (DCM) [11] | Estimates effective (directional) connectivity from fMRI data. | |

| Molecular & Genomic | MSigDB Hallmark Gene Sets [12] | Curated gene pathway databases for functional enrichment analysis. |

| SFARI Gene Database | Resource for known ASD-associated genes and variants. | |

| Spatial Transcriptomic Maps [1] | Databases linking gene expression patterns to brain anatomy. | |

| Phenotypic & Behavioral | Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) | Gold-standard behavioral assessment for core symptoms. |

| Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) | Quantitative measure of social impairment. | |

| Eye-Tracking Systems (e.g., Tobii) [9] | Objective measurement of social visual attention patterns. | |

| Experimental Models | Brain Cortical Organoids (BCOs) [12] | In vitro models to study early embryonic neurodevelopmental events. |

Key Experimental Workflow: A prototypical integrative study might follow the workflow in Diagram 3.

Diagram 3: Prototypical Workflow for Identifying Biologically Distinct ASD Groups.

Decomposing ASD heterogeneity into biologically distinct groups is no longer a theoretical goal but an active research program yielding reproducible results. The integration of person-centered phenotyping, brain connectivity subtypes, and deep genomic architecture is revealing a new taxonomy of ASD grounded in systems biology. This framework directly informs the development of stratified biomarkers and targeted therapies. Future directions must include:

- Longitudinal Designs: Tracking how these biological subgroups diverge in developmental trajectory and treatment response.

- Incorporating Non-Coding Genomics: Analyzing the >98% of the genome to understand regulatory contributions to subtypes [3].

- Cross-Disorder Integration: Further exploring shared biological dimensions with ADHD, epilepsy, and intellectual disability [1] [10].

- Circuit-Level Mechanisms: Linking genetic pathway disruptions to specific alterations in neural circuit function and dynamics observed in imaging subtypes.

For drug development professionals, this stratification offers a path to more homogeneous clinical trial populations and biologically rational target selection. For researchers, it provides a scaffold for moving beyond the "average autistic brain" to a nuanced understanding of the many autisms, each with its own origin story and path forward.

This whitepaper synthesizes current systems biology research on the atypical maturation of the Frontoparietal Network (FPN) and Default Mode Network (DMN) in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Converging evidence from large-scale neuroimaging datasets indicates that these central hubs undergo divergent developmental trajectories characterized by early delays, aberrant connectivity patterns, and network-level misintegration. These deviations are linked to core behavioral phenotypes of ASD, including executive dysfunction and impaired social cognition. We present quantitative analyses of developmental abnormalities, detailed experimental methodologies for replicating key findings, and essential research tools. This synthesis underscores the potential of connectivity-based biomarkers for stratifying ASD heterogeneity and informing targeted therapeutic development.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition whose system-wide effects can be conceptualized through the lens of disrupted large-scale brain network organization. The Frontoparietal Network (FPN) and Default Mode Network (DMN) are two cornerstone systems for higher-order cognition. The FPN, anchored in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and inferior parietal lobule (IPL), is critical for executive functions (EF) and cognitive control [13]. The DMN, comprising the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and temporoparietal junction (TPJ), is indispensable for social cognitive processes, including theory of mind and self-referential thought [14]. In typical development, these networks demonstrate a trajectory of increasing integration and segregation. In ASD, this process is disrupted, leading to a hierarchical disorganization that links low-level sensory processing abnormalities to higher-order cognitive and social deficits [15]. This whitepaper examines the aberrant maturation of these networks as a core feature of ASD's systems biology.

Network Profiles and Functional Roles

Table 1: Functional Anatomy of Key Networks in ASD

| Network | Core Brain Regions | Primary Cognitive Functions | Manifestation of Dysfunction in ASD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Default Mode Network (DMN) | Medial Prefrontal Cortex (mPFC), Posterior Cingulate Cortex (PCC), Precuneus, Temporoparietal Junction (TPJ), Hippocampus [14] | Self-referential processing, theory of mind (mentalizing), autobiographical memory, social cognition [14] | Hypoactivation during self-referential and mentalizing tasks; reduced long-range connectivity; altered developmental trajectory [14] |

| Frontoparietal Network (FPN) | Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (dlPFC), Inferior Parietal Lobule (IPL) [13] | Executive functions, working memory, cognitive control, goal-directed attention [13] | Over-recruitment in childhood; under-recruitment in adulthood; poor frontoparietal connectivity; wider network under-recruitment [16] [13] |

| Executive Network (EN) | Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (dlPFC) | Executive functions, social behavior regulation | Exacerbated age-related hypoconnectivity in adults with ASD, correlating with social cognition difficulties [17] |

The Default Mode Network in Social Cognition

The DMN is fundamentally implicated in processing information about the "self" and "other" [14]. Task-based fMRI studies consistently reveal hypoactivation of key DMN nodes in ASD: the ventral mPFC and PCC during self-referential judgments, and the dorsal mPFC and TPJ during mentalizing tasks requiring inference of others' mental states [14]. This functional deficit is paralleled by structural and intrinsic connectivity disruptions, suggesting an altered developmental trajectory of the DMN is a prominent neurobiological feature of ASD [14].

The Frontoparietal Network in Executive Function

Executive functioning deficits in ASD are linked to atypical recruitment and connectivity of the FPN. A meta-analysis of 16 fMRI studies (739 participants) found that while individuals with ASD activate prefrontal regions during EF tasks, they show differential recruitment of a wider network. Specifically, there is lesser activation in the bilateral middle frontal gyri, left inferior frontal gyrus, and right inferior parietal lobule compared to typically developing individuals [16]. This suggests a constrained executive network in ASD, limited primarily to the PFC, with poor recruitment of critical parietal regions [16].

Quantitative Trajectories of Atypical Maturation

Large-scale normative modeling studies using cross-sectional data from sources like the Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE I/II) and the Lifespan Human Connectome Project Development (HCP-D) have mapped the atypical development of the cortical hierarchy in ASD.

Developmental Trajectory of the Functional Hierarchy

Research analyzing the principal functional connectivity gradient reveals a non-linear maturational trajectory in ASD [15]:

- Delayed Maturation in Childhood: Significant deviations from typical development are observed during childhood.

- Adolescent "Catch-up" Phase: A period of accelerated development occurs during adolescence.

- Young Adult Decline: A subsequent decline in the functional hierarchy is observed in young adulthood [15].

This trajectory differs across networks. Sensory and attention networks show the most pronounced abnormalities in childhood, while higher-order networks like the DMN remain impaired from childhood through adolescence [15].

Table 2: Deviations in Network Connectivity Across Development in ASD

| Network | Childhood Manifestation | Adolescent/Adult Manifestation | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Default Mode Network (DMN) | Remains impaired; reduced segregation [15] | Persistent reduction in segregation [15]; mixed under-/over-connectivity patterns [18] | Impaired social cognition, self-referential processing [14] |

| Frontoparietal Network (FPN) | Over-activation relative to controls [13] | Under-activation and hypoconnectivity relative to controls [16] [17] [13] | Executive dysfunction, working memory deficits [16] [13] |

| Sensory/Attention Networks | Most pronounced functional deviations [15] | Deviations may normalize or change pattern | Atypical low-level sensory processing [15] |

Structural Connectivity and Symptom Prognosis

Longitudinal diffusion MRI data reveals that the development of structural connectivity within the FPN has clinical prognostic value. Youths with ASD show a significant decrease in structural connectivity within the FPN and its broader connections during adolescence and early adulthood, whereas these connections typically increase in typically developing controls [19]. Crucially, the strength of baseline connectivity in this subnetwork was found to predict a lower symptom load at follow-up 3-7 years later, independent of baseline symptoms [19].

Experimental Protocols for Network-Level Analysis

Normative Modeling of Functional Hierarchy

Objective: To characterize individual-level deviations in the functional connectome hierarchy of individuals with ASD across a wide age range [15].

Workflow:

- Data Acquisition: Collect resting-state fMRI and T1-weighted structural MRI data. Large public datasets like ABIDE I/II and HCP-D are typically used.

- Data Preprocessing: This includes standard steps: realignment, coregistration, normalization, and segmentation. Scrutinize fMRI data for excessive head motion (e.g., mean framewise displacement ≥ 0.5 mm) and exclude participants accordingly [15].

- Cortical Hierarchy Estimation: Estimate the principal functional connectivity gradient using diffusion map embedding applied to the functional connectivity matrix [15].

- Normative Model Fitting: Establish a normative trajectory of typical development using a flexible model like the Generalized Additive Model for Location, Scale, and Shape (GAMLSS) on data from typically developing controls. This model captures non-linear age-related changes [15].

- Deviation Quantification: For each individual with ASD, calculate centile scores representing their deviation from the normative curve. Derive a whole-brain summary metric, the functional hierarchy score, to measure the extent of abnormal maturation [15].

Figure 1: Workflow for normative modeling of the functional connectome hierarchy.

Leading Eigenvector Dynamics Analysis (LEiDA)

Objective: To identify and discriminate ASD subtypes based on recurring patterns of functional network connectivity (FNC) in resting-state fMRI data [20].

Workflow:

- Data Preprocessing: Standard resting-state fMRI preprocessing, including head motion correction and band-pass filtering.

- Phase-Signal Extraction: For each time point, calculate the instantaneous phase of the BOLD signal for all brain regions (e.g., using the Hilbert transform).

- Leading Eigenvector Calculation: At each time point, compute the leading eigenvector of the phase coherence matrix, which represents the dominant pattern of phase alignment across the brain.

- Clustering: Apply k-means clustering to all the leading eigenvectors across all participants and time points to identify a set of reproducible brain states (FNC patterns).

- Occupancy Analysis: For each participant, calculate the frequency of occurrence (occupancy rate) of each brain state.

- Subtyping: Use the occupancy rates as features to identify neurophysiological subtypes of ASD and compare them to neurotypical controls [20].

Network-Based Statistics for Longitudinal Structural Connectomics

Objective: To identify subnetworks of white matter connections that show significant longitudinal changes and group differences between ASD and typically developing controls [19].

Workflow:

- Data Acquisition & Processing: Acquire longitudinal diffusion MRI data. Reconstruct whole-brain structural connectomes using tractography. Generate weighted connectivity matrices representing the number of streamlines between brain regions.

- Thresholding: Apply consistency-based thresholding (e.g., preserving the 50% most-consistent connections) to balance false positives and negatives [19].

- Statistical Analysis - NBS: Input the connectivity matrices into the Network-Based Statistics (NBS) framework.

- Perform a repeated-measures ANOVA at each connection to identify effects of time, diagnosis, and their interaction.

- Form a set of suprathreshold connections using an initial primary threshold (e.g., p < 0.001).

- Identify any connected subnetworks within the suprathreshold set.

- Non-Parametric Testing: Permute the data (e.g., 10,000 times) to build an empirical null distribution of the maximal connected subnetwork size. Calculate family-wise error (FWE) corrected p-values for each identified subnetwork [19].

- Clinical Correlation: Correlate baseline connectivity strength within significant subnetworks with future symptom changes to assess prognostic value [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Investigating Network Atypicality in ASD

| Resource Category | Specific Tool / Dataset | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Public Data Repositories | ABIDE I & II (Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange) | Provides pre-processed and raw resting-state fMRI, structural MRI, and phenotypic data from hundreds of individuals with ASD and controls for large-scale analyses [15] [20]. |

| HCP-D (Lifespan Human Connectome Project - Development) | Provides high-resolution multimodal neuroimaging data from typically developing children and adolescents, serving as a normative baseline for modeling developmental trajectories [15]. | |

| Analytical Toolboxes | GAMLSS (Generalized Additive Model for Location, Scale, and Shape) | A flexible statistical framework used to build normative models of brain development that can capture non-linear age-related trajectories [15]. |

| NBS (Network-Based Statistics) | A non-parametric statistical method for identifying significant differences in connected subnetworks within entire brain connectomes, while controlling for family-wise error [19]. | |

| LEiDA (Leading Eigenvector Dynamics Analysis) | A computational method to identify recurring whole-brain coupling modes (states) from resting-state fMRI data and their temporal properties, useful for subtyping [20]. | |

| Clinical & Behavioral Assessments | ADOS (Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule) | The gold-standard observational assessment for diagnosing and confirming ASD in research participants [13]. |

| SRS-2 (Social Responsiveness Scale, 2nd Edition) | A quantitative, continuous measure of social impairments and autistic traits, often used as a correlate in neuroimaging studies [17]. | |

| WASI (Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence) | A brief reliable measure of cognitive ability and IQ, used for participant characterization and inclusion criteria (e.g., IQ ≥ 70) [13]. |

Integrated Discussion: Convergence and Implications for Intervention

The evidence converges on a model where the FPN and DMN in ASD follow deviant and non-linear developmental trajectories that disrupt the typical balance of network integration and segregation [15]. The persistent reduction in DMN segregation is a key contributor to atypical cortical hierarchy [15], while the FPN shows an age-dependent pattern of initial over- then under-connectivity, with its structural development predicting long-term symptom outcomes [16] [19].

These findings have critical implications for therapeutic development. The identification of distinct neurophysiological subtypes within the ASD population, characterized by opposite patterns of functional deviations in the DMN, FPN, and other networks [21] [20], underscores the necessity for personalized intervention strategies. Furthermore, the prognostic value of structural FPN connectivity [19] highlights its potential as a biomarker for predicting natural history and treatment response. Interventions aimed at promoting the normative development and interaction of these higher-order networks, particularly during critical developmental windows like childhood and adolescence, may be fundamental for improving long-term outcomes in ASD.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by challenges in social communication and the presence of restricted, repetitive behaviors, with sensory processing differences now recognized as a core diagnostic feature [22]. The neurobiological underpinnings of ASD are increasingly understood through the lens of atypical brain connectivity, a concept described as a developmental disconnection syndrome [23]. Despite significant genetic heterogeneity, with hundreds of genes implicated in ASD etiology, research has revealed common disruptions in neural circuits that transcend specific genetic variations [24].

Within this framework of connectivity dysfunction, sensory processing regions have emerged as particularly vulnerable sites of impairment. Recent evidence suggests that sensory regions may be among the first and most consistently affected areas in ASD, with cascading effects on higher-order cognitive and social functions [25]. This whitepaper synthesizes cutting-edge preclinical research that identifies the piriform cortex, a key olfactory processing region, as a consistently impaired neural hub across multiple ASD mouse models. The convergence of findings on this structure across diverse genetic models provides a powerful lens through which to examine shared circuit-level deficits in ASD and offers promising targets for therapeutic development.

The Piriform Cortex: A Consistently Vulnerable Hub in ASD Models

Convergent Evidence from Multiple Preclinical Models

Groundbreaking research utilizing whole-brain mapping approaches has revealed that the piriform cortex displays consistent abnormalities across genetically distinct ASD mouse models. A seminal study by Hsu et al. employed an AI-powered platform called BM-auto (Brain Mapping with Auto-ROI correction) to systematically analyze whole-brain connectivity in three different ASD mouse models: Tbr1+/-, Nf1+/-, and Vcp+/R95G [23]. Despite the distinct molecular functions of these genes—Tbr1 encodes a neuron-specific transcription factor, Nf1 a scaffold protein regulating RAS and cAMP pathways, and VCP an ATPase chaperone involved in multiple cellular processes—all three mutations resulted in common circuit deficits centered on the piriform cortex [23].

The consistency of piriform cortex impairment across these models is particularly striking given their different primary molecular mechanisms. While each mutation caused unique connectivity alterations in various brain regions, the piriform cortex was the only area consistently impaired across all three models, showing reduced YFP signals and fewer Thy1-YFP+ neurons [23]. This convergence suggests that this olfactory processing region may represent a point of vulnerability in neural development that is sensitive to diverse ASD-related genetic perturbations.

Table 1: Piriform Cortex Abnormalities Across ASD Mouse Models

| Mouse Model | Genetic Function | Piriform Cortex Structural Deficits | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tbr1+/- | Neuron-specific transcription factor critical for forebrain development | Reduced YFP signals, fewer Thy1-YFP+ neurons | Olfactory discrimination impairments, altered social behavior |

| Nf1+/- | Scaffold protein regulating RAS and cAMP pathways | Reduced YFP signals, fewer Thy1-YFP+ neurons | Olfactory discrimination impairments |

| Vcp+/R95G | ATPase chaperone involved in ER formation and protein degradation | Reduced YFP signals, fewer Thy1-YFP+ neurons | Olfactory discrimination impairments, weakened functional connectivity |

| Cntnap2-/- | Neurexin family protein, cell adhesion | Increased trial-to-trial neural variability in olfactory bulb | Impaired odor recognition with novel background odors |

| Shank3B+/- | Postsynaptic scaffolding protein at excitatory synapses | Increased trial-to-trial neural variability in olfactory bulb | Impaired odor recognition with novel background odors |

Structural and Functional Impairments

The structural abnormalities observed in the piriform cortex of ASD models have significant functional consequences. The reduced YFP signals and fewer Thy1-YFP+ neurons indicate either impaired development or maintenance of projection neurons in this region, potentially disrupting its widespread connectivity with other brain areas [23]. Behaviorally, all three mutant models (Tbr1+/-, Nf1+/-, and Vcp+/R95G) exhibited olfactory discrimination impairments, being able to detect odors but unable to distinguish between them [23] [26].

Further strengthening the role of the piriform cortex in ASD-relevant behaviors, researchers demonstrated that manipulating piriform cortex activity directly altered social behavior patterns [23]. When neuronal activity in the piriform cortex was suppressed using chemogenetics, normally functioning mice displayed reduced social behaviors, establishing a functional link between olfactory processing and social interaction [23] [26]. Additional investigations in Vcp+/R95G mice revealed weakened functional connectivity between the piriform cortex and other brain regions, along with significantly lower overall brain activity in response to odor stimulation compared to wild-type mice [26]. These findings suggest that piriform cortex dysfunction in ASD models not only disrupts smell perception but also impairs brain-wide network coordination, potentially contributing to broader behavioral deficits.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Whole-Brain Mapping with BM-auto Platform

The identification of the piriform cortex as a consistent hub of impairment across ASD models was enabled by advanced whole-brain mapping technologies. The BM-auto platform represents a significant methodological innovation, combining whole-brain immunostaining with AI-driven registration and analysis [23] [26]. This system improved upon previous whole-brain imaging and quantification methods by integrating advanced artificial intelligence to automatically perform region-of-interest correction (auto-ROI) [23].

The experimental workflow begins with preparation of brain samples from Thy1-YFP transgenic mice, which express yellow fluorescent protein in a subset of projection neurons, enabling visualization of axonal projections and structural connectivity [23]. Following whole-brain fluorescence imaging, the BM-auto pipeline involves initial registration to Allen Mouse Common Coordinate Framework version 3 templates, followed by auto-ROI correction of original CCFv3 regional masks using a pre-trained deep learning model [23]. This automated correction system, trained on ground truth data collected over five years, can accurately identify and quantify more than 500 brain regions per hemisphere [26]. The auto-ROI corrected regional masks are then used to quantify segmented YFP+ pixels and YFP+ cell numbers across brain regions, with subsequent slice-based analysis to statistically assess distribution differences between ASD models and wild-type littermates [23].

Functional and Behavioral Assessments

Complementing the structural connectivity analysis, researchers employed several functional and behavioral approaches to characterize the consequences of piriform cortex deficits:

Olfactory Discrimination Tests: Mice were assessed for their ability to distinguish between different odors. While all mutant models could detect odors, they showed significant impairments in discriminating between odors compared to wild-type controls [23].

Chemogenetic Manipulations: To establish causal relationships between piriform cortex function and behavior, researchers used chemogenetics (DREADDs) to selectively inhibit neuronal activity in bilateral piriform cortices during behavioral tests. This approach demonstrated that suppressing piriform cortex activity in wild-type mice reduced social interaction behaviors, mimicking deficits seen in ASD models [23] [26].

Wide-Field Calcium Imaging: Studies in Cntnap2-/- and Shank3B+/- mouse models utilized wide-field calcium imaging of the olfactory bulb to measure neural responses to odors. These experiments revealed that ASD models showed greater trial-to-trial neural variability than WT mice, but that training with background odors stabilized these responses and improved behavioral performance [27].

Resting-State Functional Connectivity: Human studies have examined functional connectivity of primary sensory networks, including the olfactory cortex, using resting-state functional MRI. These investigations have identified abnormal connectivity patterns in individuals with ASD, particularly in primary auditory and somatosensory regions [25].

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Neural Response Alterations in ASD Models

Table 2: Neurophysiological Alterations in Sensory Processing Across ASD Models and Human Studies

| Measurement Type | Specific Component | Observed Difference in ASD | Functional Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERP/ERF Latencies | P/M50 | Significantly longer latencies (SMD=0.44) [28] | Sensory filtering challenges |

| ERP/ERF Latencies | P/M100 | Significantly longer latencies (SMD=0.18) [28] | Early sensory processing delays |

| ERP/ERF Latencies | N170 | Significantly longer latencies (SMD=0.33) [28] | Social perception alterations |

| ERP/ERF Latencies | P/M200 | Significantly longer latencies (SMD=0.30) [28] | Later processing stage delays |

| Neural Response Variability | Olfactory bulb responses | Greater trial-to-trial variability in Cntnap2-/- and Shank3B+/- models [27] | Unstable sensory representations |

| Functional Connectivity | Primary sensory networks | Widespread alterations, particularly in auditory and somatosensory regions [25] | Atypical information integration |

Research Reagent Solutions for Sensory Processing Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Investigating Sensory Processing in ASD Models

| Research Reagent | Specific Example | Function/Application | Key Findings Enabled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transgenic Mouse Lines | Thy1-YFP-H (B6.Cg-Tg(Thy1-YFP)HJrs/J) [23] | Labels subset of projection neurons for structural connectivity analysis | Revealed reduced YFP+ neurons in piriform cortex across ASD models |

| ASD Mouse Models | Tbr1+/-, Nf1+/-, Vcp+/R95G [23] | Model diverse genetic causes of ASD | Identified consistent piriform cortex deficits despite genetic heterogeneity |

| Calcium Indicator Lines | Thy1-GCaMP6f (C57BL/6J-Tg(Thy1-GCaMP6f) GP5.11Dkim/J) [27] | Enables in vivo imaging of neural activity | Revealed increased trial-to-trial variability in olfactory bulb responses |

| Chemogenetic Tools | DREADDs (Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs) [23] | Allows selective manipulation of neural activity | Established causal role of piriform cortex in social behavior deficits |

| c-Fos Antibodies | Cell Signaling Technology #2250 [23] | Marks recently activated neurons | Mapped functional connectivity and whole-brain synchronization patterns |

Integration with Broader Autism Systems Biology

Relationship to Brain-Wide Connectivity Patterns

The consistent impairment of the piriform cortex across ASD models fits within broader theories of ASD neuropathology that emphasize connectivity deficits. One prominent theory suggests that ASD involves long-range hypoconnectivity alongside short-range hyperconnectivity [24]. The piriform cortex, with its extensive connections to multiple brain regions including limbic and prefrontal areas, may be particularly vulnerable to such dysconnectivity.

Human neuroimaging studies have corroborated these preclinical findings, demonstrating abnormal functional connectivity in primary sensory networks in individuals with ASD [25]. These investigations have revealed that abnormal connectivity patterns correlate with clinical symptoms and may undergo developmental changes, with potential early overgrowth followed by altered developmental trajectories [25] [24]. The consistent identification of piriform cortex abnormalities across species enhances the translational validity of this brain region as a key node in ASD pathophysiology.

Developmental Trajectory and Critical Periods

Sensory circuit development continues until early adulthood, with specific critical periods during which neural circuits are particularly sensitive to intrinsic and extrinsic factors [29]. During these windows, disturbed expression of ASD risk genes may lead to exaggerated brain plasticity processes within sensory circuits [29]. The piriform cortex, as a phylogenetically ancient three-layered cortex, may have distinct developmental trajectories compared to neocortical regions, potentially contributing to its particular vulnerability in ASD.

Research suggests that the biological processes underlying brain overgrowth in a subgroup of individuals with ASD may include excess neurogenesis, decreased cell death, neuronal hypertrophy, and elevated myelination [24]. These mechanisms could differentially affect various brain regions, with the piriform cortex potentially experiencing altered developmental timing or excessive connectivity pruning during critical periods.

Implications for Therapeutic Development

Targeted Intervention Strategies

The identification of the piriform cortex as a consistently impaired hub in ASD models opens promising avenues for therapeutic development. Several approaches emerge as particularly viable:

Sensory Enrichment Strategies: Research has shown that prolonged exposure to sensory stimuli can improve behavioral performance and stabilize neural responses in ASD models [27]. For example, training with background odors enhanced both behavioral performance and neural discriminability of odor mixtures in Cntnap2-/- and Shank3B+/- mice [27]. This suggests that structured sensory exposure protocols might help normalize circuit function in sensory regions.

Circuit-Targeted Neuromodulation: The demonstration that TBS-induced activation at the anterior basolateral amygdala increased whole-brain synchronization and improved social interactions in Tbr1+/- mice suggests that targeted stimulation of specific nodes within affected circuits could have therapeutic benefits [23]. Similar approaches might be developed for the piriform cortex.

Critical Period Interventions: Given the importance of developmental timing in sensory circuit formation, interventions during specific developmental windows may prove most effective. Understanding the maturation timeline of piriform cortex circuits could inform optimal timing for interventions.

Biomarker Development

The consistent nature of piriform cortex abnormalities across ASD models suggests potential for developing objective biomarkers based on this brain region. Neurophysiological measures of sensory processing, such as ERP/ERF latencies, show promise as potential biomarkers, though substantial heterogeneity and modest effect sizes currently limit clinical application [28]. Further research is needed to determine whether piriform cortex structure or function could serve as stratification biomarkers to identify patient subgroups most likely to respond to targeted therapies.

The converging evidence from multiple ASD mouse models establishes the piriform cortex as a consistently impaired neural hub that transcends specific genetic etiology. This convergence is particularly significant given the genetic heterogeneity of ASD and suggests that this phylogenetically ancient olfactory cortex may represent a point of vulnerability in neural circuit development. The structural deficits, functional impairments, and altered connectivity of this region demonstrate its central role in ASD-related circuit dysfunction.

From a systems biology perspective, the piriform cortex represents a key node where genetic risks converge to disrupt neural circuit formation, with cascading effects on sensory processing, network integration, and ultimately, social behavior. Future research should focus on elucidating the developmental timeline of these abnormalities, their sex-specific manifestations, and their potential reversibility through targeted interventions. The strategic position of the piriform cortex within broader brain networks makes it an promising target for therapeutic development and biomarker identification in ASD.

From Data to Discovery: Multi-Omic Integration and AI-Powered Connectome Analysis

The integration of macroscale brain connectivity with microscale molecular data represents a paradigm shift in neurodevelopmental research. This technical guide delineates the methodologies for mapping functional brain connectivity patterns onto gene expression landscapes, with a specific focus on autism spectrum disorder (ASD) systems biology. We present a comprehensive framework that leverages cutting-edge spatial transcriptomic technologies, deep learning algorithms, and multi-omic integration strategies to bridge the gap between network-level functional aberrations and their underlying molecular determinants. The protocols and analyses detailed herein provide researchers with practical tools for elucidating the multi-scale pathophysiology of ASD and identifying novel therapeutic targets.

The mammalian brain operates as a complex, multi-scale system where macroscale functional connectivity patterns emerge from microscale molecular processes. In autism spectrum disorder, postmortem studies have revealed increased density of excitatory synapses, with a putative link to aberrant mTOR-dependent synaptic pruning [30]. Concurrently, neuroimaging studies consistently document atypical large-scale functional networks in ASD, characterized by functional hyperconnectivity [31] [30]. These observations raise a critical question: how do molecular alterations at the synaptic level translate to system-wide functional connectivity disturbances?

In silico spatial transcriptomics has emerged as a powerful approach to bridge this divide by computationally linking gene expression patterns with functional connectivity metrics. This integration enables researchers to:

- Identify transcriptomic signatures that spatially correlate with functional connectivity alterations in ASD

- Map disease-risk genes to specific functional brain networks

- Uncover cell-type-specific contributions to network-level phenotypes

- Decode the developmental trajectories of connectivity-gene relationships across the lifespan

The following sections provide a comprehensive technical framework for implementing these analyses, with specialized consideration for ASD research applications.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Spatial Multi-Omic Profiling of Brain Development

Spatial ARP-Seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin–RNA–Protein Sequencing) enables simultaneous genome-wide profiling of chromatin accessibility, whole transcriptome, and proteome (approximately 150 proteins) within the same tissue section at cellular level [32].

Protocol Workflow:

- Tissue Preparation: Collect frozen brain sections (10-20μm thickness) and fix with formaldehyde

- Antibody Incubation: Incubate with cocktail of antibody-derived DNA tags (ADTs) targeting proteins of interest

- Tagmentation: Treat with Tn5 transposase loaded with universal ligation linker to insert adapters at accessible genomic loci

- Reverse Transcription: Incubate with biotinylated poly(T) adapter to bind poly(A) tails of mRNAs and ADTs for in-tissue reverse transcription

- Spatial Barcoding: Apply microfluidic channel array chips with perpendicular channels to introduce spatial barcodes Ai (i=1-100/220) and Bj (j=1-100/220), forming a 2D grid of spatially barcoded tissue pixels (15-20μm resolution)

- Library Preparation: Separate barcoded cDNAs (from mRNAs and ADTs) and genomic DNA fragments for next-generation sequencing library construction

- Data Integration: Align and integrate epigenomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data using spatial coordinates

Spatial CTRP-Seq (CUT&Tag–RNA–Protein Sequencing) provides simultaneous measurement of genome-wide histone modifications, transcriptome, and proteins following a similar workflow but utilizing an antibody against H3K27me3 followed by protein-A-tethered Tn5–DNA complex to perform cleavage under targets and tagmentation (CUT&Tag) [32].

Deep Learning-Based Prediction of Spatial Gene Expression

GHIST Framework predicts spatial gene expression at single-cell resolution from histology images using a multitask deep learning architecture [33].

Implementation Protocol:

- Input Processing: Segment H&E-stained whole slide images into individual cell nuclei using automated segmentation algorithms

- Feature Extraction: Extract morphological features from each nucleus (size, shape, texture) and tissue architecture features from local neighborhoods

- Multitask Architecture: Implement four interconnected prediction heads:

- Cell type prediction head

- Neighborhood composition prediction head

- Cell nucleus morphology prediction head

- Single-cell RNA expression prediction head

- Loss Functions: Apply combined loss function incorporating:

- Cell-type classification loss (categorical cross-entropy)

- Neighborhood composition loss (mean squared error)

- Gene expression prediction loss (mean squared error on highly variable genes)

- Training Regimen: Train on samples with paired H&E and subcellular spatial transcriptomics (SST) data, with transfer learning from single-cell RNA-seq reference atlases

- Validation: Assess prediction accuracy using spatially variable genes (SVGs) and correlation with ground truth expression (target: median r>0.6 for top 50 SVGs)

Connectivity-Transcriptome Integration Analysis

Leading Eigenvector Dynamics Analysis (LEiDA) captures transient brain states from resting-state fMRI for correlation with transcriptomic signatures [34].

Analytical Pipeline:

- fMRI Preprocessing: Remove initial 5 time points for signal stabilization, apply head motion correction, slice timing correction, spatial normalization to MNI space, and smoothing with Gaussian kernel

- Dynamic State Identification: Calculate instantaneous phase-locking patterns of BOLD signals at each time point without sliding windows

- Clustering: Apply k-means clustering (typically k=10) to leading eigenvectors to identify recurrent brain states

- Dynamic Metrics Calculation: For each state, compute:

- Occupancy rate (percentage of time points)

- Dwell time (consecutive time points in same state)

- Transition probabilities between states

- Gene Expression Enrichment: Integrate spatial maps of altered brain states with regional gene expression data from Allen Human Brain Atlas using spin permutation testing for statistical robustness

Data Presentation and Quantitative Findings

Spatial Transcriptomic Signatures of Brain Development

Table 1: Developmental Trajectory of Key Cell-Type Markers in Mouse Brain (P0-P21)

| Marker | Cell Type | P0 Expression | P21 Expression | Spatial Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CUX1/2 | Upper layer neurons | Widespread in cortex | Restricted to layers II/III/IV | Cortical layer specification |

| CTIP2 | Deep layer neurons | Widespread in cortex | Restricted to layers V/VI | Inside-out patterning |

| MBP | Mature oligodendrocytes | Absent | Abundant in corpus callosum | Lateral-to-medial myelination progression |

| MOG | Mature oligodendrocytes | Absent | Limited to lateral CC | Myelination initiation sites |

| GFAP | Astrocytes/neural progenitors | Glial limitans and ventricular zones | Expanded parenchymal distribution | Radial expansion from niches |

| OLIG2 | Pan-oligodendrocyte | Sparse distribution | Enriched in white matter tracts | Progressive localization |

Connectivity-Transcriptome Correlations in Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Table 2: Transcriptomic Signatures Associated with Functional Connectivity Alterations in ASD

| Connectivity Phenotype | Associated Gene Sets | Biological Processes | Enrichment FDR | Clinical Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortico-striatal hyperconnectivity | mTOR pathway, Tsc2-interacting genes | Synaptic pruning, spine density regulation | <0.001 | Stereotypy severity [30] |

| Frontoparietal-DMN hyperconnectivity | Neuron projection genes | Axon guidance, synaptic transmission | 0.003 | Autism symptom severity [31] |

| Attention-salience-DMN synchronization | Glycine-mediated synaptic pathways | Excitatory-inhibitory balance | 0.008 | Cognitive performance [34] |

| Global functional hyperconnectivity | ASD-dysregulated genes | Transcriptional regulation, chromatin remodeling | 0.002 | Social communication deficits [30] |

Performance Metrics of Spatial Gene Expression Prediction

Table 3: GHIST Prediction Accuracy Across Brain Regions and Cell Types

| Evaluation Metric | Performance Value | Technical Notes | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-type accuracy | 0.66-0.75 (multi-class) | 8 major brain cell types | 25-40% improvement over spot-based methods |

| SVG correlation (top 20) | Median r=0.7 | Spatially variable genes | Maintains spatial expression patterns |

| SVG correlation (top 50) | Median r=0.6 | Biologically meaningful genes | Captures fine-grained cellular variation |

| Non-SVG correlation | r=0-0.1 | Low-expressed genes | Avoids false positive predictions |

| Architecture flexibility | Multiple resolutions | Single-cell to spot-based | Compatible with diverse dataset types |

Visualization Approaches

Integrated Workflow for Connectivity-Transcriptome Mapping

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for mapping brain connectivity to gene expression.

GHIST Deep Learning Architecture for Gene Prediction

Diagram 2: GHIST architecture for predicting gene expression from histology.

Core Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for In Silico Spatial Transcriptomics

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Application | Key Features | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Omics Technologies | DBiT-seq, 10x Visium, 10x Xenium, CODEX | Multi-omic spatial profiling | Simultaneous RNA-protein-epigenome, subcellular resolution | Commercial and academic platforms |

| Reference Brain Atlases | Allen Human Brain Atlas, BrainSpan, PsychENCODE | Transcriptomic reference data | Brain-wide gene expression, developmental trajectories | Publicly available |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | GHIST, ST-Net, Hist2ST | Gene expression prediction | Single-cell resolution from histology | Open-source implementations |

| Connectivity Analysis Tools | LEiDA, CONN, FSL | Dynamic functional connectivity | Data-driven brain states, network metrics | Open-source toolboxes |

| Integration & Visualization | Cytosplore, Brain Explorer | Multi-scale data integration | 3D spatial visualization, cellular hierarchies | Academic licenses |

Applications in Autism Systems Biology

The integration of connectivity patterns with transcriptomic landscapes has yielded critical insights into ASD pathophysiology. Research has demonstrated that cortico-striatal hyperconnectivity in ASD is spatially correlated with genes interacting with mTOR pathway components, mechanistically linking synaptic pathology to macroscale network dysfunction [30]. Furthermore, transcriptomic enrichment analyses of functional connectivity maps associated with autism symptoms have identified genes involved in neuron projection and known to have greater rates of variance in both ASD and ADHD [31].

These integrative approaches enable stratification of ASD into biologically distinct subtypes based on the alignment between individual connectivity patterns and specific transcriptomic signatures. This stratification has revealed that the transcriptomic signature associated with mTOR-related hyperconnectivity is predominantly expressed in a subset of children with autism, thereby defining a segregable autism subtype with distinct molecular and network-level features [30].

In silico spatial transcriptomics provides an unprecedented framework for mapping brain connectivity patterns onto gene expression landscapes, offering powerful insights into the multi-scale organization of typical and atypical neurodevelopment. The methodologies outlined in this technical guide—from spatial multi-omic sequencing to deep learning-based prediction and connectivity-transcriptome integration—empower researchers to bridge the conceptual and analytical divide between genes and networks.

For autism systems biology specifically, these approaches reveal not only disease-associated alterations but also the fundamental principles governing how molecular diversity gives rise to functional specialization across brain networks. Future methodological advances will likely focus on enhanced spatial resolution, dynamic profiling of gene expression across development, and the integration of additional data modalities including proteomics, metabolomics, and comprehensive electrophysiological recordings. As these technologies mature, they will progressively transform our understanding of neurodevelopmental disorders from descriptive phenomenology to mechanistic, predictable models of brain pathophysiology.

The application of network controllability analysis represents a paradigm shift in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) research, moving beyond singular gene discovery toward understanding system-level regulatory mechanisms. ASD is characterized by substantial genetic heterogeneity, with an estimated 1 in 59 children affected and heritability estimates ranging from 40-80% [35]. The traditional focus on coding regions, which constitute merely 1.5% of the human genome, has limited comprehensive understanding of ASD's complex etiology [36]. Network controllability frameworks address this limitation by examining how specific "driver" genes and master regulators orchestrate broader transcriptional programs that shape neural circuit development and function.

The fundamental premise of network controllability in neural systems biology posits that certain genes exert disproportionate influence over neurodevelopmental trajectories and functional connectivity patterns. Recent research has revealed that ASD risk genes predominantly converge into two primary functional classes: proteins involved in synapse formation and those governing transcriptional regulation and chromatin-remodeling pathways [35]. By reconstructing transcriptional networks from brain transcriptomic data, researchers can identify critical control points whose dysregulation may cascade through developmental processes, ultimately manifesting as ASD-associated neural connectivity patterns and clinical symptoms.

Methodological Framework for Network Controllability Analysis

Transcriptional Network Deconvolution

The identification of master regulators begins with transcriptional network deconvolution, a computational approach that distinguishes direct regulatory interactions from indirect correlations. The Algorithm for Reconstruction of Accurate Cellular Networks (ARACNe) has emerged as a cornerstone method for this purpose [37]. ARACNe employs mutual information (MI) to quantify gene-gene co-regulatory patterns, subsequently pruning the constructed network to remove indirect connections where two genes are co-regulated through one or more intermediaries. This process typically utilizes a stringent statistical threshold (P value of 10-8) to establish confidence in regulatory relationships, yielding networks comprising hundreds of thousands of interactions among thousands of regulators and targets [37].

Following network construction, the Virtual Inference of Protein-activity by Enriched Regulon analysis (VIPER) algorithm systematically infers protein activity by analyzing expression patterns of target genes (regulons) [37]. Unlike conventional enrichment methods, VIPER integrates target mode of regulation (activation or repression), statistical confidence in regulator-target interactions, and target overlap between different regulators. This approach enables robust identification of master regulators whose dysregulation significantly impacts downstream transcriptional networks in ASD. The complete workflow from sample processing to master regulator validation is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for identifying master regulators in ASD through transcriptional network analysis, integrating computational and experimental approaches.

Connectome-Based Symptom Mapping

Complementing transcriptional network analysis, connectome-based symptom mapping links neural circuit connectivity patterns with specific symptom dimensions across diagnostic categories. This approach employs resting-state functional MRI (R-fMRI) to measure intrinsic functional connectivity (iFC) across the brain [38]. Participants undergo rigorous phenotyping, including clinician-administered assessments such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-2nd Edition (ADOS-2) and cognitive testing, followed by multimodal neuroimaging data acquisition using standardized protocols [38].

Advanced analytical frameworks, including multivariate distance matrix regression, identify transdiagnostic associations between functional connectivity and symptom severity. This method examines internetwork connectivity, particularly between the frontoparietal (FP) and default-mode (DM) networks, which support social cognition and executive functions [38]. Genetic enrichment analyses then map these neural connectivity patterns against spatial gene expression databases to identify candidate genes whose expression correlates with ASD-relevant connectivity phenotypes, creating an integrative bridge between macro-scale circuit function and molecular genetics.

Key Findings in ASD Network Controllability

Identification of Master Regulators

Transcriptional network analysis of post-mortem cerebellar tissue from ASD patients and controls has identified PPP1R3F (Protein Phosphatase 1 Regulatory Subunit 3F) as a prominent master regulator in ASD pathogenesis [37]. This gene demonstrated significant downregulation in two independent datasets (FDR: 0.029 and 3.58×10-4) and its regulons showed significant overlap with established ASD gene databases, including SFARI genes (P = 8×10-4) [37]. As a regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 1, PPP1R3F modulates diverse signaling pathways, including the TGF-ß cascade, and has documented importance in neuronal function [37]. A rare non-synonymous variant (c.733T>C) in PPP1R3F was previously identified in a male with Asperger syndrome, transmitted from a mother with learning disabilities and seizures [37].

Pathway analysis of PPP1R3F targets revealed significant alterations in endocytosis pathway function, suggesting a mechanism through which this master regulator may influence synaptic signaling and neural circuit development in ASD [37]. Importantly, the regulatory role of PPP1R3F remained significant when analyzing only male samples, indicating its effects are independent of sex-based gene expression differences that often complicate ASD genetics research.

Data-Driven ASD Subtypes and Their Genetic Correlates

Recent large-scale analyses have identified four clinically and biologically distinct ASD subtypes through data-driven decomposition of phenotypic heterogeneity, as summarized in Table 1 [4]. This research analyzed over 5,000 children from the SPARK cohort, considering more than 230 traits to define subgroups with distinct genetic architectures and developmental trajectories.

Table 1: Clinically and Biologically Distinct Subtypes of Autism Spectrum Disorder

| Subtype Name | Prevalence | Clinical Characteristics | Genetic Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social and Behavioral Challenges | 37% | Core ASD traits without developmental delays; high rates of ADHD, anxiety, depression, OCD | Mutations in genes active later in childhood |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | 19% | Developmental delays in walking/talking; variable repetitive behaviors and social challenges | Rare inherited genetic variants |

| Moderate Challenges | 34% | Milder core ASD symptoms; no co-occurring psychiatric conditions | Not specified in study |

| Broadly Affected | 10% | Severe, wide-ranging challenges including developmental delays and multiple psychiatric conditions | Highest burden of damaging de novo mutations |

The identification of these subtypes represents a crucial advance for network controllability analysis, as each subgroup demonstrates distinct genetic architectures and developmental trajectories [4]. For instance, the Broadly Affected subgroup carries the highest burden of damaging de novo mutations, while the Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay subgroup shows enrichment for rare inherited variants. Notably, the Social and Behavioral Challenges subgroup exhibits mutations in genes that become active later in childhood, suggesting a post-natal developmental timeline for the biological mechanisms underlying their symptoms [4].

Transdiagnostic Connectivity-Symptom Relationships

Connectome-based mapping has revealed that autism symptom severity—rather than categorical diagnosis—correlates with specific patterns of brain connectivity that align with spatial gene expression profiles. Across children with ASD and those with ADHD without autism, increased connectivity between the middle frontal gyrus of the frontoparietal network and the posterior cingulate cortex of the default-mode network associates with more severe autism symptoms [38]. This relationship persists after controlling for ADHD symptoms, suggesting specificity to the autism dimension.

Genetic enrichment analyses demonstrate that these symptom-associated connectivity patterns align with cortical expression of genes implicated in both ASD and ADHD, particularly those involved in neuron projection and neural development [38]. This transdiagnostic approach reveals shared biological underpinnings for autistic symptoms across traditional diagnostic boundaries, highlighting the value of dimensional frameworks for understanding the neurobiology of neurodevelopmental conditions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Network Controllability Analysis