Machine Learning Decodes Autism Heterogeneity: A New Framework for Biologically Distinct ASD Subtypes and Precision Medicine

This article synthesizes the latest breakthroughs in machine learning (ML) for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) subtyping, a pivotal shift from behavior-based to biology-driven classification.

Machine Learning Decodes Autism Heterogeneity: A New Framework for Biologically Distinct ASD Subtypes and Precision Medicine

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest breakthroughs in machine learning (ML) for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) subtyping, a pivotal shift from behavior-based to biology-driven classification. We explore how novel computational approaches are deconstructing ASD's clinical heterogeneity into distinct subtypes with unique genetic profiles, developmental trajectories, and neurobiological mechanisms. For researchers and drug development professionals, the review details methodological advances in interpretable ML and data integration, addresses critical challenges in model optimization and clinical translation, and validates these approaches through comparative performance analysis. The synthesis points toward a future of precision medicine in autism, where subtype-specific diagnostics and targeted interventions become a reality.

Deconstructing Heterogeneity: How ML Reveals Biologically Distinct Autism Subtypes

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) has historically been treated as a singular diagnostic category despite considerable heterogeneity in its clinical presentation. Traditional diagnostic frameworks like the DSM-5 have categorized ASD as a spectrum disorder, encompassing what were previously considered distinct conditions such as autistic disorder, Asperger syndrome, and pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) [1] [2]. While this unified approach acknowledged the diversity of symptoms, it provided limited utility for predicting individual outcomes, guiding targeted interventions, or understanding underlying biological mechanisms.

The emergence of data-driven methodologies, particularly machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI), is now catalyzing a paradigm shift in autism research. By analyzing complex, multi-dimensional datasets, researchers are moving beyond symptom-based descriptions to identify biologically distinct subtypes of autism. This transformation enables a more precise understanding of ASD's etiology, paving the way for personalized diagnostic approaches and targeted therapeutic strategies [3] [4]. This article outlines the key applications, experimental protocols, and analytical frameworks driving this revolution in ASD subtyping.

Key Applications of Machine Learning in ASD Subtyping

Identification of Clinically Distinct Subtypes

Recent large-scale studies have demonstrated the power of computational approaches to decompose ASD heterogeneity into biologically meaningful subgroups. A landmark 2025 study analyzing data from over 5,000 children in the SPARK cohort identified four clinically and biologically distinct subtypes of autism using a "person-centered" approach that considered over 230 traits per individual [4].

Table 1: Data-Driven ASD Subtypes Identified in the SPARK Cohort Study

| Subtype Name | Prevalence | Core Clinical Features | Developmental Milestones | Common Co-occurring Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social and Behavioral Challenges | 37% | Social challenges, repetitive behaviors | Typically reached on schedule | ADHD, anxiety, depression, OCD |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | 19% | Variable social/repetitive behavior profiles | Delayed achievement | Generally absent |

| Moderate Challenges | 34% | Milder core ASD behaviors | Typically reached on schedule | Generally absent |

| Broadly Affected | 10% | Severe social difficulties, repetitive behaviors | Delayed achievement | Anxiety, depression, mood dysregulation |

This research revealed that these subtypes not only represent different clinical presentations but also correlate with distinct genetic profiles and developmental trajectories. For instance, individuals in the "Broadly Affected" subgroup showed the highest proportion of damaging de novo mutations, while only the "Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay" group was more likely to carry rare inherited genetic variants [4].

Behavioral Severity Classification

Complementing the subtyping approach, researchers have developed ML frameworks that classify ASD based on behavioral severity across multiple dimensions. One study published in Scientific Reports dissected ASD into its behavioral components using the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) domains—Communication, Mannerism, Cognition, Motivation, and Awareness [3]. The researchers utilized morphological features extracted from MRI scans to identify cortical regions associated with specific behavioral manifestations, achieving an impressive 96% average accuracy in classifying subjects based on their severity level (TD, mild, moderate, or severe) within each behavioral category [3].

Table 2: Machine Learning Approaches in ASD Classification Studies

| Study Focus | Data Source | Sample Size | ML Methods | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASD Subtype Classification | SPARK Cohort | 5,000+ individuals | Computational clustering | Subtype-specific genetic correlations |

| Behavioral Severity Classification | ABIDE II | 521 ASD, 593 TD | Multivariate feature selection, multiple classifiers | 96% mean accuracy across behavioral domains |

| DSM-IV Disorder Classification | Retrospective clinical data | 38,560 individuals | Not specified | AUROCs 0.863-0.980; 80.5% correct classification |

| Interpretable ASD Detection | Multiple behavioral datasets | Various | Rule-based classifiers (RIPPER, decision trees) | Transparent models with good accuracy |

Interpretable Classification for Clinical Translation

The clinical translation of ML models requires not only accuracy but also interpretability. Rule-based classifiers and decision trees offer transparent decision-making processes that clinicians can understand and validate [5]. These algorithms generate human-readable "if-then" rules that highlight key behavioral features and their interactions contributing to ASD classification. Recent research has demonstrated that interpretable classifiers can achieve competitive accuracy while providing crucial diagnostic insights, making them particularly valuable for clinical settings where model transparency is as important as predictive performance [5].

Experimental Protocols for ASD Subtype Classification

Comprehensive Data Collection and Preprocessing

Purpose: To assemble a multidimensional dataset capturing clinical, behavioral, and biological characteristics of individuals with ASD.

Materials:

- Clinical assessment tools (ADOS, ADI-R, SRS)

- Neuroimaging data (structural MRI)

- Genetic sequencing data

- Demographic and medical history information

Procedure:

- Participant Recruitment: Recruit a large, diverse cohort of individuals with ASD and typically developing controls. The SPARK study exemplifies this approach with over 5,000 participants [4].

- Phenotypic Characterization: Administer comprehensive behavioral assessments covering social communication, repetitive behaviors, cognitive functioning, and adaptive skills. Collect information on co-occurring medical and psychiatric conditions.

- Biological Data Collection: Obtain genetic material for sequencing and neuroimaging data where available.

- Data Integration: Create a unified dataset with standardized variables across all domains, addressing missing data through appropriate imputation methods.

Feature Selection and Dimensionality Reduction

Purpose: To identify the most discriminative features that differentiate ASD subtypes while reducing computational complexity.

Procedure:

- Initial Feature Pool: Compile all potential features from clinical, behavioral, and biological domains.

- Multivariate Feature Selection: Apply algorithms that evaluate feature importance while considering interactions between variables.

- Iterative Refinement: Repeatedly apply feature selection methods while shuffling training-validation subjects to identify features with statistically significant associations with ASD subtypes [3].

- Validation: Confirm the stability of selected features across multiple iterations and subsamples.

Machine Learning Model Development and Validation

Purpose: To develop accurate classifiers for assigning individuals to ASD subtypes.

Procedure:

- Algorithm Selection: Choose appropriate ML algorithms based on data characteristics and research questions. Options include:

- Model Training: Partition data into training and validation sets using k-fold cross-validation (typically 5-fold).

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Optimize model parameters using grid search or Bayesian optimization.

- Performance Evaluation: Assess model performance using metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC).

- Biological Validation: Where possible, validate identified subtypes by examining their association with distinct genetic profiles or neurobiological markers [4].

Table 3: Key Research Resources for ASD Subtype Classification Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Assessment Tools | ADOS, ADI-R, SRS, SCQ | Standardized measurement of ASD symptoms and severity |

| Genetic Databases | SFARI Gene Database, SPARK cohort | Provide genetic data and associated phenotypic information |

| Neuroimaging Repositories | ABIDE I & II, NDAR | Source of structural and functional brain imaging data |

| Machine Learning Libraries | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Implement classification and clustering algorithms |

| Rule-Based Classifiers | RIPPER, Decision Trees, CAR | Generate interpretable models for clinical translation |

| Feature Selection Algorithms | Multivariate feature selection, recursive feature elimination | Identify most discriminative features for subtype classification |

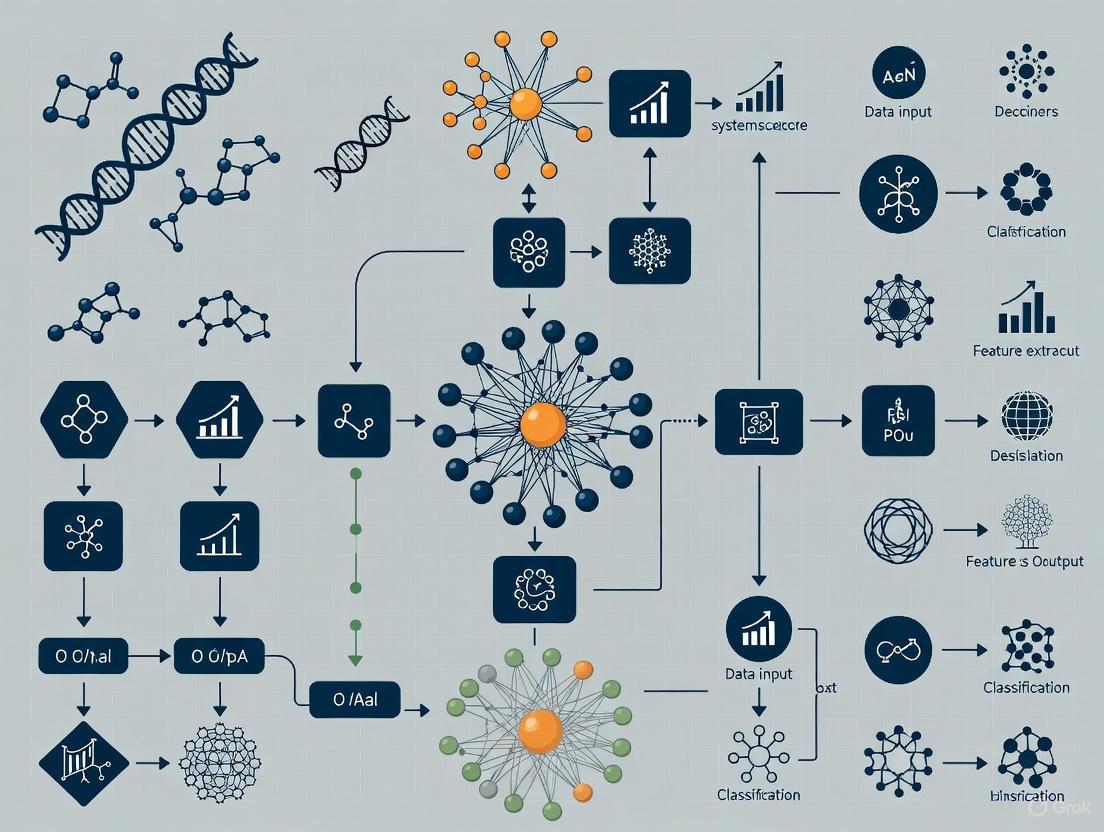

Visualizing Analytical Workflows

ASD Subtype Classification Framework

Rule-Based Classification for Clinical Translation

The paradigm shift from a unitary autism spectrum to data-driven subtypes represents a transformative advancement in autism research with profound implications for clinical practice and therapeutic development. By leveraging machine learning approaches to integrate multidimensional data—encompassing clinical, behavioral, genetic, and neurobiological domains—researchers are now identifying biologically distinct subtypes of ASD that correlate with different genetic profiles, developmental trajectories, and clinical outcomes [3] [4].

This refined understanding of autism heterogeneity enables more precise diagnostic approaches, potentially leading to earlier identification and more targeted interventions. For drug development professionals, these subtypes provide a framework for developing therapies that target specific biological pathways rather than attempting to address the entire spectrum with a one-size-fits-all approach [4]. The integration of interpretable ML models further facilitates clinical translation by providing transparent decision-making processes that clinicians can understand and trust [5].

As these data-driven approaches continue to evolve, they promise to unravel the complex etiology of ASD, paving the way for truly personalized medicine in autism diagnosis and treatment. The methodological frameworks outlined in this article provide a foundation for researchers to build upon this emerging paradigm and contribute to the growing understanding of autism heterogeneity.

This document details the foundational methodology and key findings from the landmark 2025 study, "Decomposition of phenotypic heterogeneity in autism reveals underlying genetic programs," published in Nature Genetics [4] [6]. The research represents a paradigm shift in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) research by successfully linking clinically distinct phenotypic subgroups to their unique underlying genetic architectures using a person-centered computational approach.

The study analyzed extensive phenotypic and genetic data from over 5,000 children with ASD from the SPARK cohort, the largest autism study to date [4] [7]. By employing a generative finite mixture model, the researchers identified four robust ASD subtypes characterized by distinct developmental trajectories, medical profiles, and co-occurring conditions. Crucially, these phenotypic classes were mapped onto specific genetic programs, offering unprecedented insights into the biological mechanisms driving ASD heterogeneity. This work provides a new data-driven framework for precision medicine in autism, with the potential to transform diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic development [4] [6].

Table 1: Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Four ASD Subtypes

| Subtype Name | Approximate Prevalence | Core Clinical Presentation | Common Co-occurring Conditions | Developmental Milestones | Average Age at Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social and Behavioral Challenges | 37% | Significant social challenges and repetitive behaviors [4]. | High rates of ADHD, anxiety, depression, and mood dysregulation [4]. | Typically on pace with children without autism [4]. | Later diagnosis, aligning with post-birth genetic activity [4] [7]. |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | 19% | Mixed profile of social and repetitive behaviors with significant developmental delays [4]. | Generally absent of anxiety, depression, or disruptive behaviors [4]. | Walking and talking achieved later than peers [4]. | Earlier diagnosis [6]. |

| Moderate Challenges | 34% | Core ASD behaviors present but less pronounced than other groups [4]. | Generally absent of co-occurring psychiatric conditions [4]. | Typically on pace [4]. | Not specified. |

| Broadly Affected | 10% | Widespread and severe challenges across all core and associated domains [4]. | High levels of anxiety, depression, mood dysregulation, and intellectual disability [4] [6]. | Significant developmental delays [4]. | Earlier diagnosis [6]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Person-Centered Phenotypic Class Identification

Objective: To identify robust, clinically relevant subtypes of ASD by modeling the full spectrum of traits in individuals simultaneously, rather than analyzing single traits in isolation [4] [6].

Materials:

- Phenotypic data from 5,392 individuals with ASD from the SPARK cohort [6].

- 239 item-level and composite features from standardized instruments: Social Communication Questionnaire-Lifetime (SCQ), Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R), and Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [6].

- Background history forms detailing developmental milestones.

Methodology:

- Data Integration: Consolidate the 239 heterogeneous features (continuous, binary, and categorical) into a unified dataset for analysis [6].

- Generative Finite Mixture Modeling (GFMM): Apply a GFMM to the integrated dataset. This model was selected for its ability to handle different data types without strong statistical assumptions and its person-centered approach [7] [6].

- Model Selection: Train models with 2 to 10 latent classes. The four-class model was selected based on an optimal balance of statistical fit metrics (e.g., Bayesian Information Criterion) and clinical interpretability [6].

- Validation and Replication:

- Internal Validation: Analyze class stability against data perturbations [6].

- External Validation: Correlate class assignments with medical history data (e.g., diagnoses of ADHD, intellectual disability) not used in the original model [6].

- Independent Replication: Apply the model to an independent, deeply phenotyped cohort (Simons Simplex Collection, n=861) to confirm the generalizability of the four-class structure [8] [6].

Protocol 2: Genetic Analysis of ASD Subtypes

Objective: To determine if the phenotypically defined subtypes have distinct underlying genetic profiles and to identify the specific biological pathways and developmental timing associated with each subtype [4] [6].

Materials:

- Whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing data from participants in the SPARK cohort.

- Class assignments from Protocol 1.

- Bioinformatics tools for pathway analysis (e.g., GO, KEGG, Reactome).

Methodology:

- Variant Burden Analysis: Compare the burden of different genetic variant types across the four subtypes. This includes:

- Pathway Enrichment Analysis: For each subtype, aggregate the genes carrying significant mutations and test for enrichment in specific biological pathways (e.g., neuronal signaling, chromatin remodeling) [4] [7].

- Developmental Gene Expression Analysis: Map the identified subtype-specific genes to public databases of gene expression across brain development (e.g., BrainSpan) to determine the prenatal or postnatal periods when these genes are most active [4] [6].

Table 2: Distinct Genetic Profiles and Pathways of ASD Subtypes

| Subtype Name | Key Genetic Findings | Enriched Biological Pathways | Developmental Timing of Gene Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social and Behavioral Challenges | Not specified. | Neuronal action potentials; postsynaptic signaling [7]. | Predominantly postnatal activity of impacted genes [4] [7]. |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | Higher burden of rare inherited genetic variants [4]. | Chromatin organization; transcriptional regulation [7]. | Predominantly prenatal activity of impacted genes [4] [7]. |

| Moderate Challenges | Not specified. | Not specified. | Not specified. |

| Broadly Affected | Highest burden of damaging de novo mutations [4]. | Multiple pathways implicated in severe neurodevelopmental disruption [4]. | Not specified. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for Replication and Extension

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| SPARK Cohort Data | Primary source of matched phenotypic and genotypic data at scale. Provides the statistical power for person-centered subtyping. | Simons Foundation Powering Autism Research for Knowledge (SPARK) [4] [7]. |

| Simons Simplex Collection (SSC) | Independent, deeply phenotyped cohort used for validation and replication of findings. | Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI) [8] [6]. |

| Generative Finite Mixture Model (GFMM) | Core computational algorithm for integrating heterogeneous data types and identifying latent classes in a person-centered manner. | Custom implementation as described in the primary study [6]. |

| Bioinformatics Pathway Databases | For functional annotation and enrichment analysis of subtype-specific gene sets. | Gene Ontology (GO), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) [4]. |

| BrainSpan Atlas | Publicly available dataset of human brain development transcriptomes. Used to map subtype genes to critical developmental periods. | Allen Institute for Brain Science [4] [6]. |

| Standardized Phenotypic Instruments | Gold-standard behavioral assessments that provide the raw data for phenotypic modeling. | Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ), Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R), Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [6]. |

This application note details a framework for integrating molecular subtyping with the distinct genetic architectures of de novo and inherited variants in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). The high heritability of ASD, coupled with its profound clinical heterogeneity, presents a significant challenge for both research and therapeutic development [9]. The "one-size-fits-all" model of ASD is being superseded by a more nuanced understanding that links specific genetic risk factors to biologically and clinically distinct subgroups [4]. This paradigm shift is essential for developing precision medicine approaches, where diagnostics, prognostics, and treatments can be tailored to an individual's specific ASD subtype.

Central to this framework is the recognition that de novo and inherited variants not only differ in their origin but also implicate different biological pathways, have varying effect sizes, and are associated with distinct developmental and clinical trajectories [10] [11] [12]. De novo variants, which are new mutations in the proband not found in either parent, are typically associated with more severe phenotypic presentations and are a major contributor to simplex ASD cases (where only one individual in a family is affected) [13]. Inherited variants, conveyed from parents to offspring, often have lower penetrance and are a key component of the genetic architecture in multiplex families (with multiple affected individuals) [11]. A landmark study analyzing over 5,000 individuals from the SPARK cohort identified four clinically and biologically distinct subtypes of autism, providing a robust data-driven structure for this new paradigm [4].

The integration of machine learning (ML) with large-scale genomic and phenotypic data is pivotal for deconvoluting this complexity. ML models can parse high-dimensional data to identify reproducible subtypes and map the unique genetic correlates of each [4] [3]. This enables a move away from grouping all individuals with ASD together in genetic analyses, which can obscure meaningful signals, towards a stratified approach where genetic discoveries are contextualized within specific subtypes. For drug development, this means therapeutic targets can be prioritized based on their relevance to a defined patient subgroup, thereby increasing the likelihood of clinical trial success. This note provides a detailed protocol for implementing this integrated analysis, from sample processing to data interpretation.

The genetic architecture of ASD is now understood to comprise a spectrum of variants, including de novo and rare inherited mutations with substantial effects, as well as common polygenic risk factors [9]. The contribution of de novo variants has been particularly well-characterized in recent years, with large-scale sequencing studies identifying over 100 high-confidence ASD risk genes enriched for likely deleterious de novo mutations [10]. These de novo variants, which can be loss-of-function (LoF) or damaging missense mutations, are a primary focus in simplex families and are estimated to explain a population attributable risk (PAR) of about 10% [10]. Notably, one recent trio whole-genome sequencing (trio-WGS) study reported that principal diagnostic de novo variants were present in 47-50% of the clinically evaluated ASD patients in their cohort, highlighting their significant role [13].

In contrast, inherited risk has been more elusive to define. While recurrent copy-number variants are an established form of inherited risk, the identification of specific genes enriched for rare inherited LoF variants has been challenging due to their lower penetrance and smaller effect sizes [10] [11]. However, studies focusing on multiplex families, which are enriched for inherited risk, have begun to successfully implicate new genes. For instance, one analysis of 42,607 autism cases identified new moderate-risk genes like NAV3, where the association with autism risk was primarily driven by rare inherited LoF variants [10]. Furthermore, biological pathways enriched for genes harboring inherited variants (e.g., cytoskeletal organization and ion transport) appear to be distinct from those implicated by de novo variation, suggesting a broader and more diverse pathophysiological landscape [11].

Crucially, these different genetic architectures are not randomly distributed across the autistic population but are linked to specific, data-driven subtypes. The recent subtyping of ASD into four distinct categories provides a clear clinical and biological framework, as shown in Table 1 [4].

Table 1: Association of Genetic Variants with Data-Driven ASD Subtypes

| ASD Subtype | Prevalence in SPARK Cohort | Key Clinical Characteristics | Associated Genetic Architecture |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social & Behavioral Challenges | ~37% | Core autism traits; typical developmental milestones; high co-occurrence of ADHD, anxiety, OCD. | Mutations in genes active later in childhood [4]. |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | ~19% | Later achievement of developmental milestones (e.g., walking, talking); absence of anxiety/depression. | Enriched for rare inherited genetic variants [4]. |

| Moderate Challenges | ~34% | Milder core autism traits; typical developmental milestones; low rate of co-occurring conditions. | Information not specified in search results. |

| Broadly Affected | ~10% | Severe, wide-ranging challenges including developmental delays, core deficits, and psychiatric conditions. | Highest burden of damaging de novo mutations [4]. |

This stratification demonstrates a direct link between variant origin and clinical outcome. For example, the "Broadly Affected" subtype carries the highest burden of damaging de novo mutations, consistent with the large effect size and penetrance of these variants. Conversely, the "Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay" subtype is uniquely enriched for rare inherited variants [4]. This biological divergence underscores the necessity of subtype-specific research protocols.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cohort Selection and Phenotypic Subtyping

Objective: To recruit a well-characterized cohort of ASD individuals and classify them into data-driven subtypes using a comprehensive phenotypic profile.

Background: Accurate subtyping is the foundational step that enables the subsequent discovery of distinct genetic associations. This protocol uses a "person-centered" approach that considers a broad range of traits rather than searching for genetic links to single traits [4].

Materials:

- Cohort of participants with ASD (e.g., from SPARK, AGRE).

- Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval and informed consent.

- Standardized behavioral assessments (e.g., SRS, ADOS, ADI-R, VABS).

- Clinical and developmental history questionnaires.

- Computational resources for machine learning.

Procedure:

- Cohort Recruitment: Recruit a large cohort of ASD individuals, ensuring diverse representation in sex, ancestry, and clinical severity. Secure informed consent and collect demographic information.

- Phenotypic Data Collection: For each participant, gather data on over 230 traits across multiple domains [4]. Essential domains include:

- Social Communication and Interaction: Use tools like the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) [3] or ADOS.

- Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors: Assessed via ADOS or specific subscales.

- Developmental Milestones: Age at first words, independent walking.

- Cognitive Functioning: IQ or developmental quotient.

- Co-occurring Conditions: Screen for ADHD, anxiety, depression, intellectual disability, and mood dysregulation.

- Data Preprocessing: Clean and normalize the collected phenotypic data. Handle missing values using appropriate imputation methods.

- Subtype Identification: Apply a computational model, such as a community detection algorithm, to group individuals based on their combinations of traits. This unsupervised learning approach identifies latent subgroups without a priori labels [4].

- Subtype Validation: Characterize the resulting subtypes by their distinct clinical profiles, as exemplified in Table 1. Validate the stability and reproducibility of the subtypes using bootstrapping or in an independent cohort.

Protocol 2: Genomic Sequencing and Variant Calling

Objective: To generate high-quality genomic data from probands and parents (trios) to identify both de novo and inherited rare variants.

Background: Trio whole-genome sequencing (WGS) is the gold standard for comprehensively detecting all variant types. Exome sequencing can be a cost-effective alternative for focusing on coding regions [13] [11].

Materials:

- DNA samples from proband and both biological parents.

- Whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing services.

- High-performance computing cluster.

- Bioinformatic pipelines (e.g., GATK, LOFTEE, ANNOVAR).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation and Sequencing: Extract high-molecular-weight DNA from blood or saliva. Prepare sequencing libraries and perform high-coverage (e.g., >30x) WGS or exome capture on an Illumina or equivalent platform.

- Primary Data Processing: Align raw sequencing reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using aligners like BWA-MEM. Perform base quality score recalibration and indel realignment.

- Variant Calling: Call single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions/deletions (indels) using a variant caller such as GATK HaplotypeCaller in GVCF mode. Call copy number variants (CNVs) using tools like Canvas or Manta.

- Variant Annotation: Annotate variants using databases like gnomAD (for population frequency), LOFTEE (for loss-of-function consequence), and REVEL (for missense pathogenicity) [10]. Integrate gene constraint metrics such as pLI and LOEUF.

- De Novo Variant Calling: Use trio-aware variant callers (e.g., DeNovoGear, GATK's FamilyCaller) to identify high-confidence de novo variants. Apply stringent filters for sequencing quality, Mendelian transmission errors, and presence in multiple family members.

Protocol 3: Subtype-Specific Genetic Burden Analysis

Objective: To test for the enrichment of de novo and rare inherited variants within each predefined ASD subtype.

Background: This protocol tests the core hypothesis that different subtypes have distinct genetic etiologies by comparing variant burden against controls and across subtypes.

Materials:

- Phenotypic subtypes from Protocol 1.

- Annotated variant calls from Protocol 2.

- Control datasets (e.g., gnomAD, unaffected siblings).

- Statistical software (R, Python).

Procedure:

- Variant Categorization: For each proband, categorize variants as:

- De novo LoF/Damaging: Protein-truncating or predicted damaging missense variants not present in parents.

- Rare Inherited LoF: Ultra-rare (allele frequency < 1x10⁻⁵) high-confidence LoF variants transmitted from an unaffected parent.

- Inherited Damaging Missense: Rare, predicted damaging missense variants.

- Case-Control Burden Analysis: For a given subtype, compare the burden of a specific variant category (e.g., de novo LoF in intolerant genes) to the burden in a control population (e.g., non-neuro gnomAD samples) using a Fisher's exact test or a regression model that controls for covariates [10].

- Gene-Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA): For each subtype, test if the genes carrying damaging variants are enriched for specific biological pathways (e.g., synaptic function, chromatin modification, ion transport) using tools like GSEA or Enrichr.

- Cross-Subtype Comparison: Statistically compare the variant burden and pathway enrichment results across the different ASD subtypes to confirm their distinct genetic profiles. For example, a chi-squared test can determine if the proportion of individuals with a damaging de novo mutation is significantly higher in the "Broadly Affected" subtype compared to the "Moderate Challenges" subtype.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integration of these three core protocols:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for ASD Subtyping and Genetic Analysis

| Item/Category | Function/Description | Example Tools & Databases |

|---|---|---|

| Large-Scale ASD Cohorts | Provide the necessary statistical power for subtype discovery and genetic association studies. | SPARK [10] [4], Autism Genetic Resource Exchange (AGRE) [11], Simons Simplex Collection (SSC) [11]. |

| Phenotypic Assessment Tools | Standardized instruments for measuring the core and associated features of ASD. | Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) [3], Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) [2]. |

| Sequencing & Analysis Platforms | Generate and process raw genomic data into analyzable variant calls. | Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) [13] [11], Whole-Exome Sequencing; BWA (alignment), GATK (variant calling) [10]. |

| Variant Annotation & Constraint Databases | Interpret the functional impact and population frequency of genetic variants. | gnomAD (frequency), LOFTEE (LoF annotation), REVEL (missense pathogenicity), pLI/LOEUF (gene constraint) [10]. |

| Machine Learning & Statistical Software | Identify data-driven subtypes and perform genetic burden tests. | R, Python (with scikit-learn, pandas), Growth Mixture Models [12], Community Detection Algorithms [4]. |

Data Presentation and Analysis

The application of the above protocols yields quantitative data that clearly differentiates ASD subtypes by their genetic architecture.

Table 3: Comparative Genetic Analysis Across ASD Subtypes and Studies

| Analysis Focus | Key Metric | Findings | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variant Burden by Subtype [4] | Proportion of individuals with damaging de novo variants. | Highest in the "Broadly Affected" subtype; uniquely enriched for rare inherited variants in the "Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay" subtype. | Confirms subtype-specific genetic etiologies; links variant origin to clinical severity. |

| Developmental Trajectories [12] | Variance in age of diagnosis explained by behavioral trajectories. | Socioemotional-behavioral trajectories explained 11.7% to 30.3% of variance in age of diagnosis. | Highlights the link between developmental course and diagnostic timing, informing early screening. |

| Gene Discovery (Large-Cohort) [10] | Number of new risk genes identified. | 5 new moderate-risk genes (e.g., NAV3, ITSN1) identified from 42,607 cases; NAV3 associated with inherited LoF. | Expands the known genetic landscape of ASD, revealing genes with moderate effect sizes. |

| Polygenic Architecture [12] | Genetic correlation (rg) between autism factors. | Two autism polygenic factors were modestly correlated (rg = 0.38); one linked to early diagnosis, the other to later diagnosis and co-occurring conditions. | Suggests partially independent genetic pathways within ASD, relevant for psychiatric comorbidity. |

| Inherited Variants (Multiplex Families) [11] | Number of genes implicated by high-risk inherited variants. | 69 genes implicated, including 16 new ASD-risk genes, many from rare inherited variants. | Underscores the value of studying multiplex families to uncover inherited risk. |

The following diagram synthesizes the key logical relationships and pathways that emerge from the integrated analysis of subtypes and genetics, illustrating the model of ASD heterogeneity.

Application Note: Uncovering Subtype-Specific Developmental Timelines in Autism

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) represents a highly heterogeneous neurodevelopmental condition characterized by diverse clinical presentations and developmental trajectories. Recent advances in computational analytics and large-scale multimodal data integration have enabled the identification of biologically distinct ASD subtypes, revealing divergent patterns of brain development across clinically defined subgroups. This application note synthesizes cutting-edge research on subtype-specific developmental timelines, providing researchers and drug development professionals with structured data, experimental protocols, and analytical frameworks for investigating the temporal dynamics of brain development across autism subtypes. The findings detailed herein stem from integrative analyses combining phenotypic clustering with genetic, neuroimaging, and behavioral data, offering unprecedented insights into the mechanistic underpinnings of ASD heterogeneity.

Key Subtype Characteristics and Developmental Profiles

Research analyzing data from over 5,000 children in the SPARK cohort has identified four clinically and biologically distinct subtypes of autism, each demonstrating unique developmental trajectories and genetic profiles [4]. The table below summarizes the core characteristics and developmental timelines associated with each subtype.

Table 1: Autism Subtypes and Their Developmental Characteristics

| Subtype Name | Prevalence | Developmental Milestones | Cognitive & Behavioral Profile | Co-occurring Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social and Behavioral Challenges | 37% | Typical timing for early developmental milestones [4] | Significant social challenges and repetitive behaviors; higher rates of disruptive behaviors and attention difficulties [4] | ADHD, anxiety, depression, OCD commonly co-occur [4] |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | 19% | Significant delays in reaching early developmental milestones (e.g., walking, talking) [4] | Variable social communication and repetitive behaviors; intellectual disability often present [4] | Language delay and motor disorders common; lower rates of anxiety/depression [4] |

| Moderate Challenges | 34% | Typical timing for developmental milestones [4] | Milder core autism symptoms across all domains [4] | Lower rates of co-occurring psychiatric conditions [4] |

| Broadly Affected | 10% | Significant developmental delays across multiple domains [4] | Severe impairments in social communication, repetitive behaviors, and adaptive functioning [4] | High rates of multiple co-occurring conditions including anxiety, depression, mood dysregulation [4] |

Neurobiological Underpinnings of Divergent Trajectories

The identified subtypes demonstrate distinct neurobiological signatures that align with their clinical profiles and developmental timelines. Neuroimaging studies have revealed subtype-specific functional connectivity patterns that persist despite similar clinical presentations at the behavioral level [14]. Research utilizing positron emission tomography (PET) with novel radiotracers has identified significantly lower synaptic density (17% reduction) in autistic brains compared to neurotypical individuals, with the degree of reduction correlating with the severity of social-communication differences [15]. Furthermore, gene expression analyses indicate that each subtype is characterized by unique molecular signatures involving dysregulation of distinct biological pathways, including those governing embryonic proliferation, differentiation, and neurogenesis [16].

Table 2: Neurobiological and Genetic Correlates of Autism Subtypes

| Subtype | Genetic Profile | Neural Connectivity Patterns | Key Dysregulated Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social and Behavioral Challenges | Highest proportion of mutations in genes active during later childhood development [4] | Atypical connectivity in frontoparietal network, default mode network, and cingulo-opercular network [14] | Postnatal synaptic development and refinement pathways [4] |

| Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay | Higher burden of rare inherited genetic variants [4] | Distinct functional connectivity patterns across cerebellar and occipital networks [14] | Early neurodevelopmental pathways with moderate dysregulation [16] |

| Moderate Challenges | Less genetic burden from damaging de novo mutations [4] | Milder deviations from typical connectivity profiles [14] | Minimal pathway dysregulation across developmental periods [16] |

| Broadly Affected | Highest proportion of damaging de novo mutations [4] | Widespread functional connectivity alterations across multiple networks [14] | Severe dysregulation of embryonic proliferation, differentiation, and neurogenesis pathways [16] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Phenotypic Subtyping Using Generative Finite Mixture Modeling

Purpose

To identify clinically relevant autism subtypes based on comprehensive phenotypic profiling for subsequent investigation of developmental trajectories and biological correlates.

Materials and Reagents

- SPARK Cohort Data: Genetic and phenotypic data from 5,392 autistic individuals [4] [6]

- Phenotypic Measures:

- Computational Resources: High-performance computing cluster with sufficient memory for large-scale mixture modeling

- Software: R or Python with appropriate statistical packages for finite mixture modeling

Procedure

- Feature Selection: Compile 239 item-level and composite phenotype features from standardized diagnostic questionnaires and developmental history forms [6].

- Data Preprocessing: Clean and normalize heterogeneous data types (continuous, binary, categorical) for mixture modeling.

- Model Training: Apply General Finite Mixture Model (GFMM) with 2-10 latent classes, using multiple initialization points to avoid local maxima.

- Model Selection: Evaluate model fit using Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), validation log likelihood, and clinical interpretability to determine optimal class number [6].

- Class Validation: Assess class stability through perturbation testing and replicate findings in independent cohort (Simons Simplex Collection) [6].

- Clinical Annotation: Characterize identified classes by enrichment patterns across seven phenotypic categories: limited social communication, restricted/repetitive behavior, attention deficit, disruptive behavior, anxiety/mood symptoms, developmental delay, and self-injury [6].

Timing

- Data preprocessing: 2-3 weeks

- Model training and selection: 3-4 weeks

- Validation and clinical annotation: 2-3 weeks

Protocol 2: Multilevel Functional Connectivity Analysis for Neural Subtyping

Purpose

To identify autism subtypes based on patterns of brain functional connectivity and link these neural subtypes to behavioral presentations and developmental trajectories.

Materials and Reagents

- Imaging Data: Resting-state fMRI data from ABIDE I/II datasets (1,046 participants: 479 ASD, 567 typical development) [14]

- Eye-Tracking System: Tobii TX300 system with 300Hz sampling rate and 0.4° gaze accuracy [14]

- Stimuli: Social cognition tasks (face emotion processing, joint attention videos) [14]

- Analysis Software:

- fMRIPrep (v20.2.1) for data preprocessing [14]

- Custom scripts for static and dynamic functional connectivity analysis

- Normative modeling framework for quantifying individual deviations

Procedure

- Data Acquisition: Collect resting-state fMRI data using standardized protocols across multiple sites [14].

- fMRI Preprocessing: Process data through fMRIPrep pipeline, including motion correction, normalization, and denoising [14].

- Functional Connectivity Calculation:

- Normative Modeling: Build models of typical functional connectivity development using TD participants, then quantify individual deviations in ASD participants [14].

- Clustering Analysis: Apply clustering algorithms to multilevel FC features to identify neural subtypes [14].

- Eye-Tracking Validation: Administer social attention tasks (face emotion, joint attention) and compare gaze patterns across neural subtypes [14].

Timing

- fMRI data collection: 6-12 months (multi-site)

- Data preprocessing: 2-3 weeks

- Connectivity analysis: 3-4 weeks

- Normative modeling and clustering: 4-5 weeks

- Eye-tracking validation: 2-3 months

Protocol 3: Genetic Timing Analysis Across Developmental Subtypes

Purpose

To determine the developmental timing of genetic influences across autism subtypes by analyzing when subtype-associated genes are maximally expressed during brain development.

Materials and Reagents

- Genetic Data: Whole exome or genome sequencing data from autistic individuals

- Gene Expression Data: Brain transcriptomic data across developmental periods (prenatal to adulthood) from BrainSpan Atlas

- Analysis Tools:

- Synaptic density measurement: PET with 11C-UCB-J radiotracer [15]

- Gene set enrichment analysis software

- Statistical packages for temporal expression analysis

Procedure

- Genetic Variant Identification: Identify de novo and rare inherited variants in subtype-defined groups [4].

- Gene Set Compilation: Compile subtype-specific gene sets from genetic association results [4].

- Developmental Expression Analysis: Analyze temporal expression patterns of subtype-specific gene sets using BrainSpan transcriptomic data [4].

- Synaptic Density Measurement: Conduct PET scans with 11C-UCB-J radiotracer to quantify synaptic density in living individuals [15].

- Pathway Enrichment Analysis: Identify biological pathways enriched in each subtype's genetic profile [16].

- Timing-Gradient Mapping: Correlate peak expression periods of subtype-associated genes with clinical developmental milestones [4].

Timing

- Genetic data processing: 4-6 weeks

- Expression analysis: 3-4 weeks

- PET data collection: 6-8 months

- Integrative analysis: 2-3 months

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Investigating ASD Developmental Trajectories

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Analysis Platforms | SPARK cohort database, Simons Simplex Collection | Large-scale genetic and phenotypic data for subtype discovery and validation | [4] [6] |

| Neuroimaging Tools | Resting-state fMRI, PET with 11C-UCB-J radiotracer | Measure functional connectivity and synaptic density in living brains | [14] [15] |

| Eye-Tracking Technologies | Tobii TX300 system, EarliPoint Assessment | Quantify social attention patterns and identify biomarkers for early detection | [14] [17] |

| Computational Modeling Approaches | Generative Finite Mixture Models (GFMM), Normative Modeling | Identify latent subtypes and quantify individual deviations from typical development | [4] [14] |

| Transcriptomic Resources | BrainSpan Atlas, MSigDB Hallmark pathways | Analyze developmental gene expression patterns and pathway dysregulation | [4] [16] |

| Behavioral Assessment Tools | ADOS, SCQ, RBS-R, CBCL | Standardized phenotypic characterization across multiple domains | [4] [6] |

Implications for Machine Learning Classification Research

The delineation of subtype-specific developmental timelines provides critical constraints and features for advancing machine learning approaches to ASD classification. Temporal patterns of gene expression, distinct neurodevelopmental trajectories, and subtype-specific functional connectivity profiles offer biologically grounded feature sets that can enhance the predictive validity and clinical utility of classification models. Furthermore, the documented genetic and neurobiological differences between subtypes suggest that ensemble approaches or multi-task learning frameworks that account for subtype heterogeneity may outperform models treating autism as a unitary disorder. Future machine learning research should prioritize temporal modeling approaches that can capture developmental dynamics while incorporating multimodal data streams to reflect the biological complexity of autism subtypes.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) represents a highly heterogeneous neurodevelopmental condition, presenting a significant challenge for researchers and clinicians aiming to develop targeted diagnostics and therapies. The historical focus on behavioral criteria, while foundational, has often overlooked the complex biological underpinnings of the disorder. Recent advances in machine learning (ML) are now enabling a paradigm shift from behavior-based descriptions to biologically-defined subclassifications. By integrating large-scale phenotypic and genetic data, computational approaches can decompose this heterogeneity into distinct, biologically-meaningful subgroups [4] [6]. This Application Note details the experimental protocols and analytical frameworks for characterizing four recently identified ASD subtypes—Social/Behavioral, Mixed ASD with Developmental Delay, Moderate Challenges, and Broadly Affected—each with unique biological narratives and clinical trajectories [6] [18]. This structured approach provides a roadmap for applying ML classification to advance precision medicine in autism research and drug development.

Subtype-Specific Biological & Clinical Profiles

The four ASD subtypes, identified via generative mixture modeling of over 230 phenotypic features in 5,392 individuals from the SPARK cohort, demonstrate distinct clinical and genetic profiles [4] [6]. Table 1 summarizes the core defining characteristics of each subgroup.

Table 1: Clinical and Biological Profiles of ASD Subtypes

| Subtype Name | Approximate Prevalence | Core Clinical Presentation | Co-occurring Conditions & Developmental Trajectory | Distinct Genetic & Biological Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social/Behavioral | 37% | High scores on core social and repetitive behavior features [6]. | High rates of ADHD, anxiety, depression, OCD; minimal developmental delays; later age of diagnosis [4] [6]. | Strongest polygenic signals for ADHD and depression; mutations in genes active in later childhood brain development [4] [18]. |

| Mixed ASD with DD | 19% | Nuanced profile with developmental delays; mixed social communication and repetitive behaviors [6]. | Enriched language delay, intellectual disability, motor disorders; lower levels of ADHD/anxiety; earlier diagnosis [6]. | Highest burden of rare, inherited genetic variants [4] [18]. |

| Moderate Challenges | 34% | Lower scores across all core autism features compared to other subtypes [6]. | Fewer co-occurring psychiatric conditions; developmental milestones typically on track [4]. | Genetic profile is less severe, suggesting a different underlying biological mechanism [4]. |

| Broadly Affected | 10% | Severe impairments across all core and associated domains [6]. | Global developmental delays, intellectual disability, high rates of co-occurring anxiety/depression; earliest age of diagnosis [4] [6]. | Highest burden of damaging de novo mutations; enrichment in genes linked to Fragile X syndrome; dysregulation of embryonic neurogenesis pathways [4] [19] [18]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for deriving these subtypes from raw data through to biological interpretation, which is foundational for the protocols described in this document.

Experimental Protocols for Subtype Identification & Validation

Protocol: Phenotypic Data Collection and Processing

Objective: To systematically collect and preprocess the broad phenotypic data required for robust ML-based subtyping.

Materials and Reagents:

- Standardized behavioral questionnaires (e.g., SCQ, RBS-R, CBCL).

- Clinical background and medical history forms.

- Secure, HIPAA-compliant database for data storage (e.g., REDCap).

- Statistical computing software (e.g., R, Python).

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Collect item-level responses from a comprehensive battery of assessments. Core instruments should include:

- Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) - Lifetime: To assess core social and communication deficits [6].

- Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R): To quantify restricted and repetitive behaviors [6].

- Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL): To evaluate a wide range of emotional and behavioral problems [6].

- Developmental History Form: To capture milestones such as age of first walking and talking [4] [6].

- Data Curation and Feature Engineering:

- Cleaning: Handle missing data using appropriate imputation methods or exclusion criteria.

- Feature Assignment: Map each of the ~239 raw phenotypic items to one of seven pre-defined clinical categories to facilitate interpretation: Limited Social Communication, Restricted/Repetitive Behavior, Attention Deficit, Disruptive Behavior, Anxiety/Mood, Developmental Delay, and Self-Injury [6].

- Cohort Definition: Select a large, well-characterized cohort (e.g., n > 5,000 from the SPARK study) including individuals with ASD and, if available, neurotypical siblings as controls [6] [18].

Protocol: Machine Learning-Driven Subtyping

Objective: To identify latent subgroups of individuals based on their combined phenotypic profiles using a person-centered modeling approach.

Materials and Reagents:

- Processed phenotypic dataset from Protocol 3.1.

- High-performance computing cluster.

- Statistical software with ML libraries (e.g., R

mclustpackage, Pythonscikit-learn).

Methodology:

- Model Selection: Employ a Generative Finite Mixture Model (GFMM). This model is chosen for its ability to handle mixed data types (continuous, binary, categorical) without strong assumptions about underlying distributions and its person-centered nature, which clusters individuals rather than traits [6].

Model Training and Validation:

- Train multiple GFMM models, specifying between 2 and 10 latent classes.

- Use the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), validation log-likelihood, and clinical interpretability to select the optimal number of classes. A four-class solution has been shown to provide an optimal balance [6].

- Assess model stability by testing its robustness to data perturbations and bootstrapping [6].

Class Assignment and Profiling:

- Assign each individual to the class for which they have the highest posterior probability.

- Profile the classes by calculating the enrichment and depletion of every phenotypic feature within each class relative to others. Statistically validate these differences using appropriate tests (e.g., FDR-corrected p-values, Cohen's d) [6].

Protocol: Genetic Association and Biological Pathway Analysis

Objective: To link the phenotypically-defined subtypes to distinct genetic architectures and dysregulated biological pathways.

Materials and Reagents:

- Saliva or blood samples for DNA and RNA extraction.

- Genotyping arrays and/or Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) services.

- RNA sequencing services.

- Bioinformatics pipelines for genetic variant calling and gene expression analysis.

- Pathway analysis databases (e.g., MSigDB, GO, KEGG) [19].

Methodology:

- Genetic Data Generation:

Variant and Pathway Analysis:

- Variant Burden Testing: Compare the burden of de novo and rare inherited loss-of-function variants between subtypes. For example, the Broadly Affected subtype shows a significantly higher burden of damaging de novo mutations [4] [6].

- Polygenic Score Analysis: Calculate polygenic scores for ASD and related psychiatric conditions (e.g., ADHD, depression) and test for differences across subtypes [6].

- Pathway Enrichment: Identify sets of genes bearing significant mutations in each subtype and test them for enrichment in known biological pathways (e.g., MSigDB Hallmark pathways) [19]. The profound/Broadly Affected subtype, for instance, shows specific dysregulation in embryonic proliferation and neurogenesis pathways [19].

Developmental Timing Analysis:

- Analyze the spatiotemporal expression patterns of subtype-specific risk genes using brain transcriptomic atlases (e.g., BrainSpan).

- Correlate the peak activity periods of these gene sets (e.g., prenatal vs. childhood) with the clinical milestones of the subtypes (e.g., developmental delays vs. later-onset psychiatric challenges) [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for ML-Driven ASD Subtype Research

| Tool / Resource | Function in Research | Specific Application in Subtyping |

|---|---|---|

| SPARK Cohort Database | Large-scale repository of phenotypic and genetic data from over 50,000 ASD families [18]. | Primary data source for model training and validation; enables discovery at scale [6] [18]. |

| Simons Simplex Collection (SSC) | An independent, deeply phenotyped cohort of ASD families [6]. | Critical independent dataset for replicating and validating the identified subtypes [6]. |

| Generative Finite Mixture Model (GFMM) | A person-centered machine learning model for identifying latent classes in heterogeneous data [6]. | Core computational algorithm for decomposing phenotypic heterogeneity into subtypes without fragmenting individuals [6]. |

| MSigDB Hallmark Gene Sets | A curated collection of molecular signatures representing well-defined biological states and processes [19]. | Used to translate lists of subtype-associated genes into interpretable dysregulated biological pathways (e.g., embryonic neurogenesis) [19]. |

| BrainSpan Atlas | A transcriptomic atlas of the developing human brain across the lifespan. | Used to analyze the developmental timing of subtype-specific genetic disruptions, linking biology to clinical trajectory [4]. |

Visualization of Subtype-Specific Biological Pathways

The distinct genetic profiles of each subtype converge on different biological pathways. The following diagram summarizes key pathway dysregulations identified in the "Broadly Affected" and "Social/Behavioral" subtypes, highlighting potential targets for therapeutic development.

From Data to Diagnosis: ML Algorithms and Integrative Models for ASD Subtyping

Within the context of machine learning (ML) research for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) subtype classification, selecting an appropriate algorithm is a critical determinant of success. ASD is a highly heterogeneous neurodevelopmental disorder, and the identification of meaningful subgroups or endophenotypes is a central challenge. This Application Note provides a structured, comparative analysis of four prominent ML categories—Deep Learning (DL), Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Interpretable Models—for this specific research goal. We present quantitative performance benchmarks across diverse data modalities, detailed experimental protocols for implementation, and a curated toolkit to facilitate research efforts aimed at uncovering biologically distinct ASD subtypes.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

The performance of ML algorithms varies significantly depending on the data modality and the specific task (e.g., binary classification vs. subgroup discovery). The following tables summarize key findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Algorithm Performance on Clinical and Behavioral Data

| Algorithm | Data Modality | Sample Size | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning | ADI-R Scores (93 items) | 2,794 individuals | Accuracy | 95.23% | [20] |

| Random Forest (RF) | Eye-tracking (Social & Non-social) | 449 children | AUC | 0.849 | [21] |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Video-based Social Interaction Features | 88 adults | Balanced Accuracy | 79.5% | [22] |

| Interpretable (Rule-based) | Gene Expression | 431 samples | N/A (Identified ASD subtypes) | N/A | [23] |

Table 2: Relative Algorithm Characteristics for ASD Research

| Characteristic | Deep Learning | Random Forest | SVM | Interpretable Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Volume Needs | High (e.g., 1000s of samples) [24] [25] | Moderate [25] [26] | Low to Moderate [26] | Moderate |

| Interpretability | Low ("Black box") [24] [25] | Moderate (Feature Importance) [26] | Moderate (Support Vectors) | High (e.g., IF-THEN rules) [23] |

| Ideal Data Type | Raw, unstructured data (e.g., MRIs) [27] [25] | Structured/Tabular data (e.g., clinical scores) [26] | High-dimensional data (e.g., transcriptomics) [23] [26] | Tabular data for transparent reasoning [23] |

| Key Strength | State-of-the-art accuracy on large datasets; automated feature extraction [20] | Robust, high performance on tabular data; handles mixed data types [26] [21] | Effective in high-dimensional spaces with limited samples [26] | Subtype characterization; reveals biological mechanisms [23] |

Experimental Protocols for ASD Subtype Classification

Protocol: Deep Learning for Phenotype-Based Screening

- Objective: To achieve high-accuracy ASD vs. non-ASD classification and identify latent subgroups using deep learning on clinical phenotype data.

- Dataset: Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) scores from a large cohort (e.g., n > 2,500) [20].

- Preprocessing:

- Handle missing data through imputation or removal.

- Partition data into training, validation, and hold-out test sets.

- Standardize or normalize numerical item scores.

- Model Training & Screening:

- Train a Deep Neural Network (DNN) with multiple hidden layers using the training set.

- Use the validation set for hyperparameter tuning (e.g., layers, units, learning rate) to prevent overfitting.

- Attain screening accuracy on the hold-out test set [20].

- Subtype Identification:

- Use the embeddings or activations from a hidden layer of the trained DNN as a lower-dimensional representation of the clinical data.

- Apply clustering algorithms (e.g., community detection on a proximity matrix) to these representations to identify putative phenotypic subgroups [28].

- Validation: Correlate identified subgroups with external measures (e.g., transcriptomic profiles) to assess biological validity [20].

Protocol: Random Forest for Eye-Tracking Based Classification

- Objective: To build a robust classifier for early ASD identification using eye-tracking data.

- Dataset: Eye-movement data from children watching videos assessing both social and non-social cognition (n > 400) [21].

- Feature Set: Include features from both social (e.g., gaze to eyes) and non-social (e.g., visual search patterns) paradigms. Using both is critical for performance [21].

- Model Training & Evaluation:

- Train a Random Forest classifier, which is an ensemble of multiple decision trees.

- Use techniques like cross-validation and out-of-bag error to ensure generalizability.

- Evaluate the final model on a separate, temporal validation cohort to estimate real-world performance [21].

- Interpretation:

- Use the Gini importance or mean decrease in impurity provided by the RF model to rank feature importance.

- Apply SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to quantify the contribution of each feature to individual predictions, revealing which eye-tracking phenotypes are most discriminative [21].

Protocol: SVM for Social Interaction Dyad Analysis

- Objective: To classify ASD based on non-verbal reciprocity patterns in naturalistic social interactions.

- Dataset: Video recordings of dyadic conversations (ASD-TD and TD-TD dyads) [22].

- Feature Extraction:

- Use open-source computer vision algorithms (e.g., OpenFace) to extract time-series data on head pose, body movement, and facial action units for each individual.

- Compute interpersonal synchrony features by calculating the temporal coordination (e.g., using cross-correlation or wavelet coherence) of movements between dyad partners.

- Compute intrapersonal features, such as the total amount of movement or expressiveness [22].

- Model Training:

- Train a Support Vector Machine (SVM) using the extracted synchrony and individual movement features.

- The SVM finds the optimal hyperplane in the high-dimensional feature space to separate ASD-involved dyads from non-ASD dyads [22].

- Validation: Assess model performance using balanced accuracy and precision on a held-out test set.

Protocol: Interpretable ML for Subtype Dissimilarity Analysis

- Objective: To identify and characterize dissimilarities between pre-defined ASD subtypes (e.g., Autistic Disorder, Asperger's, PDD-NOS) using an interpretable model.

- Dataset: Integrated gene expression data from multiple independent case-control studies [23].

- Model Construction:

- Train a rule-based classifier (e.g., a decision tree or rule-learning algorithm) that uses gene expression levels to predict ASD subtypes.

- The model produces a set of human-readable IF-THEN rules (e.g.,

IF Gene_A > threshold_1 AND Gene_B < threshold_2 THEN Subtype_X) [23].

- Subtype Analysis:

- Visualize the rule-based model as a co-predictive network, where genes are nodes and connections represent their co-occurrence in predictive rules.

- Analyze the topological structure of this network. Estimate a centrality distance between subnetworks representing different clinical subtypes to quantify their dissimilarity. This can reveal, for instance, that autism is the most severe subtype, while Asperger's and PDD-NOS are more closely related [23].

Workflow Visualizations

ASD Subtyping Multi-Model Workflow

Interpretable ML Subtyping Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for ML-based ASD Subtype Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| ADI-R (Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised) | Gold-standard clinical assessment tool; provides structured phenotypic data for model training. | [20] |

| Open-Source Computer Vision Libraries (e.g., OpenFace) | Automated extraction of non-verbal social interaction features (facial action units, head pose) from video data. | [22] |

| Eye-Tracking Systems & Paradigms | Quantification of social and non-social visual attention patterns as objective behavioral biomarkers. | [21] |

| Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) | Public repository for transcriptomic data; enables integration of molecular data with clinical phenotypes. | [23] |

| Rule-Based Learning Algorithms | Generates interpretable IF-THEN models for subtype characterization and biomarker discovery. | [23] |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Post-hoc model interpretability tool; explains output of any ML model (e.g., RF, DL). | [21] |

| Clustering Algorithms (e.g., Community Detection) | Identifies putative subgroups within high-dimensional data or model-derived embeddings. | [28] [20] |

Recent breakthroughs in machine learning (ML) are revolutionizing the early detection of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). By leveraging recursive feature elimination and advanced algorithms, researchers can now identify compact, highly predictive subsets of behavioral items from standard screening tools. These streamlined sets achieve diagnostic accuracy exceeding 95%, demonstrating robust performance in cross-cultural validation. This protocol details the methodologies for replicating these high-accuracy ML models, which are critical for accelerating patient recruitment and refining subgroup stratification in large-scale neurobiological and drug development research.

The high heterogeneity of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) presents a significant challenge for traditional diagnostic methods, which often rely on time-consuming assessments prone to subjective interpretation [17] [29]. Within the broader scope of machine learning research for ASD subtype classification, a promising avenue has emerged: the development of high-accuracy screening tools using minimal, optimized item sets. This approach directly addresses critical bottlenecks in research and clinical practice, notably the lengthy administration time of tools like the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) and the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R), which can impede large-scale studies and delay early intervention [30].

Machine learning models have demonstrated a remarkable ability to identify the most predictive features from these extensive diagnostic instruments. By applying feature selection algorithms, researchers can distill dozens of questions into a core set of behavioral markers that retain—and in some cases enhance—diagnostic accuracy [2]. The convergence of these optimized feature sets across diverse populations and assessment tools suggests they may capture fundamental, cross-cultural aspects of the autism phenotype, providing a robust foundation for identifying biologically meaningful subgroups [30].

Quantitative Evidence for Streamlined Screening

Research across multiple diagnostic instruments and questionnaires consistently shows that reduced item sets can achieve high classification accuracy, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: High-Accuracy Machine Learning Models with Reduced Item Sets

| Original Instrument (Item Count) | Reduced Item Count | Key Predictive Items Identified | Algorithm(s) | Reported Performance | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q-CHAT-10 (10 items) | 3-4 items | Eye contact, Gaze following, Pretend play | XGBoost, Random Forest | AUROC: 85-91%; Sensitivity: 84-91% | [30] |

| ADOS (28-29 items) | 8-12 items | Not specified in results | ADTree, RFE | Accuracy: >97%; Sensitivity: 99.7% | [31] |

| ADI-R (93 items) | 7 items | Not specified in results | ADTree | Accuracy: 99.9% | [30] |

| AQ-10 (10 items) | 4 items | Not specified in results | ANN, SVM, Random Forest | Accuracy: >95% | [31] |

| Facial Image Analysis | N/A | Facial expression features | Xception, VGG16-MobileNet hybrid | Accuracy: 98-99% | [29] |

The evidence demonstrates that compact models achieve high performance while significantly reducing administrative burden. For instance, a 4-item model derived from the Q-CHAT-10 retained three core features—eye contact, gaze following, and pretend play—suggesting these social-communication behaviors represent robust autism risk markers across different populations [30]. These findings confirm that a small number of highly discriminative items can effectively predict clinical diagnoses when analyzed with sophisticated ML algorithms.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Feature Reduction and Model Training for Behavioral Questionnaires

This protocol outlines the process for deriving and validating a compact, high-accuracy screening model from a standard ASD questionnaire, such as the Q-CHAT-10 or AQ-10.

I. Materials and Data Preparation

- Dataset: Acquire de-identified response data for the target questionnaire from repositories, ensuring inclusion of confirmed clinical diagnoses as ground truth labels [30] [31].

- Preprocessing:

- Cleaning: Remove records with significant missing data or outliers.

- Encoding: Convert categorical responses (e.g., "Sometimes," "Never") to numerical values. Binarize responses where appropriate (e.g., 1 for presence of a trait, 0 for absence) [30].

- Feature Set: Include demographic variables (e.g., age, sex, familial history) alongside questionnaire items as potential model inputs [30].

II. Feature Selection and Model Training

- Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE):

- Apply RFE with cross-validation to identify the smallest set of items that maximizes predictive power for the clinical diagnosis [30] [31].

- Rank features by importance and iteratively remove the least important features.

- Continue until performance metrics (e.g., AUROC, sensitivity) begin to degrade significantly.

- Algorithm Selection and Training:

- Train multiple ML algorithms, including XGBoost, Random Forest, and Support Vector Machines (SVM), on the reduced feature set [30] [31].

- Use stratified k-fold cross-validation (e.g., k=10) during training to ensure robust performance estimation and avoid overfitting.

- Perform hyperparameter optimization for each algorithm using a randomized or grid search.

III. Model Validation and Threshold Optimization

- Performance Evaluation: Test the optimized model on a held-out validation set or an independent dataset from a different geographical or clinical context [30].

- Threshold Adjustment: Adjust the prediction probability threshold to maximize sensitivity (critical for screening) while maintaining acceptable specificity. For example, a threshold of 0.3 may achieve 91% sensitivity [30].

- Final Evaluation: Report key metrics including AUROC, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) on the test set.

Protocol 2: Validation Across Diverse Populations and Contexts

To ensure generalizability, a model trained to predict questionnaire scores must be validated against clinical diagnoses in independent populations.

I. Independent Validation Cohort

- Recruit or access a cohort with both questionnaire responses and clinician-established diagnoses based on comprehensive assessment (ADOS-2, ADI-R, DSM-5 criteria) [30].

- Ensure the cohort differs from the training data in relevant aspects (e.g., geography, healthcare system, ethnicity) to test model robustness.

II. Testing for Construct and Label-Source Shift

- Procedure: Apply the pre-trained model (e.g., trained on New Zealand Q-CHAT-10 data) directly to the new cohort's questionnaire data [30].

- Analysis:

- Calculate performance metrics (AUROC, sensitivity, specificity) against the clinical diagnosis ground truth.

- Compare these results to the model's performance on its original validation set.

- This process tests the model's ability to handle the "shift" from predicting a questionnaire score to predicting a complex clinical diagnosis in a new population.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Based ASD Screening

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Q-CHAT-10 / AQ-10 Dataset | Provides standardized behavioral item responses and demographic data for model training and validation. | Core dataset for feature reduction and model development [30] [31]. |

| Clinical Diagnosis Ground Truth | Gold-standard labels (e.g., from ADOS-2, ADI-R, DSM-5) essential for supervised learning and model validation. | Validating the accuracy of ML models against expert clinical judgment [30]. |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Algorithmic method for identifying the most predictive subset of items from a larger pool. | Reducing 10-item Q-CHAT-10 to a 3-4 item core model without significant loss of accuracy [30] [31]. |

| XGBoost / Random Forest Classifier | Advanced machine learning algorithms capable of modeling complex, non-linear relationships in data. | Training high-accuracy classification models on streamlined item sets [30]. |

| Eye-Tracking Technology (e.g., EarliPoint) | Hardware/software for quantifying gaze patterns, providing objective biomarkers for ASD. | FDA-approved tool for aiding in diagnosis; provides data for multimodal ML models [17]. |

Integration with ASD Subtype Classification Research

The development of streamlined, high-accuracy screens is not an endpoint but a critical enabler for larger classification research goals. Efficient screening allows for rapid identification and enrollment of individuals into deep phenotyping studies, which may include genomics, neuroimaging, and detailed behavioral analysis [17] [32].

I. From Screening to Stratification

- The core behavioral features identified by ML models (e.g., joint attention, pretend play) likely map to distinct neurobiological underpinnings [30].

- Individuals identified through these efficient screens can be stratified based on their profiles across these core features, creating more homogeneous subgroups for subsequent analysis.

II. Analytical Workflow for Subtype Discovery The logical flow from high-accuracy screening to refined subtype classification is a multi-stage process, integral to a comprehensive ML research thesis on ASD.

This workflow ensures that resources for intensive phenotyping are allocated efficiently, accelerating the discovery of subtypes with potential differences in etiology, prognosis, and treatment response [2] [32]. This is particularly relevant for drug development, where targeting specific biological subgroups may lead to more successful clinical trials.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by significant heterogeneity in its behavioral, genetic, and neurological manifestations [33]. This phenotypic and biological diversity presents substantial challenges for diagnosis, stratification, and treatment development. Conventional unimodal approaches often fail to capture the complex cross-modal dependencies underlying ASD pathophysiology [33]. The integration of genetic, transcriptomic, neuroimaging, and clinical data through advanced computational frameworks offers unprecedented opportunities to deconstruct this heterogeneity and identify meaningful biotypes. This protocol details comprehensive methodologies for multi-modal data fusion specifically tailored to machine learning-based ASD subtype classification, enabling researchers to leverage complementary biological information for precision psychiatry applications.

Performance Comparison of Modality-Specific Classification Approaches

Table 1: Performance metrics of single-modality machine learning models for ASD classification

| Modality | Feature Type | ML Architecture | Accuracy | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral | Clinical assessment scores [33] | Ensemble stacking with attention mechanism | 95.5% | High clinical translatability; Directly measures symptoms | Subjective assessment; Relies on observable behavior |

| Genetic | Gene-level constraint measures, spatiotemporal expression [33] | Gradient Boosting | 86.6% | Reveals biological underpinnings; High heritability correlation | Polygenic heterogeneity limits predictive power |

| sMRI | Cortical morphology, brain structure [33] | Hybrid CNN-GNN | 96.32% | Captures structural endophenotypes; High spatial resolution | Does not directly measure function |

| CBF | Cerebral blood flow values [34] | Transcriptome-neuroimaging spatial association | N/R | Links physiology with gene expression; Regional specificity | Emerging methodology; Limited validation |