Least Squares Estimation in Biology: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide to least squares estimation, tailored for biomedical researchers and drug development professionals.

Least Squares Estimation in Biology: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to least squares estimation, tailored for biomedical researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, practical applications in transcriptome and proteome-wide association studies, advanced troubleshooting for common pitfalls like weak instrumental variables, and comparative validation of modern methods. By integrating current methodologies like reverse two-stage least squares and regularized techniques, this resource bridges statistical theory with practical biological data analysis to enhance robustness and interpretability in translational research.

What is Least Squares? Core Principles for Biological Data Analysis

Defining Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) and the Best-Fit Line

This technical guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression, contextualized for biological data research. OLS is a fundamental statistical technique for estimating relationships between variables by minimizing the sum of squared differences between observed and predicted values [1] [2]. We detail the mathematical foundations, experimental protocols for implementation, and visualization techniques essential for applying OLS to biological datasets, including genomic, proteomic, and clinical data. The content emphasizes practical application within biological research frameworks, addressing both explanatory analysis and predictive modeling needs while highlighting critical assumptions and validation procedures.

Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) serves as a core computational technique in linear regression analysis, enabling researchers to quantify relationships between biological variables. In biological research, OLS provides a robust framework for modeling continuous outcomes—from gene expression levels and protein concentrations to physiological measurements and drug response data [3]. The method operates on a simple yet powerful principle: finding the linear model parameters that minimize the sum of squared residuals, where residuals represent the vertical distances between observed data points and the regression line [1].

The OLS approach offers distinct advantages for biological research, including computational efficiency, straightforward interpretability, and well-understood theoretical properties [4] [2]. Under the Gauss-Markov theorem, when key assumptions are met, OLS provides the Best Linear Unbiased Estimators (BLUE), ensuring reliable parameter estimates for making biological inferences [2]. Furthermore, the visual representation of OLS as a "best-fit line" through scatter plots of biological data offers an intuitive means for researchers to quickly assess relationships and identify patterns during exploratory data analysis [5].

Mathematical Foundations of OLS

Core Formulation

The OLS regression model expresses the relationship between a dependent variable (denoted as Y) and one or more independent variables (denoted as X) using the following equation for n observations [1] [6]:

Y = Xβ + ε

Where:

- Y is an n×1 vector of the observed dependent variable values

- X is an n×p matrix of the independent variable values (often including a column of 1s for the intercept)

- β is a p×1 vector of unknown parameters to be estimated

- ε is an n×1 vector of random error terms

The OLS method aims to find the parameter estimates β̂ that minimize the sum of squared residuals (SSR) [1]:

SSR(β) = Σ(yᵢ - ŷᵢ)² = Σ(yᵢ - xᵢβ)² = (Y - Xβ)ᵀ(Y - Xβ)

Parameter Estimation

The solution to this minimization problem yields the familiar OLS estimator [1] [6]:

β̂ = (XᵀX)⁻¹XᵀY

This closed-form solution provides the unique best-fit parameters when the matrix XᵀX is invertible, which requires that the explanatory variables are not perfectly multicollinear [1]. The resulting regression equation generates predicted values (ŷ) for the response variable, forming the line of best fit through the data cloud [5].

Goodness-of-Fit Metrics

To evaluate how well the OLS model explains variability in biological data, researchers rely on several key metrics:

Table: Goodness-of-Fit Metrics for OLS Regression

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Biological Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| R-squared (R²) | 1 - (SSR/SST) | Proportion of variance explained | Assesses how well predictors explain biological outcome variability |

| Adjusted R² | 1 - [(1-R²)(n-1)/(n-p-1)] | R² adjusted for number of predictors | Allows comparison of models with different numbers of biological predictors |

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | √(SSR/n) | Standard deviation of residuals | Measures typical prediction error for biological outcomes |

Experimental Protocol for OLS in Biological Research

Data Preparation and Assumption Checking

Before applying OLS to biological data, researchers must verify that fundamental assumptions are satisfied to ensure valid inferences:

Linearity Check: Visually inspect scatterplots of the response variable against each predictor to confirm linear relationships. For biological data that exhibits curvature, consider polynomial terms (e.g., X²) or transformations while maintaining model linearity in parameters [4].

Independence Verification: Ensure observations are independent, particularly critical in biological replicates, time-series measurements, or clustered data structures. Account for dependencies using specialized models if present [4] [6].

Homoscedasticity Assessment: Create residual-versus-fitted plots post-modeling to verify constant variance of errors across all predicted values. Non-constant variance may require weighted least squares or variance-stabilizing transformations of biological measurements [7] [4].

Normality Testing: Use normal probability plots (Q-Q plots) or formal tests (e.g., Shapiro-Wilk) on residuals to check the normality assumption, particularly important for p-value calculations and confidence intervals with smaller biological datasets [7] [4].

Multicollinearity Evaluation: Calculate Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) for each predictor when using multiple regression. High VIF values (>10) indicate collinearity issues that may destabilize parameter estimates in biological models [1] [4].

Model Fitting Procedure

The following workflow provides a systematic approach to implementing OLS analysis for biological data:

Define Biological Hypothesis: Clearly state the relationship to be investigated (e.g., "Gene expression level X predicts drug response Y").

Select Variables and Model Form: Identify dependent and independent variables based on biological relevance. For multiple predictors, specify the full model: Y = β₀ + β₁X₁ + β₂X₂ + ... + βₚXₚ + ε [6].

Compute Parameter Estimates: Use statistical software to calculate β̂ = (XᵀX)⁻¹XᵀY, obtaining the intercept and slope coefficients [1] [6].

Generate Predictions and Residuals: Calculate predicted values ŷ = Xβ̂ and residuals e = y - ŷ for further diagnostics [1].

Validation and Diagnostic Protocol

Post-estimation diagnostics are crucial for verifying OLS assumptions and model reliability with biological data:

Residual Analysis: Create and examine:

Influence Diagnostics: Identify influential observations using:

- Leverage values to detect extreme predictor combinations

- Cook's distance to flag cases affecting parameter estimates

- DFBETAS to measure each observation's impact on coefficients

Model Specification Testing: Use Ramsey's RESET test or similar approaches to detect omitted variables or incorrect functional forms.

OLS Application in Biological Research

Biological Case Studies

OLS regression has demonstrated particular utility across diverse biological domains:

Table: OLS Applications in Biological Research

| Biological Domain | Research Question | Variables | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Biology [6] | How does sun exposure affect plant growth? | Dependent: Plant heightIndependent: Days of sun exposure | Height = 30 + 0.1 × Days; Each day of sun increased height by 0.1 cm |

| Disease Modeling [7] | How does particle density affect material stiffness? | Dependent: StiffnessIndependent: Density, Density² | Stiffness = 12.70 - 1.517Density + 0.1622Density²; Quadratic relationship identified |

| Personalized Medicine [4] | Predicting disease progression | Dependent: Disease progression scoreIndependent: Age, cholesterol levels | Linear relationship established for risk stratification |

The Researcher's Toolkit for OLS Implementation

Successful application of OLS in biological research requires both computational tools and domain knowledge:

Table: Essential Research Tools for OLS Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Application in OLS Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R (stats package), Python (statsmodels), SPSS, SAS, GraphPad Prism | Parameter estimation, diagnostic testing, and visualization |

| Specialized Biological Platforms | XLSTAT [6], Minitab [7] | User-friendly OLS implementation with biological examples |

| Visualization Libraries | Seaborn [8], ggplot2, matplotlib | Regression plotting, residual diagnostics, and model validation |

| High-Throughput Data Tools | Flow cytometers [9], High-content screening systems [9] | Data generation for OLS modeling in drug discovery contexts |

Advanced Considerations for Biological Data

Addressing Common Challenges

Biological data frequently violates standard OLS assumptions, requiring specialized approaches:

Non-Normal Errors: For biological measurements with skewed distributions, apply transformations (log, square root) or use robust regression techniques that minimize the influence of outliers [8] [2].

Heteroscedasticity: When variability changes with measurement magnitude (common with concentration data), employ weighted least squares or heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors.

Multiple Testing: In genomic applications with numerous simultaneous hypotheses, adjust p-values using false discovery rate (FDR) methods rather than standard OLS inference.

High-Dimensional Data: For datasets with more predictors than observations (e.g., gene expression studies), use regularization methods (ridge regression, LASSO) rather than standard OLS.

Comparison with Alternative Methods

While OLS serves as a foundational approach, researchers should understand its position within the broader statistical toolkit:

Robust Regression: Addresses OLS sensitivity to outliers by using alternative loss functions (e.g., Huber loss), particularly valuable for biological data with measurement artifacts or extreme values [8] [2].

Logistic Regression: Essential for binary biological outcomes (e.g., disease present/absent) where OLS assumptions are violated and predictions must be constrained between 0 and 1 [8].

Nonparametric Regression: Lowess smoothing and related techniques help identify complex nonlinear relationships in biological systems without specifying a predetermined functional form [8].

Ordinary Least Squares regression remains an indispensable tool in biological research, providing a computationally efficient and interpretable framework for modeling relationships between continuous variables. When applied with appropriate attention to its underlying assumptions and limitations, OLS enables researchers to extract meaningful insights from diverse biological data—from molecular measurements to organism-level phenotypes. The method's dual strengths in both explanatory analysis and prediction make it particularly valuable for hypothesis testing and model building across biological domains. As biological datasets grow in complexity and scale, proper implementation of OLS principles, coupled with robust validation techniques, will continue to facilitate advances in understanding biological systems and accelerating drug discovery processes.

This technical guide provides researchers in biology and drug development with a comprehensive framework for applying and interpreting the least squares method. The ordinary least squares (OLS) technique is a fundamental statistical tool for modeling relationships between variables, crucial for analyzing experimental data from genomic studies to clinical trials. This whitepaper details the mathematical foundation of least squares regression, explains the interpretation of coefficients and error terms within biological contexts, and presents advanced methodologies that address common challenges in biomedical research. Through practical examples, structured tables, and visual workflows, we demonstrate how proper implementation of these techniques leads to more accurate and reliable conclusions in biological data analysis.

The method of least squares is a foundational statistical technique used throughout biological research for modeling relationships between variables. First published by Legendre in 1805 and independently developed by Gauss, this approach finds the best-fitting line to experimental data by minimizing the sum of squared differences between observed and predicted values [10]. In biological contexts, this enables researchers to quantify relationships between variables such as gene expression levels, protein concentrations, drug doses, and physiological responses.

The core principle of least squares involves adjusting model parameters to minimize the sum of squared residuals, where residuals represent the vertical distances between data points and the regression line [10]. This method remains particularly valuable in biological research because it provides unbiased, minimum-variance estimators when key assumptions are met, allowing researchers to draw reliable inferences from experimental data.

In contemporary biomedical research, ordinary least squares serves as the foundation for more sophisticated techniques. As we demonstrate in subsequent sections, understanding its core mechanics is essential for proper application to complex biological datasets, including those with high dimensionality, multicollinearity, and measurement noise—common challenges in genomics, proteomics, and pharmaceutical development.

The Least Squares Formula and Components

Mathematical Foundation

The linear regression model relating a dependent variable (Y) to one or more independent variables (X) is expressed as:

[Yi = \beta0 + \beta1Xi + \varepsilon_i,\quad i=1,2,\dots,n]

Where:

- (Y_i) represents the dependent variable (outcome measure)

- (X_i) represents the independent variable (predictor)

- (\beta_0) is the intercept term

- (\beta_1) is the slope coefficient

- (\varepsilon_i) is the error term [11]

The least squares method determines the optimal values of (\beta0) and (\beta1) that minimize the Sum of Squared Errors (SSE):

[SSE = \sum{i=1}^{n} (Yi - \hat{Y}i)^2 = \sum{i=1}^{n} \left(Yi - \hat{\beta}0 - \hat{\beta}1 Xi\right)^2 = \sum{i=1}^{n} ei^2]

Where (\hat{Y}i) represents the predicted value of (Yi), and (e_i) is the residual for the (i)th observation [11].

Parameter Estimation

The formulas for calculating the regression coefficients are derived by taking partial derivatives of the SSE with respect to (\beta0) and (\beta1) and setting them to zero. The slope coefficient (\hat{\beta}_1) is calculated as:

[\hat{\beta}{1} = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n} (Yi - \bar{Y})(Xi - \bar{X})}{\sum{i=1}^{n} (Xi - \bar{X})^2} = \frac{\text{Cov}(X, Y)}{\text{Var}(X)}]

The intercept (\hat{\beta}_0) is then determined as:

[\hat{\beta}0 = \bar{Y} - \hat{\beta}1\bar{X}]

Where (\bar{Y}) and (\bar{X}) represent the means of the dependent and independent variables, respectively [11].

Table 1: Components of the Least Squares Formula

| Component | Symbol | Description | Biological Research Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | (Y_i) | Outcome being measured or predicted | Gene expression level, drug response, protein concentration |

| Independent Variable | (X_i) | Predictor or explanatory variable | Drug dose, time point, age of subject |

| Intercept | (\beta_0) | Expected value of Y when X=0 | Baseline measurement, control group value |

| Slope Coefficient | (\beta_1) | Change in Y per unit change in X | Drug efficacy, rate of enzymatic reaction |

| Error Term | (\varepsilon_i) | Difference between observed and predicted values | Measurement error, biological variability |

Interpreting Regression Coefficients in Biological Contexts

Slope Coefficient Interpretation

The slope coefficient (\hat{\beta}_1) represents the expected change in the dependent variable for a one-unit change in the independent variable, holding all other factors constant [11]. In biological research, this interpretation must be contextualized within the specific experimental framework.

Consider a study examining the relationship between drug dose (X) and reduction in tumor size (Y). A slope coefficient of -0.85 would indicate that for each 1 mg increase in drug dose, tumor size decreases by 0.85 mm, assuming a linear relationship holds throughout the dose range.

The calculation of the slope coefficient can be illustrated with a concrete example from inflation and unemployment research, which follows the same mathematical principles as biological dose-response studies:

Table 2: Example Coefficient Calculation from Economic Research (Illustrative)

| Parameter | Value | Calculation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cov(X,Y) | -0.000130734 | - | Covariance between variables |

| Var(X) | 0.000144608 | - | Variance of independent variable |

| (\bar{X}) | 0.0526 | - | Mean of independent variable |

| (\bar{Y}) | 0.0234 | - | Mean of dependent variable |

| (\hat{\beta}_1) | -0.904 | (\frac{-0.000130734}{0.000144608} = -0.904) | Slope coefficient |

| (\hat{\beta}_0) | 0.071 | (0.0234 - (-0.904) \times 0.0526 = 0.071) | Intercept term |

In this example, the slope coefficient of -0.904 indicates that inflation decreases by approximately 0.90 units for each one-unit increase in unemployment [11]. Similarly, in a biological context, a negative slope would represent a decreasing trend in the dependent variable as the independent variable increases.

Intercept Term Interpretation

The intercept (\hat{\beta}_0) represents the expected value of the dependent variable when all independent variables equal zero [11]. In biological research, the interpretability of the intercept depends on the context:

- Meaningful intercept: When X=0 is within the experimental domain (e.g., control group in a dose-response study)

- Extrapolated intercept: When X=0 is outside the data range (e.g., birth weight in a study of adults)

For example, in a study of enzyme activity versus substrate concentration, the intercept might represent basal enzyme activity in the absence of substrate, which could have biochemical significance.

The Error Term in Biological Data Analysis

Composition and Significance

The error term (\varepsilon_i) in a regression model captures the discrepancy between observed data and model predictions. In biological research, this error arises from multiple sources:

- Measurement error: Limitations in analytical instruments or techniques

- Biological variability: Natural variation between organisms, cells, or samples

- Model misspecification: Omission of relevant variables or incorrect functional form

- Environmental fluctuations: Uncontrolled experimental conditions [12]

The standard error of the regression quantifies the average magnitude of these errors:

[\hat{\sigma}e = \sqrt{\frac{1}{T-k-1}\sum{t=1}^{T}e_t^2}]

Where (T) is the sample size and (k) is the number of predictors [13].

Assumptions About the Error Term

Valid interpretation of least squares regression requires several key assumptions about the error term:

- Conditional mean zero: The errors have an expected value of zero given any value of the independent variable: (E(ui|Xi) = 0) [14]

- Independence: Observations ((Xi, Yi)) are independent and identically distributed

- Finite outliers: Large outliers are unlikely ((Xi) and (Yi) have finite fourth moments) [14]

- Normal distribution: For hypothesis testing, errors should be normally distributed [11]

Violations of these assumptions are common in biological research and require specialized approaches, which we address in Section 6.

Experimental Protocols for Least Squares Analysis

Standard Workflow for Regression Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for performing least squares analysis in biological research:

Protocol 1: Basic Linear Regression Analysis

Purpose: To establish and validate a linear relationship between two variables in biological data.

Materials and Reagents:

- Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Biological Data Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software Platform (R, Python) | Data analysis and model fitting | R with lm() function or Python with scikit-learn |

| Data Collection Instrument | Generate predictor and response variables | Microarray, spectrophotometer, flow cytometer |

| Data Visualization Tool | Exploratory analysis and assumption checking | ggplot2 (R), matplotlib (Python) |

| Normalization Controls | Account for technical variability | Housekeeping genes, internal standards |

| Replication Samples | Estimate biological and technical variance | n ≥ 3 biological replicates |

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Collect raw data and screen for outliers using methods like Isolation Forest algorithm [15]

- Assumption Checking: Verify linearity, independence, and normality through residual plots

- Model Fitting: Compute regression coefficients using least squares estimation

- Diagnostic Checking: Examine residuals for patterns indicating assumption violations

- Validation: Assess model performance using R² and residual standard error

- Interpretation: Relate statistical findings to biological context

Troubleshooting:

- For nonlinear patterns, consider polynomial terms or transformations

- For correlated errors, use generalized least squares

- For heterogeneous variance, apply weighted least squares

Protocol 2: Advanced Applications in Biochemical Networks

Purpose: To infer dynamic interactions in biochemical networks from noisy experimental data.

Background: Reverse engineering biochemical networks requires specialized approaches due to substantial measurement noise from technical errors, timing inaccuracies, and biological variation [12].

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Obtain time-series measurements of network components (e.g., gene expression, protein concentrations)

- Network Linearization: Assume linear behavior around steady-state conditions

- Jacobian Estimation: Apply Constrained Total Least Squares (CTLS) to account for correlated noise in time-series data [12]

- Model Validation: Compare CTLS performance against ordinary least squares using error reduction metrics

Applications Demonstrated:

- Four-gene network identification

- p53 activity and mdm2 messenger RNA interactions

- IL-6 and IL-12b mRNA expression regulation by ATF3 and NF-κB [12]

Advanced Considerations for Biological Data

Addressing Measurement Error in Independent Variables

Standard ordinary least squares assumes independent variables are measured without error, which is frequently violated in biological research. When both dependent and independent variables contain noise, consider these alternative approaches:

- Deming Regression: Accounts for errors in both X and Y variables by minimizing perpendicular distances [16]

- Total Least Squares (TLS): Generalized approach for handling noisy coefficients [12]

- Constrained Total Least Squares (CTLS): Extends TLS to accommodate correlated errors in time-series data [12]

The following diagram illustrates the geometric differences between these approaches:

Directional Dependence in Biological Relationships

In many biological systems, causal relationships are complex and bidirectional, making the designation of "independent" and "dependent" variables arbitrary. For example, in studying the relationship between stress hormone levels and blood pressure, each may influence the other through feedback mechanisms [16].

When analyzing such symmetric relationships, researchers should consider presenting three regression lines:

- Regression of Y on X (minimizing vertical residuals)

- Regression of X on Y (minimizing horizontal residuals)

- Orthogonal (Deming) regression (minimizing perpendicular distances) [16]

This comprehensive approach provides a more balanced assessment of trends in data where causal directions are uncertain.

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Drug Development

Partial Least Squares in Pharmaceutical Formulation

Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression has become indispensable in pharmaceutical research for handling high-dimensional datasets with multicollinear variables, such as spectral data [17] [15]. Key applications include:

- Formulation development: Modeling relationships between composition parameters and drug properties

- Process optimization: Identifying critical process parameters affecting product quality

- Quality control: Predicting product characteristics based on spectral measurements

In one advanced implementation, T-shaped PLS (T-PLSR) combined with transfer learning addresses challenges in product development when comprehensive experimental data from large-scale manufacturing is limited [18]. This hybrid approach enhances prediction performance for new drug products by leveraging small-scale manufacturing data.

Drug Release Modeling

PLS regression enables accurate prediction of drug release from delivery systems based on formulation parameters and environmental conditions. A recent study achieved exceptional predictive performance (R² = 0.994) for polysaccharide-coated colonic drug delivery using:

- Data: 155 samples with 1500+ spectral variables

- Model: AdaBoost-MLP with PLS dimensionality reduction

- Optimization: Glowworm swarm optimization for hyperparameter tuning [15]

This approach demonstrates how least squares methodologies form the foundation for sophisticated machine learning applications in pharmaceutical development.

Proper interpretation of least squares coefficients and error terms is essential for extracting meaningful insights from biological data. The fundamental formula (Yi = \beta0 + \beta1Xi + \varepsilon_i) provides a powerful framework for quantifying relationships between biological variables, but researchers must carefully consider context, assumptions, and limitations.

Advanced implementations including Partial Least Squares, Total Least Squares, and Deming regression address specific challenges in biological data analysis, such as high dimensionality, measurement error, and uncertain causal direction. By selecting appropriate methodologies and validating assumptions, researchers can leverage the full potential of least squares estimation to advance biological knowledge and drug development.

As biological datasets grow in size and complexity, the principles of least squares remain fundamentally important, providing the foundation for increasingly sophisticated analytical approaches that drive innovation in biomedical research.

This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the four core assumptions of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression—linearity, independence, homoscedasticity, and normality—within the context of least squares estimation for biological data research. Violations of these assumptions can lead to biased estimates, inefficient parameters, and invalid statistical inferences, potentially compromising research conclusions and drug development outcomes. We present structured summaries of diagnostic methodologies, detailed experimental protocols for assumption testing, and visualization of analytical workflows to empower researchers in validating their statistical models. By integrating rigorous statistical assessment with biological research paradigms, this framework aims to enhance the reliability and reproducibility of data analysis in biomedical sciences.

Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression is the most common estimation method for linear models, used to draw a random sample from a population and estimate the properties of that population [19]. In regression analysis, the coefficients are estimates of the actual population parameters. For these estimates to be the best possible, they should be unbiased (correct on average) and have minimum variance (tend to be relatively close to the true population values) [19]. The Gauss-Markov theorem states that OLS produces the best linear unbiased estimates (BLUE) when its classical assumptions hold true [19] [20].

In biological research, where causal relationships between variables are often complex, deciding that one variable depends on another may be somewhat arbitrary [16]. Feedback regulation at molecular, cellular, or organ system levels can undermine simple models of dependence and independence. This paper focuses on the four critical assumptions—linearity, independence, homoscedasticity, and normality—that researchers must verify to ensure the validity of their regression models when analyzing biological data.

The Core Assumptions of OLS

Linearity

The assumption of linearity states that the regression model must be linear in the parameters (coefficients) and the error term [19] [21]. This does not necessarily mean the model must be linear in the variables, as linear models can model curvature by including nonlinear variables such as polynomials and transforming exponential functions [19].

Table 1: Linearity Assumption Overview

| Aspect | Description | Consequence of Violation |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Form | Model is linear in parameters (βs) | Fundamentally incorrect model specification |

| Parameter Relationship | Betas (βs) are multiplied by independent variables and summed | Inability to capture true relationship structure |

| Curvature Handling | Can include polynomials, transforms | Misleading conclusions about variable relationships |

| Biological Example | Dose-response relationships, enzyme kinetics | Inaccurate predictions across value range |

Diagnostic Methods: To verify linearity, researchers should plot independent variables against the dependent variable on a scatter plot [22]. The data points should form a pattern that resembles a straight line. If a curved pattern is evident, a linear regression model is inappropriate. Researchers can also plot observed values against predicted values; if linearity holds, points should be symmetrically distributed along the 45-degree line [21].

Remedial Measures: When the relationship is nonlinear, researchers can apply transformations to the variables using logarithmic, square root, or reciprocal functions [22]. Alternatively, they can incorporate non-linear terms into the model, such as polynomials (X²) or interaction terms [19].

Independence

The independence assumption states that observations of the error term should be uncorrelated with each other [19]. This means the error for one observation should not predict the error for another observation. In biological research, this assumption is most commonly violated in time-series data or when measurements are taken from related individuals (e.g., family studies, repeated measures) [23].

Table 2: Independence Assumption Overview

| Aspect | Description | Consequence of Violation |

|---|---|---|

| Error Relationship | Error terms are uncorrelated with each other | Standard errors of coefficients are biased |

| Data Collection Context | Common issue: time series data, related samples | Inflated Type I or Type II error rates |

| Biological Examples | Longitudinal studies, family pedigrees, repeated measures | Invalid significance tests and confidence intervals |

| Formal Name | Serial correlation or autocorrelation | Estimates are not efficient (not BLUE) |

Diagnostic Methods: For data collected sequentially, researchers should graph residuals in the order of collection and look for randomness [19]. Cyclical patterns or trends indicate autocorrelation. Statistical tests for autocorrelation include Durbin-Watson for time series data or assessing the autocorrelation function [19]. For family data, specialized methods like generalized least squares account for genetic and environmental correlations [23].

Remedial Approaches: For time-dependent data, researchers can add independent variables that capture the systematic pattern, such as lagged variables or time indicators [19]. Alternative estimation methods include generalized least squares (GLS) models [23] or using robust standard errors that account for correlated data [20].

Homoscedasticity

Homoscedasticity describes a situation where the error term has constant variance across all values of the independent variables [24] [20]. The opposite, heteroscedasticity, occurs when the size of the error term differs across values of an independent variable [24]. In biological research, this might occur when measuring outcomes across vastly different scales or subgroups.

Table 3: Homoscedasticity Assumption Overview

| Aspect | Description | Consequence of Violation |

|---|---|---|

| Variance Pattern | Constant variance of errors | Inefficient coefficient estimates (not BLUE) |

| Visual Pattern | Even spread of residuals in scatterplot | Biased standard errors and misleading inferences |

| Technical Term | Homoscedasticity (same scatter) | Invalid hypothesis tests and confidence intervals |

| Biological Example | Laboratory measurements with different precision | Incorrect conclusions about significance |

Diagnostic Methods: The simplest diagnostic tool is a residuals versus fitted values plot [19] [24]. For homoscedasticity, the spread of residuals should be approximately constant across all fitted values, while a cone-shaped pattern indicates heteroscedasticity [19] [24]. Statistical tests include the Breusch-Pagan test [20] [25], which performs an auxiliary regression of squared residuals on independent variables, and the White test [20].

Remedial Approaches: When heteroscedasticity is detected, researchers can transform the dependent variable using logarithmic, square root, or other variance-stabilizing transformations [24] [20]. Alternatively, they can employ weighted least squares regression [24] [20] or use heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors [20] which correct the bias in standard error estimates while maintaining the original coefficient values.

Normality

The normality assumption states that the error term should be normally distributed [19]. This assumption is not required for the OLS estimates to be unbiased with minimum variance, but it is necessary for conducting statistical hypothesis testing and generating reliable confidence intervals and prediction intervals [19] [21].

Table 4: Normality Assumption Overview

| Aspect | Description | Consequence of Violation |

|---|---|---|

| Distribution Shape | Error terms follow normal distribution | Unreliable p-values for hypothesis tests |

| Requirement Level | Optional for coefficient estimation | Inaccurate confidence and prediction intervals |

| Central Limit Theorem | Applies for large samples (>100 observations) | Compromised small-sample inferences |

| Biological Context | Common with skewed biological measurements | Invalid conclusions about statistical significance |

Diagnostic Methods: Researchers can assess normality using a normal probability plot (Q-Q plot), where normally distributed residuals will follow approximately a straight line [19]. Histograms of residuals should show the characteristic bell-shaped curve. Statistical tests for normality include the Shapiro-Wilk test, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and Jarque-Bera test [19].

Remedial Approaches: For non-normal errors, researchers can apply transformations to the dependent variable (log, square root, Box-Cox) [21]. For large samples, the central limit theorem may ensure that coefficient estimates are approximately normally distributed even when errors are not [22]. Alternatively, researchers can use bootstrapping methods to obtain robust estimates of standard errors [20].

Experimental Protocols for Assumption Testing

Comprehensive Diagnostic Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for testing the four core OLS assumptions:

Protocol 1: Testing for Linearity in Dose-Response Experiments

Purpose: To verify the linearity assumption in biological experiments measuring response to treatment dosage.

Materials and Reagents:

- Experimental compounds at varying concentrations

- Cell culture or biological assay system

- Appropriate measurement instrumentation (spectrophotometer, fluorometer, etc.)

- Statistical software (R, Python, SAS, or equivalent)

Procedure:

- Conduct experiments across a range of doses (typically 5-8 concentration points)

- Measure biological response for each dose level with appropriate replication

- Plot raw data with dose on x-axis and response on y-axis

- Fit preliminary OLS regression model

- Generate residual plot (residuals vs. fitted values)

- Examine for systematic patterns (U-shaped or curved patterns indicate nonlinearity)

- If nonlinearity detected, apply transformations (log, square root) or add polynomial terms

- Refit model and reassess linearity

Interpretation: A random scatter of points in the residual plot indicates the linearity assumption is satisfied. Systematic patterns suggest the need for model specification changes.

Protocol 2: Assessing Independence in Longitudinal Studies

Purpose: To test the independence assumption in repeated measures or time-course biological data.

Materials and Reagents:

- Longitudinal biological data (e.g., gene expression over time, clinical measurements)

- Statistical software with time series analysis capabilities

Procedure:

- Arrange data in chronological order

- Fit OLS regression model

- Calculate residuals in time order

- Plot residuals against time or observation order

- Examine for trends, cycles, or non-random patterns

- Perform Durbin-Watson test for autocorrelation

- If autocorrelation detected, consider adding time-related covariates

- Alternatively, use generalized least squares (GLS) or mixed models

Interpretation: Non-significant Durbin-Watson test (p > 0.05) and random scatter in time-ordered residual plot support the independence assumption.

Protocol 3: Evaluating Homoscedasticity in Biomarker Studies

Purpose: To assess constant variance assumption when measuring biomarkers across patient subgroups or experimental conditions.

Materials and Reagents:

- Biomarker measurement data across different subject groups

- Appropriate assay kits or measurement platforms

- Statistical software with diagnostic capabilities

Procedure:

- Fit initial regression model with biomarker as outcome

- Plot residuals against fitted values

- Examine for fanning, cone-shaped, or other systematic patterns

- Conduct Breusch-Pagan or White test for heteroscedasticity

- If heteroscedasticity detected, apply variance-stabilizing transformations

- Consider weighted least squares with appropriate weighting scheme

- Alternatively, use heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors

- Refit model and reassess homoscedasticity

Interpretation: Non-significant Breusch-Pagan test (p > 0.05) and constant spread in residual plot support homoscedasticity.

Protocol 4: Testing Normality in Experimental Data

Purpose: To evaluate normality of errors in biological experimental data.

Materials and Reagents:

- Experimental outcome data

- Statistical software with normality testing capabilities

Procedure:

- Fit regression model to experimental data

- Calculate and extract residuals

- Create histogram of residuals with normal curve overlay

- Generate normal Q-Q plot of residuals

- Perform Shapiro-Wilk or Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test

- If non-normal, apply appropriate transformation to outcome variable

- For large samples (>100), rely on central limit theorem

- Alternatively, use bootstrapping for inference

Interpretation: Non-significant normality test (p > 0.05), straight-line Q-Q plot, and bell-shaped histogram support normality assumption.

The Research Toolkit for Biological Data Analysis

Statistical Software and Packages

Table 5: Essential Analytical Tools for OLS Assumption Testing

| Tool Name | Application Context | Key Functions | Biological Research Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| R Statistical Software | Comprehensive assumption testing | lm(), plot(), ncvTest(), durbinWatsonTest() |

Genome-wide association studies [23] |

| Python (Statsmodels) | Regression diagnostics | ols(), diagnostic(), het_breuschpagan() |

Analysis of gene expression data |

| SAS | Clinical trial data analysis | PROC REG, MODEL statement with diagnostics | Pharmaceutical drug development studies |

| SPSS | General biomedical research | Regression menu with residual diagnostics | Psychological and behavioral biomarker studies |

| Stata | Epidemiological research | regress, hettest, estat dwatson |

Population health and disease risk studies |

Specialized Biological Data Solutions

Table 6: Domain-Specific Solutions for Biological Data Challenges

| Solution Type | Addresses | Implementation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Least Squares (GLS) | Correlated data in family studies | RFGLS-UN and RFGLS-VC models for pedigree data | [23] |

| Deming Regression | Method comparison studies | Perpendicular distance minimization | [16] |

| Weighted Least Squares | Heteroscedastic measurement data | Inverse variance weighting | [24] [20] |

| Robust Standard Errors | Heteroscedasticity without transforming data | White or Huber-White estimators | [20] |

| Bootstrap Methods | Non-normal error distributions | Resampling with replacement | [20] |

Advanced Considerations for Biological Data

Complex Relationships in Biological Systems

In biological systems, the assumption that one variable depends on another may be arbitrary due to complex causal relationships [16]. Feedback regulation at molecular, cellular, or organ system levels can undermine simple models of dependence and independence. For example, in analyzing the relationship between serum peptide levels and symptom severity, it may be unclear whether peptide levels influence symptoms or symptoms influence peptide levels [16].

When relationships between variables are complex, researchers should consider plotting multiple regression lines, including:

- Regression of y on x (vertical residuals)

- Regression of x on y (horizontal residuals)

- Orthogonal (Deming) regression (perpendicular residuals) [16]

This approach provides a more balanced assessment of trends in biological data where causal directions are uncertain.

Family and Genetic Data Structures

Family-based studies present special challenges for independence assumptions due to genetic and environmental correlations among relatives [23]. Recent methods for genome-wide association studies (GWAS) using family data include:

- Rapid Feasible Generalized Least Squares with unstructured family covariance matrices (RFGLS-UN)

- Rapid Feasible Generalized Least Squares with variance components (RFGLS-VC) modeling genetic, shared environmental, and non-shared environmental components [23]

These approaches accommodate both genetic and environmental contributions to familial resemblance while maintaining computational efficiency for large-scale genomic analyses.

Validating the core assumptions of linearity, independence, homoscedasticity, and normality is essential for producing reliable, reproducible research findings in biological and drug development contexts. The experimental protocols and diagnostic workflows presented in this whitepaper provide researchers with practical methodologies for assessing these assumptions and applying appropriate remedial measures when violations are detected. By integrating rigorous statistical assessment with biological research paradigms, scientists can enhance the validity of their conclusions and advance the discovery of robust biological insights. As statistical methods continue to evolve, particularly for complex biological data structures, maintaining focus on these fundamental assumptions remains critical for scientific progress.

In quantitative biological research, understanding the relationship between variables is fundamental. Correlation and linear regression are two cornerstone statistical methods used to quantify these associations, each with distinct purposes and interpretations. While both techniques analyze the relationship between two measurement variables, they answer different scientific questions. Correlation assesses the strength and direction of an association, whereas regression models the influence of one variable on another, enabling prediction. Within the framework of least squares estimation—a method that minimizes the sum of squared differences between observed and predicted values—both techniques provide a mathematical foundation for describing biological phenomena. However, confounding their applications can lead to misinterpretation, especially concerning the critical distinction between association and causation [26] [27].

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a technical overview of correlation and regression, focusing on their proper application, interpretation, and the inherent limitations regarding causal inference in biological models.

Conceptual Foundations: Correlation vs. Regression

Correlation Analysis

Correlation analysis quantifies the degree to which two continuous numerical variables change together. The most common measure, the Pearson correlation coefficient (denoted as r), ranges from -1 to +1 [26].

- Direction: A positive

rindicates that as one variable increases, the other tends to increase. A negativerindicates that as one variable increases, the other tends to decrease. - Strength: The closer the absolute value of

ris to 1, the stronger the linear relationship. The strength is often qualitatively interpreted as weak (|r| < 0.4), moderate (0.4 ≤ |r| ≤ 0.7), or strong (|r| > 0.7) [26]. - Symmetry: Correlation is symmetric; the correlation between A and B is the same as between B and A. It does not assume a designated outcome or predictor variable [26] [27].

A fundamental caveat is that correlation does not imply causation. A significant correlation might indicate a cause-and-effect relationship, or it might be driven by a third, unmeasured confounding variable [26] [27].

Linear Regression Analysis

Linear regression is used when one variable is an outcome and the other is a potential predictor. It models a cause-and-effect relationship, whether hypothesized or established through experimental design. The simple linear regression model is represented by the equation Y = β₀ + β₁X [26].

- Y is the dependent variable (outcome).

- X is the independent variable (predictor).

- β₀ is the intercept (the value of Y when X is zero).

- β₁ is the slope, which represents the magnitude and direction of the change in Y for a one-unit change in X [26].

In contrast to correlation, the variables in a regression model are not interchangeable. Correctly identifying the outcome (Y) and predictor (X) is critical. Furthermore, regression models can be extended to include multiple predictor variables, providing a more comprehensive modeling approach [26].

The following diagram illustrates the core logical relationship and primary output of each analytical approach.

Key Differences and When to Use Each

The choice between correlation and regression depends entirely on the research goal. The table below summarizes their core differences.

Table 1: A comparison of correlation and linear regression.

| Feature | Correlation | Linear Regression |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Measure strength & direction of a mutual relationship [26] | Model and predict the outcome based on a predictor; quantify cause-effect [26] |

| Variable Roles | Variables are symmetric and interchangeable [26] | Variables are asymmetric (X predicts Y) [26] |

| Output | Correlation coefficient (r) [26] | Regression equation (slope β₁ & intercept β₀) [26] |

| Key Question | Are two variables associated, and how strong is that association? | Can we predict the outcome from the predictor, and by how much does the outcome change? |

| Causation | Does not imply causation [26] | Implies a causal direction if derived from a controlled experiment [27] |

Quantitative Data and Experimental Protocols

Case Study: Amphipod Egg Count Analysis

To ground these concepts, consider a biological dataset measuring the weight and egg count of female amphipods (Platorchestia platensis) [27]. The research goal is to determine if larger mothers carry more eggs.

The raw data for a subset of specimens is shown in the table below.

Table 2: Raw data for amphipod weight and corresponding egg count [27].

| Weight (mg) | 5.38 | 7.36 | 6.13 | 4.75 | 8.10 | 8.62 | 6.30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Eggs | 29 | 23 | 22 | 20 | 25 | 25 | 17 |

| Weight (mg) | 7.44 | 7.17 | 7.78 | ... | ... | ... | ... |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Eggs | 24 | 27 | 24 | ... | ... | ... | ... |

Statistical Analysis Protocol

Objective: To analyze the relationship between amphipod weight (independent variable, X) and egg count (dependent variable, Y) using least squares estimation.

Step 1: Exploratory Data Analysis and Visualization

- Action: Create a scatter plot with amphipod weight on the x-axis and egg count on the y-axis.

- Rationale: Visual inspection reveals the form (linear or non-linear), direction, and strength of the potential relationship, and helps identify outliers [27] [28].

Step 2: Perform Correlation Analysis

- Action: Calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) and its corresponding P-value.

- Rationale: The P-value tests the null hypothesis that there is no linear association between weight and egg count (i.e., r = 0). A low P-value (e.g., < 0.05) provides evidence against the null hypothesis. The r value quantifies the strength of the association [27].

- Reported Result: For the full amphipod dataset, the analysis yields a significant but moderate positive correlation (r ≈ 0.46, P-value = 0.015). This indicates that heavier amphipods tend to have more eggs, but the relationship is not perfect [27].

Step 3: Perform Linear Regression Analysis

- Action: Fit a least squares regression line to the data, obtaining estimates for the intercept (β₀) and slope (β₁).

- Rationale: The regression model provides a predictive equation and quantifies the average change in egg count for each milligram increase in body weight.

- Reported Result: The fitted regression equation is Ŷ = 12.7 + 1.60X. The slope (β₁ = 1.60) suggests that for every 1 mg increase in body weight, the number of eggs increases by approximately 1.60 on average. The R² value (the square of the correlation coefficient) is 0.21, meaning that 21% of the variation in egg count can be explained by variation in mother's weight [27].

Step 4: Interpretation and Causation Consideration

- Interpretation: While a significant relationship exists, the low R² value indicates that factors other than weight strongly influence egg count.

- Causation: This was an observational study; the researchers measured both variables without manipulation. Therefore, we cannot conclude that increased weight causes higher fecundity. Alternative explanations include: heavier amphipods are older, or a third factor like nutrition influences both weight and egg production [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Success in biological data analysis relies on both statistical and wet-lab tools. The following table details key components for conducting experiments like the amphipod study and analyzing the resulting data.

Table 3: Key research reagents and essential materials for biological data analysis.

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| R or Python Programming Environment | Open-source ecosystems for creating automated, reproducible analysis pipelines. They offer robust data handling and visualization capabilities far beyond spreadsheet software [29]. |

| GraphPad Prism | A GUI-based software popular in biostatistics for straightforward statistical comparisons and generating publication-quality graphs without requiring extensive coding [28]. |

| Organism/Specimen Collection Kit | For field biology, this includes tools for the ethical and systematic collection of specimens (e.g., amphipods), ensuring sample integrity and minimizing bias. |

| Analytical Balance | Precisely measures the weight of biological specimens (e.g., to 0.01 mg precision), a critical continuous variable in many studies [27]. |

| Digital Laboratory Notebook | Platforms like Labguru help organize experimental metadata, track biological and technical replicates, and ensure data is FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable), which is crucial for AI-ready datasets [29] [30]. |

Visualizing Statistical Workflows in Biological Research

A structured approach to data analysis is vital for reliable conclusions in biological research. The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for data exploration and statistical modeling, from raw data to insight, highlighting the roles of correlation and regression.

Correlation and regression are powerful yet distinct tools in the biologist's statistical arsenal. Correlation measures association, while regression models prediction and influence. Both are built on the foundation of least squares estimation, providing a robust framework for quantifying relationships in biological data. A clear understanding of their assumptions, applications, and limitations—especially the critical principle that observational correlation cannot establish causation—is essential for drawing valid scientific inferences. As biological data grows in scale and complexity, adhering to rigorous data exploration workflows and employing the correct statistical test will remain paramount for generating reliable, reproducible insights in research and drug development.

Residual analysis serves as a critical diagnostic tool in statistical modeling, enabling researchers to quantify unexplained variance and validate model assumptions. Within biological data research, particularly in drug development, understanding residuals is fundamental for ensuring the reliability of inferences drawn from least squares estimation. This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for implementing residual analysis, with specialized methodologies for experimental biological data. We detail diagnostic protocols, visualization techniques, and interpretation guidelines specifically tailored to the quality standards required in pharmaceutical research and development.

In regression modeling, a residual is defined as the difference between an observed value and the value predicted by the model [31]. For each data point, the residual ( ei ) is calculated as ( ei = yi - \hat{y}i ), where ( yi ) represents the observed dependent variable value and ( \hat{y}i ) represents the corresponding predicted value from the estimated regression equation [31] [32]. These residuals provide the foundation for assessing model fit and verifying whether the error term in the regression model satisfies key assumptions necessary for valid statistical inference [31].

In the context of least squares estimation for biological data, residual analysis transforms abstract statistical assumptions into testable conditions. The core assumptions regarding the error term ε include: linearity, independence, homoscedasticity (constant variance), and normality [31]. When these assumptions are satisfied, the resulting model is considered valid, and conclusions from statistical significance tests can be trusted. Conversely, when residual analysis indicates violations of these assumptions, it often suggests specific modifications to improve model performance [31].

Core Concepts and Mathematical Framework

Types of Residuals and Their Applications

Different types of residuals serve distinct diagnostic purposes in model validation, particularly in linear mixed models common in biological research:

- Raw Residuals: The simplest form, calculated as ( ri = yi - \hat{y}_i ) [32]. These form the basis for more sophisticated residual measures but may mask underlying patterns due to unequal variances.

- Standardized/Studentized Residuals: Raw residuals scaled by their standard deviation, given by ( r_{student} = \frac{r}{\sqrt{\text{var}(r)}} ) [33]. This transformation enables comparison of residual magnitudes across different data points by putting them on a common scale.

- Pearson Residuals: Residuals scaled by the estimate of the standard deviation of the observed response, calculated as ( r_{pearson} = \frac{r}{\sqrt{\text{var}(y)}} ) [33]. These are particularly useful for diagnosing overall model fit.

- Scaled Residuals: Employ Cholesky decomposition to produce transformed residuals with constant variance and zero correlation, expressed as ( R = \hat{C}^{-1} r ) where ( \hat{C} ) is the Cholesky root of the variance-covariance matrix ( \hat{V} ) [33]. These are especially valuable for detecting remaining correlation structures in longitudinal biological data.

Residual Variance and Sum of Squares

The residual variance ( \sigma^2 ) quantifies the unexplained variability in the regression model after accounting for the independent variables. For an independent and identical error structure, it is estimated by the residual sum-of-squares divided by the appropriate degrees of freedom [33]: [ \hat{\sigma}^2 = \frac{e^Te}{n-p} ] where ( n ) represents the sample size and ( p ) denotes the number of estimated parameters (rank of the design matrix) [33]. The residual sum of squares (RSS), calculated as ( \sum{i=1}^n (yi - \hat{y}_i)^2 ), represents the total unexplained variation minimized in least squares estimation [33].

Diagnostic Methodologies for Residual Analysis

Graphical Analysis Techniques

Visual examination of residuals provides intuitive diagnostics for detecting violations of regression assumptions:

- Residual vs. Fitted Values Plot: The most common residual plot displays predicted values ( \hat{y} ) on the horizontal axis and residuals on the vertical axis [31]. If model assumptions are satisfied, the points should form a horizontal band around zero with no discernible patterns [31] [33].

- Residual vs. Independent Variable Plot: Plotting residuals against individual independent variables helps detect whether the relationship has been adequately captured or requires transformation [33].

- Quantile-Quantile (Q-Q) Plot: Assesses the normality assumption by plotting sample quantiles against theoretical quantiles from a normal distribution. Departures from a straight line indicate deviations from normality.

- Index Plot: Particularly useful for time-ordered or sequentially collected biological data, this plot displays residuals in their collection sequence to detect temporal correlations [33].

Quantitative Goodness-of-Fit Tests

Statistical measures complement graphical diagnostics by providing objective criteria for model assessment:

- Residual Bias: The arithmetic mean of residuals should approximate zero when the model is correctly specified [33].

- Residual Skewness and Kurtosis: For normally distributed errors, residual skewness should approximate zero and kurtosis should approach 3 [33].

- Coefficient of Determination (R²): Calculated as ( R^2 = 1 - \frac{SS{residual}}{SS{total}} ), where ( SS ) denotes sum of squares [33]. Measures the proportion of variance explained by the model.

- Hamilton R-factor: Particularly used in chemometrics, calculated as ( R = \sqrt{\frac{SS{residual}}{SS{total}}} ) [33].

Table 1: Goodness-of-Fit Statistics for Model Validation

| Statistic | Calculation Formula | Target Value | Interpretation in Biological Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residual Bias | ( \frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^n ei ) | 0 | Systematic over/under-prediction of biological measurements |

| Residual Standard Deviation | ( \sqrt{\frac{\sum{i=1}^n (ei - \bar{e})^2}{n-p}} ) | Comparable to instrumental error | Model precision relative to measurement technology |

| Residual Skewness | ( \frac{\frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^n (ei - \bar{e})^3}{\left(\frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^n (ei - \bar{e})^2\right)^{3/2}} ) | 0 | Asymmetry in error distribution across biological replicates |

| Residual Kurtosis | ( \frac{\frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^n (ei - \bar{e})^4}{\left(\frac{1}{n}\sum{i=1}^n (ei - \bar{e})^2\right)^2} ) | 3 | Extremeness of outliers in experimental data |

Experimental Protocols for Biological Data

Protocol 1: Residual Analysis for Dose-Response Studies

Purpose: To validate linearity assumptions in pharmacological dose-response relationships and identify appropriate transformations.

Materials and Equipment:

- Response measurement instrumentation (e.g., plate reader, PCR machine)

- Statistical software with regression capabilities (e.g., R, Python, Prism, MATLAB)

- Biological replicates (minimum n=6 per dose level)

Procedure:

- Fit initial linear model: ( Response = \beta0 + \beta1 \times Dose + \epsilon )

- Calculate residuals: ( ei = Responsei - (\hat{\beta}0 + \hat{\beta}1 \times Dose_i) )

- Generate residual vs. fitted values plot

- Test for systematic patterns using runs test or Durbin-Watson statistic

- If patterns detected, apply Box-Cox transformation to response variable

- Refit model with transformed response and reassess residuals

- Document residual standard deviation as measure of assay precision

Interpretation Guidelines:

- Fan-shaped pattern in residuals indicates variance proportional to dose, requiring variance-stabilizing transformation

- Curvilinear pattern suggests need for higher-order terms or nonlinear model

- Random scatter validates linear model assumption

Protocol 2: Longitudinal Residual Analysis in Preclinical Studies

Purpose: To verify independence assumption in repeated measures designs common in toxicology and efficacy studies.

Materials and Equipment:

- Longitudinal data collection system

- Software capable of mixed-effects modeling (e.g., R lme4, SAS PROC MIXED)

- Subject tracking database

Procedure:

- Fit linear mixed model: ( Y{ij} = X{ij}\beta + Z{ij}bi + \epsilon_{ij} )

- Extract conditional residuals: ( r{ci} = Yi - Xi\hat{\beta} - Zi\hat{b}_i ) [33]

- Calculate marginal residuals: ( r{mi} = Yi - X_i\hat{\beta} ) [33]

- Create scatterplot matrix of residuals across time points

- Calculate intra-class correlation coefficient from random effects

- Fit variogram to detect temporal correlation structure

- If substantial correlation remains, modify random effects structure or incorporate AR(1) correlation for within-subject errors

Interpretation Guidelines:

- Significant correlation at lag 1 suggests need for autoregressive covariance structure

- Subject-specific patterns in conditional residuals indicate adequate capture of between-subject variation by random effects

- Systematic trends in marginal residuals suggest missing fixed effects

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Residual DNA Testing in Biologics Development

| Research Reagent | Function | Application in Biologics Quality Control |

|---|---|---|

| qPCR Residual DNA Kits | Dual-labeled hydrolysis probes for sensitive quantification of host cell genomic DNA | Lot release testing for vaccines, monoclonal antibodies, and cell therapies [34] [35] |

| Digital Droplet PCR (ddPCR) Reagents | Absolute quantification without standard curves; high sensitivity and specificity | Process validation and detection of low-abundance contaminants [35] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Libraries | Comprehensive detection and characterization of residual DNA fragments | Advanced characterization of complex biologics and gene therapy products [34] [35] |

| DNA Probe Hybridization Assays | Threshold-based detection of residual DNA contaminants | Raw material testing and in-process monitoring during biomanufacturing [34] |

| Sample Preparation Consumables | Isolation and purification of residual DNA from complex biological matrices | Preparation of samples for all residual DNA testing methodologies [35] |

Advanced Applications in Biological Research

Residual Analysis in Biomarker Identification

In omics-based biomarker discovery, residual analysis provides a powerful approach to distinguish biological signals from technical artifacts. By fitting models that incorporate batch effects, experimental conditions, and technical covariates, researchers can examine residuals to identify features with genuinely biological variation. Features with systematically non-random residuals across sample groups represent candidate biomarkers requiring further validation.

Quality Control in High-Throughput Screening

Residual analysis techniques adapt to quality assurance in high-throughput biological screening. The following diagram illustrates a standardized approach:

Implications for Drug Development and Regulatory Compliance

In pharmaceutical development, residual analysis transcends statistical exercise to become a regulatory imperative. The U.S. FDA and EMA mandate rigorous quality control testing, including residual DNA measurement, for biologics licensing applications [34] [35]. The global residual DNA testing market is projected to grow from $310 million in 2024 to $553 million by 2034, reflecting its importance in biopharmaceutical quality assurance [35].

Proper residual analysis in preclinical studies identifies problematic assay systems early, potentially saving millions in development costs. Models with non-random residuals produce biased estimates of potency and efficacy, jeopardizing dose selection for clinical trials. Furthermore, assay validation requirements under Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) guidelines necessitate demonstration that residual patterns conform to methodological assumptions.

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning in residual DNA testing and model validation represents the next frontier, with algorithms streamlining genomic interpretation and classifying genetic variants rapidly to enhance diagnostic yield [35]. These advancements will further refine residual analysis methodologies in biological research.

Residual analysis provides an essential framework for quantifying and understanding unexplained variance in biological experiments. Through systematic application of graphical diagnostics, statistical tests, and specialized protocols, researchers can validate model assumptions, identify data transformations, and ensure the reliability of inferences drawn from least squares estimation. In the rigorously regulated field of drug development, mastery of these techniques contributes not only to scientific accuracy but also to regulatory compliance and patient safety. As biological datasets grow in complexity and dimension, residual analysis methodologies will continue to evolve, maintaining their critical role in extracting meaningful signals from noisy experimental data.

Applying Least Squares Regression in Modern Biological Research

Transcriptome-Wide Association Studies (TWAS) with Two-Stage Least Squares (2SLS)

Transcriptome-Wide Association Studies (TWAS) have emerged as a powerful statistical framework that integrates genetic and transcriptomic data to identify putative causal genes for complex traits and diseases. The methodology addresses a critical limitation of genome-wide association studies (GWAS), which have successfully identified thousands of trait-associated genetic variants but often lack mechanistic insights, particularly when these variants fall in non-coding regions [36] [37]. Statistically, TWAS operates within the instrumental variable (IV) analysis framework, specifically implementing a two-sample two-stage least squares (2SLS) approach to test causal relationships between gene expression and complex traits [36]. This enables researchers to investigate whether genetic variants influence traits through their regulatory effects on gene expression, thereby providing biological context to GWAS findings.

The fundamental premise of TWAS is that by using genetic variants as instrumental variables, researchers can infer causal relationships between gene expression levels and complex traits while accounting for unmeasured confounding factors that typically plague observational studies [36] [38]. This approach has proven particularly valuable in drug development contexts, where identifying causal genes enhances target validation and reduces late-stage attrition. TWAS offers several advantages over conventional GWAS, including higher gene-based interpretability, reduced multiple testing burden, tissue-specific insights, and increased statistical power by leveraging genetically regulated expression [37].

Statistical Foundations of 2SLS in TWAS

The Instrumental Variables Framework

The 2SLS method in TWAS operates under the instrumental variables framework, which requires that genetic variants used as instruments satisfy three core assumptions [36] [38]. First, the relevance condition stipulates that the instrumental variables (genetic variants) must be strongly associated with the exposure variable (gene expression). Second, the exclusion restriction requires that the instruments affect the outcome only through their effect on the exposure, not through alternative pathways. Third, the independence assumption mandates that the instruments are not associated with any confounders of the exposure-outcome relationship.

In TWAS, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) serve as natural instrumental variables due to their Mendelian randomization properties [38]. Since genetic variants are fixed at conception and randomly allocated during meiosis, they are generally not susceptible to reverse causation or confounding by environmental factors. The typical structural equation model for TWAS with a continuous outcome can be represented as [36]:

Stage 1 (Expression prediction): Y = β₀ + β₁·SNP₁ + ... + βₘ·SNPₘ + U + ε

Stage 2 (Trait association): Z = α₀ + α₁·Ŷ + ξ

Where Y represents gene expression, SNP₁...SNPₘ are genetic variants, U represents unmeasured confounders, Z is the complex trait, and Ŷ is the predicted gene expression from Stage 1.

One-Sample vs. Two-Sample 2SLS

TWAS can be implemented in either one-sample or two-sample settings [36]. In the one-sample approach, the same dataset provides both the expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) reference and the GWAS data, with the entire sample used for both stages. In contrast, the two-sample approach utilizes independent datasets for Stages 1 and 2, which has become the standard in TWAS due to the typical availability of separate eQTL and GWAS resources [36]. The two-sample design offers practical advantages but requires careful consideration of sample overlap and population stratification.

Table 1: Comparison of One-Sample and Two-Sample 2SLS Designs in TWAS

| Feature | One-Sample 2SLS | Two-Sample 2SLS |

|---|---|---|

| Data requirement | Single dataset with both expression and trait data | Independent eQTL and GWAS datasets |

| Efficiency | Potentially more efficient with complete data | Robust to sample-specific confounding |

| Practical implementation | Less common in practice | Standard approach for TWAS |

| Confounding control | Requires careful modeling of residuals | Leverages independence of samples |

Methodological Workflow of TWAS

Stage 1: Building Expression Prediction Models

The first stage of TWAS develops models to predict the genetic component of gene expression using reference eQTL datasets [37]. This stage typically focuses on cis-acting genetic variants located within 1 megabase of the gene's transcription start site. For a given gene g, the relationship between expression and genetic variants is modeled as:

E_g = μ + Xβ + ε

Where E_g is the normalized expression level, X is the genotype matrix, β represents the eQTL effect sizes, and ε is the error term [37]. Since the number of cis-SNPs often exceeds the sample size, regularization methods are essential to prevent overfitting.

Table 2: Comparison of Expression Prediction Methods in TWAS

| Method | Statistical Approach | Key Features | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| PrediXcan | Elastic net regression | Linear model with L1 + L2 regularization | [37] |

| FUSION | Bayesian sparse linear mixed model (BSLMM) | Adapts to sparse and polygenic architectures | [37] |

| TIGAR | Dirichlet process regression | Non-parametric, robust to effect size distribution | [37] |

| Random Forest | Ensemble tree-based method | Captures non-linear effects, feature selection | [37] |

The predictive performance of Stage 1 models is typically assessed using cross-validation, with the coefficient of determination (R²) indicating the proportion of expression variance explained by genetic variants. The F-statistic is commonly used to evaluate instrument strength, with values greater than 10 indicating adequate strength [39].

Stage 2: Testing Association with Complex Traits

In the second stage, the trained prediction models from Stage 1 are applied to GWAS genotype data to impute genetically regulated expression (GReX), which is then tested for association with the complex trait of interest [36]. For continuous traits, linear regression is typically used, while for binary outcomes, logistic regression or specialized methods like two-stage residual inclusion (2SRI) may be employed [36].

The standard approach in TWAS uses two-stage predictor substitution (2SPS), which directly substitutes the imputed expression into the outcome model. However, for non-linear models (e.g., logistic regression), 2SPS may yield inconsistent estimates, making 2SRI preferable in these scenarios [36]. The 2SRI approach includes the first-stage residuals as covariates in the second stage to adjust for measurement error in the imputed expression.

Workflow Visualization

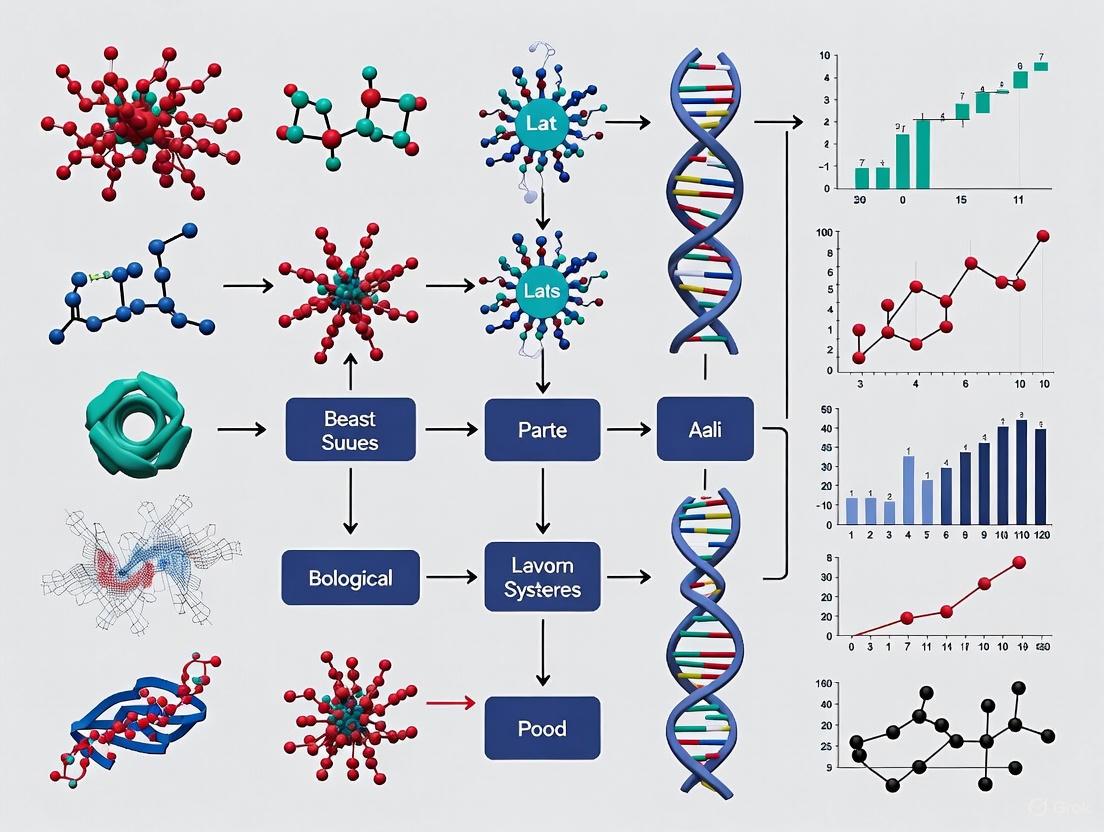

Figure 1: Core TWAS workflow illustrating the two-stage analytical process that integrates eQTL and GWAS data to identify putative causal genes.

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Addressing Instrument Validity Challenges

A significant challenge in TWAS is ensuring the validity of genetic instruments, particularly avoiding pleiotropy where genetic variants influence the outcome through pathways independent of the gene being tested [40]. Recent methodological advances have developed robust approaches to address invalid instruments:

- Two-stage constrained maximum likelihood (2ScML): Extends 2SLS to account for invalid instruments using sparse regression techniques [40]

- Probabilistic TWAS (PTWAS): Incorporates fine-mapped eQTL annotations and conducts heterogeneity tests to detect pleiotropy [41]

- Reverse 2SLS (r2SLS): Modifies the standard approach by predicting the outcome first, then testing association with observed expression, potentially reducing weak instrument bias [42]

Power and Sample Size Considerations

The statistical power of TWAS is influenced by multiple factors, including the sample sizes of both eQTL and GWAS datasets, the heritability of gene expression, and the strength of the causal relationship between expression and trait [43]. Empirical analyses suggest that Stage 1 sample sizes of approximately 8,000 may be sufficient for well-powered studies, with power being more determined by the cis-heritability of gene expression than by further increasing sample size [43].

Multivariate TWAS (MV-TWAS) methods that simultaneously test multiple genes have emerged as an extension to univariate approaches (UV-TWAS). The relative power of MV-TWAS versus UV-TWAS depends on the correlation structure among genes and their effects on the trait, with MV-TWAS showing particular promise when analyzing functionally related genes [43].

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Standard TWAS Implementation Protocol

For researchers implementing TWAS, the following protocol provides a detailed methodology:

Data Preparation and Quality Control

- Obtain genotype and expression data from reference eQTL datasets (e.g., GTEx, DGN)

- Perform standard QC on genetic data: MAF > 0.01, call rate > 0.95, HWE p-value > 1×10⁻⁶