Integrating Systems Biology and Copy Number Variant Analysis: From Gene Networks to Clinical Diagnostics

This article explores the powerful integration of copy number variant (CNV) analysis with systems biology approaches to unravel complex genetic architectures in human disease.

Integrating Systems Biology and Copy Number Variant Analysis: From Gene Networks to Clinical Diagnostics

Abstract

This article explores the powerful integration of copy number variant (CNV) analysis with systems biology approaches to unravel complex genetic architectures in human disease. We examine foundational concepts of CNVs as significant contributors to neurodevelopmental disorders, cancer, and pharmacogenetic traits. The scope encompasses methodological advances in CNV detection from sequencing data, troubleshooting strategies for optimizing analysis quality, and comparative validation of computational tools. By synthesizing these domains, we demonstrate how network-based prioritization and multi-modal data integration are transforming CNV interpretation, offering researchers and drug development professionals enhanced frameworks for identifying pathogenic variants, understanding disease mechanisms, and advancing personalized medicine.

Understanding CNVs in Complex Biological Systems: From Basic Genetics to Network Pathology

Copy Number Variation (CNV) is a fundamental type of structural variation (SV) in the genome, characterized by the repetition of DNA sequences where the number of repeats varies between individuals of the same species [1] [2]. These variants encompass a spectrum of unbalanced structural rearrangements, including duplications, deletions, and insertions, which lead to relative differences in the copy numbers of particular DNA sequences [1]. CNVs are a major contributor to genomic diversity, affecting an estimated 4.8–9.5% of the human genome [1] [2]. They range in size from as small as 50 base pairs to several megabases, with a median size around 18 kb [1] [2]. The functional consequences of CNVs are profound, primarily because they directly alter gene dosage and can disrupt genomic architecture and regulatory landscapes, influencing a wide array of phenotypes from normal population diversity to severe genetic disorders and complex diseases like cancer [1] [3] [4].

Classification and Molecular Mechanisms of Formation

CNVs are a subtype of structural variations. Their formation is driven by diverse genomic mechanisms, which can be broadly categorized into homology-dependent and homology-independent pathways [2].

Homology-Dependent Mechanisms:

- Non-Allelic Homologous Recombination (NAHR): This is a primary mechanism for recurrent CNVs. During meiosis, misalignment and crossover between highly homologous sequences (e.g., segmental duplications) on sister chromatids or homologous chromosomes lead to unequal exchange, resulting in a duplication on one chromosome and a deletion on the other [2].

- Break-Induced Replication (BIR): During repair of a double-stranded break, the broken end can invade a homologous template sequence (e.g., a sister chromatid) and initiate replication, potentially leading to the duplication of genetic material [2].

Homology-Independent (or Microhomology-Mediated) Mechanisms:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) / Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ): These pathways repair double-stranded breaks with little or no homology requirement. Error-prone repair can result in small insertions or deletions, and can facilitate the integration of retrotransposons, contributing to CNV formation [2].

- Fork Stalling and Template Switching (FoSTeS): Replication fork stalling and switching to a nearby template can cause complex rearrangements and copy number changes [1].

Table 1: Key Mechanisms of CNV Formation

| Mechanism | Primary Driver | Homology Requirement | Typical CNV Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Allelic Homologous Recombination (NAHR) | Meiotic recombination between misaligned repeats | High (>95% sequence identity) | Recurrent, large deletions/duplications |

| Break-Induced Replication (BIR) | DNA repair after double-stranded break | High | Non-recurrent duplications |

| Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ) | Error-prone repair of double-stranded breaks | Low (2-25 bp microhomology) | Small, non-recurrent indels/CNVs |

| Fork Stalling and Template Switching (FoSTeS) | Replication stress and fork collapse | Variable | Complex, non-recurrent rearrangements |

The genomic landscape influences CNV distribution. They are often enriched in regions with segmental duplications and are biased toward chromosome ends, areas of high genetic diversity and lower density of essential genes [3].

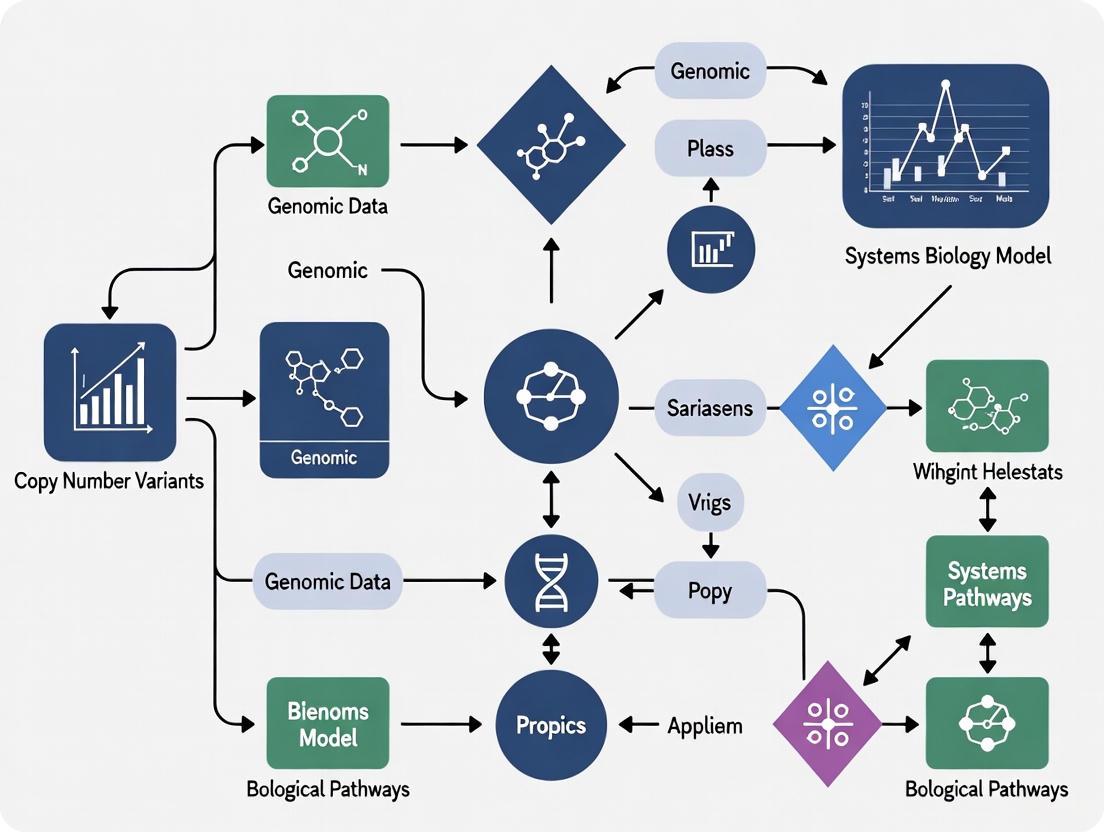

Diagram 1: Molecular pathways leading to CNV formation.

Detection and Analysis: Methods and Protocols

Accurate CNV detection is critical for research and clinical applications. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has become the cornerstone technology, with analysis relying on several computational strategies that interpret sequencing signals [5] [6].

Core Detection Strategies from NGS Data:

- Read Depth (RD): Analyzes the normalized count of sequencing reads aligned to a genomic region. A significant increase or decrease relative to the expected diploid coverage indicates a duplication or deletion, respectively [6].

- Split Read (SR): Identifies reads that are split and aligned to two non-contiguous regions of the reference genome, directly pinpointing the breakpoints of a structural variant [6].

- Read Pair (RP): Examines paired-end reads whose alignment distance or orientation is inconsistent with the reference genome, suggesting an intervening structural variant [6].

- De novo Assembly (AS): Reconstructs sequences without a reference, capable of discovering novel insertions and complex rearrangements [6].

Modern tools often integrate multiple signals to improve accuracy. For example, the MSCNV method uses a one-class support vector machine (OCSVM) to detect abnormal RD and mapping quality signals, then refines calls using RP signals, and finally determines precise breakpoints and variant type using SR signals [6].

Table 2: Comparison of CNV Detection Strategies & Tools

| Strategy | Principle | Strengths | Weaknesses | Example Tools/Cited Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Read Depth (RD) | Deviation from expected coverage depth | Genome-wide, sensitive to larger CNVs | Poor breakpoint resolution, confounded by coverage biases | CNVkit [5], FREEC [5] [6], GROM-RD [6] |

| Split Read (SR) | Identification of reads spanning breakpoints | Nucleotide-level breakpoint precision | Requires high coverage, challenging in repetitive regions | PINDEL [7], Delly [3] [6] |

| Read Pair (RP) | Inconsistent insert size or orientation of paired reads | Good for detecting medium-sized variants | Lower resolution than SR, sensitive to library prep | Manta [6], LUMPY [3] [6] |

| Hybrid/Integrated | Combines multiple signals (RD, SR, RP) | High accuracy, better breakpoint calling, fewer false positives | Computationally intensive | MSCNV [6], LUMPY [3], Haplotype-informed WES analysis [8] |

| Haplotype-Informed | Leverages shared SNP haplotypes across related individuals | High sensitivity for small, rare, inherited CNVs | Requires population/genotype data | UK Biobank WES Analysis [8] |

Protocol: Haplotype-Informed CNV Detection from Population-Scale Exome Sequencing (Adapted from [8])

- Objective: To sensitively detect rare, protein-altering CNVs, including sub-exonic variants, in large cohort data.

- Input: Whole-exome sequencing (WES) data (BAM files) and corresponding SNP genotype data for a large cohort (e.g., n > 50,000).

- Software: Custom pipeline employing negative binomial models for read counts and haplotype-sharing information.

- Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Align WES reads to a reference genome. Organize samples by genetic ancestry/population.

- Haplotype Phasing: Perform SNP phasing to determine haplotype blocks for each individual.

- Signal Extraction: Calculate normalized read depth (RD) for consecutive genomic bins (e.g., 100 bp) across target regions.

- Shared Haplotype Analysis: Cluster individuals sharing extended, identical-by-descent haplotypes in specific genomic regions.

- Statistical Modeling: For each region, model the RD signal using a negative binomial distribution. Parameters are estimated jointly across all individuals sharing a haplotype, increasing power to detect subtle, consistent RD shifts within the haplotype group.

- CNV Calling: Identify regions where the aggregated RD signal within a haplotype group significantly deviates from the population expectation (e.g., deletion for low RD, duplication for high RD). Call breakpoints at bin boundaries.

- Annotation & Filtering: Annotate CNVs with gene/exon overlap. Filter based on quality metrics (e.g., number of supporting reads, haplotype consistency).

Diagram 2: Multi-strategy workflow for CNV detection from NGS data.

Systems Biology Perspective: CNVs as Drivers of Phenotypic Diversity and Disease

Within a systems biology framework, CNVs are not isolated mutations but perturbations that ripple through molecular networks, affecting gene expression, protein interaction stoichiometry, and ultimately, cellular and organismal phenotypes [3] [4].

1. Direct Dosage Effects and Stoichiometric Imbalance: A CNV that encompasses a gene directly alters its copy number, typically leading to a proportional change in mRNA and protein levels [3]. In fission yeast, naturally occurring duplications were shown to significantly induce expression of genes within the duplicated region, with the degree of change correlating with copy number [3]. This can disrupt tightly balanced multiprotein complexes or signaling pathways.

2. Trans-Effects and Network Rewiring: CNVs can have effects beyond the duplicated/deleted genes. In yeast, duplications also caused moderate but widespread changes in the expression of genes outside the variant region, suggesting global transcriptional adjustments to dosage imbalance [3]. In cancer, CNV-driven long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) can act as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs), sponging miRNAs and thereby de-repressing entire networks of target mRNAs, promoting carcinogenesis [4].

3. Contribution to Complex Traits and Diseases: CNVs contribute substantially to the genetic architecture of quantitative traits. In fission yeast, CNVs were found to explain an average of 11% of the variance for traits like stress response and metabolism [3]. In humans, recent large-scale biobank studies demonstrate that protein-altering CNVs, previously missed, have significant effects on diverse phenotypes. For example: * A partial deletion of RGL3 exon 6 is associated with a protective effect against hypertension [8]. * Copy number changes in rapidly evolving gene families within segmental duplications contribute to type 2 diabetes risk and blood cell traits [8]. * In Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC), CNV-driven lncRNA MCCC1-AS1 is associated with shorter patient survival, acting as a hub in dysregulated ceRNA networks [4].

4. Evolutionary Dynamics: CNVs exhibit rapid turnover and transience, even within clonal populations, indicating they are dynamic features of the genome subject to strong selection pressures [3]. This rapid evolution allows for quick adaptation but also underlies their role in reproductive isolation (e.g., via inversions and translocations) and disease susceptibility [3].

Diagram 3: Systems biology view of CNV impact across biological scales.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents, Tools, and Platforms for CNV Research

| Item / Solution | Category | Primary Function in CNV Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Long-Read Sequencer | Sequencing Platform | Generates long (kb-scale), accurate reads to span repetitive regions and resolve complex SVs/breakpoints. | PacBio HiFi Sequencing [9] |

| Short-Read Sequencer | Sequencing Platform | Provides high-coverage data for RD-based and SR/RP-based CNV detection in large cohorts. | Illumina platforms (for DRAGEN, CNVfam [5]) |

| Reference Genome & Pangenome | Bioinformatic Resource | Baseline for read alignment. A pangenome incorporating diverse haplotypes improves mapping and variant calling accuracy. | Human Reference Genome (GRCh38), Human Pangenome [9] |

| SV/CNV Detection Software Suite | Bioinformatics Tool | Integrates NGS signals to call, genotype, and annotate CNVs with high sensitivity and specificity. | Manta [6], Delly [3] [6], CNVkit [5], MSCNV [6] |

| Haplotype Phasing Tool | Bioinformatics Tool | Infers haplotype blocks from SNP data, enabling sensitive detection of rare, inherited CNVs in population data. | Used in UK Biobank study [8] |

| Matched Normal DNA | Biological Sample | Critical for somatic CNV detection in cancer. Serves as a germline control to filter out inherited variants. | Required by tools like Control-FREEC [5] |

| Cell Line with Characterized SVs | Biological Control | Benchmarking standard for evaluating the performance and accuracy of CNV calling pipelines. | e.g., Cancer reference cell line sample [5] |

| Targeted Capture Probes (Exome/WGS) | Molecular Biology Reagent | Enriches genomic regions of interest (all exons for WES, entire genome for WGS) prior to sequencing. | Various commercial exome kits |

| Optimized Library Prep Kit | Molecular Biology Reagent | Prepares sequencing libraries from diverse sample types (e.g., FFPE, fresh frozen), impacting data quality. | Factor influencing caller accuracy [5] |

Copy Number Variations (CNVs), defined as deletions or duplications of DNA segments larger than 50 base pairs, represent a major class of genomic structural variation that covers approximately 4.8-9.5% of the human genome [10]. These genomic alterations are now recognized as crucial contributors to human disease and phenotypic diversity, functioning as fundamental components in the complex system of human genomics. From a systems biology perspective, CNVs do not operate in isolation but interact dynamically with transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolic networks to influence cellular phenotypes. This application note examines CNV analysis through an integrative systems biology framework, providing researchers with advanced methodologies to elucidate how structural genomic variations disrupt biological networks and contribute to disease pathogenesis across neurological, psychiatric, and oncological contexts.

Quantitative Landscape of CNV Pathogenicity

Recent large-scale studies across diverse patient populations have quantified the significant contribution of CNVs to human disease. The tables below summarize the detection rates and clinical impacts of pathogenic CNVs across different disorders.

Table 1: CNV Detection Rates in Clinical Studies

| Study Population | Sample Size | CNV Detection Rate | Pathogenic CNV Rate | Key Associations | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatric ABD Cohort [11] | 130 | 32.3% (42/130) | 17.7% (23/130) | Brain malformations, developmental delay | |

| Parkinson's Disease Cohort [12] | 2,364 patients, 2,909 controls | 2.4% in patients, 1.5% in controls | 0.9% in patients, 0.1% in controls | Early-onset Parkinson's, PRKN gene | |

| Pediatric Solid Tumors [13] | 198 patients | N/A | 20% of molecular alterations | Targetable oncogenic drivers |

Table 2: Characteristics of Pathogenic CNVs in Disease Cohorts

| CNV Characteristic | ABD Cohort [11] | Parkinson's Disease [12] | General Findings [10] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Most Affected Chromosomes | X, 15, 2, 17 | Chr 6 (PRKN locus) | All chromosomes, hotspots in SD regions |

| Common CNV Sizes | <5 Mb to >10 Mb | Exonic to whole-gene | 50 bp to several Mb |

| Key Genes/Loci | 7q11.23 (WBS), 15q11-q13 (AS/PWS), 22q11.2 (DGS) | PRKN, SNCA, PARK7 | 22q11.2, 16p11.2, 15q13.3 |

| Systems Impact | Neurodevelopment, synaptic function | Dopaminergic neuron survival, mitochondrial function | Brain structure, cognition, physical health |

Integrated Experimental Protocols for CNV Analysis

CNV Detection Using Next-Generation Sequencing (CNV-Seq)

Principle: Low-depth whole-genome sequencing detects chromosomal imbalances by quantifying sequence read density across the genome [11].

Workflow:

- DNA Extraction: Isolate genomic DNA from peripheral blood, amniotic fluid, or fresh-frozen tissue using the QIAamp DNA Micro Kit. Assess DNA concentration using a Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer [11].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries using the CN-500 NGS platform (Illumina). Perform low-depth whole-genome sequencing to achieve an average depth of 0.1x, generating 36-bp single-end reads [11].

- Bioinformatic Processing:

- Alignment: Map quality-filtered sequencing reads to the human reference genome (e.g., GRCh37/hg19) using BWA-MEM [13].

- CNV Calling: Identify regions with significant deviation in read depth using the CNV analysis system (version 2.0; Berry Genomics). Set a minimum size threshold of 100 kb for reliable detection [11].

- Annotation & Pathogenicity Assessment: Annotate called CNVs against databases (ClinVar, DECIPHER, gnomAD). Classify pathogenicity according to ACMG/ClinGen guidelines [11].

CNV Detection from Single-Cell RNA-Seq Data

Principle: Infer copy number alterations from gene expression patterns in single-cell data, leveraging the assumption that genes in gained regions show higher expression and genes in lost regions show lower expression compared to diploid regions [14].

Workflow:

- Data Preprocessing: Create a count matrix from scRNA-seq data (10X Genomics, Smart-seq2). Perform initial quality control to remove low-quality cells.

- Reference Selection: Identify a set of euploid reference cells for normalization. This can be user-provided (e.g., healthy cells from the same sample) or automatically detected [14].

- CNV Inference: Apply a specialized computational tool. The choice of tool depends on the dataset and available information:

- Expression-based methods (InferCNV, copyKat, SCEVAN): Use sophisticated normalization and segmentation or HMMs on smoothed expression data [14].

- Allele-frequency-enhanced methods (Numbat, CaSpER): Integrate expression data with allelic imbalance information from called SNPs within the scRNA-seq reads, using Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) for robust calling [14].

- Subclone Identification & Visualization: Cluster cells based on inferred CNV profiles to identify distinct subclones. Generate copy number heatmaps for visualization [14].

CNV Detection from SNP Microarray Data

Principle: Identify CNVs by analyzing hybridization intensity patterns (Log R Ratio) and allelic balance (B Allele Frequency) from SNP genotyping arrays [15].

Workflow:

- Data Generation: Hybridize purified DNA to a high-density SNP microarray (Illumina or Affymetrix). Process raw intensity files through platform-specific software (GenomeStudio for Illumina) to obtain LRR and BAF values for each SNP marker [15].

- CNV Calling with Multiple Algorithms:

- PennCNV: Apply a Hidden Markov Model that integrates LRR, BAF, SNP spacing, and population frequency to call CNVs. Effective for family-based data [15].

- QuantiSNP: Use an Objective Bayes approach with an HMM to calculate posterior probabilities for CNV states [15].

- cnvPartition (Illumina): Utilize the built-in GenomeStudio plugin that applies Gaussian models to LRR and BAF for copy number assignment [15].

- Data Integration & Validation: Merge calls from multiple algorithms to increase specificity. Perform experimental validation of putative CNVs using MLPA or qPCR [12].

Figure 1: Integrated CNV Analysis Workflow. This systems-level overview depicts the multi-platform methodology for CNV detection, from sample collection to final interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for CNV Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Example Products/Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | High-quality DNA isolation from diverse sample types | QIAamp DNA Micro Kit (Qiagen) [11] |

| NGS Platform | Low-depth whole-genome sequencing for CNV detection | CN-500 Platform (Illumina) [11] |

| SNP Microarray | Genome-wide genotyping and CNV detection | Illumina Infinium, Affymetrix Cytoscan [15] |

| CNV Calling Software | Bioinformatic detection of CNVs from sequencing or array data | PennCNV, QuantiSNP, cnvPartition (Arrays) [15]; InferCNV, Numbat (scRNA-seq) [14] |

| Validation Reagents | Orthogonal confirmation of putative CNVs | MLPA Kits, qPCR Assays [12] |

| Annotation Databases | Pathogenicity classification and phenotype association | ClinVar, DECIPHER, gnomAD, OMIM [11] |

CNV analysis has evolved from basic cytogenetics to a sophisticated systems biology discipline. The integrated application of the protocols and tools detailed herein enables researchers to dissect the complex interplay between genomic structure, molecular networks, and phenotypic outcomes. As the field progresses, the combination of emerging technologies—such as long-read sequencing for resolving complex variations and single-cell multi-omics—with systems biology models will be crucial for unraveling the full spectrum of CNV impacts on human health and disease, ultimately paving the way for precision medicine interventions.

Application Note

Copy number variations (CNVs)—structural genomic alterations involving deletions or duplications of DNA segments typically larger than 1 kilobase—are now recognized as critical contributors to a wide spectrum of human diseases [16]. This application note examines the roles of CNVs in three major disease areas—neurodevelopmental disorders, cancer, and Parkinson's disease—through the integrative lens of systems biology. By synthesizing recent large-scale genomic studies and advanced computational methodologies, we provide a framework for investigating CNV-mediated pathogenetic mechanisms and their implications for diagnostic and therapeutic development.

Recent technological advances have enabled comprehensive CNV detection across various genomic platforms, from genotyping arrays to single-cell sequencing. These developments are particularly valuable for dissecting disease heterogeneity and identifying critical cellular pathways disrupted by gene dosage alterations. The following sections detail specific applications in major disease categories, supported by quantitative findings and experimental approaches.

CNVs in Neurodevelopmental Disorders (NDDs)

Disease Association and Pathogenic Mechanisms

CNVs contribute significantly to neurodevelopmental disorders including intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, and schizophrenia [16]. Their effect sizes and penetrance are markedly larger than those of common risk variants, making them invaluable for investigating NDD etiology [17]. Systems biology approaches have revealed that different CNV groups affect distinct developmental trajectories and cellular pathways.

Table 1: Key CNV Associations in Neurodevelopmental Disorders

| Genomic Region | Associated Syndrome | Key Genes | Primary Neurodevelopmental Phenotypes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16p11.2 | 16p11.2 deletion syndrome | Multiple genes | Autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability [16] |

| 15q11.2 | Angelman/Prader-Willi syndromes | UBE3A, SNORD116 | Intellectual disability, developmental delay, seizures [16] [11] |

| 7q11.23 | Williams-Beuren syndrome | ELN, LIMK1 | Cognitive profile with strengths in language, deficits in visuospatial ability [16] |

| 22q11.2 | DiGeorge syndrome | TBX1 | Intellectual disability, psychiatric disorders [16] |

| 1q21.1 | 1q21.1 distal deletion/duplication | PRKAB2, FM05 | Developmental delay, intellectual disability [18] |

A recent single-cell transcriptomics study analyzing over 1 million cells across human brain development identified three distinct CNV groups with specific temporal and cellular enrichment patterns [17]:

- Group A (Neuron-enriched): CNVs affecting genes preferentially expressed in early fetal developing neurons, associated with synaptic signaling pathways.

- Group B (Precursor-enriched): CNVs affecting genes highly enriched in radial glia, related to cell cycle processes suggesting dysfunction in proliferation and differentiation.

- Postnatal enrichment: Both groups show enriched expression in intratelencephalic neurons that integrate cortical information during later development.

This research indicates that although NDDs are typically diagnosed in childhood or adolescence, the primary effects of genetic mutations on embryonic progenitor cells or early neurons may be most pronounced during fetal brain development, potentially programming subsequent developmental cascades [17].

Penetrance Considerations in Clinical Interpretation

Accurate penetrance estimates are crucial for clinical CNV interpretation. A 2025 study proposed a revised penetrance definition excluding background disease risk unrelated to the genetic variant, leading to significantly lower penetrance estimates for many recurrent CNVs associated with intellectual disability [18].

Table 2: Updated Penetrance Estimates for Selected Recurrent CNVs in Intellectual Disability

| CNV Locus | Previous Penetrance Estimate | Updated Penetrance Estimate | Key Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1q21.1 proximal duplication | 10-40% | ~0% | RBM8A [18] |

| 15q11.2 duplication (BP1-BP2) | 10-40% | 1-10% | NIPA1, NIPA2 [18] |

| 15q13.3 duplication | 10-40% | 1-10% | CHRNA7 [18] |

| 16p13.11 duplication | 10-40% | 1-10% | MYH11 [18] |

These recalculated estimates have important implications for genetic counseling, diagnosis, and prenatal reporting of recurrent CNVs, suggesting many previously considered pathogenic CNVs have substantially lower disease risk than previously reported [18].

CNVs in Cancer Pathogenesis

CNV-Driven Oncogenic Mechanisms

In cancer, somatic CNVs play critical roles in disrupting the balance between tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes [16]. CNVs can drive carcinogenesis through dosage effects on key cancer pathways, with specific patterns associated with cancer types, progression, and treatment outcomes [5].

Table 3: Clinically Significant CNVs in Cancer

| Cancer Type | Genomic Alteration | Affected Gene(s) | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | HER2 amplification | ERBB2 (HER2) | Targeted therapy response [16] |

| Various solid tumors | TP53 deletions | TP53 | Tumor progression, genomic instability [16] |

| Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) | Multiple CNVs | MCCC1-AS1 (lncRNA) | Shorter survival, potential prognostic biomarker [4] |

| Gastric, pancreatic, breast, colon cancers | Various CNVs | Multiple | Tumorigenesis initiation and progression [4] |

A multi-omics analysis of HPV-positive and HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) revealed CNV-driven long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) regulatory networks that influence cancer pathogenesis [4]. The study identified lncRNA MCCC1-AS1 as significantly associated with shorter survival time in patients with copy number gain, suggesting its potential as a prognostic biomarker [4].

CNV Detection Methodologies in Cancer Research

Multiple computational approaches exist for CNV detection from genomic data, each with distinct strengths and applications:

- ASCAT-NGS: Allele-Specific Copy number Analysis of Tumors for WGS data [5]

- CNVkit: Analysis of both whole-exome (WES) and whole-genome (WGS) sequencing data [5]

- FACETS: Analysis of WGS, WES, and targeted panel sequencing [5]

- HATCHet: Joint analysis of variants and duplications across tumor samples [5]

Factors affecting CNV calling accuracy include sequencing platform, sample preparation (FFPE vs. frozen), sequencing coverage (10-300X), and tumor ploidy [5]. For the most precise results, using multiple CNV calling tools is recommended rather than relying on a single standard approach [5].

CNVs in Parkinson's Disease Pathogenesis

CNV Associations in Parkinson's Disease

While genetic studies of Parkinson's disease (PD) have traditionally focused on single nucleotide variants (SNVs), recent large-scale analyses demonstrate that CNVs contribute significantly to PD risk, particularly in early-onset cases [12] [19].

Table 4: CNV Findings in Parkinson's Disease Genes

| Gene | Inheritance Pattern | CNV Types | Frequency in PD | Frequency in Controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRKN | Recessive | Deletions, duplications | 2.0% (48/2364) | 1.2% (36/2909) [12] |

| PARK7 | Recessive | Deletions | 0.1% (3/2364) | 0.1% (3/2909) [12] |

| SNCA | Dominant | Duplications, triplications | 0.1% (3/2364) | <0.1% (1/2909) [12] |

| LRRK2 | Dominant | Duplications | <0.1% (1/2364) | <0.1% (1/2909) [12] |

A large-scale analysis of 2,364 PD patients and 2,909 controls found that CNVs in PD-related genes were significantly enriched in patients (OR = 1.67, p = 0.03), with this association driven primarily by PRKN CNVs [12]. The association was particularly strong in early-onset PD (EOPD) patients (OR = 4.04, p = 7.4e-05) [12]. Overall, 0.9% of patients carried potentially disease-causing CNVs compared to 0.1% in controls [12].

PRKN CNV Characteristics and Clinical Correlations

The PRKN gene demonstrates particular susceptibility to CNVs, with a high validation rate of 95.4% [12]. Key characteristics include:

- The most frequent PRKN CNVs were Exon 2 duplications (32%) and Exon 4 deletions (18%) [12].

- PD patients with validated PRKN CNVs had significantly earlier age at onset (51.9 ± 17.9 years) compared to non-PRKN CNV carriers (60.9 ± 11.6 years, pₐdⱼ = 7e-07) [12].

- Patients with compound heterozygous variants (CNV plus pathogenic SNV) showed the earliest age at onset (34.3 ± 21.3 years), including four cases with juvenile PD (onset before age 21 years) [12].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide CNV Analysis Using Array Data

Application: CNV detection from genotyping array data for large cohort studies [12]

Workflow:

- DNA Quality Control: Assess DNA quality and concentration using fluorometry.

- Genotyping Array Processing: Hybridize to Illumina or Affymetrix arrays per manufacturer protocols.

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize signal intensity values (Log R Ratio - LRR, B Allele Frequency - BAF).

- CNV Calling: Process using PennCNV or similar algorithm with population frequency filters.

- Annotation: Annotate CNVs against gene databases and known pathogenic variants.

- Validation: Confirm findings using MLPA or qPCR for specific genes of interest.

Validation Approach: In a recent PD study, 119 of 137 detected CNVs in PD-related genes (87%) were validated using MLPA/qPCR [12].

Protocol 2: scRNA-seq CNV Calling for Tumor Heterogeneity

Application: Single-cell copy number variation analysis from RNA-seq data [14]

Workflow:

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing: Prepare libraries using 10X Genomics or similar platform.

- Quality Control: Filter cells by read count, gene detection, and mitochondrial percentage.

- Reference Selection: Identify normal diploid cells within dataset or use external reference.

- CNV Inference: Apply computational methods (InferCNV, copyKat, Numbat) to infer CNVs from expression patterns.

- Subclone Identification: Cluster cells based on similar CNV profiles.

- Integration: Correlate CNV profiles with gene expression programs.

Performance Considerations: A 2025 benchmarking study of six scRNA-seq CNV callers found that methods incorporating allelic information (CaSpER, Numbat) performed more robustly for large droplet-based datasets but required higher runtime [14].

Protocol 3: CNV-Seq for Diagnostic Applications

Application: Clinical detection of pathogenic CNVs in neurodevelopmental disorders [11]

Workflow:

- Sample Collection: Obtain peripheral blood, amniotic fluid, or chorionic villus samples.

- DNA Extraction: Use column-based or magnetic bead methods.

- Library Preparation: Fragment DNA and attach adapters for whole-genome sequencing.

- Low-Depth Sequencing: Sequence to ~0.1x coverage on Illumina or similar platforms.

- Read Alignment: Map to reference genome (GRCh38).

- CNV Calling: Identify regions with significant deviation from expected read depth.

- Pathogenicity Assessment: Classify CNVs using ACMG/ClinGen guidelines.

- Reporting: Issue clinical reports with interpretation of findings.

Performance Characteristics: In a study of 130 children with abnormal brain development, CNV-Seq identified genetic abnormalities in 32.3% of cases, with significantly higher diagnostic yield in syndromic (77.8%) versus non-syndromic (33.3%) cases [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Reagents and Resources for CNV Research

| Category | Specific Tools | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Lab Reagents | QIAamp DNA Micro Kit | DNA extraction from clinical samples | Optimized for low-input samples [11] |

| MLPA Probemixes (SALSA) | Targeted CNV validation | Gene-specific kits available for PRKN, PARK7, etc. [12] | |

| CN-500 NGS Platform | Low-depth whole genome sequencing | CNV-Seq applications [11] | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | CNV-Finder | Deep learning-based CNV detection | Integrates LSTM network; app-compatible output [20] |

| PennCNV | Array-based CNV calling | Handles LRR and BAF values from genotyping arrays [12] | |

| InferCNV | scRNA-seq CNV inference | Identifies CNVs and subclones in single-cell data [14] | |

| CNVkit | WES/WGS CNV detection | Flexible target enrichment designs [5] | |

| Data Resources | GENCODE | Gene annotation | Reference for non-coding RNA analysis [4] |

| ClinVar/GnomAD | Variant frequency and classification | Pathogenicity assessment [11] | |

| TCGA-HNSCC | Cancer multi-omics data | HPV-positive and negative HNSCC datasets [4] |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: CNV-Mediated Pathogenic Pathways Across Diseases. This systems biology view illustrates how CNVs disrupt distinct biological processes in neurodevelopmental disorders, cancer, and Parkinson's disease, leading to diverse clinical outcomes.

Diagram 2: Integrated CNV Analysis Workflow. This protocol outlines the key steps in comprehensive CNV analysis, from sample preparation through computational analysis to experimental validation and clinical interpretation.

CNVs represent a significant class of genetic variation with demonstrated roles across neurodevelopmental disorders, cancer, and Parkinson's disease. Through systems biology approaches that integrate multi-omics data, researchers can elucidate the complex mechanisms through which gene dosage alterations disrupt cellular networks and drive disease pathogenesis. The continued refinement of detection technologies, computational tools, and clinical interpretation frameworks will enhance our ability to translate CNV discoveries into improved diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Current research priorities include better characterization of low-penetrance CNVs, understanding the functional impact of non-coding CNVs, and developing more accurate single-cell CNV detection methods to resolve tumor heterogeneity. As these advances mature, CNV analysis will increasingly become a standard component of precision medicine approaches across diverse disease contexts.

The reductionist approach, which has long dominated molecular biology by focusing on the function of individual genes, is insufficient for explaining complex phenotypic outcomes [21]. The relationship between genotype and phenotype is too complicated to be ascribed to a change in a single gene, and traditional linkage tests cannot fully explain complex diseases [21]. Systems biology addresses this limitation by conceptualizing cellular functions as systems of interacting elements, requiring knowledge of component identity, dynamic behavior, and interactions between components [22]. This framework is particularly valuable for copy number variant (CNV) analysis, as it allows researchers to understand how structural genetic variations disrupt broader network architecture rather than merely affecting single gene dosage.

Modularity represents a fundamental design principle observed across biological systems, including protein-protein interaction networks, metabolic networks, and transcriptional regulation networks [21]. These functional modules—groups of genes or proteins with coordinated activities—serve as the building blocks of cellular organization. The shift from single-gene to network-level analysis enables researchers to understand how CNVs perturb these modules and their interactions, ultimately leading to disease phenotypes. This approach is revolutionizing our view of systems biology, genetic engineering, and disease mechanisms [21].

Methodological Approaches for Network Inference and Analysis

Network Inference from High-Throughput Data

Network inference constitutes a critical computational methodology for reconstructing gene regulatory networks (GRNs) from expression data, most commonly derived from RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq) technologies [23]. The fundamental challenge in this domain stems from the static nature of these measurements—each cell provides only a single timepoint of data, as measurement techniques typically involve cell lysis [23]. Researchers address this limitation through pseudo-temporal ordering of static single-cell expression data, either by administering stimuli and measuring responses at staggered intervals or through computational ordering methods [23].

The problem of network inference can be abstracted into a graph theory framework where genes represent nodes and regulatory relationships represent edges [23]. For N genes with expression levels represented by random variables {X1, X2, ..., XN}, each edge Xi → Xj represents a directional regulatory relationship. The output of network inference algorithms is typically a set of weighted edge predictions, where weights correspond to confidence levels for interactions existing in the true biological network [23]. Algorithm performance is evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves or precision-recall (PR) curves against gold standard datasets, such as those provided by DREAM Challenges [23].

Table 1: Major Classes of Network Inference Algorithms

| Algorithm Class | Key Principles | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation-based | Computes pairwise correlation coefficients between genes | Fast, scalable; useful for co-expression networks [23] | Cannot determine causal direction; high false positive rate for cascades [23] |

| Regression-based | Solves linear regression equations to predict gene expression | Predicts causal direction; resampling methods improve performance [23] | Assumes linear relationships; performs poorly on feed-forward loops [23] |

| Bayesian Methods | Represents interactions as conditional probabilities | Easily integrates prior knowledge [23] | Computationally expensive; cannot detect cycles in basic form [23] |

| Dynamic Bayesian Networks (DBNs) | Extends Bayesian methods to temporal data | Can detect feedback loops and cycles [23] | High computational complexity; requires temporal data [23] |

Module-Level Analysis Strategies

Gene module level analysis emphasizes groups or modules of genes rather than individual genes, reflecting the modular design of biological systems [21]. This approach can be categorized into three primary methodological frameworks:

Network-based approaches: Identify highly connected subgraphs in biological networks as modules [21]. These methods leverage the topological properties of interaction networks to detect densely interconnected regions that often correspond to functional units.

Expression-based approaches: Identify groups of co-expressed genes as modules through clustering algorithms applied to gene expression data [21]. These methods assume that genes with similar expression patterns across multiple conditions may be functionally related or co-regulated.

Prior pathways-based approaches: Utilize existing knowledge of biological pathways to define modules, then assess how these predefined modules are altered in different conditions [21].

Table 2: Network Concepts in Module Analysis

| Network Concept | Mathematical Definition | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Connectivity (Degree) | ( ki = \sum{j \neq i} a_{ij} ) [24] | Importance of a node in the network; hub genes may play key organizational roles [24] |

| Density | ( \frac{\sumi \sum{j \neq i} a_{ij}}{n(n-1)} = \frac{mean(k)}{n-1} ) [24] | Overall connectedness of the network; fraction of possible connections that actually exist [24] |

| Clustering Coefficient | Likelihood that connected nodes share common neighbors [24] | Measures modular organization and potential functional redundancy [24] |

| Topological Overlap | Measures the number of common neighbors between two nodes [24] | Identifies genes with similar network neighborhoods, potentially indicating functional similarity [24] |

Integrating CNV Analysis with Network Biology

CNV-Disease Association Framework

Copy number variations contribute substantially to human genetic variation and are increasingly implicated in disease associations and genome evolution [25]. The IHI-BMLLR (Integrating Heterogeneous Information sources with Biweight Mid-correlation and L1-regularized Logistic Regression under stability selection) framework represents a novel machine learning approach that predicts CNV-disease associations by integrating multiple data sources [25]. This method addresses key limitations of traditional CNV-disease association analyses by:

- Simultaneously considering all CNVs and genes rather than analyzing single variants in isolation [25]

- Integrating three data types (CNV, gene expression, and disease state labels) to provide insights into complex association mechanisms [25]

- Employing a self-adaptive biweight mid-correlation measure that is robust to outliers compared to Pearson correlation [25]

- Incorporating stability selection strategy to effectively reduce false positives [25]

The framework constructs a biological association network where nodes represent CNVs, genes, or diseases, and edges with scores represent correlations between pairs of nodes. A weighted path search algorithm then identifies significant CNV-disease path associations [25].

Application to Parkinson's Disease Research

Applying CNV analysis within a network framework has yielded significant insights in Parkinson's disease (PD) research. A large-scale CNV analysis in PD-related genes revealed that:

- CNVs are present in 2.4% of PD patients compared to 1.5% of controls, with enrichment driven particularly by PRKN CNVs [12]

- 0.9% of patients carried potentially disease-causing CNVs compared to 0.1% in controls [12]

- CNVs were especially enriched in early-onset PD patients (OR = 4.04, padj = 7.4e-05) [12]

- PRKN CNV carriers showed significantly earlier age at onset (51.9 ± 17.9 years) compared to non-carriers (60.9 ± 11.6 years, padj = 7e-07) [12]

These findings demonstrate how moving beyond single-gene models to network-level understanding reveals the systems-level impact of structural variants in complex disease.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Gene Co-Expression Network Construction

Purpose: To construct a gene co-expression network from RNA-Seq data for identification of functional modules.

Materials:

- RNA-Seq dataset (count matrix)

- High-performance computing environment with R/Python

- WGCNA R package (for weighted correlation network analysis)

- Bioinformatics visualization tools (Cytoscape)

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Filter genes based on expression variance (select genes with significantly higher coefficient of variation than expected for their expression level) [23].

- Correlation Matrix Calculation: Compute pairwise correlations between all selected genes using biweight mid-correlation (robust alternative to Pearson correlation) [25].

- Adjacency Matrix Construction: Transform correlation matrix into adjacency matrix using signed or unsigned network options based on biological assumptions.

- Network Module Detection: Apply hierarchical clustering with dynamic tree cutting to identify modules of highly interconnected genes [21].

- Module Characterization: Calculate module eigengenes (first principal component) and correlate with clinical traits or experimental conditions.

- Functional Enrichment Analysis: Use databases like GO, KEGG to identify biological processes and pathways enriched in each module.

- Network Visualization: Export module networks to Cytoscape for visualization and further analysis.

Validation: Evaluate module robustness through bootstrap resampling and compare with known pathway databases.

Protocol 2: CNV-Disease Path Association Mapping

Purpose: To identify significant paths connecting CNVs to diseases via intermediate genes.

Materials:

- CNV calling data (from array CGH or sequencing)

- Gene expression data (RNA-Seq or microarray)

- Clinical/disease status data

- IHI-BMLLR software (available from GitHub repository)

Procedure:

- Data Integration: Organize CNV, gene expression, and disease status data into standardized matrices with matched samples.

- CNV-Gene Correlation: Calculate correlation coefficients between CNVs and genes using self-adaptive biweight mid-correlation to handle outliers [25].

- Gene-Disease Association: Apply L1-regularized logistic regression (lasso) with stability selection to identify disease-associated genes while controlling false positives [25].

- Biological Network Construction: Integrate CNV-gene and gene-disease associations into a unified biological network.

- Weighted Path Search: Implement algorithm to identify top D path associations from CNVs to diseases via intermediate genes.

- Statistical Significance Testing: Assess significance of identified paths using permutation testing (comparing with fake data) [25].

- Biological Interpretation: Annotate significant paths with functional information and compare with existing knowledge.

Validation: For prostate cancer data application, IHI-BMLLR identified 212 significant paths, with top associations showing statistical significance in real versus fake data tests [25].

Visualization of Network Relationships

CNV to Disease Path Association Workflow

CNV to Disease Path Association Workflow: This diagram illustrates the IHI-BMLLR framework for identifying paths connecting CNVs to diseases through intermediate genes.

Network Module Identification Approaches

Network Module Identification Approaches: Three primary methods for identifying gene modules in biological networks.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Systems Biology CNV Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| CNV Databases | DGV, DGVa, dbVar, CNVD, DECIPHER [25] | Catalog known CNV-disease associations and population frequencies |

| Expression Data Repositories | GEO, SRA, TCGA, GTEx [26] | Provide publicly available gene expression data for network analysis |

| Network Analysis Software | WGCNA, Cytoscape, IHI-BMLLR [23] [25] | Construct, analyze, and visualize biological networks |

| Pathway Databases | GO, KEGG, Reactome | Provide prior knowledge for module annotation and interpretation |

| Benchmark Datasets | DREAM Challenges [23] | Gold standard networks for algorithm evaluation and benchmarking |

| Bioinformatics Environments | R/Bioconductor, Python | Programming environments for implementing analytical workflows |

The transition from single-gene models to network-level understanding represents a paradigm shift in how we approach CNV analysis in complex diseases. By employing systems biology frameworks that integrate multiple data types and analyze interactions at the module level, researchers can move beyond simplistic one-variant-one-gene models to comprehend how structural variants perturb entire biological systems. The methodologies and protocols outlined here provide a roadmap for implementing this network-based approach, with applications ranging from basic research to drug development. As these approaches mature, they promise to unlock deeper insights into disease mechanisms and identify novel therapeutic interventions that target network perturbations rather than individual gene defects.

In the context of copy number variant (CNV) analysis systems biology research, a fundamental challenge lies in moving beyond the mere identification of altered genomic regions to understanding their downstream functional consequences. Copy number variations can lead to dosage imbalances of key proteins, thereby perturbing the intricate networks of protein-protein interactions (PPIs) that govern cellular processes [27] [28]. These interaction networks are not random; they are organized with specific topological architectures where certain proteins, termed "central players," hold critical positions for network integrity and function [27] [29].

Disruption of these central players through CNVs can have disproportionate effects, potentially leading to disease phenotypes. Therefore, identifying these proteins through topological analysis becomes a crucial step in CNV research, enabling the prioritization of candidate genes and the elucidation of pathogenic mechanisms. This Application Note provides detailed protocols for the topological analysis of PPI networks to robustly identify these central players, framing the methodologies within a systems biology approach to CNV interpretation.

Background and Key Concepts

A PPI network is mathematically represented as a graph ( G=(V,E) ), where ( V ) is a set of proteins (nodes) and ( E ) is a set of physical interactions (edges) between them [29]. The topology of this graph reveals proteins with critical roles. Hub proteins, defined as highly connected nodes, are crucial for network robustness. They can be further classified into party hubs (interacting with most partners simultaneously, often within a functional module) and date hubs (connecting different modules and coordinating their activity) [27]. The centrality-lethality rule, which posits that highly connected proteins are more likely to be essential, underscores the biological importance of hubs [27]. Beyond simple connectivity, betweenness centrality identifies nodes that act as bridges, facilitating communication between different parts of the network [27]. Furthermore, PPI networks often exhibit a modular structure, comprising densely connected groups of proteins that perform discrete biological functions [30] [31]. Central players often reside in, or connect, these modules.

Table 1: Key Topological Properties for Identifying Central Players

| Property | Mathematical Definition | Biological Interpretation | Implication in CNV Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree Centrality | Number of edges incident to a node [27]. | Indicates a protein with many interacting partners; often a hub. | CNVs affecting high-degree nodes may cause widespread network dysfunction. |

| Betweenness Centrality | The fraction of shortest paths between all node pairs that pass through the node of interest [27]. | Identifies bottleneck proteins that connect functional modules. | CNVs in high-betweenness nodes may disrupt cross-module communication, leading to pleiotropic effects. |

| Clustering Coefficient | Measures the extent to which a node's neighbors are connected to each other [30]. | High values suggest a protein is part of a tightly knit functional module. | Helps contextualize a hub as a party hub within a module. |

| Eigenvector Centrality | A measure of a node's influence based on the influence of its neighbors. | Identifies nodes connected to other well-connected nodes. | Can pinpoint proteins central to influential network regions affected by CNVs. |

Protocols for Topological Analysis

This section outlines a step-by-step protocol for constructing a PPI network and calculating the key topological metrics described above.

Protocol 1: PPI Network Construction and Data Preprocessing

Objective: To build a high-confidence, context-specific PPI network from raw data. Materials: Protein interaction data (e.g., from BioGRID [32], STRING [32]), computational environment (e.g., R, Python with libraries like NetworkX, Cytoscape [28]). Workflow:

- Data Acquisition: Download PPI data for your organism of interest from public databases (e.g., BioGRID, STRING, species-specific databases like RicePPINet for rice [32]).

- Data Integration and Filtering:

- Integrate datasets while removing duplicate interactions.

- Apply confidence filters. For instance, use the topological scoring (TopS) algorithm [28] or other statistical tools (e.g., SAINT, CompPASS [28]) to assign confidence scores and retain only high-quality interactions. If using gene co-expression data from resources like RiceFREND [32], integrate it to support functionally relevant interactions.

- Network Construction: Represent the filtered interaction list as a graph. Each protein is a node, and each high-confidence interaction is an undirected edge. This graph is the input for all subsequent topological analyses.

The following diagram illustrates the key steps and decision points in the network construction workflow.

Protocol 2: Calculation of Topological Metrics

Objective: To compute quantitative metrics that identify topologically central nodes. Materials: The PPI network from Protocol 1, computational environment (R/Python with NetworkX, igraph; or Cytoscape with relevant plugins). Workflow:

- Calculate Node Degree: For each node, compute its degree ( k ), which is the number of connections it has. Nodes in the top ~10% of the degree distribution are often classified as hubs [27].

- Compute Betweenness Centrality: For each node, calculate the fraction of all shortest paths in the network that pass through it. This is a computationally intensive but crucial step for finding non-hub bottlenecks.

- Determine Clustering Coefficient: For each node, calculate the ratio between the number of existing links between its neighbors and the maximum possible number of such links. This helps characterize the local density around a node.

- Generate a Ranked List: Rank proteins based on each centrality measure. The top-ranked proteins according to degree and betweenness are candidate central players for further validation.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Topological Analysis

| Tool Name | Type/Environment | Key Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytoscape [28] | Standalone Software Platform | Network visualization and analysis. | User-friendly GUI; essential for initial exploration and visualization of the network. |

| NetworkX | Python Library | Package for complex network creation and analysis. | Ideal for scripting custom analysis pipelines; provides functions for all key metrics. |

| igraph | R/Python Library | Network analysis and visualization. | Efficient for handling large networks; used in R and Python environments. |

| TopS Algorithm [28] | R Script/Platform | Topological scoring for AP-MS data. | Used during data preprocessing (Protocol 1) to assign confidence scores to interactions. |

Advanced and Integrated Analysis

Moving beyond basic metrics, advanced topological methods can provide deeper biological insights, especially when analyzing the effects of perturbations like CNVs.

Module and Community Detection

Functional modules can be detected using algorithms like Markov Clustering (MCL) [31] or spectral analysis [30]. These methods partition the network into densely connected subgraphs (quasi-cliques) [30]. Once modules are identified, their biological coherence can be assessed using functional enrichment analysis with Gene Ontology (GO) terms. This helps determine if a central player's importance stems from its role within a critical functional module.

Analyzing Perturbed Networks

A powerful approach is to simulate CNV effects by perturbing the network. This involves removing nodes (e.g., proteins encoded by genes within a deleted CNV region) and observing the impact on global network properties like characteristic path length or connectivity [27] [31]. Tools like Topological Data Analysis (TDA) can identify Topological Network Modules (TNMs) that are sensitive to such perturbations, revealing fragile network regions [31].

The following diagram illustrates this integrated workflow, from a genetically perturbed cell to the identification of fragile network modules.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for PPI Network Mapping

| Reagent / Method | Function | Considerations for Topological Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) [33] | Detects binary protein-protein interactions in vivo. | Can yield high false-positive rates; requires stringent validation. Best for initial, large-scale network mapping. |

| Affinity Purification Mass Spectrometry (AP-MS) [33] [28] | Identifies proteins in a complex with a tagged bait protein. | Identifies multi-protein complexes, not direct binary interactions. TopS algorithm is designed to analyze AP-MS data [28]. |

| Membrane Yeast Two-Hybrid (MYTH) [33] | Specialized Y2H for membrane proteins. | Crucial for including integral membrane proteins, which are often absent from standard Y2H screens. |

| BioID [33] | Proximity-labeling method to identify proteins near a bait protein in live cells. | Captures transient interactions and spatial organization, providing a more dynamic view of the network. |

| HaloTag System [28] | Versatile protein tagging platform for pull-down assays. | Used with quantitative proteomics (e.g., dNSAF) to generate data compatible with topological scoring methods like TopS. |

Topological analysis of PPI networks provides a powerful, quantitative framework for identifying central players that are critical for network stability and function. When integrated with CNV data, this approach moves systems biology research from a catalog of genomic structural variations to a mechanistic understanding of their functional impact. By following the detailed protocols and utilizing the tools outlined in this Application Note, researchers can systematically prioritize candidate genes within CNV regions, uncover novel disease mechanisms, and identify potential therapeutic targets with greater confidence.

In the context of copy number variant (CNV) analysis and systems biology research, identifying causative genes from large genomic datasets remains a significant challenge. CNV studies, particularly those investigating complex disorders, often generate extensive lists of candidate genes within identified variant regions, many of which are variants of unknown significance [12] [34]. Gene prioritization addresses this bottleneck by systematically ranking candidate genes based on their likelihood of disease association, enabling researchers to focus validation efforts on the most promising targets [35]. Among various prioritization strategies, betweenness centrality has emerged as a powerful network-based metric for identifying crucial genes that may not be apparent through frequency or gene size alone [34] [36].

This Application Note provides detailed protocols for implementing betweenness centrality analysis within a comprehensive gene prioritization workflow, specifically tailored for CNV research in systems biology. We demonstrate how this approach can bridge the gap between large-scale genomic findings and biologically meaningful insights for researchers and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Foundation: Betweenness Centrality in Biological Networks

Network-Based Prioritization Principles

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks provide a biological context for interpreting gene lists derived from CNV studies. The fundamental premise of network-based gene prioritization is the "guilt-by-association" principle, which posits that genes associated with similar phenotypes tend to interact with each other or reside in the same network neighborhoods [35] [37]. Within these networks, topological analysis reveals nodes (genes/proteins) that occupy strategically important positions [36].

Betweenness Centrality Definition and Biological Significance

Betweenness centrality quantifies the influence a node has over information flow in a network by measuring how often it appears on the shortest paths between other nodes [38] [36]. Formally, it is calculated as:

[ C{spb}(v) = \sum{s≠v∈V}\sum{t≠v∈V}\frac{\sigma{st}(v)}{\sigma_{st}} ]

Where (\sigma{st}) is the number of shortest paths between nodes (s) and (t), and (\sigma{st}(v)) is the number of those paths passing through node (v) [36].

Biologically, proteins with high betweenness centrality often function as critical regulatory hubs or bottlenecks in cellular processes. While degree centrality (number of connections) identifies highly connected proteins, betweenness centrality reveals those that connect different network modules, making them potentially crucial for maintaining network integrity and facilitating communication between functional modules [36]. In disease contexts, these nodes represent attractive candidates for further investigation, as their disruption may have widespread consequences on cellular function [34].

Table 1: Comparison of Centrality Measures in Biological Networks

| Centrality Measure | Definition | Biological Interpretation | Use Case in Gene Prioritization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Betweenness Centrality | Number of shortest paths passing through a node | Identifies bridge proteins connecting network modules | Finding critical regulators in CNV regions |

| Degree Centrality | Number of direct connections to a node | Identifies highly interactive proteins | Finding hub proteins in disease networks |

| Closeness Centrality | Average distance to all other nodes | Identifies proteins that can quickly interact with others | Finding rapidly responding elements in signaling |

| Eigenvector Centrality | Connections to important nodes | Identifies proteins in influential neighborhoods | Finding proteins in key functional complexes |

Computational Protocol: Betweenness Centrality Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for gene prioritization using betweenness centrality analysis:

Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: Input Gene List Preparation

- Objective: Compile candidate genes from CNV analysis for prioritization

- Procedure:

- Notes: For CNVs of unknown significance, include all genes within the variant region. For larger CNVs, consider focusing on genes with brain-relevant expression for neurodevelopmental disorders [34]

Step 2: PPI Network Construction

- Objective: Build a comprehensive protein-protein interaction network for candidate genes

- Procedure:

- Access the STRING database (https://string-db.org/) or IMEx consortium databases [34] [39]

- Input candidate gene list using the batch search functionality

- Set confidence score threshold to ≥ 0.7 (high confidence) to minimize false positives

- Include first shell of interactors not in the original list to expand network context

- Export network in format compatible with Cytoscape (e.g., XGMML, SIF, or TSV format)

- Notes: The resulting network typically contains thousands of nodes and edges, providing sufficient complexity for meaningful centrality analysis [34]

Step 3: Betweenness Centrality Calculation

- Objective: Compute betweenness centrality values for all nodes in the network

- Procedure:

- Import network file into Cytoscape (version 3.8.0 or higher)

- Install the "NetworkAnalyzer" plugin if not already available

- Run NetworkAnalyzer via Tools > NetworkAnalyzer > Network Analysis > Analyze Network

- Set parameters to compute directed network metrics if working with directed interactions

- Execute analysis and export results table containing betweenness centrality values

- Alternative Tools: igraph (R/Python), NetworkX (Python), or custom scripts

- Validation: Verify calculation by comparing with known high-betweenness nodes (e.g., TP53 in cancer networks) [39]

Step 4: Gene Prioritization and Ranking

- Objective: Generate prioritized candidate gene list based on betweenness centrality

- Procedure:

- Sort genes by betweenness centrality values in descending order

- Normalize betweenness scores to percentage of maximum value for cross-network comparison

- Apply additional filters based on expression relevance (e.g., brain expression for neurological disorders)

- Integrate with other evidence sources (e.g., CNV frequency, functional predictions)

- Generate final ranked list for experimental validation

- Notes: Genes ranking in the top 5-10% by betweenness centrality typically represent the most promising candidates [34]

Experimental Validation Protocol

Functional Validation Workflow

After computational prioritization, selected candidates require experimental validation. The following workflow outlines key validation steps:

CNV Confirmation Using MLPA/qPCR

- Objective: Experimentally validate putative CNVs identified through genomic screening

- Background: MLPA (Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification) provides a targeted method for confirming copy number changes in specific genes [12]

- Reagents:

- SALSA MLPA probemix for target genes

- DNA polymerase with buffer

- Capillary electrophoresis system

- Procedure:

- Design MLPA probes for exons of candidate genes prioritized by betweenness centrality

- Amplify target regions using 50-100ng genomic DNA according to manufacturer's protocol

- Separate amplification products by capillary electrophoresis

- Analyze peak patterns and compare to reference samples

- Calculate copy number ratios using Coffalyser.Net or similar software

- Quality Control: Include positive and negative controls in each run

- Validation: In Parkinson's disease research, this approach achieved 87% validation rate for CNVs in PD-related genes [12]

Functional Characterization in Cellular Models

- Objective: Assess functional impact of candidate gene perturbation in relevant model systems

- Procedure:

- Select appropriate cell line based on disease context (e.g., neuronal lines for neurodevelopmental disorders)

- Implement gene knockdown using siRNA or CRISPRi for high-betweenness candidates

- Assess phenotypic readouts relevant to the disease mechanism

- Measure expression changes in pathway markers via RT-qPCR or RNA-seq

- Validate rescue experiments through gene overexpression

- Case Example: In ASD research, prioritization revealed enrichment in ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis and cannabinoid signaling pathways, guiding functional validation [34]

Application Example: ASD Case Study

Implementation and Results

A recent systems biology study demonstrated the application of betweenness centrality for gene prioritization in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [34]. Researchers constructed a PPI network comprising 12,598 nodes and 286,266 edges from SFARI database genes and their interactors. Betweenness centrality analysis identified several high-priority candidates, including CDC5L, RYBP, and MEOX2, which were subsequently validated through pathway enrichment analysis.

Table 2: Top Ranked Genes by Betweenness Centrality in ASD Network Analysis

| Gene Symbol | SFARI Category | Betweenness Centrality | Relative Betweenness (%) | Brain Expression (TPM) | Known Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESR1 | - | 0.0441 | 100.0 | 1.334 | - |

| LRRK2 | - | 0.0349 | 79.14 | 4.878 | Parkinson's Disease |

| APP | - | 0.0240 | 54.42 | 561.1 | Alzheimer's Disease |

| JUN | - | 0.0200 | 45.35 | 97.62 | - |

| CUL3 | 1 | 0.0150 | 34.01 | 22.88 | ASD |

| DISC1 | 2 | 0.0169 | 38.32 | 2.495 | Psychiatric Disorders |

| YWHAG | 3 | 0.0097 | 22.00 | 554.5 | Developmental Disorders |

| MAPT | 3 | 0.0096 | 21.77 | 223.0 | Parkinson's/Alzheimer's |

Pathway Enrichment Analysis

- Objective: Identify biological pathways enriched among high-betweenness centrality genes

- Procedure:

- Extract genes with betweenness centrality values above the 90th percentile

- Perform over-representation analysis using DAVID, g:Profiler, or similar tools

- Apply Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction (FDR < 0.05)

- Interpret significantly enriched pathways in disease context

- Findings: In the ASD study, betweenness-based prioritization revealed significant enrichments in ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis and cannabinoid receptor signaling pathways, suggesting their potential perturbation in ASD pathogenesis [34]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CNV Validation and Functional Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Validation Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNV Confirmation | SALSA MLPA probemixes | Targeted CNV detection | Validation of PRKN, SNCA CNVs in Parkinson's study [12] |

| Gene Expression Analysis | TaqMan Copy Number Assays | qPCR-based CNV quantification | Absolute quantification of gene copy number |

| Network Analysis Tools | Cytoscape with NetworkAnalyzer | Network construction and centrality calculation | Betweenness centrality calculation in PPI networks [34] [39] |

| PPI Databases | STRING, IMEx Consortium | Source of validated protein interactions | Building disease-specific networks [34] [39] |

| Functional Validation | siRNA libraries, CRISPR-Cas9 | Gene knockdown/knockout | Perturbation of high-betweenness candidates [34] |

| Pathway Analysis | DAVID, RSpider | Functional enrichment analysis | Identifying dysregulated pathways [34] [39] |

Technical Considerations and Limitations

Methodological Challenges

- Network Quality: Betweenness centrality results depend heavily on the completeness and quality of the underlying PPI data. Incomplete networks may miss important interactions [34] [37]

- Tissue Specificity: Generic PPI networks may not reflect tissue-specific interactions relevant to the disease context [34]

- Computational Demands: Betweenness centrality calculation has high computational complexity (O(VE) for unweighted networks), making it challenging for very large networks [36]

- Integration with Other Evidence: Betweenness centrality should be integrated with other genomic evidence (e.g., expression data, variant frequency) for robust prioritization [39]

Integration with CNV Analysis Pipelines

For comprehensive CNV interpretation in systems biology research, betweenness centrality analysis should be integrated into a broader analytical framework:

- CNV Detection: Identify candidate regions via array-CGH or sequencing

- Gene Extraction: Compile genes within CNV boundaries

- Network Prioritization: Apply betweenness centrality analysis

- Functional Annotation: Integrate expression, pathway, and literature data

- Experimental Validation: Confirm high-priority targets through molecular assays

This integrated approach facilitates the transition from genomic findings to biological insights, accelerating the identification of clinically relevant genes in CNV studies.

Copy number variants (CNVs) are major genetic alterations that can dramatically influence gene dosage and, consequently, cellular function and disease susceptibility [8]. In oncology, systematic analysis of CNVs across pan-cancer datasets has revealed their significant role in tumorigenesis by dysregulating key biological pathways [40] [41]. A prime example is the discovery of frequent amplification of the UBE2T gene, which encodes a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, linking a specific CNV event directly to the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) [40]. This application note details a systems biology framework for performing pathway enrichment analysis to connect CNV data to core biological processes, using ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis as a central case study within a broader thesis on CNV analysis.

Data Analysis: UBE2T as a Case Study Connecting CNVs to Ubiquitination

A comprehensive pan-cancer analysis illustrates how CNV data can be integrated with transcriptomics and clinical outcomes to uncover biologically significant pathways. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings for UBE2T.

Table 1: UBE2T CNV Frequencies and Association with Clinical Outcomes in Select Cancers

| Cancer Type | Predominant UBE2T Genetic Alteration | Frequency of Amplification (%) | Correlation with Overall Survival (Hazard Ratio >1 indicates poor prognosis) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Cancers (Pan-Cancer) | Amplification [40] | High (Data from GSCALite) [40] | Significant association with poor prognosis across multiple cancers [40] |

| Breast Cancer | Elevated mRNA expression [40] | Not Specified | Reduced OS and PFS [40] |

| Ovarian Cancer | Elevated expression [40] | Not Specified | Reduced OS and PFS [40] |

| Pancreatic Cancer (Cell Lines) | Elevated mRNA/Protein vs. normal HPDE cells [40] | Not Specified | Implicated in progression [40] |

Table 2: Enriched Biological Pathways Associated with UBE2T Overexpression (from Gene Set Enrichment Analysis)

| Pathway Name | Functional Category | Proposed Role in Oncogenesis |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Cycle | Cellular proliferation | Drives unchecked cell division [40] |

| Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis | Protein homeostasis | Core mechanism of UBE2T action; dysregulated degradation of tumor suppressors [40] |

| p53 signaling pathway | DNA damage response & apoptosis | May facilitate inactivation of p53 tumor suppressor network [40] |

| Mismatch repair | Genomic stability | Contributes to mutator phenotype [40] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Omics CNV and Pathway Integration Workflow

This protocol outlines steps to identify CNV-driven pathway dysregulation, as employed in recent studies [40] [41].

1. CNV Ascertainment and Gene-Level Annotation:

- Input Data: Whole-exome sequencing (WES) or whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data from cohort studies (e.g., UK Biobank, TCGA) [8] [41].

- Detection Method: Utilize haplotype-informed CNV detection tools capable of identifying sub-exonic and focal CNVs within segmental duplications (e.g., methods described for UK Biobank analysis) [8]. For lower-coverage data, machine learning-based classifiers like

dudeMLcan be applied [42]. - Annotation: Map CNV coordinates to gene regions. Classify events as gene-level deletions (potential loss-of-function), duplications (potential increased dosage), or partial exon alterations [8].

2. Integration with Transcriptomic Data:

- Data Source: Obtain matched RNA-Seq data from repositories like TCGA or GTEx [40].

- Correlation Analysis: Perform statistical testing (e.g., Wilcoxon test) to compare expression levels of target genes (e.g., UBE2T) between tumors with CNV amplification and normal tissues or non-amplified tumors [40].

- Validation: Confirm protein-level expression using immunohistochemistry data from platforms like UALCAN or perform in vitro validation via western blotting on relevant cell lines [40].

3. Pathway Enrichment Analysis:

- Gene List Input: Generate a list of genes significantly overexpressed and associated with frequent CNV amplification.

- Enrichment Tools: Use R/Bioconductor packages (e.g.,

clusterProfiler) or web-based tools like GSEA. - Databases: Query Gene Ontology (GO) Biological Process and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases [40].

- Interpretation: Identify significantly enriched pathways (adjusted p-value < 0.05). Focus on coherent pathways like "ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis" or "cell cycle" to build mechanistic hypotheses.

Protocol 2: Functional Validation of a CNV-Gene-Pathway Link

This protocol details experimental validation for a candidate gene (e.g., UBE2T) identified in Protocol 1.

1. In Vitro Cell Line Modeling:

- Cell Culture: Acquire relevant cancer cell lines (e.g., pancreatic cancer lines PANC1, ASPC) and a normal epithelial control line (e.g., HPDE for pancreas). Culture in appropriate medium (e.g., DMEM with 10% FBS, penicillin/streptomycin) at 37°C with 5% CO₂ [40].

- Gene Expression Analysis:

- RNA Extraction: Lyse cells in RNAiso Plus or similar reagent.

- RT-qPCR: Synthesize cDNA and perform quantitative PCR using primers for the target gene and a housekeeping control (e.g., ACTB). Calculate relative expression using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method [40].

- Protein Expression Analysis:

- Western Blotting: Prepare cell lysates in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors. Separate 20 µg total protein by SDS-PAGE, transfer to PVDF membrane, and block with 5% BSA.

- Immunoblotting: Incubate with primary antibodies (e.g., anti-UBE2T at 1:2000, anti-β-actin at 1:2000) overnight at 4°C, followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Detect using chemiluminescent substrate [40].

2. Phenotypic Assays: