Integrating Multi-Omics Data: Systems Biology Approaches for Unlocking Disease Mechanisms and Advancing Precision Medicine

The integration of multi-omics data—encompassing genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—is revolutionizing biomedical research by providing a holistic view of biological systems.

Integrating Multi-Omics Data: Systems Biology Approaches for Unlocking Disease Mechanisms and Advancing Precision Medicine

Abstract

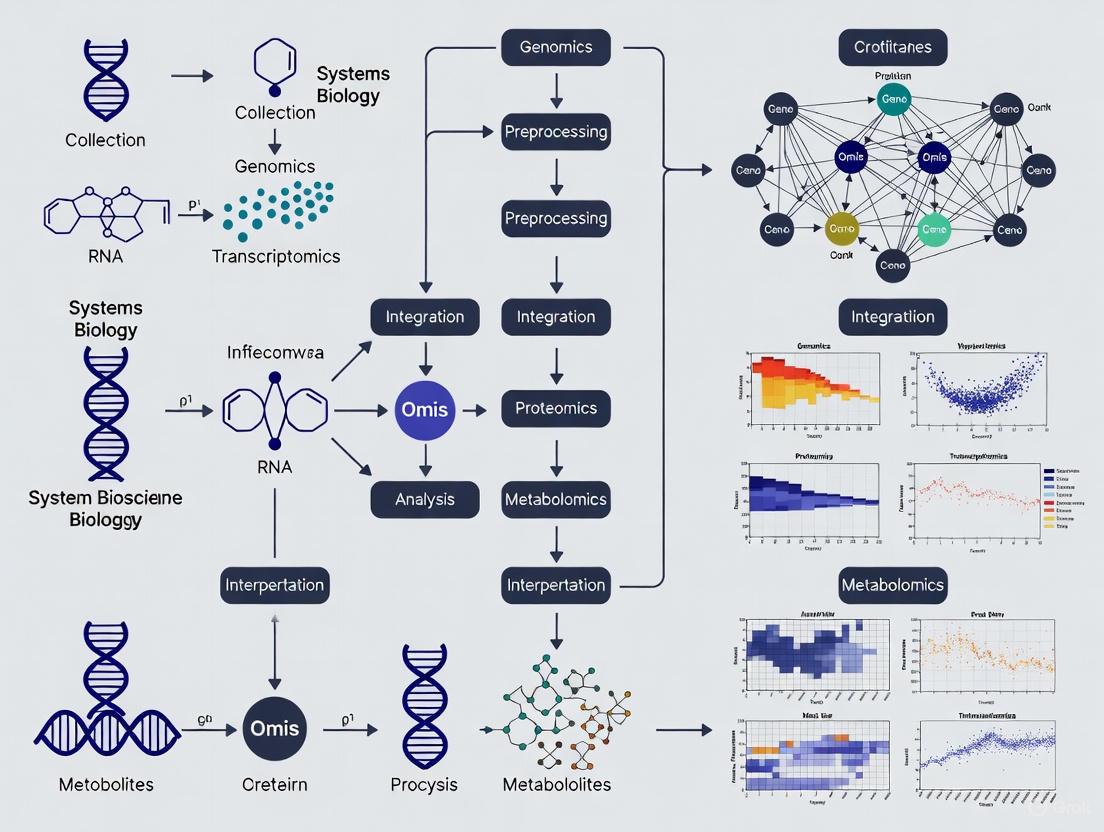

The integration of multi-omics data—encompassing genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—is revolutionizing biomedical research by providing a holistic view of biological systems. This article offers a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the foundational concepts, methodologies, and practical applications of systems biology for multi-omics data integration. We explore the significant challenges of data heterogeneity and high-dimensionality, review state-of-the-art computational methods from classical statistics to deep learning, and provide actionable strategies for troubleshooting and optimization. Through real-world case studies and comparative analysis of tools and validation techniques, this article demonstrates how effective multi-omics integration is pivotal for uncovering complex disease mechanisms, identifying robust biomarkers, and accelerating the development of targeted therapies and personalized treatment strategies.

The Multi-Omics Landscape: Core Concepts, Data Types, and Integration Challenges in Systems Biology

Multi-omics represents the integrative analysis of multiple omics technologies to gain a comprehensive understanding of biological systems and genotype-to-phenotype relationships [1]. This approach combines various molecular data layers—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics, and metabolomics—to construct holistic models of biological mechanisms that cannot be fully understood through single-omics studies alone [2] [3]. In the framework of systems biology, multi-omics integration provides unprecedented opportunities to elucidate complex molecular interactions associated with human diseases, particularly multifactorial conditions such as cancer, cardiovascular disorders, and neurodegenerative diseases [3]. The technological evolution and declining costs of high-throughput data generation have revolutionized biomedical research, enabling the collection of large-scale datasets across multiple biological layers and creating new requirements for specialized analytics that can capture the systemic properties of investigated conditions [2] [3].

Systems biology approaches multi-omics data integration through both knowledge-driven and data-driven strategies [4]. Knowledge-driven methods map molecular entities onto known biological pathways and networks, facilitating hypothesis generation within established knowledge domains. In contrast, data-driven strategies depend primarily on the datasets themselves, applying multivariate statistics and machine learning to identify patterns and relationships in a more unbiased manner [4]. The virtual space of translational research serves as the confluence point where biological findings are investigated for clinical applications, and medical needs directly guide specific biological experiments [2]. Within this space, systems bioinformatics has emerged as a crucial discipline that focuses on integrating information across different biological levels using both bottom-up approaches from systems biology and data-driven top-down approaches from bioinformatics [2].

Core Omics Technologies and Their Relationships

Defining the Omics Landscape

Omics technologies provide comprehensive, global assessments of biological molecules within an organism or environmental sample [1]. Each omics layer captures a distinct aspect of biological organization and function, together forming a multi-level information flow that systems biology seeks to integrate.

- Genomics: The study of an organism's complete set of DNA, including both coding and non-coding regions, and how different genes interact with each other and with the environment [1]. Genomics establishes the fundamental genetic template that influences all downstream molecular processes.

- Epigenomics: The study of chemical compounds and proteins that attach to DNA and modify gene expression without altering the DNA sequence itself [1]. Epigenomic modifications include DNA methylation and histone modifications, which serve as regulatory mechanisms that influence cellular phenotype.

- Transcriptomics: The study of the complete set of RNA transcripts (the transcriptome) produced by the genome at a specific time [1]. Transcriptomics reveals which genes are actively being expressed and provides insights into regulatory mechanisms operating at the RNA level.

- Proteomics: The study of the structure, function, composition, and interactions of the complete set of proteins (the proteome) present in a biological system at a certain time [1] [5]. Proteomics bridges the information flow from genes to functional effectors.

- Metabolomics: The study of all metabolites present in a biological system, particularly in relation to genetic and environmental influences [1]. Metabolomics provides the closest link to phenotypic expression, capturing the functional outputs of cellular processes.

Table 1: Core Omics Technologies in Multi-Omics Research

| Omics Type | Molecule Class Studied | Key Technologies | Biological Information Provided |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA | NGS, WGS, SNP arrays | Genetic blueprint, variants, polymorphisms |

| Epigenomics | DNA modifications | ChIP-seq, bisulfite sequencing | Gene regulation, chromatin organization |

| Transcriptomics | RNA | RNA-seq, microarrays | Gene expression, alternative splicing |

| Proteomics | Proteins | MS, protein arrays | Protein abundance, post-translational modifications |

| Metabolomics | Metabolites | GC/MS, LC/MS, NMR | Metabolic fluxes, pathway activities |

Biological Relationships Between Omics Layers

The relationship between different omics layers is complex and bidirectional, with each layer capable of influencing others through multiple regulatory mechanisms [1]. Genomics provides the foundational template, but transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics capture dynamic molecular responses to genetic and environmental influences. Epigenomic modifications serve as intermediary regulatory mechanisms that modulate information flow from genome to transcriptome. The proteome represents the functional effector layer, while the metabolome provides the most immediate reflection of phenotypic status, positioned downstream in the biological information flow but capable of exerting feedback regulation on upstream processes.

Biological Information Flow in Multi-Omics - This diagram illustrates the complex bidirectional relationships between different omics layers, showing both forward information flow and feedback regulatory mechanisms.

Computational Methods for Multi-Omics Data Integration

Integration Strategies and Methodologies

The integration of multi-omics data presents significant computational challenges due to high dimensionality, heterogeneity, and technical variations across platforms [2] [3]. Computational methods for multi-omics integration can be broadly categorized based on their approach to handling multiple data layers and the scientific objectives they aim to address.

- Early Integration: Combines raw data matrices from different omics layers before analysis, requiring extensive normalization to address technical variations. This approach can capture complex interactions but may be confounded by platform-specific biases [6].

- Intermediate Integration: Employs methods that learn joint representations of separate datasets that can be used for subsequent analysis tasks. This includes dimensionality reduction techniques that extract latent factors representing shared variations across omics layers [2].

- Late Integration: Analyzes each omics dataset separately and combines the results at the decision level. While more robust to technical variations, this approach may miss subtle cross-omics interactions [6].

- Network-Based Integration: Constructs molecular networks where nodes represent biological entities and edges represent functional relationships. Network approaches provide a holistic view of relationships among biological components in health and disease [3].

Table 2: Computational Methods for Multi-Omics Integration

| Integration Type | Key Methods | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration | Concatenation, Multi-block Analysis | Captures cross-omics interactions | Sensitive to technical noise and missing data |

| Intermediate Integration | MOFA, iCluster, SMFA | Learns robust joint representations | Complex parameter optimization |

| Late Integration | Ensemble Methods, Classifier Fusion | Robust to platform differences | May miss subtle cross-omics relationships |

| Network-Based Integration | Graph Convolutional Networks | Models biological context | Dependent on prior knowledge quality |

Advanced Integration Frameworks

Recent advances in multi-omics integration have introduced sophisticated frameworks designed to capture complex relationships within and between omics layers. SynOmics represents a cutting-edge graph convolutional network framework that improves multi-omics integration by constructing omics networks in the feature space and modeling both within- and cross-omics dependencies [6]. Unlike traditional approaches that rely on early or late integration strategies, SynOmics adopts a parallel learning strategy to process feature-level interactions at each layer of the model, enabling simultaneous learning of intra-omics and inter-omics relationships [6].

The OmicsAnalyst platform provides a user-friendly web-based implementation of various data-driven integration approaches, organized into three visual analytics tracks: correlation network analysis, cluster heatmap analysis, and dimension reduction analysis [4]. This platform lowers the access barriers to well-established methods for multi-omics integration through novel visual analytics, making sophisticated integration techniques accessible to researchers without extensive computational backgrounds [4].

Multi-Omics Data Integration Framework - This diagram illustrates the main computational strategies for integrating multi-omics data and their relationships to key research outputs.

Experimental Design and Workflow for Multi-Omics Studies

Multi-Omics Study Design Considerations

Designing robust multi-omics studies requires careful consideration of several factors to ensure biological relevance and technical feasibility. The selection of omics combinations should be guided by the scientific objectives and biological questions under investigation [2]. Studies aiming to understand regulatory processes may prioritize genomics, epigenomics, and transcriptomics, while investigations of functional phenotypes might emphasize transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. Sample collection strategies must account for the specific requirements of different omics technologies, including sample preservation methods, storage conditions, and input material requirements [2]. Experimental protocols should incorporate appropriate controls and replication strategies to address technical variability while maximizing biological insights within budget constraints.

Based on analysis of recent multi-omics studies, five key scientific objectives have been identified that particularly benefit from multi-omics approaches: (i) detection of disease-associated molecular patterns, (ii) subtype identification, (iii) diagnosis/prognosis, (iv) drug response prediction, and (v) understanding regulatory processes [2]. Each objective may require different combinations of omics types and computational approaches for optimal results. For instance, cancer subtyping frequently combines genomics, transcriptomics, and epigenomics to identify molecular subtypes with clinical relevance, while drug response prediction may integrate genomics with proteomics and metabolomics to capture both genetic determinants and functional states influencing treatment outcomes [2].

Data Processing and Quality Control Workflow

The analytical workflow for multi-omics data requires meticulous attention to data quality, normalization, and batch effect correction. The OmicsAnalyst platform implements a comprehensive data processing pipeline including data upload and annotation, missing value estimation, data filtering, identification of significant features, quality checking, and normalization/scaling [4]. Specific considerations for each step include:

- Missing Value Estimation: Features with excessive missing values may be excluded, or missing values may be estimated using established imputation methods appropriate for the specific omics data type [4].

- Data Filtering: Non-specific filtering based on variance measures (e.g., inter-quantile ranges) or abundance levels reduces dimensionality by excluding uninformative features while preserving biological signal [4].

- Normalization and Scaling: Different omics data types require specific normalization approaches to address technical variations and make datasets more "integrable" by sharing similar distributions [4].

- Quality Assessment: Visual assessment through density plots, PCA plots, and t-SNE plots helps identify batch effects, outliers, and other technical artifacts that might confound integration [4].

Multi-Omics Experimental Workflow - This diagram outlines the key stages in a comprehensive multi-omics study, from sample collection to biological interpretation and clinical translation.

Visualization and Interpretation of Multi-Omics Data

Visual Analytics Strategies

Effective visualization is crucial for interpreting complex multi-omics datasets and extracting meaningful biological insights. The PTools Cellular Overview implements a sophisticated multi-omics visualization approach that enables simultaneous visualization of up to four types of omics data on organism-scale metabolic network diagrams [7]. This tool uses different "visual channels" to represent distinct omics datasets—for example, displaying transcriptomics data as reaction arrow colors, proteomics data as reaction arrow thicknesses, and metabolomics data as metabolite node colors or thicknesses [7]. This coordinated multi-channel visualization facilitates direct comparison of different molecular measurements within their biological context.

OmicsAnalyst organizes visual analytics into three complementary tracks: correlation network analysis, cluster heatmap analysis, and dimension reduction analysis [4]. The correlation network analysis track identifies and visualizes relationships between key features from different omics datasets, offering both univariate methods (e.g., Pearson correlation) and multivariate methods (e.g., partial correlation) to compute pairwise similarities while controlling for potential confounding effects [4]. The cluster heatmap analysis track implements multi-view clustering algorithms including spectral clustering, perturbation-based clustering, and similarity network fusion to identify sample subgroups based on integrated molecular profiles [4]. The dimension reduction analysis track applies multivariate techniques to reveal global data structures, allowing exploration of scores, loadings, and biplots in interactive 3D scatter plots [4].

Advanced Visualization Techniques

Advanced visualization tools incorporate features such as semantic zooming, animation, and interactive data exploration to address the complexity of multi-omics data. Semantic zooming adjusts the level of detail displayed based on zoom level, showing pathway overviews at low magnification and detailed molecular information when zoomed in [7]. Animation capabilities enable visualization of time-course data, allowing researchers to observe dynamic changes in molecular profiles across experimental conditions or disease progression [7]. Interactive features include the ability to adjust color and thickness mappings to optimize information display and the generation of pop-up graphs showing detailed data values for specific molecular entities [7].

Network-based visualization approaches have proven particularly valuable for representing complex relationships in multi-omics data. These approaches employ edge bundling to aggregate similar connections, concentric circular layouts to evaluate focal nodes and hierarchical relationships, and 3D network visualization for deeper perspective on feature relationships [4]. When biological features are properly annotated during data processing, these visualization systems can perform enrichment analysis on selected node groups to identify overrepresented biological pathways, either through manual selection or automatic module detection algorithms [4].

Applications in Translational Medicine and Complex Diseases

Disease Subtyping and Biomarker Discovery

Multi-omics approaches have demonstrated particular value in identifying molecular subtypes of complex diseases that may appear homogeneous clinically but exhibit distinct molecular characteristics with implications for prognosis and treatment selection. Cancer research has extensively leveraged multi-omics stratification, combining genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic data to define molecular subtypes with distinct clinical outcomes and therapeutic vulnerabilities [2]. Beyond oncology, multi-omics subtyping has been applied to neurological disorders, autoimmune conditions, and metabolic diseases, revealing pathogenic heterogeneity that informs targeted intervention strategies [3].

Biomarker discovery represents another major application area where multi-omics integration provides significant advantages over single-omics approaches. By combining information across molecular layers, multi-omics analyses can identify biomarker panels with improved sensitivity and specificity for early disease detection, prognosis prediction, and treatment response monitoring [3]. Integrated analysis of genomics and metabolomics has uncovered genetic regulators of metabolic pathways that serve as biomarkers for disease risk, while combined transcriptomics and proteomics has revealed post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms that influence therapeutic efficacy [2] [3].

Drug Response Prediction and Therapeutic Development

Understanding the molecular determinants of drug response is a crucial application of multi-omics integration in pharmaceutical research and development. Multi-omics profiling of model systems and patient samples has identified molecular features at multiple biological levels that influence drug sensitivity and resistance mechanisms [2]. Genomics reveals inherited genetic variants affecting drug metabolism and target structure, transcriptomics captures expression states of drug targets and resistance mechanisms, proteomics characterizes functional protein abundances and modifications直接影响 drug interactions, and metabolomics profiles the metabolic context that influences drug efficacy and toxicity [2] [3].

The integration of multi-omics data has enabled the development of more predictive models of drug response through machine learning approaches that incorporate diverse molecular features. For example, the SynOmics framework has demonstrated superior performance in predicting cancer drug responses by capturing both within-omics and cross-omics dependencies through graph convolutional networks [6]. These integrated models facilitate the identification of patient subgroups most likely to benefit from specific treatments, supporting precision medicine approaches that match therapies to individual molecular profiles [6].

Multi-Omics Data Repositories

The expansion of multi-omics research has been accompanied by the development of specialized data repositories that provide curated access to integrated multi-omics datasets. These resources support method development, meta-analysis, and secondary research applications that leverage existing data to generate new biological insights.

Table 3: Multi-Omics Data Resources and Repositories

| Resource Name | Omics Content | Species | Primary Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics | Human | Pan-cancer atlas |

| Answer ALS | Whole-genome sequencing, RNA transcriptomics, ATAC-sequencing, proteomics | Human | Neurodegenerative disease |

| Fibromine | Transcriptomics, proteomics | Human/Mouse | Fibrosis research |

| DevOmics | Gene expression, DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin accessibility | Human/Mouse | Developmental biology |

| jMorp | Genomics, methylomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics | Human | Population diversity |

Essential Computational Tools and Reagents

Successful multi-omics studies require both computational tools for data analysis and experimental reagents for data generation. The selection of appropriate tools and reagents should be guided by the specific research objectives, omics technologies employed, and analytical approaches planned.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Studies

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Reagents | NGS library prep kits | Nucleic acid library construction | Platform-specific protocols required |

| Mass Spectrometry Reagents | Proteomics sample prep kits | Protein extraction, digestion, labeling | Compatibility with LC-MS systems |

| Metabolomics Standards | Reference metabolite libraries | Metabolite identification | Retention time indexing crucial |

| Epigenomics Reagents | Antibodies for ChIP-seq | Target-specific chromatin immunoprecipitation | Validation of antibody specificity essential |

| Multi-omics Integration Tools | OmicsAnalyst, SynOmics, PTools | Data integration and visualization | Method selection depends on study objectives |

Future Directions in Multi-Omics Research

Emerging Technologies and Approaches

The field of multi-omics research continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging technologies poised to expand capabilities for biological discovery. Single-cell multi-omics technologies enable researchers to study molecular relationships at the finest resolution possible, identifying rare cell types and cell-to-cell variations that may be obscured in bulk tissue analyses [1]. Since single-cell DNA and RNA sequencing were named "2013 Method of the Year" by Nature, these approaches have made important contributions to understanding biology and disease mechanisms, and their integration with other single-cell omics measurements will provide unprecedented resolution of cellular heterogeneity [1].

Spatial multi-omics represents another frontier, preserving and analyzing the spatial context of molecular measurements within tissues and biological structures [1]. Just as single omics techniques cannot provide a complete picture of biological mechanisms, single-cell analyses are necessarily limited without spatial context. Spatial transcriptomics has already revealed tumor microenvironment-specific characteristics that affect treatment responses, and the combination of multiple spatial omics approaches has an important future in scientific research [1]. These technologies bridge the gap between molecular profiling and tissue morphology, enabling direct correlation of multi-omics signatures with histological features and tissue organization.

Computational Innovations and Challenges

As multi-omics technologies advance, computational methods must evolve to address new challenges in data integration, interpretation, and visualization. Future computational developments will need to handle increasingly large and complex datasets generated by single-cell and spatial technologies, requiring scalable algorithms and efficient computational frameworks [7]. Methods for temporal integration of multi-omics data will need to mature, capturing dynamic relationships across biological processes, disease progression, and therapeutic interventions [7].

Explainability and interpretability represent crucial considerations for the next generation of multi-omics computational tools. As integration methods incorporate more complex machine learning and artificial intelligence approaches, ensuring that results remain interpretable and biologically meaningful will be essential for translational applications [2]. The development of multi-omics data visualization tools that effectively represent high-dimensional data in intuitively understandable formats will continue to be a priority, lowering barriers for researchers to extract insights from complex integrated datasets [4] [7]. These advances will collectively support the ongoing transformation of multi-omics integration from a specialized methodology to a routine approach for comprehensive biological investigation and precision medicine applications.

Complex diseases such as cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and COVID-19 are driven by multifaceted interactions across genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic layers. Traditional single-omics approaches, which analyze one molecular layer in isolation, are fundamentally inadequate for deciphering this complexity. They provide a fragmented view, failing to capture the causal relationships and emergent properties that arise from cross-layer interactions. This whitepaper delineates the technical limitations of single-omics analyses and articulates the imperative for multi-omics integration through systems biology. By synthesizing current methodologies, showcasing a detailed COVID-19 case study, and providing a practical toolkit for researchers, we underscore that only an integrated approach can unravel disease mechanisms and accelerate therapeutic discovery.

Biological systems are inherently multi-layered, where complex phenotypes emerge from dynamic interactions between an organism's genome, transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome [8]. Single-omics technologies—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, or metabolomics conducted in isolation—offer a valuable but ultimately myopic view of this intricate network. While they can identify correlations between molecular changes and disease states, they cannot elucidate underlying causal mechanisms [8]. For instance, a mutation identified in the genome may not predict its functional impact on protein activity or metabolic flux, and a change in RNA expression often correlates poorly with the abundance of its corresponding protein due to post-transcriptional regulation [8] [3].

The study of complex, multifactorial diseases like cancer, Alzheimer's, and COVID-19 exposes these shortcomings most acutely. These conditions are not orchestrated by a single genetic defect but arise from dysregulated interactions across molecular networks, influenced by genetic background, environmental factors, and epigenetic regulation [8] [9]. Relying on a single-omics approach is akin to trying to understand a symphony by listening to only one instrument; critical context and harmony are lost. As a result, single-omics studies often generate long lists of candidate biomarkers with limited clinical utility, as they lack the systems-level context to distinguish true drivers from passive correlates [8] [9]. The path forward requires a paradigm shift from a reductionist, single-layer analysis to a holistic, systems biology framework that integrates multiple omics layers to construct a more complete and predictive model of health and disease.

Deconstructing the Omics Layers: Strengths and Limitations

To appreciate the necessity of integration, one must first understand the unique yet incomplete perspective offered by each individual omics layer. The following table summarizes the core components, technologies, and inherent limitations of four major omics fields.

Table 1: Key Omics Technologies and Their Individual Limitations in Disease Research

| Omics Layer | Core Components Analyzed | Common Technologies | Key Limitations in Isolation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA sequences, structural variants, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) | Whole-genome sequencing, Exome sequencing, GWAS [8] | Cannot predict functional consequences on gene expression or protein function; most variants have no direct biological relevance [8]. |

| Transcriptomics | Protein-coding mRNAs, non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs, microRNAs, circular RNAs) | RNA-seq, single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) [8] [10] | mRNA levels often poorly correlate with protein abundance due to post-transcriptional controls; provides no data on protein activity or modification [8] [10]. |

| Proteomics | Proteins and their post-translational modifications (phosphorylation, glycosylation) | Mass spectrometry (label-free and labeled), affinity proteomics, protein chips [8] | Misses upstream regulatory events (e.g., genetic mutations, transcriptional bursts); technically challenging to detect low-abundance proteins [8]. |

| Metabolomics | Small molecule metabolites (carbohydrates, lipids, amino acids) | Mass spectrometry (MALDI, SIMS, LAESI) [8] [10] | Provides a snapshot of cellular phenotype but is several steps removed from initial genetic and transcriptional triggers [8]. |

The Multi-Omics Integration Paradigm: Methods and Workflows

Multi-omics integration synthesizes data from the layers described in Table 1 to create a unified model of biological systems. The integration workflow can be conceptualized as a multi-stage process, from experimental design to computational analysis, with the choice of method depending on the specific biological question.

Data Integration Approaches

Computational integration methods are broadly categorized based on how they handle the disparate data types.

- Correlation-based and Network-based Integration: This approach identifies statistical relationships between different molecular entities (e.g., an mRNA and its protein) and maps them into a comprehensive network. This network can then be analyzed to find hub nodes (highly connected molecules) and driver nodes (molecules that exert significant control over the network state), which are prime candidates for biomarkers or therapeutic targets [3] [9].

- Machine Learning and Deep Learning: These methods are powerful for handling the high-dimensionality and heterogeneity of multi-omics data. Deep generative models, like variational autoencoders (VAEs), are particularly adept at learning a unified representation of data from different omics layers, performing data imputation, and identifying complex, non-linear patterns that are invisible to classical statistics [11].

Workflow for a Single-Cell Multi-Omics Experiment

The advent of single-cell technologies has added a crucial dimension, allowing integration to be performed while accounting for cellular heterogeneity. A typical high-resolution workflow is outlined below.

Diagram 1: Single-Cell Multi-Omics Workflow.

- Single-Cell Isolation: Cells are separated from a tissue sample using methods like fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or microfluidic technologies (e.g., droplet-based 10X Genomics or image-based cellenONE platforms) [10] [12] [13].

- Cell Barcoding: Each individual cell is labeled with a unique molecular barcode during reverse transcription or amplification. This allows sequencing libraries from thousands of cells to be pooled and sequenced together, with the barcode used to deconvolute the data back to individual cells post-sequencing [10] [13].

- Multi-Omics Library Preparation: specialized protocols are used to capture multiple modalities from the same cell. For example:

- Sequencing & Data Integration: Pooled libraries are sequenced on high-throughput platforms. The resulting data is integrated using the computational methods described above, allowing researchers to link, for example, open chromatin regions with gene expression changes in individual cell types.

Case Study: A Systems Biology Approach to COVID-19 Therapy

The global challenge of COVID-19 exemplifies the power of a multi-omics, systems biology approach for identifying therapeutic targets for a complex disease. A 2024 study published in Scientific Reports provides a compelling model [9].

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The study followed a rigorous multi-stage protocol to move from a broad genetic association to specific drug combinations.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics and Network Analysis

| Reagent / Tool Category | Example(s) | Primary Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Gene/Database Resources | CORMINE, DisGeNET, STRING, KEGG [9] | Provides curated, context-specific biological data for network construction and pathway analysis. |

| Omic Data Analysis Tools | Expression Data (GSE163151) [9] | Provides empirical molecular profiling data (e.g., transcriptomes) for validation of computational predictions. |

| Network Controllability Algorithms | Target Controllability Algorithm [9] | Identifies a minimal set of "driver" nodes (genes/proteins) that can steer a biological network from a diseased to a healthy state. |

| Drug-Gene Interaction Databases | Drug-Gene Interaction Data [9] | Maps identified driver genes to existing pharmaceutical compounds, enabling drug repurposing strategies. |

- Data Collection and Network Construction: The researchers first aggregated 757 genes highly associated with COVID-19 from public databases (CORMINE and DisGeNET). A protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was built from these genes using the STRING database to identify highly connected hub genes (e.g., IL6, TNF) [9].

- Network Controllability Analysis: The directed network of COVID-19 signaling pathways was obtained from KEGG. Using a target controllability algorithm, the study identified a small set of driver genes capable of influencing the entire disease-associated network. IL6 was notably among the top drivers, validating its known role [9].

- Transcriptomic Validation: Analysis of gene expression data (GEO: GSE163151) confirmed that the identified hub and driver genes were differentially expressed between COVID-19 patients and controls. Furthermore, the co-expression patterns among these genes were significantly altered in the disease state, indicating a fundamental rewiring of regulatory networks [9].

- Drug-Gene Network Construction: Finally, the researchers constructed a bipartite network mapping existing drugs to the identified hub and driver genes. This systems-level analysis revealed combinations of drugs that could collectively target the core network regulators, presenting a powerful strategy for designing combination therapies and repurposing existing drugs [9].

Logical Workflow of the COVID-19 Case Study

The following diagram summarizes the logical flow of the case study, from data integration to clinical insight.

Diagram 2: Systems Biology Workflow for COVID-19.

The Scientist's Toolkit for Multi-Omics Research

Transitioning from single-omics to integrated research requires a new set of conceptual and practical tools. This toolkit encompasses experimental technologies, computational methods, and data resources.

Key Computational Methods for Data Integration

The table below categorizes and describes prominent computational approaches for multi-omics integration, which are critical for extracting biological meaning from complex datasets.

Table 3: Categories of Computational Methods for Multi-Omics Integration

| Method Category | Core Principle | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Network-Based | Constructs graphs where nodes are biomolecules and edges are interactions. Importance is inferred from network topology (e.g., centrality, controllability) [3] [9]. | Identifying key regulator and driver genes in COVID-19 PPI and signaling networks [9]. |

| Deep Generative Models | Uses models like Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) to learn a compressed, joint representation of multiple omics datasets, enabling data imputation and pattern discovery [11]. | Integrating genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics to identify novel molecular subtypes of cancer [11]. |

| Similarity-Based | Integrates datasets by finding a common latent space or by fusing similarity networks built from each omics type. | Clustering patients into integrative subtypes for precision oncology [3]. |

Navigating the Throughput vs. Accuracy Trade-Off in Single-Cell Analysis

A key practical consideration in experimental design is the choice of single-cell technology, which often involves a trade-off between the scale of data generation and the quality and specificity of the data.

- High-Throughput Technologies (e.g., 10X Genomics, BD Rhapsody): These droplet- or microwell-based systems can process tens of thousands of cells per run, making them ideal for large-scale atlas projects like the Human Cell Atlas [10] [12]. However, they have a higher risk of multiplets (droplets with more than one cell), lower sensitivity leading to gene dropout, and require large input cell numbers, which can be unsuitable for rare or delicate cell samples [12].

- High-Accuracy Technologies (e.g., cellenONE, C.SIGHT): These image-based, automated single-cell dispensers offer gentle cell handling, near-perfect single-cell accuracy, and the ability to select cells based on morphology or fluorescence. This makes them superior for studying rare cells (e.g., circulating tumor cells) or for complex, customized workflows like integrated single-cell proteomics and transcriptomics (e.g., nanoSPLITS) [12]. Their main limitation is lower throughput, processing hundreds to thousands of individually selected cells.

The evidence is clear: single-omics approaches are insufficient for unraveling the complex, interconnected mechanisms of human disease. They provide a static, fragmented view that cannot explain the dynamic, cross-layer interactions that define pathological states. The future of biomedical research lies in the systematic integration of multi-omics data within a systems biology framework. This paradigm shift, powered by advanced computational methods and high-resolution single-cell and spatial technologies, is transforming our ability to identify robust biomarkers, stratify patients based on molecular drivers, and discover effective combination therapies. For researchers and drug development professionals, embracing this integrative imperative is no longer an option but a necessity for achieving meaningful progress against complex diseases.

Multi-omics data integration represents a cornerstone of modern systems biology, providing an unprecedented opportunity to understand complex biological systems through the combined lens of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. This approach enables researchers to move beyond single-layer analyses to capture a more holistic view of the intricate interactions and dynamics within an organism [14]. The fundamental premise of systems biology is that cross-talk between multiple molecular layers cannot be properly assessed by analyzing each omics layer in isolation [15]. Instead, integrating data from different omics levels offers the potential to significantly improve our understanding of their interrelation and combined influence on health and disease [15]. However, the path to meaningful integration is fraught with substantial challenges related to data heterogeneity, high-dimensionality, and technical noise that must be systematically addressed to realize the full potential of multi-omics research.

Data Heterogeneity: The Multi-Source Integration Problem

Data heterogeneity in multi-omics studies arises from the fundamentally different nature of various molecular measurements, creating significant barriers to seamless integration.

The heterogeneous nature of multi-omics data stems from multiple factors. Each omics technology generates data with distinct statistical distributions, noise profiles, and measurement characteristics [16]. For instance, transcriptomics and proteomics are increasingly quantitative, but the applicability and precision of quantification strategies vary considerably—from absolute to relative quantification [15]. This heterogeneity is further compounded by differences in sample requirements; the preferred collection methods, storage techniques, and required biomass for genomics studies are often incompatible with metabolomics, proteomics, or transcriptomics [15].

Sample matrix incompatibility represents another critical challenge. Biological samples optimal for one omics type may be unsuitable for others. For example, urine serves as an excellent bio-fluid for metabolomics studies but contains limited proteins, RNA, and DNA, making it suboptimal for proteomics, transcriptomics, and genomics [15]. Conversely, blood, plasma, or tissues provide more versatile matrices for generating multi-omics data but require rapid processing and cryopreservation to prevent degradation of unstable molecules like RNA and metabolites [15].

Table 1: Types of Multi-Omics Data Integration Approaches

| Integration Type | Data Characteristics | Key Challenges | Common Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matched (Vertical Integration) | Multi-omics profiles from same samples | Sample compatibility, processing speed | MOFA, DIABLO |

| Unmatched (Diagonal Integration) | Data from different samples/studies | Cross-study variability, batch effects | SNF, MNN-correct |

| Temporal | Time-series multi-omics data | Temporal alignment, dynamics modeling | Dynamic Baysian networks |

| Spatial | Spatially-resolved omics data | Spatial registration, resolution matching | SpatialDE, novoSpaRc |

Experimental Design Solutions

Addressing data heterogeneity begins at the experimental design stage. A successful systems biology experiment requires careful consideration of samples, controls, external variables, biomass requirements, and replication strategies [15]. Ideally, multi-omics data should be generated from the same set of samples to enable direct comparison under identical conditions, though this is not always feasible due to limitations in sample biomass, access, or financial resources [15].

Technical considerations extend to sample processing compatibility. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, while excellent for genomic studies, are problematic for transcriptomics and proteomics because formalin does not halt RNA degradation and induces protein cross-linking [15]. Similarly, paraffin interferes with mass spectrometry performance, affecting both proteomics and metabolomics assays [15]. Recognizing and accounting for these limitations during experimental design is crucial for mitigating their impact on data integration.

High-Dimensionality: Navigating the Curse of Dimensionality

The high-dimensional nature of multi-omics data presents both computational and analytical challenges that require specialized approaches for effective navigation.

The Dimensionality Challenge

Single-cell technologies exemplify the dimensionality problem, routinely profiling tens of thousands of genes across thousands of individual cells [17]. This high dimensionality, coupled with characteristic technical noise and high dropout levels (under-sampling of mRNA molecules), complicates the identification of meaningful biological patterns [17]. The "curse of dimensionality" manifests as an accumulation of technical noise that obfuscates the true data structure, making conventional analytical approaches insufficient [18].

Dimensionality reduction has become a cornerstone of modern single-cell analysis pipelines, but conventional methods often fail to capture full cellular diversity [17]. Principal Component Analysis (PCA), for instance, projects data to a lower-dimensional linear subspace that maximizes total variance of the projected data, while Independent Component Analysis (ICA) identifies non-Gaussian combinations of features [17]. However, both approaches optimize objective functions over entire datasets, causing rare cell populations—defined by genes that may be noisy or unexpressed over much of the data—to be overlooked [17].

Advanced Computational Solutions

Novel computational strategies are emerging to address the limitations of conventional dimensionality reduction techniques. Surprisal Component Analysis (SCA) represents an information-theoretic approach that leverages the concept of surprisal (where less probable events are more informative when they occur) to assign surprisal scores to each transcript in each cell [17]. By identifying axes that capture the most surprising variation, SCA enables dimensionality reduction that better preserves information from rare and subtly defined cell types [17].

The SCA methodology involves converting transcript counts into surprisal scores by comparing a gene's expression distribution among a cell's k-nearest neighbors to its global expression pattern [17]. A transcript whose local expression deviates strongly from its global expression receives a high surprisal score, quantified through a Wilcoxon rank-sum test p-value and transformed via negative logarithm conversion [17]. The resulting surprisal matrix undergoes singular value decomposition to identify surprisal components that form the basis for projection into a lower-dimensional space [17].

Table 2: Dimensionality Reduction Methods for Multi-Omics Data

| Method | Type | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | Linear | Maximizes variance of projected data | Computational efficiency, interpretability | Sensitive to outliers, misses rare populations |

| SCA | Linear | Maximizes surprisal/information content | Captures rare cell types, preserves subtle signals | Computationally intensive for large k |

| scVI | Non-linear | Variational inference with ZINB model | Handles count nature, probabilistic framework | Complex implementation, black-box nature |

| Diffusion Maps | Non-linear | Diffusion process on k-NN graph | Captures continuous trajectories | Sensitivity to neighborhood parameters |

| PHATE | Non-linear | Potential of heat diffusion for affinity | Visualizes branching trajectories | Computational cost for large datasets |

For broader multi-omics integration, methods like Multi-Omics Factor Analysis (MOFA) provide unsupervised factorization that infers latent factors capturing principal sources of variation across data types [16]. MOFA decomposes each datatype-specific matrix into a shared factor matrix and weight matrices within a Bayesian probabilistic framework that emphasizes relevant features and factors [16]. Similarly, Multiple Co-Inertia Analysis (MCIA) extends covariance optimization to simultaneously align multiple omics features onto the same scale, generating a shared dimensional space for integration and biological interpretation [16].

Technical Noise: Overcoming Data Quality Challenges

Technical noise represents a fundamental barrier to robust multi-omics integration, requiring sophisticated statistical approaches for effective mitigation.

Technical noise in omics data arises from multiple sources throughout the experimental workflow. In single-cell sequencing, technical noise manifests as non-biological fluctuations caused by non-uniform detection rates of molecules, commonly observed as dropout events where genuine transcripts fail to be detected [18]. This noise masks true cellular expression variability and complicates the identification of subtle biological signals, potentially obscuring critical phenomena such as tumor-suppressor events in cancer or cell-type-specific transcription factor activities [18].

Batch effects further compound technical challenges by introducing non-biological variability across datasets from different experimental conditions or sequencing platforms [18]. These effects distort comparative analyses and impede the consistency of biological insights across studies, particularly problematic in multi-omics research where integration of diverse data types is essential [18]. The simultaneous reduction of both technical noise and batch effects remains challenging because conventional batch correction methods typically rely on dimensionality reduction techniques like PCA, which themselves are insufficient to overcome the curse of dimensionality [18].

Integrated Noise Reduction Frameworks

Advanced computational frameworks are emerging to address the dual challenges of technical noise and batch effects. RECODE (Resolution of the Curse of Dimensionality) represents a high-dimensional statistics-based approach that models technical noise as a general probability distribution and reduces it using eigenvalue modification theory [18]. The algorithm maps gene expression data to an essential space using noise variance-stabilizing normalization and singular value decomposition, then applies principal-component variance modification and elimination [18].

The recently enhanced iRECODE platform integrates batch correction within this essential space, minimizing decreases in accuracy and computational cost by bypassing high-dimensional calculations [18]. This integrated approach enables simultaneous reduction of technical and batch noise while preserving data dimensions, maintaining distinct cell-type identities while improving cross-batch comparability [18]. Quantitative evaluations demonstrate iRECODE's effectiveness, with relative errors in mean expression values decreasing significantly from 11.1-14.3% to just 2.4-2.5% [18].

The utility of noise reduction extends beyond transcriptomics to diverse single-cell modalities. RECODE has demonstrated effectiveness in processing single-cell epigenomics data, including scATAC-seq and single-cell Hi-C, as well as spatial transcriptomics datasets [18]. For scHi-C data, RECODE considerably mitigates data sparsity, aligning scHi-C-derived topologically associating domains with their bulk Hi-C counterparts and enabling detection of differential interactions that define cell-specific interactions [18].

Integrated Methodologies for Multi-Omics Analysis

Successfully navigating the challenges of multi-omics data requires integrated methodologies that address heterogeneity, dimensionality, and noise in a coordinated framework.

Experimental Design and Workflow Integration

A robust multi-omics workflow begins with comprehensive experimental design that anticipates integration challenges. The first step involves capturing prior knowledge and formulating hypothesis-testing questions, followed by careful consideration of sample size, power calculations, and platform selection [15]. Researchers must determine which omics platforms will provide the most value, noting that not all platforms need to be accessed to constitute a systems biology study [15].

Sample collection, processing, and storage requirements must be factored into experimental design, as these variables directly impact the types of omics analyses possible. Logistical limitations that delay freezing, sample size restrictions, and initial handling procedures can all influence biomolecule profiles, particularly for metabolomics and transcriptomics studies [15]. Establishing standardized protocols for sample processing across omics types, while challenging, is essential for generating comparable data.

Computational Integration Frameworks

Several computational frameworks have been developed specifically for multi-omics integration, each with distinct strengths and applications. Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) avoids merging raw measurements directly, instead constructing sample-similarity networks for each omics dataset where nodes represent samples and edges encode inter-sample similarities [16]. These datatype-specific matrices are fused via non-linear processes to generate a composite network capturing complementary information from all omics layers [16].

DIABLO (Data Integration Analysis for Biomarker discovery using Latent Components) takes a supervised approach, using known phenotype labels to guide integration and feature selection [16]. The algorithm identifies latent components as linear combinations of original features, searching for shared latent components across omics datasets that capture common sources of variation relevant to the phenotype of interest [16]. Feature selection is achieved using penalization techniques like Lasso to ensure only the most relevant features are retained [16].

Table 3: Multi-Omics Integration Methods and Applications

| Method | Integration Type | Statistical Approach | Best Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOFA | Unsupervised | Bayesian factorization | Exploratory analysis, latent pattern discovery |

| DIABLO | Supervised | Multiblock sPLS-DA | Biomarker discovery, classification tasks |

| SNF | Similarity-based | Network fusion | Subtype identification, cross-platform integration |

| MCIA | Correlation-based | Covariance optimization | Coordinated variation analysis, cross-dataset comparison |

| iRECODE | Noise reduction | High-dimensional statistics | Data quality enhancement, pre-processing |

For metabolic-focused studies, Genome-scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) serve as computational scaffolds for integrating multi-omics data to identify signatures of dysregulated metabolism [19]. These models enable the prediction of metabolic fluxes through linear programming approaches like flux balance analysis (FBA), and can be tailored to specific tissues or disease states [19]. Personalized GEMs have shown promise in guiding treatments for individual tumors, identifying dysregulated metabolites that can be targeted with anti-metabolites functioning as competitive inhibitors [19].

Successful navigation of multi-omics challenges requires both wet-lab and computational resources designed to address specific integration hurdles.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | FAA-approved transport solutions | Cryopreserved sample transport | Maintains biomolecule integrity during transit |

| Sequencing Technologies | 10x Genomics, Smart-seq, Drop-seq | Single-cell transcriptomics | Protocol compatibility with downstream omics |

| Proteomics Platforms | SWATH-MS, UPLC-MS | Quantitative proteomics | Quantitative precision, coverage depth |

| Metabolomics Platforms | UPLC-MS, GC-MS | Metabolite profiling | Sample stability, extraction efficiency |

| Computational Tools | RECODE/iRECODE, SCA, MOFA, DIABLO | Noise reduction, dimensionality reduction, integration | Data type compatibility, computational requirements |

| Bioinformatics Platforms | Omics Playground, KEGG, Reactome | Integrated analysis, pathway mapping | User accessibility, visualization capabilities |

Navigating data heterogeneity, high-dimensionality, and technical noise represents a formidable challenge in multi-omics research, but continued methodological advancements provide powerful solutions. By addressing these challenges through integrated experimental design, sophisticated computational frameworks, and specialized analytical tools, researchers can unlock the full potential of multi-omics data integration. The convergence of information-theoretic dimensionality reduction approaches like SCA, comprehensive noise reduction platforms like iRECODE, and flexible integration methods like MOFA and DIABLO provides an increasingly robust toolkit for extracting meaningful biological insights from complex multi-omics datasets. As these methodologies continue to evolve and mature, they promise to advance our understanding of complex biological systems and accelerate the development of precision medicine approaches grounded in comprehensive molecular profiling.

The advent of high-throughput technologies has generated ever-growing volumes of biological data across multiple molecular layers, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics [20]. While single-omics studies have provided valuable insights, they offer an overly simplistic view of complex biological systems where different layers interact dynamically [20]. Multi-omics integration emerges as a necessary approach to capture the entire complexity of biological systems and draw a more complete picture of phenotypic outcomes [20] [15]. The convergence of medical imaging and multi-omics data has further accelerated the development of multimodal artificial intelligence (AI) approaches that leverage complementary strengths of each modality for enhanced disease characterization [21].

Within systems biology, integration strategies for these heterogeneous datasets are broadly classified into early, intermediate, and late fusion paradigms, each with distinct methodological principles and applications [20] [22] [21]. These computational frameworks address the significant challenges posed by high-dimensionality, heterogeneity, and noise inherent in multi-omics datasets [20] [3]. This technical guide examines these core integration paradigms, their computational architectures, and their implementation within systems biology research for drug development and precision medicine.

Core Integration Paradigms

Conceptual Frameworks and Definitions

Multi-omics integration strategies can be categorized into distinct paradigms based on the stage at which data fusion occurs in the analytical pipeline. The nomenclature for these integration strategies varies across literature, with some sources using "fusion" terminology particularly in medical imaging contexts [21], while others refer more broadly to "integration" approaches [20]. This guide adopts a unified classification system encompassing three primary paradigms.

Early Integration (also called early fusion or concatenation-based integration) combines all omics datasets into a single matrix before analysis [20]. All features from different omics platforms are merged at the input level, creating a unified feature space that is then processed using machine learning models [20] [21].

Intermediate Integration (including mixed and intermediate fusion) employs joint dimensionality reduction or transformation techniques to find a common representation of the data [20] [22]. Unlike early integration, intermediate approaches maintain some separation between omics layers during the transformation process, either by independently transforming each omics block before combination or simultaneously transforming original datasets into common and omics-specific representations [20].

Late Integration (also called late fusion or model-based integration) analyzes each omics dataset separately and combines their final predictions or representations at the decision level [20] [21]. This modular approach allows specialized processing for each data type before aggregating outcomes.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Multi-Omics Integration Paradigms

| Integration Paradigm | Data Fusion Stage | Key Characteristics | Representative Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration | Input/feature level | Concatenates raw or preprocessed features; leverages cross-omics correlations; prone to curse of dimensionality | PCA on concatenated matrices; Random Forests; Support Vector Machines |

| Intermediate Integration | Transformation/learning level | Joint dimensionality reduction; preserves omics-specific patterns while learning shared representations; balances specificity and integration | MOFA+; iCluster; Pattern Fusion Analysis; Deep learning autoencoders |

| Late Integration | Output/decision level | Separate modeling for each omics; combines predictions; robust to missing data; preserves modality-specific processing | Weighted voting; Stacked generalization; Ensemble methods; Majority voting |

Expanded Classification Frameworks

Some systematic reviews further refine these categories to encompass five distinct integration strategies, expanding the three primary paradigms to address specific analytical needs [20]:

- Early Integration: Direct concatenation of omics datasets into a single matrix

- Mixed Integration: Independent transformation of each omics dataset before combination

- Intermediate Integration: Simultaneous transformation into common and omics-specific representations

- Late Integration: Separate analysis with combination of final predictions

- Hierarchical Integration: Integration based on known regulatory relationships between omics layers

Hierarchical integration represents a specialized approach that incorporates prior biological knowledge about regulatory relationships between molecular layers, such as those described by the central dogma of molecular biology [20]. This strategy explicitly models the directional flow of biological information, potentially offering more biologically interpretable models.

Technical Implementation and Methodologies

Early Integration: Concatenation-Based Approaches

Early integration fundamentally involves merging diverse omics measurements into a unified feature space at the outset of analysis. The technical workflow typically involves sample-wise concatenation of multiple omics datasets, each pre-processed according to its specific requirements, into a composite matrix that serves as input for machine learning models [20].

Diagram 1: Early integration workflow

Experimental Protocol for Early Integration:

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize and scale each omics dataset independently according to platform-specific requirements [20]

- Feature Concatenation: Merge preprocessed datasets sample-wise into a unified matrix where rows represent samples and columns represent all features across omics layers

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply principal component analysis (PCA) or other reduction techniques to address high dimensionality [20]

- Model Training: Implement machine learning algorithms (e.g., Random Forests, SVM) on the integrated dataset

- Validation: Perform cross-validation and external validation to assess model performance and generalizability

The primary challenge in early integration is the curse of dimensionality, where the number of features (p) vastly exceeds the number of samples (n), creating computational challenges and increasing overfitting risk [20]. This approach also assumes that all omics data are available for the same set of samples and properly aligned [21].

Intermediate Integration: Joint Learning Approaches

Intermediate integration strategies transform omics datasets into a shared latent space where biological patterns can be identified across modalities. These methods aim to balance the preservation of omics-specific signals while capturing cross-omics relationships.

Diagram 2: Intermediate integration workflow

Methodological Variations in Intermediate Integration:

- Mixed Integration: First independently transforms or maps each omics block into a new representation before combining them for downstream analysis [20]

- Simultaneous Integration: Transforms original datasets jointly into common and omics-specific representations [20]

- Deep Learning Approaches: Use autoencoders or other neural network architectures to learn shared representations across modalities [20] [21]

Experimental Protocol for Intermediate Integration Using Matrix Factorization:

- Data Preparation: Standardize each omics dataset to have comparable ranges and distributions

- Model Selection: Choose appropriate integration algorithm (e.g., MOFA+, iCluster) based on data characteristics and research question

- Dimensionality Setting: Determine optimal number of latent factors through cross-validation or heuristic approaches

- Model Training: Apply joint matrix factorization to derive shared components across omics types

- Interpretation: Analyze factor loadings to identify driving features from each omics platform

- Validation: Assess biological relevance of identified patterns using pathway analysis or functional annotations

Intermediate integration effectively handles heterogeneity between different omics data types and can manage scale differences between platforms [20]. These methods are particularly valuable for identifying coherent biological patterns across molecular layers and for disease subtyping applications [20] [3].

Late Integration: Decision-Level Fusion

Late integration adopts a modular approach where each omics dataset is processed independently, with fusion occurring only at the decision or prediction level. This strategy aligns with ensemble methods in machine learning and is particularly valuable when omics data types have substantially different characteristics or when missing data is a concern [21].

Diagram 3: Late integration workflow

Fusion Methodologies in Late Integration:

- Weighted Voting: Combine predictions from omics-specific models with weights based on model performance or data quality [20]

- Stacked Generalization: Use predictions from base models as features for a meta-learner that makes final decisions [20]

- Majority Voting: Simple aggregation where the most frequent prediction across models is selected

- Confidence-based Fusion: Combine predictions weighted by confidence scores from each model

Late integration provides flexibility in handling different data types and is robust to missing modalities, as individual models can be trained and validated independently [21]. The modular nature of this approach also enhances interpretability, as the contribution of each omics type to the final decision can be traced and quantified [20] [21].

Experimental Design Considerations for Multi-Omics Studies

Foundational Design Principles

Proper experimental design is critical for successful multi-omics integration, particularly in systems biology approaches to complex diseases [15] [23]. The RECOVER initiative for studying Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) exemplifies comprehensive study design incorporating longitudinal multi-omics profiling [23].

Key Design Elements for Multi-Omics Studies:

- Sample Collection Strategy: Ensure sufficient biomass for all planned omics assays; implement standardized collection protocols across sites [15] [23]

- Temporal Design: Incorporate longitudinal sampling where appropriate to capture dynamic biological processes [23]

- Metadata Collection: Document comprehensive clinical, demographic, and technical metadata to enable proper confounding adjustment [15]

- Batch Effect Control: Randomize processing orders and implement technical controls to identify and correct for batch effects

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Multi-Omics Studies

| Category | Specific Technologies/Reagents | Primary Function in Multi-Omics Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection & Stabilization | PAXgene RNA tubes; cell preparation tubes; Oragene DNA collection kits | Preserve molecular integrity during collection, storage, and transport [23] |

| Genomics Platforms | Next-generation sequencing; SNP-chip profiling | Interrogate genetic variation, mutations, and structural variants [15] |

| Transcriptomics Platforms | RNA-seq; single-cell RNA sequencing | Profile gene expression patterns and alternative splicing [15] |

| Proteomics Platforms | SWATH-MS; affinity-based arrays; UPLC-MS | Quantify protein abundance and post-translational modifications [15] |

| Metabolomics Platforms | UPLC-MS; GC-MS | Measure small molecule metabolites and metabolic pathway activity [15] |

| Epigenomics Platforms | Bisulfite sequencing; ChIP-seq | Characterize DNA methylation and histone modifications [21] |

Computational Infrastructure Requirements

The computational demands of multi-omics integration necessitate robust infrastructure and appropriate tool selection:

- High-Performance Computing: Multi-core processing capabilities for intensive matrix operations and algorithm training

- Memory Resources: Sufficient RAM to handle large matrices, particularly for early integration approaches

- Storage Solutions: Scalable storage for raw data, intermediate files, and processed results

- Software Ecosystem: Access to statistical computing environments (R/Python) and specialized multi-omics packages

Applications in Precision Medicine and Drug Development

Translational Applications in Oncology

Multi-omics integration has demonstrated particular value in oncology, where the complexity and heterogeneity of cancer benefit from layered molecular characterization [21] [3]. Integrated models combining imaging and omics data have shown improved performance in cancer identification, subtype classification, and prognosis prediction compared to unimodal approaches [21].

Key Applications in Cancer Research:

- Tumor Subtyping: Identification of molecular subtypes with distinct clinical outcomes and therapeutic vulnerabilities [20] [3]

- Biomarker Discovery: Discovery of multi-modal biomarker signatures with improved sensitivity and specificity [20] [3]

- Drug Response Prediction: Modeling therapeutic response based on integrated molecular profiles [21] [3]

- Resistance Mechanism Elucidation: Uncovering complementary pathways contributing to treatment resistance [3]

Emerging Frontiers: Multi-Omics in Chronic Disease

The systems biology approach to complex chronic conditions is exemplified by initiatives like the RECOVER study of PASC (Long COVID), which implements integrated, longitudinal multi-omics profiling to decipher molecular subtypes and mechanisms [23]. This paradigm demonstrates how deep clinical phenotyping combined with multi-omics data can accelerate understanding of poorly characterized conditions.

Implementation Framework for Chronic Disease Studies:

- Centralized Laboratory Processing: Minimize technical variability through standardized processing across omics platforms [23]

- Simultaneous Multi-Omics Profiling: Generate complementary omics data from the same samples to enable vertical integration [23]

- Clinical Correlation: Integrate deep clinical data with molecular measurements to establish clinical relevance [23]

- Data Accessibility: Ensure availability of integrated datasets for secondary analysis by the research community [23]

Comparative Analysis and Strategic Selection

Performance and Applicability Considerations

The selection of an appropriate integration strategy depends on multiple factors, including data characteristics, analytical goals, and computational resources.

Table 3: Strategic Selection Guide for Integration Paradigms

| Criterion | Early Integration | Intermediate Integration | Late Integration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Alignment | Requires complete, aligned data across omics | Handles some misalignment through transformation | Tolerant of misalignment and missing data |

| Dimensionality | Challenged by high dimensionality | Reduces dimensionality through latent factors | Manages dimensionality per modality |

| Model Interpretability | Lower due to feature entanglement | Moderate, depending on method | Higher, with clear modality contributions |

| Missing Data Handling | Poor, requires complete cases | Moderate, some methods handle missingness | Good, can work with available modalities |

| Biological Prior Knowledge | Difficult to incorporate | Can incorporate through model constraints | Easy to incorporate in individual models |

| Computational Complexity | Lower for simple models | Generally higher | Moderate, parallelizable |

Hybrid Integration Strategies

Recent advances have explored hybrid fusion strategies that combine elements from multiple paradigms to leverage their complementary strengths [21]. These approaches might, for example, integrate early fusion representations with decision-level fusion outputs to enhance predictive accuracy and biological relevance [21]. Hybrid architectures, including those incorporating attention mechanisms and graph neural networks, have shown promise in modeling complex inter-modal relationships in cancer prognosis and treatment response prediction [21].

The integration of multi-omics data represents a fundamental methodology in systems biology, enabling a more comprehensive understanding of biological systems and disease mechanisms than achievable through single-omics approaches. The three primary integration paradigms—early, intermediate, and late fusion—offer distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different research contexts and data environments.

Early integration provides a straightforward approach for aligned datasets but struggles with high dimensionality. Intermediate integration offers a balanced solution through joint dimensionality reduction, while late integration delivers robustness and interpretability at the cost of potentially missing cross-omics interactions. The emerging trend toward hybrid approaches reflects the growing sophistication of multi-omics integration methodologies.

As multi-omics technologies continue to evolve and datasets expand, the development of more sophisticated, scalable, and interpretable integration strategies will be essential to fully realize the promise of precision medicine and advance drug development pipelines. Future directions will likely include enhanced incorporation of biological knowledge, improved handling of temporal dynamics, and more effective strategies for clinical translation.

A Practical Guide to Multi-Omics Integration Methods: From Classical Statistics to Deep Generative Models

In the field of systems biology, the integration of multi-omics data—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics—is crucial for constructing comprehensive models of complex biological systems [24]. The concurrent analysis of these data types presents significant statistical challenges, including high-dimensionality, heterogeneous data structures, and technical noise [25]. Dimensionality reduction methods are essential tools for addressing these challenges by extracting latent factors that represent underlying biological processes [26].

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of four fundamental dimensionality reduction techniques for multi-omics integration: Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA), Partial Least Squares (PLS), Joint and Individual Variation Explained (JIVE), and Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF). We compare their mathematical foundations, applications in multi-omics research, and provide detailed experimental protocols for implementation.

Methodological Foundations

Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA)

Canonical Correlation Analysis is a correlation-based integrative method designed to extract latent features shared between multiple assays by identifying linear combinations of features—called canonical variables (CVs)—within each assay that achieve maximal across-assay correlation [24]. For two omics datasets X and Y, CCA finds weight vectors wX and wY such that the correlation between XwX and YwY is maximized [27].

Sparse multiple CCA (SMCCA) extends this approach to more than two assays by optimizing:

maximize∑i

where wi are sparse weight vectors promoting feature selection, particularly valuable for high-dimensional omics data [24]. A recent innovation incorporates the Gram-Schmidt (GS) algorithm with SMCCA to improve orthogonality among canonical variables, addressing the issue of highly correlated CVs that plagues traditional applications to high-dimensional omics data [24] [27].

Partial Least Squares (PLS)

Partial Least Squares regression is a valuable tool for elucidating intricate relationships between external environmental exposures and internal biological responses linked to health outcomes [28]. Unlike CCA, which maximizes correlation between latent components, PLS maximizes covariance between components and a response variable.

The PLS objective function finds weight vectors wX and wY that maximize:

cov(XwX,YwY)

This makes PLS particularly effective for predictive modeling in contexts with high multicollinearity, such as exposomics research analyzing complex mixtures of environmental pollutants [28]. Recent extensions like PLASMA (Partial LeAst Squares for Multiomics Analysis) employ a two-layer approach to predict time-to-event outcomes from multi-omics data, even when samples have missing omics data [29].

Joint and Individual Variation Explained (JIVE)

Joint and Individual Variation Explained provides a general decomposition of variation for integrated analysis of multiple datasets [30]. JIVE decomposes multi-omics data into three distinct components: joint variation across data types, structured variation individual to each data type, and residual noise.

Formally, for k data matrices X1, X2, ..., Xk, JIVE models:

Xi=Ji+Ai+εifor i=1,…,k

where J represents the joint structure matrix, Ai represents individual structure for dataset i, and εi represents residual noise [30]. The model imposes rank constraints rank(J) = r and rank(Ai) = ri, with orthogonality between joint and individual structures.

Supervised JIVE (sJIVE) extends this framework by simultaneously identifying joint and individual components while building a linear prediction model for an outcome, allowing components to be influenced by their association with the outcome variable [31].

Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF)

Non-negative Matrix Factorization is a parts-based decomposition that approximates a non-negative data matrix V as the product of two non-negative matrices: V ≈ WH [32]. The W matrix contains basis components (e.g., gene programs), while H contains coefficients (e.g., program usage per sample).