Implementing Differential Evolution for ODE Parameter Estimation in Biomedical Research

Estimating parameters for dynamic models described by Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) is a critical yet challenging task in biomedical research, particularly in drug development and systems biology.

Implementing Differential Evolution for ODE Parameter Estimation in Biomedical Research

Abstract

Estimating parameters for dynamic models described by Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) is a critical yet challenging task in biomedical research, particularly in drug development and systems biology. These problems are often non-convex, leading local optimization methods to converge to suboptimal solutions. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on implementing the Differential Evolution (DE) algorithm, a powerful global optimization metaheuristic, for robust ODE parameter estimation. We cover foundational concepts, present a step-by-step methodological workflow, address common pitfalls with advanced troubleshooting strategies, and provide a framework for rigorous validation and performance comparison against other solvers, empowering professionals to enhance the reliability of their computational models.

The Challenge of ODE Parameter Estimation and Why Differential Evolution is a Powerful Solution

Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) is an essential, quantitative framework that uses mathematical models to support decision-making across the drug development lifecycle, from early discovery to post-market surveillance [1]. A critical component of this framework involves building dynamic models of biological systems, often described by systems of differential equations, to understand disease progression, drug mechanisms, and patient responses. The utility of these models hinges on the accurate estimation of their parameters from experimental data, a process that transforms a mechanistic structure into a predictive, patient-specific tool [2] [3].

Parameter estimation for dynamic systems in drug development is the process of inferring the unknown, patient-specific constants within a mathematical model by fitting the model's output to observed clinical or preclinical data. This enables the design of optimized, individualized dosage regimens, particularly when patient-specific data are not initially available [3]. For pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) models, these parameters can include clearances, distribution volumes, and rate constants, which are crucial for predicting drug concentration-time profiles and their subsequent effects [3].

Foundational Concepts and Methods

Parameter estimation, at its core, is a search problem within a defined parameter space, aiming to find the values that minimize a specific measure of discrepancy between the model's prediction and the empirical data [2]. The general problem can be formally defined for a system whose state, y, evolves according to an equation of motion, f, which depends on parameters, p [2]:

$$ \frac{\rm d}{{\rm d}t}{y}{(t)}=f({y}{(t)},t,p),\quad {y}{(t = 0)}={y}{0}. $$

The goal is to find parameters p and possibly initial conditions y₀ that minimize a real-valued loss function, L, which depends on the state of the system at the times when experimental observations were made [2].

Classification of Estimation Methods

Several families of algorithms exist for tackling parameter estimation problems, each with distinct strengths, weaknesses, and ideal application domains, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Parameter Estimation Method Families in Drug Development

| Method Family | Core Principle | Primary Applications in Drug Development | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Least-Squares Methods [2] [4] | Minimizes the sum of squared differences between model predictions and observed data. | Fitting PK/PD models to concentration-time data; model calibration. | Simpler to compute than likelihood-based methods; general applicability. | Sensitive to noise and model misspecification; can yield biased results with non-normal errors [2]. |

| Likelihood-Based Methods [2] | Maximizes the likelihood function, which measures how well the model explains the observed data. | Population PK/PD analysis; handling known data uncertainties. | Allows for uncertainty quantification; incorporates known error structures. | Requires substantial data; performance diminishes with highly dynamic or chaotic systems [2]. |

| Shooting Approaches [2] | Reduces a boundary value problem to a series of initial value problems. | Classic method for solving two-point boundary value problems. | Direct and intuitive approach. | Can be numerically unstable for stiff systems or over long time horizons. |

| Global Optimization (e.g., Genetic Algorithms, Particle Swarm Optimization) [5] [4] | Uses population-based stochastic search to explore the parameter space broadly. | Initial global exploration of complex parameter spaces; models with multiple local minima. | Less likely to be trapped in local minima; good for non-convex problems. | Computationally intensive; scales poorly with parameter dimension; poor convergence near minima [5]. |

| Gradient-Based & Adjoint Methods [2] [5] | Uses gradient information (computed via automatic differentiation or adjoint sensitivity analysis) to guide local search. | Refining parameter estimates after a global search; large-scale systems with many parameters. | Highly efficient near local minima; provides exact gradients for the discretized system [5]. | Requires differentiable models and code; framework expertise can be a barrier [5]. |

The Two-Stage and Nonlinear Mixed-Effects Approaches

In population pharmacokinetics, two main methodologies are employed to account for inter-individual variability:

- The Two-Stage Method: In the first stage, a full PK analysis is performed on each individual in the study population, requiring a relatively large number of samples per patient. In the second stage, the individual parameter estimates are combined to compute population averages and standard deviations. Relationships between parameters and patient characteristics (e.g., creatinine clearance) are established via regression or categorization [3].

- Nonlinear Mixed-Effects Models (NONMEM): This approach fits all individual data simultaneously to estimate both population-level (fixed) effects and inter-individual (random) variability. It is particularly powerful for analyzing sparse, unbalanced data collected in clinical settings, as it does not require rich data from every subject [3].

Practical Protocols for Parameter Estimation

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step workflow for estimating parameters of dynamic models, incorporating modern computational approaches.

A Generalized Parameter Estimation Workflow

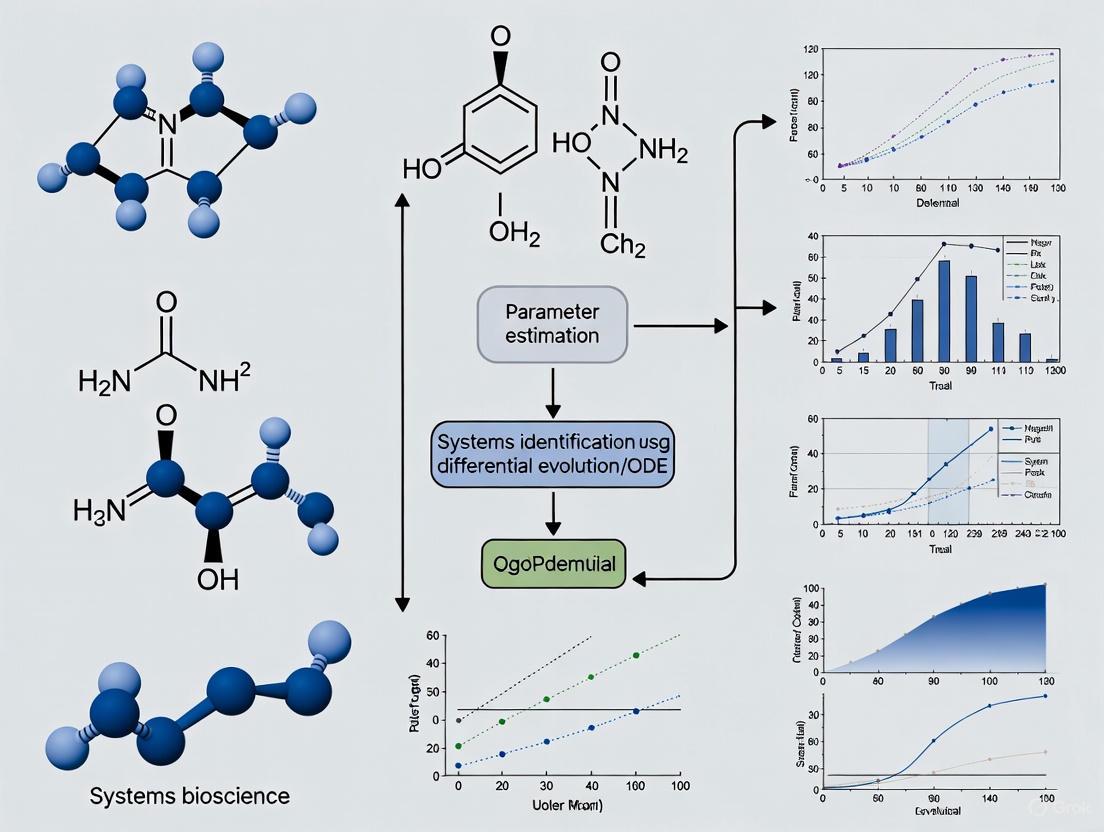

The following diagram illustrates the core logical workflow for a robust parameter estimation process.

Workflow: Parameter Estimation Process

Step-by-Step Protocol

Protocol 1: Implementing a Two-Stage Hybrid Estimation Strategy

This protocol combines global and local optimization methods to robustly fit complex models, mitigating the risk of converging to poor local minima [5] [4].

I. Problem Definition and Data Preparation

- Mathematical Model Formulation: Define the system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) representing the biological process (e.g., PK/PD system). Specify all state variables, their initial conditions, and the unknown parameters to be estimated.

- Data Collation: Gather experimental data, which may be sparse or rich, and align it with the corresponding time points and state variables in the model. Account for potential errors, such as in patient-reported dosing times, which can impact parameter accuracy [6].

- Loss Function Definition: Formulate a loss function (e.g., sum of squared errors, negative log-likelihood) that quantifies the discrepancy between model simulations and observed data.

II. Code Implementation and Validation (The "Scientist's Toolkit") Leveraging an agentic AI workflow can significantly streamline this step by automating code generation, validation, and conversion to efficient, differentiable code [5].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Modeling

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

ODE Integrator (e.g., in scipy.integrate.solve_ivp) |

Numerically solves the system of differential equations for a given parameter set. | Essential for simulating model output. Stiff solvers may be required for certain PK/PBPK models. |

| Global Optimizer (e.g., Particle Swarm Optimization) | Explores the parameter space broadly to find promising regions, avoiding local minima. | Used in the first stage of the hybrid protocol [5]. |

| Gradient-Based Optimizer (e.g., L-BFGS-B, Levenberg-Marquardt) | Refines parameter estimates using gradient information for fast local convergence. | Used in the second stage. Gradients can be obtained via automatic differentiation or adjoint methods [2] [5]. |

| Automatic Differentiation (AD) Framework (e.g., JAX, PyTorch) | Automatically and accurately computes derivatives of the loss function with respect to parameters. | Enables efficient gradient-based optimization; more precise than finite-differencing [5]. |

| Differentiable ODE Solver | An ODE solver integrated with an AD framework, allowing gradients to be backpropagated through the numerical integration. | Key for enabling gradient-based estimation for ODE models without manual derivation [5]. |

III. Two-Stage Optimization Execution

- Global Exploration Stage:

- Configure a global algorithm such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) or a Genetic Algorithm.

- Define parameter bounds based on physiological or pharmacological constraints.

- Run the optimizer to minimize the loss function, identifying one or more promising regions in the parameter space. The result of this stage serves as the initial guess for the next stage [5].

- Local Refinement Stage:

- Using the best candidate(s) from the global search, initiate a gradient-based optimizer (e.g., quasi-Newton method like L-BFGS-B).

- The optimizer will use gradient information (computed via automatic differentiation or adjoint methods) to efficiently find a local minimum of the loss function [2] [5] [4].

IV. Model Validation and Analysis

- Perform a residual analysis to check for systematic biases in the fit, which might indicate model misspecification [7].

- Conduct visual predictive checks by simulating the fitted model multiple times to see if the observed data falls within the prediction intervals of the simulations.

- Evaluate the identifiability of parameters—whether the available data is sufficient to uniquely determine their values.

- To ensure credibility, repeat the estimation process using different algorithms and initial values, as results can be sensitive to these choices [4].

Application in Drug Development Workflow

Parameter estimation is not a standalone activity but is deeply integrated into the broader drug development pipeline. The following diagram maps the application of key parameter estimation tasks onto the five main stages of drug development.

Workflow: Estimation in Drug Development

The "fit-for-purpose" principle is paramount when applying parameter estimation in this context. The chosen model and estimation technique must be aligned with the Question of Interest (QOI) and Context of Use (COU) at each stage [1]. For example, a simple linear regression between drug clearance and creatinine clearance may be sufficient for clinical dosing nomograms [3], whereas the development of a complex PBPK model for drug-drug interaction risk assessment may require more sophisticated algorithms like the Cluster Gauss-Newton method [4].

Parameter estimation is a critical enabling technology for modern, model-informed drug development. Mastering a diverse set of estimation methods—from traditional least-squares and population approaches to advanced adjoint and hybrid global-local strategies—empowers researchers to build more predictive and reliable dynamic models. The rigorous application of these techniques, guided by a "fit-for-purpose" philosophy and robust validation protocols, enhances the efficiency of the drug development pipeline. It ultimately contributes to the delivery of safer, more effective, and better-characterized therapies to patients. Future advancements will likely see increased integration of AI and machine learning workflows to further automate and enhance the robustness of the parameter estimation process [5] [1].

The Pitfalls of Local Optima and Nonconvexity in ODE Models

Parameter estimation in dynamic systems described by Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) is a cornerstone of quantitative modeling in systems biology, chemical kinetics, and drug development [8] [9]. The core problem involves identifying a set of model parameters that minimize the discrepancy between experimental data and model predictions. Mathematically, this is formulated as a dynamic optimization problem, often solved by minimizing the sum of squared errors [8].

The primary challenge, which forms the central thesis of this research, is the inherent nonconvexity of the associated optimization landscape. This nonconvexity arises from the nonlinear coupling between states and parameters in the ODEs, leading to an objective function with multiple local minima (local optima) and potentially flat regions [8] [9]. Consequently, traditional local optimization methods (e.g., nonlinear least squares, gradient-based methods) are highly susceptible to converging to suboptimal local solutions, misleading the modeler about the true system dynamics and parameter values [8] [10]. This pitfall complicates model validation, prediction, and, critically, decision-making in applications like drug dose optimization.

Our broader research thesis advocates for the implementation of Differential Evolution (DE) and other global optimization strategies as a robust solution to this challenge. While deterministic global optimization methods can guarantee global optimality, they are currently computationally prohibitive for problems with more than approximately five state and five decision variables [8] [9]. Stochastic global optimizers like DE do not offer guarantees but have demonstrated efficacy in handling realistic-sized problems [11] [12]. This application note details the protocols and considerations for employing DE to navigate the pitfalls of nonconvexity in ODE parameter estimation.

Comparative Analysis of Optimization Approaches

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of different optimization paradigms relevant to ODE parameter estimation, based on current literature.

Table 1: Comparison of Optimization Methods for Nonconvex ODE Parameter Estimation

| Method Category | Specific Examples | Convergence Guarantee | Typical Problem Scale Handled | Primary Pitfall Related to Nonconvexity | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Optimization | Nonlinear Least Squares (NLS), Gradient Descent [11] [10] | Local optimality only | Medium to Large | High risk of converging to spurious local minima [8] [10]. | Low to Medium |

| Stochastic Global Optimization | Differential Evolution (DE), Particle Swarm [11] [12] | None (heuristic) | Medium to Large | May miss global optimum; result uncertainty [8]. | High (function evaluations) |

| Deterministic Global Optimization | Spatial Branch-and-Bound [8] [13] | Global optimality | Small (~5 states/params) [8] [9] | Limited scalability to practical problem sizes. | Very High |

| Hybrid/Advanced Methods | Profiled Estimation [11], Two-Stage DE (TDE) [12], Consensus-Based [14] | Varies (often heuristic) | Medium | Design complexity; parameter tuning. | Medium to High |

| Machine Learning-Guided | Deep Active Optimization (e.g., DANTE) [15] | None (heuristic) | Very Large (up to 2000 dim) [15] | Requires careful surrogate model training and exploration strategy. | High (initial data + training) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Direct Transcription for ODE Parameter Estimation

This protocol formulates the parameter estimation problem for solution by general-purpose optimization solvers, including DE frameworks [8] [9].

- Model Definition: Define the ODE system:

dx/dt = f(t, x(t), p), with statesx, parametersp, and observationsy(t) = g(x(t), p). - Data Preparation: Compile experimental data points

(τ_i, ŷ_i)fori=1...n. - Discretization: Apply a direct transcription method (e.g., orthogonal collocation) over the time horizon

[t0, tf]. This transforms the continuous ODE system into a set of algebraic constraints at finite time points. - NLP Formulation: Construct the Nonlinear Programming (NLP) problem:

- Objective: Minimize

Σ_i ||y(τ_i) - ŷ_i||^2. - Constraints: The discretized ODE system equations, parameter bounds

(p_low, p_high).

- Objective: Minimize

- Solver Interface: Pass the NLP to a global solver (e.g., a DE algorithm). The solver treats the discretized problem as a black-box, nonconvex optimization.

Protocol 3.2: Two-Stage Differential Evolution (TDE) for Parameter Estimation

Adapted from the successful application in PEMFC modeling [12], this protocol outlines a enhanced DE variant.

- Initialization: Define DE parameters: population size

NP, mutation factorF, crossover rateCR. For TDE, a historical archive is also initialized. - Stage 1 - Exploration with Historical Memory:

- For each target vector

X_i, generate a mutant vectorV_iusing a mutation strategy that incorporates vectors from the current population and a historical archive of previously promising solutions. This promotes diversity. - Perform binomial crossover between

X_iandV_ito create a trial vectorU_i.

- For each target vector

- Stage 2 - Exploitation with Inferior-Guided Search:

- If the trial vector

U_idoes not outperformX_i, a second mutation strategy is activated. This strategy uses "inferior" solutions in the population to guide the search, enhancing local exploitation and convergence speed.

- If the trial vector

- Selection: Greedily select the better vector between

X_iandU_ifor the next generation. - Termination: Repeat steps 2-4 until a maximum number of generations or a convergence threshold is met. The best solution found is reported as the parameter estimate.

Protocol 3.3: Profiled Estimation Procedure (PEP)

This protocol, based on functional data analysis, offers an alternative that avoids repeated numerical integration [11].

- B-spline Representation: Represent each state variable

x(t)as a linear combination of B-spline basis functions:x(t) ≈ Σ c_k * Φ_k(t). - Collocation Condition: Instead of solving the ODE directly, impose the condition that the derivative of the spline approximation equals the model right-hand side at a set of collocation points:

d(Σ c_k * Φ_k(t_j))/dt = f(t_j, Σ c_k * Φ_k(t_j), p). - Three-Level Optimization:

- Inner Level: For fixed parameters

pand smoothing parameterλ, optimize the spline coefficientscto fit the data and satisfy the collocation condition (a penalized least-squares problem). - Middle Level: Optimize the parameters

pby profiling, using the inner-level optimal spline coefficientsc*(p). - Outer Level: Tune the smoothing parameter

λ(e.g., via cross-validation).

- Inner Level: For fixed parameters

- Solution: The optimized

pand the corresponding spline profiles provide the parameter estimates and model trajectories.

Visualization of Methodologies and Workflows

Diagram 1: ODE Parameter Estimation Strategy Landscape

Diagram 2: Two-Stage Differential Evolution (TDE) Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for DE-based ODE Parameter Estimation Research

| Tool Category | Specific Item/Software | Function/Purpose | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modeling & Simulation | MATLAB/Simulink, Python (SciPy, PyDSTool), R (deSolve) | Provides environments for defining ODE models, simulating dynamics, and integrating with optimization routines. | Choose based on community support, available ODE solvers (stiff/non-stiff), and ease of linking to optimizers. |

| Optimization Solvers | DE Variants: (TDE [12], jDE, SHADE); Local: lsqnonlin (MATLAB), optimize.least_squares (Python); Global: BARON, SCIP |

Core engines for navigating the parameter space. DE variants are primary for global search of nonconvex problems. | Tune DE parameters (NP, F, CR). For local solvers, use multi-start from DE results for refinement. |

| Problem Formulation | CasADi, Pyomo, GAMS | Enable algebraic modeling of the discretized NLP, facilitating automatic differentiation and efficient solver interface. | Crucial for implementing direct transcription methods and connecting to high-performance solvers. |

| Data Assimilation | Profiled Estimation Code [11], Functional Data Analysis (FDA) packages (e.g., fda in R) |

Implements the PEP protocol, which can be more robust than standard optimization for some problem classes. | Useful when dealing with noisy data or when explicit ODE integration is costly. |

| Performance Analysis | RMSE, MAE, AIC/BIC, Parameter Identifiability Analysis (e.g., profile likelihood) | Metrics to assess goodness-of-fit, model comparison, and quantify confidence/identifiability of estimated parameters. | Essential for diagnosing practical non-identifiability, a common issue intertwined with nonconvexity. |

Differential Evolution (DE) is a prominent evolutionary algorithm for global optimization, first introduced by Storn and Price in 1995. DE has gained widespread adoption due to its simple structure, strong robustness, and exceptional performance in navigating complex optimization landscapes across various engineering domains [16] [17]. This article explores DE's fundamental mechanics and its specific application to parameter estimation in ordinary differential equation (ODE) models, a critical task in drug development and pharmacological research.

The algorithm operates on a population of candidate solutions, iteratively improving them through cycles of mutation, crossover, and selection operations [16]. Unlike gradient-based methods, DE requires no differentiable objective functions, enabling its application to non-differentiable, multi-modal, and noisy optimization problems commonly encountered in scientific domains [16] [17]. For ODE parameter estimation, this capability proves particularly valuable when model structures are complex or experimental data contains significant noise.

Algorithmic Foundations

Core Operations

DE employs four fundamental operations to evolve a population of candidate solutions toward the global optimum [16] [18]:

Initialization: The algorithm begins by generating an initial population of NP candidate vectors, typically distributed randomly across the search space: (x{i,j}(0) = rand{ij}(0,1) \times (x{ij}^{U} - x{ij}^{L}) + x{ij}^{L}) where (x{ij}^{U}) and (x_{ij}^{L}) represent the upper and lower bounds for the j-th dimension [19].

Mutation: For each target vector in the population, DE generates a mutant/donor vector through differential mutation. The classic "DE/rand/1" strategy is formulated as: (V{i}^{G} = X{r1}^{G} + F \cdot (X{r2}^{G} - X{r3}^{G})) where F is the scaling factor controlling amplification of differential variations, and r1, r2, r3 are distinct random indices [16] [20].

Crossover: The trial vector is created by mixing components of the target and mutant vectors through binomial crossover: (u{i,j}^{G} = \begin{cases} v{i,j}^{G} & \text{if } randj(0,1) \leq CR \text{ or } j = j{rand} \ x_{i,j}^{G} & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}) where CR is the crossover probability controlling the fraction of parameters inherited from the mutant vector [20] [19].

Selection: The trial vector competes against the target vector in a greedy selection process to determine which survives to the next generation: (X{i}^{G+1} = \begin{cases} U{i}^{G} & \text{if } f(U{i}^{G}) \leq f(X{i}^{G}) \ X_{i}^{G} & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}) for minimization problems [18] [19].

Algorithm Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete DE workflow:

Advanced DE Variants for Enhanced Performance

While the classic DE algorithm demonstrates robust performance, recent research has developed enhanced variants that address its limitations, particularly for complex parameter estimation problems.

Adaptive Parameter Control

A significant advancement in DE research involves adaptive control of key parameters (F and CR) to eliminate manual tuning. The MPNBDE algorithm introduces a Birth & Death process and conditional opposition-based learning to automatically escape local optima [21]. Reinforcement learning-based approaches like RLDE establish dynamic parameter adjustment mechanisms using policy gradient networks, enabling online adaptive optimization of scaling factors and crossover probabilities [19].

Multi-Strategy and Multi-Population Approaches

Modern DE variants often employ multiple mutation strategies to balance exploration and exploitation. The APDSDE algorithm implements an adaptive switching mechanism between "DE/current-to-pBest-w/1" and "DE/current-to-Amean-w/1" strategies [20]. MPMSDE incorporates multi-population cooperation with dynamic resource allocation to distribute computational resources rationally across different evolutionary strategies [21].

Table 1: Advanced DE Variants and Their Characteristics

| Variant | Key Features | Advantages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| MPNBDE | Birth & Death process, opposition-based learning with condition | Automatic escape from local optima, accelerated convergence | [21] |

| APDSDE | Adaptive switching between dual mutation strategies, cosine similarity-based parameter adaptation | Balanced exploration-exploitation, improved convergence speed | [20] |

| RLDE | Reinforcement learning-based parameter adjustment, Halton sequence initialization | Adaptive parameter control, uniform population distribution | [19] |

| JADE | Optional external archive, adaptive parameter update | Improved convergence performance, reduced parameter sensitivity | [20] |

Application to ODE Parameter Estimation

Problem Formulation

Parameter estimation for ODE models in pharmacological applications involves finding parameter values that minimize the difference between model predictions and experimental observations. For a dynamical system described by (\frac{dy}{dt} = f(t,y,\theta)) with measurements (y{exp}(ti)), the optimization problem becomes: (\min{\theta} \sum{i=1}^{N} [y{exp}(ti) - y(t_i,\theta)]^2) where θ represents the unknown parameters to be estimated [17].

DE-Based Estimation Protocol

The following workflow illustrates the complete ODE parameter estimation process using DE:

Experimental Protocol for Pharmacokinetic Modeling

Objective: Estimate absorption (ka), elimination (ke), and volume of distribution (Vd) parameters from plasma concentration-time data.

Materials and Software Requirements:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Item | Specification | Function/Role |

|---|---|---|

| ODE Solver | MATLAB ode45, R deSolve, or Python solve_ivp | Numerical integration of differential equations |

| DE Implementation | Custom implementation or established libraries (SciPy, DEoptim) | Optimization engine for parameter estimation |

| Experimental Data | Plasma concentration measurements at multiple time points | Target dataset for model fitting |

| Computing Environment | CPU/GPU resources for parallel population evaluation | Accelerate the optimization process |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Problem Setup:

- Define the pharmacokinetic ODE model: (\frac{dA}{dt} = -ka \cdot A) (gut compartment), (\frac{dC}{dt} = ka \cdot A - ke \cdot C) (plasma compartment)

- Identify parameters to estimate: θ = [ka, ke, Vd]

- Set physiologically plausible parameter bounds: ka ∈ [0.1, 5], ke ∈ [0.01, 2], Vd ∈ [5, 100]

DE Configuration:

- Population size: NP = 50 for 3 parameters

- Mutation strategy: DE/rand/1 or DE/current-to-best/1

- Parameter adaptation: F = 0.8, CR = 0.9 as starting values

- Stopping criterion: 2000 generations or fitness < 1e-6

Fitness Function Implementation:

- For each parameter candidate, numerically solve the ODE system

- Calculate weighted sum of squared residuals: (Fitness = \sum wi (C{obs}(ti) - C{pred}(t_i))^2)

- Implement appropriate weighting scheme (e.g., proportional to measurement error)

Optimization Execution:

- Initialize population uniformly across parameter bounds

- Run DE optimization for specified generations

- Monitor convergence through fitness history and parameter trajectories

Validation and Analysis:

- Assess goodness-of-fit through visual predictive checks and residual analysis

- Perform identifiability analysis using profile likelihood or bootstrap methods

- Validate parameters with independent dataset if available

Performance Considerations and Benchmarking

Parameter Settings for ODE Problems

Successful application of DE to ODE parameter estimation requires appropriate parameter settings. Experimental studies suggest optimal configurations vary based on problem characteristics:

Table 3: Recommended DE Parameter Settings for ODE Estimation Problems

| Problem Dimension | Population Size | Mutation Strategy | F Value | CR Value | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (1-10 parameters) | 50-100 | DE/rand/1 or DE/current-to-best/1 | 0.5-0.8 | 0.7-0.9 | Adequate for most PK/PD models |

| Medium (10-50 parameters) | 100-200 | DE/current-to-pbest/1 or adaptive strategies | 0.5-0.9 | 0.9-0.95 | Larger population for complex systems |

| High (50+ parameters) | 200-500 | Composite strategies with adaptation | 0.4-0.6 | 0.95-0.99 | Requires population size reduction schemes |

Comparative Performance

Recent benchmarking studies demonstrate that advanced DE variants consistently outperform basic DE and other optimization methods for ODE parameter estimation problems. The MPNBDE algorithm shows superior performance in both calculation accuracy and convergence speed across 21 benchmark functions [21]. Similarly, APDSDE demonstrates robust performance on CEC2017 benchmark functions, particularly in high-dimensional optimization scenarios [20].

Differential Evolution provides a powerful, versatile approach for ODE parameter estimation in pharmacological research and drug development. Its simplicity, robustness, and minimal requirements on objective function smoothness make it particularly suitable for complex biological systems where traditional gradient-based methods struggle. Recent advancements in adaptive parameter control, multi-strategy frameworks, and reinforcement learning integration have further enhanced DE's capabilities for challenging estimation problems.

For researchers implementing DE in practical applications, we recommend starting with established adaptive variants like JADE or SHADE, which reduce the parameter tuning burden while maintaining robust performance. The integration of problem-specific knowledge through appropriate boundary constraints and fitness function formulation remains crucial for successful parameter estimation in real-world pharmacological applications.

Differential Evolution (DE) is a powerful evolutionary algorithm designed for global optimization over continuous spaces. It belongs to a broader class of metaheuristics that make few or no assumptions about the problem being optimized and can search very large spaces of candidate solutions [16]. DE was introduced by Storn and Price in the mid-1990s and has since gained popularity due to its robustness, simplicity, and effectiveness in handling non-differentiable, nonlinear, and multimodal objective functions [22] [17]. Unlike gradient-based methods that require differentiability, DE treats the optimization problem as a black box, requiring only a measure of quality (fitness) for any candidate solution [16]. This makes it particularly valuable for complex real-world problems where objective functions may be noisy, change over time, or lack closed-form expressions.

In the context of estimating parameters for Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs)—a common task in pharmacological modeling and drug development—DE offers significant advantages. Models of drug kinetics, receptor binding, and cell signaling pathways often involve ODEs with unknown parameters that must be estimated from experimental data. DE can efficiently navigate high-dimensional parameter spaces to find values that minimize the difference between model predictions and experimental observations, even when the model is non-differentiable with respect to its parameters.

Core Operations of Differential Evolution

The DE algorithm operates on a population of candidate solutions, iteratively improving them through three main operations: mutation, crossover, and selection. These operations work together to balance exploration of the search space with exploitation of promising regions [16] [23]. The algorithm maintains a population of NP candidate solutions, often called agents, each represented as a vector of real numbers. After random initialization within specified bounds, the population evolves over generations through the repeated application of mutation, crossover, and selection until a termination criterion is met [22] [24].

Table 1: Core Components of Differential Evolution

| Component | Description | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Set of candidate solutions (agents) | NP (Population size, typically ≥4) |

| Mutation | Generates a mutant vector by combining existing solutions | F (Scale factor, typically ∈ [0, 2]) |

| Crossover | Mixes parameters of mutant and target vectors to produce a trial vector | CR (Crossover rate, typically ∈ [0, 1]) |

| Selection | Chooses between the target vector and the trial vector for the next generation | Based on fitness (greedy one-to-one selection) |

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of the DE algorithm, showing how these core operations interact sequentially and how the population evolves over generations.

Diagram 1: Differential Evolution Algorithm Workflow

Mutation Operation

The mutation operation introduces new genetic material into the population by creating a mutant vector for each member of the population (called the target vector). This is a distinctive feature of DE, as mutation uses the weighted difference between two or more randomly selected population vectors to perturb another vector [16] [24]. The most common mutation strategy, known as DE/rand/1, produces a mutant vector v_i for each target vector x_i in the population according to the following formula:

v_i = x_{r1} + F * (x_{r2} - x_{r3}) [23]

Here, x_{r1}, x_{r2}, and x_{r3} are three distinct vectors randomly selected from the current population, and F is the scale factor, a positive real number that controls the amplification of the differential variation (x_{r2} - x_{r3}) [16] [22]. The indices r1, r2, r3 are different from each other and from the index i of the target vector, requiring a minimum population size of NP ≥ 4 [19].

Table 2: Common DE Mutation Strategies

| Strategy | Formula | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| DE/rand/1 | v_i = x_{r1} + F * (x_{r2} - x_{r3}) |

Promotes exploration, helps avoid local optima. |

| DE/best/1 | v_i = x_{best} + F * (x_{r1} - x_{r2}) |

Encourages exploitation by using the best solution. |

| DE/current-to-best/1 | v_i = x_i + F * (x_{best} - x_i) + F * (x_{r1} - x_{r2}) |

Balances exploration and exploitation. |

In pharmacological ODE parameter estimation, mutation enables broad exploration of the parameter space. For instance, when fitting a model of drug receptor interaction, mutation allows the algorithm to simultaneously adjust multiple parameters (e.g., binding affinity K_d and internalization rate k_int) in a coordinated manner based on successful combinations found in other candidate solutions.

Crossover Operation

Following mutation, the crossover operation generates a trial vector by mixing the parameters of the mutant vector with those of the target vector [16] [23]. The purpose of crossover is to increase the diversity of the population by creating new, potentially beneficial combinations of parameters [25]. The most common type of crossover in DE is binomial crossover, which operates on each dimension of the vectors independently.

In binomial crossover, for each component j of the trial vector u_i, a decision is made to inherit the value either from the mutant vector v_i or from the target vector x_i. This process is governed by the crossover rate CR, which is a user-defined parameter between 0 and 1 [16] [22]. The operation can be summarized as follows:

u_{i,j} = v_{i,j} if rand(0,1) ≤ CR or j = j_rand

u_{i,j} = x_{i,j} otherwise [23]

Here, j_rand is a randomly chosen index that ensures the trial vector differs from the target vector in at least one parameter, even if the crossover probability is very low [16]. This guarantees that the algorithm continues to explore new points in the search space.

For ODE parameter estimation, crossover allows the algorithm to combine promising parameter subsets from different candidate solutions. For example, a trial solution might inherit the K_d parameter from a mutant vector that accurately describes initial binding kinetics, while retaining the k_int parameter from a target vector that better fits long-term internalization data.

Selection Operation

The selection operation in DE is a deterministic, greedy process that decides whether the trial vector should replace the target vector in the next generation [22] [24]. Unlike some other evolutionary algorithms that use probabilistic selection, DE directly compares the fitness of the trial vector against that of the target vector. For a minimization problem, the selection operation is defined as:

x_i^{t+1} = u_i^t if f(u_i^t) ≤ f(x_i^t)

x_i^{t+1} = x_i^t otherwise [23]

This one-to-one selection scheme is straightforward and computationally efficient. If the trial vector yields an equal or better fitness value (lower objective function value for minimization problems), it replaces the target vector in the next generation; otherwise, the target vector is retained [16] [22]. This greedy selection pressure drives the population toward better regions of the search space over successive generations.

In the context of ODE parameter estimation for drug development, the fitness function f(x) is typically a measure of how well the ODE model with parameter set x fits experimental data. Common choices include the Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) between model predictions and experimental measurements. The selection operation ensures that parameter sets providing better fits to the data are preserved and used to guide future exploration.

Experimental Protocols for ODE Parameter Estimation

Problem Formulation and Fitness Evaluation

When applying DE to estimate parameters of ODEs in pharmacological research, the first step is to define the objective function precisely. For a typical ODE model of a biological process, the objective is to find the parameter set θ that minimizes the difference between the model's predictions and experimental observations. The fitness function is often formulated as a least-squares problem:

SSE(θ) = Σ (y_model(t_i, θ) - y_data(t_i))^2

Here, y_model(t_i, θ) is the solution of the ODE system at time t_i with parameters θ, and y_data(t_i) is the corresponding experimental measurement [12]. The ODE system is numerically integrated for each candidate parameter set to obtain the model predictions. For problems involving multiple measured species, a weighted sum of squared errors may be used if different variables have different scales or measurement uncertainties.

Implementation Protocol

The following protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for implementing DE to estimate parameters in a pharmacokinetic ODE model, such as a compartmental model of drug absorption, distribution, and elimination.

Step 1: Define the ODE Model and Bounds Specify the system of ODEs that constitutes the model. Establish realistic lower and upper bounds for each parameter based on biological plausibility or prior knowledge. For example, rate constants should typically be positive, and dissociation constants might be constrained to physiologically relevant ranges.

Step 2: Initialize the Population

Randomly generate an initial population of NP candidate parameter vectors within the specified bounds. The population size NP is often set as 10n, where n is the number of parameters to be estimated [16].

x_{i,j} = bound_j_lower + rand(0,1) * (bound_j_upper - bound_j_lower)

Step 3: Evaluate Initial Fitness For each candidate parameter vector in the initial population, numerically solve the ODE system and compute the SSE against the experimental data.

Step 4: Evolve the Population For each generation until termination criteria are met:

- Mutation: For each target vector, select three distinct random vectors from the population and generate a mutant vector using the

DE/rand/1strategy:v_i = x_{r1} + F * (x_{r2} - x_{r3}). - Crossover: For each dimension of the target vector, create a trial vector by mixing components from the mutant and target vectors based on the crossover rate

CR. - Selection: For each trial vector, solve the ODE system and compute its SSE. If the trial vector's SSE is less than or equal to the target vector's SSE, replace the target vector with the trial vector in the next generation.

Step 5: Check Termination Criteria Continue the evolutionary process until a maximum number of generations is reached, a satisfactory fitness value is achieved, or the population converges (improvement falls below a threshold).

Step 6: Validation Validate the best parameter set by assessing the model's fit to a separate validation dataset (if available) and performing sensitivity analysis or identifiability analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for DE Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

ODE Solver Library (e.g., scipy.integrate.solve_ivp in Python, deSolve in R) |

Numerically integrates ODE systems to generate model predictions for given parameters. | Core to fitness evaluation; must be robust and efficient. |

DE Implementation Framework (e.g., DEAP in Python, DEoptim in R) |

Provides pre-built functions for DE operations (mutation, crossover, selection). | Accelerates development; offers tested, optimized variants. |

| Parameter Bounds Definition | Constrains the search space to biologically/physically plausible values. | Prevents unrealistic solutions; improves convergence speed. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Enables parallel fitness evaluations for large populations or complex models. | Reduces computation time for computationally intensive ODE models. |

Sensitivity Analysis Tool (e.g., SALib in Python) |

Assesses how uncertainty in model output is apportioned to different parameters. | Post-estimation analysis to evaluate parameter identifiability and model robustness. |

Advanced Considerations and Parameter Tuning

The performance of DE in ODE parameter estimation depends significantly on the choice of control parameters NP, F, and CR. While canonical settings suggest NP = 10n, F = 0.8, and CR = 0.9 [16], these may require adjustment for specific problems. Recent research has focused on adaptive parameter control mechanisms. For instance, reinforcement learning-based DE variants dynamically adjust F and CR during the optimization process, enhancing performance on complex problems [19].

When applying DE to stiff ODE systems commonly encountered in pharmacological modeling (e.g., models with rapidly and slowly changing variables), special attention should be paid to the numerical integration method. Implicit or stiff ODE solvers may be necessary to maintain stability and accuracy during fitness evaluation. Additionally, for models with poorly identifiable parameters, techniques such as regularization or Bayesian inference frameworks that incorporate prior knowledge may be combined with DE to improve results.

DE has been successfully applied to various complex optimization problems, including parameter estimation for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell models, where it demonstrated superior accuracy and computational efficiency compared to other algorithms [12]. These successes in challenging domains underscore its potential for ODE parameter estimation in pharmacological research and drug development.

Differential Evolution (DE) is a cornerstone of modern evolutionary algorithms, renowned for its effectiveness in solving complex optimization problems across scientific and engineering disciplines. Its reputation stems from a powerful combination of simplicity, robustness, and reliable performance when applied to challenging, non-convex landscapes. For researchers engaged in parameter estimation for Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs)—a task fundamental to modeling in systems biology, pharmacology, and chemical kinetics—these attributes are particularly critical. The process of calibrating ODE models to experimental data often presents a rugged, multi-modal optimization terrain where gradient-based methods can falter. DE excels in this context by offering a versatile and powerful alternative. This article delineates the core advantages of DE, provides a structured overview of its core algorithm, and presents detailed protocols for its implementation in ODE parameter estimation, complete with performance data and essential workflows for the practicing scientist.

The widespread adoption of DE in research and industry is underpinned by several key operational advantages.

- Few Control Parameters: DE operates effectively with a minimal set of control parameters, typically just three: the population size (NP), the scaling factor (F), and the crossover rate (CR) [26] [27]. This simplicity drastically reduces the preliminary tuning effort required compared to many other metaheuristics, making DE more accessible and easier to implement for new and complex problems.

- Gradient-Free Operation: As a population-based stochastic algorithm, DE does not require derivative information of the objective function [27]. This makes it exceptionally suited for optimizing problems where the objective function is noisy, non-differentiable, discontinuous, or defined by black-box simulations, which is a common scenario in ODE parameter estimation for biological systems [9] [28].

- Proven Robustness: DE is "arguably one of the most versatile and stable population-based search algorithms that exhibits robustness to multi-modal problems" [27]. Its design, which balances exploration of the search space and exploitation of promising solutions, helps it avoid premature convergence and reliably locate near-optimal solutions even in challenging, high-dimensional spaces.

The standard DE algorithm is a structured yet straightforward process, as visualized below.

Figure 1: The standard Differential Evolution workflow, illustrating the iterative cycle of mutation, crossover, and selection.

The DE process begins with the random initialization of a population of candidate solution vectors within the parameter bounds [20]. Each generation (iteration) involves three key steps [20] [27]:

- Mutation: For each candidate solution (the "target vector"), a "donor vector" is created by combining other individuals from the population. A common strategy is "DE/rand/1": ( Vi^G = X{r1}^G + F \cdot (X{r2}^G - X{r3}^G) ), where ( F ) is the scaling factor and ( r1, r2, r3 ) are random, distinct indices.

- Crossover: The donor vector mixes with the target vector to produce a "trial vector." Binomial crossover is standard, where each parameter in the trial vector is inherited either from the donor vector (with probability CR) or the target vector.

- Selection: The fitness of the trial vector is compared to that of the target vector. The superior vector survives to the next generation, ensuring the population's quality improves iteratively.

Application in ODE Parameter Estimation

Parameter estimation in ODE models is a fundamental dynamic optimization problem. Given a model defined by ( \frac{d\boldsymbol{x}(t)}{dt} = f(t, \boldsymbol{x}(t), \boldsymbol{p}) ) and experimental data ( \boldsymbol{y}(t) ), the goal is to find the parameter values ( \boldsymbol{p} ) that minimize the difference between model predictions and observed data [9]. This problem is often nonconvex, leading to multiple local minima that can trap local optimization methods [9]. DE's global search capability and robustness to multi-modal landscapes make it a powerful tool for this task, as it can navigate complex parameter spaces to find a globally optimal solution without requiring gradient information.

Performance of DE Variants in Practical Applications

The performance of DE and its modern variants has been quantitatively demonstrated in recent scientific studies. The table below summarizes key results from two applications: parameter estimation for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell (PEMFC) models and constrained structural optimization.

Table 1: Performance of DE Variants in Engineering and Modeling Applications

| Application Area | DE Variant | Key Performance Metric | Reported Result | Comparison / Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEMFC Parameter Estimation [12] | Two-stage DE (TDE) | Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) | 0.0255 (min) | 41% reduction vs. HARD-DE (SSE: 0.0432) |

| Computational Runtime | 0.23 seconds | 98% more efficient than HARD-DE (11.95 s) | ||

| Standard Deviation of SSE | >99.97% reduction | Demonstrated superior robustness | ||

| Constrained Structural Optimization [27] | Standard DE & Adaptive Variants (JADE, SADE, etc.) | Final Optimum Result & Convergence Rate | Most reliable and robust performance | Outperformed PSO, GA, and ABC in truss structure optimization |

These results underscore DE's capability for high accuracy and computational efficiency in parameter-sensitive domains. The TDE algorithm, in particular, showcases how specialized DE variants can achieve significant performance gains.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Parameter Estimation for a Dynamic Systems Biology Model

This protocol outlines the steps for estimating kinetic parameters in an ODE model of a biological pathway (e.g., glycolysis or a pharmacokinetic model) using a DE algorithm.

1. Problem Formulation:

- Objective Function: Define the objective as minimizing the Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) between experimental data and model predictions [12]: ( SSE(\boldsymbol{p}) = \sum (\boldsymbol{y}{measured} - \boldsymbol{y}{predicted}(\boldsymbol{p}))^2 ).

- Parameters to Estimate: Identify the vector ( \boldsymbol{p} ) (e.g., reaction rate constants, initial conditions).

- Constraints: Define plausible lower and upper bounds for each parameter based on biological knowledge [28].

2. Algorithm Selection and Setup:

- Variant Selection: For beginners, standard DE/rand/1/bin is recommended. For more complex problems, consider advanced variants like TDE [12] or JADE [20].

- Parameter Tuning: Set initial DE parameters. A common starting point is NP=50, F=0.5, CR=0.9. Adaptive parameter strategies are preferred for complex problems [20].

- Termination Criterion: Define a stopping condition, such as a maximum number of generations (e.g., 1000) or a tolerance in fitness improvement.

3. Implementation and Execution:

- Population Initialization: Randomly initialize NP candidate solutions within the predefined parameter bounds [20].

- Iterative Optimization: For each generation, perform mutation, crossover, and selection. In the selection step, numerically solve the ODE model for each trial vector to compute its fitness.

- Solution Validation: Run the optimization multiple times with different random seeds to check for consistency. Validate the best solution on a withheld portion of the experimental data.

Protocol 2: Training a Universal Differential Equation (UDE)

UDEs combine mechanistic ODEs with machine learning components (e.g., neural networks) to model systems with partially unknown dynamics [28]. DE can robustly estimate the mechanistic parameters of a UDE.

1. UDE Formulation:

- Model Structure: Define the known part of the system with ODEs. Replace the unknown or complex parts with a neural network ( NN(\boldsymbol{x}(t), \theta{ANN}) ), where ( \theta{ANN} ) are the network weights [28]. The hybrid system becomes: ( \frac{d\boldsymbol{x}(t)}{dt} = f{known}(t, \boldsymbol{x}(t), \boldsymbol{p}) + NN(\boldsymbol{x}(t), \theta{ANN}) ).

- Parameter Sets: The total parameter set includes mechanistic parameters ( \thetaM ) and ANN parameters ( \theta{ANN} ).

2. Hybrid Optimization Strategy:

- Role of DE: Use a multi-start DE to find a robust global estimate for the mechanistic parameters ( \thetaM ) and the initial values for ( \theta{ANN} ). This helps avoid poor local minima.

- Refinement: The solutions from DE can be used as initial points for a local, gradient-based optimizer (e.g., Adam) to fine-tune all parameters ( (\thetaM, \theta{ANN}) ) simultaneously [28].

3. Regularization and Validation:

- Apply weight decay (L2 regularization) to the ANN parameters to prevent overfitting and ensure the mechanistic parameters remain interpretable [28].

- Use techniques like cross-validation and profile likelihood to assess the identifiability of the mechanistic parameters ( \theta_M ) within the UDE framework.

The workflow for implementing and training a UDE is summarized in the following diagram.

Figure 2: A hybrid optimization pipeline for training Universal Differential Equations (UDEs), leveraging DE for robust global initialization.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section catalogs key computational reagents and resources essential for implementing DE in ODE parameter estimation research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for DE-based ODE Parameter Estimation

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| ODE Solver | Software Library | Numerically integrates the ODE system to generate model predictions for a given parameter set. | Solvers in SciML (Julia) [28], scipy.integrate.odeint (Python), or specialized stiff solvers (e.g., KenCarp4) [28]. |

| DE Implementation | Algorithm Code | Provides the optimization engine. | Standard DE variants are available in scipy.optimize.differential_evolution (Python). For advanced variants (JADE, TDE), custom implementation may be needed. |

| Objective Function | Code Wrapper | Calculates the fitness (e.g., SSE) by comparing ODE solver output to experimental data. | A custom function that calls the ODE solver and returns a scalar fitness value. |

| Parameter Bounds | Input Configuration | Defines the feasible search space for each parameter, guiding the optimization and incorporating prior knowledge. | A simple list of (lowerbound, upperbound) pairs for each parameter. |

| Data (Synthetic/Experimental) | Dataset | Serves as the ground truth for fitting the model. Synthetic data is useful for method validation. | Time-series measurements of the system's states [9]. |

| Log/Likelihood Function | Optional Code | Used for rigorous statistical inference and uncertainty quantification of parameter estimates [28]. | Can be incorporated into the objective function for maximum likelihood estimation. |

A Step-by-Step Workflow: Implementing DE for Your ODE Models

Formulating the ODE Parameter Estimation as an Optimization Problem

The accurate calibration of models based on Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) is a cornerstone of computational science, with profound implications across fields from systems biology to energy systems engineering [28]. This process, known as parameter estimation, is inherently an inverse problem where one seeks the parameter values that cause the model's predictions to best match observed experimental data. This guide, framed within a broader thesis on implementing Differential Evolution (DE) for such tasks, details the formulation of parameter estimation as a numerical optimization problem. We provide application notes, detailed experimental protocols, and essential toolkits for researchers, with a particular focus on methodologies relevant to drug development and complex biological system modeling [11] [28].

The core challenge lies in the fact that ODE models of biological or physical processes are often nonlinear and contain parameters that cannot be measured directly [11] [29]. Instead, these parameters must be inferred from time-series data, leading to a high-dimensional, non-convex optimization landscape where traditional local search methods may fail [10] [30]. This justifies the exploration of robust global optimization metaheuristics, such as Differential Evolution and its advanced variants [12].

Core Mathematical Formulation

The parameter estimation problem for dynamic systems is formalized as a nonlinear programming (NLP) or nonlinear least-squares problem [11] [30]. Consider a dynamical system described by a set of ODEs:

dx(t)/dt = f(x(t), u(t), θ), with initial condition x(t₀) = x₀.

Here, x(t) ∈ ℝⁿ is the state vector, u(t) denotes input variables, and θ ∈ ℝᵖ is the vector of unknown parameters to be estimated [11].

The system output, which can be measured, is given by y(t) = g(x(t), u(t), θ). Given a set of N experimental measurements ŷ(t_i) at times t_i, the standard formulation is to minimize the discrepancy between the model output and the data.

The most common formulation is the Sum of Squared Errors (SSE), which serves as the objective function J(θ) [12] [11]:

J(θ) = Σ_{i=1}^{N} [ŷ(t_i) - y(t_i, θ)]²

The optimization problem is then:

θ* = arg min_θ J(θ), subject to θ_L ≤ θ ≤ θ_U

where θ_L and θ_U are plausible lower and upper bounds for the parameters, often derived from prior knowledge or physical constraints [28].

Alternative objective functions include the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), or likelihood functions when measurement error characteristics are known [11] [28].

Algorithms and Experimental Protocols

Global Optimization via Differential Evolution (DE) and Variants

Protocol: Two-Stage Differential Evolution (TDE) for Parameter Estimation This protocol is adapted from the successful application of TDE for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell model calibration, demonstrating high efficiency and accuracy [12].

- Problem Definition:

- Define the ODE model

f(x(t), θ)and the measurable output functiong(x(t), θ). - Define the parameter vector

θand its feasible bounds[θ_L, θ_U]. - Load or generate experimental time-series data

{t_i, ŷ_i}. - Select an objective function (e.g., SSE).

- Define the ODE model

Algorithm Initialization (Stage 1 Preparation):

- Set TDE hyperparameters: population size

NP, mutation factorsF1(for stage 1) andF2(for stage 2), crossover probabilityCR, and maximum number of generationsG_max. - Randomly initialize a population of candidate solutions

P = {θ_1, ..., θ_NP}within the defined bounds. - Initialize an archive of historical solutions as empty.

- Set TDE hyperparameters: population size

Stage 1 - Exploration with Historical Mutation:

- For each generation

guntil a switching criterion (e.g., half ofG_max):- For each target vector

θ_i,gin the population:- Mutation: Generate a mutant vector

v_iusing a strategy that incorporates randomly selected vectors from both the current population and the historical archive to enhance diversity. Example:v = θ_r1 + F1 * (θ_r2 - θ_r3) + F1 * (θ_arch - θ_r4), whereθ_archis from the archive. - Crossover: Perform binomial crossover between

θ_i,gandv_ito create a trial vectoru_i. - Selection: Numerically integrate the ODE for both

θ_i,gandu_ito computeJ(θ). IfJ(u_i) ≤ J(θ_i,g), thenθ_i,g+1 = u_i; otherwise,θ_i,g+1 = θ_i,g. Successful trial vectors are stored in the historical archive.

- Mutation: Generate a mutant vector

- For each target vector

- For each generation

Stage 2 - Exploitation with Guided Mutation:

- For the remaining generations:

- For each target vector

θ_i,g:- Mutation: Generate a mutant vector using a strategy focused on the direction of inferior solutions to refine search. Example:

v = θ_best + F2 * (θ_inferior1 - θ_inferior2), whereθ_bestis the current best solution. - Crossover & Selection: Repeat crossover and selection as in Stage 1.

- Mutation: Generate a mutant vector using a strategy focused on the direction of inferior solutions to refine search. Example:

- For each target vector

- For the remaining generations:

Termination & Validation:

- The algorithm terminates after

G_maxgenerations or when convergence criteria are met. - The solution

θ*with the smallestJ(θ)is reported. - Validate by simulating the ODE with

θ*and visually/numerically comparing the trajectoryy(t, θ*)against the experimental dataŷ(t).

- The algorithm terminates after

Direct Transcription and Collocation-Based Methods

Protocol: Profiled Estimation Procedure (PEP) for ODEs This protocol outlines an alternative to "shooting" methods, bypassing repeated numerical integration by approximating the state trajectory directly [11].

- Discretization:

- Choose a set of collocation points

{τ_k}spanning the observation time horizon. - Represent each state variable

x_j(t)as a linear combination of basis functions (e.g., B-splines):x_j(t) ≈ Σ_{l=1}^{L} c_{jl} * ϕ_l(t), wherec_{jl}are coefficients to be estimated.

- Choose a set of collocation points

Three-Level Optimization Formulation:

- Inner Level: Given fixed parameters

θand smoothing coefficientsλ, optimize the basis coefficientscto fit the data and satisfy the ODE constraints approximately at collocation points. The objective is to minimize:Σ_i [ŷ_i - g(x(t_i), θ)]² + λ * Σ_k [dx(τ_k)/dt - f(x(τ_k), θ)]². - Middle Level: Optimize the smoothing parameters

λ. - Outer Level: Optimize the mechanistic parameters

θby minimizing the fitted error from the inner level. The gradients required for optimizingθcan be computed efficiently using the Implicit Function Theorem, avoiding full re-optimization ofcat each step.

- Inner Level: Given fixed parameters

Solution:

Hybrid and Machine Learning-Enhanced Methods

Protocol: Training a Universal Differential Equation (UDE) UDEs combine a mechanistic ODE core with a neural network (NN) to represent unknown dynamics [29] [28].

- Model Formulation: Define the hybrid system:

dx/dt = f_mechanistic(x, θ_M) + f_NN(x, θ_NN), whereθ_Mare interpretable mechanistic parameters andθ_NNare neural network weights. - Pipeline Setup (Multi-start Strategy):

- Reparameterization: Apply log-transformation to

θ_Mto handle parameters spanning orders of magnitude and enforce positivity [28]. - Regularization: Apply L2 weight decay (e.g.,

λ||θ_NN||²) to the NN parameters to prevent overfitting and maintain model interpretability [28]. - Numerical Solving: Use a stiff ODE solver (e.g., Tsit5, KenCarp4) for the forward pass, especially for biological systems [28].

- Optimization: Use a multi-start strategy, jointly sampling initial values for

θ_M,θ_NN, and hyperparameters (learning rate, NN architecture). Optimize using a combination of gradient-based methods (e.g., Adam) forθ_NNand global search forθ_M.

- Reparameterization: Apply log-transformation to

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes key quantitative results from recent studies on ODE parameter estimation algorithms, highlighting the performance gains achievable with advanced methods.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ODE Parameter Estimation Algorithms

| Algorithm / Study | Application Context | Key Performance Metric | Result | Comparative Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-Stage DE (TDE) [12] | PEM Fuel Cell Parameter ID | SSE (Sum Squared Error) | 0.0255 (min) | 41% reduction vs. HARD-DE (0.0432) |

| Runtime | 0.23 s | 98% more efficient vs. HARD-DE (11.95 s) | ||

| Std. Dev. of SSE | >99.97% reduction | vs. HARD-DE | ||

| Profiled Estimation (PEP) [11] | Crop Growth Model Calibration | RMSE / MAE / Modeling Efficiency | Outperformed DE | Better fit statistics for a maize model |

| Stochastic Newton-Raphson (SNR) [10] | General ODE Systems | Bias, MAE, MAPE, RMSE, R² | Outperformed NLS | Improved accuracy across multiple error metrics |

| Direct Transcription + Global Solver [30] | Nonlinear Dynamic Biological Systems | Problem Solution Capability | Surpassed previously reported results | Handled challenging identifiability problems |

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Diagram 1: Optimization Strategy Selection Workflow.

Diagram 2: Nested Structure of the Profiled Estimation Procedure.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for ODE Parameter Estimation Research

| Tool Category | Specific Solution / Algorithm | Primary Function in Estimation Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Global Optimizers | Differential Evolution (DE), Two-Stage DE (TDE) [12], Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Explore high-dimensional, non-convex parameter spaces to locate the global minimum of the objective function, avoiding local traps. |

| Local/Gradient Optimizers | Nonlinear Least Squares (NLS), Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), Stochastic Newton-Raphson (SNR) [10] | Efficiently refine parameter estimates from a good initial guess; SNR offers fast convergence for large-scale problems. |

| Direct Transcription Solvers | Collocation-based NLP Solvers (IPOPT) [31], Profiled Estimation (PEP) [11] | Discretize and solve the estimation problem simultaneously, bypassing the need for nested ODE integration, improving stability. |

| Hybrid Model Frameworks | Universal Differential Equations (UDEs) [28], NeuralODEs [29] | Augment incomplete mechanistic models with data-driven components (neural networks) to learn unmodeled dynamics. |

| Numerical Integrators | Runge-Kutta methods (e.g., Tsit5), Stiff Solvers (e.g., KenCarp4, Rodas) [28] | Provide accurate and efficient numerical solutions to the ODE system for a given parameter set during objective function evaluation. |

| Parameter Transformers | Log-Transform, tanh-based Bounding Transform [28] | Handle parameters spanning multiple orders of magnitude and enforce bound constraints (e.g., positivity), improving optimizer performance. |

| Regularization Agents | L2 Weight Decay (λ‖θ‖²) [28] | Prevent overfitting in flexible models (e.g., NNs in UDEs), promoting generalizability and interpretability of mechanistic parameters. |

Direct transcription is a numerical method for solving trajectory optimization problems by discretizing ordinary differential equations (ODEs) into a finite-dimensional nonlinear programming (NLP) problem. This approach transforms the continuous problem of finding an optimal trajectory into a discrete parameter optimization problem that can be solved using standard NLP solvers. Within the context of differential evolution for ODE parameter estimation, direct transcription provides a robust framework for handling complex biological systems where parameters must be estimated from experimental data.

The method has gained significant traction in robotics and systems biology due to its ability to handle high-dimensional state spaces and path constraints effectively. By discretizing the entire trajectory simultaneously, direct transcription avoids the numerical sensitivity issues associated with shooting methods, making it particularly suitable for unstable systems common in biological applications [32].

Theoretical Foundation

Mathematical Formulation of Direct Transcription

Direct transcription works by approximating the continuous-time optimal control problem:

where x(t) represents the state variables, u(t) represents the control inputs, f defines the system dynamics, h represents path constraints, and g represents terminal constraints.

The transcription process discretizes the time interval into N nodes: t₀ < t₁ < ... < t_N, and approximates both states and controls at these discrete points. The differential equations are converted to algebraic constraints through numerical integration schemes [32].

Discretization Schemes

The choice of discretization scheme significantly impacts the accuracy and computational efficiency of the transcribed problem. The most common methods include:

Table 1: Comparison of Direct Transcription Discretization Methods

| Method | Accuracy Order | Stability Properties | Computational Cost | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euler Forward | 1st order | Conditional | Low | Low |

| Trapezoidal | 2nd order | Unconditional | Medium | Medium |

| Hermite-Simpson | 3rd order | Unconditional | Medium-High | Medium |

| Runge-Kutta (4th order) | 4th order | Unconditional | High | High |

Experimental studies have shown that the Hermite-Simpson method offers a favorable balance between accuracy and computational expense for biological applications, particularly when dealing with stiff systems commonly encountered in biochemical networks [32].

Integration with Differential Evolution for Parameter Estimation

Synergistic Framework

The combination of direct transcription with differential evolution (DE) creates a powerful framework for ODE parameter estimation. In this hybrid approach:

- Direct transcription converts the continuous parameter estimation problem into a structured NLP problem

- Differential evolution efficiently explores the parameter space to identify optimal values

This synergy is particularly beneficial for biological systems where parameters often have uncertain values spanning multiple orders of magnitude. DE's ability to handle non-convex, multi-modal objective functions complements the structured constraint handling of direct transcription [28] [17].

Algorithmic Integration

The integrated workflow follows these key stages:

- Problem discretization using direct transcription methods

- Parameter bounding based on biological constraints

- Global exploration via differential evolution

- Local refinement using NLP solvers

This combination has demonstrated particular efficacy in systems biology applications, where it successfully estimates parameters in partially known biological networks, effectively balancing mechanistic understanding with data-driven learning [28].

Application Protocol: Parameter Estimation in Biological Systems

Experimental Setup for Glycolysis Modeling

This protocol outlines the application of direct transcription with differential evolution to estimate parameters in a glycolysis model based on Ruoff et al., consisting of seven ODEs with twelve free parameters [28].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Implementation

| Tool Name | Type | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SciML Framework | Software Library | Provides specialized ODE solvers | Use Tsit5 for non-stiff and KenCarp4 for stiff systems [28] |

| Two-stage Differential Evolution (TDE) | Algorithm | Global parameter optimization | Implements historical and inferior solution mutation strategies [12] |

| Multi-start Pipeline | Methodology | Enhances convergence reliability | Jointly samples parameters and hyperparameters [28] |

| Adaptive Differential Evolution (ADE-AESDE) | Algorithm | Maintains population diversity | Uses stagnation detection and multi-phase parameter control [33] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Problem Formulation

- Define the mechanistic ODE model with unknown parameters

- Identify which components will be replaced with neural networks in a UDE approach

- Set parameter bounds based on biological constraints

Discretization Configuration

- Select discretization method (recommended: Hermite-Simpson for balance of accuracy and efficiency)

- Choose number of discretization nodes (typically 50-100 for biological systems)

- Define collocation points for constraint enforcement

Differential Evolution Setup

- Initialize population size (P > 4 for sufficient genetic diversity)

- Set mutation factor F ∈ [0, 2] and crossover constant CR ∈ [0, 1]

- Configure adaptive parameter control if using advanced DE variants [33]

Optimization Execution

- Implement multi-start strategy with diverse initial conditions

- Apply maximum likelihood estimation with regularization

- Enforce parameter constraints through transformation methods

Solution Validation

- Check consistency across multiple runs

- Verify constraint satisfaction

- Assess physical plausibility of parameter values

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Integrated Direct Transcription and Differential Evolution Workflow

Performance Analysis and Benchmarking

Quantitative Assessment

Recent studies have systematically evaluated direct transcription methods for motion planning in robotic systems with relevance to biological parameter estimation [32]:

Table 3: Performance Metrics for Direct Transcription Methods

| Discretization Method | Computational Time (s) | Solution Accuracy (Error Norm) | Constraint Violation | Recommended Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euler Forward | 12.4 ± 2.1 | 1.2e-1 ± 0.03 | 8.5e-2 ± 0.02 | Simple systems, educational purposes |

| Trapezoidal | 25.7 ± 3.8 | 3.5e-3 ± 0.001 | 2.1e-3 ± 0.0005 | Medium-accuracy requirements |

| Hermite-Simpson | 41.2 ± 5.2 | 7.8e-5 ± 0.00002 | 5.4e-5 ± 0.00001 | High-accuracy biological applications |

| Runge-Kutta (4th order) | 68.9 ± 8.3 | 2.1e-6 ± 0.000001 | 1.7e-6 ± 0.000001 | Ultra-high precision requirements |

Differential Evolution Variants Comparison

The Two-stage Differential Evolution (TDE) algorithm demonstrates significant improvements over traditional approaches for parameter estimation [12]:

Table 4: Performance of Differential Evolution Variants for Parameter Estimation

| Algorithm | SSE (Sum of Squared Errors) | Computational Time (s) | Convergence Rate | Robustness to Noise |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard DE | 0.0432 ± 0.005 | 11.95 ± 1.2 | 78% | Moderate |

| HARD-DE | 0.0385 ± 0.004 | 9.34 ± 0.9 | 82% | Good |

| TDE (Two-stage) | 0.0255 ± 0.002 | 0.23 ± 0.05 | 96% | Excellent |

| ADE-AESDE | 0.0218 ± 0.001 | 0.31 ± 0.06 | 94% | Excellent |

TDE achieved a 41% reduction in SSE, a 92% improvement in maximum SSE, and over 99.97% reduction in standard deviation compared to HARD-DE, while being 98% more computationally efficient [12].

Advanced Implementation Considerations

Handling Biological System Challenges

Biological systems present unique challenges that require specialized approaches within the direct transcription framework:

Stiff Dynamics

- Use specialized solvers (Tsit5 for non-stiff, KenCarp4 for stiff systems)

- Implement adaptive time-stepping schemes

- Apply log-transformation for parameters spanning multiple orders of magnitude [28]

Noise and Sparse Data

- Incorporate regularization techniques (L2 regularization with weight decay)

- Utilize maximum likelihood estimation with appropriate error models

- Implement multi-start optimization to avoid local minima [28]

Parameter Identifiability

- Apply profile likelihood methods

- Use sensitivity analysis to identify identifiable parameter combinations

- Implement parameter transformations to enforce biological constraints

System Architecture Diagram

Diagram 2: UDE Framework for Biological Parameter Estimation

Direct transcription provides a robust methodology for discretizing ODEs into nonlinear programming problems, particularly when integrated with differential evolution for parameter estimation. The combination of these approaches enables researchers to tackle complex biological systems where parameters are uncertain and data is limited.

Future research directions include developing more efficient discretization schemes specifically designed for biological systems, improving the scalability of DE for high-dimensional parameter spaces, and enhancing the interpretability of learned parameters in universal differential equation frameworks. The continued refinement of these methodologies will further empower researchers in systems biology and drug development to extract meaningful insights from complex biological data.

Application Notes & Protocols for ODE Parameter Estimation in Drug Development