Gradient-Based Optimization and Sensitivity Analysis: Accelerating Precision Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of gradient-based optimization and sensitivity analysis, powerful computational techniques that are revolutionizing drug discovery.

Gradient-Based Optimization and Sensitivity Analysis: Accelerating Precision Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of gradient-based optimization and sensitivity analysis, powerful computational techniques that are revolutionizing drug discovery. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of these methods, their practical application in tasks like de novo molecule design and target identification, and advanced strategies for overcoming challenges such as chaotic dynamics and high-dimensional data. The review also synthesizes validation frameworks and comparative performance analyses, highlighting how these approaches enhance predictive accuracy, reduce development timelines, and improve the success rate of bringing new therapies to market.

Core Principles: The Theoretical Bedrock of Gradients and Sensitivity in Drug Discovery

Gradient-based optimization forms the computational backbone of modern machine learning and scientific computing, providing the essential mechanisms for minimizing complex loss functions and solving intricate inverse problems. At its core, this family of algorithms iteratively adjusts parameters by moving in the direction of the steepest descent of a function, as defined by the negative of its gradient. In the context of sensitivity analysis research, these methods enable researchers to quantify how the output of a model is influenced by variations in its input parameters, thereby identifying the most critical factors driving system behavior [1]. The fundamental principle underpinning these techniques is the use of first-order derivative information to efficiently navigate high-dimensional parameter spaces toward locally optimal solutions.

The development of gradient-based methods has evolved from simple deterministic approaches to sophisticated adaptive algorithms that automatically adjust their behavior based on the characteristics of the optimization landscape. This progression has been particularly impactful in fields with computationally intensive models, where traditional global optimization methods often prove prohibitively expensive [2]. In pharmaceutical research and drug development, where models must account for complex biological systems and chemical interactions, gradient-based optimization provides a mathematically rigorous framework for balancing multiple competing objectives, such as maximizing drug efficacy while minimizing toxicity and manufacturing costs [3].

Fundamental Algorithms and Their Evolution

Basic Gradient Descent and Its Variants

The simplest manifestation of gradient-based optimization is the classic Gradient Descent algorithm, which operates by repeatedly subtracting a scaled version of the gradient from the current parameter estimate. This approach can be formalized through two key update equations: first, the gradient is computed as g_t = ∇θ_{t-1} f(θ_{t-1}), where f(θ_{t-1}) represents the objective function evaluated at the current parameter values; second, parameters are updated as θ_t = θ_{t-1} - η g_t, where η denotes the learning rate that controls the step size [4]. While straightforward to implement, this basic algorithm suffers from several limitations, including sensitivity to the learning rate selection, tendency to converge to local minima, and slow convergence in regions with shallow gradients.

The Momentum method addresses some of these limitations by incorporating a velocity term that accumulates gradient information across iterations, effectively dampening oscillations in steep valleys and accelerating progress in consistent directions. The algorithm modifies the basic update rule through three sequential calculations: the gradient computation g_t = ∇θ_{t-1} f(θ_{t-1}) remains identical to classic gradient descent; a velocity term is updated as m_t = β m_{t-1} + g_t, where β is the momentum coefficient controlling the persistence of previous gradients; and the parameter update becomes θ_t = θ_{t-1} - η m_t [4]. This introduction of momentum helps the optimizer overcome small local minima and generally leads to faster convergence, though it may still exhibit overshooting behavior when approaching the global minimum if the learning rate is not properly tuned.

Adaptive Learning Rate Methods

A significant advancement in gradient-based optimization came with the development of algorithms featuring adaptive learning rates for each parameter, which address the challenge of sparse or varying gradient landscapes commonly encountered in high-dimensional problems. AdaGrad, the first prominent adaptive method, implements per-parameter learning rates by accumulating the squares of all historical gradients [5]. The algorithm operates through three computational steps: gradient calculation g_t = ∇θ_{t-1} f(θ_{t-1}); accumulation of squared gradients n_t = n_{t-1} + g_t²; and parameter update θ_t = θ_{t-1} - η g_t / (√n_t + ε), where ε is a small constant included for numerical stability [4]. This approach automatically reduces the learning rate for parameters with large historical gradients, making it particularly effective for problems with sparse features. However, AdaGrad has a significant limitation: the continuous accumulation of squared gradients throughout training causes the learning rate to monotonically decrease, potentially leading to premature convergence.

RMSProp emerged as a modification to AdaGrad designed to overcome the aggressive learning rate decay by replacing the cumulative sum of squared gradients with an exponentially moving average [4]. This simple yet crucial modification allows the algorithm to discard information from the distant past, making it more responsive to recent gradient behavior and better suited for non-stationary optimization problems. The Adam algorithm further refined this approach by combining the concepts of momentum and adaptive learning rates, maintaining both first and second moment estimates of the gradients [5]. Adam calculates biased estimates of the first moment m_t = β_1 m_{t-1} + (1 - β_1) g_t and second moment v_t = β_2 v_{t-1} + (1 - β_2) g_t², then applies bias correction to these estimates before updating parameters as θ_t = θ_{t-1} - η m̂_t / (√v̂_t + ε) [5]. This combination of momentum and adaptive learning rates has made Adam one of the most widely used optimizers in deep learning applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Gradient-Based Optimization Algorithms

| Algorithm | Key Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Descent | Fixed learning rate for all parameters | Simple implementation; guaranteed convergence for convex functions | Sensitive to learning rate choice; slow convergence in ravines |

| Momentum | Accumulates gradient in velocity vector | Reduces oscillations; accelerates in consistent directions | May overshoot minimum; additional hyperparameter (β) to tune |

| AdaGrad | Learning rate adapted per parameter using sum of squared gradients | Works well with sparse gradients; automatic learning rate tuning | Learning rate decreases overly aggressively during training |

| RMSProp | Exponentially weighted average of squared gradients | Avoids decreasing learning rate of AdaGrad; works well online | Still requires manual learning rate selection |

| Adam | Combines momentum with adaptive learning rates | Generally performs well across diverse problems; bias correction | Can sometimes generalize worse than SGD in some deep learning tasks |

Advanced Adaptive Methods and Recent Innovations

MAMGD: Exponential Decay and Discrete Second-Order Information

The MAMGD optimizer represents a recent innovation that incorporates exponential decay and discrete second-order derivative information to enhance optimization performance. This method utilizes an adaptive learning step, exponential smoothing, gradient accumulation, parameter correction, and discrete analogies from classical mechanics [4]. The exponential decay mechanism allows MAMGD to progressively reduce the influence of past gradients, making it more responsive to recent optimization landscape changes while maintaining stability. The incorporation of discrete second-order information, specifically through the use of a discrete second-order derivative of gradients, provides a better approximation of the local curvature without the computational expense of full second-order methods. Experimental evaluations demonstrate that MAMGD achieves high convergence speed and exhibits stability when dealing with fluctuating gradients and accumulation in gradient accumulators [4]. In comparative studies, MAMGD has shown advantages over established optimizers like SGD, Adagrad, RMSprop, and Adam, particularly when proper hyperparameter selection is performed.

Adam Variants and Control-Theoretic Frameworks

Recent research has formalized the development of adaptive gradient methods through control-theoretic frameworks, leading to more principled optimizer designs and analysis techniques. This framework models adaptive gradient methods in a state-space formulation, which provides simpler convergence proofs for prominent optimizers like AdaGrad, Adam, and AdaBelief [5]. The state-space perspective has also proven constructive for synthesizing new optimizers, as demonstrated by the development of AdamSSM, which incorporates an appropriate pole-zero pair in the transfer function from squared gradients to the second moment estimate [5]. This modification improves the generalization accuracy and convergence speed compared to existing adaptive methods, as validated through image classification with CNN architectures and language modeling with LSTM networks.

Another significant innovation is the Eve algorithm, which enhances Adam by incorporating both locally and globally adaptive learning rates [6]. Eve modifies Adam with a coefficient that captures properties of the objective function, allowing it to adapt learning rates not just per parameter but also globally for all parameters together. Empirical results demonstrate that Eve outperforms Adam and other popular methods in training deep neural networks, including convolutional networks for image classification and recurrent networks for language tasks [6]. These advances highlight the ongoing refinement of adaptive gradient methods through both theoretical analysis and empirical innovation.

Table 2: Advanced Gradient-Based Optimization Algorithms and Their Applications

| Algorithm | Key Innovations | Theoretical Basis | Demonstrated Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAMGD | Exponential decay; discrete second-order derivatives; gradient accumulation | Classical mechanics analogies; adaptive learning steps | Multivariate function minimization; neural network training; image classification |

| AdamSSM | Pole-zero pair in second moment dynamics; state-space framework | Control theory; transfer function design | CNN image classification; LSTM language modeling |

| Eve | Locally and globally adaptive learning rates; objective function properties | Modified Adam framework with additional adaptive coefficient | Deep neural network training; convolutional and recurrent networks |

| σ-zero | Differentiable ℓ₀-norm approximation; adaptive projection operator | Sparse optimization; gradient-based adversarial attacks | Adversarial example generation for model security evaluation |

Specialized Methods for Sparse and Constrained Optimization

The σ-zero algorithm addresses the challenging problem of ℓ₀-norm constrained optimization, which is particularly relevant for generating sparse adversarial examples in security evaluations of machine learning models [7]. Traditional gradient-based methods struggle with ℓ₀-norm constraints due to their non-convex and non-differentiable nature. The σ-zero attack overcomes this limitation through a differentiable approximation of the ℓ₀ norm that enables gradient-based optimization, combined with an adaptive projection operator that dynamically balances loss minimization and perturbation sparsity [7]. Extensive evaluations on MNIST, CIFAR10, and ImageNet datasets demonstrate that σ-zero finds minimum ℓ₀-norm adversarial examples without requiring extensive hyperparameter tuning, outperforming competing sparse attacks in success rate, perturbation size, and efficiency.

For problems involving discrete parameters, recent approaches have leveraged generative deep learning to map discrete parameter sets into continuous latent spaces, enabling gradient-based optimization where it was previously impossible [2]. This method uses a Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Network with Gradient Penalty (WGAN-GP) to create a continuous representation of discrete parameters, allowing standard gradient-based techniques to efficiently explore the design space. When combined with a differentiable surrogate model for non-differentiable physics evaluation functions, this approach has demonstrated significant improvements in computational efficiency and performance compared to global optimization techniques for nanophotonic structure design [2]. While applied in nanophotonics, this framework holds promise for pharmaceutical applications involving discrete decision variables, such as catalyst selection or formulation component choices.

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Drug Development

Surrogate-Based Optimization for Process Systems

The pharmaceutical industry increasingly relies on advanced process modeling to streamline drug development and manufacturing workflows, with surrogate-based optimization emerging as a practical solution for managing computational complexity [3]. This approach creates simplified surrogate models that approximate the behavior of complex systems, enabling efficient optimization while maintaining fidelity to the underlying physics and chemistry. A unified framework for surrogate-based optimization supports both single- and multi-objective versions, allowing researchers to balance competing goals such as yield, purity, and sustainability [3]. Application to an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) manufacturing process demonstrated tangible improvements: single-objective optimization achieved a 1.72% improvement in Yield and a 7.27% improvement in Process Mass Intensity, while multi-objective optimization achieved a 3.63% enhancement in Yield while maintaining high purity levels [3]. Pareto fronts generated through this framework effectively visualize trade-offs between competing objectives, enabling informed decision-making based on quantitative data.

Machine Learning in Drug Discovery

Machine learning approaches that depend heavily on gradient-based optimization have transformed multiple stages of drug discovery and development, offering scalable solutions for high-dimensional problems in cheminformatics and bioinformatics [8]. Gradient boosting machines, including implementations like XGBoost, LightGBM, and CatBoost, have demonstrated particular utility for Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, which links molecular structures encoded as numerical descriptors to experimentally measurable properties [9]. These decision tree ensembles iteratively aggregate predictive models so that each compensates for errors from the previous step, yielding high-performance ensembles through gradient-based optimization of a loss function. In large-scale benchmarking involving 157,590 gradient boosting models evaluated on 16 datasets with 94 endpoints comprising 1.4 million compounds total, XGBoost generally achieved the best predictive performance, while LightGBM required the least training time, especially for larger datasets [9].

Deep learning architectures trained with gradient-based optimization have further expanded capabilities in drug discovery, with applications spanning target validation, identification of prognostic biomarkers, analysis of digital pathology data, bioactivity prediction, de novo molecular design, and synthesis prediction [8]. The success of these approaches depends critically on both the model architecture and the optimization algorithm, with different optimizers yielding varying training efficiencies and final model performances even with fixed network architectures and datasets [4] [8]. The selection of appropriate gradient-based optimization methods therefore represents a crucial consideration in building predictive models for pharmaceutical applications.

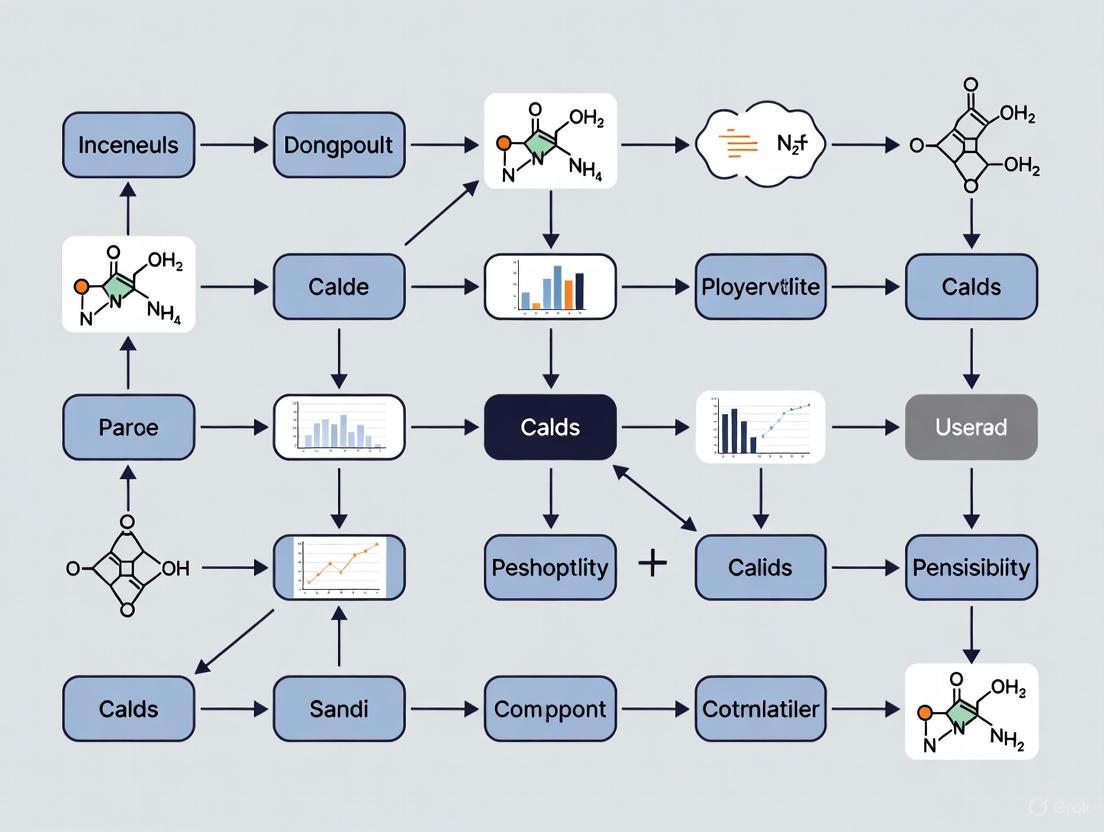

Figure 1: Pharmaceutical Optimization Workflow Integrating Gradient-Based Methods

Experimental Protocols and Implementation Guidelines

Protocol: Benchmarking Gradient-Based Optimizers for QSAR Modeling

Objective: Systematically evaluate and compare the performance of different gradient-based optimization algorithms for training quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models on pharmaceutical datasets.

Materials and Computational Environment:

- Hardware: Compute node with multi-core CPU (≥16 cores), GPU acceleration (NVIDIA V100 or equivalent), and sufficient RAM (≥64 GB) for large chemical datasets

- Software: Python 3.8+ with scientific computing stack (NumPy, SciPy), machine learning libraries (Scikit-learn, XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost), and deep learning frameworks (TensorFlow/PyTorch)

- Chemical informatics: RDKit for molecular descriptor calculation and cheminformatics operations

Procedure:

- Dataset Preparation:

- Curate chemical structures and associated bioactivity measurements from reliable sources (ChEMBL, PubChem)

- Calculate molecular descriptors (200+ dimensions) using RDKit's descriptor calculation module

- Apply standardization: remove duplicates, address imbalance through appropriate sampling techniques, and normalize features

- Partition data using stratified split: 70% training, 15% validation, 15% test set

Optimizer Configuration:

- Implement multiple gradient-based optimizers: SGD, Momentum, AdaGrad, RMSProp, Adam, and advanced variants (AdamSSM, MAMGD if available)

- Initialize with consistent random seeds across all experiments to ensure comparability

- Set common base learning rate (η=0.01) while maintaining algorithm-specific hyperparameters at their recommended defaults

Training Protocol:

- Train each optimizer-model combination with identical initialization and data batches

- Implement early stopping with patience of 50 epochs based on validation loss

- Record training metrics: iteration count, training time, loss convergence, and computational resource utilization

Evaluation Metrics:

- Calculate predictive performance: ROC-AUC, precision-recall AUC, F1 score for classification; R², RMSE for regression

- Assess training efficiency: time to convergence, computational resource requirements

- Evaluate optimization stability: loss trajectory smoothness, sensitivity to hyperparameters

Statistical Analysis:

- Perform repeated runs with different random seeds (n≥5) to account for variability

- Apply appropriate statistical tests (e.g., paired t-tests) to identify significant performance differences

- Generate comprehensive comparison visualizations: learning curves, performance bar charts, computational efficiency plots

Troubleshooting:

- For unstable training: Implement gradient clipping, learning rate scheduling, or switch to more robust optimizers

- For slow convergence: Consider adaptive learning rate methods (Adam, RMSProp) or increase model capacity

- For overfitting: Apply regularization techniques (L1/L2 penalty, dropout) or early stopping

Protocol: Multi-Objective Process Optimization Using Surrogate Models

Objective: Optimize pharmaceutical manufacturing processes using surrogate-based gradient optimization to balance multiple competing objectives (yield, purity, sustainability).

Materials:

- Process simulation software (Aspen Plus, gPROMS, or custom mechanistic models)

- Optimization framework with multi-objective capabilities (PyGMO, Platypus, or custom implementation)

- Data processing tools for feature engineering and sensitivity analysis

Procedure:

- Surrogate Model Development:

- Generate training data by sampling the parameter space of the high-fidelity process model using Latin Hypercube Sampling

- Develop simplified surrogate models (polynomial response surfaces, Gaussian processes, neural networks) that approximate key process outputs

- Validate surrogate fidelity against held-out test data from the high-fidelity model (target R² > 0.9)

Multi-Objective Optimization Formulation:

- Define objective functions: maximize yield, maximize purity, minimize process mass intensity

- Establish constraints: operating ranges, quality specifications, physical realizability

- Set up optimization problem in standard form with explicit bounds and constraints

Gradient-Based Optimization Execution:

- Select appropriate multi-objective optimization algorithm (MGDA, NSGA-II, MOEA/D)

- Configure gradient calculation: finite differences for black-box surrogates, automatic differentiation for differentiable surrogates

- Execute optimization with multiple restarts from different initial conditions to explore Pareto front

Pareto Front Analysis:

- Characterize trade-off surface between competing objectives

- Identify knee points and regions of interest based on decision-maker preferences

- Select promising candidate solutions for verification with high-fidelity model

Sensitivity Analysis:

- Compute local sensitivity metrics (elementary effects, derivative-based measures) at optimal points

- Perform global sensitivity analysis (Sobol indices) to understand parameter importance across the design space

- Identify critical process parameters requiring tight control during implementation

Validation:

- Verify optimal solutions using high-fidelity process models

- Conduct robustness analysis to assess performance under uncertainty

- Implement laboratory or pilot-scale validation for promising candidates

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Gradient-Based Optimization Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Optimization Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization Algorithms | SGD, Adam, RMSProp, MAMGD, AdamSSM | Core optimization engines that update parameters based on gradient information |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Keras | Provide automatic differentiation, gradient computation, and optimizer implementations |

| Chemical Informatics Tools | RDKit, OpenBabel, ChemAxon | Calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints for chemical structures in QSAR |

| Surrogate Modeling Techniques | Gaussian Processes, Neural Networks, Polynomial Chaos Expansions | Create computationally efficient approximations of complex physics-based models |

| Sensitivity Analysis Methods | Active Subspaces, Sobol Indices, Morris Method | Quantify parameter importance and inform dimension reduction |

| Benchmark Datasets | MNIST, CIFAR-10/100, QM9, MoleculeNet | Standardized datasets for algorithm evaluation and comparison |

Integration with Sensitivity Analysis Research

Gradient-based optimization and sensitivity analysis form a symbiotic relationship in computational science and engineering, with each enhancing the capabilities of the other. Sensitivity analysis provides critical insights into which parameters most significantly influence model outputs, enabling more efficient optimization through dimension reduction and informed parameter prioritization [1]. The active subspace method, a prominent gradient-based dimension reduction technique, uses the gradients of a function to determine important input directions along which the function varies most substantially [1]. By identifying these dominant directions, researchers can effectively reduce the dimensionality of the optimization problem, focusing computational resources on the most influential parameters while treating less important parameters as fixed or constrained.

When direct gradient access is unavailable for complex computational models, kernel methods can indirectly estimate the gradient information needed for both optimization and sensitivity analysis [1]. These nonparametric approaches leverage the relationship between function values and parameters across a sampled design space to reconstruct approximate gradients, enabling gradient-based techniques even for black-box functions. The learned input directions from such analyses can significantly improve the predictive performance of local regression models by effectively "undoing" the active subspace transformation and concentrating statistical power where it matters most [1]. This integration is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical applications, where models often combine mechanistic knowledge with data-driven components, and where understanding parameter sensitivity is as important as finding optimal solutions.

Recent advances have extended these concepts to local sensitivity measures that vary across different regions of the input space, capturing the context-dependent importance of parameters in complex, nonlinear systems [1]. These locally important directions can be exploited by Bayesian optimization algorithms to more efficiently navigate high-dimensional design spaces, sequentially focusing on the most promising regions based on acquisition functions that balance exploration and exploitation. This approach is particularly relevant for pharmaceutical development problems where the objective function is expensive to evaluate and traditional gradient-based methods may require too many function evaluations to be practical. By combining global optimization strategies with local gradient information, these hybrid approaches offer powerful solutions to challenging inverse problems in drug formulation, process optimization, and molecular design.

Sensitivity Analysis is a critical tool used to analyze how the different values of a set of independent variables affect a specific dependent variable under certain specific conditions [10]. In the context of gradient-based optimization, it provides a quantitative method for understanding parameter influence on model outcomes, enabling researchers to determine how sensitive a system is to variations in its input parameters [11]. This is particularly valuable for "black box processes" where the output is an opaque function of several inputs [10].

Gradient-based optimization methods rely heavily on design sensitivity analysis, which calculates derivatives of structural responses with respect to the design variables [11]. This sensitivity information forms the foundation for taking analytical tools from simple validation to automated design optimization frameworks [11]. For computational efficiency, two primary approaches exist: the direct method, which requires computations proportional to the number of design variables, and the adjoint variable method, which is more efficient when the number of constraints exceeds the number of design variables [11].

Application Notes: Implementing Sensitivity Analysis

Core Mathematical Principles

In gradient-based optimization, sensitivity analysis computes the gradient of a response quantity g, which is calculated from the displacements as g = qᵀu [11]. The sensitivity (or gradient) of this response with respect to design variable x is:

∂g/∂x = ∂qᵀ/∂x u + qᵀ ∂u/∂x [11]

The adjoint variable method enhances computational efficiency by introducing a vector a, calculated as Ka = q, allowing the constraint derivative to be computed as:

∂g/∂x = ∂qᵀ/∂x u + aᵀ(∂f/∂x - ∂K/∂x u) [11]

This approach requires only a single forward-backward substitution for each retained constraint, rather than for each design variable, significantly reducing computational costs for problems with numerous design variables [11].

Practical Applications in Research Domains

- Engineering Design: Optimizing complex structures like automotive S-rails by minimizing strain energy (compliance) while considering manufacturing constraints [12]. The parametrization of 3D curved beams enables derivative calculation for sensitivity analysis and the use of gradient-based optimizers [12].

- Computational Mechanics: Evaluating vibration reduction in complex variable-stiffness systems using stiffness gradient sensitivity analysis, which establishes relationships between vibration responses and stiffness changes [13].

- Drug Development & Computational Biology: Applying gradient-based optimization of neural networks for tasks such as target localization, molecular recognition, and predictive modeling of biological processes [4].

- Financial Modeling: Performing "what-if" analyses to predict outcomes under varying conditions, such as studying the effect of interest rate changes on bond prices [10].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Direct Method for Sensitivity Analysis

Purpose: To calculate response sensitivities with respect to design variables using the direct method, optimal when the number of design variables is smaller than the number of constraints [11].

Workflow:

- System Analysis: Solve the system equation

Ku = ffor the displacement vectoru[11]. - Differentiate System Equation: Compute the derivative of the system equation with respect to design variable

x:∂K/∂x u + K ∂u/∂x = ∂f/∂x[11]. - Solve for Displacement Sensitivity: Calculate the derivative of the displacement vector by solving:

K ∂u/∂x = ∂f/∂x - ∂K/∂x u[11]. - Compute Response Gradient: Calculate the final response sensitivity using:

∂g/∂x = ∂qᵀ/∂x u + qᵀ ∂u/∂x[11].

Data Interpretation: The resulting gradients ∂g/∂x quantify how much the response g changes for infinitesimal changes in each design variable x, guiding optimization direction.

Protocol 2: Adjoint Variable Method for Sensitivity Analysis

Purpose: To efficiently compute sensitivities when the number of constraints is smaller than the number of design variables [11].

Workflow:

- System Analysis: Solve the primary system equation

Ku = ffor the displacement vectoru[11]. - Adjoint System Solution: Solve the adjoint system

Ka = qfor the adjoint variable vectora[11]. - Compute Response Gradient: Calculate the sensitivity directly using:

∂g/∂x = ∂qᵀ/∂x u + aᵀ(∂f/∂x - ∂K/∂x u)[11].

Data Interpretation: This method avoids explicit computation of ∂u/∂x, significantly reducing computational cost for problems with many design variables and few constraints.

Protocol 3: Excel-Based Financial Sensitivity Analysis

Purpose: To perform "what-if" analysis in financial modeling using Excel's Data Table functionality [14] [15].

Workflow:

- Model Setup: Develop a financial model with clear input assumptions and output variables [15].

- Input Range Definition: Define the range of values for two key input variables to be tested [14].

- Output Reference: In the top-left cell of the sensitivity table, enter a direct link to the output variable being analyzed [15].

- Data Table Creation: Select the entire table range, then use

Data > What-If Analysis > Data Table[14] [15]. - Input Cell Assignment: Specify the row input cell (corresponding to the horizontal variable) and column input cell (corresponding to the vertical variable) [14].

- Result Validation: Check that output values change appropriately with inputs (e.g., valuation increases with growth rate) [15].

Figure 1: Excel Sensitivity Analysis Workflow

Data Presentation and Visualization

Quantitative Data from Engineering Optimization

Table 1: S-Rail Optimization Results with Manufacturing Constraints [12]

| Optimization Case | Initial Strain Energy (J) | Optimized Strain Energy (J) | Initial Mass (kg) | Optimized Mass (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without Manufacturing Constraints | 0.14 | 0.01 | 3.54 | 2.66 |

| With Manufacturing Constraints | 0.14 | 0.02 | 3.54 | 2.91 |

Table 2: Effective Control Bandwidth Ratios in Vibration Systems [13]

| System Type | Mass Ratio | Effective Control Bandwidth Ratio | Stiffness Gradient Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-DOF System | Optimal | Maximum | High |

| 16-DOF System | Random | Exponential Decay Relationship | Multiple Peak Intervals |

| Solid Plate Model | Varied | Validation of Theoretical Results | Corresponds to Sensitive Regions |

Optimization Algorithm Performance Data

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Gradient-Based Optimization Methods [16]

| Optimization Technique | Computational Efficiency | Precision | Sensitivity to Initial Point |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steepest Descent | Moderate | Moderate | High |

| Conjugate Gradient (Fletcher-Reeves) | High | High | Moderate |

| Conjugate Gradient (Polak-Ribiere) | High | High | Moderate |

| Newton-Raphson | Very High | Very High | Low |

| Quasi-Newton (BFGS) | High | High | Moderate |

| Levenberg-Marquardt | High | High | Low |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Gradient-Based Sensitivity Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Technique | Function in Sensitivity Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization Algorithms | Method of Feasible Directions (MFD) [11] | Default for problems with many constraints but fewer design variables |

| Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP) [11] | Handles equality constraints effectively in size and shape optimization | |

| Dual Optimizer (DUAL2) [11] | Efficient for topology optimization with many design variables | |

| Sensitivity Methods | Direct Method [11] | Computes ∂u/∂x directly; optimal when design variables < constraints |

| Adjoint Variable Method [11] | Uses adjoint solution; optimal when constraints < design variables | |

| Software Tools | OptiStruct [11] | Implements iterative local approximation method for structural optimization |

| Excel Data Tables [14] [15] | Performs "what-if" analysis for financial and basic modeling | |

| Parametrization Techniques | Planar Projection for 3D Curves [12] | Describes complex geometries using minimal design variables for derivative calculation |

Figure 2: Sensitivity Analysis in Gradient-Based Optimization Ecosystem

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Move Limit Strategy in Iterative Optimization

Gradient-based optimization uses an iterative procedure known as the local approximation method [11]. To achieve stable convergence, design variable changes during each iteration are limited to a narrow range called move limits [11]. Typical move limits in approximate optimization problems are 20% of the current design variable value, though advanced approximation concepts may allow up to 50% [11]. Small move limits lead to smoother convergence but may require more iterations, while large move limits may cause oscillations between infeasible designs if constraints are calculated inaccurately [11].

Convergence Criteria

Two convergence tests are typically used in sensitivity-driven optimization [11]:

- Regular Convergence: Achieved when change in objective function is less than the objective tolerance and constraint violations are less than 1% for two consecutive iterations [11].

- Soft Convergence: Achieved when there is little or no change in design variables for two consecutive iterations, requiring one less iteration than regular convergence [11].

The BIGOPT algorithm, a gradient-based method consuming less memory, terminates when: ‖∇Φ‖ ≤ ε or 2|Φ(xₖ₊₁) - Φ(xₖ)|/(|Φ(xₖ₊₁)| + |Φ(xₖ)|) ≤ ε or when iteration steps exceed Nₘₐₓ [11].

Feature extraction is a critical step in data analysis and machine learning, transforming raw data into a format suitable for modeling [17]. In scientific fields like drug discovery, high-dimensional data presents significant challenges, including the curse of dimensionality, increased computational complexity, and noise interference [17]. Deep learning architectures, particularly autoencoders and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), have revolutionized this domain by automatically learning hierarchical and semantically meaningful representations from complex data, thereby circumventing the limitations of manual feature engineering [18] [17].

This article details the application of these architectures within a research paradigm focused on gradient-based optimization and sensitivity analysis. We provide structured protocols, quantitative comparisons, and practical toolkits to enable researchers to effectively leverage these powerful feature extraction techniques.

Deep Learning Architectures for Feature Extraction

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

CNNs are specialized neural networks designed for processing grid-like data, such as images. Their architecture is uniquely suited for capturing spatially local patterns through hierarchical feature learning.

- Core Components: CNNs utilize convolutional layers that apply filters to extract local features, pooling layers to downsample feature maps and ensure translational invariance, and fully connected layers for final classification or regression tasks [18]. The strength of CNNs lies in parameter sharing across spatial locations, which drastically reduces the number of parameters compared to fully connected networks and improves generalization [17].

- Chemical Structure as Images: In cheminformatics, molecular structures can be represented as 2D images for CNN-based analysis. This approach has been successfully used to predict MeSH "therapeutic use" classes directly from chemical images, demonstrating that structural information alone can predict drug function with high accuracy [19]. In one study, this method achieved predictive accuracies between 83% and 88%, outperforming models based on drug-induced transcriptomic changes [19].

The following diagram illustrates a typical CNN workflow for processing molecular images.

Autoencoders

Autoencoders are unsupervised neural networks designed to learn efficient, compressed data representations (encodings) by reconstructing their own input.

- Architecture and Principle: An autoencoder consists of an encoder that maps input data to a lower-dimensional latent space, and a decoder that reconstructs the input from this latent representation [20]. The model is trained to minimize the reconstruction loss, such as Mean Squared Error (MSE), between the original input and the reconstructed output [20].

- Dimensionality Reduction and Beyond: Autoencoders excel at non-linear dimensionality reduction, often outperforming linear methods like PCA [21] [20]. The compressed latent representation serves as a set of distilled features for downstream tasks. Advanced variants include Convolutional Autoencoders (CAEs) for image data, Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) for generative modeling, and Physics-Informed Autoencoders (PIAE) that incorporate physical laws into the learning process to ensure interpretability [21] [20].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Dimensionality Reduction Techniques on Sensor Data [21]

| Method | Key Principle | Interpretability | Median Reconstruction Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physics-Informed Autoencoder (PIAE) | Non-linear + Physical constraints | High (e.g., transistor parameters) | ~50% lower than PCA & CM |

| Standard Autoencoder | Non-linear | Low (Abstract features) | Comparable to PIAE |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Linear | Low (Linear combinations) | ~50% higher than PIAE |

| Compact Model (CM) | Heuristic physical equations | High | ~50% higher than PIAE |

Application Notes in Drug Discovery and Sensor Research

The application of autoencoders and CNNs has led to significant advancements in the interpretation of complex biological and chemical data.

CNN and Graph-Based Models in Drug Response Prediction

Representing drug molecules as graph structures allows Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to inherently capture atomic-level interactions. The eXplainable Graph-based Drug response Prediction (XGDP) model represents a significant advancement by using molecular graphs of drugs and gene expression profiles from cancer cell lines to predict drug response [22]. This approach not only enhances prediction accuracy but also uses attribution algorithms like GNNExplainer and Integrated Gradients to interpret the model, thereby identifying salient functional groups in drugs and their interactions with significant genes in cancer cells [22].

Autoencoders for Interpretable Sensor Signal Processing

A key challenge with standard deep learning models is their "black-box" nature. The Physics-Informed Autoencoder (PIAE) addresses this by structuring the latent space to represent physically meaningful parameters [21]. In one application to Carbon Nanotube Field-Effect Transistor (CNT-FET) gas sensors, the PIAE's encoder was trained to output four interpretable transistor parameters: threshold voltage, subthreshold swing, transconductance, and ON-state current [21]. This method achieved a 50% improvement in median root mean square reconstruction error compared to PCA and a compact model, providing both high fidelity and physical interpretability [21].

The workflow for this physics-informed approach is detailed below.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Predicting Drug Response with eXplainable Graph Networks (XGDP)

This protocol outlines the procedure for implementing the XGDP model as described in Scientific Reports [22].

1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Source: Obtain drug response data (IC~50~) from the GDSC database, gene expression data for cancer cell lines from the CCLE, and drug structures via their SMILES strings from PubChem [22].

- Preprocessing: Filter cell lines with both drug response and gene expression data. Convert drug SMILES to molecular graphs using the RDKit library. For gene expression, reduce dimensionality by selecting the 956 landmark genes from the LINCS L1000 project [22].

2. Model Architecture and Training

- Drug Graph Module: Implement a GNN to process the molecular graph. Use novel circular atom features inspired by the Morgan Algorithm (ECFP) as node features and incorporate chemical bond types as edge features [22].

- Cell Line Module: Process the 956-dimensional gene expression vector using a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [22].

- Integration and Prediction: Fuse the latent drug and cell line features using a cross-attention mechanism. Train the combined model to predict IC~50~ values using a regression loss function [22].

3. Model Interpretation and Sensitivity Analysis

- Attribution Analysis: Apply explainability tools such as GNNExplainer and Integrated Gradients to the trained model [22].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Perturb input features (e.g., mask specific atom features in the graph or ablate key genes) and quantify the change in predicted IC~50~. This identifies critical functional groups and gene targets, linking predictions to biological mechanisms [22].

Protocol: Feature Extraction with a Physics-Informed Autoencoder (PIAE) for Sensor Data

This protocol is adapted from the sensor data analysis study [21].

1. Data Preparation

- Source: Collect multidimensional sensor measurement data, such as transistor transfer characteristics (I~D~-V~GS~ curves) from CNT-FET gas sensing experiments [21].

- Preprocessing: Normalize all curves to a consistent voltage range and interpolate to a fixed number of data points (e.g., 100 points) to ensure uniform input dimension [21].

2. PIAE Model Design

- Encoder Network: Design a feedforward or convolutional network that reduces the input to a latent space with the same number of nodes as the desired physically interpretable features (e.g., 4) [21].

- Physics-Informed Loss: Define a composite loss function L~total~ = L~reconstruction~ + λ * L~physics~, where:

- L~reconstruction~ is the standard MSE between input and output.

- L~physics~ is an additional loss term that penalizes deviation between the encoder's outputs and heuristic estimates of the physical parameters (e.g., V~T~, SS). This guides the encoder to learn interpretable features [21].

- Decoder Network: Construct a network that accurately reconstructs the original signal from the four physical parameters [21].

3. Model Evaluation and Application

- Benchmarking: Compare the reconstruction performance of the PIAE against a standard autoencoder, PCA, and a compact model based on heuristic physical equations [21].

- Feature Utilization: Use the four extracted physical parameters from the encoder as robust, denoised, and interpretable features for subsequent regression or classification tasks, such as estimating gas concentration [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Data Tools for Feature Extraction Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit [22] [19] | Cheminformatics Library | Converts SMILES to molecular graphs/images; calculates molecular descriptors. | Generating molecular graph representations and Morgan fingerprints from SMILES strings for model input. |

| PyTorch / TensorFlow [22] [20] | Deep Learning Framework | Provides flexible environment for building and training custom neural network models. | Implementing Graph Neural Network (GNN) layers for drugs and CNN layers for gene expression data. |

| GNNExplainer [22] | Model Interpretation Tool | Explains predictions of GNNs by identifying important subgraphs and node features. | Identifying salient functional groups in a drug molecule that contribute to its predicted efficacy. |

| PubChem [22] [19] | Chemical Database | Source for chemical structures and properties via Compound ID (CID) or SMILES string. | Retrieving canonical molecular structures for drugs in a screening library. |

| GDSC/CCLE [22] | Biological Database | Provides drug sensitivity screens and multi-omics data for cancer cell lines. | Acquiring curated IC~50~ values and corresponding gene expression profiles for model training. |

Challenges of High-Dimensionality and Chaos in Biological Systems

The pursuit of understanding biological systems through computational models faces two fundamental, interconnected challenges: high-dimensionality and chaotic dynamics. Biological systems are inherently high-dimensional, encompassing variables across multiple spatial and temporal scales, from molecular interactions to cellular networks and tissue-level phenomena [23]. Simultaneously, nonlinear interactions within these systems can lead to chaotic behavior, where small perturbations in initial conditions produce dramatically different outcomes, complicating prediction and control [24]. These characteristics present significant obstacles for gradient-based optimization techniques, which are essential for parameter estimation, model fitting, and therapeutic design in systems biology and drug discovery. This article examines these challenges within the context of gradient-based optimization coupled with sensitivity analysis, providing structured protocols and resources to navigate these complexities in biomedical research.

Key Challenges: High-Dimensionality and Chaos

The High-Dimensionality Problem

High-dimensionality in biological systems arises from the vast number of molecular components, cell types, and their interactions that drive function and dysfunction. The "curse of dimensionality" manifests when modeling such systems, as the volume of the parameter space expands exponentially with each additional dimension, making comprehensive sampling and analysis computationally intractable.

- Data Complexity: Modern high-throughput technologies generate massive, multi-type datasets documenting biological variables at multiple scales (subcellular, single cell, bulk, patient) over dynamic time windows and under different experimental conditions [25].

- Parameter Proliferation: Multi-scale models (MSMs) tend to be highly complex with numerous parameters, many of which have unknown or uncertain values, leading to epistemic uncertainty in the system [26].

- Search Space Challenges: In drug discovery, the chemical space is vast and unstructured, making molecular optimization fundamentally challenging [27]. Traditional exploration methods like genetic algorithms rely on random walk exploration, which hinders both solution quality and convergence speed in these high-dimensional spaces [28].

Chaotic Dynamics in Biological Systems

Chaos represents a widespread phenomenon throughout the biological hierarchy, ranging from simple enzyme reactions to ecosystems [24]. The implications of chaotic dynamics for biological function remain complex—in some systems, chaos appears associated with pathological conditions, while in others, pathological states display regular periodic dynamics while healthy systems exhibit chaotic dynamics [29].

- Sensitivity to Initial Conditions: Chaotic systems exhibit exponential divergence from initial conditions, meaning minute differences in starting parameters lead to dramatically different outcomes over time [30]. This behavior directly challenges the stability and reliability of gradient-based optimization.

- Identification Challenges: Distinguishing chaotic behavior from random noise in experimental data requires specialized analytical techniques, as both can appear similarly irregular in time-series data.

- Control Complications: The presence of chaos complicates interventional strategies in therapeutic contexts, as the system response to perturbations becomes inherently difficult to predict.

Table 1: Manifestations of High-Dimensionality and Chaos in Biological Systems

| Biological Scale | High-Dimensionality Manifestation | Chaotic Behavior Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular | Thousands of interacting metabolites and proteins | Metabolic oscillations in peroxidase-catalyzed oxidation reactions [30] |

| Cellular | Complex gene regulatory networks with nonlinear feedback | Period-doubling bifurcations in neuronal electrical activity [24] |

| Physiological | Multi-scale models spanning cellular to tissue levels | Irregular dynamics in periodically stimulated cardiac cells [30] |

| Population | Diverse interacting species in ecosystems | Seasonality and period-doubling bifurcations in epidemic models [30] |

Gradient-Based Optimization Frameworks

Foundations of Gradient-Based Methods

Gradient-based optimization methods utilize information from the objective function's derivatives to efficiently navigate parameter spaces toward optimal solutions. These methods are particularly valuable in biological contexts where experimental validation is costly and time-consuming. The core principle involves iteratively updating parameters in the direction of the steepest ascent (or descent) of the objective function:

x{k+1} = xk + α∇f(x_k)

Where xk represents the parameter vector at iteration k, ∇f(xk) is the gradient of the objective function, and α is the learning rate or step size [11]. In biological applications, these methods must address several unique challenges, including noisy gradients, multiple local optima, and computational constraints.

Addressing High-Dimensionality with Sensitivity Analysis

Global sensitivity analysis provides crucial methodologies for managing high-dimensional parameter spaces in biological models. By quantifying how uncertainty in model outputs can be apportioned to different sources of uncertainty in model inputs, sensitivity analysis enables dimensional reduction and identifies key regulatory parameters [26].

- Sampling Strategies: Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) provides efficient stratification of high-dimensional parameter spaces, offering superior coverage compared to simple random sampling, especially when large samples are computationally infeasible [26].

- Sensitivity Measures: The Partial Rank Correlation Coefficient (PRCC) measures monotonic relationships between parameters and outputs while controlling for other parameters' effects. For non-monotonic relationships, variance-based methods like Sobol sensitivity indices or eFAST are more appropriate [26].

- Surrogate Modeling: To mitigate computational costs, well-trained emulators (neural networks, random forests, Gaussian processes) can predict simulation responses, dramatically reducing the number of full model evaluations required for sensitivity analysis [26].

Table 2: Sensitivity Analysis Methods for High-Dimensional Biological Models

| Method | Applicable Scenarios | Computational Cost | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRCC | Monotonic relationships between parameters and outputs | Moderate | Handles nonlinear monotonic relationships; controls for parameter interactions |

| eFAST | Non-monotonic relationships; oscillatory systems | High | Decomposes output variance; captures interaction effects |

| Sobol Indices | General parameter screening; variance decomposition | High | Comprehensive variance apportionment; model-independent |

| Derivative-based (OAT) | Continuous models with computable gradients | Low to Moderate | Provides local sensitivity landscape; efficient for models with analytical derivatives |

Novel Algorithms for Biological Systems

Recent algorithmic advances address the unique challenges of biological systems:

- Gradient Genetic Algorithm (Gradient GA): This hybrid approach incorporates gradient information into genetic algorithms, replacing random exploration with guided search toward optimal solutions. By learning a differentiable objective function parameterized by a neural network and utilizing the Discrete Langevin Proposal (DLP), Gradient GA enables gradient guidance in discrete molecular spaces [28].

- Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) for Molecular Design: VAEs model the tractable latent space of molecular structures, enabling gradient-based optimization of molecular properties. When combined with property estimators, this approach allows navigation of chemical space toward regions with desired biological activities [27].

Application Notes: Protocol for Multi-Scale Model Optimization

Integrated Sensitivity Analysis and Optimization Workflow

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for model optimization

Protocol: Global Sensitivity Analysis with Gradient-Based Refinement

Objective: Identify influential parameters in a high-dimensional biological model and optimize them using gradient-based methods while accounting for potential chaotic dynamics.

Materials and Reagents:

- Computational models of the biological system (e.g., ODE-based, agent-based, or hybrid multi-scale models)

- High-performance computing resources

- Sensitivity analysis software (e.g., SALib, UQLab, or custom implementations)

- Optimization frameworks (e.g., OptiStruct, SciPy, or custom gradient-based algorithms)

Procedure:

Model Formulation and Parameter Space Definition

- Formulate the mathematical structure of the biological system, typically as a system of ODEs: ẋ(t) = f(x(t), θ) where x(t) represents state variables and θ denotes parameters [25].

- Define plausible ranges for all parameters based on literature review and experimental data.

- Log-transform parameters spanning multiple orders of magnitude to normalize scales.

Global Sensitivity Analysis Using Latin Hypercube Sampling

- Generate parameter samples using LHS to ensure stratification across all parameter dimensions.

- For stochastic models, perform 3-5 replications per parameter set (or use graphical/confidence interval methods to determine optimal replication numbers) [26].

- Run model simulations for all parameter sets and record output variables of interest.

- Calculate Partial Rank Correlation Coefficients (PRCC) between parameters and outputs to identify statistically significant monotonic relationships.

- For non-monotonic relationships, apply variance-based methods (eFAST or Sobol indices).

Parameter Space Reduction

- Rank parameters by their sensitivity indices (PRCC values or Sobol total-order indices).

- Select the most influential parameters (typically 5-15) for optimization, fixing less sensitive parameters at their nominal values.

- Validate that the reduced parameter space retains the essential dynamics of the full model.

Gradient-Based Optimization

- Define an objective function quantifying model agreement with experimental data (e.g., sum of squared errors, likelihood function).

- Implement gradient-based optimization using the Method of Feasible Directions (MFD) for problems with many constraints or Dual Optimizer for problems with many design variables [11].

- Apply move limits (typically 20-50% of current parameter values) to ensure approximation accuracy [11].

- Iterate until convergence criteria are satisfied (minimal change in objective function and constraint violations <1% for two consecutive iterations).

Chaotic Dynamics Assessment

- For the optimized parameter set, perform Lyapunov exponent calculation or recurrence analysis to detect chaotic regimes.

- If chaos is detected, evaluate its biological implications—whether it represents healthy function or pathological dynamics [24] [29].

- For pathological chaos, implement control strategies by slightly adjusting parameters to maintain system function while avoiding chaotic regimes.

Troubleshooting:

- If optimization converges to poor local minima: Implement multiple restarts from different initial parameter values or incorporate global search elements.

- If sensitivity analysis reveals unexpectedly low parameter influence: Re-evaluate parameter ranges, as overly narrow bounds can artificially reduce apparent sensitivity.

- If chaotic behavior prevents meaningful optimization: Consider whether the timescale of interest is appropriate or implement chaos control techniques.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for High-Dimensional Biological Optimization

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity Analysis Libraries | SALib, UQLab, GSUA-CSB | Implement global sensitivity methods (PRCC, eFAST, Sobol) for parameter prioritization |

| Optimization Algorithms | OptiStruct, SciPy, COMSOL | Provide gradient-based optimization (MFD, SQP, MMA) for parameter estimation |

| Surrogate Models | Gaussian Processes, Neural Networks, Random Forests | Create efficient emulators of complex models to reduce computational cost |

| Chaos Analysis Tools | Lyapunov exponent calculators, Recurrence analysis software | Identify and characterize chaotic dynamics in biological systems |

| Multi-Scale Modeling Platforms | CompuCell3D, URDME, VCell | Implement and simulate biological processes across spatial and temporal scales |

The interplay between high-dimensionality and chaotic dynamics presents significant yet navigable challenges in biological systems modeling. Through the strategic integration of global sensitivity analysis for dimensional reduction and sophisticated gradient-based optimization methods, researchers can effectively tackle the complexity of biological systems. The protocols and tools outlined here provide a structured approach to parameter identification, model optimization, and chaos management, enabling more robust and predictive biological models. As these computational methods continue to evolve, particularly through hybrid approaches combining mechanistic modeling with machine learning, they offer promising pathways to advance drug discovery, systems biology, and personalized medicine in the face of biological complexity.

From Theory to Therapy: Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Pharmaceutical Science

Structure-Based Molecule Optimization (SBMO) with Joint Gradient Frameworks like MolJO

Structure-based molecule optimization (SBMO) represents an advanced task in computational drug design, focusing on optimizing three-dimensional molecules against specific protein targets to meet therapeutic criteria. Unlike generative models that primarily maximize data likelihood, SBMO prioritizes targeted enhancement of molecular properties such as binding affinity and synthesizability for existing compounds [31] [32]. The MolJO (Molecule Joint Optimization) framework represents a groundbreaking gradient-based approach to SBMO that leverages Bayesian Flow Networks (BFNs) to operate in a continuous, differentiable parameter space [33] [34]. This framework effectively handles the dual challenges of optimizing both continuous atomic coordinates and discrete atom types within a unified, joint optimization paradigm while preserving SE(3)-equivariance—a crucial property ensuring that molecular behavior remains consistent across rotational and translational transformations [31] [35].

A fundamental innovation within MolJO is its novel "backward correction strategy," which maintains a sliding window of past optimization histories, enabling a flexible trade-off between exploration of chemical space and exploitation of promising molecular candidates [31]. This approach effectively addresses the historical challenges in gradient-based optimization methods, which have struggled with guiding discrete variables and maintaining consistency between molecular modalities [32]. By establishing a mathematically principled framework for joint gradient guidance across continuous and discrete molecular representations, MolJO achieves state-of-the-art performance on standard benchmarks including CrossDocked2020, demonstrating significant improvements over previous gradient-based and evolutionary optimization methods [33] [35].

Core Methodology and Theoretical Foundations

Molecular Representation and Problem Formulation

In the MolJO framework, molecular systems are represented as structured point clouds encompassing both protein binding sites and ligand molecules. A protein binding site is represented as p = (xP, vP), where xP ∈ ℝ^{NP×3} denotes the 3D coordinates of NP_ protein atoms, and vP ∈ ℝ^{NP×KP} represents their corresponding KP-dimensional feature vectors [31] [32]. Similarly, a ligand molecule is represented as m = (xM, vM), where xM_ ∈ ℝ^{NM×3} represents the 3D coordinates of NM_ ligand atoms, and vM ∈ ℝ^{NM×KM} represents their feature vectors encompassing discrete atom types and other chemical characteristics.

The SBMO problem is formally defined as optimizing an initial ligand molecule m^((0))^ to generate an improved molecule m^(*)^ that maximizes a set of objective functions f(θ) while preserving key molecular properties:

m^()^ = arg max_m {_fbind_(m, *p), fdrug(m), fsyn(m)}

where fbind quantifies binding affinity to the protein target, fdrug measures drug-likeness, and fsyn assesses synthetic accessibility [31].

Gradient Guidance in Continuous-Differentiable Space

MolJO addresses the fundamental challenge of applying gradient-based optimization to discrete molecular structures by leveraging a continuous and differentiable space derived through Bayesian inference [33] [31]. This approach transforms the inherently discrete molecular optimization problem into a tractable continuous optimization framework within the BFN paradigm:

- Input Representation: The framework begins with molecular structures represented as distributions over continuous parameters rather than discrete entities.

- Bayesian Flow Process: The optimization follows a Bayesian flow process where molecular parameters are progressively refined through a series of Bayesian updates.

- Gradient Propagation: Gradient signals are computed based on objective functions and propagated backward through the continuous parameter space, enabling simultaneous optimization of both atomic coordinates (continuous) and atom types (discrete) [31] [35].

The mathematical formulation of this process ensures that gradients with respect to both molecular modalities (coordinates and types) are jointly considered, eliminating the modality inconsistencies that plagued previous gradient-based approaches [32].

Backward Correction Strategy

The backward correction strategy introduces a novel optimization mechanism that maintains a sliding window of past optimization states, enabling the framework to "correct" previous optimization steps based on current gradient information [31] [34]. This approach:

- Maintains explicit dependencies on past optimization histories

- Aligns gradient signals across different optimization steps

- Balances exploration of chemical space with exploitation of promising molecular regions

- Provides a flexible mechanism to escape local optima during the search process

The backward correction operates by storing a history of the previous K optimization steps H = {h^((t-K))^, ..., h^((t-1))^} and computing correction terms that refine these historical states based on current gradient information, effectively creating a short-term memory mechanism within the optimization trajectory [31].

Quantitative Performance Evaluation

Benchmark Results on CrossDocked2020

MolJO's performance has been extensively evaluated on the CrossDocked2020 benchmark, demonstrating state-of-the-art results across multiple key metrics as summarized in Table 1 [33] [31] [35].

Table 1: Performance comparison of MolJO against other SBMO methods on the CrossDocked2020 benchmark

| Method | Success Rate (%) | Vina Dock | Synthetic Accessibility (SA) | "Me-Better" Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MolJO | 51.3 | -9.05 | 0.78 | 2.0× |

| Gradient-based counterpart | ~12.8* | N/R | N/R | 1.0× |

| 3D baselines | N/R | N/R | N/R | 1.0× |

*Estimated based on reported 4× improvement [31] N/R = Not explicitly reported in the available search results

The Success Rate metric measures the percentage of successfully optimized molecules that meet all criteria for improvement, while Vina Dock represents the calculated binding affinity (lower values indicate stronger binding). Synthetic Accessibility (SA) ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating more readily synthesizable molecules. The "Me-Better" Ratio quantifies how many times MolJO produces better results compared to baseline methods [33] [31].

Performance Across Optimization Tasks

MolJO demonstrates versatile performance across various molecular optimization scenarios as detailed in Table 2 [33] [34].

Table 2: MolJO performance across different optimization scenarios

| Optimization Scenario | Key Performance Metrics | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-objective Optimization | Balanced improvement across affinity, drug-likeness, and synthesizability | Holistic drug candidate optimization |

| R-group Optimization | Significant improvement in binding affinity while preserving core scaffold | Lead optimization phase |

| Scaffold Hopping | Successful generation of novel scaffolds with maintained or improved binding | Intellectual property expansion, patent bypass |

| Constrained Optimization | High success rate under multiple structural constraints | Focused library design |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Core Optimization Protocol

The standard MolJO optimization protocol follows a structured workflow:

Initialization:

- Input the initial ligand molecule m^((0))^ and protein binding site p

- Initialize the Bayesian flow parameters θ^((0))^

- Set optimization hyperparameters: learning rate η, backward correction window size K, number of optimization steps T

Iterative Optimization:

- For t = 1 to T:

- Compute joint gradient signals ∇θ{fbind, fdrug, fsyn} using the current molecular parameters θ^((t))^

- Apply backward correction to the previous K optimization steps using current gradient information

- Update molecular parameters: θ^((t+1))^ = θ^((t))^ + η · ∇θ{fcombined}

- Check for convergence criteria

- For t = 1 to T:

Termination and Output:

Multi-Objective Optimization Protocol

For multi-objective optimization scenarios, the protocol incorporates additional steps:

Objective Weighting:

- Define relative weights wbind, wdrug, wsyn for different objectives based on optimization priorities

- Normalize objective functions to comparable scales to prevent dominance by any single objective

Pareto-Optimal Search:

- Maintain a population of candidate solutions representing different trade-offs between objectives

- Apply joint gradient guidance with objective-specific correction terms

- Update candidate solutions along the Pareto front using the backward correction strategy [31]

R-Group Optimization and Scaffold Hopping Protocols

Specialized protocols have been developed for key drug design applications:

R-Group Optimization Protocol:

- Identify the molecular core scaffold to be preserved

- Define optimization regions corresponding to R-group positions

- Apply constrained gradient guidance that preserves the core structure while optimizing R-group substitutions

- Use fragment-based sampling within the continuous space to explore diverse R-group possibilities [34]

Scaffold Hopping Protocol:

- Identify key pharmacophore elements from the initial molecule

- Define spatial constraints to maintain critical interactions

- Apply aggressive exploration in the continuous space using enlarged backward correction windows

- Filter generated scaffolds based on novelty and synthetic accessibility [33] [34]

Visualization of Workflows and Signaling Pathways

MolJO Optimization Workflow

Backward Correction Mechanism

Backward Correction Strategy

Multi-Modality Gradient Guidance

Multi-Modality Gradient Guidance

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for SBMO with MolJO

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function in SBMO Research |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Frameworks | MolJO Framework [34] | Core gradient-based optimization engine with backward correction |

| Benchmark Datasets | CrossDocked2020 [33] [31] | Standardized dataset for training and evaluation |

| Evaluation Metrics | Vina Dock, SA Score, Success Rate [33] | Quantitative assessment of optimization performance |

| Molecular Representation | Bayesian Flow Networks [31] [34] | Continuous parameter space for joint gradient guidance |

| 3D Structure Tools | PoseBusters V2 [34] | Validation of generated molecular geometries |

| Protein Preparation | Molecular docking software | Preparation of protein targets and binding sites |

Integration with Sensitivity Analysis in Drug Discovery

The MolJO framework exhibits strong conceptual alignment with sensitivity analysis methodologies employed in drug discovery research. In systems biology, sensitivity analysis identifies model parameters whose modification significantly alters system responses, facilitating the discovery of potential molecular drug targets [36]. Similarly, MolJO's gradient-based optimization identifies molecular features (atomic coordinates and types) whose modification most significantly improves target properties.

This connection is particularly evident in the p53/Mdm2 regulatory module case, where sensitivity analysis identified key parameters whose perturbation would promote apoptosis by elevating p53 levels [36]. MolJO operationalizes this principle by directly optimizing molecular structures to maximize such desired outcomes through gradient-guided modifications. The backward correction strategy in MolJO further enhances this connection by enabling dynamic adjustment of optimization sensitivity across different molecular regions and optimization stages.

The integration of gradient-based optimization with sensitivity analysis principles creates a powerful framework for targeted drug design, where optimization efforts can be focused on molecular features with highest impact on desired properties, potentially accelerating the discovery of effective therapeutic compounds.

Druggable Target Identification using Optimated Stacked Autoencoders (optSAE)

The identification of druggable targets—biological molecules that can be modulated by drugs to treat diseases—represents a critical bottleneck in pharmaceutical development. Traditional computational methods often suffer from inefficiencies, overfitting, and limited scalability when handling complex pharmaceutical datasets [37]. This application note details a novel framework, optSAE + HSAPSO, which integrates a Stacked Autoencoder (SAE) for robust feature extraction with a Hierarchically Self-Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization (HSAPSO) algorithm for adaptive parameter optimization [37]. Framed within advanced gradient-based optimization research, this protocol demonstrates how sensitivity analysis principles can be leveraged to enhance model stability and generalizability, ultimately achieving state-of-the-art performance in druggable target identification.

Key Performance and Comparative Analysis

The optSAE+HSAPSO framework has been rigorously evaluated on curated datasets from DrugBank and Swiss-Prot. The table below summarizes its quantitative performance against other state-of-the-art methods.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Drug-Target Prediction Models

| Model Name | Core Methodology | Reported Accuracy | AUC | AUPR | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| optSAE + HSAPSO [37] | Stacked Autoencoder with Hierarchical PSO | 95.52% | - | - | 0.010 s/sample |

| DDGAE [38] | Dynamic Weighting Residual GCN & Autoencoder | - | 0.9600 | 0.6621 | - |

| DHGT-DTI [39] | Dual-view Heterogeneous Graph (GraphSAGE & Transformer) | - | - | - | - |

| DrugMiner [37] | SVM & Neural Networks | 89.98% | - | - | - |

| XGB-DrugPred [37] | Optimized XGBoost on DrugBank features | 94.86% | - | - | - |

Table 2: Stability and Robustness Metrics of optSAE+HSAPSO

| Metric | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Stability | ± 0.003 | Variation in accuracy across runs [37] |

| Convergence Speed | High | Enhanced by HSAPSO's adaptive parameter tuning [37] |

| Generalization | Consistent | Maintains performance on validation and unseen datasets [37] |

Experimental Protocol: optSAE-HSAPSO Workflow

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for implementing the optSAE-HSAPSO framework for druggable target identification.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Sources: Download drug and target data from public databases.

- Data Compilation: Construct a heterogeneous network integrating drugs, targets, diseases, and side-effects. Represent this network with an adjacency matrix (

A) and a feature matrix (X) [38]. - Normalization: Normalize fused similarity matrices for drugs and targets to preserve rank-order relationships and enhance numerical stability [38].

Model Construction and Hyperparameter Optimization

- optSAE Architecture:

- Design a Stacked Autoencoder with multiple non-linear layers to learn hierarchical latent representations from the input drug-target data [37].

- The encoder reduces dimensionality, and the decoder reconstructs the input.

- HSAPSO Integration:

- Utilize the Hierarchically Self-Adaptive PSO algorithm to optimize SAE hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate, number of layers, units per layer). This replaces traditional gradient-based optimizers like SGD or Adam for the hyperparameter search space [37].

- HSAPSO Parameters: The swarm dynamically balances exploration and exploitation, improving convergence speed and stability in this high-dimensional, non-convex optimization problem [37].

Model Training and Validation

- Training: Train the optSAE model using the features extracted from the heterogeneous network. The loss function typically combines reconstruction loss (from the autoencoder) and a task-specific classification loss.

- Dual Self-Supervised Joint Training (Optional): For enhanced learning, a mechanism integrating the main network (SAE) with an auxiliary model (e.g., a graph convolutional autoencoder) can be implemented to form an end-to-end training pipeline [38].

- Validation: Perform k-fold cross-validation. Use ROC and convergence analysis to validate robustness and generalization capability [37].

Target Identification and Sensitivity Analysis

- Prediction: Use the trained optSAE model to classify and predict novel druggable targets from the learned low-dimensional representations.

- Sensitivity Analysis Framework:

- Adopt a Global Sensitivity Analysis mindset, analogous to frameworks used in energy systems and epidemiology [41] [42].

- Systematically vary key model inputs (e.g., data source weights, hyperparameters initially tuned by HSAPSO) and use Optimal Transport theory or Sobol indices to quantify their influence on the key output—classification accuracy [41] [42].

- This analysis ranks the impact of different input uncertainties, identifying which parameters or data features most critically shape the model's predictions and ensuring the findings are robust to variations [41].

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for optSAE-HSAPSO. The process flows from data collection through model setup and optimization to final analysis and validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential computational and data resources for implementing the described protocol.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Source / Example |

|---|---|---|