Global Optimization in Systems Biology: Methods, Applications, and Tools for Biomedical Research

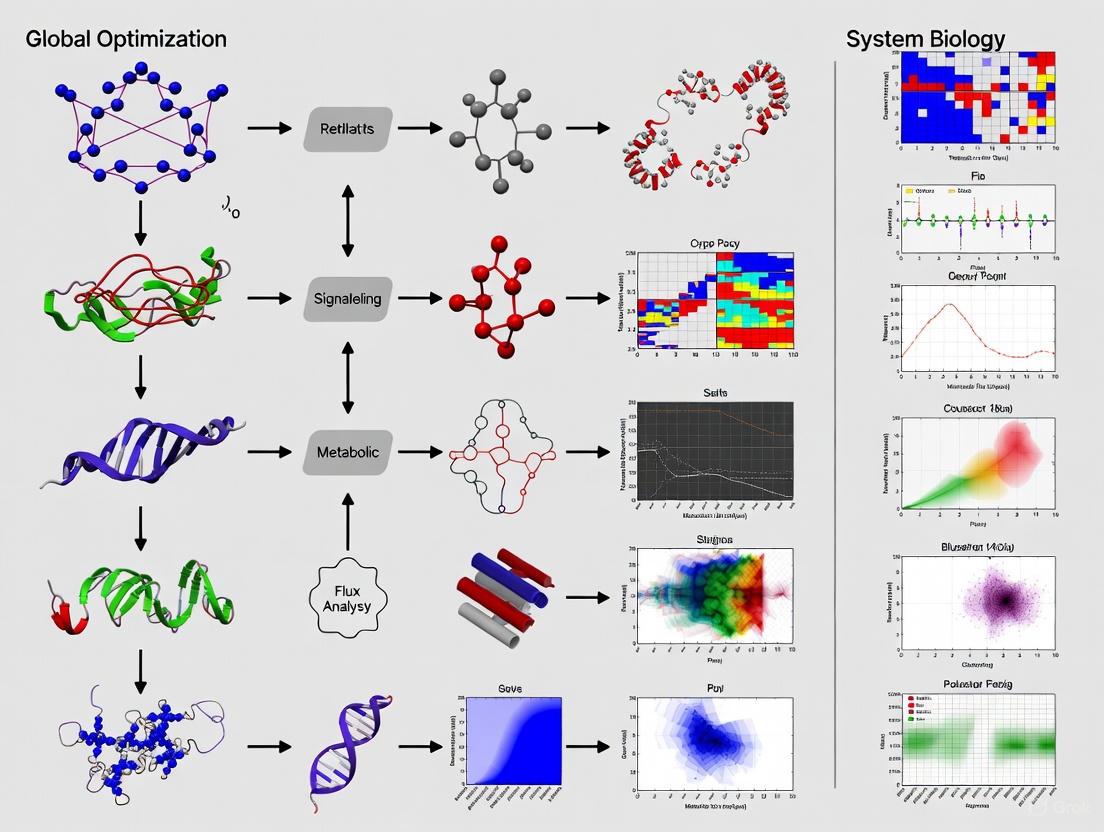

This article provides a comprehensive overview of global optimization, a crucial mathematical framework for solving complex, nonlinear problems in systems biology.

Global Optimization in Systems Biology: Methods, Applications, and Tools for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of global optimization, a crucial mathematical framework for solving complex, nonlinear problems in systems biology. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles distinguishing global from local optimization and the challenges posed by multimodal biological models. The review details deterministic, stochastic, and metaheuristic methods, alongside specialized software tools like MEIGO and AMIGO. It highlights concrete applications in metabolic engineering, drug target identification, and model calibration. Finally, the article offers guidance on method selection, validation, and discusses future perspectives for optimizing biological systems in biomedical and clinical research.

What is Global Optimization and Why is it Critical in Systems Biology?

Mathematical global optimization aims to find the absolute best solution for a given problem within a complex, potentially multi-dimensional search space, a capability that is at the core of many challenges in systems biology [1] [2]. In contrast to local optimization, which may converge to a suboptimal solution close to its starting point, global optimization methods are designed to escape these local minima or maxima and locate the globally optimal solution [2]. This technical guide explores the fundamental principles of global optimization, its critical role in systems biology research—from model identification to metabolic engineering—and provides detailed methodologies for its application, with a specific focus on addressing problems in drug development.

In systems biology, optimization is the underlying hypothesis for model development, a tool for model identification, and a means to compute optimal stimulation procedures to synthetically achieve a desired biological behavior [1]. These problems are typically formulated as Nonlinear Programming Problems (NLPs) with dynamic and algebraic constraints [1]. The presence of nonlinearities in the objective function and constraints often leads to nonconvexity, which results in the potential existence of multiple local solutions, a phenomenon known as multimodality [2].

For visualization, one can imagine the objective function of a multimodal problem with two decision variables as a terrain with multiple peaks and valleys. A local optimization algorithm might find the top of a small hill, while a global optimizer is designed to find the highest mountain in the entire range. The solution of these multimodal problems is the focus of the subfield of global optimization, a class that includes many continuous problems and the vast majority of combinatorial optimization problems [2].

Core Mathematical Principles

The fundamental components of any mathematical optimization problem are:

- Decision Variables: Quantities that can be varied during the search for the best solution (e.g., the amounts of enzymes in a metabolic pathway) [2].

- Objective Function: A performance index that quantifies the quality of a solution defined by a set of decision variables, which can be either maximized or minimized (e.g., the fit between model output and experimental data) [2].

- Constraints: Requirements that must be met, usually expressed as equalities or inequalities (e.g., mass-balance constraints in a metabolic network) [2].

Global optimization problems can be classified based on the nature of their decision variables. Continuous optimization involves variables represented by real numbers, while discrete or combinatorial optimization involves integer numbers [2]. Many challenging problems in systems biology involve a mix of both.

The Challenge of Nonconvexity

A particularly important property is convexity. Convex optimization problems have a unique solution (they are unimodal) and can be solved very efficiently and reliably, even with a very large number of decision variables [2]. However, the nonlinear and highly constrained nature of systems biology models often makes them nonconvex and multimodal [1] [2]. Consequently, locating the global optimum is a daunting task, and specialized efficient and robust optimization techniques are required [1]. Most global optimization problems belong to the class of NP-hard problems, where obtaining global optima with guarantees is often impossible within a reasonable computation time [2].

Methodologies and Algorithmic Approaches

A range of algorithms has been developed to tackle global optimization problems. In many instances, stochastic global optimization methods can locate a near-globally optimal solution in a reasonable time, though they do not offer full guarantees of global optimality [2].

Stochastic and Hybrid Methods

Stochastic methods incorporate an element of randomness to explore the search space broadly and avoid becoming trapped in local optima. Evolutionary computation methods are one class of stochastic methods that have shown good performance in systems biology applications [2].

To enhance efficiency, hybrid methods that combine global and local techniques have shown great potential for difficult problems like parameter estimation [2]. For example, one developed hybrid global optimization method combines evolutionary global search with local descent [3]. A parallel version of such a method can be implemented to enable the solution of large-scale problems in an acceptable time frame [3]. The cooperative enhanced scatter search (eSS) algorithm is another example of a novel global optimization method used in systems biology [1].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of a typical hybrid global optimization algorithm:

A Protocol for Multi-Variable Model Optimization

The following detailed protocol is adapted from a study that performed global optimization of a ventricular myocyte model to multi-variable data [4]. This provides a concrete example of applying global optimization in a pharmacological context.

Objective: To optimize a mathematical model of human ventricular myocyte electrophysiology to better predict the risk of drug-induced arrhythmias, thereby improving drug safety testing.

Background: The baseline model (O'Hara-Rudy - ORd) performs poorly in simulating congenital Long QT (LQT) syndromes, raising concerns about its predictive power for drug-induced LQT and Torsades de Pointes (TdP) risk. Optimization constrains model parameters using clinical data to generate models with higher predictive accuracy [4].

Methodology:

- Define Objective Function: The objective function is formulated to minimize the sum-of-squares error between the model simulation and clinical data. In the simplest case ("APDLQT" optimization), this is based on Action Potential Duration at 90% repolarization (APD90) for control and LQT conditions [4].

- Incorporate Multi-Variable Data: To improve the identifiability of parameters and the physiological relevance of the optimized model, a "multi-variable" optimization is performed. This involves adding terms to the objective function that heavily penalize solutions where intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) and sodium ([Na+]i) concentrations fall outside physiologically plausible bounds [4].

- Set Optimization Bounds: Physiologically-based bounds are placed on the model parameters being optimized to ensure the solution remains biologically realistic.

- Select and Execute Algorithm: A global optimization algorithm, such as a hybrid cooperative enhanced scatter search method, is used to search the high-dimensional parameter space for the set of parameters that minimizes the defined objective function [1] [4].

- Validate Optimized Model: The predictive power of the optimized model is tested against a separate database of known arrhythmogenic and non-arrhythmogenic ion channel blockers. The model's output (e.g., APD50 and diastolic [Ca2+]i) is used to classify drugs' TdP risk, and the classification performance is compared against the baseline model [4].

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cardiac Myocyte Model Optimization

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| O'Hara-Rudy (ORd) Model | A mathematical model of human ventricular myocyte electrophysiology. | Serves as the baseline model to be optimized and validated. [4] |

| Clinical LQT Data | QT interval prolongation data from patients with congenital LQT syndromes (LQT1, LQT2, LQT3). | Provides the primary objective data for the optimization process. [4] |

| Ion Channel Block Data | A curated database of drugs with known effects on cardiac ion channels (IKr, ICaL, INa) and associated TdP risk. | Used for independent validation of the optimized model's predictive power. [4] |

| Global Optimizer (e.g., eSS) | A stochastic global optimization algorithm capable of handling nonlinear, multimodal problems. | Executes the search for parameter values that minimize the objective function. [1] [4] |

Applications in Systems Biology and Drug Development

Global optimization methods are pivotal across numerous domains within systems biology and pharmaceutical research.

Model Identification and Reverse Engineering

The problem of parameter estimation in biochemical pathways is frequently formulated as a nonlinear programming problem subject to the pathway model acting as constraints [2]. Since these problems are often multimodal, global optimization methods are essential to avoid local solutions that can be physiologically misleading [2]. Furthermore, global optimization is used for reverse engineering to infer biomolecular networks, such as transcriptional regulatory networks and signaling pathways, from experimental data [2].

Metabolic Engineering and Synthetic Biology

Metabolic engineering exploits a systems-level approach for optimizing a desired cellular phenotype [2]. Optimization-based methods using genome-scale metabolic models enable the identification of gene knockout strategies for obtaining improved phenotypes. These problems are combinatorial in nature, and their computational time increases exponentially with problem size, creating a clear need for efficient global optimization algorithms [2]. Similarly, in synthetic biology, optimization algorithms are used to search for components and configurations that optimize dynamic behavior according to predefined design objectives [2]. Frameworks like OptCircuit use optimization-based design to aid in the construction and fine-tuning of integrated biological circuits [2].

Drug Safety Pharmacology (The CiPA Initiative)

As highlighted in the protocol, global optimization is central to improving the predictive accuracy of cardiac cell models used in safety pharmacology, such as within the Comprehensive in Vitro Proarrhythmia Assay (CiPA) initiative [4]. By optimizing models to clinical data, researchers can better predict a drug's potential to cause Torsades de Pointes, thereby reducing false-positive outcomes and improving risk assessment during drug development [4].

Table 2: Summary of Global Optimization Applications in Systems Biology

| Application Area | Typical Objective | Nature of Problem | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter Estimation | Calibrate model parameters to fit experimental data. | Frequently multimodal, continuous NLP. | [2] |

| Reverse Engineering | Reconstruct network structures (e.g., gene regulatory networks) from data. | Often combinatorial and multimodal. | [2] |

| Metabolic Engineering | Identify gene knockout strategies to maximize product yield. | Combinatorial (mixed-integer). | [2] |

| Synthetic Biology | Design biological circuits with optimal dynamic behavior. | Mixed continuous-combinatorial. | [2] |

| Drug Safety Testing | Optimize models to improve prediction of cardiotoxicity (TdP risk). | Multimodal, multi-variable constrained NLP. | [4] |

The following diagram illustrates how global optimization integrates into the broader workflow of model-based drug safety assessment:

Global optimization provides an essential mathematical framework for tackling some of the most complex problems in systems biology and drug development. The nonlinear, constrained, and often multimodal nature of these problems—from model calibration to the design of synthetic circuits—demands robust algorithms that can navigate complex landscapes in search of the best solution. While the field has advanced significantly with the development of stochastic and hybrid methods, challenges remain in enhancing the efficiency and robustness of these approaches for large-scale models. The continued refinement of global optimization methodologies promises to further empower researchers and drug development professionals in their quest to build predictive biological models and engineer safer, more effective therapeutic interventions.

Mathematical optimization serves as a cornerstone of computational systems biology, enabling researchers to make sense of complex biological systems by finding the best solutions to well-defined problems subject to predefined constraints [2]. These optimization problems involve decision variables (parameters that can be varied), an objective function (a performance index quantifying solution quality), and constraints (requirements that must be met) [2]. In biological contexts, optimization aims to make systems or designs as effective or functional as possible, mirroring the optimizing processes of evolution that have shaped biological structures and behaviors [2].

The fundamental challenge in systems biology optimization stems from the non-linear and highly constrained nature of biological models, which often results in non-convex optimization landscapes with multiple local solutions (multimodality) [2]. These characteristics make finding globally optimal solutions particularly difficult, especially when dealing with large numbers of decision variables and the stiff dynamics commonly observed in biological systems [5] [2]. The presence of nonlinearities in objective functions and constraints frequently leads to nonconvexity, resulting in the potential existence of multiple local solutions, thus necessitating global optimization approaches that can navigate these complex landscapes effectively [2].

Fundamental Concepts and Mathematical Definitions

Non-linearity in Biological Systems

Non-linearity represents a fundamental characteristic of biological systems where the relationship between system components does not follow a simple proportional pattern. In mathematical terms, a system is non-linear when the output is not directly proportional to the input, and the principle of superposition does not apply. Biological non-linearities manifest in various forms, including:

- Allosteric enzyme regulation: Where enzyme activity displays sigmoidal response curves to substrate concentration

- Cellular signaling cascades: Exhibiting amplification and threshold effects

- Gene regulatory networks: Demonstrating switch-like behaviors and feedback loops

These non-linear relationships result in differential equation models where the rate equations contain higher-order terms or complex functional forms that cannot be expressed as linear combinations of the state variables.

Non-convexity in Optimization Landscapes

Non-convexity refers to the property of an optimization landscape where the feasible space defined by constraints is not convex, meaning that a line segment connecting any two points in the space may pass outside the space [2]. In practical terms, non-convex optimization problems contain multiple "valleys" and "hills" in their objective function surfaces, making it difficult to navigate toward the global optimum. For biological systems, non-convexity arises from:

- Complex reaction kinetics: With Michaelis-Menten, Hill, and other non-linear rate equations

- Multi-stability: Where systems can exist in multiple stable states under identical conditions

- Bifurcations: Where small parameter changes lead to qualitative changes in system behavior

The key implication of non-convexity is that local search methods may become trapped in suboptimal regions of the parameter space, failing to identify the true global solution.

Multimodality in Objective Functions

Multimodality describes the existence of multiple local optima (minima or maxima) in an objective function landscape [2]. In biological optimization, this manifests as multiple distinct parameter sets that locally satisfy optimality conditions but yield different objective function values. The biological significance of multimodality includes:

- Alternative biological mechanisms: Different parameter combinations may represent biologically plausible alternative mechanisms

- Robustness in biological systems: Multiple configurations achieving similar functional outcomes

- Experimental uncertainty: Reflecting the inherent noise and variability in biological measurements

For simple cases with only two decision variables, the objective function of a multimodal problem can be visualized as a terrain with multiple peaks, where local search algorithms may converge to different solutions depending on their starting points [2].

Table 1: Characteristics of Optimization Problem Types in Systems Biology

| Problem Type | Mathematical Properties | Solution Characteristics | Biological Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Programming (LP) | Linear objective function and constraints | Unique global solution, convex feasible space | Metabolic flux balance analysis [2] |

| Non-linear Programming (NLP) | Non-linear objective function and/or constraints | Potential multiple local solutions, non-convex feasible space | Enzyme kinetics parameter estimation [2] |

| Global Optimization | Highly non-linear, non-convex, multimodal | Multiple local optima, difficult to find global solution | Gene network inference, full pathway model calibration [2] |

Origins of Non-linearity and Multimodality

The challenges of non-linearity, non-convexity, and multimodality in biological models stem from several intrinsic properties of biological systems and their mathematical representations. The inherent non-determinism of AI models used in systems biology introduces significant variability, particularly in ensemble learning methods and deep learning architectures where random weight initialization, mini-batch gradient descent, and dropout regularization techniques can lead to different training runs converging to various local minima on the error surface [6]. This non-deterministic behavior arises from various sources inherent in model architecture, training processes, hardware acceleration, or mathematical definitions, creating fundamental challenges for reproducibility and optimization [6].

Data complexity further compounds these challenges through high dimensionality, heterogeneity, and multimodality of biological datasets [6]. Biomedical data often contains diverse types including genomic sequences, imaging, and clinical records, each characterized by high dimensionality and heterogeneity that complicate preprocessing and introduce variability [6]. The multimodal nature of biological data, such as combining MRI scans with gene expression profiles, requires sophisticated preprocessing strategies to ensure compatibility and retain meaningful relationships across data types [6]. Missing data, a frequent issue in clinical studies, exacerbates these difficulties as imputation methods often introduce variability or bias that can skew normalization and downstream analyses [6].

Model complexity represents another significant source of these challenges, referring to the architectural sophistication and computational demands of AI models in systems biology [6]. Complex model architectures with numerous parameters and non-linear activation functions create highly rugged optimization landscapes with multiple local minima, making global optimization particularly challenging, especially with the substantial computational costs required for models tackling NP-hard problems where computational complexity rises exponentially with input size [6].

Implications for Model Calibration and Prediction

The presence of non-linearity, non-convexity, and multimodality has profound implications for biological model calibration and predictive capability. In parameter estimation for biochemical pathways, formulated as nonlinear programming problems subject to pathway model constraints, multimodality means that local solutions can be very misleading when calibrating models [2]. A local solution may indicate a bad fit even for a model that could potentially match experimental data perfectly if the global optimum were found, highlighting the critical need for global optimization methods to avoid these deceptive local solutions [2].

For Universal Differential Equations (UDEs) that combine mechanistic differential equations with artificial neural networks, these challenges manifest in deteriorating performance and convergence with increasing noise levels or decreasing data availability [5]. The flexibility of artificial neural networks increases susceptibility to overfitting, and UDEs need to strike a careful balance between the contributions of the mechanistic and ANN components to maintain interpretability while achieving accurate predictions [5]. The complex interaction between ANN components and mechanistic parameters creates additional optimization challenges, as it remains unclear how the complex ANN influences the inference of mechanistic parameters and the overall interpretability of the UDE model [5].

Table 2: Impact of Data and Model Challenges on Biological Optimization

| Challenge Category | Specific Manifestations | Impact on Optimization | Potential Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Complexity | High dimensionality, heterogeneity, multimodality, missing data, noise [6] | Increases parameter space dimensionality, introduces false minima, complicates gradient calculation | Model unidentifiability, poor generalizability, incorrect biological inferences |

| Model Complexity | Non-linear activation functions, multi-layer architectures, numerous parameters [6] | Creates highly rugged optimization landscapes, increases computational demands | Convergence to suboptimal solutions, excessive computational requirements, overfitting |

| Numerical Challenges | Stiff dynamics, floating-point precision, hardware variations [6] [5] | Introduces numerical instability, affects reproducibility, causes convergence failures | Inconsistent results across computational platforms, failed optimizations, unreliable models |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Global Optimization Frameworks

Addressing the challenges of non-linearity, non-convexity, and multimodality requires sophisticated global optimization approaches. Stochastic global optimization methods have shown significant promise for these problems, including enhanced scatter search and other population-based algorithms [1]. These methods are particularly valuable for model identification in systems biology, where they can handle the nonlinear and highly constrained nature of biological models with large numbers of decision variables [1]. For nonconvex problems, global optimization seeks the globally optimal solution among the set of possible local solutions, navigating complex terrain with multiple peaks that characterize multimodal problems [2].

Hybrid methods that combine global and local techniques have demonstrated substantial potential for difficult problems like parameter estimation in biological systems [2]. These approaches typically employ global exploration in the early stages to identify promising regions of the parameter space, followed by local refinement to converge to precise solutions. The cooperative enhanced scatter search (eSS) framework, along with software tools like AMIGO and DOTcvpSB, have shown excellent performance for global optimization in systems biology applications, particularly for model identification and stimulation design [1].

Universal Differential Equations (UDEs) represent a powerful emerging framework that combines mechanistic differential equations with data-driven artificial neural networks, forming a flexible approach for modeling complex biological systems with partial mechanistic understanding [5]. This hybrid methodology leverages prior knowledge while learning unknown processes from data, but introduces significant optimization challenges due to the need to balance mechanistic and neural network components while avoiding overfitting and maintaining interpretability [5].

Multi-start Optimization Pipeline

A systematic multi-start pipeline represents a robust approach for effective training of complex biological models, addressing the challenges of multimodality through extensive exploration of the parameter space [5]. This pipeline carefully distinguishes between mechanistic parameters (critical for biological interpretability) and ANN parameters (modeling components not well-understood), implementing specific strategies for each [5]. The key components include:

Parameter transformation and regularization: Implementing log-transformation for parameters spanning orders of magnitude while enforcing positive values, with tanh-based transformation for bounded parameter estimation [5]. Weight decay regularization applies L2 penalty to ANN parameters to prevent overcomplexity and maintain balance between mechanistic and data-driven components [5].

Multi-start strategy with hyperparameter sampling: Jointly sampling initial values for both model parameters and hyperparameters including ANN size, activation function, and optimizer learning rate to improve exploration of the hyperparameter space [5]. This approach accounts for the large parameter space and non-convex objective functions that complicate parameter identification.

Advanced numerical schemes and likelihood methods: Leveraging specialized solvers like Tsit5 and KenCarp4 within the SciML framework to handle stiff dynamical systems prevalent in systems biology [5]. Maximum likelihood estimation identifies the maximum likelihood estimate for mechanistic parameters while simultaneously estimating noise parameters of the error model [5].

Figure 1: UDE Multi-start Optimization Workflow

Experimental Protocol for Biological Model Optimization

A robust experimental protocol for addressing non-linearity, non-convexity, and multimodality in biological models involves the following detailed methodological steps:

Problem Formulation and Preprocessing

- Define mechanistic model structure based on biological prior knowledge

- Identify known parameters and components requiring data-driven approximation

- Implement data normalization and preprocessing to handle heterogeneous biological data types

- Address missing data through appropriate imputation strategies

Parameter Transformation and Scaling

- Apply log-transformation for parameters spanning multiple orders of magnitude

- Implement tanh-based transformation for bounded parameter estimation when needed

- Scale input data to improve numerical conditioning of the optimization problem

- Establish parameter bounds based on biological constraints and domain knowledge

Multi-start Optimization Execution

- Sample initial parameter values from defined distributions covering the parameter space

- Jointly sample hyperparameters including ANN architecture and optimizer settings

- Execute global optimization phase to identify promising regions of parameter space

- Apply local refinement to converge to precise solutions from promising starting points

Validation and Regularization

- Implement early stopping based on out-of-sample performance to prevent overfitting

- Apply weight decay regularization to ANN parameters to control complexity

- Validate model performance on independent test datasets

- Assess mechanistic parameter interpretability and biological plausibility

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Systems Biology

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Optimization Software | DOTcvpSB, AMIGO, cooperative enhanced scatter search (eSS) [1] | Solves nonlinear programming problems with dynamic constraints | Model identification, stimulation design in systems biology [1] |

| UDE Frameworks | Julia SciML, Universal Differential Equations [5] | Combines mechanistic ODEs with neural networks | Modeling biological systems with partially unknown dynamics [5] |

| Numerical Solvers | Tsit5, KenCarp4 [5] | Handles stiff differential equations | Solving ODE models with vastly different timescales [5] |

| Parameter Estimation | Maximum likelihood estimation, multi-start algorithms [5] | Identifies model parameters from experimental data | Model calibration with noisy, sparse biological data [5] |

Case Studies and Applications

Glycolysis Pathway Modeling

The application of UDEs to glycolysis modeling demonstrates the practical challenges and solutions for handling non-linearity, non-convexity, and multimodality in biological systems [5]. Glycolysis represents a central metabolic pathway describing ATP and NADH-dependent conversion of glucose to pyruvate, modeled using seven ordinary differential equations exhibiting stable oscillations across twelve free parameters [5]. In this case study, researchers replaced the ATP usage and degradation terms with an artificial neural network that takes all seven state variables as inputs, creating a scenario where the ANN must learn dependency on only one input (ATP species) to recover the true data-generating process [5].

This application highlighted several critical challenges: the stiff dynamics of biological systems requiring specialized numerical solvers, measurement noise following complex distributions necessitating appropriate error models, and limited data availability restricting parameter identifiability [5]. The results demonstrated that model performance and convergence deteriorate significantly with increasing noise levels or decreasing data availability, regardless of ANN size or hyperparameter configurations [5]. However, regularization emerged as a key factor in restoring inference accuracy and model interpretability, with weight decay regularization particularly effective in maintaining balance between mechanistic and data-driven model components [5].

Metabolic Network Optimization

Metabolic engineering represents another significant application area where optimization challenges manifest clearly, exploiting an integrated, systems-level approach for optimizing desired cellular properties or phenotypes [2]. Constraint-based analysis coupled with optimization has created a consistent framework for generating and testing hypotheses about functions of microbial cells using genome-scale models [2]. Optimization-based methods using these genome-scale metabolic models enable identification of gene knockout strategies for obtaining improved phenotypes, though these problems have a combinatorial nature where computational time increases exponentially with problem size [2].

Flux balance methodology provides a guide to metabolic engineering and bioprocess optimization by calculating optimal flux distributions using linear optimization to represent metabolic phenotypes under specific conditions [2]. This approach has generated notable success stories including in silico predictions of Escherichia coli metabolic capabilities and genome-scale reconstruction of Saccharomyces cerevisiae metabolic networks [2]. However, these applications also reveal fundamental questions about optimality principles in biological systems, particularly which criteria (objective functions) are optimized in metabolic networks—a question addressed through concepts of constrained evolutionary optimization and cybernetic models [2].

Figure 2: Unimodal vs Multimodal Optimization Landscapes

The challenges of non-linearity, non-convexity, and multimodality in biological models continue to drive methodological innovations in computational systems biology. Future research directions should focus on enhancing the efficiency and robustness of global optimization approaches to make them applicable to large-scale models, with particular emphasis on hybrid methods combining global and local techniques [2]. The development of computer-aided design tools for biological engineering represents another promising direction, where optimization algorithms could guide the improvement of biological system behavior by searching for optimal components and configurations according to predefined design objectives [2].

The stochastic nature inherent in biomolecular systems necessitates advances in optimization methods capable of handling this uncertainty, with early approaches already emerging for parameter estimation in stochastic biochemical reactions and optimization of stochastic gene network models [2]. As systems biology continues to evolve, optimization methods will likely play an increasingly important role in synthetic biology applications, particularly in the rational redesign and directed evolution of novel in vitro metabolic pathways where optimization serves as the key component [2].

In conclusion, addressing the challenges of non-linearity, non-convexity, and multimodality requires a multifaceted approach combining sophisticated global optimization algorithms, appropriate regularization strategies, and careful balancing of mechanistic and data-driven model components. The continuing development of frameworks like Universal Differential Equations, coupled with advances in numerical methods and computational resources, promises to enhance our ability to extract meaningful biological insights from complex, noisy data despite these fundamental challenges. As optimization methodologies mature, they will increasingly enable the predictive understanding and engineering of biological systems that represents the ultimate goal of systems biology research.

Global optimization provides a essential mathematical foundation for systems biology, enabling researchers to move from qualitative descriptions of biological systems to quantitative and predictive models. In the context of systems biology research, global optimization encompasses computational methods designed to find the best possible solution for complex biological problems where the objective function is often non-convex, multi-modal, or presented as a black-box with computationally expensive evaluations [7]. These methods systematically explore entire parameter spaces to identify global minima, overcoming the limitations of local optimization that often converge to suboptimal solutions trapped in local minima [8] [7]. The core challenge in systems biology—translating nonlinear, high-dimensional biological systems into predictive mathematical models—makes global optimization not merely useful but indispensable for extracting meaningful insights from complex data.

The applications of global optimization span multiple domains within systems biology, creating a cohesive framework for biological discovery and engineering. This technical guide explores three foundational applications: parameter identification for mathematical models of biological networks, metabolic engineering for the design of cell factories, and optimal experimental design for maximizing information gain from costly biological experiments. Together, these applications form an iterative cycle where models inform experiments, experimental data refine models, and optimization algorithms drive both processes toward desired biological objectives.

Model Identification and Parameter Estimation

Model identification involves determining the unknown parameters of mathematical models that best explain experimental data, a process fundamental to creating predictive biological models.

Formulating the Parameter Estimation Problem

Parameter estimation begins with a mathematical model representing biological system dynamics, typically expressed as ordinary differential equations (ODEs): ẋ(t) = f(x, p, u), where x represents biological quantities such as molecular concentrations, p denotes the unknown model parameters to be estimated, and u represents experimental perturbations [9]. The estimation process minimizes an objective function that quantifies the discrepancy between model predictions and experimental data [8] [10]. For quantitative data, this typically takes the form of a weighted residual sum of squares: fquant(x) = Σj (yj,model(x) - yj,data)^2 [11]. Parameter identification thus becomes an optimization problem: finding the parameter vector x that minimizes f_quant(x) [8].

Methodologies and Algorithms

Multiple algorithmic approaches exist for solving parameter estimation problems, each with distinct strengths and computational trade-offs:

Table 1: Optimization Methods for Parameter Estimation

| Method Class | Examples | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient-based | Levenberg-Marquardt, L-BFGS-B [8] | Uses first/second derivatives to navigate parameter space | Fast convergence; efficient for smooth objectives | May converge to local minima; requires gradient computation |

| Metaheuristic | Differential Evolution, Scatter Search [11] [8] | Population-based search without gradient information | Better global search properties; handles non-smooth functions | Computationally expensive; no convergence guarantees |

| Hybrid | Globally-biased BIRECT, DIRECT variants [7] | Combines global search with local refinement | Balances exploration/exploitation; handles expensive evaluations | Implementation complexity; parameter tuning |

For biological models with potential multi-modal objective functions, metaheuristic approaches are often preferred for their ability to escape local minima [8]. The DIRECT algorithm and its variants are particularly valuable as they deterministically partition the search space and balance global exploration with local intensification without requiring extensive parameter tuning [7].

Incorporating Qualitative Data

A significant advancement in parameter identification is the integration of qualitative data through constrained optimization frameworks [11]. Qualitative observations (e.g., "protein A activates protein B" or "mutant strain is inviable") can be formalized as inequality constraints on model outputs: gi(x) < 0. These are incorporated into a composite objective function: ftot(x) = fquant(x) + fqual(x), where fqual(x) = Σi Ci · max(0, gi(x)) imposes penalties for constraint violations [11]. This approach dramatically expands the types of biological data usable for model parameterization, particularly when quantitative time-course data are limited.

Figure 1: Parameter Identification Workflow: This diagram illustrates the iterative process of model parameter estimation, combining experimental data with mathematical models through optimization algorithms.

Metabolic Engineering Applications

Metabolic engineering applies optimization principles to redesign metabolic networks for improved production of valuable chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and biofuels.

Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) represent the comprehensive biochemical network of an organism, encompassing thousands of metabolic reactions catalyzed by enzymes encoded in its genome [12]. The development of GEMs was pioneered for bacteria by Palsson's group and for eukaryotic cells (S. cerevisiae) by Nielsen's group [12]. These models enable in silico prediction of metabolic fluxes under different genetic and environmental conditions through constraint-based optimization approaches. GEMs have become indispensable tools for predicting how genetic modifications alter metabolic fluxes and identifying engineering targets for improved product synthesis [12].

Flux Balance Analysis and Optimization

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a constrained optimization approach that predicts metabolic flux distributions by assuming the network is at steady state [12]. The core mathematical formulation solves: maximize c^T v subject to S·v = 0 and vmin ≤ v ≤ vmax, where S is the stoichiometric matrix, v is the flux vector, and c is a vector defining the biological objective (typically biomass formation or product synthesis) [12]. FBA and related constraint-based methods enable prediction of optimal metabolic flux distributions for maximizing target metabolite production, guiding genetic engineering strategies.

Case Study: Optimal Metabolic Network Identification (OMNI)

The OMNI (Optimal Metabolic Network Identification) method demonstrates the application of optimization to metabolic network refinement [13]. OMNI identifies the set of active reactions in a genome-scale metabolic network that results in the best agreement between in silico predicted and experimentally measured flux distributions [13]. When applied to Escherichia coli mutant strains with lower-than-predicted growth rates, OMNI identified reactions acting as flux bottlenecks, whose corresponding genes were often downregulated in evolved strains [13]. For industrial strains, OMNI can suggest metabolic engineering strategies to improve byproduct secretion by identifying suboptimal flux distributions [13].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Metabolic Engineering

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Databases | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) [12] | Repository of metabolic pathways and enzyme information |

| Modeling Software | COBRA Toolbox [12] | MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based reconstruction and analysis |

| Host Organisms | Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae [12] | Common chassis for metabolic engineering and heterologous expression |

| Experimental Data | Fluxomics, Metabolomics [10] | Quantitative measurements for model validation and refinement |

Optimal Experimental Design

Optimal experimental design (OED) applies optimization principles to design maximally informative experiments within practical constraints, crucial for reducing the time and resources needed for biological discovery.

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Formulation

OED addresses the challenge that not all experimental data equally support dynamic modeling, especially with nonlinear models common in systems biology [14]. The goal is to identify experimental conditions (e.g., measurement timepoints, observed species, perturbation types) that maximize information gain about model parameters or discriminate between competing models [14] [9]. In mathematical terms, OED seeks experimental designs ξ that optimize a criterion Ψ(ξ) based on the Fisher Information Matrix or profile likelihoods [9]. For biological systems where prior parameter knowledge is sparse, frequentist approaches based on profile likelihood have advantages over Bayesian methods that require specified prior distributions [9].

Methodological Approaches

Profile Likelihood-Based Experimental Design

The two-dimensional profile likelihood approach provides a powerful framework for OED in nonlinear systems [9]. This method quantifies the expected uncertainty of a targeted parameter after a potential measurement by constructing a two-dimensional likelihood profile that accounts for different possible measurement outcomes [9]. The range of reasonable measurement outcomes before the experiment is quantified using validation profiles, enabling prediction of how different experimental results would affect parameter uncertainty [9]. This approach yields a design criterion representing the expected average width of the confidence interval after measuring data for a specific experimental condition.

The AMIGO2 Toolbox

The AMIGO2 (Advanced Model Identification using Global Optimization) toolbox implements a practical procedure for computing optimal experiments in systems and synthetic biology [14]. This software tool supports model-based OED to either identify the best model among candidates or improve the identifiability of unknown parameters [14]. AMIGO2 is particularly valuable for designing experiments that enhance practical identifiability—the ability to uniquely determine parameters from available data—addressing a common challenge in biological modeling where parameters may be structurally identifiable in principle but not in practice given experimental limitations [14].

Figure 2: Optimal Experimental Design Workflow: This diagram illustrates the sequential process of designing experiments to maximize information gain for model parameterization, highlighting the iterative nature of the approach.

Applications in Biological Systems

OED has been successfully applied across biological domains, from immunoreceptor signaling to metabolic network characterization. In signaling networks, OED helps determine which signaling nodes and timepoints to measure for robust parameter estimation of often large, non-identifiable systems [8]. In metabolism, OED guides flux measurement strategies to resolve network ambiguities with minimal experimental effort [10]. The sequential nature of OED—where data from initial experiments inform the design of subsequent ones—makes it particularly valuable for resource-constrained biological research [9].

Integrated Workflow and Future Directions

The three application domains—model identification, metabolic engineering, and optimal experimental design—form an integrated workflow in modern systems biology. Metabolic models identify engineering targets, engineered strains generate experimental data, optimal design maximizes information from experiments, and parameter estimation refines models to complete the cycle. Future developments will likely enhance this integration through artificial intelligence (AI)-based models [12] and improved uncertainty quantification methods [8] that better characterize parameter identifiability and model prediction reliability.

The continued advancement of global optimization methodologies remains essential for addressing the increasing complexity of biological models and the growing volume of experimental data. As systems biology progresses toward whole-cell models and digital twins [15], optimization algorithms that efficiently handle high-dimensional parameter spaces, multi-modal objective functions, and hybrid discrete-continuous decision variables will become increasingly critical for translating biological knowledge into predictive models and engineered biological systems.

In systems biology, many critical problems are fundamentally multimodal; they possess not one, but multiple distinct solutions in the decision space. These solutions represent different parameter sets or model structures that can explain the same biological observation. When facing such complexity, traditional local optimization methods, which converge to the nearest optimum from a single starting point, are destined to fail. They become trapped in suboptimal regions, providing an incomplete and often misleading picture of the biological system under study. This limitation is particularly consequential in fields like drug discovery and intracellular signaling analysis, where overlooking alternative solutions can mean the difference between a successful therapeutic and a failed experiment.

The challenge extends beyond merely finding multiple solutions. It requires simultaneously considering the accuracy and diversity of these solutions. If an algorithm focuses solely on accuracy, it will likely fall into a single solution, failing to capture the full scope of biological possibilities. Conversely, if it overemphasizes diversity, it may fail to obtain satisfying accuracy for any solution. This delicate trade-off underscores why specialized global optimization strategies are not merely beneficial but essential for robust systems biology research.

The Fundamental Challenge of Multimodality

Defining Multimodal Optimization Problems

A Multimodal Optimization Problem (MMOP) refers to the problem of having more than one optima or satisfactory solution in the decision space [16]. Unlike single-objective optimization, multimodal optimization aims to locate all or most of these multiple solutions—which have the same or similar fitness value but different solution structures—in a single search and maintain these solutions throughout the entire search process [16].

In biological terms, this multimodality manifests when different molecular structures, network architectures, or parameter sets produce functionally equivalent phenotypes. For instance, multiple protein configurations might achieve similar binding affinity, or different metabolic pathway fluxes might yield equivalent biomass production. The core challenge lies in the fitness landscape—the mathematical representation of how solutions map to performance metrics. Multimodal landscapes contain multiple peaks (local and global optima) separated by valleys of poorer performance, creating a complex terrain that confounds simple gradient-based search methods.

Pitfalls of Local Optimization Methods

Local optimization techniques, such as gradient descent and quasi-Newton methods, operate on a fundamental principle: they iteratively move toward better solutions in the immediate neighborhood of the current point. This approach suffers from critical limitations in biological contexts:

- Premature Convergence: Local methods become trapped in the first local optimum they encounter, regardless of its quality relative to other solutions. In practice, this means a model might be calibrated to one possible parameter set while potentially superior alternatives remain undiscovered [1].

- Incomplete Solution Space Exploration: By converging to a single solution, local methods provide a fragmented understanding of the biological system. They cannot reveal the full repertoire of parameter combinations or network designs that achieve similar functional outcomes [16].

- Sensitivity to Initial Conditions: The solution obtained depends entirely on the starting point chosen for the optimization, making results irreproducible and highly variable.

- Inability to Capture Biological Redundancy: Biological systems often evolve redundant mechanisms to ensure robustness. Local optimization cannot uncover this inherent redundancy, leading to biologically implausible or incomplete models.

Table 1: Comparison of Local vs. Global Optimization Characteristics in Biological Contexts

| Characteristic | Local Optimization | Global Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Solution Diversity | Single solution | Multiple solutions |

| Fitness Landscape Navigation | Follows local gradients | Explores diverse regions |

| Biological Redundancy Capture | Limited | Comprehensive |

| Computational Cost | Lower per run | Higher overall |

| Risk of Premature Convergence | High | Low |

| Applicability to Multimodal Problems | Poor | Excellent |

Global Optimization Methodologies for Biological Systems

Swarm Intelligence and Evolutionary Algorithms

Swarm intelligence algorithms have demonstrated particular effectiveness for solving MMOPs due to their inherent population-based approach, which maintains diversity across multiple potential solutions simultaneously [16]. These methods are particularly well-suited for the nonlinear, high-dimensional parameter spaces common in biological models.

The Brain Storm Optimization (BSO) algorithm incorporates a clustering strategy to group solutions during the search process, effectively mapping the landscape of possible solutions [16]. Its variant, knowledge-driven BSO in objective space (KBSOOS), enhances performance by leveraging information from previous solutions to guide future search, demonstrating significantly improved capability in maintaining solution diversity while ensuring accuracy [16].

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) have proven superior for problems with numerous free parameters. In one geophysical inverse problem with 30 free parameters, genetic algorithms still yielded accurate solutions where simulated annealing became only marginally useful [17]. This performance advantage may reflect "the nonproximate search methods used by them or, possibly, the more complex and capacious memory available to a genetic algorithm for storing its accumulated experience" [17].

Bayesian Multimodel Inference (MMI)

Bayesian MMI has emerged as a powerful approach for addressing model uncertainty in systems biology. Rather than selecting a single "best" model, MMI combines predictions from multiple models to increase certainty in systems biology predictions [18]. This approach becomes particularly relevant when leveraging a set of potentially incomplete models of the same biological pathway.

The Bayesian MMI workflow involves:

- Calibrating available models to training data using Bayesian parameter estimation

- Combining the resulting predictive probability densities using MMI

- Generating improved multimodel predictions of important biological quantities

Mathematically, Bayesian MMI constructs predictors through a linear combination of predictive densities from each model:

$${{{\rm{p}}}}(q| {{{d}}}{{{{\rm{train}}}}},{{\mathfrak{M}}}{K}): !!={\sum }{k=1}^{K}{w}{k}{{{\rm{p}}}}({q}{k}| {{{{\mathcal{M}}}}}{k},{{d}}_{{{{\rm{train}}}}})$$

where weights wk ≥ 0 and ${\sum }{k}^{K}{w}{k}=1$ [18]. This approach has been successfully applied to ERK signaling pathways, demonstrating increased predictive certainty and robustness to model set changes and data uncertainties [18].

Hybrid and Enhanced Strategies

Given the computational demands of biological models, hybrid optimization strategies that combine global and local methods have shown particular promise. These methods use global exploration to identify promising regions of the solution space, then employ local refinement to fine-tune solutions, offering a balance between thorough exploration and computational efficiency [19] [1].

The control vector parameterization (CVP) framework transforms dynamic optimization problems into nonlinear programming problems by parameterizing control variables [20]. This approach, implemented in toolboxes like DOTcvpSB, enables the solution of complex dynamic optimization problems relevant to biological systems, including optimal control for modifying self-organized dynamics and computational design of biological circuits [20].

Table 2: Global Optimization Methods and Their Applications in Systems Biology

| Method Class | Specific Algorithms | Strengths | Biological Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Swarm Intelligence | Brain Storm Optimization (BSO), Particle Swarm Optimization | Maintains solution diversity, handles high dimensions | Nonlinear equation systems, network inference |

| Evolutionary Algorithms | Genetic Algorithms, Differential Evolution | Robust to local optima, handles integer variables | Geophysical inversion, parameter estimation |

| Bayesian Methods | Bayesian Multimodel Inference, Bayesian Model Averaging | Quantifies uncertainty, combines model structures | ERK signaling pathway analysis, prediction |

| Hybrid Methods | Enhanced Scatter Search, CVP with global-local | Balances exploration and exploitation | Dynamic optimization of distributed biological systems |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Diversity Measurement and Performance Metrics

Evaluating multimodal optimization requires specialized metrics that account for both solution quality and diversity. Traditional performance metrics like optima ratio (OR) and success rate (SR) have limitations because they do not adequately consider the diversity of solutions [16].

A recently proposed diversity indicator addresses this gap by providing a quantitative measurement of solution distribution for solving MMOPs [16]. This indicator extends the understanding of an algorithm's search capability on MMOPs by measuring how well solutions cover the different possible optima, not just whether optima were found. The diversity measure is particularly valuable when an algorithm obtains most but not all possible solutions, providing a more nuanced assessment of performance than binary success/failure metrics [16].

Knowledge-Driven Algorithm Design

Incorporating domain knowledge significantly enhances optimization performance for biological problems. The "No free lunch" theory implies that better algorithms can be designed by embedding problem-specific information into the search process [16]. This approach transforms black-box optimization into gray-box optimization, where partial information from problems guides the search strategy.

Knowledge-driven BSOOS algorithms combine knowledge obtained from both the type of solved problem and the properties of the algorithm itself [16]. In practice, this means leveraging understanding of biological network structures, known parameter constraints, and prior distribution information to focus computational resources on biologically plausible solutions.

Workflow for Multimodal Biological Optimization

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for applying global optimization methods to multimodal biological problems:

Multimodal Optimization Workflow in Systems Biology - This diagram outlines the comprehensive process from problem formulation to biological interpretation, highlighting the iterative nature of global optimization in biological contexts.

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Multimodal Optimization in Systems Biology

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOTcvpSB | Software Toolbox | Solves continuous and mixed-integer dynamic optimization problems | Bioreactor optimization, optimal drug infusion, oscillation minimization [20] |

| KBSOOS | Algorithm | Knowledge-driven multimodal optimization | Solving nonlinear equation systems, maintaining solution diversity [16] |

| Bayesian MMI | Statistical Framework | Combines predictions from multiple models | ERK signaling pathway analysis, uncertainty quantification [18] |

| Proper Orthogonal Decomposition | Model Reduction | Reduces computational complexity of distributed models | Dynamic optimization of spatially distributed biological systems [19] |

| SUNDIALS | Numerical Solver Suite | Solves differential equations and sensitivity analysis | Inner iteration in control vector parameterization [20] |

Case Studies in Biological Systems

Intracellular Signaling Pathways: ERK Signaling

The extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling cascade presents a classic example where multimodal optimization is essential. Searching the BioModels database yields over 125 ordinary differential equation models for ERK signaling [18]. Each model was developed with different simplifying assumptions and formulations, yet multiple models can represent the same pathway.

Bayesian multimodel inference has been successfully applied to ERK pathway models, combining predictions from ten different model structures to increase predictive certainty [18]. This approach enabled researchers to identify possible mechanisms of experimentally measured subcellular location-specific ERK activity, suggesting that "location-specific differences in both Rap1 activation and negative feedback strength are necessary to capture the observed dynamics" [18].

The following diagram illustrates the multimodel inference process for ERK signaling analysis:

Multimodel Inference for ERK Signaling - This diagram shows how multiple ERK pathway models are combined through Bayesian multimodel inference to generate robust predictions of subcellular ERK activity.

Spatial Biological Systems: Bacterial Chemotaxis and Pattern Formation

Spatially distributed biological systems present particularly challenging optimization problems due to their inherent complexity. The dynamic optimization of such systems has been addressed using hybrid global optimization methods combined with reduced order models [19].

In bacterial chemotaxis, researchers computed "the time-varying optimal concentration of chemotractant in one of the spatial boundaries in order to achieve predefined cell distribution profiles" [19]. Similarly, the FitzHugh-Nagumo model, which describes physiological processes like heart behavior, was optimized to force "a system to evolve from an undesired to a desired pattern with a reduced number of actuators" [19].

These applications demonstrate how global optimization methods enable not just analysis but active design of biological behaviors in spatially complex systems—a capability far beyond the reach of local optimization techniques.

Drug Discovery: Multimodal AI Approaches

In drug discovery, the multimodal challenge extends beyond parameter optimization to integrating diverse data types. The KEDD framework exemplifies this approach, simultaneously incorporating "molecular structures, structured knowledge from knowledge graphs, and unstructured knowledge from biomedical literature" [21]. This multimodal understanding of biomolecules has led to performance improvements of 5.2% on drug-target interaction prediction and 2.6% on drug property prediction compared to state-of-the-art models [21].

Multimodal AI approaches address the critical "missing modality problem" where complete multimodal information is unavailable for novel drugs and proteins [21]. By leveraging sparse attention and modality masking techniques, these frameworks can reconstruct missing features based on relevant molecules, maintaining predictive capability even with incomplete data.

The multimodal nature of biological systems demands a correspondingly sophisticated approach to optimization. Local methods, while computationally efficient, fundamentally cannot capture the complex solution landscapes of biological models. Global optimization methods—from swarm intelligence and evolutionary algorithms to Bayesian multimodel inference—provide the necessary framework to address this complexity, offering more complete, robust, and biologically plausible solutions.

As systems biology continues to tackle increasingly complex questions, the importance of global multimodal optimization will only grow. Future directions point toward more tightly integrated multimodal AI frameworks, enhanced scalability for high-dimensional problems, and more sophisticated uncertainty quantification methods. For researchers in systems biology and drug development, embracing these global optimization approaches is not merely an technical choice but a fundamental requirement for generating meaningful biological insights.

The transition from local to global optimization methods represents more than just a shift in algorithms—it embodies a fundamental evolution in how we conceptualize and address biological complexity. By acknowledging and embracing multimodality, systems biologists can move beyond simplified single-solution models toward a more comprehensive understanding that captures the true richness and redundancy of biological systems.

A Toolkit of Global Optimization Methods and Their Biological Applications

Within the domain of global optimization in systems biology research, the imperative to find globally optimal parameter sets for nonlinear dynamic models demands rigorous, deterministic algorithms. This technical guide elucidates two cornerstone methodologies: the Branch-and-Bound (B&B) framework and Cutting-Plane methods. These strategies provide deterministic guarantees of convergence to a global optimum within a specified tolerance, a critical requirement for robust parameter estimation and model calibration in biological systems [22]. We detail their algorithmic foundations, integration into spatial Branch-and-Bound (sBB) and outer approximation schemes for mixed-integer nonlinear programming (MINLP) problems, and provide explicit experimental protocols for their application in dynamic biological models. The discussion is framed within the practical challenges of systems biology, where nonconvexities and multimodality are prevalent.

Mathematical modeling of biological systems, often described by sets of nonlinear ordinary differential equations (ODEs), is fundamental to understanding cellular processes. A central task is parameter estimation—finding the model coefficients that minimize the discrepancy between simulated and experimental data. This is formulated as a nonlinear optimization problem, typically nonconvex due to the model structure, leading to multiple local minima [22]. Standard gradient-based local optimization methods can converge to suboptimal local solutions, yielding inaccurate models. Stochastic global optimization methods, while computationally faster, offer no guarantee of convergence to the global optimum in finite time [22].

Deterministic global optimization methods overcome this by employing mathematical strategies that rigorously confine the search for the optimum. They provide both a candidate solution and a provable bound on its optimality gap (the difference between the best-found solution and a lower bound on the global optimum) [22]. This guarantee is indispensable for producing reliable, reproducible models in computational biology. Two pivotal and often interconnected paradigms enabling this are Branch-and-Bound and Cutting-Plane methods.

Foundational Algorithm: The Branch-and-Bound Framework

Branch-and-bound is a general algorithm design paradigm for solving optimization problems by systematically enumerating candidate solutions via state-space search, organized as a tree, and using bounding functions to prune suboptimal branches [23].

Core Principles

The algorithm operates on two principles:

- Branching: Recursively splitting the search space (feasible region) into smaller subspaces.

- Bounding: Calculating lower (for minimization) and upper bounds on the objective function value within each subspace. A branch (node) is discarded ("pruned") if its lower bound exceeds the current best upper bound (incumbent solution), as it cannot contain the global optimum [23].

A generic B&B algorithm for minimization requires three problem-specific operations [23]:

branch(I): Partitions an instance I representing a solution subset into two or more child instances.bound(I): Computes a valid lower bound for any solution in the subspace of I.solution(I): Determines if I represents a single candidate solution and optionally returns a feasible solution to provide an upper bound.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Global Optimization Methods in Systems Biology

| Feature | Deterministic Methods (B&B, Cutting-Plane) | Stochastic Methods (e.g., Genetic Algorithms) |

|---|---|---|

| Optimality Guarantee | Yes. Convergence to global optimum within ε-tolerance is provable [22]. | No. Provide near-optimal solutions with unknown quality guarantees [22]. |

| Computational Burden | High. Tend to lead to large computational demands [22]. | Lower. Typically faster, especially for large-scale problems [22]. |

| Output | Solution and rigorous optimality gap [22]. | Solution only, with no proven bound. |

| Typical Application | Parameter estimation for critical, high-fidelity models where accuracy is paramount [22]. | Initial screening, exploration of vast search spaces, or when computational time is limited. |

Spatial Branch-and-Bound for Nonconvex MINLPs

In systems biology, problems often involve continuous variables (e.g., rate constants) and discrete decisions (e.g., model structure selection), leading to MINLP formulations. Standard B&B for integer programming branches on discrete variables. Spatial Branch-and-Bound (sBB) extends this to handle nonconvex continuous functions by branching on continuous variable domains [24].

The sBB algorithm iteratively refines convex relaxations of the original nonconvex problem. The relaxation provides a lower bound (for minimization), while the original problem solved locally provides an upper bound. The region (node) with the lowest lower bound is processed next. The process repeats until the gap between the global upper bound and the best lower bound is within a tolerance ε [24].

Table 2: Steps of a Spatial Branch-and-Bound Algorithm [24]

| Step | Action | Purpose in Systems Biology Context |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Initialization | Define the initial search region S (variable bounds). Set convergence tolerance ε, upper bound U=∞. | Establish biological parameter bounds (e.g., kinetic constants must be positive). |

| 2. Node Selection | Choose a region (node) from the tree to process. | Heuristic (e.g., best lower bound) to guide search toward promising parameter subspaces. |

| 3. Lower Bound | Solve a convex relaxation of the problem in the selected region. | Provides a guaranteed under-estimate of the best possible fit in that parameter region. |

| 4. Upper Bound | Solve the original nonconvex problem locally within the region. | Finds a candidate parameter set and calculates the actual sum-of-squared residuals. |

| 5. Pruning | If a node's lower bound > global upper bound U, discard it. Update U if a better solution is found. | Eliminates regions of parameter space that provably cannot contain the global best-fit. |

| 6. Check Convergence | If U - lower bound ≤ ε, terminate. The solution is ε-global optimal. | Determines when the parameter estimation result is sufficiently certain. |

| 7. Branching | Split the current region (e.g., bisect a continuous variable's range). Create new child nodes. | Refines the search, improving the tightness of convex relaxations in subsequent iterations. |

Diagram 1: Spatial Branch-and-Bound Algorithm Flow

Cutting-Plane Methods and Outer Approximation

Cutting-plane methods iteratively refine a feasible set by adding linear constraints ("cuts") that exclude parts of the relaxation where no optimal solution can lie, without cutting off any feasible integer or optimal solutions [25]. In global optimization, they are often used within an Outer Approximation framework.

Outer Approximation for Deterministic Global Optimization

This approach decomposes a nonconvex problem into two levels:

- Master Problem (MILP): A mixed-integer linear relaxation of the original problem, built using linear supports (cuts) of the nonlinear functions. Solving this provides a rigorous lower bound on the global optimum.

- Slave Problem (NLP): The original nonconvex problem is solved with fixed discrete variables from the master solution. This yields a feasible solution and an upper bound [22].

The algorithm iterates: the slave NLP solution generates new linearizations (cuts) that are added to the master MILP to tighten its relaxation. The bounds converge until the optimality gap is closed [22]. This method is particularly effective when integrated with convex relaxations of dynamic models.

Experimental Protocol: Parameter Estimation via Outer Approximation with Orthogonal Collocation

Aim: To deterministically estimate parameters (θ) for a biological ODE model from time-course experimental data.

Methodology:

- Model Discretization (Simultaneous Approach): Transform the continuous-time ODE model into an algebraic system using Orthogonal Collocation on Finite Elements [22]. This involves:

- Dividing the time horizon into NE finite elements.

- Within each element, approximating state variable profiles using Lagrange polynomials at NK orthogonal collocation points (e.g., Legendre roots).

- Enforcing the ODEs to hold exactly at these collocation points. This reformulation converts the dynamic parameter estimation problem into a large-scale, finite-dimensional Nonconvex NLP.

- Algorithm Execution (Outer Approximation): a. Initialization: Generate an initial set of linearizations (cuts) or a convex relaxation for the nonconvex terms in the discretized NLP. b. Master (MILP) Solution: Solve the current linear outer approximation. The solution provides a lower bound (LB) and proposed values for discrete variables (if any) and continuous variable bounds. c. Slave (NLP) Solution: Fix any discrete variables from (b) and solve the original nonconvex NLP locally (e.g., using a gradient-based solver). The solution provides an upper bound (UB) and a new feasible parameter set θ. d. Cut Generation: Linearize the nonlinear constraints (from the discretized ODEs and objective) around the solution θ. Add these linear constraints as cuts to the master MILP. These cuts will remove the current master solution in the next iteration if it is not optimal. e. Termination Check: If UB - LB ≤ ε, stop. The current UB solution is ε-global optimal. Otherwise, return to step (b).

Diagram 2: Outer Approximation Iterative Algorithm

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Deterministic Global Optimization in Systems Biology

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Deterministic Global Solver | Core software implementing sBB or outer approximation algorithms. | Commercial: BARON, ANTIGONE. Open-source: Couenne, SCIP (for MINLP) [22]. |

| Modeling & Discretization Environment | Platform to encode biological ODE models and perform orthogonal collocation. | Pyomo (Python), GAMS, MATLAB with CasADi. Enables algebraic reformulation of dynamic problems [22]. |

| Local NLP Solver | Solves the nonconvex slave problems and provides upper bounds. | IPOPT, CONOPT, SNOPT. Often interfaced within the global solver framework. |

| MILP Solver | Solves the linear/convex master problems to provide lower bounds. | CPLEX, Gurobi, CBC. Critical for the efficiency of outer approximation methods. |

| Convex Relaxation Library | Provides routines to generate convex envelopes for common nonconvex terms (e.g., bilinear, fractional). | Part of advanced solvers like BARON. Custom implementations can use McCormick relaxations [22]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Computational resource to handle the significant CPU burden of rigorous global optimization for large models. | Parallelization of branch-and-bound tree search can dramatically reduce wall-clock time. |

| Experimental Dataset | Time-series quantitative measurements of species concentrations. | The objective function (e.g., sum of squared residuals) is minimized against this data [22]. |

| Parameter Bounds (Biological Priors) | Physically/physiologically plausible lower and upper bounds for all model parameters. | Essential for initializing the search space and accelerating convergence by pruning [24]. |

In the pursuit of predictive and reliable models in systems biology, deterministic global optimization strategies are non-negotiable for critical parameter estimation tasks. The Branch-and-Bound framework, particularly in its spatial variant, and Cutting-Plane methods, frequently deployed via Outer Approximation algorithms, provide the mathematical machinery to deliver solutions with guaranteed proximity to the global optimum. While computationally intensive, the integration of these methods with robust model discretization techniques like orthogonal collocation represents the state-of-the-art for reconciling complex, nonlinear biological dynamics with experimental data. Their application ensures that conclusions drawn from computational models rest upon a foundation of mathematical certainty, a cornerstone of rigorous systems biology research.

Global optimization (GO) is a cornerstone of modern computational systems biology, essential for solving complex nonlinear problems where traditional local optimization methods fail. These challenges include model identification, where parameters of dynamic biological models are estimated from experimental data, and stimulation design, which aims to synthetically achieve a desired cellular behavior [1]. The mathematical models describing biological networks are typically nonlinear, highly constrained, and involve a large number of decision variables, making their solution a daunting task. Efficient and robust GO techniques are therefore critical for extracting meaningful biological insights from computational models.

The core challenge in systems biology is that the energy landscapes—or more broadly, solution spaces—of these problems are often characterized by a high-dimensional, nonlinear, and multi-modal topology. The number of local minima in such spaces can grow exponentially with system complexity, making it easy for algorithms to become trapped in suboptimal solutions [26]. Stochastic and metaheuristic algorithms provide a powerful approach to navigate these complex landscapes by strategically balancing two opposing search strategies: exploration (searching new regions of the space) and exploitation (refining good solutions already found) [27] [26]. This guide focuses on three pivotal methodologies within this domain: Genetic Algorithms, Scatter Search, and Simulated Annealing, detailing their mechanisms, applications, and implementation in systems biology research.

Table 1: Core Stochastic Metaheuristics in Systems Biology

| Algorithm | Primary Inspiration | Key Strengths | Typical Systems Biology Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithms (GA) | Biological evolution | Effective for complex, high-dimensional spaces; naturally parallelizable [28] | Parameter estimation, network model inference, multi-objective optimization |

| Scatter Search (SS) | Structured solution combination | High solution quality through intensification and diversification; versatile and adaptable [29] | Model identification, optimization of stimulation protocols [1] |

| Simulated Annealing (SA) | Thermodynamic annealing process | Strong theoretical convergence guarantees; simple to implement [30] | Molecular structure prediction, parameter fitting, network randomization [26] [31] |

Methodological Foundations and Protocols

Genetic Algorithms (GA)