Global Optimization for Model Tuning: Enhancing Accuracy and Efficiency in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to global optimization methods for model tuning, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Global Optimization for Model Tuning: Enhancing Accuracy and Efficiency in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to global optimization methods for model tuning, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers the foundational principles of hyperparameter tuning and its critical role in building accurate, generalizable models. The content explores a suite of deterministic and stochastic optimization techniques, from Bayesian optimization to genetic algorithms, and details their practical application in pharmaceutical R&D for tasks like biomarker identification and clinical trial optimization. Readers will also learn strategies to overcome common challenges like overfitting and computational constraints, and how to rigorously validate and compare model performance to drive more efficient and successful drug discovery pipelines.

The Fundamentals of Model Tuning and Why Global Optimization Matters

Core Concepts: Parameters vs. Hyperparameters

What is the fundamental difference between a model parameter and a hyperparameter?

Model Parameters are the internal variables that the model learns automatically from the training data during the training process. They are not set manually by the practitioner. Examples include the weights and biases in a neural network or the slope and intercept in a linear regression model. These parameters define the model's learned representation of the underlying patterns in the data and are used to make predictions on new, unseen data [1] [2].

Hyperparameters, in contrast, are external configuration variables that are set before the training process begins. They control the overarching behavior of the learning algorithm itself. They cannot be learned directly from the data and must be defined by the user or through an automated tuning process. Examples include the learning rate, number of layers in a neural network, batch size, and number of epochs [1] [3].

The table below summarizes the key differences:

| Characteristic | Model Parameters | Hyperparameters |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Making predictions [1] | Estimating model parameters; controlling the training process [1] [3] |

| How they are set | Learned from data during training [1] [2] | Set manually before training begins [1] [2] |

| Determined by | Optimization algorithms (e.g., Gradient Descent, Adam) [1] | Hyperparameter tuning (e.g., Grid Search, Bayesian Optimization) [1] [3] |

| Influence | Final model performance on unseen data [1] | Efficiency and accuracy of the training process [1] |

| Examples | Weights & biases (Neural Networks), Slope & intercept (Linear Regression) [1] | Learning rate, number of epochs, number of hidden layers, batch size [1] [3] |

Why is understanding this distinction critical for effective model tuning in drug discovery?

In AI-driven drug discovery (AIDD), the choice of hyperparameters directly influences the model's ability to learn from complex, multimodal datasets—such as chemical structures, omics data, and clinical trial information—and to generate novel, viable drug candidates [4]. Proper hyperparameter tuning is not merely a technical step; it is essential for creating robust, repeatable, and scalable AI platforms that can accurately model biology and impact scientific decision-making [4]. Inefficient tuning can lead to models that overfit on small, noisy biological datasets or fail to converge, wasting substantial computational resources and time [3] [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: My model is not converging, or training is unstable.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Inappropriate Learning Rate

- Solution: The learning rate is perhaps the most critical hyperparameter. A rate that is too high can cause the model to overshoot the minimum loss, leading to divergence. A rate that is too low can make training prohibitively slow or cause it to get stuck in a local minimum [3].

- Action: Implement a learning rate scheduler or decay to reduce the learning rate over time, allowing for finer weight updates as training progresses [3]. Use optimization algorithms like Adam that adapt the learning rate for each parameter [3].

Cause: Improper Weight Initialization

- Solution: Poorly chosen initial weights can lead to vanishing or exploding gradients, where the updates become excessively small or large, halting learning [3].

- Action: Use established initialization schemes (e.g., He, Xavier) suitable for your chosen activation function. Consider this an architecture-level hyperparameter to validate [3].

Cause: Inadequate Model Capacity

- Solution: A model with too few layers or neurons (low capacity) may be too simple to capture the complex relationships in drug discovery data, such as structure-activity relationships [3] [2].

- Action: Systematically increase architecture hyperparameters like the number of layers or number of neurons per layer, monitoring performance on a validation set to avoid overfitting [2].

Problem 2: My model performs well on training data but poorly on validation/test data (Overfitting).

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Insufficient Regularization

- Solution: The model is memorizing the training data instead of learning generalizable patterns. This is a significant risk when working with limited biological datasets [3] [5].

- Action: Tune regularization hyperparameters.

- Increase the dropout rate, which randomly disables neurons during training to prevent co-adaptation [3].

- Increase L1 or L2 regularization strength, which adds a penalty for large weights to enforce model simplicity [3] [2].

- Use early stopping, where the number of epochs is set to halt training once validation performance stops improving [1] [3].

Cause: Data Imbalance

Problem 3: The model training process is too slow or computationally expensive.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause: Inefficient Batch Size

- Solution: A very small batch size can lead to noisy gradient estimates and slow convergence. A very large batch size may require more memory and computation per update, and can sometimes lead to poorer generalization [3].

- Action: Tune the batch size to find a balance between training stability, speed, and hardware memory constraints. Larger batches often speed up training but may require adjustments to the learning rate [3].

Cause: Overly Complex Model Architecture

- Solution: A model with an excessive number of parameters for the task at hand is inefficient [6].

- Action: Perform architecture search to find a simpler model. Use pruning strategies to remove unnecessary connections in the neural network after initial training, effectively reducing model size and increasing inference speed without significant accuracy loss [6].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the main categories of hyperparameters?

Hyperparameters can be broadly classified into three categories [2]:

- Architecture Hyperparameters: Control the model's structure (e.g., number of layers in a DNN, number of neurons per layer, number of trees in a random forest).

- Optimization Hyperparameters: Govern the training process (e.g., learning rate, batch size, number of epochs, choice of optimizer).

- Regularization Hyperparameters: Help prevent overfitting (e.g., dropout rate, L1/L2 regularization strength).

Which hyperparameter tuning method should I start with?

The choice depends on your computational resources and the number of hyperparameters you need to optimize.

- Grid Search: Systematically tries every combination of hyperparameters in a predefined set. It is exhaustive but can be computationally prohibitive for a large number of hyperparameters or deep learning models [3] [7].

- Random Search: Randomly samples combinations from predefined distributions. It is often more efficient than Grid Search for discovering good hyperparameter values with fewer trials, as it explores the search space more broadly [3] [7].

- Bayesian Optimization: Builds a probabilistic model of the objective function to guide the search towards promising hyperparameters. It is particularly well-suited for optimizing expensive-to-train models (like many in drug discovery) as it typically requires fewer iterations than Grid or Random Search to find a good configuration [3] [7].

For most practical applications in drug discovery, starting with Random Search or Bayesian Optimization is recommended due to their superior efficiency [3].

How does hyperparameter optimization relate to global optimization?

Hyperparameter optimization (HPO) is a quintessential global optimization problem. The goal is to find the set of hyperparameters that minimizes a loss function (or maximizes a performance metric) on a validation set. This loss landscape is often non-convex, high-dimensional, and noisy, with evaluations (model training runs) being very expensive [7]. Global optimization methods, such as Bayesian Optimization, are specifically designed to handle these challenges by efficiently exploring the vast hyperparameter space and exploiting promising regions, avoiding convergence to poor local minima [7].

What is Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) and why is it important for large models?

PEFT is a set of techniques that adapts large pre-trained models (like LLMs) to downstream tasks by fine-tuning only a small subset of parameters or adding and training a small number of extra parameters. Methods like LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) and prefix tuning are examples [8].

This is crucial because full fine-tuning of models with billions of parameters is computationally infeasible for most research labs. PEFT dramatically reduces computational and storage costs, often achieving performance comparable to full fine-tuning, making it possible to leverage state-of-the-art models in specialized domains like drug discovery with limited resources [8].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Benchmarking Hyperparameter Optimization Methods

This protocol outlines a standard experiment for comparing HPO methods, relevant to global optimization research.

1. Objective: To compare the efficiency and performance of Grid Search, Random Search, and Bayesian Optimization for tuning a Graph Neural Network (GNN) on a molecular property prediction task (e.g., solubility, toxicity).

2. Materials (The Scientist's Toolkit):

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Curated Chemical Dataset (e.g., from ChEMBL) | Provides the structured molecular data (e.g., SMILES) and associated experimental property values for training and evaluation. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | The machine learning model (e.g., ChemProp) that learns to predict molecular properties from graph representations of molecules [5]. |

| Hyperparameter Optimization Library (e.g., Optuna, Scikit-Optimize) | Software frameworks that implement various HPO strategies like Bayesian Optimization [6]. |

| Computational Cluster (GPU-enabled) | High-performance computing resources to manage the computationally intensive process of training multiple model configurations in parallel. |

3. Procedure:

a. Define the Search Space: Establish the hyperparameters to tune and their value ranges. * Learning Rate: Log-uniform distribution between ( 1e-5 ) and ( 1e-2 ) * Dropout Rate: Uniform distribution between ( 0.1 ) and ( 0.5 ) * Number of GNN Layers: Choice of [3, 4, 5, 6] * Hidden Layer Size: Choice of [128, 256, 512]

b. Split the Data: Partition the dataset into training, validation, and test sets using a challenging split (e.g., scaffold split) to assess generalization [5].

c. Configure HPO Methods: * Grid Search: Define a grid covering all combinations of a subset of the search space. * Random Search: Set a budget (e.g., 50 trials) to randomly sample from the full search space. * Bayesian Optimization: Set the same budget (50 trials) using a tool like Optuna.

d. Run Optimization: For each HPO method, run the specified number of trials. Each trial involves training a model with a specific hyperparameter set and evaluating its performance on the validation set.

e. Evaluate: Select the best hyperparameter set found by each method, train a final model on the combined training and validation set, and evaluate it on the held-out test set.

4. Key Metrics: Record for each HPO method:

- Best Validation Score (e.g., ROC-AUC, RMSE)

- Final Test Score

- Total Computational Time / Cost

- Number of Trials to Convergence

The table below summarizes the core hyperparameters and their typical impact on model behavior, synthesizing information from the search results.

| Hyperparameter | Common Values / Methods | Impact on Model / Tuning Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Learning Rate | ( 0.1, 0.01, 0.001, ) etc. (Log scale) [3] | Controls step size in parameter updates. Too high → divergence; too low → slow training. Often tuned on a log scale [3]. |

| Batch Size | 16, 32, 64, 128, 256 [3] | Impacts gradient stability and training speed. Larger batches provide more stable gradients but may generalize worse [3]. |

| Number of Epochs | 10 - 100+ [3] | Controls training duration. Too few → underfitting; too many → overfitting. Use early stopping [1] [3]. |

| Dropout Rate | 0.2 - 0.5 [3] | Regularization technique. Higher rate prevents overfitting but may slow learning. Balance is key [3]. |

| Optimizer | SGD, Adam, RMSprop [3] | Algorithm for updating weights. Adam is often a robust default choice. The choice itself is a hyperparameter [3]. |

| # of Layers / Neurons | Model-dependent | Defines model capacity. More layers/neurons can capture complexity but increase overfitting risk and computational cost [3] [2]. |

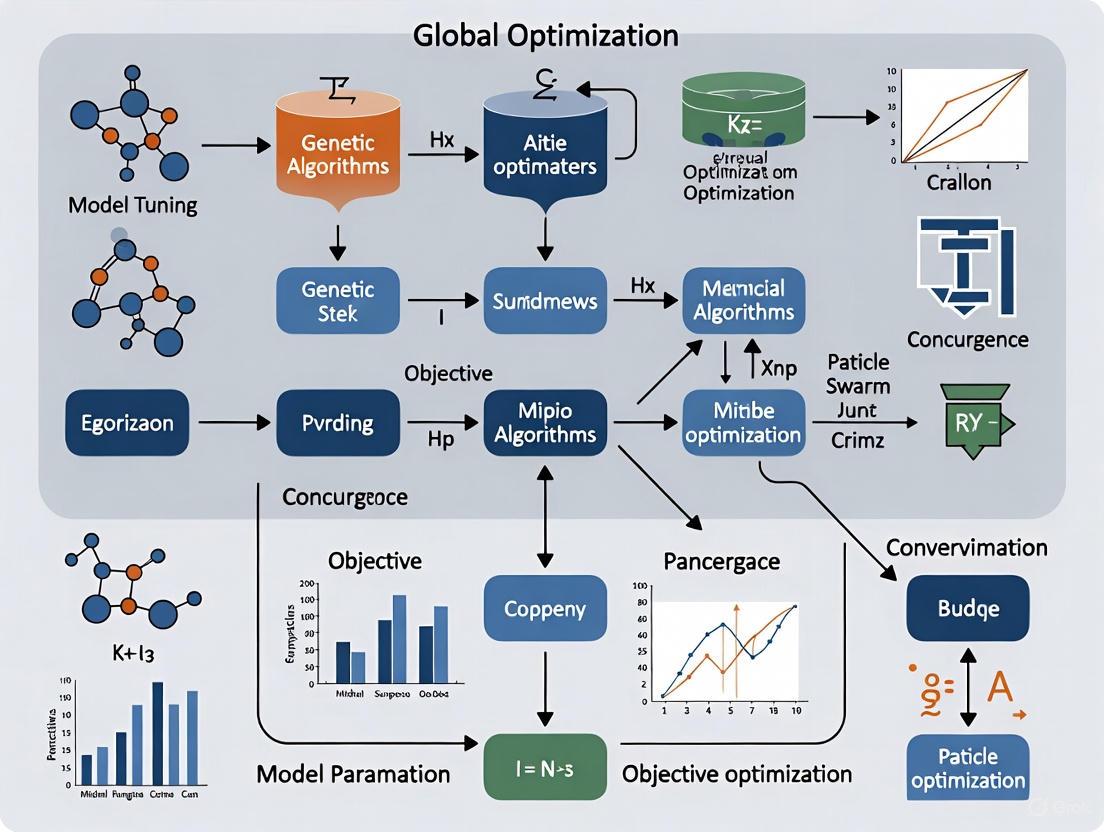

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a high-level, iterative workflow for global model tuning, integrating the concepts of hyperparameter optimization and validation within a drug discovery context.

In the realm of scientific research, particularly in computationally intensive fields like drug development, model tuning is not merely a final step but a fundamental component of the research lifecycle. It is the systematic process of adjusting a model's parameters to improve its performance, efficiency, and reliability. For researchers and scientists, mastering tuning is crucial for transforming a prototype model into a robust tool capable of delivering accurate, generalizable, and actionable results.

This technical support center is designed within the broader context of global optimization methods for model tuning research. It provides practical, troubleshooting-oriented guidance to help you navigate common challenges and implement effective tuning strategies in your experiments.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section addresses specific, high-frequency issues encountered during model tuning experiments.

FAQ 1: My model performs well on training data but poorly on unseen validation data. What is happening and how can I fix it?

- Problem Identified: This is a classic sign of overfitting. The model has learned the noise and specific details of the training data to the point that it negatively impacts its performance on new data.

- Solution Pathway:

- Implement Regularization: Apply L1 (Lasso) or L2 (Ridge) regularization to penalize overly complex models and prevent coefficients from fitting too perfectly to the training data [6].

- Simplify the Model: Reduce model complexity by using pruning strategies to remove unnecessary neurons or weights [6] [9]. This decreases the model's capacity to memorize the training set.

- Expand Your Data: Use data augmentation techniques to artificially increase the size and diversity of your training set, helping the model learn more generalizable features.

- Use Cross-Validation: Employ k-fold cross-validation during tuning to ensure that your model's performance is consistent across different subsets of your data [6].

FAQ 2: The tuning process is taking too long and consuming excessive computational resources. How can I make it more efficient?

- Problem Identified: Full fine-tuning of large models, especially in drug discovery applications, is computationally expensive and often infeasible for research teams with limited resources [10].

- Solution Pathway:

- Adopt Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT): Techniques like LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) and its quantized version QLoRA can drastically reduce the number of trainable parameters and GPU memory requirements, often making it possible to fine-tune large models on a single GPU [10].

- Leverage Surrogate Models: In global optimization, use fast, simplified surrogate models (e.g., simplex-based regression predictors) for the initial global search phase. This approach can identify promising regions of the parameter space before committing resources to high-fidelity model evaluation [11].

- Optimize Hyperparameter Search: Replace exhaustive methods like Grid Search with more efficient ones like Bayesian Optimization, which uses past results to intelligently select the next hyperparameters to evaluate [6] [9].

FAQ 3: How do I choose the right global optimization method for my model tuning task?

- Problem Identified: Selecting an inappropriate optimization algorithm can lead to convergence on suboptimal solutions (local minima) or unacceptably long computation times.

- Solution Pathway: The choice depends on the nature of your problem's search space. The table below compares the two primary categories of global optimization (GO) methods [12].

| Method Category | Principle | Strengths | Weaknesses | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stochastic Methods [12] | Incorporate randomness to explore the parameter space broadly. | High probability of finding the global minimum; good for complex, high-dimensional landscapes. | No guarantee of optimality; can require many function evaluations. | Predicting molecular conformations [12], tuning complex neural networks. |

| Deterministic Methods [12] | Rely on analytical rules (e.g., gradients) without randomness. | Precise convergence; follows a defined trajectory based on physical principles. | Computationally expensive; prone to getting stuck in local minima. | Problems with smoother energy landscapes where gradient information is reliable. |

FAQ 4: After tuning, my model's inference is too slow for practical application. What can I do?

- Problem Identified: A large, unoptimized model will have high latency, making it unsuitable for real-time applications or scaling to millions of requests.

- Solution Pathway:

- Apply Quantization: Reduce the numerical precision of the model's parameters (e.g., from 32-bit floating-point to 8-bit integers). This can shrink model size by up to 75% and significantly speed up inference [6] [9].

- Use Knowledge Distillation: Train a smaller, faster "student" model to mimic the performance of your large, tuned "teacher" model, preserving accuracy while gaining speed [9].

- Perform Model Pruning: Remove redundant weights or neurons that contribute little to the output. This can reduce model size by 30-40% without significant accuracy loss [9].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: A Two-Phase Global Tuning Approach

This protocol outlines a robust methodology for tuning models, integrating global optimization strategies suitable for drug discovery and molecular design research [12].

Objective: To systematically identify the optimal model configuration that maximizes accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency.

Phase 1: Global Exploration with Low-Fidelity Models

Problem Formulation:

- Define your decision variables (e.g., hyperparameters like learning rate, number of layers) and the objective function (e.g., validation accuracy, minimization of loss).

- Set the target performance metrics (e.g., target operating frequencies for an antenna [11]).

Initial Stochastic Search:

- Method: Employ a population-based stochastic method such as a Genetic Algorithm (GA) or Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [12] [11].

- Execution:

- Generate an initial population of candidate parameter sets.

- Use a low-fidelity model (e.g., a coarse-grid EM simulation [11] or a model with reduced depth/width) to evaluate each candidate. This drastically reduces computation time per evaluation.

- Apply the algorithm's operators (mutation, crossover) to evolve the population toward better solutions over multiple generations.

- Output: A set of promising, high-performing parameter regions for further refinement.

Phase 2: Local Refinement with High-Fidelity Models

- Deterministic Local Tuning:

- Method: Switch to a gradient-based deterministic method (e.g., AdamW, AdamP [13]) for precise convergence.

- Execution:

- Initialize the tuning process with the best candidates from Phase 1.

- Use the high-fidelity, computationally expensive model for all evaluations in this phase.

- To accelerate this step, compute sensitivity (gradients) only along principal directions that account for the majority of the response variability [11].

- Validation: Perform k-fold cross-validation on the final tuned model to obtain an unbiased estimate of its generalization performance [6].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the structured progression from global exploration to local refinement, highlighting the key decision points and tools at each stage.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

This table details key computational tools and methodologies that function as the essential "research reagents" for modern model tuning and optimization experiments.

| Item | Function / Explanation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) [10] | A parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) method that adds small, trainable rank decomposition matrices to model layers, freezing the original weights. | Adapting large language models (LLMs) for domain-specific tasks (e.g., medical text) with limited compute. |

| Bayesian Optimization [6] [9] | A sequential design strategy for global optimization of black-box functions that builds a surrogate model to find the hyperparameters that maximize performance. | Efficiently tuning hyperparameters when each evaluation is computationally expensive. |

| Pruning Algorithms [6] [9] | Methods that remove unnecessary weights or neurons from a neural network to reduce model size and increase inference speed. | Creating smaller, faster models for deployment on edge devices or in latency-sensitive applications. |

| Quantization Tools (e.g., TensorRT) [9] | Techniques and software that reduce the numerical precision of model parameters (e.g., FP32 to INT8) to shrink model size and accelerate inference. | Optimizing models for production environments to reduce latency and hardware costs. |

| Global Optimization Algorithms (e.g., GA, CMA-ES) [12] [13] | A class of stochastic and deterministic algorithms designed to locate the global optimum of a function, not just local optima. | Predicting molecular conformations by finding the global minimum on a complex potential energy surface [12]. |

| Surrogate Models (Simplex Predictors) [11] | Fast, simplified models used to approximate the behavior of a high-fidelity simulator during the initial stages of global optimization. | Accelerating the design and tuning of complex systems like antennas by reducing the number of costly simulations. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between stochastic and deterministic global optimization methods?

Stochastic methods incorporate randomness in the generation and evaluation of structures, allowing broad sampling of the potential energy surface (PES) to avoid premature convergence. In contrast, deterministic methods rely on analytical information such as energy gradients or second derivatives to direct the search toward low-energy configurations following defined rules without randomness. Stochastic methods are particularly well-suited for exploring complex, high-dimensional energy landscapes, while deterministic approaches often provide more precise convergence but can be computationally expensive for systems with numerous local minima [12].

2. What are the most common applications of global optimization in computational chemistry and drug discovery?

Global optimization plays a central role in predicting molecular and material structures, particularly in locating the most stable configuration of a system (the global minimum on the PES). These predictions are critical for accurately determining thermodynamic stability, reactivity, spectroscopic behavior, and biological activity—essential properties in drug discovery, catalysis, and materials design. Specific applications include conformer sampling, cluster structure prediction, surface adsorption studies, and crystal polymorph prediction [12].

3. How does the system size affect the challenge of global optimization?

The complexity of potential energy surfaces increases dramatically with system size. Theoretical models suggest the number of minima scales exponentially with the number of atoms, following a relation of the form Nmin(N) = exp(ξN), where ξ is a system-dependent constant. A similar scaling applies to transition states. This exponential relationship means the energy landscape becomes increasingly complex for larger systems, presenting a significant challenge to global structure prediction [12].

4. What are the advantages of hybrid global optimization approaches?

Hybrid approaches that combine features from multiple algorithms can significantly enhance search performance, guide exploration, and accelerate convergence in complex optimization landscapes. For example, the integration of machine learning techniques with traditional methods like genetic algorithms has demonstrated substantial potential. These hybrids effectively balance exploration of the energy surface with exploitation of promising regions, which remains an enduring challenge in GO technique design [12].

5. What computational resources are typically required for global optimization of molecular systems?

The computational expense varies significantly based on system size and method selection. Nature-inspired techniques often require thousands of fitness function evaluations, while surrogate-assisted procedures can reduce this burden. For context, a recently developed globalized optimization procedure for antenna design required approximately eighty high-fidelity simulations—considered remarkably efficient for a global search. For molecular systems using quantum mechanical methods like density functional theory, computational demands can be substantial, particularly for large or flexible molecules [12] [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Optimization Algorithm Converges to Local Minima Instead of Global Minimum

Description: The optimization procedure repeatedly converges to suboptimal local minima rather than locating the true global minimum on the potential energy surface.

Solution:

- Increase algorithmic randomness: For stochastic methods, adjust parameters to enhance exploration, such as increasing mutation rates in genetic algorithms or initial temperature in simulated annealing [12].

- Implement hybrid approaches: Combine global exploration with local refinement phases. The global exploration identifies promising regions, while local refinement precisely locates minima [12].

- Utilize population diversity maintenance: In population-based methods, implement mechanisms to preserve genetic diversity and prevent premature convergence [12].

- Employ multi-start strategies: Execute multiple optimizations from different starting points and select the best result [11].

Problem: Excessive Computational Requirements for Global Optimization

Description: The computational cost of global optimization becomes prohibitive, particularly when using high-fidelity models or large molecular systems.

Solution:

- Implement variable-resolution approaches: Use lower-fidelity models during initial global search stages, then refine with high-fidelity models. This can reduce computational expense while maintaining accuracy [11].

- Apply surrogate modeling: Replace expensive function evaluations with approximate models. Simplex-based regression predictors targeting operating parameters rather than complete frequency responses can be particularly effective [11].

- Utilize restricted sensitivity updates: Perform finite-differentiation sensitivity updates only along principal directions that majorly affect response variability [11].

- Leverage parallelization: Distribute function evaluations across multiple computing cores, as many global optimization algorithms are embarrassingly parallel [12].

Problem: Handling of Constraints in Global Optimization

Description: Optimization fails to properly handle constraints, either violating physical realities or failing to converge due to restrictive feasible regions.

Solution:

- Classify constraint types: Separate computationally cheap constraints (e.g., antenna size) that can be treated explicitly from expensive constraints requiring EM analysis, which are better handled via penalty functions [11].

- Adjust tolerance settings: For genetic algorithm implementations, carefully tune tolerance parameters like

TolFunandTolConwhile increasing population size and generations to better explore constrained landscapes [14]. - Monitor progress with visualization: Use plot functions to track how algorithms handle constraints throughout the optimization process [14].

Problem: Geometry Optimization Failure in Quantum Chemistry Codes

Description: Computational chemistry software fails during geometry optimization, particularly with internal coordinate generation.

Solution:

- Check input specifications: Verify correct units (default is often Angstroms) and physically sensible geometries where atoms aren't too close or distant [15].

- Address linear chain issues: For molecules with linear chains of four or more atoms, explicitly define internal coordinates or use dummy atoms to break linearity [15].

- Modify covalent scaling: For highly connected systems, reduce the scaling factor for covalent radii (e.g.,

cvr_scaling 0.9) or specify a minimal set of bonds [15]. - Utilize Cartesian fallback: When internal coordinate generation fails, employ Cartesian coordinates using the

NOAUTOZkeyword [15].

Problem: Performance and Parallelization Issues in Computational Chemistry Software

Description: Software exhibits poor performance, crashes, or parallelization failures during execution.

Solution:

- Optimize environment variables: For NWChem, unset problematic MPI environment variables (

MPI_LIB,MPI_INCLUDE,LIBMPI) and ensure the PATH correctly points to mpif90 [15]. - Configure memory settings: Set

ARMCI_DEFAULT_SHMMAXto appropriate values (at least 2048 for OPENIB networks) and verify system kernel parameters match these settings [15]. - Address WSL-specific issues: For Windows Subsystem for Linux crashes, execute

echo 0 | sudo tee /proc/sys/kernel/yama/ptrace_scopeto resolve CMA support errors [15]. - Verify restart capabilities: Ensure proper use of

START/RESTARTdirectives and consistent permanent directory specification for restarting interrupted calculations [15].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Standard Global Optimization Workflow for Molecular Systems

Purpose: To locate the global minimum on a molecular potential energy surface through a systematic combination of global exploration and local refinement.

Procedure:

- Initial Population Generation: Create an initial set of candidate structures using random sampling, physically motivated perturbations, or heuristic design.

- Local Optimization: Optimize each candidate structure to the nearest local minimum.

- Redundancy Removal: Eliminate duplicate or symmetrically equivalent structures.

- Frequency Analysis: Confirm each unique candidate represents a true minimum (no imaginary frequencies).

- Global Minimum Identification: Designate the lowest-energy structure as the putative global minimum.

- Iterative Refinement: Repeat with enhanced sampling in promising regions until convergence criteria met.

Variations: Specific algorithms differ in how they navigate between steps 1-6, with some implementing intertwined search processes rather than distinct phases [12].

Two-Stage Globalized Optimization with Variable-Resolution Models

Purpose: To achieve global optimization with reduced computational expense through strategic model management.

Procedure:

- Global Search Phase:

- Utilize low-fidelity models for initial broad exploration

- Employ regression models targeting operating parameters

- Conduct search in space of antenna operating parameters

- Terminate with loose compliance criteria

- Local Refinement Phase:

- Switch to high-fidelity models for precise optimization

- Implement gradient-based parameter tuning

- Restrict sensitivity updates to principal directions

- Apply rigorous convergence criteria

Applications: Particularly effective for antenna design, molecular structure prediction, and other applications where simulation expense limits pure global optimization [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Global Optimization Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GlobalOptimization Package (Maple) | Software Package | Solves nonlinear programming problems over bounded regions | General mathematical optimization [16] |

| Global Optimization Toolbox (MATLAB) | Software Toolbox | Implements genetic algorithms and other global optimizers | Engineering and scientific optimization [14] |

| NWChem | Computational Chemistry Software | Performs quantum chemical calculations with optimization capabilities | Molecular structure prediction and property calculation [15] |

| Global Arrays/ARMCI | Programming Libraries | Provides shared memory operations for distributed computing | High-performance computational chemistry [15] |

| Simplex-Based Regression Predictors | Algorithmic Framework | Creates low-complexity surrogates targeting operating parameters | Antenna optimization, molecular descriptor relationships [11] |

| Variable-Resolution EM Simulations | Modeling Technique | Balances computational speed and accuracy through fidelity adjustment | Resource-intensive optimization problems [11] |

Method Classification and Data

Table: Classification of Major Global Optimization Methods

| Method Category | Specific Methods | Key Characteristics | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stochastic Methods | Genetic Algorithms, Simulated Annealing, Particle Swarm Optimization, Artificial Bee Colony | Incorporate randomness; avoid premature convergence; require multiple evaluations | Complex, high-dimensional energy landscapes; systems with many local minima [12] |

| Deterministic Methods | Molecular Dynamics, Single-Ended Methods, Basin Hopping | Follow defined rules without randomness; use gradient/derivative information; precise convergence | Smaller systems; when analytical derivatives available; sequential evaluation feasible [12] |

| Hybrid Approaches | Machine Learning + Traditional Methods, Variable-Resolution Strategies | Combine exploration/exploitation; balance efficiency and robustness; leverage multiple algorithmic strengths | Challenging optimization problems where pure methods struggle; resource-constrained environments [12] [11] |

Table: Historical Development of Key Global Optimization Methods

| Year | Method | Key Innovation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1957 | Genetic Algorithms | Evolutionary strategies with selection, crossover, mutation | [12] |

| 1959 | Molecular Dynamics | Atomic motion exploration via Newton's equations integration | [12] |

| 1983 | Simulated Annealing | Stochastic temperature-cooling for escaping local minima | [12] |

| 1995 | Particle Swarm Optimization | Collective motion-inspired population-based search | [12] |

| 1997 | Basin Hopping | Transformation of PES into discrete local minima | [12] |

| 1999 | Parallel Tempering MD | Structure exchange between different temperature simulations | [12] |

| 2005 | Artificial Bee Colony | Foraging behavior-inspired structure discovery | [12] |

| 2013 | Stochastic Surface Walking | Adaptive PES exploration with guided stochastic steps | [12] |

Workflow Visualization

Global Optimization Methodology

Potential Energy Surface Features

Key Challenges in Drug Development that Global Optimization Addresses

FAQs: Common Challenges in Global Optimization for Drug Development

FAQ 1: My global optimization algorithm converges prematurely to a local minimum, missing better molecular candidates. How can I improve its exploration?

Answer: Premature convergence is a common challenge in complex molecular landscapes. You can address this by implementing algorithms that explicitly maintain population diversity.

- Solution: Consider using algorithms like Tribe-PSO, a hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization model based on Hierarchical Fair Competition (HFC) principles [17]. In this model, particles are divided into multiple layers, and the convergence procedure is split into phases. Competition is primarily allowed among particles with comparable fitness, which helps prevent the population from losing diversity too early and avoids entrapment in local optima [17].

- Alternative Approach: The Swarm Intelligence-Based (SIB) method incorporates a "Random Jump" operation [18]. If a particle's position does not improve after mixing with local and global best candidates, the algorithm randomly alters a portion of the particle's entries. This stochastic kick helps the search escape local optima and explore new regions of the chemical space [18].

FAQ 2: The computational cost of evaluating candidate molecules using high-fidelity simulations is prohibitively high. How can I make global optimization feasible?

Answer: This is a central bottleneck. The standard solution is to adopt a variable-resolution or multi-fidelity strategy [11].

- Solution: Implement a two-stage optimization process.

- Global Exploration: Conduct the initial, broad search using a fast, low-fidelity model. In drug design, this could be a coarse-grained molecular model, a 2D-structure-based property predictor, or a machine learning model trained to approximate more expensive calculations [11] [19].

- Local Refinement: Take the most promising candidates from the first stage and perform a rigorous, gradient-based tuning using a high-fidelity model (e.g., all-atom molecular dynamics simulation or precise docking calculations) [11].

- Experimental Protocol: A proven methodology is to use a low-fidelity EM analysis for the global search stage, terminated with loose convergence criteria. This is complemented by a final local tuning stage that uses a high-resolution EM analysis but is accelerated by computing sensitivity only along principal directions that most affect the response [11].

FAQ 3: How can I ensure that the molecules generated by a global optimization algorithm are synthesizable and not just theoretical constructs?

Answer: Integrate rules of synthetic chemistry directly into the molecular generation process [19].

- Solution: Employ a fragment-based approach with virtual synthesis. Instead of generating molecules atom-by-atom, the algorithm should assemble them from validated chemical fragments according to predefined reaction rules (e.g., BRICS rules) [19].

- Experimental Protocol: The CSearch algorithm provides a robust framework [19]. It starts with an initial set of diverse, drug-like molecules. During optimization, "trial chemicals" are generated by virtually fragmenting existing candidates and recombining the fragments with new partners from a fragment database, ensuring all generated molecules adhere to chemically plausible synthesis pathways [19].

Troubleshooting Guide: Global Optimization in Action

Case Study: Optimizing a Drug Candidate's Binding Affinity

Scenario: A researcher uses a global optimization algorithm to improve a lead compound's binding affinity for a target protein. The process is slow, and results are inconsistent.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| The algorithm consistently produces invalid molecular structures. | The molecular representation (e.g., SMILES string) is being manipulated without chemical constraints. | Switch to a fragment-based or graph-based representation that maintains chemical validity during crossover and mutation operations [19] [18]. |

| Optimal molecules have poor drug-likeness (e.g., wrong molecular weight, too many rotatable bonds). | The objective function only considers binding energy, ignoring key physicochemical properties. | Reformulate the objective function to be multi-objective. Combine the primary goal (e.g., binding affinity) with a drug-likeness metric like Quantitative Estimate of Druglikeness (QED) [18]. |

| The optimization is slow due to expensive molecular docking at every step. | Each fitness evaluation requires a full, high-resolution docking calculation. | Use a surrogate-assisted approach. Train a fast Graph Neural Network (GNN) to approximate docking scores and use this as the objective function for most steps, validating only top candidates with true docking [19]. |

Quantitative Comparison of Global Optimization Methods

The table below summarizes the performance and characteristics of several algorithms, providing a guide for selection.

Table 1: Comparison of Global Optimization Methods in Drug Development

| Method | Type | Key Mechanism | Reported Efficiency (Representative) | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tribe-PSO [17] | Population-based (Stochastic) | Hierarchical layers & multi-phase convergence to preserve diversity. | More stable performance (lower standard deviation) in molecular docking vs. basic PSO. | Complex, multimodal problems like flexible molecular docking. |

| CSearch [19] | Population-based (Stochastic) | Chemical Space Annealing with fragment-based virtual synthesis. | 300-400x more computationally efficient than virtual library screening (~80 high-fidelity eval.) [19]. | Optimizing synthesizable molecules for a specific objective function. |

| SIB-SOMO [18] | Population-based (Stochastic) | MIX operation with LB/GB and Random Jump to escape local optima. | Identifies near-optimal solutions (high QED scores) in remarkably short time. | Single-objective molecular optimization in a discrete chemical space. |

| Simplex-based & Principal Directions [11] | Hybrid (Globalized + Local) | Global search via regression on operating parameters, local tuning along principal directions. | Less than eighty high-fidelity EM simulations on average to find an optimal design [11]. | High-dimensional parameter tuning where relationships are regular (e.g., antenna/device tuning). |

Workflow Diagram: A Global Optimization Pipeline for Drug Design

The following diagram outlines a robust workflow that integrates the solutions discussed to address key challenges in drug development.

Global Optimization Pipeline for Drug Design

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Resources for Computational Global Optimization Experiments

| Item | Function in Research | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Fragment Database | Provides building blocks for fragment-based virtual synthesis, ensuring chemical validity and synthesizability. | Curated from commercial collections (e.g., Enamine Fragment Collection) [19]. |

| Reaction Rules (e.g., BRICS) | Defines how molecular fragments can be legally connected, enforcing realistic synthetic pathways. | 16 types of defined reaction points guide the virtual synthesis process [19]. |

| Surrogate Model (GNN) | A fast, approximate predictor for expensive properties (e.g., binding affinity), drastically reducing computational cost. | A GNN trained to approximate GalaxyDock3 docking energies for SARS-CoV-2 MPro, BTK, etc. [19]. |

| Drug-Likeness Metric (QED) | A quantitative score that combines multiple physicochemical properties to gauge compound quality. | Integrates MW, ALOGP, HBD, HBA, PSA, ROTB, AROM, and ALERTS into a single value [18]. |

| High-Fidelity Simulator | Provides the "ground truth" evaluation for final candidate validation after surrogate-guided optimization. | All-atom Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation or precise docking software (e.g., AutoDock) [17] [20]. |

A Practical Guide to Global Optimization Techniques and Their Applications

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the core principles that make Branch-and-Bound (B&B) a deterministic global optimization method?

A1: Branch-and-Bound is an algorithm design paradigm that finds a global optimum by systematically dividing the search space into smaller subproblems and using a bounding function to eliminate subproblems that cannot contain the optimal solution [21]. It operates on two main principles:

- Branching: The original problem's feasible region is recursively split into smaller, manageable sub-regions [21].

- Bounding: For each created sub-region (or "node"), an upper and lower bound for the objective function is computed [21]. A node is discarded (or "pruned") if its lower bound is worse than the best-known upper bound of another node, proving it cannot contain the global optimum [21]. This avoids an exhaustive search of the entire space.

Q2: How does Interval Arithmetic (IA) contribute to achieving guaranteed solutions in B&B frameworks?

A2: Interval Arithmetic provides a mathematical foundation for computing rigorous bounds on functions over a domain [22] [23]. In a B&B context, IA is used for the critical "bounding" step.

- Rigorous Bounds: Instead of point estimates, IA calculates the minimum and maximum possible values a function can take within a given box (sub-region), automatically handling rounding errors [24].

- Guaranteed Pruning: By providing mathematically rigorous lower and upper bounds for each node, IA ensures that no sub-region containing the global optimum is accidentally discarded [22]. This is what provides the "guarantee" of finding a global solution within a specified tolerance.

Q3: My constrained optimization problem converges slowly. What advanced optimality conditions can I use to improve pruning?

A3: For constrained problems, you can implement checks based on the Fritz-John (FJ) or Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) optimality conditions [24].

- Application: These conditions can be formulated as a system of interval linear equations. If, for a given sub-region, this system is proven to have no solution, the node can be pruned because it cannot satisfy the necessary conditions for an optimum [24].

- Performance Consideration: Directly solving the interval FJ system can be challenging due to overestimation. A recommended strategy is to first use a less computationally expensive Geometrical Test to decide whether it is even necessary to compute the full FJ test, thereby improving efficiency [24].

Q4: How can I address the computational expense of Interval B&B for large-scale problems?

A4: Recent research focuses on massive parallelization to tackle this issue.

- GPU Acceleration: A promising approach involves using Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) to parallelize the interval arithmetic computations [23]. The domain of a B&B node can be partitioned into thousands of subdomains, and the interval bounds for the objective and constraints are computed simultaneously on the GPU. This can lead to significantly tighter bounds and a reduction in the number of B&B iterations required, achieving speedups of several orders of magnitude [23].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: The Algorithm is Not Converging or is Too Slow

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Excessively slow convergence; high number of B&B nodes. | Weak bounds leading to insufficient pruning. | Implement a stronger bounding technique. Use the Mean Value Form with domain partitioning via GPU parallelization to calculate tighter interval bounds [23]. |

| Slow convergence on constrained problems. | Inefficient handling of constraints. | Integrate a Fritz-John optimality conditions test. Use a preliminary Geometrical Test to efficiently identify and prune nodes where the FJ conditions cannot hold [24]. |

| General sluggish performance. | Inefficient branching or node management. | Use a best-first search strategy (priority queue sorted on lower bounds) to explore the most promising nodes first [21]. |

Problem 2: Memory Usage is Too High

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Memory overflow during computation. | The queue of active nodes becomes unmanageably large. | Switch to a depth-first search strategy (using a stack). This quickly produces feasible solutions, providing better upper bounds earlier and helping to prune other branches, though it may not find a good bound immediately [21]. |

Problem 3: Inaccurate or Non-Guaranteed Results

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| The solution is not within the final bounds or the guarantee is broken. | Overestimation in interval computations (the "dependency problem"). | Ensure that your implementation uses rigorous interval arithmetic and not floating-point approximations. Reformulate the objective function to minimize variable dependencies where possible. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Basic Branch-and-Bound with Interval Arithmetic for Unconstrained Optimization

This protocol outlines the core steps for solving an unconstrained global optimization problem.

- Initialization: Begin with the entire feasible domain as the initial node. Use a heuristic to find a good initial feasible solution and set the global upper bound

Bto its objective value [21]. - Main Loop: While the candidate queue is not empty:

a. Node Selection: Select and remove a node from the queue according to your strategy (e.g., best-first).

b. Bounding: Calculate a rigorous lower bound (

LB) for the node using interval arithmetic. If the node represents a single point, evaluate it and update the best solution if needed [21]. c. Pruning: IfLB > B, discard the node [21]. d. Branching: If the node was not pruned, split it into two or more smaller sub-regions (e.g., by bisecting the variable with the largest uncertainty). Add these new nodes to the queue [21]. - Termination: Upon completion, the best solution found is guaranteed to be the global optimum within the initial domain. The difference between the best upper bound and the lower bound of the root node provides the optimality guarantee.

Protocol 2: Handling Constrained Optimization with Fritz-John Conditions

This protocol extends the basic B&B framework to problems with constraints.

- Follow Protocol 1 for the general B&B structure.

- For each node, in addition to objective bounding: a. Feasibility Check: Use interval arithmetic to check if the constraint functions can be satisfied within the node. If the interval evaluation of a constraint shows it can never be satisfied, prune the node. b. Geometrical Test (Preliminary): Perform an efficient geometrical check based on the FJ conditions. If this test proves the conditions cannot be satisfied, prune the node [24]. c. Fritz-John System Test: If a node passes the geometrical test, formulate and solve the interval-linear Fritz-John system. If this system is proven to have no solution, prune the node [24].

- Node Evaluation: The bounding step for the objective function must now only consider points that are feasible within the node, which is enabled by the rigorous constraint checks.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the constrained optimization protocol, integrating the Fritz-John tests.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key computational "reagents" and their functions in implementing deterministic global optimization methods.

| Research Reagent | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Interval Arithmetic Library | Provides the core routines for performing rigorous mathematical operations (+, -, ×, ÷) on intervals, ensuring all rounding errors are accounted for [22]. |

| Bounding Function (e.g., Mean Value Form) | A method to calculate upper and lower bounds for the objective and constraint functions over an interval domain. Tighter bounds lead to more pruning and faster convergence [23]. |

| Branching Strategy | The rule that determines how a node (sub-region) is split. A common strategy is to bisect the variable with the widest interval, as it is a major contributor to uncertainty. |

| Node Selection Rule | The strategy for choosing the next node to process from the queue (e.g., best-first for finding good solutions quickly, depth-first for memory efficiency) [21]. |

| Fritz-John/KKT Solver | A computational module that sets up and checks the interval-based Fritz-John or KKT optimality conditions for constrained problems, enabling the pruning of non-optimal nodes [24]. |

| GPU Parallelization Framework | A software layer (e.g., CUDA) that allows for the simultaneous computation of interval bounds on thousands of subdomains, drastically accelerating the bounding step [23]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Genetic Algorithms (GAs)

Q: My Genetic Algorithm is converging to a suboptimal solution too quickly. What is happening and how can I fix it?

A: This is a classic case of premature convergence, often caused by a loss of genetic diversity in the population [25]. You can diagnose and correct this with several strategies:

- Monitor Gene Diversity: Track the variation in your population. A sudden drop in diversity indicates premature convergence [25].

- Adapt Mutation Dynamically: Increase the mutation rate if no fitness improvement is seen for a set number of generations (e.g.,

if (noImprovementGenerations > 30) mutationRate *= 1.2;) [25]. - Inject Random Individuals: Periodically introduce new random chromosomes into the population to help escape local optima [25].

- Use Elitism Sparingly: Limit your elite count to between 1% and 5% of the population size to preserve diversity [25].

- Reevaluate Selection Pressure: Use rank-based selection instead of roulette wheel selection, or reduce tournament size, to prevent a few strong individuals from dominating the gene pool too quickly [25].

Q: How do I choose an appropriate fitness function?

A: A poorly designed fitness function is a common source of failure. Ensure your function [25]:

- Has meaningful gradients to guide the search (avoid flat landscapes).

- Properly penalizes invalid solutions without making them impossible to select.

- Avoids an excessive number of fitness "ties," which makes selection ineffective.

- A bad example is

return isValid ? 1 : 0;A better one isreturn isValid ? CalculateObjectiveScore() : 0.01;[25].

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

Q: What are the key parameters in PSO, and how do I tune them?

A: The three most critical parameters control the balance between exploring the search space and exploiting good solutions found [26].

| Parameter | Description | Typical Range | Effect of a Higher Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inertia Weight (w) | Controls particle momentum; balances exploration vs. exploitation [26]. | 0.4 - 0.9 | Encourages exploration of new areas [26]. |

| Cognitive Constant (c1) | Attraction to the particle's own best-known position (pBest) [26]. | 1.5 - 2.5 | Emphasizes individual experience, increasing diversity [26]. |

| Social Constant (c2) | Attraction to the swarm's global best-known position (gBest) [26]. | 1.5 - 2.5 | Emphasizes social learning, promoting convergence [26]. |

General Tuning Guidelines [26]:

- Start with defaults:

w = 0.7,c1 = 1.5,c2 = 1.5. - Tune one parameter at a time and observe its impact on convergence speed and solution quality.

- For multimodal problems (many local optima), use a higher

w(0.7-0.9) and ac1slightly higher thanc2to maintain diversity. - For unimodal problems (single optimum), use a lower

w(0.4-0.6) and a higherc2to speed up convergence.

Q: I am getting a "dimensions of arrays being concatenated are not consistent" error in my PSO code. What does this mean?

A: This is a common implementation error related to mismatched matrix or vector dimensions during data recording [27]. The error occurs when you try to combine arrays of different sizes into a single row. For example, if your particle position a_opt is a 1x4 row vector, transposing it (a_opt') makes it a 4x1 column vector. You cannot horizontally concatenate this with a scalar Fval [27]. The solution is to ensure all elements you are concatenating have compatible dimensions, often by not transposing row vectors or using vertical concatenation where appropriate [27].

Simulated Annealing (SA)

Q: How do I set the initial temperature and the cooling schedule in Simulated Annealing?

A: The temperature schedule is critical for SA's performance. There is no one-size-fits-all answer, but the following principles apply [28] [29]:

- Initial Temperature (

T0): Start with a temperature high enough that a large proportion (e.g., 80%) of worse moves are accepted. This "melts" the system, allowing free exploration of the search space [29]. - Cooling Schedule: The temperature must be decreased slowly to allow the system to reach equilibrium at each stage. A common method is exponential cooling:

T_new = α * T_old, whereαis a constant close to 1 (e.g., 0.95). Slower cooling (α closer to 1) generally leads to better solutions but takes longer [28] [29]. - Automated Adjustment: One robust strategy is to start with a fast cool-down. If the algorithm gets stuck before reaching the desired cost, "re-melt" the system and restart with a slower cooling rate [29].

Q: Why does my Simulated Annealing algorithm get stuck in local minima even at moderate temperatures?

A: This can happen due to several factors [28] [29]:

- Poor Move Design: The function that generates neighboring states (

neighbour()) may not propose moves that are diverse or large enough to escape certain local optima. Ensure your move set is ergodic, meaning it can eventually reach all possible states [28]. - Overly Rapid Cooling: If the temperature drops too quickly, the algorithm behaves more like greedy hill-climbing and lacks the time to climb out of local minima [28] [29].

- Cost Function Landscape: The choice of cost function itself can create difficult landscapes. A function with a very narrow global minimum or a "flat" landscape with sudden cliffs is hard to optimize. Heuristically weighting different components of the cost function can sometimes help [29].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Diagnosing Premature Convergence in Genetic Algorithms

Purpose: To systematically identify the cause of premature convergence in a GA and apply a targeted correction [25].

Procedure:

- Instrument Your Code: Implement a function to calculate population diversity. For a character-based chromosome, this can be the average number of distinct values per gene position across the population [25].

- Log and Visualize: During each run, log the best fitness, average fitness, and the diversity metric per generation. Plot these values over time.

- Identify the Pattern:

- Symptom: Best fitness plateaus early, and diversity drops rapidly.

- Diagnosis: High selection pressure or insufficient mutation.

- Implement a Fix: Based on the diagnosis, apply one of the strategies from the FAQ above, such as dynamic mutation rates or rank-based selection.

- Test with Determinism: Re-run the algorithm with a fixed random seed (

Random rng = new Random(42)) to ensure the changes produce the desired effect reliably [25].

Protocol: Systematic Parameter Tuning for Particle Swarm Optimization

Purpose: To empirically determine the optimal values for the inertia weight (w), cognitive constant (c1), and social constant (c2) for a specific optimization problem [26].

Procedure:

- Select a Benchmark Function: Choose a well-known function with a known optimum, such as the Sphere function for a unimodal landscape or the Rastrigin function for a multimodal landscape [26].

- Define Parameter Ranges: Set the ranges for your experiment based on established guidelines [26]:

w_values = [0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9]c1_values = [1.5, 1.7, 1.9, 2.1, 2.3, 2.5]c2_values = [1.5, 1.7, 1.9, 2.1, 2.3, 2.5]

- Run Experimental Loop: For each combination of parameters, run the PSO algorithm multiple times (e.g., 20 runs) to account for its stochastic nature [26].

- Record Performance Metrics: For each run, record [26]:

- Best Fitness: The best objective function value found.

- Convergence Speed: The number of iterations required to reach a predefined fitness threshold.

- Analyze Results: Compare the average performance metrics across different parameter sets. Visualize the results using convergence curves (fitness vs. iteration) to understand the swarm's behavior under different settings [26].

Workflow Diagrams

GA Troubleshooting Pathway

PSO Parameter Tuning Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key algorithmic components and their functions, analogous to research reagents in a wet-lab environment.

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Inertia Weight (w) | Balances exploration of new areas vs. exploitation of known good areas in PSO [26]. | Default: 0.7; High (0.9) for exploration, Low (0.4) for exploitation [26]. |

| Cognitive & Social Constants (c1, c2) | Control a particle's attraction to its personal best (c1) and the swarm's global best (c2) [26]. | Keep balanced (c1=c2=1.5-2.0) by default. Adjust to bias towards individual or social learning [26]. |

| Mutation Rate | Introduces random genetic changes, maintaining population diversity in GAs [30]. | Too high: random search. Too low: premature convergence. Can be dynamic [25]. |

| Selection Operator (GA) | Chooses which individuals in a population get to reproduce based on their fitness [30]. | Common methods: Tournament Selection, Roulette Wheel. Rank-based selection reduces premature convergence [25]. |

| Temperature (T) | Controls the probability of accepting worse solutions in Simulated Annealing [28]. | High T: high acceptance rate. T decreases over time according to a cooling schedule [28]. |

| Neighbour Function (SA) | Generates a new candidate solution by making a small alteration to the current one [28]. | Must be designed to efficiently explore the solution space and connect all possible states (ergodicity) [28]. |

| Fitness Function | Evaluates the quality of a candidate solution, guiding the search direction in all algorithms [30]. | Critical design choice. Must provide meaningful gradients and properly penalize invalid solutions [25]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is Bayesian Optimization, and when should I use it? Bayesian Optimization (BO) is a sequential design strategy for globally optimizing black-box functions that are expensive to evaluate and whose derivatives are unknown or do not exist [31] [32]. It is particularly well-suited for optimizing hyperparameters of machine learning models [33], tuning complex system configurations like databases [31], and in engineering design tasks where each function evaluation is resource-intensive [34] [35].

2. How does the exploration-exploitation trade-off work in BO? The trade-off is managed by an acquisition function. Exploitation means sampling where the surrogate model predicts a high objective, while exploration means sampling at locations where the prediction uncertainty is high [32]. The acquisition function uses the surrogate model's predictions to balance these two competing goals [31] [36].

3. My BO algorithm seems stuck in a local optimum. How can I encourage more exploration? You can modulate the exploration-exploitation balance by tuning the parameters of your acquisition function.

- For Expected Improvement (EI), increase the

ξ(xi) parameter [32]. - For Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), increase the

κ(kappa) parameter [33]. - For Probability of Improvement (PI), increase the

ϵ(epsilon) parameter [36]. Increasing these parameters places more weight on exploring uncertain regions, helping the algorithm escape local optima [36] [37].

4. Can Bayesian Optimization handle constraints? Yes, BO can be adapted for problems with black-box constraints. A common approach is to define a joint acquisition function, such as the product of the Expected Improvement (EI) for the objective and the Probability of Feasibility (PoF) for the constraint [38]. This ensures the algorithm samples points that are likely to be both optimal and feasible [37] [38].

5. Which surrogate model should I choose for my problem? The choice depends on the nature of your problem and input variables [31].

- Gaussian Process (GP) is the default choice for continuous parameters, providing good uncertainty estimates and performing well with few data points [34] [32].

- Random Forest or Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) are often faster and can be better suited for categorical or high-dimensional parameter spaces [31] [33].

6. How should I select the initial points for the optimization? It is recommended to start with an initial set of points (often 5-10) sampled using a space-filling design like Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) or simple random sampling [38] [33]. These initial points help build the first version of the surrogate model before the Bayesian Optimization loop begins [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: The Optimization is Converging Too Slowly

Problem: The algorithm requires a very large number of iterations to find a good solution, making the process inefficient.

Solution: Check and adjust the following components:

- Acquisition Function: Switch to Expected Improvement (EI), as it often provides a better balance of exploration and exploitation compared to Probability of Improvement (PI) because it considers the amount of improvement, not just the probability [36] [33].

- Initial Points: Increase the number of initial points (

init_pointsornum_initial_points) to ensure the surrogate model has a better initial understanding of the search space [39] [33]. - Surrogate Model Kernel: If using a Gaussian Process, ensure the kernel function matches the smoothness properties of your objective function. The Matérn 5/2 kernel is a robust default choice [32] [37].

Issue 2: Handling Noisy Objective Function Evaluations

Problem: Evaluations of the black-box function return noisy (stochastic) results, which can mislead the surrogate model.

Solution: Incorporate a noise model directly into the surrogate model.

- For a Gaussian Process, you can explicitly model the noise by specifying and fitting a noise variance parameter (often called

alphaorlikelihood.variance) [31] [32] [37]. - When using the Expected Improvement acquisition function with a noisy objective, base the improvement not on the noisy best observation, but on the best value of the posterior mean [32]. The formula for EI remains the same, but

f(x+)is replaced byμ(xbest).

Issue 3: Optimization with Mixed Parameter Types (Continuous, Integer, Categorical)

Problem: Your search space contains a mix of continuous, integer, and categorical parameters, which is challenging for standard Gaussian Process models.

Solution: Use a Bayesian Optimization framework that supports mixed parameter types.

- Libraries like Ax and BayesianOptimization.py have built-in support for defining different parameter types [34] [39].

- For categorical parameters, use a surrogate model designed for them, such as Random Forest or specify a dedicated kernel for categorical variables in a GP [31] [39].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Common Acquisition Functions

This table will help you select the most suitable acquisition function for your experimental goals [31] [36] [37].

| Acquisition Function | Mathematical Definition | Best For | Key Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expected Improvement (EI) | EI(x) = (μ(x) - f(x+) - ξ)Φ(Z) + σ(x)ϕ(Z) |

General-purpose optimization; considers improvement magnitude [32]. | ξ (xi): Controls exploration; higher values encourage more exploration [32]. |

| Probability of Improvement (PI) | PI(x) = Φ( (μ(x) - f(x+) - ϵ) / σ(x) ) |

Quickly finding a local optimum when exploration is less critical [36]. | ϵ (epsilon): Margin for improvement; higher values encourage exploration [36]. |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | UCB(x) = μ(x) + κ * σ(x) |

Explicit and controllable balance between mean and uncertainty [31]. | κ (kappa): Trade-off parameter; higher values favor exploration [33]. |

Table 2: Common Optimization Errors and Diagnostics

A guide to diagnosing issues during your Bayesian Optimization experiments.

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Step | Suggested Fix |

|---|---|---|---|

| The model consistently suggests nonsensical or poor-performing parameters. | The surrogate model has failed to learn the objective function's behavior. This could be due to an incorrect kernel choice or the model getting stuck in a bad local configuration during fitting [32]. | Check the model's fit on a held-out set of points or visualize the mean and confidence intervals against the observations. | Restart the optimization with different initial points or switch the kernel function (e.g., to Matérn 5/2) [37]. |

| The algorithm keeps sampling in a region known to be sub-optimal. | The acquisition function is over-exploiting due to low uncertainty in other regions [37]. | Plot the acquisition function over the search space to see if it has a high value only in the sub-optimal region. | Increase the exploration parameter (ξ, κ, or ϵ) of your acquisition function [36] [37]. |

| Optimization results have high variance between runs. | The objective function might be very noisy, or the initial random seed has a large impact. | Run the optimization several times with different random seeds and compare the performance distributions. | Increase the number of initial points. For a noisy function, ensure your surrogate model (e.g., GP) is correctly modeling the noise level [31] [32]. |

Core Bayesian Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the iterative cycle that forms the foundation of the Bayesian Optimization algorithm [31] [32] [37].

Acquisition Function Comparison Logic

This diagram outlines the decision-making logic an experimenter can use to select an appropriate acquisition function [31] [36] [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential "research reagents"—the core algorithmic components and software tools—required to set up and run a Bayesian Optimization experiment.

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example Options & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Surrogate Model | Approximates the expensive black-box function; provides a probabilistic prediction (mean and uncertainty) for unobserved points [31] [32]. | Gaussian Process (GP): Default for continuous spaces; provides good uncertainty quantification [34]. Random Forest / TPE: Faster, good for categorical/mixed spaces [31] [33]. |

| Acquisition Function | Guides the selection of the next point to evaluate by balancing exploration and exploitation [31] [36]. | Expected Improvement (EI): Most widely used; balances probability and magnitude of improvement [32]. Upper Confidence Bound (UCB): Good when explicit control over exploration is needed [33]. |

| Optimization Library | Provides implemented algorithms, saving time and ensuring correctness. | Ax: From Meta; suited for large-scale, adaptive experimentation [34]. BayesianOptimization.py: Pure Python package for global optimization [39]. KerasTuner: Integrated with Keras/TensorFlow for hyperparameter tuning [33]. |

| Domain Definition | Defines the search space (bounds) for the parameters to be optimized. | Must specify minimum and maximum values for each continuous parameter and available choices for categorical parameters [39]. |

| Initial Sampling Strategy | Generates the first set of points to build the initial surrogate model. | Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS): Ensures good space-filling properties [38]. Random Sampling: Simple default option [37]. |

Clinical trials face unprecedented challenges, including recruitment delays affecting 80% of studies, escalating costs exceeding $200 billion annually in pharmaceutical R&D, and success rates below 12% [40]. In this context, model-informed drug development (MIDD) and clinical trial simulation represent transformative approaches grounded in sophisticated optimization principles.

These methodologies apply global optimization methods to navigate complex biological parameter spaces, enabling researchers to identify optimal trial designs, dosage regimens, and patient populations before enrolling a single participant. The integration of these computational approaches has demonstrated potential to accelerate trial timelines by 30-50% while reducing costs by up to 40% [40].

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the fundamental difference between local and global optimization in clinical trial simulation?

Local optimization methods (e.g., gradient-based algorithms) efficiently find nearby solutions but often become trapped in suboptimal local minima when dealing with complex, multi-modal parameter landscapes. Global optimization methods (e.g., evolutionary strategies, Bayesian optimization) explore broader parameter spaces to identify potentially superior solutions, making them particularly valuable for trial design optimization where the response surface may be discontinuous or poorly understood [41]. For clinical trial design, global methods have demonstrated ∼95% success rates in registration problems compared to local methods that frequently fail with complex parameter interactions [41].

How can we validate that our simulation model accurately represents real-world biological systems?

Model validation requires a multi-faceted approach: (1) Internal validation using historical clinical data to compare predicted versus actual outcomes; (2) External validation with independent datasets not used in model development; (3) Predictive validation where the model forecasts outcomes for new trial designs later verified through actual studies [42] [43]. The FDA's MIDD program has accepted physiological based pharmacokinetic modeling to obtain 100 novel drug label claims in lieu of clinical trials, primarily for drug-drug interactions [43].

What are the computational resource requirements for implementing these optimization methods?

Computational requirements vary significantly by approach. Bayesian optimization frameworks like Ax can typically identify optimal configurations within 80-200 high-fidelity evaluations for complex problems [11] [34]. For large-scale global optimization of multi-parameter systems, techniques utilizing variable-resolution simulations can reduce computational costs by employing low-fidelity models for initial exploration and reserving high-resolution analysis only for promising candidate solutions [11].

How do we balance exploration versus exploitation in adaptive trial designs?

Effective balance requires: (1) Defining explicit allocation rules based on accumulating efficacy and safety data; (2) Implementing response-adaptive randomization algorithms that automatically shift allocation probabilities toward better-performing arms; (3) Setting pre-specified minimum allocation percentages to maintain exploration of potentially promising but initially underperforming options [44]. Multi-objective optimization approaches can simultaneously optimize for information gain (exploration) and patient benefit (exploitation) [34].

What safeguards prevent over-fitting in complex simulation models?

Key safeguards include: (1) Regularization techniques that penalize model complexity during parameter estimation; (2) Cross-validation using held-out data not included in model training; (3) Pruning of unnecessary parameters without affecting performance; (4) Establishing domain-informed constraints based on biological plausibility [6]. These techniques help maintain model generalizability while still capturing essential system dynamics.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Simulation results do not align with preliminary clinical observations

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient model granularity: Refine physiological compartments or incorporate additional disease progression mechanisms [42]

- Inaccurate parameter estimation: Recalibrate using available preclinical and early-phase clinical data [45]

- Missing covariate relationships: Incorporate demographic, genomic, or comorbidity factors that influence treatment response [40]