From Single Targets to Complex Networks: How Systems Biology is Revolutionizing Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between traditional reductionist and modern systems biology approaches in biomedical research and drug development.

From Single Targets to Complex Networks: How Systems Biology is Revolutionizing Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between traditional reductionist and modern systems biology approaches in biomedical research and drug development. It explores the foundational principles of each paradigm, detailing the methodological shift from single-target investigation to network-based analysis. The content covers practical applications of systems biology in identifying drug targets, optimizing combinations, and stratifying patients, while also addressing the computational and experimental challenges inherent in modeling complex biological systems. Through comparative analysis of clinical translation success and efficacy in tackling complex diseases, the article demonstrates how systems biology provides a more holistic framework for understanding disease mechanisms and developing effective therapeutics. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current evidence to highlight both the transformative potential and ongoing limitations of systems biology in advancing precision medicine.

Reductionism vs Holism: Paradigm Shifts in Biological Research

The traditional reductionist approach has been the predominant paradigm in biological science and medicine for centuries. Rooted in the Cartesian method of breaking complex problems into smaller, simpler, and more tractable units, reductionism operates on the fundamental assumption that understanding individual components in isolation is sufficient to explain the behavior of the whole system [1] [2]. In practice, this means that biological organisms are treated as collections of distinct parts, with the expectation that by deconstructing a system to its molecular foundations—genes, proteins, and pathways—we can ultimately reconstruct and comprehend its complete functioning. This "divide and conquer" strategy has driven tremendous successes in modern medicine, enabling the identification of specific pathogens responsible for infections, the development of targeted therapies, and the meticulous mapping of linear metabolic pathways [2].

However, the reductionist worldview carries inherent limitations in its conceptualization of biological organization. By focusing on a singular, dominant factor for each disease state, emphasizing static homeostasis over dynamic regulation, and employing additive treatments for multiple system dysfunctions, reductionism often neglects the complex interplay between components that yields emergent behaviors unpredicted by investigating parts in isolation [2]. As molecular biology has evolved into the post-genomic era, the shortcomings of this exclusively reductionist perspective have become increasingly apparent when confronting multifactorial diseases and complex phenotypic traits that cannot be explained by single genetic mutations or linear causal pathways [1] [3]. The very success of reductionism in cataloging biological components has revealed the necessity of complementary approaches that can address system-wide behaviors arising from dynamic interactions.

Core Principles and Methodologies

Fundamental Tenets of Reductionism

Reductionist biology is characterized by several interconnected principles that guide its application in research and medicine. First, it maintains that complex biological phenomena can be fully explained through the properties of their constituent molecular components, implying a direct determinism between molecular states and system outcomes [1]. This principle manifests experimentally through the isolation of single variables under controlled conditions to establish causal relationships, with the expectation that biological behavior is linear, predictable, and deterministic rather than stochastic or emergent [1]. The approach further assumes that multiple system problems can be addressed through additive treatments—solving each issue individually without accounting for complex interplay between interventions [2]. Finally, reductionism conceptualizes biological regulation through the lens of static homeostasis, emphasizing the maintenance of physiological parameters within normal ranges rather than dynamic stability achieved through continuous adaptation [2].

Characteristic Methodological Framework

The experimental implementation of reductionism follows a consistent pattern across biological disciplines. The central method involves controlled manipulation of individual components—whether genes, proteins, or pathways—to reveal their specific functions within cells or organisms [4]. These manipulations typically employ strong experimental perturbations, such as gene knockouts or pharmacological inhibition, that "vex nature" by isolating component function from its systemic context [4]. The analysis then focuses on predefined, limited readouts rather than comprehensive system monitoring, building knowledge incrementally by studying one component or pathway at a time [4]. This methodological framework has proven exceptionally powerful for establishing causal relationships in signaling pathways and genetic networks, though it necessarily simplifies the complexity of intact biological systems operating under physiological conditions.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of the Traditional Reductionist Approach

| Aspect | Reductionist Perspective |

|---|---|

| System Behavior | Explained by properties of individual components [1] |

| Experimental Approach | Focus on one factor or limited number of factors [1] |

| Causal Relationships | Directly determining factors; linear causality [1] |

| Model Characteristics | Linearity, predictability, determinism [1] |

| Metaphor | Machine/magic bullet [1] |

| Homeostasis | Static maintenance of normal ranges [2] |

| Treatment Strategy | Additive interventions for multiple problems [2] |

Experimental Protocols in Reductionist Research

High-Throughput Behavioral Fingerprinting in Drosophila melanogaster

A contemporary example of reductionist methodology can be found in behavioral neuroscience using model organisms. The "coccinella" framework for Drosophila melanogaster represents a sophisticated reductionist approach to ethomics (high-throughput behavioral analysis) [5]. This protocol employs a distributed mesh of ethoscopes—open-source devices combining Raspberry Pi microcomputers with Raspberry Pi NoIR cameras—to track individual flies in custom-designed arenas. The system operates in real-time tracking mode, analyzing images at the moment of acquisition with a temporal resolution of one frame every 444±127 milliseconds (equivalent to 2.2 fps) at a resolution of 1280×960 pixels [5].

The experimental workflow begins with housing individual flies in circular arenas (11.5mm diameter) containing solidified agar with nutrients alone (control) or nutrients combined with compounds of interest. Animals move freely in a two-dimensional space designed to maintain walking position. The system extracts a minimalist behavioral parameter—maximal velocity over 10-second intervals—creating a monodimensional time series as a behavioral correlate [5]. This data is then processed using Highly Comparative Time-Series Analysis (HCTSA), a computational framework that applies over 7,700 statistical tests to identify discriminative features [5]. Finally, these features enable behavioral classification through machine learning algorithms like linear support vector machines (SVMlinear), creating behavioral fingerprints for different pharmacological treatments [5].

The strength of this reductionist approach was demonstrated through pharmacobehavioral profiling of 17 treatments (16 neurotropic compounds plus solvent control). The system achieved 71.4% accuracy in distinguishing compounds based solely on velocity time-series data, significantly outperforming random classification (5.8%) [5]. Notably, some compounds like dieldrin were identified with 94% accuracy, validating that meaningful biological discrimination can be achieved even with minimalist behavioral representation.

Target-Centric Drug Discovery

In pharmaceutical research, reductionist protocols typically focus on identifying and validating single protein targets followed by developing compounds that modulate their activity. The standard workflow begins with target identification through genetic association studies (e.g., genome-wide association studies), gene expression profiling of diseased versus healthy tissue, or analysis of protein-protein interactions [6]. Candidate targets are then validated using gain-of-function and loss-of-function experiments in cellular models, employing techniques like RNA interference, CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, or overexpression systems [3].

Successful target validation leads to high-throughput screening of compound libraries against the purified target protein or cellular pathway, typically measuring a single readout such as binding affinity, enzymatic activity, or reporter gene expression [6]. Hit compounds are optimized through structure-activity relationship studies that systematically modify chemical structure to enhance potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties [6]. Finally, lead compounds undergo efficacy testing in animal models that measure predefined endpoints related to the specific target pathway, followed by safety assessment in toxicology studies focusing on standard parameters [6].

This reductionist drug discovery paradigm has produced numerous successful therapeutics, particularly for diseases with well-defined molecular pathologies. However, its limitations become apparent when addressing complex, multifactorial diseases where single-target modulation proves insufficient to reverse pathological states [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents in Reductionist Biological Research

| Reagent/Category | Function in Reductionist Research |

|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Targeted gene editing for loss-of-function and gain-of-function studies [3] |

| RNAi Libraries | Gene silencing for systematic functional screening [3] |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Specific protein detection, quantification, and inhibition [6] |

| Chemical Inhibitors/Agonists | Pharmacological manipulation of specific protein targets [5] |

| Reporter Constructs | Measurement of pathway activity through fluorescent or luminescent signals [6] |

| knockout Model Organisms | Investigation of gene function in intact biological systems [3] |

| siRNA/shRNA | Transient or stable gene silencing in cellular models [6] |

| Recombinant Proteins | In vitro studies of protein function and compound screening [6] |

| Cervinomycin A2 | Cervinomycin A2, CAS:82658-22-8, MF:C29H21NO9, MW:527.5 g/mol |

| Revospirone | Revospirone|5-HT1A Receptor Agonist|RUO |

Reductionism in the Context of Systems Biology

Philosophical and Methodological Contrast

The emergence of systems biology represents both a complement and challenge to traditional reductionism. Where reductionism seeks to explain biological phenomena by breaking systems into constituent parts, systems biology aims to understand how these parts interact to produce emergent behaviors [1]. This fundamental difference in perspective leads to distinct methodological approaches: reductionism focuses on one or few factors in isolation, while systems biology considers multiple factors simultaneously in dynamic interaction [1]. The metaphors differ significantly—reductionism views biological systems as machines with replaceable parts, while systems biology employs network metaphors emphasizing connectivity and interdependence [1].

The conceptualization of causality further distinguishes these approaches. Reductionism posits direct, linear causal relationships where manipulating a component produces predictable, proportional effects [1]. In contrast, systems biology recognizes nonlinear relationships where effects may be disproportionate to interventions and highly dependent on system context and state [1]. Similarly, where reductionism emphasizes static homeostasis maintained through negative feedback, systems biology incorporates dynamic stability concepts including oscillatory behavior and chaotic dynamics that remain stable despite apparent variability [2] [4].

Convergence and Complementarity

Despite their philosophical differences, reductionist and systems approaches are increasingly recognized as complementary rather than mutually exclusive [3]. Reductionist methods provide the essential component-level understanding that forms the foundation for systems modeling, while systems perspectives help contextualize reductionist findings within integrated networks [3]. Modern biological research often employs iterative cycles between these approaches—using reductionist methods to characterize individual elements, systems approaches to identify emergent properties, and further reductionist experiments to mechanistically test hypotheses generated from systems-level observations [3] [4].

This convergence is particularly evident in the analysis of complex traits, where forward genetics (reductionist) and network approaches (systems) together provide more complete understanding than either could alone [3]. Similarly, in drug discovery, target-based approaches (reductionist) and network pharmacology (systems) are increasingly integrated to address the limitations of single-target therapies for complex diseases [7] [6]. The combination of detailed molecular knowledge from reductionism with holistic perspectives from systems biology offers a more comprehensive path toward understanding biological complexity.

Comparative Analysis: Key Differences and Applications

Table 3: Reductionist versus Systems Approaches in Biological Research

| Research Aspect | Reductionist Approach | Systems Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Individual components in isolation [1] | System as a whole and interactions between components [1] |

| Experimental Design | Controlled manipulation of single variables [1] | Multiple simultaneous measurements under physiological conditions [8] |

| Data Type | Limited, predefined readouts [4] | High-dimensional omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) [8] [7] |

| Model Characteristics | Linear, deterministic, predictable [1] | Nonlinear, stochastic, sensitive to initial conditions [1] |

| Causal Interpretation | Direct, linear causality [1] | Emergent properties from network interactions [1] |

| Treatment Paradigm | Single-target therapies [7] | Multi-target, combination therapies [7] |

| Health Conceptualization | Static homeostasis, normal ranges [2] | Robustness, adaptability, homeodynamics [1] |

| Strengths | Establishing causal mechanisms, target identification [3] [6] | Understanding complex diseases, predicting emergent effects [8] [7] |

| Limitations | Poor prediction of system behavior, overlooking compensatory mechanisms [2] [4] | Complexity of models, requirement for large datasets, challenging validation [8] [4] |

The traditional reductionist approach has provided the foundational methodology for modern biological research, enabling tremendous advances in understanding molecular mechanisms underlying health and disease. Its power to establish clear causal relationships through controlled manipulation of isolated components remains indispensable for mechanistic inquiry. However, the limitations of reductionism become apparent when confronting biological complexity—where emergent properties arise from dynamic interactions that cannot be predicted from studying individual components alone [1] [4].

The ongoing convergence of reductionist and systems approaches represents the most promising path forward for biological research [3]. Reductionism continues to provide essential component-level understanding and methodological rigor, while systems biology offers frameworks for integrating this knowledge into network models that better reflect biological reality [3] [4]. This synergy is particularly valuable in drug discovery, where the combination of target-based approaches and network pharmacology may overcome limitations of single-target therapies for complex diseases [7] [6]. Rather than representing competing paradigms, reductionism and systems biology increasingly function as complementary perspectives, each necessary for a complete understanding of biological organization across scales.

Reductionist Research Workflow

Systems Biology Research Workflow

The study of biology has undergone a fundamental transformation with the emergence of systems biology, representing a significant departure from traditional reductionist approaches. Where traditional biology has excelled at isolating and examining individual components—single genes, proteins, or pathways—systems biology investigates how these components interact to produce emergent behaviors that cannot be predicted from studying parts in isolation [9]. This paradigm shift recognizes that biological networks, from intracellular signaling pathways to entire ecosystems, exhibit properties that arise from the complex, non-linear interactions between their constituent parts [10] [9].

The foundation of systems biology rests upon the core principle that "the whole is more than the sum of its parts," a concept known as emergence [10]. This approach has become increasingly vital as technologies generate vast amounts of high-resolution data characterizing biological systems across multiple scales, from molecules to entire organisms [11]. By integrating quantitative measurements, computational modeling, and engineering principles, systems biology provides a framework for understanding how evolved systems are organized and how intentional synthesis of biological systems can be achieved [12] [9].

Core Principles of Systems Biology

Emergence as a Foundational Concept

Emergence describes the phenomenon where complex patterns, properties, or behaviors arise from interactions among simpler components [10]. In biological systems, emergent properties manifest across all scales of organization:

- Cellular Level: Individual neurons transmit electrical impulses, but consciousness, cognition, and memory emerge only when billions connect to form neural networks [10].

- Organismal Level: Heart tissues individually cannot pump blood, but their coordinated organization produces the emergent property of rhythmic contraction [10].

- Social Level: Individual ants follow simple behavioral rules, but colonies collectively exhibit intelligent problem-solving and complex construction abilities [10].

Professor Michael Levin's research on xenobots—programmable living organisms constructed from frog cells—demonstrates emergence in action. These cell assemblies exhibit movement, self-repair, and environmental responsiveness without any neural circuitry, their behaviors emerging purely from cellular interactions and organization [10].

Key Drivers of Emergent Properties

Several interconnected principles govern how emergent properties arise in biological networks:

- Interactions: Emergence depends on communication between components, whether through electrical and chemical signals in neural networks or bioelectric gradients guiding cellular decision-making [10].

- Self-Organization: Biological systems often structure themselves without external instructions, as seen in bird flocking or cellular self-organization guided by bioelectric cues [10].

- Hierarchies of Organization: Life operates through nested hierarchies from molecules to organisms, with higher-level properties emerging from lower-level interactions [10].

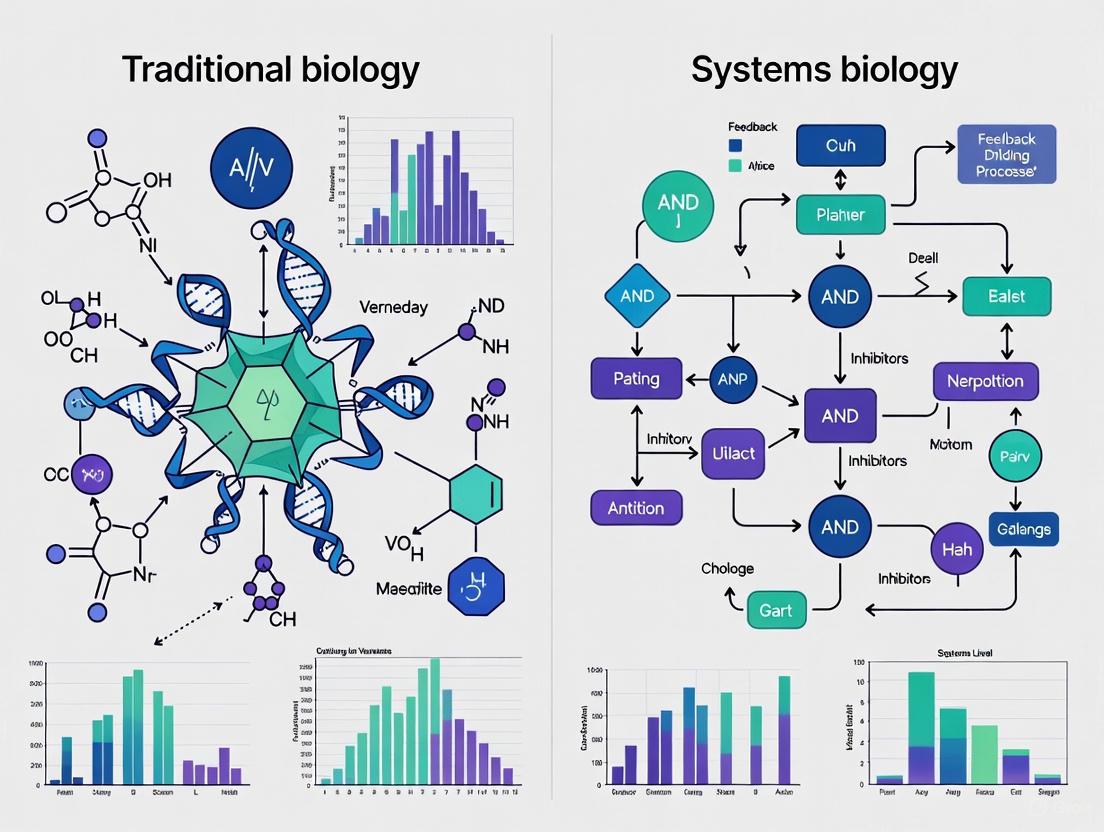

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. Systems Biology Approaches

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Traditional and Systems Biology Approaches

| Aspect | Traditional Biology | Systems Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Individual components (genes, proteins) | Networks and interactions between components [9] |

| Methodology | Qualitative description, hypothesis-driven | Quantitative measurement, modeling, hypothesis-generating [13] [9] |

| Scope | Isolated pathways or processes | Multi-scale integration from molecules to organisms [11] [13] |

| Data Type | Low-throughput, targeted measurements | High-throughput 'omics' data (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) [13] [9] |

| Understanding | Mechanism of specific elements | Emergent system properties and dynamics [10] [9] |

| Modeling Approach | Minimal use of mathematical models | Essential dependency on computational models [13] [9] |

Table 2: Analytical Outputs and Capabilities Comparison

| Output Capability | Traditional Biology | Systems Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Predictive Power | Limited to direct linear relationships | Predictive for complex, non-linear behaviors [13] |

| Treatment Development | Target-specific drugs, often with limited efficacy | Network pharmacology, multi-target therapies [13] |

| Disease Understanding | Single-factor causation | Multi-factorial, network-based dysfunction [13] |

| Experimental Design | One-variable-at-a-time | Multi-perturbation analyses [9] |

| Time Resolution | Static snapshots | Dynamic, temporal modeling [13] [9] |

Experimental Frameworks in Systems Biology

Methodological Pillars

Systems immunology exemplifies the systems biology approach through several methodological pillars [13]:

- Network Pharmacology: Examining drug effects within the context of interconnected biological pathways rather than isolated targets [13].

- Quantitative Systems Pharmacology: Integrating pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modeling with systems biology to optimize therapeutic strategies [13].

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: Extracting patterns from high-dimensional data to predict immune responses, identify biomarkers, and discover novel pathways [13].

Representative Experimental Protocol

A typical systems biology investigation involves an integrated workflow that combines high-throughput data collection with computational modeling:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Technologies in Systems Biology

| Reagent/Technology | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Single-cell RNA sequencing | Resolution of cellular heterogeneity and rare cell states [13] | Identification of novel immune cell subtypes in disease [13] |

| Mass cytometry (CyTOF) | High-dimensional protein measurement at single-cell level [13] | Immune cell profiling in autoimmune conditions [13] |

| Bioelectric signaling tools | Measurement and manipulation of cellular electrical gradients [10] | Studying pattern formation in development and regeneration [10] |

| CRISPR-based perturbations | High-throughput functional screening of genetic elements [14] | Mapping genetic interaction networks [14] |

| Mathematical modeling frameworks | Quantitative representation of system dynamics [13] [9] | Predicting immune response outcomes to pathogens [13] |

| AI/ML algorithms | Pattern recognition in high-dimensional data [13] | Biomarker discovery and treatment response prediction [13] |

| Lusianthridin | Lusianthridin, CAS:87530-30-1, MF:C15H14O3, MW:242.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mensacarcin | Mensacarcin, MF:C21H24O9, MW:420.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Case Study: Systems Immunology in Therapeutic Development

The immune system exemplifies biological complexity, comprising approximately 1.8 trillion cells utilizing around 4,000 distinct signaling molecules [13]. This complexity makes it particularly suited for systems biological approaches. Systems immunology has emerged as a distinct field that integrates omics technologies with computational modeling to predict immune system behavior and develop more effective treatments [13].

Application to Disease Research

Systems immunology approaches have transformed our understanding of immune-related diseases:

- Autoimmune Diseases: Multi-omics data integrated with ML models have improved diagnostics and identified novel pathways in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases [13].

- Cancer Immunotherapy: AI models analyze complex tumor-immune interactions to predict treatment responses and identify resistance mechanisms [13].

- Vaccine Development: Systems approaches have been used to predict vaccine responsiveness since pioneering studies on the Yellow Fever vaccine [13].

Systems biology represents not a replacement for traditional biological approaches but rather an essential complement. While reductionist methods continue to provide crucial insights into molecular mechanisms, systems biology offers the framework to understand how these mechanisms integrate to produce emergent behaviors [10] [9]. The future of biological research lies in leveraging both approaches: using traditional methods to characterize individual components and systems approaches to understand their integrated functions.

As technological advances continue to generate increasingly detailed quantitative measurements, the role of systems biology will expand further, potentially enabling predictive biology and personalized therapeutic interventions [11] [13] [9]. This integration of approaches promises to unlock deeper insights into the emergent properties that characterize living systems across all scales of biological organization.

The field of biology has undergone a profound conceptual transformation, evolving from a reductionist perspective that viewed biological systems as precise, predictable machinery to a holistic paradigm that embraces complexity, dynamics, and interconnectedness. This shift from mechanical clockwork metaphors to holistic systems thinking represents a fundamental change in how researchers approach biological investigation, particularly in drug discovery and development. The traditional reductionist approach, which dominated 20th-century biology, focused on deconstructing living systems into their component parts—genes, proteins, cells—with the belief that complete understanding would emerge from characterizing these individual elements [15]. This perspective was exemplified by the clockwork metaphor, which depicted biological systems as mechanical assemblies governed by specific rules and mechanisms, predictable in their operations once understood [16].

In contrast, modern systems biology recognizes that "nothing in the living world happens in a vacuum" and that "no life processes proceed in isolation" [15]. This holistic approach acknowledges that biological functions emerge from complex, dynamic networks of interacting components that are highly regulated and adaptive. The transition between these paradigms was driven by multiple factors: the completion of the human genome project, the development of high-throughput technologies generating massive molecular datasets, exponential growth in computational power, and advocacy by influential researchers [15]. This evolution has fundamentally transformed research methodologies, analytical frameworks, and conceptual models across biological sciences, particularly impacting how researchers approach disease mechanisms and therapeutic development.

Metaphorical Evolution: From Clockwork to Complex Systems

The changing landscape of biological thought is reflected in the metaphors used to describe and explain biological systems. These metaphors provide conceptual frameworks that shape research questions, methodologies, and interpretations.

Traditional Mechanical Metaphors

The clockwork metaphor dominated traditional biological thinking, comparing biological systems to precise, predictable mechanical devices like clocks [16]. This perspective emphasized linear causality, determinism, and decomposability—the assumption that system behavior could be fully understood by analyzing individual components in isolation. Related mechanical metaphors included the domino effect, illustrating simple linear causality where one event triggers another in a predictable sequence [16]. These metaphors supported a reductionist approach that has been enormously successful in cataloging biological components but ultimately insufficient for explaining emergent biological functions.

Modern Systems Metaphors

Contemporary biology employs more sophisticated metaphors that better capture the complexity of living systems:

- The Iceberg Metaphor: Represents biological systems as having only a small portion of observable elements above the surface, while most underlying dynamics, feedback loops, and structures remain hidden beneath [16].

- The Ecosystem Metaphor: Emphasizes interdependency, feedback loops, and resilience through comparing biological systems to ecological networks where multiple elements interact in complex ways [16].

- The Network Metaphor: Highlights the interconnected nature of biological components, emphasizing concepts like nodes, links, and network effects [16].

- The Organism Metaphor: Compares systems to living organisms where parts are analogous to organs and their interactions create emergent functions [16].

- The Butterfly Effect: Illustrates how small changes in one part of a system can create significant, unpredictable effects elsewhere, capturing the nonlinearity of biological systems [16].

These evolving metaphors reflect a fundamental reconceptualization of biological systems from deterministic machinery to complex, adaptive networks with emergent properties that cannot be fully understood through reductionist approaches alone.

Methodological Comparison: Traditional versus Systems Approaches

The paradigm shift from reductionist to holistic thinking has manifested in distinct methodological approaches to biological research and drug discovery. The table below summarizes key differences between these frameworks:

Table 1: Methodological Comparison of Traditional and Systems Biology Approaches

| Aspect | Traditional Biology Approaches | Systems Biology Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Perspective | Reductionist; focuses on individual components | Holistic; focuses on system interactions and networks |

| Primary Methodology | Isolated study of linear pathways | Network analysis; integration of multi-omics data |

| Modeling Approach | Qualitative descriptions; limited mathematical formalization | Quantitative mathematical models (ODEs, PDEs, Boolean networks) |

| Typical Data Collection | Targeted measurements of single molecular types | High-throughput multi-omics datasets (genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic) |

| Time Considerations | Often static snapshots | Dynamic measurements over time |

| Regulatory Focus | Limited feedback considerations | Comprehensive analysis of feedback and feedforward loops |

| Representative Metaphor | Clockwork, domino effect | Iceberg, ecosystem, network, butterfly effect |

| Drug Discovery Application | Single-target therapies | Network pharmacology; polypharmacology |

Traditional approaches typically investigated single genes or proteins through tightly controlled experiments that isolated specific pathways from their broader context [17]. In contrast, systems biology employs high-throughput technologies such as microarrays, mass spectrometry, and next-generation sequencing to generate global, multi-omics datasets that capture information across multiple biological levels simultaneously [17] [6]. The systems approach recognizes that "most biological features are determined by complex interactions among a cell's distinct components" rather than by single molecules in isolation [17].

Modeling Frameworks: From Qualitative to Quantitative Representations

The transition from traditional to systems approaches has introduced sophisticated mathematical and computational modeling frameworks to biological research. These frameworks enable researchers to simulate and predict system behavior under different conditions and perturbations.

Qualitative Modeling Approaches

Boolean network models represent a fundamental qualitative approach where biological entities are characterized by binary variables (ON/OFF) and their interactions are expressed using logic operators (AND, OR, NOT) [18]. These models require few or no kinetic parameters and provide coarse-grained descriptions of biological systems, making them particularly valuable when mechanistic details or kinetic parameters remain unknown [18]. The piecewise affine differential equation models (also called hybrid models) occupy a middle ground, combining logical descriptions of regulatory relationships with continuous concentration decay [18]. These models are suitable for systems with partial knowledge of parameter values and have been widely used in literature [18].

Quantitative Modeling Approaches

Quantitative models, usually implemented as sets of differential equations, are considered the most appropriate dynamic approaches for modeling real biological systems [18]. Among these, Hill-type models have been successfully employed in modeling specific signaling networks [18]. In these models, the production rate of a species is modeled by a Hill function and the degradation rate is considered linear, capturing the sigmoid response curves common in biological systems [18]. Quantitative models provide detailed information about real-valued attractors and system dynamics not available in qualitative approaches [18].

Table 2: Comparison of Dynamic Modeling Approaches in Biological Research

| Model Type | Key Characteristics | Data Requirements | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boolean Models | Binary variables (ON/OFF); logical interactions | Minimal parameters; network topology | Large-scale networks; initial exploratory modeling |

| Piecewise Affine (Hybrid) Models | Combines logical regulation with continuous decay | Partial parameter knowledge; threshold values | Systems with some quantitative data available |

| Hill-Type Continuous Models | Ordinary differential equations with sigmoid functions | Kinetic parameters; detailed mechanistic knowledge | T-cell receptor signaling; cardiac β-adrenergic signaling |

| Network Models | Nodes and edges representing biological entities | Interaction data; omics datasets | Disease pathway mapping; drug target identification |

The integration of these modeling approaches enables researchers to translate between different levels of biological abstraction, from qualitative understanding to quantitative prediction [18]. Comparative studies have shown that while fixed points of asynchronous Boolean models are observed in continuous Hill-type and piecewise affine models, these models may exhibit different attractors under certain conditions [18].

Experimental Design and Protocols in Systems Biology

Systems biology employs distinctive experimental designs that differ significantly from traditional biological approaches. These protocols emphasize comprehensive data collection, integration across biological levels, and computational validation.

Core Workflow for Systems Biology Investigation

The following diagram illustrates a generalized experimental workflow in systems biology research:

Diagram 1: Systems Biology Research Workflow

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Network Reconstruction and Analysis Protocol

Purpose: To reconstruct biological networks from high-throughput data and identify key regulatory components. Methodology:

- Data Collection: Generate genome-wide datasets using appropriate technologies (RNA-Seq, mass spectrometry, etc.) [6].

- Network Construction: Build interaction networks using:

- Topological Analysis: Identify network properties using tools like Cytoscape with plugins for advanced analysis [17].

- Functional Annotation: Annotate networks with functional information using enrichment analysis and Gene Ontology [17].

- Hub Identification: Identify "party hubs" (simultaneous interactions) and "date hubs" (dynamic temporal interactions) [17].

Applications: This approach has been used to identify genetic similarities among diseases and design novel therapeutic interventions [17].

Dynamic Modeling Protocol for Regulatory Networks

Purpose: To create dynamic models that simulate the temporal behavior of biological regulatory networks. Methodology:

- Model Design: Identify key molecular interactions and regulatory logic [18] [8].

- Model Construction: Translate pathway interactions into mathematical formalisms:

- Parameter Estimation: Calibrate model parameters using experimental data [8].

- Model Validation: Test model predictions against independent experimental results [8].

- Therapeutic Simulation: Simulate pharmacological interventions to identify potential targets [6].

Applications: Successfully applied to model T-cell receptor signaling, cardiac β-adrenergic signaling, and various regulatory network motifs [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies

Contemporary systems biology research requires specialized reagents and technologies that enable comprehensive data generation and analysis. The following table details key solutions essential for implementing systems approaches:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Systems Biology

| Reagent/Technology | Function | Application in Systems Biology |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Sequencing Platforms | Genome-wide characterization of DNA and RNA | Transcriptomics; epigenomics; variant identification [6] |

| Mass Spectrometry Systems | Large-scale protein and metabolite identification and quantification | Proteomics; phosphoproteomics; metabolomics [6] |

| CRISPR Screening Tools | Genome-wide functional perturbation | Gene function identification; network validation; drug target discovery [19] |

| Single-Cell Sequencing Kits | Characterization of cellular diversity at individual cell level | Cellular heterogeneity mapping; tumor microenvironment analysis [19] |

| Bioinformatics Software Suites | Data integration, network analysis, and visualization | Pathway mapping; network modeling; multi-omics integration [17] |

| AI/ML Analysis Platforms | Pattern recognition in complex datasets | Drug discovery; biomarker identification; protein folding prediction [19] [20] |

| Cell Signaling Assays | Measurement of pathway activation states | Network perturbation analysis; drug mechanism studies [6] |

| Flucloxacillin | Flucloxacillin, CAS:5250-39-5, MF:C19H17ClFN3O5S, MW:453.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Batatasin Iv | Batatasin Iv, CAS:60347-67-3, MF:C15H16O3, MW:244.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

These tools enable the generation of multidimensional datasets that capture information across multiple biological levels, facilitating the reconstruction of comprehensive network models [6]. The integration of AI-powered platforms like DeepVariant for genomic analysis and AlphaFold for protein structure prediction represents particularly advanced tools that are accelerating systems biology research [19].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The transition from traditional to systems approaches has particularly transformed pharmaceutical research, enabling more comprehensive understanding of disease mechanisms and therapeutic strategies.

Target Identification and Validation

Traditional target identification focused on differentially regulated genes, often with poor correlation to protein expression and limited efficacy [6]. Systems approaches employ network-based target identification that considers:

- Causal network models representing directed relations between biological objects [6]

- Network medicine approaches that analyze disease modules within interactomes [6]

- Multi-omics integration to identify master regulators within disease networks [6]

This approach has been successfully applied to various cancers, identifying novel therapeutic targets through analysis of dysregulated networks rather than individual genes [6].

Drug Mechanism and Polypharmacology

Systems biology enables comprehensive analysis of drug mechanisms through:

- BioMAP platforms using primary human cell-based assays and predictive analysis tools [6]

- Network pharmacology analyzing drug effects on multiple targets simultaneously [6]

- Mechanism of action studies using proteomic and transcriptomic signatures [6]

These approaches recognize that most effective drugs act on multiple targets rather than single proteins, providing a framework for understanding polypharmacology [6].

Biomarker Discovery and Personalized Medicine

Systems approaches have accelerated biomarker discovery through:

- Integrative analysis of tissue transcriptomics and urine metabolomics [6]

- Classification algorithms that group patients based on molecular signatures [6]

- Network-based stratification of complex diseases into distinct subtypes [6]

These applications facilitate the development of personalized treatment strategies tailored to individual molecular profiles [6].

Conceptual Foundations: Visualizing Pathway Relationships

The conceptual difference between traditional and systems approaches can be visualized through their representation of biological pathways:

Diagram 2: Linear vs Feedback Pathway Structures

The traditional perspective (top) views pathways as linear sequences without regulatory feedback, while systems approaches (bottom) incorporate complex feedback interactions that create emergent behaviors and nonlinear dynamics [15]. Studies comparing these structures have demonstrated that while linear pathways respond predictably to perturbations, feedback pathways exhibit complex, often counterintuitive behaviors that cannot be understood through reductionist analysis alone [15].

Future Perspectives and Emerging Trends

The evolution from mechanical to holistic thinking in biology continues to accelerate, with several emerging trends shaping future research directions:

AI and Machine Learning Integration: Advanced AI tools are being incorporated into systems biology workflows for pattern recognition, prediction, and data integration [19] [20]. These technologies enable analysis of complex datasets beyond human comprehension capacity.

Multi-Scale Modeling Approaches: Future modeling frameworks aim to connect molecular, cellular, tissue, and organism levels into unified computational representations [15].

Single-Cell Resolution: Technologies enabling analysis at individual cell resolution are revealing previously unappreciated heterogeneity in biological systems [19].

Digital Twins in Medicine: The creation of virtual patient models that simulate individual disease processes and treatment responses represents an emerging application of systems approaches [20].

Unified Quantitative Frameworks: Efforts are underway to develop shared languages and frameworks connecting statistical and mathematical modeling traditions in biology [21].

These developments promise to further transform biological research and therapeutic development, continuing the conceptual evolution from mechanical simplicity to embracing biological complexity.

The pursuit of biological knowledge has historically been guided by two contrasting epistemological approaches: traditional reductionist biology and systems biology. These frameworks differ fundamentally in how they conceptualize living organisms, formulate research questions, and validate biological knowledge. Reductionist biology, dominant throughout the 20th century, operates on the premise that complex systems are best understood by investigating their individual components in isolation [15] [17]. This approach has yielded enormous successes, including the characterization of molecular inventories and metabolic pathways. In contrast, systems biology represents a philosophical shift toward understanding biological phenomena as emergent properties of complex, dynamic networks [17] [22]. It contends that system components seldom reveal functionality when studied in isolation, and that means of reconstructing integrated systems from their parts are required to understand biological phenomena [15]. This epistemological comparison examines how these competing frameworks construct biological knowledge through different conceptual lenses, methodological tools, and validation criteria, with significant implications for research and drug development.

Philosophical Underpinnings and Conceptual Frameworks

Reductionist Biology: The Analytical Tradition

Reductionist biology stems from Cartesian analytical traditions, positing that complex biological phenomena can be completely understood by decomposing systems into their constituent parts and studying each element individually [15] [22]. This epistemology assumes that interactions between parts are weak enough to be neglected in initial analyses, and that relationships describing part behavior are sufficiently linear [22]. Knowledge construction follows a linear-causal model where understanding component A and component B independently should enable prediction of their joint behavior. The reductionist approach creates knowledge through carefully controlled experiments that isolate variables, with the epistemological ideal being that complete knowledge of molecular inventories would eventually explain the functionality of life [15]. This framework has dominated molecular and cellular biology education, emphasizing qualitative understanding of discrete biological entities and processes [23] [24].

Systems Biology: The Holistic Synthesis

Systems biology represents a philosophical return to holistic perspectives on living organisms, echoing historical views of the human body as an integrated system as seen in Greek, Roman, and East Asian medicine [15]. Its epistemology contends that "nothing in the living world happens in a vacuum" and "no life processes proceed in isolation" [15]. Knowledge construction follows a network model where understanding emerges from analyzing interactions and relationships between components. This framework explicitly recognizes that biological functionality arises from complex, dynamic systems consisting of uncounted parts and processes that are highly regulated [15]. The systems approach acknowledges that many genetic changes alter gene expression, but emphasizes that decades of research demonstrate how genetic variations bring about the molecular events that induce diseases and phenotypes through complex network interactions [17]. Rather than focusing on single molecules or signaling pathways, systems biology strategies focus on global analysis of multiple interactions at different levels, reflecting the true nature of biological processes determined by complex interactions among a cell's distinct components [17].

Table 1: Philosophical Foundations of Biological Epistemologies

| Epistemological Aspect | Reductionist Biology | Systems Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Unit of Analysis | Isolated components (genes, proteins, pathways) | Networks, interactions, and emergent properties |

| Conceptualization of Causality | Linear causality | Multidirectional, complex causality |

| Knowledge Validation Criteria | Reproducibility under controlled isolation | Predictive power for system behavior |

| View of Biological Regulation | One-to-one mapping | Distributed control through interactive networks |

| Educational Approach | Qualitative description of discrete entities [24] | Integration of quantitative skills with biological concepts [23] |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Design

Reductionist Methodologies: Isolation and Control

Reductionist biology employs methodological strategies designed to isolate variables and establish causal relationships through controlled experimentation. The epistemological strength of this approach lies in its ability to eliminate confounding factors and establish clear cause-effect relationships. Key methodological principles include:

- Single-Variable Focus: Experimental designs that manipulate one variable while holding others constant to establish causal links [24].

- Component Isolation: Studying biological entities (genes, proteins, metabolic reactions) outside their native contexts through techniques like protein purification, single-gene knockouts, and in vitro assays.

- Linear Pathway Modeling: Conceptualizing metabolic and signaling processes as sequential, linear pathways [15].

The reductionist approach has been enormously successful in characterizing biological components, with methodological frameworks deeply embedded in traditional biology education that emphasizes qualitative understanding of discrete entities [23] [24].

Systems Methodologies: Integration and Perturbation

Systems biology employs a recursive, iterative methodology that combines computational model building with experimental validation [22]. The epistemological foundation rests on understanding systems through their responses to perturbations. Key methodological principles include:

- High-Throughput Omics Technologies: Simultaneous measurement of system components (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) to capture global states [25] [17].

- Iterative Computational Modeling: The "model as hypothesis" approach where computational models are continuously refined through experimental testing [22].

- Network Analysis: Using graph theory to represent biological relationships, where nodes symbolize system constituents and links represent interactions [17].

- Multi-Scale Integration: Combining data across biological hierarchies from molecules to organisms [24].

Systems biology methodologies can be categorized into bottom-up approaches (building models from known network components and interactions) and top-down approaches (inferring networks from large datasets) [22]. Both approaches aim to understand how biological functions emerge from network properties rather than individual components.

Table 2: Methodological Comparison in Biological Research

| Methodological Aspect | Reductionist Biology | Systems Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Design | Isolated variable testing | System perturbation and response analysis |

| Data Collection | Targeted, hypothesis-driven measurements | Untargeted, high-throughput profiling [25] [17] |

| Model Building | Descriptive, graphical representations | Mathematical, computational models [15] [22] |

| Analysis Approach | Statistical comparisons between groups | Multivariate, network, and pattern analysis [17] [22] |

| Key Technologies | PCR, Western blot, enzyme assays | Microarrays, sequencing, mass spectrometry [17] |

Knowledge Representation and Modeling Frameworks

Reductionist Representations: Discrete and Qualitative

Reductionist biology represents knowledge through discrete, qualitative models that emphasize sequence, structure, and linear relationships. Knowledge is typically organized in mental categories that reflect mechanistic entities, with common student conflation between these categories representing a significant learning challenge [24]. Traditional biological models include:

- Descriptive Pathway Diagrams: Linear representations of metabolic and signaling pathways.

- Structural Models: Three-dimensional representations of biological molecules.

- Sequence Representations: Linear depictions of genetic information flow (DNA → RNA → protein).

These representations excel at communicating discrete biological mechanisms but struggle to capture dynamic, emergent system behaviors. Educational research reveals that students learning through reductionist approaches often develop fragmented knowledge structures with limited integration between related concepts [24].

Systems Representations: Networked and Quantitative

Systems biology represents knowledge through quantitative, computational models that emphasize interactions, dynamics, and emergent properties. Knowledge integration involves creating connections between ideas and building complex knowledge structures through iterative processes [24]. Representative modeling approaches include:

- Network Models: Using graph theory to represent interactions between biological components [17].

- Dynamic Simulations: Mathematical models (e.g., differential equations) that capture system behavior over time [15].

- Constraint-Based Models: Genome-scale metabolic reconstructions that simulate organismal metabolism [22].

- Multi-Scale Models: Integrative frameworks connecting molecular, cellular, and physiological levels.

These representations explicitly capture the dynamic, interconnected nature of biological systems, with educational interventions demonstrating that integrating quantitative reasoning into biological education enhances students' ability to understand complex biological systems [23].

Knowledge Construction Pathways: This diagram illustrates how reductionist and systems biology approaches follow different pathways to construct biological knowledge, with reductionism building from discrete components through linear causality to qualitative models, while systems biology builds from integrated networks through emergent properties to dynamic simulations.

Experimental Applications and Case Studies

Reductionist Experimentation: Enzyme Kinetics

The reductionist approach is exemplified by traditional enzyme kinetics studies, particularly the Michaelis-Menten theory developed in 1913 [26]. This epistemological framework constructs knowledge through controlled in vitro conditions that eliminate cellular complexity:

Experimental Protocol: Michaelis-Menten Enzyme Kinetics

- Reagent System: Purified enzyme, substrate, and buffer solution isolated from cellular context.

- Initial Rate Measurements: Reaction velocities measured under conditions where substrate concentration exceeds enzyme concentration.

- Parameter Estimation: Determination of KM and Vmax through linear transformations (Lineweaver-Burk plot) or nonlinear regression.

- Mechanistic Interpretation: Inference of catalytic mechanism from kinetic parameters.

This approach successfully characterizes molecular-level enzyme behavior but cannot predict enzyme function in native cellular environments where multiple enzymes compete for substrates and products inhibit reactions through feedback mechanisms [15].

Systems Experimentation: Network Analysis in Complex Diseases

Systems biology approaches complex diseases as emergent properties of disrupted biological networks rather than consequences of single gene defects [17]. This epistemological framework constructs knowledge through multi-omics data integration and network medicine:

Experimental Protocol: Network-Based Disease Gene Discovery

- Data Acquisition: Collection of genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic profiles from disease and control tissues.

- Network Construction: Building protein-protein interaction networks using databases like STRING or experimental data [17].

- Topological Analysis: Identification of network hubs, bottlenecks, and modules using tools like Cytoscape [17].

- Functional Validation: Experimental perturbation of candidate genes in model systems to test predictions.

This approach has successfully identified disease modules for conditions like type 2 diabetes, demonstrating that complex diseases are jointly contributed by alterations of numerous genes that coordinate as functional biological pathways or networks [25].

Table 3: Experimental Applications in Disease Research

| Research Aspect | Reductionist Approach | Systems Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Disease Conceptualization | Single gene or protein defects | Network perturbations and module dysregulation [17] |

| Therapeutic Target Identification | Single target molecules | Network neighborhoods and regulatory nodes [17] |

| Experiment Scale | Individual molecule focus | Genome-scale analyses [22] |

| Validation Strategy | Single variable manipulation | Multiple perturbation testing |

| Success Examples | Enzyme replacement therapies | Network-based drug repositioning |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Biological knowledge construction relies on specialized research tools and reagents that reflect the epistemological priorities of each approach. These essential materials enable the experimental methodologies characteristic of reductionist and systems frameworks.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Reagent/Solution | Primary Research Approach | Function in Knowledge Construction |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzymes/Proteins | Reductionist | Enables characterization of molecular function in isolation from cellular context [26] |

| Specific Inhibitors/Agonists | Reductionist | Facilitates controlled perturbation of individual system components to establish causal relationships |

| Cloning Vectors & Expression Systems | Reductionist | Allows study of gene function through controlled overexpression or knockout in model systems |

| Omics Profiling Kits | Systems | Enables comprehensive measurement of biological molecules (genes, transcripts, proteins, metabolites) [25] [17] |

| Network Analysis Software | Systems | Facilitates visualization and analysis of complex biological relationships (e.g., Cytoscape) [17] |

| Constraint-Based Modeling Tools | Systems | Supports simulation of system-level behaviors from network reconstructions [22] |

| Fujianmycin A | Fujianmycin A, CAS:96695-57-7, MF:C19H14O5, MW:322.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Kerriamycin C | Kerriamycin C, MF:C37H46O15, MW:730.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflows Comparison: This diagram contrasts the linear workflow characteristic of reductionist biology with the iterative, recursive workflow of systems biology, highlighting how each approach structures the process of knowledge construction from biological questions.

Educational Implications and Knowledge Transmission

The epistemological differences between reductionist and systems biology profoundly influence how biological knowledge is transmitted to future generations of scientists. Traditional biology education has predominantly emphasized reductionist approaches, focusing on qualitative understanding of discrete biological components [23] [24]. This educational model often fails to equip students with the quantitative skills necessary for modern biological research, perpetuating the perception that biology is relatively math-free [23].

Systems biology education represents a paradigm shift, integrating quantitative skills with biological concepts throughout the curriculum [23] [27]. This approach recognizes that understanding complex biological systems requires students to develop integrated knowledge networks that are both productively organized and flexibly dynamic [24]. Educational research demonstrates that students must sort mechanistic entities into appropriate mental categories and that conflation between these categories is common without explicit instructional support [24].

The challenges of systems biology education include balancing depth and breadth across disciplines, integrating experimental and computational approaches, and developing adaptive curricula that keep pace with rapidly evolving methodologies [27]. Successful educational models incorporate active learning approaches, project-based coursework, and iterative model-building exercises that reflect the recursive nature of systems science [27].

Reductionist and systems biology represent complementary rather than contradictory approaches to constructing biological knowledge. Each epistemology offers distinct strengths: reductionism provides detailed mechanistic understanding of individual components, while systems biology reveals emergent properties and network behaviors. The future of biological research lies in leveraging both approaches through iterative cycles of deconstruction and reconstruction [15] [22].

This epistemological synthesis is particularly crucial for addressing complex challenges in drug development and therapeutic innovation, where both detailed molecular mechanisms and system-level responses determine clinical outcomes. As systems biology continues to evolve and integrate with artificial intelligence approaches [28], its epistemological framework will further transform how we conceptualize, investigate, and understand the profound complexity of living systems.

For decades, drug discovery has predominantly followed a "single target, single disease" model, aiming to develop highly selective drugs that interact with one specific protein or pathway [29]. This approach has demonstrated success in treating monogenic diseases and conditions with well-defined molecular mechanisms. However, clinical data increasingly reveal that single-target drugs often prove insufficient for interfering with complete disease networks in complex disorders, frequently leading to limited therapeutic efficacy, development of drug resistance, and adverse side effects [29]. The recognition of these limitations has catalyzed a fundamental shift in pharmaceutical research toward multi-target strategies and systems biology approaches that acknowledge and address the complex, interconnected nature of pathological processes [30].

Complex diseases such as cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, epilepsy, and diabetes involve highly intricate etiologies with multifaceted pathophysiological mechanisms [29]. These diseases typically arise from dysregulations across multiple molecular networks rather than isolated defects at single points [30]. The inherent biological complexity of these conditions presents fundamental challenges to single-target interventions, necessitating innovative approaches that consider the system-wide behavior of disease networks. This case study examines the scientific evidence demonstrating the limitations of single-target drugs in complex disease treatment and explores the emerging paradigm of network-based therapeutic strategies.

The Inadequacy of Single-Target Approaches in Complex Diseases

Scientific Evidence from Clinical and Preclinical Studies

Substantial evidence from both clinical practice and preclinical research demonstrates the limitations of single-target therapies in complex disease management. In oncology, for instance, targeted therapies designed to inhibit specific cancer-driving proteins initially show promising results, but their efficacy is often limited by the development of resistance mechanisms. Cancer cells frequently activate alternative pathways or undergo mutations that bypass the inhibited target, leading to treatment failure [31]. This phenomenon of resistance development is particularly problematic in single-target approaches, as the biological system finds new ways to maintain the disease state despite precise intervention at one node [29].

In neurological disorders, similar limitations are evident. Epilepsy represents a compelling case where single-target antiseizure medications (ASMs) frequently prove inadequate for treatment-resistant forms of the condition [32]. Preclinical data from animal models demonstrates that single-target ASMs show significantly reduced efficacy in challenging seizure models such as the 6-Hz corneal kindling test at higher current strengths, whereas multi-target ASMs consistently exhibit broader therapeutic profiles across multiple models [32]. The table below summarizes comparative efficacy data of single-target versus multi-target ASMs across standardized preclinical seizure models:

Table 1: Comparative Efficacy of Single-Target vs. Multi-Target Antiseizure Medications in Preclinical Models [32]

| Compound | Primary Targets | ED50 (mg/kg) in MES test | ED50 (mg/kg) in s.c. PTZ test | ED50 (mg/kg) in 6-Hz (44 mA) test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Target ASMs | ||||

| Phenytoin | Voltage-activated Na+ channels | 9.5 | NE | NE |

| Carbamazepine | Voltage-activated Na+ channels | 8.8 | NE | NE |

| Lacosamide | Voltage-activated Na+ channels | 4.5 | NE | 13.5 |

| Ethosuximide | T-type Ca2+ channels | NE | 130 | NE |

| Multi-Target ASMs | ||||

| Valproate | GABA synthesis, NMDA receptors, Na+ & Ca2+ channels | 271 | 149 | 310 |

| Topiramate | GABAA & NMDA receptors, Na+ channels | 33 | NE | 126 |

| Cenobamate | GABAA receptors, persistent Na+ currents | 9.8 | 28.5 | 16.4 |

| Padsevonil | SV2A,B,C and GABAA receptors | 92.8 | 4.8 | 2.43 |

ED50 = Median Effective Dose; MES = Maximal Electroshock Seizure; PTZ = Pentylenetetrazole; NE = Not Effective

The data clearly demonstrates that single-target ASMs exhibit narrow spectrums of activity, typically showing efficacy in only one or two seizure models, whereas multi-target ASMs display broader efficacy across multiple models. This pattern correlates with clinical observations where approximately one-third of epilepsy patients prove resistant to treatment, primarily those with complex forms of the disorder [32].

Network-Level Limitations of Single-Target Interventions

The fundamental limitation of single-target drugs lies in their inability to effectively modulate disease networks that operate through distributed, interconnected pathways. Complex diseases typically involve:

- Compensatory mechanisms: Biological systems often activate alternative pathways when primary pathways are inhibited, maintaining the disease state through redundant signaling networks [29].

- Multifactorial pathogenesis: Diseases like Alzheimer's and atherosclerosis involve multiple pathological processes simultaneously, including protein misfolding, inflammation, oxidative stress, and cellular dysfunction [30].

- Dynamic progression: Disease mechanisms evolve over time, with different pathways gaining prominence at various disease stages, making static single-target interventions increasingly inadequate as the condition progresses [29].

The COVID-19 pandemic provided a striking example of network-level disease complexity, with the SARS-CoV-2 virus affecting not only the respiratory system but also the gastrointestinal tract, nervous system, and cardiovascular system [29]. This multisystem involvement creates therapeutic challenges that single-target approaches cannot adequately address, as they lack the comprehensive modulatory capacity needed to simultaneously impact multiple symptomatic manifestations.

Experimental Evidence: Methodologies and Findings

In Vitro and In Vivo Models for Evaluating Drug Efficacy

Research comparing single-target and multi-target approaches employs standardized experimental methodologies across both in vitro and in vivo systems. High-throughput screening (HTS) and high-content screening (HCS) technologies enable systematic evaluation of compound effects on molecular targets and cellular phenotypes [29]. These approaches facilitate the identification of multi-target compounds through activity profiling across multiple target classes.

In cancer research, sophisticated in vitro models demonstrate the superior efficacy of multi-target approaches in complex diseases. A 2020 study developed a innovative Ru–Pt conjugate that combined cisplatin-based chemotherapy with photodynamic therapy in a single molecular entity [33]. This multi-action drug was tested across various cancer cell lines, including drug-resistant strains, using the following experimental protocol:

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Target Drug Evaluation

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Ru-Pt Conjugate | Combined chemo- and photodynamic therapy | Multi-action cancer therapeutic [33] |

| HTS Biochemical Screening Systems | Detect drug-target binding using fluorescence/absorbance | Natural product screening [29] |

| HTS Cell Screening Systems | Detect drug-induced cell phenotypes without known targets | Multi-target drug screening [29] |

| 6-Hz Seizure Model (44 mA) | Corneal kindling model of treatment-resistant seizures | Preclinical ASM efficacy testing [32] |

| Intrahippocampal Kainate Model | Chronic model of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy | Preclinical ASM evaluation in chronic epilepsy [32] |

| Amygdala Kindling Model | Electrical kindling model for focal seizures | Preclinical evaluation of ASMs [32] |

The experimental results demonstrated that the Ru-Pt conjugate exhibited significantly higher cytotoxicity against cancer cells compared to individual components alone, with irradiated samples showing dramatically enhanced tumor-killing rates [33]. Most notably, the multi-action conjugate demonstrated tenfold higher efficacy against drug-resistant cell lines compared to single-agent treatments, highlighting the potential of multi-target approaches to overcome resistance mechanisms that limit conventional therapies [33].

Network Pharmacology and Systems Biology Methodologies

Systems biology approaches employ distinct methodological frameworks that differ fundamentally from traditional reductionist methods. Network pharmacology represents a key methodology that maps drug-disease interactions onto biological networks to identify optimal intervention points [13]. The typical workflow involves:

- Multi-omics data integration: Combining genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to construct comprehensive network models of disease mechanisms [13].

- Network analysis: Using computational tools to identify key network nodes and connections that drive disease phenotypes.

- Target identification: Selecting optimal target combinations that maximize therapeutic efficacy while minimizing network destabilization.

- Validation: Experimental verification of network predictions using in vitro and in vivo models.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches further enhance these methodologies by enabling pattern recognition in high-dimensional data sets, predicting biomarkers and treatment responses, and identifying novel biological pathways [13]. These computational methods facilitate the transition from single-target to multi-target therapeutic strategies by providing insights into complex network behaviors that cannot be discerned through conventional linear approaches.

Diagram 1: Single-Target vs. Systems Biology Drug Discovery Approaches

Multi-Target Therapeutic Strategies: Evidence and Applications

Designed Multiple Ligands (DMLs) and Combination Therapies

The limitations of single-target drugs have spurred the development of several multi-target therapeutic strategies, including rationally designed multi-target drugs (also termed Designed Multiple Ligands or DMLs) and fixed-dose combination therapies [32]. DMLs represent single chemical entities specifically designed to modulate multiple targets simultaneously, offering potential advantages in pharmacokinetic predictability and patient compliance compared to drug combinations [32].

Between 2015-2017, approximately 21% of FDA-approved new chemical entities were DMLs, compared to 34% single-target drugs, indicating growing pharmaceutical interest in this approach [32]. In epilepsy treatment, padsevonil represents one of the first intentionally designed DMLs, developed to simultaneously target SV2A/B/C synaptic vesicle proteins and GABAA receptors [32]. Although this particular compound did not separate from placebo in phase IIb trials for treatment-resistant focal epilepsy, its development established important principles for multi-target drug design in complex neurological disorders.

Fixed-dose combinations represent another prominent multi-target strategy, particularly valuable for diseases with multiple interrelated pathological processes. In cardiovascular disease and diabetes, fixed-dose combinations simultaneously target multiple risk factors—such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia—in a single formulation [34]. This approach demonstrates the practical application of network medicine principles by addressing the interconnected nature of cardiovascular metabolic risk factors without requiring patients to manage multiple separate medications.

Natural Products as Multi-Target Therapeutics

Natural products represent an important source of multi-target therapeutics, with more than half of approved small molecule drugs being derived from or related to natural products [29]. Compounds such as morphine, paclitaxel, and resveratrol inherently modulate multiple biological targets, embodying the multi-target principle that underlies their therapeutic effects [29].

The multi-target properties of natural products present both opportunities and challenges for drug development. While their inherent polypharmacology offers advantages for complex disease treatment, the development process faces obstacles including difficulty in active compound screening, target identification, and preclinical dosage optimization [29]. Advanced technologies such as network pharmacology, integrative omics, CRISPR gene editing, and computational target prediction are helping to address these challenges by clarifying the mechanisms of action and optimal application of natural product-based therapies [29].

Systems Biology: A New Framework for Drug Discovery

Conceptual Foundations and Methodologies

Systems biology represents a fundamental paradigm shift from reductionist to holistic approaches in biomedical research. Where traditional drug discovery focuses on isolating and targeting individual components, systems biology investigates biological systems as integrated networks, examining emergent properties that arise from system interactions rather than individual elements [13]. This perspective is particularly valuable for understanding and treating complex diseases that involve disturbances across multiple interconnected pathways.

Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) has emerged as a key discipline within systems biology, constructing comprehensive mathematical models that simulate drug effects across multiple biological scales—from molecular interactions to organism-level responses [35]. These models integrate diverse data types including pharmacokinetic parameters, target binding affinities, signaling pathway dynamics, and physiological responses to predict how drugs will behave in complex biological systems [35]. The predictive capability of QSP models is increasingly recognized in drug development, with some models achieving regulatory acceptance for specific applications such as predicting therapy-induced cardiotoxicities [13].

Applications in Complex Disease Research

Systems approaches are demonstrating particular utility in neurodegenerative disease research, where traditional single-target strategies have consistently failed to yield effective treatments. Diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's involve multiple interconnected pathological processes including protein misfolding, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and metabolic dysfunction [30]. Network medicine approaches are helping to redefine these conditions based on molecular endotypes—underlying causative mechanisms—rather than descriptive symptomatic phenotypes [30].

This reconceptualization enables identification of shared therapeutic targets across etiologically distinct disorders. For example, since protein aggregation represents a common hallmark of multiple neurodegenerative diseases, therapeutics designed to eliminate protein aggregates could potentially benefit multiple conditions [30]. Similarly, network-based analyses have identified olanzapine—a multitargeted drug with nanomolar affinities for over a dozen different receptors—as an effective treatment for resistant schizophrenia where highly selective antipsychotic drugs failed [30].

Diagram 2: Network-Based Multi-Target Intervention in Complex Disease

The accumulating evidence from both clinical experience and preclinical research demonstrates that single-target drug paradigms face fundamental limitations in complex disease treatment. These limitations arise from the network properties of biological systems, where diseases emerge from disturbances across multiple interconnected pathways rather than isolated defects at single points. The development of resistance, inadequate efficacy, and inability to address disease complexity represent significant challenges that single-target approaches cannot adequately overcome.

Systems biology and network pharmacology provide innovative frameworks for addressing these challenges through multi-target therapeutic strategies. Designed multiple ligands, fixed-dose combinations, and natural product-based therapies offer promising approaches for modulating disease networks more comprehensively. The integration of computational modeling, multi-omics data, and AI-driven analysis enables more rational design of therapeutic interventions that acknowledge and leverage the inherent complexity of biological systems.

As drug discovery continues to evolve beyond the "one disease, one target, one drug" paradigm, the successful development of future therapies for complex diseases will increasingly depend on adopting network-based perspectives that align with the fundamental principles of biological organization. This paradigm shift holds particular promise for addressing conditions like neurodegenerative diseases, treatment-resistant epilepsy, and complex cancers, where single-target approaches have historically demonstrated limited success.

Omics Integration and Computational Modeling: Practical Implementation in Drug Development