From Networks to Cures: Validating Disease Modules Through Experimental Perturbation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating disease modules—localized neighborhoods within molecular interaction networks perturbed in disease—through experimental perturbation.

From Networks to Cures: Validating Disease Modules Through Experimental Perturbation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating disease modules—localized neighborhoods within molecular interaction networks perturbed in disease—through experimental perturbation. We first explore the foundational concept of disease modules and the critical need for their experimental validation. The article then delves into cutting-edge computational methods for module detection, from statistical physics to deep learning, and their application in designing perturbation studies. A dedicated section addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, including data sparsity and network incompleteness. Finally, we present a rigorous framework for the validation and comparative analysis of disease modules using gold standards like genetic association data and risk factors, synthesizing key takeaways and future directions for translating network medicine into clinical impact.

The What and Why: Defining Disease Modules and the Imperative for Perturbation

In network medicine, a disease module is defined as a localized set of highly interconnected genes or proteins within the human interactome that collectively contribute to a pathological phenotype [1]. The core hypothesis is that disease-associated genes are not scattered randomly but cluster in specific network neighborhoods, reflecting their shared involvement in disrupted biological processes [1] [2]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of contemporary computational methods for identifying these modules, framed within the critical thesis that computational predictions must be rigorously validated through experimental perturbation research. The transition from static network maps to dynamic, context-aware models—a shift underscored by principles like the Constrained Disorder Principle—demands that module definitions be stress-tested against empirical, causal evidence [3].

Comparative Analysis of Disease Module Identification Methods

The performance of module identification methods can be objectively benchmarked by evaluating the genetic relevance of their predicted modules, typically measured by enrichment for genes implicated in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [1] [2].

Table 1: Benchmark Performance of Module Identification Methods (Based on Transcriptomic Data)

| Method Category | Representative Method | Key Principle | Avg. GWAS Enrichment Performance | Notable Disease Strengths | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clique-Based | Clique Sum | Identifies interconnected cliques (complete subgraphs) from seed genes. | Highest (Significant in 34% of modules across 7 diseases) [1] | Immune-associated diseases (MS, RA, IBD) [1] | May overlook diffuse, non-clique topology. |

| Seed-Based Diffusion | DIAMOnD | Expands from known disease genes via network connectivity. | Moderate | Coronary artery disease, Type 2 Diabetes [1] | Performance depends on quality/quantity of seed genes. |

| Co-expression Network | WGCNA | Clusters genes based on correlated expression patterns. | Moderate | Type 2 Diabetes [1] | Sensitive to dataset and parameter selection. |

| Community Detection | Louvain, MHKSC | Optimizes modularity to partition network into communities. | Variable | General-purpose; used in DREAM challenges [2] | Modules may lack direct disease relevance without integration of prior knowledge. |

| Consensus Approach | Multi-method Consensus | Aggregates results from multiple independent methods. | High (25.5% of modules significant) [1] | Improves robustness across diverse diseases. | Increased computational complexity. |

Table 2: Evaluation Metrics for Module Quality

| Metric | Formula/Principle | Interpretation in Validation Context |

|---|---|---|

| GWAS Enrichment (Pascal) | Pathway scoring algorithm using GWAS summary statistics [1]. | Quantifies genetic evidence supporting the module's relevance to disease etiology. |

| F-Score | Harmonic mean of modularity, conductance, and connectivity [2]. | Unsupervised measure of topological soundness (dense intra-connections, sparse inter-connections). |

| Risk Factor Association | Enrichment for genes altered by environmental/lifestyle risk factors (e.g., methylation changes) [1]. | Links genetic module to epidemiological and epigenetic disease drivers, suggesting points for experimental perturbation. |

Experimental Protocols for Module Validation via Perturbation

Validating a computationally defined disease module requires moving from association to causation. The following protocol, derived from a multi-omic study on Multiple Sclerosis (MS), provides a framework [1].

Protocol: Multi-Omic Module Discovery and Experimental Validation

- Module Identification: Integrate transcriptomic and methylomic data from patient cohorts. Apply the top-performing clique-based method (e.g., Clique Sum) to a high-confidence interactome (e.g., STRING DB) to identify a candidate disease module [1].

- Genetic & Epigenetic Enrichment Analysis:

- Genetic: Test the module for significant enrichment of GWAS hit genes using tools like Pascal [1].

- Epigenetic: Overlap module genes with independent datasets of genes differentially methylated or expressed in response to known disease risk factors (e.g., vitamin D, smoking in MS). Statistical significance (e.g., P = 10⁻⁴⁷) confirms environmental relevance [1].

- In Silico Perturbation Modeling: Simulate network perturbations (node/gene knockout, edge inhibition) on the module. Use centrality measures to predict key driver genes whose disruption should most significantly disassemble the module or alter its output.

- In Vitro/In Vivo Experimental Perturbation:

- Perturbation Tools: Apply CRISPR-Cas9 knockouts, siRNA knockdowns, or pharmacological inhibitors to predicted key driver genes in relevant cell models (e.g., immune cells for MS).

- Readouts: Measure downstream molecular changes (RNA-seq, phospho-proteomics) within the module and assess functional disease phenotypes (e.g., cytokine release, demyelination).

- Validation Criterion: Successful experimental perturbation of key drivers should recapitulate the disease-associated molecular signature and disrupt the module's predicted functional output.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Resources for Disease Module Research

| Item | Function & Application | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| High-Confidence Interactome | Provides the scaffold (network) for module detection. | STRING database (experimentally validated interactions) [1]. |

| Module Identification Software | Implements algorithms for mining the interactome. | MODifieR R package (integrates 8 methods) [1]. |

| GWAS Enrichment Tool | Quantifies genetic evidence for module relevance. | Pascal algorithm [1]. |

| Perturbation Reagents | Enables causal testing of key driver genes. | CRISPR-Cas9 libraries, siRNA pools, specific kinase inhibitors. |

| Multi-Omic Data Repositories | Source for transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic patient data. | GEO, ArrayExpress, TCGA. |

| Validation Cohort Datasets | Independent datasets for replicating module-risk factor associations. | DNA methylation studies on risk-factor exposed cohorts [1]. |

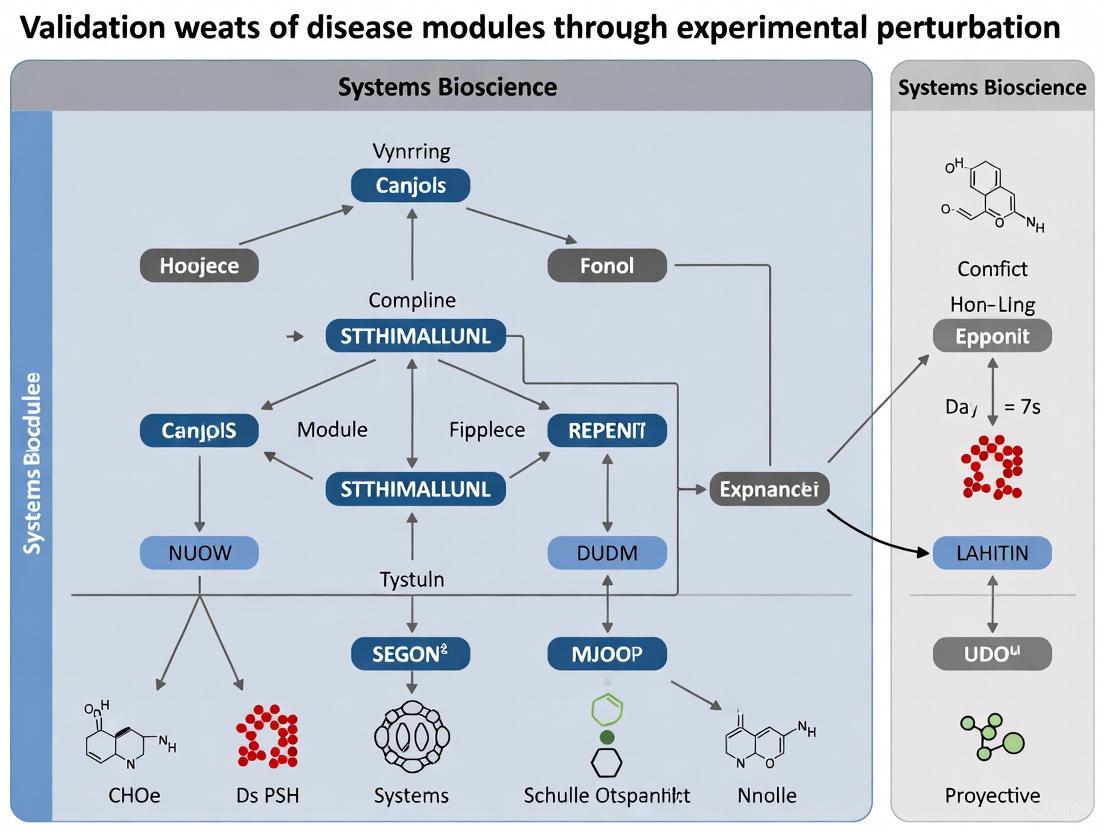

Visualizing the Workflow: From Data to Validated Module

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental validation pipeline.

Pathway Logic of a Validated Multi-Omic Module The diagram below conceptualizes the mechanistic logic derived from a validated disease module, as seen in the MS multi-omic study, where genetic risk and environmental factors converge on a coherent biological process [1].

The transition from investigating a local, singular hypothesis to understanding systems-level dysfunction represents a paradigm shift in biological research. This approach moves beyond the one-gene, one-disease model to recognize that complex phenotypes emerge from perturbed interactions within intricate molecular networks. Validating disease modules through experimental perturbation requires sophisticated analytical frameworks capable of modeling these complex relationships. Structural equation modeling (SEM) has emerged as a powerful statistical methodology that enhances pathway analysis by testing hypothesized causal structures and modeling direct and indirect regulatory influences within biological systems [4]. Unlike traditional correlation-based methods, SEM evaluates mechanistic explanations for observed gene expression changes, allowing researchers to test complex theories by examining relationships between multiple variables simultaneously [4].

Analytical Frameworks for Systems-Level Validation

The Structural Equation Modeling Approach

Structural equation modeling combines factor analysis, multiple regression, and path analysis to build and evaluate models that demonstrate how various biological variables are connected and influence one another [4]. In the context of pathway perturbation analysis, SEM uses directed edges (→) to represent regulatory relationships (e.g., transcription factor binding) and bidirected edges () to account for unmeasured confounders (e.g., environmental factors or latent proteins) that jointly affect multiple genes [4]. This framework is particularly well-suited for analyzing gene expression data and uncovering the underlying mechanisms of biological pathways because it focuses on relationships between observed variables while accounting for unobserved factors [4].

The mathematical foundation of SEM enables researchers to move from simple correlation to causal inference within biological networks. By testing predefined network structures against empirical data, SEM can evaluate how well a hypothesized pathway explains observed gene expression patterns, revealing path coefficients that reflect regulatory influences [4]. This approach is especially valuable for identifying context-specific rewiring of regulatory relationships in disease conditions through multiple group analysis, which tests invariance in path coefficients and network structures across experimental groups [4].

Comparative Analysis of Pathway Perturbation Tools

Table 1: Comparison of Pathway Analysis and Network Modeling Tools

| Tool Name | Primary Methodology | Data Input Types | Key Features | Visualization Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ShinyDegSEM | Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) | Gene expression data, pathway topologies | DEG detection, pathway impact analysis, SEM-based model refinement | Interactive graphs, tables, pathway diagrams |

| SEMgraph | Causal network analysis via SEM | Gene expression, protein-protein interactions | Confirmatory and exploratory modeling, group difference testing | Network graphs, path diagrams |

| GenomicSEM | SEM for genomic data | Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) | Multivariate analysis of genetic data | Structural equation diagrams |

| QTLnet | QTL-driven phenotype network | Quantitative trait loci, phenotype data | Causal network inference, genetic architecture modeling | Graphical network models |

Experimental Protocols for SEM-Based Pathway Validation

The standard workflow for validating disease modules through SEM-based perturbation analysis involves multiple defined stages:

Differentially Expressed Gene (DEG) Detection: Initial processing of gene expression data (e.g., from microarrays or RNA-seq) using established methods like Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM) to identify genes with statistically significant expression changes between experimental conditions [4].

Pathway Model Generation: Construction of initial pathway models based on established biological knowledge from databases such as the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) or protein-protein interaction networks from the STRING database [4].

SEM Model Specification: Definition of the structural equation model incorporating:

- Measurement models linking observed variables to latent constructs

- Structural models specifying hypothesized directional relationships between variables

- Covariance structures accounting for unmeasured confounding factors

Model Estimation and Evaluation: Application of estimation techniques (e.g., maximum likelihood) to calculate path coefficients, followed by assessment of model fit using statistical tests and indices including chi-square tests, CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR [4].

Comparative Group Analysis: Testing for invariance in path coefficients and network structures between experimental and control groups to identify significantly altered regulatory relationships in disease conditions [4].

Biological Interpretation: Contextualizing statistical findings within established biological knowledge to generate testable hypotheses about disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets.

Visualizing Pathway Relationships and Experimental Workflows

Signaling Pathway Impact Analysis Workflow

Regulatory Network Dynamics in Disease

Quantitative Data Comparison in Pathway Perturbation Studies

Table 2: Experimental Results from SEM-Based Pathway Analysis in Neurodegenerative Disease Studies

| Study Focus | Analytical Method | Key Perturbed Pathway | Identified Hub Genes | Model Fit Indices (CFI/RMSEA) | Significant Path Coefficient Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration (FTLD-U) | SEM pathway analysis | Glutamatergic synapse pathway | PSD-95 | CFI > 0.92, RMSEA < 0.06 | Strengthened PSD-95→SHANK2 in mutation conditions |

| Multiple Sclerosis (MS) | SEM with Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis | Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis | ARF6, CRKL, PIP5K1C | CFI > 0.90, RMSEA < 0.07 | Altered regulatory relationships in phagocytosis pathway |

| Schizophrenia (SCZ) Gene Networks | Comparative SEM | Neuronal signaling pathways | Multiple gene interactions | p < 0.01 significance level | Identified altered relationships between gene interactions |

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pathway Perturbation Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Primary Function | Application in Perturbation Studies | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Datasets | Input data for DEG analysis | Provide quantitative transcriptome measurements for pathway modeling | Microarray, RNA-seq data |

| KEGG Pathway Database | Source of curated pathway topologies | Provides biologically plausible initial models for SEM analysis | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| STRING Database | Protein-protein interaction networks | Enhances model robustness by incorporating known interactions | Search Tool for Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins |

| SEM Software Packages | Statistical modeling and analysis | Enable testing of complex pathway hypotheses and causal structures | R packages: SEMgraph, GenomicSEM, GW-SEM |

| Primary Cell Cultures | Experimental validation systems | Provide biological context for testing predicted pathway perturbations | Disease-relevant cell types |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Targeted gene perturbation | Enable experimental validation of predicted key regulators in pathways | Gene editing platforms |

Discussion: Integration of Multi-Modal Data for Robust Validation

The SEM pipeline exemplifies the power of integrating multi-modal data sources, such as gene expression (microarrays), curated pathway topologies (KEGG), and protein-protein interaction networks (STRING database), to construct biologically plausible regulatory models [4]. This integration enhances robustness by cross-validating hypotheses against orthogonal data types. For example, in the study of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitinated inclusions (FTLD-U), SEM analysis of the glutamatergic synapse pathway identified PSD-95 as a hub gene and revealed altered regulatory relationships involving SHANK2 and glutamate receptors under progranulin mutation [4]. The model further suggested context-specific activation or inhibition of connections, such as strengthened PSD-95→SHANK2 interactions in mutant conditions [4].

Similarly, in multiple sclerosis (MS), SEM highlighted dysregulated genes (ARF6, CRKL, and PIP5K1C) within the Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis pathway [4]. These findings align with prior studies implicating phagocytic dysfunction in MS pathogenesis, demonstrating how SEM can disentangle direct regulatory effects from indirect associations to offer mechanistic insights into disease processes [4]. By combining pathway and interaction data, SEM provides a framework for validating and iteratively refining biological network models, thereby bridging gaps between static pathway maps and dynamic biological reality [4].

The validation of disease modules through experimental perturbation research represents a critical frontier in biomedical science. By leveraging computational frameworks like structural equation modeling alongside experimental validation, researchers can transition from local hypotheses to a comprehensive understanding of systems-level dysfunction. This integrated approach enables the identification of key regulatory hubs and pathway perturbations that drive disease phenotypes, ultimately informing targeted therapeutic development. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they promise to uncover the complex mechanistic underpinnings of human disease, bridging the gap between molecular observations and systems-level pathophysiology.

In the field of biomedical research, the ability to predict how cells respond to perturbation is a significant unsolved challenge. While computational models, particularly single-cell foundation models (scFMs), represent an important step toward creating "virtual cells," their predictions remain unvalidated without experimental grounding. This guide compares the performance of open-loop computational predictions against a closed-loop framework that integrates experimental perturbation data, demonstrating why experimental validation is the indispensable gold standard for elucidating disease modules and discovering therapeutic targets.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Open-Loop Versus Closed-Loop In Silico Perturbation

The core methodology for benchmarking prediction frameworks involves fine-tuning a foundation model, performing in silico perturbations, and validating predictions against experimental data.

- Base Model Fine-Tuning: A pre-trained single-cell foundation model (Geneformer) is fine-tuned on single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNAseq) data from relevant biological systems (e.g., T-cells or engineered hematopoietic stem cells) to classify cellular states (e.g., activated vs. resting T-cells, or RUNX1-knockout vs. control HSCs) [5].

- Open-Loop ISP: The fine-tuned model performs in silico perturbation (ISP) across thousands of genes, simulating both overexpression and knockout to predict their effect on cellular state. Predictions are validated against orthogonal datasets, such as flow cytometry data from CRISPR screens [5].

- Closed-Loop ISP: The model is further fine-tuned by incorporating scRNAseq data from experimental perturbation screens (e.g., Perturb-seq) alongside the original phenotypic data. The model then performs ISP again, excluding the genes used in the fine-tuning perturbations [5].

Disease Module Detection via Multi-Omics Integration

An alternative computational approach for identifying disease-associated genes involves integrating multiple omics data types with the human molecular interactome.

- Methodology: The Random-Field O(n) Model (RFOnM) is a statistical physics approach that integrates data from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and gene-expression profiles, or mRNA data and DNA methylation, with the human interactome to detect disease modules—subnetworks whose perturbation is linked to a disease phenotype [6].

- Validation: The performance of the detected disease modules is evaluated based on the connectivity of the module and the network proximity of its genes to known disease-associated genes from the Open Targets Platform [6].

Performance Data Comparison

The quantitative performance of open-loop prediction, closed-loop refinement, and multi-omics integration demonstrates the critical value of experimental data.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Predictive Frameworks in T-Cell Activation

| Metric | Open-Loop ISP | Closed-Loop ISP | Differential Expression (DE) | DE & ISP Overlap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | 3% | 9% | 3% | 7% |

| Negative Predictive Value (NPV) | 98% | 99% | 78% | Information Missing |

| Sensitivity | 48% | 76% | 40% | Information Missing |

| Specificity | 60% | 81% | 50% | Information Missing |

| AUROC | 0.63 | 0.86 | Information Missing | Information Missing |

Source: Adapted from systematic evaluation of Geneformer-30M-12L performance [5].

Table 2: Disease Module Detection Performance (LCC Z-score)

| Disease | RFOnM (Multi-Omics) | DIAMOnD (GWAS) | DIAMOnD (Gene Expression) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease | ~3.5 | ~7.5 | ~2.5 |

| Asthma | ~9.5 | ~6.5 | ~7.5 |

| COPD (Large) | ~10.5 | ~4.5 | ~3.5 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | ~9.0 | ~7.0 | ~4.0 |

| Breast Invasive Carcinoma (BRCA) | ~10.0 | Information Missing | Information Missing |

Source: Adapted from application of the RFOnM approach across multiple diseases [6]. LCC: Largest Connected Component. A higher Z-score indicates a more significant, less random module.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the core workflows and biological pathways discussed.

Closed-Loop ISP Workflow

RUNX1-FPD Rescue Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Experimental Perturbation Studies

| Research Reagent | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Primary Human T-Cells | Model system for studying T-cell activation and validating ISP predictions of genetic perturbations on immune cell function [5]. |

| Engineered Human HSCs | Disease modeling for rare hematologic disorders like RUNX1-FPD; provides a biologically relevant system for target discovery when patient samples are scarce [5]. |

| CRISPRa/CRISPRi Libraries | Enable genome-wide activation or interference screens to experimentally test the functional impact of gene overexpression or knockout on cellular phenotypes [5]. |

| Perturb-seq | A single-cell RNA sequencing method that combines genetic perturbations with scRNAseq, providing the high-quality experimental data essential for closing the loop in scFM fine-tuning [5]. |

| CD3-CD28 Beads / PMA/Ionomycin | Standard reagents used for T-cell stimulation and activation, creating the phenotypic states (resting vs. activated) for model fine-tuning [5]. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | Pharmacological tools for experimentally validating predicted therapeutic targets (e.g., inhibitors for PRKCB, mTOR) in disease models [5]. |

The data presented offers a clear verdict: while computational models provide a powerful starting point for hypothesis generation, their predictions require experimental validation to achieve scientific rigor. The transition from open-loop to closed-loop frameworks, which incorporate real perturbation data, results in a dramatic three-fold increase in predictive value and accuracy. For researchers pursuing disease mechanisms and therapeutic targets, this integrated approach is not merely an option but the gold standard for validation.

The validation of disease modules—network-based representations of disease mechanisms—is paramount in modern biology. Experimental perturbation research serves as the critical bridge between computational predictions and biological understanding, enabling researchers to dissect complex diseases and identify novel therapeutic strategies. By systematically perturbing biological systems and observing the outcomes, scientists can ground truth network models in empirical data, directly informing the drug discovery pipeline. This guide compares the performance of three leading perturbation-based technologies: single-cell CRISPR screening, knowledge graph reasoning, and bioengineered human disease models.

Comparative Analysis of Perturbation-Based Technologies

The following table summarizes the core characteristics and performance metrics of three key technological approaches.

| Technology | Key Measurable Output | Experimental Validation/Performance | Key Advantage | Primary Application in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell CRISPR Screening (e.g., Perturb-seq) [7] [8] | - Single-cell RNA-seq profiles- Gene-specific RNA synthesis/degradation rates- Functional clustering of genes | - High guide RNA capture rate (~97-99.7% of cells) [8]- Median knockdown efficiency of 67.7% for target genes [8]- Decouples transcriptional branches (e.g., UPR) with single-cell resolution [7] | Unbiased, genome-wide functional mapping with high-content phenotypic readouts. | Target identification and validation; understanding mechanism of action. |

| AI-Driven Knowledge Graphs (e.g., AnyBURL) [9] | - Ranked list of predicted drug candidates- Set of logical rules and evidence chains providing therapeutic rationale | - Strong correlation with preclinical experimental data for Fragile X syndrome [9]- Reduced generated paths by 85% for Cystic Fibrosis and 95% for Parkinson's disease, enhancing relevance [9] | Generates human-interpretable explanations for drug-disease relationships, enabling rapid hypothesis generation. | Drug repositioning for rare and complex diseases. |

| Bioengineered Human Disease Models [10] | - Drug efficacy readouts (e.g., cell viability, functional assays)- Toxicity and safety profiles | - Addresses the ~95% drug attrition rate in clinical trials [10]- Higher clinical biomimicry than animal models; emulates human-specific pathogen responses (e.g., SARS-CoV-2) [10] | Bridges the translational gap by providing human-relevant data preclinically. | Preclinical efficacy and safety testing; patient-stratified medicine. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for implementation, this section outlines the core methodologies for each featured technology.

This protocol enables the high-throughput profiling of transcriptome kinetics across hundreds of genetic perturbations.

- 1. Perturbation Library Design: Clone a library of single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting genes of interest into a specialized lentiviral vector (e.g., CROP-seq or Perturb-seq vector). The vector contains a guide barcode (GBC) for tracking and an sgRNA expression cassette.

- 2. Cell Line Engineering: Generate a stable cell line (e.g., HEK293) with inducible expression of a potent CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) effector, such as dCas9-KRAB-MeCP2.

- 3. Viral Transduction & Selection: Transduce the cell population with the sgRNA library at a low Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) to ensure most cells receive a single sgRNA. Select transduced cells with puromycin for 5-7 days.

- 4. Gene Knockdown & Metabolic Labeling: Induce dCas9 expression with doxycycline for ~7 days to allow for robust gene knockdown. Prior to harvesting, pulse-label newly synthesized RNA with 200 µM 4-thiouridine (4sU) for 2 hours.

- 5. Single-Cell Library Preparation & Sequencing: Use a combinatorial indexing strategy (e.g., PerturbSci-Kinetics) to capture whole transcriptomes, nascent transcriptomes (via 4sU chemical conversion), and sgRNA identities from hundreds of thousands of single cells in a pooled format. Prepare libraries for high-throughput sequencing.

- 6. Data Analysis: Map sequencing reads to assign cell barcodes, unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), and sgRNA identities. Infer RNA synthesis and degradation rates for each genetic perturbation using ordinary differential equation models. Perform functional clustering based on transcriptomic signatures.

This protocol describes how to generate and filter evidence for drug repositioning candidates using a symbolic reasoning model.

- 1. Knowledge Graph Construction: Build a comprehensive biological knowledge graph integrating nodes (e.g., drugs, diseases, genes, pathways, phenotypes) and edges (e.g., "binds," "treats," "activates") from public (e.g., MONDO, Orphanet) and proprietary databases.

- 2. Disease Landscape Analysis: Curate a list of genes and pathways of high importance to the specific disease of interest (e.g., Fragile X syndrome). This list serves as a biological filter.

- 3. Rule Learning & Drug Prediction: Apply a reinforcement learning-based symbolic model (e.g., AnyBURL) to the knowledge graph. The model learns logical rules (e.g.,

compound_treats_disease(X,Y) ⇐ compound_binds_gene(X,A), gene_activated_by_compound(B,A), compound_in_trial_for(B,Y)) and uses them to predict novel drug-disease relationships. - 4. Evidence Chain Generation & Auto-Filtering: For each predicted drug, generate all possible evidence chains (paths in the KG that explain the prediction). Apply a multi-stage auto-filtering pipeline:

- Rule Filter: Retain rules with high confidence scores.

- Significant Path Filter: Remove redundant or trivial paths.

- Gene/Pathway Filter: Prioritize evidence chains that contain nodes from the pre-defined disease landscape.

- 5. Experimental Validation: Test the top-ranked, rationally selected drug candidates in preclinical models relevant to the disease (e.g., patient-derived cells or animal models) to validate efficacy.

This protocol outlines the use of advanced human cell-based models for testing drug efficacy and safety.

- 1. Model Selection: Choose an appropriate human disease model based on the research question:

- Organoids: Self-organizing 3D structures derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) or adult stem cells (ASCs) for modeling organ-level function and disease.

- Organs-on-Chips (OoCs): Microfluidic devices containing bioengineered human tissues that emulate organ-level physiology and allow for the study of inter-tissue crosstalk.

- 2. Model Maturation: Culture the selected model under conditions that promote maturation and a disease-relevant phenotype. This may involve air-liquid interface cultivation for epithelial tissues or specific cytokine cocktails to induce disease states.

- 3. Compound Screening: Treat the models with drug candidates at physiologically relevant concentrations. Include positive and negative controls.

- 4. Phenotypic Readout: Assess drug effects using high-content assays. Measure endpoints such as:

- Cell viability and apoptosis.

- Tissue-specific functional markers (e.g., albumin secretion for liver models, beat frequency for cardiac models).

- Transcriptomic and proteomic profiling via RNA sequencing or multiplexed immunofluorescence.

- Barrier integrity (for gut, lung, or blood-brain barrier models).

- 5. Data Integration & Translation: Compare the results from the human disease models with known clinical data to validate predictive value. Use the data to make go/no-go decisions for advancing candidates into clinical trials.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The following diagrams, created with Graphviz, illustrate the core workflows and a key biological pathway dissected by these technologies.

Experimental Validation Framework

UPR Pathway Dissected by Perturb-seq

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of the described experiments relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions for perturbation research.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| dCas9-KRAB-MeCP2 Effector [8] | A potent CRISPRi fusion protein that mediates transcriptional repression by recruiting repressive chromatin modifiers to the sgRNA-targeted genomic locus. |

| Perturb-seq / CROP-seq Vector [7] [8] | A lentiviral vector engineered to co-express a single guide RNA (sgRNA) and a guide barcode (GBC), enabling pooled screening and deconvolution of single-cell data. |

| 4-Thiouridine (4sU) [8] | A nucleoside analog for metabolic RNA labeling. Incorporated into newly synthesized RNA, allowing it to be biochemically separated from pre-existing RNA for nascent transcriptome analysis. |

| Droplet-Based Single-Cell RNA-Seq Platform [7] | A technology (e.g., from 10x Genomics) that partitions individual cells into oil droplets for parallel barcoding and sequencing of thousands of single-cell transcriptomes. |

| Healx Knowledge Graph [9] | A customized biomedical knowledge graph integrating diverse data sources (e.g., drugs, diseases, genes, pathways) to support computational drug repositioning and rationale generation. |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) [10] | Patient-derived cells that can be differentiated into any cell type, serving as the foundation for generating personalized organoids and other bioengineered disease models. |

| Extracellular Matrix Hydrogel (e.g., Matrigel) [10] | A scaffold derived from basement membrane proteins that provides the 3D structural support necessary for organoid formation and self-organization. |

| Microfluidic Organ-on-a-Chip Device [10] | A perfused chip containing micro-channels and chambers lined with living human cells that emulate the structure and function of human organs and tissue-tissue interfaces. |

The How: Computational Detection and Perturbation-Responsive Profiling

In the field of network medicine, a central paradigm posits that cellular functions disrupted in complex diseases correspond to localized neighborhoods within the vast human protein-protein interaction (PPI) network, known as disease modules [11] [12]. These modules represent groups of cellular components that collectively contribute to a biological function, and their perturbation can lead to disease phenotypes [11]. The accurate identification of disease modules is therefore a critical prerequisite for elucidating disease mechanisms, predicting disease genes, and informing drug development [11] [12].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of two distinct methodological approaches for disease module detection: the established, seed-based DIAMOnD algorithm and the novel, Random-Field Ising Model (RFIM) approach, which leverages principles from statistical physics. The evaluation is framed within the essential context of experimental validation, examining how these computational predictions are ultimately tested and refined through biological perturbation research.

Methodological Foundations: A Tale of Two Algorithms

The core difference between the DIAMOnD and RFIM methods lies in their fundamental strategy for identifying the disease module: DIAMOnD performs a local, sequential expansion from known seeds, whereas RFIM performs a global optimization of the entire network's state.

DIAMOnD: Seed-Based Connectivity Significance

The DIseAse MOdule Detection (DIAMOnD) algorithm operates on the principle of connectivity significance [13]. Unlike methods that prioritize highly connected hub proteins, DIAMOnD systematically identifies proteins that have a statistically significant number of interactions with known disease-associated "seed" proteins, correcting for the proteins' overall connectivity (degree) [13] [14].

Experimental Protocol for DIAMOnD:

- Input: A list of known seed genes/proteins for a disease and a background PPI network.

- Iterative Ranking: For every non-seed protein in the network, the algorithm calculates a p-value (using the hypergeometric test) that quantifies the significance of its connectivity to the current set of seed proteins.

- Module Expansion: The protein with the smallest p-value is added to the disease module.

- Repetition: Steps 2 and 3 are repeated, sequentially adding new proteins to the module in each round. A stopping criterion (e.g., after adding a pre-defined number of genes, or based on validation results) is applied to define the final module [13] [14].

Figure 1: DIAMOnD Algorithm Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the iterative, seed-expansion process of the DIAMOnD algorithm.

RFIM: A Whole-Network Statistical Physics Approach

The Random-Field Ising Model (RFIM) approach reframes the problem of disease module detection as one of finding the ground state of a disordered magnetic system, a classic model in statistical physics [11]. This method aims to optimize a "score" across the entire network simultaneously, rather than growing a module from a local starting point.

Experimental Protocol for RFIM:

- Network Representation: The PPI network is represented as a graph G = (V, E), where nodes (genes/proteins) are assigned a binary state σi = +1 ("active"/in module) or -1 ("inactive"/not in module).

- Parameter Assignment: Node weights {hi} are assigned based on intrinsic evidence for disease association (e.g., from GWAS). Edge weights {Jij} are assigned to favor correlation between connected nodes' states.

- Energy Minimization: The optimal state of all nodes {σi} is determined by finding the configuration that minimizes the cost function (Hamiltonian):

H({σi}) = -∑Jijσiσj - ∑(H + hi)σi[11] - Module Extraction: The disease module is defined as the set of all nodes with σi = +1 in the ground state configuration. This module may comprise multiple connected components [11].

Figure 2: RFIM Algorithm Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the whole-network optimization process of the RFIM approach.

Comparative Performance Analysis

A study applying both RFIM and DIAMOnD, along with other methods, to genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of ten complex diseases (e.g., asthma, various cancers, cardiovascular disease) provides quantitative data for a direct comparison [11].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of RFIM and DIAMOnD Performance

| Performance Metric | RFIM Approach | DIAMOnD Algorithm | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Efficiency | Polynomial time complexity; solved exactly by max-flow algorithm [11] | Iterative process; computational load depends on network size and seed set [11] | Analysis of GWAS data for 10 complex diseases [11] |

| Module Connectivity | Finds optimally connected set of nodes from a whole-network perspective [11] | Builds a single connected component through sequential addition [13] | Measured connectivity of the resulting disease modules [11] |

| Robustness | High robustness to incompleteness of the interactome [11] | Robustness demonstrated in noisy networks, though reliant on seed connectivity [13] | Performance evaluated on networks with varying degrees of artificial noise [11] [13] |

| Methodological Basis | Statistical Physics; global optimization of a cost function [11] | Network Topology; significance of connectivity to seed proteins [13] | Underlying theoretical foundation |

Validation Through Experimental Perturbation

Computational predictions of disease modules are hypotheses that require rigorous validation through experimental perturbation. This process involves manipulating candidate genes within the predicted module in disease-relevant models and observing phenotypic outcomes.

The Validation Workflow: From In Silico to In Vitro

A generalized pathway for validating computationally derived disease modules involves a multi-stage process that bridges bioinformatics and wet-lab biology.

Figure 3: Disease Module Validation Workflow. This diagram outlines the iterative cycle of computational prediction and experimental validation.

Case Study: Validating the Asthma Disease Module

A seminal study on asthma provides a concrete example of this validation pipeline using the DIAMOnD algorithm [14].

- Module Identification: Starting with 144 known asthma seed genes, DIAMOnD was used to identify a putative asthma disease module of 441 genes [14].

- Bioinformatic Validation: The module was enriched with genes from independent asthma GWAS datasets and genes differentially expressed in asthmatic cells, supporting its biological relevance [14].

- Candidate Identification: Analysis of the module's wiring diagram suggested a close link between the GAB1 signaling pathway and glucocorticoids (GCs), a common asthma treatment [14].

- Experimental Perturbation:

- GC Treatment: BEAS-2B bronchial epithelial cells were treated with GCs, resulting in an observed increase in GAB1 protein levels, confirming a functional link [14].

- siRNA Knockdown: Knockdown of GAB1 in the same cell line led to a decrease in the level of the pro-inflammatory factor NFκB, suggesting a novel regulatory pathway in asthma [14].

- Conclusion: This experimental perturbation validated GAB1's role within the predicted asthma module and uncovered a new potential mechanism for therapeutic intervention [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The experimental validation of disease modules relies on a suite of biological reagents and tools. The table below lists key materials used in the featured asthma study and the broader field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Experimental Validation

| Research Reagent / Model | Function in Validation | Example from Case Study |

|---|---|---|

| siRNA / shRNA | Targeted knockdown of gene expression to assess the functional impact of a candidate gene within a module. | siRNA against GAB1 to probe its role in regulating NFκB [14]. |

| Cell Lines | In vitro models for perturbation experiments; should be disease-relevant. | BEAS-2B human bronchial epithelial cells [14]. |

| Small Molecule Agonists/Antagonists | To perturb signaling pathways identified within the disease module. | Glucocorticoid treatment to stimulate the pathway linked to GAB1 [14]. |

| Antibodies | For protein detection and quantification via Western Blot or ELISA in phenotypic assays. | Used to measure protein levels of GAB1 and NFκB after perturbation [14]. |

| Human Organoids / Bioengineered Tissue | More physiologically relevant 3D human models for probing disease mechanisms and drug responses. | Emerging as valuable tools for increasing the biomimicry of validation studies [10]. |

| Omics Datasets (GWAS, Expression) | For bioinformatic validation of the computational module prior to experimentation. | Used to enrich the asthma module and establish its initial credibility [14]. |

The comparison reveals that the choice between DIAMOnD and RFIM is not merely algorithmic but strategic. DIAMOnD excels in contexts where a reliable set of seed genes is available and a rationale for connectivity significance is preferred. Its iterative nature provides a clear, interpretable expansion path from known biology into the unknown. In contrast, the RFIM approach offers a mathematically rigorous framework that is less dependent on initial seeds and considers the network's state holistically, potentially capturing more diffuse disease signals that are topologically disconnected but functionally coherent [11].

Both methods, however, are computational tools whose true value is unlocked only through experimental validation. The cycle of prediction, perturbation, and refinement, as exemplified in the asthma case study, is what ultimately transforms a computationally derived network neighborhood into a biologically validated disease module with direct implications for understanding mechanism and discovering new therapeutic targets [14]. As network models and experimental perturbation techniques—such as more complex organoids and OoCs [10]—continue to advance, so too will our ability to pinpoint and validate the core functional modules driving human disease.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our ability to dissect cellular heterogeneity in disease, moving beyond bulk tissue analysis to reveal cell-type-specific disease modules and regulatory networks. The integration of experimental perturbations with scRNA-seq readouts provides a powerful framework for validating these disease modules by establishing causal relationships between genetic variants, environmental stressors, and pathological cellular states. This approach enables researchers to move from correlative observations to mechanistic understanding of disease processes, which is particularly valuable for identifying novel therapeutic targets and developing personalized treatment strategies. As noted in a 2025 review, scRNA-seq "enables a deeper understanding of the complexity of human diseases" and plays a crucial role in "biomarker discovery and drug development" [15].

Profiling perturbation responses with scRNA-seq involves systematically introducing genetic, chemical, or environmental interventions and measuring their transcriptomic consequences at single-cell resolution. This methodology has been applied across diverse disease contexts, including Alzheimer's disease [16], type 2 diabetes [17], and various cancers [18], revealing how disease-associated genes function within specific cell types and states. The resulting insights are advancing the validation of disease modules—coherent sets of molecular components and their interactions that drive pathological processes—thereby bridging the gap between genetic associations and functional mechanisms.

Experimental Design for Perturbation-scRNA-seq Studies

Core Methodological Approaches

Several experimental frameworks have been developed for coupling perturbations with scRNA-seq profiling, each with distinct strengths and applications:

Perturb-seq/CROP-seq: These technologies combine CRISPR-based genetic perturbations (knockout, interference, or activation) with scRNA-seq readouts, enabling high-throughput functional screening at single-cell resolution. These approaches typically use guide RNA (gRNA) barcoding to link perturbations to transcriptional profiles within pooled screens [19] [20].

Multiplexed scRNA-seq profiling (e.g., sci-Plex): This method uses chemical perturbations with cellular hashing to profile thousands of chemical conditions in a single experiment, typically employing combinatorial barcoding to distinguish different treatment conditions [19].

Network analysis of native perturbations: Instead of introducing experimental perturbations, this approach analyzes native disease states as "perturbations" to identify dysregulated networks, as demonstrated in type 2 diabetes research using differential gene coordination network analysis (dGCNA) [17].

Platform Selection and Technical Considerations

Selecting appropriate scRNA-seq platforms is critical for perturbation studies, as different methods vary significantly in sensitivity, cell throughput, and detection efficiency. A comprehensive 2021 benchmarking study compared seven high-throughput scRNA-seq methods for immune cell profiling and found that "10x Genomics 5′ v1 and 3′ v3 methods demonstrated the highest mRNA detection sensitivity" with "fewer dropout events, which facilitates the identification of differentially-expressed genes" [21]. This is particularly important for perturbation studies where detecting subtle transcriptomic changes is essential.

Key technical considerations include:

- Cell capture efficiency: Ranging from ~30-80% for 10x Genomics platforms to <2% for ddSEQ and Drop-seq methods [21]

- Multiplet rates: Typically targeted around 5% with optimized cell loading concentrations [21]

- Library efficiency: The fraction of reads assignable to individual cells varies from >90% for ICELL8 to ~50-75% for 10x platforms [21]

- mRNA detection sensitivity: Critical for identifying differential expression following perturbations, with 10x 3′ v3 detecting ~4,776 genes per cell compared to ~3,255-3,644 genes for ddSEQ and Drop-seq [21]

For studies requiring full-length transcript information or working with large cells (>30μm diameter), plate-based methods (e.g., Smart-seq2) provide advantages despite lower throughput [17] [15].

Computational Methods for Analyzing Perturbation Responses

Method Categories and Representative Algorithms

Table 1: Computational Methods for Single-Cell Perturbation Response Prediction

| Method Category | Representative Algorithms | Key Features | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple linear baselines | Ridge regression, Principal component regression | Additive extrapolation from control and perturbation means | Computational efficiency, Transparency | Limited capacity for complex interactions |

| Autoencoder-based models | scGen, CPA, scVI | Encode cells and interventions in latent space; counterfactuals via vector arithmetic | Handles technical noise, Captures non-linear relationships | May suffer from mode collapse [20] |

| Prior knowledge graph learning | GEARS | Learns gene embeddings on co-expression graphs and perturbation embeddings on gene ontology graphs | Incorporates biological priors | Depends on quality of prior knowledge |

| Transformer-based foundation models | scGPT, scFoundation | Pre-trained on millions of cells; adapted via conditioning tokens | Captures complex gene-gene relationships | Computationally intensive, May underperform simple baselines [22] |

| Representation alignment methods | scREPA | Aligns VAE latent embeddings with scFM representations using cycle-consistent alignment | Robust to noisy data, Strong cross-study generalization | Complex training process [23] |

| Perturbation scoring methods | Perturbation-response score (PS) | Quantifies perturbation strength via constrained quadratic optimization | Handles partial perturbations, Enables dosage analysis | Requires predefined signature genes [19] |

Performance Benchmarking Insights

Recent benchmarking studies have revealed surprising insights about perturbation prediction methods. A 2025 benchmark of foundation models (scGPT and scFoundation) found that "even the simplest baseline model—taking the mean of training examples—outperformed scGPT and scFoundation" in predicting post-perturbation gene expression profiles [22]. Furthermore, "basic machine learning models that incorporate biologically meaningful features outperformed scGPT by a large margin," with random forest regressors using Gene Ontology features achieving superior performance on multiple Perturb-seq datasets [22].

These findings highlight the critical importance of proper benchmarking methodologies. Subsequent research has identified that "systematic control bias" and "signal dilution" in standard evaluation metrics can artificially inflate the performance of naive baselines like the mean predictor [20]. New metrics such as Weighted MSE (WMSE) and weighted delta R² have been proposed to better capture model performance on biologically relevant signals [20].

The perturbation-response score (PS) method has demonstrated particular strength in quantifying heterogeneous perturbation outcomes, outperforming alternatives like mixscape in analyzing partial gene perturbations in CRISPRi-based Perturb-seq datasets [19]. PS enables single-cell dosage analysis without needing to titrate perturbations and identifies 'buffered' and 'sensitive' response patterns of essential genes [19].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for perturbation-scRNA-seq studies, covering key stages from experimental design to biological insights.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Perturbation-scRNA-seq Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Key Applications | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Droplet-based single-cell capture | High-throughput perturbation screens | High cell recovery (30-80%), Moderate sequencing efficiency (50-75% cell-associated reads) [21] |

| CRISPR guides (sgRNAs) | Genetic perturbation induction | Gene knockout (CRISPRko), interference (CRISPRi), activation (CRISPRa) | Variable efficiency requiring careful optimization [19] |

| Smart-seq2 | Plate-based full-length scRNA-seq | Deep molecular profiling of specific cell types | Higher sensitivity per cell but lower throughput [17] |

| Cell hashing antibodies | Sample multiplexing | Pooling samples to reduce batch effects | Enables sci-Plex chemical screening approaches [19] |

| Viability dyes | Cell quality assessment | Exclusion of dead cells during sample preparation | Critical for data quality, especially in primary tissues [15] |

| UMI barcodes | Unique molecular identifiers | Accurate transcript quantification | Essential for distinguishing biological variation from technical noise [21] |

Case Studies in Disease Module Validation

Alzheimer's Disease and PANoptosis

A 2025 study leveraged scRNA-seq analysis to identify PANoptosis-related biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease (AD), revealing a coordinated cell death pathway integrating pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis [16]. Researchers analyzed scRNA-seq data (GSE181279) from AD patients and normal controls, identifying differentially expressed genes that were integrated with PANoptosis-associated genes from published literature. Through machine learning approaches (LASSO, SVM, and random forest), they identified five biomarkers (BACH2, CKAP4, DDIT4, GGNBP2, and ZFP36L2) with diagnostic potential [16]. This study demonstrates how perturbation of native disease states can reveal novel disease modules, with the nominated biomarkers showing significant associations with immune cell infiltration and connecting amyloid-β and tau pathology to inflammatory cell death pathways.

Type 2 Diabetes and Islet Cell Networks

Research on type 2 diabetes (T2D) exemplifies the power of network-based analysis of perturbation responses. Using differential gene coordination network analysis (dGCNA) on Smart-seq2 data from 16 T2D and 16 non-T2D individuals, researchers identified eleven networks of differentially coordinated genes (NDCGs) in pancreatic beta cells [17]. These included both hyper-coordinated ("Ribosome," "Insulin secretion," "Lysosome") and de-coordinated ("UPR," "Microfilaments," "Glycolysis," "Mitochondria") modules in T2D [17]. Remarkably, the "Insulin secretion" module showed significant enrichment for T2D risk genes from GWAS (p-adj = 4.5e-6), with five of 32 module genes overlapping with 14 high-confidence fine-mapped genes (Odds ratio 129; p-adj = 6.08e-8) [17]. This approach validated both established and novel disease modules in T2D pathogenesis, demonstrating how native disease states serve as natural perturbations that reveal dysfunctional regulatory networks.

Cancer Biomarker Discovery

In papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), integrative analysis of bulk and single-cell transcriptomics identified three potential biomarkers (ENTPD1, SERPINA1, and TACSTD2) through differential expression analysis, weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA), and machine learning [18]. scRNA-seq analysis revealed tissue stem cells, epithelial cells, and smooth muscle cells as key cellular players in PTC, with cell-cell communication analysis highlighting COL4A1-CD4 and COL4A2-CD4 as important ligand-receptor pairs [18]. Pseudotime analysis demonstrated stage-specific expression of the identified biomarkers during cell differentiation, providing insights into PTC development and progression [18].

Diagram 2: Computational framework for perturbation-response score (PS) calculation, illustrating the process from perturbation input to biological applications.

Implementation Guidelines and Best Practices

Experimental Design Considerations

Successful perturbation-scRNA-seq studies require careful experimental planning:

Perturbation efficiency validation: Include controls to assess perturbation efficiency, particularly for CRISPR-based approaches where incomplete editing can confound results [19]. For chemical perturbations, consider dose-response relationships and temporal dynamics.

Cell number requirements: Ensure sufficient cell numbers for robust statistical power, particularly for rare cell types. The benchmark study by Li et al. (2020) highlighted that "existing methods are very diverse in performance" and "even the top-performance algorithms do not perform well on all datasets, especially those with complex structures" [24].

Replication strategy: Include biological replicates to account for donor-to-donor variability, using sample multiplexing where possible to minimize batch effects [15].

Control selection: Appropriate control conditions are critical for interpreting perturbation effects. Include both untreated controls and where possible, control perturbations (e.g., non-targeting guides in CRISPR screens).

Computational Analysis Recommendations

Metric selection: Move beyond traditional metrics like MSE and Pearson correlation, which can be misleading due to control bias and signal dilution [20]. Implement DEG-aware metrics such as Weighted MSE (WMSE) and weighted delta R² for more biologically meaningful evaluation [20].

Method benchmarking: Always include simple baselines (mean predictor, linear models) in benchmarking studies, as these can outperform complex models on standard metrics [22] [20].

Visualization approaches: Combine dimensional reduction visualization (UMAP, t-SNE) with perturbation-specific metrics (PS scores) to capture response heterogeneity [19].

Data integration: For studies combining native disease states with experimental perturbations, methods like dGCNA can reveal how disease backgrounds alter cellular responses to perturbations [17].

The integration of scRNA-seq with perturbation technologies has created powerful frameworks for validating disease modules and understanding pathological mechanisms at unprecedented resolution. While computational methods continue to evolve, current benchmarks suggest that incorporating biological prior knowledge often outperforms overly complex models without clear inductive biases. The field is moving toward more rigorous evaluation standards that better capture biologically relevant signals and avoid metric artifacts that have plagued earlier comparisons.

Future developments will likely focus on multi-omic perturbation readouts, spatial context integration, and improved foundation models that better leverage existing biological knowledge. As noted in a recent review, "The integration of AI and machine learning algorithms into big data analysis offers hope for overcoming these hurdles, potentially allowing scRNA-seq and multi-omics approaches to bridge the gap in our understanding of complex biological systems and advances the development of precision medicine" [15]. For researchers investigating specific disease modules, perturbation-scRNA-seq approaches offer a direct path from genetic association to functional validation, accelerating the identification and prioritization of therapeutic targets.

Understanding complex biological systems requires moving beyond simple correlation to establishing causality, especially when validating disease modules through experimental perturbation research. In this context, interpretable deep learning frameworks have emerged as powerful tools for prioritizing differential spatial patterns in biological data. These frameworks enable researchers to move from black-box predictions to biologically meaningful insights by identifying which spatial features and patterns most significantly contribute to observed phenotypes or treatment responses.

The validation of disease modules—functionally coherent molecular networks implicated in disease mechanisms—relies heavily on sophisticated computational approaches that can handle high-dimensional spatial data from technologies like spatially resolved transcriptomics (SRT). These technologies profile gene expression while preserving spatial localization within tissues, creating opportunities to understand spatial organization in disease contexts such as cancer, intraepithelial neoplasia, and immune infiltration [25]. However, the complexity of these datasets demands specialized frameworks that not only predict spatial patterns but also explain which features drive these predictions and how they contribute to disease-relevant spatial organizations.

Comparative Analysis of Interpretable Deep Learning Frameworks

Performance Metrics Across Experimental Domains

Table 1: Comparative performance of interpretable spatial analysis frameworks

| Framework | Primary Application | Key Strengths | Limitations | Experimental Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STModule [25] | Tissue module identification from SRT data | Bayesian approach; detects multi-scale modules; handles various resolutions | Requires computational expertise for implementation | Identifies novel spatial components; captures broader biological signals than alternatives |

| CINEMA-OT [26] | Causal inference of single-cell perturbations | Separates confounding from treatment effects; enables individual treatment effect analysis | Challenging with high differential abundance | Outperforms other methods in treatment-effect estimation; enables response clustering |

| ANN+SHAP Framework [27] | Water quality prediction (conceptual parallel) | Integrates topographic, meteorological, socioeconomic data; strong predictive performance | Domain-specific implementation | R² values 0.47-0.77 for various parameters; 37.8-246.7% accuracy improvement with additional factors |

| MELD Algorithm [28] | Quantifying perturbation effects at single-cell level | Continuous measure across transcriptomic space; graph-based approach | Limited to single-cell data types | 57% more accurate than next-best method at identifying enriched/depleted clusters |

Capabilities for Disease Module Validation

Table 2: Framework capabilities specific to disease module validation

| Framework | Spatial Resolution Handling | Causal Inference | Multi-scale Analysis | Experimental Perturbation Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STModule | 55µm - sub-1µm (ST, Visium, Slide-seq, Stereo-seq) | Limited | Excellent (automatically determines module granularities) | Indirect (post-perturbation analysis) |

| CINEMA-OT | Single-cell resolution | Strong (potential outcomes framework) | Moderate (cell-level focus) | Direct (designed for perturbation analysis) |

| MELD | Single-cell resolution | Moderate (relative likelihood estimates) | Limited | Direct (quantifies perturbation effects) |

| ANN+SHAP | Watershed/sub-basin level | Correlation-based | Limited | Not designed for biological perturbations |

Detailed Framework Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

STModule for Tissue Module Identification

STModule employs a Bayesian framework to identify tissue modules—spatially organized functional units within transcriptomic landscapes. The methodology involves spatial Bayesian factorization that simultaneously groups co-expressed genes and estimates their spatial patterns [25].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Input: Process SRT data representing gene expression levels at spatial locations (spots/cells) as matrix ( Y \in \mathbb{R}^{S \times L} ) where ( S ) is genes and ( L ) is locations.

- Model Formulation: Factorize expression profile into ( C ) tissue modules by estimating:

- Spatial maps ( P \in \mathbb{R}^{S \times C} ) representing spatial activity of each module

- Associated genes ( G \in \mathbb{R}^{C \times L} ) representing gene loadings in each module

- Spatial Covariance Modeling: Apply squared exponential kernel to account for spatial continuity: ( \Sigma{s,s'}^c = \exp\left(-\frac{d{s,s'}^2}{2lc^2}\right) ) where ( d{s,s'} ) is Euclidean distance between spots and ( l_c ) is module-specific length scale.

- Gene Association: Use spike and slab prior to induce sparse structure for ( G ) matrix, grouping genes with similar spatial patterns.

- Implementation: Apply to diverse SRT technologies including 10× Visium, Slide-seqV2, and Stereo-seq data.

CINEMA-OT for Causal Perturbation Analysis

CINEMA-OT (Causal Independent Effect Module Attribution + Optimal Transport) applies a strict causal framework to single-cell perturbation experiments, separating confounding variation from genuine treatment effects [26].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Preprocessing: Prepare single-cell data from multiple conditions (control vs. treatment).

- Confounder Identification: Apply independent component analysis (ICA) to separate confounding factors from treatment-associated factors using Chatterjee's coefficient-based test.

- Causal Matching: Implement weighted optimal transport to generate counterfactual cell pairs:

- Compute optimal transport matching using entropic regularization

- Apply Sinkhorn-Knopp algorithm for efficient solution

- Treatment Effect Estimation: Calculate Individual Treatment Effect (ITE) matrices representing causal effects for each cell.

- Downstream Analysis:

- Cluster ITE matrices to identify groups with shared treatment response

- Perform gene set enrichment analysis on response groups

- Compute synergy metrics for combinatorial treatments

MELD for Perturbation Quantification

The MELD algorithm quantifies the effects of experimental perturbations at single-cell resolution using graph signal processing to estimate relative likelihoods of observing cells in different conditions [28].

Experimental Protocol:

- Manifold Construction: Build affinity graph connecting cells from all samples based on transcriptional similarity.

- Sample Indicator Signals: Create one-hot indicator signals for each experimental condition, normalized to account for different sequencing depths.

- Kernel Density Estimation: Apply heat kernel as low-pass filter over graph to estimate sample density: ( \hat{f}(x,t) = e^{-tL}x = \Psi h(\Lambda) \Psi^{-1}x ) where ( L ) is graph Laplacian, ( t ) is bandwidth.

- Relative Likelihood Calculation: Row-wise normalize sample-associated density estimates to obtain relative likelihoods.

- Vertex Frequency Clustering: Identify populations of cells similarly affected by perturbations using frequency composition of relative likelihood scores.

Visualization of Computational Workflows

STModule Bayesian Factorization Workflow

STModule Workflow: Bayesian factorization of spatial transcriptomics data into tissue modules.

CINEMA-OT Causal Inference Pipeline

CINEMA-OT Pipeline: Causal inference through confounder identification and optimal transport.

Integrated Framework for Spatial Pattern Prioritization

Integrated Framework: Comprehensive workflow from spatial data to validated disease modules.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational tools for spatial perturbation studies

| Category | Specific Solution | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| SRT Platforms | 10× Genomics Visium | Enables transcriptome-wide profiling with 55µm resolution | Spatial mapping of gene expression in tissue contexts [25] |

| SRT Platforms | Slide-seqV2 / Stereo-seq | Provides enhanced resolution (10µm - sub-1µm) for cellular-level analysis | High-resolution spatial mapping approaching single-cell resolution [25] |

| Computational Tools | STModule Software | Bayesian method for identifying tissue modules from SRT data | Dissecting spatial organization in cancer, immune infiltration [25] |

| Computational Tools | CINEMA-OT Package | Causal inference for single-cell perturbation experiments | Analyzing combinatorial treatments, synergy effects [26] |

| Computational Tools | MELD Python Package | Quantifying perturbation effects using graph signal processing | Identifying cell populations specifically affected by perturbations [28] |

| Interpretability Methods | SHAP Analysis | Explains model predictions by quantifying feature importance | Identifying dominant factors influencing outcomes in complex models [27] [29] |

| Data Resources | Tarjama-25 Benchmark | Evaluation benchmark for specialized translation models | Performance validation in domain-specific applications [30] |

| Experimental Models | Airway Organoids | Human-relevant system for perturbation studies | Studying viral infection and environmental exposure effects [26] |

The integration of interpretable deep learning frameworks with spatial omics technologies represents a transformative approach for validating disease modules through experimental perturbation research. Frameworks like STModule, CINEMA-OT, and MELD provide complementary strengths—from identifying spatially organized functional units in tissues to establishing causal relationships in perturbation responses. The critical advantage of these approaches lies in their ability to not only predict spatial patterns but also explain the biological features driving these patterns, enabling researchers to move from correlation to causation in understanding disease mechanisms.

As spatial technologies continue to advance in resolution and throughput, the role of interpretable deep learning frameworks will become increasingly essential for prioritizing the most biologically relevant spatial patterns from complex multidimensional datasets. This capabilities particularly crucial in therapeutic development, where understanding the spatial context of drug responses can significantly accelerate target validation and mechanism-of-action studies. The frameworks discussed here provide a foundation for this spatial revolution in biomedical research, offering rigorous computational approaches for extracting meaningful biological insights from increasingly complex spatial data.

The validation of disease modules—subnetworks of molecular interactions implicated in pathological states—relies heavily on understanding how these networks respond to perturbations. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technologies, such as Perturb-seq, have emerged as powerful tools for systematically mapping these responses, enabling high-resolution characterization of transcriptional changes across thousands of genetic and drug perturbations [31]. However, a fundamental challenge persists: the destructive nature of RNA sequencing means the same cell cannot be observed both before and after perturbation, creating inherent data sparsity and unpaired data structures that complicate dynamic modeling [32].

Generative artificial intelligence models are now overcoming these limitations by predicting cellular responses to unseen perturbations and reconstructing continuous trajectory information absent from experimental data. The Direction-Constrained Diffusion Schrödinger Bridge (DC-DSB) represents a significant advancement in this domain, providing a framework for learning probabilistic trajectories between unperturbed and perturbed cellular states [31] [33]. This review quantitatively compares DC-DSB against contemporary alternatives, detailing experimental protocols and performance metrics to guide researchers in validating disease modules through computational perturbation research.

Comparative Analysis of Perturbation Prediction Models

Key Methodological Approaches

Multiple computational approaches have been developed to predict single-cell perturbation responses, each with distinct architectural advantages and limitations:

DC-DSB (Direction-Constrained Diffusion Schrödinger Bridge): Learns probabilistic trajectories between unperturbed and post-perturbation distributions by minimizing path-space Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence. It incorporates hierarchical representations from experimental variables and biological prior knowledge, with a direction-constrained conditioning strategy that injects condition signals along biologically relevant perturbation trajectories [31] [33].

Departures: Employs distributional transport with Neural Schrödinger Bridges to directly align control and perturbed cell populations. It uses minibatch optimal transport (OT) for source-target pairing and jointly trains separate bridges for discrete gene activation states and continuous expression dynamics [32].

River: An interpretable deep learning framework prioritizing perturbation-responsive gene patterns in spatially resolved transcriptomics data. It uses a two-branch predictive architecture with position and gene expression encoders to identify genes with differential spatial expression patterns (DSEPs) across conditions [34].

CPA (Compositional Perturbation Autoencoder): A variational autoencoder-based approach that incorporates perturbation type and dosage information to model static state mappings between conditions, focusing on capturing dose-response relationships [31].

CellOT: An optimal transport-based method that constructs mappings from unperturbed to perturbed states but faces limitations in modeling continuous expression dynamics [31].

Table 1: Methodological Comparison of Single-Cell Perturbation Prediction Models

| Model | Core Architecture | Training Objective | Temporal Modeling | Biological Priors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC-DSB | Direction-constrained diffusion Schrödinger bridge | Path-space KL divergence minimization | Continuous trajectories | Gene ontology, experimental variables |

| Departures | Neural Schrödinger bridge with minibatch OT | Distributional alignment between conditions | Joint discrete-continuous dynamics | Gene regulatory networks |

| River | Two-branch encoder with attribution | Differential spatial pattern prediction | Spatial context changes | Spatial coordinates, tissue architecture |

| CPA | Conditional variational autoencoder | Reconstruction with perturbation conditioning | Static state mappings | Perturbation type, dosage information |

| CellOT | Optimal transport | Cost minimization between distributions | Discrete state transitions | None explicitly mentioned |

Performance Comparison Across Benchmarks

Experimental validation of perturbation prediction models employs diverse datasets including genetic perturbations (CRISPR-based) and drug perturbations across various cell types. Standard benchmarks evaluate prediction accuracy, generalization to unseen perturbations, and capability to capture heterogeneous cellular responses.

Table 2: Performance Comparison on Key Benchmark Datasets

| Model | K562 Dataset (Accuracy) | RPE1 Dataset (Accuracy) | Adamson Dataset (Accuracy) | Unseen Combination Generalization | Training Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC-DSB | Improved over baselines | Improved over baselines | Improved over baselines | Strong | High (direction constraints help) |

| Departures | State-of-the-art | State-of-the-art | State-of-the-art | Strong (direct distribution alignment) | Moderate |

| River | Not reported (spatial focus) | Not reported (spatial focus) | Not reported (spatial focus) | Strong cross-tissue | High |

| CPA | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Limited (static mappings) | High |

| CellOT | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Limited (discrete transitions) | Moderate |

DC-DSB demonstrates particular strength in generalization to unseen perturbation combinations, outperforming baseline methods including CPA and CellOT on benchmark datasets such as K562, RPE1, and Adamson [31]. Its trajectory-based approach captures dynamic gene expression changes more effectively than static mapping methods, enabling discovery of synergistic and antagonistic gene interactions. Departures achieves state-of-the-art performance on both genetic and drug perturbation datasets by directly aligning distributions rather than relying on latent space interpolation [32].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Benchmark Dataset Composition

Rigorous model evaluation employs several publicly available single-cell perturbation datasets with distinct characteristics:

K562 and RPE1 Datasets: Comprehensive perturbation compendia featuring 1,092 and 1,543 conditions respectively, spanning approximately 5,000 genes and ~160,000 cells, ideal for testing generalization to unseen perturbations [31].

Adamson Dataset: Focused on 87 perturbation conditions targeting the unfolded protein response, with 68,000 cells and 5,060 genes, including metadata on perturbation type, dosage, and cell type [31].

Norman Dataset: Contains 131 two-gene perturbations across ~90,000 cells, specifically designed for evaluating combinatorial perturbation predictions [31].

Experimental protocols typically employ a holdout validation strategy where models are trained on a subset of perturbations and tested on held-out perturbation conditions to assess generalization capability. Performance is quantified using expression prediction accuracy, correlation of gene expression values, and conservation of co-expression structures.

DC-DSB Implementation Workflow

The DC-DSB framework implements a structured workflow for perturbation trajectory modeling:

Diagram 1: DC-DSB Experimental Workflow (87 characters)

The DC-DSB framework begins with single-cell data preprocessing and condition annotation, followed by integration of biological prior knowledge from gene ontology databases and established pathways. The model then applies direction constraints based on perturbation type before training through path-space KL divergence minimization. This generates probabilistic trajectories that can be validated experimentally and analyzed for disease module relevance.

Performance Validation Methodologies

Model validation employs multiple complementary approaches:

Expression Accuracy Metrics: Root mean square error (RMSE) and Pearson correlation between predicted and experimentally measured gene expression values [31].