From Networks to Cures: How Systems Biology is Powering the Personalized Medicine Revolution

This article explores the transformative role of systems biology in advancing personalized medicine, moving beyond the 'one-size-fits-all' treatment model.

From Networks to Cures: How Systems Biology is Powering the Personalized Medicine Revolution

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of systems biology in advancing personalized medicine, moving beyond the 'one-size-fits-all' treatment model. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details how integrative approaches—including multi-omics data integration, AI-driven computational modeling, and Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP)—are used to decode complex disease mechanisms and predict individual patient responses. The content covers foundational concepts, key methodologies and their therapeutic applications, strategies to overcome translational and technical challenges, and the frameworks for validating these approaches through industry-academia collaboration and real-world evidence. The synthesis provides a roadmap for leveraging systems biology to develop next-generation, patient-specific diagnostics and therapies.

The Systems View of Biology: Laying the Foundation for Personalized Medicine

For decades, drug discovery has been dominated by a reductionist paradigm that seeks to identify single molecular targets responsible for disease pathology. This "one drug–one target" approach, while successful for infectious diseases and conditions with well-defined molecular etiology, has demonstrated significant limitations when applied to complex multifactorial diseases such as cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and metabolic syndromes [1]. These diseases involve intricate interactions across gene regulatory networks, protein-protein interactions, and signaling pathways with redundant mechanisms that diminish the efficacy of single-target therapies [2]. The consequences of this limitation are quantifiable: drugs developed through conventional approaches experience clinical trial failure rates of 60–70%, partly due to insufficient understanding of complex biological interactions [1].

The emerging discipline of systems biology has facilitated a fundamental shift toward viewing human physiology and pathology through the lens of interconnected biological networks. This paradigm shift recognizes that diseases manifest from perturbations in complex molecular networks rather than isolated defects in single molecules [3] [4]. Network medicine, which integrates systems biology, network science, and computational approaches, provides a framework for understanding the organizational principles of human pathobiology and has begun to reveal that disease-associated perturbations occur within connected microdomains (disease modules) of molecular interaction networks [4]. This holistic perspective enables researchers to explore drug-disease relationships at a network level, providing insights into how drugs act on multiple targets within biological systems to modulate disease progression [3].

Theoretical Foundations: From Single Targets to Network Therapeutics

Core Principles of Network Pharmacology

Central to the paradigm shift is network pharmacology, an interdisciplinary field that integrates systems biology, bioinformatics, and pharmacology to understand sophisticated interactions among drugs, targets, and disease modules in biological networks [1]. Unlike traditional pharmacology's single-target focus, network pharmacology views diseases as the result of complex molecular interactions, where multiple targets are involved simultaneously [3]. The theoretical foundation was significantly advanced by the proposal of network target theory by Li et al. in 2011, which addressed the limitations of traditional single-target drug discovery by proposing that the disease-associated biological network itself should be viewed as the therapeutic target [3].

This theory posits that diseases emerge from perturbations in complex biological networks, and effective therapeutic interventions should target the disease network as a whole. Network targets include various molecular entities such as proteins, genes, or pathways that are functionally associated with disease mechanisms, and their interactions form a dynamic network that determines disease progression and therapeutic responses [3]. This perspective represents a fundamental departure from traditional approaches by conceptualizing therapeutic intervention as a modulation of network states rather than simple inhibition or activation of individual targets.

Key Conceptual Differences Between Paradigms

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional Pharmacology vs. Network Pharmacology

| Feature | Traditional Pharmacology | Network Pharmacology |

|---|---|---|

| Targeting Approach | Single-target | Multi-target / network-level |

| Disease Suitability | Monogenic or infectious diseases | Complex, multifactorial disorders |

| Model of Action | Linear (receptor-ligand) | Systems/network-based |

| Risk of Side Effects | Higher (off-target effects) | Lower (network-aware prediction) |

| Failure in Clinical Trials | Higher (60-70%) | Lower due to pre-network analysis |

| Technological Tools Used | Molecular biology, pharmacokinetics | Omics data, bioinformatics, graph theory |

| Personalized Therapy | Limited | High potential (precision medicine) |

Methodological Framework: Computational Approaches and Experimental Design

Network Construction and Analysis Protocols

The implementation of network pharmacology follows a systematic workflow that begins with data retrieval and curation from established biological databases. Essential data sources include DrugBank and PubChem for drug-related information, DisGeNET and OMIM for disease-associated genes, and STRING and BioGRID for protein-protein interactions [1]. Following data collection, researchers construct multi-layered biological networks including drug-target, target-disease, and protein-protein interaction maps using tools such as Cytoscape and NetworkX [1].

A critical step in the process involves topological and module analysis using graph-theoretical measures. Key metrics include degree centrality (number of connections), betweenness (influence over information flow), closeness (efficiency in accessing other nodes), and eigenvector centrality (influence based on connections to other influential nodes) [5]. These analyses help identify hub nodes and bottleneck proteins that play disproportionately important roles in network stability and function. Community detection algorithms like MCODE and Louvain are subsequently applied to identify functional modules within the networks, which are then subjected to enrichment analysis using tools such as DAVID and g:Profiler to determine overrepresented pathways and biological processes [1].

Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Data in Parameter Identification

Systems biology models often face challenges in parameter estimation due to limited quantitative data. A sophisticated approach addresses this limitation by converting qualitative biological observations into inequality constraints on model outputs [6]. For example, qualitative data such as "activating or repressing" or "viable or inviable" can be formalized as inequality constraints, which are then combined with quantitative measurements in a single objective function:

f_tot(x) = f_quant(x) + f_qual(x)

where f_quant(x) represents the sum-of-squares distance from quantitative data points, and f_qual(x) represents penalty terms for violation of qualitative constraints [6]. This approach enables researchers to incorporate diverse data types, such as both quantitative time courses and qualitative phenotypes of mutant strains, to perform automated identification of numerous model parameters simultaneously [6].

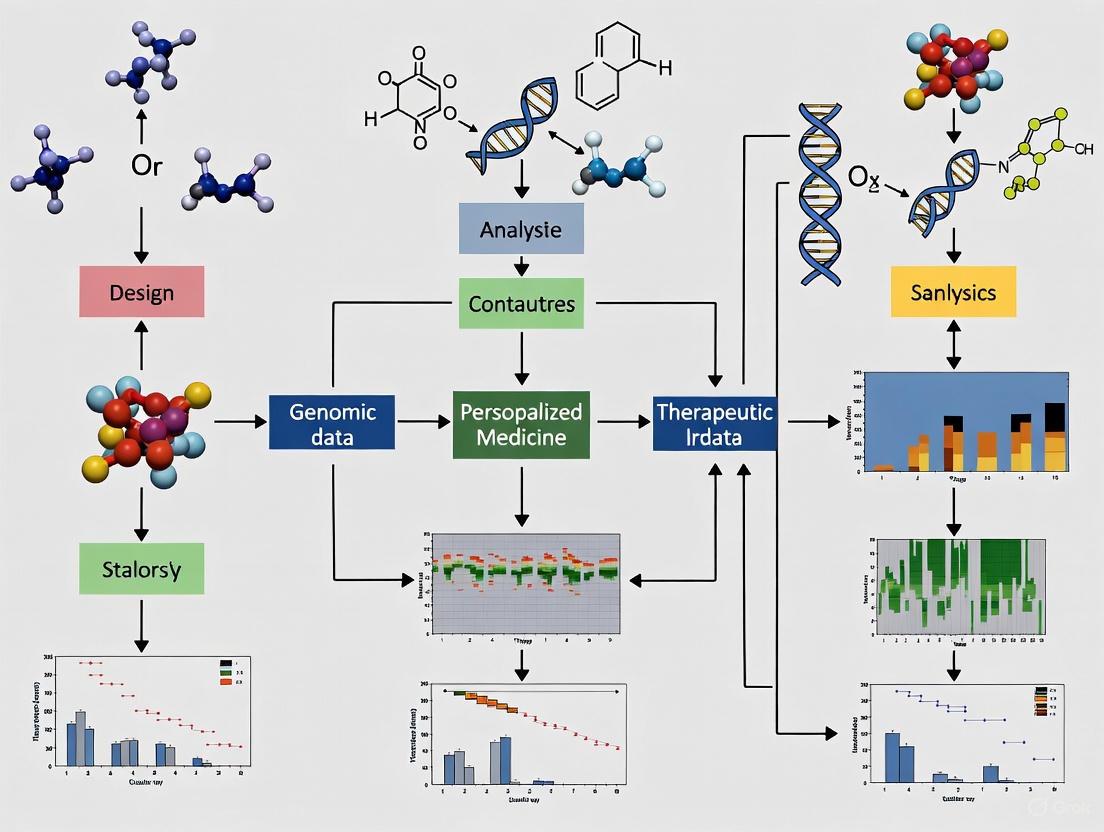

Network Analysis Workflow

Predictive Modeling and Validation Frameworks

Advanced machine learning algorithms including support vector machines (SVM), random forests (RF), and graph neural networks (GNN) are trained on specialized datasets to predict novel drug-target interactions [1]. The performance of these models is rigorously evaluated using cross-validation and metrics such as AUC (Area Under the Curve) and accuracy [3]. Promising predictions are subsequently validated through molecular docking simulations and experimental methodologies including surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) for in vitro validation [1].

A notable example of this approach is found in a 2025 transfer learning model based on network target theory that integrated deep learning techniques with diverse biological molecular networks to predict drug-disease interactions [3]. This model achieved an AUC of 0.9298 and an F1 score of 0.6316 in predicting drug-disease interactions, successfully identifying 88,161 relationships involving 7,940 drugs and 2,986 diseases [3]. Furthermore, the algorithm demonstrated exceptional capability in predicting drug combinations, achieving an F1 score of 0.7746 after fine-tuning, and accurately identified two previously unexplored synergistic drug combinations for distinct cancer types [3].

Advanced Applications in Personalized Medicine

Contextualized Network Modeling for Individual Patient Profiles

A groundbreaking approach developed by Carnegie Mellon University researchers introduces contextualized modeling, a family of ultra-personalized machine learning methods that build individualized gene network models for specific patients [7]. This methodology addresses a fundamental limitation of traditional modeling approaches, which require large patient populations to produce a single model and consequently lump together patients with potentially important biological differences [7].

Contextualized models overcome this limitation by generating individualized network models based on each patient's unique molecular profile, or context. These models consider thousands of contextual factors simultaneously and automatically determine which factors are important for differentiating patients and understanding diseases [7]. In a landmark study, researchers applied this approach to build personalized models for nearly 8,000 tumors across 25 cancer types, identifying previously hidden cancer subtypes and improving survival predictions, particularly for rare cancers [7]. The generative nature of these models enables researchers to produce models on demand for new contexts, including predicting gene behavior in types of tumors they had never previously encountered [7].

Network-Based Drug Repurposing and Combination Therapy

Network pharmacology enables systematic drug repurposing by mapping the network proximity between drug targets and disease modules within molecular interaction networks [4]. The recently recognized extraordinary promiscuity of drugs for multiple protein targets provides a rational basis for this strategy [4]. The potential of this approach has been demonstrated across numerous conditions, from coronary artery disease to Covid-19 [4].

Beyond single-drug repurposing, network approaches facilitate the design of rational combination therapies that simultaneously target multiple nodes in disease networks. Tools from network medicine can investigate the impact of complex combinations of small molecules found in food on the human molecular interaction network, potentially leading to mechanism-based nutritional interventions and food-inspired therapeutics [4]. This approach is particularly valuable for understanding traditional medicine formulations, such as Traditional Chinese Medicine, where multi-component formulae act on multiple targets simultaneously [2] [1].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Network-Based Prediction Models

| Model Type | Application | Performance Metrics | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer Learning Model [3] | Drug-disease interaction prediction | AUC: 0.9298, F1 score: 0.6316 | Identified 88,161 drug-disease interactions |

| Fine-tuned Combination Prediction [3] | Synergistic drug combination | F1 score: 0.7746 | Discovered two novel cancer drug combinations |

| Contextualized Network Model [7] | Personalized cancer modeling | Improved survival prediction | Identified hidden thyroid cancer subtype with worse prognosis |

Computational Tools and Biological Databases

Implementing network pharmacology requires specialized computational tools and comprehensive biological databases. The table below summarizes essential resources for constructing and analyzing biological networks.

Table 3: Research Toolkit for Network Pharmacology

| Category | Tool/Database | Functionality |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Information | DrugBank, PubChem, ChEMBL | Drug structures, targets, pharmacokinetics |

| Gene-Disease Associations | DisGeNET, OMIM, GeneCards | Disease-linked genes, mutations, gene function |

| Target Prediction | Swiss Target Prediction, SEA | Predicts protein targets from compound structures |

| Protein-Protein Interactions | STRING, BioGRID, IntAct | Protein interaction networks, functional associations |

| Pathway Analysis | KEGG, Reactome | Pathway mapping, biological process annotation |

| Network Visualization & Analysis | Cytoscape, NetworkX, Gephi | Network construction, visualization, topological analysis |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | DeepPurpose, DeepDTnet | Prediction of drug-target interactions |

Experimental Validation Techniques

While computational predictions form the foundation of network pharmacology, experimental validation remains essential for translational applications. Key validation methodologies include:

- Molecular Docking Simulations: Tools such as AutoDock Vina and Glide predict binding affinities between drug compounds and target proteins [1].

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): Measures real-time binding kinetics and affinity between molecules [1].

- In Vitro Validation: Includes qPCR for gene expression analysis, cytotoxicity assays for drug efficacy testing [3], and specialized assays for pathway modulation.

- Multi-omics Integration: Approaches such as multi-omics factor analysis (MOFA) integrate genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to create comprehensive, patient-specific models [1].

Personalized Network Therapy

The paradigm shift from single-target drugs to biological network models represents a fundamental transformation in how we understand and treat disease. This approach moves beyond the reductionist view of focusing on individual molecular targets to embrace the complexity of biological systems and their emergent properties. The integration of systems biology with network science and artificial intelligence has enabled the development of predictive models of disease mechanisms and therapeutic interventions that account for the interconnected nature of biological processes [4].

The future of network-based approaches will likely involve even deeper integration of multi-scale biological information, from molecular interactions to organ-level and organism-level networks [4]. Emerging technologies such as total-body PET imaging can provide insights into interorgan communication networks, potentially enabling the creation of whole-organism interactomes for functional and therapeutic analysis [4]. Furthermore, as single-cell technologies advance, we can anticipate the development of cell-type-specific network models that capture the extraordinary heterogeneity of biological systems.

For researchers and drug development professionals, embracing this paradigm shift requires familiarity with both computational and experimental approaches. The successful implementation of network pharmacology depends on interdisciplinary collaboration across systems biology, bioinformatics, pharmacology, and clinical medicine. As these approaches mature, they hold the promise of truly personalized, precision medicine based on comprehensive understanding of individual network perturbations and targeted interventions to restore physiological balance.

Integrative Pharmacology and Systems Therapeutics represent a paradigm shift in biomedical research, moving away from a reductionist focus on single drug targets toward a holistic understanding of drug action within complex biological systems. Integrative Pharmacology is defined as the systematic investigation of drug interactions with biological systems across molecular, cellular, organ, and whole-organism levels, combining traditional pharmacology with signaling pathways, bioinformatic tools, and multi-omics data [8]. This approach aims to improve understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of human diseases by elucidating complete mechanisms of action and predicting therapeutic targets and effects [8].

Systems Therapeutics, in parallel, defines where pharmacologic processes and pathophysiologic processes interact to produce clinical therapeutic responses [9]. It provides a framework for understanding how drugs modulate biological networks rather than isolated targets, with the overarching goal of discovering and verifying novel treatment targets and candidate therapeutics for diseases based on understanding molecular, cellular, and circuit mechanisms [10]. The integration of these two disciplines enables researchers to address the complexity of therapeutic interventions in a more comprehensive manner, ultimately accelerating the development of safer and more effective personalized treatments.

The Framework of Systems Therapeutics

The organizing principle of Systems Therapeutics involves two parallel processes—pharmacologic and pathophysiologic—that interact at different biological levels to produce therapeutic outcomes [9]. A systematic diagram illustrates this framework consisting of two rows of four parallel systems components representing different biologic levels of interaction.

Core Components and Processes

The pharmacologic process begins with a pharmacologic agent (drug) interacting with a pharmacologic response element (e.g., receptor, drug target) [9]. This initial interaction initiates a pharmacologic mechanism via signal transduction, which progresses to a pharmacologic response at the tissue/organ level via pharmacodynamics, and finally translates to a clinical (pharmacologic) effect at the whole-body level [9].

The pathophysiologic process is initiated by an intrinsic operator, a hypothetical endogenous entity originating in a diseased organ's principal cell type that interacts with and influences an etiologic causative factor (e.g., genetic mutation, protein abnormality) via disease preindication [9]. This leads to initiation of a pathogenic pathway via disease initiation, which progresses to a pathophysiologic process at the tissue/organ level via pathogenesis, and finally manifests as a disease manifestation at the clinical level via progression [9].

The therapeutic response is determined by how the clinical (pharmacologic) effect moderates the disease manifestation, regardless of the biologic level at which the pivotal interaction occurs [9].

Diagram Title: Systems Therapeutics Framework

Systems Therapeutics Categories and Examples

The Systems Therapeutics framework defines four distinct categories based on the biological level at which the pivotal interaction between pharmacologic and pathophysiologic processes occurs [9]. Each category represents a different therapeutic strategy with characteristic drug classes and mechanisms.

Table 1: Systems Therapeutics Categories and Examples

| Category | Pivotal Interaction Level | Definition | Therapeutic Approach | Drug Examples | Indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category I | Molecular Level: Elements/Factors | Interaction between pharmacologic response element and etiologic causative factor | Molecular-based therapy targeting primary molecular entities | Ivacaftor (Kalydeco), Imatinib (Gleevec) | Cystic Fibrosis, Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia |

| Category II | Cellular Level: Mechanisms/Pathways | Interaction involving fundamental biochemical mechanism related to disease evolution | Metabolism-based therapy interfering with biochemical mechanisms | Atorvastatin (Lipitor), Adalimumab (Humira) | Hypercholesterolemia, Rheumatoid Arthritis |

| Category III | Tissue/Organ Level: Responses/Processes | Modulation of physiologic function linked to disease evolution | Function-based therapy modulating normal physiologic functions | Irbesartan (Avapro), Tadalafil (Cialis) | Hypertension, Male Erectile Dysfunction |

| Category IV | Clinical Level: Effects/Manifestations | Effect directed at clinical symptoms rather than disease cause | Symptom-based therapy providing symptomatic or palliative treatment | Acetaminophen (Tylenol), Ibuprofen (Advil) | Fever, Pain, Inflammation |

Category I: Molecular-Level Therapeutics

Category I represents the most fundamental level of therapeutic intervention, where drugs interact directly with the etiologic causative factors of disease [9]. This category includes replacement therapies such as enzyme replacement (e.g., idursulfase for Hunter Syndrome) and protein replacement (e.g., recombinant Factor VIII for Hemophilia A), as well as therapies that potentiate defective proteins (e.g., ivacaftor for Cystic Fibrosis) or inhibit abnormal enzymes (e.g., imatinib for Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia) [9]. These interventions target the primary molecular abnormalities responsible for disease pathogenesis, offering potentially transformative treatments for genetic and molecular disorders.

Categories II-IV: Cellular to Clinical Level Therapeutics

Category II interventions target biochemical mechanisms and pathways central to disease evolution, though not necessarily etiologic pathways [9]. Examples include HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) for hypercholesterolemia, TNF-α inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis, and xanthine oxidase inhibitors for hyperuricemia and gout [9]. Category III therapeutics operate at the tissue/organ level by modulating normal physiologic functions linked to disease evolution, such as angiotensin II receptor blockers for hypertension and PDE-5 inhibitors for erectile dysfunction [9]. Category IV represents symptom-based therapies that alleviate clinical manifestations without directly targeting disease causes, including antipyretics, analgesics, and antitussives [9].

Methodological Approaches in Integrative Pharmacology

Integrative Experimental Strategies

Integrative Pharmacology employs a hierarchical experimental approach that connects in vitro findings with in vivo outcomes through progressively complex model systems [11]. This methodology acknowledges that isolated molecules and cells in vitro do not necessarily reflect properties they possess in vivo and cannot adequately capture intact tissue, organ, and system functions [12]. The National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) defines Integrative and Organ Systems Pharmacology as "pharmacological research using in vivo animal models or substantially intact organ systems that are able to display the integrated responses characteristic of the living organism that result from complex interactions between molecules, cells, and tissues" [12].

The experimental workflow typically progresses from in vitro systems (cell cultures, biochemical assays) to ex vivo models (isolated organs, tissue slices) and finally to in vivo models that recapitulate human clinical conditions [11]. This sequential approach allows researchers to establish connections between in vitro mechanisms and in vivo outcomes while accounting for the complex interactions that emerge at each level of biological organization [12]. Advanced tools such as microdialysis, imaging methods, and multi-omic technologies enhance the collection and interpretation of pharmacological data obtained from these integrated experimental systems [12].

Diagram Title: Integrative Pharmacology Workflow

Systems Biology and Multi-Omic Integration

Integrative Pharmacology leverages systems biology approaches and multi-omic technologies to understand drug actions within biological networks [13] [14]. This involves the application of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, epigenomic, and microbiomic data to construct comprehensive models of drug-target interactions and physiological responses [8]. Blood is particularly valuable as a window into health and disease because it bathes all organs and contains molecules secreted by these organs, providing readouts of their behavior [15].

The integrative Personal Omics Profile (iPOP) approach exemplifies this strategy by combining genomic information with longitudinal monitoring of transcriptomes, proteomes, and metabolomes to capture personalized physiological state changes during health and disease transitions [13]. This method has demonstrated utility in detecting early disease onset and monitoring responses to interventions, serving as a proof-of-principle for predictive and preventative medicine [13]. Additional omics profiles such as gut microbiome, microRNA, and immune receptor repertoire provide complementary layers of biological information for personalized health monitoring and therapeutic optimization [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Materials

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Systems | Genetically engineered mouse models, Primary cell cultures, Human organoids, Tissue engineering scaffolds | Recapitulate human disease conditions for therapeutic testing | Species differences, Genetic stability, Physiological relevance, Ethical considerations |

| Omics Technologies | Whole genome/exome sequencing kits, RNA/DNA extraction kits, Mass spectrometry reagents, Microarray platforms | Comprehensive molecular profiling for systems-level analysis | Data integration challenges, Batch effects, Normalization methods, Computational requirements |

| Drug Delivery Systems | Nanoparticles (polymeric, lipid-based), Stimuli-responsive biomaterials, Implantable devices, Targeting ligands | Enhanced specificity, Localized delivery, Controlled release kinetics | Biocompatibility, Scalability, Release profile characterization, Sterilization requirements |

| Analytical Tools | Microdialysis probes, Biosensors, Wearable monitoring devices, High-resolution imaging agents | Real-time monitoring of physiological and pharmacological parameters | Temporal resolution, Sensitivity limits, Calibration requirements, Signal-to-noise optimization |

| Computational Resources | Network analysis software, PK/PD modeling platforms, AI/ML algorithms, Data integration frameworks | Predictive modeling of drug effects, Network pharmacology analysis, Personalized dosing optimization | Data standardization, Algorithm validation, Computational power, Interoperability challenges |

| PROTAC BRM degrader-1 | PROTAC BRM degrader-1, MF:C57H69N11O8S, MW:1068.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Gly-Mal-GGFG-Deruxtecan 2-hydroxypropanamide | Gly-Mal-GGFG-Deruxtecan 2-hydroxypropanamide, MF:C52H55FN10O15, MW:1079.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Integration with Personalized Medicine and Systems Biology

Integrative Pharmacology and Systems Therapeutics fundamentally contribute to personalized medicine by providing frameworks to understand individual variations in drug response and disease manifestations [13] [15]. The combination of personal genomic information with longitudinal monitoring of molecular components that reflect real-time physiological states enables predictive and preventative medicine approaches [13]. Dr. Lee Hood's concept of P4 medicine—predictive, preventive, personalized, and participatory—exemplifies this integration, representing a shift from symptom-based diagnosis and treatment to continuous health monitoring and early intervention [15].

Systems biology provides the methodological foundation for this integration by enabling comprehensive analysis of biological systems through global profiling of multiple data types [13] [15]. The convergence of high-throughput technologies, computational modeling, and multi-omic data integration allows researchers to examine the interconnected nature of biological systems and their responses to therapeutic interventions [13]. This approach is particularly valuable for understanding complex diseases that involve multiple interacting pathways and systems, such as cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and metabolic conditions [13] [14].

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are increasingly important in analyzing the complex datasets generated by integrative pharmacological studies [8]. These computational approaches can identify patterns and relationships within multi-omic data, predict drug responses, optimize therapeutic combinations, and guide personalized treatment strategies [8]. The ongoing development of these analytical tools, combined with advances in experimental technologies, continues to enhance the precision and predictive power of Integrative Pharmacology and Systems Therapeutics.

The staggering molecular heterogeneity of human diseases, particularly cancer, demands innovative approaches beyond traditional single-omics methods [16]. Multi-omics integration represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research, enabling the collection and analysis of large-scale datasets across multiple biological layers—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics [17]. This approach provides global insights into biological processes and holds great promise in elucidating the myriad molecular interactions associated with complex human diseases [17] [16].

The clinical imperative for multi-omics integration stems from the limitations of reductionist approaches. Traditional methods reliant on single-omics snapshots or histopathological assessment alone fail to capture cancer's interconnected biological complexity, often yielding incomplete mechanistic insights and suboptimal clinical predictions [16]. Multi-omics profiling systematically integrates diverse molecular data to construct a comprehensive and clinically relevant understanding of disease biology, recovering system-level signals that are often missed by single-modality studies [18] [16]. This framework is transforming precision oncology from reactive population-based approaches to proactive, individualized care [16].

Computational Methods for Multi-Omics Integration

Strategy Spectrum: From Conceptual to Network-Based Integration

The integration of multi-omics data presents significant challenges due to high dimensionality, heterogeneity, and technical variability [17] [16]. Based on data type, quality, and biological questions, researchers employ distinct integration strategies:

Table 1: Multi-Omics Integration Strategies

| Integration Type | Core Methodology | Applications | Tools/Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Integration | Utilizes existing databases and knowledge bases to associate different omics data by shared concepts or entities | Hypothesis generation, functional annotation | STATegra, OmicsON [19] |

| Statistical Integration | Employs correlation analysis, regression modeling, clustering, or classification to extract patterns and trends | Identifying gene-protein co-expression relationships, drug response prediction | Seurat WNN, Harmony [19] [20] |

| Model-Based Integration | Leverages network models or pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic simulations to simulate biological system behavior | Understanding system dynamic regulation mechanisms | Graph neural networks [19] [16] |

| Network & Pathway Integration | Constructs protein-protein interaction networks or metabolic pathways to integrate multi-omics data across different layers | Revealing complex molecular interaction networks, identifying key regulatory hubs | GLUE, MIDAS [19] [20] |

Artificial Intelligence and Novel Computational Frameworks

Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), has emerged as the essential scaffold bridging multi-omics data to clinical decisions [16]. Unlike traditional statistics, AI excels at identifying non-linear patterns across high-dimensional spaces, making it uniquely suited for multi-omics integration [16].

Deep Learning Approaches include specialized architectures such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) that automatically quantify immunohistochemistry staining with pathologist-level accuracy, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) that model protein-protein interaction networks perturbed by somatic mutations, and multi-modal transformers that fuse MRI radiomics with transcriptomic data to predict disease progression [16]. The SWITCH deep learning method exemplifies innovation in this space, utilizing deep neural networks to learn complex relationships between different omics data types by mapping them to a common latent space where they can be effectively compared and integrated [21].

Single-Cell Multi-Modal Integration represents a particularly advanced frontier. Recent benchmarking efforts have evaluated 40 software packages encompassing 65 integration algorithms for processing RNA and ATAC (high-dimensional), ADT (protein, low-dimensional), and spatial genomics data [20]. In modality-matched integration tasks, Seurat's Weighted Nearest Neighbors (WNN) algorithm demonstrates superior performance for RNA+ATAC and RNA+ADT integration, while in scenarios with partial or complete missing modality matches, deep generative models like MIDAS and GLUE excel at cross-modal imputation and alignment [20].

Universal AI Models represent another groundbreaking approach. Researchers have developed a general AI model that employs a multi-task architecture to jointly predict diverse genomic modalities including chromatin accessibility, transcription factor binding, histone modifications, nascent RNA transcription, and 3D genome structure [22]. This model contains three key components—task-shared local encoders, task-shared global encoders, and task-specific prediction heads—and can be trained using innovative strategies like task scheduling, task weighting, and partial label learning [22].

Multi-Omics Applications in Clinical Research and Therapeutics

Biomarker Discovery and Patient Stratification

Multi-omics integration enables the identification of novel biomarkers and patient stratification approaches that would be impossible with single-omics data alone. By integrating genetic data with insights from other omics technologies, researchers can provide a more comprehensive view of an individual's health profile [23].

Liquid Biopsies exemplify the clinical impact of multi-omics, analyzing biomarkers like cell-free DNA (cfDNA), RNA, proteins, and metabolites non-invasively [23] [16]. Recent improvements have enhanced their sensitivity and specificity, advancing early disease detection and treatment monitoring [23]. While initially focused on oncology, liquid biopsies are expanding into other medical domains, further solidifying their role in personalized medicine through multi-analyte integration [23]. Technologies like ApoStream enable the capture of viable whole cells from liquid biopsies, preserving cellular morphology and enabling downstream multi-omic analysis when traditional biopsies aren't feasible [18].

Cancer Subtyping and Prognosis has been revolutionized by multi-omics approaches. Integrated classifiers report AUCs of 0.81–0.87 for challenging early-detection tasks, significantly outperforming single-modality biomarkers [16]. In breast cancer, multi-omics analysis helps predict patient survival and drug response, while in brain tumors like glioma, integrating MRI radiomics with transcriptomic data enables more accurate progression prediction [19] [16].

Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Optimization

Multi-omics approaches are accelerating drug discovery and enabling more targeted therapeutic strategies across multiple disease areas:

- Target Identification: Multi-omics can identify new drug targets by integrating gene, protein, metabolite, and epigenetic information to construct disease and drug action mechanism networks, allowing prioritized screening of potential targets [19].

- Drug Response Prediction: Analysis of individual variations in drug response helps identify genetic, transcriptional, protein, and metabolic factors affecting efficacy and toxicity [19]. Machine learning models (random forests, SVMs, neural networks) can predict individualized efficacy and safe dosage, advancing precision medicine [19].

- CRISPR and Gene Therapy: Multi-omic data drives the next generation of cell and gene therapy approaches, including CRISPR-based treatments [23]. New solutions like Perturb-seq enable functional genomics at single-cell resolution, allowing unprecedented insight into drug mechanisms of action and genetic disease treatments [24].

Table 2: Multi-Omics Applications in Disease Research

| Disease Area | Multi-Omics Approach | Key Findings/Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Oncology | Integration of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data | Therapy selection, proteogenomic early detection, radiogenomic non-invasive diagnostics [16] |

| Neurodegenerative Disorders | Multi-omics analysis of brain tissue from ASD and Parkinson's patients | Risk gene function analysis, identification of potential therapeutic targets [19] |

| Rare Genetic Diseases | Whole genome sequencing with epigenomic analysis | Rapid diagnosis, identification of structural variants, development of antisense oligonucleotides [24] |

| Metabolic Diseases | Host tissue and microbiome data integration | Revealing how microbes affect host metabolism, immunity, and behavior [19] |

Experimental Workflows and Research Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful multi-omics research requires specialized reagents and platforms designed to handle the complexity of integrating multiple data types from the same biological sample:

- Single-Cell Multi-Omic Profiling: Technologies like Illumina's Single Cell and Perturb-seq solutions support the analysis of transcriptomics alongside protein expression or CRISPR perturbations at single-cell resolution, with scalability from 10,000 to 1,000,000 cells per sample [24].

- Spatial Transcriptomics: Platforms enabling spatial resolution of gene expression within tissue architecture, with newer technologies offering nine times larger capture area and four times higher resolution than previous standards [24].

- 5-Base Methylation Analysis: Solutions allowing simultaneous genetic variant and methylation detection in a single assay, providing insights into how DNA methylation patterns affect gene expression timing in development, cell differentiation, and tumor progression [24].

- Multi-Omic Analysis Software: Integrated platforms like Illumina Connected Multiomics (ICM) provide seamless workflows from sample to insight, allowing researchers without bioinformatics backgrounds to explore and analyze multi-modal datasets [24].

Technical Protocols for Multi-Omics Integration

Protocol 1: Universal AI Model for Multi-Omics Prediction

This protocol outlines the methodology for developing a universal AI model capable of predicting diverse genomic modalities from ATAC-seq and DNA sequence inputs [22]:

- Input Preparation: Process 600kb DNA sequences with corresponding ATAC-seq data. Split into 1kb genomic intervals with 300bp flanking regions on each side.

- Local Feature Extraction: Use task-shared local encoders to extract local sequence features from each 1kb interval, generating local sequence representation vectors.

- Global Dependency Modeling: Process local sequence representations through global encoders containing convolutional layers and seven transformer encoder layers to model long-range dependencies across the entire 600kb region.

- Task-Specific Prediction: Employ task-specific prediction heads for different genomic modalities (TF binding, histone modifications, RNA transcription, 3D structure).

- Training Strategy: Implement three specialized training approaches:

- Task Scheduling: Use curriculum learning to gradually introduce different genomic modalities, starting with tasks relying on local sequence information before progressing to those requiring long-range interactions.

- Task Weighting: Dynamically adjust loss weights for different prediction tasks.

- Partial Label Learning: Handle missing data across modalities efficiently.

- Cross-Species Adaptation: Transfer learning from human to mouse models by retraining with species-specific data.

Protocol 2: Single-Cell Multi-Modal Integration Benchmarking

This protocol describes the comprehensive benchmarking of single-cell multi-modal integration algorithms [20]:

- Data Collection and Curation: Assemble diverse single-cell multi-modal datasets encompassing RNA+ATAC (high-dimensional), RNA+ADT (protein, low-dimensional), and spatial genomics data.

- Task Definition: Establish six benchmark evaluation tasks based on data type and pairing: paired integration, unpaired mosaic integration, unpaired diagonal integration, and spatial multi-omics tasks.

- Algorithm Evaluation Framework: Implement three-dimensional assessment metrics:

- Usability: Test algorithms across different dataset sizes (500 to 500,000 cells) and hardware platforms (CPU/GPU).

- Accuracy: Evaluate biological structure preservation, batch effect removal, cell alignment, and cross-modal generation accuracy using latent space metrics.

- Stability: Assess performance consistency across multiple runs and with varying dataset qualities.

- Performance Comparison: Execute 65 integration algorithms across 40 software packages using standardized preprocessing and evaluation pipelines.

- Web Server Deployment: Create user-friendly web interfaces for result exploration and algorithm selection based on specific data processing needs.

Multi-omics integration represents a transformative approach in biomedical research, moving beyond theoretical methods to demonstrate tangible impact in biomarker discovery, patient stratification, and therapeutic interventions [17]. The field continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping its future trajectory. Spatial and single-cell multi-omics are providing unprecedented resolution for decoding tissue microenvironments and cellular heterogeneity [16]. Federated learning approaches enable privacy-preserving collaboration across institutions, addressing data governance concerns while leveraging diverse datasets [16]. Explainable AI (XAI) techniques like SHAP are making "black box" models more interpretable, clarifying how genomic variants contribute to clinical outcomes and building trust for clinical implementation [16]. Perhaps most promising is the movement toward patient-centric "N-of-1" models and generative AI for synthesizing in silico "digital twins"—patient-specific avatars that simulate treatment response and enable truly personalized therapeutic optimization [16].

Despite remarkable progress, operationalizing multi-omics integration requires confronting ongoing challenges in algorithm transparency, batch effect robustness, ethical equity in data representation, and regulatory alignment [16]. Standardizing methodologies and establishing robust protocols for data integration remain crucial for ensuring reproducibility and reliability [23]. The massive data output of multi-omics studies continues to demand scalable computational tools and collaborative efforts to improve interpretation [23]. Moreover, engaging diverse patient populations is vital to addressing health disparities and ensuring biomarker discoveries are broadly applicable across different ethnic and socioeconomic groups [23]. Looking ahead, collaboration among academia, industry, and regulatory bodies will be essential to drive innovation, establish standards, and create frameworks that support the clinical application of multi-omics [23]. By addressing these challenges, multi-omics research will continue to advance personalized medicine, offering deeper insights into human health and disease and ultimately fulfilling the promise of precision medicine—matching the right treatment to the right patient at the right time.

Systems biology represents a fundamental shift in biological research, moving from a reductionist study of individual components to an integrative analysis of complex systems. This discipline serves as a critical bridge, connecting the abstract world of computational modeling with the empirical reality of molecular biology. By constructing quantitative models that simulate the dynamic behavior of biological networks, systems biology provides a powerful framework for understanding how molecular interactions give rise to cellular and organismal functions. This approach has become indispensable in the era of personalized medicine, where predicting individual patient responses to therapeutics requires a sophisticated understanding of the complex, interconnected pathways that vary between individuals.

The foundational power of systems biology lies in its ability to formalize biological knowledge into computable representations. As noted in research on model similarity, systems biology models establish "a modelling relation between a formal and a natural system: the formal system encodes the natural system, and inferences made in the formal system can be interpreted (decoded) as statements about the natural system" [25]. This encoding/decoding process enables researchers to move beyond qualitative descriptions to quantitative predictions of system behavior, creating a genuine bridge between disciplines that traditionally operated in separate scientific domains.

Within personalized medicine research, this integrative approach is particularly valuable. The unifying paradigm of Integrative and Regenerative Pharmacology (IRP) exemplifies this trend, merging pharmacology, systems biology, and regenerative medicine to develop transformative curative therapeutics rather than merely managing symptoms [8]. This approach leverages the rigorous tools of systems biology—including omics technologies, bioinformatic analyses, and computational modeling—to understand drug mechanisms of action at multiple biological levels and develop targeted interventions capable of restoring physiological structure and function.

Core Methodologies: Combining Computational and Experimental Techniques

Quantitative Modeling Paradigms for Biological Systems

Selecting appropriate modeling paradigms is crucial for generating biologically meaningful insights. Different biological scales and system characteristics demand distinct computational approaches, each with specific strengths and limitations for personalized medicine applications [26]:

Deterministic Modeling using ordinary differential equations (ODEs) works well for systems with high molecular abundances and predictable behaviors, typically at macroscopic scales. These models assume continuous concentration changes and yield identical results for identical parameters, making them suitable for simulating population-level phenomena or dense intracellular networks where stochastic effects average out.

Stochastic Modeling approaches, including stochastic simulation algorithms, capture the random fluctuations inherent in biological systems with low molecular counts. This paradigm is essential for modeling microscopic and mesoscopic systems such as gene regulatory networks, where random molecular collisions and rare events can drive significant physiological outcomes—a critical consideration when modeling individual patient variations in drug response.

Fuzzy Stochastic Methods combine stochastic simulation with fuzzy logic to address both randomness and parameter uncertainty, which is particularly valuable for personalized medicine applications where precise kinetic parameters may be unknown. This approach recognizes that "reaction rates are typically vague and rather uncertain" in biological systems, and this vagueness affects stoichiometry and quantitative relationships in biochemical reactions [26].

Table 1: Modeling Paradigms in Systems Biology

| Modeling Approach | Mathematical Foundation | Ideal Application Scope | Personalized Medicine Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deterministic | Ordinary Differential Equations | Macroscopic systems with high component density | Population-level drug response trends |

| Stochastic | Stochastic Simulation Algorithm | Sparse systems with low molecular counts | Individual variations in drug metabolism |

| Fuzzy Stochastic | Fuzzy sets + Stochastic processes | Systems with parameter uncertainty | Patient-specific models with limited data |

| Cyclo(CRLLIF) | Cyclo(CRLLIF) Peptide|Research Use Only | Cyclo(CRLLIF) is a cyclic peptide for research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human, veterinary, or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Mpo-IN-7 | Mpo-IN-7, MF:C16H14N2O6, MW:330.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The choice between these paradigms depends on the system's spatial scale and component density. As [26] demonstrates through scale-density analysis, intracellular and cellular processes (microscopic and mesoscopic systems) with relatively low numbers of biological components are best modeled using stochastic methods, while intercellular and population-wide processes (macroscopic systems) with high component density are more suited to deterministic approaches.

Parameter Identification Using Multimodal Data

A critical methodological challenge in systems biology is parameter identification—determining the numerical values that define how model components interact. Traditional approaches rely heavily on quantitative data, but recent advances demonstrate how qualitative biological observations can be formalized as inequality constraints and combined with quantitative measurements for more robust parameter estimation [6].

This methodology converts qualitative data, such as whether a particular mutant strain is viable or inviable, into mathematical inequalities that constrain model outputs. For example, a qualitative observation that "protein B concentration increases when pathway A is activated" can be formalized as Bactivated > Bbaseline. These constraints are combined with quantitative measurements through an objective function that accounts for both datasets:

ftot(x) = fquant(x) + fqual(x)

where fquant(x) is a standard sum of squares quantifying the fit to quantitative data, and fqual(x) imposes penalties for violations of qualitative constraints [6]. This approach was successfully applied to estimate parameters for a yeast cell cycle model incorporating "both quantitative time courses (561 data points) and qualitative phenotypes of 119 mutant yeast strains (1647 inequalities) to perform automated identification of 153 model parameters" [6], demonstrating its power for complex biological systems.

Table 2: Data Types in Systems Biology Model Development

| Data Type | Examples | Formalization in Models | Parameter Identification Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Time Courses | Concentration measurements, metabolite levels | Numerical data points | Direct parameter estimation through curve fitting |

| Qualitative Phenotypes | Viability/inviability, oscillatory/non-oscillatory | Inequality constraints | Reduced parameter uncertainty |

| Steady-State Dose Response | EC50 values, activation thresholds | Numerical constants | Definition of system sensitivities |

| Network Topology | Protein-protein interactions, pathway maps | Model structure | Constraint of possible parameter spaces |

Model Similarity and Comparison Frameworks

As the number of biological models grows, comparing and integrating models becomes increasingly important. Research has identified six key aspects relevant for assessing model similarity: (1) underlying encoding, (2) references to biological entities, (3) quantitative behavior, (4) qualitative behavior, (5) mathematical equations and parameters, and (6) network structure [25]. Flexible, problem-specific combinations of these aspects can mimic researchers' intuition about model similarity and support complex model searches in databases—a crucial capability for personalized medicine where multiple models may need integration to capture patient-specific biology.

Formally, similarity between two models M1 and M2 with respect to aspect α is defined as:

simα(M1, M2) = σα(Πα(M1), Πα(M2))

where Πα is the projection of a model onto aspect α and σα is a similarity measure for that aspect [25]. This framework enables systematic comparison of models developed by different research groups or for different aspects of the same biological system, facilitating model integration and reuse in personalized medicine applications.

Technical Implementation: From Theory to Practice

Experimental Workflow for Integrative Studies

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow integrating computational and experimental approaches in systems biology:

This iterative process begins with a biological question, develops computational models to formalize hypotheses, designs experiments to test predictions, integrates resulting data to refine models, and ultimately generates insights applicable to personalized therapeutic strategies. The cycle continues until models achieve sufficient predictive power for clinical applications.

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of systems biology approaches requires specific research reagents and computational tools. The following table details essential resources mentioned in recent literature:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) | Yeast9, Tissue-specific GEMs | Predict flux of metabolites in metabolic networks | Analysis of metabolism across tissues and microbial species [27] [28] |

| Model Repositories & Standards | BioModels Database, SBML, CellML | Enable model sharing, reproducibility, and software interoperability | Encoding and exchange of biological models [25] |

| Annotation Databases | BRENDA, ChEBI | Provide semantic annotations linking model components to biological entities | Standardized representation of model components [25] [28] |

| Optimization Algorithms | Differential evolution, scatter search | Solve parameter identification problems with multiple constraints | Estimation of model parameters from experimental data [6] |

| Multi-tissue Physiological Models | Mixed Meal Model (MMM) | Describe interplay between physiological systems | Integration of tissue-specific GEMs for whole-body predictions [27] [28] |

Protocol: Parameter Identification with Mixed Data Types

Based on the methodology described in [6], the following protocol provides a detailed procedure for identifying model parameters using both qualitative and quantitative data:

Step 1: Model Structure Definition

- Formalize the biological network using appropriate mathematical representations (ODEs, Petri nets, etc.)

- Identify unknown parameters requiring estimation

- Define model outputs corresponding to measurable quantities

Step 2: Data Collection and Formalization

- Quantitative data: Collect numerical measurements (e.g., time-course data, dose-response curves)

- Qualitative data: Gather categorical observations (e.g., viability, relative changes, oscillatory behavior)

- Convert qualitative data into inequality constraints: gi(x) < 0

Step 3: Objective Function Formulation

- Construct quantitative objective term: fquant(x) = Σj (yj,model(x) - yj,data)²

- Construct qualitative objective term: fqual(x) = Σi Ci · max(0, gi(x))

- Combine into total objective function: ftot(x) = fquant(x) + fqual(x)

Step 4: Parameter Estimation

- Select appropriate optimization algorithm (differential evolution recommended for nonlinear problems)

- Set problem-specific constants Ci to balance contributions of different constraint types

- Perform constrained optimization to minimize ftot(x)

Step 5: Uncertainty Quantification

- Apply profile likelihood approach to assess parameter identifiability

- Evaluate confidence intervals for parameter estimates

- Validate identified parameters with held-out experimental data

This protocol was successfully applied to estimate parameters for a Raf inhibition model and a yeast cell cycle model, demonstrating its general applicability to biological systems of different complexities [6].

Applications in Personalized Medicine

Virtual Tumors for Predictive Oncology

The creation of "virtual tumours" represents a powerful application of systems biology in personalized cancer treatment. As described by Jasmin Fisher in the 2025 SysMod meeting, these computational models simulate intra- and inter-cellular signaling in various cancer types, including triple-negative breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, and glioblastoma [28]. These predictive, mechanistically interpretable models enable researchers to "understand and anticipate emergent resistance mechanisms and to design patient-specific treatment strategies to improve outcomes for patients with hard-to-treat cancers" [28].

The virtual tumor approach exemplifies how systems biology bridges computational modeling and molecular biology by creating digital representations of patient-specific tumors that can be manipulated computationally to test therapeutic strategies before clinical implementation. This methodology aligns with the broader vision of Integrative and Regenerative Pharmacology, which aims to develop "transformative curative therapeutics" that restore physiological structure and function rather than merely managing symptoms [8].

Metabolic Modeling for Personalized Therapeutic Design

Systems biology approaches have demonstrated particular success in metabolic disorders and cancer metabolism through the development of personalized metabolic models. One study presented at the 2025 SysMod meeting embedded "GEMs of the liver, skeletal muscle, and adipocyte into the Mixed Meal Model (MMM), a physiology-based computational model describing the interplay between glucose, insulin, triglycerides and non-esterified fatty acids (NEFAs)" [28]. This multi-scale approach enabled researchers to simulate "personalised hybrid multi-tissue Meal Models" that revealed "changes in tissue-specific flux associated with insulin resistance and liver fat accumulation" [28], demonstrating the power of integrated modeling to identify personalized therapeutic targets.

In cancer research, another study employed "genome-scale metabolic models (GSMMs) integrated with single-cell RNA sequencing data from patient-derived xenograft models to investigate the metabolic basis of breast cancer organotropism" [28]. This approach identified "distinct metabolic adaptations in metastatic tissues" and used "flux-based comparisons of primary tumors predisposed to different metastatic destinations" to identify "metabolic signatures predictive of organotropism" [28]. The resulting models enabled simulation of gene manipulation strategies to identify potential metabolic targets for therapeutic intervention.

The following diagram illustrates how multi-scale modeling integrates different biological levels for personalized therapeutic design:

Integrative and Regenerative Pharmacology

The emerging field of Integrative and Regenerative Pharmacology (IRP) represents a comprehensive application of systems biology principles to therapeutic development. IRP "bridges pharmacology, systems biology and regenerative medicine, thereby merging the two earlier fields" and represents "the emerging science of restoring biological structure and function through multi-level, holistic interventions that integrate conventional drugs with target therapies intended to repair, renew, and regenerate rather than merely block or inhibit" [8].

This approach leverages systems biology methodologies to "define the MoA of therapeutic approaches (e.g., stem cell-derived therapies), accelerating the regulatory approval of advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs)" [8]. In this framework, "stem cells can be considered as tunable combinatorial drug manufacture and delivery systems, whose products (e.g., secretome) can be adjusted for different clinical applications" [8], demonstrating how systems biology provides the conceptual and computational tools needed to advance regenerative approaches.

The unifying nature of IRP is its primary strength, as it "envisions achieving therapeutic outcomes that are not possible with pharmacology or regenerative medicine alone" [8]. Furthermore, "IRP aspires to develop precise therapeutic interventions using genetic profiling and biomarkers of individuals" as part of personalized and precision medicine, employing "state-of-the-art methodologies (e.g., omics, gene editing) to assist in identifying the signaling pathways and biomolecules that are key in the development of novel regenerative therapeutics" [8].

Future Directions and Implementation Challenges

Addressing Translational Barriers

Despite its significant promise, the application of systems biology approaches in personalized medicine faces substantial implementation challenges. As noted in research on Integrative and Regenerative Pharmacology, these include "investigational obstacles, such as unrepresentative preclinical animal models," "manufacturing issues, such as scalability, automated production methods and technologies," "complex regulatory pathways with different regional requirements," ethical considerations, and economic factors such as "high manufacturing costs and reimbursement" challenges [8].

These translational barriers are particularly significant for clinical implementation, where "long-term follow-up clinical investigation is required to assess regenerative drugs and biologics beyond initial clinical trials" [8]. Addressing these challenges will require "interdisciplinary clinical trial designs that incorporate pharmacology, bioengineering, and medicine" and cooperation "between academia, industry, clinics, and regulatory authorities to establish standardized procedures, guarantee consistency in therapeutic outcomes, and eventually develop curative therapies" [8].

Technological Advancements and Emerging Methodologies

Future advances in systems biology applications for personalized medicine will likely be driven by several technological developments. Artificial intelligence (AI) represents a particularly promising tool, as "AI has the potential to transform regenerative pharmacology by enabling the development of more efficient and targeted therapeutics, predict DDSs effectiveness as well as anticipate cellular response" [8]. However, challenges remain in implementing AI, "namely, the standardization of experimental/clinical datasets and their conversion into accurate and reliable information amenable to further investigation" [8].

Advanced biomaterials also represent a promising direction, particularly "the development of 'smart' biomaterials that can deliver locally bioactive compounds in a temporally controlled manner" [8]. Specifically, "stimuli-responsive biomaterials, which can alter their mechanical characteristics, shape, or drug release profile in response to external or internal triggers, represent transformative therapeutic approaches" [8] that could be optimized using systems biology models.

Community-driven benchmarking initiatives represent another important direction for advancing systems biology applications. As described in the SysMod meeting, one such initiative aimed at "evaluating and comparing O-ABM for biomedical applications" has enlisted "developers from leading tools like BioDynaMo" [28] to establish standardized evaluation frameworks similar to successful efforts in other scientific domains such as CASP (Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction).

As systems biology continues to mature, its role in personalized medicine will expand, ultimately fulfilling the vision that "regeneration today must be computationally informed, biologically precise, and translationally agile" [8]. Through continued development of integrative approaches that bridge computational modeling and molecular biology, systems biology will increasingly enable the development of truly personalized therapeutic strategies that account for the unique biological complexity of each individual patient.

From Data to Therapy: Methodological Approaches and Clinical Applications

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) with systems biology is fundamentally transforming biomarker discovery, enabling a shift from reactive disease treatment to proactive, personalized medicine. By decoding complex, multi-scale biological networks, these technologies are accelerating the identification of diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive biomarkers. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of how AI/ML methodologies are being deployed within a systems biology framework to create predictive models of disease and treatment response. It details cutting-edge computational protocols, presents structured comparative data, and outlines the essential toolkit for researchers and drug development professionals, thereby charting the course toward more precise and effective therapeutic interventions.

Systems biology represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research, moving from a reductionist study of individual molecular components to a holistic analysis of complex interactions within biological systems [29] [30]. This approach views biology as an information science, where biological networks capture, transmit, and integrate signals to govern cellular behavior and physiological responses [29]. When applied to personalized medicine, systems biology aims to understand how disease-perturbed networks differ from healthy states, thereby enabling the identification of molecular fingerprints that can guide clinical decisions [29].

The core premise is that diseases are rarely caused by a single gene or protein but rather by perturbations in complex molecular networks [29]. AI and ML serve as the critical computational engine that powers this framework. They provide the capacity to analyze vast, multi-dimensional datasets—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and clinical data—to identify patterns and relationships that are imperceptible to traditional statistical methods [31] [32]. This synergy is crucial for biomarker discovery, as it allows researchers to move beyond single, often inadequate, biomarkers to multi-parameter biomarker panels that offer a more comprehensive view of an individual's health status and likely response to therapy [29] [31].

Biomarker Types and Their Clinical Application in Precision Oncology

Biomarkers are objectively measurable indicators of biological processes, pathological states, or responses to therapeutic intervention [32]. In precision medicine, they are foundational for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection. The table below categorizes key biomarker types and their roles, with a focus on oncology applications.

Table 1: Classification and Clinical Applications of Biomarkers in Precision Oncology

| Biomarker Type | Clinical Role | Example | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic | Identifies the presence or subtype of a disease | MSI (Microsatellite Instability) status in colorectal cancer [33] | Differentiates cancer subtypes for initial diagnosis. |

| Prognostic | Provides information on the likely course of the disease | Deep learning features from histopathology images in colorectal cancer [34] | Forecasts disease aggressiveness and patient outcome independent of therapy. |

| Predictive | Indicates the likelihood of response to a specific therapeutic | MARK3, RBCK1, and HSF1 for regorafenib response in mCRC [33] | Guides therapy selection by predicting efficacy of a targeted drug. |

| Pharmacodynamic | Measures the biological response to a therapeutic intervention | Dynamic changes in transcriptomic profiles during viral infection or T2D onset [13] | Confirms drug engagement and assesses biological effect during treatment. |

The challenge in oncology, particularly for complex diseases like metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC), is that few validated predictive biomarkers exist. For instance, despite the efficacy of regorafenib in some elderly mCRC patients, no biomarkers are currently available to predict which individuals will benefit, highlighting a critical unmet need that AI-driven systems biology approaches aim to address [33].

AI and Machine Learning Methodologies in Biomarker Discovery

AI and ML algorithms are uniquely suited to handle the high dimensionality, noise, and complexity of biological data. Their application spans the entire biomarker discovery pipeline, from data integration and feature selection to model building and validation.

Key Machine Learning Approaches

ML methodologies can be broadly categorized into supervised and unsupervised learning, each with distinct applications in biomarker research.

Table 2: Machine Learning Methodologies for Different Omics Data Types in Biomarker Discovery

| Omics Data Type | ML Techniques | Typical Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomics | Feature selection (e.g., LASSO); SVM; Random Forest [31] | Identifying gene expression signatures associated with disease subtypes or drug response. | High-dimensional data requires robust feature selection to avoid overfitting. |

| Proteomics | Random Forest; XGBoost [35] | Classifying predictive biomarker potential based on network features and protein properties. | Handles complex, non-linear relationships between protein features and biomarker status. |

| Multi-Omics Integration | Deep Learning (CNNs, RNNs, Transformers) [31] [32] | End-to-end learning from integrated genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data for patient stratification. | Requires large sample sizes and significant computational resources; "black box" interpretability challenges. |

| Histopathology Images | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [34] [31] | Extracting prognostic and predictive features directly from standard histology slides. | Can outperform human observation and established molecular markers [34]. |

The Role of Deep Learning and Large Language Models

Deep learning (DL) architectures, particularly CNNs and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), have proven highly effective for complex data types like imaging and sequential omics data [31]. Transformers and Large Language Models (LLMs) are increasingly being adapted to analyze biological sequences and integrate multi-modal data, enabling precise disease risk stratification and diagnostic determinations by identifying complex non-linear associations [32].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The application of AI/ML in biomarker discovery follows rigorous computational and experimental protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for two key approaches: digital patient modeling and machine learning-based biomarker classification.

Protocol 1: In Silico Clinical Trial Using Digital Patient Modeling

This protocol, derived from a study on regorafenib in mCRC, outlines the steps for simulating drug response in a virtual patient population [33].

Objective: To simulate individualized mechanisms of action and identify predictive biomarkers of regorafenib response in elderly mCRC patients.

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition and Curation:

- Patient Transcriptomics: Obtain gene expression data from mCRC biopsies of untreated elderly patients (e.g., from GEO database, TCGA). Include a set of healthy control samples from the same tissue type [33].

- Drug Target Information: Compile a list of known pharmacological protein targets of the drug (e.g., 18 targets for regorafenib from DrugBank) [33].

- Disease Molecular Definition: Manually curate a set of proteins with documented roles in the disease (mCRC), annotated as activation-associated (+1) or inhibition-associated (-1), to form the core knowledge set for modeling [33].

Generation of Individual Differential Expression (IDE) Signatures:

- Normalization: Apply cross-platform normalization (e.g., CuBlock) to all gene expression samples at the probe level [33].

- Protein-level Conversion: Convert probe-level expression to protein-level expression by averaging all probes mapping to the same protein [33].

- Differential Expression Calling: For each patient sample, compare protein expression levels against the distribution in healthy controls. Proteins with expression above the 95th percentile or below the 5th percentile of the healthy distribution are considered upregulated (+1) or downregulated (-1), respectively [33].

- IDE Refinement: Filter the IDE signatures by retaining only proteins that are both differentially expressed at the population level (using Welch’s t-test/DESeq2 with FDR < 0.05) and lie within three interaction links of the core mCRC protein knowledge set in a protein interaction network [33].

Therapeutic Performance Mapping System (TPMS) Modeling:

- Network Construction: Build mathematical models based on the Human Protein Network (HPN), integrating physical interactions, signaling pathways, and gene regulation from curated databases (KEGG, REACTOME, BIOGRID, etc.) [33].

- Signal Propagation: Simulate the drug's effect by introducing the target inhibition stimulus into the HPN. The signal propagates through the network over iterative steps. In each step, nodes integrate weighted inputs from upstream neighbors, transforming the sum via a hyperbolic tangent function to normalize and limit signal magnitude [33].

- Individualized Simulation: Execute the TPMS model for each patient's specific IDE signature to simulate their unique response to the drug stimulus [33].

Biomarker Identification and Validation:

- Analysis: Correlate the simulated network states or protein activity levels with the predicted drug response outcomes to identify proteins associated with both the drug's mechanism of action and treatment efficacy [33].

- Validation: Validate candidate biomarkers (e.g., MARK3, RBCK1, HSF1) in an independent cohort of mCRC patients and cross-reference with previously reported predictive miRNAs [33].

The following diagram illustrates the digital patient modeling workflow:

Protocol 2: Machine Learning Classification of Predictive Biomarkers

This protocol details the methodology for the MarkerPredict tool, which uses ML to classify the potential of proteins as predictive biomarkers [35].

Objective: To develop a hypothesis-generating framework (MarkerPredict) that classifies target-interacting proteins as potential predictive biomarkers for targeted cancer therapeutics.

Methodology:

- Data Compilation and Network Analysis:

- Signaling Networks: Utilize three signed signaling networks: Human Cancer Signaling Network (CSN), SIGNOR, and ReactomeFI [35].

- Motif Identification: Identify all three-nodal network motifs (triangles) using the FANMOD tool. Focus on triangles containing both a known oncotherapeutic target and an interacting protein (neighbor) [35].

- Protein Disorder Annotation: Annotate all proteins using intrinsic disorder databases and prediction methods (DisProt, IUPred, AlphaFold) [35].

Training Set Construction:

- Positive Controls: Annotate neighbor-target pairs where the neighbor is an established predictive biomarker for the drug targeting its pair, using the CIViCmine text-mining database. Manually review for accuracy (Class 1) [35].

- Negative Controls: Construct a set of neighbor-target pairs where the neighbor is not listed as a predictive biomarker in CIViCmine, supplemented by random pairs and proteins absent from CIViCmine [35].

Feature Engineering and Model Training:

- Feature Extraction: For each neighbor-target pair, extract features including network topological properties (e.g., motif type, centrality measures) and protein annotations (e.g., intrinsic disorder scores) [35].

- Model Selection and Training: Train multiple binary classification models, including Random Forest and XGBoost, on network-specific and combined data, and on individual and combined IDP databases. Optimize hyperparameters using competitive random halving [35].

- Validation: Evaluate model performance using Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV), k-fold cross-validation, and a 70:30 train-test split, assessing AUC, accuracy, and F1-score [35].

Classification and Scoring:

- Biomarker Probability Score (BPS): Apply the trained models to classify all potential neighbor-target pairs in the networks. Define a Biomarker Probability Score (BPS) as a normalized summative rank across all models to prioritize candidates for experimental validation [35].

The following diagram illustrates the MarkerPredict classification workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, tools, and data resources essential for conducting AI-driven biomarker discovery research within a systems biology framework.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AI-Driven Biomarker Discovery

| Resource Category | Item | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | GEO Database [33] | Public repository for transcriptomic data, used to obtain patient and control samples for analysis. |

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [33] | Source of multi-omics data (e.g., RNA-seq) for model training and validation in oncology. | |

| DrugBank [33] | Curated database of drug and drug target information, essential for defining the molecular stimulus in drug response modeling. | |