From In Silico to In Vitro: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Computational Predictions with RNAi and RT-PCR

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals to bridge computational predictions and experimental biology.

From In Silico to In Vitro: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Computational Predictions with RNAi and RT-PCR

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for researchers and drug development professionals to bridge computational predictions and experimental biology. It covers the foundational principles of RNA interference (RNAi) and Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR), detailing robust methodologies for designing and executing validation experiments. The guide addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies to enhance reliability and reproducibility. Furthermore, it presents rigorous validation and comparative analysis techniques to confirm gene silencing efficacy and specificity, ensuring that computational forecasts are accurately substantiated in the lab for applications in functional genomics and therapeutic development.

The Computational and Molecular Biology Foundation of RNAi Validation

The advent of RNA interference (RNAi) has revolutionized molecular biology and therapeutic development, offering a precise mechanism for gene silencing. Central to this mechanism are small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) pathway. This guide objectively compares key methodologies in siRNA design and experimental validation, framing the discussion within a broader thesis on corroborating computational predictions with empirical RNAi and RT-PCR research. For researchers and drug development professionals, bridging in-silico models with robust lab-based assays is critical for advancing reliable therapeutics [1]. The following sections provide comparative data, detailed protocols, and essential toolkits underpinning this integrative approach.

Comparative Analysis of siRNA Design and Validation Methodologies

The efficacy of an RNAi-based therapeutic or research tool hinges on the precision of siRNA design and the rigor of its validation. Below is a comparative summary of approaches highlighted in recent research.

Table 1: Comparison of siRNA Design & Screening Platforms

| Aspect | Computational siRNA Design (GPR10 Case Study) [1] | Allele-Specific RT-PCR Assay Design (SARS-CoV-2 Case Study) [2] [3] | Mechanistic PK/PD Modeling (siRNA Therapeutics) [4] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Design high-affinity siRNA for specific gene (GPR10) silencing. | Design primer-probe sets for variant-specific viral RNA detection. | Model intracellular siRNA disposition to predict gene knockdown. |

| Starting Input | Target mRNA sequence (e.g., GPR10, NM_004248.3). | Genomic databases (GISAID, NCBI) of viral variants. | In vitro data on siRNA delivery, RISC loading, and mRNA kinetics. |

| Key Screening Metrics | Thermodynamic stability, off-target filtration, AGO2 docking affinity, predicted efficacy (>93.5%). | Mutation profile analysis (e.g., Spike protein RBD mutations). | Cell proliferation rate, mRNA turnover, RISC occupancy, target engagement. |

| Output | Shortlisted high-confidence siRNA candidates (e.g., siRNA8, siRNA12). | Allele-specific primer-probe sets for 9 mutations across Delta/Omicron. | Quantitative relationship for maximal mRNA knockdown. |

| Validation Anchor | Molecular Dynamics simulations for complex stability. | Analytical sensitivity (1x10² copies/mL) and 100% specificity testing [2] [3]. | Correlation of model predictions with in vitro knockdown data in MCF7/BT474 cells. |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of RNAi/Detection Assays

| Assay/Technology | Target | Sensitivity / Efficacy | Specificity / Key Advantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novel Multiplex RT-PCR | SARS-CoV-2 Delta/Omicron variants | ~100 copies/mL | 100% analytical specificity; detects 7 Omicron & 2 Delta mutations [2]. | [2] [3] |

| Computationally Designed siRNA | Human GPR10 mRNA | >93.5% predicted silencing efficacy | High binding affinity to AGO2; minimized off-target via layered in-silico refinement. | [1] |

| RNAiMAX-delivered siRNA | Various extrahepatic targets in vitro | Governed by mRNA half-life & cell proliferation | Model identifies determinants of knockdown extent & duration beyond liver. | [4] |

| Endogenous Plant ta-siRNA Pathway | Developmental patterning (e.g., ARF genes) | Amplified via transitivity & RDR6 | Systemic spreading and cell-to-cell movement as a regulatory advantage [5] [6]. | [5] [6] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol details the computational pipeline for designing high-potency siRNAs, using the targeting of GPR10 for uterine fibroids as a case study.

- Target Sequence Retrieval: Obtain the complete coding DNA sequence (CDS) of the target mRNA (e.g., GPR10, NM_004248.3 from NCBI Nucleotide database).

- Initial Candidate Generation: Generate a library of all possible siRNA sequences (typically 21-23 nt) targeting the CDS. For GPR10, this resulted in 275 initial candidates.

- Layered In-Silico Refinement:

- Thermodynamic Assessment: Filter candidates based on optimal GC content and binding energy.

- Secondary Structure Modeling: Evaluate target mRNA accessibility and siRNA self-structure.

- Off-Target Filtration: Use sequence alignment tools to exclude candidates with significant homology to other transcripts in the relevant genome.

- Protein Interaction Docking: Dock the shortlisted siRNA duplexes into the crystal structure of the Argonaute 2 (AGO2) protein, the catalytic core of RISC. Assess binding affinity and conformational fit.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation: Subject the top siRNA-AGO2 complexes to MD simulations (e.g., using CHARMM-GUI/CHARMM36m force field) to confirm structural stability and sustained interaction over time.

- Output: Select lead candidates (e.g., siRNA8, siRNA12) based on robust docking scores, high predicted silencing efficacy, and stable MD trajectories for subsequent in vitro testing.

This protocol outlines the creation of a molecular diagnostic assay, exemplified by SARS-CoV-2 variant detection, which serves as a validation tool for sequence-based predictions.

- In-Silico Sequence Analysis and Primer Design:

- Perform comparative analysis of viral genomic sequences from databases (GISAID, NCBI GenBank).

- Identify signature mutations for each variant (e.g., Ins214EPE, L452R for Omicron; D63G for Delta).

- Design allele-specific primers and TaqMan probes targeting these mutation sites within the Spike protein's RBD.

- Assay Optimization:

- Test primer-probe sets using synthetic RNA templates or plasmids containing target sequences.

- Optimize multiplex RT-PCR conditions (annealing temperature, primer concentration) to ensure specific amplification.

- Analytical Validation:

- Sensitivity: Perform limit of detection (LOD) experiments using serial dilutions of quantified viral RNA. The described assay achieved an LOD of ~1 x 10² copies/mL [2].

- Specificity: Test the assay against a panel of negative clinical samples and RNA from other respiratory pathogens to confirm 100% analytical specificity.

- Clinical Evaluation: Validate using a panel of leftover, characterized clinical samples (e.g., 160 archived VTM samples), comparing results to gold-standard Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS).

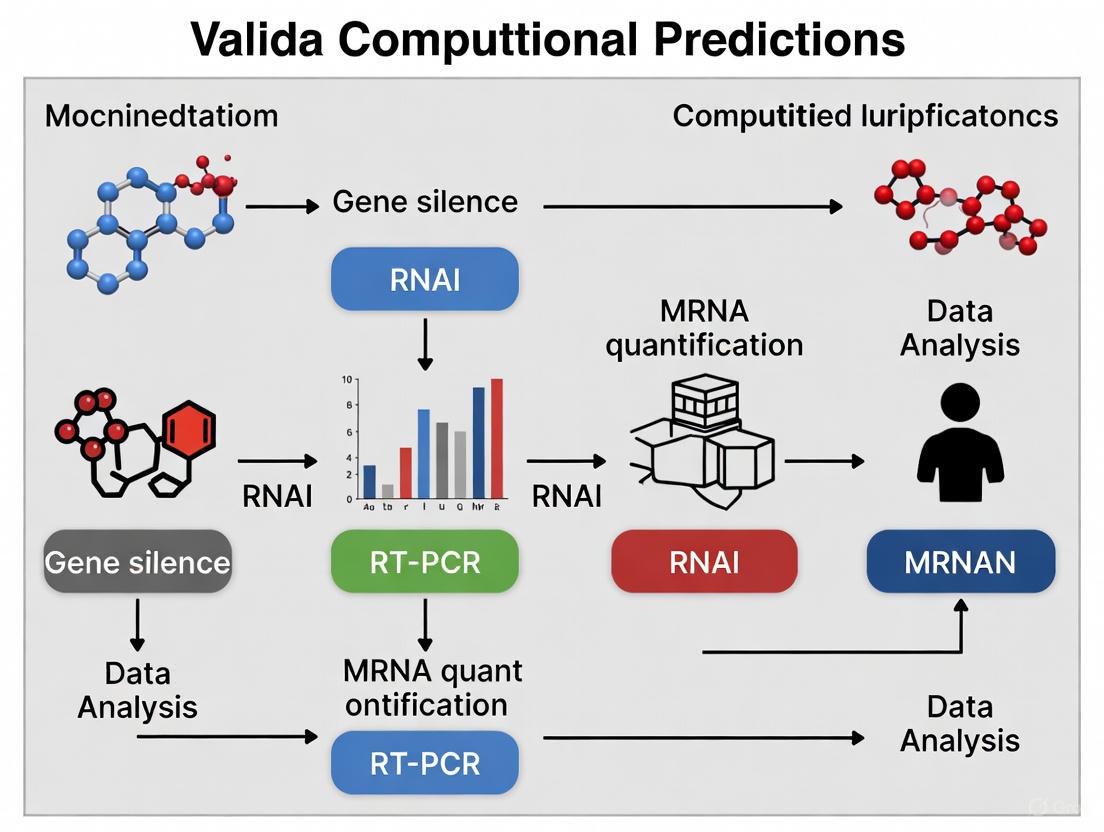

Visualization of Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: RISC Pathway for siRNA-Mediated Silencing

Diagram 2: siRNA Design and Experimental Validation Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Featured Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Primary Function / Role | Context of Use |

|---|---|---|

| Allele-Specific Primer-Probe Sets | Enable multiplex detection and differentiation of specific genetic mutations (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 variants) in RT-PCR assays. | Molecular diagnostics and validation of target sequences [2] [3]. |

| Chemically Modified siRNA Duplexes | Provide nuclease resistance, enhance stability, and improve RISC loading efficiency for therapeutic in vitro and in vivo applications. | siRNA therapeutic development and mechanistic studies [4] [1]. |

| RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent | A lipid-based delivery system for efficient siRNA transfection into a wide range of mammalian cell lines in vitro. | In vitro validation of siRNA-mediated gene knockdown [4]. |

| Recombinant Argonaute 2 (AGO2) Protein | Serves as the structural template for molecular docking studies to predict siRNA binding affinity and RISC compatibility. | Computational siRNA design and in-silico validation [1]. |

| Reference Viral RNA & Clinical Samples | Provide quantified, characterized templates for analytical validation (sensitivity/specificity) of molecular diagnostic assays. | RT-PCR assay development and clinical performance evaluation [2] [3]. |

| RDR6, DCL4, AGO1 (Plant Systems) | Key enzymes in the endogenous siRNA biogenesis and amplification pathway (transitivity) in plants. | Study of systemic RNAi and secondary siRNA generation [5] [6]. |

Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) and quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) are foundational molecular techniques for analyzing gene expression. RT-PCR combines reverse transcription of RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) with amplification of specific DNA targets, enabling the detection of RNA expression patterns [8]. Its quantitative counterpart, qRT-PCR (also known as real-time quantitative PCR), allows for precise quantification of gene expression levels by measuring PCR product accumulation in real-time using fluorescent reporters [9]. These methodologies have become indispensable tools in biological research, medical diagnostics, and drug development, particularly for validating gene function in loss-of-function studies such as those involving RNA interference (RNAi) [10].

The fundamental process begins with RNA extraction from biological samples, followed by reverse transcription using viral reverse transcriptases to produce cDNA [8]. This cDNA then serves as the template for either conventional PCR amplification or quantitative real-time PCR analysis. In qRT-PCR, the fluorescence signal increases proportionally with the accumulated PCR product, allowing researchers to determine the initial quantity of the target transcript [9]. The point at which the fluorescence crosses a predetermined threshold is called the quantification cycle (Cq), with lower Cq values indicating higher starting amounts of the target nucleic acid [9].

Technical Comparison of RT-PCR and qRT-PCR

Fundamental Principles and Detection Methods

RT-PCR and qRT-PCR differ significantly in their detection capabilities and applications. Conventional RT-PCR is primarily qualitative, providing endpoint detection of amplified DNA typically through gel electrophoresis, while qRT-PCR offers quantitative data by monitoring DNA amplification in real-time [8] [9]. This fundamental difference dictates their respective applications in research and diagnostics.

The quantification capability of qRT-PCR stems from its use of fluorescent reporting systems. Two primary detection chemistries are employed: DNA-binding dyes and target-specific probes [9]. DNA-binding dyes like SYBR Green I fluoresce when bound to double-stranded DNA, providing a simple and cost-effective detection method. Conversely, probe-based systems such as hydrolysis probes (TaqMan) provide enhanced specificity through oligonucleotides that bind specifically to target sequences between the PCR primers [9]. This specificity is particularly valuable in diagnostic applications and when distinguishing between closely related gene sequences.

Performance Characteristics and Applications

qRT-PCR demonstrates superior performance for gene expression studies

qRT-PCR demonstrates superior performance for gene expression studies

| Performance Characteristic | RT-PCR | qRT-PCR |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Capability | Semi-quantitative at best | Fully quantitative |

| Detection Method | End-point (gel electrophoresis) | Real-time (fluorescence) |

| Dynamic Range | Limited | 10-log range (single to ~10¹¹ copies) |

| Sensitivity | Moderate | High (detection of single copies possible) |

| Specificity | Moderate (primers only) | High (primers + probe options) |

| Throughput | Lower | Higher (96- or 384-well formats) |

| Risk of Contamination | Higher (post-PCR handling required) | Lower (closed-tube system) |

| Primary Applications | Target detection, cloning | Gene expression analysis, pathogen quantification, SNP genotyping |

| Data Output | Presence/absence | Quantification cycle (Cq), amplification efficiency, relative quantification |

The quantitative nature of qRT-PCR makes it particularly suitable for gene expression analysis, where it is used to compare transcript levels between different experimental conditions, tissues, or treatment groups [11] [9]. Its extensive dynamic range allows detection from single copies to approximately 10¹¹ copies in a single run, far exceeding the capabilities of conventional RT-PCR [9]. Furthermore, the closed-tube nature of qRT-PCR significantly reduces contamination risks compared to conventional RT-PCR, which requires post-amplification processing [9].

Advanced Quantitative Methodologies

Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

RT-qPCR represents the most widely used approach for gene expression quantification and can be performed through one-step or two-step protocols [12]. In one-step RT-qPCR, reverse transcription and PCR amplification occur in a single tube using a unified buffer system, minimizing pipetting steps and potential contamination [12]. This approach is particularly suitable for high-throughput applications. Conversely, two-step RT-qPCR separates reverse transcription and amplification into discrete reactions, allowing for optimized conditions for each step and generating stable cDNA pools that can be used for multiple targets [12].

The reverse transcription step can be primed using different strategies, each with distinct advantages. Oligo(dT) primers target the poly(A) tails of mRNA, generating cDNA representative of coding regions [12]. Random primers anneal throughout the RNA transcript, useful for RNAs with secondary structure or without poly(A) tails. Gene-specific primers provide the highest specificity for particular targets [12]. Many protocols employ a combination of random and oligo(dT) primers to maximize coverage while maintaining representation of mRNA sequences.

Emerging Technologies: RT-droplet digital PCR

While RT-qPCR remains the gold standard for quantitative gene expression analysis, newer technologies like reverse transcription droplet digital PCR (RT-ddPCR) offer alternative capabilities, particularly for low-abundance targets [13]. Unlike qPCR's relative quantification, ddPCR provides absolute quantification of target molecules by partitioning samples into thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets and counting positive reactions [13].

Recent research demonstrates that RT-ddPCR shows equivalent performance to RT-qPCR in mid- and high-viral-load ranges but exhibits superior sensitivity for low-abundance targets [13]. This enhanced detection capability is particularly valuable for identifying persistent infections at low levels, as demonstrated in studies of SARS-CoV-2 where RT-ddPCR detected positive samples in exposed individuals that tested negative by RT-qPCR [13]. Additionally, ddPCR's absolute quantification eliminates the need for standard curves and shows greater tolerance to PCR inhibitors, potentially reducing interlaboratory variability [13].

Experimental Design and Protocols

Critical Experimental Considerations

Table 2: Essential research reagents for RT-PCR and qRT-PCR experiments

Table 2: Essential research reagents for RT-PCR and qRT-PCR experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptase Enzymes | Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (MMLV) RT, Avian Myeloblastosis Virus (AMV) RT | Synthesizes complementary DNA (cDNA) from RNA templates |

| DNA Polymerases | Taq polymerase, hot-start variants | Amplifies target DNA sequences during PCR |

| Fluorescent Detection Systems | SYBR Green, hydrolysis probes (TaqMan), molecular beacons | Enable real-time monitoring of amplification in qRT-PCR |

| Primers | Sequence-specific, oligo(dT), random hexamers | Define target regions and initiate cDNA synthesis or DNA amplification |

| RNA Extraction Reagents | TRIzol, column-based kits | Isolate and purify intact RNA from biological samples |

| Reference Genes | GAPDH, β-actin, ribosomal proteins, elongation factors | Normalize for technical variation in gene expression studies |

| Sample Collection & Storage | RNase-free swabs, RNA stabilization solutions | Maintain RNA integrity from collection to processing |

Proper experimental design is crucial for generating reliable RT-PCR and qRT-PCR data. The workflow encompasses multiple stages where variability can be introduced: sample collection, storage, RNA extraction, reverse transcription, and amplification [14]. Sample collection methods must preserve RNA integrity, with proper handling and storage conditions to prevent degradation [14]. RNA extraction should consistently yield high-quality, uncontaminated RNA, as the presence of inhibitors like heparin, hemoglobin, or ionic detergents can significantly impact PCR efficiency [8].

Primer design requires particular attention in qRT-PCR applications. Ideally, primers should span exon-exon junctions, with one primer potentially crossing an exon-intron boundary, to minimize amplification from contaminating genomic DNA [12]. When this design is not possible, treatment with DNase is recommended to remove genomic DNA contamination [12]. Including appropriate controls is also essential, with "no reverse transcriptase" controls (-RT) necessary to identify genomic DNA contamination that could lead to false positive results [12].

Reference Gene Validation

Accurate quantification in qRT-PCR depends on proper normalization using stable reference genes (housekeeping genes) to control for variations in RNA input, reverse transcription efficiency, and overall experimental variability [11] [15]. Traditional reference genes like GAPDH, β-actin, and 18S RNA were once widely used, but numerous studies have demonstrated that their expression can vary significantly under different experimental conditions [11].

Comprehensive studies now recommend systematic validation of reference genes for each experimental system. Statistical algorithms such as geNorm, NormFinder, and BestKeeper can evaluate expression stability and identify optimal reference genes for specific conditions [11] [15]. Research across various organisms, including plants, insects, and mammals, has demonstrated that the most stable reference genes differ depending on tissue type, developmental stage, and experimental treatment [11] [15]. Using multiple validated reference genes is now considered best practice for obtaining reliable gene expression data.

Applications in Validating Computational Predictions with RNAi

The integration of RT-PCR and qRT-PCR with RNA interference (RNAi) has created a powerful experimental paradigm for validating computational predictions of gene function. RNAi enables targeted silencing of gene expression, while qRT-PCR provides a quantitative method to verify knockdown efficiency and assess downstream transcriptional effects [10]. This combined approach is particularly valuable for functional genomics, where computational methods increasingly predict essential genes and potential therapeutic targets.

Recent applications demonstrate this methodology in action. Machine learning approaches like the CLassifier of Essentiality AcRoss EukaRyote (CLEARER) algorithm have been developed to predict essential genes across eukaryotic species [16]. These computational predictions require experimental validation, which is efficiently provided by RNAi-mediated gene knockdown followed by qRT-PCR analysis. For example, in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae, computational predictions identified potential insecticidal targets that were subsequently validated using RNAi and qRT-PCR, revealing genes critical for mosquito survival and Plasmodium development [16].

The experimental workflow typically begins with computational identification of candidate genes through essentiality prediction algorithms or chokepoint analysis of metabolic networks [16]. RNAi is then employed to silence these candidates, followed by qRT-PCR to quantify knockdown efficiency and assess phenotypic consequences through expression analysis of related genes [16] [10]. This integrated approach accelerates the identification of promising therapeutic targets and essential genes for further development.

Performance Metrics and Diagnostic Applications

Analytical Performance Measures

The performance of RT-qPCR assays is characterized by specific metrics that determine their reliability and applicability. The limit of detection (LoD) defines the lowest concentration of target that can be reliably detected, while analytical specificity refers to the assay's ability to exclusively detect the intended target without cross-reacting with similar sequences [14]. These parameters are typically established during assay development under controlled laboratory conditions.

PCR efficiency is another critical parameter, representing the rate of product amplification per cycle. Ideal PCR efficiency is 100%, corresponding to a doubling of product each cycle [14]. Efficiency can be calculated from standard curves generated using serial dilutions of known standards, with the slope of the curve determining the efficiency value [14]. Maintaining high and consistent PCR efficiency is essential for both accurate quantification and reliable detection of low-abundance targets.

Comparative Performance in Diagnostic Applications

The diagnostic performance of RT-qPCR has been extensively evaluated, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Comparative studies have assessed different RT-qPCR protocols, with the CDC (USA) protocol demonstrating superior accuracy in detecting SARS-CoV-2 compared to other molecular tests like RT-LAMP and serological assays [17]. This highlights the importance of protocol optimization even within the same technological platform.

Sample type and collection methods significantly impact test performance. Oro-nasopharyngeal swabs have proven more effective than saliva for SARS-CoV-2 detection, and samples from symptomatic individuals with multiple symptoms typically show higher viral loads [17]. Nevertheless, proper technique throughout the testing process—from sample collection to RNA extraction and amplification—remains essential for reliable results [14].

RT-PCR and qRT-PCR represent complementary technologies that have revolutionized gene expression analysis. While RT-PCR provides a robust method for target detection, qRT-PCR enables precise quantification with extensive dynamic range and high sensitivity. The integration of these methodologies with RNAi and computational predictions creates a powerful framework for functional genomics and target validation. As molecular technologies continue to evolve, emerging methods like RT-ddPCR offer enhanced capabilities for specific applications, particularly low-abundance targets. Nevertheless, proper experimental design, validation of reference genes, and attention to technical details remain fundamental to generating reliable data regardless of the specific platform employed.

The advent of RNA interference (RNAi) as a therapeutic modality has revolutionized targeted gene silencing, with small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) at its forefront. The efficacy and specificity of an siRNA therapeutic are not serendipitous but are engineered through meticulous computational design. This guide objectively compares the algorithms, rules, and tools that underpin modern siRNA design, framing the discussion within the critical thesis that in silico predictions must be rigorously validated through experimental RNAi and RT-PCR research to transition from digital models to viable therapeutics [18] [19].

Core Design Rules and Predictive Algorithms

The foundation of computational siRNA design rests on empirically derived rules that correlate sequence features with silencing efficiency and minimize off-target effects. Key rule sets include those established by Ui-Tei, Amarzguioui, and Reynolds [18] [20] [21]. These rules govern parameters such as nucleotide composition at specific positions, overall GC content, and thermodynamic stability. For instance, Ui-Tei's rules emphasize an adenine or uracil at the 5' end of the guide strand and a relatively unstable 5' terminus to ensure proper strand loading into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) [19].

Machine learning (ML) models have superseded simple rule-based filtering by integrating multifaceted sequence and thermodynamic features to predict efficacy. These models range from linear regression to deep neural networks, trained on large datasets of experimentally validated siRNAs [22]. Sequence-level features are fundamental, but incorporating thermodynamic properties and predictions of target mRNA secondary structure significantly enhances prediction accuracy [22] [19]. Advanced tools now leverage these ML approaches to score and rank potential siRNA candidates, moving beyond binary pass/fail criteria [19].

Comparative Analysis of siRNA Design and Validation Workflows

A robust siRNA design pipeline integrates multiple computational stages, from target selection to final validation. The table below summarizes key quantitative data from recent studies employing such integrated approaches against viral and human disease targets.

Table 1: Comparative Data from Integrated siRNA Design Studies

| Study Target | # Initial Candidates | Key Filters Applied | Final Selected siRNAs | Reported In Vitro Knockdown Efficacy | Key Validation Assays | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 (NSP8, NSP12, NSP14) | 258 | Conservation (MSA), Huesken dataset (≥90% inhib.), Thermodynamics, Off-target BLAST | 4 (e.g., siRNA2, siRNA4) | 89%-97% reduction in viral S & ORF1b genes at 24 h.p.i. | Cytotoxicity, TCID50, RT-PCR | [18] |

| HSV-1 (UL15 gene) | N/A | Conservation (MSA), Rule-based (Ui-Tei, etc.), Off-target BLAST | 2 (siRNA1 & siRNA2) | ~78% predicted efficiency; 50% & 30% CPE inhibition in vitro | CPE assay, RT-PCR, MTT cytotoxicity | [21] |

| Human VEGF (Cancer) | N/A | GC content (30-52%), Rule-based, Thermodynamics | Multiple | Docking scores: -330 to -351 kcal/mol with Ago2 | Molecular Docking, MD Simulations | [20] |

| Human GPR10 (Uterine Fibroids) | 275 | Thermodynamics, Secondary structure, Off-target filtration | 10 (siRNA8 & siRNA12 leads) | >93.5% predicted silencing efficacy | Docking with Ago2, MD Simulations | [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation The transition from in silico prediction to biological reality necessitates standardized experimental validation. Key protocols include:

- Cytotoxicity Assay (e.g., MTT): Cells are transfected with siRNA candidates using lipid-based transfection reagents (e.g., X-tremeGENE). After incubation (e.g., 72 hours), MTT reagent is added and metabolically active cells reduce it to formazan crystals. Solubilized crystals are quantified spectrophotometrically at 570 nm to ensure siRNA treatments do not impair cell viability [21].

- Efficacy via RT-PCR: Following siRNA transfection and target challenge (e.g., viral infection), total RNA is extracted. Reverse transcription yields cDNA, which is used in quantitative PCR with primers for the target gene (e.g., viral S gene) and a housekeeping control. The relative fold change in target mRNA, calculated via the ΔΔCt method, quantifies knockdown efficiency [18].

- Functional Viral Assay (TCID50): For antiviral siRNAs, supernatant from infected, siRNA-treated cells is serially diluted and applied to fresh cell monolayers. The dilution that causes cytopathic effect (CPE) in 50% of wells is calculated, revealing the reduction in infectious viral titer due to siRNA treatment [18].

Visualization of siRNA Design and Mechanism

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the standard siRNA design workflow and the core RNAi mechanism.

Diagram 1: Integrated siRNA Design & Validation Workflow

Diagram 2: RNAi Mechanism & siRNA Structure

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table details critical materials and tools required for executing the computational design and experimental validation pipeline.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for siRNA Studies

| Item Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Databases | NCBI Nucleotide / Virus Database | Primary source for retrieving target mRNA and viral genome sequences in FASTA format for design initiation [18] [1]. |

| Alignment & Conservation Tools | MAFFT, Clustal Omega, MEGAX | Perform Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) to identify evolutionarily conserved regions across variants, which are optimal siRNA targets [18] [21]. |

| siRNA Design Servers | siDirect, i-Score Designer, IDT SciTools | Apply rule-based and machine learning algorithms to generate and score potential siRNA sequences from an input target [20] [19] [21]. |

| Off-Target Screening | NCBI BLAST | Used to screen candidate siRNA sequences against the human (or host) genome/transcriptome to minimize homology-driven off-target effects [18] [21]. |

| Structure & Energy Prediction | RNAfold, DuplexFold | Predict secondary structure and thermodynamic stability (ΔG) of siRNA duplexes and siRNA-mRNA interactions, informing efficiency [23] [19] [21]. |

| 3D Structure Prediction | AlphaFold 3, RNAComposer | Model tertiary structures of larger RNAs or RNA-protein complexes (e.g., RISC) for advanced mechanistic and docking studies [23]. |

| Transfection Reagent | X-tremeGENE, Lipofectamine | Lipid-based formulations that encapsulate negatively charged siRNA, facilitating its delivery across the cell membrane into the cytoplasm [21]. |

| Cell Viability Assay | MTT Reagent | A colorimetric assay that measures mitochondrial activity; used to confirm siRNA and delivery vehicle cytotoxicity [21]. |

| Quantification Core | RT-qPCR Kit (Reverse Transcriptase, SYBR Green) | Essential for converting target mRNA to cDNA and quantifying its abundance post-siRNA treatment to measure knockdown efficacy [18]. |

The landscape of siRNA design is defined by a powerful synergy between sophisticated algorithms and rigorous experimental biology. While computational tools provide an indispensable starting point—enabling the high-throughput screening of candidates based on conservation, specificity rules, and thermodynamic profiles—their true value is only unlocked through in vitro and eventually in vivo validation [18] [21]. The ultimate measure of a design algorithm's success is not its prediction score, but the statistically significant reduction in target mRNA (via RT-PCR) and the resulting functional outcome (e.g., reduced viral titer) it produces in the laboratory. As machine learning models evolve and integrate more complex features, this iterative cycle of prediction and validation remains the cornerstone of developing specific, efficacious, and safe siRNA therapeutics.

The identification of essential genes—those crucial for the survival or reproductive success of an organism—represents a critical frontier in biomedical research and therapeutic development [16]. For researchers and drug development professionals, these genes are promising targets for novel intervention strategies, particularly in combating pathogens and diseases like malaria and cancer. The primary challenge lies in efficiently pinpointing these genes among thousands of candidates, a process historically dependent on costly and time-consuming experimental methods. Computational approaches have emerged as powerful tools to overcome this bottleneck, enabling the prioritization of candidate genes for downstream experimental validation.

Machine learning (ML) models, especially when integrated with feature selection techniques, have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in predicting essential genes from complex genomic data [24]. These methods leverage patterns learned from model organisms and known essential genes to generate predictions in less-studied species or contexts. The integration of these computational predictions with robust experimental validation frameworks, particularly RNA interference (RNAi) and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), forms a cornerstone of modern functional genomics. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the dominant machine learning and feature selection methodologies used for essential gene prediction, detailing their performance characteristics, experimental validation protocols, and practical implementation requirements.

Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Approaches

Core Machine Learning Algorithms and Performance

Multiple machine learning algorithms have been applied to the problem of essential gene prediction, each with distinct strengths, weaknesses, and performance profiles. The selection of an appropriate algorithm often depends on the specific dataset characteristics, available computational resources, and the desired balance between interpretability and predictive power.

Random Forest (RF) is a versatile ensemble method that constructs multiple decision trees during training and outputs predictions based on their collective decision [25] [26]. Its key advantage lies in its ability to capture complex interaction effects between genetic features without assuming strict additivity, making it particularly suitable for genetic architectures where epistasis (gene-gene interactions) plays a significant role [25]. In genomic prediction tasks, RF has demonstrated performance comparable to classical Bayesian methods while offering greater computational efficiency and robustness to overfitting [25]. Studies predicting residual feed intake in pigs have achieved Spearman correlation coefficients of approximately 0.27 between observed and predicted values using RF models [26].

Support Vector Machines (SVM) operate by finding the optimal hyperplane that separates classes (e.g., essential vs. non-essential genes) in a high-dimensional feature space [27]. SVMs are particularly effective in scenarios where the number of features exceeds the number of observations, a common characteristic in genomic studies [27]. When applied to pig genomic data for feed efficiency prediction, SVM models outperformed other learners, achieving a correlation of 0.28 between observed and predicted values with high stability [26]. Their performance can be further enhanced through appropriate kernel selection and hyperparameter tuning.

Elastic Net combines the variable selection properties of LASSO (L1 regularization) with the stability of ridge regression (L2 regularization) [28]. This combination allows it to handle correlated predictor variables effectively—a common challenge in genomic data due to linkage disequilibrium between nearby genetic variants [28]. In predicting CYP2D6-associated CpG methylation levels, Elastic Net models demonstrated superior performance compared to linear regression and XGBoost, particularly when integrating both genetic and non-genetic features [28]. Its ability to automatically select significant variables while managing collinearity makes it particularly valuable for high-dimensional genomic datasets.

XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting) is an optimized implementation of gradient boosting that sequentially builds decision trees, with each new tree correcting errors made by previous ones [28]. This iterative approach often yields high prediction accuracy but requires careful hyperparameter tuning to prevent overfitting [28]. While XGBoost has shown excellent performance in various genomic prediction challenges, including cancer gene identification [29], its performance in predicting CYP2D6 methylation was marginally inferior to Elastic Net in some comparative studies [28].

Table 1: Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms for Essential Gene Prediction

| Algorithm | Key Strengths | Limitations | Reported Performance | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | Handles non-additive effects; Robust to overfitting; Provides feature importance metrics | Computationally intensive with many trees; Less interpretable than linear models | Spearman correlation: 0.27-0.28 in pig RFI prediction [26] | Genomic datasets with suspected epistatic interactions |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Effective in high-dimensional spaces; Memory efficient; Versatile through kernel functions | Performance dependent on kernel selection; Limited interpretability | Spearman correlation: 0.28 in pig RFI prediction [26] | Transcriptomic and proteomic data with clear separation boundaries |

| Elastic Net | Handles correlated features; Automatic feature selection; More interpretable than black-box models | Linear assumptions may miss complex interactions; Requires regularization tuning | Superior to XGBoost and Linear Regression for CYP2D6 methylation prediction [28] | SNP datasets with high linkage disequilibrium |

| XGBoost | High predictive accuracy; Handles missing data well; Extensive customization options | Prone to overfitting without careful tuning; Computationally demanding | Excellent for cancer gene classification [29]; Mixed performance for methylation prediction [28] | Large-scale genomic datasets with complex hierarchical patterns |

Feature Selection Methods for Enhanced Prediction

Feature selection is a critical pre-processing step in genomic prediction that identifies and retains the most informative genetic variants while excluding irrelevant or redundant features [24]. This process improves model interpretability, reduces computational requirements, and enhances generalization performance by mitigating the "curse of dimensionality" common in genomic studies where the number of features (e.g., SNPs) far exceeds the number of samples [24].

Filter Methods represent the simplest approach to feature selection, ranking individual features based on statistical measures of association with the phenotype independently of the ML algorithm [26]. Common implementations include univariate methods like correlation coefficients (e.g., spearcor) and association testing (e.g., genome-wide association study p-values), as well as multivariate filters like minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (mRMR) that account for interactions between features [25] [26]. The primary advantage of filter methods is their computational efficiency and resistance to overfitting, though univariate approaches may miss features that are only informative in combination with others [26].

Embedded Methods integrate feature selection directly into the model training process [26]. Algorithms like LASSO and Elastic Net perform automatic feature selection through regularization penalties that shrink coefficients of uninformative features toward zero [28]. Tree-based methods like Random Forest and XGBoost provide native feature importance scores based on how much each feature improves model performance across all decision trees [26]. Embedded methods typically yield better performance than filter methods but are more computationally intensive and algorithm-specific.

Wrapper Methods evaluate feature subsets by training a model on each candidate subset and assessing its performance [26]. While potentially offering the best performance, wrapper methods are computationally prohibitive for genomic datasets with thousands of features and are consequently less commonly used in practice [26].

Incremental Feature Selection (IFS) represents a hybrid approach that progressively adds features to a model based on their association strength, typically derived from GWAS p-values [25]. This method begins with the top-ranked SNP and adds markers stepwise until model performance stabilizes or degrades [25]. Applied to genomic prediction in plants and animals, IFS has demonstrated the ability to achieve comparable performance to models using all available SNPs while utilizing a significantly reduced feature set—in some cases improving prediction accuracy substantially [25].

Table 2: Comparison of Feature Selection Methods in Genomic Studies

| Method Type | Examples | Advantages | Disadvantages | Reported Impact on Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Univ.dtree, Spearcor, CForest, mRMR [26] | Computationally efficient; Resistant to overfitting; Algorithm-independent | Univariate methods ignore feature interactions; May select redundant features | With 50-250 SNPs, huge impact on prediction quality; With 1000+ SNPs, minimal influence [26] |

| Embedded Methods | LASSO, Elastic Net, Random Forest feature importance [26] [28] | Model-specific optimization; Balances feature selection with model training; Handles interactions | Computationally intensive; Less interpretable; Algorithm-dependent performance | Elastic Net showed best performance for CYP2D6 methylation prediction [28] |

| Wrapper Methods | Recursive Feature Elimination, Evolutionary Algorithms [26] | Potentially optimal feature subsets; Considers feature interactions thoroughly | Computationally prohibitive for genomic data; High risk of overfitting | Limited use in genomic prediction due to computational constraints [26] |

| Incremental Feature Selection | GWAS-based ranking with stepwise addition [25] | Systematic approach; Balances performance and feature set size; Clear stopping point | Dependent on initial ranking quality; Computationally intensive for large datasets | Achieved comparable performance with substantially fewer SNPs in plant/animal datasets [25] |

Experimental Validation of Computational Predictions

RNA Interference (RNAi) Validation Protocols

RNAi serves as a powerful experimental technique for validating computational predictions of gene essentiality by enabling targeted gene silencing and observation of resulting phenotypic effects [16]. The standard RNAi validation workflow involves several critical steps that must be meticulously executed to ensure reliable results.

The process begins with dsRNA Design and Synthesis, where double-stranded RNA molecules are designed to complement specific target gene sequences [16]. For validation experiments, these typically range from 200-500 base pairs in length to ensure efficient processing into siRNAs by Dicer enzymes [30]. The designed dsRNA can be synthesized in vitro using phage RNA polymerases (T7, T3, or SP6) or produced endogenously in genetically modified organisms expressing hairpin RNA constructs [30].

Delivery Methods vary depending on the target organism. In mosquito studies validating essential genes for malaria control, dsRNA was typically delivered through microinjection into the thorax or abdomen of adult mosquitoes [16]. As an alternative, non-invasive delivery methods include soaking (for aquatic organisms), feeding, or viral vector-mediated introduction [30]. For cellular systems, transfection reagents like lipofectamine are commonly employed to introduce dsRNA into cells.

Following delivery, Knockdown Efficiency Validation is crucial using quantitative RT-PCR to measure transcript abundance reduction [16]. Successful experiments typically achieve knockdown efficiencies exceeding 60%, with high-performing targets reaching 75-91% reduction in transcript levels [16]. This quantification ensures that observed phenotypic effects correlate with intended gene silencing rather than off-target effects.

Phenotypic Assessment forms the core of the validation process, where researchers examine the biological consequences of gene knockdown. In essential gene studies for vector control, key phenotypic readouts include mosquito survival rates, longevity, fecundity, and for parasite-interaction genes, quantification of pathogen development (e.g., Plasmodium berghei oocyte counts in midguts) [16]. Experimental designs should include appropriate control groups—typically LacZ-injected or untreated controls—to account for injection trauma and natural phenotypic variation [16].

RT-PCR Protocols for Validation Studies

Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) provides essential quantitative data on transcript abundance following gene perturbation, serving as a cornerstone for validating knockdown efficiency in RNAi experiments [16]. The standard workflow encompasses RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative PCR analysis.

RNA Extraction begins with sample homogenization using specialized buffers containing guanidinium thiocyanate to inactivate RNases [31]. Total RNA is typically purified using silica-membrane column-based kits (e.g., RNeasy Mini Kit), with recommended inputs of 30mg tissue or 1x10^6 cells per extraction [31]. RNA quality and concentration should be verified using spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio ~1.8-2.0) and integrity confirmed through agarose gel electrophoresis showing distinct 18S and 28S ribosomal RNA bands.

cDNA Synthesis converts purified RNA to stable complementary DNA using reverse transcriptase enzymes [31]. Standard 20μL reactions typically include 1μg total RNA, 4μL 5X reaction buffer, 1μL dNTP mix (10mM each), 2μL random hexamer or oligo(dT) primers (6pmol/μL), 1μL reverse transcriptase, and nuclease-free water to volume [31]. Reaction conditions generally involve priming at 25°C for 10 minutes, reverse transcription at 50°C for 30-60 minutes, and enzyme inactivation at 85°C for 5 minutes.

Quantitative PCR enables precise quantification of target transcript levels using sequence-specific detection. Typical 25μL reactions contain 1X PCR buffer, 2.5-3.5mM MgCl2, 0.2mM dNTPs, 0.5μM forward and reverse primers, 0.2μL DNA polymerase, 1μL cDNA template, and optional intercalating dyes (SYBR Green) or sequence-specific probes (TaqMan) [31]. Standard thermal cycling parameters include initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 minutes, followed by 35-40 cycles of denaturation (95°C for 30-45 seconds), annealing (primer-specific temperature for 45 seconds), and extension (72°C for 60 seconds) [31].

Data Analysis utilizes the comparative Cq (quantification cycle) method (2^(-ΔΔCq)) to calculate relative expression changes between experimental and control groups [16]. Normalization to reference genes (e.g., GAPDH, β-actin, ribosomal proteins) with stable expression under experimental conditions is essential for accurate quantification. Successful validation experiments typically demonstrate significant reduction (≥60%) in target transcript levels compared to controls, with statistical significance determined using t-tests or ANOVA with appropriate multiple testing corrections [16].

Case Study: Integrated Computational and Experimental Approach

A comprehensive study on malaria vector control exemplifies the powerful integration of machine learning prediction with experimental validation [16]. Researchers employed the CLassifier of Essentiality AcRoss EukaRyote (CLEARER), a machine learning algorithm trained on six model organisms (C. elegans, D. melanogaster, H. sapiens, M. musculus, S. cerevisiae, and S. pombe), to predict essential genes in Anopheles gambiae [16]. The classifier utilized 41,635 features derived from protein and gene sequences, functional domains, topological features, evolutionary conservation, subcellular localization, and Gene Ontology terms to generate predictions [16].

From 10,426 genes analyzed in An. gambiae, the algorithm identified 1,946 genes (18.7%) as predicted Cellular Essential Genes (CEGs), 1,716 (16.5%) as predicted Organism Essential Genes (OEGs), and 852 genes (8.2%) as essential in both categories [16]. For experimental validation, researchers selected the top three highly expressed non-ribosomal predictions—AGAP007406 (Elongation factor 1-alpha, Elf1), AGAP002076 (Heat shock 70kDa protein 1/8, HSP), and AGAP009441 (Elongation factor 2, Elf2)—along with arginase (AGAP008783), which was computationally inferred as essential through chokepoint analysis [16].

RNAi-mediated knockdown achieved efficiencies of 91% for arginase, 75% for Elf1, 63% for HSP, and 61% for Elf2 [16]. Phenotypic assessment revealed that HSP and Elf2 knockdown significantly reduced mosquito longevity (p<0.0001), while Elf1 and arginase knockdown had no effect on survival [16]. However, arginase knockdown significantly reduced P. berghei oocyte counts in mosquito midguts, indicating its importance for parasite development rather than mosquito survival [16]. This integrated approach successfully identified both mosquito survival genes (HSP, Elf2) and parasite development genes (arginase) as potential targets for vector control, demonstrating the power of combining computational prediction with targeted experimental validation.

Successful implementation of computational predictions with experimental validation requires access to specialized reagents, databases, and analytical tools. The following table summarizes key resources that support essential gene identification workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Essential Gene Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning Frameworks | scikit-learn, Ranger (R), XGBoost, TensorFlow | Implementation of ML algorithms for essential gene prediction | Model training, feature selection, and prediction generation [25] [26] |

| Feature Selection Tools | PLINK, MRMR, LASSO/Elastic Net implementations | Dimensionality reduction and identification of informative genetic features | Pre-processing of genomic data; selection of candidate genes [25] [26] [28] |

| Genomic Databases | STRING, OGEE, Database of Essential Genes | Source of training data and functional annotations | Feature generation; model training; functional interpretation of predictions [16] |

| RNAi Reagents | dsRNA synthesis kits (e.g., HiScribe), microinjection equipment | Experimental gene silencing | Validation of gene essentiality through targeted knockdown [16] [30] |

| qRT-PCR Reagents | RNA extraction kits, reverse transcriptase, SYBR Green/TaqMan assays | Quantification of gene expression changes | Validation of knockdown efficiency; expression profiling [16] [31] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | SeqinR, Protr, CodonW, rDNAse, DeepLoc | Generation of sequence-derived features for ML models | Computational feature extraction from genomic sequences [16] |

The integration of machine learning prediction with rigorous experimental validation represents a paradigm shift in essential gene identification. As demonstrated across multiple studies, computational approaches can dramatically accelerate target discovery by prioritizing candidates for downstream experimental investigation [16] [25]. The comparative analysis presented in this guide reveals that algorithm selection should be guided by dataset characteristics—with Random Forest and SVM excelling for complex genetic architectures, while Elastic Net provides superior performance for correlated SNP data [26] [28].

Feature selection emerges as a critical determinant of model performance, with incremental feature selection and multivariate filter methods offering particularly favorable balances between prediction accuracy and computational efficiency [25] [26]. The successful application of these computational approaches nevertheless remains dependent on robust experimental validation through RNAi and RT-PCR methodologies, which provide the essential biological confirmation of predicted gene-phenotype relationships [16].

For researchers embarking on essential gene identification projects, the recommended pathway involves: (1) appropriate algorithm selection based on data structure, (2) implementation of rigorous feature selection to enhance model generalizability, (3) careful design of validation experiments with proper controls, and (4) quantitative assessment of knockdown efficiency and phenotypic effects. This integrated approach maximizes the likelihood of identifying bona fide essential genes with potential therapeutic applications across diverse biological contexts.

Off-target effects represent a significant challenge in modern biomedical research, particularly in the development of therapeutic applications using advanced technologies like CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing and RNA interference (RNAi). These unintended effects occur when therapeutic molecules interact with non-target genes, transcripts, or proteins, potentially leading to confounding experimental results or adverse clinical consequences [32] [33]. In CRISPR systems, off-target effects typically involve DNA cleavage at genomic sites with sequence similarity to the intended target, while in RNAi applications, they involve the unintended silencing of genes with partial sequence complementarity to the designed RNA molecules [34]. The growing emphasis on precision medicine and targeted therapies has made the comprehensive assessment and mitigation of off-target activities a critical component of the drug development pipeline, necessitating robust bioinformatic strategies for risk prediction and experimental approaches for validation.

Bioinformatic Tools for Predicting Off-Target Effects

Bioinformatic prediction serves as the first line of defense against off-target effects in both genome editing and RNAi applications. These computational tools leverage algorithms to identify potential off-target sites based on sequence similarity, thereby enabling researchers to select optimal target sequences and design more specific reagents.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Bioinformatics Tools for Off-Target Prediction

| Tool Name | Primary Application | Prediction Basis | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas-OFFinder | CRISPR-Cas9 | Sequence homology & PAM compatibility | Genome-wide off-target search, supports various Cas enzymes | Does not account for chromatin context [35] [32] |

| CRISPRseek | CRISPR-Cas9 | Sequence homology & PAM compatibility | Comprehensive off-target profiling | Limited to in silico prediction only [32] |

| CLEARER | RNAi | Machine learning classifier | Predicts essential genes across eukaryotes; trained on 6 model organisms [16] | Relies on orthology which may not capture species-specific essentiality [16] |

| CCTop | CRISPR-Cas9 | Sequence homology & PAM compatibility | User-friendly interface, ranked off-target list | Predictive only, requires experimental validation [34] |

| CRISPOR | CRISPR-Cas9 | Multiple algorithms combined | Integrates various scoring systems, user-friendly design | Computational predictions may not match cellular conditions [34] |

These bioinformatic tools employ distinct algorithms to quantify potential off-target risks. For CRISPR systems, the off-target score is a quantitative measure derived from factors including sequence homology between the guide RNA and potential off-target sites, protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) compatibility, and local sequence context [32]. Tools like CRISPOR and CCTop provide valuable insights by predicting off-target effects based on sequence complementarity and mismatches, allowing for more informed guide RNA design [34]. For RNAi applications, approaches like the CLEARER algorithm utilize machine learning classifiers trained on multiple model organisms to predict essential genes that might be susceptible to off-target effects, incorporating features such as protein and gene sequence characteristics, functional domains, topological features, evolutionary conservation, subcellular localization, and Gene Ontology sets [16].

Experimental Validation of Off-Target Effects

While bioinformatic predictions provide a crucial starting point, experimental validation remains essential for comprehensive off-target assessment. The integration of computational predictions with rigorous experimental testing represents the current gold standard in the field.

CRISPR Off-Target Validation Methods

For CRISPR-based applications, several experimental techniques have been developed to identify and quantify off-target effects:

Digenome-seq: This in vitro method involves treating purified genomic DNA with CRISPR-Cas9, followed by whole-genome sequencing to identify cleavage patterns. The approach provides comprehensive profiling of off-target modifications based on the cleavage pattern and can reveal potential off-target sites throughout the genome [32].

GUIDE-seq: This cellular method utilizes short double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides that integrate into DNA double-strand breaks via the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway. The integrated tags then serve as markers for amplification and sequencing, allowing for genome-wide identification of off-target sites [34].

Amplicon Sequencing: For specific off-target sites identified through predictive models or experimental screens, targeted amplification via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) followed by next-generation sequencing (NGS) can confirm the presence and frequency of unintended edits. This targeted approach enables researchers to ascertain the frequency and nature of off-target mutations with high sensitivity [35] [32].

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS): As the most comprehensive approach, WGS provides complete characterization of all mutations in edited cells. However, it remains expensive and computationally intensive for routine application, making it more suitable for final therapeutic validation rather than initial screening [34].

RNAi Validation Using RT-PCR

For RNAi applications, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) serves as the analytical tool of choice for quantifying gene expression knockdown and validating target specificity [10]. The standard workflow involves:

- Delivery of RNAi triggers (siRNA or shRNA) to target cells

- RNA extraction after an appropriate incubation period

- Reverse transcription to generate complementary DNA (cDNA)

- Quantitative PCR amplification using gene-specific primers

- Analysis of threshold cycle (CT) values relative to control genes

This methodology provides sensitive and quantitative assessment of target gene silencing efficiency while also enabling detection of potential off-target effects on non-target genes through the use of additional primer sets. The high sensitivity of RT-PCR (capable of detecting as few as 100 copies/mL in optimized assays) makes it particularly valuable for comprehensive off-target profiling [3].

Workflow for Comprehensive Off-Target Assessment

Integrated Workflow for Off-Target Risk Assessment

A robust framework for off-target risk assessment integrates both computational and experimental approaches in a sequential manner. The common two-step verification method emerging from analysis of successful clinical applications involves: first, identifying numerous potential off-target loci using high-sensitivity detection methods and theoretical screens; and second, experimentally verifying these potential off-target effects using amplicon sequencing of the identified sites after nuclease treatment in biologically relevant models [36]. This integrated approach has become the standard for gene-editing therapeutic products that have successfully achieved investigational new drug (IND) clearance from regulatory authorities [36].

Strategies to Minimize Off-Target Effects

Several strategic approaches can significantly reduce the likelihood and impact of off-target effects in both research and therapeutic contexts:

CRISPR-Specific Mitigation Strategies

Guide RNA Optimization: Careful selection of target sequences with minimal homology to other genomic regions is fundamental. Using truncated gRNAs (17-18 nucleotides instead of standard 20 nucleotides) has been shown to improve specificity while maintaining sufficient on-target activity [32] [34].

High-Fidelity Cas Variants: Engineered Cas9 variants such as SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9, HypaCas9, and evoCas9 have been developed to reduce off-target effects through enhanced specificity. These variants are designed to have reduced non-specific binding without compromising on-target efficiency [34].

Dual Nickase Approach: Utilizing two guide RNAs with Cas9 nickases (rather than a single nuclease) requires simultaneous binding at adjacent sites to create a double-strand break, dramatically reducing the probability of off-target mutations [34].

Alternative CRISPR Systems: Cas12 and Cas13 systems offer different target recognition mechanisms that can inherently reduce off-target effects due to their unique recognition properties [32].

RNAi-Specific Optimization Approaches

Seed Region Analysis: Careful examination of the 6-8 nucleotide "seed" region of siRNAs to minimize complementarity to non-target transcripts.

Chemical Modifications: Incorporation of specific chemical modifications in synthetic RNAi triggers can enhance stability and reduce off-target silencing.

Pooled Approaches: Using pools of multiple RNAi triggers against the same target at lower concentrations can reduce off-target effects while maintaining on-target efficacy.

Table 2: Comparison of Off-Target Mitigation Strategies Across Technologies

| Strategy Category | CRISPR Applications | RNAi Applications | Relative Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Optimization | gRNA selection with minimal genome-wide homology | Seed region analysis & complementarity checking | High for both technologies |

| Reagent Engineering | High-fidelity Cas variants (eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) | Chemically modified siRNAs | Moderate to High |

| Delivery Optimization | Controlled expression systems, nanoparticle delivery | Lipid nanoparticles, controlled expression | Moderate |

| Alternative Systems | Cas12, Cas13 nucleases | miRNA mimetics, antisense oligonucleotides | Varies by application |

| Combination Approaches | Dual nickase system | Pooled siRNAs at lower concentrations | High |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Off-Target Assessment

| Reagent/Category | Primary Function | Specific Examples | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas Variants | Enhanced specificity genome editing | SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9, HypaCas9, evoCas9 | CRISPR-based experiments [34] |

| gRNA Design Tools | Optimal target selection & off-target prediction | CRISPOR, Cas-OFFinder, CCTop | CRISPR experimental design [32] [34] |

| Essential Gene Predictors | Identification of potential sensitive targets | CLEARER algorithm | RNAi target validation [16] |

| Next-Generation Sequencers | Comprehensive off-target detection | Illumina, PacBio systems | GUIDE-seq, Digenome-seq, amplicon sequencing [35] |

| Quantitative PCR Systems | Gene expression quantification & validation | RT-PCR platforms | RNAi validation [10] [3] |

| RNAi Delivery Reagents | Efficient introduction of RNAi triggers | Lipid nanoparticles, lentiviral vectors | In vitro and in vivo RNAi studies [16] |

The evolving landscape of off-target effect assessment reflects a maturation in our approach to biological technologies with therapeutic potential. While significant progress has been made in both prediction and validation methodologies, the absence of standardized guidelines continues to create challenges for consistent implementation across studies [33]. The most effective approach combines robust bioinformatic prediction using multiple complementary tools with rigorous experimental validation in biologically relevant systems. As these technologies continue to advance toward clinical application, the development of increasingly sensitive detection methods and standardized reporting frameworks will be essential for comprehensive risk assessment and the realization of safe, effective therapeutic interventions.

Integrated Framework Combining Prediction and Validation

A Step-by-Step Protocol from siRNA Design to RT-PCR Analysis

The efficacy of RNA interference (RNAi) hinges on the careful design of small interfering RNA (siRNA) molecules. Computational tools have become indispensable for predicting siRNA sequences that offer high gene silencing potency and minimal off-target effects. These tools employ sophisticated algorithms based on established and empirical design rules, such as those pioneered by Tuschl and colleagues, to analyze target mRNA sequences and generate candidate siRNAs with a high probability of success [37] [38]. By integrating factors like thermodynamic stability, GC content, and specificity checks, in-silico methods provide a robust foundation for selecting high-potency siRNAs before costly laboratory validation begins [39] [20].

This guide objectively compares the performance of computationally designed siRNAs, using supporting data from published experimental workflows. The process is framed within the broader thesis of validating computational predictions through subsequent RNAi and RT-PCR research, a critical step for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to implement reliable gene-silencing strategies.

Core Design Principles and Criteria

The foundation of effective siRNA design rests on a set of well-established bioinformatic principles. These rules guide the selection of siRNA sequences that are efficiently loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and specifically cleave their target mRNA.

The following table summarizes the key parameters and their ideal ranges for designing high-potency siRNAs.

Table 1: Key Criteria for Designing High-Potency siRNAs

| Parameter | Ideal Value/Range | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 21-23 nucleotides with 2-nucleotide 3' overhangs | Standard structure for RISC incorporation and efficacy [1] [38]. |

| Target Site Sequence | Start with an AA dinucleotide [37] | Facilitates the creation of siRNAs with 3' UU overhangs, which are highly effective. |

| GC Content | 30-52% | siRNAs with 30-50% GC content are more active than those with higher G/C content [37] [20]. |

| Specificity Check | BLAST analysis with <16-17 contiguous base pairs of homology to other genes | Minimizes off-target effects by ensuring sequence uniqueness [37]. |

| Thermodynamic Profile | Low stability at the 5' end of the antisense (guide) strand | Promotes correct strand selection and loading into RISC, enhancing silencing efficacy [20]. |

| Internal Repeats | Avoid stretches of >4 T's or A's | Prevents premature transcription termination in vector-based systems [37]. |

Adherence to these criteria during the initial design phase significantly increases the likelihood of identifying functional siRNAs. For instance, Ambion researchers (now Thermo Fisher) have noted that using these guidelines results in approximately half of all designed siRNAs yielding a >50% reduction in target mRNA levels [37].

Computational Tools and Workflow

The practical application of design principles is enabled by specialized software and online platforms. These tools automate the screening of mRNA sequences and rank siRNA candidates based on a combination of the criteria outlined above.

Table 2: Common Computational Tools for siRNA Design

| Tool | Key Features | Underlying Algorithm/Rules |

|---|---|---|

| siDirect | Focuses on reducing off-target effects; provides functional, target-specific siRNA sequences [20]. | Implements rules from Ui-Tei, Amarzguioui, and Reynolds for sequence selection [20]. |

| i-Score Designer | Scores siRNA sequences based on regression-based models to predict efficacy. | Uses a linear regression model to correlate sequence features with silencing activity. |

| Ambion's Algorithm | Proprietary algorithm incorporating a stringent specificity check; used in Silencer Select siRNAs. | Developed by Cenix Bioscience; accurately predicts potent siRNA sequences [39] [37]. |

A typical computational workflow begins with retrieving the target mRNA sequence in FASTA format from databases like NCBI. This sequence is then input into one or more design tools, which generate a list of candidate siRNAs. These candidates are subsequently filtered based on GC content, off-target potential, and thermodynamic properties. Advanced workflows often integrate molecular docking to predict the binding affinity of the siRNA guide strand with the Argonaute-2 (AGO2) protein, a core catalytic component of RISC [1] [20]. Promising candidates are then subjected to molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to confirm the stability of the siRNA-AGO2 complex under physiological conditions, providing a final layer of in-silico validation before moving to wet-lab experiments [1].

The diagram below illustrates this integrated computational workflow for selecting high-potency siRNAs.

Experimental Validation Protocols

In-silico Validation and Molecular Dynamics

For candidates shortlisted from initial screening, rigorous in-silico validation is performed. Molecular docking simulates the interaction between the siRNA and the human Argonaute-2 (h-Ago2) protein. Docking scores, typically reported in kcal/mol, indicate the binding affinity; more negative scores (e.g., between -330 and -351 kcal/mol for anti-VEGF siRNAs) suggest stronger and more stable binding, which is predictive of efficient RISC loading [20].

Subsequent Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations assess the stability of the siRNA-AGO2 complex over time. Key metrics include:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the stability of the complex. Values stabilizing around 2.1–2.6 Å indicate a stable complex formation [20].

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Identifies flexible regions within the complex. Fluctuations are often localized to the PAZ and MID domains of AGO2, which is normal for functional complexes [1] [20].

These simulations, performed under force fields like CHARMM-GUI/CHARMM36m, provide atomic-level insights into the stability and conformational dynamics of the siRNA-RISC complex, offering high confidence in the selected candidates before biochemical testing [1].

In-vitro Validation with RT-qPCR

A critical step in validating computational predictions is measuring the knockdown of the target mRNA following siRNA delivery. Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) is the most common method for this. However, a key technical consideration is the placement of the RT-qPCR amplicon.

A study investigating siRNA efficacy against Protein Kinase C-epsilon (PKCε) demonstrated that primers designed to amplify a region 3' to the siRNA cleavage site can fail to detect the knockdown. This is because the 3' mRNA fragment resulting from RISC-mediated cleavage may not be efficiently degraded and can still be reverse-transcribed, leading to false-negative results [40].

Protocol: RT-qPCR for siRNA Validation

- Transfection: Transfert cells with the candidate siRNA at low concentrations (<30 nM) to minimize off-target effects [39]. Use a scrambled sequence siRNA and a non-targeting control as negative controls.

- RNA Isolation: Extract total RNA 24-72 hours post-transfection using a kit such as the RNeasy mini kit.

- cDNA Synthesis: Synthesize cDNA from 1 μg of total RNA using M-MLV reverse transcriptase with either random hexamers or oligo(dT) primers.

- qPCR: Perform qPCR using a master mix like Power SYBR Green. Crucially, design primers to amplify a region 5' to or spanning the siRNA target site to ensure accurate detection of cleavage [40]. Normalize results to a housekeeping gene (e.g., β-actin).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of mRNA knockdown using the ΔΔCt method.

The inclusion of multiple siRNAs (≥2) targeting the same gene is a vital control. Different siRNAs with comparable silencing efficacy should induce similar phenotypic changes, increasing confidence that the observed effects are on-target [39].

Performance Comparison of Designed siRNAs

The ultimate test of computational design is the empirical performance of the siRNA candidates. The table below synthesizes data from multiple studies, comparing the in-silico predictions with experimental outcomes for siRNAs targeting different genes.

Table 3: Comparison of Computationally Designed siRNAs and Validation Data

| Target Gene / Study | Key Design Criteria | In-Silico Prediction | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPR10 [1] | Layered refinement from 275 candidates using thermodynamics, off-target filtration, and Ago2 docking. | siRNA8 & siRNA12 showed robust Ago2 binding and >93.5% predicted silencing efficacy. | MD simulations confirmed structural stability. (The article focuses on computational validation). |

| VEGF [20] | GC content (30-52%), thermodynamic stability, Ago2 docking. | Docking scores: -330 to -351 kcal/mol. MD simulations showed stable complexes (RMSD: 2.1-2.6 Å). | (The study is computational; experimental validation is implied as the next step). |

| General Guidelines [39] [37] | AA dinucleotide start, 30-50% GC content, specificity filter. | ~50% of siRNAs yield >50% mRNA reduction; ~25% yield 75-95% reduction. | Confirmed via RT-qPCR and/or protein-level analysis (Western blot). |

The data demonstrate that a rational, computationally-driven design process can consistently yield siRNA candidates with high predicted efficacy and stability. The close agreement between docking scores, MD simulation results, and final knockdown efficiencies underscores the reliability of these in-silico methods.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Translating computational designs into validated results requires a suite of reliable laboratory reagents. The following table details key solutions used in the experiments cited in this guide.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for siRNA Experiments

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Silencer Select siRNAs (Thermo Fisher) | Pre-designed and validated siRNAs for gene silencing. | Guaranteed silencing reagents; designed with a proprietary algorithm for high potency [37]. |

| Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Thermo Fisher) | Transfection reagent for introducing siRNA into mammalian cells. | Used to transfect HDMECs with siRNA at 1-10 nM concentrations [40]. |

| RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) | For total RNA extraction from cell cultures, including siRNA-treated cells. | RNA extraction 24-72 hours post-transfection for downstream RT-qPCR analysis [40]. |

| Power SYBR Green Mastermix (Applied Biosystems) | Fluorescent dye for detection of PCR amplification in real-time qPCR. | Used for RT-qPCR to quantify mRNA knockdown levels post-siRNA treatment [40]. |

| pSilencer Vectors (Thermo Fisher) | siRNA expression vectors for long-term or stable gene silencing studies. | Used to clone and express hairpin siRNAs from RNA Pol III promoters (U6, H1) [37] [38]. |

| GeneArt Gene Synthesis (Thermo Fisher) | Synthesis of siRNA-resistant optimized genes for rescue controls. | Provides a definitive control to confirm siRNA specificity by rescuing the phenotype [39]. |

The integration of computational tools into the siRNA design workflow has dramatically streamlined the process of identifying high-potency silencing molecules. By adhering to established design rules and leveraging sophisticated in-silico validation through docking and dynamics, researchers can significantly increase their success rate. This guide has outlined a standardized pathway from sequence selection to experimental confirmation, emphasizing the critical need to validate computational predictions with rigorous experimental protocols, particularly RT-qPCR with carefully designed primers. As these methodologies continue to mature, they will undoubtedly accelerate the development of RNAi-based therapeutics and functional genomics research.

Comparative Analysis of siRNA Delivery Methods

Selecting the optimal delivery method is a critical step in any siRNA experiment, as it directly impacts gene silencing efficiency, cell viability, and the overall reliability of the results. The choice often involves balancing these competing factors based on the specific experimental needs and cell type used. The table below provides a structured comparison of the most common non-viral transfection techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Key siRNA Transfection Methods

| Method | Mechanism | Transfection Efficiency | Cell Viability | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipofection (e.g., Lipofectamine RNAiMAX) | Cationic lipids form lipoplexes with siRNA, entering cells via endocytosis [41]. | High for many adherent cell lines [41]. | Moderate to High (dose-dependent) [42] [41]. | Simple protocol, high reproducibility, versatile for many cell types [41]. | Can be less effective in cells with low endocytic activity (e.g., some lymphocytes); potential cytotoxicity at high concentrations [41]. | High-throughput screening in standard cell lines (e.g., HeLa, HEK-293T) [43]. |

| Electroporation | Electrical pulses create temporary pores in the cell membrane for siRNA entry [41]. | Very High, including for hard-to-transfect cells [41]. | Low (high cytotoxicity if not optimized) [41]. | Effective for primary cells, stem cells, and immune cells; no vector required [41]. | Requires specialized equipment; complex parameter optimization; high toxicity [41]. | Transfection of primary cells and hard-to-transfect immune cells [41]. |