Frequentist vs. Bayesian Parameter Estimation: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Frequentist and Bayesian statistical paradigms, tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development.

Frequentist vs. Bayesian Parameter Estimation: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Frequentist and Bayesian statistical paradigms, tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development. We explore the foundational philosophies, contrasting how Frequentists view probability as a long-run frequency and parameters as fixed, against Bayesians who treat probability as a degree of belief and parameters as random variables. The scope extends to methodological applications in clinical trials and A/B testing, troubleshooting common challenges like parameter identifiability and prior selection, and a comparative validation of both frameworks based on recent studies of accuracy, uncertainty quantification, and performance in data-rich versus data-sparse scenarios. The goal is to equip practitioners with the knowledge to select the right statistical tool for their specific research question.

Core Philosophies: Understanding the Bedrock of Frequentist and Bayesian Reasoning

The interpretation of probability is not merely a philosophical exercise; it is the foundation upon which different frameworks for statistical inference are built. For researchers and scientists in drug development, the choice between the frequentist and Bayesian interpretation dictates how experiments are designed, data is analyzed, and conclusions are drawn. The core divergence lies in the very definition of probability: the long-run frequency of an event occurring in repeated trials, versus a subjective degree of belief in a proposition's truth [1]. This paper provides an in-depth technical overview of how these two interpretations of probability inform and shape the methodologies of frequentist and Bayesian parameter estimation, with a specific focus on applications relevant to scientific and pharmaceutical research.

Foundational Concepts and Definitions

The Long-Run Frequency Interpretation

The frequentist interpretation, central to classical statistics, defines the probability of an event as its limiting relative frequency of occurrence over a large number of independent and identical trials [2]. In this framework, probability is an objective property of the physical world. A probability value is meaningful only in the context of a repeatable experiment.

- Formal Definition: If an experiment is repeated (n) times under identical conditions and an event (A) occurs (nA) times, then the probability of (A) is defined as (P(A) = \lim{n\to\infty} \frac{n_A}{n}) [2] [3].

- Fixed Parameters: In frequentist inference, parameters of a population (e.g., the true mean effect size of a drug) are considered fixed, unknown constants. They are not assigned probability distributions [4] [5].

- Foundation for Inference: Statistical procedures, such as hypothesis testing and confidence intervals, are justified by their long-run behavior under hypothetical repeated sampling [3].

The Degree of Belief (Bayesian) Interpretation

The Bayesian interpretation treats probability as a quantitative measure of uncertainty, or degree of belief, in a hypothesis or statement [6]. This belief is personal and subjective, reflecting an individual's state of knowledge. Unlike the frequentist view, this interpretation can be applied to unique, non-repeatable events.

- Formal Definition: Probability is conditional on personal knowledge. A probability of 0.7 for a successful drug trial means the analyst has a 70% degree of belief in that outcome, based on available information [6] [7].

- Probabilistic Parameters: Parameters are treated as random variables, allowing analysts to express uncertainty about their values using probability distributions [4] [8].

- Foundation for Inference: The engine of Bayesian inference is Bayes' Theorem, which provides a mathematical rule for updating beliefs in light of new evidence [6] [9].

Mathematical Frameworks and Estimation Protocols

The Frequentist Paradigm and Maximum Likelihood Estimation

Frequentist statistics is grounded in the idea that conclusions should be based solely on the data at hand, with no incorporation of prior beliefs. The core frequentist procedure for parameter estimation is Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE).

- Objective Function: The likelihood function, (L(\theta | x) = P(Data | \theta)), is a function of the parameter (\theta) given the fixed, observed data. The MLE is the value of (\theta) that maximizes this function: (\hat{\theta}{MLE} = \arg\max{\theta} L(\theta | x)) [10].

- Uncertainty Quantification: Uncertainty in the MLE is expressed through the sampling distribution—the distribution of the estimate (\hat{\theta}) across hypothetical repeated samples from the population. This is operationalized via confidence intervals [3] [5].

- Confidence Interval Interpretation: A 95% confidence interval means that if the same experiment were repeated infinitely, 95% of the calculated intervals would contain the true, fixed parameter value. It is not correct to say there is a 95% probability that the specific interval from one's experiment contains the true parameter [3] [4].

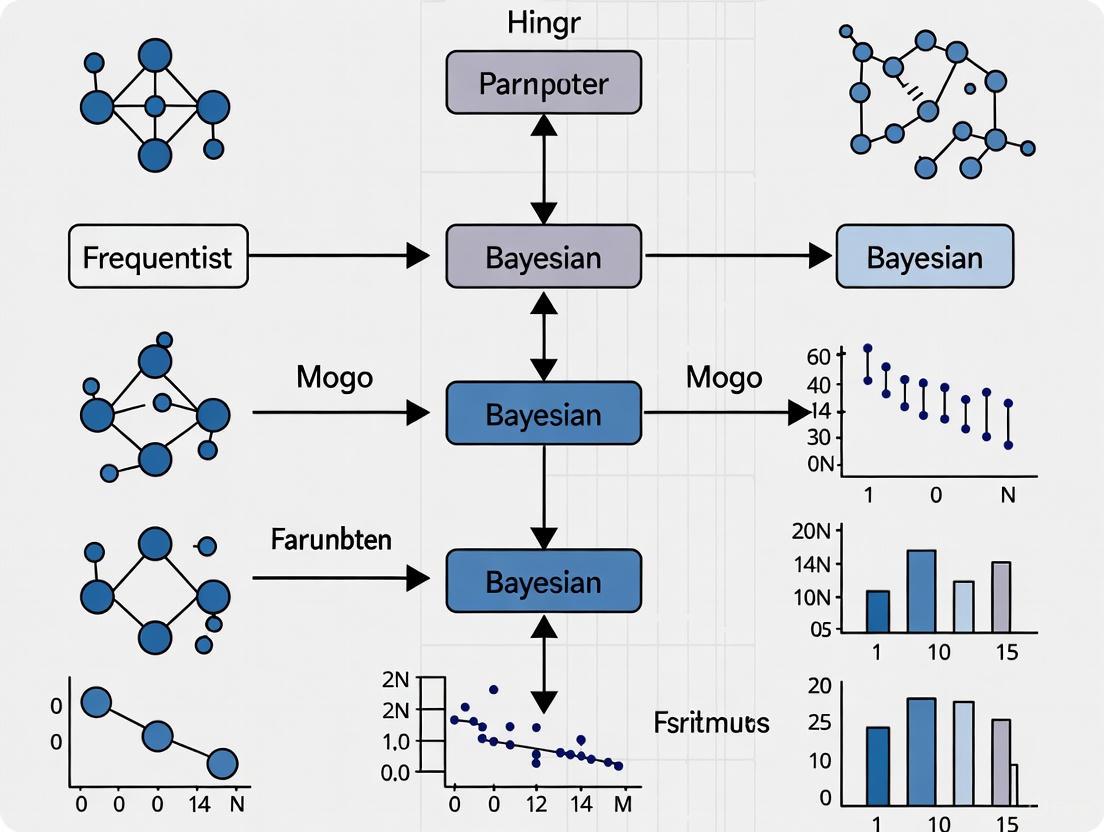

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow of frequentist parameter estimation.

The Bayesian Paradigm and Posterior Estimation

Bayesian statistics formalizes the process of learning from data. It begins with a prior belief about an unknown parameter and updates this belief using observed data to arrive at a posterior distribution.

- Bayes' Theorem: The mathematical foundation is given by (P(\theta | Data) = \frac{P(Data | \theta) P(\theta)}{P(Data)}), where:

- (P(\theta)) is the prior distribution, representing belief about (\theta) before seeing the data.

- (P(Data | \theta)) is the likelihood function, describing the probability of the data under different parameter values.

- (P(Data)) is the marginal likelihood or evidence, a normalizing constant.

- (P(\theta | Data)) is the posterior distribution, representing the updated belief about (\theta) after considering the data [6] [9] [8].

- Computational Methods: For complex models, the posterior distribution is often intractable analytically. Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods are a class of algorithms used to generate samples from the posterior distribution, enabling inference [4] [10].

- Uncertainty Quantification: Uncertainty is directly captured by the posterior distribution. A 95% credible interval is an interval which contains 95% of the posterior probability. It is correct to say there is a 95% probability that the true parameter lies within this specific interval, given the data and prior [4] [8].

The following diagram illustrates the iterative updating process of Bayesian parameter estimation.

Comparative Analysis: A Researcher's Perspective

The following table provides a structured, quantitative comparison of the two approaches across key dimensions relevant to research scientists and drug development professionals.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Frequentist and Bayesian Parameter Estimation

| Aspect | Frequentist Approach | Bayesian Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Definition of Probability | Long-run relative frequency [2] [7] | Subjective degree of belief [6] [7] |

| Nature of Parameters | Fixed, unknown constants [4] [5] | Random variables with probability distributions [4] [8] |

| Incorporation of Prior Knowledge | Not permitted; inference is based solely on the current data [5] | Central to the method; formally incorporated via the prior distribution (P(\theta)) [4] [8] |

| Primary Output | Point estimate (e.g., MLE) and confidence interval [3] [10] | Full posterior probability distribution (P(\theta|Data)) [9] [8] |

| Interval Interpretation | Confidence Interval: Frequency properties in repeated sampling [3] [4] | Credible Interval: Direct probability statement about the parameter [4] [8] |

| Computational Demand | Generally lower; relies on optimization (e.g., MLE) [10] | Generally higher; often requires MCMC simulation [4] [10] |

| Handling of Small Samples | Can be unstable; wide confidence intervals [4] | Can be stabilized with informative priors [4] |

| Decision-making Framework | Hypothesis testing (p-values), reject/do not reject (H_0) [3] [4] | Direct probability on hypotheses (e.g., (P(H_0 | Data))) [4] |

Experimental Protocols and Applications in Drug Development

Protocol: Frequentist Hypothesis Test for a Clinical Trial Endpoint

This protocol outlines the steps for a standard frequentist analysis of a primary efficacy endpoint, such as the difference in response rates between a new drug and a control.

Define Hypotheses:

- Null Hypothesis ((H_0)): The drug has no effect (e.g., response rate difference (\delta = 0)).

- Alternative Hypothesis ((H_1)): The drug has an effect (e.g., (\delta \neq 0)).

Choose Significance Level: Set (\alpha) (Type I error rate), typically 0.05.

Calculate Test Statistic: Based on the collected data (e.g., number of responders in each arm), compute a test statistic (e.g., a z-statistic or chi-square statistic).

Determine the P-value: The p-value is the probability of observing a test statistic as extreme as, or more extreme than, the one calculated, assuming (H_0) is true [3] [4]. It is computed from the theoretical sampling distribution.

Draw Conclusion: If (p-value \leq \alpha), reject (H0) in favor of (H1), concluding a statistically significant effect. If (p-value > \alpha), fail to reject (H_0) [3].

Protocol: Bayesian Analysis for a Clinical Trial Endpoint

This protocol describes how to use Bayesian methods to estimate the same efficacy endpoint, potentially incorporating prior information.

Specify the Prior Distribution ((P(\theta))):

- For a response rate (\theta), a Beta distribution is a common conjugate prior.

- Vague Prior: Use a Beta(1,1) to represent minimal prior knowledge.

- Informative Prior: Use a Beta((\alpha), (\beta)) whose shape is determined from historical data or expert opinion [9].

Define the Likelihood ((P(Data|\theta))): For binary response data, the likelihood is a Binomial distribution.

Compute the Posterior Distribution ((P(\theta|Data))):

- With a Beta prior and Binomial likelihood, the posterior is also a Beta distribution: Beta((\alpha + s), (\beta + f)), where (s) is the number of successes and (f) is the number of failures in the current trial [9].

- For complex models, use MCMC software (e.g., Stan, PyMC3) to sample from the posterior [10].

Summarize the Posterior: Report the posterior mean/median, and a 95% credible interval (e.g., the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the posterior samples). Calculate (P(\theta{drug} > \theta{control} | Data)) to directly assess the probability of efficacy [4] [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Statistical Estimation

Table 2: Essential Analytical Tools for Parameter Estimation

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Frequentist Example | Bayesian Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Likelihood Function | Quantifies how well the model parameters explain the observed data. | Core for MLE; used to find the parameter value that maximizes it. | One component of Bayes' Theorem; combined with the prior. |

| Optimization Algorithm | Finds the parameter values that optimize (maximize/minimize) an objective function. | Used to find the Maximum Likelihood Estimate (MLE). | Less central; sometimes used for finding the mode of the posterior (MAP). |

| MCMC Sampler | Generates random samples from a complex probability distribution. | Not typically used. | Critical reagent (e.g., Gibbs, HMC, NUTS) for sampling from the posterior distribution [10]. |

| Prior Distribution | Encodes pre-existing knowledge or assumptions about a parameter before data is seen. | Not used. | Critical reagent; must be chosen deliberately, from vague to informative [8]. |

The dichotomy between the long-run frequency and degree-of-belief interpretations of probability has given rise to two powerful, yet philosophically distinct, frameworks for statistical inference. The frequentist approach, with its emphasis on objectivity and error control over repeated experiments, provides the foundation for much of classical clinical trial design and analysis. In contrast, the Bayesian approach offers a flexible paradigm for iterative learning, directly quantifying probabilistic uncertainty and formally incorporating valuable prior information. For the modern drug development professional, the choice is not necessarily about which is universally superior, but about which tool is best suited for a specific research question. An emerging trend is the strategic use of both, such as using Bayesian methods for adaptive trial designs and frequentist methods for final confirmatory analysis. Understanding the core principles, protocols, and trade-offs outlined in this guide is essential for conducting robust, interpretable, and impactful research.

In statistical inference, the interpretation of probability and the nature of parameters represent a fundamental philosophical divide between two dominant paradigms: frequentist and Bayesian statistics. This dichotomy not only shapes theoretical frameworks but also directly influences methodological approaches across scientific disciplines, including pharmaceutical research and drug development. The core distinction centers on whether parameters are viewed as fixed constants to be estimated or as random variables with associated probability distributions [11] [12].

Frequentist statistics, historically developed by Fisher, Neyman, and Pearson, treats parameters as fixed but unknown quantities that exist in nature [3]. Under this framework, probability is interpreted strictly as the long-run frequency of events across repeated trials [11]. In contrast, Bayesian statistics, formalized through the work of Bayes, de Finetti, and Savage, treats parameters as random variables with probability distributions that represent uncertainty about their true values [11]. This probability is interpreted as a degree of belief, which can be updated as new evidence emerges [12].

The choice between these perspectives carries significant implications for experimental design, analysis techniques, and interpretation of results in research settings. This technical guide examines the theoretical foundations, practical implementations, and comparative strengths of both approaches within the context of parameter estimation research.

Philosophical Foundations and Interpretive Frameworks

The Frequentist Perspective: Parameters as Fixed Constants

In frequentist inference, parameters (denoted as θ) are considered fixed properties of the underlying population [3]. The observed data are viewed as random realizations from a data-generating process characterized by these fixed parameters. Statistical procedures are consequently evaluated based on their long-run performance across hypothetical repeated sampling under identical conditions [3].

The frequentist interpretation of probability is fundamentally tied to limiting relative frequencies. For instance, when a frequentist states that the probability of a coin landing heads is 0.5, they mean that in a long sequence of flips, the coin would land heads approximately 50% of the time [12]. This interpretation avoids subjective elements but restricts probability statements to repeatable events.

Frequentist methods focus primarily on the likelihood function, ( P(X|\theta) ), which describes the probability of observing the data ( X ) given a fixed parameter value ( \theta ) [3]. Inference is based solely on this function, without incorporating prior beliefs about which parameter values are more plausible.

The Bayesian Perspective: Parameters as Random Variables

Bayesian statistics assigns probability distributions to parameters, effectively treating them as random variables [11] [13]. This approach allows probability statements to be made directly about parameters, reflecting the analyst's uncertainty regarding their true values. The Bayesian interpretation of probability is epistemic rather than frequentist, representing degrees of belief about uncertain propositions [12].

The foundation of Bayesian inference is Bayes' theorem, which provides a mathematical mechanism for updating prior beliefs about parameters ( \theta ) in light of observed data ( X ) [13] [14]:

[ P(\theta|X) = \frac{P(X|\theta)P(\theta)}{P(X)} ]

Where:

- ( P(\theta|X) ) is the posterior distribution, representing updated beliefs about parameters after observing data

- ( P(X|\theta) ) is the likelihood function, identical to that used in frequentist statistics

- ( P(\theta) ) is the prior distribution, encoding pre-existing beliefs about the parameters

- ( P(X) ) is the marginal likelihood, serving as a normalizing constant

A Bayesian would thus assign a probability to a hypothesis about a parameter value, such as "the probability that this drug reduces mortality by more than 20% is 85%," a statement that is conceptually incompatible with the frequentist framework [11].

The "Fixed and Vary" Dichotomy

The distinction between these approaches is often summarized by the maxim: "Frequentist methods treat parameters as fixed and data as random, while Bayesian methods treat parameters as random and data as fixed" [12]. This distinction, while conceptually helpful, can be overstated. Both approaches acknowledge that there is a true underlying data-generating process; they differ primarily in how they represent uncertainty about that process and how they incorporate information [12].

Table 1: Core Philosophical Differences Between Frequentist and Bayesian Approaches

| Aspect | Frequentist Approach | Bayesian Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of parameters | Fixed, unknown constants | Random variables with probability distributions |

| Interpretation of probability | Long-run frequency of events | Degree of belief or uncertainty |

| Inference basis | Likelihood alone | Likelihood combined with prior knowledge |

| Primary focus | Properties of estimators over repeated sampling | Probability statements about parameters given observed data |

| Uncertainty quantification | Confidence intervals, p-values | Credible intervals, posterior probabilities |

Methodological Implications for Parameter Estimation

Frequentist Estimation Methods

Frequentist parameter estimation focuses on constructing procedures with desirable long-run properties. The most common approaches include:

Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) MLE seeks the parameter values that maximize the likelihood function ( P(X|\theta) ), making the observed data most probable under the assumed statistical model [3]. The Fisherian reduction provides a systematic framework for this approach: determine the likelihood function, reduce to sufficient statistics, and invert the distribution to obtain parameter estimates [3].

Confidence Intervals Frequentist confidence intervals provide a range of plausible values for the fixed parameter. The correct interpretation is that in repeated sampling, 95% of similarly constructed intervals would contain the true parameter value [11] [3]. This is often misinterpreted as the probability that the parameter lies within the interval, which is a Bayesian interpretation.

Neyman-Pearson Framework This approach formalizes hypothesis testing through predetermined error rates (Type I and Type II errors) and power analysis [3]. The focus is on controlling the frequency of incorrect decisions across many hypothetical replications of the study.

Bayesian Estimation Methods

Bayesian estimation focuses on characterizing the complete posterior distribution of parameters, which represents all available information about them [13] [14].

Bayes Estimators A Bayes estimator minimizes the posterior expected value of a specified loss function [13]. For example:

- Under squared error loss, the Bayes estimator is the mean of the posterior distribution

- Under absolute error loss, the Bayes estimator is the median of the posterior distribution

- Under 0-1 loss, the Bayes estimator is the mode of the posterior distribution [13]

Conjugate Priors When the prior and posterior distributions belong to the same family, they are called conjugate distributions [13]. This mathematical convenience simplifies computation and interpretation. For example:

- Gaussian likelihood with Gaussian prior for the mean yields Gaussian posterior

- Poisson likelihood with Gamma prior yields Gamma posterior

- Bernoulli likelihood with Beta prior yields Beta posterior [13]

Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Methods For complex models without conjugate solutions, MCMC methods simulate draws from the posterior distribution, allowing empirical approximation of posterior characteristics [11]. These computational techniques have dramatically expanded the applicability of Bayesian methods to sophisticated real-world problems.

Table 2: Comparison of Estimation Approaches in Frequentist and Bayesian Paradigms

| Estimation Aspect | Frequentist Methods | Bayesian Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Point estimation | Maximum likelihood, Method of moments | Posterior mean, median, or mode |

| Uncertainty quantification | Standard errors, confidence intervals | Posterior standard deviations, credible intervals |

| Hypothesis testing | p-values, significance tests | Bayes factors, posterior probabilities |

| Incorporation of prior information | Not directly possible | Central to the approach |

| Computational complexity | Typically lower | Typically higher, especially for complex models |

Experimental Design and Workflow

The differing conceptualizations of parameters lead to distinct approaches to experimental design and analysis. The following workflow diagrams illustrate these differences.

Frequentist Experimental Workflow

Diagram 1: Frequentist hypothesis testing workflow

The frequentist workflow emphasizes predefined hypotheses and sampling plans, with analysis decisions based on the long-run error properties of the statistical procedures [3]. The focus is on controlling Type I error rates across hypothetical replications of the experiment.

Bayesian Experimental Workflow

Diagram 2: Bayesian iterative learning workflow

The Bayesian workflow emphasizes iterative learning, where knowledge is continuously updated as new evidence accumulates [11] [14]. The posterior distribution from one analysis becomes the prior for the next, creating a natural framework for cumulative science.

Application in Pharmaceutical Research

Uncertainty Quantification in Drug Discovery

In pharmaceutical research, accurately quantifying uncertainty is crucial for decision-making given the substantial costs and ethical implications of drug development [15]. Bayesian methods are particularly valuable in this context because they provide direct probability statements about treatment effects, which align more naturally with decision-making needs [15].

A recent application in quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling demonstrates how Bayesian approaches enhance uncertainty quantification, especially when dealing with censored data where precise measurements are unavailable for some observations [15]. By incorporating prior knowledge and providing full posterior distributions, Bayesian methods offer more informative guidance for resource allocation decisions in early-stage drug discovery.

Adaptive Clinical Trial Designs

Bayesian methods are increasingly employed in adaptive clinical trial designs, where treatment assignments or sample sizes are modified based on interim results [11]. These designs allow for more efficient experimentation by:

- Stopping trials early for efficacy or futility

- Adjusting randomization ratios to favor promising treatments

- Incorporating historical data through informative priors

- Seamlessly progressing through developmental phases [11]

The ability to make direct probability statements about treatment effects facilitates these adaptive decisions, as researchers can calculate quantities such as ( P(\theta > 0 | data) ), representing the probability that a treatment is effective given the current evidence.

Optimal Experimental Design

Both frequentist and Bayesian approaches inform optimal experimental design, though with different criteria. Frequentist optimal design typically focuses on maximizing power or minimizing the variance of estimators [16]. This often involves calculating Fisher information matrices and optimizing their properties [16].

Bayesian optimal design incorporates prior information and typically aims to minimize expected posterior variance or maximize expected information gain [16]. This approach is particularly valuable when prior information is available or when experiments are costly, as it can significantly improve efficiency.

Table 3: Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Development

| Application Area | Frequentist Approach | Bayesian Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical trial design | Fixed designs with predetermined sample sizes | Adaptive designs with flexible sample sizes |

| Dose-response modeling | Nonlinear regression with confidence bands | Hierarchical models with shrinkage estimation |

| Safety assessment | Incidence rates with confidence intervals | Hierarchical models borrowing strength across subgroups |

| Pharmacokinetics | Nonlinear mixed-effects models | Population models with informative priors |

| Meta-analysis | Fixed-effect and random-effects models | Hierarchical models with prior distributions |

Research Reagent Solutions: Statistical Tools for Parameter Estimation

The practical implementation of parameter estimation methods requires specialized statistical software and computational tools. The following table summarizes key resources relevant to researchers in pharmaceutical development and other scientific fields.

Table 4: Essential Statistical Software for Parameter Estimation

| Software Tool | Function | Primary Paradigm | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| R | Statistical programming environment | Both | Comprehensive packages for both frequentist and Bayesian analysis |

| Stan | Probabilistic programming | Bayesian | Full Bayesian inference with MCMC sampling |

| PyMC3 | Probabilistic programming | Bayesian | Flexible model specification with gradient-based MCMC |

| SAS PROC MCMC | Bayesian analysis | Bayesian | Bayesian modeling within established SAS environment |

| bayesAB | Bayesian A/B testing | Bayesian | Easy implementation of Bayesian hypothesis tests |

| drc | Dose-response analysis | Frequentist | Nonlinear regression for dose-response modeling |

| grofit | Growth curve analysis | Frequentist | Model fitting for longitudinal growth data |

The distinction between parameters as fixed constants versus random variables represents more than a philosophical debate; it fundamentally shapes methodological approaches to statistical inference. The frequentist perspective, with its emphasis on long-run error control and repeatable sampling properties, provides a robust framework for many research applications. The Bayesian perspective, with its ability to incorporate prior knowledge and provide direct probability statements about parameters, offers compelling advantages for sequential decision-making and complex hierarchical models.

In pharmaceutical research and drug development, both approaches have valuable roles to play. Frequentist methods remain the standard for confirmatory clinical trials in many regulatory contexts, while Bayesian methods offer increasing value in exploratory research, adaptive designs, and decision-making under uncertainty. Modern statistical practice often blends elements from both paradigms, leveraging their respective strengths to address complex scientific questions more effectively.

As computational power continues to grow and sophisticated modeling techniques become more accessible, the integration of both frequentist and Bayesian approaches will likely expand, providing researchers with an increasingly rich toolkit for parameter estimation and uncertainty quantification across diverse scientific domains.

The frequentist approach to statistical inference, dominant in many scientific fields including drug development, is built upon a specific interpretation of probability. In this framework, probability represents the long-run frequency of an event occurring over numerous repeated trials or experiments [17] [4]. This worldview treats population parameters (such as the true mean treatment effect) as fixed, unknown quantities that exist in reality [10]. The core objective of frequentist analysis is to estimate these parameters and draw conclusions based solely on the evidence provided by the collected sample data, without incorporating external beliefs or prior knowledge [4]. This data-driven methodology provides the foundation for most traditional statistical procedures, including hypothesis testing and the construction of confidence intervals, which remain cornerstone techniques in clinical research and pharmaceutical development.

The historical development of frequentist statistics in the early 20th century was shaped significantly by the work of Ronald Fisher, Jerzy Neyman, and Egon Pearson [4]. Their collaborative and independent contributions established key concepts—p-values, hypothesis testing, and confidence intervals—that crystallized into the dominant paradigm for scientific inference across diverse fields [4]. This paradigm is particularly well-suited to controlled experimental settings like randomized clinical trials, where the principles of random sampling and repeatability can be more readily applied. The frequentist framework offers a standardized, objective, and widely accepted methodology for evaluating scientific evidence, making it particularly valuable for regulatory decision-making in drug development where transparency and consistency are paramount [10].

Core Concepts and Methodologies

The Null Hypothesis and P-Values

In frequentist statistics, the null hypothesis (H₀) represents a default position, typically stating that there is no effect, no difference, or that nothing has changed [17]. For example, in a clinical trial comparing a new drug to a standard treatment, the null hypothesis would state that there is no difference in efficacy between the two treatments. The alternative hypothesis (H₁) is the complementary statement, asserting that an effect or difference does exist.

The p-value is a landmark statistical tool used to quantify the evidence against the null hypothesis [18] [19]. Formally, it is defined as the probability of obtaining a test result at least as extreme as the observed one, assuming that the null hypothesis is true [18] [19]. A smaller p-value indicates that the observed data would be unlikely to occur if the null hypothesis were true, thus providing stronger evidence against H₀.

Despite their widespread use, p-values are frequently misinterpreted. It is crucial to understand that:

- The p-value is not the probability that the null hypothesis is true [17]

- It does not measure the size or practical importance of an effect [18]

- It provides no direct evidence for the alternative hypothesis [18]

Table 1: Common Interpretations and Misinterpretations of P-Values

| Correct Interpretation | Common Misinterpretation |

|---|---|

| Probability of obtaining observed data (or more extreme) if H₀ is true | Probability that H₀ is true |

| Measure of incompatibility between data and H₀ | Measure of effect size or importance |

| Evidence against the null hypothesis | Probability of the alternative hypothesis |

One major limitation of p-values is their sensitivity to sample size. In very large samples, even minor and clinically irrelevant effects can yield statistically significant p-values, while in smaller samples, important effects might fail to reach significance [18] [19]. This has led to ongoing debates about the overreliance on arbitrary significance thresholds (such as p < 0.05) and the need for complementary approaches to statistical inference [17].

Confidence Intervals

Confidence intervals provide an alternative approach to inference that addresses some limitations of p-values. A confidence interval provides a range of plausible values for the population parameter, derived from sample data [18]. A 95% confidence interval, for example, means that if the same study were repeated many times, 95% of the calculated intervals would contain the true population parameter [10].

Unlike p-values, which only test against a specific null hypothesis, confidence intervals provide information about both the precision of an estimate (narrower intervals indicate greater precision) and the magnitude of an effect [18]. This makes them particularly valuable for interpreting the practical significance of findings, especially in clinical contexts where the size of a treatment effect is as important as its statistical significance.

Table 2: Comparing P-Values and Confidence Intervals

| Feature | P-Value | Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| What it provides | Probability of observed data assuming H₀ true | Range of plausible parameter values |

| Information about effect size | No direct information | Provides direct information |

| Information about precision | No | Yes (via interval width) |

| Binary interpretation risk | High (significant/not significant) | Lower (continuum of evidence) |

Experimental Protocol: Hypothesis Testing Framework

The frequentist approach to hypothesis testing follows a structured protocol that ensures methodological rigor. The following workflow outlines the standard procedure for conducting null hypothesis significance testing (NHST), which forms the backbone of frequentist statistical analysis in scientific research.

The standard NHST protocol proceeds through these critical stages:

Formulate Hypotheses: Precisely define the null hypothesis (H₀) representing no effect or no difference, and the alternative hypothesis (H₁) representing the effect the researcher seeks to detect [17].

Set Significance Level (α): Before data collection, establish the probability threshold (commonly α = 0.05) for rejecting the null hypothesis. This threshold defines the maximum risk of a Type I error (falsely rejecting a true null hypothesis) the researcher is willing to accept [17].

Calculate Test Statistic and P-Value: Compute the appropriate test statistic (e.g., t-statistic, F-statistic) based on the experimental design and data type. The p-value is then derived from the sampling distribution of this test statistic under the assumption that H₀ is true [18] [17].

Make a Decision: If the p-value ≤ α, reject H₀ in favor of H₁. If the p-value > α, fail to reject H₀. This decision is always made in the context of the pre-specified α level [17].

This structured protocol provides a consistent methodological framework for statistical testing across diverse research domains, ensuring standardized interpretation of results, particularly crucial in regulated environments like drug development.

Frequentist vs. Bayesian Approaches: A Comparative Analysis

Philosophical and Methodological Differences

The frequentist and Bayesian statistical paradigms represent two fundamentally different approaches to inference, probability, and uncertainty. These differences stem from their contrasting interpretations of probability itself. The frequentist approach defines probability as the long-run frequency of an event, while the Bayesian approach treats probability as a subjective degree of belief [10] [4]. This philosophical distinction leads to substantial methodological divergences in how data analysis is performed and interpreted, with important implications for research in fields like drug development.

In frequentist inference, parameters are considered fixed but unknown constants, and probability statements are made about the data given a fixed parameter value. In contrast, Bayesian statistics treats parameters as random variables with associated probability distributions, allowing for direct probability statements about the parameters themselves [4]. This distinction becomes particularly evident in interval estimation: frequentist confidence intervals versus Bayesian credible intervals. A 95% confidence interval means that in repeated sampling, 95% of such intervals would contain the true parameter, whereas a 95% credible interval means there is a 95% probability that the parameter lies within that specific interval, given the observed data [10].

Table 3: Fundamental Differences Between Frequentist and Bayesian Approaches

| Aspect | Frequentist Approach | Bayesian Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Probability Definition | Long-run frequency of events | Degree of belief or uncertainty |

| Parameters | Fixed, unknown constants | Random variables with distributions |

| Inference Basis | Sampling distribution of data | Posterior distribution of parameters |

| Prior Information | Not incorporated formally | Explicitly incorporated via priors |

| Interval Interpretation | Confidence interval: Frequency properties | Credible interval: Direct probability statement |

Practical Implications in Research Settings

The choice between frequentist and Bayesian methods has significant practical implications for research design, analysis, and interpretation. Frequentist methods, with their emphasis on objectivity and standardized procedures, are particularly well-suited for confirmatory research and regulatory settings where predefined hypotheses and strict Type I error control are required [4]. This explains their dominant position in pharmaceutical drug development and clinical trials, where regulatory agencies have established familiar frameworks for evaluation based on frequentist principles.

Bayesian methods offer distinct advantages in certain research contexts, particularly through their ability to incorporate prior knowledge formally into the analysis and provide more intuitive probabilistic interpretations [17] [4]. This makes them valuable for adaptive trial designs, decision-making under uncertainty, and situations with limited data where prior information can strengthen inferences. However, the requirement to specify prior distributions can also introduce subjectivity and potential bias if these priors are poorly justified [18] [4].

Table 4: Performance Comparison in Simulation Studies

| Scenario | Frequentist Behavior | Bayesian Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Large Sample Sizes | Highly sensitive to small, possibly irrelevant effects [18] | Less sensitive to trivial effects; more cautious interpretation [18] |

| Small Sample Sizes | Low power; wide confidence intervals [10] | Can incorporate prior information to improve estimates [4] |

| Effect Size 0.5, N=100 | Often rejects null hypothesis [18] | May show only "barely worth mentioning" evidence for H₁ [18] |

| Sequential Analysis | Requires adjustments for multiple looks | Naturally accommodates continuous monitoring [4] |

Experimental Protocol: The PRACTical Design Case Study

A compelling illustration of both approaches in medical research is the Personalised Randomised Controlled Trial (PRACTical) design, developed for complex clinical scenarios where multiple treatment options exist without a single standard of care. This innovative design was evaluated through comprehensive simulation studies comparing frequentist and Bayesian analytical approaches [20].

The PRACTical design addresses a common challenge in modern medicine: comparing multiple treatments for the same condition when no single standard of care exists. In such scenarios, conventional randomized controlled trials become infeasible because they typically require a common control arm. The PRACTical design enables personalized randomization, where each participant is randomized only among treatments suitable for their specific clinical characteristics, borrowing information across patient subpopulations to rank treatments against each other [20].

The simulation study compared frequentist and Bayesian approaches using a multivariable logistic regression model with the binary outcome of 60-day mortality. The frequentist model included fixed effects for treatments and patient subgroups, while the Bayesian approach utilized strongly informative normal priors based on historical datasets [20]. Performance measures included the probability of predicting the true best treatment and novel metrics for power (probability of interval separation) and Type I error (probability of incorrect interval separation) [20].

Results demonstrated that both frequentist and Bayesian approaches performed similarly in predicting the true best treatment, with both achieving high probabilities (Pbest ≥ 80%) at sufficient sample sizes [20]. Both methods maintained low probabilities of incorrect interval separation (PIIS < 0.05) across sample sizes ranging from 500 to 5000 in null scenarios, indicating appropriate Type I error control [20]. This case study illustrates how both statistical paradigms can be effectively applied to complex trial designs, with each offering distinct advantages depending on the specific research context and available prior information.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Frequentist Analysis

Implementing frequentist statistical analyses requires both conceptual understanding and practical tools. The following "research reagents" represent essential components for conducting rigorous frequentist analyses in scientific research, particularly in drug development.

Table 5: Essential Reagents for Frequentist Statistical Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis Testing Framework | Formal structure for evaluating research questions | Testing superiority of new drug vs. standard care [17] |

| Significance Level (α) | Threshold for decision-making (typically 0.05) | Controlling Type I error rate in clinical trials [17] |

| P-Values | Quantifying evidence against null hypothesis | Determining statistical significance of treatment effect [18] |

| Confidence Intervals | Estimating precision and range of effect sizes | Reporting margin of error for hazard ratios [18] |

| Statistical Software (R, Python, SAS, SPSS) | Implementing analytical procedures | Running t-tests, ANOVA, regression models [21] [22] |

| Power Analysis | Determining required sample size | Ensuring adequate sensitivity to detect clinically meaningful effects [20] |

Modern statistical software packages have made frequentist analyses increasingly accessible. Open-source options like R and Python provide comprehensive capabilities for everything from basic t-tests to complex multivariate analyses [21] [22]. Commercial packages like SAS, SPSS, and Stata offer user-friendly interfaces and specialized modules for specific applications, including clinical trial analysis [21]. These tools enable researchers to implement the statistical methods described throughout this guide, from basic descriptive statistics to advanced inferential techniques.

The frequentist worldview, with its cornerstone concepts of p-values, confidence intervals, and null hypothesis testing, provides a rigorous framework for statistical inference that remains indispensable in scientific research and drug development. Its strengths lie in its objectivity, standardized methodologies, and well-established error control properties, making it particularly valuable for confirmatory research and regulatory decision-making [4]. The structured approach to hypothesis testing ensures consistency and transparency in evaluating scientific evidence, which is crucial when making high-stakes decisions about drug safety and efficacy.

However, the limitations of frequentist methods—particularly the misinterpretation of p-values, sensitivity to sample size, and inability to incorporate prior knowledge—have prompted statisticians to increasingly view Bayesian and frequentist approaches as complementary rather than competing [17] [4]. The optimal choice between these paradigms depends on specific research goals, available data, and decision-making context. Future methodological developments will likely continue to bridge these traditions, offering researchers a more versatile toolkit for tackling complex scientific questions while maintaining the methodological rigor that the frequentist approach provides.

In the landscape of statistical inference, the Bayesian framework offers a probabilistic methodology for updating beliefs in light of new evidence. This approach contrasts with frequentist methods, which interpret probability as the long-run frequency of events and typically rely solely on observed data for inference without incorporating prior knowledge [10]. Bayesian statistics has gained significant traction in fields requiring rigorous uncertainty quantification, particularly in drug development, where it supports more informed decision-making by formally integrating existing knowledge with new trial data [23] [24].

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the core components of the Bayesian framework—priors, likelihoods, and posterior distributions—situated within contemporary research comparing frequentist and Bayesian parameter estimation. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this whitepaper explores the theoretical foundations, practical implementations, and comparative advantages of Bayesian methods through concrete examples and experimental protocols relevant to clinical research.

Core Components of the Bayesian Framework

The Bayesian framework is built upon a recursive process of belief updating, mathematically formalized through Bayes' theorem. This theorem provides the mechanism for combining prior knowledge with observed data to produce updated posterior beliefs about parameters of interest.

Bayes' Theorem: The Foundational Equation

Bayes' theorem defines the relationship between the components of Bayesian analysis. For a parameter of interest θ and observed data X, the theorem is expressed as:

P(θ|X) = [P(X|θ) × P(θ)] / P(X)

where:

- P(θ|X) is the posterior probability of θ given the observed data X

- P(X|θ) is the likelihood function of the data X given the parameter θ

- P(θ) is the prior probability distribution of θ

- P(X) is the marginal probability of the data, serving as a normalizing constant [25]

The posterior distribution P(θ|X) contains the complete updated information about the parameter θ after considering both the prior knowledge and the observed data. In practice, P(X) can be difficult to compute directly but can be obtained through integration (for continuous parameters) or summation (for discrete parameters) over all possible values of θ [25].

The Interplay of Framework Components

The following diagram illustrates the systematic workflow of Bayesian inference, showing how prior knowledge and observed data integrate to form the posterior distribution, which then informs decision-making and can serve as a prior for subsequent analyses.

Comparative Analysis: Bayesian vs. Frequentist Inference

While both statistical paradigms aim to draw inferences from data, their philosophical foundations, interpretation of probability, and output formats differ substantially, leading to distinct advantages in different application contexts.

Philosophical and Methodological Differences

The frequentist approach interprets probability as the long-run frequency of events in repeated trials, treating parameters as fixed but unknown quantities. Inference relies entirely on observed data, with no formal mechanism for incorporating prior knowledge. Common techniques include null hypothesis significance testing, p-values, confidence intervals, and maximum likelihood estimation [10].

In contrast, the Bayesian framework interprets probability as a degree of belief, which evolves as new evidence accumulates. Parameters are treated as random variables with probability distributions that represent uncertainty about their true values. This approach formally incorporates prior knowledge or expert opinion through the prior distribution, with conclusions expressed as probability statements about parameters [25] [10].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Recent research has systematically compared the performance of Bayesian and frequentist methods across various biological modeling scenarios. The table below summarizes key findings from a 2025 study analyzing three different models with varying data richness and observability conditions [26].

Table 1: Performance comparison of Bayesian and frequentist approaches across biological models

| Model | Data Scenario | Best Performing Method | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lotka-Volterra (Predator-Prey) | Both prey and predator observed | Frequentist | Lower MAE and MSE with rich data |

| Generalized Logistic Model (Mpox) | High-quality case data | Frequentist | Superior prediction accuracy |

| SEIUR (COVID-19) | Partially observed latent states | Bayesian | Better 95% PI coverage and WIS |

| PRACTical Trial Design | Multiple treatment patterns | Comparable | Both achieved Pbest ≥80% with strong prior |

The comparative analysis reveals that frequentist inference generally performs better in well-observed settings with rich data, while Bayesian methods excel when latent-state uncertainty is high, data are sparse, or partial observability exists [26]. In complex trial designs like the PRACTical design, which compares multiple treatments without a single standard of care, both approaches can perform similarly in identifying the best treatment, though Bayesian methods offer the advantage of formally incorporating prior information [27].

Application in Drug Development Contexts

Bayesian methods are particularly valuable in drug development, where incorporating prior knowledge can enhance trial efficiency and ethical conduct. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has demonstrated support through initiatives like the Bayesian Statistical Analysis (BSA) Demonstration Project, which aims to increase the use of Bayesian methods in clinical trials [28]. The upcoming FDA draft guidance on Bayesian methodology, expected in September 2025, is anticipated to further clarify regulatory expectations and promote wider adoption [24].

Bayesian approaches are especially beneficial in rare disease research, pediatric extrapolation studies, and scenarios with limited sample sizes, where borrowing strength from historical data or related populations can improve precision and reduce the number of participants required for conclusive results [24].

Experimental Protocol: Bayesian Analysis in Practice

To illustrate the practical implementation of Bayesian analysis, this section details a protocol for estimating the probability of drug effectiveness in a clinical trial setting, adapted from a pharmaceutical industry example [29].

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential computational tools and their functions for Bayesian analysis

| Tool/Software | Function in Analysis | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Python with SciPy/NumPy | Numerical computation and statistical functions | General-purpose Bayesian analysis |

| R with rstanarm package | Bayesian regression modeling | Clinical trial analysis [27] |

| Stan (via R or Python) | Hamiltonian Monte Carlo sampling | Complex Bayesian modeling [26] |

| Probabilistic Programming (PyMC3) | Building and fitting complex hierarchical models | Machine learning applications [10] |

Detailed Methodology

Problem Setup: A pharmaceutical company aims to estimate the probability (θ) that a new drug is effective. Prior studies suggest a 50% chance of effectiveness, and a new clinical trial with 20 patients shows 14 positive responses [29].

Step 1: Define the Prior Distribution

- Select a Beta distribution as the prior for the binomial probability parameter θ

- The Beta distribution is a conjugate prior for the binomial likelihood, ensuring the posterior follows a known distribution

- Encode the prior belief (50% effectiveness) as Beta(α=2, β=2), which is centered at 0.5 with moderate confidence [29]

Step 2: Compute the Likelihood Function

- Model the observed data (14 successes out of 20 trials) using the binomial distribution

- The likelihood function is: P(X|θ) ∝ θ¹⁴ × (1-θ)⁶ [29]

Step 3: Calculate the Posterior Distribution

- Apply Bayes' theorem to compute the posterior distribution

- With a Beta(α, β) prior and binomial likelihood, the posterior follows a Beta(α + k, β + n - k) distribution, where k is the number of successes and n is the sample size

- The resulting posterior is Beta(2 + 14, 2 + 6) = Beta(16, 8) [29]

Step 4: Posterior Analysis and Interpretation

- Compute the posterior mean: αpost/(αpost + βpost) = 16/(16+8) ≈ 0.67

- Calculate the 95% credible interval using the beta distribution's quantile function

- Visualize the prior, likelihood, and posterior distributions to observe the belief updating process [29]

The following diagram illustrates this Bayesian updating process, showing how the prior distribution is updated with observed trial data to form the posterior distribution, which then provides the estimated effectiveness and uncertainty.

Python Implementation Code

This code implements the complete Bayesian analysis, generating visualizations of the prior and posterior distributions and computing key summary statistics including the posterior mean and 95% credible interval [29].

Advanced Bayesian Applications in Clinical Research

Beyond basic parameter estimation, Bayesian methods support sophisticated clinical trial designs and analytical approaches that address complex challenges in drug development.

Innovative Trial Designs

The PRACTical (Personalised Randomised Controlled Trial) design represents an innovative approach for comparing multiple treatments without a single standard of care. This design allows individualised randomisation lists where patients are randomised only among treatments suitable for them, borrowing information across patient subpopulations to rank treatments [27].

Both frequentist and Bayesian approaches can analyze PRACTical designs, with recent research showing comparable performance in identifying the best treatment. However, Bayesian methods offer the advantage of formally incorporating prior information through informative priors, which can be particularly valuable when historical data exists on some treatments [27].

Bayesian Adaptive Designs and Borrowing Methods

Bayesian adaptive designs represent a powerful class of methods that modify trial aspects based on accumulating data while maintaining statistical validity. These approaches are particularly valuable in rare disease research, where traditional trial designs may be impractical due to small patient populations [24].

Key Bayesian borrowing methods include:

- Power Priors: Historical data is incorporated with a discounting factor (power parameter) that controls the degree of borrowing [23]

- Meta-Analytic Predictive Priors: Historical information is synthesized through a random-effects meta-analysis to form an informative prior [24]

- Commensurate Priors: The prior precision is modeled as a function of the similarity between current and historical data [23]

The FDA's Bayesian Statistical Analysis (BSA) Demonstration Project encourages the use of these methods in simple trial settings, providing sponsors with additional support to ensure statistical plans robustly evaluate drug safety and efficacy [28].

The Bayesian framework provides a coherent probabilistic approach to statistical inference that formally integrates prior knowledge with observed data through the systematic application of Bayes' theorem. As demonstrated through the clinical trial example, this methodology offers a transparent mechanism for belief updating, with results expressed as probability statements about parameters of interest.

Comparative research indicates that Bayesian methods particularly excel in scenarios with limited data, high uncertainty, or partial observability, while frequentist approaches remain competitive in well-observed settings with abundant data [26]. In drug development, Bayesian approaches enable more efficient trial designs through formal borrowing of historical information, adaptive trial modifications, and probabilistic interpretation of results [23] [24].

With regulatory agencies like the FDA providing increased guidance and support for Bayesian methods [28], these approaches are poised to play an increasingly important role in clinical research, particularly for rare diseases, pediatric studies, and complex therapeutic areas where traditional trial designs face significant practical challenges. The continued development of computational tools and methodological refinements will further enhance the accessibility and application of Bayesian frameworks across scientific disciplines.

The statistical analysis of data, particularly in high-stakes fields like pharmaceutical research and clinical development, rests upon a fundamental choice: whether to interpret observed data as a random sample drawn from a system with fixed, unknown parameters (the frequentist view) or as fixed evidence that updates our probabilistic beliefs about random parameters (the Bayesian view) [4] [30]. This distinction is not merely philosophical but has profound implications for study design, analysis, interpretation, and decision-making. Frequentist statistics, rooted in the work of Fisher, Neyman, and Pearson, conceptualizes probability as the long-run frequency of events [4] [10]. Parameters, such as a drug's true effect size, are considered fixed constants. Inference relies on tools like p-values and confidence intervals, which describe the behavior of estimators over hypothetical repeated sampling [4]. In contrast, Bayesian statistics, formalized by Bayes, de Finetti, and Savage, treats probability as a degree of belief [4] [10]. Parameters are assigned probability distributions. Prior beliefs (the prior) are updated with observed data via Bayes' Theorem to form a posterior distribution, which fully encapsulates uncertainty about the parameters given the single dataset at hand [10]. This guide delves into the core of this dichotomy, employing analogies to build intuition, summarizing empirical comparisons, and detailing experimental protocols to equip researchers with the knowledge to choose and apply the appropriate paradigm.

Foundational Analogies: The Lighthouse and the Weather Map

To internalize these philosophies, consider two analogies.

The Frequentist Lighthouse: Imagine a lighthouse (the true parameter) on a foggy coast. A ship's captain (the researcher) takes a single bearing on the lighthouse through the fog (collects a dataset). The bearing has measurement error. The frequentist constructs a "confidence interval" around the observed bearing. The correct interpretation is not that there's a 95% chance the lighthouse is within this interval from the ship's current position. Rather, it means that if the captain were to repeat the process of taking a single bearing from different, randomly chosen positions many times, and constructed an interval using the same method each time, 95% of those intervals would contain the fixed lighthouse. The uncertainty is in the measurement process, not the lighthouse's location [4] [30].

The Bayesian Weather Map: Now consider forecasting tomorrow's temperature. Meteorologists start with a prior forecast based on historical data and current models (the prior distribution). Throughout the day, they incorporate new, fixed evidence: real-time readings from weather stations (likelihood). They continuously update the forecast, producing a new probability map (posterior distribution) showing the most likely temperatures and the uncertainty around them. One can say, "There is a 90% probability the temperature will be between 68°F and 72°F." The uncertainty is directly quantified in the parameter (tomorrow's temperature) itself, conditioned on all available evidence [10] [31].

These analogies highlight the core difference: frequentism reasons about data variability under a fixed truth, while Bayesianism reasons about parameter uncertainty given fixed data.

Quantitative Comparison in Research Contexts

Empirical studies directly comparing both approaches in biomedical settings reveal their practical trade-offs. The following tables synthesize key quantitative findings from network meta-analyses and personalized trial designs.

Table 1: Performance in Treatment Ranking (Multiple Treatment Comparisons & PRACTical Design)

| Metric | Frequentist Approach | Bayesian Approach | Context & Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability of Identifying True Best Treatment | Comparable to Bayesian with sufficient data. In PRACTical simulations, P_best ≥80% at N=500 [20]. | Can achieve high probability (>80%) even with smaller N, especially with informative priors [32] [20]. | Simulation of personalized RCT (PRACTical) for antibiotic ranking [20]. |

| Type I Error Control (Incorrect Interval Separation) | Strictly controlled by design (e.g., α=0.05). PRACTical simulations showed P_IIS <0.05 for all sample sizes [20]. | Controlled by the posterior. With appropriate priors, similar control is achieved (P_IIS <0.05) [20]. | Same PRACTical simulation study [20]. |

| Handling Zero-Event Study Arms | Problematic. Requires data augmentation (e.g., adding 0.5 events) or exclusion, potentially harming approximations [32]. | Feasible and natural. No need for ad-hoc corrections; handled within the probabilistic model [32]. | Case study in urinary incontinence (UI) network meta-analysis [32]. |

| Estimation of Between-Study Heterogeneity (σ) | Tends to produce smaller estimates, sometimes close to zero [32]. | Typically yields larger, more conservative estimates of random-effect variability [32]. | UI network meta-analysis [32]. |

| Interpretation of Results | Provides point estimates (e.g., log odds ratios) with confidence intervals. Cannot directly compute the probability that a treatment is best [32]. | Provides direct probability statements (e.g., Probability of being best, Pr(Best12)). More intuitive for decision-making [32] [20]. | UI network meta-analysis & PRACTical design [32] [20]. |

Table 2: Computational & Informational Characteristics

| Aspect | Frequentist Approach | Bayesian Approach | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prior Information | Not incorporated formally. Analysis is objectively based on current data alone [4] [10]. | Core component. Can use non-informative, weakly informative, or strongly informative priors to incorporate historical data or expert opinion [32] [4] [20]. | Priors are a key advantage but also a source of debate regarding subjectivity [4]. |

| Computational Demand | Generally lower. Relies on maximum likelihood estimation and closed-form solutions [10]. | Generally higher, especially for complex models. Relies on Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling for posterior approximation [4] [10]. | Advances in software (Stan, PyMC3) have improved accessibility [4] [10]. |

| Output | Point estimates, confidence intervals, p-values. | Full posterior distribution for all parameters. Can derive any summary (mean, median, credible intervals, probabilities) [10]. | Posterior distribution is a rich source of inference. |

| Adaptivity & Sequential Analysis | Problematic without pre-specified adjustment (alpha-spending functions). Prone to inflated false-positive rates with peeking [4]. | Inherently adaptable. Posterior from one stage becomes the prior for the next, ideal for adaptive trial designs and continuous monitoring [4] [31]. | Key for Bayesian adaptive trials and real-time analytics. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To illustrate how these paradigms are implemented, we detail methodologies from two pivotal studies cited in the search results.

Protocol 1: Frequentist vs. Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis (NMA) for Urinary Incontinence Drugs

This protocol is based on the case study comparing methodologies for multiple treatment comparisons [32].

- Objective: To compare the efficacy and safety of multiple pharmacologic treatments for urgency urinary incontinence (UI) using both frequentist and Bayesian NMA.

- Data Source: Aggregate data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing any of the active drugs or placebo. Outcomes were binary: achievement of continence and discontinuation due to adverse events (AE).

- Model Specification:

- Common Model: Both approaches used random-effects models to account for between-study heterogeneity, assuming treatment effects follow a normal distribution.

- Frequentist Implementation: Executed in Stata using maximum likelihood estimation. For studies with zero events in an arm, the dataset was manipulated by adding a small number of artificial individuals (0.01) and successes (0.001) to enable model fitting. Inconsistency (disagreement between direct and indirect evidence) was assessed via a cross-validation method.

- Bayesian Implementation: Conducted using MCMC sampling (e.g., in WinBUGS or similar). Non-informative or shrinkage priors were used for treatment effects and heterogeneity parameters. Zero-event cells were handled naturally within the binomial likelihood model. Inconsistency was quantified statistically using w-factors.

- Key Outputs & Analysis:

- Frequentist: Log odds ratios (LORs) with 95% confidence intervals for all treatment comparisons versus a reference (e.g., placebo). Statistical significance was assessed via CIs.

- Bayesian: Posterior distributions for LORs. Derived probabilities:

Pr(Best)(probability a treatment is the most efficacious/safest) andPr(Best12)(probability of being among the top two). - Comparison: Focus on concordance in LOR point estimates, differences in heterogeneity (σ) estimates, and the added value of ranking probabilities (

Pr(Best12)) for clinical decision-making.

Protocol 2: Simulation of a Personalized RCT (PRACTical) for Antibiotic Ranking

This protocol is based on the 2025 simulation study comparing analysis approaches for the PRACTical design [20].

- Objective: To evaluate frequentist and Bayesian methods for ranking the efficacy of four targeted antibiotic treatments (A, B, C, D) for multidrug-resistant bloodstream infections within a PRACTical design.

- Data Generation (Simulation):

- Define four patient subgroups based on eligibility (e.g., due to allergies or bacterial resistance). Each subgroup has a personalized randomisation list (pattern) of 2-3 eligible treatments.

- Simulate patient enrollment: Assign each of N total patients (N ranging from 500 to 5000) to a subgroup and site (10 sites) using multinomial distributions.

- Simulate binary outcome (60-day mortality): For a patient in subgroup k on treatment j, generate mortality from a Bernoulli distribution with probability P_jk. True treatment effects (log odds ratios) are pre-specified.

- Analysis Models:

- Frequentist Logistic Regression: A fixed-effects logistic regression model implemented in R (

statspackage). Model:logit(P_jk) = β_subgroup_k + ψ_treatment_j. Treatments and subgroups are categorical fixed effects. - Bayesian Logistic Regression: A similar model implemented via

rstanarmin R. Three different sets of strongly informative normal priors are tested for the seven coefficients (4 treatment + 3 subgroup):- Prior 1: Derived from a representative historical dataset.

- Prior 2 & 3: Derived from unrepresentative historical datasets.

- Frequentist Logistic Regression: A fixed-effects logistic regression model implemented in R (

- Performance Evaluation:

- Pbest: Proportion of simulation runs where the treatment with the best estimated coefficient (highest posterior mean for Bayesian, lowest mortality estimate for frequentist) is the true best treatment.

- Probability of Interval Separation (PIS): A novel power proxy. Proportion of runs where the 95% CI (frequentist) or credible interval (Bayesian) of the best treatment does not overlap with the CI of the true worst treatment.

- Probability of Incorrect Interval Separation (P_IIS): A novel Type I error proxy. Proportion of runs under a null scenario (all treatments equal) where such separation occurs.

Visualizing the Workflows and Conceptual Frameworks

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the logical flow of each statistical paradigm and a key experimental design.

Diagram 1: Conceptual Flow of Frequentist vs. Bayesian Inference (76 chars)

Diagram 2: PRACTical Trial Design & Analysis Workflow (77 chars)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

This table details key methodological "reagents" essential for conducting comparative analyses between frequentist and Bayesian paradigms, particularly in pharmacological research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Comparative Statistical Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R/Python) | Provides environments for implementing both frequentist and Bayesian models. Essential for simulation and analysis. | R: metafor (freq. NMA), netmeta, gemtc (Bayesian NMA), rstanarm, brms (Bayesian models). Python: PyMC, Stan (via pystan), statsmodels (frequentist) [4] [10]. |

| Priors (Bayesian) | Encode pre-existing knowledge or skepticism about parameters before seeing trial data. | Non-informative/Vague: Minimally influences posterior (e.g., diffuse Normal). Weakly Informative: Regularizes estimates (e.g., Cauchy, hierarchical shrinkage priors). Strongly Informative: Based on historical data/meta-analysis, as used in PRACTical study [32] [20]. |

| MCMC Samplers (Bayesian) | Computational engines for approximating posterior distributions when analytical solutions are impossible. | Algorithms like Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) and No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS), implemented in Stan, are standard for complex models [4] [10]. |

| Random-Effects Model Structures | Account for heterogeneity between studies (in NMA) or clusters (in trials). A point of comparison between paradigms. | Specifying the distribution of random effects (e.g., normal) and estimating its variance (τ² or σ²). Bayesian methods often estimate this more readily [32]. |

| Performance Metric Suites | Quantitatively compare the operating characteristics of different analytical approaches. | For Ranking: Probability of correct selection (PCS), Pr(Best). For Error Control: Type I error rate, P_IIS. For Precision: Width of CIs/Credible Intervals, P_IS [20]. |

| Network Meta-Analysis Frameworks | Standardize the process of comparing multiple treatments via direct and indirect evidence. | Frameworks define consistency assumptions, model formats (fixed/random effects), and inconsistency checks, applicable in both paradigms [32] [20]. |

| Simulation Code Templates | Enable the generation of synthetic datasets with known truth to validate and compare methods. | Crucial for studies like the PRACTical evaluation. Code should modularize data generation, model fitting, and metric calculation for reproducibility [20]. |

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Methods in Clinical and Biomedical Research

Frequentist statistics form the cornerstone of statistical inference used widely across scientific disciplines, including drug development and biomedical research. This approach treats parameters as fixed, unknown quantities and uses sample data to draw conclusions based on long-run frequency properties [33]. Within this framework, three methodologies stand out for their pervasive utility: t-tests, Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), and Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE). These tools provide the fundamental machinery for hypothesis testing and parameter estimation in situations where Bayesian prior information is either unavailable or intentionally excluded from analysis.

The ongoing discourse between frequentist and Bayesian paradigms centers on their philosophical foundations and practical implications for scientific inference [17]. While Bayesian methods increasingly offer attractive alternatives, particularly with complex models or when incorporating prior knowledge, the conceptual clarity and well-established protocols of frequentist methods ensure their continued dominance in many application areas. This technical guide examines these core frequentist methods, detailing their theoretical underpinnings, implementation protocols, and appropriate application contexts to equip researchers with a solid foundation for their analytical needs.

Maximum Likelihood Estimation: Theoretical Foundations

Core Principles and Mathematical Formulation

Maximum Likelihood Estimation is a powerful parameter estimation technique that seeks the parameter values that maximize the probability of observing the obtained data [34]. The method begins by constructing a likelihood function, which represents the joint probability of the observed data as a function of the unknown parameters.

For a random sample (X1, X2, \cdots, X_n) with a probability distribution depending on an unknown parameter (\theta), the likelihood function is defined as:

[ L(\theta)=P(X1=x1,X2=x2,\ldots,Xn=xn)=f(x1;\theta)\cdot f(x2;\theta)\cdots f(xn;\theta)=\prod\limits{i=1}^n f(x_i;\theta) ]

In practice, we often work with the log-likelihood function because it transforms the product of terms into a sum, simplifying differentiation:

[ \log L(\theta)=\sum\limits{i=1}^n \log f(xi;\theta) ]

The maximum likelihood estimator (\hat{\theta}) is found by solving the score function (the derivative of the log-likelihood) set to zero:

[ \frac{\partial \log L(\theta)}{\partial \theta} = 0 ]

Implementation and Inference

The implementation of MLE typically involves numerical optimization techniques to find the parameter values that maximize the likelihood function. Once the MLE is obtained, its statistical properties can be examined through several established approaches:

- Likelihood Ratio Test: For comparing nested models, the LR test statistic is (LR = -2\log(\text{L at } H_0/\text{L at MLE})) and follows a chi-square distribution under the null hypothesis [35]

- Wald Test: Uses the approximation (W = \frac{(\hat{\theta} - \theta_0)^2}{Var(\hat{\theta})}) for testing hypotheses about parameters

- Score Test: Based on the slope of the log-likelihood at the null hypothesis value

For confidence interval construction, Wald-based intervals are most common ((\hat{\theta} \pm z_{1-\alpha/2}SE(\hat{\theta}))), though profile likelihood intervals often provide better coverage properties, particularly for small samples [35].

Table 1: Comparison of MLE Hypothesis Testing Approaches

| Test Method | Formula | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Likelihood Ratio | (-2\log(L{H0}/L_{MLE})) | Most accurate for small samples | Requires fitting both models |

| Wald | (\frac{(\hat{\theta}-\theta_0)^2}{Var(\hat{\theta})}) | Only requires MLE | Sensitive to parameterization |

| Score | (\frac{U(\theta0)}{I(\theta0)}) | Does not require MLE | Less accurate for small samples |

Model Selection and Penalized Likelihood

When comparing models of different complexity, information criteria provide a framework for balancing goodness-of-fit against model complexity:

- Akaike Information Criterion (AIC): (AIC = -2\log L + 2p)

- Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC): (BIC = -2\log L + p\log n)

Where (p) represents the number of parameters and (n) the sample size. As noted in research, "AIC has a lower probability of correct model selection in linear regression settings" compared to BIC in some contexts [35].

For situations requiring parameter shrinkage to improve prediction or handle collinearity, penalized likelihood methods add a constraint term to the optimization:

[ \log L - \frac{1}{2}\lambda\sum{i=1}^p(si\theta_i)^2 ]

Where (\lambda) controls the degree of shrinkage and (s_i) are scale factors [35].

T-Tests: Methodology and Applications

Historical Context and Assumptions

The t-test was developed by William Sealy Gosset in 1908 while working at the Guinness Brewery in Dublin [36]. Published under the pseudonym "Student," this test addressed the need for comparing means when working with small sample sizes where the normal distribution was inadequate.

The t-test relies on several key assumptions:

- The data are continuous and approximately normally distributed

- Observations are independent

- For two-sample tests, homogeneity of variance between groups

The test statistic follows the form:

[ t = \frac{\text{estimate} - \text{hypothesized value}}{\text{standard error of estimate}} ]

Which follows a t-distribution with degrees of freedom dependent on the sample size and test type.

T-Test Variants and Implementation

The three primary variants of the t-test each address distinct experimental designs:

- One-sample t-test: Compares a sample mean to a known population value

- Independent samples t-test: Compares means between two unrelated groups

- Paired t-test: Compares means within the same subjects under different conditions

The decision framework for selecting the appropriate t-test can be visualized as follows: