fMRI Preprocessing for Autism Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive guide to functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) data preprocessing for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) analysis, tailored for researchers and biomedical professionals.

fMRI Preprocessing for Autism Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) data preprocessing for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) analysis, tailored for researchers and biomedical professionals. It covers the foundational principles of fMRI and its link to ASD neurobiology, explores established and cutting-edge preprocessing methodologies, addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges for real-world data, and outlines rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing current literature and benchmarks, this guide aims to equip readers with the knowledge to build robust, reproducible, and clinically informative preprocessing pipelines for ASD biomarker discovery and diagnostic tool development.

Understanding fMRI Fundamentals and Their Role in Autism Neurobiology

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the BOLD signal and what does it measure?

The Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) signal is the primary contrast mechanism used in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). It detects local changes in brain blood flow and blood oxygenation that are coupled to underlying neuronal activity, a process termed neurovascular coupling [1] [2].

The BOLD signal arises from the different magnetic properties of hemoglobin:

- Oxyhemoglobin: Diamagnetic - has little effect on the MRI signal.

- Deoxyhemoglobin: Paramagnetic - causes local dephasing of spinning proton dipoles and shortens the T2* relaxation time, reducing the MRI signal [3] [2].

When brain regions become metabolically active, the resulting hemodynamic response brings in oxygenated blood in excess of what is immediately consumed. This leads to a local decrease in deoxyhemoglobin concentration, which reduces the signal dephasing and results in a positive BOLD signal—an increase in the T2*-weighted MRI signal typically ranging from 2% at 1.5 Tesla to about 12% at 7 Tesla scanners [1] [3].

What is the typical time course of the BOLD response?

The hemodynamic response to a brief neural event is characterized by a predictable pattern known as the Hemodynamic Response Function (HRF), with the following temporal characteristics [1] [2]:

Table 1: Temporal Characteristics of the BOLD Hemodynamic Response

| Response Phase | Time Post-Stimulus | Physiological Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | ~500 ms | Initial neuronal activity triggering neurovascular coupling |

| Initial Dip (sometimes observed) | 1-2 s | Possible early oxygen consumption before blood flow increase |

| Positive Peak | 3-5 s | Marked increase in cerebral blood flow exceeding oxygen demand |

| Post-Stimulus Undershoot | After stimulus cessation | Proposed mechanisms include prolonged oxygen metabolism or vascular compliance |

For prolonged stimuli, the BOLD response typically shows a peak-plateau pattern where the initial peak is followed by a sustained elevated signal until stimulus cessation [1].

What are the key vascular changes during functional hyperemia?

Functional hyperemia involves coordinated changes across the vascular tree, summarized in the table below [1]:

Table 2: Vascular Components of Functional Hyperemia

| Vascular Compartment | Observed Changes During Activation | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Capillaries | Physical expansion; early parenchymal HbT increase | May explain early CBV changes and "initial dip" |

| Arterioles/Pial Arteries | Dilation with potential retrograde propagation | Decreases resistance to increase blood flow |

| Veins | Increased blood flow velocity with minimal diameter change | Drains oxygenated blood from active regions |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

How can I address head motion artifacts in fMRI data?

Head motion is the largest source of error in fMRI studies, particularly challenging in clinical populations such as individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) [4] [5]. The following table outlines prevention and correction strategies:

Table 3: Motion Artifact Mitigation Strategies

| Approach | Specific Techniques | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Preventive | Head padding and straps; subject coaching; bite bars (rarely) | Essential for populations with potential movement challenges |

| Prospective Correction | Navigator echoes; real-time motion tracking | Implemented during data acquisition |

| Retrospective Correction | Rigid-body realignment (6 parameters: 3 translation, 3 rotation); regression of motion parameters | Standard approach; may not correct non-linear effects or spin-history effects |

| Data Scrubbing | Framewise displacement (FD) filtering; removal of outlier volumes | Filtering at FD > 0.2 mm shown to increase classification accuracy in ASD studies from 91% to 98.2% [6] |

What preprocessing steps are essential for fMRI analysis?

A standard fMRI preprocessing pipeline includes multiple steps to prepare data for statistical analysis, with particular importance for resting-state fMRI and clinical applications [7] [4]:

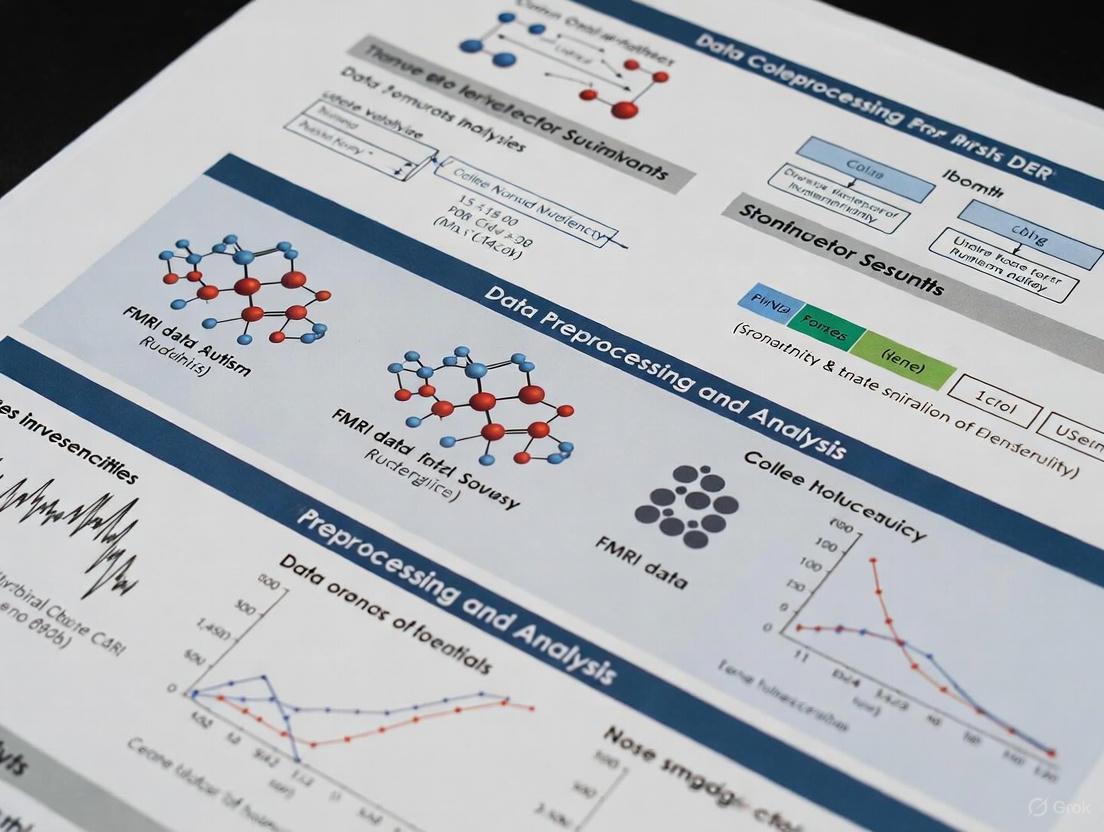

Figure 1: fMRI Preprocessing Workflow

Critical Preprocessing Steps:

Quality Assurance & Artifact Detection: Visual inspection of source images to identify aberrant slices; use of framewise displacement metrics to quantify head motion [4] [6].

Slice Timing Correction: Accounts for acquisition time differences between slices, particularly important for event-related designs. Can be implemented via data shifting or model shifting approaches [4].

Motion Correction: Realignment of all volumes to a reference volume using rigid-body transformation. Should include visual inspection of translation/rotation parameters [4].

Spatial Normalization: Alignment of individual brains to a standard template space (e.g., MNI space). Particularly challenging for clinical populations with structural abnormalities [7] [5].

Spatial Smoothing: Averaging of signals from adjacent voxels using a Gaussian kernel (typically 4-8 mm FWHM) to improve signal-to-noise ratio at the cost of spatial resolution [4].

Temporal Filtering: Removal of low-frequency drifts (high-pass filtering) and sometimes high-frequency noise (low-pass filtering) [4].

How can I clean noise from resting-state fMRI data?

Resting-state fMRI presents unique challenges for noise removal due to the absence of task timing information. Independent Component Analysis (ICA) has become a cornerstone technique for this purpose [7].

ICA-Based Cleaning Protocol:

Single-Subject ICA: Decomposes the 4D fMRI data into independent spatial components and their associated time courses using tools like FSL's MELODIC [7].

Component Classification: Each component is classified as either "signal" (neural origin) or "noise" (artifactual origin) based on its spatial map, time course, and frequency spectrum. For large datasets, FMRIB's ICA-based Xnoiseifier (FIX) provides automated classification, but may require training on hand-labeled data from your specific study [7].

Noise Regression: The variance associated with noise components is regressed out of the original data, producing a cleaned dataset [7].

What are special considerations for fMRI in autism research?

fMRI studies in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) present unique methodological challenges and considerations that impact experimental design and interpretation [8] [6] [5]:

Key Considerations for ASD fMRI Studies:

Heterogeneity: ASD encompasses diverse neurobiological etiologies, leading to substantial inter-individual variability in functional connectivity patterns. This "idiosyncratic brain" concept complicates the search for universal biomarkers and necessitates large sample sizes [8] [6].

Cognitive and Behavioral Factors: Individuals with ASD may exhibit differences in attention, processing speed, sensory sensitivity, and anxiety that can confound fMRI measurements. These factors must be considered in task design and interpretation [5].

Comorbidities: Common co-occurring conditions (e.g., epilepsy, intellectual disability, ADHD) and medications may independently affect BOLD signals [5].

Validated Biomarkers: Emerging research has consistently highlighted visual processing regions (calcarine sulcus, cuneus) as critical for classifying ASD, with genetic studies confirming abnormalities in Brodmann Area 17 (primary visual cortex) [6]. Altered reward processing, characterized by striatal hypoactivation in both social and non-social contexts, also represents a replicated finding [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for fMRI Research with Clinical Populations

| Item/Category | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ABIDE Datasets (ABIDE I & II) | Pre-existing, large-scale repositories of resting-state fMRI and structural data from individuals with ASD and typical controls | Aggregates data from >2000 individuals across international sites; reduces data collection burden [8] [6] |

| CRS-R (Coma Recovery Scale-Revised) | Standardized behavioral assessment for disorders of consciousness | Critical for proper patient characterization and avoiding misdiagnosis in relevant populations [5] |

| FIX (FMRIB's ICA-based Xnoiseifier) | Automated classifier for identifying noise components in ICA results | Requires training on hand-labeled data if study parameters differ from existing training sets [7] |

| Physiological Monitoring Equipment | Records cardiac and respiratory cycles | Allows for modeling and removal of physiological noise from BOLD signals |

| Standardized fMRI Paradigms | Experiment protocols for language, motor, and other cognitive functions | ASFNR-recommended algorithms available for presurgical mapping; important for clinical comparability [3] |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

This section addresses common challenges researchers face when linking functional connectivity (FC) findings to autism spectrum disorder (ASD) pathophysiology.

Table 1: Frequently Asked Questions and Technical Solutions

| Question | Issue | Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Are observed FC differences neural or motion artifacts? | Head movement introduces spurious correlations, confounding true biological signals. | Implement rigorous framewise displacement (FD) filtering (e.g., FD > 0.2 mm). Use denoising pipelines (e.g., CONN) with scrubbing, motion regression, and CompCor. | [6] |

| How to reconcile reports of both hyper- and hypo-connectivity? | The literature shows conflicting patterns, making pathophysiological interpretation difficult. | Adopt a mesoscopic, network-based approach. Analyze specific subnetworks rather than whole-brain means. Account for age and heterogeneity. | [10] [11] |

| Can we trust "black box" machine learning models? | High-accuracy models may lack interpretability, hindering clinical adoption and biological insight. | Use explainable AI (XAI) methods like Integrated Gradients. Systematically benchmark interpretability methods with ROAR. Validate findings against genetic/neurobiological literature. | [6] |

| My findings don't generalize across datasets. Why? | Idiosyncratic functional connectivity patterns lead to poor reproducibility. | Leverage large, multi-site datasets (e.g., ABIDE). Use cross-validation across sites. Test findings against multiple preprocessing pipelines. | [6] [11] |

| How to handle extreme heterogeneity in ASD? | Individuals with ASD show vast genetic and phenotypic variability, complicating group-level analyses. | Explore subgrouping by biological features (e.g., genotype). Use methods that capture individual-level patterns. Study genetically defined subgroups (e.g., FXS). | [12] [13] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Extracting Contrast Subgraphs to Identify Altered Connectivity

This protocol outlines a method for identifying mesoscopic-scale connectivity patterns that maximally differ between ASD and control groups [11].

Workflow Overview

Detailed Methodology

- Input Data: Start with preprocessed resting-state fMRI (rsfMRI) data from both typically developing (TD) and ASD participants. Ensure groups are matched for age and sex [11].

- Functional Connectivity Matrices: For each participant, compute a functional connectivity matrix using Pearson's correlation coefficient between the time series of all Region of Interest (ROI) pairs [11].

- Network Sparsification: Apply the SCOLA algorithm or a similar sparsification method to individual FC matrices. Aim for a network density of typically less than 0.1 to focus on the strongest connections and reduce noise [11].

- Summary Graphs: Create a single summary graph for the TD cohort and another for the ASD cohort. This compresses the common features of each group's networks into one representative graph [11].

- Difference Graph: Generate a difference graph where the weight of each edge equals the corresponding weight in the TD summary graph minus the weight in the ASD summary graph [11].

- Optimization: Solve an optimization problem on the difference graph to find the contrast subgraph—the set of ROIs that maximizes the difference in connectivity (density) between the two groups [11].

- Validation: Use bootstrapping on equally sized group samples to create a family of candidate contrast subgraphs. Apply statistical validation (e.g., a U-Test with p < 0.05) and techniques from Frequent Itemset Mining to identify a robust, statistically significant final contrast subgraph [11].

Protocol 2: Explainable Deep Learning for ASD Classification

This protocol describes how to train an interpretable deep learning model to classify ASD using rsfMRI data, ensuring the model reveals biologically plausible biomarkers [6].

Workflow Overview

Detailed Methodology

- Data: Use a large, publicly available dataset like ABIDE I, which includes 408 individuals with ASD and 476 typically developing controls. Ensure the dataset spans multiple international sites to enhance generalizability [6].

- Preprocessing: Implement strict motion correction, including mean framewise displacement (FD) filtering with a threshold of >0.2 mm. This step is critical, as it can increase classification accuracy significantly (e.g., from 91% to 98.2%) [6].

- Model Architecture: Employ a Stacked Sparse Autoencoder (SSAE) for unsupervised feature learning from functional connectivity data, followed by a softmax classifier for supervised fine-tuning and classification [6].

- Interpretability: Systematically apply multiple interpretability methods (e.g., Integrated Gradients, Grad-CAM) to the trained model to identify which functional connections most strongly drive the classification decision [6].

- Benchmarking: Use the Remove And Retrain (ROAR) framework to objectively benchmark interpretability methods. This involves removing top-ranked features, retraining the model, and observing the performance drop to gauge the true importance of the features [6].

- Validation: Crucially, validate the model-identified biomarkers against independent neuroscientific literature from genetic, neuroanatomical, and functional studies. This confirms that the model captures genuine neurobiological markers of ASD and not just dataset-specific artifacts [6].

Signaling Pathways and Convergent Mechanisms

ASD's extreme heterogeneity is underpinned by a convergence onto shared pathological pathways and functional networks.

Table 2: Key Signaling Pathways and Functional Networks in ASD Pathophysiology

| Pathway/Network | Biological Function | Alteration in ASD | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| mTOR Signaling | Regulates cell growth, protein synthesis, synaptic plasticity. | Overactivated; leads to altered synaptic development and function. | Inhibitors (e.g., rapamycin) reverse deficits in models like TSC and FXS. [14] |

| mGluR Signaling | Controls metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity. | Dysregulated; implicated in fragile X syndrome. | mGluR5 antagonists show therapeutic potential in FXS models. [14] |

| Default Mode Network (DMN) | Supports self-referential thought, social cognition. | Widespread under-connectivity, especially in idiopathic ASD. | Decreased FC within DMN and with other networks (e.g., cerebellum). [13] |

| Cerebellum Network (CN) | Involved in motor coordination, cognitive function, prediction. | Topological alterations; decreased FC with DMN, SMN, VN. | Shared aberration in FXS and idiopathic ASD; correlates with social affect. [13] |

| Visual Network (VN) | Processes visual information and perception. | Local hyper-connectivity; identified as a key biomarker. | Consistently highlighted by interpretable AI and contrast subgraph analysis. [6] [11] |

Logical Relationships of Convergent Pathophysiology The following diagram integrates genetic risk, molecular pathways, and network-level dysfunction into a coherent model of ASD pathophysiology.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for fMRI ASD Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features / Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| CONN Toolbox [15] | Software | fMRI connectivity processing & analysis | Integrated preprocessing, denoising, and multiple analysis methods (SBC, RRC, gPPI, ICA). Enhances reproducibility. |

| Connectome Workbench [16] | Software | Visualization & discovery | Maps neuroimaging data to surfaces and volumes; crucial for HCP-style data visualization and analysis. |

| ABIDE Database [10] [6] | Data | Preprocessed rsfMRI datasets | Aggregated data from multiple international sites; enables large-scale analysis and validation (ABIDE I & II). |

| DPABI / SPM / FSL [13] | Software | Data preprocessing | Standard pipelines for image normalization, smoothing, and statistical analysis. DPABI is common in rsFC studies. |

| Brain Connectivity Toolbox (BCT) [13] | Software | Network analysis | Computes graph theory metrics (nodal degree, efficiency) to quantify network topology. |

| SFARI Gene Database [12] | Database | Genetic resource | Curated list of ASD-associated risk genes; used for gene set enrichment and pathway analysis (e.g., GO analysis). |

The Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE) is a grassroots initiative that has successfully aggregated and openly shared functional and structural brain imaging data from laboratories across the globe [17]. Its primary goal is to accelerate the pace of discovery in understanding the neural bases of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) by providing large-scale datasets that single laboratories would be unable to collect independently [17] [18].

The repository is a core component of the International Neuroimaging Data-sharing Initiative (INDI) [19]. To date, ABIDE comprises two large-scale collections, ABIDE I and ABIDE II, which together provide researchers with a vast resource of neuroimaging data from individuals with ASD and typical controls.

The table below summarizes the key specifications of the two ABIDE releases.

| Feature | ABIDE I | ABIDE II |

|---|---|---|

| Total Datasets | 1,112 [19] [18] | 1,044 [20] |

| ASD / Control Split | 539 ASD / 573 Typical Controls [19] [18] | 487 ASD / 557 Typical Controls [20] |

| Combined Sample (I + II) | 2,156 unique cross-sectional datasets [20] | |

| Data Types | R-fMRI, structural MRI, phenotypic [19] | R-fMRI, structural MRI, phenotypic, some diffusion imaging (N=284) [20] |

| Number of Sites | 17 international sites [19] | 16 international sites [20] |

| Primary Goal | Demonstrate feasibility of data aggregation and provide initial large-scale resource [19] [18] | Enhance scope, address heterogeneity, provide larger samples for replication/subgrouping [20] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary data usage terms for ABIDE? Consistent with the policies of the 1000 Functional Connectomes Project, data usage is unrestricted for non-commercial research purposes [19]. Users are required to register with the Neuroimaging Informatics Tools and Resources Clearinghouse (NITRC) and the International Neuroimaging Data-sharing Initiative (INDI) to gain access. The data is provided under a Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike license [19].

Q2: I'm new to this dataset. Is there a preprocessed version of ABIDE available? Yes. The Preprocessed Connectomes Project (PCP) offers a publicly available, preprocessed version of the ABIDE data [21]. A key strength of this resource is that the data was preprocessed by several different teams (e.g., using CCS, CPAC, DPARSF, NIAK) employing various preprocessing strategies. This allows researchers to test the robustness of their findings across different preprocessing pipelines [21].

Q3: What are some common applications of ABIDE data in research? ABIDE data is extensively used in machine learning (ML) studies aiming to classify individuals with ASD versus typical controls. A 2022 systematic review found that Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) were the most commonly applied classifiers, with summary sensitivity and specificity estimates across studies around 74-75% [8]. The data is also used for discovery science, such as identifying brain regions and networks associated with ASD, including the default mode network, salience network, and visual processing regions [18] [6].

Q4: What kind of phenotypic information is included? The "base" phenotypic protocol includes information such as age at scan, sex, IQ, and diagnostic details [18]. ABIDE II enhanced phenotypic characterization by encouraging contributors to provide information on co-occurring psychopathology, medication status, and other cognitive or language measures to help address key sources of heterogeneity in ASD [20].

Q5: What is the typical workflow for a research project using ABIDE? The diagram below outlines the key stages of a neuroimaging research project utilizing the ABIDE repository.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Pipelines

When working with ABIDE data, researchers rely on a suite of software pipelines and analytical tools. The table below details some of the most critical "research reagents" in this field.

| Tool / Pipeline Name | Type / Category | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Configurable Pipeline for the Analysis of Connectomes (C-PAC) [22] [21] | Functional Preprocessing Pipeline | Automated preprocessing of resting-state fMRI data (e.g., motion correction, registration, nuisance regression). |

| Data Processing Assistant for Resting-State fMRI (DPARSF) [21] | Functional Preprocessing Pipeline | A user-friendly pipeline based on SPM and REST toolkits for rs-fMRI data processing. |

| Connectome Computation System (CCS) [21] | Functional Preprocessing Pipeline | A comprehensive pipeline for multimodal brain connectome computation. |

| NeuroImaging Analysis Kit (NIAK) [21] | Functional Preprocessing Pipeline | A flexible pipeline for large-scale fMRI data analysis. |

| ANTs [21] | Structural Preprocessing Pipeline | Used for advanced anatomical segmentation and registration (e.g., to MNI space). |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) [23] [8] | Machine Learning Classifier | A classic algorithm frequently used for classifying ASD vs. controls based on neuroimaging features. |

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) / Deep Learning [8] [6] | Machine Learning Classifier | Used to identify complex, non-linear patterns in functional connectivity data for classification. |

| Integrated Gradients [6] | Explainable AI (XAI) Method | An interpretability method identified as highly reliable for highlighting discriminative brain features in fMRI models. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: A Standardized ML Classification Analysis Using ABIDE This is a common framework used in many studies that seek to develop a diagnostic classifier for ASD [23] [8].

- Data Selection: Choose a specific ABIDE release (I, II, or combined) and select participating sites based on inclusion criteria (e.g., age range, data quality).

- Feature Extraction: From the preprocessed R-fMRI data, calculate whole-brain functional connectivity (FC) matrices. This is often done by defining Regions of Interest (ROIs) using a brain atlas and computing correlation coefficients between the time series of all region pairs.

- Feature Selection: Apply dimensionality reduction techniques (e.g., Principal Component Analysis, Recursive Feature Elimination) to manage the high dimensionality of FC matrices and select the most discriminative features.

- Model Training & Testing: Split the data into training and testing sets. Train a classifier (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) on the training set and evaluate its performance on the held-out test set using metrics like accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity.

- Validation: Critically, validate findings using independent samples or through cross-validation across different ABIDE sites to ensure generalizability.

Protocol 2: A Discovery Science Analysis of Intrinsic Functional Architecture This protocol is used to explore fundamental neural connectivity differences in ASD without a specific classification goal [18].

- Preprocessing: Preprocess R-fMRI data to remove noise and align images to standard space. Key steps include slice-timing correction, motion realignment, nuisance regression (e.g., motion parameters, CompCor), and temporal filtering.

- Metric Calculation: Generate voxel-wise maps of various intrinsic functional metrics, such as:

- Regional Homogeneity (ReHo): Measures local synchronization of neural activity.

- Degree Centrality (DC): Quantifies the number of functional connections a voxel has to the rest of the brain.

- Voxel-Mirrored Homotopic Connectivity (VMHC): Assesss functional connectivity between symmetrical points in the two hemispheres.

- Fractional Amplitude of Low-Frequency Fluctuations (fALFF): Reflects the power of spontaneous low-frequency brain activity.

- Group-Level Analysis: Statistically compare these maps between the ASD and control groups to identify regions with significant differences.

- Interpretation: Relate the findings to known brain networks and existing theories of ASD neurobiology, such as theories of hypoconnectivity and hyperconnectivity.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Handling Site-Related Heterogeneity Challenge: ABIDE data is aggregated from multiple scanners and sites, introducing unwanted technical variance that can confound biological signals [23]. Solution: Incorporate "site" as a covariate in your statistical models. Alternatively, use ComBat or other harmonization techniques to remove site-specific biases before conducting group analyses. Testing whether your findings replicate within individual sites can also bolster their robustness.

Issue 2: Addressing Data Quality and Motion Artifacts Challenge: Head motion during scanning is a major confound in fMRI, particularly in clinical populations. Solution: Leverage the mean framewise displacement (FD) metric provided in the ABIDE phenotypic files [18]. Apply a strict threshold (e.g., mean FD < 0.2 mm) to exclude high-motion subjects. Research shows this simple step can dramatically improve data quality and classification accuracy [6].

Issue 3: Navigating the Accuracy vs. Interpretability Trade-off Challenge: Complex machine learning models like deep learning may achieve high accuracy but act as "black boxes," making it difficult to understand which brain features drive the classification [6]. Solution: Integrate Explainable AI (XAI) methods into your pipeline. Systematically benchmark methods like Integrated Gradients to identify the most critical brain regions for your model's decisions. This not only builds clinical trust but also allows you to validate your findings against the established neuroscience literature [6].

Welcome to the fMRI Preprocessing Technical Support Center

This guide is designed within the context of advanced fMRI research for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) analysis. It addresses common challenges researchers and drug development professionals face when transforming raw neuroimaging data into reliable, analysis-ready formats, a critical step for identifying robust biomarkers [6].

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: What are the fundamental, non-negotiable first steps in any fMRI preprocessing pipeline for clinical research? A: The initial steps focus on stabilizing the signal and aligning data for group analysis. The core sequence is:

- Format Conversion & Organization: Convert scanner-specific raw data (e.g., DICOM) into the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) format to ensure consistency and reproducibility.

- Slice Timing Correction: Accounts for the fact that different slices within a volume are acquired at slightly different times.

- Motion Correction (Realignment): Aligns all volumes in a time series to a reference volume (usually the first or mean) to correct for head motion. This is critical, as motion artifacts can severely confound functional connectivity measures, especially in ASD populations [6]. Framewise displacement (FD) should be calculated here for subsequent quality control (QC) [24].

- Coregistration: Aligns the functional (fMRI) data to the participant's high-resolution structural (T1-weighted) scan.

- Normalization (Spatial Normalization): Warps individual brain images into a standard stereotaxic space (e.g., MNI152) to enable group-level comparisons.

- Spatial Smoothing: Applies a Gaussian kernel to increase the signal-to-noise ratio and account for anatomical variability.

Q2: Our ASD classification model's performance is highly variable. Could preprocessing inconsistencies be the cause, and how can we standardize this? A: Yes, preprocessing variability is a major source of irreproducibility. A study on ASD classification systematically cross-validated findings across three different preprocessing pipelines to ensure robustness [6]. To standardize:

- Adopt Established Pipelines: Use widely-tested, containerized pipelines like fMRIPrep or HCP Pipelines to ensure consistent execution of steps from slice timing correction to normalization.

- Parameter Documentation: Meticulously document every parameter (smoothing kernel size, normalization method, etc.) as part of your methods.

- QC Integration: Embed automated QC at each stage. For example, after motion correction, generate and review framewise displacement plots. The HBCD protocol recommends calculating the number of seconds with FD < 0.2 mm, a metric shown to improve ASD classification accuracy when used as a filter [6] [24].

Q3: How do we effectively handle physiological noise (e.g., from heartbeat and respiration) in resting-state fMRI data for drug development studies? A: Physiological noise is a pervasive confound that can mimic or obscure neural signal. Correction is essential for reliable biomarker discovery.

- RETROICOR (Retrospective Image Correction): This is a standard method that uses recorded cardiac and respiratory signals to model and remove noise from the fMRI time series [25] [26]. It improves temporal signal-to-noise ratio (tSNR).

- Implementation Choice: For multi-echo fMRI data, you can apply RETROICOR to individual echoes before combining them (

RTC_ind) or to the combined data (RTC_comp). Research shows both are viable, with benefits most notable in moderately accelerated acquisitions (multiband factors 4 and 6) [25] [26]. - Multi-Echo ICA (ME-ICA): A data-driven alternative that does not require external physiological recordings. It uses the differential decay of BOLD and non-BOLD signals across echo times to separate noise components [25].

Table 1: Impact of Acquisition Parameters on RETROICOR Efficacy Based on findings from [25] [26]

| Parameter | Recommended Setting for Optimal RETROICOR Performance | Effect on Data Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Multiband Acceleration Factor | Moderate (Factors 4 & 6) | Good quality preservation and noise correction. |

| High (Factor 8) | Can degrade overall quality, limiting correction benefits. | |

| Flip Angle | Lower angles (e.g., 45°) | Shows notable improvement in tSNR and signal fluctuation sensitivity (SFS) after RETROICOR. |

| Echo Time (TE) | Multiple, spaced echoes (e.g., 17, 34.6, 52.3 ms) | Enables multi-echo processing methods like ME-ICA for superior noise separation. |

Q4: What specific quality control (QC) metrics should we compute and visualize for every fMRI dataset in an autism study? A: Rigorous QC is non-optional. The HBCD study provides a comprehensive framework for automated and manual QC [24].

- Automated Metrics (Must-Calculate):

- Motion: Mean and maximum framewise displacement (FD);

subthresh_02(seconds with FD < 0.2mm) [24]. - Signal Quality: Temporal SNR (

tSNR) within a brain mask [24]. - Spatial Characteristics: Full-width at half maximum (

FWHM_x/y/z) of spatial smoothness [24]. - Artifacts: Automated detection of line artifacts and field-of-view (FOV) cutoff [24].

- Motion: Mean and maximum framewise displacement (FD);

- Manual Review (Gold Standard): Trained technicians should review data, scoring artifacts (0-3 scale) for:

- Motion (blurring, ripples)

- Susceptibility artifacts (signal dropout, bunching)

- FOV cutoff and line artifacts [24].

- Application in ASD Research: A study achieved 98.2% classification accuracy by applying a stringent FD filter (>0.2 mm) to the ABIDE I dataset, highlighting the critical impact of motion QC on results [6].

Q5: We are creating functional connectivity templates for an ASD biomarker study. Does the demographic composition of the template group matter? A: Absolutely. Template matching is used to screen for abnormal functional activity or connectivity maps. Research shows:

- Sample Size: Larger sample sizes in the template group improve template matching scores, with diminishing returns after a certain point [27].

- Age & Gender: Using age- or gender-specific templates can increase match correlations. The effect of age is generally larger than gender [27].

- Practical Guidance: If your database is large enough, demographic-specific templates are beneficial. However, a large, demographically-mixed template often outperforms a small, specific one due to the power of sample size [27].

- Hemisphere-Specific Templates: For tasks with clear lateralization (e.g., language), creating templates for the task-dominant hemisphere alone can enhance matching accuracy [27].

Q6: Our deep learning model for ASD diagnosis is a "black box." How can we preprocess data to facilitate model interpretability and biological validation? A: This is a crucial gap in translational neuroimaging [6]. The pipeline must support explainable AI (XAI).

- Preprocessing for XAI: Ensure your pipeline outputs standardized, high-quality functional connectivity matrices (e.g., from preprocessed time series). Inconsistent preprocessing introduces noise that obscures true biomarkers.

- Benchmarking Interpretability Methods: Research indicates that for fMRI connectivity data, gradient-based interpretability methods, particularly Integrated Gradients, are the most reliable for identifying which brain connections drive a model's decision [6]. This was established using the Remove And Retrain (ROAR) benchmarking technique [6].

- Biological Plausibility Check: The final step in your "preprocessing-for-analysis" pipeline should be to validate identified important regions against independent neuroscientific literature. For instance, an interpretable ASD model consistently highlighted visual processing regions (calcarine sulcus, cuneus), which was later supported by independent genetic studies, confirming it captured a genuine biomarker rather than noise [6].

Standard fMRI Preprocessing and QC Workflow

Q7: What is the ROAR framework, and how do we use it to benchmark interpretability methods in our ASD pipeline? A: Remove And Retrain (ROAR) is a benchmark to evaluate the faithfulness of interpretability methods [6].

- Train: Train your initial classification model (e.g., on fMRI connectivity data).

- Interpret: Use an interpretability method (e.g., Integrated Gradients, Saliency Maps) to rank the importance of all input features (brain connections).

- Remove & Retrain: Iteratively remove the top-ranked "important" features (e.g., 10%, 20%, ... 100%) from the dataset, then retrain and test a new model from scratch each time.

- Evaluate: A faithful interpretability method will identify features that are truly important for prediction. Therefore, as these features are removed, model performance should drop precipitously. If performance drops slowly or not at all, the interpretability method is not reliably identifying critical features.

The ROAR Benchmarking Procedure for XAI Methods

Q8: We are integrating multimodal data (sMRI, fMRI, genetics). How should we preprocess each modality before fusion? A: A successful multimodal fusion framework for ASD requires dedicated, optimized preprocessing for each stream before adaptive integration [28].

- Structural MRI (sMRI): Standard pipeline includes inhomogeneity correction, skull-stripping, tissue segmentation, and cortical surface reconstruction. Features can be cortical thickness, volume, or surface area.

- Functional MRI (fMRI): Follow the comprehensive pipeline above (Q1-Q6). The key output is a functional connectivity matrix (e.g., correlation between region time series).

- Genetic Data: Preprocessing involves quality control, imputation, and annotation. Features can be polygenic risk scores or expression levels of candidate genes (e.g., genes implicated in visual cortex like MYCBP2, CAND1 [28]).

- Fusion Strategy: Use an adaptive late fusion strategy. First, train separate high-performance models on each preprocessed modality (e.g., a Hybrid CNN-GNN on sMRI, a classifier on connectivity matrices). Then, use a mechanism (like a Multilayer Perceptron with attention) to weight each modality's prediction based on its validation performance, dynamically adjusting the contribution [28].

Adaptive Multimodal Fusion Framework for ASD Diagnosis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for fMRI Preprocessing in ASD Research

| Item | Category | Function/Benefit | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABIDE I/II Datasets | Data Repository | Large-scale, publicly shared ASD vs. control datasets with resting-state fMRI and phenotypic data, enabling benchmarking and model training. | Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange [6] [29] |

| BIDS Format | Data Standard | Organizes neuroimaging data in a consistent, machine-readable structure, crucial for reproducibility and pipeline automation. | Brain Imaging Data Structure |

| fMRIPrep | Software Pipeline | A robust, containerized pipeline for automated preprocessing of fMRI data, minimizing inter-study variability. | https://fmriprep.org |

| FSL / AFNI | Software Suite | Comprehensive toolkits for statistical analysis and preprocessing of neuroimaging data, including motion correction, filtering, and connectivity analysis. | FMRIB Software Library; AFNI |

| RETROICOR | Algorithm | Removes physiological noise (cardiac, respiratory) from fMRI time series using recorded physiological traces, improving tSNR. | [25] [26] |

| Integrated Gradients (XAI) | Interpretability Method | A gradient-based approach identified as highly reliable for interpreting deep learning models on fMRI connectivity data. | [6] |

| ROAR Benchmark | Evaluation Framework | A method to rigorously test and compare the faithfulness of different interpretability methods by measuring performance drop after feature removal. | Remove And Retrain [6] |

| QC Metrics (FD, tSNR) | Quality Control | Quantitative measures to automatically flag problematic scans. Framewise Displacement (FD) and temporal Signal-to-Noise Ratio (tSNR) are fundamental. | [6] [24] |

| BrainSwipes | QC Platform | A gamified, crowdsourced platform for manual visual quality control of derivative data (e.g., preprocessed images, connectivity maps). | HBCD Initiative [24] |

Building Your Pipeline: Core Preprocessing Steps and Advanced Methodologies

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Slice Timing Correction

Q1: My statistical maps show inconsistent activation. Could this be related to how I performed slice timing correction?

Yes, inconsistent activation can arise from improper slice timing correction, especially with a long TR. During acquisition, slices within a volume are captured at different times. If not corrected, the hemodynamic response function (HRF) model will be misaligned with the data for slices acquired later in the TR cycle [4]. To troubleshoot:

- Verify Reference Slice and Model Alignment: Ensure the reference slice used in slice timing correction matches the

Microtime onset(fMRI_T0) parameter in your first-level statistical model. A mismatch means your HRF model is aligned to the wrong time point [30]. - Check Slice Order and Timing: Using an incorrect slice order (e.g., sequential vs. interleaved) or inaccurate slice timings will introduce error. Always confirm this acquisition metadata from your scanner sequence [30].

- Consider TR Length: For studies with a TR longer than 2 seconds, slice timing correction is particularly beneficial. For shorter TRs (≤2s), some studies bypass this step in favor of using a temporal derivative of the HRF in the statistical model, which can account for minor timing differences without interpolating the data [30].

Q2: Should I perform slice timing correction before or after motion correction?

The order is debated, and the optimal choice can depend on your data [30].

- Slice Timing First: This order is advised if you use a complex (e.g., interleaved) slice order or if you expect significant head movement. Performing motion correction after slice timing ensures that the data used for realignment has been temporally synchronized [30].

- Motion Correction First: This can be suitable if you use a contiguous slice order and expect only slight head motion. A key argument for this order is that it prevents the potential propagation of motion-induced intensity changes across the time series during slice timing interpolation [30].

- Simultaneous Correction: Advanced methods exist that perform realignment and slice timing correction simultaneously to avoid the interactions between these steps entirely [30].

Motion Correction

Q3: Despite motion correction, I still see strong motion artifacts in my functional connectivity maps. What could be the cause?

Motion correction (realignment) only corrects for spatial misalignment between volumes. It does not remove the signal intensity changes caused by motion, which can persist as confounds in the time series of voxels [4]. These residual motion artifacts can inflate correlation measures and create spurious functional connections [31]. To address this:

- Inspect Motion Parameters: Plot the six rigid-body motion parameters (translation: x, y, z; rotation: roll, pitch, yaw) over time. Sudden, large displacements indicate "spikes" of motion that are particularly problematic [4].

- Use Motion Parameters as Nuisance Regressors: Include the motion parameters and their derivatives as regressors of no interest in your general linear model to remove motion-related variance from the BOLD signal [31].

- Consider "Scrubbing": For severe motion spikes, you can censor (remove) the affected volumes from analysis [31].

- Evaluate Pipeline Order: Be aware that performing temporal filtering after motion regression can reintroduce motion-related frequencies back into the signal. Where possible, combine nuisance regressions into a single step or use sequential orthogonalization [31].

Q4: What are the accepted thresholds for head motion in an autism cohort, which may include participants with higher motion?

While universal thresholds don't exist, commonly used benchmarks from the literature can guide quality control. The table below summarizes widely used motion thresholds. For autism research, it is critical to report the motion levels and exclusion criteria used, and to ensure that motion does not systematically differ between autistic and control groups, as this can confound results.

Table 1: Common Motion Thresholds for fMRI Data Exclusion

| Metric | Typical Exclusion Threshold | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Framewise Displacement (FD) | > 0.2 - 0.5 mm | Quantifies volume-to-volume head movement. A higher threshold (e.g., 0.5mm) may be necessary for pediatric or clinical populations to avoid excessive data loss. |

| Maximum Translation | > 2 - 3 mm | The largest absolute translation in any direction. |

| Maximum Rotation | > 2 - 3 ° | The largest absolute rotation around any axis. |

Co-registration and Normalization

Q5: The alignment between my functional and anatomical images is poor. How can I improve co-registration?

Poor co-registration can stem from several issues related to the data and the algorithm.

- Use High-Quality Anatomicals: The reference anatomical image should be a high-resolution (e.g., 1mm³ isotropic), skull-stripped volume to provide a clear target for alignment [32].

- Check for Distortions: Geometric distortions in the functional data, often present in regions with magnetic field inhomogeneities (e.g., near sinuses), can prevent accurate alignment. If available, use field maps to unwarp your functional images before co-registration [32].

- Manual Initialization: If the functional and anatomical scans were acquired in different sessions or on different scanners, the automated header-based alignment may fail. In such cases, manually specify corresponding landmarks (e.g., the anterior commissure) to provide a gross initial alignment for the algorithm to refine [32].

- Inspect and Adjust Cost Function: Different cost functions (e.g., mutual information, correlation ratio) are optimized for different types of image contrast. If the default cost function fails, experimenting with alternatives may yield a better result [32].

Q6: What are the key differences between the Talairach and MNI templates, and which should I use for my multi-site autism study?

The choice of template is crucial for normalization, especially in multi-site studies where scanner and protocol differences exist.

Table 2: Comparison of Standard Brain Templates for Normalization

| Feature | Talairach Atlas | MNI Templates (e.g., ICBM152) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Post-mortem brain of a single, 60-year-old female [32]. | MRI data from hundreds of healthy young adults [32]. |

| Representativeness | Single subject; may not represent population anatomy. | Population-based; more representative of a neurotypical brain. |

| Spatial Characteristics | Has larger temporal lobes compared to the MNI template [32]. | Considered the modern standard for cortical mapping [32]. |

| Recommendation | Largely historical; not recommended for new studies. | Recommended. The MNI template, particularly the non-linear ICBM152 symmetric version, is the current best practice for multi-site studies [32]. |

For autism research, using the MNI template enhances comparability with the vast majority of contemporary literature. fMRIPrep and other modern pipelines are optimized for MNI space.

General Preprocessing & Artifacts

Q7: After preprocessing with fMRIPrep, I see strange linear artifacts in my images. What are they?

These linear patterns are typically interpolation artifacts and are often a visualization issue, not a problem with the data itself. They occur when you view the preprocessed data in a "world coordinate" display space, which reslices the volume data off its original voxel grid [33].

- Solution 1 (in FSLeyes): Click the

Wrenchicon and change theDisplay Spaceto the image's native space (e.g.,T1worBOLDspace) instead ofWorldcoordinates [33]. - Solution 2 (in FSLeyes): Click the

Gearicon for the image layer and change theInterpolationmethod fromNearest neighbourtoLinearorSpline[33].

Q8: The preprocessing steps I use are not commutative. In what order should I perform them?

You are correct; the order of linear preprocessing steps (like regression and filtering) is critical because they are not commutative. Performing steps in a modular sequence can reintroduce artifacts removed in a previous step [31]. For example, high-pass filtering after motion regression can reintroduce motion-related signal.

- Recommended Solution: The most robust approach is to perform all nuisance regressions (motion parameters, white matter signal, etc.) and temporal filtering in a single, combined linear model. This avoids the issue of artifact reintroduction [31].

- Alternative Solution: If a sequential pipeline is necessary, you must orthogonalize later covariates and filters with respect to those removed earlier [31].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standardized Preprocessing Protocol for Autism Research

The following workflow, implemented in a tool like fMRIPrep, represents a robust, state-of-the-art protocol for minimal preprocessing of fMRI data, ensuring consistency and reproducibility in multi-site autism studies [34] [35].

Diagram 1: Standardized fMRI Preprocessing Workflow

Detailed Methodology:

- Data Input and Validation: The pipeline begins with data structured according to the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) standard, which ensures consistent metadata and organization [35].

- Anatomical Data Preprocessing:

- Brain Extraction: The T1-weighted image is skull-stripped to create a brain mask [34].

- Tissue Segmentation: The brain is segmented into cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), white matter (WM), and gray matter (GM) [34]. These segmentations are used for co-registration and for extracting nuisance signals later.

- Functional Data Preprocessing:

- Slice Timing Correction: Corrects for acquisition time differences between slices within a volume. The reference slice should be documented and matched in the statistical model [30].

- Motion Correction: Aligns all functional volumes to a reference volume (often the first or an average) using rigid-body transformation to correct for head motion [4].

- Distortion Correction: Uses field map data to correct for geometric distortions in the functional images caused by B0 field inhomogeneities [32].

- Co-registration: The motion-corrected functional data is aligned to the subject's own T1-weighted anatomical scan. Modern tools like fMRIPrep use Boundary-Based Registration (BBR), which aligns the functional image to the white matter surface derived from the T1w scan, for improved accuracy [34].

- Spatial Normalization: The co-registered data is warped into a standard stereotaxic space (e.g., MNI152) to allow for group-level analysis. This involves non-linear transformations to account for the anatomical differences between individual brains and the template [32].

Table 3: Key Software Tools for fMRI Preprocessing and Analysis

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function / Strength | Website / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| fMRIPrep | End-to-end Pipeline | Robust, automated, and analysis-agnostic minimal preprocessing for task and resting-state fMRI. Highly recommended for reproducibility. | https://fmriprep.org/ [34] |

| SPM | Software Library | A comprehensive MATLAB-based package for statistical analysis of brain imaging data, including extensive preprocessing tools. | https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/ [36] |

| FSL | Software Library | A comprehensive library of tools for MRI analysis. Includes FEAT (model-based analysis), MELODIC (ICA), and MCFLIRT (motion correction). | https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/ [36] |

| AFNI | Software Library | A suite of C programs for analyzing and displaying functional MRI data. Known for its flexibility and scripting capabilities. | https://afni.nimh.nih.gov/ [36] |

| FreeSurfer | Software Suite | Provides tools for cortical surface-based analysis, including reconstruction, inflation, and flattening of the brain. | https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/ [36] |

| DPABI | Software Library | A user-friendly toolbox that integrates volume-based (DPARSF) and surface-based (DPABISurf) processing pipelines. | [37] |

| BIDS Validator | Data Validator | Ensures your dataset conforms to the BIDS standard, which is a prerequisite for running pipelines like fMRIPrep. | https://bids-standard.github.io/bids-validator/ [35] |

Quality Control Protocol

Robust quality control (QC) is non-negotiable, particularly for autism research where data heterogeneity can be high. The following protocol should be performed on every dataset [37].

Diagram 2: fMRI Preprocessing Quality Control Workflow

Detailed QC Steps:

- Visual Inspection of Raw Images [4]:

- Purpose: Identify gross artifacts, signal dropouts, missing slices, or incorrect field-of-view that would make the data unusable.

- Protocol: Scroll through the T1w and all BOLD runs in all three planes. Look for ringing, ghosting, and zipper artifacts.

- Visual Inspection of Preprocessing Outputs:

- Brain Extraction: Verify the brain mask accurately follows the cortical surface without including excessive non-brain tissue or excluding brain tissue [37].

- Co-registration: Overlay the functional mean image on the T1w anatomical. The edges of the brain and internal structures (e.g., ventricles) should align precisely [34].

- Normalization: Check the normalized functional image in standard space. The brain should be correctly positioned within the MNI template without unusual deformations [37].

- Review of Automated QC Metrics:

- Head Motion: Use the framewise displacement (FD) plot to identify subjects with excessive motion. Apply consistent exclusion thresholds (e.g., mean FD > 0.2mm) across all groups [37].

- Other Metrics: Review other pipeline-specific metrics, such as the contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) and the Dice score for tissue overlap after segmentation.

In the data preprocessing pipeline for fMRI-based autism spectrum disorder (ASD) research, the selection of a brain atlas is a critical step that directly influences the validity, reproducibility, and interpretability of your findings. Brain atlases serve as reference frameworks that parcellate the brain into distinct regions of interest (ROIs), enabling the standardized analysis of functional connectivity across individuals and studies [38] [39]. The choice of atlas—whether anatomical or functional, coarse or dense—can significantly alter the extracted features and the performance of subsequent machine learning models for ASD classification [38]. This guide provides a structured comparison of five commonly used atlases and troubleshooting advice for researchers navigating this complex decision.

Atlas Comparison and Performance Metrics

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the five atlases and their documented performance in ASD classification studies.

Table 1: Brain Atlas Characteristics and Reported Performance in ASD Classification

| Atlas Name | Type | Number of ROIs | Reported Accuracy in ASD Studies | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAL (Automated Anatomical Labeling) [38] [39] | Anatomical | 116 | 82.0% [38] | Computational efficiency; less prone to overfitting with small datasets [38]. | May miss fine-grained connectivity details due to coarser granularity [38]. |

| Harvard-Oxford [38] [39] | Anatomical | 48 | 74.7% - 83.1% [38] | Anatomically defined regions; used in robust graph neural network approaches [38]. | Lower number of ROIs may oversimplify functional connectivity patterns. |

| CC200 (Craddock-200) [38] [39] | Functional | 200 | 76.52% [38] | Good balance between spatial resolution and computational demand. | Handcrafted feature selection can limit generalization [38]. |

| CC400 (Craddock-400) [38] [39] | Functional | 400 | Provides high granularity [38] | High-resolution insights into functional networks; captures subtle connectivity variations [38]. | Requires large datasets and more computational resources; risk of overfitting [38]. |

| Yeo 7/17 [38] [39] | Functional | 114 | 85.0% [38] | Aligns with well-characterized large-scale brain networks; effective in ensemble learning models [38]. | Handcrafted features in initial stages may introduce bias [38]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Atlas-Based Feature Extraction for Machine Learning Classification

This protocol details the steps for extracting functional connectivity features from preprocessed fMRI data using a selected brain atlas, a common approach in ASD classification studies [38] [8].

- Data Input: Begin with preprocessed resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) data. Key preprocessing steps should include slice-time correction, motion correction, normalization, and co-registration to a standard template [38] [39].

- Atlas Application (Parcellation): Map the preprocessed fMRI data to your chosen brain atlas. This step assigns each voxel in the brain to a specific ROI defined by the atlas (e.g., 116 ROIs for AAL, 400 for CC400) [38] [39].

- Time-Series Extraction: For each subject, extract the average Blood Oxygenation Level-Dependent (BOLD) signal time-series from all voxels within each ROI.

- Functional Connectivity Matrix Construction: Calculate a pairwise connectivity matrix between all ROIs. This is typically done by computing the Pearson correlation coefficient between the time-series of every ROI pair. The result is a symmetric N x N matrix (where N is the number of ROIs) representing the strength of functional connectivity across the brain.

- Feature Vectorization: Convert the upper or lower triangle of the correlation matrix (excluding the diagonal) into a one-dimensional feature vector. This vector serves as the input for machine learning classifiers.

- Model Training and Validation: Use the feature vectors to train a classifier (e.g., Support Vector Machine, Artificial Neural Network) to distinguish between ASD and control groups. Always employ rigorous cross-validation techniques to avoid overfitting and ensure generalizability [8].

Protocol: Evaluating Atlas Performance Using a Standardized Dataset

To empirically compare the impact of different atlases, use a publicly available dataset like the Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE) [8].

- Dataset Selection: Download rs-fMRI and phenotypic data from a standardized repository such as ABIDE I or ABIDE II [8].

- Parallel Preprocessing: Preprocess the data from a fixed subset of subjects (e.g., 871 participants [38]) using a consistent pipeline.

- Multi-Atlas Feature Extraction: Execute the feature extraction protocol (above) in parallel for each atlas (AAL, Harvard-Oxford, CC200, CC400, Yeo).

- Model Training and Evaluation: Train a standard classifier (e.g., SVM) on the feature sets from each atlas. Use the same cross-validation splits for all atlases to ensure a fair comparison.

- Performance Metrics Comparison: Compare the classification accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity achieved by each atlas-based model to determine which provides the best performance for your specific research question [38].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting a brain atlas based on your research goals and constraints, as informed by the data in Table 1.

Atlas Selection Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: My ASD classification model is overfitting, especially with a limited dataset. Could my atlas choice be a factor? Yes, absolutely. Denser atlases like the CC400 (400 ROIs) generate a very high number of features (connections), which can easily lead to overfitting when the number of subjects is small [38].

- Solution: Switch to a coarser atlas with fewer ROIs, such as AAL (116 ROIs) or Harvard-Oxford (48 ROIs). These atlases summarize brain activity across broader regions, reducing the feature dimensionality and mitigating overfitting [38].

Q2: I need to capture subtle, fine-grained connectivity differences in ASD. The AAL atlas seems to miss these. What are my options? You should consider using a denser functional atlas. The CC400 atlas is specifically noted for providing high-resolution insights into functional networks, allowing researchers to capture subtle variations in connectivity that coarser atlases might miss [38]. The Yeo atlas is also a strong candidate as it parcellates the brain based on well-established large-scale functional networks [38] [39].

Q3: Is there a way to leverage the strengths of multiple atlases in a single analysis? Yes, a multi-atlas ensemble approach is an emerging and powerful strategy. This involves extracting features using multiple different atlases and then combining them within a single machine learning model, such as a weighted deep ensemble network [40]. Studies have shown that combining multiple atlases can enhance feature extraction and provide a more comprehensive understanding of ASD by leveraging the strengths of both anatomical and functional parcellations [38].

Q4: How can I quantitatively compare my novel findings to existing network atlases to improve the interpretation of my results? You can use standardized toolkits like the Network Correspondence Toolbox (NCT). The NCT allows you to compute spatial correspondence (e.g., Dice coefficients) between your neuroimaging results (e.g., activation maps) and multiple widely used functional brain atlases, providing a quantitative measure of overlap and aiding in standardized reporting [41].

Table 2: Key Resources for fMRI-based ASD Research

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research | Reference/Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABIDE (Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange) | Dataset | Publicly available repository of preprocessed fMRI data from ASD individuals and typical controls, essential for benchmarking. | [8] |

| AAL Atlas | Software/Brain Atlas | Anatomical atlas for defining 116 ROIs; ideal for studies prioritizing computational efficiency. | [38] [39] |

| CC200 & CC400 Atlases | Software/Brain Atlas | Functional atlases for defining 200 or 400 ROIs; used for high-granularity connectivity analysis. | [38] [39] |

| Yeo 7/17 Networks Atlas | Software/Brain Atlas | Functional atlas parcellating the brain into 114 ROIs based on large-scale resting-state networks. | [38] [39] |

| Network Correspondence Toolbox (NCT) | Software Toolbox | Quantifies spatial overlap between new findings and existing atlases, standardizing result interpretation. | [41] |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Algorithm | A widely used and robust classifier in neuroimaging for distinguishing ASD from controls based on connectivity features. | [8] |

## Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is the choice of denoising pipeline particularly critical for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) fMRI studies? ASD cohorts often present with greater in-scanner head motion, which can introduce systematic artifacts into the data [42]. The choice of denoising strategy directly influences the detection of group differences. For example, the use of Global Signal Regression (GSR) has been shown to reverse the direction of observed group differences between ASD and control participants, potentially leading to spurious conclusions [43]. Furthermore, the high heterogeneity in ASD means that findings are especially vulnerable to inconsistencies from site-specific effects and preprocessing choices, making robust denoising essential for replicable results [44].

Q2: What is the fundamental limitation of nuisance regression in dynamic functional connectivity (DFC) analyses? Research indicates that nuisance regression does not necessarily eliminate the relationship between DFC estimates and the magnitude of nuisance signals. Strong correlations between DFC estimates and the norms of nuisance regressors (e.g., from white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, or the global signal) can persist even after regression is performed. This is because regression alters the correlation structure of the time series in a complex, non-linear way that is not fully corrected by standard methods, potentially leaving residual nuisance effects in the dynamic connectivity measures [45].

Q3: My fMRIPrep processed data fails in the subsequent C-PAC analysis for nuisance regression. What should I check?

This is a common integration issue. First, verify that your C-PAC pipeline configuration is specifically set for fMRIPrep ingress by using a preconfigured pipeline file like pipeline_config_fmriprep-ingress.yml. Second, ensure that the derivatives_dir path in your data configuration file points directly to the directory containing the subject's fMRIPrep output. Finally, confirm the existence and correct naming of the confounds file (e.g., *_desc-confounds_timeseries.tsv) within the subject's func directory, as C-PAC requires this file to find the nuisance regressors [46].

Q4: What is an advanced alternative to traditional head motion correction, and how does it benefit ASD research? Independent Component Analysis-based Automatic Removal of Motion Artifacts (ICA-AROMA) is a robust alternative. Unlike simple regression of motion parameters, ICA-AROMA uses a data-driven approach to identify and remove motion-related components from the fMRI data. Studies on ASD datasets have shown that ICA-AROMA, especially when combined with other physiological noise corrections, outperforms traditional strategies. It better differentiates ASD participants from controls by revealing more significant functional connectivity networks, such as those linked to the posterior cingulate cortex and postcentral gyrus [42].

Q5: Should band-pass temporal filtering be applied before or after nuisance regression? While the search results do not explicitly define the order, established best practices in fMRI preprocessing recommend performing band-pass filtering after nuisance regression. The rationale is that the regression step can introduce temporal correlations and low-frequency drifts into the data. Applying the temporal filter afterward ensures these regression-induced artifacts are removed, resulting in a cleaner BOLD signal for subsequent functional connectivity or statistical analysis.

## Troubleshooting Guides

### Problem 1: Inconsistent Group Differences After Global Signal Regression (GSR)

- Symptoms: Your case-control study (e.g., ASD vs. neurotypical) shows a pattern of group differences that reverses or changes dramatically when you add or remove GSR from your pipeline. You may also observe a high prevalence of negative correlations in your connectivity matrices.

- Background: GSR centers the entire correlation matrix around zero, which can artificially induce negative correlations. Because clinical groups like ASD can have systematically different global levels of correlation, GSR disproportionately affects their data, altering the apparent direction and location of group differences [43].

- Solution Steps:

- Benchmark Your Results: Always run your analysis with and without GSR. Report the findings from both pipelines to provide a complete picture.

- Consider Alternatives: Implement a more targeted denoising method such as ICA-AROMA or aCompCor (anatomical component-based noise correction). These methods aim to remove noise without relying on the global mean signal [42].

- Validate with Behavior: Check if the functional connectivity differences identified with GSR correlate with clinical symptom scores within your ASD group. A lack of such correlation can indicate that the findings are artifactual [43].

### Problem 2: High Residual Correlation Between Head Motion and Functional Connectivity (QC-FC)

- Symptoms: Even after denoising, you find a significant correlation between subject-level head motion (e.g., mean Framewise Displacement) and the strength of functional connectivity across many brain connections.

- Background: This is a known indicator of residual motion artifact, which can confound group comparisons if motion levels differ between groups (e.g., if ASD participants move more than controls).

- Solution Steps:

- Quantify the Problem: Calculate the QC-FC correlation for your chosen pipeline. This involves correlating each subject's mean FD with every connection in their functional connectome, then assessing the proportion of significant correlations [44].

- Switch to a Robust Pipeline: Adopt a denoising strategy demonstrated to minimize QC-FC correlations. Research on the ABIDE dataset shows that pipelines incorporating ICA-AROMA significantly reduce the proportion of edges with significant QC-FC correlations compared to traditional methods [42].

- Incorporate Censoring: For datasets with severe motion, use volume censoring ("scrubbing") to remove high-motion time points from analysis, though this may come at the cost of reduced temporal degrees of freedom.

### Problem 3: Failure to Replicate ASD Connectivity Findings Across Datasets

- Symptoms: Functional connectivity differences identified in one ASD cohort (e.g., from one research site) do not hold up in another cohort from a different site or study.

- Background: Replicability in ASD neuroimaging is a major challenge. A primary source of variability is not the denoising pipeline itself, but "site effects," which encompass differences in participant cohorts, scanners, and acquisition protocols [44].

- Solution Steps:

- Harmonize Data: If pooling multi-site data, use statistical harmonization techniques like ComBat to remove site-specific biases before analyzing functional connectivity.

- Report Exhaustively: Clearly document all acquisition parameters, participant characteristics, and the exact denoising pipeline used to facilitate cross-study comparison.

- Validate Internally: When possible, use a split-sample or cross-validation approach within your own dataset to ensure the robustness of your findings.

## Experimental Protocols & Performance

### Table 1: Comparison of Denoising Pipeline Efficacy on ABIDE I Data

This table summarizes findings from a systematic evaluation of different denoising strategies on a multi-site ASD dataset, highlighting their impact on motion correction and group differentiation [42] [44].

| Denoising Strategy | Description | Key Performance Metrics | Impact on ASD vs. TD Differentiation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICA-AROMA + 2Phys | Automatic Removal of Motion Artifacts via ICA, plus regression of WM & CSF signals. | Lowest QC-FC correlation after FDR correction [42]. | Revealed more significant FC networks; distinct regions linked to PCC and postcentral gyrus [42]. |

| Global Signal Regression (GSR) | Regression of the average whole-brain signal. | Can reverse the direction of group differences; introduces negative correlations [43]. | Group differences highly inconsistent across independent sites [44]. |

| Traditional (e.g., 6P + WM/CSF) | Regression of 6 head motion parameters and signals from WM & CSF. | Moderate QC-FC correlations; common baseline approach [44]. | Limited number of significantly different networks identified [42]. |

| aCompCor | Anatomical Component-Based Noise Correction: uses PCA on noise ROIs. | Reduces motion-related artifacts without using the global signal. | Considered a viable alternative to GSR; improves specificity [44]. |

### Table 2: Relationship Between Neural Complexity and Intelligence in ASD

This table summarizes a specific research finding on how brain signal complexity relates to non-verbal intelligence in autistic adults, illustrating how denoising is a prerequisite for meaningful brain-behavior analysis [47].

| Participant Group | Complexity Metric | Correlation with Performance IQ (PIQ) | Statistical Significance & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASD (Adults) | Fuzzy Approximate Entropy (fApEn) | Significant negative correlation [47] | p < 0.05; Increased neural irregularity linked to lower PIQ [47]. |

| ASD (Adults) | Fuzzy Sample Entropy (fSampEn) | Significant negative correlation [47] | p < 0.05; Suggests autism-specific neural strategy for cognitive function [47]. |

| Neurotypical Controls | fApEn and fSampEn | No significant correlation with PIQ [47] | Not Significant (p > 0.05); Contrast highlights divergent neural mechanisms in ASD [47]. |

## Workflow Visualizations

### Preprocessing for ASD fMRI Analysis

### Nuisance Regression Decision Guide

## The Scientist's Toolkit

### Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

| Tool / Resource | Function in fMRI Denoising | Relevance to ASD Research |

|---|---|---|

| fMRIPrep | A robust, standardized pipeline for automated fMRI preprocessing, including coregistration, normalization, and noise component extraction. | Ensures reproducible preprocessing across heterogeneous ASD cohorts, mitigating site-specific pipeline variations [48]. |

| ICA-AROMA | A specialized tool for Automatic Removal of Motion Artifacts using Independent Component Analysis. | Effectively addresses the heightened head motion challenge in ASD populations, improving the detection of true functional connectivity differences [42]. |

| ABIDE (I & II) | A publicly available data repository aggregating resting-state fMRI data from individuals with ASD and typical controls. | Serves as a critical benchmark for developing and testing new denoising methods and analytical models in ASD [47] [44]. |

Confounds File (*desc-confounds_timeseries.tsv) |

An output from fMRIPrep containing extracted noise regressors (motion parameters, WM/CSF signals, etc.) for subsequent nuisance regression. | Provides the standardized set of nuisance variables required for flexible and controlled denoising in downstream analysis (e.g., in C-PAC) [46]. |

This technical support center is designed within the context of advanced fMRI data preprocessing for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) analysis research. The goal is to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with practical solutions for constructing robust functional connectivity (FC) matrices, which serve as critical inputs for machine learning models aimed at elucidating ASD heterogeneity and identifying biomarkers [49] [50].

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

Section 1: Data Acquisition & Quality Control

Q1: Our resting-state fMRI data shows high motion artifact, especially in a pediatric ASD cohort. How can we mitigate this to ensure reliable time series for connectivity? A: Implement a rigorous multi-stage quality assurance (QA) pipeline. First, use framewise displacement (FD) and DVARS metrics to flag high-motion volumes. Tools like ICA-FIX (FSL) are essential for data-driven denoising [51]. Incorporate these QA metrics as covariates in subsequent analyses. For group studies, generate principal components from QA metrics to capture the majority of variance in data quality and include these as nuisances in regression models [51].

Q2: How do we ensure consistency when pooling data from multiple sites or scanner types, a common scenario in large-scale ASD studies? A: Employ a harmonized minimal preprocessing pipeline. A successful approach, as used in the Human Connectome Project (HCP), includes volume registration, slice-timing correction, and transformation to a combined volume-surface space (e.g., CIFTI format) [51] [52]. For cross-site validation, demonstrate that a machine learning classifier cannot distinguish the site of origin of control subject data above chance level, confirming data compatibility [50].

Section 2: Preprocessing & Time Series Extraction

Q3: What is the impact of different brain parcellation atlases on the resulting FC matrix and downstream ML analysis? A: The choice of atlas directly influences the dimensionality and interpretability of your FC features. For multimodal integration, using a fine-grained atlas like the Glasser parcellation allows for the alignment of functional, structural (DTI), and anatomical (sMRI) features within consistent regions [52]. However, sensitivity analyses should be conducted. Benchmarking studies often report results across multiple atlases (e.g., Schaefer 100, 200, 400 parcels) to ensure findings are not atlas-dependent [49].

Q4: We see high individual variability in network topography. Should we use a standard atlas or personalize it? A: For ASD research, accounting for individual topography is crucial. The Personalized Intrinsic Network Topography (PINT) algorithm can be applied. It iteratively shifts template region-of-interest (ROI) locations to nearby cortical vertices that maximize within-network connectivity for each individual [51]. This alignment often increases sensitivity to detect true functional connectivity differences between ASD and control groups by reducing spurious variance caused by anatomical misalignment.

Experimental Protocol: Applying the PINT Algorithm

- Input: Preprocessed resting-state fMRI data in CIFTI format (surface vertices).

- Template ROIs: Select seed vertices from canonical resting-state networks (e.g., Yeo 7-networks, excluding limbic due to susceptibility).

- Iterative Search: For each ROI, calculate the partial correlation between each vertex within a defined search radius (e.g., 6mm) and all other ROIs in the same network.