Enhancing Specificity in Autism PPI Networks: From Foundational Maps to Clinical Translation

This article synthesizes the latest methodological and conceptual advances in building specific Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

Enhancing Specificity in Autism PPI Networks: From Foundational Maps to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest methodological and conceptual advances in building specific Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). It explores the foundational shift from generic to cell-type-specific neuronal interactomes, which has uncovered over 1,000 novel interactions. We detail cutting-edge computational methods, including deep learning models that leverage hierarchical information and interaction-specific learning for superior prediction accuracy. The content addresses critical challenges in experimental validation and data integration, providing optimization strategies for researchers. Finally, it evaluates how these refined PPI networks are being validated for their power in identifying convergent biology, nominating drug targets, informing patient stratification, and uncovering novel mechanisms like the gut-brain axis, thereby paving the way for precision medicine in ASD.

Building the Blueprint: Why Neuron-Specific PPI Networks are Revolutionizing Autism Research

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks are fundamental to understanding cellular processes, yet conventional mapping approaches often lack the resolution needed to unravel complex neurodevelopmental disorders like autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The "specificity gap" represents the critical shortfall in understanding how cell-type-specific and isoform-specific interactions contribute to disease mechanisms. Recent studies demonstrate that over 90% of protein interactions in human neurons may be absent from standard databases, which are largely built from non-neural cell lines [1]. Furthermore, alternative splicing generates distinct protein isoforms for most human genes, with different isoforms of the same gene sharing less than 50% of their interaction partners on average [2]. This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers addressing these specificity challenges in autism research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is neuronal context so critical for building accurate PPI networks for autism?

The cellular environment dramatically shapes protein interaction landscapes. A 2023 study systematically compared PPIs in stem-cell-derived human excitatory neurons against traditional models and found that approximately 90% of the over 1,000 identified interactions were novel and not previously reported in standard databases [1]. This striking discrepancy occurs because many proteins and isoforms are uniquely expressed in neuronal contexts, and their interactions depend on neuronal-specific post-translational modifications, co-factors, and subcellular environments not recapitulated in standard cell lines.

Q2: How extensively can alternative splicing alter protein interaction networks?

Alternative splicing can fundamentally rewire interaction networks rather than creating minor variants. Systematic protein-protein interaction profiling of hundreds of human isoform pairs revealed that the majority of isoform pairs (over 50%) share less than half of their interactions [2]. In global interactome network maps, alternative isoforms frequently behave as if encoded by distinct genes rather than minor variants of each other. These functionally divergent isoforms, or "functional alloforms," often interact with partners expressed in highly tissue-specific manners [2].

Q3: What computational resources exist for isoform-specific interaction prediction?

The Isoform-Isoform Interaction Database (IIIDB) provides predicted genome-wide isoform-isoform interactions integrating RNA-seq datasets, domain-domain interactions, and known PPIs [3]. This resource addresses the critical gap in most PPI databases that only provide low-resolution knowledge at the gene level rather than isoform level. Additionally, deep learning approaches are emerging that can integrate sequence, structural, and expression data to predict isoform-specific interactions with increasing accuracy [4].

Q4: How can I validate that detected interactions are specific to neuronal isoforms?

For autism-related proteins like ANK2, which has neuron-specific isoforms containing a "giant exon," validation requires demonstrating both the expression of the specific isoform and its unique interaction capabilities. A 2023 study showed that neuron-specific isoforms of ANK2 establish numerous disease-relevant interactions that require the giant exon for binding [1]. CRISPR-Cas9 editing to eliminate specific isoforms while preserving others, followed by proteomic analysis, can definitively establish isoform-specific interaction networks.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low or No Signal in Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

| Possible Cause | Discussion | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Stringent Lysis Conditions | Strong ionic detergents like sodium deoxycholate in RIPA buffer can disrupt protein-protein interactions, especially for transient or weaker complexes common in signaling pathways. | Use mild lysis buffers (e.g., Cell Lysis Buffer #9803) without strong denaturants. Include sonication to ensure adequate nuclear and membrane protein extraction without disrupting complexes [5]. |

| Low Target Protein Expression | The protein or isoform of interest may be expressed at low levels in your model system, below the detection limit of western blotting. | Consult expression profiling tools (BioGPS, Human Protein Atlas) and scientific literature to confirm adequate expression in your cells or tissue. Always include a positive control lysate [5]. |

| Epitope Masking | The antibody's binding site on the target protein may be obscured by the protein's native conformation or bound interaction partners. | Use an antibody targeting a different epitope region of the protein. Information about epitope regions is typically available in antibody product specifications [5]. |

Problem: Multiple Bands or Non-Specific Binding

| Possible Cause | Discussion | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Isoforms or PTMs | Multiple isoforms or post-translational modifications (phosphorylation, glycosylation, etc.) can cause target proteins to migrate at different molecular weights. | Include an input lysate control. Reference databases like UniProt or PhosphoSitePlus to identify known isoforms or modifications. If bands aren't in the input, the cause is likely non-specific binding to beads [5]. |

| Non-Specific Bead Binding | Proteins can bind non-specifically to the Protein A/G beads themselves or to the IgG of the antibody used for IP. | Include a bead-only control (beads + lysate without antibody) and an isotype control (non-specific antibody of the same species). Pre-clear lysate with beads alone if background is high in the bead-only control [5]. |

Problem: Detection Interference from IgG Heavy/Light Chains

| Possible Cause | Discussion | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody Species Conflict | When the same species antibody is used for IP and western blot, the secondary antibody will detect the denatured heavy (~50 kDa) and light (~25 kDa) chains of the IP antibody, obscuring similar-sized targets. | Use antibodies from different species for IP and western blot (e.g., rabbit for IP, mouse for western). Use species-specific secondary antibodies that do not cross-react [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for Enhanced Specificity

Protocol: Building a Cell-Type-Specific Isoform Interaction Network

This workflow outlines the process for constructing an autism spliceform interaction network (ASIN), as pioneered by Corominas et al. (2014) [6].

Workflow for Isoform Interaction Network

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Isoform-Specific ORF Library Construction:

- Isolate total RNA from disease-relevant tissue (e.g., postmortem brain, stem-cell-derived neurons).

- Perform RT-PCR using primers designed to amplify full-length open reading frames (ORFs) of specific isoforms.

- Clone PCR products using Gateway recombination and sequence individual ORF clones using a deep-well next-generation sequencing approach ("ORF-Seq") [2] [6].

- Curate a physical collection of isoforms, noting that over 60% of brain-expressed isoforms may be novel compared to public databases [6].

High-Throughput Interaction Screening:

- Screen the isoform library using Yeast-Two-Hybrid (Y2H) in two directions: against a comprehensive human ORFeome and for all-against-all interactions within the isoform library itself.

- Use next-generation sequencing to identify interacting pairs from the primary screen, followed by Sanger sequencing confirmation.

- Critically, retest all corresponding protein isoforms for a given gene in pairwise format against all interaction partners of any isoform from that gene. This controls for sampling sensitivity and confirms that interaction differences are due to alternative splicing [6].

Orthogonal Validation and Network Analysis:

- Validate a significant subset (e.g., >60%) of interactions using an orthogonal method like the Mammalian Protein-Protein Interaction Trap (MAPPIT) assay [6].

- Construct the protein interaction network, integrating isoform-level data. This high-resolution network typically reveals that a substantial fraction (∼30%) of interacting partners and nearly half of the interactions are contributed specifically by splicing variants [6].

- Analyze the network for connectivity between proteins encoded by genes in ASD-associated copy number variants (CNVs) and other risk loci.

Protocol: Validating Isoform-Specific Interactions in Neuronal Models

Validation in Neuronal Models

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Model Generation: Use CRISPR-Cas9 to edit human pluripotent stem cells to eliminate a specific protein isoform (e.g., one containing a giant neuron-specific exon) while preserving other isoforms from the same gene. This creates an isogenic control [1].

- Neuronal Differentiation: Differentiate the edited and control cell lines into the relevant neuronal subtype (e.g., neurogenin-2 induced excitatory neurons) to ensure native expression of interacting partners and modifiers.

- Interaction Pull-Down: Perform immunoprecipitation (IP) under non-denaturing conditions using an antibody validated for specificity toward the target protein. Use mild lysis buffers to preserve transient complexes [5].

- Mass Spectrometry: Identify co-precipitating proteins using liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Use robust quantification and statistical analysis to define the interactome.

- Data Integration: Identify interactions that are lost in the isoform-knockout line compared to the isogenic control. Compare this list to interactions found in proteomic studies of human postmortem cerebral cortex to assess in vivo relevance, noting that replication rates may be moderate (~40%) due to cell-type heterogeneity in tissue samples [1].

Computational Tools & Machine Learning Approaches

Deep learning is transforming PPI prediction by automatically extracting features from complex biological data, moving beyond methods that rely on manually engineered features [4].

Key Deep Learning Architectures for PPI Prediction:

| Model Type | Key Mechanism | Application in PPI |

|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Operates on graph structures of proteins, treating amino acids as nodes and their interactions as edges. Excellent for capturing spatial relationships. | Predicting interaction sites, classifying interactions, analyzing PPI networks [4]. |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | Applies sliding filters to detect local patterns in 1D sequences or 2D representations of protein pairs. | Extracting features from amino acid sequences to predict binding [4]. |

| Transformers & Attention Models | Uses attention mechanisms to weigh the importance of different residues or sequence regions, capturing long-range dependencies. | Understanding which parts of a protein sequence are critical for a specific interaction [4]. |

| Multi-Modal & Transfer Learning | Integrates multiple data types (sequence, structure, expression) and leverages knowledge from large pre-trained models (e.g., ESM, ProtBERT). | Improving prediction accuracy, especially for proteins with limited experimental data [4]. |

Application Note: While methods like AlphaFold2 have revolutionized the prediction of endogenous complexes, their performance can drop for de novo interactions (those with no natural precedence). Novel algorithms are being developed to address this, including those based on protein-protein co-folding and methods that learn from molecular surface properties, which are particularly promising for predicting interactions induced by small-molecule "molecular glues" [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Mild Cell Lysis Buffer (e.g., Cell Lysis Buffer #9803) | Extracts proteins while preserving native complexes for Co-IP. Avoids denaturing interactions. | Prefer over RIPA buffer for interaction studies. Include protease and phosphatase inhibitors [5]. |

| Isoform-Specific Antibodies | Validated antibodies for immunoprecipitation and detection of specific protein isoforms. | Critical for distinguishing alloforms. Check epitope information to avoid masking. Validate specificity in your model system [5]. |

| Protein A/G Beads | Binds the Fc region of antibodies to pull down antigen-antibody complexes. | Optimize choice: Protein A for rabbit IgG, Protein G for mouse IgG. Use bead-only controls to assess non-specific binding [5]. |

| Gateway Cloning System | Enables high-throughput transfer of ORFs into multiple expression vectors (e.g., for Y2H). | Essential for building isoform ORFeome libraries and functional screening [2] [6]. |

| IIIDB Database | Database of predicted human isoform-isoform interactions. | Provides a starting point for generating hypotheses about isoform-specific networks [3]. |

| Cytoscape | Open-source platform for visualizing and analyzing molecular interaction networks. | Allows integration of isoform-level data, functional annotations, and expression data. Highly extensible via plug-ins [8]. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This resource provides targeted support for researchers constructing protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) risk genes in neuronal models. The guidance is framed within the thesis that enhancing the cellular specificity and experimental precision of PPI maps is critical for translating genetic findings into mechanistic insights and therapeutic targets [9] [10].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My PPI network from generic cell lines (e.g., HEK293T) contains many interactions not found in neuronal-specific studies. How do I interpret this? A: This is a common issue highlighting the importance of cell-type context. While foundational maps in HEK293T cells can reveal over 1,800 PPIs with 87% novelty [11], interactions relevant to ASD pathophysiology are often specific to neuronal cell states. Interactions unique to non-neuronal lines may represent latent, non-functional, or developmentally irrelevant contacts. Prioritize interactions that are:

- Reproduced in neuronal models (e.g., iPSC-derived induced neurons) [9].

- Enriched for genetic signals from ASD, but not other psychiatric disorders, in neuronal transcriptomic data [11].

- Expressed in relevant human brain regions and developmental stages [12].

Q2: I am using iPSC-derived neurons for IP-MS. What are the critical quality control (QC) metrics to ensure reliable data? A: Robust QC is essential for specificity. Follow this protocol based on established work [9]:

- Cell Model Validation: Confirm expression of ASD index genes and proteins at your differentiation timepoint (e.g., week 3-4) via RNA-seq and immunoblotting.

- IP-MS Replicate Concordance: Calculate the log2 fold change (FC) correlation between technical or biological replicates. A correlation coefficient > 0.6 is typically required to pass QC.

- Target Enrichment: The bait protein must be significantly enriched in its own IP compared to control IPs (e.g., FDR ≤ 0.1).

- Interaction Thresholding: Define significant interactors using a combined threshold (e.g., log2 FC > 0 and FDR ≤ 0.1).

Q3: How can I distinguish direct from indirect interactors in my neuronal PPI network? A: Integrating computational predictions with experimental validation is key.

- Computational Prioritization: Use tools like AlphaFold-Multimer to predict direct physical interfaces between your bait protein and candidate interactors. High-confidence predictions can guide validation [11].

- Experimental Validation: Employ orthogonal methods like:

- Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC)

- FRET/BRET assays in live neurons.

- Targeted co-immunoprecipitation of truncated or domain-specific constructs to map interaction domains.

Q4: My gene set analysis identifies modules related to diverse functions (e.g., ion channels, immunity). How do I validate their relevance to ASD? A: Follow a multi-step functional characterization workflow [12]:

- Spatio-Temporal Expression: Use resources like the BrainSpan Atlas to test if genes in your module show enriched co-expression in specific brain structures (e.g., cortical layers) across critical developmental windows (prenatal to early postnatal).

- Network Extension: Extend your module by adding genes that are both spatio-temporally co-expressed in the brain with your core genes and physically interact with them (using databases like bioGRID). This identifies functionally convergent clusters.

- Genetic Enrichment: Test the extended module for enrichment of high-confidence ASD susceptibility genes from curated databases (e.g., SFARI Gene). Significant enrichment strengthens the module's pathological relevance.

Q5: How do I handle and visualize large, multi-omic PPI datasets effectively? A: Utilize specialized open-source libraries and frameworks [13].

- Network Integration & Visualization: Use Cytoscape (Desktop) or Cytoscape.js (Web) for integrating PPI networks with gene expression, variant, and annotation data.

- Custom Chart Creation: For publication-quality charts, use matplotlib (Python) or D3.js (JavaScript).

- Workflow Automation: Employ Python-based libraries like Bokeh for creating interactive dashboards to explore your network data.

Experimental Protocol Summaries

Protocol 1: Generating a Cell-Type-Specific PPI Network in Human Induced Neurons (iNs)

- Key Source: [9]

- Objective: Identify novel, neuron-specific interactions for ASD risk genes.

- Steps:

- Cell Differentiation: Generate homogeneous excitatory iNs from iPSCs using an inducible NGN2 protocol. Differentiate for 4-6 weeks.

- Bait Selection: Choose ASD index genes confirmed to be expressed as proteins in iNs at the differentiation timepoint.

- Interaction Proteomics: Perform immunoprecipitation (IP) with validated antibodies in biological duplicate (~15 million cells/replicate). Use isotype-matched IgG controls.

- Mass Spectrometry: Analyze IP eluates via LC-MS/MS (label-free or labeled).

- Data Analysis: Use a tool like Genoppi to calculate log2 FC and significance versus control. Apply QC filters (replicate correlation >0.6, bait enrichment FDR ≤ 0.1).

- Network Construction: Merge significant interactors (log2 FC > 0, FDR ≤ 0.1) from all baits to build the network.

Protocol 2: Functional Enrichment & Validation of a PPI Module

- Key Sources: [12] [11]

- Objective: Assess the neurobiological relevance of a cluster of interacting genes.

- Steps:

- Module Definition: Cluster your PPI network or gene set analysis results into functional modules (e.g., via hierarchical clustering).

- Brain Expression Profiling: Query the BrainSpan Atlas RNA-seq data. Statistically test for enriched expression of your module genes in specific brain regions and developmental periods.

- Interaction Validation: For key PPIs within the module, validate using orthogonal methods (e.g., co-IP in iN lysates, proximity ligation assays).

- Phenotypic Interrogation: Introduce patient-derived missense variants (e.g., via CRISPR in iPSCs) into key nodes of the module. Assess neuronal phenotypes in derived iNs or forebrain organoids (e.g., neurite outgrowth, synaptic morphology, electrophysiology) [11].

Table 1: Scale and Novelty of Recent ASD PPI Atlases

| Study Model | # of ASD Risk Genes (Baits) | # of PPIs Identified | % Novel Interactions (vs. Public DBs) | Key Validation Approach | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEK293T Cells | 100 | >1,800 | ~87% | AlphaFold prediction; Organoid/Xenopus phenotype | [11] |

| iPSC-Derived Excitatory Neurons | 13 | 1,021 | >90% | Replication in iNs (>91% by WB); Brain expression concordance | [9] |

| Comparative Insight: Neuronal models yield highly novel interactomes, underscoring the critical impact of cellular context on network topology. |

Table 2: Recommended QC Thresholds for Neuronal IP-MS Experiments

| QC Parameter | Threshold for Acceptance | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Replicate Log2 FC Correlation | > 0.6 | Ensures technical reproducibility of interaction profiles [9]. |

| Bait Protein Enrichment (FDR) | ≤ 0.1 | Confirms successful immunoprecipitation of the target. |

| Significant Interactor Threshold | Log2 FC > 0 & FDR ≤ 0.1 | Balanced threshold for identifying enriched proteins. |

| Overlap with Known Interactors (Optional) | - | Used to assess novelty; low overlap is expected in cell-specific studies. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Neuronal PPI Atlas Projects

| Item | Function & Specification | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| iPSC Line with Inducible NGN2 | Enables rapid, synchronous differentiation into excitatory neuron-like cells (iNs). | iPS3 line or equivalent [9]. |

| Validated IP-Competent Antibodies | For immunoprecipitation of ASD bait proteins. Must be validated for use in human neuronal lysates. | Commercial antibodies with confirmed reactivity in iN western/IP. |

| BrainSpan Atlas of the Developing Human Brain | Public RNA-seq resource to analyze spatio-temporal co-expression of gene modules [12]. | https://www.brainspan.org/ |

| bioGRID / InWeb Database | Public PPI database aggregator. Serves as a reference to calculate interaction novelty [12] [9]. | https://thebiogrid.org/ |

| SFARI Gene Database | Curated list of autism-associated genes. Used for enrichment analysis of PPI modules [12]. | https://gene.sfari.org/ |

| Genoppi Software | Computational pipeline for QC and analysis of IP-MS data [9]. | https://github.com/abdallahsophian/genoppi |

| Cytoscape Software | Platform for integrating, visualizing, and analyzing molecular interaction networks [13]. | https://cytoscape.org/ |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

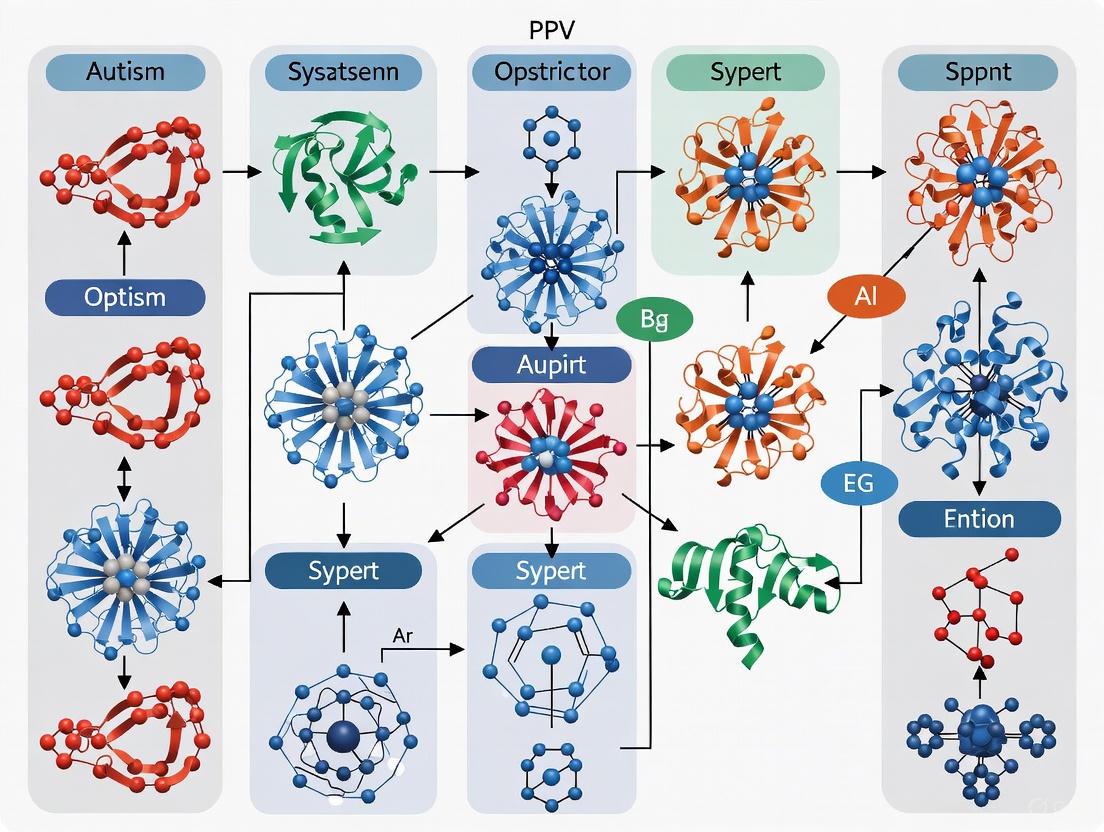

Diagram 1: Workflow for Building a Neuronal-Specific ASD PPI Atlas (100 chars)

Diagram 2: Example Convergent Pathways in a Neuronal PPI Network (99 chars)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is improving the specificity of Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks particularly important for autism research? In autism spectrum disorder (ASD), the interactions between genes and proteins are highly complex. Standard PPI networks often include false positives, which can obscure the true pathological mechanisms. Supervised analysis methods that contrast true complexes against random subgraphs can significantly improve specificity by identifying meaningful biological patterns, which is crucial for accurately pinpointing dysfunctional pathways in a heterogeneous condition like autism [14]. This enhanced specificity allows researchers to focus on biologically relevant interactions within pathways like Wnt and MAPK signaling.

Q2: What is the functional relationship between Wnt signaling and mitochondrial dynamics in neural cells? Wnt signaling plays a key role in regulating the balance between mitochondrial fission and fusion, a process critical for neuronal function and survival. This balance is essential for maintaining mitochondrial genome integrity, generating ATP, and controlling the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [15]. Dysregulation of this process can lead to impaired cellular homeostasis, which is increasingly implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental disorders.

Q3: How do MAPK pathways interact with mitochondria, and what are the consequences for cell signaling? MAPK enzymes, including ERK1/2, p38, and JNK, can directly and indirectly target mitochondria. They have been found to interact with the outer mitochondrial membrane and even translocate into the organelles [16]. These interactions influence critical processes such as energy metabolism and the initiation of cell death pathways like apoptosis and necrosis. This cross-talk represents a key convergence point where cellular stress signals can impact fundamental metabolic and survival pathways.

Q4: In the context of your research, what is a proven method to detect protein complexes more accurately from PPI data? The ClusterEPs method is an effective supervised approach. It uses Emerging Patterns (EPs)—contrast patterns that clearly distinguish true complexes from random subgraphs—to calculate a score predicting how likely a protein group is to form a complex [14]. This method addresses the limitation that true complexes are not always densely connected subgraphs, leading to more accurate predictions, especially for sparse complexes, and has demonstrated superior performance in cross-species prediction of human complexes using models trained on yeast data.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem 1: High False Positive Rate in PPI Network Analysis

Issue: Standard clustering methods for analyzing PPI networks often identify densely connected subgraphs, but many true biological complexes are not dense, leading to false positives and missed discoveries [14].

Solution:

- Apply Supervised Learning Methods: Utilize tools like ClusterEPs that employ Emerging Patterns (EPs) to differentiate true complexes from random subgraphs based on multiple topological and biological properties, not just density [14].

- Incorporate Additional Attributes: Combine network topology with biological insights such as functional annotations or cellular component data to improve prediction accuracy.

- Validate with Cross-Species Models: Train your prediction model on well-annotated PPI data from one species (e.g., yeast) to predict complexes in another (e.g., human), and then validate experimentally [14].

Problem 2: Inconsistent Results in Modulating Wnt Signaling

Issue: The role of Wnt signaling in pluripotent stem cells is diverse and context-dependent, leading to conflicting experimental outcomes, such as promoting self-renewal in some contexts and differentiation in others [15].

Solution:

- Systematically Document Conditions: Carefully record and control the pluripotent state (naïve vs. primed), culture conditions, and the specific mechanism of Wnt activation/inhibition (e.g., small molecule inhibitors like CHIR99021) [15].

- Monitor Downstream Effectors: Use reliable markers to confirm the intended pathway activation. For canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling, monitor the stability and nuclear translocation of β-catenin and the expression of target genes via TCF/LEF transcription factors [17] [15].

- Account for Pathway Crosstalk: Be aware that Wnt signaling closely interacts with other pathways like Notch, Hedgehog, and TGF-β. Simultaneous inhibition or activation of these pathways may be necessary to achieve the desired outcome [17].

Problem 3: Differentiating Canonical and Non-Canonical Wnt Pathway Activation

Issue: It can be challenging to determine which branch of the Wnt pathway is active in an experimental system, as different branches can have opposing effects.

Solution:

- Measure Specific Downstream Components:

- Canonical (Wnt/β-catenin): Assess the stability and nuclear localization of β-catenin and the transcriptional activity of TCF/LEF [17].

- Non-Canonical, Planar Cell Polarity (PCP): Monitor the activation of Rho/Rac small GTPases and JNK [17].

- Non-Canonical, Wnt/Ca2+: Measure intracellular calcium release and the activity of downstream targets like PKC, CAMKII, and NLK [17] [15].

- Use Specific Ligands and Inhibitors: Employ pathway-specific Wnt ligands (e.g., Wnt3a for canonical; Wnt5a for non-canonical) and pharmacological inhibitors to dissect the contributions of each branch.

Problem 4: Investigating MAPK-Mitochondria Cross-talk

Issue: The precise mechanisms of how MAPK signaling influences mitochondrial function are complex and can be difficult to dissect experimentally.

Solution:

- Employ Specific Assays: Utilize techniques to measure key mitochondrial parameters in response to MAPK modulation:

- ATP Production: Luciferase-based assays.

- ROS Levels: Fluorescent probes like DCFDA or MitoSOX.

- Calcium Flux: Calcium-sensitive dyes (e.g., Fluo-4) in conjunction with MAPK activity assays [16].

- Leverage Genetic Models: Use conditional knockout models or RNAi to selectively inhibit specific MAPKs (e.g., ERK1/2, p38, JNK) and observe the resultant effects on mitochondrial morphology and function [16] [18].

Summarized Quantitative Data

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Protein Complex Detection Methods on Yeast PPI Data This table summarizes the composite performance scores of various methods across five benchmark datasets, as reported in Scientific Reports [14]. A higher score indicates better overall performance.

| Method | Type | Dataset 1 | Dataset 2 | Dataset 3 | Dataset 4 | Dataset 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ClusterEPs | Supervised | 0.81 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.74 |

| ClusterONE | Unsupervised | 0.65 | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.59 |

| MCL | Unsupervised | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.52 | 0.54 | 0.56 |

| MCODE | Unsupervised | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.46 |

Table 2: Key MAPK Families and Their Roles in Cardiac Physiology and Pathology [16] This table outlines the primary functions of different MAPK subfamilies in the heart, illustrating their distinct roles.

| MAPK Subfamily | Primary Activators | Main Physiological Roles | Involvement in Cardiac Pathology |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERK1/2 | Mitogens, GPCR agonists | Cell growth, survival | Hypertrophic remodeling |

| p38 | Cellular stress, inflammatory cytokines | Inflammation, cell cycle regulation | Myocardial ischemia, apoptosis |

| JNK | Cellular stress, ROS | Apoptosis, cellular stress response | Ischemia/reperfusion injury |

| ERK5 | Mitogens, oxidative stress | Cell survival, angiogenesis | Protective signaling in hypertrophy |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Predicting Protein Complexes with ClusterEPs [14]

This protocol uses a supervised approach to identify protein complexes from a PPI network by leveraging contrast patterns.

- Input Data Preparation:

- Obtain a PPI network (e.g., from databases like DIP or STRING).

- Compile a set of known, high-confidence protein complexes as a positive training set (e.g., from MIPS or SGD).

- Feature Vector Construction:

- For each known complex and for a set of randomly generated subgraphs (negative controls), calculate a set of descriptive features. These may include:

- Topological features: Density, clustering coefficient, topological coefficients.

- Statistical features: Degree statistics, eigen values of the subgraph.

- For each known complex and for a set of randomly generated subgraphs (negative controls), calculate a set of descriptive features. These may include:

- Discover Emerging Patterns (EPs):

- Use a data mining algorithm to discover EPs—conjunctive patterns of features that occur frequently in the positive class (true complexes) but infrequently in the negative class (random subgraphs), or vice versa.

- Complex Identification:

- Define an EP-based clustering score that integrates the contributions of multiple EPs.

- Starting from seed proteins, iteratively grow candidate complexes by adding or removing proteins to maximize this clustering score.

- Validation:

- Compare predicted complexes against a gold-standard benchmark using metrics like precision, recall, and F1-score.

- Perform Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis to assess the biological relevance of novel predicted complexes.

Protocol 2: Assessing MAPK and Mitochondrial Cross-talk in Cellular Models [16]

This protocol outlines methods to investigate the functional relationship between MAPK signaling and mitochondrial function.

- Cell Stimulation/Inhibition:

- Treat cells (e.g., cardiomyocytes, neuronal cells) with specific activators (e.g., anisomycin for JNK) or inhibitors (e.g., SB203580 for p38) of the MAPK pathway of interest.

- MAPK Activity Assessment:

- Harvest cell lysates at appropriate time points post-treatment.

- Analyze MAPK activation (phosphorylation) via western blotting using phospho-specific antibodies against ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), p38 (Thr180/Tyr182), or JNK (Thr183/Tyr185).

- Mitochondrial Functional Assays:

- ATP Measurement: Use a luciferase-based ATP assay kit on cell lysates to quantify cellular ATP levels.

- ROS Measurement: Load cells with a fluorescent ROS indicator (e.g., CM-H2DCFDA) and measure fluorescence intensity via flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy.

- Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (ΔΨm): Use potentiometric dyes like JC-1 or TMRM to assess ΔΨm, a key indicator of mitochondrial health.

- Calcium Imaging: Use calcium-sensitive dyes (e.g., Fluo-4 AM) to monitor cytosolic and mitochondrial calcium fluxes in real-time.

- Data Correlation:

- Correlate the degree of MAPK activation with the changes observed in mitochondrial functional parameters to establish a functional link.

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: Wnt and MAPK Signaling Convergence on Mitochondria. This diagram illustrates the core canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway and its crosstalk with MAPK signaling, highlighting mitochondrial dysfunction as a key convergence point in pathological conditions.

Diagram 2: Supervised Protein Complex Detection Workflow. This workflow outlines the steps for the ClusterEPs method, which uses Emerging Patterns to improve the specificity of complex prediction in PPI networks.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating Wnt/MAPK/Mitochondria Pathways

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CHIR99021 | A potent and selective GSK-3β inhibitor. Activates canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling by stabilizing β-catenin [15]. | Used in "2i" media to maintain pluripotent stem cells in a naïve state. Dose-dependent effects should be carefully titrated. |

| SB203580 | A specific p38 MAPK inhibitor. Useful for dissecting the role of p38 in cellular processes and its crosstalk with other pathways [18]. | Confirms the involvement of p38 in observed phenotypes. Check for specificity against other MAPKs in your model system. |

| XAV939 | A tankyrase inhibitor that stabilizes Axin, a component of the β-catenin destruction complex, thereby inhibiting canonical Wnt signaling [17]. | A useful tool for specifically downregulating β-catenin-dependent transcription. |

| MitoSOX Red | A fluorogenic dye for the highly selective detection of superoxide in the mitochondria of live cells [16]. | Essential for measuring mitochondrial ROS, a key mediator of MAPK-mitochondria cross-talk. |

| JC-1 Dye | A cationic dye that accumulates in mitochondria and is used to measure mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) [16]. | A shift from red (J-aggregates) to green (monomers) fluorescence indicates mitochondrial depolarization. |

| ClusterEPs Software | A supervised software tool for predicting protein complexes from PPI networks using Emerging Patterns [14]. | Available online for detecting complexes, including sparse ones that traditional density-based methods miss. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the evidence that de novo missense variants contribute to Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)? Large-scale exome sequencing studies reveal that individuals with ASD have a significant enrichment of rare, de novo missense (dnMis) variants that are predicted to be damaging. While protein-truncating variants (PTVs) provide a stronger association signal, dnMis variants are more numerous, comprising over 60% of de novo variants in ASD cohorts. The signal for ASD risk is particularly strong for a subset of these dnMis variants that are predicted to disrupt specific protein-protein interactions (PPIs) [19] [20].

2. How can a missense variant disrupt a Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI)? A missense variant can disrupt a PPI through several mechanisms, primarily when the amino acid change occurs at a critical interface residue—the specific site where one protein binds to another. The mutation can:

- Alter the charge or shape of the binding site, preventing the partner protein from docking properly.

- Disrupt a phosphorylation site that is essential for the interaction, thereby abolishing a phosphorylation-dependent binding motif [21].

- Affect residues critical for maintaining the local or global protein structure, indirectly destabilizing the interaction interface.

3. Why is it important to study protein networks in a neuronal context? Many high-confidence PPIs relevant to neuropsychiatric disorders are cell-type-specific. A recent study creating a PPI network for ASD risk genes in human stem-cell-derived neurons identified over 1,000 interactions, approximately 90% of which were novel and not found in previous studies performed in non-neural cell lines. This highlights that crucial disease-relevant interactions can be missed without using biologically relevant cell models [1].

4. What is an "edgetic" perturbation? The traditional model for genetic variants is a "loss-of-function" (node-centric), where the entire protein is disabled. In contrast, an edgetic perturbation is an interaction-specific disruption. A variant may cause the loss or alteration of a specific protein interaction (an "edge" in the network graph) while leaving other functions of the protein intact. This offers a more precise mechanistic understanding of how a mutation leads to disease [22].

5. How can I functionally validate a candidate disruptive variant?

- Peptide-based Interaction Proteomics (e.g., PRISMA): This method uses synthetic wild-type, mutated, and phosphorylated peptides from a protein region of interest to pull down interacting proteins from neuronal lysates. By comparing the interactors, you can directly assess the variant's impact [21].

- Proximity-Labeling Proteomics in Neurons (e.g., BioID2): This technique allows for the mapping of PPIs in live, relevant cells (like primary neurons). You can express the wild-type and mutant versions of your protein of interest and identify changes in its immediate interaction neighborhood [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High False Positive Rates in Predicting Disruptive Variants

Problem: Your computational pipeline flags a large number of variants as potentially disruptive to PPIs, but experimental validation yields a low confirmation rate.

Solution:

- Refine Your Interface Predictions: Use a stringent, high-confidence threshold for predicting if a variant lies on a protein interaction interface. Tools like Interactome INSIDER can be used, but moving from a "Medium" to a "High" confidence threshold significantly improves specificity, reducing candidate lists while enriching for true positives [19].

- Integrate Structural Evidence: Whenever possible, utilize predicted or known protein structural data. Tools like AlphaMissense and PrimateAI-3D, which incorporate structural context, have demonstrated improved performance in evaluating missense variants [24].

- Employ a Composite Prediction Model: Combine multiple lines of evidence. One effective model first predicts if a variant is on an interaction interface and then evaluates its deleteriousness using a tool like PolyPhen-2. Only variants satisfying both criteria are considered high-confidence disruptive variants [19].

Issue: Identifying Convergent Pathways from a List of Disrupted Interactions

Problem: You have a list of proteins with disrupted interactions from your ASD study, but you are struggling to identify the key convergent biological pathways and prioritize new candidate genes.

Solution:

- Construct a "Disrupted Network": Connect all proteins involved in disrupted interactions (both the mutated protein and its direct interactors) to build a dedicated "ASD disrupted network." This network will be enriched for known ASD risk genes [19].

- Apply Network Propagation: Use algorithms like DAWN or DIMSUM that leverage network topology. These methods can implicate novel risk genes by identifying network modules that are densely connected to your initial seed genes, even if those new genes have weak direct genetic association signals [19] [22].

- Integrate Cell-Type-Specific Co-expression: Use single-cell RNA-seq data from the developing human brain to deconvolute your network analysis. By integrating your disrupted PPI network with gene co-expression data from specific neuronal cell types (e.g., excitatory neurons, inhibitory neurons), you can implicate genes in a cell-type-specific manner and uncover relevant biological pathways [19].

Quantitative Data on Disrupted Networks in ASD

Table 1: Enrichment of Disrupted PPIs in ASD Probands

| Metric | Value in ASD Probands | Value in Unaffected Siblings | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unique disruptive dnMis variants | 123 | 26 | Analysis of 6,542 dnMis variants [19] |

| Disrupted variant-PPI pairs | 524 | 94 | High-confidence HINT interactome [19] |

| Unique genes involved | 526 | Not Specified | Proteins with disrupted interactions [19] |

Table 2: Candidate Genes Implicated via Integrated Network Analysis

| Analysis Method | Cell Type | Significant Candidate Genes (FDR ≤ 0.05) | Novel Genes (~% of total) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAWN | Excitatory Neurons | 421 | ~60% |

| DAWN | Inhibitory Neurons | 413 | ~60% |

| DAWN | Neural Progenitor Cells | 281 | ~60% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Peptide-based Interaction Proteomics (PRISMA)

Purpose: To directly and quantitatively compare how wild-type, phosphorylated, and mutant peptide sequences interact with proteins from a complex lysate.

Methodology:

- Peptide Synthesis: Synthesize 15-mer peptides (with the residue of interest in the center) in three states: wild-type, mutant, and wild-type phosphorylated. Synthesize them on cellulose membranes using SPOT synthesis [21].

- SILAC Labeling: Grow HEK-293 or neuronal cells in three different isotopic conditions: "Light" (L), "Medium" (M), and "Heavy" (H) [21].

- Pull-down Assay: Incubate each of the three membrane copies with a different SILAC-labeled cell lysate.

- Sample Combination: Excise the peptide spots from the membranes and combine the pulldowns for the three different states of the same peptide (e.g., wild-type L, mutant M, phosphorylated H) into a single tube.

- Mass Spectrometry & Analysis: Identify and quantify the pulled-down proteins using high-resolution LC-MS/MS. Use the SILAC ratios to directly compare interaction strengths across the three peptide states [21].

Protocol 2: Neuron-Specific Proximity Labeling (BioID2)

Purpose: To map the protein interaction network of an ASD risk gene in a native neuronal environment.

Methodology:

- Construct Generation: Create BioID2 fusion constructs for your ASD risk gene (wild-type and mutant versions). BioID2 is an engineered promiscuous biotin ligase that biotinylates proximal proteins [23].

- Neuronal Transduction: Introduce these constructs into primary mouse neurons via lentiviral transduction [23].

- Proximity Labeling: Treat neurons with biotin to initiate labeling. The BioID2 fusion protein will biotinylate proteins within a ~10 nm radius.

- Affinity Purification: Lyse the neurons and capture the biotinylated proteins using streptavidin beads.

- Mass Spectrometry & Analysis: Identify the purified proteins via LC-MS/MS. Compare the interactors of the wild-type and mutant proteins to identify disrupted PPIs [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Reagent / Resource | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| HINT Database | A repository of high-quality, manually curated protein-protein interactions. | Provides a reliable background network for computational predictions [19] [22]. |

| Interactome INSIDER | Predicts protein-protein interaction interface residues from sequence. | Use a "High" confidence threshold to reduce false positives [19]. |

| BrainSpan Atlas | A transcriptome database of the developing human brain. | Essential for evaluating gene expression patterns during neurodevelopment [19]. |

| Stable Isotope Labeling (SILAC) | Allows for quantitative comparison of protein abundance across multiple samples by metabolic labeling. | Critical for the PRISMA method to compare wild-type, mutant, and phosphorylated peptide interactomes [21]. |

| BioID2 / APEX2 | Enzymes for proximity-dependent biotin labeling that mark nearby proteins for purification. | Enables mapping of PPIs in live, relevant cells like neurons, capturing transient interactions [23]. |

Network Perturbation Mechanisms

Network perturbation mechanisms

Experimental Workflow for PPI Analysis

Experimental workflow for PPI analysis

Next-Generation Tools: Advanced Proteomics and Deep Learning for Precision PPI Mapping

Troubleshooting Guides

Common BioID2 Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Problem: Low Biotinylation Efficiency

- Symptoms: Weak or no streptavidin-HRP signal on western blot; poor protein yield after streptavidin pull-down.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Insufficient Biotin Concentration: BioID2 requires biotin supplementation. Ensure culture medium contains at least 50 µM biotin [25]. For neurons, verify biotin can cross cell membranes.

- Short Biotin Incubation Time: BioID2 is faster than BioID but still requires several hours of biotin incubation for robust labeling. Test incubation times from 6-24 hours [26] [25].

- Impaired Ligase Activity: Fuse BioID2 to your protein of interest (POI) and validate its activity in a control cell line before using it in neurons or organoids.

Problem: High Background Labeling

- Symptoms: Excessive biotinylation in negative controls; numerous proteins identified in mass spectrometry that are likely non-specific.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Overexpression of BioID2 Fusion Protein: High expression levels can cause mislocalization and non-specific labeling. Use stable cell lines with low, physiological expression levels [25]. For neuronal work, consider using inducible expression systems.

- Endogenous Biotinylated Proteins: Mitochondrial carboxylases can create strong background signals. For C. elegans, genetic tagging of these carboxylases allows their removal [26]. Consider similar strategies or antibody-based depletion.

- Optimize Biotin Concentration and Time: While TurboID requires minutes, BioID2 requires hours. Overly long incubations can increase background. Titrate biotin concentration and incubation time [26].

Problem: Altered Subcellular Localization of Fusion Protein

- Symptoms: The BioID2-POI fusion localizes differently from the endogenous protein or GFP-tagged controls.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Tag Interferes with Protein Function: The ~35 kDa BioID2 may disrupt protein folding, interactions, or post-translational modifications. Test both N- and C-terminal fusions in parallel [25].

- Validate Fusion Protein Function: Compare localization of the BioID2 fusion to endogenous protein by immunofluorescence. If possible, test if the fusion protein can rescue a loss-of-function phenotype [25].

Problem: Poor Viability in Neurons/Organoids

- Symptoms: Cell death or degraded morphology after BioID2 expression and/or biotin treatment.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Biotin Toxicity: While less cytotoxic than H₂O₂ used in APEX, high biotin concentrations may affect some cells. Titrate to the lowest effective concentration [26].

- Proteotoxicity of Fusion Protein: Misfolded fusion proteins can cause stress. Use inducible expression to minimize prolonged exposure and confirm fusion protein does not aggregate.

Protocol-Specific Troubleshooting for Neuronal Systems

Neuronal Transfection and Expression

- Challenge: Low efficiency of transfection in mature neurons.

- Solution: Use lentiviral or AAV delivery for higher infection efficiency and stable expression. For organoids, consider electroporation or viral transduction at early stages.

Capturing Transient Synaptic Interactions

- Challenge: Synapses are characterized by highly transient protein-protein interactions (PPIs) that may be missed [26].

- Solution: Ensure biotin incubation times are appropriate for the dynamics of the process being studied. For very fast interactions, consider TurboID, but be aware of its potential for higher background [26].

Specificity in Dense Networks

- Challenge: In neuronal cultures and organoids, processes from different cells are densely packed. It can be hard to determine which cell the biotinylated proteins came from.

- Solution: Use cell-type-specific promoters (e.g., synapsin for neurons, GFAP for astrocytes) to restrict BioID2 expression. The labeling radius of BioID2 is ~10-15 nm, which helps restrict labeling to proteins very close to the fusion protein [26] [25].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of using BioID2 instead of BioID or TurboID in neuronal models?

A1: The choice of proximity ligase involves trade-offs. BioID2, derived from Aquifex aeolicus, offers several specific benefits for neuronal research [26] [25]:

- Smaller Size: BioID2 is approximately one-third smaller than original BioID, which minimizes steric interference and can enhance accurate localization of fusion proteins, crucial for precise synaptic studies.

- Reduced Biotin Requirement: It requires less biotin to achieve efficient labeling, which can be beneficial in systems where biotin supplementation is challenging.

- Moderate Labeling Time: It is faster than BioID but slower than TurboID. This can be a useful intermediate for capturing interactions that occur over several hours without the extreme catalytic activity of TurboID, which can cause background and cell stress in sensitive neurons.

Q2: How can I improve the specificity of my BioID2 results to distinguish true interactors in the context of autism-related PPI networks?

A2: Enhancing specificity is critical for identifying meaningful PPIs in complex polygenic disorders like ASD.

- Implement Peptide-Level Enrichment: Instead of standard protein-level enrichment after streptavidin pull-down, use peptide-level enrichment. This allows direct identification of the biotinylated lysine residue, providing strong evidence that the protein was a direct labeling target and not a co-purifying contaminant [26].

- Use Appropriate Controls: Always include a BioID2-only control (the ligase expressed without your POI) to identify proteins that bind non-specifically to the ligase or streptavidin beads [25]. For compartment-specific studies, use a control with BioID2 targeted to the same subcellular location but without the POI.

- Apply Quantitative Proteomics: Incorporate tandem mass tag (TMT) labeling to enable quantitative comparisons between your BioID2-POI experiment and controls. This allows statistical ranking of candidates based on fold-change, helping to filter out background [26].

- Network Analysis: Integrate your BioID2 hits with known protein interaction networks and ASD risk gene sets. Proteins that cluster with known ASD-related proteins or pathways are higher-confidence candidates for further study [27] [28].

Q3: What is the typical labeling radius of BioID2, and what does this mean for mapping protein complexes at the synapse?

A3: The labeling radius of BioID2 is estimated to be about 10-15 nm [25]. This is highly relevant for synaptic studies because:

- It is small enough to provide sub-synaptic resolution, potentially differentiating between proteins in the pre-synaptic active zone, post-synaptic density, or synaptic cleft.

- It can help map the constituency of specific protein complexes. However, if your POI is part of a large complex, an extended flexible linker can be fused to BioID2 to increase the labeling range and map the entire complex [25].

Q4: My protein of interest is a membrane-associated synaptic adhesion molecule. Are there special considerations for applying BioID2?

A4: Yes, BioID2 is particularly well-suited for studying membrane proteins, which is a key advantage over traditional immunoprecipitation-based methods [26].

- Native Environment: BioID2 works in living cells, preserving membrane integrity and the native environment of your membrane protein.

- Capturing Weak/Transient Interactions: It can identify weak or transient interactions that might be lost during the detergent lysis required for co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) [26] [25].

- Identifying Proximal Proteins: It will biotinylate not only direct binding partners but also other proteins nearby in the same membrane microdomain or synaptic complex, providing a more comprehensive view of its molecular environment.

Q5: How can I integrate BioID2 proteomics data with other 'omics' data to gain deeper insights into autism pathways?

A5: Integration with multi-omics data is a powerful strategy for understanding complex disorders.

- Transcriptomic Integration: Overlay your BioID2-derived PPI network with gene co-expression modules from ASD brain transcriptome data. This can reveal if your PPIs are enriched in modules of co-expressed genes that are dysregulated in ASD [27] [28].

- Genetic Risk Data: Cross-reference your proximal protein list with databases of high-confidence ASD risk genes (e.g., from SFARI). Proteins that are both proximal to your POI and encoded by ASD risk genes are high-value targets.

- Drug Repurposing: Use network-based approaches, as demonstrated in recent studies, to connect your PPI network to drug-gene interactions. This can identify potential therapeutic compounds that might modulate the network you have mapped [28].

Quantitative Data Comparison

Comparison of Proximity Labeling Enzymes

Table: Key Characteristics of Major Proximity Labeling Enzymes

| Feature | BioID | BioID2 | APEX/APEX2 | TurboID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | E. coli BirA | A. aeolicus BirA | Ascorbate Peroxidase | Engineered from BioID |

| Size | ~35 kDa | ~27 kDa (Smaller) | ~28 kDa | ~35 kDa |

| Labeling Radius | ~10 nm | ~10-15 nm | ~10-20 nm | <10 nm |

| Typical Labeling Time | 18-24 hours | Several hours | 1-30 minutes | 5-30 minutes |

| Primary Substrate | Biotin | Biotin | Biotin-phenol + H₂O₂ | Biotin |

| Key Advantage | Pioneering method; well-established | Smaller size; reduced biotin need | Very fast; works in more compartments | Extremely fast labeling |

| Key Disadvantage | Slow labeling | Slower than TurboID/APEX | H₂O₂ can be cytotoxic | High background; can be cytotoxic |

| Best for Neurons/Organoids | Good for slow processes, less cytotoxicity | Good balance of size, speed, and specificity | Excellent for capturing rapid dynamics | Useful for very rapid processes, but toxicity is a concern |

Experimental Workflow & Protocol

Detailed Protocol for BioID2 in Human Neurons

Step 1: Plasmid Design and Cloning

- Clone your gene of interest (GOI) into a BioID2 fusion expression vector. Test both N-terminal and C-terminal fusions if there is no prior knowledge.

- For neuronal expression, use a vector with a neuronal promoter (e.g., hSynapsin1). Include a fluorescent tag (e.g., mCherry) for tracking expression.

- Critical Control: Generate a "BioID2-only" construct for background subtraction [25].

Step 2: Delivery into Neuronal Systems

- For Primary Neurons: Use low-division lentivirus for high-efficiency transduction. Perform transduction at DIV 2-4 to allow robust expression and localization.

- For iPSC-Derived Neurons: Utilize lentivirus or electroporation of neural progenitors before differentiation.

- For Cerebral Organoids: Deliver constructs via electroporation at early stages (e.g., day 10-20) or use lentiviral transduction.

Step 3: Expression Validation and Biotinylation

- Confirm proper subcellular localization of your BioID2 fusion protein using immunofluorescence against the tag and/or endogenous protein.

- Induce biotinylation by adding biotin to the culture medium to a final concentration of 50 µM. Incubate for a predetermined time (e.g., 6-24 hours) [25].

Step 4: Cell Lysis and Streptavidin Pull-down

- Wash cells with cold PBS and lyse using RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors.

- Optional Sonication: Sonicate lysates to shear DNA and reduce viscosity.

- Clarify lysates by centrifugation.

- Incubate the supernatant with pre-washed streptavidin-coated beads (e.g., Streptavidin Sepharose) for 2-4 hours at 4°C with rotation [25].

Step 5: Washing and Elution

- Wash beads stringently with a series of buffers (e.g., RIPA, high-salt buffer, and urea buffer) to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- For mass spectrometry analysis:

- On-bead digestion is standard. Wash beads with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, then digest with trypsin.

- For western blot analysis: Elute proteins by boiling beads in SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing 2-4 mM biotin and 1-2% SDS.

Workflow Diagram for BioID2 Experiment

Specificity Enhancement Strategy

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for BioID2 Experiments in Neuroscience

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples & Details | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pDisplay-BioID2, pcDNA3.1-BioID2, custom lentiviral vectors with neuronal promoters (hSyn, CaMKIIa). | Delivery and controlled expression of the BioID2 fusion protein. |

| Biotin | D-Biotin, prepared as a 1-50 mM stock solution in PBS or DMSO, sterile-filtered. | Substrate for the BioID2 ligase; added to culture medium to induce biotinylation. |

| Streptavidin Beads | Streptavidin Sepharose High Performance beads; Magnetic Streptavidin beads. | Affinity capture of biotinylated proteins from cell lysates. |

| Lysis Buffer | RIPA Buffer, supplemented with protease inhibitors (e.g., PMSF, Complete Mini EDTA-free). | Cell lysis while preserving protein complexes and biotin tags. |

| Wash Buffers | Low-Salt (e.g., RIPA), High-Salt (e.g., 1 M KCl), Denaturing (e.g., 2 M Urea). | Remove non-specifically bound proteins after pull-down. |

| Detection Reagents | Streptavidin-HRP for western blot; Streptavidin-conjugated fluorescent dyes (e.g., Alexa Fluor) for microscopy. | Visualization of biotinylation efficiency and localization. |

| Cell Type | HEK293T (for virus production), Primary rodent/human neurons, iPSC-derived neurons, Cerebral organoids. | Model systems for validating and performing the BioID2 experiment. |

| Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS/MS systems; Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) reagents for multiplexing. | Identification and quantification of biotinylated proteins. |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Hub

This guide addresses common technical challenges faced by researchers employing Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), and Transformers for Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) prediction, specifically within the context of refining specificity in PPI networks for autism research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My graph-structured PPI data is highly variable in size. How can I batch it for efficient training in a GNN?

A: Standard batching for grid-like data (e.g., images) is not directly applicable to graphs with variable nodes and edges. Use a framework like PyTorch Geometric, which provides a DataLoader that creates a single large, disconnected graph from a batch of smaller graphs [29]. This is memory-efficient and preserves the structure of each individual PPI network. Ensure your readout (pooling) function for graph-level predictions operates on a per-graph basis using batch assignment vectors.

Q2: When converting fMRI data to a brain connectivity graph for autism prediction, what is a robust method to define edges (connections)? A: A common and validated method is to use a brain atlas for parcellation and then calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient of time-series activity between each pair of regions [30]. This results in a correlation matrix, which serves as a weighted adjacency matrix for your graph. Thresholding this matrix (e.g., keeping only correlations above a certain absolute value) can create a sparse, unweighted graph. The choice of atlas and threshold significantly impacts results and should be justified per your research hypothesis [29].

Q3: For node-level tasks on a PPI network (e.g., predicting protein function), my GNN's performance saturates quickly with depth. Why? A: This is likely due to the oversmoothing problem, where node features become indistinguishable after too many message-passing layers. For PPI networks, which are often "small-world," 2-3 GCN layers are typically sufficient [30]. Consider using architectures with residual connections, skip connections, or initial layers that are not updated. Alternatively, explore attention-based models like GATs, which can weigh neighbor importance differently.

Q4: How can I integrate non-graph features (e.g., protein sequence data) into a GNN model for PPI prediction? A: Use the non-graph features as initial node features. For protein nodes, this could be embeddings from a language model (Transformer) trained on sequences. The GNN's message-passing layers will then propagate and transform these features based on the network topology. This combines structural (graph) and intrinsic (sequence) information. For graph-level predictions, ensure your pooling method (e.g., global mean pooling) effectively aggregates these enriched node embeddings.

Q5: My Transformer model for sequence-based PPI prediction is overfitting on a limited dataset. What are specific mitigations? A: Beyond standard regularization (dropout, weight decay), consider:

- Transfer Learning: Initialize your model with weights from a large pre-trained protein language model (e.g., ESM, ProtBERT) and fine-tune on your specific PPI task.

- Data Augmentation: For protein sequences, use legitimate biological variations like adding point mutations that are predicted to be neutral or using multiple sequence alignments.

- Simpler Architecture: A shallow CNN might generalize better than a deep Transformer on very small datasets. Perform architecture searches.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Building a GNN for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Classification from Functional Connectivity Graphs Objective: To classify subjects as ASD or neurotypical using fMRI-derived brain graphs [30] [29].

- Data Preprocessing: Use the ABIDE dataset. Preprocess fMRI scans (slice-timing correction, motion realignment, normalization). Apply a brain atlas (e.g., AAL, Harvard-Oxford) to extract average time-series for N regions of interest (ROIs).

- Graph Construction: For each subject, compute an N x N Pearson correlation matrix between all ROI time-series. Apply an absolute value threshold (e.g., top 20% of connections) to obtain a sparse, unweighted adjacency matrix A. Node features can be set to the ROI time-series statistics or set to a constant [30].

- Model Architecture (2-Layer GCN):

GCNConv(in_channels, hidden_dim) -> ReLU -> DropoutGCNConv(hidden_dim, embedding_dim)- Global mean pooling layer.

- Linear layer (

embedding_dim -> num_classes).

- Training: Use cross-entropy loss with Adam optimizer. Implement k-fold cross-validation (e.g., k=3) [29]. Monitor accuracy and F1-score [30].

Protocol 2: Regression GNN (RegGNN) for Predicting Cognitive Scores from Connectivity Objective: To predict continuous cognitive scores (e.g., IQ) from brain connectomes [29].

- SPD Processing: Recognize that correlation matrices lie on the Symmetric Positive Definite (SPD) manifold. Use geometric tools (e.g., from

Morphomatics) to process them in their native space, preserving topological properties. - Sample Selection: Implement the modular sample selection method described in RegGNN to choose training samples with the highest expected predictive power for the regression task.

- Model & Training: The RegGNN architecture incorporates SPD-aware layers. Use Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss. The training loop includes the sample selection module. Configuration parameters (epochs, learning rate, dropout) are set via a config file [29].

Protocol 3: Contrast Ratio Validation for Experimental Visualizations Objective: Ensure all diagrams and charts in publications meet accessibility (WCAG) and readability standards [31] [32] [33].

- Define Elements: Identify foreground (text, lines, symbols) and background colors in each diagram.

- Calculate Ratio: Use the formula:

(L1 + 0.05) / (L2 + 0.05), where L1 is the relative luminance of the lighter color and L2 is the darker. Use online checkers (e.g., WebAIM) [33] for verification. - Apply Thresholds:

- Remediation: If contrast fails, adjust colors using the provided palette. Explicitly set

fontcolorin Graphviz to ensure contrast againstfillcolor[35].

Table 1: Model Performance on Neuroimaging Classification/Regression Tasks

| Model Architecture | Task | Dataset | Key Metric | Reported Score | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Layer GCN [30] | ASD vs. Control Classification | ABIDE (fMRI) | Accuracy | 66% | Comparable to similar architectures. |

| 2-Layer GCN [30] | ASD vs. Control Classification | ABIDE (fMRI) | F1-Score | 0.75 | Indicates a balance between precision and recall. |

| RegGNN with Sample Selection [29] | Full-Scale IQ Prediction | ASD Cohort | Performance | Outperformed baselines (CPM, PNA) | Specific metrics not listed in excerpt. |

| RegGNN with Sample Selection [29] | Verbal IQ Prediction | ASD Cohort | Performance | Outperformed baselines (CPM, PNA) | Specific metrics not listed in excerpt. |

| RegGNN [29] | IQ Prediction | Neurotypical Subjects | Performance | Competitive performance achieved | Using 3-fold cross-validation. |

Table 2: WCAG 2.2 Level AA Color Contrast Requirements [31] [32] [33]

| Content Type | Size / Weight Requirement | Minimum Contrast Ratio | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Text | Less than 18.66px or not bold | 4.5:1 | Applies to most body text. |

| Large Text | At least 18.66px OR at least 14pt & bold | 3:1 | "Bold" is CSS font-weight: 700 or greater [32]. |

| Graphical Objects & UI Components | Any size (icons, charts, form borders) | 3:1 | WCAG 2.1 Success Criterion 1.4.11 [34]. |

| Enhanced (Level AAA) Text | Normal Text | 7:1 | Stricter guideline for higher compliance [31]. |

| Enhanced (Level AAA) Text | Large Text | 4.5:1 | Stricter guideline for higher compliance [31]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for PPI & Neuroimaging ML Research

| Item | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| PyTorch Geometric [29] | A library for deep learning on graphs. Provides fast GNN layers, data handling for graphs, and standard benchmarks. | Essential for implementing GCN, GAT, and other GNN models. |

| ABIDE Dataset | A publicly available collection of fMRI data from individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder and controls. | Primary data source for neuroimaging studies in autism [30]. |

| Brain Atlas | A template for partitioning the brain into distinct regions (ROIs). | Necessary to construct nodes for brain connectivity graphs (e.g., AAL, Craddock) [30]. |

| ESM / ProtBERT | Large-scale pre-trained Transformer models for protein sequences. | Provides powerful initial embeddings for protein nodes, integrating sequence information into PPI graphs. |

| WebAIM Contrast Checker [33] | An online tool to verify color contrast ratios against WCAG guidelines. | Critical for creating accessible and readable scientific figures and interfaces. |

| Graphviz (DOT) | A graph visualization software. Used here to generate standardized, reproducible diagrams for workflows and pathways. | Diagrams must adhere to color contrast rules for readability. |

| Morphomatics / SPD Geom | Libraries for geometric processing on manifolds like Symmetric Positive Definite (SPD) matrices. | Used in advanced GNNs (e.g., RegGNN) that process brain connectomes in their native geometric space [29]. |

Mandatory Visualizations: Workflows & Architectures

Title: GNN Model Workflow for PPI Network Analysis

Title: Pipeline from fMRI Scans to Brain Connectivity Graph

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks are fundamental for understanding cellular processes, and their accurate prediction is critical for identifying therapeutic targets for complex disorders like autism spectrum disorder (ASD). However, current computational tools often fall short in modeling the natural hierarchical organization of these networks and the unique pairwise interaction patterns between proteins. The HI-PPI model addresses these limitations by integrating hyperbolic geometry and interaction-specific learning, offering a novel framework that significantly enhances the accuracy and biological interpretability of PPI predictions. For ASD research, where risk genes often converge on specific neuronal pathways, this improved specificity can help pinpoint central players and convergent biological mechanisms with greater reliability [36] [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using hyperbolic space over traditional Euclidean space for PPI network analysis?

Hyperbolic space naturally represents hierarchical relationships. In HI-PPI, the distance of a protein's embedding from the origin in hyperbolic space directly reflects its position in the network's hierarchy, helping to identify central hub proteins and peripheral elements. This provides a more biologically accurate representation of PPI networks, which exhibit strong hierarchical organization ranging from molecular complexes to functional modules and cellular pathways [36].

Q2: Our lab focuses on ASD. How can HI-PPI's hierarchical insights help identify key risk genes?

HI-PPI can illuminate the hierarchical level of proteins within a neuronal PPI network. Proteins that are central in the hierarchy and interact with multiple ASD risk gene products are strong candidates for being key mediators or novel risk genes themselves. For example, in a study of ASD risk genes in human neurons, insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins (IGF2BP1-3) were found to be highly interconnected, each interacting with at least five index risk proteins, suggesting they are major players in convergent biological pathways for ASD risk [1].

Q3: What are the minimum data requirements to run the HI-PPI model on a new set of proteins?

HI-PPI requires both sequence and structural data for robust feature extraction.

- Sequence Data: Amino acid sequences for each protein.

- Structural Data: Ideally, 3D protein structures (e.g., PDB files) to construct contact maps based on the physical coordinates of residues. If experimental structures are unavailable, high-confidence predicted structures should be used [36] [37].

Q4: During training, we encounter an "out of memory" error. What are the most effective parameters to adjust?

To mitigate memory issues, consider the following adjustments:

- Reduce the batch size (

-b). This is often the most effective first step. - Decrease the number of graph layers (

-ln). This reduces the complexity of the model. - Shorten the sequence padding length (

-L) if the sequences in your dataset are unnecessarily long. - Use the provided

-cudaflag to ensure computation is offloaded to a GPU if available [37].

Troubleshooting Guide

Installation and Data Preparation

| Problem | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| "Structure feature file not found" error. | Pre-generated structure features were not downloaded or are in the wrong directory. | Download and unzip the pre-generated features for SHS27K and SHS148K into your project folder. Ensure the path in your command is correct [37]. |

| Failure to generate custom structure features. | Incorrect file paths or missing PDB files. | Use the command python3 main.py -m data -i1 [sequence file] -i2 [interaction file] -sf [pdb folder] -o [output name]. Double-check that the -sf directory contains a PDB file for each protein [37]. |

| Poor performance on a custom ASD-related PPI dataset. | The model may be overfitting to the training data. | Utilize the BFS or DFS data splitting strategy (-m bfs or -m dfs) during training to better simulate real-world prediction scenarios and improve model generalization [36] [37]. |

Model Training and Execution

| Problem | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Model performance is lower than reported in benchmarks. | Suboptimal hyperparameters or insufficient feature fusion. | Experiment with the feature fusion option (-ff), try different loss functions (-Loss), and adjust the number of training epochs (-e). Validate your data preprocessing steps [37]. |

| CUDA "out of memory" error during training. | Batch size or model is too large for GPU memory. | Decrease the batch size (-b). If the problem persists, reduce the model complexity by lowering the number of graph layers (-ln) or the hidden layer dimension (-hl) [37]. |

| Inability to reproduce results from the HI-PPI paper. | Differences in data splitting or evaluation strategy. | Strictly adhere to the BFS or DFS splitting strategies outlined in the paper. Use the same benchmark datasets (SHS27K, SHS148K) and evaluation metrics (Micro-F1, AUPR, AUC, Accuracy) for a fair comparison [36]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

HI-PPI Model Architecture and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of the HI-PPI model, from feature extraction to final prediction.

Key Experimental Steps:

Feature Extraction:

- Input: For each protein, provide its 3D structure (to generate a residue contact map) and its amino acid sequence.

- Process: Encode structural features using a pre-trained heterogeneous graph encoder and a masked codebook. Encode sequence features based on physicochemical properties.

- Output: Concatenate the structural and sequence feature vectors to form the initial representation for each protein [36].

Hierarchical Embedding in Hyperbolic Space:

- Process: Pass the initial protein representations through a Hyperbolic Graph Convolutional Network (GCN). This layer iteratively updates each protein's embedding by aggregating information from its neighbors in the PPI network within hyperbolic space.

- Output: A hyperbolic embedding for each protein. The distance from the origin of this space quantitatively reflects the protein's level in the network hierarchy, aiding in the identification of hub proteins [36].

Interaction-Specific Prediction:

- Process: For a given protein pair, take their hyperbolic embeddings and compute their Hadamard product. Pass this product through a gated interaction network. This gating mechanism dynamically controls the flow of cross-interaction information, capturing the unique patterns for that specific pair.

- Output: A final score predicting the likelihood of interaction [36].

Protocol for Validating HI-PPI Predictions in an ASD Context

This protocol outlines how to experimentally test HI-PPI predictions related to autism spectrum disorder, based on methodologies from recent literature.

Key Experimental Steps:

- Cell Model Generation: Use human stem cells to generate neurogenin-2 induced excitatory neurons (iNs). This provides a cell-type-specific context crucial for neuronal PPIs, as ~90% of interactions found in neurons may be missed in non-neural cell lines [1].

- Interaction Pull-Down: Perform immunoprecipitation (IP) of the index protein (one of the proteins in the HI-PPI predicted pair) from the neuronal cell lysates.

- Interaction Identification: Identify co-precipitating proteins using liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Validate key interactions through Western blotting [1].

- Network Integration and Analysis: Integrate the confirmed interactions into an expanding ASD PPI network. Analyze the network to identify proteins that, like IGF2BP1-3, interact with multiple known ASD risk genes, marking them as high-priority candidates for further functional studies [1].

Performance Benchmarking