Dynamic Modeling of Metabolic Networks: Protocols for Biomedical Research and Therapeutic Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to dynamic modeling of metabolic networks, bridging foundational concepts with advanced applications.

Dynamic Modeling of Metabolic Networks: Protocols for Biomedical Research and Therapeutic Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to dynamic modeling of metabolic networks, bridging foundational concepts with advanced applications. It explores the critical need for dynamic frameworks to capture temporal metabolic shifts, contrasting them with steady-state approaches. The content details practical methodologies including constraint-based and kinetic modeling, hybrid techniques like HCM-FBA, and dynamic optimization for strain engineering. It further addresses common computational and data challenges, alongside validation strategies using metabolomic data and model comparative analysis. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this protocol-oriented resource aims to equip readers with the knowledge to build, simulate, and validate dynamic metabolic models for applications in biotechnology and disease research.

Foundations of Metabolic Network Modeling: From Static Reconstructions to Dynamic Frameworks

Metabolic networks are complex systems that represent the complete set of biochemical reactions within a cell, connecting genes, proteins, and metabolites into an interconnected network. These networks serve as the backbone of functional genomics, providing a comprehensive framework for analyzing metabolic processes that occur within cellular systems [1]. The reconstruction and modeling of these networks have become indispensable tools in systems biology, enabling researchers to correlate genomic information with molecular and physiological outcomes [2].

Metabolic network reconstruction involves creating a structured knowledge base that abstracts pertinent information on biochemical transformations within specific target organisms [3]. These reconstructions integrate genomic data with biochemical knowledge to build computational models that can predict cellular behavior under various conditions. The process has evolved significantly since the first genome-scale metabolic model was generated for Haemophilus influenzae in 1995, with numerous reconstructions now available for organisms across all domains of life [2].

The value of metabolic network modeling extends across multiple disciplines, from basic microbial physiology to biomedical research and metabolic engineering. These models provide a mathematical framework for interpreting high-throughput omics data, predicting metabolic fluxes, identifying key regulatory nodes, and generating testable biological hypotheses [1]. For drug development professionals, metabolic models offer opportunities to understand metabolic adaptations in disease states and identify potential therapeutic targets.

Metabolic Network Reconstruction Protocol

Reconstructing a metabolic network is a meticulous process that transforms genomic annotations into a structured, mathematical representation of cellular metabolism. This process follows established protocols to ensure the production of high-quality, predictive models [3]. The reconstruction journey typically spans from several months for well-studied bacterial genomes to years for complex eukaryotic organisms, as demonstrated by the metabolic reconstruction of human metabolism, which required approximately two years and six researchers [3].

The reconstruction process consists of four major stages, each with specific objectives and quality control checkpoints. The initial stage involves creating a draft reconstruction from genomic data, followed by manual curation and refinement to ensure biological accuracy. The refined reconstruction is then converted into a computational format, and finally evaluated and debugged through comparison with experimental data [3] [2]. This protocol ensures the resulting model faithfully represents the organism's metabolic capabilities.

Stage 1: Draft Reconstruction

The first stage transforms genomic annotations into an initial metabolic network draft. This process begins with obtaining the most recent genome sequence and annotation for the target organism, as the quality of the reconstruction directly depends on the accuracy of these foundational data [3].

Step 1: Genome Annotation Retrieval

- Download the complete genome sequence and annotation from reliable databases

- Ensure annotations include gene identifiers, functional assignments, and evidence codes

- Document the annotation source and version for reproducibility

Step 2: Identification of Candidate Metabolic Functions

- Extract metabolic genes from the annotation using keywords or Gene Ontology categories

- Map identified genes to enzymatic functions using Enzyme Commission numbers

- Retrieve corresponding biochemical reactions from databases like KEGG and BRENDA

- Compile initial reaction list, recognizing it will contain false positives and gaps [3]

The draft reconstruction serves as a starting point for refinement, representing a collection of genome-encoded metabolic functions that require extensive curation. Automated tools such as Pathway Tools or ModelSEED can accelerate this stage, but cannot replace manual curation [3] [2].

Stage 2: Manual Reconstruction Refinement

This critical stage transforms the automated draft into a biologically accurate reconstruction through iterative curation. For each gene and reaction entry, researchers must ask two fundamental questions: "Should this entry be here?" and "Is there an entry missing?" [3].

Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) Association

- Establish accurate relationships between genes, proteins, and reactions

- Implement Boolean logic representing protein complex formation and isozymes

- Include confidence levels for each assignment based on experimental evidence

Reaction Curation

- Verify reaction stoichiometry and directionality under physiological conditions

- Confirm cofactor specificity and energy requirements

- Assign subcellular compartmentalization for eukaryotic organisms

- Set appropriate bounds for reaction fluxes based on thermodynamic constraints

Gap Analysis and Resolution

- Identify metabolic gaps where reactants are produced without consumption or vice versa

- Resolve gaps through literature mining, phylogenetic analysis, or experimental validation

- Add transport reactions for metabolite exchange between compartments and with extracellular environment

This stage relies heavily on organism-specific literature and databases. For less-studied organisms, information from phylogenetic neighbors may be used, but model predictions must be carefully validated against available physiological data [3].

Stage 3: Mathematical Representation and Network Validation

The curated reconstruction is converted into a mathematical format suitable for computational analysis. The core component is the stoichiometric matrix S, where rows represent metabolites and columns represent reactions, with elements Sᵢⱼ indicating the stoichiometric coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j [4].

Model Validation Procedures

- Test network connectivity and mass balance for each metabolite

- Verify production of essential biomass precursors and energy currencies

- Validate model predictions against experimental growth phenotypes

- Assess gene essentiality predictions using knockout studies

- Compare simulated metabolic capabilities with literature data

Debugging Strategies

- Identify blocked reactions that cannot carry flux under any condition

- Resolve energy-generating cycles that violate thermodynamic constraints

- Correct network gaps that prevent synthesis of essential metabolites

- Adjust reaction directionality based on thermodynamic calculations

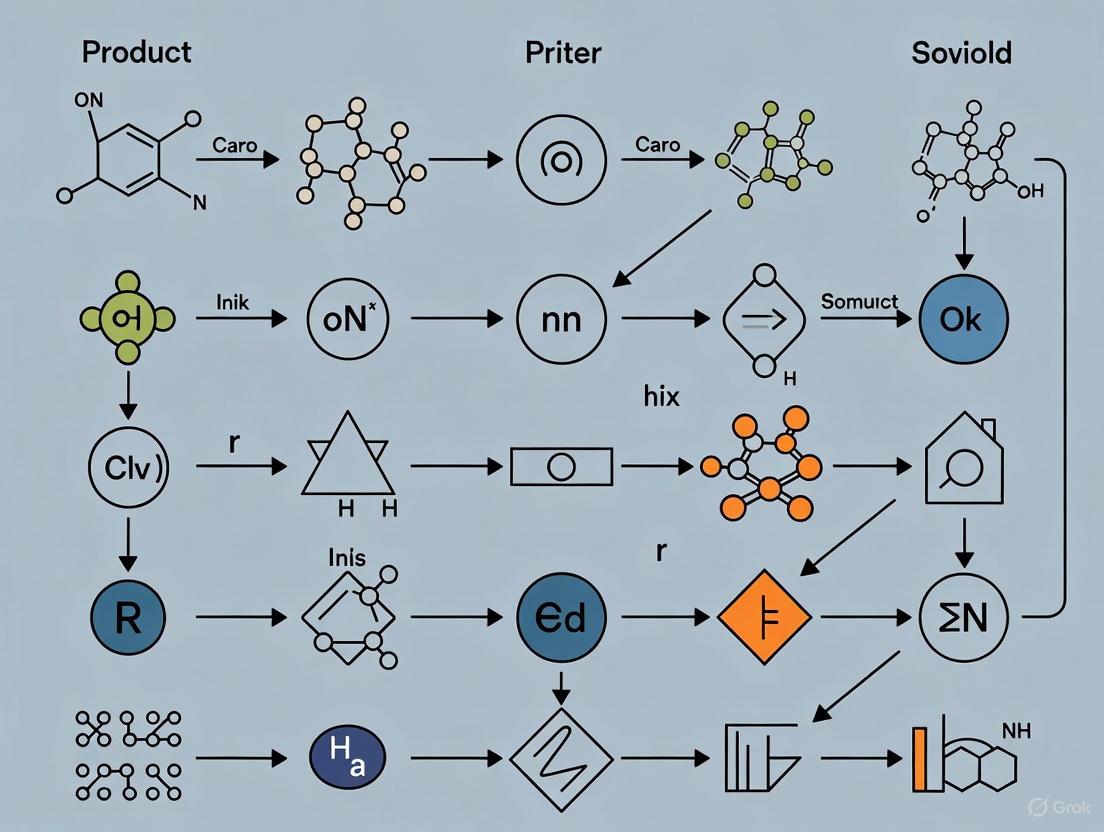

The following diagram illustrates the complete metabolic network reconstruction workflow:

Metabolic Network Modeling Approaches

Constraint-Based Modeling and Flux Balance Analysis

Flux Balance Analysis is a cornerstone constraint-based method for analyzing genome-scale metabolic models. FBA predicts metabolic fluxes by leveraging mass balance constraints and optimization principles without requiring detailed kinetic parameters [4]. The mathematical formulation of FBA is:

Objective: Maximize Z = cáµ€v Subject to: Sv = 0 and vₘᵢₙ ≤ v ≤ vₘâ‚â‚“

Where S is the stoichiometric matrix, v is the flux vector, and c is the objective function coefficient vector [4]. The cellular objective is typically biomass production, representing the balanced synthesis of all cellular components needed for growth.

FBA relies on two key assumptions: the quasi-steady-state approximation, which assumes metabolite concentrations remain constant over time, and cellular optimization, which posits that metabolism is regulated to maximize fitness [4]. These assumptions enable the prediction of metabolic behavior using linear programming, with typical genome-scale optimizations completing in milliseconds on standard computers [5].

Dynamic and Spatially-Explicit Modeling

Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis extends FBA to simulate temporal changes in microbial communities and their environments. dFBA iteratively applies FBA while updating extracellular metabolite concentrations and biomass based on predicted fluxes, creating piecewise-linear approximations of growth curves and metabolite changes over time [5].

The COMETS platform implements advanced dynamic modeling that incorporates spatial structure, evolutionary dynamics, and extracellular enzyme activity. COMETS simulates microbial ecosystems in structured environments using a 2D grid where each compartment has defined dimensions and volume. This approach predicts emergent ecological interactions from individual species metabolism [5].

Dynamic Flux Activity is a specialized approach for analyzing time-course metabolomics data. DFA identifies metabolic flux rewiring by interpreting metabolite accumulation or depletion as evidence for changed flux activity through associated reactions [4].

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between different modeling approaches:

Integration with Omics Data

Metabolic models gain predictive power when constrained with experimental data. Transcriptomics and proteomics data can be integrated to identify active reactions in specific conditions.

The constrainfluxregulation algorithm incorporates omics data by maximizing both biomass production and consistency with expression data. The formulation maximizes Σ(tᵢ + rᵢ) where tᵢ and rᵢ indicate whether reaction i is active in positive or negative directions based on expression evidence [4].

Multi-omics Integration Strategies:

- Transcriptomics: Constrain reaction fluxes based on gene expression levels

- Proteomics: Identify active enzymes and constrain their catalytic capacity

- Metabolomics: Set internal metabolite accumulation or depletion rates

- Fluxomics: Directly incorporate measured metabolic fluxes as constraints

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Protocol for Steady-State Modeling with Transcriptomics Data

This protocol details the integration of transcriptomics data with genome-scale metabolic models to predict cell-type specific metabolic behavior [4].

Materials:

- Genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., RECON1 for human cells)

- Transcriptomics data (e.g., from GEO database)

- COBRA Toolbox for MATLAB or Python

- Linear programming solver (e.g., Gurobi)

Method:

- Model Preparation: Load the metabolic model and define the objective function (typically biomass production). Set nutrient uptake constraints to reflect culture conditions.

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize transcriptomics data and map genes to model reactions. Define upregulated and downregulated reactions based on expression thresholds.

- Flace Calculation: Implement the constrainfluxregulation algorithm to find a flux distribution that maximizes both the biological objective and consistency with expression data.

- Validation: Compare predicted growth rates or metabolic capabilities with experimental measurements. Perform sensitivity analysis on expression thresholds.

- Interpretation: Identify key metabolic differences between conditions by analyzing flux differences through specific pathways.

Protocol for Dynamic Modeling with COMETS

COMETS simulates microbial community dynamics in spatially structured environments, predicting emergent interactions from individual species metabolism [5].

Materials:

- COMETS software platform with Python or MATLAB interface

- Genome-scale metabolic models for community members

- Environmental parameters (metabolite diffusion rates, spatial dimensions)

Method:

- Model Configuration: Load metabolic models for all species. Define initial biomass distributions and environmental metabolite concentrations.

- Spatial Setup: Configure 2D simulation grid with appropriate dimensions and barrier placements if needed. Set metabolite diffusion coefficients.

- Dynamic Parameters: Define time step duration and total simulation time. Set biomass spreading parameters to simulate colony expansion.

- Simulation Execution: Run COMETS simulation, monitoring metabolite consumption/production and population dynamics.

- Analysis: Visualize spatial metabolite gradients and population distributions. Identify cross-feeding interactions and ecological relationships.

Applications in Biomedical Research

Metabolic network modeling has diverse applications in biomedical research and drug development:

Drug Target Identification: Essential genes predicted by metabolic models represent potential drug targets, particularly for pathogens and cancer cells. Double gene knockout simulations can identify synthetic lethal pairs for targeted therapies.

Toxicology and Safety Assessment: Models can predict metabolic consequences of compound exposure, identifying potential toxicity mechanisms through altered flux distributions.

Personalized Medicine: Patient-specific models built from genomic and transcriptomic data can predict individual metabolic variations and treatment responses.

Example Application: A 2025 study used metabolomic and gene network approaches to understand how terahertz radiation affects human melanoma cells, identifying significant alterations in purine, pyrimidine, and lipid metabolism, with mitochondrial membrane components playing a key role in the cellular response [6].

Research Tools and Databases

Successful metabolic reconstruction and modeling requires leveraging specialized databases, software tools, and computational resources.

Table 1: Essential Databases for Metabolic Reconstruction

| Database | Scope | Primary Use | URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG | Genes, enzymes, reactions, pathways | Draft reconstruction and pathway analysis | https://www.genome.jp/kegg/ |

| BioCyc/MetaCyc | Enzymes, reactions, pathways | Curated metabolic pathway information | https://metacyc.org/ |

| BRENDA | Enzyme functional data | Kinetic parameters and organism-specific enzyme data | https://www.brenda-enzymes.org/ |

| BiGG Models | Genome-scale metabolic models | Curated metabolic reconstructions | http://bigg.ucsd.edu/ |

| ENZYME | Enzyme nomenclature | Reaction and EC number information | https://enzyme.expasy.org/ |

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Metabolic Modeling

| Tool | Function | Inputs | Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | Flux balance analysis | Metabolic model, constraints | Flux distributions, predictions |

| Pathway Tools | Pathway visualization and analysis | Annotated genome | Metabolic reconstruction, pathway maps |

| ModelSEED | Automated model reconstruction | Genome annotation | Draft metabolic model |

| COMETS | Dynamic spatial modeling | Multiple metabolic models | Population dynamics, metabolite gradients |

| FluxVisualizer | Flux visualization | SVG network, flux data | Customized pathway diagrams |

Visualization Tools: FluxVisualizer is a specialized Python tool for visualizing flux distributions on custom metabolic network maps. It automatically adjusts reaction arrow widths and colors based on flux values, supporting outputs from FBA, elementary flux mode analysis, and other flux calculations [7].

Computational Requirements:

- Standard FBA: Standard desktop computer

- Genome-scale dynamic simulations: High-performance computing cluster

- Community modeling with spatial dimensions: Workstation with substantial RAM (32+ GB)

The field of metabolic network modeling continues to evolve with several emerging trends. Single-cell analysis techniques are enabling the resolution of metabolic heterogeneity within cell populations, while machine learning approaches are being integrated to analyze and interpret complex multi-omics datasets [1]. The development of multiscale models that integrate metabolism with signaling and regulatory networks represents another frontier, providing more comprehensive representations of cellular physiology.

Challenges and Opportunities: Despite advances, several challenges remain in metabolic network reconstruction and modeling. Incomplete genomic annotations and limited organism-specific biochemical data continue to constrain model accuracy and coverage [1]. The development of more sophisticated methods for integrating multi-omics data and addressing metabolic regulation beyond the stoichiometric constraints represents an active area of research.

For drug development professionals, metabolic network modeling offers a powerful framework for understanding disease mechanisms and identifying therapeutic targets. As these models become more sophisticated and better integrated with experimental data, they will play an increasingly important role in personalized medicine and drug discovery pipelines.

Table 3: Historical Development of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

| Organism | Genes in Model | Reactions | Metabolites | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemophilus influenzae | 296 | 488 | 343 | 1999 |

| Escherichia coli | 660 | 627 | 438 | 2000 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 708 | 1,175 | 584 | 2003 |

| Homo sapiens | 3,623 | 3,673 | - | 2007 |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 1,419 | 1,567 | 1,748 | 2010 |

The continued refinement of protocols for metabolic network reconstruction and modeling, along with the development of more user-friendly tools, will make these approaches more accessible to researchers across biological and biomedical disciplines. By providing a quantitative framework for understanding metabolic function, these methods will play an increasingly important role in bridging the gap between genomic information and physiological outcomes.

Constraint-based metabolic models, particularly those utilizing Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), have become indispensable tools for systems biology, enabling the prediction of cellular physiology and growth from annotated genomic information [5] [8]. These methods rely on the quasi-steady-state assumption (QSSA), which posits that metabolic reactions are fast and reach a steady state relative to slower cellular processes like gene regulation [8]. This assumption simplifies metabolism into a linear, parameter-free problem that can be simulated efficiently even for genome-scale networks [8]. The most common application is FBA, a mathematical approach that predicts flux distributions by optimizing a cellular objective, such as the maximization of biomass production [9] [5].

However, the very strength of this approach—its simplification of metabolism to a steady state—is also its fundamental limitation. By assuming invariant metabolite concentrations over time, traditional FBA cannot capture the dynamic behavior of cells in changing environments [8]. It provides a single, static snapshot of metabolic potential under specified conditions, failing to model the temporal transitions, metabolic oscillations, and shifting interactions that characterize real biological systems, from microbial communities to human tissues [10] [5] [8]. This article details why dynamic extensions are critically needed and provides protocols for their implementation.

Key Limitations of Steady-State Metabolic Models

Inability to Model Temporal Dynamics and Changing Environments

Steady-state models like FBA are inherently unsuited for simulating processes where time is a critical factor.

- Dynamic Metabolic Transitions: Processes such as metabolic shifts between different nutrient sources, diurnal cycles in plants, or the metabolic rewiring during stem cell differentiation [10] involve continuous changes in intracellular metabolite levels and reaction fluxes that cannot be captured in a single steady-state solution.

- Batch Culture & Bioprocess Optimization: In industrial bioreactors, microorganisms experience constantly changing nutrient concentrations and waste product accumulation. Steady-state models cannot predict the dynamic trajectory of cell growth and product formation in these systems, which is essential for optimizing yield and productivity [11].

Failure to Capture Critical Spatial and Multi-Scale Interactions

The steady-state assumption severely limits the modeling of systems where spatial structure and exchange are key.

- Microbial Communities: Natural and synthetic microbial communities thrive on metabolic interactions where species exchange metabolites [5] [8]. In these systems, the extracellular concentration of a metabolite, which is the uptake substrate for one species and the secretion product of another, couples their physiologies. As stated in the research, "For unbiased methods such as pathway analysis and random sampling, the size of multiple interacting metabolic networks exacerbates the computational challenges and makes flux prediction for multicellular systems practically infeasible" [8].

- Spatially Structured Environments: The function of biofilms, soil microbiomes, and colonies on agar surfaces is dictated by nutrient diffusion and physical barriers [5]. Standard FBA models, which assume a well-mixed environment, cannot predict the emergent spatial organization and metabolic specializations that arise in these contexts.

Lack of Integration with Concentration and Kinetic Data

Steady-state models operate purely on stoichiometry and constraints on reaction fluxes, creating a disconnect with measurable physiological data.

- Bridging Fluxes and Concentrations: A fundamental challenge is "bridging this gap between fluxes and concentrations... of particular importance for multicellular systems" [8]. While FBA can predict metabolic fluxes, it cannot simulate the dynamic changes in metabolite concentrations that result from these fluxes and that, in turn, regulate enzyme activity through feedback inhibition.

- Incorporating Kinetic Regulations: Many metabolic pathways are controlled by allosteric regulation, where a metabolite inhibits an enzyme upstream in its own biosynthesis. Such regulatory loops are dynamic and concentration-dependent, falling outside the scope of classic FBA [9].

Table 1: Core Limitations of Steady-State Models and Dynamic Consequences.

| Limitation | Steady-State (FBA) Consequence | Dynamic Manifestation |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Change | Provides a single, optimal flux state for a fixed environment. | Cannot predict lag phases, metabolic oscillations, or response to perturbations over time. |

| Spatial Structure | Assumes a well-mixed, homogeneous environment. | Cannot simulate gradient-driven phenomena like biofilm formation or colony zonation. |

| Extracellular Coupling | Models organisms in isolation with fixed uptake/secretion rates. | Fails to predict emergent interactions in microbial ecosystems (e.g., syntrophy, competition). |

| Kinetic Regulation | Ignores metabolite concentrations and enzyme kinetics. | Cannot model feedback inhibition or substrate-level regulation of pathway fluxes. |

Foundational Dynamic Methodologies

To overcome these limitations, several computational frameworks have been developed that extend the constraint-based paradigm to incorporate dynamics.

Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis (dFBA)

Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis (dFBA) is the most direct extension of FBA for simulating time-course phenomena [5]. It iteratively solves a series of FBA problems, updating the extracellular environment between each step.

- Mathematical Principle: At each time point, FBA is performed using the current extracellular metabolite concentrations to calculate the intracellular fluxes and growth rate. These fluxes are then used to update the metabolite concentrations and biomass in the environment over a discrete time step, using a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs). This process is repeated to simulate the system's trajectory over time [5].

- Key Application: dFBA is particularly powerful for modeling batch and fed-batch fermentation processes, where it can predict the dynamics of substrate consumption, biomass growth, and product formation [11].

Computation of Microbial Ecosystems in Time and Space (COMETS)

The COMETS platform extends dFBA by incorporating spatial structure and evolutionary dynamics, making it a comprehensive tool for simulating complex microbial communities [5].

- Core Components: COMETS simulates microbial ecosystems on a 2D grid, where each grid cell can contain different metabolites and biomass concentrations. It calculates not only metabolic reactions but also the diffusion of metabolites between cells and the physical expansion of biomass upon growth [5].

- Key Workflow: The platform uses the COBRA (Constraint-Based Reconstruction and Analysis) toolbox, allowing for a seamless workflow from building metabolic models to running spatiotemporal simulations [5]. Its Python and MATLAB interfaces enhance accessibility.

The Dynamic Flux Activity (DFA) Approach

For analyzing time-course metabolomic data, the Dynamic Flux Activity (DFA) approach provides a genome-scale method to predict metabolic flux rewiring [10].

- Purpose: DFA is designed to study dynamic stem cell state transitions and other processes where steady-state assumptions are invalid. It uses time-course metabolic data to infer changes in flux distributions over time [10].

- Advantage: This method allows researchers to move beyond static snapshots and characterize the metabolic progression between different cellular states, such as naive and primed pluripotency in stem cells [10].

The following diagram illustrates the core logical workflow shared by these dynamic methodologies, particularly dFBA and COMETS.

Application Note: A Protocol for Dynamic Modeling with COMETS

This protocol provides a guide for simulating microbial community dynamics using the COMETS platform, based on the detailed methods in Nature Protocols [5].

Experimental Workflow

The overall process, from model preparation to simulation and analysis, is summarized below.

Step-by-Step Computational Protocol

Objective: To simulate the growth and metabolic interaction of two microbial species in a spatially structured environment.

Materials and Reagents: Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for COMETS Modeling.

| Item | Function/Description | Example Sources/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models | Stoichiometric representations of organism metabolism. Form the core of the simulation. | BiGG Models [2], ModelSEED [2] [11] |

| COMETS Software Platform | The simulation engine that performs the dynamic, spatial calculations. | http://runcomets.org [5] |

| COBRA Toolbox | A software suite used for constraint-based modeling. Integrates with COMETS. | COBRApy (Python) [5] |

| Python or MATLAB | Programming environments used to set up, run, and analyze COMETS simulations. | - |

| Simulation Parameter File | A text file defining the physical and biological parameters of the virtual environment. | Created by the user [5] |

Procedure:

Model Acquisition and Curation:

- Obtain genome-scale metabolic models in SBML format for your organisms of interest from public databases such as BiGG or ModelSEED [2] [5] [11].

- Validate that the models can simulate growth on the intended basal medium using FBA within the COBRA toolbox. Ensure exchange reactions for key metabolites are correctly defined.

Simulation Parameterization:

- Define the World: Create a 2D grid (e.g., 50x50 cells) with a specified physical dimension (e.g., 0.1 cm width/height per cell).

- Set Initial Conditions: Specify the initial biomass location for each species (e.g., as a single colony in the center or multiple colonies) and the initial concentration of metabolites in the medium across the grid.

- Configure Dynamics: Set the total simulation time (e.g., 200 hours) and the time step for dynamic updates (e.g., 0.01 hours). Define diffusion constants for key metabolites to allow for spatial gradient formation [5].

Script Configuration and Execution:

- Using the COMETS Python or MATLAB interface, write a script that loads the metabolic models, applies the simulation parameters, and defines the biomass and media initial conditions.

- Execute the COMETS simulation. The computation time can range from minutes to days depending on the model complexity, grid size, and simulation duration [5].

Output Analysis:

- COMETS generates output files tracking biomass of each species and metabolite concentrations for every location on the grid over time.

- Analyze these outputs to visualize:

- The spatial expansion and morphology of colonies.

- The consumption and secretion profiles of metabolites.

- The emergence of metabolic interactions, such as cross-feeding, where one species consumes a metabolite produced by another [5].

Application Note: A Protocol for Visualizing Dynamic Metabolomic Data

This protocol utilizes the GEM-Vis method to create animated visualizations of time-series metabolomic data within the context of a metabolic network [12].

Experimental Workflow

The process transforms raw time-course data into an intuitive, dynamic representation of metabolic activity.

Step-by-Step Visualization Protocol

Objective: To create an animated video that displays changes in metabolite concentrations over time on a metabolic network map.

Materials and Reagents: Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Dynamic Visualization.

| Item | Function/Description | Example Sources/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal Metabolomic Data | Quantitative measurements of metabolite concentrations at multiple time points. | MS/NMR data from experimental studies [12] |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Model | A structured model containing all known metabolites and reactions for the organism. | SBML file from BioModels, BiGG [12] |

| SBMLsimulator Software | The application used to simulate the model and generate the animation. | Freely available software [12] |

| Manually Curated Network Layout | (Optional) A visually informative map of the metabolic network. | Drawn with tools like Escher [12] |

Procedure:

Data and Model Preparation:

- Compile a dataset of metabolite concentrations at multiple time points. Ensure the data is normalized and mapped to the correct metabolite identifiers in your metabolic model.

- Acquire a metabolic model for your target cell type or organism in SBML format. If a visually pleasing layout for this model does not exist, one can be created using tools like Escher [12].

Software Configuration:

- Load the SBML model and the time-series data into SBMLsimulator.

- Choose a visual representation for metabolite levels. The GEM-Vis method suggests using the fill level of a circle representing each metabolite node, as this allows for the most intuitive human estimation of quantity [12]. Alternative methods include mapping concentration to node size or color.

Animation Generation:

- SBMLsimulator will interpolate between the provided time points to create a smooth animation.

- Configure the animation settings, such as frame rate and video length, and generate the movie file.

Interpretation and Analysis:

- Observe the animation to identify patterns and generate hypotheses. For example, in a case study of human platelets, this technique elucidated a coordinated accumulation of nicotinamide and hypoxanthine, suggesting related pathway usage during storage that was not apparent from static data analysis [12].

The limitations of steady-state metabolic models are profound and multifaceted, restricting their utility in modeling the dynamic, interactive, and spatially structured nature of real biological systems. Methodologies like dFBA, COMETS, and DFA, along with visualization tools like GEM-Vis, represent a critical evolution in computational systems biology. They provide the frameworks and protocols necessary to move from static snapshots to dynamic movies of cellular metabolism. As these tools become more accessible and integrated with multi-omics data, they will dramatically enhance our ability to engineer microbes for bioproduction, understand complex diseases, and predict the behavior of entire microbial ecosystems.

This application note provides a detailed methodology for integrating genomic annotation data with metabolic pathway analysis through G-protein coupled receptor (GPR) associations. We present standardized protocols for researchers investigating metabolic networks, with specific applications for drug development targeting metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes and obesity. The protocols leverage current bioinformatics tools and computational approaches to establish functional links between genetic variants and metabolic phenotypes via GPR-mediated signaling pathways.

G-protein coupled receptors (GPRs) represent a critical interface between genomic information and metabolic function. These receptors regulate virtually all metabolic processes, including glucose and energy homeostasis, and have emerged as promising therapeutic targets for metabolic disorders [13]. The systematic association of genomic annotations with metabolic pathways through GPRs enables researchers to prioritize functional genetic variants and elucidate their mechanistic roles in metabolic diseases. This framework is particularly valuable for identifying candidate causal mutations in quantitative genetics and improving genomic prediction models for complex traits.

Background Concepts

GPR Signaling in Metabolic Regulation

GPRs typically activate heterotrimeric G proteins, which can be subgrouped into four major functional classes: Gαs, Gαi, Gαq/11, and G12/13 [13]. Upon ligand binding, GPCRs undergo conformational changes that trigger intracellular signaling cascades affecting metabolic processes. Additionally, many GPCRs initiate β-arrestin-dependent, G-protein-independent signaling pathways that modulate metabolic outcomes [13]. The table below summarizes key GPRs involved in metabolic regulation:

Table 1: Metabolic Functions of Selected GPRs

| GPR | Endogenous Ligands | Metabolic Functions | Therapeutic Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPR40 (FFAR1) | Long-chain fatty acids | Enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, mediates antifibrotic activity [14] [13] | Type 2 diabetes treatment |

| GPR84 | Medium-chain fatty acids | Promotes inflammatory responses, contributes to fibrosis pathways [14] | Anti-fibrotic therapies |

| GPR35 | Kynurenic acid, Lysophosphatidic acid | Regulates energy balance via gut-brain axis, modulates peptide hormone secretion [13] | Metabolic syndrome |

| GPER | Estrogen | Modulates glucose, protein, and lipid metabolism; regulates insulin sensitivity [15] | Metabolic disorders |

Genomic Annotation Fundamentals

Genomic annotations provide critical information about the functional potential of genetic variants. Key annotation types include:

- Evolutionary constraint metrics: Phylogenetic nucleotide conservation (PNC) detects candidate causal mutations by conservation of DNA bases across species, serving as an indirect indicator of fitness effect [16].

- Functional impact scores: SIFT scores quantify the impact of nonsynonymous mutations by calculating the probability of their codon change (lower scores indicate more damaging mutations) [16].

- Protein structure annotations: UniRep variables characterize protein ontology and structure through quantitative representations of protein sequences [16].

Protocol 1: Genomic Variant Prioritization for Metabolic Traits

Materials and Reagents

- High-performance computing infrastructure

- Whole-genome or exome sequencing data (VCF format)

- Reference genomes (GRCh37/GRCh38 for human studies)

- Genomic annotation databases (dbSNP, ClinVar, GNOMAD)

- Functional prediction tools (SIFT, PolyPhen-2, CADD)

- FUMA GWAS platform access [17]

Procedure

Step 1: Data Preparation and Quality Control

- Format GWAS summary statistics to include mandatory columns: SNP ID, chromosome, position, P-value, and effect alleles [17].

- Ensure build compatibility (GRCh37 or GRCh38) using liftOver tools if necessary.

- Perform quality control: remove SNPs with low call rate (<95%), Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium violations (P<1×10â»â¶), and imputation quality score (INFO<0.8).

Step 2: Functional Annotation with FUMA SNP2GENE

- Upload GWAS summary statistics to the FUMA web platform [17].

- Set parameters for lead SNP identification (default: r² 0.6 for genome-wide significant SNPs, r² 0.1 for lead SNPs).

- Configure gene mapping parameters (default: window size of 10kb around genes).

- Enable functional annotation filters including CADD scores, RegulomeDB scores, and chromatin interaction data.

- Submit job and monitor processing status via the "My Jobs" queue [17].

Step 3: Evolutionary Constraint Analysis

- Apply the PICNC (Prediction of mutation Impact by Calibrated Nucleotide Conservation) framework to predict evolutionary constraint [16].

- Integrate multiple annotation types:

- Genomic structure features (transposon insertion, GC content, k-mer frequency)

- Protein impact scores (SIFT, mutation type)

- Protein structure features (UniRep variables, in silico mutagenesis scores)

- Use leave-one-chromosome-out cross-validation to prevent overfitting.

- Prioritize variants with high predicted evolutionary constraint for further analysis.

Step 3.3: Expected Results and Interpretation

- The output will include prioritized genes and variants with functional annotations.

- High-priority candidates typically exhibit low SIFT scores (<0.05), high CADD scores (>20), and high predicted evolutionary constraint.

- Evolutionary constrained variants are enriched in central carbon metabolism pathways in metabolic traits [16].

Protocol 2: GPR Contextualization and Pathway Mapping

Materials and Reagents

- GPR annotation databases (GPCRdb, IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology)

- Pathway analysis tools (KEGG, Reactome, MetaCyc)

- Gene expression datasets (GTEx, Human Protein Atlas)

- Cell-specific marker databases

Procedure

Step 1: GPR Expression Profiling

- Query expression databases for tissue-specific GPR expression patterns.

- Prioritize GPRs expressed in metabolic tissues: white and brown adipose tissue, liver, pancreatic β-cells, and gastrointestinal tract [13].

- Identify co-expression patterns with metabolic pathway genes.

Step 2: Signaling Pathway Mapping

- Annotate G-protein coupling specificity (Gαs, Gαi, Gαq/11, G12/13) for identified GPRs.

- Map downstream signaling effectors:

- cAMP/PKA pathway for Gαs-coupled receptors

- PLC-IP3/DAG pathway for Gαq/11-coupled receptors

- MAPK/ERK pathway for multiple GPR classes

- Identify β-arrestin-dependent signaling components for relevant GPRs.

Step 3: Metabolic Pathway Integration

- Link GPR signaling to metabolic pathways using KEGG and Reactome databases.

- Focus on pathways regulating insulin secretion, glucose homeostasis, lipid metabolism, and energy expenditure.

- Construct integrated network models connecting GPR activation to metabolic outputs.

Diagram 1: GPR Signaling to Metabolic Output

Protocol 3: Dynamic Modeling of GPR-Metabolic Networks

Materials and Reagents

- Constraint-based modeling software (CobraPy, MetToolnik)

- Time-course metabolomics data

- Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs)

- Flux balance analysis tools

Procedure

Step 1: Network Construction

- Import genome-scale metabolic network model appropriate for your system.

- Integrate GPR associations using Boolean logic rules that link genes to reactions.

- Incorporate regulatory constraints based on GPR signaling states.

Step 2: Dynamic Flux Modeling

- Apply the Dynamic Flux Activity (DFA) approach for time-course metabolic data [10].

- Parameterize reaction bounds based on GPR expression and activation states.

- Simulate metabolic flux rewiring in response to GPR modulation.

Step 3: Integration with Experimental Data

- Incorporate transcriptomics data to constrain gene expression in the model.

- Integrate metabolomics measurements to validate flux predictions.

- Compare in silico simulations with experimental metabolic phenotypes.

Diagram 2: Dynamic Modeling Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| FUMA GWAS Platform | Functional mapping and annotation of GWAS results | Provides SNP2GENE and GENE2FUNC modules for functional prioritization [17] |

| PICNC Framework | Predicts evolutionary constraint from genomic annotations | Uses random forest with genomic and protein structure features [16] |

| GPR40/GPR84 Modulators | Probe GPR function in metabolic pathways | PBI-4050 acts as GPR40 agonist/GPR84 antagonist with antifibrotic effects [14] |

| Chroma.js | Color manipulation for data visualization | Enables accessible color schemes for metabolic pathway diagrams [18] |

| Dynamic Flux Activity (DFA) | Models metabolic rewiring from time-course data | Approaches steady-state limitations of traditional FBA [10] |

| UniRep | Protein sequence representation learning | Generates latent representations for in silico mutagenesis [16] |

| Jatrophane 5 | Jatrophane 5, CAS:210108-89-7, MF:C41H49NO14, MW:779.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pepluanin A | Pepluanin A, MF:C43H51NO15, MW:821.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Data Presentation Standards

Quantitative Data Tabulation

Effective presentation of quantitative data requires structured tabulation with the following principles [19] [20]:

- Tables should be numbered sequentially and have clear, concise titles

- Headings for columns and rows should be self-explanatory

- Data should be presented in logical order (size, importance, chronological, or geographical)

- Percentage or averages for comparison should be placed close together

- Footnotes should provide explanatory notes where necessary

Table 3: Example Frequency Distribution for Metabolic Parameter

| Class Interval | Frequency | Cumulative Frequency | Relative Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 120-134 | 4 | 4 | 4.0 |

| 135-149 | 14 | 18 | 14.0 |

| 150-164 | 16 | 34 | 16.0 |

| 165-179 | 28 | 62 | 28.0 |

| 180-194 | 12 | 74 | 12.0 |

| 195-209 | 8 | 82 | 8.0 |

| 210-224 | 7 | 89 | 7.0 |

| 225-239 | 6 | 95 | 6.0 |

| 240-254 | 2 | 97 | 2.0 |

| 255-269 | 3 | 100 | 3.0 |

For graphical representation of quantitative data, histograms or frequency polygons are recommended for continuous metabolic variables [20]. Frequency polygons are particularly useful for comparing distributions of multiple metabolic parameters.

Applications in Drug Development

The integration of genomic annotations with GPR-metabolic pathways has significant applications in pharmaceutical development:

Target Prioritization

- Identify GPRs with genetic associations to metabolic traits

- Validate targets through evolutionary constraint metrics

- Assess potential on-target side effects using expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) data

Biased Agonism Development

The concept of "biased agonism" enables development of therapeutics that selectively activate beneficial signaling pathways while avoiding adverse effects [13]. For example:

- G protein-biased agonists may promote metabolic benefits without receptor internalization

- β-arrestin-biased agonists may achieve distinct metabolic outcomes

- Balanced agonists activate both G protein and β-arrestin pathways

Troubleshooting Guide

| Issue | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low annotation coverage in genomic regions | Build mismatch or incomplete annotation | Verify genome build consistency; use liftOver for conversion |

| Poor connection between GPR variants and metabolic pathways | Incomplete pathway annotation | Curate custom pathway databases; use multiple pathway resources |

| Inaccurate flux predictions in dynamic modeling | Incorrect GPR constraint implementation | Verify Boolean logic rules; validate with experimental data |

| Low prioritization accuracy for causal variants | Insufficient evolutionary context | Integrate cross-species conservation metrics with PICNC [16] |

The integration of genomic annotations with metabolic pathways through GPR associations provides a powerful framework for understanding metabolic regulation and identifying therapeutic targets. These protocols enable systematic prioritization of functional variants, contextualization within signaling pathways, and dynamic modeling of metabolic networks. As genomic datasets continue to expand, these approaches will become increasingly essential for drug development targeting metabolic diseases.

Metabolic network modeling represents a cornerstone of systems biology, enabling researchers to predict physiological behavior, identify drug targets, and engineer microbial factories. The accuracy and predictive power of these models fundamentally depend on the quality of the underlying biochemical knowledge bases that inform them. Among the numerous resources available, four databases have emerged as foundational pillars for metabolic research: KEGG, BioCyc, MetaCyc, and BiGG Models. These databases provide the structured, computationally accessible biochemical knowledge required for dynamic modeling of metabolic networks, each offering unique strengths, curation philosophies, and applications. This protocol outlines the strategic implementation of these resources within metabolic modeling workflows, providing researchers with a structured approach to database selection, data extraction, and model construction for drug discovery and basic research applications.

Scope and Primary Functions

The four primary databases serve complementary roles in metabolic network modeling:

KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes): Provides integrated knowledge primarily derived from genome sequencing and other high-throughput experimental technologies. KEGG PATHWAY presents manually drawn pathway maps representing molecular interaction, reaction, and relation networks [21]. A key feature is its modular organization with pathway identifiers that specify reference pathways, organism-specific pathways, and pathway maps highlighting specific elements like enzyme commission numbers or ortholog groups [21].

MetaCyc: Functions as a curated database of experimentally elucidated metabolic pathways from all domains of life, serving as an encyclopedic reference on metabolism [22] [23] [24]. Unlike organism-specific databases, MetaCyc collects experimentally determined pathways from multiple organisms, aiming to catalog the universe of metabolism by storing a representative sample of each experimentally elucidated pathway [24]. It contains exclusively experimentally validated metabolic pathways, making it particularly valuable for understanding confirmed metabolic capabilities.

BioCyc: Represents a collection of Pathway/Genome Databases (PGDBs), each describing the genome and metabolic network of a single organism [25]. BioCyc integrates genome data with comprehensive metabolic reconstructions, regulatory networks, protein features, orthologs, and gene essentiality data [25]. The databases within BioCyc are computationally derived from MetaCyc and then undergo varying degrees of manual curation [26].

BiGG Models: Serves as a knowledgebase of genome-scale metabolic network reconstructions (GEMs) that are mathematically structured and ready for computational simulation [27] [28]. BiGG Models focuses on standardizing reaction and metabolite identifiers across models, enabling consistent flux balance analysis and other constraint-based modeling approaches [27].

Quantitative Comparison of Database Content

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Database Scope and Content

| Database | Pathways | Reactions | Metabolites | Organisms | Primary Content Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG | ~179 modules, ~237 map pathways [29] | ~8,692 [29] | ~16,586 [29] | >1,000 [26] | Reference and organism-specific pathways |

| MetaCyc | ~3,128-3,153 [23] [24] | ~18,819-19,020 [23] [24] | ~11,991-19,372 [23] [29] | 2,914-3,443 different organisms [22] [24] | Experimentally elucidated pathways from multiple organisms |

| BioCyc | Varies by organism | Varies by organism | Varies by organism | >20,000 PGDBs [25] | Organism-specific Pathway/Genome Databases |

| BiGG Models | Not a primary focus | Standardized across models | Standardized across models | >75 curated models [27] | Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) |

Table 2: Database Characteristics and Applications

| Characteristic | KEGG | MetaCyc | BioCyc | BiGG Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curation Approach | Mixed manual and computational [26] | Literature-based manual curation [24] | Tiered curation (Tier 1 highly curated) [25] | Manual curation of metabolic models [26] |

| Pathway Conceptualization | Large, modular pathways combining related functions [29] [26] | Individual biological pathways from specific organisms [29] [26] | Organism-specific metabolic networks | Reaction networks for computational modeling |

| Mathematical Structure | No | No | No | Yes (stoichiometric matrices) |

| Key Applications | Genome annotation, pathway visualization | Metabolic engineering, encyclopedia reference | Organism-specific metabolic analysis, omics data visualization | Flux balance analysis, phenotypic prediction |

The databases employ fundamentally different approaches to pathway definition and organization. KEGG pathways are typically 3.3 times larger than MetaCyc pathways on average because KEGG combines related pathways and reactions from multiple species into modular maps, while MetaCyc defines pathways corresponding to single biological functions that are regulated as units and conserved through evolution [29] [26]. For example, the KEGG "methionine metabolism" pathway combines biosynthesis, tRNA charging, and conversion pathways, while MetaCyc would separate these into distinct pathway objects [26].

Database Relationships and Workflow Integration

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationships between these databases and their role in metabolic modeling workflows:

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Metabolic Pathway Prediction and Validation Using MetaCyc and KEGG

Purpose and Principle

This protocol describes the integrated use of MetaCyc and KEGG for predicting metabolic pathways from genomic data and validating their functional presence through comparative analysis. The approach leverages MetaCyc's experimentally validated pathways as a reference database with KEGG's organism-specific pathway projections to generate high-confidence metabolic reconstructions [29] [24].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Pathway Prediction

| Resource | Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|

| Pathway Tools Software | Bioinformatics package for constructing pathway/genome databases [2] | Download from biocyc.org [24] |

| KEGG API | Programmatic access to KEGG data | SOAP-based web services [29] |

| MetaCyc Flat Files | Complete dataset for local analysis | Download from MetaCyc website [24] |

| Biocyc Subscription | Access to Tier 1 and Tier 2 databases | Registration at biocyc.org [25] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Acquisition and Integration

Pathway Prediction Using PathoLogic Algorithm

- Install Pathway Tools software on local server or computational environment

- Create new organism-specific PGDB using the annotated genome

- Select MetaCyc as reference database for pathway prediction

- Execute PathoLogic module to infer metabolic pathways [2]

- Manually review predicted pathways using Cellular Overview visualization

Comparative Validation with KEGG

- Map predicted pathways to corresponding KEGG pathways using identifier cross-references

- Identify discrepancies between MetaCyc-based predictions and KEGG annotations

- Resolve conflicts through manual literature curation focusing on experimental evidence

- Annotate pathway completeness and confidence levels based on consensus

Model Refinement and Gap Analysis

The following workflow diagram illustrates the pathway prediction and validation process:

Protocol 2: Constraint-Based Modeling Using BiGG Models

Purpose and Principle

This protocol details the construction, simulation, and analysis of genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) using BiGG Models as a knowledge base. BiGG Models provides mathematically structured, biochemically accurate reconstructions with standardized identifiers that enable flux balance analysis and phenotypic prediction [27] [28].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Resources for Constraint-Based Modeling

| Resource | Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB package for constraint-based analysis | Download from opencobra.github.io |

| BiGG Models API | Programmatic access to standardized models | RESTful API at bigg.ucsd.edu [27] |

| Escher Pathway Visualization | Interactive pathway mapping | Integrated with BiGG Models [27] |

| SBML with FBC Package | Model exchange format | Export from BiGG Models [27] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Model Selection and Acquisition

- Identify appropriate reference organism in BiGG Models database

- Access model through BiGG website or programmatically via API

- Download model in SBML Level 3 with Flux Balance Constraints (FBC) format

- Verify model quality using BiGG validation tools and documentation

Model Customization and Contextualization

- Incorporate organism-specific constraints (uptake rates, growth requirements)

- Integrate omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics) using omics dashboard

- Define tissue-specific or condition-specific objective functions

- Implement thermodynamic constraints using component contribution method

Flux Balance Analysis and Phenotypic Prediction

- Set mathematical representation: S · v = 0, where S is stoichiometric matrix

- Define constraint bounds: LB ≤ v ≤ UB

- Formulate biomass objective function for growth prediction

- Perform flux variability analysis to identify alternative optimal solutions

- Conduct gene essentiality screening through in silico knockouts

Results Visualization and Interpretation

- Map flux distributions onto Escher pathway maps

- Generate multi-omics overlay using BiGG omics visualization tools

- Compare flux patterns across genetic or environmental conditions

- Identify potential drug targets through choke-point analysis [26]

Strategic Implementation Guidelines

Database Selection Framework

Researchers should select databases based on specific research objectives:

- For metabolic engineering applications: Prioritize MetaCyc for its experimentally validated enzymes and pathways from diverse organisms, enabling identification of heterologous biosynthesis routes [24].

- For organism-specific metabolic analysis: Utilize BioCyc Tier 1 databases (EcoCyc, YeastCyc) for highly curated metabolic networks with regulatory information [25].

- For cross-species comparative studies: Employ KEGG for its consistent pathway definitions across thousands of organisms, facilitating evolutionary analysis [21] [26].

- For metabolic flux modeling and phenotype prediction: Implement BiGG Models for mathematically structured, simulation-ready reconstructions with standardized biochemistry [27] [28].

Data Integration Recommendations

Effective metabolic modeling typically requires integration of multiple databases:

- Use MetaCyc as a reference for pathway existence and experimental evidence [24]

- Leverage KEGG for comprehensive metabolite coverage and organism comparisons [29]

- Employ BiGG Models as a template for stoichiometrically consistent reaction networks [27]

- Utilize BioCyc for organism-specific pathway variants and regulatory information [25]

The strategic implementation of KEGG, MetaCyc, BioCyc, and BiGG Models provides researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for dynamic modeling of metabolic networks. Each database offers unique strengths—KEGG's breadth of organism coverage, MetaCyc's experimental rigor, BioCyc's organism-specific detail, and BiGG Models' mathematical structure. By following the protocols outlined herein and selecting databases aligned with specific research objectives, scientists can construct high-quality metabolic models capable of predicting physiological behavior, identifying drug targets, and guiding metabolic engineering strategies. The continuing curation and development of these resources ensures they will remain indispensable for metabolic research in pharmaceutical development and basic science.

Reconstructing metabolic networks is a foundational step in systems biology, enabling researchers to translate genomic and biochemical data into predictive mathematical models. These reconstructions form the essential scaffold upon which dynamic models are built, allowing for the simulation of metabolic physiology under changing genetic or environmental conditions [9] [30]. The process of creating such a reconstruction can be approached through manual curation, which leverages deep expert knowledge, or through semi-automatic methods that combine computational efficiency with human oversight. The choice of methodology significantly impacts the reconstruction accuracy, scope, and ultimate utility of the resulting model for predicting metabolic fluxes and guiding metabolic engineering strategies [30] [31]. This protocol details the application of both manual and semi-automatic reconstruction frameworks within the context of dynamic modeling of metabolic networks.

Key Reconstruction Methodologies and Their Applications

The selection of a reconstruction method is dictated by the biological question, the availability of data, and the desired modeling framework. The following table summarizes the core approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Reconstruction and Modeling Methods for Metabolic Networks

| Method Name | Primary Approach | Key Applications | Core Inputs | Principal Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Modeling (FBA) [9] [30] | Constraint-based modeling assuming metabolic steady-state. | Prediction of growth rates, nutrient uptake, and gene knockout effects; analysis of genotype-phenotype relationships. | Annotated genome, stoichiometric matrix, exchange fluxes. | Steady-state flux distribution, optimal biomass yield. |

| Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) [9] | Isotopic tracer analysis to quantify in vivo metabolic flux. | Quantification of carbon flow in central metabolism; validation of model predictions. | (^{13}\text{C})-labeled substrate, measurement of isotopic labeling in metabolites. | Empirical flux map of metabolic pathways. |

| Dynamic Modeling (Kinetic Modeling) [9] [30] | Systems of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) describing reaction kinetics. | Prediction of metabolite concentration changes over time; simulation of transient metabolic responses. | Enzyme kinetic parameters (e.g., ( V{\text{max}} ), ( Km )), initial metabolite concentrations. | Time-course data for metabolite concentrations and reaction fluxes. |

| Unsteady-State FBA (uFBA) [31] | Constraint-based modeling integrated with time-course metabolomics data. | Prediction of metabolic flux states in dynamic, non-steady-state systems (e.g., cell storage, batch fermentation). | Absolute quantitative time-course metabolomics data, genome-scale model. | Dynamic flux distributions that account for intracellular metabolite pool changes. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol: Manual Reconstruction and Curation of a Genome-Scale Metabolic Network

This protocol outlines the iterative process of manually reconstructing a genome-scale metabolic model, a critical step before dynamic model development [9] [32].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Genome Annotation Data: High-quality, organism-specific genomic data (e.g., from KEGG, BioCyc).

- Biochemical Databases: BRENDA, MetaCyc, and PlantCyc for reaction stoichiometry and metabolite information.

- Computational Environment: Software for constraint-based modeling (e.g., CobraPy in Python).

II. Procedure

- Draft Reconstruction: a. Generate an initial reaction list from the annotated genome. b. Assemble the network stoichiometry, ensuring element and charge balance for each reaction. c. Define system boundaries by identifying exchange reactions for environmental metabolites.

Network Compartmentalization: a. Assign intracellular reactions to their correct subcellular compartments (e.g., cytosol, mitochondrion, chloroplast). b. Add transport reactions to account for metabolite movement between compartments.

Manual Curation and Gap-Filling: a. Identify and resolve "gaps" in the network—reactions that prevent the synthesis of known biomass components. b. Use biochemical literature and genomic context to add missing reactions and validate gene-protein-reaction (GPR) associations. c. This step requires deep biological expertise to ensure the model is both functionally complete and biologically accurate.

Model Validation: a. Test the model's ability to produce all essential biomass precursors under defined conditions. b. Compare model predictions of essential genes and nutrient requirements with experimental data from knock-out studies or cultivation experiments.

Protocol: Implementing Unsteady-State FBA (uFBA) for Dynamic Flux Prediction

This semi-automatic protocol integrates time-course data to extend constraint-based analysis to dynamic systems [31].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Absolute Quantitative Metabolomics Data: LC-MS or GC-MS data providing intracellular and extracellular metabolite concentrations over time.

- Genome-Scale Metabolic Model: A manually curated model for the target organism.

- Computational Tools: Scripting environment (e.g., MATLAB, Python) with linear programming solvers.

II. Procedure

- Data Pre-processing and State Discretization: a. Acquire absolute quantitative measurements of metabolite concentrations across multiple time points. b. Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the time-course data to identify distinct metabolic states and define the time intervals for piecewise-linear simulation.

Model Parameterization: a. For each metabolic state (time interval), calculate the rate of change ((dX/dt)) for each measured metabolite using linear regression. b. Integrate these calculated rates as constraints into the genome-scale model.

Metabolite Node Relaxation: a. Treat the model as a closed system, removing standard exchange reactions. b. Apply a relaxation algorithm to identify the minimal set of unmeasured metabolites that must deviate from steady-state (i.e., accumulate or deplete) to make the model mathematically feasible given the measured flux constraints. This step is crucial for handling data incompleteness.

Flux State Calculation: a. With the parameterized model, use sampling methods like Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) to compute the probability distribution of fluxes through every reaction in the network. b. Analyze the resulting flux distributions to identify the most likely metabolic state and significant pathway usage during each time interval.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core decision points and steps involved in the reconstruction process, from data input to model application.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful reconstruction and modeling depend on a suite of computational and experimental resources.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for Metabolic Network Reconstruction and Modeling

| Category | Item / Software | Specific Function in Reconstruction & Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Platforms | LC-MS / GC-MS Systems | Provides absolute quantitative metabolomics data for model input and validation [31] [33]. |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Used for metabolic flux analysis (MFA) via (^{13}\text{C}) isotopic labeling to determine empirical flux maps [9] [33]. | |

| Databases & Knowledgebases | KEGG, BioCyc, PlantCyc | Sources for curated metabolic pathways, reaction stoichiometries, and enzyme information for draft reconstruction [9]. |

| BRENDA | Comprehensive enzyme resource providing kinetic parameters (e.g., ( Km ), ( V{\text{max}} )) essential for kinetic model development [30]. | |

| Computational Tools | CobraPy Toolbox | Primary software environment for constraint-based modeling, including FBA and FVA [9] [30]. |

| DVID / NeuTu | Specialized software platforms for large-scale reconstruction and visualization of complex biological networks [34]. | |

| Isotopic Tracers | (^{13}\text{C})-Labeled Substrates (e.g., (^{13}\text{CO}_2), (^{13}\text{C})-Glucose) | Fed to biological systems to trace carbon flow for Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) and Inst-MFA [9] [31]. |

| Buxbodine B | Buxbodine B, CAS:390362-51-3, MF:C26H41NO2 | Chemical Reagent |

| Pyriproxyfen-d4 | Pyriproxyfen-d4 Stable Isotope | Pyriproxyfen-d4 is a deuterium-labeled juvenile hormone analog for pesticide metabolism research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Methodologies and Applications: Building and Simulating Dynamic Metabolic Models

Constraint-Based Modeling (CBM) and Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) as a Foundation

Constraint-Based Modeling (CBM) and Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) are powerful mathematical frameworks for simulating the metabolism of cells and entire organisms using genome-scale metabolic reconstructions [35]. These approaches enable researchers to predict metabolic fluxes—the rates at which metabolites are converted through biochemical reactions—without requiring detailed kinetic information, making them particularly useful for analyzing complex, large-scale systems [36]. CBM operates under physico-chemical constraints, with the steady-state assumption being paramount: the concentration of intracellular metabolites is assumed to remain constant over time, meaning the total input flux equals the total output flux for each metabolite [36] [37]. FBA is the most widely used constraint-based approach, applying linear programming to predict an optimal flux distribution through a metabolic network that maximizes or minimizes a specified biological objective, such as biomass production or ATP generation [35] [38]. These methods have become cornerstones of systems biology, providing a platform for integrating diverse omics data and generating testable hypotheses about metabolic function in health, disease, and biotechnological applications [39].

Mathematical and Computational Framework

The core of FBA is the stoichiometric matrix, S, which mathematically represents the metabolic network. This m x n matrix, where m is the number of metabolites and n is the number of reactions, contains the stoichiometric coefficients of each metabolite in every reaction [36] [35]. The steady-state assumption is formulated as S ∙ v = 0, where v is the n-dimensional vector of reaction fluxes [35]. This equation defines a solution space of all possible flux distributions that do not lead to the accumulation or depletion of any internal metabolite.

To find a particular solution within this space, FBA formulates a linear programming problem. The goal is to find the flux vector v that optimizes a cellular objective, typically expressed as Z = cᵀv, where c is a vector of weights that define the objective, such as maximizing the flux through a biomass reaction [36] [38]. This optimization is subject to the steady-state constraint and additional capacity constraints of the form αᵢ ≤ vᵢ ≤ βᵢ, which set lower and upper bounds for each reaction flux i based on physiological and thermodynamic limits [35] [38].

Table 1: Core Mathematical Components of Flux Balance Analysis

| Component | Symbol | Description | Role in FBA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stoichiometric Matrix | S | An m x n matrix; rows represent metabolites, columns represent reactions; entries are stoichiometric coefficients. | Defines the network structure and mass-balance constraints. |

| Flux Vector | v | An n-dimensional vector containing the flux (reaction rate) of each reaction. | The variable being solved for; represents the metabolic phenotype. |

| Steady-State Constraint | S∙v = 0 | A system of linear equations. | Ensures intracellular metabolite concentrations remain constant. |

| Objective Function | Z = cáµ€v | A linear combination of fluxes to be maximized or minimized (e.g., biomass growth). | Defines the biological goal used to select an optimal flux distribution. |

| Flux Constraints | αᵢ ≤ vᵢ ≤ βᵢ | Lower and upper bounds for each reaction flux. | Incorporates thermodynamic and enzyme capacity limits. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and core constraints of a standard FBA simulation.

Advanced FBA Techniques and Solution Analysis

A single FBA solution is often not unique; multiple flux distributions can achieve the same optimal objective value [38]. Several advanced techniques have been developed to analyze the solution space more thoroughly:

- Flux Variability Analysis (FVA): This method determines the minimum and maximum possible flux for each reaction while still maintaining the optimal objective function value [36] [38]. It is crucial for identifying which fluxes are tightly constrained and which have flexibility.

- Parsimonious FBA (pFBA): Among all flux distributions that achieve the optimal objective, pFBA identifies the one that minimizes the total sum of absolute flux values [36]. This is based on the principle of metabolic parsimony, which assumes that cells have evolved to achieve their goals with minimal enzyme investment [36].

- Gene and Reaction Deletion Analysis: The effect of knocking out genes or reactions is simulated by setting the corresponding flux(es) to zero and re-optimizing the objective function [35]. Reactions are classified as essential if the objective (e.g., growth) is substantially reduced upon their deletion, making them potential drug targets [35].

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Constraint-Based Analysis

| Tool Name | Language/Platform | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox [38] | MATLAB | Suite of functions for CBM. | Model reconstruction, simulation, perturbation analysis, and integration with omics data. |

| cobrapy [38] | Python | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis. | User-friendly Python interface, extensive documentation, high interoperability. |

| Escher-FBA [38] | Web Application | Interactive flux balance analysis. | Visualization of FBA results on metabolic maps. |

| glpk, GUROBI, CPLEX [38] | Various | Linear Programming Solvers. | Core optimization engines used to solve the FBA linear programming problem. |

Protocols for Key FBA Applications

Protocol 1: In Silico Gene Essentiality Analysis for Drug Target Identification

Purpose: To identify metabolic genes and reactions that are essential for the survival of a pathogen or cancer cell, thereby revealing potential drug targets [40] [35] [41].

Materials:

- Reconstructed GEM: A high-quality, context-specific genome-scale metabolic model of the target organism (e.g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis for tuberculosis) [39].

- Software: A constraint-based modeling tool such as the COBRA Toolbox or cobrapy [38].

- Computational Environment: A standard personal computer is sufficient, as FBA simulations for large models typically take only seconds [35].

Methodology:

- Model Preparation: Load the metabolic model and set the environmental conditions (e.g., carbon source, oxygen availability) by constraining the bounds of the corresponding exchange reactions [35].

- Define Objective: Set the biomass reaction as the objective function to be maximized, simulating cellular growth [35] [38].

- Wild-Type Simulation: Perform FBA on the unperturbed model to establish the baseline (wild-type) growth rate.

- Single Gene Deletion: For each gene in the model: a. Simulate a knockout by setting the flux of all reactions associated with that gene to zero, following the Boolean logic of its Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) rules [35]. For example, if a reaction is catalyzed by an enzyme complex (GPR: Gene A AND Gene B), both genes must be knocked out to remove the reaction. If isozymes exist (GPR: Gene A OR Gene B), both genes must be knocked out to remove the reaction. b. Re-run the FBA to calculate the new growth rate.

- Analysis and Target Prioritization: a. Classify a gene as essential if the predicted growth rate after deletion falls below a pre-defined threshold (e.g., <5% of wild-type growth) [35]. b. Prioritize essential genes that are non-essential in the host (e.g., human) for further validation as selective drug targets [40] [41].

Protocol 2: Metabolic Transformation Algorithm for Disease-State Reversion

Purpose: To identify drug targets that revert a disease-associated metabolic state back to a healthy state, applicable to age-related diseases and other metabolic disorders [41].

Materials:

- Paired GEMs: Genome-scale metabolic models for both the diseased state (e.g., from patient data) and the healthy reference state [41].

- Omics Data: Transcriptomic or proteomic data from diseased and healthy tissues to constrain the models.

- Algorithm: Implementation of the Metabolic Transformation Algorithm (MTA) or similar computational frameworks [41].

Methodology:

- Model Contextualization: Integrate gene expression data from diseased and healthy tissues into their respective GEMs to create condition-specific models using methods like GIMME or iMAT [39].

- Flux Simulation: Calculate the flux distributions for both the diseased (

v_disease) and healthy (v_healthy) models using FBA or related methods. - Identify Metabolic Differentials: Compare the two flux distributions to pinpoint reactions with significantly altered fluxes in the disease state.

- In Silico Intervention: Systematically inhibit reactions in the diseased model (e.g., by constraining their flux bounds) and re-compute the flux distribution.

- Target Identification: Identify the set of reactions (drug targets) whose inhibition shifts the diseased flux distribution

v_diseaseto most closely resemble the healthy flux distributionv_healthy[41]. Experimentally validated targets for ageing, such as GRE3 and ADH2 in yeast, were discovered using this approach [41].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The application of CBM and FBA in the biopharmaceutical industry spans from preclinical research to process optimization [42]. The following table summarizes key application areas.

Table 3: Applications of CBM and FBA in Pharmaceutical Research & Development

| Application Area | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic Target Discovery [40] [35] [39] | Identification of essential genes in pathogenic bacteria that are absent in humans. | In silico gene essentiality analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis GEMs to find targets for new tuberculosis drugs [39]. |

| Cancer Therapy [40] [41] | Identification of metabolic vulnerabilities in cancer cells, often by comparing GEMs of cancerous vs. normal tissues. | Using the MTA to find targets that revert cancer metabolism to a normal state [41]. |

| Understanding Drug Metabolism & Toxicity [43] | Integration of drug metabolism pathways into human GEMs to predict metabolites and potential toxicities. | Modeling the role of cytochrome P450 enzymes (e.g., CYP3A4) in phase I metabolism and detoxification [43]. |

| Host-Pathogen Interaction Modeling [35] [39] | Combining GEMs of a pathogen and its host to study metabolic interactions during infection. | Integrating a M. tuberculosis GEM with a human alveolar macrophage model to identify combinatorial targets [39]. |

| Cell Culture Process Optimization [42] | Using GEMs of production cell lines (e.g., CHO cells) to optimize culture media and feeding strategies for biopharmaceutical production. | Predicting nutrient combinations that maximize product yield while minimizing by-products like lactate [42]. |