Diseasome and Disease Networks: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Therapeutic Development

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of diseasome and disease network concepts, bridging foundational theory with cutting-edge applications in biomedical research and drug development.

Diseasome and Disease Networks: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of diseasome and disease network concepts, bridging foundational theory with cutting-edge applications in biomedical research and drug development. We examine how network medicine approaches reveal hidden connections between diseases through shared genetic, molecular, and phenotypic pathways. The content covers methodological frameworks for constructing multi-modal disease networks, addresses critical challenges in rare disease research and clinical evidence generation, and validates approaches through case studies in autoimmune disorders, Alzheimer's disease, and heart failure. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource demonstrates how network-based strategies accelerate therapeutic discovery, enhance patient stratification, and optimize clinical trial design across diverse disease areas.

Understanding the Diseasome: Foundations of Network Medicine and Disease Relationships

The diseasome is a conceptual framework within the field of network medicine that represents human diseases as an interconnected network, where nodes represent diseases and edges represent their shared biological or clinical characteristics [1] [2]. This paradigm represents a fundamental shift from traditional reductionist models toward a holistic understanding of disease pathobiology, capturing the complex molecular interrelationships that traditional methods often fail to recognize [2]. The foundational premise of the diseasome is that diseases manifesting similar phenotypic patterns or comorbidities frequently share underlying genetic architectures, molecular pathways, and environmental influences [3] [4].

The construction and analysis of disease networks have been revolutionized by the accumulation of large-scale, multi-modal biomedical data, enabling researchers to move beyond simple, knowledge-based associations to data-driven discoveries of novel disease relationships [5] [3]. By mapping these connections, the diseasome provides a powerful scaffold for uncovering common pathogenic mechanisms, predicting disease progression, optimizing therapeutic strategies, and fundamentally reclassifying human disease based on shared biology rather than symptomatic presentation alone [5] [1].

Theoretical Foundations and Network Principles

Core Architectural Components of a Diseasome Network

In a diseasome network, the basic architectural components are consistent with general network theory. Nodes represent distinct biological entities, which can span multiple scales—from molecular entities like genes, proteins, and metabolites to macroscopic entities like specific diseases or clinical phenotypes [2]. Edges, also called links, represent the functional interconnections between these nodes. The nature of these edges varies based on the network's specific focus and can represent physical protein-protein interactions, transcriptional regulation, enzymatic conversion, shared genetic variants, or phenotypic similarity [3] [2].

The complete set of relevant functional molecular interactions in human tissue is referred to as the human "interactome," which serves as the foundational layer upon which disease-specific networks are built [2]. The structure and dynamics of the interactome are crucial for understanding how localized perturbations can lead to specific disease manifestations and why certain diseases frequently co-occur.

Key Properties of Disease Networks

Disease networks exhibit several key topological properties that provide insights into disease biology. Modularity refers to the tendency of the network to form densely connected groups, or communities, of diseases. These modules often share common etiological, anatomical, or physiological underpinnings, such as immune dysfunction or metabolic disruption [5] [4]. Centrality measures, including degree (number of connections a node has), betweenness (how often a node lies on the shortest path between other nodes), and closeness (how quickly a node can reach all other nodes), help identify diseases that are major hubs within the network, potentially pointing to conditions with widespread systemic effects [5].

The degree distribution of many biological networks has been observed to follow a power-law, indicating a scale-free topology where a few nodes (hubs) have a very high number of connections while most nodes have only a few [5]. This property suggests that the failure of certain hub proteins or pathways may have disproportionately large consequences, leading to disease. Furthermore, the within-network distance (WiND), defined as the mean shortest path length among all links in the network, quantifies the overall closeness and potential functional integration of the entire disease network [5].

Methodological Framework for Diseasome Construction

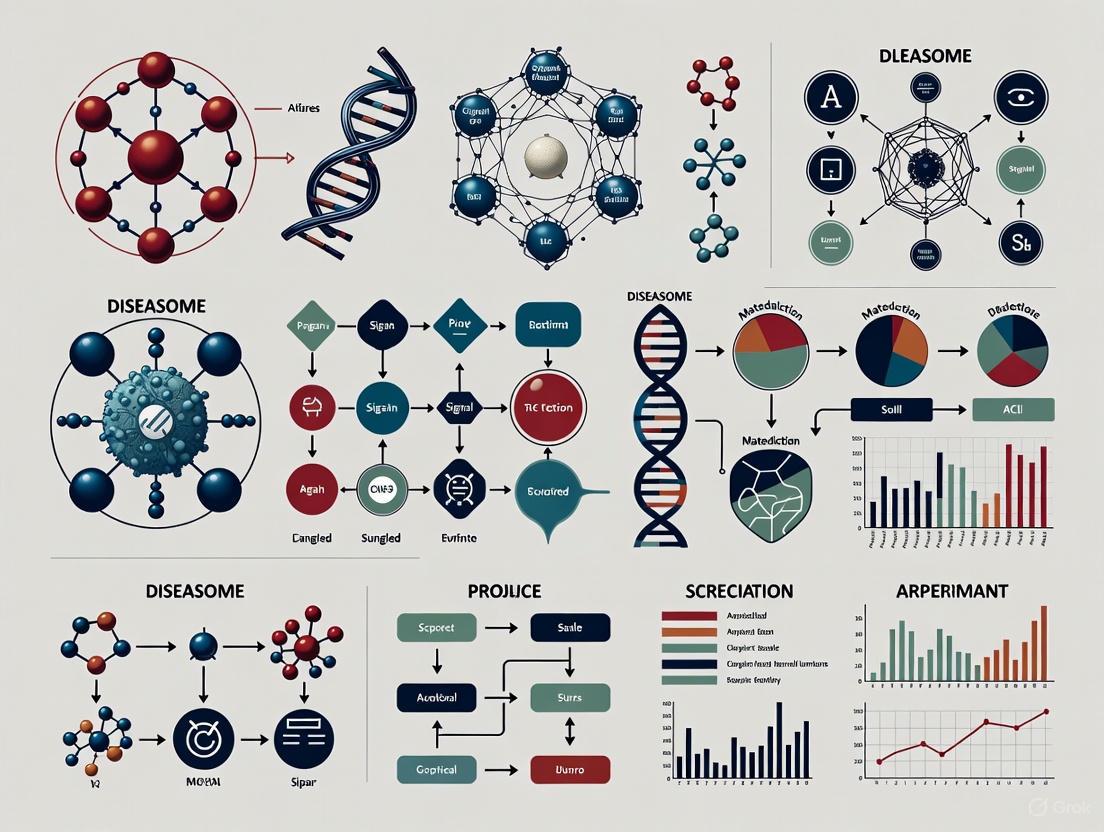

Constructing a comprehensive diseasome requires the integration of multi-scale data through a structured, hierarchical workflow. The following diagram outlines the core procedural stages.

Data Curation and Integration

The initial phase involves the systematic curation of disease terms and associated multi-modal data. A robust methodology, as demonstrated in recent autoimmune disease research, integrates disease terminologies from multiple biomedical ontologies and knowledge bases, including Mondo Disease Ontology (Mondo), Disease Ontology (DO), Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) [5]. Specialized disease databases, such as those from the Autoimmune Association (AA) and the Autoimmune Registry, Inc. (ARI), are also incorporated to ensure comprehensive coverage [5]. This process creates an integrated repository that can encompass hundreds of autoimmune diseases, autoinflammatory diseases, and associated conditions.

Table 1: Key Data Types for Multi-Modal Diseasome Construction

| Data Modality | Data Source Examples | Biological Insight Provided |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic | OMIM, GWAS, PheWAS summary statistics [3] [4] | Shared genetic susceptibility, pleiotropy, genetic correlations. |

| Transcriptomic | Bulk RNA-seq from GEO (e.g., GPL570), single-cell RNA-seq [5] | Gene expression dysregulation, cell-type specific pathways. |

| Phenotypic | Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO), Electronic Health Records (EHRs) [5] [4] | Clinical symptom and sign similarity, comorbidity patterns. |

| Proteomic & Metabolomic | PPI databases, mass spectrometry data, metabolomic profiles [6] [2] | Protein-protein interactions, metabolic pathway alterations. |

Calculation of Disease Similarity

A critical advancement in diseasome construction is the move beyond simple similarity measures to an Ontology-Aware Disease Similarity (OADS) strategy [5]. This approach leverages the hierarchical structure of biomedical ontologies to compute semantic similarity.

For genetic and transcriptomic data, disease-associated genes are mapped to Gene Ontology (GO) biological process terms. The functional similarity between diseases is then computed using methods like the Wang measure, which considers the semantic content of terms and their positions within the ontology graph [5]. For phenotypic data, terms from the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) are extracted, and similarity is again calculated using semantic measures [5] [4]. For cellular-level data from single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), cell types are annotated using Cell Ontology, and similarity can be calculated with tools like CellSim [5]. The final OADS metric aggregates these cross-ontology similarities, providing a unified, multi-scale measure of disease relatedness.

Network Construction and Analysis

With pairwise disease similarity matrices calculated, disease-disease networks (DDNs) are constructed. A common method involves setting a similarity threshold, such as retaining edges where the similarity score exceeds the 90th percentile and is statistically significant (e.g., p < 0.05, validated through permutation testing) [5]. Networks are typically built and analyzed using Python libraries like NetworkX.

Community detection algorithms, such as the Leiden algorithm, are then applied to partition the network into robust disease modules or communities [5]. The biological significance of these communities is assessed by identifying over-represented phenotypic terms, dysfunctional pathways, and cell types within each cluster, often using Fisher's exact test [5]. Topological analysis further reveals hub diseases and the overall connectivity landscape of the diseasome.

Experimental Protocols for Diseasome Analysis

Protocol 1: Constructing a Shared-SNP Disease-Disease Network (ssDDN)

This protocol details the creation of a genetically-informed diseasome using summary statistics from phenome-wide association studies (PheWAS) [3].

- Data Preparation: Obtain PheWAS summary statistics from a large biobank (e.g., UK Biobank). For binary diseases, ensure a sufficient case count (e.g., >1000 cases) to ensure statistical power. Filter out hyper-specific disease codes and hierarchically related diseases with highly correlated case counts to avoid redundant signals [3].

- Variant Filtering: Restrict the analysis to a unified set of high-quality SNPs, such as HapMap3 SNPs, to ensure consistency. Remove SNPs in regions with complex linkage disequilibrium (LD), like the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) [3].

- Edge Definition: For each pair of diseases, identify the set of shared SNPs that pass a pre-defined genome-wide significance threshold (e.g., p < 5 × 10⁻⁸) in both PheWAS. An edge is established between two diseases if the number or significance of shared SNPs suggests a genetic correlation beyond what is expected by chance [3].

- Network Augmentation (ssDDN+): To enhance interpretability, incorporate quantitative endophenotypes. Calculate genetic correlations between diseases and clinical laboratory measurements (e.g., HDL cholesterol, triglycerides) using methods like Linkage Disequilibrium Score Regression (LDSC). Introduce new edges between diseases that share significant genetic correlations with the same intermediate biomarker [3].

Protocol 2: Building a Phenotype-Based Diseasome via Text Mining

This protocol outlines the generation of a diseasome based on phenotypic similarities derived from the biomedical literature [4].

- Corpus Creation: Build a text corpus from millions of Medline article titles and abstracts.

- Entity Co-occurrence Identification: Use semantic text-mining to identify co-occurrences between disease names (from ontologies like DO) and phenotype names (from HPO and the Mammalian Phenotype Ontology, MP) within the corpus [4].

- Significance Scoring: Score each disease-phenotype co-occurrence using multiple statistical measures, such as Normalized Pointwise Mutual Information (NPMI), T-Score, and Z-Score. Rank the phenotypes associated with each disease by their NPMI score [4].

- Phenotype Set Optimization: Determine the optimal number of top-ranked phenotypes to associate with each disease by evaluating the set's power to identify known disease-associated genes in model organisms or humans. This is typically done by computing the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROCAUC) [4].

- Similarity Calculation and Network Generation: Compute pairwise phenotypic similarity between all diseases using a semantic similarity measure. Construct the network by connecting diseases with a similarity score above a chosen threshold.

Key Analytical Tools and Visualization Platforms

The analysis and visualization of diseasome networks require specialized software tools. The table below summarizes essential platforms for researchers.

Table 2: Essential Software Tools for Diseasome Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Diseasome Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cytoscape [7] | Desktop Software | Primary Function: Open-source platform for visualizing complex networks and integrating them with attribute data. Use Case: Visual exploration, custom styling, and plugin-based analysis (e.g., network centrality, clustering) of disease networks. |

| Gephi [8] | Desktop Software | Primary Function: Open-source software for network visualization and manipulation. Use Case: Applying layout algorithms (Force Atlas, Früchterman-Reingold), calculating metrics, and creating publication-ready visualizations of large disease networks. |

| NetworkX [5] | Python Library | Primary Function: A Python package for the creation, manipulation, and study of the structure, dynamics, and functions of complex networks. Use Case: Programmatic construction of disease networks, calculation of topological properties (degree, betweenness), and implementation of network algorithms. |

| powerlaw Library [5] | Python Library | Primary Function: A toolkit for testing if a probability distribution follows a power law. Use Case: Fitting and validating the scale-free properties of a constructed diseasome network. |

The following diagram illustrates a typical workflow integrating these tools for diseasome analysis, from data processing to biological insight.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Diseasome Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Diseasome Research |

|---|---|---|

| Biomedical Ontologies | Gene Ontology (GO), Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO), Cell Ontology (CL), Disease Ontology (DO) [5] [4] | Provide standardized, hierarchical vocabularies for consistent annotation of genes, phenotypes, cells, and diseases, enabling semantic similarity calculations. |

| Bioinformatics Software/Packages | Seurat (for scRNA-seq processing) [5], DCGL (for differential co-expression analysis) [5], RDKit (for drug structural similarity) [5], LDSC (for genetic correlation) [3] | Perform critical data processing and analytical steps on raw molecular and clinical data to generate inputs for network construction. |

| Molecular Interaction Databases | Protein-protein interaction databases, PhosphoSite (post-translational modifications), JASPAR (transcription factor binding) [2] | Provide curated knowledge on molecular interactions (edges) to build the foundational human interactome. |

| Biobanks & Cohort Data | UK Biobank [3] [6], Human Phenotype Project (HPP) [6], All of Us [6] | Supply large-scale, deep-phenotyped data linking genetic, molecular, clinical, and lifestyle data from hundreds of thousands of participants, serving as a primary data source. |

The diseasome paradigm, powered by network medicine principles and multi-modal data integration, provides a transformative framework for understanding human disease. By systematically mapping the intricate web of relationships between diseases across genetic, transcriptomic, cellular, and phenotypic scales, it moves beyond organ-centric or symptom-based classifications to a etiology-driven disease taxonomy. The methodologies outlined—from ontology-aware similarity scoring to the construction of genetically-augmented and phenotypically-derived networks—provide researchers with a robust toolkit for uncovering the shared pathobiological pathways that underlie disease comorbidities. As large-scale biobanks and deep phenotyping initiatives continue to grow, the refinement and application of the diseasome will be instrumental in advancing biomarker discovery, identifying novel drug repurposing opportunities, and ultimately paving the way for more personalized and effective therapeutic strategies.

Historical Evolution of Disease Network Concepts and Key Milestones

The concept of the diseasome represents a paradigm shift in how we understand human pathology, moving from a siloed view of diseases to a comprehensive network-based model. In this framework, diseases are not independent entities but interconnected nodes in a vast biological network, where connections represent shared molecular foundations, including common genetic origins, overlapping metabolic pathways, and related environmental influences [9]. This approach is particularly valuable for understanding complex multimorbidities—the co-occurrence of multiple diseases in individuals—which exhibit patterned relationships rather than random associations [3]. The field of network medicine has emerged as the discipline dedicated to studying these disease relationships through network science principles, with the goal of uncovering the fundamental organizational structure of human disease [9].

The theoretical foundation of disease networks rests on several key principles. First, disease-associated proteins have been shown to physically interact more frequently than would be expected by chance, suggesting that diseases manifest from the perturbation of functionally related modules within complex cellular networks [9]. Second, the "disease module" hypothesis proposes that the cellular components associated with a specific disease are localized in specific neighborhoods of molecular networks [9]. Third, pleiotropy (where one genetic variant influences multiple phenotypes) and genetic heterogeneity (where multiple variants lead to the same disease) are not exceptions but fundamental features of the genetic architecture of complex diseases, creating intricate cross-phenotype associations [3].

Historical Evolution and Key Theoretical Milestones

The historical development of disease network concepts can be traced through several pivotal milestones that have progressively shaped our understanding of disease relationships. These developments have transitioned from early database-driven approaches to contemporary data-intensive methodologies that leverage large-scale biomedical data.

Table 1: Key Milestones in Disease Network Research

| Time Period | Key Development | Significance | Primary Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-2000 | Early Disease Nosology | Categorical classification of diseases based on symptoms and affected organs | Clinical observation |

| 2007 | First Diseasome Map | Demonstrated that disease genes form a highly interconnected network | Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) |

| 2010-Present | PheWAS-enabled Networks | Unbiased discovery of disease connections using EHR-linked biobanks | Electronic Health Records, Biobanks |

| 2015-Present | Integration of Endophenotypes | Added quantitative traits as intermediaries in disease networks | Laboratory measurements, Biomarkers |

| 2020-Present | AI and Transformer Models | Generative prediction of disease trajectories across lifespan | Population-scale health registries |

The earliest network approaches relied on manually curated databases to construct networks based on shared disease-associated genes or common symptoms [3] [9]. A seminal 2007 study by Goh et al. introduced the first human "diseasome" map by linking diseases based on shared genes, providing visual proof of the interconnected nature of human diseases [3]. This established the foundation for disease-disease networks (DDNs), where nodes represent diseases and edges represent shared biological factors [3].

The rise of electronic health record (EHR)-linked biobanks in the 2010s enabled a less biased approach to modeling multimorbidity relationships through phenome-wide association studies (PheWAS) [3]. This methodology identified thousands of associations between genetic variants and phenotypes, allowing for the construction of shared-single nucleotide polymorphism DDNs (ssDDNs) where edges represent sets of significant SNPs shared between diseases [3]. More recently, the integration of quantitative endophenotypes (intermediate phenotypes like laboratory measurements) has created augmented networks (ssDDN+) that better explain the genetic architecture connecting diseases, particularly for cardiometabolic disorders [3].

The most recent evolution involves artificial intelligence approaches, particularly transformer models adapted from natural language processing. These models, such as Delphi-2M, treat disease histories as sequences and can predict future disease trajectories by learning patterns from population-scale data [10]. This represents a shift from static network representations to dynamic, predictive models of disease progression.

Fundamental Methodologies in Disease Network Research

Constructing disease networks requires integrating diverse data types through standardized methodologies. The primary data sources include genetic association data from PheWAS, which identifies connections between genetic variants and diseases; clinical laboratory measurements that serve as quantitative endophenotypes; protein-protein interaction networks that provide the physical infrastructure for disease module identification; and structured disease ontologies like the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) that enable computational representation of phenotypic relationships [3] [9].

The shared-SNP DDN (ssDDN) construction methodology involves several key steps. First, researchers obtain PheWAS summary statistics from large biobanks (e.g., UK Biobank), typically restricting to HapMap3 SNPs while excluding the major histocompatibility complex region due to its complex linkage disequilibrium structure [3]. For each disease, SNPs surpassing genome-wide significance thresholds (typically p < 5×10^(-8)) are identified. An edge is created between two diseases if they share a predetermined number of significant SNPs (often ≥1), with edge weights potentially reflecting the number of shared SNPs or the strength of genetic correlations [3].

The augmented ssDDN+ methodology extends this approach by incorporating quantitative traits as intermediate nodes. Researchers calculate genetic correlations between diseases and laboratory measurements using methods like linkage disequilibrium score regression (LDSC), which analyzes PheWAS summary-level data while accounting for linkage disequilibrium patterns across the genome [3]. In this enhanced network, connections are established not only through direct SNP sharing but also through shared genetic correlations with biomarkers such as HDL cholesterol and triglycerides, which have been shown to connect multiple cardiometabolic diseases [3].

Key Analytical Techniques

Several network analysis techniques have been specifically adapted for disease network research. Network propagation (also called network diffusion) approaches identify disease-related modules from initial sets of "seed" genes associated with a disease [9]. These methods detect topological modules enriched in seed genes, allowing researchers to filter false positives, predict new disease-associated genes, and relate diseases to specific biological functions [9].

The disease module identification process follows a standardized workflow. Researchers begin with seed genes known to be associated with a disease through genotypic or phenotypic evidence. These seeds are mapped onto molecular networks, and algorithms identify network neighborhoods enriched in these seeds. The resulting modules are then validated for functional coherence and tested for association with relevant biological pathways and processes [9].

Multi-layer network integration has emerged as a powerful approach for combining different data types. Researchers construct networks with different node and edge types (e.g., genes, diseases, phenotypes) and develop integration frameworks to identify conserved patterns across network layers. These integrated networks have proven particularly valuable for identifying robust disease modules and understanding the multidimensional nature of complex diseases [9].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Standards

Protocol 1: Construction of a Shared-SNP Disease-Disease Network

This protocol details the methodology for constructing a shared-SNP disease-disease network (ssDDN) from biobank-scale data, adapted from studies using UK Biobank data [3].

Sample Processing and Quality Control: Begin with genetic and phenotypic data from a large, EHR-linked biobank. For the UK Biobank, this involves approximately 400,000 British individuals of European ancestry. Perform quality control on genetic data, excluding SNPs with high missingness rates, deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, or low minor allele frequency. For phenotypes, map EHR diagnoses to a standardized vocabulary like phecodes, excluding phenotypes with fewer than 1000 cases to ensure sufficient statistical power [3].

Genetic Association Testing: Conduct a PheWAS using appropriate software (e.g., SAIGE for binary traits) that accounts for population stratification, relatedness, and covariates including sex, age, and genetic principal components. For each phecode-labeled phenotype, test associations with millions of imputed SNPs, applying standard genome-wide significance thresholds (p < 5×10^(-8)) [3].

Network Construction and Validation: Create the ssDDN by connecting diseases that share significant SNPs, applying filters to remove spurious connections. Validate the network by checking if known multimorbidities are recovered and through enrichment analysis of shared biological pathways between connected diseases. Perform robustness testing through bootstrap resampling or edge permutation [3].

Protocol 2: Disease Trajectory Prediction with Transformer Models

This protocol outlines the methodology for training transformer models to predict disease progression, based on the Delphi model architecture [10].

Data Preprocessing and Tokenization: Extract longitudinal health records including disease diagnoses (coded as ICD-10 codes), demographic information (sex, age), lifestyle factors (BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption), and mortality data. Represent each individual's health trajectory as a sequence of tokens, where each token represents a diagnosis at a specific age, plus special tokens for "no event" periods, lifestyle factors, and death. For time representation, replace standard positional encoding with continuous age encoding using sine and cosine basis functions [10].

Model Architecture and Training: Implement a modified GPT-2 architecture with three key extensions: (1) continuous age encoding instead of discrete positional encoding, (2) an additional output head to predict time-to-next token using an exponential waiting time model, and (3) amended causal attention masks that also mask tokens recorded at the same time. Partition data into training (80%), validation (10%), and test (10%) sets. Train the model using standard language modeling objectives but adapted for disease prediction [10].

Model Validation and Interpretation: Validate the model by assessing its calibration and discrimination for predicting diverse disease outcomes across different age groups and demographic subgroups. Use external validation datasets when possible (e.g., Danish registries for the Delphi model). Apply explainable AI methods to interpret predictions and identify clusters of co-morbidities and their time-dependent consequences on future health [10].

Visualization of Disease Network Concepts

Diseasome Network Architecture

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental architecture of disease networks, showing the relationships between different biological scales and disease associations.

Diseasome Network Architecture

ssDDN+ Construction Workflow

This diagram outlines the comprehensive workflow for constructing an augmented shared-SNP disease-disease network with endophenotypes (ssDDN+).

ssDDN+ Construction Workflow

Quantitative Findings and Research Applications

Key Genetic Correlations in Disease Networks

Research using ssDDN+ methodology has revealed specific quantitative relationships between endophenotypes and disease connections. These findings highlight the importance of quantitative biomarkers in explaining shared genetic architecture between complex diseases.

Table 2: Key Endophenotype-Disease Connections in ssDDN+ Networks

| Endophenotype | Most Strongly Connected Diseases | Number of Diseases Connected | Key Genetic Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| HDL Cholesterol | Type 2 Diabetes, Heart Failure | Greatest number of diseases | Strongest genetic correlation with cardiometabolic diseases |

| Triglycerides | Cardiovascular Disease, Metabolic Syndrome | Substantial number | Adds significant edges to ssDDN+ |

| LDL Cholesterol | Coronary Artery Disease, Atherosclerosis | Multiple connections | Shared loci with vascular diseases |

| Fasting Glucose | Type 2 Diabetes, Metabolic Disorders | Significant connections | Reveals shared metabolic pathways |

Studies have demonstrated that HDL cholesterol connects the greatest number of diseases in augmented networks and shows particularly strong genetic correlations with both type 2 diabetes and heart failure [3]. Triglycerides, another blood lipid with known genetic causes in non-mendelian diseases, also adds a substantial number of edges to the ssDDN+, revealing previously unrecognized connections between metabolic and inflammatory disorders [3].

Performance Metrics for Disease Prediction Models

The evolution of disease network concepts has enabled increasingly sophisticated prediction models. Recent transformer-based approaches like Delphi-2M have demonstrated significant improvements in predicting disease trajectories across diverse conditions.

Table 3: Performance Metrics for Disease Prediction Models

| Model Type | Average AUC | Diseases Covered | Time Horizon | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Disease Models | Variable by disease | 1 disease | Short-term | Disease-specific optimization |

| Traditional Multimorbidity Models | 0.65-0.75 | Dozens of diseases | Medium-term | Captures basic comorbidities |

| Delphi-2M Transformer | ~0.76 | >1,000 diseases | Up to 20 years | Comprehensive disease spectrum, generative capabilities |

The Delphi-2M model achieves an average age-stratified area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of approximately 0.76 across the spectrum of human disease in internal validation data [10]. This performance is comparable to existing single-disease models but with the advantage of predicting over 1,000 diseases simultaneously based on previous health diagnoses, lifestyle factors, and other relevant data [10].

Successful disease network research requires specific computational resources, data tools, and analytical frameworks. The following table summarizes key resources mentioned in the literature.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Disease Network Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biobank Data | UK Biobank, Danish Disease Registry | Large-scale genetic and phenotypic data | Network construction, model training, validation |

| Phenotype Ontologies | Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO), ICD-10 | Standardized disease and phenotype coding | Data harmonization, cross-study comparisons |

| Genetic Analysis Tools | SAIGE, Hail, LDSC | Genetic association testing, correlation analysis | PheWAS, genetic correlation estimation |

| Network Analysis Platforms | Cytoscape, NetworkX, igraph | Network construction, visualization, analysis | Module identification, topology analysis |

| AI/ML Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow | Deep learning model implementation | Transformer models, predictive analytics |

The UK Biobank has been particularly instrumental in disease network research, providing PheWAS summary statistics for 400,000 British individuals with 1,403 phecode-labeled phenotypes and 31 quantitative biomarker measurements [3]. The Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) offers a standardized vocabulary for phenotypic abnormalities with hierarchical relationships, enabling computational analysis of disease phenotypes and their similarities [9].

Specialized computational tools include SAIGE for genetic association testing of binary traits, LDSC for estimating genetic correlations, and network propagation algorithms for identifying disease modules in molecular networks [3] [9]. Recent transformer-based approaches like Delphi-2M require modified GPT architectures with continuous age encoding and additional output heads for time-to-event prediction [10].

Future Directions and Research Challenges

The field of disease network research continues to evolve with several emerging trends and persistent challenges. Multi-omics integration represents a frontier where genetic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data are combined into unified network models to capture the full complexity of disease mechanisms [9]. Temporal network modeling is advancing beyond static representations to dynamic networks that capture how disease relationships evolve over time and across the lifespan [10]. The integration of artificial intelligence with network medicine is producing powerful hybrid approaches that combine the pattern recognition capabilities of deep learning with the biological interpretability of network models [11] [10].

Significant challenges remain in data harmonization across heterogeneous sources, requiring improved ontological frameworks and data standards [9]. Computational scalability continues to be tested as networks grow to incorporate millions of nodes and edges, necessitating more efficient algorithms and computing infrastructure [12]. The field also grapples with translational gaps between network discoveries and clinical applications, particularly in drug development and personalized medicine interventions [3] [9].

Future research directions highlighted in recent literature include developing more sophisticated visualization tools for biological networks that move beyond schematic node-link diagrams to incorporate advanced network analysis techniques [12]. There is also growing interest in fairness and bias mitigation in disease network models, particularly as they increasingly inform clinical decision-making [10]. Finally, researchers are working toward clinical implementation frameworks that can translate network-based risk predictions into actionable interventions for personalized healthcare [11] [10].

The application of graph theory has fundamentally transformed the study of complex biological systems, providing a powerful framework for modeling and analyzing intricate relationships. In biomedical contexts, network medicine has emerged as a distinct discipline that understands human diseases from a network theory perspective [1]. This approach has proven particularly intuitive and powerful for revealing hidden connections among seemingly unrelated biomedical entities, including diseases, physiological processes, signaling pathways, and genes [1]. The structural analysis of disease networks has created significant opportunities in drug repurposing, addressing the high costs and prolonged timelines of traditional drug development by identifying new therapeutic applications for existing compounds [1]. Within this paradigm, network topology—the arrangement of nodes and edges within a network—provides essential insights into the organizational principles of biomedical systems that would remain obscured through reductionist approaches alone.

Core Topological Properties

Network topology describes the arrangement of nodes and edges within a network, with specific properties applying to the network as a whole or to individual components [13]. Understanding these properties is essential for unraveling the complex information contained within biomedical networks.

Fundamental Properties and Definitions

Nodes and Edges: In graph-theoretic modeling, a graph comprises a set of nodes (vertices) representing entities, and links (edges) connecting pairs of nodes [14]. In biomedical contexts, nodes typically represent biological concepts such as genes, proteins, or diseases, while edges represent relationships or interactions between them.

Node Degree: The degree of a node is the number of edges that connect to it, serving as a fundamental parameter that influences other characteristics such as node centrality [13]. The degree distribution of all nodes in a network helps determine whether a network is scale-free [13]. In directed networks, nodes have two degree values: in-degree for edges entering the node and out-degree for edges exiting the node [13].

Shortest Paths: The shortest path represents the minimal distance between any two nodes and models how information flows through networks [13]. This property is particularly relevant in biological networks where signaling pathways and disease propagation follow path-dependent routes.

Clustering Coefficient: This measure quantifies the level of clustering in a graph at the local level, calculated for a given node by counting the number of links between the node's neighbors divided by all their possible links [14]. This results in a value between 0 and 1, which is then averaged across all nodes in a network.

Average Path Length: Also called the "average shortest path," this metric refers to the average distance between any two nodes in the network [14]. The diameter represents the longest distance between any two nodes in the network [14].

Key Network Topologies in Biomedical Contexts

Scale-Free Networks: In scale-free networks, most nodes connect to a low number of neighbors, while a small number of high-degree nodes (hubs) provide high connectivity to the entire network [13]. These networks exhibit a power law distribution in node degrees, where a few nodes have many neighbors while most nodes have only a few [14]. This architecture promotes flexible navigation and less restrictive organic-like growth in comprehensive medical terminologies [14].

Small-World Networks: Networks with small-world properties feature highly clustered neighborhoods while maintaining the ability to move from one node to another in a relatively small number of steps [14]. This combination of strong local clustering and short global separation characterizes many biological systems where functional modules operate efficiently within larger networks.

Transitivity and Clusters: Transitivity relates to the presence of tightly interconnected nodes called clusters or communities—groups of nodes that are more internally connected than they are with the rest of the network [13]. These topological clusters often represent functional modules in biological systems, such as protein complexes or coordinated metabolic pathways.

Experimental Framework for Topological Analysis

The methodology for conducting topological analysis of biomedical terminologies involves specific protocols for data extraction, network modeling, and statistical comparison.

Terminology Selection and Data Extraction

In a landmark study analyzing 16 biomedical terminologies from the UMLS Metathesaurus, researchers selected source vocaburies covering varied domains to form a balanced selection of larger terminologies [14]. To enhance interpretability, they chose source vocabularies familiar to the terminological research community and included related terminology sets for contrastive purposes (ICD9CM and ICD10; SNOMEDCT, SNMI, and RCD) [14]. The extraction process utilized the MetamorphoSys program with the RRF (Rich Release Format) to ensure source transparency—the ability to see terminologies in a format consistent with that obtainable from the terminology's authority [14]. After importing selected tables into a relational database, researchers queried the MRREL table to select links assigned by each terminology, excluding concepts with no associated relationships (isolates) as they don't contribute meaningful information to statistical measures [14].

Network Modeling and Measurements

Each terminology was modeled as a graph where concepts represented nodes and links were assigned between concept pairs appearing in MRREL [14]. To facilitate comparison of large-scale structure, researchers simplified networks by treating all link types equally and disregarding directionality [14]. For each terminology network, the study calculated specific measurements shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Topological Measurements in Network Analysis

| Measurement | Description | Calculation Method | Interpretation in Biomedical Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Node Degree | Average number of links per node | (Number of links × 2) / Number of nodes | Measure of graph density; indicates relationship richness in terminologies |

| Node Degree Distribution | Distribution of connectivity across nodes | Scatterplot with node degree (log) vs. frequency (log) | Identifies scale-free properties through power law distribution |

| Average Path Length | Average shortest distance between node pairs | Average of minimum distances between all node pairs | Indicates efficiency of information flow; shorter paths suggest small-world properties |

| Diameter | Longest distance between any two nodes | Maximum of all shortest paths | Reveals maximal conceptual separation in terminology |

| Clustering Coefficient | Level of local clustering | Average of node-level clustering coefficients (0-1) | Quantifies modular organization; higher values indicate strong local connectivity |

Statistical Comparison with Random Controls

To confirm statistically significant differences in topological parameters, the methodology created three random networks per terminology network of equivalent size and density [14]. This controlled comparison allowed researchers to distinguish meaningful topological features from random arrangements, with average path length and diameter measures being particularly stable across randomizations [14].

Quantitative Analysis of Biomedical Terminology Networks

Comprehensive topological analysis of large-scale biomedical terminologies has revealed distinct structural patterns with significant implications for terminology design and maintenance.

Topological Findings from Terminology Analysis

In the study of 16 UMLS terminologies, eight exhibited small-world characteristics of short average path length and strong local clustering, while an overlapping subset of nine displayed power law distribution in node degrees indicative of scale-free architecture [14]. These divergent topologies reflect different design constraints: constraints on node connectivity, common in more synthetic classification systems, help localize the effects of changes and deletions, while small-world and scale-free features, common in comprehensive medical terminologies, promote flexible navigation and organic growth [14].

Table 2: Topological Properties of Selected Biomedical Terminologies

| Terminology | Nodes | Links | Average Node Degree | Average Path Length | Clustering Coefficient | Topological Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPT | 18,622 | 18,621 | 2.00 | 8.88 | 0 | Grid-like |

| NCBI Taxonomy | 247,151 | 246,854 | 2.00 | 26.49 | 0 | Hierarchical |

| Gene Ontology (GO) | 21,234 | 30,105 | 2.84 | 10.51 | 0.001462 | Scale-free |

| Clinical Terms (RCD) | 320,354 | 319,620 | 2.00 | 14.02 | 0.000278 | Small-world |

Implications for Terminology Science

The paradoxical finding that some controlled terminologies are structurally indistinguishable from natural language networks suggests that terminology structure is shaped not only by formal logic-based semantics but by rules analogous to those governing social networks and biological systems [14]. Graph theoretic modeling shows early promise as a framework for describing terminology structure, with deeper understanding of these techniques potentially informing the development of more scalable terminologies and ontologies [14].

Visualization of Network Topologies

Effective visualization of network topologies requires both appropriate graphical representation and adherence to accessibility standards for color contrast.

Basic Network Topology Diagram

Basic Network Concepts: This diagram illustrates the hierarchical relationship between fundamental network topology concepts, showing how local and global properties define network behavior in biomedical contexts.

Disease Network Analysis Workflow

Disease Network Pipeline: This workflow diagram outlines the data science pipeline for disease network construction and analysis, from initial data collection to drug repurposing applications.

Research Reagent Solutions for Network Analysis

Conducting topological analysis of biomedical networks requires specific computational tools and resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Network Analysis

| Research Reagent | Function | Application in Network Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| UMLS Metathesaurus | Comprehensive database of biomedical terminologies | Provides standardized source vocabularies for network construction and comparison |

| MetamorphoSys | Customization tool for UMLS subsets | Enables extraction of selected terminologies in RRF format for source-transparent analysis |

| Graph Theory Libraries | Software libraries for network analysis | Calculate key metrics including node degree, path length, and clustering coefficients |

| Random Network Generators | Algorithms for generating control networks | Create equivalent random networks for statistical comparison and validation of topological features |

| Relational Database Systems | Data management and query platforms | Store and process large-scale terminology data for network modeling |

Network topology provides fundamental insights into the structural organization of biomedical knowledge systems, with distinct topological features emerging from different terminology design principles. The identification of scale-free and small-world architectures in comprehensive medical terminologies reveals organizational principles that promote navigability and sustainable growth. As network medicine continues to evolve, topological analysis will play an increasingly critical role in understanding disease relationships, identifying functional modules, and discovering new therapeutic opportunities through drug repurposing. The integration of graph theoretic approaches with traditional terminology science offers promising avenues for developing more scalable and computationally tractable biomedical knowledge resources.

The Spectrum of Autoimmune and Autoinflammatory Diseases as a Model System

The study of autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases has undergone a paradigm shift with the adoption of the diseasome and disease network concepts. This framework moves beyond examining individual diseases in isolation to instead map the complex web of relationships between clinically distinct disorders. Autoimmune diseases, characterized by aberrant immune responses against self-antigens, provide an ideal model system for exploring this network medicine approach. Contemporary research reveals that these conditions, which affect approximately 3-5% of the global population and display a marked female predominance (approximately 80% of cases), are interconnected through shared genetic susceptibility loci, common environmental triggers, and overlapping immune dysregulation pathways [15] [16]. A 2025 network analysis of 30,334 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients demonstrated that over half (57%) experienced at least one extraintestinal manifestation or associated immune disorder, with mental, musculoskeletal, and genitourinary conditions forming the most frequent disease communities [17]. This interconnectedness provides a powerful foundation for investigating the autoimmune diseasome.

The conceptual advancement of network medicine in autoimmunity represents more than a academic exercise—it offers tangible clinical benefits. By identifying central nodes and connections within the autoimmune network, researchers can pinpoint critical pathogenic hubs that may be amenable to therapeutic intervention. Furthermore, this approach accelerates the identification of novel biomarkers and reveals drug repurposing opportunities based on shared pathways across disease boundaries. The following sections explore the quantitative epidemiology, mechanistic underpinnings, experimental methodologies, and therapeutic innovations that establish the autoimmune spectrum as a premier model for diseasome research.

Quantitative Epidemiology and Disease Associations

The systematic mapping of autoimmune disease relationships requires robust population-level data. Recent studies provide compelling quantitative evidence for the interconnected nature of these conditions, with implications for both clinical management and research prioritization.

Table 1: Epidemiological Burden of Autoimmune Diseases

| Metric | Value | References |

|---|---|---|

| Global population prevalence | 3-5% | [15] |

| U.S. population affected | >50 million (8% of population) | [16] |

| Female predominance | Approximately 80% of cases | [16] [15] |

| Annual increase in global incidence | 19.1% | [16] |

| Patients with one autoimmune disease developing another | ~25% | [16] |

| UK population with autoimmune diseases (2000-2019) | 978,872 of 22 million (∼10% of study population) | [15] |

Network analysis of large patient cohorts reveals distinct clustering patterns within the autoimmune diseasome. A groundbreaking 2025 study applied artificial intelligence to analyze extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) and associated autoimmune disorders (AIDs) in 30,334 IBD patients, providing unprecedented resolution of disease relationships [17]. The analysis identified distinct disease communities with varying connection densities:

Table 2: Disease Communities in IBD Patients (n=30,334)

| Disease Category | Prevalence in IBD | Preference | Dominant Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental/behavioral disorders | 18% | CD > UC | Depression, anxiety |

| Musculoskeletal system disorders | 17% | CD > UC | Arthropathies, ankylosing spondylitis, myalgia |

| Genitourinary conditions | 11% | CD > UC | Calculus of kidney/ureter/bladder, tubulo-interstitial nephritis |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 10% | No preference | Phlebitis, thrombosis, stroke |

| Circulatory system diseases | 10% | No preference | Cardiac ischemia, pulmonary embolism |

| Respiratory system diseases | 10% | CD > UC | Asthma |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue diseases | 5% | CD > UC | Psoriasis, pyoderma, erythema nodosum |

| Nervous system diseases | 3% | No preference | Transient cerebral ischemia, multiple sclerosis |

This network-based approach demonstrates that diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue form particularly robust clusters, with rheumatoid arthritis serving as a central node connected to various IBD subtypes [17]. The identification of these communities enables researchers to hypothesize about shared pathogenic mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets that might transcend traditional diagnostic boundaries.

Shared Mechanisms and Pathways

The clinical interrelatedness observed in autoimmune diseases stems from common biological pathways that drive loss of self-tolerance and sustained inflammation. Understanding these shared mechanisms is fundamental to exploiting the autoimmune diseasome for therapeutic discovery.

Genetic Susceptibility Networks

Genetic studies have identified numerous susceptibility loci that span multiple autoimmune conditions, revealing a shared genetic architecture. The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) region represents the most significant genetic risk factor across numerous autoimmune diseases, with specific alleles conferring susceptibility to conditions including rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, and multiple sclerosis [15]. Beyond HLA, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified non-HLA risk loci that demonstrate pleiotropic effects. Notably, polymorphisms in genes such as PTPN22, STAT4, TNFAIP3, and IRF5 have been associated with multiple autoimmune diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis, and type 1 diabetes [18] [15]. These genetic networks form the foundational layer of the autoimmune diseasome, establishing a permissive background upon which environmental triggers act.

Common Environmental Triggers

Environmental factors provide the second hit in autoimmune pathogenesis, often through mechanisms that mirror genetic susceptibility in their pleiotropic effects. The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) represents a particularly compelling example of a shared environmental trigger. Recent research has demonstrated that EBV can directly commandeer host B cells, reprogramming them to instigate widespread autoimmunity [19]. In SLE, the EBV protein EBNA2 acts as a transcription factor that activates a battery of pro-inflammatory human genes, ultimately resulting in the generation of autoreactive B cells that target nuclear antigens [19]. This mechanism may extend to other autoimmune conditions such as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and Sjögren's syndrome, where EBV seroprevalence and viral load are frequently elevated [16] [15].

Additional environmental factors including dysbiosis of the gut microbiome, vitamin D deficiency, and smoking have been implicated across the autoimmune spectrum [15]. These triggers appear to converge on common inflammatory pathways, particularly through the activation of innate immune sensors and the disruption of regulatory T cell function. The concept of molecular mimicry, wherein foreign antigens share structural similarities with self-antigens, provides a mechanistic link between infectious triggers and the breakdown of self-tolerance [15].

Convergent Signaling Pathways

At the molecular level, autoimmune diseases share dysregulation in key signaling pathways that control immune cell activation and effector function. The CD28/CTLA-4 pathway, which provides critical costimulatory signals for T cell activation, represents a central node in the autoimmune diseasome [15]. Genetic variations in this pathway influence multiple autoimmune conditions, and therapeutic manipulation of CTLA-4 has demonstrated efficacy in autoimmune models [15]. Similarly, the CD40-CD40L pathway serves as a universal signal for B cell activation, germinal center formation, and autoantibody production across diseases including rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren's syndrome [15].

The type I interferon (IFN) signature represents another convergent pathway, particularly prominent in SLE and Sjögren's syndrome [16] [20]. In these conditions, sustained IFN production creates a feed-forward loop of immune activation and tissue damage. The JAK-STAT pathway, which transduces signals from multiple cytokine receptors, has emerged as a therapeutic target across autoimmune conditions, with inhibitors showing efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and other immune-mediated diseases [21].

Figure 1: Core Pathways in Autoimmune Diseasome. This diagram illustrates the convergent mechanisms driving autoimmunity, with genetic susceptibility and environmental triggers activating shared inflammatory pathways.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

The dissection of the autoimmune diseasome requires sophisticated experimental approaches that can capture the complexity of immune dysregulation across multiple diseases. The integration of high-throughput technologies with bioinformatic analysis has generated powerful methodologies for mapping disease networks.

Network Analysis and Artificial Intelligence

The application of AI-driven network analysis to large patient datasets has emerged as a cornerstone of diseasome research. The 2025 IBD study exemplifies this approach, employing the Louvain algorithm for community detection to identify distinct EIM/AID clusters within a network of 420-467 nodes and 9,116-16,807 edges, depending on the IBD subtype [17]. This method enabled the identification of previously unrecognized disease relationships and temporal patterns. Researchers can access this methodology through an interactive web application that allows for real-time exploration of disease connections, demonstrating how computational tools can transform large-scale clinical data into actionable biological insights.

Advanced Transcriptomic Profiling

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized the resolution at which immune dysregulation can be characterized in autoimmune diseases. This technology enables the identification of novel cell states and inflammatory trajectories by profiling gene expression at the individual cell level [20]. The experimental workflow typically involves:

- Single-cell suspension preparation from patient tissues (blood, synovial fluid, biopsy specimens)

- Cell encapsulation and barcoding using microfluidic platforms

- Reverse transcription and library preparation with unique molecular identifiers

- High-throughput sequencing and bioinformatic analysis using clustering algorithms

The application of scRNA-seq to autoimmune diseases has revealed previously unappreciated heterogeneity in immune cell populations and identified rare pathogenic subsets that drive tissue inflammation [20]. When combined with spatial transcriptomics, this approach can map immune cells within tissue architecture, providing critical context for understanding mechanisms of tissue damage.

Molecular Imaging Techniques

Positron emission tomography (PET) combined with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) enables non-invasive visualization of inflammatory processes across multiple organ systems [20]. Recent advances in tracer development have produced compounds that target specific aspects of immune activation:

Table 3: Molecular Imaging Tracers for Autoimmune Research

| Target | Tracer Examples | Application in Autoimmunity |

|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrate metabolism | 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) | Detection of inflammatory lesions in SLE, RA |

| Chemokine receptors | 68Ga-pentixafor (CXCR4) | Tracking immune cell infiltration |

| Fibroblast activation protein | 68Ga-FAPI | Imaging of fibrotic complications |

| Somatostatin receptors | 68Ga-DOTATATE | Detection of granulomatous inflammation |

| Mitochondrial TSPO | 11C-PK11195 | Visualization of microglial activation in neuroinflammation |

These imaging modalities provide a powerful complement to molecular profiling by enabling longitudinal assessment of disease activity and therapeutic response in live organisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Research into the autoimmune diseasome requires a carefully selected set of reagents and tools that enable the dissection of complex immune interactions. The following table summarizes critical reagents and their applications in autoimmune disease research.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Autoimmune Diseasome Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Flow cytometry antibodies | Anti-CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, CD20, CD38, CD27 | Immune cell phenotyping and subset identification |

| Cytokine detection | IFN-α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-17, TNF-α ELISA/MSD | Measurement of inflammatory mediators |

| Autoantibody assays | ANA, anti-dsDNA, anti-CCP, RF | Diagnostic and prognostic biomarker quantification |

| Cell isolation kits | PBMC isolation, CD4+ T cell selection, B cell purification | Sample preparation for functional studies |

| scRNA-seq platforms | 10X Genomics, BD Rhapsody | Single-cell transcriptomic profiling |

| Multiplex imaging reagents | CODEX, GeoMx Digital Spatial Profiler | Spatial analysis of immune cell distribution |

| Animal models | MRL/lpr mice, collagen-induced arthritis, EAE | Preclinical therapeutic testing |

These reagents form the foundation for experimental investigations into autoimmune disease mechanisms. Their selection must be guided by the specific research question and the need for cross-disease comparisons that can reveal shared pathogenic networks.

Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

The diseasome concept has profound implications for therapeutic development in autoimmune diseases, encouraging strategies that target shared mechanisms across multiple conditions. Recent years have witnessed remarkable advances in immune-targeted therapies that exemplify this approach.

Immune Cell Reprogramming

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, originally developed for oncology, has emerged as a potentially transformative approach for severe, treatment-refractory autoimmune diseases. This strategy involves genetically engineering a patient's own T cells to express synthetic receptors that target specific immune populations. In a groundbreaking application, CD19-directed CAR T-cells induced durable drug-free remission in patients with refractory SLE, achieving rapid elimination of autoantibody-producing B cells and sustained clinical improvement even after B-cell reconstitution [22] [23]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Leukapheresis to collect patient T cells

- T cell activation and genetic modification with viral vectors encoding the CAR construct

- Lymphodepleting chemotherapy to enhance engraftment

- Infusion of CAR T-cells and monitoring for cytokine release syndrome

- Long-term follow-up for efficacy and safety assessment

The success of this approach has sparked an explosion of clinical trials exploring CAR T-cell therapy across a broad spectrum of autoimmune conditions, including multiple sclerosis, myasthenia gravis, and systemic sclerosis [23]. The methodology represents a paradigm shift from continuous immunosuppression toward targeted immune "resetting."

Targeted Biologics and Small Molecules

Beyond cellular therapies, the diseasome concept has informed the development of targeted biologics and small molecules that address shared pathways. The TYK2 pathway, which transduces signals from multiple cytokines including type I IFN, IL-12, and IL-23, has emerged as a compelling target across several autoimmune conditions [21]. Inhibition of TYK2 with agents such as deucravacitinib has demonstrated efficacy in psoriatic arthritis, with emerging evidence supporting potential applications in inflammatory bowel disease and SLE [21].

Similarly, B-cell targeting with agents such as ianalumab has shown significant benefit in Sjögren's disease, reducing disease activity by addressing the underlying autoimmune dysregulation rather than merely alleviating symptoms [21]. These targeted approaches reflect an increasingly precise understanding of the nodes within the autoimmune diseasome that are most amenable to therapeutic intervention.

Figure 2: CAR-T Cell Therapy Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, an emerging approach for severe autoimmune diseases.

The spectrum of autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases provides an exceptionally powerful model system for exploring the diseasome concept and advancing the field of network medicine. The interconnected nature of these conditions, evidenced by shared genetic architecture, common environmental triggers, and convergent inflammatory pathways, offers unprecedented opportunities for mechanistic discovery and therapeutic innovation. The research approaches outlined in this review—from AI-driven network analysis to single-cell transcriptomics and molecular imaging—provide a methodological framework for mapping disease relationships with increasing resolution.

As these technologies continue to evolve, several emerging frontiers promise to further refine our understanding of the autoimmune diseasome. The integration of multi-omic datasets (genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, proteomic) will enable more comprehensive mapping of disease networks. Advances in spatial biology will contextualize immune dysregulation within tissue microenvironments. Furthermore, the application of machine learning to large-scale clinical data will identify novel disease associations and predict therapeutic responses.

The ultimate translation of diseasome research will be the development of precision medicine approaches that target shared mechanisms across autoimmune conditions, potentially benefiting multiple patient populations. As noted by Dr. Maximilian Konig of Johns Hopkins University, "We've never been closer to getting to—and we don't like to say it—a potential cure. I think the next 10 years will dramatically change our field forever" [22]. The autoimmune diseasome model provides the conceptual framework needed to realize this transformative potential.

Biomedical ontologies provide a structured, controlled vocabulary for organizing biological and medical knowledge, enabling computational analysis and data integration. The concept of the diseasome—a network representation of human diseases—relies on these formal frameworks to map the complex relationships between diseases based on shared molecular origins, phenotypic manifestations, and underlying genetic architectures [24] [3]. Disease-disease networks (DDNs) constructed from ontological relationships reveal that disorders with common genetic foundations or phenotypic features often cluster together in the human interactome [24] [3]. This network-based perspective is transforming our understanding of disease etiology, moving beyond traditional anatomical or histological classification systems toward a molecularly-defined nosology that can identify novel disease relationships and therapeutic targets [24]. Ontologies like Mondo, Disease Ontology (DO), Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) provide the essential semantic structure for representing disease concepts and their relationships, forming the computational foundation for diseasome research and network medicine applications in drug discovery and development.

Core Disease Ontology Frameworks

Mondo Disease Ontology

Mondo Disease Ontology (Mondo) is a comprehensive logic-based ontology designed to harmonize disease definitions across multiple biomedical resources [25]. The name "Mondo" originates from the Latin word 'mundus,' meaning 'for the world,' reflecting its global scope and applicability. Mondo addresses the critical challenge of overlapping and sometimes conflicting disease definitions across resources like HPO, OMIM, SNOMED CT, ICD, PhenoDB, MedDRA, MedGen, ORDO, DO, and GARD by providing precise equivalences between disease concepts using semantic web standards [25].

Mondo is constructed semi-automatically by merging multiple disease resources into a coherent ontology. A key innovation is its use of precise 1:1 equivalence axioms connecting to other resources like OMIM, Orphanet, EFO, and DOID, which are validated by OWL reasoning rather than relying on loose cross-references [25]. This ensures safe data propagation across these resources. The ontology is available in three formats: the OWL edition with full equivalence axioms and inter-ontology axiomatization; a simpler .obo version using xrefs; and an equivalent JSON edition [25].

Table: Mondo Disease Ontology Statistical Overview

| Metric | Count |

|---|---|

| Total number of diseases | 25,880 |

| Database cross references | 129,785 |

| Term definitions | 17,946 |

| Exact synonyms | 73,878 |

| Human diseases | 22,919 |

| Cancer (human) | 4,727 |

| Mendelian diseases | 11,601 |

| Rare diseases | 15,857 |

| Non-human diseases | 2,960 |

Table: Mondo Disease Categorization

| Category | Count (classes) |

|---|---|

| Human diseases | 22,919 |

| Cancer | 4,727 |

| Infectious | 1,074 |

| Mendelian | 11,601 |

| Rare | 15,857 |

| Non-human diseases | 2,960 |

| Cancer (non-human) | 215 |

| Infectious (non-human) | 87 |

| Mendelian (non-human) | 1,023 |

Disease Ontology (DO) and DOLite

The Disease Ontology (DO) organizes disease concepts in a directed acyclic graph (DAG), where traversing away from the root moves toward progressively more specific terms [26]. The full DO graph contains substantial complexity—revision 26 included 11,961 terms with up to 16 hierarchical levels—creating challenges for specific applications like gene-disease association studies [26].

To address this, DOLite was developed as a simplified vocabulary derived from DO using statistical methods that group DO terms based on similarity of gene-to-DO mapping profiles [26]. The methodology involves:

- Pre-filtering DO terms: Removing abstract concepts with few gene associations

- Creating a gene-to-DO mapping profile matrix: Documenting evidence of gene-disease relationships

- Calculating distance metrics: Measuring overall similarity (

dist1) and subset similarity (dist2) between DO terms based on their gene associations - Applying compactness-scalable fuzzy clustering: Grouping similar DO terms while constraining results with semantic similarities

This approach significantly reduces redundancy and creates a more tractable ontology for enrichment tests, yielding more interpretable results for gene-disease association analyses [26].

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) is a controlled, hierarchically-organized vocabulary produced by the National Library of Medicine for indexing, cataloging, and searching biomedical information [27]. MeSH serves as the subject heading foundation for MEDLINE/PubMed, the NLM Catalog, and other NLM databases, providing a comprehensive terminology for literature retrieval. The taxonomy is regularly updated, with 2025 MeSH files currently in production and available through multiple formats including RDF and an open API [27]. MeSH is part of a larger ecosystem of medical vocabularies that includes RxNorm for drugs, DailyMed for marketed drug information, and the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) Metathesaurus which integrates over 150 medical vocabulary sources [27].

International Classification of Diseases (ICD)

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) is a global standard for diagnostic classification maintained by the World Health Organization, widely used for billing, epidemiological tracking, and health statistics [28]. ICD coding presents significant challenges for automation due to the complexity of medical narratives and the hierarchical structure of ICD codes. Recent advances in machine learning for automated ICD coding include:

- Hierarchical modeling: Approaches like Tree-of-Sequences LSTM that capture parent-child relationships in the ICD taxonomy [29]

- Graph neural networks (GNNs): Frameworks like LGG-NRGrasp that model ICD coding as a labeled graph generation problem using adversarial reinforcement learning [29]

- Novel evaluation metrics: The introduction of λ-DCG, a metric tailored specifically for ICD coding tasks that provides more interpretable assessment of coding system quality [28]

These computational approaches must address challenges like over-smoothing in deep networks, structural inconsistencies in medical data, and limited labeled datasets [29].

Table: Comparative Analysis of Disease Ontology Frameworks

| Feature | Mondo | Disease Ontology (DO) | MeSH | ICD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Harmonize disease definitions across resources | Gene-disease association studies | Literature indexing & retrieval | Billing & epidemiology |

| Structure | Logic-based ontology with equivalence axioms | Directed acyclic graph (DAG) | Hierarchical vocabulary | Hierarchical classification |

| Coverage | 25,880 diseases | 11,961 terms (revision 26) | Comprehensive biomedical topics | Diseases, symptoms, abnormal findings |

| Key Innovation | Precise 1:1 equivalence mappings between resources | DOLite simplified version for statistical testing | Integration with UMLS Metathesaurus | Global standard for health statistics |

| Molecular Focus | High - integrates genetic & phenotypic data | High - designed for gene-disease relationships | Medium - includes genetic terms | Low - primarily clinical descriptions |

Ontology Applications in Diseasome and Disease Network Research

Constructing Disease-Disease Networks

Biomedical ontologies enable the construction of disease-disease networks (DDNs) that reveal shared genetic architecture and molecular relationships between disorders. The shared-SNP DDN (ssDDN) approach uses PheWAS summary statistics to connect diseases based on shared genetic variants, accurately modeling known multimorbidities [3]. An enhanced version, ssDDN+, incorporates genetic correlations with intermediate endophenotypes like clinical laboratory measurements, providing deeper insight into molecular contributors to disease associations [3].

For example, research using UK Biobank data has demonstrated that HDL-C connects the greatest number of diseases in cardiometabolic networks, showing strong genetic relationships with both type 2 diabetes and heart failure [3]. Triglycerides represent another blood lipid biomarker that adds substantial connections to disease networks, revealing shared genetic architecture across seemingly distinct disorders [3].

Disease Network via Shared Genetics & Biomarkers

Phenotype-Based Disease Similarity

Semantic similarity calculations using ontology-annotated phenotype data enable the identification of disease relationships beyond genetic associations. Text-mining approaches applied to MEDLINE abstracts can extract phenotype-disease associations, generating comprehensive disease signatures that cluster disorders with common pathophysiological underpinnings [4].

The methodology involves:

- Identifying co-occurrences: Mining disease-phenotype term co-occurrences in biomedical literature

- Statistical scoring: Applying normalized pointwise mutual information (NPMI), T-Score, Z-Score, and Lexicographer's mutual information to rank associations

- Optimal phenotype cutoff determination: Establishing the ideal number of phenotype annotations per disease (empirically determined to be 21 phenotypes)

- Similarity computation: Using systems like PhenomeNET to calculate phenotypic similarity between human diseases and model organism phenotypes

This approach has demonstrated high accuracy (ROCAUC 0.972 ± 0.008) in matching text-mined disease definitions to established OMIM disease profiles [4].

Network Medicine and Drug Development

Disease progression modeling (DPM) uses mathematical frameworks to characterize disease trajectories, integrating ontological definitions to inform clinical trial design and therapeutic development [30]. DPM applications identified through scoping review include:

- Informing patient selection (56 studies): Identifying patient subtypes based on predicted disease progression

- Enhancing trial designs (35 studies): Using DPM of longitudinal data to increase power or reduce sample size requirements

- Identifying biomarkers and endpoints (34 studies): Developing prognostic models for predicting disease progression

- Characterizing treatment effects (various studies): Informing dose selection and optimization

These applications demonstrate how ontology-structured disease concepts enable more efficient drug development, particularly for rare diseases where traditional trial design faces significant challenges [30].

Experimental Methodologies and Workflows

Gene-Disease Association Enrichment Analysis

DOLite Construction & Enrichment Analysis Workflow

Automated ICD Coding with Graph Neural Networks

The LGG-NRGrasp framework represents a cutting-edge approach to automated ICD coding using graph neural networks [29]. The methodology involves:

- Labeled Graph Generation: Constructing relational graphs from clinical narratives that capture dependencies among diagnostic codes

- Dynamic Architecture: Employing residual propagation and feature augmentation to prevent over-smoothing

- Adversarial Training: Enhancing robustness through domain adaptation techniques

- Reinforcement Learning Integration: Using a parameterized policy (π_θ) for probabilistic decision-making over graph states

This framework specifically addresses challenges like hierarchical ICD code relationships, sparse clinical data, and the need for model interpretability in healthcare settings [29].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Diseasome Studies

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Diseasome Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mondo Ontology | Computational Resource | Disease concept harmonization | Integrating multiple disease databases with precise mappings |

| MeSH RDF API | Data Retrieval | Programmatic access to MeSH | Semantic querying of disease-literature relationships |

| PheWAS Summary Statistics | Dataset | Genetic association data | Constructing shared-SNP disease networks (ssDDNs) |

| UK Biobank Data | Biomarker & Genetic Data | Population-scale biomedical data | Augmenting DDNs with biomarker correlations (ssDDN+) |

| PhenomeNET System | Computational Tool | Phenotypic similarity calculation | Cross-species disease phenotype comparison |

| HPO/MP Ontologies | Phenotype Vocabularies | Standardized phenotype descriptions | Annotating diseases with computable phenotypic profiles |

Phenotype-Driven Disease Network Construction

The workflow for constructing phenotype-based disease networks involves [4]:

- Data Extraction: Mining 5 million MEDLINE abstracts for disease-phenotype co-occurrences

- Annotation: Associating over 6,000 Disease Ontology classes with 9,646 phenotype classes from HPO and MP

- Statistical Validation: Using known gene-disease associations from OMIM and MGI to optimize phenotype cutoffs

- Similarity Computation: Applying semantic similarity measures to generate human disease networks